Peru approached the twenty-first century a polarized country. In the year 2000, with increased authoritarian control over the legislative and judicial branches along with constitutional reforms paving the way for his re-reelection, President Alberto Fujimori campaigned for a third term in office. His main electoral opponent, Alejandro Toledo, along with opposition leaders, spearheaded massive demonstrations in Lima accusing the government of repression, corruption, drug trafficking, and electoral fraud. Opposition figures were joined by grassroots social movements, unions, students, and human rights activists who opposed the regime's repressive and corrupt practices, which included by now reports of torture and extrajudicial killings.Footnote 1 When Fujimori first became president a decade earlier he had inherited a country ravaged by widespread poverty, hyperinflation, nearly depleted foreign reserves, a growing narcotics trade, and two armed terrorist groups: the MRTA (Tupac Amarú Revolutionary Movement) and the Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso). Both were on the offensive across the country, the Shining Path most prominently, planting car bombs in the capital, kidnapping and killing civilians, and besieging towns and villages across the country.Footnote 2 Looking for a way out of economic and terrorist violence, Peruvians were faced with two options in 1990: Alberto Fujimori, an ex-university president and agricultural engineer of Japanese descent, and Mario Vargas Llosa, a white, upper-middle-class novelist and liberal intellectual. Though Fujimori was less well-known, many Peruvians saw Vargas Llosa's center-right coalition as a repackaged version of the same traditional political groups that had lead the country into crisis. Fujimori would appear much like Hugo Chávez later in Venezuela, a populist outsider ready to challenge the traditional party system. Many saw Fujimori's succinct rhetoric as refreshing when contrasted with Vargas Llosa's elaborate speeches, especially since the former president, Alan García, who fled the country in 1992 on corruption charges, was also well-known for his loquacious disposition.

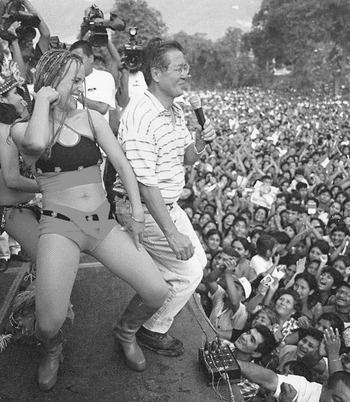

Ethnically, Fujimori presented himself as being outside of the typical white Peruvian criollo elite, framing his Japanese immigrant background as a subaltern position comparable to that of the majority of Peru's indigenous and mestizo population.Footnote 3 This kind of identification was produced through campaign events that repeatedly cast Fujimori within an Andean imaginary even though he had grown up and spent all of his professional life on the coast in Lima. One such moment can be seen in a campaign photograph in which Fujimori addresses supporters wearing a poncho and a colorful chullo, the traditional Andean hat (Figure 1). His Japanese heritage and his professional background as an engineer also mobilized the stereotype of the Asian immigrant as hard working, disciplined, and pragmatic. This generic “Asianness” was exemplified by his moniker, El Chino, literally “the Chinaman.”Footnote 4 The characterization of this subaltern yet aspirational persona would be further developed in various ways over the coming decade, including through the use of popular music with the cumbia hit El ritmo del Chino, to which Fujimori danced repeatedly at campaign rallies (Figure 2).Footnote 5 Opting for what they saw as a more radical change, Peruvians elected Fujimori as president with 62.4 percent of the popular vote in May 1990. In 1995 he was reelected, and in April 2000, after a strategic amendment to Peru's constitution, he won a third term in office.Footnote 6

Figure 1. Alberto Fujimori at a campaign event. Photo: Courtesy El Comercio.

Figure 2. Fujimori dancing El ritmo del Chino at a campaign rally with cumbia singer Ana Kohler. Photo: Courtesy El Comercio.

These first steps in the symbolic construction of El Chino suggest a reliance on techniques of staging, from costume to choreography, to build a character mask able to attract followers through modes of identification and affective attachment in ways that might overcome feelings of skepticism or even concrete policy differences among voters. This array of techniques rises to the level of illusion when it produces a persona whose attributes (honesty, solidarity, goodwill, etc.) are treated as real. In performance, as Meg Mumford writes, illusion is “the aesthetic experience which is generated when a representation has the appearance of being true or real and when recipients respond to it as such. Illusion is thus the product of an interaction influenced by a range of variables, including the artistic media and social context involved.”Footnote 7 This reliance on illusion in politics is of course nothing new. As early as the sixteenth century Machiavelli insisted on the importance to “pretend one thing and cover up another … [so that] a leader does not have to possess all the virtuous qualities I have mentioned, but it's absolutely imperative that he seem to possess them.”Footnote 8 In Fujimori's case pretending and concealing entailed the development of a composite and recognizable set of stereotypes incorporating Andean subalternity, Asian diligence, and Latin festiveness as part of a populist political project that began in the early 1990s with the promising slogan “Honestidad, tecnología y trabajo” (“Honesty, technology, and work”).

