In 1936, three penal camps, aimed at progressing roadworks, were established in the Senegalese colony, part of French West Africa (FWA) at that time. The penal camps were viewed as a way to decongest overpopulated civil prisons and to use convict workers – who were colonial subjects – on public construction sites in order to minimize labour costs. In contrast with the ideal held by the European penitentiary,Footnote 1 the main goal of Senegalese penal camps was not the moral rehabilitation of prisoners, but rather the creation of a pool of workers for road maintenance in the context of the mise en valeur Footnote 2 of the French Empire. In that sense, I follow the analysis of Christopher Gray, who argues that the physical manifestation of the colonial territoriality was expressed, above all, by roadworks. Physical in a dual sense: in terms of the modification of the landscape, but also in terms of the physical labour imposed on local populations.Footnote 3

As Babacar Bâ has shown,Footnote 4 mobile penal camps were set up as part of a colonial penal system that emerged relatively early in Senegal, at the end of the eighteenth century, and then developed concurrently with the gradual implementation of a civil administration in the colonized territory. In contrast to previous forms of punishment, often physical and seen as barbaric by French colonial officials, prisons appear in this context as a common type of criminal penalty and a tool for the “civilizing mission”.Footnote 5 Nevertheless, the colonial prison should not be reduced to the simple importation of the metropolitan model to the colonies. Although colonial confinement emerged from diverse thoughts, ideologies, and practices that have circulated at a global level, the colonial model of prison was constantly adapted, reinvented, and recomposed at the whim of local situations. Consequently, it produced a large variety of hybrid models of prisons with diversified functions. In Senegal, for instance, penal campsFootnote 6 were part of a diverse penitentiary landscape, including civil prisons, detention houses, juvenile reform houses, and military detention centres.

The vast body of literature on studies of confinement in Africa and in imperial contexts attests that colonial prison as a form of punishment was used as a tool of permanent conquest.Footnote 7 In contrast to metropolitan jails, which defined individuals as citizens and legal subjects, colonial confinement treated local populations as objects and “subjects” of political, cultural, and economic power. Specifically, the economic dimension of the colonial prison appears to be central.Footnote 8 Although literature has emerged in recent years on convict labour in a global context,Footnote 9 the historiography remains quite silent on this theme in French African colonies, penal labour being considered marginal or non-specific to the colonial situation.Footnote 10 Yet, the labour question was a major issue for the colonial enterprise, which had erected coercive and repressive forms of labour regulation as the keystone of the colonial political economy.Footnote 11 Under the French colonial empire, indigénat became a central instrument for managing and controlling the African labour force through massive imprisonment and requisition.Footnote 12

Indeed, the “massification”Footnote 13 of confinement was especially advantageous for the colonial economy, since the decree of 22 January 1927 in FWA obliged convicts to work for the colonial administration.Footnote 14 In addition to the chores carried out inside the prison (supplying water, cutting firewood, cleaning, etc.), prisoners were subjected to various extra mural tasks. The Ziguinchor prison's report of 1945 indicates, for instance, that convicts were used to supply drinking water to the various command posts, or to clean ditches to ensure the flow of water through the city's streets.Footnote 15 As a cheap pool of workers, convicts were therefore largely used for the colonial mise en valeur. In the specific case of Senegalese penal camps, penal labourers made a significant contribution to the development of roads. The Governor of Senegal himself underlined the benefits of such a system in a letter addressed to the General Governor of FWA: “mobile penal camps provide a major service for the road renovation in the colony”.Footnote 16

This article aims to shed new light on the history of confinement and penal labour in an imperial context by proposing a fine-grain history of the daily running of Senegalese penal camps and the living and working conditions of convicts through the framework of mobility. Senegalese penal camps were far from “the protected place of disciplinary monotony”Footnote 17 dear to Foucault; instead, they were a space of multiple and antagonistic forms of mobility in and out of the penal system. Following the goal at the core of this special theme, this contribution aims at providing an analysis of punishment that crosses the borders between penal sites and society, transcending the vision of the colonial prison as a “world apart”. More broadly, this article inscribes this peculiar penal site into wider political, economic, and cultural issues.

