Introduction

The aging population within long-term care is growing and a sociological lens of social citizenship offers a unique perspective to understanding residents’ potential roles in these congregate social environments. Long-term care settings such as nursing homes, assisted and retirement living, offer support for the increasing numbers of older adults living with a variety of diagnoses and health conditions. The discourse around the lives of people living in these homes has been dominated by a focus on an irreversible decline associated with aging and disability, and assumptions around loss of agency instead of a rights-based focus (Kontos, Miller, & Kontos, Reference Kontos, Miller and Kontos2017). As residents adjust to personal physical and cognitive changes, losses of privacy and former relationships, they also deal with discrimination and a loss of rights (Kusmaul, Bern-Klug, & Bonifas, Reference Kusmaul, Bern-Klug and Bonifas2017). Residents are often excluded from equal involvement in critical social practices and decision making in these settings (Birt, Poland, Csipke, & Charlesworth, Reference Birt, Poland, Csipke and Charlesworth2017).

Bartlett and O’Connor (Reference Bartlett and O’Connor2010) offer a conceptual framework of social citizenship that highlights the importance of recognizing residents as active agents with rights, history, and competencies. Attachment to others is an important component of quality of life (Kurisu et al., Reference Kurisu, Terada, Oshima, Horiuchi, Imai and Yabe2016), yet is not sufficient in the context of residents as active social citizens (Bartlett & O’Connor, Reference Bartlett and O’Connor2010). Bartlett and O’Connor (Reference Bartlett and O’Connor2010) describe the importance of offering opportunities for growth, social positions, purpose, participation, community, and the importance of freedom from discrimination. They identified two key concepts that support social citizenship that are relevant in these settings: (a) moving from a sense of attachment and relationship with others, to solidarity—uniting with others to make a difference; and (b) moving from doing things to stay occupied, to doing things with meaning and purpose (Bartlett & O’Connor, Reference Bartlett and O’Connor2010). The idea of solidarity has been identified as a necessary component of healthy communities that requires united action to help society progress (Thake, Reference Thake2008), yet programs supporting solidarity are rare in long-term care. While events reflected on typical social calendars keep some residents occupied, they often do not offer opportunities to engage in purposeful or meaningful activity (Theurer et al., Reference Theurer, Mortenson, Stone, Suto, Timonen and Rozanova2015).

Literature underscores the strategic significance of citizenship as a concept within long-term care (Lister, Reference Lister2003) and residents being able to exert control over their decisions and preserve their autonomy (Brownie, Horstmanshof, & Garbutt, Reference Brownie, Horstmanshof and Garbutt2014). However, the combination of the challenging health conditions (Milne, Reference Milne2010), along with the consequences of being allocated to a new lower status socially, makes this difficult for residents to realize. Citizenship includes the ability to be connected and socially productive as an adult (Brannelly, Reference Brannelly2011), but opportunities to do this in long-term care homes are rare (Theurer et al., Reference Theurer, Mortenson, Stone, Suto, Timonen and Rozanova2015).

Mental health among persons in long-term care settings is of considerable concern. Reported prevalence rates of depression range from 11 to 85.5 per cent (Elias, Reference Elias2018). A diagnosis of depression is made by a geriatric psychiatrist, and examples of depressive symptoms include negative statements, persistent anger, repetitive anxious complaints, or sad/pained/worried facial expressions (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2010). Depression is linked with many negative health outcomes, including decline in self-sufficiency and cognitive impairment (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2010) and increased mortality (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Vogelzangs, Twisk, Kleiboer, Li and Penninx2013). Yet only a small proportion of residents receive an evaluation (8.4%) or psychological therapy (2.6%) by a licenced mental health professional. Similarly, the prevalence of loneliness in care homes is also high, affecting well over half of people living in these settings (Nyqvist, Cattan, Conradsson, Näsman, & Gustafsson, Reference Nyqvist, Cattan, Conradsson, Näsman and Gustafsson2017). For example, in Europe the reported rates range from 37 to 56 per cent (Victor, Reference Victor2012), and in some studies these rates range from 56 to 95.5 per cent (Elias, Reference Elias2018). Loneliness has a negative impact on health and is linked to depression, heart disease, dementia, decreased physical function, and increased mortality (Donovan & Blazer, Reference Donovan and Blazer2020).

