For decades, the reflexive approach to archaeology has advocated for the embedding of interpretation into (and the impossibility of separating interpretative practices from) the primary fieldwork context. Hodder's keystone piece on reflexive excavation methodology is partly premised upon multivocal dialogue that begins “at the trowel's edge” and goes “beyond a method which excludes and dominates” (Reference Hodder1997:694), integrating a diversity of specialist and nonspecialist interpretative perspectives on the data into the standard disciplinary workflow. As the reflexive method has been elaborated and critiqued over time (e.g., among many, see Davies and Hoggett Reference Davies and Hoggett2001; Spriggs Reference Spriggs and Hodder2000), its core aim of democratizing knowledge creation in the field such that “everyone on site is contributing and, recursively, benefiting from the easy, integrated flow of data and interpretative information” has arguably held firm (Berggren et al. Reference Berggren, Dell'Unto, Forte, Haddow, Hodder, Issavi, Lercari, Mazzucato, Mickel and Taylor2015:444). This commitment to the supposed democratization of interpretation extends beyond those immediately on the archaeological site itself, encompassing wider publics too. Summarizing the Çatalhöyük Research Project's particular take on it, Farid writes,

The archaeological community has a duty to diverse stakeholders—local communities, the public, tourist industries and national and international policy makers—and . . . all these voices should be represented in the research agenda and the interpretation of the site or, at the very least, . . . they should be provided with a platform to express their ideas or concerns [Reference Dunn2015:59].

Such words are reminiscent of various conceptions of public archaeology and community archaeology (see Richardson and Almansa-Sánchez Reference Richardson and Almansa-Sánchez2015 for a recent summary of the state of affairs of these subfields; also Grima Reference Grima2016) and echo the principles of public access and engagement that give structure to many local, national, and international archaeological organizations today. In other words, even where reflexivity is not an acknowledged priority—or where it has long underlain practice in unspoken form—an inclusive, recursive approach to interpretation, at and beyond the trowel's edge, is relatively standard in contemporary archaeology.

As such, it is all the more surprising that the field of heritage interpretation, which I define loosely here as the development and presentation of knowledge about the past for varied audiences, is absent from most conceptualizations of archaeological interpretation and indeed from much of the core discussion of public and community archaeologies themselves. Heritage interpreters, despite their role in mediating the discipline for different individuals and groups, are often distanced from the process of archaeology—shut out of the primary collection, organization, and interrogation of the raw data gathered via (reflexive) field methods. As I see it, this is not only a deep irony of contemporary archaeological methodology but also a limiting factor for the profession at large.

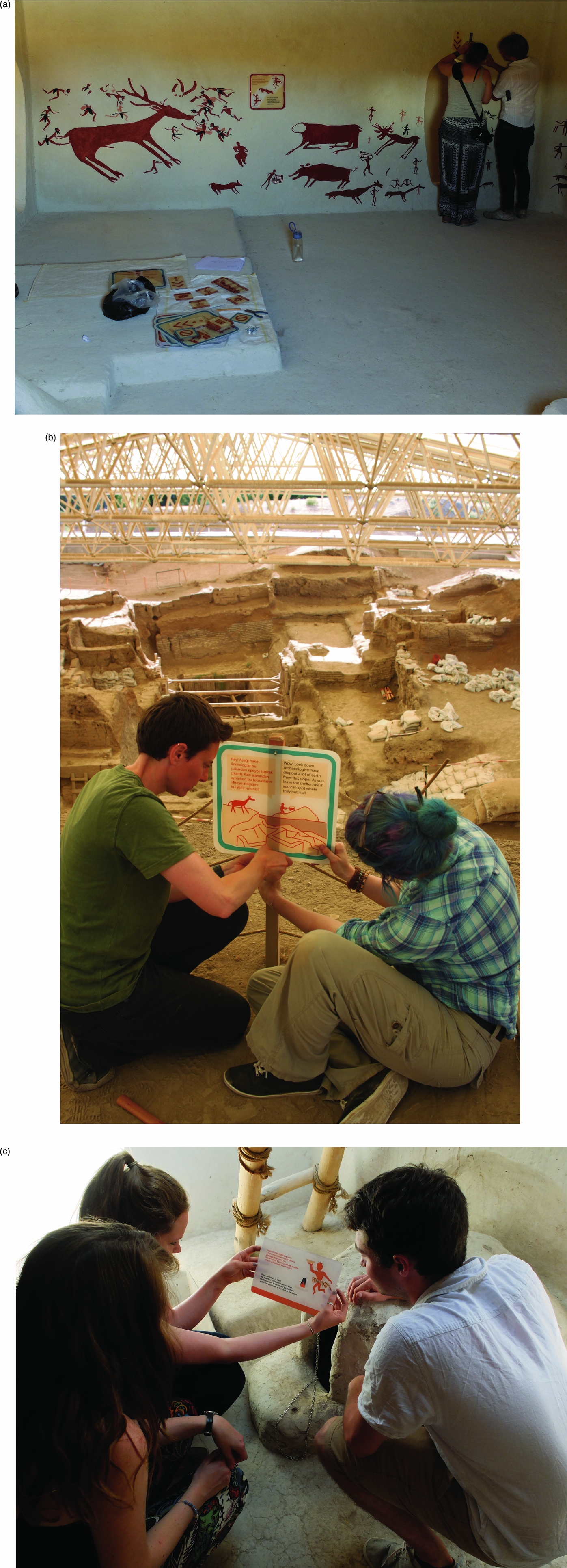

Here I briefly introduce the practice of heritage interpretation, its history, and its possibilities for archaeological knowledge creation. I do this in order to suggest that our typical models of archaeological practice (not to mention cultural heritage management) today are seemingly ignorant of the potential of the heritage interpretation tool kit. As a result, heritage interpreters are trapped at the end of a linear knowledge production chain, almost always brought in after the fact to remediate and broadcast the interpretations of archaeologists and other specialists. Our applications of digital technologies are arguably worsening the situation, further curtailing our understanding of what it means to interpret the archaeological record. Using the Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük as an example, I discuss the strengths and weaknesses of my team's application of creative story-authoring and body-storming techniques among Çatalhöyük's specialists during two consecutive seasons of active archaeological fieldwork. The results have been mixed, but they represent a move toward countering the typical, superficial involvement of heritage interpreters at the trowel's edge (Figure 1). With reference to successful interventions elsewhere, I ultimately posit that this insertion of interpretation into primary field practice has the potential to transform the process and impact of archaeology overall.

