In June 1949, Leo Negrelli and Oswald Mosley met in Madrid. After several attempts, the Italian journalist and the British politician had finally managed to arrange a brief encounter in the Spanish capital to discuss a series of issues which would be crucial for the future development of the extreme right in Europe.Footnote 1 With the pretence of finding publishing houses that could sell Mosley's latest book, The Alternative, in the Spanish market, the two had actually gathered to accelerate the evolution of the organisation of some sort of ‘European unity’ for the far right.Footnote 2 This was hardly new for either of them; Negrelli had been fighting for the ‘cause’ since his arrival in Madrid in the summer of 1945, after a period in Lisbon where he had been the diplomatic attaché to the Repubblica Sociale Italiana (RSI).Footnote 3 On the other hand, Mosley, after realising that his career in British politics had come to a halt, had decided to travel to Madrid as the first stage of a tour around Europe to sound out the possibility of leading a pan-European neofascist movement.Footnote 4

It was no coincidence that encounter took place in Madrid. By the end of the 1940s, the Spanish capital had become a common meeting point for former fascists from around the world. The number of right-wing extremists who had decided to use the Spanish capital as their base between 1945 and 1953 is large: besides Negrelli, Madrid hosted the likes of Leon Degrelle, Mario Roatta, Rene Lagrou, Walter Mosig, Pierre Daye, Gastone Gambara, Johannes Bernhardt and other far-right elements who had survived the war. Some of these former fascists only stayed in Madrid briefly, but it is worth noting that the Spanish capital had become an almost obligatory destination in their life trajectories.

These journeys to and from the city of Madrid are part of a larger context. The defeat of the Axis in 1945 caused the end of fascist regimes, but that did not mean that the activists who had openly supported the fascist cause until then vanished into thin air. Despite the difficult international context, many of them managed to escape Allied prosecution and continued fighting for their political cause in the following years. In that regard, the present article begins with the premise that the survival and subsequent resumption of (neo)fascist activities was facilitated by the existence of a series of urban spaces across the world, from Cairo to Santiago de Chile, including Rome, Buenos Aires, Lisbon and, of course, Madrid. In these cities, the former fascists escaping Allied prosecution managed to build expatriate communities through regular interactions and the ensuing transfer of ideas. In turn, those communities became an integral part of a wider transnational neofascist network that allowed far-right actors to remain active in the political arena.Footnote 5

Within these larger webs of urban spaces, Madrid quickly became an important node. The Spanish capital was not an obvious point of reference for the far right after 1945. Indeed, echoes of the narrative that depicted it as ‘world capital of antifascism’ still resonated across Europe – echoes best exemplified by the growing popularity of the picture taken by the Soviet agent Mikhail Koltsov which showed a banner in the Calle Toledo with the famous slogan ‘¡No Pasarán!’ (They shall not pass!).Footnote 6 However, the Spanish capital had started to gain relevance within the far-right camp already in 1945, first as a city of refuge for quislings fleeing the Allies.Footnote 7 This trend would intensify in the following years when several neofascists decided to settle in Madrid and to launch their new political initiatives through the support structures created in the Spanish capital.

This paper examines how Madrid became an important space within the post-war neofascist universe, combining both the facets of Madrid as a city of refuge and as a transnational centre of operations. It outlines how former fascists established themselves in Madrid, including the neighbourhoods they lived in, the areas in which they worked and the places where they engaged socially – mainly in a few key districts of the city centre. The sharing of urban spaces within the Spanish capital would result in growing exchanges between neofascists, which eventually enabled entanglements and moments of cooperation at various formal or informal political levels. Consequently, the close study of Madrid illuminates the way that the neofascist network operated in the years immediately after the end of the Second World War and adds a new dimension to our understanding of the Spanish capital during the twentieth century.Footnote 8

In addition, while there has been a substantial increase in studies over the past fifteen years revolving around experts and institutions, as well as their roles in fascist or fascistised regimes, transnational processes of exchange and adaptation that developed after 1945 have been largely neglected.Footnote 9 The most notable exceptions are the works of Matteo Albanese and Andrea Mammone, which look at processes of cross-fertilisation and the circulation of extremist doctrines, strategies and personnel across state borders, as well as a commonality of behaviours between different neofascist groups across post-war Europe.Footnote 10 The present article thus takes their works as a point of departure, although it ultimately adopts a different focus. While Mammone and Albanese concentrate on analysing the Franco-Italian and the Spanish-Italian webs by studying the composition and channels of communication of the people included in them, this is a study of the interaction between the larger transnational neofascist network and the urban space of Madrid. By focusing on a single city this work will allow for a better understanding of the importance of a shared space in creating networks and exchanges.Footnote 11

As for Madrid, to this date there is no comprehensive study which looks at how the transnational neofascist network functioned within the city after 1945. This gap can partly be explained by the fact that scholars studying the Spanish capital have tended to focus on the periods of the Second Republic, the Spanish Civil War and the transition to democracy.Footnote 12 Moreover, the studies which link the importance of Franco's Spain with the evolution of the far right in the post-war period do not analyse in detail the role played by the Spanish capital. Even if these pieces of scholarship mention Madrid as a node in the escape routes, or ratlines, used by fascists fleeing Europe after the Second World War, they do not comprehensively study how such ratlines operated in the Spanish capital.Footnote 13 Furthermore, none of these academic works analyse what happened after the dissolution of those ratlines, nor what were the consequences of the political actions carried out by the former fascists remaining in the Spanish capital. Thus, one of the main contributions of this article is to show that, by the time those escape routes were no longer necessary in the late 1940s, Madrid had become an important centre of operations for the transnational neofascist network.

Because many former fascists were persecuted by the Allies, their political initiatives often remained clandestine. Therefore, relevant primary sources in which they recorded a thorough account of their political views and projects are rare. For this reason, a combination of primary sources has been used, including police reports, secret service documents, memoirs, personal diaries and legal texts. This has been particularly useful to gain insight into neofascist activities, especially in the years immediately after the end of the Second World War.

In that regard, it is worth mentioning that this article presents one notable exception: the final draft of the Pierre Daye diaries with his handwritten corrections, which can be found at the Centre for Historical Research and Documentation on War and Contemporary Society in Brussels. Pierre Daye was a Rexist journalist who had collaborated between 1940 and 1944 with the Third Reich by running different newspapers that supported National Socialist beliefs.Footnote 14 During that time, the Belgian Rexits managed to create a large web of contacts throughout Europe, something which allowed him to play a prominent role within the far-right camp. In March 1944, Daye was sent to Madrid by the far-right French journal I Am Everywhere (Je suis partout) in order to write a series of articles on the Francoist regime. Although in theory he was only supposed to stay for a short period of time, the Allied landings in Normandy changed his plans and he decided to remain there. In the end, he would live in the Spanish capital until the beginning of 1947, when he fled to Buenos Aires using the ratline he had helped to create. Because of the active role Daye played within the Madrilène expat community during his three-year stay, often helping and collaborating with other former fascists hiding there, this diary constitutes a crucial testimony to reconstruct the way the neofascist network functioned on the ground after 1944.Footnote 15

The Pierre Daye diaries are combined with reports from different Western secret services and police forces who were in charge of chasing after these political activists; the sources primarily come from the CIA archives, the Italian Central Archive and the General Archive of the Spanish Administration. Even though the documents found there do not address how the neofascists viewed Madrid, they do provide many details on when these former fascists arrived in the Spanish capital, where they settled, who they kept contact with and which activities they carried out there. This information can be valuable if adequately contextualised. For that, it is important that the researcher uses the actions and initiatives as described by the different reports to make deductions about the thoughts and impressions of these neofascists. In other words, by looking at those actions as statements, it is possible to gain some insight into their minds.

