Introduction

In response to the increase in potential care needs due to population ageing (Colombo et al., Reference Colombo, Llena-Nozal, Mercier and Tjadens2011), the role of informal care-givers in maintaining the wellbeing, quality of life and health of their dependent spouses, relatives and friends is increasingly emphasised (Verbeek-Oudijk et al., Reference Verbeek-Oudijk, Woittiez, Eggink and Putman2014; Broese van Groenou and de Boer, Reference Broese van Groenou and de Boer2016). The highest proportion of informal care-givers is found among those in mid- and later life (Hank and Stuck, Reference Hank and Stuck2008; Josten and de Boer, Reference Josten and de Boer2015), and many of them are also engaged in paid work (de Boer and Keuzenkamp, Reference de Boer and Keuzenkamp2009). Changes in retirement systems in the form of ending of early retirement schemes and increasing retirement ages (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2015) imply that current working care-givers must continue to combine work and care-giving until much higher ages than their earlier counterparts. However, our understanding of how older workers experience care-giving is limited. In this study, we therefore address the following question:

• To what extent do older workers experience care-giving next to their paid jobs as gratifying, burdensome and stressful, and how are these care-giving experiences related to their work situation?

Research on how individuals experience their informal care-giving is dominated by studies focusing on burden, stress and strain (e.g. Kim et al., Reference Kim, Loscalzo, Wellisch and Spillers2006; Tolkacheva et al., Reference Tolkacheva, Broese van Groenou, de Boer and van Tilburg2011; Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Pruchno, Wilson-Genderson, Murphy and Rose2012; Braithwaite, Reference Braithwaite2016; Mello et al., Reference Mello, Macq, van Durme, Ces, Spruytte, van Audenhove and Declercq2017). Some scholars have pointed at the dual nature of care-giving experiences, meaning that care-giving may not only be appraised as potentially burdensome or stressful (Kramer, Reference Kramer1997b), but it may also ‘evoke some response of pleasure, affirmation, or joy’ (Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, Kleban, Moss, Rovine and Glicksman1989: 62) such as feelings of gratification. Earlier studies have simultaneously considered these different types of care-giving experiences in the case of specific illnesses such as cancer (e.g. Nijboer et al., Reference Nijboer, Triemstra, Tempelaar, Sanderman and van den Bos1999), stroke (e.g. Kruithof et al., Reference Kruithof, Post and Visser-Meily2015) or dementia (e.g. Labra et al., Reference Labra, Millan-Calenti, Bujan, Nunez-Naveira, Jensen, Peersen, Mojs, Samborski and Maseda2015). Only a handful of studies have examined this dual nature of care-giving experiences in large and diverse samples of care-givers (Raschick and Ingersoll-Dayton, Reference Raschick and Ingersoll-Dayton2004; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Fee and Wu2012; Broese van Groenou et al., Reference Broese van Groenou, de Boer and Iedema2013; Pristavec, Reference Pristavec2019). These studies have shown that examining so-called ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ care-giving experiences separately is of importance, because they appear to capture different dimensions of care-giving experiences (Broese van Groenou et al., Reference Broese van Groenou, de Boer and Iedema2013).

Earlier studies on predictors of care-giving experiences have predominantly paid attention to characteristics of the care-giving and the care-giver (e.g. Pinquart and Sörensen, Reference Pinquart and Sörensen2003; Broese van Groenou et al., Reference Broese van Groenou, de Boer and Iedema2013). Although most of these studies recognise the importance of work as a potential precursor of care-giving experiences, it often serves as a control variable measured either using a dichotomous indicator for employment status (e.g. Pristavec, 2018) or in terms of the number of working hours (e.g. Lin et al., Reference Lin, Fee and Wu2012). Treating work as a single item in this way can hide important variations in care-givers’ work situations (Barnett, Reference Barnett1998). Research on work outcomes of care-givers (e.g. Pavalko and Henderson, Reference Pavalko and Henderson2006; Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Pruchno, Wilson-Genderson, Murphy and Rose2012; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Ingersoll-Dayton and Kwak2013; Plaisier et al., Reference Plaisier, Broese van Groenou and Keuzenkamp2015) has shown that multiple characteristics of the work situation, particularly different work arrangements, are linked to care-givers’ work behaviours (e.g. reduced work hours, absenteeism, performance) and work evaluations (e.g. work stress, perceived ability to balance work and care). In this study, we follow the suggestion put forward by Longacre et al. (Reference Longacre, Valdmanis, Handorf and Fang2017) to examine the link between care-giving experiences and various characteristics of the work situation in more detail. This approach may provide a better understanding of which aspects of the work situation are helpful to workers with care-giving responsibilities, and as such relate to lower levels of care-giving burden and stress.

