Crossref Citations

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref.

McCallum, Jessica

Yip, Ryan

Dhanani, Sonny

and

Stiell, Ian

2020.

Solid organ donation from the emergency department – missed donor opportunities.

CJEM,

Vol. 22,

Issue. 5,

p.

701.

Hickey, Michael

Yadav, Krishan

Abdulaziz, Kasim E.

Taljaard, Monica

Hickey, Carly

Hartwick, Michael

Sarti, Aimee

McIntyre, Lauralyn

and

Perry, Jeffrey J.

2022.

Attitudes and acceptability of organ and tissue donation registration in the emergency department: a national survey of emergency physicians.

Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine,

Vol. 24,

Issue. 3,

p.

293.

Wtorek, Piotr

Weiss, Matthew J.

Singh, Jeffrey M.

Hrymak, Carmen

Chochinov, Alecs

Grunau, Brian

Paunovic, Bojan

Shemie, Sam D.

Lalani, Jehan

Piggott, Bailey

Stempien, James

Archambault, Patrick

Seleseh, Parisa

Fowler, Rob

and

Leeies, Murdoch

2024.

Beliefs of physician directors on the management of devastating brain injuries at the Canadian emergency department and intensive care unit interface: a national site-level survey.

Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d'anesthésie,

Vol. 71,

Issue. 8,

p.

1145.

The task of every emergency physician when faced with a critically ill patient is to save life and relieve suffering. When we cannot save life, despite our best and most aggressive efforts, we must ensure that we honor the wishes of the patients who might die, and this includes any applicable wishes to be an organ or tissue donor. Every family and patient must be offered the opportunity for organ donation at the appropriate time by an appropriate expert. As emergency physicians, we have a duty to support this process.

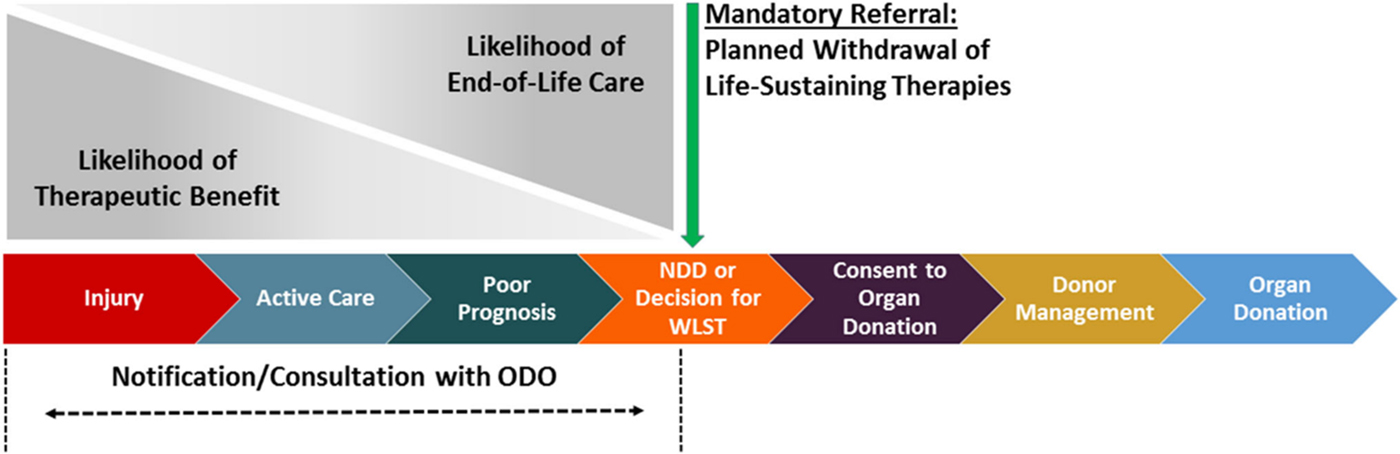

The role of the emergency department (ED) team in organ donation is in the identification, prompt referral, and physiological support of potential organ donors to allow time and opportunity for donation. Organ donation may occur by donation after neurological determination of death (NDD) or by donation after circulatory death (DCD) (Figure 1). Consequently, identification of potential donors includes recognizing potential donors in patients with severe neurological injuries that may progress to death by neurological criteria, patients in whom invasive support may be withdrawn, and in some jurisdictions even after unsuccessful attempts at resuscitation after cardiac arrest. Indeed, this is a challenging undertaking in the ED; potential challenges include the uncertainty of neurological outcomes in the hyperacute phase of care, emotionally charged situations with families, and the lack of information and knowledge of patient wishes. Additionally, low volume of exposure to organ donation means it is essential to have excellent access to critical care and donation professionals, which must be facilitated by hospital and organ donation organization (ODO) processes.

Figure 1. Sequence of care in deceased donation in relation to notification and referral. (Taken from Zavalkoff S, Shemie SD, Grimshaw JM, et al.Reference Zavalkoff, Shemie and Grimshaw1 No changes were made. Under Creative Commons license [http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/]).