Cruwys et al. (Reference Cruwys, Haslam, Dingle, Jetten, Hornsey and Chong2014) argue that loneliness and depression can result from lack of purpose. A study among community-dwelling older people found that feelings of uselessness were associated with increased mortality (Curzio, Bernacca, Bianchi, & Rossi, Reference Curzio, Bernacca, Bianchi and Rossi2017). Conversely, a literature review found a sense of purpose is associated with improved well-being and noted that fostering a sense of purpose was a particularly important but often ignored aim within aged care contexts (Irving, Davis, & Collier, Reference Irving, Davis and Collier2017). A deeply entrenched tradition of providing social programs in long-term care settings that are based on games, socials, and bus trips designed and facilitated by staff continues (Theurer et al., Reference Theurer, Mortenson, Stone, Suto, Timonen and Rozanova2015). A recognition of the potential benefits of relationships with co-residents and contributions by residents is often lacking (Slettebø et al., Reference Slettebø, Sæteren, Caspari, Lohne, Rehnsfeldt and Heggestad2016).

Peer mentoring as an approach to improving mental health may be useful in these settings. While visiting family members help protect some residents from loneliness, other available agents such as fellow care home residents are often overlooked (de Vries, Reference de Vries2021). Peer mentoring has been described as empathetic peer support offered on a one-to-one basis that includes a form of guidance or advice (Dennis, Reference Dennis2003). Peer mentoring skills have been defined as the ability to problem solve, offer a new perspective, and suggest coping skills (Joo, Hwang, Gallo, & Roter, Reference Joo, Hwang, Gallo and Roter2018). The Mental Health Commission of Canada (2012) identified peers helping one another as an important potential approach in the provision of mental health services. The health benefits of helping others are significant (Vaillant, Reference Vaillant and Post2007). In a sample of older Canadians living in the community, Theurer and Wister (Reference Theurer and Wister2010) found that sense of belonging was associated with helping others. Peer mentoring, particularly using a group or team approach, may have the potential to augment limited mental health services in these settings Stone & Bryant, Reference Stone and Bryant2012) and honour the rights of people living in long-term care. A feasibility study examining a team approach to mentoring has demonstrated reductions in loneliness and depression among the mentors Theurer et al., Reference Theurer, Stone, Suto, Timonen, Brown and Mortenson2020a) and among those being visited Theurer et al., Reference Theurer, Stone, Suto, Timonen, Brown and Mortenson2020b).

The terms peer mentoring and peer support are often used interchangeably—both refer to developing empathy and support amongst peers, but our approach differs from other peer support studies. In this article, we use peer support as an umbrella term and use peer mentoring to describe one form that peer support can take. Peer support is: (a) based on interpersonal interactions grounded in a common experience, (b) based on reciprocity, (c) involves a positive social structure, and (d) includes mutual sharing based on personal experience (Keyes et al., Reference Keyes, Clarke, Wilkinson, Alexjuk, Wilcockson and Robinson2014). Pragmatically, peer mentoring in this study centered on social and emotional support and shared learning offered in long-term care homes by resident mentors to resident mentees. The peer mentoring described is this study is a form of volunteering. While volunteering has been defined in different ways and can consist of different activities, it is defined here as a form of unpaid labour that is formal (Overgaard, Reference Overgaard2019).

To our knowledge, no research has explored team-based peer mentoring to address the emotional needs of people living in long-term care. The use of peer support and peer mentoring has mostly been focused on people living in the community with severe mental illness (Joo, Hwang, Abu, & Gallo, Reference Joo, Hwang, Abu and Gallo2016) and other illnesses such as dementia (Keyes et al., Reference Keyes, Clarke, Wilkinson, Alexjuk, Wilcockson and Robinson2014) or physical health challenges such as low back pain (Dennis, Reference Dennis2003) or chronic kidney disease (Taylor, Gutteridge, & Willis, Reference Taylor, Gutteridge and Willis2016). Drawing on concepts of social citizenship, we examined a peer mentoring group approach called the Java Mentorship program. This mentoring program was developed by the first author (K.A.T.) based on an informal pilot that took place in 2011–2012 to explore the mentoring concept among residents in a continuing care community and two long-term care homes. During this pilot, K.A.T. developed a training manual based on the challenges encountered by the facilitators and the mentors.