Soon after reaching office in April 1992 Fujimori instituted a “self-coup,” known in Peru as the autogolpe, in which he temporarily dissolved the congress and reorganized the judiciary branch. The economic and security challenges at the time were such that Fujimori's autocratic gesture, in the face of what many Peruvians felt were corrupt and inefficient institutions, earned him high approval ratings. The day after the coup independent polls showed that 71–87 percent of Peruvians approved of the temporary dissolution of congress and the call for new legislative elections in 1993, and almost 95 percent approved of the forced reengineering of the judiciary.Footnote 9 Fujimori himself never used the term autogolpe, talking instead of a “regime of necessity.” The underlying logic of actions taken out of necessity would be extended throughout the 1990s as a public justification for antidemocratic measures. As Carlos Pérez Crespo explains:

Fujimori was able to argue, that in the face of an exceptional situation, the essence of democracy consisted in the leader's identification with the people; likewise this was supported by the idea that demands for order, peace, and security could no longer be postponed, justifying for that reason a constitutional break to the detriment of political parties, human rights organizations, and the defenders of constitutional democracy.Footnote 10

Capitalizing on his high approval ratings, Fujimori proceeded to dismiss all congressional and national assembly leaders as part of a political purge that sought to “reset” the country and inaugurate a new era of technocratic efficiency, boldly described as “direct” democracy. The autogolpe would prove to be just the first in a series of overt and covert steps that aimed to shift power away from various government institutions into the hands of the executive.

By 1993 a new constitution opened the path for Fujimori's reelection in 1995, and new congressional elections established Fujimori's party as the majority force within the country's legislative branch. Meanwhile, the economy slowly stabilized itself, drug trafficking seemed to be contained, and both terrorist organizations were weakened considerably, especially with the capture of the Shining Path's supreme commander, Abimael Guzman, in 1992. However, the growing concentration and legitimation of Fujimori's executive power also meant that corruption, extrajudicial killings, torture, and gross human rights violations carried out by the military as part of an aggressive counterterrorist agenda remained sanctioned and unimpeded.Footnote 11 In the years that followed, under the secret direction of Vladimiro Montesinos, Fujimori's chief advisor and head of the National Intelligence Service, the executive was able to purchase the loyalty of key officials across the armed forced, the judicial branch, regional governments, and congress. By the end of the decade, nineteen elected opposition congress members, known as the tránsfugas (“defectors”), had abandoned their parties to join Fujimori's in exchange for money and political favors.Footnote 12

The Illusions of Fujimorismo

To help mitigate these antidemocratic practices and sustain Fujimori's popular appeal among large sectors of the population, the regime magnified the figure of El Chino as a decisive, benevolent, and pragmatic leader. Central to the efficacy of this illusion was Montesinos's ability to control the editorial content of popular newspapers and television stations through payoffs, threats, and political favors. Starting as Fujimori's private lawyer during his first candidacy, Montesinos quickly grew in influence, eventually becoming the architect of a state within the state. Under this arrangement Fujimori embodied the public face of the state while Vladimiro Montesinos functioned as its hidden choreographer. Referred to simply as El Doctor (“The Doctor”), Montesinos shunned the public spotlight, preferring instead to work quietly from his offices at the National Intelligence Service (Servicio de Inteligencia Nacional, or SIN). Armed with the instruments of the state, from aggressive tax inspectors to compliant judges, Montesinos administered surgical pressure on media moguls and journalists to help roll out, sustain, and expand the government's public narrative. Mass media, and television in particular, became the stage upon which the regime sustained a friendly and personable “democratic” facade.Footnote 13 These news platforms began to provide varied degrees of loyal coverage while increasingly attacking dissenting voices.Footnote 14 The administration became intimate with television personalities, including the most popular TV talk-show host at the time, Laura Bozzo, who became famously close with the president and was rewarded with exclusive interviews.Footnote 15 Bozzo was later accused of receiving more than $3 million USD in exchange for her political support.Footnote 16 At the same time the administration silenced popular critical voices such as independent broadcast journalist César Hildebrandt, who quit live on air during a phone confrontation with his channel's owner, Genaro Delgado Parker.Footnote 17 As Alfonso Quiroz explains, “Genaro Delgado Parker, a major shareholder in channel 13, who had chronic legal troubles, promised Montesinos that he would fire independent journalist César Hildebrandt in exchange for a favorable judgment concerning a stock ownership dispute.”Footnote 18

As successive state institutions fell under Montesinos's influence, the administration began to rely even more on media manipulation to prop up an increasingly unsteady clientelist state. As Montesinos explained to a well-known bank executive on November 1999, “if political action does not correlate with the media, it doesn't work.”Footnote 19 This large-scale propaganda campaign was aimed at buttressing a whole series of factors, both endogenous and exogenous, that by early 2000, in spite of its continued appeal, were creating a precarious situation for the Fujimori administration: fears of electoral fraud, a burgeoning economic recession, reports of corruption, social mobilizations, alienation from certain business groups, uncertainty from foreign investors, and growing conflict with the United States and the international community.Footnote 20

As Fujimori prepared for a third reelection campaign in 2000, Montesinos's ability to direct its message and impress it upon the population through television programming and sensationalist tabloid newspapers, known as prensa chicha, became crucial.Footnote 21 Although unbeknownst to people at the time, Montesinos had taken direct editorial control over nine newspapers, including broadsheets and tabloids. As his private secretary would attest, “Mr. Montesinos would sometimes write the next day's headlines himself and would tell the president what would be coming out.”Footnote 22 The planning and timing of particular stories and headlines based on the privileged information Montesinos handled as head of Peru's intelligence agency gave his fabrications particular purchase. “Lies are often much more plausible, more appealing to reason, than reality since,” as Hannah Arendt argues, “the liar has the great advantage of knowing beforehand what the audience wishes or expects to hear. He has prepared his story for public consumption with a careful eye to making it credible.”Footnote 23 The decision to capture and centralize the editorial line of large sectors of Peru's television and newspaper industry in a surreptitious manner also avoided creating the kind of opposition overt dictatorial rule would have invited, something Peru had experienced throughout the 1970s.Footnote 24 And yet the capture of what still appeared to be a diverse media environment gave the regime the kind of legitimacy and space necessary to operate and maintain itself in the face of growing political opposition. As Walter Lippmann observes in relation to public opinion, “a leader or an interest that can make itself master of current symbols is master of the current situation.”Footnote 25