In this issue of CJEM, two groups of authors address important questions about organ donation arising from care provided in the ED. McCallum et al. performed a systematic review to describe solid organ donation arising from identification and referral of patients while they were in the ED.Reference McCallum, Ellis, Dhanani and Stiell2 Ellis et al. conducted a survey of waiting ED patients to determine the receptiveness to receive information about organ donation and even to register their consent during the ED visit.Reference Ellis, Hartwick and Perry3 Both studies shed light on the opportunities and challenges of organ donation arising in the ED, as well as provide insights into where professionals can focus efforts on improving performance and honor the wishes of our dying patients.

McCallum et al. add to our knowledge of the organ donation opportunities arising in the ED: both the high number of potential donors, as well as the significant proportion of opportunities lost through failure to refer potential donors to the ODO. Although the authors found that a variable percentage of potential donors are referred while in the ED (between 4%–50% of NDD and 3%–9% of DCD donors), the most striking finding is the number of missed opportunities within the department; some of their studies reported that as many as 84% of potential donors dying in the ED were missed.Reference McCallum, Ellis, Dhanani and Stiell2 This, in our view, is simply unacceptable, and represents a call to action. The authors highlight that nearly all opportunities are missed as a result of failure to refer to the ODO prior to the withdrawal of invasive physiologic support, after which the opportunity to donate is lost. Several barriers to effective referral to the ODO exist, including time of the provider, incorrect assumptions around medical suitability for donation, and age and comorbid conditions were recognized as barriers to effective notification of the ED. The rapid evolution of donation and transplant science means that suitability criteria are frequently changing and are not easily assessed by front-line physicians. Indeed, in our local ODO, a recent quality assurance audit revealed that almost 1 in 5 patients who were not referred had potential donation eligibility (unpublished data provided by Trillium Gift of Life Network). All of these challenges can be overcome by improving the timely referral of all potential donors to the ODO.

Management of end-of-life care in the ED is a hyperacute situation fraught with complexities and an often incomplete data set. These issues impact the ability of physicians to both prognosticate and do comprehensive end-of-life care planning because there is often little information regarding patient preferences or wishes. Premature prognostication based on these incomplete data may lead to premature withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies, and the impact of premature withdrawal practices has been well documented in cardiac arrest and traumatic brain injury.Reference Elmer, Torres and Aufderheide4, Reference Turgeon, Lauzier, Simard, Scales and Burns5 While the prognosis may be thought to be obvious, even with consultant neurosurgical input, time can only increase certainty for both the family and the treating team. Taking our time also provides the opportunity to gather more information regarding patient preferences about survival, minimally acceptable quality of life, and organ donation if the patient or family chooses to withdraw invasive support. This is the best care for our patients and could result in lives saved (both the lives of our patients, as well as the recipients of organ transplants from the deceased donors).Reference Harvey, Butler and Groves6

One challenge with organ donation in the ED is the lack of knowledge of a patient's wishes regarding donation and the limited time available to provide information to the patient and their family. Ellis et al. conducted a simple paper-based survey during peak times in a single ED to understand the receptiveness of those waiting in the ED to receive information about registration for organ donation.Reference Ellis, Hartwick and Perry3 Despite the challenging environment (with patients being ill and burdened with the wait), the authors reported a remarkable response rate (77.8%). Most respondents in this centre agreed or were neutral that they could receive information about organ donation and potentially even register as an organ and tissue donor. This work is important because consent registration by healthy individuals has a powerful impact on the consent discussion and the likelihood of consent being provided by their family if they ever became sick and potential organ donors. The supports and information about donation that would be most helpful to patients and actual registration rates remain unknown, but the finding that this population would be receptive to approach and information should be a powerful motivator for ODOs. It is possible that this would not be borne out in other centres but it deserves exploration.

Organ donation is a rare, life-saving opportunity that respects altruism, patient autonomy, and the best end-of-life care. The work by McCallum et al. highlights the scale of the donation work that we already do in the ED while providing some sobering data on where we could improve performance, prognostication, end-of-life care, and save the lives of those waiting for transplants.Reference McCallum, Ellis, Dhanani and Stiell2 Ellis et al. provide us with some initial interesting insight into how we might provide information to a receptive audience in the ED, potentially increasing vital consent registration rates.Reference Ellis, Hartwick and Perry3 In Canada, because of the mismatch of supply of suitable organs for transplantation, it is estimated that every three days a patient dies while waiting for an organ transplant. If an opportunity to offer donation is missed to a family that would have consented to donation, multiple deaths of potential recipients occur as a direct result of this action. As emergency care providers, we must ensure that we optimize our performance to bridge this gap.

Competing interests

AH reports a salary as Chief Medical Officer – Donation at Trillium Gift of Life Network. JMS reports a salary as Regional Medical Lead – Donation at Trillium Gift of Life Network.