Introduction

Teaching in a language revitalization context is not always about acquiring an Indigenous or heritage language as a second language; sometimes it is about awakening and strengthening the first language. Teachers of Indigenous languages come to teaching either as a speaker or as a second language learner. Our intention in writing this chapter is to present teaching methods and strategies that will strengthen both types of teachers – to give the reader a solid and meaningful understanding of how language learning theories can serve teaching Indigenous languages. We will then present various teaching methodologies and strategies that have come from these theories to show what they look like in the classroom, at home and in the community. The authors are Indigenous language teachers and learners in the Pacific Northwest of the United States and in Finland, implementing various teaching strategies in our communities, schools, and homes. Each of us has years of experience learning an Indigenous language, and we bring our insights in teaching language to this chapter.Footnote *

We begin the chapter with a broad overview of second language acquisition research from the last fifty years. Here Lindsay Marean links theories of second language acquisition and widely used methods of language teaching to the specific context of language revitalization. We then discuss, in a practical way, language learning theories and how they can better inform Indigenous language teaching choices. We introduce second language acquisition terminology that we then define in a real-world way and support with case studies. This will help the reader to become familiar with language learning situations and behaviors. Understanding these learning behaviors will help with teaching, creating lessons and materials, and language assessment.

We then ground this research in teaching experiences, using case studies from communities. The case studies we present are relevant to both first and second language teaching and learning situations.Footnote 1 Lindsay Marean discusses distance language study in Potawatomi, a Central Algonquian language of North America, and the use of Can-Do Statements from the National Council of State Supervisors for Languages – American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (NCSSFL-ACTFL) Benchmarks – in Pahka’anil in central California. Zalmai Zahir then discusses teaching and learning in language nests and reclaiming domains in the Lushootseed language from the Puget Sound region of Washington state. Next Pyuwa Bommelyn shares his experiences of teaching Tolowa Dee-ni’ from northern coastal California. He discusses two teaching methods: Accelerated Second Language Acquisition (ASLA) and reclaiming domains. Also included in this section is a sketch of learning Tolowa Dee-ni’ using the Master-Apprentice method, based on the experiences of Pyuwa’s father, Loren Me-lash-ne’ Bommelyn. Pigga Keskitalo then discusses how Sámi language and culture can meaningfully enhance education in the classroom, citing an example of a classroom modeled after a goahti – a traditional Sámi dwelling. Ruby Tuttle then looks at teaching language in a classroom at home as opposed to at school, and discusses homeschooling activities and strategies for elementary age learners in Tolowa Dee-ni’. Finally, Janne Underriner ends the chapter by sharing ways that teachers who have limited speaking fluency can teach lessons using rich language.

From Second Language Acquisition Theory to Indigenous Language Revitalization Teaching Practices

Second Language Acquisition Research

During the last fifty years, the study of how language is acquired has emerged and developed among those who are curious about human language and how our discoveries can be applied to language teaching and learning. Indigenous language activists often seek out applied linguists to guide their work. In turn, applied linguists seek out language practitioners to test their ideas and to gather information about the experiences and needs of language teachers and learners. However, Western science has a history of not valuing Indigenous ways of knowing. Indigenous people likewise are often distrustful of recommendations coming from colonizer institutions. In recent times, we have seen calls for a ‘productive symbiosis’ between the two perspectives, so that Western science and Indigenous ways of knowing can inform each other in mutually beneficial ways.Footnote 2

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Stephen Pit CorderFootnote 3 and Larry SelinkerFootnote 4 observed that second language learners are not making one-off mistakes but are in fact fairly consistent in the sorts of errors they make during the development of their second language. Consequently, researchers started investigating how learners process the language that they are learning, and the role of cognition.Footnote 5 Researchers looked at the importance of language input,Footnote 6 or the language that learners are exposed to; and language output,Footnote 7 the language that learners are able to produce/use and its role in helping learners to notice errors that hinder their communication. They also studied language interaction,Footnote 8 or the way that speakers and listeners convey meaning even when their communication breaks down. This demonstrates the need for teachers to understand that making mistakes is part of learning and that it is the teacher’s role to create lessons that address natural learning errors.