The power that Montesinos wielded was such that Peruvian political analysts now identify the period as fujimontesinismo, identifying it as in effect a diarchy, with one leader operating in public view and the other in the shadows.Footnote 26 Through the National Intelligence Service, Montesinos managed the state within, carefully calibrating threats, bribes, and political favors in order to exert direct control over the military, police, congress, judges, election officials, bankers, and media owners. Funds for these operations would come from the state's coffers as well as government participation in criminal activities such as arms smuggling and drug trafficking.Footnote 27 The growing structural tension between the image of the state as a liberal democracy with Fujimori as its poster boy and its actual mafia structure as managed by Montesinos propelled the state toward a theatrical offensive, with more and more resources directed at image management rather than traditional public services.Footnote 28 Allocated funds from various ministries were redirected to the National Intelligence Service's special Fondo de Acciones Reservadas (“Confidential Actions Fund”) controlled by Fujimori and Montesinos alone for propaganda purposes.Footnote 29

Montesinos would pay tabloids two to three thousand US dollars for each front-page headline, with a total expenditure of $22 million USD between 1998 and 2000 on print alone.Footnote 30 Tabloid headings would fabricate stories to undermine those who opposed the regime, from politicians to independent journalists. Take the headline “Rojo Mohme Dirige El Comercio a Través de Comunista Uceda” (“Red Mohme Directs El Comercio through the Communist Uceda”):Footnote 31 the header contends that Gustavo Mohme Llona, director and founder of the independent center-left newspaper La República, was controlling the liberal center-right newspaper El Comercio, the largest broadsheet in Peru, through Ricardo Uceda, El Comercio’s toughest investigative journalist, who had throughout the late 1990s repeatedly uncovered important cases of corruption involving the Fujimori regime. Symbolically the headline operated at two levels. First it portrayed these persons and publications as vehicles for a radical left agenda when in fact Ricardo Uceda and El Comercio occupy a centrist liberal position, albeit deeply critical of Fujimori, and even Mohme—a moderate social democrat—is described as “rojo,” that is, as a militant communist. The attempt to portray independent journalistic voices as leftist militants is of particular importance in the Peruvian context because the highly stigmatized Shining Path was itself a self-declared Maoist revolutionary movement. To portray Uceda and Mohme as radical leftists meant by implication that they were terrorist sympathizers at best, or at worst enemies of the state. Moreover, with the illusory claim that Uceda had infiltrated El Comercio to manipulate it according to Mohme's instructions, the headline also attempted to homogenize disparate voices portraying them as part of a single coordinated communist network. On the flip side, tabloids rendered Fujimori and his supporters in a positive light with headlines highlighting crowd sizes and promising social guarantees: “Plaza Mayor Reventó de Gente: Apoyo Total Dio Pueblo a Fujimori” (“City Square Packed: People Give Fujimori Total Support”) and “Con Fuji Habrá Chamba y Bienestar Para Todos” (“With Fuji There Will Be Work and Welfare for All”).Footnote 32

But even more important, for Montesinos, than the tabloid press, were the television airwaves that extended across the country and reached the largest voter audience. As Taylor Boas points out:

Broadcast television was an obvious target for the Fujimori regime because of the political importance of the medium in Peru. Ninety-four percent of Peruvian residents and 91 percent of those in the next-to-lowest socioeconomic bracket had a television at home as of 1997 (Najar 1999, 360). For nearly two-thirds of the population, television remains the medium most frequently consulted for information about current events, as well as the most credible source of information (Tanaka and Zárate 2002).Footnote 33

Given this context, Montesinos mounted a comprehensive campaign to secure loyal TV coverage through payoffs and government favors. The editorial line of Channel 4, América Televisión, was co-opted by paying its owner, José Enrique Crousillat, monthly cash payments totaling $22,666,000 between 1999 and 2000.Footnote 34 The same transactional relationship was successfully established with other media magnates, including Mendel and Samuel Winter (Channel 2, Frecuencia Latina: $6 million), Ernesto Schütz (Channel 5, Panamericana Televisión: $10 million), Julio Vera Abad (Andina de Televisión, Channel 9: $50,000 [to fire two prominent journalists]), Vincente Silva Checa (Cable Canal de Noticias, Channel 10: $2 million) and Genaro Delgado Parker (Canal Red Global, Channel 13: paid with judicial and business favors).Footnote 35 These owners would quietly make sure that independent journalists and commentators were fired or their work curtailed, that positive coverage of the regime was highlighted, and that daily programming remained largely apolitical through the expansion of televisión basura (“trash TV”): sensationalist talk shows, crude sketch comedies, and game shows.Footnote 36 Only one cable news TV channel, Canal N, owned by El Comercio, remained independent during the period.