In the mentorship program, volunteers (e.g., volunteers or family from outside the residential setting, i.e., community mentors) and residents (i.e., resident mentors) meet as a team, receive training, and provide visits in pairs to residents who are lonely or socially isolated (i.e., mentees). This program is inclusive of residents with dementia and other cognitive impairments and resident mentors with dementia are paired up with community mentors who provide support as needed. The community mentors assist resident mentors with the training exercises. One example is the training topic of “How to help people grieving.” In this module, a discussion is held first about honouring personal grief and ways for mentors to take care of grieving in their own lives. Then mentors are invited to use a flip chart to draw up two columns: what helps people grieving and what does not. The community mentors pair up with resident mentors and help explain any parts of the module and exercises that are unclear.

The coronavirus disease, COVID-19, pandemic represents increased loneliness and loss for residents living in care homes. As visitors have been banned and group activities eliminated to limit the spread of the virus, the adverse effects of prolonged social isolation have grown (Trabucchi, Reference Trabucchi2020). While creative measures have been taken to combat loneliness with the use of digital tablets to connect residents with family (Pitkälä, Reference Pitkälä2020), resident-to-resident relationships are equally important. Indeed, relationships that residents develop with one another are a strong predictor of loneliness (Drageset, Reference Drageset, Kirkevold and Espehaug2011). Thus, resident mentors can play an important role in ameliorating loneliness due to the impact of COVID-19. A review examining purposeful activity interventions found that those that offered functional helping roles to participants had a positive impact on the well-being and quality of life among older adults (Owen, Berry, & Brown, Reference Owen, Berry and Brown2021).

In our study, we explored the resident mentors’ responses as part of a larger mixed-methods study to explore the feasibility of conducting a clinical trial (Theurer et al., Reference Theurer, Stone, Suto, Timonen, Brown and Mortenson2020c). The purpose of this article is to describe the experiences of being a mentor from the perspective of residents living in long-term care.

Methods

The analysis presented in this article draws on individual interviews conducted with resident mentors to explore their perspectives on peer mentoring as part of a larger study. The article is based on interviews with resident mentors using open-ended questions about the experience of being a mentor (n = 48). We report the findings using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007). Ethics approval was obtained from the University of British Columbia with additional permission at the research sites through the partner organization, the Schlegel-UW Research Institute for Aging. Thirteen for-profit, long-term care homes located across Ontario, Canada, were invited to participate in the study.

Eligibility and Recruitment

Resident mentors who were interested in helping others, able to speak and understand English, and able to comprehend simple instructions were eligible to participate in the interviews. Exclusion criteria included residents on temporary care respite stays and those who were acutely ill as assessed and determined by nursing staff. Together, with the research assistants, staff determined who were willing and able to participate in the interviews and who could provide their own written consent. Study advertisements were posted, and staff made personal invitations to residents. All the initial interviews were conducted no later than at three months after the start of the program, as we anticipated a high attrition rate in these care homes.

Cognitive Performance Scale levels (Paquay et al., Reference Paquay, Lepeleire, Schoenmakers, Ylieff, Fontaine and Buntinx2007) were assessed using Resident Assessment Instrument–Minimum Data Set scores (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2010) from resident charts using the Cognitive Performance Scale level 2 (mild impairment) to level 6 (very severe impairment) as cut-off scores. Assent and dissent were respected and were based on how residents who lacked consent capacity expressed or indicated their preferences, verbally, behaviourally, or emotionally (Black, Rabins, Sugerman, & Karlawish, Reference Black, Rabins, Sugerman and Karlawish2010). Institutionally recognized surrogate decision makers (e.g., the resident’s spouse, adult son, adult daughter, brother, sister, adult grandchild, close friend or guardian) provided written consent for the resident mentors deemed unable to provide informed consent independently. Verbal assent was obtained from residents whose consent had been obtained from a surrogate decision maker.

The majority of the interviews were conducted by the research assistants, and three were conducted by a member of the research team (K.A.T.). Participants were given time to consider and provide answers, and no replacement questions were required at any of the sites. Among the 48 participating resident mentors, a sub-sample of 8 were invited to complete an additional interview. The purpose of the second round of interviews was to explore the responses given in the first interviews in more detail, ask additional information on key questions, and provide a better understanding of the resident mentors’ experiences (these practices are sometimes referred to as member checking, used to enhance internal validity of findings in qualitative research). We set out to obtain one mentor per home based on availability, accessibility, and ability to participate in a second longer interview. The results presented are based on the combined initial 48 interviews and the second round of 8 interviews.