If we look at the process of learning the past tense in English, we see that first learners want to use the rule ‘add -ed (/d, t/) on all verbs’: walk – walked; appear – appeared; is – ised; teach – teached; give – gived.Footnote 9 Learners need many opportunities to hear and make errors so they can learn that many of the most frequently used verbs in English do not in fact follow this rule. In teaching and designing curriculum then, we need to offer learners a rich language environment (and find ways to do this even if as a teacher you are not fluent in the language; examples of how follow). Teachers also need to provide sufficient time for learners to practise using language, so that they can progress their learning through interacting in the language.

input ➔ output ➔ interaction ➔ adjust error ➔ move toward proficiencyFootnote 10

In this new millennium, second language researchers have started paying more attention to the diversity of people who are learning and teaching languages and how their life experiences affect this process. This has been called the ‘social turn’ in language acquisition research. Researchers are looking at issues such as the relationship between second language knowledge and community membership, and how one’s sense of identity impacts one’s use of a language. This is new and complicated territory for researchers. However, these are exactly the sorts of issues that some Indigenous language activists navigate in communities that are recovering from historical trauma in a world that still favors settler colonialism. A teacher who creates a thriving language learning environment considers such relationships – integrating their knowledge of how learners acquire language with teaching practices that best serve their learners. At the same time, they reflect on how their own upbringing, traditional practices, language exposure, and language learning experiences can support learner identity and well-being.

Language Teaching and Learning Methods Overview

No single theory of second language acquisition fully accounts for all aspects of language learning, yet each new perspective fills in gaps that are unaddressed in previous theories. This growth is indicative of good scientific inquiry. No single ‘best practice’ exists in language teaching and learning methodology. Each approach has its own strengths and weaknesses and the decision to employ an approach depends on the particular context, taking into account community history, needs, and desires. Some language activists seize on the first method that is presented to them (or the one that they found helped them to learn a language) and implement it without critical reflection and adaptation. However, it can be more effective to step back from a method and consider its theoretical assumptions and the context in which it was developed. From there, activists can identify which aspects of the model are well matched to their learners’ needs, as well as gaps that need to be addressed. It is necessary to emphasize that regardless of the path that led them to language teaching and learning, language activists have the greatest impact when they feel equal to the researchers and practitioners that they learn with and from. There are also practical challenges to teaching and learning a language with limited learning materials and limited opportunities to speak it. These are not necessarily accounted for by researchers, who typically work with large languages such as English.

Figure 15.1 A Manx picture dictionary.

Some Methods

In this section, we describe some popular, currently used methods for teaching and learning language.

Immersion is often seen as an ideal model for learning Indigenous languages. The simplest form of immersion is natural intergenerational language transmission. We simply grow up speaking the language of our caregivers as a first language. This is the form of language teaching and learning that Indigenous communities used prior to the disruptions caused by settler colonialism. Native communities have responded to the disruption of intergenerational transmission in a number of innovative ways. Language nests, pioneered by the Māori, involve immersing young children in a nurturing environment of Indigenous language and culture, often involving elders and knowledge bearers in children’s lives. Pyuwa Bommelyn (Case Study 4) shows ways to use language in a classroom-nest setting.

Immersion is a life-long process, extending beyond early childhood. Immersion schools continue or start the immersion process by educating children in their Indigenous languages. In some cases, children come to school already speaking their Indigenous language, and immersion schools help them to develop specialized and academic language use. In other cases, children’s first exposure to their Indigenous language is in school. For adults, several approaches have had good results. The Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival pioneered the Master–Apprentice model, in which an adult (or teenage) language learner is paired with an older or more proficient speaker over a period of several years for intensive one-on-one immersion sessions.Footnote 11 The Nishnaabemwin Pane program, offered through Bay Mills Community College in Michigan, runs large-group adult immersion in a classroom-like setting. Proficient speakers tell stories and perform skits in a low-stress, language-rich program. Another promising direction is the emergence of language houses where dedicated adults choose to live in a space entirely dedicated to Indigenous language learning and use.Footnote 12 A related approach is Zalmai Zahir’sFootnote 13 method of creating language nests within the home through a process of reclaiming domains (see Case Study 3).

The Grammar-Translation method of language teaching has been around for millennia. Learners study texts written or spoken by proficient language speakers, they note key vocabulary and memorize it, and they observe language patterns, especially the ways that nouns and verbs behave. They also memorize charts of word forms to help translate from one language to another with accuracy. In grammar-translation classes, the original text is of great importance. Teachers and learners end up spending a lot of time talking about the text and the language in it, and less time speaking in the language or producing their own meaningful utterances.

On the other hand, direct and audio-lingual methods prioritize use of the target language at all times. Grammar is not directly taught. Instead learners listen to and pronounce sentence after sentence after sentence. In this way, they learn grammar rules through exposure and practice. Correct pronunciation is emphasized, and students ‘overlearn’, practicing learned phrases until they become automatic. Most language-learning apps that are marketed today (such as Rosetta and Berlitz) make use of the direct method. Similarly, many Indigenous language-learning apps are also based on these approaches. The Ulpan method, popular for teaching Celtic languages, is an example of the audio-lingual approach. The kinetic activities described in Case Study 6 are also inspired by these methods.