This study aims to contribute to the existing literature on care-giving experiences in three ways. First, we study the effect of a broad set of work-related factors on experiences in care-giving next to more established predictors such as measures of the care-giving situation and socio-demographic characteristics (for a review, see Carretero et al., Reference Carretero, Garces, Rodenas and Sanjose2009). More specifically, we examine the impact of both work characteristics (i.e. working hours, occupational status) and perceived access to a set of human resources (HR) practices (i.e. flexplace, flextime, phased retirement, medical examinations) on how the care-giving is experienced by the care-giver. Second, instead of focusing on working care-givers of all ages, we specifically focus on older workers who provide informal care. It is highly relevant to study this group, given that many older workers are in a phase of life in which care demands of family members or friends are present at the same time as they are being confronted with a higher retirement age. Third, we aim to improve our understanding of the dual nature of care-giving experiences, by looking at how the work situation contributes to care-giving burden and stress – but also taking into account positive aspects of care-giving as shown in previous research in an explorative way. We thus examine simultaneously the extent to which care-giving is experienced as being gratifying, burdensome and stressful. Where prior research has examined such experiences in small-scale samples of limited scope, we study them in a large and diverse sample of Dutch individuals who carry out various care-giving tasks for family members and friends.

The Netherlands, where this study is situated, represents an interesting case for studying how older workers experience care-giving next to their paid job. Recent policies stimulated communities and families to contribute to a greater extent to the care of people with moderate needs, thereby limiting the institutionalisation of dependent people (Verbeek-Oudijk et al., Reference Verbeek-Oudijk, Woittiez, Eggink and Putman2014). Besides that, early exit routes into retirement were blocked and the state pension age for cohorts born after 1950 is being increased from 65 to 67 years and will thereafter be linked to the life expectancy (van Solinge and Henkens, Reference van Solinge and Henkens2017). These policy changes are also reflected in the Dutch labour market participation figures. Whereas in 2003 the net labour market participation in the age group 60–65 years was 22 per cent, this has increased to 58 per cent in 2018 (Statistics Netherlands, 2019). Today's older workers thus have to work until much older ages than their earlier counterparts. Many of them worry about their ability to do so (van Solinge and Henkens, Reference van Solinge and Henkens2017).

Theoretical background

Care-giving experiences are the subjective response to care-giving, or the ‘cognitive and affective responses to the demands of caregiving and one's own behaviour in relation to those demands’ (Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, Moss, Kleban, Glicksman and Rovine1991: 181). On the one hand, individuals assess the extent to which the care-giving demands affect them on an intra-personal level (Broese van Groenou et al., Reference Broese van Groenou, de Boer and Iedema2013). This is often expressed in feelings of reward, satisfaction, uplift or gratification (Kramer, Reference Kramer1997b; Zarit, Reference Zarit2012). On the other hand, they evaluate how care-giving demands are met and infringe upon other life domains. If care-givers have difficulties in meeting care-giving demands, adverse feelings towards care-giving may arise, such as experiencing care-giving as burdensome or stressful. These two types of evaluations have often been framed as ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ experiences in care-giving (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Fee and Wu2012; Broese van Groenou et al., Reference Broese van Groenou, de Boer and Iedema2013), but were shown not to represent opposites on the same dimension as those terms may suggest. Rather positive and negative experiences in care-giving reflect different dimensions – they can occur simultaneously and differ in terms of predictors (Broese van Groenou et al., Reference Broese van Groenou, de Boer and Iedema2013).

Whether care-givers are able to draw positive experiences from care-giving is related to their motivations for care-giving (Farran, Reference Farran1997; Kramer, Reference Kramer1997a; Broese van Groenou et al., Reference Broese van Groenou, de Boer and Iedema2013). When people provide care because they like to help others, and hold a belief that providing care is a good thing in itself, rather than an obligation, the experience is more likely to be gratifying (Broese van Groenou et al., Reference Broese van Groenou, de Boer and Iedema2013). Non-kin care-givers have been found to be less likely to provide care out of obligation and have higher levels of intrinsic motivation (Lyonette and Yardley, Reference Lyonette and Yardley2003). Research has also found that religion fosters a belief system that incorporates a desire to help others (e.g. Farran, Reference Farran1997). From this line of reasoning, it can be expected that providing care to non-kin and higher levels of religiosity are linked to greater feelings of care-giving gratification.

To study negative care-giving experiences, the stress-process model (Pearlin et al., Reference Pearlin, Mullan, Semple and Skaff1990) and its modifications (e.g. Yates et al., Reference Yates, Tennstedt and Chang1999; Verbakel et al., Reference Verbakel, Metzelthin and Kempen2016) have often been used. One major commonality between these models is that they propose that intense care-giving situations are likely to be stressors for care-givers because they may ‘threaten them, thwart their efforts, fatigue them, and defeat their dreams’ (Pearlin et al., Reference Pearlin, Mullan, Semple and Skaff1990: 586) – which may result in care-giving burden and stress. Moreover, the extent to which care-givers experience care-giving as burdensome or stressful has been proposed to differ by the background characteristics of the care-giver – these characteristics define the social and personal resources available to meet the challenges of care-giving (Pearlin et al., Reference Pearlin, Mullan, Semple and Skaff1990). Taken together, both characteristics of the care situation and the care-giver are generally expected to affect care-giving burden and stress.

The work context represents another potential stressor as working care-givers may experience ‘cross-pressures and dilemmas at the junctures of care-giving and occupation’ (Pearlin et al., Reference Pearlin, Mullan, Semple and Skaff1990: 588). Even though the importance of work for understanding care-giving experiences is acknowledged in stress-process-based models (i.e. by focusing on care-givers’ appraisal of how well they can combine work and care-giving), it remains unclear in which work situations working care-givers can be expected to experience higher or lower levels of care-giving burden and stress. Focusing on structural work predictors allows identification of modifiable work conditions that may protect older employed care-givers from feelings of care-giving burden and stress.