The Program Processes and Components

The program consists of two components: weekly team meetings and dyadic visits with mentees. Resident mentors, volunteer mentors, and staff facilitators attended the team meetings. The mentorship team meetings follow a structured format that includes ongoing education provided by the program facilitators who use the training manual provided. The meetings also include a discussion of resident mentees who would potentially benefit from visits, as well as support and recognition activities for the mentors. The education modules outlined in the training manual include a broad range of topics such as how to engage passive mentees who did not speak much or did not want to leave their room, dementia training for the visits with resident mentees living with dementia, and how to support someone who was grieving. Each module has multiple sub-topics, for example, dementia training included active listening skills, how to use questions, and how to use sensory materials. In the current study, the speed at which the education modules were completed varied from site to site, as some resident mentors required more time to complete them. In addition, some modules were repeated as resident mentors required a refresher. There were specific activities built into the team meetings to strengthen their identity, such as receiving name badges that identified them as a mentor, receiving certificates, and participating in ceremonies.

Team meetings typically lasted an hour and the visits took place right after, although some resident mentors described visiting with the resident mentees at other times as well, for example, during coffee times. During the visits, mentors offered support and encouraged mentees to participate in programs that would help enhance social connections with their peers.

Data Collection

We held monthly project meetings with the research assistants and staff throughout the data collection process to provide support and answer questions. The interview guide included questions that encouraged the resident mentors to describe their experience. Question examples included: What has it been like for you being a participant in the mentorship program? What do you think about the education portions of the team meetings? What has it been like for you to go on the visits? Have you had any challenges during the visits? Do you have any suggestions about how we could improve this program? Interview questions were given verbally in a neutral space (e.g., a quiet area in a resident lounge), were intended as a probe to generate conversation, and were intentionally open-ended. Staff introduced the research assistants or the research team member to the resident mentors and then left to allow for privacy.

Data Analysis

All of the interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim and ranged in duration from 45 to 90 minutes with all of the sub-sample interviews lasting over an hour. Data from the two data sources of mentor interviews were combined. Data analysis proceeded inductively, starting with each mentor’s experiences, and through an iterative process moved towards gaining an understanding of central themes in the form of important commonalities and patterns that emerged across the interviews. Using a framework established by Ritchie and Spencer (Reference Ritchie, Spencer, Bryman and Burgess1994), we conducted a thematic analysis. Stages of analysis included becoming familiar with the interview transcript data, identifying a thematic framework (beginning development of categories and coding), and making comparisons within and between themes, identifying or selecting quotes and re-arranging them, and, finally, interpreting the overall data. Four of the authors reviewed a sample of transcripts independently and then employed a consensus-based process to identify codes and final themes.

We used three main trustworthiness strategies to ensure transferability, credibility, dependability, and confirmability in this study. The first approach, triangulation, involved the use of multiple analysts to review the findings and compare and check data collection and interpretation. Having four team members interpret the findings provided a check on selective perceptions and helped clarify the analyses. The second approach, reflexivity, helped us examine how bias, values, beliefs, and experiences may have influenced the research. The first author kept a reflexive diary, documented insights, assumptions, and prior beliefs using interview notes that influenced the way data were read, analysed, and written up (Hesse-Biber & Leavy, Reference Hesse-Biber, Leavy, Hesse-Biber and Leavy2006). Interview notes were written immediately after the interviews. One assumption held was that people living in long-term care are capable of growth, and that they strengthen their own well-being when they support and encourage others. The program materials developed by the first author reflected this assumption. To address this assumption, as a third approach, we actively looked for negative cases, probing for alternative explanations rather than only accepting those that were congruent with the authors’ assumptions.

Results

Of the 13 homes invited to participate in the current study, 10 agreed to participate. Of the three homes that declined, two had had recent staff turnover and one did not have adequate staffing. Of the 10 participating, 5 were long-term care homes and 5 were continuums of care that included long-term care, assisted living, and retirement services. Two homes conducted the program differently than outlined, therefore only eight were included in the final analyses.