In the world of ‘foreign’ language teaching, especially in the United States and other Western countries, professional teachers are trained to focus on language proficiency through a communicative or proficiency-based approach. In this framework, students develop proficiency by engaging in tasks that simulate real-life use of language and by interacting with authentic materials in the target language. For example, students might study a French-language map of the subway system in Paris to figure out how to get from one place to another. They might converse with other students to find out how many pets they have and what their names are. Curriculum is often organized thematically, and it follows the principle of backwards design, in which curriculum is developed by first thinking about the proficiency goals and how to assess them, and then what sorts of activities directly prepare students to meet those goals. The ‘five step’ approach and pair activities mentioned in Case Study 6 are examples of a communicative approach.

Another popular trend among language teachers is radically input-based teaching. Lindsay uses this term to describe a collection of approachesFootnote 14 used by a growing number of teachers, which focus on making language completely comprehensible to students. Students are only expected to produce language voluntarily. Extensive reading to expose learners to more language is often important in this approach. These approaches are especially well suited for teachers who are themselves still learning the Indigenous language but who nevertheless want to expose their students to extensive language input, as described in Case Study 8.

Be Informed, Be Empowered

None of the above methods is perfect. There is no proven single best practice in language teaching and learning. Rather, there are good practices, and a good language teacher or program leader uses those that best fit the local context. Immersion can produce second language speakers who sound very similar to first language speakers and who are strong in their Indigenous identity. However, such programs are resource-intensive and rely on having teachers who are confident and proficient in their Indigenous language. Also, if the Indigenous language is not used outside of schools, that is, in the wider community and in learners’ homes, then language gains can disappear as quickly as they came once students leave school.

Grammar-Translation may give students insights into language patterns and the way that proficient users speak, and they make good use of the sort of text collections that language activists frequently find in archives. However, learners using this method are often unable to participate in basic conversations because they have not had any practice with interpersonal communication.

Direct methods can address community concerns about how one’s first language, which is typically a colonizing language, affects the learner’s second language use and becomes the new norm for the Indigenous language in future generations. However, their reliance on repetition and practice of provided language means that learners may not be able to express original thoughts in their own words and with their unique voices.

Proficiency-based approaches offer a broad framework that makes it easy for learners to see their progress, leading to greater retention in community language programs. However, these approaches have not been used much yet in Indigenous and endangered language contexts.

Heavily input-based approaches are especially good for adults who may have a number of emotional barriers around their Indigenous language, since they are not pressured to speak unless they want to. However, most adults’ language goals include the ability to produce language, which is not emphasized in these approaches.

In other words, every method has its own strengths and weaknesses. Language activists must consider their own desires, the desires and resources of their communities, and the traditional worldview and lifeways that frame their language revitalization efforts. In conclusion, theories and methods of second language acquisition can really inform the work of language revitalization and save us all time as we learn from those who have come before us. In doing so, we must be unafraid to question and challenge researchers and practitioners that we interact with. If you have chosen to be an activist for your heritage language, you have already navigated a complex universe of identity, loss, relationships, and rich cultural knowledge. Your lived experience is irreplaceable and should guide you as you decide how you will proceed with your language activism.

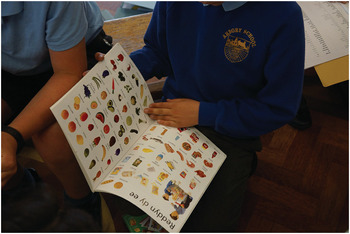

Figure 15.2 A Manx language class taught by Jonathan Ayres, Arbory School, Isle of Man.

Figure 15.3 Nahua children reading a pictorial dictionary. Chicontepec, Mexico.

Case Studies

We turn now to eight case studies to illustrate on-the-ground practices for first or second language teachers and learners of Indigenous languages.

Case Study 1 Lindsay Marean Potawatomi Distance Learning and Workshops

Lindsay Marean is a language activist,Footnote 15 who is both a learner of her community’s language, Potawatomi, and a linguist working for the Tübatulabal community in California. In addition to her experience working on documentation projects, such as a Potawatomi dictionary and corpus, she has also taught Spanish in public schools, supervised preservice language teachers, and worked to connect teachers with second language teaching and learning research projects at the Center for Applied Second Language Studies. She says that, as an Indigenous language activist, she has been lucky to meet and work with many other language activists.

Every Monday night, Lindsay meets online with some fellow Potawatomi people, and they use the grammar-translation method as they work through recordings of their elders speaking Potawatomi. They look up words in dictionaries or ask people who speak different regional varieties if they have heard certain words before. They study verb prefixes and suffixes, and puzzle over why certain discourse markers are used in different places. Lindsay explains, ‘We have these wonderful recordings, we have curious adults who are interested in how Potawatomi works, and I don’t have time to prepare any formal lessons. I recognize that we aren’t developing our conversational skills or learning to do things like pray before a meal when we dissect these texts, but we are developing a feel for how our first language speakers use our language, and we are gaining new insights into traditional Potawatomi ways of thinking as we listen, line-by-line, to our elders sharing with us what they thought merited being recorded in our language’.