FIGURE 1. Heritage interpreters at work in various capacities at the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Çatalhöyük, Turkey: (a; this page) inside one of the recently installed replica houses, August 2017 (photo courtesy of Meghan Dennis); (b; see p. 4) at the top of the South Area, August 2016 (photo courtesy of Dena Tasse-Winter); (c; see p. 5) inside the experimental house, August 2015 (photo courtesy of Ian Kirkpatrick).

WHAT IS HERITAGE INTERPRETATION?

Broadly defined as a means for heightening one's experience of archaeological, natural, and culturally historic sites, heritage interpretation is a vast enterprise in the contemporary world. Its outputs include everything from souvenirs to videos to 3-D models of the heritage environment, although they are most usually appreciated as signage, tour guides, exhibitionary spaces including visitors’ centers and heritage trails, guidebooks, brochures, and associated printed touristic paraphernalia. The interpretative process is variously governed by local authorities, national agencies (governmental and professional), and private parties, with added layers of standardization offered by international charters (e.g., the International Council on Monuments and Sites' Ename Charter) and best practice publications (e.g., Emberson and Veverka Reference Emberson and Veverka2007). Indeed, the levels of bureaucracy now involved in heritage interpretation suggest a rather regimented, fixed system of practice delivered by curators, educators, and other specialists distinct from those responsible for primary research and data collection about heritage itself (after Staiff Reference Staiff2014).

Freeman Tilden's (Reference Tilden1957) definition and six principles of interpretation (Table 1) are generally regarded as the birthing grounds of modern cultural and natural heritage interpretation, despite the fact that its history stretches back much further and its dimensions have shifted over time and space (see Styles Reference Styles2016 for a brief historical background). The concept has been exploited across many fields, including tourism, natural and cultural heritage management, museums, and education, among others, yet mutually informed learning and crossovers between these fields are not especially apparent (Deufel Reference Deufel2016 also makes this argument specifically in regards to the German context). Underlying most such applications, however, is a focus on communication of knowledge to, and education of, the nonspecialist public (Staiff Reference Staiff2014). Moscardo effectively captures this focus in her review of the practice: “Heritage interpretation is defined as persuasive communication activities, such as guided tours, brochures and information provided on signs and in exhibitions, aimed at presenting and explaining aspects of the natural and cultural heritage of a tourist destination to visitors” (Reference Moscardo2014:462).

TABLE 1. Freeman Tilden's Well-Loved, Oft-Repeated, but Problematic Definition and Principles of Heritage Interpretation.

Source: Tilden Reference Tilden1957.

It is this one-sided, rather facile concern for the “general public” that sits at the heart of my ensuing argument. The International Council on Monuments and Sites' Ename Charter refers to heritage interpretation as “the full range of potential activities intended to heighten public awareness and enhance understanding of cultural heritage sites” (2008:3; emphasis mine). Other definitions are not dissimilar, speaking of “a set of professional practices intended to convey meanings about objects or places of heritage to visitors or users” (West and McKellar Reference West, McKellar and West2010:166; emphasis mine). Jimson describes “the function of the interpreter” as “to mediate between the curator, concept developer, or institutional knowledge holder, and the visitor. The interpreter translates museum meanings to audiences” (Reference Jimson and McCarthy2015:533; emphases mine). Even where attempts have been made to push the boundaries of the concept, for instance, Silberman's nuanced description of “the constellation of communicative techniques that attempt to convey the public values, significance, and meanings of a heritage site, object, or tradition” (Reference Silberman, Albert, Bernecker and Rudolff2013:21; emphases mine), the core of the practice still seems presumed to be for nonspecialist publics in the first instance. This narrowly conceived focus, I contend, is dangerous because it leaves us blind to the true power of heritage interpretation.

While it is beyond the scope of this article to delve into its other diverse critiques, the traditions of heritage interpretation are seen as problematic by many: unverifiable and poorly evaluated; reinforcing of authorized discourses; generally unable to account for conflicting perspectives; technocratic, undemocratic, and hierarchical (e.g., see assessments in Deufel Reference Deufel2016, Reference Deufel2017; Moscardo Reference Moscardo2014; Silberman Reference Silberman, Albert, Bernecker and Rudolff2013; Staiff Reference Staiff2014; Styles Reference Styles2016). Yet the critics themselves, as per the many standardizing bodies and bureaucracies implicated in interpretative practice, still recognize its potential and urgency, not only for heritage but for society at large. As I see it, at the heart of the argument for heritage interpretation is a recognition of its promise as a mediator and facilitator—a means to enable reflection, critical thinking, empowerment, and other forms of positive personal/cultural growth and change. Per my discussion below, heritage interpreters themselves—working in direct and equal relationship with other nonspecialist and specialist communities—are key to realizing such promise. However, the dominant workflows, methods, and ideologies at play today in the fields of both archaeology and heritage practice are, I believe, hostile to its realization. As I argue, such hostility is perhaps partially bred from the interpretative media that archaeologists themselves generate and the typical interpretative processes that they follow.

THE SOUL OF THE DISCIPLINE: WHERE SITS HERITAGE INTERPRETATION IN RELATION TO ARCHAEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION?

For centuries archaeologists, antiquarians, and other interested intellectuals have been producing heritage interpretative resources alongside—or interchangeable with—research publications (e.g., see, among many descriptions, Evans Reference Evans, Schlanger and Nordbladh2008; Garstki Reference Garstki2016; Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey2015; Moser Reference Moser2014; Moshenska and Schadla-Hall Reference Moshenska and Schadla-Hall2011; Perry Reference Perry2017a; Thornton Reference Thornton2015). In these cases, varied genres of presentation—for example, seventeenth-century paper museums; nineteenth-century models and dioramas; twentieth-century excavation films, television, and exhibitions; twenty-first-century 3-D reconstructions and prints; and so on—are deployed simultaneously as intellectual tools and entertainment or aesthetic devices. This dual nature is critical to their productivity: they are thinking apparatuses, meeting spaces for diverse audiences, generators of conversation, inspiration, and connectivity to both the past and present. When situated within heritage landscapes, as part of touristic or visitor offerings, their transformative potential is arguably particularly pronounced. Such landscapes tend to be highly curated, supported by major interpretative infrastructure (i.e., the facilities, architecture, and other mechanisms that enable access to the heritage and its presentation [after International Council on Monuments and Sites 2008]), and they have been linked to significant impacts on their audiences. They may be engenderers of wonder, resonance, or provocation, which in turn can create real attachment to and appreciation of the heritage sites and their exhibits (Greenblatt Reference Greenblatt1990; Poria et al. Reference Poria, Butler and Airey2003; Tilden Reference Tilden1957). When audiences connect with sites individually or intimately, lasting remembrance (Park and Santos Reference Park and Santos2017), personal restoration or transformation (Packer and Bond Reference Packer and Bond2010; Smith Reference Smith, Gosselin and Livingstone2015), and care for protecting and preserving the heritage record can manifest (McDonald Reference McDonald2011). A variety of research links heritage and cultural sites to so-called numinous experiences (e.g., Cameron and Gatewood Reference Cameron and Gatewood2000; Latham Reference Latham2013), a kind of inexpressible, almost spiritual form of engagement—a “meaningful, transcendent experience that results in a deep connection with the past” (Wood and Latham Reference Wood and Latham2014:85). What is critical is that interpretation itself is essential to such connectivity. As Ham and Weiler's (Reference Ham and Weiler2007) analyses indicate, the expressive aspects of a site (e.g., maps, signs, brochures, other presentational media and approaches) are crucial to satisfying experiences at the site. It is they that prove significantly more impactful on audiences than other infrastructural provisions (e.g., toilets, benches, cafés, etc.) because they, in unique fashion, influence “directly on the psychological experience of visitors” (Ham and Weiler Reference Ham and Weiler2007:20).