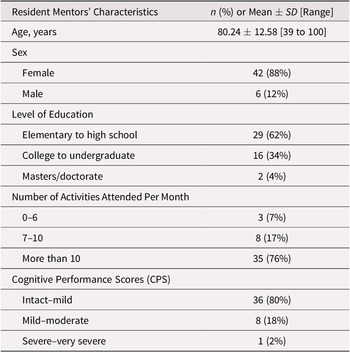

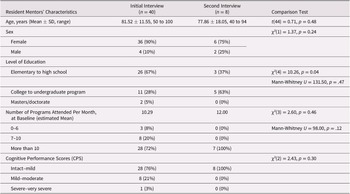

All resident mentors invited to participate in the interviews accepted the invitation (n = 48) and lived in one of the long-term care homes or in the long-term care side of the continuing care community. Only a few of the mentors interviewed were male, and most had elementary to high school education and either no dementia or mild dementia (Table 1). The majority were socially engaged in their communities and attended over 10 activity events on a monthly basis. Mentors interviewed had a higher level of education (the majority had college) compared with mentors who were not interviewed. We examined the mentors who were interviewed initially versus mentors who had a second interview (Table 2) with respect to gender, age, education, social participation, and cognitive functioning and found no statistically significant differences between two sub-groups in any characteristics except for level of education (p = 0.04).

Table 1. Resident mentors’ characteristics (n = 48)

Table 2. Comparison between sub-groups of resident mentors: Initial interview (n = 40) versus second interview (n = 8)

We identified three overarching, inter-related themes from our analysis of the resident mentors’ interviews. The following themes were drawn from a combination of the initial interviews and the eight follow-up interviews: Helping others, helping ourselves describes the benefits that residents experienced in adopting the new role of a mentor; Building a bigger social world reveals how the mentors developed connections and fostered new relationships with those they visited; and Facing challenges, learning together illustrates how mentors learned as a team to deal with challenges encountered. Pseudonyms have been used to preserve anonymity of the participants.

Central Themes

Helping others, helping ourselves. Mentors reported a variety of personal benefits from their volunteer service. Cheryl, an 81-year-old resident mentor living with mild dementia, for example, noted positive changes in herself: It helped me with my confidence. It made me feel like I was needed. It makes you feel good to help! This feeling of being needed was in marked contrast to the experience that Liza, a much younger 40-year-old resident mentor with cerebral palsy, had with other programs:

The rest [other programs]—I’m not taking part in them, I’m listening to somebody else [the staff] do it [run the programs]. So, I appreciate that, um, and plus I feel I’m adding something with this program, I’m helping them. It makes me feel like I’m a different person.

Some mentors described the benefits of being a mentor as reciprocal. Cheryl stated, Well, and what feels so good about it … I feel like we’re adding to their [other residents’] experience and it makes it better for them. And by doing that it makes it better for me. Mentors indicated that, through tending to their peers, they felt they were receiving help themselves. For example, Melody, an 81-year-old resident mentor, pointed out, It’s important [helping them] and helping people that are lonely—including me.

Mentors also expressed a sense of enjoyment and gratitude that came from participation in the program. Hillary, a 60-year-old resident mentor living with multiple sclerosis, spoke of her participation in the following way: I was very flattered that they asked me. I’m just … thankful that I was asked to do it. Liza, who had lived at the care home for over 10 years, also expressed her enjoyment: He [the mentee] makes me happy each time I do it—’cause I am his mentor. The role appeared to enhance the resident mentors’ sense of appreciation through both the connections built within the team and people visited. Ella, a 77-year-old mentor with early-stage dementia, stated, It’s the best thing to do. It’s very good—I love it. I like the [team] and I can hardly wait to come every week. Thus, mentors received personal benefits and enjoyed their role.

Building a bigger social world. Mentors talked about new connections and friendships developed with those they visited. Karen, a 91-year-old resident mentor living with early-stage dementia, noted her excitement about the developing friendship with someone she did not previously know and stated, It’s been a thrill … when you first go in, they’re, we’re strangers … [and now], they’re like our old friends. She continued, I think it also benefits them in that it opens up their world a little bit. Um, it’s not just their world, it’s ours. They share with us their family and their kids and it just makes it a bigger world. Mentors observed positive responses of the mentees during the visits. These responses from mentees had an impact on them. Cheryl stated, … they’ve been happy to have us there. Uh, [they] seem to be happy to share their room and happy to know that we’re coming in to visit them. Mentors expressed enjoyment in these connections and being able to help people they visited. For example, Hillary commented, I enjoy sort of pulling them out of themselves. You know they’re sometimes mentally in a small space. And when you, somebody goes in to visit, it pulls them out of that little small space.