In another case, Lindsay, who usually favors communicative approaches, chose to use a radically input-based approach two years ago at an event hosted by the Pokagon Band of Potawatomis. She rephrased an incident from Potawatomi history into simple sentences and presented them one at time, followed by a prescribed set of questions that first require with yes/no answers, then progress through either/or answers, and end with more open-ended who/what/where/when type questions (this sequence is called ‘circling’). By the end of the week quite a few people in the class could tell the entire anecdote in Potawatomi. Participants may not have learned how to express their own original thoughts during the lessons that week, but they reclaimed a little-known part of their history as part of an oral tradition that they now share.

Case Study 2 Lindsay Marean – Can-Do Statements in Pahka’anil

In her work as a Practical Linguist for the members of the Tübatulabal Tribe in California who are teaching their language, Pahka’anil, Lindsay uses a proficiency-based approach for tracking language growth. She and the teachers she works with are piloting the use of the NCSSFL-ACTFL Can-Do Statements,Footnote 16 a set of examples of what learners can be expected to do in their target language (for example, can introduce him/herself and others and can ask and answer questions about personal details), arranged by proficiency level (Novice, Intermediate, Advanced, Superior, and Distinguished) and mode of communication (interpretive, presentational, and interpersonal). Language teachers collect evidence of their students’ language development and maintain language portfolios showcasing their growth. This is one very small piece of what these teachers do in their work to carry Pahka’anil on in future generations, and also one very small piece of what Lindsay does as their linguist. However, their experience so far is that using language portfolios aligned with the Can-Do Statements is helpful for guiding development of curriculum and for setting goals for ongoing growth as Pahka’anil users.

Case Study 3 Zalmai Zahir Lushootseed Language Nesting in the Home

Zalmai Zahir is of Sioux ancestry on his mother’s side and was raised by his mother and Puyallup step-father. It was from them that he learned the importance of language and culture. He began learning Lushootseed from his step-father at age eleven and began teaching it in 1989. He also studied and apprenticed with Lushootseed elder, scholar, and professor, Dr. Vi Hilbert. Using various teaching methods over the years with limited success, Zalmai developed a methodology that borrows from various approaches, including reclaiming domains and ‘language nesting’. He has turned portions of his home into a Lushootseed language nest by focusing on using language with specific activities, such as sweeping the floor, making breakfast, and washing the dishes. Zalmai is reclaiming these activities as Lushootseed domains within his home. He teaches and assists other learners and language programs on how to use this approach.

Over the past thirty plus years we have seen that learning language in ‘nests’, places where language is fostered and cared for as a parent cares for a child, places where learning is nurtured and respected, has proven to produce fluent speakers.Footnote 17 And, in particular, speakers of Indigenous languages who are using this model to revitalize their languages are finding it vital to language use as it requires learners to speak and converse on a regular basis. Zalmai defines two types of nests that exist for language revitalization – a nest for children, and a nest for language. ‘A “nest for children” is a physical location where the children are nested in the language. This is the primary accepted definition by language revitalizationists. A “nest for language” is a physical location where the language is nested, not the learners. It is not limited to the involvement of children, and it can occur in the home.’Footnote 18 Zalmai broadens the definition of a language nest to a ‘place in the home, or the whole home itself, where adult learners and speakers with or without children will use the language. This can facilitate the growth of language use to several hours per day, and it provides a means for language transmission to friends, family and children’. It allows for activities of daily living to be ‘reclaimed’ in the language of the home.

As we will see in other case studies, language nesting can occur in locations in and outside of the home. Wherever it occurs, the goal is to speak the Indigenous language every time one is in that space. The dominant language is not allowed to be spoken in language nests. When a physical space is created to specifically support language use, learners have to speak the language. Teachers then create learning materials for real-life activities and teaching occurs one activity at a time.

For example, choose a room where you want to use the language. If you live in a family or with friends, decide together which space you want to begin with. For example, if you eat together, cook together, and use the kitchen to socialize, consider beginning in the kitchen. Because the kitchen functions as a gathering space, it supports the extended learning of friends and family. Many domains can be reclaimed in the kitchen (we list a few below).