In this study, we add structural work predictors to existing theoretical models as additional factors for explaining feelings of burden and stress in care-giving. We propose that demands and resources produced by the work situation may aggravate (or ease) the combination of work and care, and in turn, may relate to higher (or lower) levels of care-giving burden and stress. To a certain extent this might also hold true for levels of care-giving gratification, but we pay attention to this in an explorative way, given that earlier studies highlighted another type of central predictors of gratification. Overall, we focus on three different types of structural work conditions that may indicate demands (levels of work involvement) and resources (access to workplace flexibility and workplace health support) at work. We elaborate on these factors in the following sections.

Work involvement

Difficulties in combining work and care-giving may arise because care-givers need to divide their personal resources such as time, physical energy and psychological energy between work and care (Voydanoff, Reference Voydanoff2004). The extent to which people invest personal resources in a life domain depends on how important this role is to their self-concept (Carlson and Frone, Reference Carlson and Frone2003). The more involved individuals are in a role, the more difficult they find it to take resources out of that role and invest them in another role. Carlson and Frone (Reference Carlson and Frone2003) distinguish between behavioural and psychological role involvement. In essence, the more time spent by individuals on one activity, the higher their behavioural involvement with that activity. This finding is supported by research on work attachment, which shows that full-time employees are more attached to their work than part-time employees (Lilly et al., Reference Lilly, Laporte and Coyte2007). Psychological involvement refers to how much mental and cognitive effort workers invest in their work. Research has shown that higher-status workers are more psychologically involved in their work than lower-status workers (e.g. Schieman et al., Reference Schieman, Whitestone and van Gundy2006). If a greater involvement in work makes it more difficult to direct resources towards other activities (Carlson and Frone, Reference Carlson and Frone2003) such as care-giving (Gordon and Rouse, Reference Gordon and Rouse2013), care-giving may be experienced as relatively more burdensome and stressful for workers with high levels of work involvement. Therefore, we propose the work involvement hypothesis, which predicts that higher levels of work involvement as indicated by full-time employment and higher occupational status are associated with higher levels of care-giving burden and stress.

Workplace flexibility

Workplace flexibility, which is ‘the ability of workers to make choices influencing when, where, and for how long they engage in work-related tasks’ (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Grzywacz, Allen, Blanchard, Matz-Costa, Shulkin and Pitt-Catsouphes2008: 152), is highly valued by older workers (Damman and Henkens, Reference Damman and Henkens2018), and has often been proposed to ease the combination of work and care-giving (e.g. Brown and Pitt-Catsouphes, Reference Brown and Pitt-Catsouphes2016). Through workplace flexibility, working care-givers gain control and autonomy over their personal resources. Having control and autonomy at work may ease the allocation of time and energy according to the needs of care receivers. Flextime allows working care-givers to decide when to start or stop working, allowing them to arrange their work schedule in a way that is informed by the needs of the care receiver. Flexplace allows working care-givers to decide where to work and to be closer to the care receiver if needed. Phased retirement, another form of workplace flexibility, allows people to determine how much work to do by reducing the number of working hours prior to retirement, and working care-givers thus have more time to engage in care-giving. Given that care-giving is often unpredictable, the perception of access to workplace flexibility may in itself alleviate burden and stress. We therefore propose the workplace flexibility hypothesis, which predicts that older working care-givers who perceive that they can access flexplace, flextime and phased retirement experience lower levels of care-giving burden and stress than those who do not.

Workplace health support

Care-givers engage in health-promoting and health-preventive behaviour less often than non-care-givers (e.g. Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Lee and Mendez-Luck2012). Chaix et al. (Reference Chaix, Navaie-Waliser, Viboud, Parizot and Chauvin2006) propose that care-givers may be less inclined to invest in their own health because they may perceive such an investment to be unwarranted in light of the more severe health needs of the care receiver; alternatively, they may not have the energy to care for their own health. Working care-givers may be particularly at risk of not engaging in health-promoting behaviours, given that both activities may deplete resources. Arksey (Reference Arksey2002) shows that one major concern of working care-givers is their own health. However, if the organisation provides health support by offering regular medical examinations, these people may have to worry less about their current and future health status because they have sufficient access to health support. Perceptions of organisational health support may thus provide a sense of security that the organisation is also concerned with the health of its employees. This may in turn indicate a supportive work environment, which has been found to ease the combination of work and care-giving (e.g. Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Pruchno, Wilson-Genderson, Murphy and Rose2012). Along these lines, we propose the workplace health support hypothesis, which predicts that perceived access to workplace medical support is associated with lower levels of care-giving burden and stress.

Design and methods

Sample

In this study, we draw on data obtained from the first wave of the NIDI Pension Panel Study (NPPS) collected in 2015 (Henkens et al., Reference Henkens, van Solinge, Damman and Dingemans2017). This is a prospective cohort study sampled via three of the largest pension funds in the Netherlands that cover different sectors (government, education, construction, care, social work). These pension funds represent around 49 per cent of all Dutch wage-employed workers. In the NPPS, a stratified sample of organisations (N = 2,750) based on organisational size and sector was drawn. Around 1,500 small organisations (10–49 employees), 1,000 medium organisations (50–249 employees) and 250 large organisations (more than 250 employees) were selected. Within these organisations, a random sample of older workers aged 60–65 who work at least 12 hours a week (N = 15,480) was drawn. These workers received a mail questionnaire from their pension fund, but were also able to fill in an online version. In total, 6,793 questionnaires from 1,669 organisations were returned after two reminders, equivalent to a response rate of 44 per cent for participants and 43 per cent for organisations. For the analyses, our base sample consists of older workers who provide care at least once a week. After excluding respondents for whom information on the dependent variables was missing, our analytical sample consisted of 1,651 older working care-givers from 680 organisations (on average 2.4 employees per organisation). These numbers show that about one out of four older workers included in the NPPS provides informal care at least once per week.