The pioneering work of Ibra Sene has shown the economic function of the Senegalese penal system, and he described the legal organization and institutional functioning of the penal camps in a renowned article that appeared in 2004.Footnote 18 Nevertheless, Sene evokes only briefly the conditions under which convicts were living on a daily basis. I argue in this article that looking at this peculiar form of confinement through the framework of mobility offers an original perspective to highlight the degrading and hazardous living and working conditions that were at the core of everyday life in Senegalese penal camps. By forcing convicts to work for the colonial mise en valeur, to what extent did the daily functioning of penal camps blur the boundary between the carceral sphere and colonial society? How did the constant mobility of the penal camps influence the daily living and working conditions of penal labourers?

Furthermore, this article outlines the moving borders of the penal camps and analyses for the first time the multiplicity of ways in which these borders could be permeated. This approach allows one to underline the agency of inmates. What kind of reactions emerged among prisoners in order to refuse to work and to escape the penal system? More broadly, to what degree did these strategies of self-help throw a spanner in the works of the daily running of penal camps? Convicts were not just passive objects of information (to use Foucault's terminology), but also agents who attempted to be active subjects of their own history by reacting and challenging repressive and disciplining colonial policies on a daily basis.

This article is organized into three parts. The first considers the penal camps as spaces of constant mobility, where convicts with long-term sentences were sent from civil prisons and compelled to work outside the prison on road maintenance and to move with the penal camp to the next construction site. I argue that mobile penal camps were at the core of a colonial tension between the need to control and lock down people and the colonial obsession with putting local populations to work. This tension underlines the specificity of the colonial political economy, which was focused, above all, on the coercive use of workers and minimizing labour costs. In the second, I assert that forced labour and forced mobility as central features of Senegalese penal camps played an important role in the daily hazardous working and living conditions of convict labourers. The penal camps were constantly moving and the lack of basic hygiene conditions constituted a degrading space for both the physical and mental health of prisoners. Finally, I shed light on the multiple tacticsFootnote 19 used by convict labourers to refuse to work. Prisoners were not unresponsive and reacted diversely to these hard conditions. From settling their family next to the camps, breakout, being declared sick, or self-mutilation, I show how these individual and intentional forms of mobility – as well as forms of immobility – threw sand in the gears of the day-to-day functioning of Senegalese penal camps and, more broadly, in the colonial project of mise en valeur.

ROAD-BUILDING AND PENAL LABOUR: MOBILE PENAL CAMPS AS A TOOL OF MISE EN VALEUR

Since the late 1920s, the running of prisons in Senegal had attracted widespread criticism: the jails were completely overcrowded and convicts were escaping on a massive scale. Many district administrators (Commandant de cercle) complained about the number of detainees vis-à-vis the total capacity of prisons. In 1929, for instance, the district administrator of Baol, in the centre of the Senegalese territory, reported that he could not accommodate all the convicts and called for the local prison to be extended: “I find myself obliged to let outside of the prison around twenty-five prisoners. Surveillance is then practically impossible”.Footnote 20 Babacar Bâ notes that in 1927, of the 1,000 detainees in Senegalese prisons 422 cases of jailbreak were reported, some of which were carried out by the same convicts.Footnote 21 This situation pushed the colonial administration to launch an inquiry the same year in order to reorganize the security of the detention facilities.Footnote 22 Consequently, a decree sanctioning the offence of jailbreak was issued in November 1927.Footnote 23

Therefore, in May 1936, an important review of the Senegalese penal system was launched by the colonial inspector Montguillot in order to resolve the problem of how Senegalese prisons were to be run. In his report, he called for a major reform of the Senegalese penal system by making more efficient use of the penal workforce. The report recommended reorganizing penal labour by setting up three mobile penal camps, each comprising around one hundred convicts.Footnote 24 The main idea was to gather convicts at the same place for better surveillance and to ensure an efficient use of this cheap labour force for road maintenance. In Montguillot's words, regarding the road situation, road maintenance could “provide work for ages”.Footnote 25 The aim of mobile penal camps was twofold: to decongest civil prisons of long-term prisoners and to make them work on the public construction sites of the territory.