The visits sometimes helped establish relationships outside of the program. Liza pointed out, I really like it. It’s good, in fact he [a mentee] eats at the next table from us. So, every time we go by him, we’ll say hi. In this way, resident mentors described how their social world became larger and that the connections with people they visited also extended beyond the formal visits. This occurred at times with fellow residents who were not their mentees. Karen, for example, hesitantly described the regret she felt concerning a tablemate with dementia whom she had sat beside at mealtimes for several years—that in the past she rarely made an effort to speak to her. She elaborated in her interview:

I’ve been at lonely stages in my life. And I could feel for them. I practise at my table, this one resident … I practise on her too. Because, just to have her respond, she’s there, she’s not going to keep her eyes shut [and not speak with us]. And … so I use it [mentoring skills learned] separately.

Since becoming a mentor, Karen found it fulfilling to practise her newly learned communication skills with her long-time tablemate.

Facing challenges, learning together. This theme illustrated how mentors learned together how to deal with difficulties encountered. Mentors described team meetings as a combination of camaraderie, a space for learning that benefited them personally and on visits, and a place to address problems that arose. For example, Hillary stated, It really helped because instead of just coming here blindly, and saying ‘Ok, just go and be with them’….they give you lots of tips and tricks for building rapport. Hillary also noted the strong bonds that formed between mentors and her enjoyment of the learning processes that happened during the meetings:

It’s being like family. And we have a time of learning something about ourselves. Oh, I do [enjoy the meetings]! I think they’re a good draw that they put us into focus before we go to visit the people. And it’s nice, it’s always nice to learn something new.

The initiation ceremony of new incoming mentors and some of the specific educational techniques, such as team role-playing, were described by Hillary as positive and encouraging. Although mentors experienced difficulties, they felt they could safely share these challenges during the team meetings. Mary, who was 85 and had early stage dementia, stated, You discuss everything and, and maybe a problem hit [you encounter a challenge], that you know, you lost contact [connection with the mentee] … everything was discussed [with the team]. Thus, the mentors’ reports indicate that teamwork was a positive approach in terms of learning mentoring techniques, receiving support, and in finding solutions to problems.

Mentors sometimes encountered challenges in connecting with people they visited. For example, occasionally, mentees were not interested in a visit or were asleep. William, 81 years of age and one of the male mentors living with mild-moderate dementia, commented, One of the challenges is always being engaged in conversation and if the mentee doesn’t want you to come in and stay with them. Being prevented from carrying out a visit by staff when a mentee was asleep resulted in a strong emotional reaction in Liza:

Sometimes when I go there the nurses tell me he is asleep. But I don’t know. I know he needs his rest, but I want them to realize that I have to take care of him when it’s his day, right. So, he stays in his room and he doesn’t do nothing about me. He doesn’t know nothing about me.

In addition, mentors shared similar concerns that sometimes mentees were passive during the visits, either watching TV or not actively participating. Although the mentors expressed some frustration around these challenges, they also talked about finding solutions to these challenges during the team meetings. For example, mentors gave one another suggestions and advice for alternative approaches during the program meetings (e.g., changing the scheduled time to when the mentee’s favorite TV show was not on).

Mentors also encountered a few challenges regarding scheduling, visiting spaces, and health issues. Karen found the evening time for team meetings selected by her home difficult as she was often tired after dinner. However, she continued to participate and explained that the evening time was chosen as volunteer mentors from outside the home were not able to come during the day for team meetings. She stated, I just … I just wish we had a different time schedule, but it’s impossible. Right now, anyway. The small spaces in private rooms were challenging for some to negotiate during the visits. Karen described her own health as a barrier to visits as she suffered from rheumatic fever, saying that she was not always able to participate in the team meetings on Saturdays. However, Karen stated that she compensated for this by conducting additional visits during the week when she felt stronger.

Discussion

The aim of our study was to explore peer mentoring as a form of active social citizenship among people living in long-term care and describe its impact from the resident mentors’ perspectives. The social citizenship lens offered a useful theoretical foundation to examine the role of people living in long-term care settings, and our findings highlight the potential benefits of offering residents structured mentoring opportunities to help one another. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore a team-based peer mentoring approach in a long-term care home that includes education, and where two mentors pair up to visit each resident mentee.

