The multipartite conflict in Vietnam ended as North Vietnamese tanks rolled into Saigon in 1975 after decades of conventional and guerrilla warfare involving a dozen combatant nations and a civil war among multiple groups within Vietnam. The dramatic ending of the conflict created an exception that rewrote the military rules for asymmetric war between insurgency and counterinsurgency: the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN), a poorly supplied force, defeated a coalition of strong allies composed of military forces from the Republic of Vietnam, Australia, South Korea, and the United States – the most powerful country in the world.

Why the North Vietnamese soldiers fought, what their experiences were, and how their perceptions shed insight on the terms of victory or defeat remain controversial questions that lead to polarizing debates. A staple of the discourse on these issues is the fundamental war of memory, divided not only between different persons, but also, more imaginatively and dramatically, within persons and contexts. The anticolonial fighters, in the view of many American combatants, were supermen who could see in the dark and move invisibly over all types of terrain, willingly sacrificing their lives for their cause. At the opposite extreme, others described them as emaciated, subhuman peasants, allegedly brainwashed, who employed terror as a weapon and often struggled to muster the morale to stand and fight.Footnote 1

During the war, limited studies were conducted on the motivations of PAVN soldiers, primarily through interrogations of defecting or captured soldiers. However, the reliability of these sources is undermined because the testimonies were extracted under threat of torture and death. The PAVN experience remains largely unknown as the bulk of current war studies is unbalanced toward American experiences, with little to no scholarship attempting to understand Vietnamese perspectives. Concurrently, official Vietnamese histories, collective in nature, may not adequately reflect individual stories for political and cultural reasons, eschewing both individual aggrandizement and the evidentiary approach typical in conventional historiography in the East and the West.

There could be no better evidence of the unfiltered experience of North Vietnamese soldiers than dissecting their organic memory. A unique category of historical materials offers new facts and interpretations, each soldier’s distinct narrative shaped by genuine knowledge and a wide array of experiences. Over the past decade, my research has involved a painstaking process of historical inquiry and investigation into the personal memories of the PAVN found in uncensored documents within the Combined Document Exploitation Center (CDEC), captured on the battlefield by US armed forces and the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). With its millions of pages of handwritten diaries, missives, journal entries, and political and military reports, to name just a few, the CDEC collection stands as a treasure trove of “the definitive documentation on the revolutionary side in the Vietnam War,” allowing historians to “write a complete and balanced account of the War.”Footnote 2 Authored by combatant-eyewitnesses in their native Vietnamese language, these war documents contain vital yet untapped information that could shed light on the fate of many PAVN soldiers and serve as a crucial resource for researchers seeking to gain a deeper insight into the war and its consequences.

These raw materials expand knowledge about the enlistment, deployment, and rationale of the PAVN, as well as political tensions within the communist party known as the Lao Động or Vietnamese Workers’ Party (VWP) and divergent opinions among the Vietnamese regarding the cause of the war. Importantly, these battlefield documents uncover individual fighters’ feelings of nationalism and familial and individual duty, along with their personal impressions of life during wartime, experiences of depression, and their nostalgia for home and their families.

Vietnamese institutional history concentrates primarily on collective memory regarding the conflict, making these unexpurgated materials unique in offering bottom-up perspectives. They enrich and provide a personal form of history that runs parallel to the official narratives dictated by the controlling authorities. This process enables an understanding of how personal memory may conflict or be compatible with collective memory, as well as how it may be used to shape or even reshape the stories of history.

Through this examination, a new perspective emerges on the frontline experiences of combatants, revealing evidence that challenges the notion of the PAVN as an undefeated force. It illuminates the reality that it was a conscript, rather than volunteer, army, comprising soldiers who were neither robots nor political zealots. Undeniably, the heroism of PAVN soldiers is embodied in their unwavering determination, resilience, and sacrifice against unimaginable struggles. Yet, as human beings in the field, they were often homesick draftees pitted against equally pitiable, equally homesick conscripts wearing US and other uniforms. This chapter exclusively examines Northern-born fighters and does not encompass individuals originating from the Southern region who joined the PAVN.

Path to the War

Writing while still on the battlefield, for the Northern fighters, was an active struggle of individual human beings for the truth. Despite the party’s harsh censorship, they engaged in this struggle to recount their efforts, interpret the reality of events, and create meaning from their impressions. While revolutionary writings tend to be collective, the soldiers’ reflections were deeply personal. This contrast made their writing an actual war of thought, torturing their hearts and minds, because they were forbidden to write about the dark side of the war or express their real feelings in letters sent home, as mandated by the party’s military security discipline.

Cao Vӑn Thơ, a sapper in the 15th Engineer Battalion on the B5 or Quảng Trị front, considered keeping diaries to be a “new way of life.” It allowed him to reflect on truth and facts while nurturing the hidden emotions in his heart. To him, protecting his combat diary was nothing less than fighting for survival. He determined that “protecting the notebook is like protecting our heart and truth.”Footnote 3

At the core of many North Vietnamese fighters’ personal memories lies the conflict between the revolutionary ideal indoctrinated in them by the party and the tragic plights caused by the war. An entry in the diary of an unidentified soldier from Hà Đông illustrates his struggle, juxtaposing the revolutionary ideal against the grim truth of “frenzied death” experiences he faced during wartime. On September 12, 1964, the day he departed from his homeland to join the PAVN, he lamented:

It’s over! All aboard! Oh dear! That order tore my heart. I was forced to depart. Where do I go? […] Go with the [revolutionary] ideal. What is this ideal? […] Um, I understood, but now I had to part from my beloved homeland. I had to leave my darling […] Oh dear! It was gut-wrenching for my heart! So long Hà Đông! […] How glorious the frenzied deaths were [in the days of wartime].Footnote 4

The war in the South, for which the unknown soldier sacrificed his prime of life, was portrayed by the party not merely as a single armed conflict, but instead as a multifaceted class struggle across various fronts. As articulated in the official history of the PAVN, it constituted a “historic confrontation” between socialism and capitalism – a clash between forces of the national liberation revolution and those orchestrating aggression, seeking to enslave all nations of the world under a new form of colonialism.Footnote 5

These ideological confrontations were intertwined in a dual war from beginning to end: a patriotic war for the national liberation of Vietnamese revolutionaries against American invaders, and a multipartite civil war among Vietnamese groups within a tempest of diverse motivations and perceptions.Footnote 6 Cemented by a dogmatic view asserting that a “revolutionary spirit would enable the insurgent forces to overcome the technological superiority of the enemy,” the hawkish leaders dominating the Central Committee of the VWP remained blind to the realities of inferior military capabilities, human resources, and economic constraints.Footnote 7 Their pursuit fixated on waging an asymmetric war of attrition against both domestic and foreign adversaries, irrespective of any costs incurred.

Employing the language of political convenience, the party and its totalitarian system intertwined nationalism and communism, fueled by a fervent socialist patriotism that created a powerful effect on the morale of the nation as it mobilized mass support for the war. To the PAVN, military service signified an “experiment in the political attitude of people from all levels of the national community” during the revolutionary war of the era of Hồ Chí Minh.Footnote 8 Central to this political experiment was the evaluation of how the “socialist new men” expressed their “political attitude” in response to the new patriotism of Marxism-Leninism, national independence, and socialism, which differed from the traditional patriotism of the past.Footnote 9 The larger-than-life collective heroism and socialist patriotism strongly resonated among soldiers, many of whom hailed from families steeped in revolutionary tradition or were poor peasants, landless laborers, or affiliated with the communist party. The majority of these men and women were former Việt Minh fighters during the French Indochina War (1946–54). Dedicating their lives to the party, the revolution, the fatherland, and the people, the communist-led Northern warriors, according to the histories of the PAVN, embodied a “political consensus.” United as one, they ignored every hardship and sacrifice, and fought resolutely until achieving total victory.Footnote 10

Trần Vân, an experienced combatant who fought in the protracted resistance war against the French colonialists before 1954, and then against the Americans in the South, expressed in his writing the real-life hardships he had endured, along with his enthusiasm for the national liberation struggles in which he participated. On October 10, 1965, the battle-hardened soldier penned a letter to his brother, Trần Tuân, who resided in Thái Nguyên province, to convey his personal thoughts and motivations. He proclaimed:

Actually, the cause of revolution is still difficult. It faces many sufferings and losses. Day after day, month after month, and year after year, I had to live as a homeless person in the jungle that has never ever seen a soul throughout the past thousands of years. The food we have now is worse than that in the war against the French, and this is true, because I have personal experiences from the resistance against the French in both regions [North and South]. While fighting against the French, we only had to support one zone of operations and we received much foreign aid. Now, we have to support the development of socialism in the North; then war in a friendly country [Laos], and carry out the war in the South, which has already lasted ten years. My brother! I write about these hoping that you will understand the resilience of your brother. My eyes have been directed toward killing the American enemies.Footnote 11

Such points of view offer insight into the minds of the communist soldiers, showing their perception and dedication to the revolutionary ideal – an era marked by a new form of combat aimed at liberating the South from American imperialism and its puppets while simultaneously developing socialism in the North. Yet, Trần Vӑn’s revolutionary zeal did not align with what the party deemed the “political consensus,” as North Vietnam was not a monolithic entity, but a contested land.

This divergence was not solely a result of diversified culture and tradition, but was exacerbated by a series of the party’s dogmatic Maoist campaigns. These campaigns encompassed brutalities such as land reform, the repression of the Nhân vӑn–Giai phẩm (Humanity–Masterworks) intellectual movement, and the Anti-Party Revisionist Affairs in the 1950s and 1960s. Their aim was to eliminate oppositional elements that were labeled counterrevolutionaries or antiparty cliques. This resulted in the purging of numerous military and political cadres, patriotic landlords, middle-class peasants, nationalistic bourgeoisie, and intellectuals, and the punishment of deviationists who disagreed with the party’s stance on the war.

Consequently, these repressions triggered a profound crisis across moral, political, military, social, economic, and cultural dimensions, previously unseen in the territory north of the 17th parallel. Such seminal changes contributed to the erosion of Vietnamese national solidarity, causing internal confrontations within the party and dividing opinions among the North Vietnamese communities regarding war policies. These divergences created dynamic yet contested debates, weighing the pros and cons of the revolutionary war, thereby fueling a struggle within the recruitment, fighting, and sustaining motivations among Northern-based soldiers, particularly those who came of age after 1954.

In response to the party’s political campaigns since 1954, the PAVN underwent an accelerated transformation. Initially a united front military army under the Việt Minh banner during the French Indochina War, it evolved into a “tool of proletarian dictatorship” by the time of the Vietnam War, with 40 percent of its cadres and troops being communist party members.Footnote 12 The burden of conscription weighed increasingly upon Northern citizens, particularly after Lê Duẩn, First Secretary of the Central Committee of the VWP, and his hawks won the vote for Resolution 9 at the 9th Plenum in December 1963. This vote officially rejected Hồ Chí Minh and his doves’ policy of “peaceful coexistence and peaceful competition.” Instead, it favored Lê Duẩn’s formula, advocating armed struggle as the decisive factor in generating a violent general uprising to seize political power “in a relatively short period of time.”Footnote 13

Resolution 15 of 1959 was the “opening shot” of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN) in its Anti-American Resistance War for National Salvation.Footnote 14 However, Resolution 9 of 1963 became a pivotal turning point in the conflict across two zones. First, it halted prolonged battles in the South’s path to revolution, elevating Lê Duẩn to paramount leader within the party’s war machinery as he had assumed control of the Secretariat of the Central Committee VWP from Hồ Chí Minh at the 14th Plenum in November 1958. Second, it authorized a more extensive war effort aimed at achieving Southern liberation and national reunification, involving the deployment of PAVN regulars to join the fight in the South.Footnote 15

To implement Resolution 9 and counter American intervention in South Vietnam, PAVN infiltration significantly escalated from 1964 onward. During this time, only Lê Duẩn and his top officials were aware that, while the first US combat troops were landing in Đà Nẵng in March 1965 to support South Vietnam, preparations were underway for the arrival of the first communist-led Chinese ground forces to bolster North Vietnam. By June 1965 these troops crossed Ải Nam Quan, also known as Friendship Pass, under a “secret agreement” brokered between the DRVN and the People’s Republic of China in December 1964.Footnote 16 As per this clandestine pact, from June 1965 to March 1968, approximately 320,000 Chinese personnel – combat soldiers, engineers, military workers, and anti-aircraft operators – arrived in North Vietnam. Their objectives varied, from constructing transportation infrastructure to developing anti-aircraft systems and defending strategic positions in territories north of the 17th parallel.Footnote 17

As North Vietnam secured its territory with assistance from China, the Soviet Union and its bloc of East European socialist allies, and North Korea, which provided financing and military equipment, including sophisticated air defense systems, the North Vietnamese state intensified military infiltration. On March 8, 1965, the PAVN promulgated the Special Resolution of the Urgent Situation and Mission to expand its armed forces. A notable aspect of this special resolution was the implementation of indefinite conscription orders to “increase the regular army forces by reenlisting ex-servicemen, recruiting more draftees, [and] extending the enlistment period” in accordance with combat requirements.Footnote 18

The party did not simply depend on voluntary efforts to mobilize people for war; rather, it established a Maoist/Stalinist system comprising political–social organizations, public security, and military power to monitor every aspect of life, including the family registration system. This totalitarian policy ensured that every single draft-age male would be enlisted, making military service unavoidable for Northern citizens. More importantly, the authorities tightly controlled people’s living conditions, providing subsidies for food, money, goods, and production tools. They also applied social, economic, and political forms of discrimination, punishing draft evaders while rewarding those who enlisted. In essence, North Vietnamese individuals found themselves in a difficult situation – caught between the “devil and the deep sea” (đi thì mắc núi, ở lại thì mắc sông). Consequently, they compelled themselves to move forward, unable to evade military service.

In reality, many men, whether volunteers or conscripts, especially those from rural areas, joined the army not only due to government conscription but also for the economic and political benefits offered or promised by local authorities. Enlisting in the army provided an opportunity for impoverished farmers to escape their hardship and improve their social standings. The majority of PAVN members were the main laborers or breadwinners of their family. When they were sent to war, their families would receive an immediate allowance, at least 60 North Vietnamese piasters (North Vietnam Dong), before their departure to the South. The immediate or long-term allowances, job security, and sociopolitical conditions varied based on whether families resided in rural or urban areas.Footnote 19

According to the Journal of Communism (Tạp Chí Cộng San̉), between 1954 and 1975 approximately 70 percent of households in the North had one or two family members in the army.Footnote 20 Thái Binh, a rural province in the Red River Delta, alone contributed half a million soldiers to the war effort.Footnote 21 General Vӑn Tiến Dũng, Chief of the General Staff of the PAVN, mentioned in his limited-distribution handbook that, from 1965 to 1975, 1,928,500 individuals mobilized into the armed forces, with 935,500 deployed to the South.Footnote 22

The Life of a Soldier

Nguyễn Huy, a 26-year-old private first class, drafted on April 24, 1963, in Nam Định province, came from a family of non-Catholic farmers. He was among the initial Northern-born regulars sent to the South following Resolution 9. His testimony revealed that his unit, Battalion 70 of Regiment 9 in Division 304, departed from the North on February 1, 1964, and infiltrated the South in April 1964, marking the first deployment of a PAVN regular unit to the Southern battlefield.Footnote 23 Nguyễn Huy recounted that 90 percent of the 600 enlistees in his battalion were not volunteers but draftees. Throughout their three to six months of training, he and his inexperienced comrades struggled under unfamiliar military discipline. Although some raw recruits initially displayed enthusiasm upon joining the army, their morale declined during training. The lack of freedom made them lethargic and weary during military drills and political lessons. Despite being indoctrinated about the common duty of the North Vietnamese toward their Southern compatriots, some individuals “requested to stay in North Vietnam.” He further affirmed that, “even if they risk losing their civil rights, or being faced with prosecution before a military court, they were ultimately forced to infiltrate South Vietnam under the control of the cadres.”Footnote 24

Nguyễn Huy’s statement is corroborated by the account of his comrade, Vũ Quang, who was drafted from Thanh Hóa province. A twenty-year-old farmer and Buddhist soldier in Battalion 802 observed that the morale of many soldiers in his unit was “poor,” and they were disinclined to go to the South.Footnote 25 This antiwar attitude did not stem from their training, but arose from the reluctance and disagreement among draftees who were compelled by the mobilization orders to go to war. Vũ Quang disclosed that “before 1962 draftees could return home after two years of military service, but from 1963 the term of military service was indefinite. The youths sent to South Vietnam for combat were haunted by the fear of death.”Footnote 26

The harsh conditions and the looming specter of death at the front caused many enlistees to desert the army rather than march to “B” (the code name for the Southern battlefields). Đinh Vinh, a VWP member who enlisted the army in 1954 and reenlisted in 1965, stated:

As Tết [Lunar New Year] was about to begin, they were given ten days’ leave to visit their families prior to beginning the infiltration journey […] During the training, their morale was high and they were eager to begin infiltration. However, morale dropped after Tết because the men suddenly began to realize that they might never see their families again. This led to approximately forty desertions.Footnote 27

The indefinite military service often produced many forced volunteers rather than enthusiastic soldiers. Many men questioned the nature of the war, its immense sufferings and losses, and conscription policies. Vũ Vӑn Lang, a draftee from Hải Dương province in 1965, admitted that his reenlistment in the army under the coercive mobilization of that year was a “harsh responsibility” that forcibly separated him from his family. His diary entries unveiled his lack of enthusiasm as a revolutionary soldier:

April 10, 1965. I received the reenlistment order that I must accept. At 10:00 a.m. tomorrow I have to leave my homeland. I feel very sad because I have to part from my mother and my wife, whom I married just three months ago. I feel it is a very harsh responsibility. I left my house at 7:00 a.m. I see, for the last time, my mother, my brother, and my wife. My heart is broken. I thought to myself, “my honey, now I have to leave you.” My appearance is very calm, but deep in my heart I saw how my life would be full of hardship.Footnote 28

Vũ Vӑn Lang’s experience was not unique in terms of the emotional toll exacted by wartime conscription. His plummeting morale finds an echo in the diary of an unidentified soldier conscripted into Regiment 812 of Division 324 in May 1965. Initially enthusiastic about joining the army to become a uniformed man, he could not help but weep for leaving his young wife, uncertain whether or not he would return. He bemoaned:

The problem I have has two aspects: military life is certainly a glorious one, but by the same token it is hard to be separated from my wife […] Tears poured out of our eyes without our knowing it. We wonder when we shall see each other again. The reunion will take place only after the reunification of the country if both of us survive. Otherwise … At this moment, my parents, brothers and sisters could not imagine the difficulties I have to face. Alas! … War! … Death! … My tears keep falling. No! I am not a coward, but as a human being I cannot help being sentimental, especially [when my wife] is my true love. Now is the time to leave […] I do not know what to tell her. I can see her broken heart by looking in her eyes. It will be a long, long time before I can see her again.Footnote 29

Regardless of the circumstances of enlistment, the indefinite military service was described as a harsh law within his war memories, as he expressed, “separation has always been painful.” Many North Vietnamese men and women had to leave their homeland for the South without a definite date of return. While the unit cohesion of American combatants was eroded by their twelve-month tour, the morale of PAVN soldiers was equally affected by the protracted war and its open-ended enlistment terms.

Throughout the war, more than 1,300,000 poorly supplied cadres and troops traversed the Hồ Chí Minh Trail, covering a distance of 3,700 miles (6,000 km) on foot along its commo-liaison routes, extending to five fronts in South Vietnam.Footnote 30 These routes formed part of a complex system of military stations spanning the western flank of the Annamite Cordillera, also known as the Trường Sơn range in Vietnam, northeastern Cambodia, and southern Laos.