A decree was passed in January 1939 to regulate the functioning of the mobile penal camps, which were “moving along the roads, according to work requirements”.Footnote 26 Detainees sentenced to more than one year in jail were sent to one of the three mobile penal camps, according to the length of their sentence. Penal camp A, located in the Thiès region, accommodated prisoners serving a jail sentence of less than five years. Penal camp B, situated in the Kaolack region, took detainees serving more than five years. Finally, the “diehards”, recidivists, and most dangerous convicts were placed in penal camp C, located in the Louga region.Footnote 27 The three mobile penal camps were located in strategic places in the Senegalese territory, between Dakar and Saint-Louis, the two political main cities, and the Sine-Saloum region (Kaolack), the heart of the groundnut economy, the main cash crop produced by the colony (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of Senegal and location of the penal camps.

In theory, splitting up the convicts according to the length of their sentence was something new in the daily organization of the colonial prison in Senegal. Previously, no distinction had been made between convicts condemned to short-term and long-term sentences. The Governor of Senegal explained this new measure in these terms: “The fear of hard labour is the only way to prevent [the convict] from ‘doing wrong’ [mal faire]. His transfer to a penal camp then becomes a necessity. Besides, if the convict stays in a civil prison, he might be a negative influence on petty delinquents”.Footnote 28

The colonial administration wanted to avoid any risk of “collusion” with convicts for which there “remained a hope for redemption”.Footnote 29 Nevertheless, the reality was quite different and regulation infringements were common since the priority of the penal camps was to maintain a sustainable number of convicts to provide enough workers for road maintenance. District administrator Carcassonne, in charge of penal camp A, remarked, for instance, that “no distinction is made between defendant and convict”Footnote 30 in the camp. It was also usual to see petty criminals transferred to penal camp C, still restricted to long-term convicts, according to the work requirements.Footnote 31

Colonial penal camps were initially thought to accommodate around one hundred convicts each.Footnote 32 Nevertheless, a colonial report estimated in 1936 that, within two years, 150 convict labourers would be necessary in penal camp C for the one-hundred-kilometre roadworks between Louga and Tivouane.Footnote 33 The same report also complained about the limited number of convicts condemned to more than one year in jail, a sine qua non for being transferred to a penal camp: “in the colony there are only 461 convicts serving jail sentences in Senegalese civil prisons of more than twelve months […]. Under these conditions […], it is impossible to operate massive transfers of convicts to penal camps”.Footnote 34

In a context where the Senegalese colony, autonomous financially, lived on a tight budget, the use of penal workers was aimed at minimizing the expense of road maintenance at all costs. A particularly interesting colonial report demonstrates with precise calculations the economic benefit of the penal camps and penal labour in the colony. Considering that the productivity of each penal camp was 100 kilometres of road maintenance per year, the document estimated the maintenance of each penal camp at 300,000 francs per year, including the food for prisoners, the guards’ salaries, and the cost of moving the camp to the next worksite. The report compared this with the cost of 100 kilometres of road maintenance by a private company, estimated at 625,000 francs, more than twice as much as the penal camp cost.Footnote 35

