Introduction

The term ‘archaeoprimatology’ describes a relatively new sub-discipline that involves primatology and archaeology (Urbani Reference Urbani2013). The blue monkeys found in Minoan frescoes have been the focus of decades of research (e.g. Masseti Reference Masseti1980; Vanschoonwikel Reference Vanschoonwikel, Hardy, Doumas, Sakellarakis and Warren1990; Rehak Reference Rehak, Betancourt, Karageorghis and Laffineur1999; Greenlaw Reference Greenlaw2011; Pareja Reference Pareja2017). This study is paradigmatic in considering them as part of the first reported interface of non-human primates with a European civilisation inhabiting the major islands of the Central Aegean Sea.

Methods

As part of ongoing research that will be the focus of a forthcoming publication, we revisited the literature on the representation of non-human primates on Minoan archaeological sites. As part of this research we re-examined evidence from frescoes, seals (both handling parts and printing surfaces), pendants, figurines and jewellery; undertook field visits to sites with frescoes of non-human primates in Crete and Thera; and studied the current taxonomic classification and distribution maps of North African primates (Mittermeier et al. Reference Mittermeier, Rylands and Wilson2012, constantly updated by the International Union for Conservation of Nature).

Re-examining the evidence

The frescoes at Akrotiri, Thera and Knossos, Crete, strongly suggest that Minoans were familiar with two species of cercopithecid monkeys: vervets (Chlorocebus spp., probably C. aethiops or C. tantalus) and baboons (Papio spp., possibly P. anubis or P. hamadryas) (Urbani & Youlatos Reference Urbani, Youlatos, Legakis, Georgiadis and Pafilis2012; Pareja Reference Pareja2017) (Figure 1). Philips (Reference Phillips2008a & Reference Phillipsb) and Greenlaw (Reference Greenlaw2011) have further identified portable objects that resemble baboons in this Bronze Age society. Both primate groups were probably originally represented at Minoan sites after having been observed on the African mainland (Masseti Reference Masseti, Kotjabopoulou, Hamilakis, Halstead and Gamble2003; Doumas Reference Doumas, Aruz, Graff and Rakic2013). There is alleged archaeological evidence for the presence of Minoans in North Africa, from the site of Avaris, present-day Tell el-Dab'a, in Egypt (Bietak & Marinatos Reference Bietak and Marinatos1995).

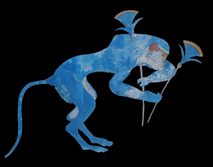

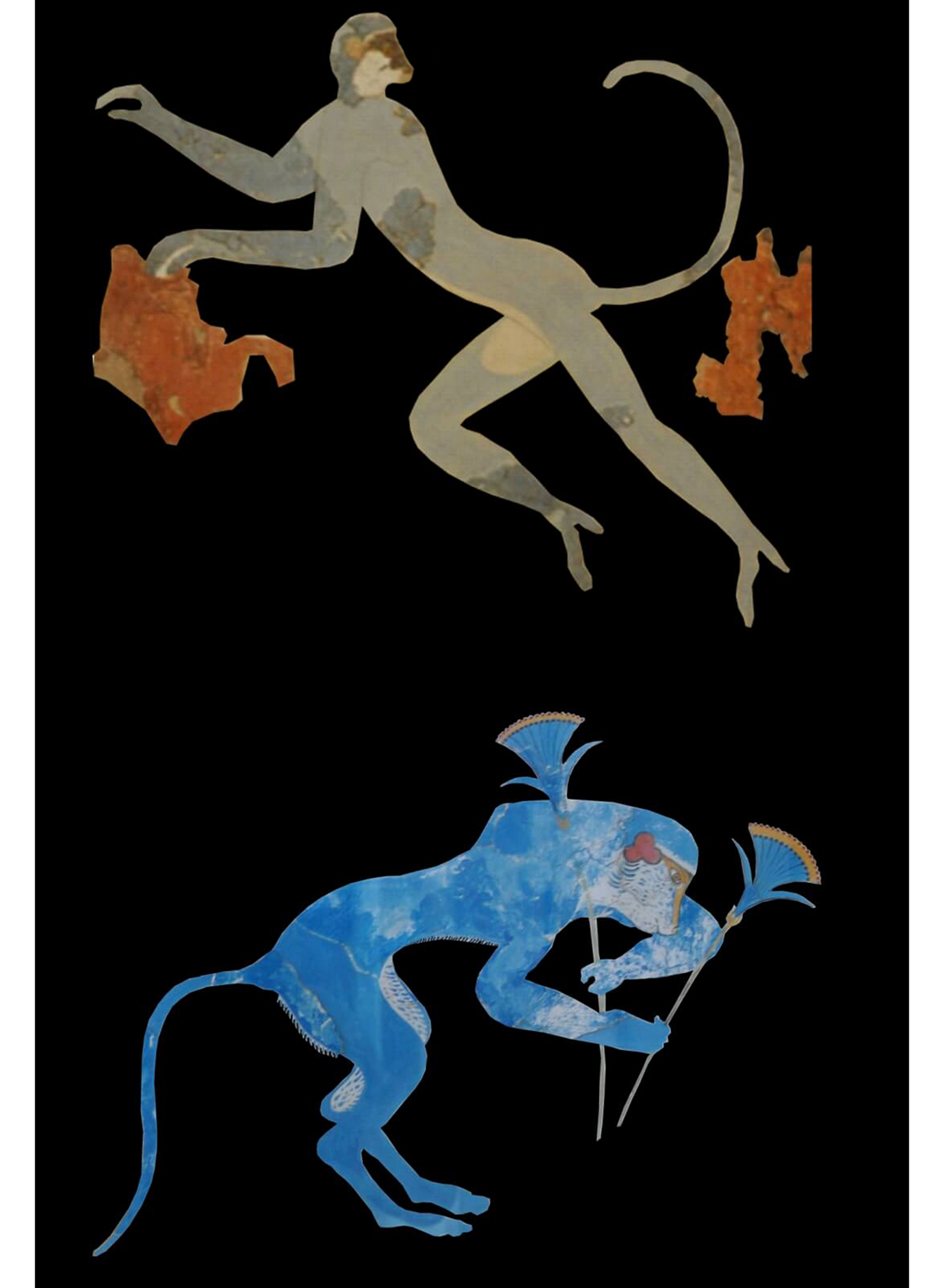

Figure 1. Two cercopithecids in Minoan frescoes: top) vervet monkey depicted in a fresco at Akrotiri, Thera; below) baboon shown in a fresco at Knossos, Crete (photographs by B. Urbani).

Vervet monkeys are represented in Thera (Complex Beta) and are depicted in a landscape context (Figure 1). Morphological features such as the rounded, short dark greyish/black muzzle, rounded face and cheeks, white band on the forehead, white ventral area, as well as elongated arms and limbs, and extended tail, are key characteristics for their generic identification. A versatile positional repertoire and non-terrestrial behaviours depicted at Complex Beta support this identification.

On the other hand, baboons seem to be related to sacred contexts and are associated with flower offerings or gathering, as well as using swords and playing music on lyre-like instruments at Thera (Xeste 3) and Crete (Knossos) (Figure 1). A set of physical traits such as short hair in the inguinal part, narrow waist, dorsal position of the tail base, elevated limb configuration, long muzzle and prognathic face, expanded thorax in relation to the whole torso, and hairless nasal dorsum are characteristics of papionins. Furthermore, baboons are represented as terrestrial, reflecting their original behaviour in the wild.

Conclusions

In Minoan imagery, particular monkeys seem to be distinctly related to certain contexts. The small-bodied, agile and naturalistically represented vervet monkeys were most often associated with leisure activities. Whereas the larger, sturdier, more terrestrial baboons—monkeys that were already deified in nearby Egypt (Philips Reference Phillips2008a; Greenlaw Reference Greenlaw2011; Pareja Reference Pareja2017)—were attributed more anthropomorphic behaviours and depicted in sacred or ritual events. This Aegean Bronze Age society, then, was the first European civilisation to perceive, represent, socially construct and, eventually, have contact with non-human primates. The representation of primates in Minoan contexts confirms the early exchange of iconography and knowledge of monkeys among Aegean islanders, and substantiates their interaction with human populations from North Africa that might have had these primate species living around their coastal settlements.

The colour of the pelages (hair) of both baboons and vervets falls within the grey/olive-grey range, but they are consistently represented as blue in Minoan frescoes. We suggest that—as observed in other societies (e.g. Roberson et al. Reference Roberson, Davinoff, Davies and Shapiro2005)—the use of blue to represent Minoan monkeys might be explained as a colour abstraction within the grey/green scale (see also Philips Reference Phillips2008a). In this way, vervets and baboons represent ideal living models for an iconographic and chromatic hypothesis in which grey/green is represented by blue. In fact, blue was also used by Minoans to represent metallic, grey-like surfaces (Peters Reference Peters, Jackson and Wager2008), such as fish scales (Gill Reference Gill1985). Moreover, the colour blue was widely and symbolically used by Egyptians in divine contexts (Schenkel Reference Schenkel, MacLaury, Paramei and Dedrick2007; Concoran Reference Concoran and Goldman2016); Minoans may have borrowed it to represent exotic animals, such as monkeys (e.g. Greenlaw Reference Greenlaw2011).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the librarians at the Biblioteca della Scuola Archaeologica Italiana di Atene, the Begler Library of the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, and the Historical-Archaeological Library of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki for their help and support. Our thanks also go to the personnel at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, the Herakleion Archaeological Museum (Iraklio, Crete), the Museum of Prehistoric Thera (Fira, Santorini) and the archaeological sites of Knossos and Akrotiri. B. Urbani was funded by an I.K.Y. post-doctoral fellowship (Greek State Scholarship Foundation, Ministry of Education of the Hellenic Republic). Travel to Crete was supported by the School of Biology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. We appreciate the cooperation of Yoly Velandria and Ana María Resnik, and the constructive comments of an anonymous reviewer on earlier versions of this text.