From a conceptual perspective, this paper agrees with Matteo Albanese, Andrea Mammone and Tamir Bar-On when they contend that there are important connections between fascism and the post-war far right.Footnote 16 As these authors have evidenced in their works, several fragments of interwar fascism survived the war and continued to exist after 1945, thus demonstrating that interwar fascism should not be regarded as a closed phenomenon. In the words of Andrea Mammone, ‘We cannot overlook the fact that some fascist office holders were politically active after the war, and in some European areas extreme-right parties were being organizationally built on significant pre-war foundations.’Footnote 17

However, this does not mean that the post-1945 far right is presented here as an exact copy of its counterpart during the interwar years. Between the end of the war and the mid-1950s, many former fascists initiated a process of re-thinking of the fascist ideology from their hideouts scattered throughout the world. The outcome was a hybrid creed which maintained several elements from ‘interwar fascism’ together with a series of changes.Footnote 18 Accordingly, the political actors who lie at the heart of this piece are described here as ‘neofascists’, with the prefix ‘neo’ evidencing that their way of understanding politics constituted a partial departure from the ‘classic fascism’ paradigm.Footnote 19

While this work does not offer a static definition of neofascism in the belief that if we pathologise these types of ideologies they will be harder for us to understand, it posits that the actors inside the neofascist network generally shared a series of characteristics. Among those, there was ultra-nationalism, visceral anti-communism, racism (mostly in the form of anti-Semitism), demands for a strong authoritarian state based on law and order, preference for charismatic leadership, a collective sense of crisis and national decline, a fascination with a glorious past, a rejection of the parliamentary process, a belief in European superiority, a defence of the values of tradition, a justification of violence, and a reliance on intuition, instinct and the irrational.Footnote 20 In addition to neofascism, the terms ‘far right’ and ‘extreme right’ are also used to designate the political family to which these political actors were ascribed. In any case, it should be considered that the categorisations adopted here take a certain degree of flexibility while placing the main focus on the circulation of ideas, people and actions.Footnote 21

Madrid as a Safe Haven

In the weeks after the surrender of Nazi Germany, the people who had supported its cause were in a difficult position; with the downfall of the Third Reich they were now the main targets of the Allied prosecution aimed at eliminating all remnants of fascism from the most important areas of European society. In this context, between 1945 and 1946, former fascists were persecuted all over Europe. Some were arrested and put on trial; others managed to escape and went into hiding. But staying hidden in their own countries indefinitely was still dangerous, so they seized opportunities to flee in search of safer destinations, mainly to South American countries such as Argentina, Paraguay or Brazil, and the Middle Eastern countries of Syria and Egypt.Footnote 22

At the same time, though, escaping to another continent was not an easy task, especially with most Western European territory under the control of the Allied authorities. Such journeys across the Atlantic or the Mediterranean would normally take place via Italy and the Iberian Peninsula and had to be made clandestinely. This required the crossing of several borders, several support points en route, and consequently the forging of falsified documents. In other words, fleeing Europe in the direction of the Middle East or South America was a hazardous large-scale operation which required the collaboration of many political actors in different countries across Europe.Footnote 23

Nevertheless, former fascists were not alone in their endeavours. They were able to find refuge in a number of ‘friendly’ cities used as provisional layovers. Madrid quickly became one of the most important safe urban spaces mainly because the Francoist regime was sympathetic towards them. In fact, Madrid was already hosting several prominent fascists sent by their governments during the Second World War to conduct business with the Francoist regime. Often, they were diplomats in office, like the Italian Social Republic (ISR) representative in Spain, Eugenio Morreale, the Romanian Ambassador in Madrid, Radu Ghenea, or the Ambassador of Vichy France to the Francoist regime, François Pietri. In other cases, they were journalists or writers who had been sent by their newspapers to cover the Spanish situation, like the French journalist Charles Lescat and the Belgian journalist Pierre Daye. As the Allied armies advanced towards Berlin these ‘Madrilène fascists’ became increasingly determined to help ‘their comrades’ escape because, for them, it was both a moral obligation towards their ‘brothers-in-arms’ and a way to strengthen their political situation in Europe. It was these people who would create the initial structures to help other fascists escape (ratlines), thus turning Madrid into a key node in the transnational neofascist network.Footnote 24

Ratlines were a system of escape routes for fascists fleeing allied justice put in place as the war was coming to an end. Although they were rather efficient in facilitating escape, the ratlines were largely informal, making use of an ever-changing network of people across different countries. In some instances, the escaping fascists would reach the final destination as originally intended, but in other cases they might have decided to settle in one of the intermediate points and become an active member of the ratline itself. Precisely because these networks were in constant flux, they had no clear demarcations and it is almost impossible to determine the exact numbers or how many members were part of them. However, it is still possible to generally distinguish two major escape routes: the first went from Germany to Spain, then Argentina, and the second from Germany to Rome to Genoa, then South America (Brazil, Chile or Argentina). Madrid was a crucial intermediate point within this first route and became the central node of three major ratlines within it: the degli Agostini ratline, the Bernhardt ratline and the Fuldner ratline.Footnote 25

The degli Agostini ratline was the first to open. It was headed by Arturo degli Agostini and supported by former officials of the RSI who had operated in Spain since at least the summer of 1943. Degli Agostini, who owned a very popular ice cream shop in the heart of Madrid, had already been identified in 1944 by the Italian Interior Minister as one of the most active fascists within the Italian community.Footnote 26 When the war ended, degli Agostini initiated an intense political campaign mainly aimed at reuniting and reorganising the Italian community residing in Spain.Footnote 27