In his convincing demonstration of the economic function of penal camps, Ibra Sene argues that the “chronic shortage” of labour in the Senegalese colony “deeply influenced” the organization and setting of penal camps.Footnote 36 Rather than the shortage of workers, which was a rhetorical argument used by colonial authorities to overshadow their incapacity to create favourable conditions to hire and fix a voluntary labour force on the worksites, the implementation of Senegalese penal camps has to be understood within a specific political and economic international context regarding forced labour. In the French Empire, roadwork was initially done by forced labourers compelled to perform a number of days of prestation, a tax to be paid in labour in addition to taxes paid in cash. Within the context of the Geneva Conference on forced labour in 1929, the prestation system was criticized by the International Labour Office (ILO) and French officials feared that this form of obligatory labour was going to be forbidden. So, setting up mobile penal camps appeared to be a strategy adopted by French colonial officials to deal tactfully with international actors and public opinion and to continue to coerce large groups of labourers into road construction. The benefit was threefold: first, the system of penal camps shielded colonial powers from international criticism about forced labour, since penal labour was tolerated by the ILO.Footnote 37 Second, penal camps provided a considerable number of free workers for road construction in a colony where the number of days of prestation was low (four days a year in Senegal). Third, penal camps ensured a labour force in the event of the prestation system being abolished, which was the case in 1937 under the Popular Front.Footnote 38

Indeed, prisoners appear as a cheap but also as a productive labour force. At first glance, one might think that around one hundred convicts per camp was a small number given the work to be done on road sites. Nevertheless, if we compare the work done by convict labourers in each region where a penal camp was implemented with the work done by prestataires, we find that over twenty-five per cent of the road maintenance was conducted by convict labourers.Footnote 39 Thus, penal camps and convict labour were not only an ideological tool within the context of mise en valeur, they also provided a significant economic advantage for the colonial administration.

FORCED MOBILITY AND FORCED LABOUR: LIVING AND WORKING IN A SENEGALESE PENAL CAMP

Penal camps moved from one construction site to another several times a year, depending on the duration of the roadworks. The constant mobility of the convicts, first sent from civil prison to penal camp, then in and out of the penal camp, as well as the moving of the camp, played a determinant role in the daily working and living conditions of the detainees. In accordance with penal camp regulations, all prisoners sent to a penal camp were to undergo a thorough medical examination.Footnote 40 The January 1939 decree was clear: “all convicts who are transferred to a penal camp must be of robust constitution and in sufficient health to allow them to withstand tiring labour”.Footnote 41 Nevertheless, in the penal camp it was common to find many convicts physically unsuited to such hard labour, often performed in hazardous conditions.

Penal workers were compelled to work ten hours a day with a daily break of ninety minutes, the whole year, except Sundays and holidays. They walked dozens of kilometres per day to reach the worksites, mostly located in remote areas. An internal report on penal camp C indicates that convicts had to leave the camp at 6.40 a.m. every day to reach the construction site seven kilometres away.Footnote 42 They spent the day crushing and carrying laterite extracted from neighbouring quarries to extend the road network and walked back to the penal camp at nightfall. They worked without special tools in these hazardous conditions and work accidents were common. In 1940, we read in an incident report that two detainees, Antoine Preira and Adolphe Ternel, cut themselves badly with an axe while chopping logs for the roadwork.Footnote 43 It is interesting to note the reaction of the penal camp director, who mentions explicitly in his report that work accidents were “usual and normal with heavy-handed and inept individuals”.Footnote 44 This remark recalls the typical colonial rhetoric that infantilized colonized populations, depicting them as childlike and clumsy.