Measures

To measure the dual nature of care-giving experiences, we focus on three types of feelings older workers may receive from care-giving activities: gratification, burden and stress. In the NPPS, respondents are requested to take all their informal care-giving activities into consideration when being asked about their care-giving experiences. The specific question asked in the questionnaire was: ‘To what extent is providing informal care …satisfactory/gratifying, …burdensome, and …stressful’. The response categories for each of the three outcomes are 1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = fairly and 4 = very.

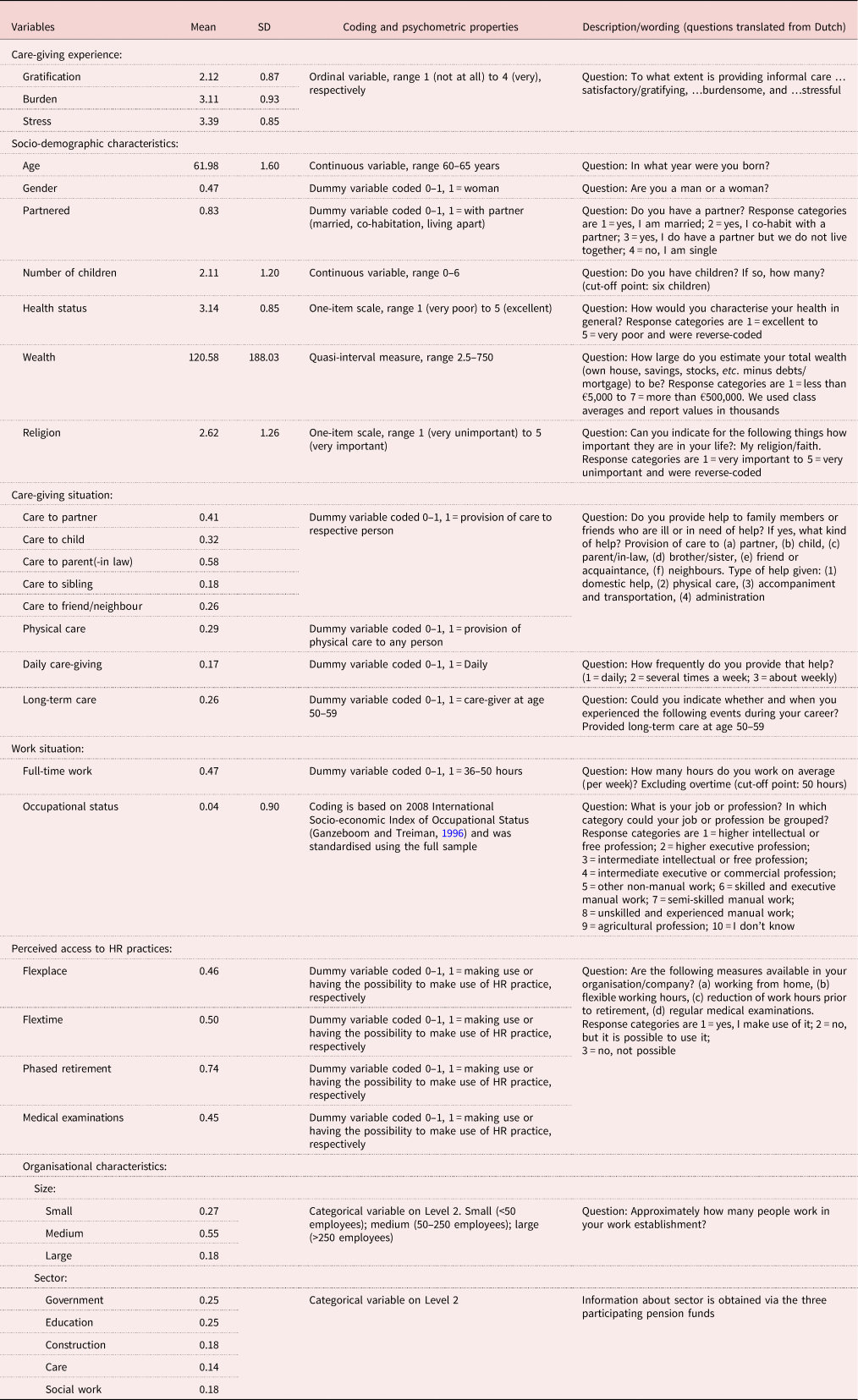

The main predictor variables are characteristics of the work situation, i.e. working hours, occupational status and the perceived access to a series of HR practices (flexplace, flextime, phased retirement and regular medical examinations). In addition, we control for well-established correlates of experiences in care-giving, namely the care-giving situation (relationship to the care receiver, physical care, daily care-giving, long-term care-giving) and the care-giver's socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, marital status, children, health, wealth, religion). We also take organisational size and sector into account. Table 1 presents the mean, standard deviation, coding and wording of survey questions for all dependent and independent variables used in the analyses. In general, item non-response was lower than 6 per cent (found in the wealth variable), and was dealt with using single stochastic regression imputation (Enders, Reference Enders2010).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, coding of independent variables and wording of survey questions

Notes: The descriptive statistics are based on the values prior to imputation. SD: standard deviation. HR: human resources.

Analyses

To investigate how care-giving gratification, burden and stress are related to the work situation of older workers, we ran three separate multi-level ordinal logistic regression models. On the individual level, we include characteristics of the work situation, measures of the care situation and indicators of the care-giver's socio-demographic characteristics. On the organisational level, we control for the size and sector of the organisation. The intra-class correlation (ICC) indicates that 1 per cent of the variation in gratification is located at the organisational level. The ICC is slightly higher for burden (ICC = 3%) and stress (ICC = 5%).

Results

To answer the first part of our research question, namely to what extent do older workers experience care-giving next to their paid jobs as gratifying, burdensome and stressful, we start with presenting our descriptive findings (see Table 1). To study the second part of the research question, focusing on how care-giving experiences are related to the work situation, we estimated multivariate multi-level models.

Descriptive findings

Overall, 70 per cent of working care-givers report that they feel fairly/very gratified with their care-giving activities. Also, a substantial proportion experience them as fairly/very burdensome (26%) and stressful (16%). There is a clear gender difference in care-giving burden and stress. The share of women who experience care-giving as fairly/very burdensome (34%) and stressful (22%) is substantially higher than among men (19% and 11%, respectively). Equal shares of men and women experience care-giving as gratifying. The correlation of the three variables (Spearman's rho) points to the fact that feelings of gratification are different from feelings of burden and stress. While the correlation between burden and stress is relatively high (rho = 0.65, p < 0.01), the correlations between gratification and burden (rho = −0.08, p < 0.01) and gratification and stress (rho = −0.23, p < 0.01) are much lower.

Multivariate findings

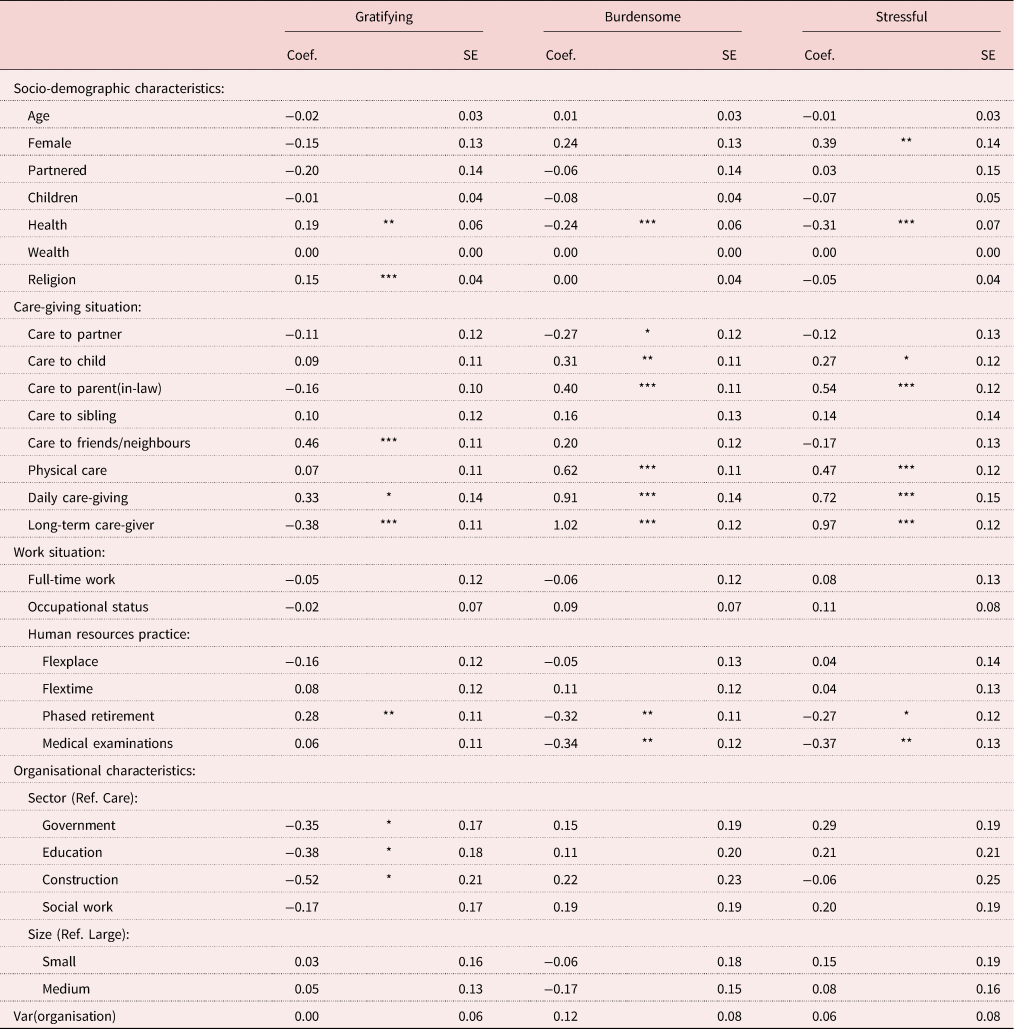

Table 2 presents the results of the multi-level ordinal logistic regression models for experiencing care-giving as gratifying, burdensome and stressful. We hypothesise that work involvement, a lack of workplace flexibility and limited organisational health support relate to higher levels of care-giving burden and stress. While we do not find support for the work involvement hypothesis, our findings are in line with the other two hypotheses. We find partial support for the workplace flexibility hypothesis. Older workers who perceive that they have access to phased retirement experience relatively lower levels of care-giving burden and stress. We find no significant differences in care-giving experiences between older workers who perceive having access to flexplace or flextime practices and those who do not have it. The results also support the workplace health support hypothesis. Perceived access to regular medical examinations is significantly linked to lower levels of care-giving burden and stress.

Table 2. Multi-level ordinal logit models of explaining gratifying, burdensome and stressful care-giving experiences

Notes: N = 1,651. Coef.: coefficient. SE: standard error. Ref.: reference category.

Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

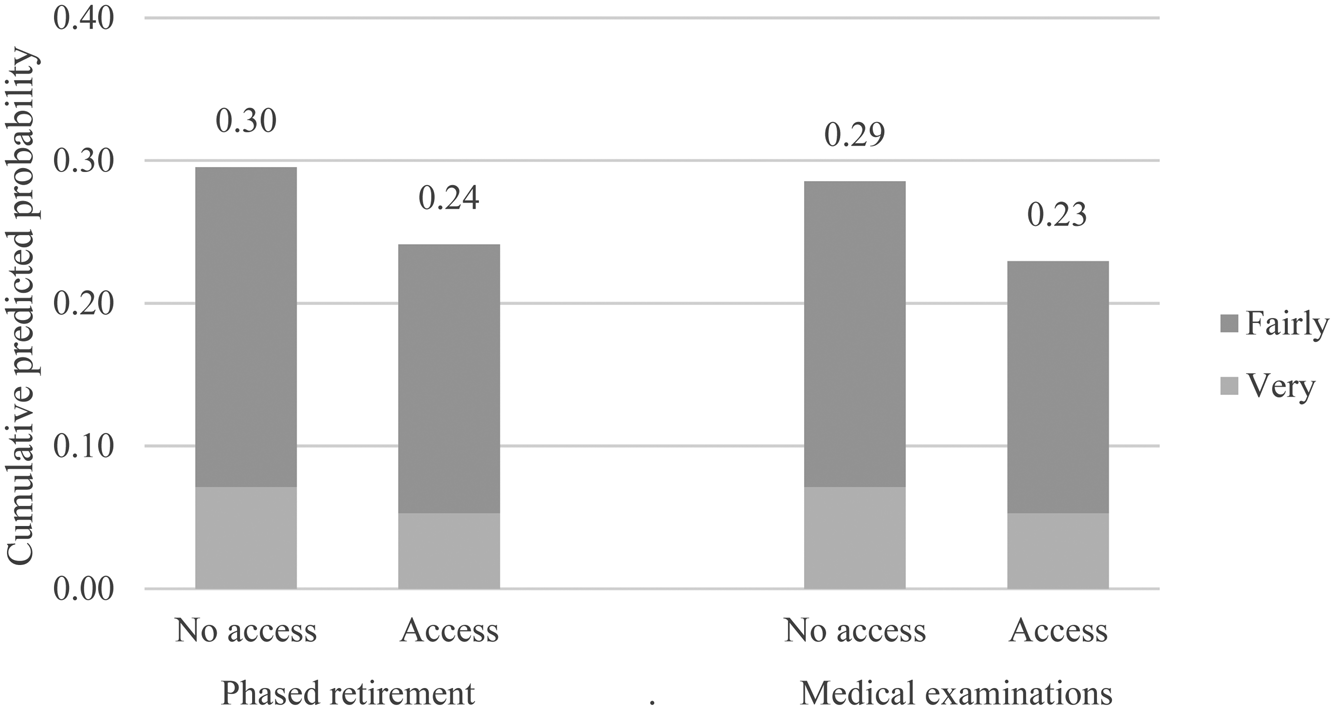

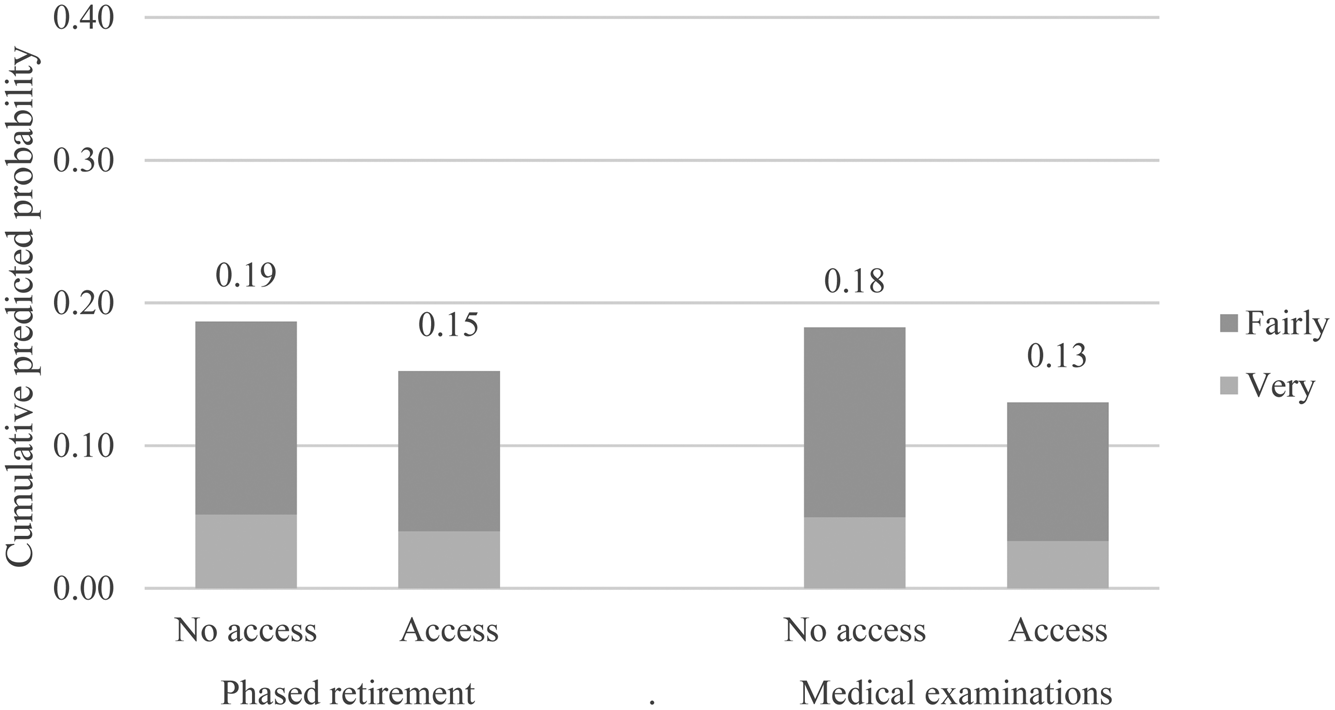

To illustrate the relationship between work situation and these experiences in care-giving, we calculated cumulative predicted probabilities for the effects of access to phased retirement and medical examinations on care-giving burden (Figure 1) and stress (Figure 2) while keeping all other variables constant (care-giving situation and care-giver's characteristics). The probability of experiencing care-giving as very or fairly burdensome is substantially lower when there is access to phased retirement (24% versus 30% when there is no access; see Figure 1, left panel). The probability of high levels of care-giving burden is substantially lower (23%) when there is access to medical examinations than in the case of no access (29%, see Figure 1, right panel). Figure 2 portrays a similar picture for care-giving stress.

Figure 1. Cumulative predicted probabilities of care-giving burden.

Figure 2. Cumulative predicted probabilities of care-giving stress.

Next to characteristics of the work situation, characteristics of the care-giving situation and care-giver are significantly linked to care-giving burden and stress, as could be expected based on the stress-process model. More intense care-giving situations, as indicated by providing physical care, daily care and long-term care are associated with greater levels of care-giving burden and stress. Also, providing care to a parent is significantly linked to greater levels of burden and stress. With regard to differences in burden and stress by background characteristics of the care-giver, we find that a lower health status is significantly linked to higher levels of burden and stress. Interestingly, the gender difference in levels of stress remains significant also when taking the work context, care-giving situation and other socio-demographic characteristics into account. Additional analyses were run to test whether the effects of the work situation on care-giving burden and stress differ by gender, but none of these interaction terms were significant.

When turning to the results for care-giving gratification, we find that perceived access to phased retirement is significantly associated with higher levels of care-giving gratification. We also find that care-givers doing paid work in the care sector experience greater levels of care-giving gratification than their counterparts in other sectors (except for social work). Furthermore, consistent with our expectations, we find that religiosity and providing care to friends or neighbours are significantly linked to care-giving gratification. Also, providing daily care is significantly linked to greater levels of care-giving gratification.

Discussion

Providing care to family members and friends is a common area of activity among older workers. This study examined to what extent older workers who provide informal care at least once per week experience their care-giving activities as being gratifying, burdensome and stressful, and studied how those care-giving experiences are related to their work situation. One prominent assumption is that combining care-giving with paid work may be difficult (e.g. Tolkacheva et al., Reference Tolkacheva, Broese van Groenou, de Boer and van Tilburg2011). Our results provide evidence that care-giving is a gratifying experience for a majority of Dutch older workers. More than two-thirds of older working care-givers experience their care-giving activities as gratifying, while one in three working care-givers get limited gratification from care-giving. At the same time, care-giving also evokes feelings of burden and stress. Around one in five older working care-givers experience care-giving as fairly or very burdensome and stressful.

For understanding in which situations working care-givers experience feelings of burden and stress in care-giving, our findings highlight structural aspects of the work situation as important predictors next to the more commonly studied care-giving situation and the socio-demographic characteristics of care-givers (e.g. Pinquart and Sörensen, Reference Pinquart and Sörensen2003; Broese van Groenou et al., Reference Broese van Groenou, de Boer and Iedema2013). This suggests that the work situation of working care-givers is not only linked to their work outcomes (e.g. Plaisier et al., Reference Plaisier, Broese van Groenou and Keuzenkamp2015), but also to their care-giving outcomes. Taking a closer look at the structural work situation of working care-givers – thereby moving beyond the subjective appraisal of the work–care combination as has been central in stress-process-based theoretical models – allows us to identify those work factors that may protect working care-givers from feelings of burden and stress in care-giving.

We find that perceived access to phased retirement is linked with lower levels of care-giving burden and stress. This finding implies that perceived control over the number of working hours, and therefore to a certain extent control over workload, may be helpful for reducing care-giving burden and stress. However, we do not find that perceived access to flexplace and flextime are significantly associated with lower levels of care-giving burden and stress among older working care-givers. Control over when and where to work seems thus not to reduce care-giving burden and stress. This seems to suggest that working care-givers who can work from home or make use of flexible working time still experience care-giving as stressful and burdensome – this may reflect the fact that they still need to be available for work and care-giving. This is particularly interesting, given that flexplace and flextime have often been proposed as ways in which organisations can support workers with care-giving responsibilities (e.g. Brown and Pitt-Catsouphes, Reference Brown and Pitt-Catsouphes2016). Our findings illustrate that working care-givers at the end of their careers may rather seek to reduce their work obligations in order to gain more time and energy – either for care-giving or to gain respite from it.

Our findings also show that perceived access to medical support is significantly associated with lower levels of care-giving burden and stress. This finding underscores the fact that the health concerns of working care-givers may pose an additional stressor and have a knock-on effect in terms of care-giving burden and stress. Given the demands of both work and care-giving, working care-givers may lack sufficient time and energy to engage in health-promoting and health-preventive behaviours next to their work and care-giving responsibilities. Regular medical examinations at work would then seem to provide a way for working care-givers to support their own health without investing additional personal resources. Because the perception of access to medical examinations is linked to lower care-giving burden and stress, organisational health support would seem to represent a form of supportive work environment for working care-givers. This is particularly interesting given that workers in the Netherlands, as well as in other European countries, have access to formal medical care (European Union, 2010) – the perception of access to medical examinations at work seems to nevertheless represent an additional form of health support that relates to lower levels of burden and stress of care-giving.

At a first glance, the difference in levels of care-giving burden and stress between those with and without access to HR practices might seem relatively small (cf. Figures 1 and 2). Nevertheless, it should be kept in mind that only aspects of the work situation, which are rather distant from care-giving experiences, are changed while keeping the care situation constant. Against this background, the difference in care-giving experiences between working care-givers with and without access to phased retirement and medical examinations can be considered as meaningful. Together our findings suggest that the availability of organisational support from employers relates to lower levels of burden and stress. Although this finding seems to hold for male and female working care-givers, more attention may still be needed for the care-giving stress experienced by older working women. The women included in this study experienced substantially higher levels of stress than men, which could not be attributed to differences in their work, care-giving or socio-demographic situation. Achieving a better understanding of these gender differences is of eminent importance for ensuring that both older employed men and women can fruitfully combine care-giving with paid employment until older ages.

This study also highlights the relevance of examining gratifying as well as burdensome and stressful care-giving experiences separately. Our results show that the antecedents of gratifying experiences in care-giving are different from those that are burdensome and stressful. In fact, some of the predictors even point in the opposite direction, suggesting that the same care-giving situation can evoke different sorts of feelings in care-giving. Working care-givers who provide daily care experience greater feelings of gratification but also greater levels of burden and stress. This may suggest that these individuals are self-selecting into more intense forms of care-giving because of a motivation to care for others. In support of this view, we also find that care-givers doing paid work in the care sector experience relatively high levels of care-giving gratification, and this is also the case for more religious older workers as well as for those providing care for friends or neighbours. Both employment sector and religiosity are unrelated to levels of care-giving burden and stress. Our findings thus support the notion that positive and negative care-giving experiences are distinct from one another, rather than being opposites within the same dimension.

In interpreting these findings, some limitations should be borne in mind. First, our dependent variables, namely care-giving gratification, burden and stress, are measured using single indicators. This may have limited our ability to capture the full range of positive and negative care-giving experiences. Second, we use a cross-sectional sample that prevents us from testing the effect of the use of HR practices on care-giving experiences. The use of longitudinal data could allow conclusions to be drawn about whether the actual use of HR practices reduces care-giving burden and stress, and should be the focus of future work. Third, this study takes place in the Netherlands, which may limit the generalisability of the findings to other countries with different welfare regimes.

In general terms, because older workers are expected to work longer but also to care more for dependent family members and friends, questions arise regarding how they experience care-giving next to their paid job. Our findings clearly show that care-giving could be a gratifying as well as a burdensome and stressful experience for working care-givers, and that their work situation is important for explaining care-giving burden and stress. In light of the closure of early retirement routes and higher retirement ages, older workers’ agency over their retirement timing has become more restricted. Offering access to phased retirement would appear to ensure that working care-givers retain the autonomy to decide when and how to withdraw from the labour market, which could in turn alleviate care-giving burden and stress. Specifically, in times of extended careers and given the ever-increasing numbers of dependent people, organisations can be seen as important actors in shaping the workplace in such a way that future cohorts of informal, working care-givers can successfully combine care-giving with paid work.

Financial support

This work was supported by The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (KH, VICI grant number 453-14-001; MD, VENI grant number 451-17-005) and Netspar.