Activities to support learning in the kitchen:

(1) using the sink

(2) washing your hands

(3) cleaning the counter

(4) washing dishes

(5) putting away groceries

(6) making a sandwich

(7) making a cup of tea

(8) making coffee

(9) frying an egg

(10) boiling vegetables

Once you have an idea of the activities you want to reclaim, then the next step is to identify the language phrases you will need and to teach them. We suggest you begin with self-narration, saying aloud the words and phrases as you do each of the actions. This will help you decide if the phrases you chose are relevant to the activity, and it will help you to determine the ordering of the actions in the activity. Additionally, this process reinforces language learning by physically doing what you are learning. As a teacher you can see how these activities create a framework for learning and how they contribute to building your kitchen curriculum.

Here is an example script to try if you want to reclaim the domain of washing your hands.

(1) I turn on the water.

(2) (Now) I take the soap.

(3) I put it on my hands.

(4) I wash my hands.

(5) I rinse my hands.

(6) I turn off the water.

(7) I take the towel.

(8) I dry my hands.

Zalmai has found that if he is more prescriptive with the process, i.e. ‘Take this activity and post it in your bathroom. Do it each time you wash your hands, increasing your daily language use by five minutes per day’, learners have better success.

If you need help coming up with the phrases you want to teach, you can go to other speakers in your community. For communities who no longer have first speakers, you can look at documented language materials such as texts, grammars and dictionaries, or work with a linguist to gather words and phrases. These sentences will grow as your lesson plans develop.

Here is a visual learning tip:

Make labels writing the needed vocabulary and phrases on them.

– Write the names (nouns) of each object you want to learn

– Write the actions (verbs) you are wanting to learn

Post names and phrases in areas of your home (or other places) where activities will take place, so for this activity, in the kitchen.

– Use the labels to learn nouns.

– Use phrases to learn actions

Say the vocabulary and phrases aloud as you are doing the actions and teaching them. Record them on your phone and listen to them during the day. Ask your students to do the same in their homes. The key for all activities is using the language.

Case Study 4 Loren Me-lash-ne’ Bommelyn Master-Apprentice Language Learning Model

Loren Me’-lash-ne Bommelyn is Tolowa, Karuk, and Wintu and is a tradition bearer for the Tolowa tribe. He has dedicated himself to preserving traditional songs, language, and basketry. He is the foremost ceremonial leader of the tribe, and its most prolific basketweaver. Me’-lash-ne is an enrolled member of the federally recognized Tolowa Dee-ni’. His mother, Eunice Bommelyn, was a prominent first speaker of the Tolowa Dee-ni’ language, an Athabaskan language spoken in coastal Northern California, at Crescent City and Smith River, and a cultural advocate. Me’-lash-ne is a fluent speaker of the Tolowa Dee-ni’ language and taught for over thirty years as a Tolowa high-school language teacher in Crescent City, California.

From the time Me-lash-ne’ was a child he wanted to know everything there was about plants. It was his dream to be an ethno-botanist and horticulturist. Also, he was curious about his family’s language, Tolowa Dee-ni’, as his mother was a speaker. He would go with her to visit elders and family and listen to them as they spoke. He would practice and put to use the language he learned. His interest in plants and language was known in the community, and he would ask many questions of his elders on these visits.

One of the learning strategies Me-lash-ne’ used when walking to school, or to family and friends’ homes, or to anywhere really, was that when looking at an object, he would replace the English word for the Tolowa Dee-ni’ word, and over time he saw his environment through Tolowa Dee-ni’ eyes.

Me-lash-ne’ studied traditional dance and song with an elder and through these teachings he created his own songs in Tolowa Dee-ni’ to which dancers dance today. For everything Me-lash-ne’ wanted to learn and know about, he found an elder to teach him, to apprentice with. It was in this way that he learned Tolowa Dee-ni’, and now as a master himself, learners apprentice with him. The essence of this teaching/learning method is to immerse oneself with the language in an environment with an elder, relying on the environment and one’s curiosity to guide learning.Footnote 19

Case Study 5 Pyuwa Bommelyn Tolowa Dee-ni’ Programs and Teaching Strategies

Pyuwa Bommelyn is a Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation tribal member and a second language speaker of Tolowa Dee-ni’. He is the son of Loren Me-lash-ne’ and Lena Bommelyn, and grandson of Eunice Bommelyn. Me-lash-ne’ and Lena raised their three children in the Tolowa Dee-ni’ language, with Me-lash-ne’ speaking to his children, and now grandchildren, primarily in Tolowa Dee-ni’. Because of this, Pyuwa and his wife Ruby Tuttle are able to raise their three children in Tolowa Dee-ni’. Ruby teaches their children at home (homeschools) providing an education rich in language, culture, and academics.

In this section we share different teaching methods of Tolowa Dee-ni’ in early education, home, high school, and community language programs that serve three-year olds to seniors (60+ years).