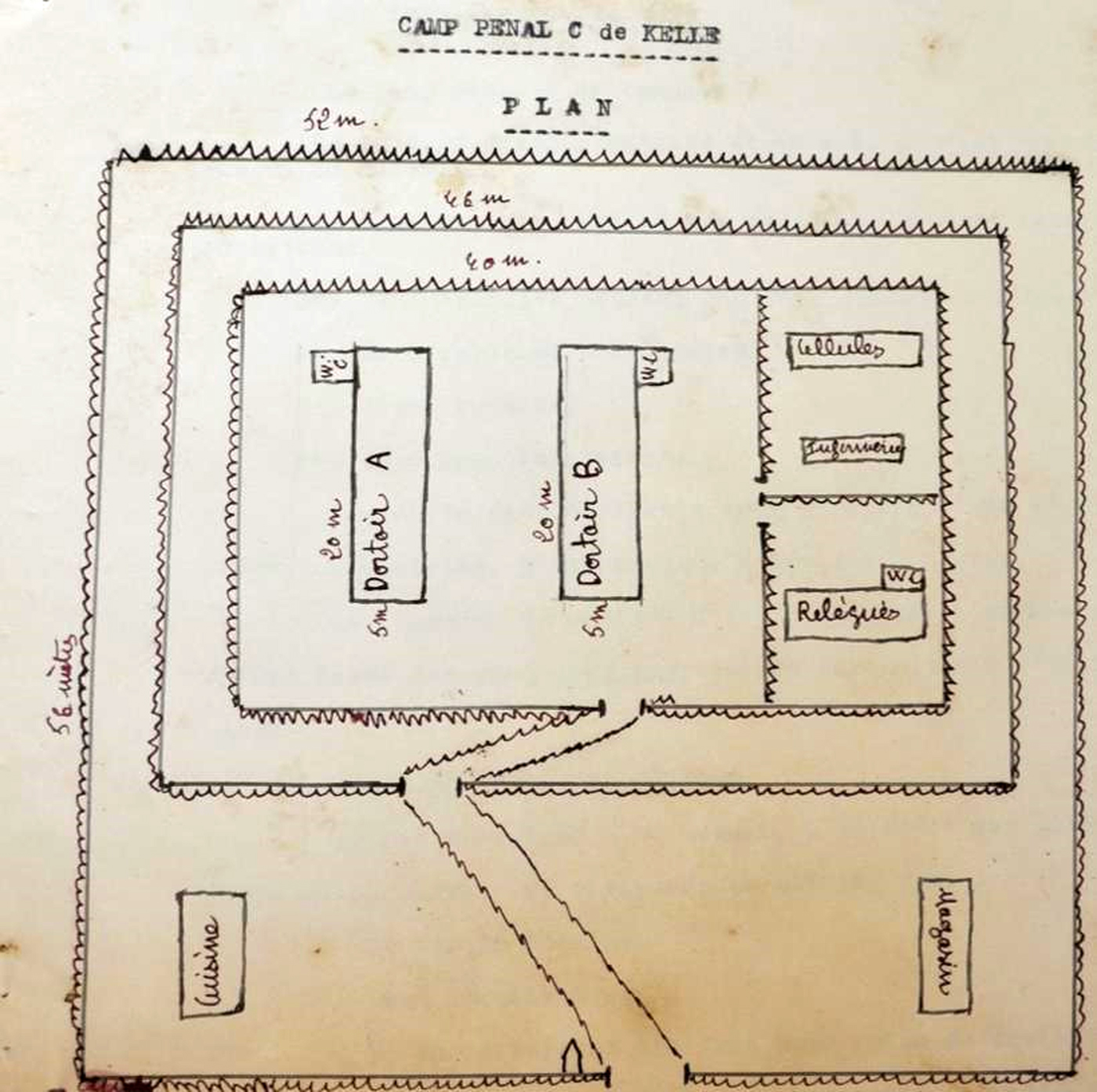

A far cry from the panoptic plan of the Foucauldian jail, the architecture of the Senegalese penal camps remained rudimentary since it needed to comply with the necessity to move the camp rapidly and at minimum cost. As the director of penal camp C (Figure 2) indicated, this type of jail, located in the bush, made out of a removable structure, could not provide “the necessary guarantee of security and repression that a prison built with proper construction material, cells, and a high enclosure wall could”.Footnote 45 For instance, penal camp C was protected by only three rows of barbed wire and, at night, the prison guards had a dozen attack dogs in the courtyard to prevent a jailbreak.Footnote 46 Moreover, the living conditions of the detainees were extremely basic. Mobile penal camps consisted of two wooden shacks, used as dormitories, twenty metres long and five metres wide. More than one hundred convicts were holed up in the camps with no light. The prisoners, leaving the penal camp at sunrise and coming back at nightfall, spent most of their break time in darkness. Visits were theoretically authorized once a month but largely dependent on the goodwill of the jail guards or the penal camp director.Footnote 47

Figure 2. Map of penal camp C.