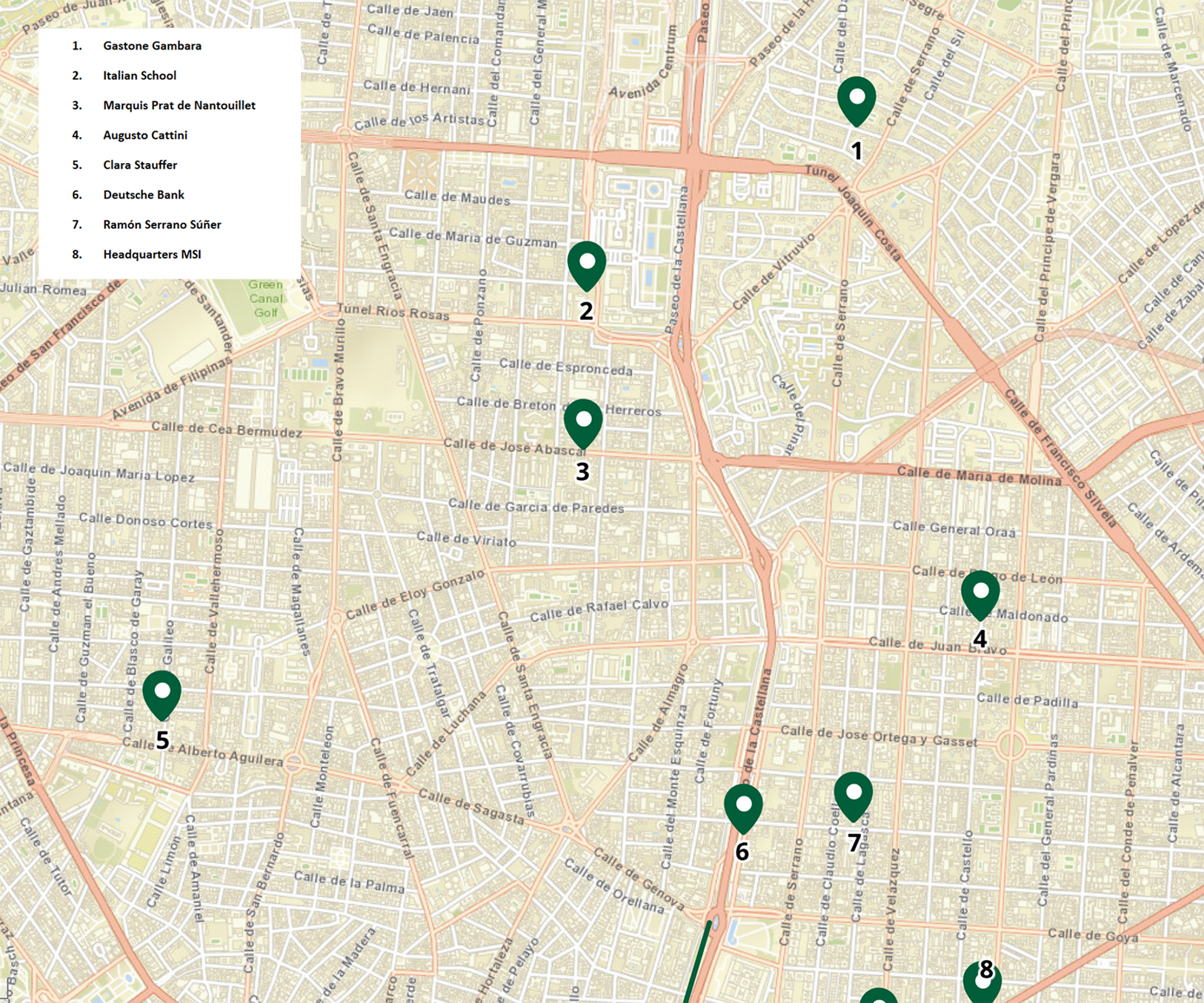

A large segment of this Italian diaspora was concentrated in the city of Madrid, especially in the Chamberí district, where the Italian school was located (see maps 1 and 2).Footnote 28 It is difficult to provide exact numbers, although the journalists Cesare Gullino and Leo Negrelli calculated that there were around 3,000 Italians living in the Spanish capital in 1957, out of a total population of roughly two million people.Footnote 29 While this number was relatively modest (especially if compared to the British, the French or the Portuguese expat communities, which had more or less twice as many), they clarified that ‘their importance is far superior than its mere numerical consistence’.Footnote 30 Indeed, Gullino and Negrelli added an extensive list of the businesses and shops owned by Italians in Madrid, mainly in the central districts of the city, between Centro, Retiro and Congreso (see map 1). In general, all these businesses orbited around the Italian Chamber of Commerce, which was located in Calle Gran Vía 27 (see maps 2 and 5).Footnote 31 As for the political orientation of the Italian colony in Madrid, and beyond the nationalistic feelings typical of communities residing abroad, it is unclear how many individuals had fascist tendencies. What is known is that degli Agostini's dynamism in this period earned him considerable prestige among the Italians of Madrid, and that he would put his political capital to use helping fellow fascists escape Allied prosecution.Footnote 32

Map 1. Large-scale map of the division of districts in Madrid in place between 1902 and 1955. Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Organizaci%C3%B3n_pol%C3%ADtico-administrativa_de_Madrid

Map 2. Large-scale map containing the location of some of the main elements of the neofascist network residing in Madrid between 1945 and 1953. Made by the author with the help of Laura González Arriaga.

Map 3. Small-scale map containing the location of some of the main elements of the neofascist network residing in Madrid between 1945 and 1953. Made by the author with the help of Laura González Arriaga.

Map 4. Small-scale map containing the location of some of the main elements of the neofascist network residing in Madrid between 1945 and 1953. Made by the author with the help of Laura González Arriaga.

Map 5. Small-scale map containing the location of some of the main elements of the neofascist network residing in Madrid between 1945 and 1953. Made by the author with the help of Laura González Arriaga.

Between the summer of 1945 and the end of 1947, the degli Agostini group set in motion a mechanism which aimed to help fascists escape Italy, give them shelter while in Spain and, in some cases, provide them with falsified documents so that they could travel to South America. Nevertheless, it was impossible for a group of civilians to create and manage such a complicated structure alone. In order to carry out their goals, they needed contacts within the Spanish government. This would prove to be relatively easy, since they had conserved the links created during the two years in which the RSI was operating in Spain. Thanks to these contacts, several Italian fascists managed to escape Allied prosecution. Among those, one name stands out: Mario Roatta, the Italian general and former head of Mussolini's secret services, who would end up settling in the central Calle Fuentes 3 (in the Centro district; see maps 2 and 5) and become director of the ‘Sociedad Anónima Comercial Hispano-Italiana (SACHI)’.Footnote 33