Through these measures the Fujimori–Montesinos regime, an authoritarian criminal political project with a neoliberal populist facade, relied on the construction of an illusionistic state apparatus constructed through the secretive yet pervasive capture of private media to guide and beguile a population emerging out of years of systemic crisis fueled by economic volatility, widespread insecurity, and failed governance. More specifically, this apparatus was aimed at projecting and disseminating two mutually reinforcing illusions: the impression of a diverse media environment, hence the importance of covert media capture; and the image of a popular democratic leader, hence the importance of overt support for the president from diverse editorial voices in print and television. The situation exemplifies how illusion, once it is institutionalized as part of the state apparatus, can be both distant from and constitutive of power, since it presents a far-removed image of the actual workings of the state, an illegitimate image, and yet is central to its perpetuation, a legitimating image.

In its sophisticated capture of Peru's media landscape and the widespread deployment of deceptive images and narratives, the Fujimori regime provides opportunity for a consideration of the role of illusion in contemporary politics. The power of illusion to manage publics has not been lost on theatre artists and thinkers. Bertolt Brecht addresses the topic in plays such as The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, where the title character, a satirical version of Adolf Hitler as a 1930s Chicago mobster, hires a Shakespearean actor to coach him on his public image. When the actor demonstrates a slow patrician stride, one of Ui's confidants warns, “Chief, you can't walk around like that in front of grocers. It's unnatural.” The mafia boss replies:

Ui: What's that mean, unnatural? No human being behaves natural these days. When I walk into that meeting tomorrow I don't want to look natural. I want them to notice that I'm walking in.Footnote 37

For Brecht's aspiring politician, the question of what comes natural is beside the point; what matters is the effect the illusion will have on others, the fact that they will “notice that I'm walking in.”Footnote 38 Within an economy of attention, to be noticed carries political value in itself. His deputy, however, warns that people will also notice the constructedness of the illusion, they will read the walk as fake or inauthentic. Brecht's scene thus encapsulates two perspectives on illusion. The first, which seems to be the adviser's position, assumes that illusions work when they are confused with reality, that their efficacy depends on how well they are grafted into the fabric of the real.Footnote 39 The second position, as argued by Ui, holds that illusions can work even if they are acknowledged as illusions. In this case it matters little if the walk seems exaggerated or forced; people will still be impressed by its effect. Marian Hobson makes a similar differentiation between what she terms bimodal and bipolar theories of illusion. In bimodal illusions, the spectator is aware of the illusion qua illusion even while participating in its effects. Conversely, bipolar illusions are considered to be, even if momentarily, entirely part of reality thus hiding any aspect of artificiality from the spectator. As Hobson argues, “‘Illusion’ will either cover the whole experience, the two parts being complementary and the mind oscillating between them (bimodal); or illusion will be applied to only one pole of the experience, which will never be contaminated by an awareness that art is art (bipolar).”Footnote 40 In other words, bipolar illusions hinge on their apparent commensurability with the real, whereas bimodal illusions rely on the conspicuous gap between appearance and reality as part of their basic dynamic. Hobson's distinction is useful in that it helps specify how illusions function across different political contexts. In liberal democracies, for example, where candidates attempt to establish relations of trust with the public under the scrutiny of a free press, there might be a greater propensity toward bipolar illusions: images, words, and narratives that can be camouflaged as part of social reality. In more authoritarian contexts, where attempts at trust are replaced by the disciplinary force of a repressive state and where press freedom is severely curtailed, bimodal illusions on a grander scale might be more prevalent, a situation where people know very well they are being deceived but even so are compelled to participate in the deception.Footnote 41 This distinction, as the Fujimori case suggests, is more heuristic than descriptive. The effect of a political illusion on the consciousness of an electorate at any given moment might involve shifting degrees of bimodality and bipolarity as well as changes in the underlying political order itself. Indeed, what we see between 1990 to 2000 in Peru is precisely a shift away from a roughly liberal democratic order to an increasingly repressive mafia state.Footnote 42 More important, through the secret capture of Peru's news media the image of El Chino, as a redemptory subaltern figure promising to guide the country through an exceptional situation, was mainstreamed into a broader neopopulist movement known as Fujimorismo, with a personality cult at its center, so as to mask and mediate this decadelong structural transformation.

The state's clandestine involvement in the manipulation of news broadcast media led to the emergence of what Peruvian scholar Rocio Silva Santisteban called tele-realidad (“telereality”): “Telereality is another strategy of neopopulism, that is, a populism exercised through the politics of [social] handouts in order to manage symbolically the cruelty of the neoliberal project while its plans continue to be implemented.”Footnote 43 Others, such as sociologist Manuel Dammert, have described the Fujimori–Montesinos state as an imagocracia (“imagocracy”):

A dictatorship that constructs and dominates the images of social life to perpetuate the hidden power of a corrupt mafia that keeps sterilized the vacuous institutions of representative democracy … its source of power lies in the domination of the image, whose representation alienates individuals. This social relation, converted into everyday routine and instituted as the vortex of social reproduction is the foundation of its existence as a dictatorship and the engine that calls for its perpetuation.Footnote 44

I would argue that categories such as tele-realidad and imagocracia could be understood in a more fundamental way through the concept of illusion, not only in that they present a false reality, which they certainly do, but also in the way these deceptive images and narratives invite citizens to play along with the illusion even if many recognize it as such.Footnote 45 For supporters of Fujimori, the increased dictatorial and corrupt character of the administration, if acknowledged at all, seemed to be a necessary price to pay for the stabilization of the country's economy and a renewed sense of national security. As political scientist Julio Carrión concludes in his analysis of public opinion at the time, “in Peru, the public was so grateful for the defeat of hyperinflation and domestic political violence that it overlooked the serious democratic deficits of a manipulative leader.”Footnote 46 This overlooking is akin to the bimodality identified by Hobson, where the spectator notices the artificiality behind the illusion and yet continues to be guided by its effects. Such illusions can function even while being acknowledged as deceptive. In other words, to the extent that illusions make manifest a desire for a particular social imaginary by making it momentarily real, they retain an aspirational quality.Footnote 47 This is evident in Romance languages, such as Spanish and Italian, where ilusión and illusione can also signify a hope or a wish.