Of course, one might argue that touristic interpretative efforts are different and far removed from archaeological field practice, and indeed the extent to which heritage interpretation ideals have come to directly inform the archaeological research endeavor is a matter for debate. Historical analyses of archaeologists who might today be conceived as master interpreters, for example, Kathleen Kenyon or Mortimer Wheeler, suggest that the precise interplay between such interpretation and primary fieldwork activity has yet to be fully interrogated. Moshenska's description of Wheeler's work at the site of Maiden Castle in the early twentieth century suggests that “public presentation of the project, what I have called Wheeler's ‘theatre of the past,’ was in many respects as innovative and logistically ambitious as the fieldwork itself” (Reference Moshenska and González-Ruibal2013:217). Wheeler, indeed, is explicit that these activities feed back on themselves:

I would particularly stress the value to the archaeologist himself of speaking to and writing for the General Public. . . . The danger of . . . jargon . . . is not merely that it alienates the ordinary educated man but that it is a boomerang liable to fly back and knock the sense out of its users [Reference Wheeler1954:193–194].

He goes on to quote from the historian G. M. Trevelyan, saying that the failure among specialists to produce broadly accessible interpretations “has not only done much to divorce history from the outside public, but has diminished its humanizing power over its own devotees in school and university” (Wheeler Reference Wheeler1954:195).

It is this matter of “humanizing power” that is of special interest to me. The editors of Current Archaeology once bemoaned the fact that “archaeologists have no soul” (Selkirk and Selkirk Reference Selkirk and Selkirk1973:163; see a longer exploration of the matter in Perry Reference Perry, Chapman and Wylie2015). I understand Petersson to be hinting at this same issue—and its problematic persistence—when she writes that “archaeologists sometimes actually seem to have a serious fear to address the human aspects of the past.” Petersson proceeds to implicitly attribute the problem to a “fear of losing analytical gaze” (Reference Petersson, Larsson and Huvila2018); I would extend her argument by suggesting that such fear is born of a general and endemic lack of understanding of, and competence in, interpretation writ large (i.e., for any audience, whether specialist or not).Footnote 1

In other words, I believe that our typical disciplinary workflows invite soullessness. This is because the art of interpreting the archaeological record, in my experience, is variously relegated to a small box at the end of a context sheet; trivialized in our training programs by a concern, in the first instance, for mastering rote excavation method; devalued by typical commercial practice, where rapid data collection, and uninspired documentation in inaccessible gray reports, efface real engagement with the subject matter; and aggravated by the unrelenting trend for even the most “reflexive” of academic projects to release their cornerstone interpretative work as traditional single-authored books by the project director. The emergence of applied digital field methods (e.g., digital recording and data capture; digital processing, analysis, and publication: see Averett et al. Reference Averett, Gordon and Counts2016 for an excellent overview of the subject) has arguably worsened—indeed retrogressed—the predicament, further compartmentalizing the interpretative process or obfuscating it altogether (I will explore this point in detail below).

The labor of those who typically add the soul back into the archaeological record (for instance, illustrators, photographers, graphic modelers and artists, curators, writers, and other creatives) is often outsourced, underpaid, belittled, sidelined, and uncredited. Gardner's (Reference Gardner2017) critique of this pervasive state of affairs in relation to archaeological illustration echoes the experience of many creative practitioners. As she poignantly puts it, not only do archaeologists appropriate creative work as their own, rarely listing the artists as equal contributing authors on publications, but even more gallingly, “there is an often underlying patronizing assumption, which has been stated to my face that my role is ‘just to make it look pretty’” (Reference Gardner2017).Footnote 2

Rather tellingly, Farid's critical appraisal of Çatalhöyük's reflexive approach suggests that it was grounded in five methods, the first four of which are inward-facing and now relatively commonplace matters of procedure or documentation:

1. priority tours and structured team discussion;

2. purpose-designed sampling strategies;

3. conventional and video diaries that document practice;

4. shared-access data for all members;

5. engagement with the wider context of the project, including local and regional as well as national and global interests [Reference Farid, Chapman and Wylie2015:64].

The fifth of these methods, arguably the most vague of them all but the one whose “humanizing power” is most obvious, clearly pertains to broad issues of interpretation yet is not subject to discussion alongside the others. Instead, its impact is severed from the primary fieldwork context, as though it has little relation to it or can be dealt with independently.Footnote 3 My argument is that this severing of human interests—the soul of archaeology—from archaeology itself is primarily a consequence of, first, poor or no skill among archaeologists in archaeological and heritage interpretation; second, its lowly placement at the end of the standard work pipeline; and third, an insidious lack of appreciation of the affordances of the heritage interpretation tool kit overall.