The report of an unannounced inspection of penal camp C in 1942 sums up the everyday violence of the working and living conditions in which the prisoners were forced to survive. The military officer in charge of the inspection remarked that “more than half the convicts had suppurating wounds or freshly healed scars on their shoulders, arms, back, and sometimes on the inner part of the thigh”.Footnote 48 The report noted three distinctive origins for these wounds. First, the permanent friction of buckets, rails, or tools on penal workers’ skin left them with deep cuts. Second, the wounds on the inner part of the thigh came from the intensive scratching of the skin caused by the vermin that proliferated in the penal camp dormitories. Finally, a number of scars resulted from beatings or abuse by the guards. The daily life in the camp was so harsh that the police officer concluded his report with this sentence: “the convicts are total wrecks who are irrevocably condemned to a slow death”.Footnote 49

Several letters of complaint sent to the Governor of Senegal also report the hazardous hygienic and living conditions in the camp. A collective petition from the detainees of penal camp C warns of the nutritional deficiency of the everyday ration – “only boiled maize in warm water with no fat”,Footnote 50 the lack of clothes and sheets for bedding, and the gradual degradation of both the physical and mental health of the convicts. It is important to note that the complaints formulated by the detainees are a direct criticism of their living conditions but are also addressed at a moral level. Indeed, petitions written by convicts form a dialectic of reciprocity, of respect for dignity, calling on the colonial administration to respect convicts’ basic rights:

We are ready to obey, but on the one condition that you respect our rights in accordance with the local regulations. The functioning of the penal camp will be improved and the daily life at the camp will remain calm, for the authority, for the guards, and also for the detainees. We will enforce our rights, despite the risk of death.Footnote 51

How could these letters bypass the censorship of the director of the penal camp? In reality, a number of letters received by the Governor of Senegal appeared to have been written not by the prisoners themselves, but by individuals outside the prison. For instance, on 2 April 1939, a letter signed by Souleymane Diakité was the exact reproduction of an old claim received a few months earlier and signed with the name of another prisoner. After an investigation conducted by the Chief of Louga's district, the colonial official concluded that a “Kébémer scholar” (lettré de Kébémer) had written it.Footnote 52

These petitions raise two important points. First, convicts did not remain unresponsive and reacted – in various ways – to their hard living and working conditions. Second, the porosity of colonial penal camps helped convicts to develop relations and collude with people on the outside.

FROM ESCAPE TO SELF-MUTILATION: MOBILITY/IMMOBILITY AS AN EVERYDAY FORM OF REACTION

Facilitated by the minimal surveillance of the buildings and the everyday exit of convicts from the penal camp to construction sites, various forms of self-help or refusal appeared. In 1938, the chief of the Kébémer district (where penal camp C was located) noted in an inspection report:

[…] Every time I inspect the district, I see detainees coming in from any road at any time; every time I asked the chief sergeant (brigadier-chef) where they came from, he says, “That's the water chore coming in”. It seems to me that the water chore serves as a discharge for many prisoners who want to get out of the penal camp, without being watched over by guards.Footnote 53

This instance shows how convict labourers used the lack of surveillance outside the camp to offer themselves a brief respite from the everyday harsh living and working conditions. Then, one might ask, how is it possible that prisoners, who are left free to move around all day and thus have all the latitude to escape, seemed to return to the penal camp at nightfall? The same inspection report adds another interesting detail on that matter. The district chief notes that several detainees managed to have their families settle with them. It was therefore possible for them to spend the day outside and see their family and then return home to spend the night in prison:

Many prisoners have settled their families, mainly their wives, near the camp […] and in neighbouring villages. All this world is trafficking, making small-scale trade, riding the prisoners’ coattails, or, on the contrary, helping them.Footnote 54