Unlike the Platonic conception of illusion as simply a false appearance, illusions at an everyday level involve a much more nuanced, dynamic, and complex relationship to reality. In their ability to widen the horizon of the possible, illusions play with rather than simply negate reality. They lie closer to their etymological root, illūdere, from the Latin in- (“upon”) and lūdere (“play”), to play upon. To understand illusion as a playing upon reality requires a move beyond a static distinction between fact and fiction, since it suggests that illusions engage citizens not just as facts to be checked or interpretations to be accepted or contested, but as fantasies to be played out. In a highly adversarial political situation driven by the pressures of advocacy and polarization such as Peru's 2000 presidential elections, this playing upon reality can quickly overtake questions of veracity. This confluence of competition and simulation resembles the role of illusion in wrestling where, as Roland Barthes notes, “the public couldn't care less that the fight is or isn't fixed, and rightly so; the public confines itself to spectacle's primary virtue, which is to abolish all motives and all consequences; what matters to this public is not what it believes but what it sees.”Footnote 48 Similarly, in the political domain, illusions attempt to enthrall and absorb the citizen-player in such a way that they lose themselves in play, an effect seen in fan cultures whereby one's sense of self becomes increasingly attached to the illusion in order to be able to play along with it, and to enjoy doing so fully. Hence one might go from being a regular supporter of Real Madrid in Spain to become one of their fanatical Ultra militants, or in Japan one might go from being an avid reader of the manga Sailor Moon to dressing up as the eponymous character as part of cosplay competitions. That is why over the years many Peruvians had not just come to support Fujimori but had, more important, become fujimoristas.

The sophisticated deployment of illusions in politics through these developments in play behavior, marked by growing levels of simulation and competition, can produce an observable effect on a spectator's disposition and sense of self, if, as Hans-Georg Gadamer argues, at the level of subjectivity “all playing is a being-played.”Footnote 49 Understanding the ontology of illusion as a form of symbolically meaningful play helps explain how accusations of insincerity and dishonesty are not always enough to dispel the power of deceptive images or fictitious narratives in the sphere of politics, since one's sense of self might be wrapped up in the playing—what Gadamer identifies as “the primacy of play over the consciousness of the player.”Footnote 50 From an evolutionary perspective Katja Mellmann offers a similar reconceptualization of illusion as “immersively ‘illuded’ states of mind as a consequence of play behavior.”Footnote 51 This rethinking of illusion helps explain why, even with widespread reports of corruption and human rights violations, massive street protests, and growing political opposition the Fujimori regime as a regime of images still sustained a substantial degree of popular appeal throughout his third reelection campaign in 2000, even though the electoral process had been deeply fraught. In the end, Alejandro Toledo abstained from the race after widespread fraud allegations. After the election a violent suppression of protesters during Fujimori's swearing in ceremony left 197 people wounded, 35 missing, and 6 dead.Footnote 52 In private Montesinos described the period after the election as “a new phase of political warfare.”Footnote 53

By August 2000, after Fujimori's investiture, with opposition marches now a permanent fixture in the country's political landscape, the regime's image received an important political blow. A clandestine arms shipment originating from Jordan meant for the FARC in Colombia had been intercepted by Peruvian military forces, and the capture of the weapons was announced by Fujimori on television. The press conference was unusual, however, in that it included Montesinos, who in ten years of working for the government had rarely appeared in public. Montesinos's sudden visibility sparked curiosity, and soon further investigations into the arms shipment emerged. A Colombian investigative magazine revealed that the administration had not just intercepted the weapons but was an active profit-seeking intermediary figure in the regional arms trade.Footnote 54 Fujimori's hastily arranged press conference had been an attempt at preempting these revelations, which led, among other things, to a falling out with the United States. And still, even with all these factors at play and with a significant sector of the country's population now actively opposing the regime, Fujimori maintained an approval rating of 53 percent.Footnote 55

Vladivideos as Disillusion

A crucial turning point for the regime came in September 2000 when reporter Luis Iberico and opposition member Fernando Olivera convened a press conference at the Hotel Bolívar in Lima. Iberico announced to the journalists present that he had obtained a leaked video from the government.Footnote 56 Holding a VHS tape in his hands, he announced to the cameras, “this is something that has been said, well now we are going to see it,” and played the video.Footnote 57 Shot in full color inside Montesinos's own office at the National Intelligence Service, the video shows a set of brown leather couches around a coffee table enclosed by white walls, with a painting of fishing boats adorning the wall behind the couch on which two men are seated. The two men are Montesinos and Congressman Alberto Kouri (Figure 3). Wearing a blue short-sleeved shirt, Montesinos pulls out and counts USD 15,000 in cash, handing them to Kouri, who complains about the debt he has accumulated to fund his congressional campaign. As he hands Kouri the cash Montesinos advises him, “Here you go buddy, count, count it carefully.”Footnote 58 After Kouri pockets the money, Montesinos asks him for the date, writing down the transaction on a piece of paper for his own records. The whole scene takes less than two minutes. Earlier that same year, after winning a congressional seat, Kouri had been one of the tránsfugas who had switched from the legislative's main opposition party, Perú Posible, to Fujimori's party. The financial motivation behind his decision was now plainly evident from the leaked video.