The second major ratline in Madrid was constructed around the prominent SS member and businessman Johannes Bernhardt. Bernhardt was a political actor who enjoyed an ideal situation in Spain which would eventually allow his ratline to gain relevance in the neofascist universe. There were several factors that allowed for Bernhardt's increasing relevance. First, Bernhardt had maintained frequent contact with the highest echelons of the Francoist regime, as well as the main representatives of the Spanish economic elites, since at least 1936, when the Berlin government entrusted him to supervise economic relations between Germany and the rebels headed by General Franco. This was done through the holding company SOFINDUS of which Bernhardt was managing director.Footnote 34 Second, Bernhardt had close contacts with the Nazi regime in Germany, sustaining regular communications with the leadership of the party.Footnote 35 Third, Bernhard managed to establish links with the Allied authorities when the Second World War ended by becoming an informant within operation SAFEHAVEN, an Anglo-American program created in December 1944 to locate German assets in the neutral powers and steer them into ‘safe havens’, generally British or American humanitarian organisations.Footnote 36 Finally, and even though he ceased to be the general director of SOFINDUS (now dissolved), the Allies granted him freedom of movement within Spain, and also control over a series of companies that SOFINDUS had created and which were not part of the SAFEHAVEN project, and whose resources amounted to eighty million pesetas.Footnote 37 Thus, Bernhardt enjoyed a unique position in the summer of 1945 from his office located in Calle Gran Vía (see maps 2 and 6): he had important contacts within the Nazi party in Germany, enjoyed the protection of the highest echelons of the Francoist regime, worked together with the Allied authorities and had substantial economic resources at his disposal.

Map 6. Small-scale map containing the location of some of the main elements of the neofascist network residing in Madrid between 1945 and 1953. Made by the author with the help of Laura González Arriaga.

Well aware of his prominent position, Bernhardt decided to use it to mobilise the community of Germans residing in Spain to develop a structure that could help former Nazi members prosecuted by the Allies come to Madrid and, from there, make all the necessary arrangements to secure their safety. In this regard, it is necessary to clarify that the German expat community in Madrid had similar characteristics to the Italian one. According to the German Ambassador to Madrid in 1958, Karl-Hemrich Knappstein, there were around 3,000 nationals living in the Spanish capital. Many of those were well situated financially and owned different businesses around the city. From a geographical perspective, those businesses were located in the central districts (Congreso, Centro and la Latina), and their activities mainly revolved around the triangle formed by the headquarters of the Deutsche Bank (located in the Calle Castellana), the Chamber of Commerce (located in Calle Velázquez) and Horcher, the main German restaurant, located in Calle Alfonso XII (see maps 2 and 4). From a political perspective, the German ambassador noted that there were only a minority of Germans who openly supported the Nazi cause; it is thus reasonable to assume that this group was rather small in number, although important in political and economic terms.Footnote 38

In April 1945, Bernhardt called a meeting at his house on Avenida del Valle 3 to discuss the best way to organise the aid to be distributed to the Germans fleeing Allied prosecution. The meeting was attended by thirty of the most prominent members of the German community residing in Madrid, and resulted in the official creation of Bernhardt's ratline.Footnote 39 Bernhardt would be at the top of this structure, and he would be aided by two people: Clara Stauffer, a German woman, naturalised Spanish, who had worked for the Seccion Femenina of the Falange since the Spanish Civil War (see maps 2 and 3), and General Wilhelm von Faupel, who had worked as military adviser in Argentina in the 1920s and had spent time in Spain, assisting Franco during the Civil War.Footnote 40

The third major ratline in Madrid was established at the beginning of 1945, although its origins and composition were to be slightly different from the others. If the first two groups had originated from Italian and German fascists who already resided in Madrid during the Second World War, this third ratline came from the outside. The first steps were taken on 10 March 1945 when Carlos Fuldner, an Argentine of German descent who had spent much of his youth in Germany, flew into Madrid from Berlin. Fuldner, who had joined the Schutzstaffel (SS) and the Nazi Party before the Second World War, was determined to create an organisation that would run war criminals between Europe and Argentina via Spain. Fuldner also received support from Argentina's president, Juan Domingo Perón, who had just assembled a group of European fugitives, many of them war criminals, with the aim of bringing several German technicians to work for the government.Footnote 41

This ratline would receive a further boost with the addition of four prominent fascists arriving from different parts of Europe: Pierre Daye and René Lagrou from Belgium, Radu Ghenea from Romania and Charles Lescat from France. René Lagrou, renowned for being the leader of the Flemish SS between 1940 and 1941 and organising the action against the Jewish community in Antwerp, had been captured by the Allies in France but had managed to escape to Spain in 1945. It was then when he was recruited by Daye for the Fuldner ratline.Footnote 42 Radu Ghenea, the Romanian Ambassador in Spain during the Second World War, had decided to stay in Madrid in order to assist the Romanian refugees who were arriving in Spain through his personal connections to Franco.Footnote 43 Charles Lescat, lastly, was a famous writer and supporter of Charles Maurras, director of Je Suis Partout. Lescat would flee to Madrid right before the definitive collapse of the Vichy regime and immediately become an active member of the ratline (thanks to his friendship with Daye).Footnote 44 From Spain, these four political activists collaborated to help other fascists fleeing Allied persecution. Eventually, after years of frantic activities from the Spanish capital, all the members of this ratline ended up in Buenos Aires between the end of 1946 and the beginning of 1947. However, this did not mean the end of their involvement in the escape routes; on the contrary, they continued working within the Fuldner ratline from the Argentine capital (mainly issuing landing permits to war criminals), thus creating a strong connection between Madrid and Buenos Aires.Footnote 45

Beyond the names, all these ratlines become even more relevant if it is considered that the people who formed them, and those who escaped from Allied prosecution with their help, were all to meet in the city of Madrid with many other right-wing extremists, thus creating the impression of some sort of unity. People like Johannes Bernhardt, René Lagrou, Mario Roatta, Pierre Daye and Clara Stauffel found themselves sharing the same urban spaces in Madrid's centre between 1944 and 1947 (see map 2). Although each of these political actors had their own group of regular acquaintances, mainly based on the language they spoke, it was not unusual that, given the relatively small size of the city centre, and the fact that most of their homes and offices were located there, they would constantly run into each other, thus creating frequent moments of interaction. As Pierre Daye explained in his memoirs, ‘There were [in Madrid] still some French “collaborators” like the young and ardent Count de Robien, or other foreigners like the former Minister Plenipotentiary of Romania, Radu Ghenea, a member of the Iron Guard, all of them fanatics of their ideals. […] And we sometimes met each other, Germans, or Austrians, or Italians or Croatians, stoic under the avalanches of fate’.Footnote 46

Although these casual encounters often started in the street, it was not uncommon that they ended up in one of the many restaurants and taverns that populated the central arteries of the Spanish capital. After all, Madrid was a lively city and most of these emigres were looking to socialise. As illustrated in/by the second and seventh map in the annexes, they would go out in the evenings for a stroll through the main arteries of the centre, the axis formed by Castellana, Gran Vía and Alcalá, meet different people along the way, and sometimes agree on going somewhere to have dinner. In the words of Pierre Daye, ‘[In Madrid], there are many illustrious men, outcasts, fugitives, from all countries. I know many of them. I talk with them. They come from Berlin, London, Algiers, Paris, Rome and Lisbon […] hospitable friends, with whom I dine on certain evenings’.Footnote 47 In the case of the exiled groups who had more financial constraints, like Daye's, they normally had their meals in the small, cheap taverns in Calle Lope de Vega, which was in the heart of the city (see maps 2 and 7). They ate, watched flamenco performances and exchanged news from newspapers clandestinely obtained. For those emigres who were better off, they would prefer to dine in more expensive restaurants like Horcher, or ‘Hostería del Laurel’, also in the city centre.Footnote 48

Map 7. Small-scale map containing the location of some of the main elements of the neofascist network residing in Madrid between 1945 and 1953. Made by the author with the help of Laura González Arriaga.