Accelerated Second Language Acquisition

The Accelerated Second Language Acquisition (ASLA) approach, attributed to Dr. Stephen Greymorning (Neyooxet), is used in community and high-school classrooms.

ASLA teaching goals first target ‘imprinting’ nouns and verbs (the heart of the language), using concrete examples in the language. Once learners can use these with each other, they move onto the more abstract parts of the language, such as descriptors, adverbials, and classifiers, for example. Verbs are kept in the first and second person singular form most of the time to make learning more tangible.

Depending upon what class it is, Tolowa Dee-ni’ teachers make their own teaching materials (language learning skill sets) which they call ‘Indintivities’. Activities include Total Physical Response commands to support learners doing the motions they are learning, providing a kinesthetic input to learning. Once learners are familiar with the vocabulary, pair and group learning activities focus on using the vocabulary in specific domains. For example, in a lesson on Vine tea learners work on associated nouns, verbs of actions, and commands on plant identification: where the plant is located; when and how it is gathered and processed; why it is used; and its health benefits. This learning includes cultural knowledge about what one needs to know before picking the plant.

ASLA Learning in Domains – Reclaiming the Language of Place

As seen above with Vine tea, ASLA learning techniques can be used to reclaim domains and to bring language into daily life in specific spaces where it had not been used for some time. Here are some examples of developing language fluency within specific domains using ASLA strategies.

Classroom – In the classroom, young children learn to respond to and ask phrases like: come and sit at the circle; please set the table; would you like some milk?; time to brush teeth; I have to go to the bathroom; will you be my partner?; time to clean up.

Home – learners learn vocabulary related to cooking a meal, beginning with a scripted conversation until enough language is learned to be conversational.

Community – In the community, a cultural location can act as a domain – a particular place on the reservation tied to a traditional lifeway. An example for the Tolowa Dee-ni’ is the place where smelt fish are found. Fish are caught with a net and are then dried on the beach. Prior to learners fishing at the beach, teachers will teach vocabulary and phrases in the classroom. They will teach the cultural traditions of smelt fishing and drying so learners are better prepared to do the activities in the language. Once learners are at fish camp, this language will be used as they fish, prepare, and dry the fish.

High School – Teaching at the high school provides the most consistent learning environment. Students can take two years of daily Tolowa Dee-ni’ classes for credit at the local high school, Del Norte High School (DNHS), taught by Guylish Bommelyn. This structure provides a framework for successful learning in contrast to the weekly community classes that have varying levels of attendance and thus pose a challenge to consistent learning. At the beginning of the year, Guylish gives students a survey, asking them to identify their learning interests. From this he plans lessons in the domains that students suggest. Initial lessons taught using ASLA include nouns, adjectives, and verbs, including commands. Additionally, he uses games, and incorporates body movement to learn Tolowa Dee-ni’ verbs.

For example, ‘ice cream’ was identified as a domain that students wanted to learn. Guylish brings ice cream into the classroom using language to: (a) ask for ice cream, (b) explain how to get the ice cream out of the container; (c) give ice cream to classmates/each other; (d) describe the taste; and (e) discuss likes and dislikes. Language domains change throughout the year.

Pole fishing is another example. There are Tolowa Dee-ni’ words for fish, pole fishing, stream, and hook, but not words for bobber, weight, spool. Thus, new vocabulary is needed for these domains. So teachers look at how nouns are formed and come up with a new word based on this same pattern so that learners can use the language longer in the domain for longer. Then learners can talk about ‘catching a fish, reeling it in, and attaching a weight’; all the actions needed for pole fishing. Videos of this particular unit have been created, and lessons are posted on Instagram that are linked to the Tolowa Dee-ni’ Language Program’s Facebook page and the Tribe’s website for tribal members to access when wanting to integrate language into their activities.

Language in the Home Program

The Tolowa Dee-Nation’s Language Program implemented a language in the home program over three years ago. Families are required to commit to learning Tolowa Dee-ni’ for at least one year. To begin with, a pre- and exit assessment on each family’s general attitude toward learning the language was created and used to design the year of Tolowa Dee-ni’ lessons, which provides a benchmark of what families learn in the year. The first part of the program engaged families in discussing their language learning attitudes. A Tolowa Dee-ni’ teacher goes to a home to talk about language barriers, asking, for example, ‘What are the barriers to family language learning; How does it make you feel learning language now?’

Families received a visit once a week from a Tolowa Dee-ni’ language teacher. Tolowa Dee‑ni’ materials were made for that home by the language teacher, and families were taught how to use the materials for meaningful language learning in their home. Each family had a language quota (how much Tolowa Dee-ni’ language they can/want to learn in a year). The Tolowa Dee-ni’ teacher and family members then talk about what is realistic for them and language learning techniques. The Māori language program philosophy and the questions the Māori use to learn language are used as a guide for family learning. The Language in the Home program has been successful for five families. An important aspect for the families is that they need to set their own goals and be responsible for their own learning. This is emphasized throughout the year.

Some Closing Remarks

The point of learning the language of many domains, and why the Tolowa Language Program emphasizes language use and creating new words, is that they want learners to use language on a daily basis. They support learners to use ‘everyday’ speech. What strategies are used to support this? Extending immersion times in the classroom; learning in domains; building up language so learners can stay in the language and use it for longer periods of time; working on language attitudes in the community because any negativity impedes language learning; and sharing the language to accommodate Tolowa sister language varieties to be inclusive of how all folks learned to say things.

Case Study 6 Ruby Tuttle Tolowa Dee-ni’ as the Language of Homeschooling

Ruby Tuttle (Yurok/Yuki/Maidu/Karuk) and Pyuwa Bommelyn began schooling their children at home (homeschooling) in the language of their family, Tolowa Dee-ni’, in 2013. Ruby and Pyuwa made the decision prior to the birth of their children that they would raise their children in Tolowa Dee-ni’. And as the children grew and decisions needed to be made about how they would be educated, it became apparent that if the children were to be speakers of Tolowa Dee-ni’, sending them to schools where English was the medium of educating was not an option. Schooling then extended the children’s Tolowa Dee-ni’ language and cultural foundation and identity to embrace academic learning in their home.

Homeschooling Teaching Strategies

The homeschooling space serves multiple functions. It is a language nest for early Tolowa Dee-ni’ learners and for adult learner-teachers, and it is a lab to pilot and test developing elementary Tolowa Dee-ni’ curriculum. Homeschooling demands that teachers are skilled in numerous language immersion methods, and in determining which strategy or activity to use in any given situation. One needs to be able to have a cache of lessons or activities that will engage students as their attention moves from one thing to the next. Ruby notes that she uses every method she knows about that promotes talking Tolowa Dee-ni’.

New vocabulary is introduced using ASLA language sets, then, to reinforce language use, Ruby uses immersion language teaching strategies. She reinforces learning with the 'five steps' where she introduces language to be learned, asks learners to listen as she says it, and then she asks learners to mimic her, putting off independent production until the end of the lesson. Ruby emphasizes that if you expect learners to speak too soon it sets up disappointment when they are unable to follow through.

Ruby and Pyuwa teach their children to be autonomous learners. One way is through using the Tolowa Dee-ni’ dictionary. Another way is using a word wall on which the children write a word in English that they want to know in Dee-ni’, and Ruby or Pyuwa add the Tolowa Dee-ni’ word next to it.

Teaching Activities

Ruby stresses learning through pair activities, where the children work together to find solutions to language ‘problems’, and through kinetic learning.

Kinetic Activities – Children Learn through Movement

taping a vocabulary word to a bowling pin. The children have to say the word on the pin as they roll the ball to knock the pin down;

beachball volley. Here the children throw a beachball (or other soft ball) back and forth to each other, saying the word taped to the ball. Two balls can be thrown at the same time, one ball with a noun taped to it and the other a verb;

an addition to volleying two balls after learning the words on each ball, is making a sentence using the two words.

Drawing – Ruby emphasizes that children need to take ownership of the language they are learning and, as a teacher, she needs to support them in that. She has had success with activities that allow children to create pictures and drawings with the language that they know.

The penny game – The Baldwin family created this game when their children were learning the Miami language. It positively reinforces language learning and use, and Ruby and Pyuwa have adapted it to learning Tolowa Dee-ni’. It goes like this: when you 'catch' someone using a Tolowa Dee-ni’ word, you give them a penny for using the word. It helps children recognize that what they are doing is a good thing and good things come from what they are learning. It also gets a little competitive and the children will inquire how to say new words so they can say them and add pennies to their jars.

Some Thoughts

Ruby stresses that being consistent in how one teaches and not giving up are two of the most important elements of teaching. The grind of creating curriculum and making sure you are meeting your own cultural standards as well as school standards can be demotivating, making you feel like you are not doing enough. Ruby reminds us that the biggest thing is to just keep going. When she feels she is losing motivation for teaching, she goes back to her own motivation goals for learning and teaching Tolowa Dee-ni’. She asks, ‘What is my motivation for doing this in the first place?’ And she answers, ‘Someone sacrificed for me to be here. Hearing the children using the language. Seeing them speaking to each other.’ Those are some of the personal motivations that keep her going.

In summary, you have to think about what motivates you from within. If your reasons for doing it are your own, if they come from within you, they will remotivate you to start again and continue the language work.