Figure 3. Vladimiro Montesinos handing USD 15,000 in cash to Congressman Alberto Kouri in a video still from the first vladivideo.

After presenting the footage at the press conference, opposition members took it to Canal N, the sole remaining independent TV news channel. Canal N immediately broadcast the video, and soon its images were being seen around the country. The following day independent newspapers and magazines printed stills from the video and transcripts of the conversation between Kouri and Montesinos. During the next forty-eight hours “Fujimori convened new elections, in which he would not run; fired Montesinos; and promised to dismantle the SIN.”Footnote 59 Soon more videos—called vladivideos by the press based on their infamous protagonist—started coming out as it became evident that Montesinos had recorded every meeting in his office as part of an extensive surveillance apparatus. After being publicly dismissed, Montesinos went into hiding and then fled the country—first to Panama, then to Venezuela. He was later arrested and extradited back to Peru, where he is currently imprisoned in a maximum-security jail after being found guilty of influence peddling, abuse of power, corruption, conspiracy, and illicit enrichment, among other crimes.Footnote 60 Two months later, in November 2000, as his regime crumbled with more and more vladivideos being uncovered, Fujimori followed Montesinos into self-imposed exile in Japan under the pretense of an official visit to the region as part of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum. Fujimori sent his resignation letter via fax from Tokyo on 19 November 2000.Footnote 61

Meanwhile in Peru over the following months hundreds of vladivideos emerged showing an unending parade of members of congress, judges, journalists, election officials, military leaders, mayors, TV personalities, and print and broadcast media owners having dealings with Montesinos (Figure 4). Five years later, after the transition government of interim president Valentín Paniagua, from November 2000 to July 2001, had carried out a full investigation of all crimes committed during the Fujimori era, the ex-president traveled to Chile in an attempt to intervene and participate in the upcoming 2006 presidential elections in Peru. But his plans were foiled when, on account of the charges filed against him in Lima, Fujimori was arrested in Chile and extradited to Peru in September 2007 to face charges of gross human rights violations. These charges related to the massacres of Barrios Altos in 1991 and La Cantuta in 1992, where in total twenty-five civilians were executed and disappeared by Grupo Colina, a military death squad. Fujimori's trial in Lima began in December 2007 and lasted almost two years until his conviction by Peru's Supreme Court in 2009. The mega-juicio (“megatrial”), as it was dubbed by the Peruvian press, was televised in its entirety with particular segments highlighted every week in various news programs. Concerned with impartiality, transparency, and the country's polarization, Peru's Supreme Court and the prosecution felt it important to make sure all citizens had access to the process and to the facts of the case. For many Peruvians it was an unprecedented experience to see an ex-president stand trial in public view like other criminals. By 2009, Fujimori had been found guilty of human rights violations and was handed a twenty-five-year prison sentence, which he is currently serving.

Figure 4. Clockwise from upper left: Montesinos in business dealings with Genaro Delgado Parker (Canal Red Global, Channel 13), José Enrique Crousillat (América Televisión, Channel 4), Julio Vera Abad (Andina de Televisión, Channel 9), and magistrate Rómulo Muñoz Arce (member of Peru's National Jury of Elections). Photos: Courtesy El Comercio.

As this chronology attests, the appearance of the Kouri–Montesinos vladivideo was a key detonator in the collapse of the regime. Since fujimontesinismo was so invested in legitimizing itself at the level of the image, it was precisely at this level that it found itself most vulnerable. Writing alongside Debord's concept of the spectacle, the Retort collective identifies an analogous situation in the face of 9/11 as an image-event:

at the level of the image … the state is vulnerable; and that level is now fully part of, necessary to, the state's apparatus of self-reproduction. Terror can take over the image-machinery for a moment—and a moment, in the timeless echo chamber of the spectacle, may now eternally be all there is—and use it to amplify, reiterate, accumulate the sheer visible happening of defeat.Footnote 62

While the vladivideos also threatened the state at the level of the image, the terror they instilled did not emanate from some spectacular act of destruction from the outside but came instead “from inside the house.” The casualness of the conversations between Montesinos and his associates, the living room environment, and the home quality of the video images give the scene a domestic feel that speaks, not of some extraordinary conspiracy or nefarious criminal machination, but rather of everyday housekeeping chores, a kind of home economics that reflected the domesticity of government practice as a thoroughly informal affair, both private and privatized. The most poignant aspect of the videos was the feeling of absolute normalcy they conveyed, the slow and bureaucratic banality of evil: an army general here, an opposition congressman there, a TV talk-show host next.Footnote 63 All the videos are infused with this domestic atmosphere, an everyday aesthetic of the banal that, in its sheer repetition and accumulation, rose to become a revelatory saga of the inner workings of the state.