A similar experience was conveyed by the neofascist journalist Leo Negrelli, who lived in Calle O'Donnel 35, in the Retiro district (see maps 1 and 4). He spoke of the regular meetings of ‘foreign elements’ residing in Madrid. ‘Here we gather every week; I ask and obtain information about different countries from the comrades’. In exchange, Negrelli provided information about the events taking place in Italy.

In sum, the memoirs, the letters and the recreation of their physical space on the maps suggests that there were both formal and informal exchanges between these actors. On the one hand, and even though the three ratlines made use of their own independent networks, they all shared the common goal of helping fascists escape the Allied prosecution, which meant that they assisted each other and made use of the same contacts within the Francoist regime. On the other hand, because these actors shared the same spaces of socialisation within the centre of Madrid, some of the exchanges took place through more casual events like dinners and drinks. In turn, this helped in creating personal bonds which fostered a sense of unity and camaraderie.Footnote 49

New Arrivals: The Consolidation of Madrid as a Neofascist Hub

The situation of many of these actors changed towards the end of 1946 due to the evolution of the international context which allowed the Allies to relax their efforts to prosecute war criminals. Partly because of the growing tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, the governments in London, Paris and Washington began to realise that the reconstruction of Europe had to take precedence. Thus, the issue of war criminals became of secondary importance, if not a nuisance; Western societies needed to start looking ahead and stop dwelling on the past. This did not imply that war criminals were left undisturbed. The Allied authorities continued to follow their steps and, in some cases, push for their capture. However, this was done with less urgency than between 1945 and 1946.Footnote 50

As a result of the new atmosphere, former fascists in hiding slowly began to feel more secure. In a way, they had the sense that, as relations between Moscow and Washington deteriorated, their time was not over yet, and they could still be relevant political actors in the post-war world. These impressions were best exemplified once again by Pierre Daye's memoirs:

Among these French, Hungarians, Bulgarians, Italians, Romanians, Poles, Croats, Dutch, Austrians, Belgians (and even a few Germans who were hiding to avoid being handed over to the Inter-Allied Control Commission and forcibly repatriated) [political refugees in Madrid], morale was nevertheless better than one could have imagined. We felt that nothing was over, that unforeseen events would arise which would put everything back in play, that our cause was just and that revenge would come one day. In the meantime, we had resist, resist, resist, resist.Footnote 51

In this context, Madrid would continue to consolidate its position as one of the most important hubs for former fascists, together with Rome, Lisbon, Buenos Aires, Cairo and Santiago de Chile. The strengthening of Madrid's position within the far-right universe was accelerated by the fact that, in this period, some of the most prominent former fascists freely decided to settle in the Spanish capital. A clear trend was emerging in the city: Madrid was not just a safe haven but a place in which these right-wing extremists could become politically active again. This dynamic can be illustrated by analysing two specific cases: Gastone Gambara and Otto Skorzeny.

Gastone Gambara was an Italian general who had actively participated in the Spanish Civil War by heading a division within the Corpo di Troppe Volontarie (CTV) that fought alongside General Franco. When the Spanish Civil War ended, Gambara was appointed Italian Ambassador in Madrid. He was also a brigadier in the Second World War, participating in the campaigns in North Africa and the Balkans. After the armistice, Gambara remained loyal to Mussolini, a choice that, once the war was over, landed him in prison where he would spend only a few months thanks to the amnesty issued in 1946 by the leader of the Italian Communist Party and Minister of Justice at the time, Palmiro Togliatti. Following his release, Gambara took advantage of the friendly relationship he maintained with many members of the Francoist regime (including Franco himself) to settle comfortably in the luxurious residential area of El Viso (Calle Tambre 3; see maps 2 and 3).Footnote 52 From this privileged position, Gambara became not only a key element inside the neofascist network but also a fundamental liaison between the Italian government and the Francoist regime, especially concerning economic questions. At the same time, Gambara also had regular contacts with the Italians living in Argentina, especially when they wanted to conduct business in Spain or Italy, thus contributing to consolidating the links between Madrid and Buenos Aires.Footnote 53

The second relevant arrival was that of Otto Skorzeny, an Austrian born SS-Obersturmbannführer in the Waffen-SS, who had become a symbol for many fascists throughout Europe due to his participation in different military operations during the Second World War, including the liberation of Mussolini from his prison of the Gran Sasso in 1943.Footnote 54 Arrested by the Allies in 1945, Skorzeny was sent to an American prison camp in Germany. He was released by the Americans in 1948 and turned over to the German authorities, having been absolved of any war crimes or guilt. From April to July 1948 he was held in a German prison camp, but after three months he escaped and spent a few months in hiding between France and Germany. In September 1950, he arrived in Madrid where he would settle definitively. Even though he arrived in Spain as a fugitive of German justice, this situation would not last long. In fact, he would be de-nazified in absentia by the German courts in 1952 after ruling that he was not guilty of any war crimes or criminal acts.Footnote 55

In his memoirs, Skorzeny explains how he managed to settle in Spain, a ‘chivalrous country’ which allowed him to continue with his career as an engineer. Crucially, the main reason he gives for going to the Spanish capital was that he had ‘loyal friends’ there, people with contacts and money who were willing to assist him upon his arrival.Footnote 56 Thanks to them, Skorzeny would eventually be able to gather enough money to open a small office-studio at the heart of Madrid (in Calle Gran Vía) from where he could conduct international trade and financial operations (see maps 2 and 6).Footnote 57 Although he used the alias of Rolf Steinbauer and was supposed to act discretely, in practice his arrival in Madrid was a well-known affair; on 9 February 1951, the US Chief of the Madrid Permit Office, Hudson Smith, wrote a report explaining that Skorzeny ‘is ostentatiously here [in Madrid] undercover, but his presence is fairly common knowledge and he has even given interviews to the press’.Footnote 58 Furthermore, the CIA explained that Skorzeny's engineering company in Madrid was nothing but a cover, and that he had already resumed his political activities with the help of Leon Degrelle.