Breakout remained the most common form of protest used by penal workers in response to harsh living and working conditions. During the whole of 1938, of a total of 116 convicts in penal camp C thirteen escaped – equivalent to around ten percent of the total workforce.Footnote 55 In 1939, again in penal camp C, seven convicts escaped between 4 and 12 May. On 4 May, six detainees, three of them chained, escaped from the construction site without any action being taken by the construction supervisor. On 12 May, a chained convict managed to steal a guard's horse to escape from the worksite.Footnote 56 Fleeing the penal camp appears to have been an intentional and individual form of mobility that contrasts with the forced and collective mobility at the core of how the penal camp system was run.Footnote 57

In order to solve the problem caused by these repeated breakouts, especially in a camp full of “diehard” inmates, a lengthy inquiry was launched by the Senegalese Inspectorate of Administrative Affairs. At that time, penal camp C was located a few kilometres from Louga and the colonial administration feared that the fugitives might constitute a great danger to the population of the city. Thus, the inquiry report suggested stopping using the penal camp as a pool of workers and moving it to an arid and scarcely populated region on the border with Mauritania, 150 kilometres north. The goal was to transfer the dangerous convicts to an “area where discipline could be rigorously observed and where any escape would be, if not impossible, at least really dangerous for those who want to try”.Footnote 58 As in other colonial contexts highlighted in this Special Issue, colonial authorities used the arid geography of the Senegalese colony to isolate the prisoners. In the present case, French colonial officials could not confine the most dangerous convicts on an island for instance, but they could suggest sending them to a hostile and desert landscape to avoid any jailbreak. This project never came to pass, but it is interesting to note that the considerable number of prisoner breakouts forced the colonial authorities to at least review their goals by giving priority not only to the economic benefit provided by penal workers, but also to security needs and surveillance.

Furthermore, various responses within the penal camp also threw sand in the gears of the day-to-day running of this space of confinement. The detainees often went to the penal camp doctor to be declared unfit for work. If the incapacity lasted more than a few weeks, they could even be sent back to the civil prison, where they were not compelled to work every day in difficult conditions. It has to be said that the penal camp regulations opened a loophole, allowing convicts to be declared unfit and so avoid roadwork outside the jail. Indeed, article 50 of the January 1939 decree states that, in the case of sickness or exhaustion, “the convicts could, for a short period of time, be exempted from forced labour by the penal camp director”.Footnote 59

In 1942, a report from the director of penal camp C noted that the convict Soumah Diouf had announced, in the presence of fellow detainees, that “he would be declared sick to avoid working and, if this strategy was not successful, he would refuse to work”.Footnote 60 A similar case occurred a week later. The convict Mamadou Barry asked to be examined by the doctor every day for five days in order to be declared sick. Each time, the doctor considered Mamadou Barry fit enough to work. Barry therefore refused to work. Consequently, he was sent to an isolation cell, enchained, and deprived of light and basic needs for a week.Footnote 61 Even if it is hard to track down all the cases in the archives, this form of protest should not be underestimated. A colonial report on the running of penal camp C in 1940 sheds light on the negative consequences of such action: “the actual number of penal workers is clearly insufficient for the rapid progress of road maintenance. Only 40 to 45 convicts out of 100 are sent to the construction site; the others are sick”.Footnote 62

Some more extreme reactions can also be observed in the penal camps, in response to the inhuman working and living conditions. Some convicts stopped to tend their wounds and sometimes even committed suicide,Footnote 63 others started to mutilate themselves.Footnote 64 A few cases of self-injury occurred in similar conditions. In June 1940, the convict Magueye Guèye was accused by a construction supervisor of having placed “his left hand under the wheels of a trolley”, causing a deep wound.Footnote 65 It was the same scenario with Mamadou Thiam, who stuck his hand between the frame of the trolley and the skip on 11 July 1940. An incident report notes “multiple wounds of a certain severity”.Footnote 66 Two weeks later, the convict Mamadou Bâ was also injured by a trolley, in his foot “in which the big toe was cut”.Footnote 67 Colonial authorities were aware that some of the convicts “used to mutilate themselves in order to escape hard labour on roads and to be transferred to civil prisons”.Footnote 68 These acts of self-mutilation are reminiscent of practices often used during the slave trade.Footnote 69 The mutilation of the body – becoming a space of resistance – by penal workers caused negative economic consequences for the colonial administration since the productivity of the penal camps was dependent upon the physical fitness of convicts and their aptitude for work. Moreover, these extreme forms of reaction show how horrendous living and working conditions were in the penal camps.

In contrast to jailbreaking, which we can see as an intentional form of mobility, being declared sick or self-mutilation underlines forms of immobility as everyday tactics used by prisoners to refuse the working and living conditions in the labour camps. More broadly, these attitudes of “inactivity” challenged the day-to-day running of the penal camp, since the constant mobility in and out of the prison for road maintenance was at the core of the system.

CONCLUSION

Experimented from the late 1930s, Senegalese penal camps were shut down on the eve of Senegalese independence, in the late 1950s, ten years after the Houphoüet-Boigny Law that abolished forced labour in French African colonies.Footnote 70 At first sight, an analysis that focuses exclusively on Senegalese penal camps might appear a bit restricted. Only three penal camps were created in the whole of Senegal, each containing around one hundred convict labourers and lasting for less than twenty years. Nevertheless, examined through the framework of mobility, the context of setting up the Senegalese penal camps and their daily running allows for the re-evaluation of penal practices on a global scale.

In this article, mobility has been analysed as a possibility to both connect and transgress borders between the site of confinement and the outside world. First, the forced mobility of convict labourers that was at the core of the functioning of Senegalese penal camps raised a central tension in colonial confinement. As summarized by a French colonial official, the ideal of the penal camp was to “obtain from prisoners both the productivity and the quality of the work done, while maintaining them in a small space to ensure surveillance continues to be efficient”.Footnote 71 However, the economic function of the penal camp for the mise en valeur was prioritized over the ideal of surveillance and moral rehabilitation of the convicts. The Senegalese penal camp was both a place of confinement and a place of circulation for convicts who constantly moved out of the prison for roadwork. The use of convict labourers outside the penal camp therefore made obsolete what Florence Bernault called the divide between the space of law (the penal camp) and the space of sovereignty (outside the penal camp).Footnote 72 Moreover, the use of penal camps as pools of workers for road maintenance recalls that labour was the mainstay of the French Empire's political economy. The case of mobile penal camps in Senegal bridges the gap between penal labour and labour history, and highlights convict labour as one of the multiple labour relations that punctuated the colonial episode. It is especially the case in the specific context of the late 1920s, when forced labour in the colonies began to attract widespread criticism on the global scene. The intensive use of convict labour in the French colonies allowed colonial officials to continue the use of costless and involuntary workers while appeasing international opinion since convict labour was tolerated.

Second, giving priority to the mise en valeur and the minimization of costs, the French colonial administration in Senegal confined hundreds of prisoners in penal camps whose living and working conditions were degrading and hazardous. Forced mobility and forced labour created a fertile ground for the development of forms of resistance. Some convicts offered themselves a brief respite by wandering outside or by settling their family next to the penal camp; others escaped the penal camp while working on the construction site or declared themselves sick in order to be sent back to civil prisons, where they were not compelled to work every day on road maintenance in tiring conditions. Some of them were even ready to mutilate themselves to avoid roadwork. In this context, mobility and immobility appear to have been not only coercive but also intentional, and used by convicts in order to refuse to work. This range of multiple tactics challenged on a daily basis the prison space order that convicts were subjected to and allows us to transcend the vision of the punitive institutions as simply “archipelagos” or “worlds apart”. Finally, the focus on Senegalese penal camps shows the complex ways in which colonized populations reacted to and negotiated daily colonial coercion. More broadly, it opens the field for more in-depth socio-historical analysis that tackles irrationalities, contradictions, and anxieties in colonial punishment.Footnote 73