The march along this trail subjected soldiers to daunting challenges, including jungles, mountain passes, bombings, river crossings, malaria and other diseases, food poisoning, encounters with wild animals, self-inflicted injuries, suicide, starvation, and thirst. On average, a staggering 20 to 30 percent never completed the journey to the South.Footnote 31 One study from Vietnam highlighted that many soldiers from new units collapsed on the march due to exhaustion or poor health. In one of the most severe cases, a regiment of 2,800 soldiers departing from the North had dwindled to a mere 1,200 upon reaching their final destination in the South.Footnote 32 In a letter to General Võ Nguyên Giáp on March 31, 1966, General Hoàng Vӑn Thái, Deputy Chief of the General Staff of the PAVN, reported that “we recently sent our armed forces to the South in a disorderly manner, resulting in an increase in deserters. This situation produced many difficulties both in the South and on the trail.”Footnote 33

The challenging conditions endured in the jungle proved exceedingly difficult for all the common soldiers, even determined ones like Vӑn Linh. The grueling march took a toll on his physical strength, forcing him to “go by his head” as his legs refused to cooperate. This educated soldier expressed his frustration, stating:

I […] encountered a lot of difficulties: muddy and slippery roads across mountains, streams, and bridges that had been destroyed by the Americans. This is called “go by your head” because the legs do not want to go […] It is frightful and terrible to move along the Trường Sơn mountain range […] I find no peace of mind to sleep, because aircraft fly overhead uninterruptedly […] I start to live a miserable life […] Do you all know that I am so miserable? I wish to explode in madness, but I cannot.Footnote 34

Beyond the impact of American bombings, starvation inflicted significant psychological wounds on many soldiers. It remained a persistent issue throughout the war. Nguyệt Quế, in particular, was tormented by relentless hunger. He also grappled with feelings of shame regarding the prevalence of theft within the army, as starvation drove some revolutionary soldiers to desperate measures:

Starvation tormented my body. It also tormented my heart and mind. I could not sleep because I craved food. It was sad and reproachable when starvation forced many people to steal their comrades’ rice ball. When would I become a victim who was pilfered from and when would I become a pilferer? This is a bad phenomenon of our revolutionary army.Footnote 35

These wartime deprivations resulted in the unjust deaths (chết oan) of many soldiers. The fear of such a death haunted them even before they engaged in actual combat. Bearing witness to the loss of comrades-in-arms in a prolonged war against hunger and disease caused mental anguish among the PAVN’s soldiers. The relentless warfare against the French and the Americans left devastating impacts on the lives of the Vietnamese people. Deprivation has the power to alter a wide array of human characteristics, transforming human thoughts and behavior into those of an animal. Vӑn Linh bitterly compared the two:

I have the impression that I am living the life of primitive men. The water is dirty, everything is dirty […] Oh! What an uncivil thing to live on feces which give out a stink; meals are also taken near feces. It is indeed a life of “primitive men”! We never believed that we would return to the life of primitive men! […] Sometimes I lie like a dead man except that I’m still breathing. What a life fraught with hardships!Footnote 36

While the official state history avoided discussing deserters or the struggles soldiers faced, personal memories of soldiers fill this gap by providing clear evidence on these subjects. In an entry dated February 29, 1968, in Trần Qui’s notebook – which was sent to President Lyndon Johnson for its valuable insights in the lives and motivations of North Vietnamese soldiers – he described more than 300 desertions from Group 926 due to B-52 raids along the route to Khe Sanh in February 1968.Footnote 37 Despite the risk of punishment, this combatant privately expresses a perspective on the motivation of the fighter that diverges from the collective point of view. He stated:

It is true to say that going to fight the Americans is not the same as going to a festival or a musical show or a dance party. Conversely, it should be understood that going to fight the Americans is a matter of becoming familiar with hardships and countless sufferings. I would like to say that every one of us must suffer ten times as much as in every day of life.Footnote 38

Political Struggle

Trần Qui’s diary serves as a dynamic repository of facts, offering a multifaceted perspective from a PAVN soldier. It delves into his thoughts on the war and its impact on both the military and civilians, stretching across the rear as well as the frontlines. As an educated individual, he acknowledged the crucial role of the party’s leadership and its collectivist ideology in shaping a disciplined army. However, he perceived the party and its propaganda as a politically convenient “sweet medicine” used to manipulate people into joining the struggle against the Americans. One underlying theme in his observations is that, despite the political education and strict discipline maintaining morale, they were not entirely the driving forces motivating the soldiers. For Trần Qui, traditional patriotism and nationalism formed the foundational motivation for the revolutionaries during the war. The PAVN soldiers drew inspiration from national history, fighting for independence, their way of life, their homes, and the survival of their nation.

While the resistance war against the American imperialists was portrayed as an ideological conflict through a totalitarian system of propaganda, Trần Qui’s perspective differed. He fought willingly for a national cause – yearning for powerful sovereignty, a heroic nation, independence, unification, and freedom for the Vietnamese people from foreign aggressors. He resisted being labeled a socialist or communist zealot, unwilling to become a “slave” under harsh military and political rule. His steadfastness is evident as he refused to join the VWP Youth Union six times after infiltrating the South in 1966.

In Trần Qui’s eyes, patriotism was an inherent spirit innate within all Vietnamese, deeply ingrained in the traditional solidarity against foreign invaders. It was not spurred by any specific ideology but by a sense of duty and responsibility to protect and liberate their homeland. The paramount obligation lay in embracing the sacred duty of becoming a warrior when the country faced the threat of war. Trần Qui delved deeply into the history of his country’s national heroes and their historic achievements. During his march to the South, he vividly recalled inheriting the glorious legacy of these ancestors when he had the privilege to go to Nghệ An province, site of the Nghệ–Tĩnh Soviets Uprising, or Phong Trào Xô Viết Nghệ–Tĩnh, a series of uprisings, strikes, and demonstrations in 1930 and 1931 by peasants, workers, and intellectuals against the French colonialists. He took tremendous pride in visiting the temple of Bà Triệu, a revered heroine of Vietnam, cherishing the heroism and nationalism, embodied in her words, “I want only to ride the wind and walk the waves, slay the big whales of the Eastern Sea, clean up frontiers, and save the people from drowning.” Yet, he also experienced sorrow, empathizing with the sufferings and losses of local people in Quảng Bình, the homeland of General Võ Nguyên Giáp. Trần Qui encountered the brutal realities of war, witnessing death and grief even before his departure to the South. He mourned:

I stay at Hóa Sơn, Tuyên Hóa, Quảng Bình. Here, there is a family with a son who has also died in the B, leaving behind a young wife and a small child, his mother, and a younger brother. That is the fate of the ill-fated who have passed away, leaving behind an eternal sorrow for the widow. It is a wound to the heart that cannot be erased, as it is filled with so much suffering. No matter how much one wishes to erase or buy away that sorrowful pain, it cannot be bought, even with one thousand taels of gold. [There is a poem that says:] “At home you should remarry [because] I’m going to the South with no way home.”Footnote 39

This reveals that his genuine motivation is that of a patriotic nationalist, rather than a communist. An even more radical departure is seen in Nguyễn Lập Dương’s “Memories of the Past Two Years, 1964–1965,” a diary captured on November 10, 1966. This soldier, a combatant in Division 325, never mentions the party or its ideological doctrine when describing the cause of the war. The fighting motivation of this soldier originates in his hatred for the Americans, whom he refers to as “white devils.” In his mind, revolution is not a class struggle; it is associated with the resistance against enemies to save the Vietnamese nation. Liberating the South from the invaders was the basis of his determination. This soldier wrote to his mother:

My beloved mother, the enemy is currently destroying our village. When I think of that bombing raid, I hate and resent the enemy. Now, the white devils [Americans] have dominated us, but I am sure that soon our people will annihilate them and they will have to leave our Fatherland. Their weapons and bayonets cannot stop the people of this revolution. I could not forget you, a mother who has sacrificed all her life for the revolution. The more I miss you and the villagers, the more I try to overcome hardships. I remember that we need to kill a lot of the enemy in order to unify our country.Footnote 40

Human will, a sense of duty, and racial animosity transformed personal virtue into a catalyst for the country’s cause, fostering a patriotic fervor that dominated his thoughts. This mindset led to his enlistment initially and continued to drive him to fight vehemently. Duty, honor, and patriotism sustained him in the field, while the impulses of courage, self-respect, and group cohesion motivated him on the battlefield. The prowar soldier recalls:

My squad includes nine men. They come from Hải Dương, Nam Định, Hà Nam, and Thanh-Nghệ-Tĩnh. We lived together as biological brothers. On May 3, 1965, we participated in a large-scale battle on Route 21 between Buôn Ma Thuột and Di Linh. Our forces only had two platoons, but we managed to defeat one battalion of the enemy.Footnote 41

This fighting motivation was radicalized by Vương Luỹ, a seasoned communist fighter experienced in the Central Highlands. He interwove nationalism with communism, sculpting himself into a dogmatic and radical fighter entirely dedicated to the party. Firmly believing that being human necessitated being a communist, he stated, “I am a human being, I shall be a communist.” He further explained, “since the party had trusted me, I had to devote myself fully to getting the job done, to study hard, to rid my mind of pessimistic and conceited thoughts.”Footnote 42 Despite his dislike of “political training, which everyone found more boring than the march,” Vương Luỹ recognized its role in enhancing leadership, and self-discipline among enthusiastic communists, fostering shared experience among comrades. The PAVN soldiers were organized into three-man cells and, managed by a dual system of political and military leadership within each unit, formed a cohesive army. While military leaders commanded fighters in combat, political commissars managed soldiers’ thoughts and attitudes, encouraging collective responsibility and promoting steadfast morale, determination, and a revolutionary spirit. This was done by eradicating pessimism and individualism in challenging situations through ideological training, including “criticism and self-criticism.” As William Darryl Henderson notes in Why the Viet Cong Fought, the concept of “man over weapons” was critical in the techniques used by the North Vietnamese army to bolster motivation, morale, and group solidarity around party norms.Footnote 43 This morale finds reaffirmation in Cao Vӑn Thơ’s resolute language. Reflecting on his initial days in the South, he notes, with a hint of romanticism:

The hardships have no effect on the spirit of the revolutionary soldiers, who are enthusiastically confident in the final victory of the party. Nothing can discourage them. They are ready to face any enemy at any time. The sound of their guns can be heard everywhere. Also, they are honorable soldiers of the South Vietnam Liberation Army and I am one of them […] For the first time, I infiltrated into the South […] Oh! Dear little Bến Hải river. It is no more than 30 meters [33 yards] wide but it divided Vietnam in two. For a long time, I have dreamed of visiting this river. Today my dream came true as I am standing there, with my feet in fresh water.Footnote 44

When faced with the fierceness of the American bombings in the Quảng Trị battlefields at the B5 Front, this volunteer soldier candidly admitted, “How terrible it was when I witnessed the B-52 bombardment that night […] I was so frightened that I could not even reach the shelter even though it was only a meter away.”Footnote 45 In numerous memoirs, the soldiers revealed how their revolutionary ardor swiftly perished in the Trường Sơn mountains. They encountered horrendous deaths among infiltrators, brutal bombings, bloody combat, tropical diseases, and an inhospitable environment in the field. The grim reality and their frustrating experiences largely permeate the memoirs and reflections of these soldiers, including the diary of Hoàng Vi Mai, which was captured on March 14, 1967, by the US 25th Infantry Division. Hoàng Vi Mai hailed from a “nonreligious” family of “middle-class peasants” before the August Revolution of 1945. He publicly demonstrated his loyalty to the revolution and its class struggle by applying for party membership. Employing the zealous yet soulless words often found in a political petition within the communist world, this farmer-soldier radicalized himself as a “socialist new man” in the pursuit of Marxist-Leninist ideology, aiming to transform his status from an ordinary to a revolutionary fighter. He pledged:

I am aware that the party is an organization of the working class. Marxist-Leninism is the foundation and guide for the party. The goal of the party is to accomplish the national and democratic revolution to lead Vietnam to socialism. The party is built by the most progressive, enlightened, and determined workers who courageously sacrificed themselves for the revolution. Especially, although this course of war for liberating South Vietnam [from the invaders] is very harsh and difficult, our party is artfully leading [our people and forces] to achieve many glorious victories. As a liberation army fighter, who recognizes that the duty of the party is very heavy but glorious, I would like to devote my life to the revolution. Thus, I volunteer to join the party.Footnote 46

Portrayed as an ardent combatant, wrapped in dogmatic writings, Hoàng Vi Mai surprisingly revealed a deeply introspective side in his private journal, where he shared his observations, reflections, and the stark realities of the war. His diary offers an unorthodox and contradictory perspective, diverging from the typical mindset of Northern soldiers depicted by Trần Qui, Nguyễn Lập Dương, and Vương Luỹ. Trần Qui upholds the national spirit, Nguyễn Lập Dương makes sacrifices driven by revolutionary patriotism, and Vương Luỹ struggles for the party and its ideal, but Hoàng Vi Mai exposes the raw and brutal truths of human actions during the war. His diary concentrated on the “great loss” caused by the violence. He displayed profound concern for the individual destinies of fighters, trapped in a destructive war that inflicted pain upon all Vietnamese youths and their families:

November 24–25, 1965. Upon reaching the territory of Military Region V, we thought we would be granted one or two days of rest and recuperation, but we were not. For two days and nights, the war raged fiercely close to us. Bombs and bullets rained on the jungles and mountains of this heroic land […] The war has taken the lives of so many North Vietnamese youths. The party and the country have lost so many beloved sons who sacrificed their lives for the cause of the party. This great loss, suffered by the party and the country, is also a great loss for the families of the dead. This is only the initial phase, yet many men are demoralized. More than 50 percent have been sick. How dark life is! When can we return to the North?!Footnote 47

Hoàng Vi Mai’s narrative delineates a gradual decline in morale. More significantly, in his adoption of a strong antiwar stance, he defies the party’s official taboo on discussions of the war. He adamantly believed that the so-called revolutionary war for national liberation was not the “just war” portrayed in the propaganda. Rather, he condemns it as a “murderous war” that has claimed the lives of a tragic generation of youths, describing them as “born in the North to die in the South.” Hoàng Vi Mai portrayed himself and his young comrades as innocent victims manipulated into being part of a war of attrition. He abandoned the pen for the sword, joining the army as a ninth-grader, fully aware of the plight of young people, enduring what he termed the “devastating and poignant war.” In a confession to his brother, this antiwar soldier grievously denounced the party for stealing the beautiful lives of teenagers who suffered the same fate as he had:

Dear brother! Please understand that I have been going through the most distressing days. How devastating and poignant the war is! It has stolen the spring of all our lives, fledglings who know nothing about life except schoolbooks. Yet they are now compelled to participate in this murderous war! I did not expect life to be so rocky and so wretched! Please understand my situation. If I am able to see you again sometime in the future, I will share everything with you in detail. But if I cannot, please do not suffer and calm your grief.Footnote 48

Armed Struggle

During their war against the United States and its allies, the communist-led revolutionaries adeptly employed the distinctive strategy of “two legs and three spearhead-attacks” (hai chân, ba mũi giáp công), aiming to incite a general offensive and general uprising in three key areas: rural, urban, and mountainous regions. The term “two legs” referred to the combination of political and military struggles while “three spearhead-attacks” encompassed military and political action as well as propaganda and agitation among enemy troops. This approach was geared toward capturing the hearts and minds of the people while achieving combat objectives. To execute this strategy, PAVN soldiers served as the core forces, enduring countless hardships and shouldering the primary burden of major combat operations, shedding their blood on the frontlines.

From the beginning of the “real war” between 1965 and 1975, the PAVN’s objective was to confront the US armed forces and their allies for a “decisive victory” as envisioned by Lê Duẩn to prepare for the 1965 general uprising in the South.Footnote 49 In 1966, the conflict escalated significantly following the Politburo’s approval of senior general Nguyễn Chí Thanh’s aggressive strategy. Thanh, Secretary of the Central Office of South Vietnam (COSVN) and political commissar of the People’s Liberation Army of South Vietnam (PLAF), advocated a shift from guerrilla warfare’s focus on small-unit tactics to “massed combat operations and launch[ing] medium-size and large-scale campaigns by our main-force units in the important theaters of operation.”Footnote 50 He declared that the armed struggle for national liberation in the South had transformed into a war against American aggression. Thanh emphasized the need to avoid “returning to the defensive and resistive strategies [from the French Indochina War], and instead urged continuous attacks to destroy the enemies, defend and expand our liberation areas, and claim both land and people.”Footnote 51 Adopting the motto “Determined to Fight, Determined to Win” (Quyết chiến, Quyết thắng), symbolizing the confidence and resoluteness of the revolutionary army, Thanh believed that, even with limited resources, his troops, poor yet courageous, displayed professional and disciplined fighting abilities, ensuring a “decisive victory in a relatively short period.”Footnote 52 Despite this ideology emphasizing an offensive stance across all aspects of war – “strategy, operation, and battle”Footnote 53 – the PAVN suffered significant losses in the major battles. However, driven by the offensive strategy, the PAVN and PLAF persisted from 1965 to 1975 in conducting a series of large-scale military campaigns, notably the Tet Offensive of 1968 and the Easter Offensive of 1972, disregarding military regulations and battlefield realities.

Following the battlefield disasters from 1968 onward, the burden of the bloody war of attrition shifted from the PLAF to the PAVN. By the Easter Offensive of 1972, the PAVN was bearing about 90 percent of the day-to-day combat, resulting in increasingly heavy casualties.Footnote 54 After the Quảng Trị campaign, Lê Đức Thọ, head of the Central Organizing Commission of the VWP, in discussion with Henry Kissinger, the United States national security advisor, argued that the goal of the 1972 Quảng Trị Citadel battle had been to gain a political advantage in negotiations. He emphasized that, in military terms, a fierce battle for such a small, devastated area is futile.Footnote 55 However, as a sacrifice to achieve this political goal, approximately 80 percent of the human power and facilities of the liberation army in Quảng Trị was destroyed. Their forces were rapidly depleted, with regiments reduced to 800–900 troops, and companies dwindling to only 20 to 30 soldiers, some with merely 4 or 5 fighters left.Footnote 56 The 81-day fierce battle in the Quảng Trị Citadel and its claimed victory remain a subject of dispute. General Nguyễn Hà, who commanded a PAVN regiment during the operation, admitted that “the result of this battle was of modest significance since it caused a huge loss for the PAVN without contributing decisively to the Paris Peace Accords.”Footnote 57

Throughout the war, North Vietnamese soldiers faced a staggering casualty rate, with at least six soldiers dying for every US soldier.Footnote 58 To replenish their forces in the South, starting in 1966 the DRVN implemented an extensive military and political mobilization in the North. This mobilization’s objective was to rally soldiers and civilians nationwide to join the war effort.

The US military estimated a significant increase in infiltration: from a previous annual high of 12,900, it surged to 35,300 in 1965, further escalating to 89,000 in 1966, then fluctuating between 59,000 and 90,000 in 1967, and eventually peaking at about 150,000 in 1968.Footnote 59 Gerard DeGroot’s analysis suggests that nearly 200,000 males reached adulthood annually in North Vietnam, producing a pool of 120,000 eligible men. However, to meet the demands of the war of attrition in the South, the PAVN extended the age of military service to range from sixteen to forty-five.Footnote 60 This urgent recruitment drive resulted in a significant issue: young recruits lacked proper training and were easily killed in combat, while older enlistees faced health problems and perished in the harsh jungle conditions.

As the conflict grew more violent, the soldiers became more depressed. These disastrous developments on the battlefield affected the morale of many soldiers. In his diary, Hoàng Vi Mai began to distinguish between himself and “them,” and his inquiries started covertly criticizing either his immediate officers or the national leadership:

January 1, 1966. Gia Lai. The barren land of Gia Lai province does not appeal to me. There is nothing that endears me to this place, which they dub the second homeland! No vegetables and meat can be found here. We have nothing for food except salt, salted shrimp paste, and dried fish. How unbearable life is! Worse, there are no streams in which to bathe except a mudhole large enough for a water buffalo to wallow in. How dreary is the life of a member of the Liberation Army! There is nothing for the Lunar New Year celebration! I feel sad beyond words. In what way does the war benefit them?Footnote 61

The distressing experiences of Hoàng Vi Mai are paralleled by those of Bắc Thái, a radio operator in Battalion 2, Front 5, in his diary on December 1, 1969. Like Hoàng Vi Mai, Bắc Thái finds neither revolutionary enthusiasm in his duty nor a promising future in his life. In this war, he saw lonely victims rather than heroic fighters. More radically than Hoàng Vi Mai, this educated fighter expressed straightforward reproaches of the leadership:

I was planning to eventually enter the faculty of medicine or pharmacy and in the near future receive a certificate of medicine. But unfortunately I had to join the army […] After the recent operation phase, Battalion 2 suffered more than 100 KIAs. Nothing gives me greater anguish than to see my friends die. Our party cleverly uses letters of commendation and citations to lure us to the battlefield to receive nothing but certificates of dead heroes.Footnote 62

By defying military discipline and ignoring political theory that required Northerners to dedicate themselves simultaneously to the people’s army and to the people’s war, this soldier continued to lament the immense sufferings endured by the combatants:

Today is the second day that we have lived on the socialist land. We understand the difference between the two sides of the Bến Hải River. One side is hell, and the other side is paradise with liberty. Do the people living in the beloved socialist North Vietnam know that more than sixty of our youths and teenagers who left the North for duty never returned with us, because they were KIA in the deep forests of the Southwestern region (Tây Nam Bộ)? We feel sorrow and regret for our unfortunate comrades who sacrificed their lives for us. Their relatives will suffer a great deal when they learn that these men were KIA.Footnote 63

In her book Hanoi, Mary McCarthy observes that the North Vietnamese state exuded confidence in the invincibility of the nation. As a result, while amplifying its victories, the government avoided discussing its losses.Footnote 64 This propaganda not only encouraged the soldiers to fight in the South, but also fostered a sense of security among the Northern populace, instilling faith in the party and prompting them to send their children to war. However, the exaggerated portrayal of military successes exposed the infiltrators to danger when encountering actual disasters on the battlefield.

Nguyễn Đức Nhuần, a gunner in Battalion 700, Regiment 302, recounted a cruel reality. After two months of arduous marching to the South, infiltrators “faced the truth, which they found to be completely contrary to the propaganda.” They had been told that “two-thirds of SVN [South Vietnam] had been liberated,” but they found no safe shelter and “were compelled to hide day and night in jungle. Their lives were constantly threatened by shelling and bombing from US and South Vietnamese [ARVN] forces, leading to a steep decline in morale.”Footnote 65 Consequently, they had no choice but to endure severe hardship, fight to the death, desert their units, injure themselves, or commit suicide. Bắc Thái’s reflections on the war disclose a bitter truth about the destinies of PAVN soldiers not often documented in the historical records of either Vietnam or the United States: some Northern soldiers and cadres resorted to suicide due to the relentless challenges on the battlefield that completely crushed their morale. He remembered:

Recently, DI [Battalion 1 of Regiment 27, B5 Front] suffered heavy losses when their bivouac area was raided by enemy troops. Commanding cadres with such a poor spirit for fighting will soon drive us to complete destruction. I still remember that during a battle in Khe Sanh in 1967, Senior Captain, commanding officer of a battalion of Regiment 246, committed suicide on the battlefield because he had sacrificed so many of his men.Footnote 66

The fear of death and the atrocities of war drove soldiers to desperation, leading to self-inflicted injuries in the hope of being evacuated from the frontlines or avoiding further combat. This circumstance is evident from captured medical reports from hospitals of the liberation army. Hospital 211 in the Central Highlands alone, from 1968 to the middle of 1969, recorded fifty-four cases of cadres and troops attempting self-inflicted wounds, using AK assault rifles, CKC carbines, pistols, detonators, explosives, and grenades to mutilate themselves by shooting their own feet or hands, or using knives, shovels, and pickaxes to chop off their fingers.Footnote 67

The intensification of the war, characterized by ceaseless combat operations blending guerrilla and conventional actions, not only wore down the “aggressive will” of the US combatants, but also eroded the self-confidence of their PAVN adversaries. Instead of celebrating revolutionary heroism or showing pride in the party’s noble cause, they were distressed, lacking hope for a final victory. Hoàng Vi Mai wrote in frustration:

Everything is despair. What will our lives be like tomorrow? It will be very hard and unfair if our lives of tomorrow are the same as they are today! How frustrating life is! To whom should I unburden myself? In whom should I confide? Who can understand my pent-up feeling? No one could possibly, except us, the soldiers!Footnote 68

While grappling with diseases amidst the harshness of the jungle, Northern soldiers endured many challenging days in the South, which not only drained their determination in combat but also impaired their physical vigor. These psychological traumas and discontented attitudes are poignantly depicted by an unidentified soldier who recognized how physical exhaustion deeply affects one’s mental state. For him, the war was not simply about killing the enemy on the battlefield, but also a battle against starvation. In his eyes, “Rice is blood. Manioc is tears. Salt is perspiration. How powerful are hunger, thirst, and weariness.”Footnote 69

More strikingly, some PAVN soldiers underwent torment due to a “shrinkage of [their] social and moral horizon,” resulting in declining morale and a departure from the ethical principles they had learned before the war.Footnote 70 This internal conflict could trigger mental instability. In a sorrowful poem, another unknown regular soldier, grappled with guilt, accused himself of being a criminal rather than a liberation soldier. His perception of the war was not one of national liberation but a civil war plunging the Vietnamese into the bitter plight described as “meat boils in a leather pot” (nồi da xáo thịt). This metaphor, drawn from folklore, depicts the seething anger and the self-destruction inherent in civil war and fratricide. Questioning why he was sent to the South to kill compatriots transformed him from a revolutionary soldier into an antiwar one. The antagonistic introspection pervades every single word:

The contrast between the noble ideals and harsh realities forced him, expected to ardently believe in the revolution, to painfully reassess his political and fighting motivations. Numerous writings and testimonies by cadres and troops revealed internal strife between the North Vietnamese infiltrators and South Vietnamese natives, including members of the National Liberation Front. Lieutenant Colonel Tần Xuyên, Assistant Chief of Staff and Chief of Operation Section of Division X and an experienced warrior who had participated in the battle of Điện Biên Phủ in 1954, acknowledged that “the contradictions between the Northern cadres and the Southern cadres are truly hard to solve, due to the prevailing envy and dispute within and among groups.”Footnote 72 The division between the Northern and Southern sides is further underscored in the writings of an anonymous soldier, who bitterly expressed that he and his comrades did not receive a warm welcome in the South. He observed, “we are not greeted as liberators in the villages. Instead, when we arrive, people ask us to leave, fearing that our presence will attract enemy planes to come and strafe the village. I feel like a leper.”Footnote 73

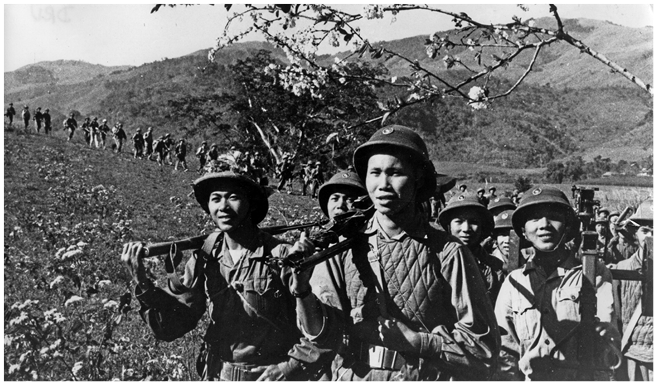

Figure 9.1 Soldiers of the People’s Army of Vietnam during training exercises (1968).

Amidst the intense combat on the frontline, the souls of the combatants were tormented by homesickness. Nostalgia and melancholy damaged the morale of the North Vietnamese soldiers, but these spiritual factors also served as a source of hope. For them, the prospect of returning home to reunite with their families was the ultimate inspiration, empowering them to face and overcome the challenges of fierce battlefields. Vũ Vӑn Lang, mentioned earlier, yearned for home, his thoughts filled with longing for his mother and his wife. Despite being a liberation army soldier, he penned, “I feel very sad and homesick. My thoughts linger on my homeland, my mother, and my wife. I am certain my wife misses me greatly and perhaps she weeps so somewhere. Oh! I want to return to my wife!”Footnote 74

This homesickness deepened the divide and self-destructive situations between the North and the South. Hoàng Vi Mai’s heartfelt sentiments toward his hometown, family, and relatives amidst the bloody battlefield demonstrate that, rather than desiring to fight and die in combat zones, his longing was to return home to the North. He imagined:

Days and months pass helplessly. I am pining away in eternal grief and sorrow. Homesickness drowns me when I imagine that my loved ones are impatiently looking forward to hearing from me and to seeing me back home. My mother will be very old, because she worries about me so often. Since the day I left home, there has not been a single moment that I have not thought of my family. How I miss the days I spent at home with my brothers and sisters! I wish I could go home. How I hate this war!Footnote 75

Faced with the indefinite enlistment in the rear and enduring the endless horrors of the war’s frontline, North Vietnamese men found themselves ensnared in an inescapable predicament. Returning home was not an option, and fleeing to other regions or nearby countries to evade the conflict was equally impossible due to the intense warfare. Consequently, they were left with no recourse but to fight – not just for the war effort, but for sheer survival. This harrowing reality made them somewhat more fatalistic, acutely aware that their fate within the war would culminate in only one of two outcomes: victory or death. This sentiment echoed in a Vietnamese wartime saying, “Either become green or return with a red chest” (một xanh cỏ, hai đỏ ngực), encapsulating the stark choice between meeting a premature end, symbolized by the green grass of burial on the battlefield, or returning home adorned with red medals, signifying glory and honor.

The anticommunist South Vietnamese and their allies viewed the North Vietnamese fighters as cold-blooded soldiers, while in North Vietnam they were hailed as heroic vanguards of revolution, who were sacrificing their lives for the nation, often portrayed through the lens of stereotypical heroic–romantic myths. Neither of these historical perceptions fully aligned with the Northern fighters, who perceived themselves as ordinary soldiers whose motivations were similar to those of the combatants of any other war. Vӑn Linh, for instance, did not see himself as a revolutionary or cold-hearted warrior, but rather a “fledged bird flying into a storm and rages of the winds.” The war ended with victory for the North, achieving the goals of liberating the South and reunifying the country. However, in his introspective writing, this young soldier questioned his own sense of national duty, confronted individual hardship, and pondered the rights and wrongs of the war, which was consuming the prime of his life. On March 21, 1966, he poured out his inner turmoil:

My prime of life has come to an end like the death of spring while I am serving my country. I am now but a bag of bones […] Oh! How terrible it is […] That is why I said “I am like the death of spring.” I am not sure whether the war is right or wrong. One can only judge it after the end of hostilities. The bird will expect to experience more hardships when it flies into the enemy’s net of fire. Life and death hinge upon destiny […] Dear friends and comrades, I drop a few lines noting the events of my life. I hope that you will sympathize with me […] It would be fine if I could survive; otherwise please send this diary to my parents.Footnote 76

Conclusion

The above questions posed by this PAVN soldier about the war persist across multiple generations. His deep concern underscores that the war is not merely a festering wound in the American national psyche; it is also an enduring pain at the heart of the Vietnamese experience. In her book Hanoi’s War, Lien-Hang T. Nguyen highlights that, while Washington’s conflict with the Vietnamese communists during the Cold War had “undeniable losers,” the memory of Hanoi’s war for peace and unification reveals that “there were no clear-cut victors.”Footnote 77

The authentic documents from North Vietnamese combatants challenge the implanted perception and history of the war, reshaping its myths through the war of memories. These unique materials indicate that the PAVN was not entirely composed of enthusiastic volunteers dedicated to the revolutionary cause. While some were fervent communists, many shared emotions akin to those of soldiers in wartime – patriotism, heroism, antiwar sentiment, brutality, frustration, loneliness, homesickness, and boredom.

The divergent motivations and morale among them demonstrate that the war they fought was not solely a people’s war; it was, to a large extent, the party’s war. Instead of molding revolutionary heroes, it transformed numerous innocent youths into conscipted soldiers, sufferers of a prolonged war, both in the North and in the desolate landscapes of the South. Understanding the depths of their ideologies and experiences can contribute to a new and nuanced comprehension of victory or defeat from various, deeply personal perspectives. As this issue continues to resonate, the personal memories of PAVN soldiers who endured the war are not merely vehicles of personal remembrance; they represent a force that still shapes the history of the Vietnam War. They offer insights into the motivations, challenges, and perceptions of any war during any period in history.