The arrival of figures like Gambara and Skorzeny in Madrid gave a further boost to the far-right community residing in the Spanish capital. To begin with, and as already mentioned, it was important for the city to host people who had become symbols for the fascist cause at a global level due to their ‘heroic’ acts during both the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War. In addition, both Gambara and Skorzeny had a vast web of international contacts which they were also bringing into the neofascist hub Madrid was becoming. This list of contacts included, of course, the Spanish elements gathered around Johannes Bernhardt and Leon Degrelle, but also some of the most prominent figures in and outside of Europe, like Werner Naumann and Otto Remer in Germany, or Johann von Leers in Argentina. Furthermore, Skorzeny and Gambara were also able to use their connections with the most important businessmen in Spain, Italy, Germany, Egypt, Syria and Argentina. Finally, Skorzeny managed to establish close contacts with the Allies, through the Allied Commission for German Affairs in Spain, thus becoming an official CIA informant concerning possible communist activities in the world.Footnote 59

Ultimately, the fact that Gambara and Skorzeny de motu propio relocated to the Spanish capital reveals that, by the end of 1946, more and more neofascists understood that, beyond issues of safety, Madrid had become an ideal city for them to carry out their activities. The active tolerance of the Francoist authorities and the possibilities to use them as contacts to conduct lucrative business deals were all factors that facilitated their settlement in the capital. After all, these right-wing extremists also needed economic resources for their everyday life. Furthermore, from Madrid it was possible to participate in the increasingly vast neofascist network that now spread from Western Europe to South America and the Middle East. Such a network would be used by right-wing extremists to become politically active again and lay down the foundations for the construction of a new Europe based on an updated version of the ideals of interwar fascism. As Leon Degrelle wrote from his Madrilène hideout:

Despite the misfortunes of the moment, I remain optimistic. Difficult battles are the most beautiful. […] More and more the world is going mad. It will explode. Our time will return. […] The war has created a real ‘European’ spirit. People are waving to each other from all sides. All this will come together. […] Within ten years everything will be changed. Then I'll be just at the age of maturity and action.Footnote 60

In order to carry out these plans, the right-wing extremists established in Madrid would take two types of initiatives, all revolving around this idea of a ‘third force Europe’: the creation of political structures and the development of paramilitary groups.

Madrid as the Epicentre of Neofascist Activities: Political Activism

It is in this context that two major transnational neofascist groups decided to open their offices in Madrid, an initiative which would have crucial ramifications for the Spanish capital in its path towards becoming an important neofascist hub: the Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI) and the European Social Movement (EMS).Footnote 61 The opening of the Madrilène branch of the MSI coincided with the good results obtained by the neofascist party in the 1948 Italian general elections that had strengthened it at an international level, and which placed the MSI at the ‘vanguard of neo-fascism’.Footnote 62 At the same time, the international strengthening of the MSI's ideological influence was accompanied by the determination of the party to establish political relations with the Francoist regime, now seen as one of the most important allies, and also as a political point of reference. Well aware that in the new post-war international context it was necessary to operate on an increasingly international basis, the MSI became determined to set in motion a series of mechanisms that allowed them to be the dominant force of the extreme right in Italy, while maintaining contact with other similar governments, organisations and political parties abroad. Thus, establishing official relations with the Francoist regime quickly became one of the main priorities.

This strategy was aided by the fact that the MSI leaders did not have to start from scratch, as they were able to use the web already consolidated by degli Agostini and his comrades in 1945 through their ratline. In order to achieve this, the MSI leaders hurriedly opened an office in Madrid and appointed degli Agostini as the new director, who also became the head of the first MSI delegation abroad. Beyond the relevance of degli Agostini, the fact that the MSI opened its first international branch in Madrid was extremely important for the evolution of the city as a neofascist hub (see the location of MSI headquarters in maps 2 and 3). On the one hand, it provided for the incorporation of one of the most important parties on the far right into the urban space of Madrid.Footnote 63 On the other hand, the presence of the MSI in the Spanish capital entailed the integration of all the MSI contacts in Italy and also abroad; the node of the neofascist network established in Madrid was becoming substantially larger, more global and more official.Footnote 64

Similarly, the MSI decision confirmed the transformation of the fascist ideology so that it could be adapted to new post-war contexts. To be sure, many former fascists in Europe, convinced that their vision had been discredited by the Second World War events, acknowledged that their political camp had to adjust itself to the new socio-political environment. The dramatic loss of the historical climate which produced fascism, together with its marginalisation within political cultures and the subsequent loss of its mass base, forced neofascists all over Europe to develop two basic strategies for keeping the dream of national rebirth alive, which Roger Griffin has identified as ‘internationalization’ and ‘metapoliticization’.Footnote 65

It is in this context that Oswald Mosley's visit to Madrid and his meeting with Leo Negrelli ought to be placed. Although the meeting did not produce practical results, it clarifies how the network functioned in the urban space of Madrid, and how new strategies were being re-thought there. Mosley and Negrelli's ideas had a pronounced tendency towards internationalisation, while advocating for the reinvention of Europe as a third force between East and West as the high watermark of racial civilisation. Their ambitious programme for the rehabilitation of a reunited, rearmed, neofascist European super-state also entailed their involvement at the very heart of the post-war far-right international movement, consisting of disparate remnants of continental fascism over which they sought to exert their ideological dominance. European unity, Negrelli argued, was already in motion and fascists ‘need to accelerate its evolution, contribute to its organization’. In this regard, Negrelli posited that Mosley's journey – which would take him to many different European countries, starting in Spain – constituted a perfect occasion to begin since it could be used for the ‘polarization of the propaganda for the European unity around him’.Footnote 66

This position was shared by Mosley himself. According to the British intelligence, Mosley had been trying to create a loyal web of contacts in Spain since the end of the Second World War, convinced that the ‘possibilities of development in Spain were of the greatest importance’.Footnote 67 Such was the relevance of Spain for Mosley that his right-hand man, Alexander Raven Thomson, had travelled to Madrid twice in a very short period of time: once in mid-March 1949, and once in June 1949. By then, the British secret services had no doubts: ‘Mosley is doing all he can to develop his foreign contacts and form a European Union Movement’.

Upon his arrival in Madrid, Raven Thomson confirmed the Francoist regime's potential as a political ally and decided to give further impetus to Mosley's contacts there. In order to do so, he appointed Robert Delfs, a Belgian residing in Calle Alcalá 26, as the new representative of Mosley in Spain (see maps 2 and 7). Robert Delfs had been a member of the Socialistische Vlaamsche Arbeiderspartij (NSVAP) in Belgium since 1942, a position from which he developed contacts with some prominent neofascists like Oswald Pirow in South Africa and Adrien Arcand in Canada.Footnote 68 Upon his arrival in the Spanish capital, Delfs developed new links and collaborated on a regular basis with a circle of individuals, some of whom were already part of the wider Madrilène node of the neofascist network; to the usual suspects like Leo Negrelli, Raimundo Fernández Cuesta or Johannes Bernhardt, Delfs added new elements like Marjorie Munden, an Englishwoman who belonged to Falange's Sección Femenina and was in close contact with Pilar Primo de Rivera, and Alejandro Botzaris, a professor and writer of anti-Soviet material (see maps 2 and 4). The Mosley group in Spain also established contacts with other Falangists like Victor de la Serna and Manuel Hedilla.Footnote 69

Once the web of contacts was consolidated, they started preparing the trip which would eventually be sponsored by Franco's brother-in-law and Nazi enthusiast, Ramón Serrano Súñer, ‘whom we had not known before but who welcomed us with warm hospitality.’Footnote 70 Although the sojourn in Madrid did not have any direct political implications, it contributed to strengthening the network thanks to the meetings with Negrelli and Bernhardt. It also had great symbolic relevance for Mosley, who became ecstatic when he visited José Antonio Primo de Rivera's tomb in El Escorial:

However, all mundane things were forgotten when, on the way, we arrived at the Escurial [sic.] which he had caused to be opened around midnight. We stood alone in awe of that sombre splendour. The purpose of the visit was to stand for a few moments by the tomb of Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of the Falange. I had seen him only once, when in the thirties he had visited me in London at our headquarters in Chelsea. He had made a deep impression on me, and his assassination seemed to me always one of the saddest of the individual tragedies of Europe. I was deeply moved as we stood beside the sepulchre of this young and glittering presence I remembered so vividly, and was reminded of the initial line of Macaulay's memorable tribute to Byron: ‘When the grave closed over the thirty-seventh year of so much sorrow, so much glory’.Footnote 71

From Madrid, Mosley headed to Rome in March 1950 to attend a conference sponsored by the MSI. In this regard, it should be considered that, parallel to Mosley and Negrelli's initiative, further impetus for the re-establishment of an internationalist neofascist front was also coming from the Italian party. Having established contact with former functionaries of the Nazi party in West Germany and with neofascist groups in Austria, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, Spain, South America and the Near East, the MSI had decided to organise a European study centre and began publishing its own international periodical, Europa Unita (United Europe). The last step in their strategy was the organisation of two congresses (one in Rome in 1950 and one in Malmö in 1951) aimed at attaining ‘the unification of the older and younger generations of European fascists on an ideological and organisational basis’.Footnote 72

After long deliberations and several heated debates, the delegates present in Malmö officially created a pan-European umbrella organisation named the European Social Movement (ESM) in May 1951 with the main aim of creating a vast European imperium around the idea of the defence of Western culture against communism through transnational cooperation. The ESM also issued public appeals for centralised corporate control of the economy alongside a call for social justice, which would bring about the spiritual regeneration of man, society and the state. Finally, the unanimously accepted committee claimed that national sovereignty could no longer be a useful concept.Footnote 73

The ripples of the decisions made in Malmö quickly arrived in Madrid. There, the growing neofascist community decided to seize the momentum and organise an international meeting in September 1951 on the occasion of the anniversary of the liberation of Toledo's Alcazar during the Spanish Civil War.Footnote 74 The meeting was attended by representatives of several national affiliates of the ESM, who decided to constitute themselves as a special committee and to hold a series of conferences with leaders of other organisations such as the Dutch World Community Europa of Paul Van Tienen, the Croatian emigre movement of Ante Pavelic, which was headed in Spain by their clergymen, Dr Fray Brenko Maric, the Romanian branch of the Iron Guard in Spain under Vasil Iassinky, and a delegation of former members of the Condor Legion.Footnote 75 Mosley, Skorzeny and Degrelle were also invited to the meeting, although only Skorzeny and Degrelle managed to attend.Footnote 76

The outcome of these encounters reflects the importance that Madrid was acquiring within the neofascist universe. Indeed, the newly founded special committee decided to establish an ESM liaison office in Madrid which ‘would coordinate the various groups in Spain and cultivate contacts with South America, the Middle East and Asia’.Footnote 77 The person appointed to run this liaison office in Madrid was the Swiss neofascist Jean-Maurice Bauverd, something that confirmed the transnational character of the network. Bauverd had made his appearance in the far-right camp at the end of the war. After being in prison for one year having been accused of carrying out Nazi activities, he fled to Cairo where he established contacts with former SS officers thanks to the mediation, according to US intelligence, of the MSI and Oswald Mosley.Footnote 78 Persecuted by the Swiss authorities, Bauverd then decided to settle in Madrid, something which was facilitated by Otto Skorzeny. Skorzeny not only helped Bauverd obtain the legal documents to cross the border but also managed to get him a job with the company Agarthis Interntional Features Service, located in the centre of Madrid in Calle Infantas 21 (see maps 2 and 6). Bauverd would combine this task with the new job for the ESM, thus becoming a crucial actor within the network.Footnote 79

The opening of the Madrilène branches of the MSI and the ESM (both in the city centre) constituted a key step in the transformation of Madrid into an important transnational hub for the extreme right. By the end of the 1940s, the role of the city within the far-right universe had evolved into something different. Madrid had now become an urban space of paramount importance for the most prominent neofascists who not only decided to hide there but also to use it as a central point for their political initiatives. The city was a place where ideas, strategies and actions concerning the future of ‘Third Force’ Europe could be discussed and actively promoted. This was mainly for two reasons. First, right-wing extremists operating in Madrid enjoyed the support of some of the highest echelons within the Francoist regime, a major political point of reference and an example of how the far right worked in practice. Second, Madrid appeared as the perfect geographical space to bring right-wing extremists from the south and the north of Europe together and to build bridges between the nodes of the network established in the Middle East and those located in South America.

Madrid as the Epicentre of Neofascist Activities: From Political Activism to Military Organisation

The creation of branches of the MSI and the ESM were not the only activities of the neofascist community in Madrid. The Spanish capital was also identified as a prime location to set in motion a series of military initiatives aimed at creating a barrier against the expansion of communism in Europe.Footnote 80 This should not be too surprising considering that the end of the 1940s coincided with increasing tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union. In this context, Skorzeny launched his plan to set up an army of German military men in Spain in the event of war with Russia. The purpose would be to be prepared for the defence of the West in case of Soviet attack, based on the premise that ‘today the defense of the greater part of Western Europe is practically inoperable'.Footnote 81 The Soviet invasion of Europe, Skorzeny argued, ‘would mean the inevitable collapse of European culture and, above all, the total destruction of European intelligence. Although Europe might again be liberated by an invasion, there would later be no men capable of bringing about reconstruction in the spirit of the West.’Footnote 82 Accordingly, Skorzeny made two proposals to minimise the Soviet threat: the formation of a basic German cadre in Spain, made up of army, air and naval personnel, which could at the same time be used as an organisation to absorb the mass of active German forces, and the formation of European cadres which could be used in case of war to spring into action throughout European territory.Footnote 83