INTERPRETATIVE CREATIVITY AS CRUCIAL TO UNDERSTANDING THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD

Nearly 70 years ago now, Jacquetta Hawkes called for archaeologists to “not forget the problems of popular diffusion in planning our research” (in Wheeler Reference Wheeler1954:192). While one might suggest that it is common today in some contexts to have so-called popular diffusion factored into the professional pipeline, the relevance of creative mediation to the entire enterprise of archaeology—its research questions, ontologies, and general epistemological potential—seems barely understood. The irony here is that archaeologists regularly experiment with creative interpretation, productively collaborate with creative practitioners, and laud the intellectual and other benefits of such creative work. In 2017 alone, we saw such discussion in relation to geophysics and imaging (Ferraby Reference Ferraby2017), heritage and gaming (Copplestone and Dunne Reference Copplestone and Dunne2017), heritage and auralization (Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Shelley, Foteinou, Brereton and Daffern2017), excavation and drawing (Gant and Reilly Reference Gant and Reilly2017), diverse practices of archaeology connected to art (Bailey Reference Bailey2017), and mapping and various forms of painting, installation, and performance (Pálsson and Aldred Reference Pálsson and Aldred2017). Several such pieces are published in a full issue of the journal Internet Archaeology on the topic “Digital Creativity in Archaeology,” wherein the editors plainly aim to spotlight “the creative impulses that permeate, underpin and drive the continued development of even the most empirical digital archaeologies” (Beale and Reilly Reference Beale and Reilly2017). In the same year, an issue of the Journal of Contemporary Archaeology was published on the topic “Beyond Art/Archaeology,” exploring “the possibilities for creatively engaged contemporary archaeologies” (Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Lee, Frederick and White2017:122); and an entire periodical, Epoiesen: A Journal for Creative Engagement in History and Archaeology, was launched, seeking “to document and valorize the scholarly creativity that underpins our representations of the past” (https://epoiesen.library.carleton.ca/about/).

These are but a few of the multitude of arguments—some playful, some more earnest, some suggestive, some more convincing—for the transformative potential of creative work in relation to archaeological reasoning and knowledge formation. Such arguments are complemented by critical commentaries from creative producers themselves (e.g., Dunn Reference Dunn2012; Swogger Reference Swogger and Hodder2000), who explicitly trace the interrelationship between their practice and idea generation/testing in archaeology. One might be tempted to reduce these claims to novel developments in the discipline if not for the century-long (at least) body of evidence testifying to artistry, imagination, performance, playfulness, and enchantment as facilitators of the emergence and refinement of traditional archaeological method and theory (e.g., see contributions in Smiles and Moser Reference Smiles and Moser2005; also Wickstead Reference Wickstead2017, among others). The mid-twentieth-century archaeological reconstruction artist Alan Sorrell, for instance, is among those to outline this contribution of his craftwork to empirical archaeological practice, which is of special significance given his influence at a key point in the institutionalization of the discipline (see Perry and Johnson Reference Perry and Johnson2014).

As I see it, individuals like Sorrell are interpreters of the heritage record, interacting with other specialists, as well as nonspecialists, in the negotiation of our various understandings of the past. They are effectively mediators, enabling change in the way archaeologists think, not least in the way others think. In this fashion, they sit at the core of the entire enterprise of archaeology. Moreover, they literally parallel the definition of heritage interpretation itself, which, according to Jimson, “can open up worlds and meanings for people. It can excite, inspire, and motivate. It can galvanize perception, provoke action, and shift attitudes” (Reference Jimson and McCarthy2015:529). Ham, summarizing the ideas of Freeman Tilden, contends that interpreters are “attempting to provoke them [people] to deep thought” (Reference Ham2009:51). As such, the specific skill set of the interpreter might be variable (focused on visual or audio expertise, storytelling or performance, haptic or other mediation, or curation of all of the above), but it will always depend fundamentally on an expert capacity to mediate, to facilitate, to interrelate.

As Ham goes on,

When interpretation provokes a person to think, it causes an elaboration process that creates or otherwise impacts understanding, generating a sort of internal conversation in the person's mind that, in turn, produces new beliefs or causes existing beliefs either to be reinforced or changed [Reference Ham2009:52].

It is here where I think we can see the crux of the link between heritage interpretation and archaeological interpretation more particularly. González-Ruibal, outlining the nature of twenty-first-century critical archaeology, insists that “it is only when we are able to imagine another world that we can actually start to change the present one” (Reference González-Ruibal2012:158). Whatever world (past, present, or future) that we are trying to envisage or impact, being able to imagine its manifestations is key. This is where (heritage) interpretation fits in: as facilitators of our imaginations, its specialists mediate between ideas, people, data, materials, and so on in conceptualizing past worlds.

We are held back, however, by the discipline of heritage interpretation itself, which, as previously described, typically sees its role as single-sided, that is, visitor-facing. Herein heritage interpreters may be brought in to mediate between the expert and the nonexpert public or even to mediate between one nonexpert public and other nonexpert publics. But to see heritage interpreters recognized as meaningful mediators between experts themselves—in expert-to-expert dialogue—is seemingly entirely unconsidered.

This situation is compounded by long-standing problems with archaeological interpretation more generally and its integration with the proficiencies of creative interpreters (as noted above). For if we have few or mediocre skills in interpretation, if we marginalize its relevance, if we demean and undervalue its diverse practitioners, if we continue to produce endless reflections on art and archaeology or creativity and archaeology without real synthesis or systemic change to our standard textbooks, curricula, field schools, excavation manuals, commercial workflows, and so on (i.e., the architecture of knowledge-making in the discipline), then the profession of archaeology will forever remain stunted, unimaginative, and, so, trivial in relation to the world at large.

THE PROBLEMATIC INTERPRETATIVE ROLE OF EMERGING ARCHAEOLOGICAL METHODS

Silberman hints at the consequences of eclipsing imagination in interpretation when he writes,

Public interpretation is about narrative, about stories with beginnings, middles and ends. And as long as at least some specialists within the discipline do not dedicate themselves to learning the skills of effective communication and story construction as a respected, not peripheral, part of the work of archaeology, film crews and visiting journalists—with interests in sensationalistic angles—will do it themselves [Reference Silberman, Clark and Matthews2003:16].Footnote 4

I am concerned about the implicit assumption here that “public” refers only to nonarchaeologists, and I would extend the argument further to demand that all practitioners have at least a basic capacity in interpretation; nevertheless, Silberman's point is a pressing one. If our investigations of the past are soulless, others with more compelling narratives (or, indeed, with any narrative at all that inserts common human desires and values into the story line) will come to fill the void. Learning and practicing the skills of richly interpreting—and fearlessly reinterpreting—the archaeological record (from the very outset of our training schemes and as part of our core field practice) is crucial for “humanizing” our engagements with audiences, including humanizing our own internal disciplinary dialogues. The latter point deserves extended consideration, which is beyond the scope of this article. However, I see it as one of the few means toward truly democratizing the profession and escaping the common predicament wherein big interpretations of the past are hoarded by individual, established academics, rather than by teams, commercial units, community groups, field school enrollees, and all of the others doing the vast majority of archaeological work today (see Caraher's Reference Caraher, Averett, Gordon and Counts2016 excellent critique of the ever-present hierarchies in archaeology for more on the matter; also see Jackson et al.’s Reference Jackson, Motz and Brown2016 digital recording system, which is seemingly unique in forcing extended and collective consideration at the trowel's edge of emerging, high-level interpretation).

This is why I think that we need to be especially cautious of methodologies that aim to expedite and collapse the interpretative process, that make it even more inaccessible through expensive equipment and bespoke or proprietary software, that drive it even further away from the primary fieldwork context by demanding extensive laboratory-based postprocessing, or that heighten divisions between practitioners by further lodging control of and power over the data with an exclusive number of specialists. These same methods usually also claim an objectivity and efficiency that imply they are beyond critique. Here I refer, in particular, to many applied digital field methodologies, whose problematic tendencies are thoroughly reviewed in various contributions to Averett and colleagues (Reference Averett, Gordon and Counts2016; see especially Caraher Reference Caraher, Averett, Gordon and Counts2016; Gordon et al. Reference Gordon, Averett, Counts, Averett, Gordon and Counts2016; Kansa 2016; Rabinowitz Reference Rabinowitz, Averett, Gordon and Counts2016).

Digital recording and modeling in their most troublesome, early “cyberarchaeology” incarnations have been particularly culpable in excising soulful interaction from the primary fieldwork context. Indeed, their focus on precision, accuracy, speed, objectivity, and allegedly “unprejudiced” representation, and their claims to transparency, supposed “virtual” reversibility, and total forms of recording, sit in direct opposition to the expressive, volatile, playful, purposefully loose and partial nature of interpretative work more broadly (as previously described). Rabinowitz makes exactly this point, reminding us of Silberman's argument above:

Machines can collect data, and they can begin to integrate them into the contextual systems that we think of as information, but they cannot perform the leap of informed imagination that enables the human archaeologist to propose explanations for why and how a stratigraphic deposit was formed, and they cannot (yet) tell the stories that archaeologists must create to explain the history of a site [2016:504; emphases mine].

Disconcertingly, the worst digital projects have cut storytellers out of the process altogether, seemingly presuming that imagination and expressive interpretation are already inherent in them. Captured by visual and other technologies, the resulting (usually 3-D) models of the archaeological record that are produced from these projects are often popped straight into exhibitions, on websites, in mobile apps, and in articles, magazines, and other media, with little to no critical intervention by creative specialists—let alone by their own makers (although there is now a growing number of exceptions, e.g., see Carter Reference Carter2017, among others). Stobiecka's seminal critique of cyberarchaeology highlights the problem behind such actions, arguing that they betray a naive but long-lived disciplinary striving for objectivity, with archaeologists seeking to be “liberated from [the] lowly matter” (Reference Stobiecka2018) that characterizes their typical dataset.

Such escapism is overt in the very language that cyberarchaeologists have deployed when describing their approach. For instance, Forte and colleagues suggest that their work facilitates “a sort of time travel back and forward” (Reference Forte, Dell'Unto, Issavi, Onsurez and Lercari2012:373). Levy and colleagues speak of their work as about capturing the entirety of the excavation experience, therein enabling “anyone to see the excavation of the site as the field archaeologist saw it from start to finish” (Reference Levy, Smith, Najjar, DeFanti, Kuester and Lin2012:23). The underlying assumption is an essentialist one that eclipses interpretation altogether, and it is what I understand Silberman to mean when he speaks of the discourse of “impossible restorative nostalgia” (Reference Silberman, Albert, Bernecker and Rudolff2013:29).

While the potential that comes with nuanced recording and 3-D modeling of the archaeological record is tremendous, when done poorly, as Gordon and colleagues (Reference Gordon, Averett, Counts, Averett, Gordon and Counts2016:19) aptly summarize, these methods (and, I add, any method applied uncritically, whether digital or not) often fragment the data, widen the interpretative gap, drown us in what Caraher calls “a virtually meaningless mass of encoded data” (Reference Gordon, Averett, Counts, Averett, Gordon and Counts2016:433), and eliminate somatic forms of knowledge creation through hurrying, denying, and/or postponing hands-on encounters with the primary material record. In my experience, it is easier than not to fall prey to such problems—but why? And how can we constructively respond to this predicament?

In answer, I feel that we need to interrogate the fundamentals of our interpretative approach. Some practitioners may mistakenly assume that technology itself can do interpretation. For some, interpretation may get lost among all the other complexities of technological deployment and field practice. But, as I see it, the problem is grounded in our narrow and perniciously undeveloped understanding of and capacity for doing interpretation. It is heartening to see a variety of efforts to introduce reflexivity into digital projects (e.g., Lercari Reference Lercari2017), even if one might rightly argue that they should have been reflexive from their inception. I contend, however, that little will change until we take seriously the expertise of heritage interpreters (here I include anyone with refined skills in mediating between archaeological ideas, people, and materials—which may include archaeologists themselves, illustrators and other media makers, technologists, curators, and heritage professionals, all trained in interpretative practice).

INTEGRATING THE HERITAGE INTERPRETER'S TOOL KIT INTO THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL WORKFLOW

Revising the standard archaeological workflow to consistently build and nurture rich, humanizing interpretations of the past is an urgency for the discipline today. Without such change, every new method and technology added to our tool kit is likely to lead us further down a dead end; for these applications are being introduced into a model of practice that has no means to adequately negotiate their interpretative implications. As Watterson shows, technologies can blatantly “mute” our engagements with the archaeological record, “effectively distancing the field worker from their material” (Reference Watterson2014:100–101). Skilled interpretation, as I see it, is the mediator between all these agents (i.e., people, technologies, materials, etc.), hence to have interpreters missing from, or voiceless at, the trowel's edge—at that crucial moment when inspiration and meaning-making are taking off—is to suffocate archaeology overall.

Watterson herself argues for the adoption of a mixed-methods creative and experimental approach, wherein archaeologists regularly “step away from their scanners, cameras and other recording devices, and simply dwell . . . to inhabit and interpret the otherwise passive data gathered by cameras and scanners and reanimate this alongside embodied encounters with sites and landscapes” (Reference Watterson2014:100).Footnote 5 The messy, creative workflow associated with Watterson's process is understood as a productive and unpredictable one, and she likens it to what Maxwell and Hadley (Reference Maxwell and Hadley2011) call “artful integration.” As I read it, artful integration is aligned with, if not identical to, my own arguments here, centered upon “positive ways of integrating . . . creative work into the archaeological discourse” (Maxwell and Hadley Reference Maxwell and Hadley2011). However, it seems telling that, almost a decade after the term was coined, the driving questions behind the realization of artful integration remain unanswered; per Maxwell and Hadley,

How should this relationship between art and creative work be practically arranged in the field, in the office and in the museum? Should artful integration be considered its own discipline, or is its strength in its un-disciplining? . . .

. . . How can the varied creative methodologies . . . be critically integrated into the archaeological discourse and recognised as a valuable contribution? [Reference Maxwell and Hadley2011].

Indeed, arguably Thomas and colleagues grapple with the same issues years later when they speak of the theory and practice of creative archaeologies:

[Is it] still valid to talk of art/archaeology as an interdisciplinary area, or does this term itself merely perpetuate a false dichotomy? Is it instead more valid to think of new forms of creative practice, which we might term as neither art, nor archaeology, but something else? [Reference Thomas, Lee, White and Frederick2015; cf. Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Lee, Frederick and White2017].

More recently, Bailey (Reference Bailey2017) proposes a three-step process of “art/archaeology,” which seems a cognate of Maxwell and Hadley's artful integration (although it is notable that Bailey does not acknowledge the parallels here or any other recent disciplinary work on the subject).

While Thomas and colleagues (Reference Thomas, Lee, White and Frederick2015) speak hopefully of making such creative archaeologies “the norm,” few, if any, seem to have embedded themselves in the usual archaeological workflow. This is because models of practice may be scarce, one-off, purposefully irreproducible, illegible, or overly esoteric (not to mention produced in a vacuum where many seem unaware of others’ comparable efforts). While I appreciate that systematizing creativity could lead to homogenized, insipid outcomes that achieve the opposite of creative inspiration, this is not my aim. Rather, I seek to embed the facilitation of creative interpretation into common archaeological practice. Here we can draw on user-centered, codesign, and participatory design methodologies to guide the approach. Therein, varying forms of embodied, personal, and collaborative expression—for example, oral, written, and visual brainstorming; speak-aloud protocols; drawing; modeling; crafting and other forms of making; performance; prototyping; physical enactment; play; and social interaction—are deployed among groups of individuals to promote thinking and meaning-making, concept exploration, heightened awareness, and the development of sympathetically designed outputs (e.g., see applications both within and beyond the cultural heritage sector in Fredheim Reference Fredheim2017; Malinverni and Pares Reference Malinverni and Pares2014; Pujol et al. Reference Pujol, Roussou, Poulou, Balet, Vayanou and Ioannidis2012; Schaper and Pares Reference Schaper and Pares2016).

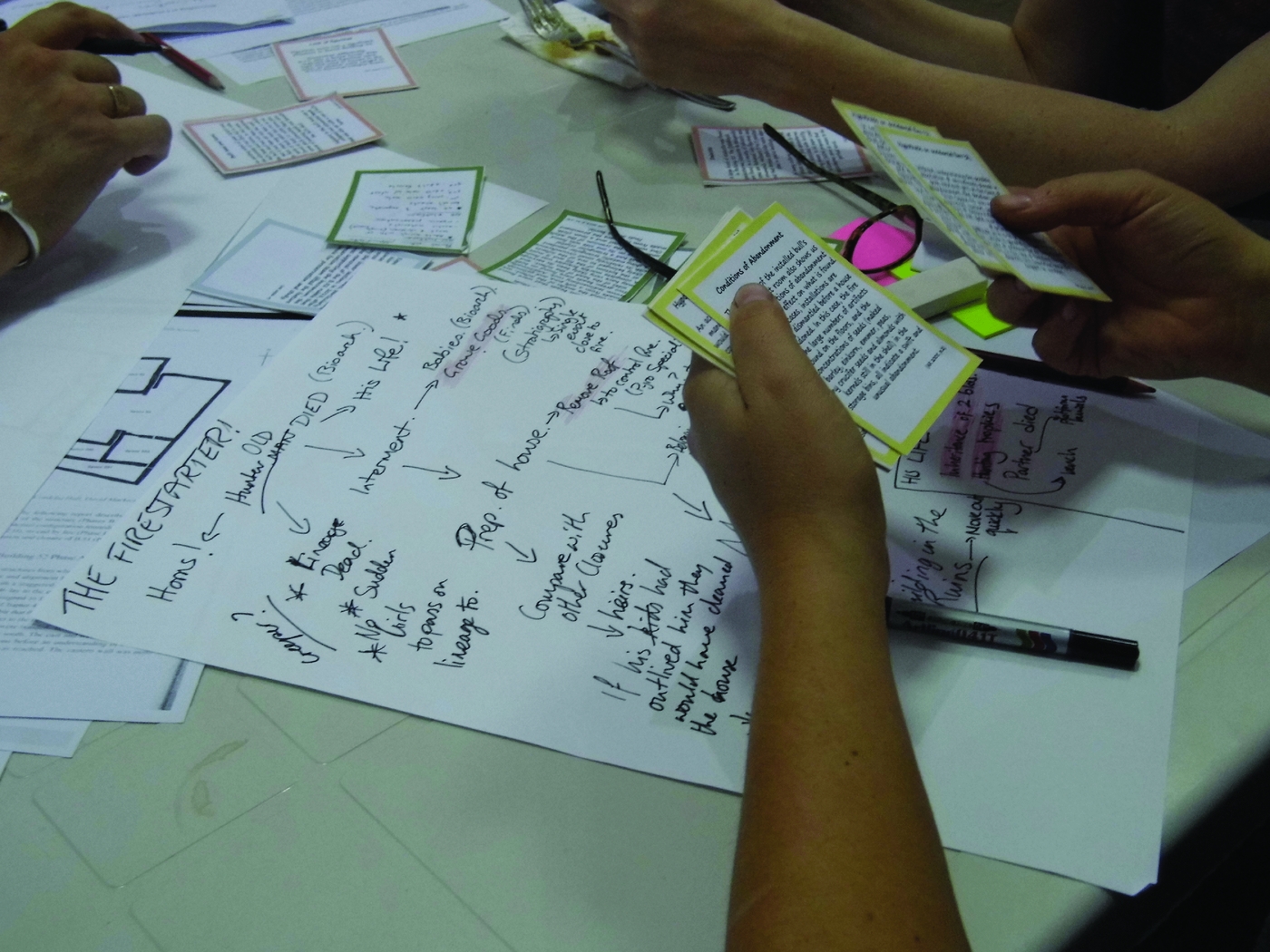

As part of experimental efforts to develop engaging mobile applications for visitors to remote heritage sites, my interpretation-focused field team at Çatalhöyük, working in collaboration with the European Commission–funded CHESS project, implemented such participatory design methods during two consecutive excavation seasons (summer 2014, summer 2015). In 2014, we used a collaborative story-authoring methodology with Çatalhöyük's on-site specialists to script stories about a particular Neolithic building (Building 52), which would later be adapted into the content for a prototype mobile app for visitors. Our approach and results are presented elsewhere (Roussou et al. Reference Roussou, Pujol, Katifori, Perry and Vayanou2015), and they have been elaborated through workshops and events hosted at different sites and with different audiences around Europe. Çatalhöyük's specialists were split into groups, predefined by our team to ensure gender and age balance, and representativeness of expertise. Over two hours, these groups reviewed the variety of current and historical data from Building 52 (presented on cards that clustered data by theme, e.g., human remains, special artifacts, hypotheses about the destruction of the building, etc.) and then defined the audience for their story and agreed on certain parameters (e.g., the story's genre, narrator, etc.). From there, they variously brainstormed ideas on paper and sticky notes, storyboarded, scripted, and then presented their story to the full group (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. In-progress story-authoring session at Çatalhöyük, Turkey, including thematic cards and brainstorming sheets, July 2014 (photo courtesy of Angeliki Chrysanthi).

Of crucial interest to me here is the impact of this design method on the specialists themselves (rather than on those who experienced the final story on the prototype app). As discussed in Roussou and colleagues (Reference Roussou, Pujol, Katifori, Perry and Vayanou2015), Çatalhöyük's specialists reported that the exercise led to conceptual debate, liberating forms of idea generation and presentation, and heightened reflectivity about the nature of the evidence and its relation to their research. One archaeologist put it as such:

Working through a narrative makes you realize what we don't know. . . . It makes you think about experience a lot more. . . . People were saying: “Wait, we don't know that. Do we know that? What do we know? How do we know it?” It just makes you ask those fundamental questions, and it changes the focus of research in what I think is a really positive way. Rather than saying: what materials do we have and what do they tell us . . . it makes you draw it together [quoted in Roussou et al. Reference Roussou, Pujol, Katifori, Perry and Vayanou2015; italics removed].

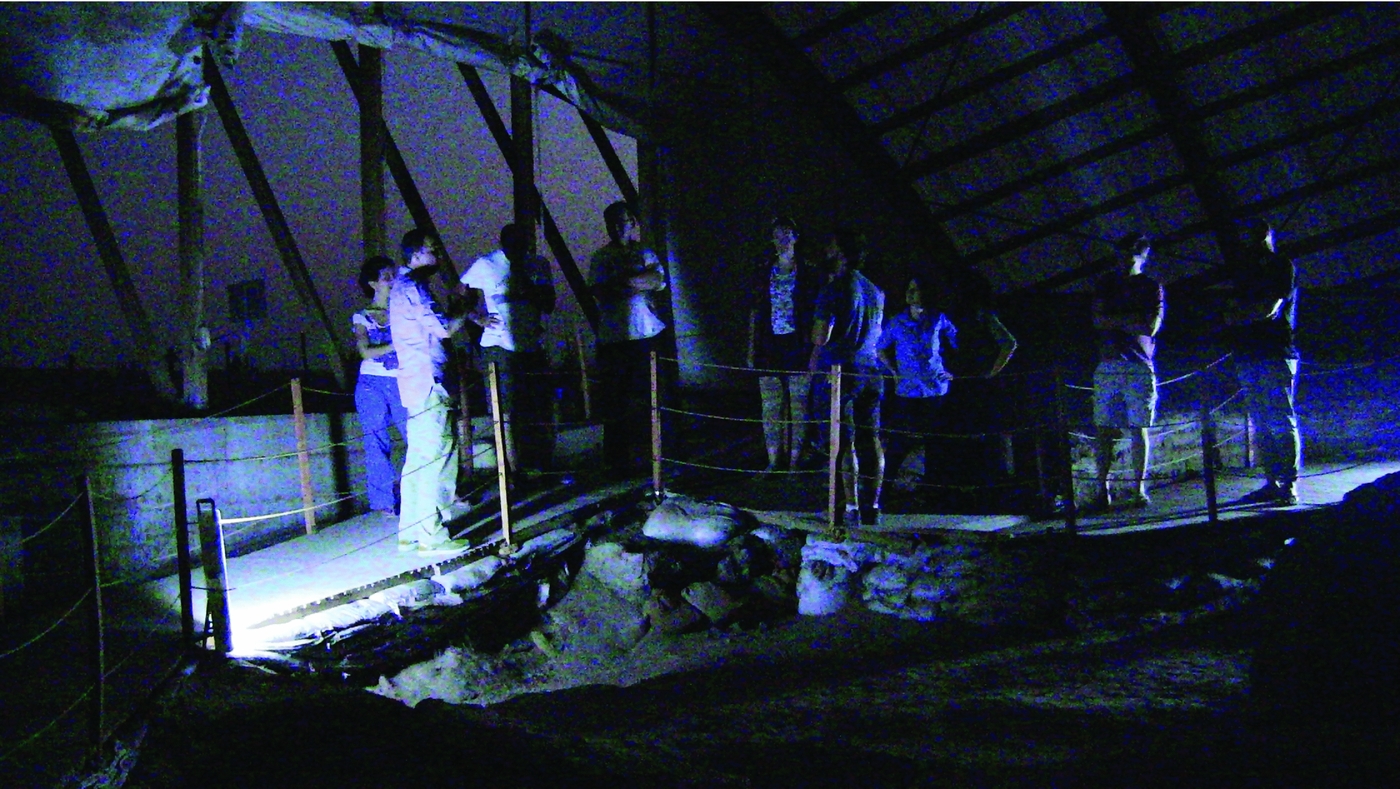

Inspired by this feedback and by calls from some to see such methods integrated into usual practice at Çatalhöyük, the following year (2015) we experimented with a “body-storming” activity among a group of 20 specialists (Figure 3). The body-storming approach, as we applied it, employs body awareness strategies (e.g., Malinverni and Pares Reference Malinverni and Pares2014; Schaper and Pares Reference Schaper and Pares2016) to prompt participants to explore spaces and concepts through physical enactment. Our interest was in how the spirit of Neolithic Çatalhöyük (what we called “Çatalhöyükness”) could be interpreted for visiting audiences and whether body-storming techniques might assist in not only creatively presenting Çatalhöyükness but also physically engaging people with the material culture. We split the group into two, asked the groups to brainstorm about what they believed typified Çatalhöyükian ways of life, and then facilitated theatrical performances of their ideas on the site itself, following a body warm-up session wherein a sequence of movements and actions was used to draw people's attention to their physical selves and their bodies in space. A debrief session after the enactments, plus subsequent interviews with Çatalhöyük's specialists, suggested that the body-storming session was not effective in the form we delivered it.Footnote 6 However, various individuals appreciated the potential behind it, speaking of its productive exploration of knowledge through nondiscursive means, its forcing of specialists to slow down their process and spend time with the material, and its possibility for exposing assumptions and biases among archaeologists and hence offering the chance to reflect on one's professional practice.

FIGURE 3. Group of archaeological specialists and heritage interpreters gathering in the North Area of Çatalhöyük at nightfall for a facilitated “body-storming” session, July 2015 (photo courtesy of Vassilis Kourtis).

This activity, akin to our story-authoring session in 2014, was fundamentally grounded in a concern for storytelling (herein through the body), deployed during the fieldwork season itself, on the edge of the excavation unit, with the full range of site specialists working together in its realization. While our aim was originally to design novel visitor resources based on the most up-to-date specialist data, the most powerful outcome was, in fact, confirmation of what Holtorf (Reference Holtorf2010), among others, has long argued. As Bernbeck, quoting Holtorf, writes, “Story-telling . . . [is] a mode of exploration and a kind of model-making that allows us to create comparative frameworks for evaluating different theories” (Reference Bernbeck2013:26). Bernbeck sums up the point by arguing that “creative archaeological narratives can lead to theoretical insights” (Reference Bernbeck2013:26). It is in the enabling of such narratives among archaeological specialists, I contend, that heritage interpreters hold untapped potential.

WHAT'S NEXT FOR INTERPRETATION IN ARCHAEOLOGY?

In the Çatalhöyük examples described above our team of heritage interpreters led each of the creative participatory design sessions with specialists. Yet others (excavators, illustrators, photographers, etc.) might equally take up this role,Footnote 7 as has been done at Çatalhöyük before (e.g., Leibhammer Reference Leibhammer2001; Swogger Reference Swogger and Hodder2000) and as is done elsewhere (e.g., Dunn Reference Dunn2012). The approach is not unlike the interpretative model applied in the Sedgeford Historical and Archaeological Research Project, wherein supervisors acted as facilitators of interpretation among their volunteer diggers, rather than hoarding the interpretations themselves or isolating them from less experienced individuals (Davies and Hoggett Reference Davies and Hoggett2001; also Faulkner Reference Faulkner2000).Footnote 8 Closer to my vision, the recent award-winning Must Farm excavation (http://www.mustfarm.com) employed two outreach officers, both of whom also spent 50% of their time in the position of excavator, thereby ensuring an inseparable link between the primary site interpretations and their circulation beyond the field (Wakefield Reference Wakefield2018). Christopher Wakefield (personal communication 2017) himself is clear that we need to better equip and embolden all participants in the archaeological process to continuously share and revise their thinking, with outreach activities potentially playing a key part in such honing of interpretative skill. Elsewhere, Dixon (Reference Dixon2017) describes his workshop series “Buildings Archaeology without Recording” in a manner that perhaps best articulates the kind of reflexive, nonhierarchical, interpretation-oriented methodology that I too seek to nurture. Herein Dixon prompts groups to physically explore sites based on certain thematic constraints, after which they come together to debrief and consider their varied observations and interpretations. The emphasis is thus not on indoctrinating participants in rote method but on honing more complex, high-level interpretative and communicative skills that usually are not taught, yet as he puts it, can actually “contribut[e] to a different archaeology” as well as being “useful in people's daily lives away from archaeology” (Reference Dixon2018:220, 219). Indeed, Dixon's model is not unlike one that we have used productively in Memphis, Egypt (http://memphisegypt.org/) to rapidly provide Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities inspectors with skills in applied heritage interpretation (see Figure 4). The feedback from the inspectors on this program maps directly onto Dixon's words; as per one trainee, “You help[ed] me to learn great things that [are] very useful for me not only [in] my career but also [in] my personal life” (Perry Reference Perry2017b:11).

FIGURE 4. Ministry of Antiquities inspectors assessing the Hathor Temple at the site of Memphis, Egypt, as part of an exercise in developing an interpretative trail for visitors to Memphis, Autumn 2015 (photo courtesy of Amel Eweida).

In all cases, I think the evidence testifies that heritage interpreters have far more of a role to play in the archaeological process than the narrow, degraded one that they typically occupy. Their tool kit and expertise allow them to mediate, to generate human-to-human dialogue both during and after excavations, and to create new worlds and literally build new visions of the past that are equally as meaningful to archaeological researchers as to nonspecialist audiences.

I plead here, then, for a rethinking of the disciplinary workflow, such that the interpreter finally sits at its core, negotiating between interested parties in the way that a truly reflexive archaeology was always meant to operate. I am not calling for heritage interpreters to become archaeologists—or for heritage interpretation to monopolize the interpretative endeavor—but, rather, for archaeologists to appreciate that heritage interpreters extend the field in untold ways, pushing into and beyond archaeology itself (after Almansa Sánchez Reference Almansa Sánchez2017). Their enrollment in the archaeological workflow from the outset, therefore, could mean the difference between a discipline that is a myopic cul-de-sac and a critically engaged practice that can productively change our outlooks on the world at large.

Acknowledgments

This research was partly and generously funded by two research grants from the British Institute at Ankara (2014, 2015) and supported by the European Commission–funded CHESS project (http://www.chessexperience.eu) as part of a scoping mission that led to the development of the European Commission–funded EMOTIVE project (http://www.emotiveproject.eu). Fieldwork for this article was conducted through archaeological research permits issued by Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı on 25 April 2014 (permit number: 94949537-.160.01.02 (42) - 80760) and 30 April 2015 (permit number: 94949537-.160.01.02 (42) - 85228). Many people have assisted me in thinking through these ideas and supporting their enactment at sites in Turkey, Egypt, Norway, Greece, France, and England. Although I do not presume that they all agree with my conclusions, I extend special thanks to Laia Pujol, Colleen Morgan, James Taylor, Katy Killackey, John Swogger, Angeliki Chrysanthi, Chris Wakefield, Peter Dunn, Bodil Petersson, Gabe Moshenska, James Dixon, Gísli Pálsson, Harald Fredheim, Narcis Pares, Paul Backhouse, Judith Dobie, Pat Hadley, and Ian Kirkpatrick for their critique, references, ideas, and inspiration. May artful integration be archaeology's new trowel!

Data Availability Statement

Original data presented in this article are accessible through the Çatalhöyük Research Project Archive Reports (http://catalhoyuk.com/research/archive_reports), in other publications (e.g., Roussou et al. Reference Roussou, Pujol, Katifori, Perry and Vayanou2015), or via contacting the author.