The spectacle was shaped by the tension between the ordinary nature of the encounters, relaxed chatter among collaborators; and the extraordinary nature of the project, the secretive construction of a corrupt dictatorial order. The gap between the banal and the astonishing reveals the psychopathology of the Fujimori–Montesinos regime as a set of social relations invested in the normalization of the abject, that is, in transforming practices such as drug trafficking, murder, blackmail, and corruption into normative techniques of government.Footnote 64 As later investigations would reveal, the regime was composed of three symbiotic “institutional mafias” or “greed rings”: one surrounding Montesinos and the SIN, another centered around Fujimori and his political allies, and a third connected with the business community and led by Finance Minister Jorge Camet.Footnote 65 Over time Montesinos's ring became the linchpin for the other two networks, and his precipitous downfall therefore brought about the collapse of the system as a whole. As the Waisman Commission, charged with investigating many of the videos, wrote in its report, “the evidence linking Montesinos and military figures to narcotrafficking and money laundering [was] of such magnitude that the commission was lead to conclude that Peru became a ‘narcostate’ during the Fujimori era.”Footnote 66 Weeks after Montesinos fled the country personal accounts under his name containing around $500 million USD were located in Switzerland, Panama, Jamaica, and the Cayman Islands.Footnote 67 Subsequent videos would give Peruvians even more details into the internal practices of the fujimontesinista “mafia state.”Footnote 68

Peruvians might have already been aware that the government was probably involved in some form of corrupt practice or another, as most had been before it. Investigative reporting by Ricardo Uceda, Gustavo Gorriti, and Cesar Hildebrandt, among others, had uncovered clear cases of corruption and criminal activity by the Fujimori regime at different moments throughout the 1990s.Footnote 69 But it was not until the purchase of political favors was made fully visible on TV—the same medium that Montesinos had most sought to dominate—that mass outrage directed at the state and Montesinos's criminal network could be mobilized. As Montesinos admitted during his trial, “if the fall of Kouri had not occurred the rest of events would not have unfolded.”Footnote 70 With the first vladivideo “what was set in motion,” historian Hugo Neira explains, “was not just the beginning of the end of a regime that without much tangible evidence was known to be corrupt, but rather, with the appearance of more videos, a scandalous chain reaction of accusations, resignations, politicians on the run, military officers in hiding, secret bank accounts in foreign countries, phantom companies created with dirty money.”Footnote 71

As the vladivideos scandal grew the carefully constructed illusion of the Fujimori presidency as a legitimate democratic government quickly began to collapse. The state within the state that Montesinos privately orchestrated was now not just visible, it was spectacular. And it is here, in the transformation of surveillance video into media spectacle that the politics of disillusion start to play out. As Brecht would articulate through his concept of Verfremdungseffekt, acts of disillusion are as important as any stage illusion, since they prompt a critical attitude in the audience oscillating between absorption and alienation to develop a dialectics of perception. In politics, however, as the emergence of the vladivideos makes clear, disillusion takes place in an unstable agonistic field, where figures are unmasked in front of others as part of political conflict. We can think for example of the secret video that appeared during the 2012 US presidential elections in which Republican candidate, Mitt Romney, speaking at a private fund-raiser, described 47 percent of the US electorate as people “who are dependent upon government, who believe that they are victims, who believe the government has a responsibility to care for them…. My job is not to worry about those people. I'll never convince them they should take personal responsibility and care for their lives.”Footnote 72 Recorded by a bartender at the event, the tape became known as the “47 Percent” video.Footnote 73 It received widespread criticism from across the political spectrum, not only damaging Romney's public character but also undermining the implicit myth behind his campaign slogan, “Believe in America.” The vladivideos prompted a similar unraveling, not just because the videos showed the falsity of the Fujimori administration as democratic and law-abiding, even though they did, but also because they inaugurated a counterplay that invited viewers to enter the drama of the private and to revel in it: Montesinos's office had now become a stage. In this sense, the vladivideos were not only ocular proof of corruption, they were also what Harun Farocki calls operative images, “images that do not represent an object, but rather are part of an operation.”Footnote 74 It is this operation that I am calling disillusion, an operation that draws its force not only from its ability to unmask political authority but also through its capacity to induce the transgressive play of watching obscene acts made public. Each video dispelled the carefully curated illusion of Fujimorismo by extending a new invitation for Peruvians to play in a dramaturgy of voyeurism, half peep show, half political thriller.

After the release of the first video the fallout from this engrossing political telenovela would spill into the nightly news every week. With more and more videos appearing—seven hundred found at Montesinos's private residence and more than sixteen hundred at the SIN—disillusion took the form of a continuous dramaturgical saga, revelation followed by revelation, an extended diegetic structure more like a serialized drama than a single incriminating snapshot. Like other incriminating cases of state violence, such as the 1991 Rodney King video in the United States, these transmissions also shared something of the traumatic. As Avital Ronell posits, “video captures no more than the debilitating discrepancy, always screened by television, between experience and meaning which Freud associated with trauma.”Footnote 75 This discrepancy was further complicated in that the order of the broadcasting of the videos did not follow their actual historic progression, that is to say, the video of the current week might actually be even older than the one broadcast last week. The participatory logic of the flashback thus came into play, inviting viewers to piece together each video so as to envision a cohesive timeline of characters and events. To aid this process newspapers and magazines published the transcripts so people could read along as the videos were broadcast (Figure 5).Footnote 76 The vladivideos also took then a literary form as dramatic scripts with lead characters, recurring guests, and Montesinos's office as a permanent set. Following the report of the Waisman Commission the Peruvian Congress published in 2004 the complete transcripts of the vladivideos in a six-volume edition of more than six thousand pages titled En la sala de la corrupción (In the Halls of Corruption).Footnote 77

Figure 5. Transcript of the first Kouri–Montesinos vladivideo as published in the newspaper La República on 15 September 2000.