The first theme elucidated resident mentors’ experiences and benefits received through adopting the new social role of a mentor. A social role has been defined as a comprehensive pattern of behaviours and attitudes that affect how a person behaves and is treated by others (Turner, Reference Turner1990). The overall impact of the role as a contributing social citizen appeared to be positive and affected the resident mentors on a personal level. Research suggests that purposeful social interaction in groups brings meaning to social life (Knight, Haslam, & Haslam, Reference Knight, Haslam and Haslam2010). It is possible that the adoption of a role that is focused on helping others within a group setting may be particularly important to residents, as it offers them a new identity. The beneficial effects of giving have been described by others examining the ability of residents to contribute (Yeung, Kwok, & Chung, Reference Yeung, Kwok and Chung2012) and find meaningful social roles (Skrajner et al., Reference Skrajner, Haberman, Camp, Tusick, Frentiu and Gorzelle2014). There were challenges encountered during the visits; however, sharing the challenges at team meetings and finding solutions during the team meetings were helpful to the mentors. Prior studies indicate that having a purposeful role and helping others are influential in how well individuals adjust to living in long-term care (Brownie et al., Reference Brownie, Horstmanshof and Garbutt2014), and thus the impact of this role is worth exploring in future research.

Despite the challenges encountered, the second theme revealed how mentors used their role to connect with and support their peers in new ways. Although it has been suggested that staff as experts often assume that residents are incapable of providing care and that this habitual practice silences residents (Timonen & O’Dwyer, Reference Timonen and O’Dwyer2009), in contrast, our findings reveal that mentors offered empathy and emotional support to their peers and shared their wisdom and experience, guidance, and learning opportunities. Mentors described the importance of these shared experiences and how being a mentor brought meaning to their lives, as has been identified by others (Greenaway, Cruwys, Haslam, & Jetten, Reference Greenaway, Cruwys, Haslam and Jetten2015). Thus, for staff, witnessing the resident mentors in action, particularly persons with dementia, has the potential to influence how they (as well as family and the community) view them, thereby potentially combating the stigma associated with being a recipient of care (Bartlett & O’Connor, Reference Bartlett and O’Connor2007). In our study, persons with dementia were able to participate as mentors as they were supported by another resident or a volunteer. This is an important finding. Residents as active contributors, caring and nurturing their peers, reflect a new role and may help reduce associated ageist stigma in these settings.

The third theme illustrated how mentors learned together and how the team worked through challenges encountered as they sought to build trusting relationships with the mentees. The value of providing learning opportunities for growth and connectedness for people living in long-term care has been identified (Wilby, DuMond Stryker, Hyde, & Ranson, Reference Wilby, DuMond Stryker, Hyde and Ranson2016). Providing this opportunity through this mentorship program may be particularly valuable, as two types of learning occurred—during meetings and during visits. Mentors practised what they learned during team meetings and then had additional opportunities to learn through teaching during the visits. This provides evidence of the potential benefit of offering authentic and practical opportunities for residents to identify and live their desired social identities (Haslam et al., Reference Haslam, Haslam, Cruwys, Jetten, Dingle, Greenaway, Buckingham and Best2017), such as becoming a mentor and offering support to others. Indeed, becoming actively engaged within a community can impact life transitions of residents when a loss of identity is experienced, such as moving into a care home (Knight & Sayegh, Reference Knight and Sayegh2011). Providing a structured format for residents to engage in learning and helping others may be a way to meet a significant unmet need among people living in these settings.

There are two key concepts within the conceptual framework on social citizenship described earlier that are useful in discussing the above results: (a) moving from a sense of attachment and relationship with others, to solidarity—uniting with others to make a difference; and (b) moving from doing things to stay occupied, to doing things with meaning and purpose (Bartlett & O’Connor, Reference Bartlett and O’Connor2010). The first concept centers around solidarity, which has been identified as a necessary component of healthy communities that requires united action to help society progress (Thake, Reference Thake2008). Despite being recognized as an important way to improve well-being, residents are less likely to be offered opportunities to unite and participate in civic engagement (Leedahl, Esllon, & Gallopyn, Reference Leedahl, Esllon and Gallopyn2017), which has been defined as “activities of personal and public concern that are both individually life-enriching and socially beneficial to the community” (Cullinane, Reference Cullinane2006, p. 66).