Although Skorzeny's proposal might appear unrealistic, in reality it enjoyed considerable support among right-wing extremists at the time and was even seriously studied by certain elements within the US intelligence. First, it had the backing of certain elements within the Spanish government and the Spanish military, with General Agustin Muñoz Grandes being the key figure; after all, Muñoz Grandes had relevant contacts with the German military since he was the general in charge of the Blue Division (the unit of volunteers from Francoist Spain within the German army in the Second World War). Second, it had the support of some of the most prominent Nazi generals still residing in Europe, namely Heinz Guderian, Hans Speidl and Walter Wenk. Skorzeny also made contact in Germany with various nationalist groups and war veterans associations such as the Union of Sudeten Germans, the Union of Exiles and the Brotherhood of Germans Union. All of them, Skorzeny explained, ‘fervently defended my own point of view and agreed with my comments, namely that something must be done to save the Germans’.Footnote 84

Finally, Skorzeny had managed to contact the most important Nazi elements present in Spain and who would constitute the bulk of this army. In this regard, it should be acknowledged that Skorzeny ended up replacing Bernhardt as the main point of reference for German Nazis in Madrid since the latter was increasingly interested in protecting his numerous economic activities. Nevertheless, this does not mean that Bernhardt became irrelevant to the network; on the contrary, he continued to play a crucial role since part of the money generated by his companies was still being used to finance the structures to secure the wellbeing of the right-wing extremists who needed it, and also to move forward some of the initiatives. However, it seems that, with the arrival of Skorzeny in Madrid, Bernhardt took a step back, at least concerning public relations for the group. In a way, it was as if he had allowed the Austrian SS to become the visible face of the German-speaking part of the network. This was done in a rather natural way and without apparent tensions.Footnote 85

Despite the original support for Skorzeny's initiative, the plan was eventually abandoned due to internal differences between Speidl and Skorzeny.Footnote 86 This notwithstanding, Skorzeny's project to create a secret army to fight communism remains very important. First, it is still worth noting that Skorzeny wanted to establish the headquarters of the organisation in Madrid. This decision was based on the strategic value of Spain: ‘If in the course of the next few years a new world conflict should break out, it is probable that fixed battlefronts could not be established in Europe. In the course of the coming years bridgeheads such as Spain, or perhaps the entire Iberian Peninsula, could at least be established. The remainder of Europe would fall under the Communist yoke.’Footnote 87 For most of the neofascists who were still active at the time, the capital of Franco's Spain was the ideal place to set in motion their political projects.Footnote 88

Second, the project showed that, for the coming years, Skorzeny would be one of the key figures within the neofascist transnational network; in the words of CIA officials, ‘Skorzeny is the most prominent figure in the international neo-Nazi-Fascist movement today, and perhaps is even a dominant force in it.’Footnote 89 In fact, once the idea for a shadow army in Madrid failed, he devoted his attention to other activities which included the sale of weapons to countries in the Middle East (mainly Egypt, Morocco and Syria) and also to the training of military personnel around the world. The latter activity involved constant trips to Cairo, Buenos Aires, Damascus and Rome, thus strengthening the links between Madrid and the wider network of urban spaces used by the far right.Footnote 90 Furthermore, if one considers that Skorzeny and his ‘adventures’ featured so prominently in the Western media, it is possible to understand how the Spanish capital further enhanced its relevance within the neofascist network, to the extent of becoming an almost obligatory point of pilgrimage for any person interested in the neofascist ideology in the following decades.Footnote 91

Conclusions

In the years immediately after the end of the Second World War, Madrid became a hub of neofascist activism. Between 1945 and 1953, scores of former fascists flocked to the Spanish capital; initially, they were just looking for a haven in their escape from Allied justice. As time went by and Allied pressure relaxed, they began to realise that Madrid could be used as a centre of operations, an arena in which it was possible to reunite and reflect upon potential changes to their ideology and upon new tactics in light of the new international situation. The existence of Madrid, and cities like Madrid such as Buenos Aires, Rome or Cairo, thus first provided a safe space and then later headquarters from which to plan future actions. Both are essential aspects to understand the emergence of neofascism after 1945.

The transformation of the Spanish capital into a neofascist hub, though, did not happen overnight. In 1939 Madrid was still seen by many in Europe as a symbol for the antifascist struggle. However, this image started to change after 1945 with the creation of the first ratlines to help prominent fascists escape from Allied prosecution. In that context, Madrid would become a nodal point in the journeys of these people to South America and the Middle East. Specifically, the Spanish capital hosted at least three major ratlines aimed at granting safe passage, and even though most of these people did not stay in Madrid for long, the relatively small space they shared facilitated frequent moments of interaction, which in turn laid the ground for the creation of an active transnational community.

But it was not just a matter of being safe. The capital of the Francoist regime attracted former fascists for a variety of additional reasons, both pragmatic and ideological. In pragmatic terms, it appeared as one of the most suitable spaces to settle after 1945. The contacts with the highest echelons of the Francoist regime facilitated the obtaining of residence permits, and also gave the possibility to create new businesses from which to launch trade and financial operations. To be sure, Madrid was a good place for former fascists to make a living. In ideological terms, the Francoist regime had a deeper ideological appeal, and offered an alternative to the liberal world order with its authoritarian nationalism. Madrid also appeared as an ideal location from a geostrategic position. It was a place where neofascists from all over the world could exchange ideas and put them into practice under the protection of the Francoist regime, as well as a meeting point between different groups of right-wing extremists from Northern Europe, Southern Europe, South America and the Middle East.

The outcome of all these interactions within Madrid was the creation of a highly fluid exile community, composed of far-right activists with various backgrounds, motivations and strategies. As Pierre Daye described: ‘The small group of political refugees in Madrid was constantly forming, deforming, reforming itself.’Footnote 92 However, and despite the changes and eventual disagreements, the members of the community were generally keen on exchanging knowledge and cooperating, thus becoming an important node of the wider transnational neofascist network. In the streets around the centre of Madrid, right-wing extremists mingled, liaised and engaged with each other. They discussed the past, the present and the future of Europe, re-assessing their experiences of the interwar period. In doing so, they recognised the extent to which their vision had been discredited by the events of the Second World War, as well as the dramatic loss of the historical climate which had produced fascism and its marginalisation within their political cultures alongside the loss of its mass base. However, not everything was lost. As Leon Degrelle wrote:

There will be, as you will see, a wonderful job to be done. I feel this with every fibre of my being. And these years of war will have allowed us to ‘live Europe’ in an admirable way. Now we can reflect upon it, now we can make it clear. In two, three, five years, the decisive hour will come. Now we have the experience. And after this recapitulative retreat, we will return to action when all the others are tired and worn out.Footnote 93

The ensuing remapping of the neofascist political geography, and their own position in the global anti-communist struggle, made these activists reconceptualise their movement as part of the global revolt against communism, the European integration process, as well as parliamentary democracy, something which would be crucial for neofascism in the 1960s and 1970s.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Pedro Félix González Moya, the best tourist guide in Madrid. The many tours and walks you organised in Madrid were a constant source of knowledge and inspiration to me while writing this article.