It is as teleplay that disillusion suddenly descended on the Fujimori regime and its political actors, not as the disappearance of illusion but rather its displacement by a counterplay, an alternative visual dramaturgy that also hid as much as it revealed. As Gisela Cánepa has pointed out, while exposing the inner workings of the state, the vladivideos also produce a fictive notion of corruption as something done by others somewhere else as opposed to a systemic social practice that cuts across all levels of Peruvian society.Footnote 78 In their circulation as serialized television drama the vladivideos also function as an illusion to the extent that they allegorized corruption: Fujimori as the despot, Montesinos as the corrupter, his office as a villain's lair. In so doing they invisibilize corruption as what it is, a set of relations rather than a set of characters. What this allegorical move indicates is that acts of disillusion are not necessarily the opposite of illusion. In fact, illusion and disillusion are not simply synonymous with the fictive and the real; acts of disillusion might themselves propel other illusions. In his critique of Brecht's distancing effect, Adorno offers a similar observation, arguing that when Brecht “sabotages the poetic and approximates an empirical report, the actual result is by no means such a report: By the polemical rejection of the exalted lyrical tone, the empirical sentences translated into the aesthetic monad acquire an altogether different quality. The antilyrical tone and the estrangement of the appropriated facts are two sides of the same coin.”Footnote 79 The unmasking or dispelling of illusions in politics, as in the theatre, does not necessarily involve the disappearance of illusion; it points, rather, to a complex process of deconstruction through substitution, the emergence of a counterimage that plays against the underlying narrative of previous illusions. It is this sequence that helps explain the persistence of illusions across political contexts.

And yet, perhaps the starkest Brechtian moment in the whole vladivideos scandal was when viewers watched TV station owners taking payoffs and editorial instructions from Montesinos. With these scenes the illusion of a diverse media environment also disintegrated. For example, on 10 November 1999 at the height of Fujimori's third election campaign, here is Montesinos discussing how to manage independent journalists with Ernesto Schütz, the president of Panamericana Televisión (Channel 5):

Mr. Montesinos: Can [you trust] a journalist do what is right?

Mr. Schütz: No, you check to see if something comes out, when you … if something comes out you tell them: “No, no, you can't put this out.” And that's free enterprise.

Mr. Montesinos: Of course, logical.

Mr. Schütz: [unintelligible] They are not going to tell us stories.

Mr. Montesinos: We know …Footnote 80

These scenes in particular forced a reflection on the production of illusion itself, creating a situation where citizens watched on television the way television was being used to produce the narratives of fujimontesinismo. These moments of metatelevisuality made some Fujimori supporters aware that in playing along with the regime's vision they themselves had been played, in a scenario resembling what Richard Schechner calls “dark play”: a situation “when some or even all of the players don't know they are playing … as in spying, con games, undercover actions, and double agentry.”Footnote 81 The specular inversion caused by the leaking of the vladivideos, which turned private government surveillance into public state spectacle, not only exposed the widespread clientelism and systemic corruption behind the liberal technocratic facade of the Fujimori administration, it also revealed how illusion and disillusion play out politically. New technologies, as the vladivideos make clear, are reconfiguring the state's capacity to control its image. While early adoptions of radio and television by governments functioned as relays and amplifiers of traditional state-sanctioned performances—the fireside chat, the stump speech, the military march, the swearing of the oath—new modalities of capture and distribution are compromising the state's capacity to police its own visual narrative, since every private fund-raising speech is open to surreptitious recording, and every act of surveillance is now a spectacle in potential. In this way the vladivideos also problematize common conceptions of surveillance: if surveillance is about deterring crime by extending the gaze of the state, here surveillance is constitutive of the criminal apparatus; if surveillance is about fortifying the state, here surveillance causes the state to implode; if surveillance is the opposite of spectacle, here surveillance is made manifest as spectacle. It is here that the hidden cameras of Montesinos differ from the kind of system that Foucault identifies as panopticism, since those visiting his office did not know they were being recorded: only Montesinos and some of his closest staffers were aware of this operation.Footnote 82 Theories as to why Montesinos diligently recorded his meetings have run the gamut from the strategic—blackmail, deterrence, accounting, diary keeping—to the psychoanalytic—sadistic pleasure and voyeuristic narcissism.Footnote 83 These recordings are the arcana imperii of Montesinos's surveillance, an overleveraged sovereignty that exceeds the utilitarian rationality of the “scientifico-disciplinary mechanisms” Foucault articulates in Discipline and Punish.Footnote 84

If new technologies of mass communication have amplified the state's illusions, they are also making them increasingly unstable. In the illusionistic machine of the Fujimori–Montesinos regime, spectacle and surveillance are two sides of the same coin, illusion and disillusion, an oscillating visual economy that can be calibrated and inverted but hardly extinguished. Their persistence in the realm of politics can be explained by thinking of illusion and disillusion as forms of play and counterplay, an approach that moves beyond the untenable position of awaiting a politics devoid of illusion. The vladivideos not only exposed the true interests of powerful political actors, they also revealed the underlying dynamic structuring the mediatization of the regime as a mode of dark play that thrived on competition and simulation.Footnote 85 The politics of disillusion worked not by commenting on the Fujimori–Montesinos illusionistic apparatus but simply by replacing it with a more powerful visual narrative. This new narrative was, at an empirical level, closer to reality; but perhaps more important, at the level of play, it presented its viewers with a more attractive playing field that offered a powerful ensemble of transgressive pleasure, civic participation, and political drama. In effect, the play of illusion was met with the counterplay of disillusion—“two sides,” as Adorno notes, “of the same coin.”