The second concept, doing things merely to stay occupied versus doing things with meaning and purpose (Bartlett & O’Connor, Reference Bartlett and O’Connor2010), appeared to play an important role in what motivated the mentors. Mentors described their gratitude for being needed and having a sense of pride in their role. Supporting meaning and purpose has been identified as an important aspect of everyday life (Drageset, Haugan, & Tranvåg, Reference Drageset, Haugan and Tranvåg2017). Yet many activities in long-term care focus on receiving rather than giving. In addition, typical social calendars do not offer opportunities to engage in purposeful activity. Giving or volunteering has been associated with mental health benefits such as higher levels of mental well-being, particularly among adults above the age of 70 years (Tabassum, Mohan, & Smith, Reference Tabassum, Mohan and Smith2016). Consequently, the purposeful helping behaviour exhibited by the mentors may have provided a sense of meaning and contributed to mentors’ sense of well-being.

With the vaccine rollout currently under way in long-term care, resident mentors might be in an ideal position to care for one another. Given the reduced numbers of visitors, the mentorship program gives residents a structured approach to helping each other. The program can be adapted in a variety of ways so that it adheres to safety protocols during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. When groups are possible, the mentorship teams can meet in smaller numbers with residents only, using safe, social distancing practices. Volunteers and family members can participate in the team meetings remotely. Both resident and community mentors can conduct remote visits via telephone or video calling apps. When visiting guidelines allow, mentors can visit residents while staying in doorways or in larger social spaces in the home.

There are several study limitations to consider. It has been noted in the literature that it is important to assess the adequacy of the data with regard to the specific features intrinsic to a study (Vasileiou, Barnett, Thorpe, & Young, Reference Vasileiou, Barnett, Thorpe and Young2018). As this was part of a larger exploratory study examining a new intervention, we conducted the interviews to begin the process of understanding the experience of mentoring from the residents’ perspectives. As the larger study involved multiple components and data collection points, we were mindful of the need to limit respondent burden. We therefore confined the qualitative interviews for some residents to a shorter time frame and to a smaller number of questions. Thus, we were not able to reach thematic saturation. The study sites were scattered across a large geographical region and data were collected over the winter months when travel was difficult. While these interviews are insufficient to draw definitive conclusions, they do provide indicators for further research. Having staff identify participants is another limitation. For example, it would have been helpful to interview more residents who were male and/or who had dementia in order to gain greater insight into their perspectives. There was a potential social desirability bias among the participants; however, much effort went into reassuring mentors that they were free to express all opinions, positive and negative, without any repercussions. Lastly, the interviews only included residents who stayed on as mentors rather than residents who withdrew, which is a sampling limitation.

This study lays the ground for future research in this area. Future research could include a social network analysis and include interviews within and across sub-groups among mentors (e.g., different cultural groups, dementia/non-dementia, women/men), which may help us understand what is unique to or transferable across groups of residents. In addition, future ethnographic studies could help capture the emotional connections that are made as well as identify possible differences between what mentors say they do and what they do. It is noteworthy that people interviewed had higher levels of education than people who were not, and future research could explore the impact of the potentially different mentoring styles between these two groups and strive to include participants who dropped out, in order to generate a better understanding about those for whom the program might not work.

Despite the study limitations, findings indicate that it is possible for residents to engage as a team of social citizens in solidarity to provide support to lonely or socially isolated peers. This includes residents living with dementia, which lends support to previous research that found that residents with cognitive impairment are capable of supporting their peers (Theurer et al., Reference Theurer, Wister, Sixsmith, Chaudhury and Lovegreen2014). The current study expands on that concept of peer support with an innovative structure that enables residents to focus on actively engaging in peer mentoring by reaching out to residents who do not typically attend programs. Although further research is required, peer mentoring may be an approach that can help reduce the substantial medical and human costs associated with loss of purpose, loneliness, and depression within long-term care settings. Enhancing the social roles of residents as citizens has considerable potential to mitigate the ageist social discourses surrounding people living in these settings. Importantly, it can provide residents with opportunities to use their skills and have a life with value, purpose, and meaning.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Ben Mortenson reports grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research [201512MSH], and his work is supported by a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Dr. Kristine Theurer reports grants from Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada [767-2014-2411] during the study. A special thank you to Susan Brown, Amy Matharu, Kaylen Pfisterer, Josie d’Avernas, and Dr. Michael Sharratt from the Schlegel–UW Research Institute for Aging, and Melanie James, residents, staff, and volunteers at Schlegel Villages.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Kristine Theurer developed the peer mentoring program prior to this study and receives remuneration for associated workshops and program materials. This conflict of interest was declared with the Behavioural Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia.