National surveys show consistently that the vast majority of Chinese people trust the central government.Footnote 1 Two recent surveys continue to paint a sanguine picture of political trust in the country. The Edelman Trust Barometer finds that over 80 per cent of the Chinese population trust the central government, while only half as many Americans trust the federal government.Footnote 2 An online survey finds that trust in the central government grew even stronger following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic,Footnote 3 presumably because the authoritarian regime outperformed many electoral democracies in containing the public health crisis that it failed to prevent.

Scholars, however, disagree about how to interpret the survey results. Some analysts take the all-or-nothing approach. Kenneth Newton argues that “it is difficult to believe the high figure for political confidence. It is likely to be a response to social pressures and political controls.”Footnote 4 By contrast, some researchers do not question the validity and reliability of the survey data. They proceed to explore the sources and implications of high trust in government.Footnote 5 There are other scholars who do not dismiss the survey results but neither do they accept them at face value. Tianjian Shi investigates whether political fear has a significant effect on responses regarding sensitive topics such as political trust. He reaches a negative conclusion.Footnote 6 Several scholars conduct experimental studies to test the reliability of survey results. They detect dissimulation and bias but conclude that the problems are not severe enough to invalidate survey findings.Footnote 7 Yet another group of researchers suspects that the survey results may inflate political trust in the country. Zhengxu Wang and Yu You together point out that merging the response of “a great deal of trust” and the response of “quite a lot of trust” into a broad category of “trust” misses an important nuance. They argue that two waves of the Asia Barometer Survey record “a clear decline in the level of political trust in China between 2002 to 2011.”Footnote 8 Lianjiang Li suggests that the widespread distrust of local government may reflect doubts about the central government's capacity to discipline local officials.Footnote 9 Kerry Ratigan and Leah Rabin find that high rates of item nonresponse to questions about trust in government result in artificially high estimates of political trust.Footnote 10 However, neither of the latter two studies offers an accurate estimate of the inflation rate. And although a dozen national surveys have been conducted in the last three decades, it remains unclear how much popular trust the authoritarian regime enjoys. The lack of consensus on the issue in turn fuels the long-standing debate on the resilience of the authoritarian regime, which has gained new momentum in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 11

This paper argues that a conventional interpretation of the survey results overestimates political trust in China. It starts by explaining why the concept of political trust has limited applicability in the country. It then shows that the conventional measurement scheme fails to capture three distinctive characteristics of political trust in the party-state. First, the target of political trust is the Centre. Second, the critical issue domain for assessing the Centre's trustworthiness is policy implementation rather than policymaking. Third, the Centre's trustworthiness incorporates a dimension of commitment to good governance and a distinct dimension of the capacity to discipline local officials. The paper contends that observed trust in the central government indicates trust in the Centre's commitment and that observed trust in local government reflects confidence about the Centre's capacity. Based on this argument, the study hypothesizes that the two-dimensional trust in the Centre has four representative patterns: total trust, partial trust, scepticism and total distrust. It draws on a local survey and a national survey to test the hypothesis. The paper concludes that the observed trust in the central government considerably inflates political trust if it is mistaken for latent trust in the Centre.

Conception and Measurement

Political trust is citizens’ belief or confidence that the government will work to produce outcomes consistent with their expectations.Footnote 12 The prototype of trust is inter-personal trust, which presupposes that the truster and the trustee are fundamentally equal before a higher principle.Footnote 13 Derivatively, political trust presupposes the principle of popular sovereignty.Footnote 14 The governed can meaningfully trust a government if they can retract trust when the government fails to meet their expectations. The concept of political trust applies to China because the ruling party recognizes the principle of popular sovereignty. However, the concept faces a fundamental limitation because the ruling party denies people the right to withdraw trust through elections. As a result, what appears to be trust may reflect more a wishful hope than a binding expectation. National survey results significantly inflate political trust if one treats observed trust in the Chinese central government as substantively equivalent to observed trust in a democratically elected national or federal government.

The study focuses on a more obvious problem, which is that the conventional measurement of trust fails to capture distinctive features of political trust in China. The measures of trust in government employed in national surveys work well in democracies with the rule of law. In those countries, citizens can trust the government without trusting the most powerful politician; they judge the trustworthiness of a government institution primarily or even entirely based on its performance in policymaking; and they do not have to distinguish between the commitment and capacity of a government institution.Footnote 15

However, China is an authoritarian party-state under the rule of man. Political trust in the country is distinctive in terms of target, critical issue domain and dimensionality.Footnote 16 First, the target of trust is the ruling party's central leadership (in short, the Centre), which is ultimately the supreme leader of the ruling party. When they talk about the national or central political authority, people use a variety of terms, including “the Centre” (zhongyang 中央), “the Party Centre” (dangzhongyang 党中央), “the central Party leadership” (zhongyang lingdao 中央领导), or “the Party Centre and the State Council” (dangzhongyang guowuyuan 党中央国务院). Most frequently, they use “the Centre.” In the broad sense, the term “Centre” refers to all administrative, legislative and judicial agencies that have qualifiers such as “state,” “national” or “supreme” in their names – for example, the State Council, the National People's Congress, the Supreme People's Court and the Supreme People's Procuratorate. However, none of these political institutions is identical to the Centre, as people may lose confidence in them without losing trust in the Centre.Footnote 17 Besides, the Centre is not a political institution that operates under established principles and rules. Instead, it is a group of senior leaders known as “Party and state leaders” (dang he guojia lingdaoren 党和国家领导人), with a single “core leader” (lingdao hexin 领导核心) being the dominant player.Footnote 18 The “core leader” has the power to veto all critical decisions. At times, he can even openly supersede the central leadership. For example, Mao Zedong 毛泽东 overtook the Centre in claiming the most loyalty during the Cultural Revolution.Footnote 19 Moreover, despite moves to build the rule of law,Footnote 20 the country remains under the rule of man because the supremacy of the “core leader” remains uncompromised.Footnote 21 In sum, the term “central government” invokes a target of trust that is conceptually very different from a national or federal government in a democracy with the rule of law.

Second, the critical issue domain for assessing the Centre's trustworthiness is policy implementation rather than decision making. Citizens of democracies focus on whether government institutions work in the public interest in making legislation and issuing executive orders when evaluating their trustworthiness. The critical issue domain is decision making. Citizens remain confident if the government institutions meet their expectations with regard to abiding by established rules and promoting citizens’ interests. Policy implementation affects trust in government only to the extent that it is considered a built-in element of a policy.Footnote 22 Again, China is different. People care about decision making when they evaluate the Centre's trustworthiness, and they loathe ill-conceived central policies. However, even when they condemn a fateful decision such as launching the Great Leap Forward, many people insist that Mao Zedong was well-intentioned and worked to make the country prosperous and powerful overnight. People tend to have confidence in the Centre's commitment to governing the country well. They may not believe that the Centre wants to govern for them, but they do tend to believe that it does not govern against them. They may not believe that the Centre wants to serve them, but they tend to believe that it does not want to alienate them. They may not believe that the Centre wants to protect their lawful rights and interests, but they tend to believe that it is in the Centre's self-interest to prevent rapacious local officials from driving them to revolt. The untested trust in the Centre's commitment to good governance is like a faith, which is particularly prevalent in assessing the trustworthiness of the “core leader.” Many people regard the supreme leader as the master or owner of the country, and they believe that he must want to keep the people contented for his immediate political safety and his status in history.Footnote 23

The Centre's trustworthiness becomes more questionable in policy implementation, especially the implementation of central policies that people find beneficial. There are two different types of central policies and, accordingly, two distinct dynamics of implementation. In the implementation of state-centred policies such as political control, taxation and stability maintenance, the Centre is the principal, the local government is the Centre's agent, and ordinary people are the target of policy enforcement. By contrast, in the implementation of alleged “people-centred” policies such as combating corruption, practising the mass line and protecting people's lawful rights and interests, the Centre remains the principal, local officials become the target of policy enforcement, and ordinary people are allowed to help the Centre monitor local officials through institutional channels such as petitioning and administrative litigation.Footnote 24 The Centre is subject to doubt when local government officials enforce policies that ordinary people dislike, ignore those they find beneficial and turn beneficial policies into harmful “local policies.”Footnote 25

The trustworthiness of the Centre has a commitment dimension and capacity dimension. In a democracy with the rule of law, the distinction between commitment and capacity is relevant when voters assess the trustworthiness of individual politicians.Footnote 26 For instance, Bernard Barber compares the “fiduciary commitment” and “technical competence” of Jimmy Carter and Robert Kennedy as presidential candidates.Footnote 27 The distinction is not prominent for assessing the trustworthiness of government institutions because even the most powerful politician is not above the law. However, the dichotomy of commitment and capacity is critical in assessing the trustworthiness of the Centre. Since the Centre is ultimately the “core leader,” assessing its trustworthiness is ultimately assessing if the “core leader” has a credible commitment and reliable capacity.

When it comes to assessing the trustworthiness of an individual, people tend to focus on his or her commitment: “When we call someone trustworthy, we often mean only his commitment.”Footnote 28 Similarly, when people are asked to assess the trustworthiness of the central government, many focus on assessing if the “core leader” wants to govern the country well. They do so by listening to what the central government says and what central policies promise. To this extent, observed trust in the central government may indicate the latent trust in the Centre's commitment

However, it is one thing to have a trustworthy commitment and another to have a credible capability. People know that the “core leader” has the power to make any political appointments he wants, but that does not mean he is capable of monitoring numerous appointees. It is one thing for people to believe that the Centre wants to have central policies enforced, and it is another for them to believe that the Centre can make local officials do its bidding.Footnote 29 People assess the Centre's capability by comparing what the central government says and what the local government does. To this extent, observed trust in the local government may reflect the latent confidence in the Centre's capacity to monitor and discipline local officials. People tend to have faith in the Centre's commitment to good governance, but they also tend to have doubts about the Centre's capacity to discipline local agents. Besides, trust in commitment and trust in capacity are “non-compensatory” dimensions.Footnote 30 Strong confidence in commitment does not offset weak confidence in capacity.

Hypothesis

Based on the preceding analysis, the study hypothesizes that trust in the Centre has four major patterns. Total trust is having strong confidence in both the Centre's commitment and capacity; partial trust is having strong confidence in its commitment without the matching confidence in its capacity; scepticism is having reservations and doubts about both commitment and capacity; and total distrust is having distrust of both commitment and capacity. The four patterns of trust in the Centre are expected to manifest as four combinations of trust in the central government and trust in the local government. To have total trust is to have strong trust in both central and local governments; to have partial trust is to have strong trust in the central government and weaker trust in the local government; to have scepticism is to have reservations and doubts about both the central and local governments; and to have total distrust is to have strong distrust of both central and local governments.

The hypothesis builds on and moves beyond an earlier study which identifies four patterns of trust in government: equal trust, hierarchical trust, “paradox of distance” (having more confidence in the local government than in the central government), and equal distrust. The earlier research suggests that the “paradox of distance” is a representative trust pattern, while the current study argues that it is exceptional. The pattern may deserve further scrutiny. It is uncommon because only between 0.4 and 6.5 per cent of respondents of five national surveys hold it.Footnote 31

The hypothesis is grounded in an analysis of the political system in China. In theory, the two-dimensional trust in the Centre has five major patterns. Total trust and total distrust are the two symmetric extremities, partial trust and “paradox of distance” are the two symmetric variants of lopsided trust, and scepticism is the middle category. Based on field observations, however, the study does not hypothesize that the “paradox of distance” is a representative pattern. The pattern is quite common in democracies where elected local governments are targets of trust in their own right.Footnote 32 In China, people may also have valid reasons to trust a local government more than the central government when, for example, an exceptionally courageous local government leader quietly protects them from an ill-conceived central policy.Footnote 33 However, such scenarios are exceptions. Despite the constitutional principle that the people's congresses elect government leaders at the corresponding levels, the central Party leadership appoints, directly or indirectly, all government leaders through a strictly top-down chain of power delegation.Footnote 34 All levels of local government are designed to be administrative appendages of the Centre. People may expect the local government to implement central policies faithfully, but they do not expect it to serve and represent their interests. As a result, people assess the trustworthiness of a local government in light of its role as the Centre's agent. Whether the local government carries out the Centre's biddings indicates whether it is loyal to the Centre, which reflects the Centre's capability to monitor and discipline. To assess the trustworthiness of the local government is to assess the Centre's capability to make its local agents do its bidding.Footnote 35 The analysis helps to explain why dissatisfaction with a local government's performance weakens trust in the local government without negatively impacting trust in the central government.Footnote 36 It also suggests that it is questionable to treat trust in local government in China as equivalent to trust in local government in a democracy.Footnote 37

Instead of treating the “paradox of distance” as a representative pattern of trust in the Centre, the study interprets the pattern as a sign of scepticism. The pattern implies having stronger trust in the capacity than in the commitment, but such a belief suggests a degree of suspicion about the Centre. It is common to have more confidence in capacity than in commitment when assessing an individual's trustworthiness in helping others. An individual may be capable of helping others but does not want to do so. It is also plausible that a fair or altruistic individual can, but does not want to, serve his self-interests. However, it would be expressing a degree of suspicion to say that the Centre can but does not want to discipline local officials. If an individual believes that it is in the self-interest of a “core leader” to govern the country well, then it would be cynical of that same person to say that the leader is not committed to serving his own interests by effectively monitoring and disciplining his local deputies. Such a statement implies that the “core leader” is too stupid to understand that it is political suicide to over-indulge corrupt local officials. In sum, it is intuitive to have more confidence in the Centre's commitment than in its capacity, but the opposite belief suggests doubts and even cynicism.

Data and Method

The study draws on two surveys to test the hypothesis. The local survey was conducted in 2006. Field sites were four counties, which were selected by convenience. Sampling in each county was conducted in three stages. First, five townships were selected with probability proportionate to size (PPS). Second, four villages were selected from each township with PPS. Third, within each selected village, around 20 randomly chosen individuals over the age of 18 were interviewed, regardless of village population size. |Altogether, 1,600 villagers were interviewed. The national survey is the Mainland China chapter of the third wave of the Asian Barometer Survey. It covers a probability sample of 3,473 respondents drawn from 94 counties and urban districts. Details of the sampling procedure of the national survey are available on the website of the survey proprietor.Footnote 38 Both surveys encounter the problem of missing responses. To improve the efficiency of estimation by reflecting additional variability owing to the missing values, this study assumes that observations are missing at random (MAR) and uses Amelia II to impute missing values.Footnote 39 All analyses were also performed on the original datasets using listwise deletion. Results obtained from the two alternative treatments of missing values are highly consistent.

The study employs factor analysis to explore the dimensionality of trust in the Centre. It then uses a semi-supervised machine learning procedure to identify representative trust patterns.Footnote 40 The procedure has two parts. The first step uses k-means clustering analysis to identify representative patterns of trust in government. Unlike conventional classification methods such as discriminant analysis, k-means clustering generates heuristic indicators for determining the optimal number of clusters. It also generates centroid coordinates, which indicate the average scores of a cluster of respondents on the feature vectors and hence suggest the defining features of the clusters.

The second step is supervised machine learning. The author inspects and annotates a subsample of randomly selected respondents to ensure that the classifications based on k-means clustering are empirically valid and theoretically interpretable. The author reclassifies problematic classifications in reference to original responses to the survey questions, the coordinates of the centroids of identified clusters, and field observations and theoretical reflections. The labelled subset of data is then used to train a classifier that optimally captures the underlying mechanisms which link the survey responses with the identified patterns of trust. The trained classifier is then used to predict the patterns of trust held by other respondents based on how they responded to the survey questions. The results of the supervised classification analysis are used to estimate trust in the Centre in the population. All machine learning analyses are performed with programmes stored in the scikit-learn machine learning library.Footnote 41

The study uses the local survey to ascertain the number of representative trust patterns and identify their defining features. However, local survey findings have only limited generalizability, so the study applies the same procedure to analyse the national survey. It uses the local survey findings as a foundation for making a critical decision in deploying k-means clustering.

Findings from the Local Survey

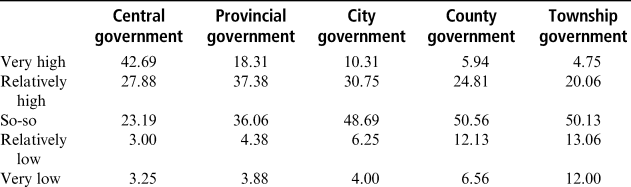

The local survey employs a full battery of refined indicators to gauge trust in all five levels of government comprehensively. It asks respondents to rate the level of popular trust enjoyed by five levels of government: central, provincial, city, county and township. The design is based on the observation that many rural residents have increasingly stronger trust in higher levels of government.Footnote 42 For many people, the central government embodies the Centre, and the provincial government is a loyal agent of the Centre. City government is included because it is a fully-fledged level of government in most provinces, although it is unconstitutional. The county government is critical for exploring the relationship between observed trust in the local government and latent trust in the Centre because it is historically the lowest level of government that directly governs the people.Footnote 43 The township government has a considerable impact on the lives of rural residents, particularly before the abolition of agricultural taxes. Unlike the national survey, the local survey uses a five-level scale to measure the level of trust, which ranges from very low, low, so-so, high and very high. The term “so-so” is often used in daily and political discourses, and it usually suggests scepticism or doubts rather than neutrality. Including “so-so” as a category of reservations and scepticism may reduce social desirability bias. Chinese people are culturally predisposed to understate doubts or distrust, especially when it comes to assessing the trustworthiness of government authorities. They feel more comfortable adopting an ambiguous position when they have doubts. Technically, including the neutral category makes it more justifiable to treat the ordinal measure of trust as a crude continuous variable, which justifies the application of k-means clustering. A five-level ordinal scale remains ordinal, but it is more plausible to assume that the distance between adjacent categories is approximately equal. The responses are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Trust in Five Levels of Government

Source: Author's survey.

Notes: N = 1,600. Column entries are percentages; totals may be above or below 100 owing to rounding errors. Missing responses are multiply imputed.

Exploratory factor analysis with variance maximization rotation sheds light on the structure of the trust in the Centre. It shows that the five indicators constitute two latent components. Besides, trust in the central government and trust in the provincial government load most heavily on the first component, which can be called “trust in the higher levels,” while trust in the county government and trust in the township government load most heavily on the second component, which can be called “trust in the lower levels.” Trust in the city government straddles the two categories, as it has roughly equal loadings on both components. The results are consistent with those of an earlier analysis of similar data.Footnote 44 The results support the proposition that latent trust in the Centre has two distinct dimensions. The political division of labour is that the Centre makes policies and decisions, while its local agents are responsible for the implementation of those policies and decisions. Trust in higher levels indicates confidence in the Centre's commitment to governing the country well. In comparison, trust in lower levels reflects confidence in the Centre's capacity to monitor and discipline local agents.

The study employs k-means clustering to explore the optimal number of clusters that underlie a multitude of patterns that the five feature vectors can form. In theory, the five indicators of trust in government can form 3,125 patterns. The survey observes 207 trust patterns. Three commonly used criteria – the elbow method, the silhouette value and the gap statisticFootnote 45 – indicate that the optimal way to summarize the data is to group respondents into four clusters. K-means clustering generates indeterministic results, pending the pre-set number of clusters, the initial set of randomly chosen centroids and the weighting of feature vectors. Following standard practice, the study ran the clustering analysis multiple times with varying settings and settled down an output that conforms with empirical observation and theoretical expectation.Footnote 46

The result of clustering analysis looks plausible as a whole. For example, two respondents seem to hold the pattern of “paradox of distance.” They have very weak trust in the central government but much stronger trust in the four-subnational governments. K-means algorithm classifies them as having scepticism. Nevertheless, some classifications do not conform with field observation and theoretical expectation. For instance, three respondents express very strong trust in the central government and very strong distrust of all four levels of subnational governments. K-means algorithm classifies them as having total distrust because it treats the five feature vectors as if they carry equal weight for assessing trust in the Centre. The study reclassifies these respondents as having partial trust. At the other extreme, one respondent expresses very strong distrust of the central government and strong trust in provincial, city and county governments and strong trust in the township government. K-means clustering classifies this respondent as having total trust in the Centre. More likely than not, however, the respondent is being sarcastic and is sceptical. Since weighting feature vectors are bound to be controversial, the study resorts to supervised machine learning to minimize such puzzling classifications. The supervised machine learning procedure involves inspection of 200 randomly selected respondents and manual reclassification of questionable cases. The labelled subset of the data is used to train a multinomial logistic regression classifier. Following the convention, 80 per cent of the training data are used as the training set, the other 20 per cent are used as the test set, and the number of iterations is set at 500. The trained classifier was then used to predict the patterns of trust held by the other 1,400 respondents.Footnote 47

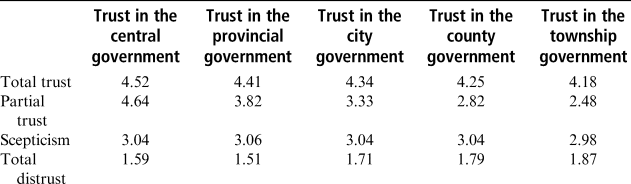

Four representative trust patterns emerge. First, 21.25 per cent of 1,600 respondents have total trust in the Centre. As Table 2 shows, they have an average score of 4.52 on the five-level scale of trust in the central government, and they have similarly high scores on trust in the four levels of sub-national government. It is worth noting that these respondents have an average score of 4.18 on the five-level scale of trust in the township government. At the time of the survey, the township government was hugely unpopular in the countryside, thanks to its roles in collecting excessive fees and enforcing the one-child policy.Footnote 48 To the extent that trust in the central government (or “the higher level”) indicates confidence in the Centre's commitment and that trust in local governments reflects confidence in the Centre's capacity, the pattern of total trust means having confidence in both the commitment and capacity of the Centre.

Table 2: Coordinates of Centroids of Four Groups of Local Survey Respondents

Notes: Row entries are group mean scores on the five-level trust scale: 1 = very low, 5 = very high.

Second, 48.38 per cent of respondents have partial trust in the Centre. Like those with total trust, individuals with partial trust have strong confidence in the central government. Their average score of trust in the central government is 4.64 on the five-point scale, which is slightly higher than that of people with total trust. Unlike those with total trust, respondents with partial trust have steadily less confidence in lower sub-national government levels. Their average trust scores are 3.82 for the provincial government, 3.33 for the city government, 2.82 for the county government, and 2.48 for the township government. The pattern mirrors a popular rhyme in the late 1990s: “There are blue skies at the Centre, clouds are gathering in the province, it is pouring in the county, people drown at the township level, and commoners are crying for help.”Footnote 49 Partial trust is substantively identical to hierarchical trust,Footnote 50 but it has a more precise substantive meaning. It means having confidence in the Centre's commitment without matching confidence in its capacity.

Third, 24.13 per cent of respondents hold some scepticism towards the Centre. They have nearly identical average trust in the five levels of governments, ranging from 2.98 to 3.06 on the five-level scale. This finding is new because the early study does not identify it in the five national surveys. It is important because it suggests that the response “so-so” indicates an oft-heard judgement of “half-believe and half-doubt,” which is a thinly veiled expression of scepticism or even distrust. The pattern of scepticism means having doubts about the Centre's commitment as well as its capacity.

Lastly, 6.25 per cent of respondents have total distrust of the Centre. They show a consistent distrust towards all five levels of government, as their average trust scores range between 1.59 to 1.87 on the five-point scale. To the extent that trust in higher levels of government indicates confidence in the Centre's commitment and trust in lower levels of government reflects confidence in the Centre's capacity, the pattern of total distrust means having confidence in neither.

The four observations show that a severe overestimation can occur if observed trust in the central government is mistaken for trust in the Centre. At first glance, 70.57 per cent of 1,600 respondents trust the central government. Upon further inspection, 21.25 per cent have total trust in the Centre, 48.38 per cent have partial trust, and 24.13 per cent are sceptical.

Findings From the National Survey

As plausible as they are, findings from the local survey have only limited generalizability. The study draws on the 2011 Asian Barometer Survey to see if respondents in the national probability sample have similar trust patterns. The survey includes two questions about trust in government. One question asks respondents to indicate how much they trust the central government on a four-level scale, and the other question asks respondents to indicate their trust in the local government on the same scale.Footnote 51

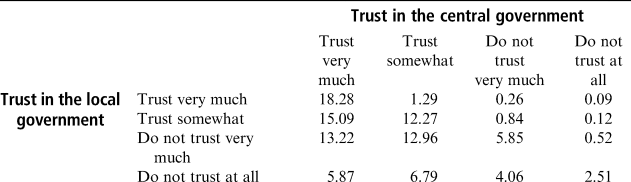

Exploratory factor analysis indicates that there is only one factor underlying the two measures of trust in government. However, reliability analysis shows that the two measures are so different from each other that they do not constitute an adequately reliable summation scale (Cronbach's alpha = 0.59). Based on the local survey's finding that trust in higher levels and trust in lower levels are two distinct dimensions of latent trust in the Centre, the study treats the observed trust in the central government and observed trust in the local government as two distinct dimensions. Table 3 summarizes the distribution of 16 observed trust patterns.

Table 3: Crosstabulation of Trust in the Central Government and the Local Government

Source: Asian Barometer Survey 2011.

Notes: N = 3,473. Cell entries are percentages; the total is over 100 owing to rounding errors.

The three commonly used criteria – the elbow method, the silhouette value and the gap statistic – suggest that the national survey respondents form three clusters. However, the more comprehensive and detailed local survey shows that respondents have four representative patterns of trust in the Centre. Assuming that all Chinese people share similar trust patterns, the study sets the number of clusters at four. The move supersedes a computationally optimal solution with an empirically grounded and theoretically sound decision.

Similar to what happens with the local survey data, k-means clustering generates a small number of questionable classifications. Of 3,473 respondents, 54 (1.55 per cent) show stronger trust in the local government than in the central government and are classified as having total trust. The k-means clustering algorithm classifies these respondents as having full trust in the Centre because it treats the two feature vectors as if they carry equal weight. The study regroups these cases into the cluster of scepticism. Since the data structure is simple, reclassification is performed with conditional recoding without resorting to the supervised machine learning procedure described above.

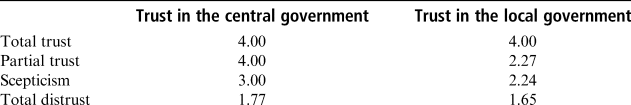

Four representative trust patterns emerge. First, among 3,473 respondents, 18.28 per cent have total trust in the Centre. They uniformly have strong trust in the central government, with a perfect score of four on the four-point trust scale. Meanwhile, they uniformly have strong trust in the local government, also with a perfect score of four (see Table 4). To the extent that observed trust in the central government indicates trust in the Centre's commitment and observed trust in the local government reflects trust in the Centre's capacity, this group of respondents has confidence in both the commitment and capacity of the Centre.

Table 4: Coordinates of Centroid of Four Groups of National Survey Respondents

Notes: Row entries are group mean scores on a four-level trust scale: 1 = strong distrust, 4 = strong trust.

Second, 34.18 per cent of respondents have partial trust in the Centre. Similar to those with total trust in the Centre, they uniformly have strong trust in the central government, averaging four on the four-point trust scale. However, they have moderate distrust of the local government, averaging 2.27 on the scale. In other words, respondents with total trust and partial trust share a strong trust in the central government. What separates them is that respondents with partial trust have doubts about the local government. As noted above, partial trust is substantively equivalent to “hierarchical trust,” but it has a more precise meaning.Footnote 52 To the extent that trust in the central government indicates trust in the Centre's commitment and trust in the local government reflects trust in the Centre's capacity, partial trust is having confidence in the Centre's commitment without the matching confidence in its capacity.

Third, 33.31 per cent of respondents hold a degree of scepticism about the Centre. They have moderate trust in the central government, with an average score of three on the four-point trust scale. Interestingly, they have moderate distrust of the local government, with an average score of 2.24. This finding is new. The fact that moderate trust in the central government is paired with moderate distrust of local government suggests that the two are essentially similar. The finding suggests that strong trust in the central government is qualitatively different from modest trust. Strong trust is a defining feature of total trust and partial trust in the Centre, while moderate trust in the central government defines a distinctive pattern of scepticism. The finding supports Wang and You's argument that the response, “a great deal,” is substantively different from the response, “quite a lot,” when assessing trust in the central government. As they point out, the common practice of merging strong and moderate trust in the central government into a broad category of trust misses an important subtlety.Footnote 53 When it comes to assessing the Centre's commitment to good governance, moderate trust may imply reservations or even doubts because it is in the Centre's self-interest to govern the country well. To the extent that the observed trust in the central government indicates confidence in the Centre's commitment and the observed trust in the local government reflects confidence in the Centre's capacity, this group of respondents is sceptical about the Centre's commitment and its capacity.

Lastly, 14.22 per cent of the respondents have total distrust of the Centre. They have fairly strong distrust of both the central government and the local government, averaging respectively 1.77 and 1.61 on the four-point scale. This group of respondents has confidence in neither the Centre's commitment to good governance nor its capacity to discipline local agents.

The four observations suggest that a severe overestimation can occur if the observed trust in the central government is mistaken for the latent trust in the Centre. At first glance, 85.77 per cent of 3,473 respondents trust the central government and 14.23 per cent distrust it. Upon further inspection, 18.23 per cent have total trust in the Centre, 34.18 per cent have partial trust, 33.31 per cent are sceptical, and 14.28 per cent have total distrust.

Conclusion

This paper proposes a new interpretation of survey findings of trust in government in China. The new measurement scheme treats the observed trust in the central government as an indicator of trust in the Centre's commitment and treats the observed trust in the local government as a reflection of confidence in the Centre's capacity. The study shows that the conventional reading of the national survey results considerably overestimates political trust in the authoritarian regime because it mistakes the observed trust in the central government for latent trust in the Centre. It is true that the vast majority of the population trust the central government; however, closer inspection shows that only about one-fifth of the population are confident about the Centre's commitment and capacity, one-third trust its commitment without the matching confidence about capacity, another third are sceptical about both, and nearly 15 per cent are distrustful of both. For scholars, the finding paves the way for exploring sources and implications of trust in the Centre. For policy analysts, the study suggests an innovative approach to obtaining a more accurate assessment of the authoritarian regime's “soft power.”Footnote 54

The study highlights the importance of contextualization for optimizing conceptual equivalence, which is critical to avoid concept stretching in comparative political studies.Footnote 55 Contextualizing a concept involves profiling its genetic structure in light of its specific context of origin. Applying a concept requires matching the genetic profile of a member of the conceptual family in a different setting with that of the prototype. In the comparative study of political trust, the prototype of trust in government can be traced back to John Locke's social contract theory on the one hand and the practice of representative democracy and the rule of law on the other hand. In a democracy with the rule of law, the target of trust is an elected political institution that is simultaneously responsible for legislation and administration. The critical issue domain is law-making, and the distinction of commitment and capacity applies primarily to individual politicians. The study shows that political trust in China belongs to the family of political trust, but it has distinctive characteristics. National surveys ask people to assess the trustworthiness of the central government, but the invoked target of trust is the ruling party's central leadership, which is ultimately its “core leader.” The central government is the organizational embodiment of the Centre, but the two are not identical. Since many people assume that the Centre is the master or owner of the country and therefore must be committed to good governance out of its own interest, the critical issue domain for assessing the Centre's trustworthiness is policy implementation rather than policymaking. Furthermore, since the Centre is ultimately the “core leader,” its trustworthiness has a dimension of commitment and a distinct aspect of capacity. Once contextualized, it is clear that the survey measures of trust in government are valid and reliable, but the survey results require a more nuanced interpretation.

Methodologically, the study demonstrates the value of machine learning techniques for analysing complex survey data. In particular, k-means clustering allows researchers to strike a better balance between computational optimization and theoretical validity.Footnote 56 Since the results of k-means clustering are indeterministic, researchers can choose a model that conforms with field observation and theoretical expectation without imposing a structure on the data. Moreover, supervised multinomial regression analysis minimizes questionable classifications without compromising the objectivity of the results of k-means clustering. The study also demonstrates the value of using complementary datasets. The comprehensive and detailed local survey provides a solid foundation for identifying representative trust patterns, while the national survey secures the generalizability of findings.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the financial support of the Hong Kong Research Grants Council (Project ID: CUHK14601820). He is grateful to Margaret Levi, Jean Oi, Jennifer Pan, Andrew Walder, Yiqing Xu, Xueguang Zhou and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments. He thanks Yue Guan for her insights on using machine learning to analyse survey data and Kai Yang for technical assistance.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical notes

Lianjiang LI is professor at the department of government and public administration at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.