Case Study 7 Pigga KeskitaloRealizing Sámi Culturally Meaningful Education in the Classroom

Pigga Keskitalo is of Sámi origin, born in Finland in a small village in Nuorgam. She lived next to her grandmother’s farm, with extended family living nearby. She learned Sámi at home as both her parents were Sámi speaking. Ville Ásllat Piggá is her Sámi name according to her father’s father and means ‘daughter Piggá of Aslak of Ville’.

During her studies and her work in pre- and in-service teacher education, she has been interested in developing an Indigenous schooling system. Discussions with students and classroom teachers have focused on the need to organize teaching in a culturally meaningful way, and how to teach students so that they understand and can practice cultural traditions. An example of cultural traditions taught to primary school pupils includes smoking meat – here traditional knowledge is used to teach Sámi language concepts, and academic content about the physics of smoking meat.

We see that in ideal circumstances, successful teaching and Sámi learning are based on the values of the surrounding community,Footnote 20 which considers the elements of Sámi cultural well-being. Culturally sensitive teaching is achieved when Sámi education is grounded on the Sámi concepts of place, time, and knowledge.Footnote 21 In the old culture, the concept of time was sun-centered and bound to observing the nature. The Sámi conception of space is not bound to square feet, rather it is circular.Footnote 22 Sámi reindeer herding, like many other traditional livelihoods, is an example of how these concepts influence life, as herders function according to time-honored environmental practices that require ‘flexible’ thinking, meaning one’s ability to respond to one’s immediate environment.

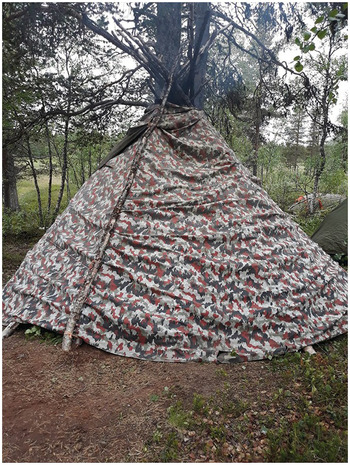

Sámi Dwelling Place – Goahti

In teaching arrangements, the Sámi conception of space would lead to a wider place of learning than the classroom. Information that pupils need also exists outside the school walls. The traditional Sámi dwelling place goahti is one example. The inner organization of the goahti can be applied to classroom organization, creating a more traditional Sámi school setting. A goahti has several physical areas where various tasks take place, with different people carrying out each task. When applied in a classroom, for example, a teacher could set up various teaching areas with individual tasks for student learning. The classroom would be divided into ‘posts’ with various work tasks that could be cultural and academic in nature, thereby transforming the usual classroom organization into one that represented a goahti, both physically and culturally. Widening hyper-traditional approaches may include teachers, elders, and others introducing new vocabulary. Sámi immersive teaching methods include doing traditional activities while using the language, like fishing and preparing food. In addition, suburban challenges are included, like taking into account the challenges of Indigenous peoples in suburban areas.

Case Study 8 Janne Underriner – When Full Immersion Is Not an Option in the Classroom What Can You Do to Stay in the Language?

Janne Underriner is a teacher of Chinuk Wawa, an Indigenous creole language of the Pacific Northwest.

We have seen in this chapter examples from teachers using language-learning strategies that support speaking Indigenous language in various contexts. Their common goal is to have learners using the language in daily settings outside of the classroom; engaged in day-to-day communication in the Indigenous language. In the Pacific Northwest, where for most communities it is not possible to provide language-rich learning environments with first language speakers, teaching language can be as much about strengthening learner’s self-esteem and providing a heightened awareness of culture, place, and history as it is about teaching language. Teaching may focus more on learning vocabulary and phrases for situations of cultural relevance through stories and song; teaching words and phrases that are used in religious ceremonies or while gathering food; or learning how to count living things from nonliving things.

For many Pacific Northwest Indigenous language teachers, teaching within a traditional immersion model where learning occurs for a day or half-day in the Indigenous language is not realistic. As we saw earlier, immersion teaching requires a high degree of fluency; higher than many teachers in this area have, so teachers are working to incorporate immersion teaching into their classrooms by presenting limited topics in which they have the ability to teach in the language for short periods of time. In the Pacific Northwest, most language teachers are typically language learners, younger adults who have a strong commitment to their language. Their challenge is to keep at least a step ahead of their students, providing a language-rich classroom environment within their own level of proficiency. Hinton suggests that a teacher who is learning her own language while she is teaching it focus on learning various components of a lesson. If a teacher learns the lesson elements – not only the new and review material presented in the lesson but also greetings, classroom management vocabulary, and informal patter – she can have an immersion classroom.Footnote 23

The benefits of using immersion techniques for a shorter time are available to less than fully fluent teachers. In these situations, immersion teaching calls for a strategy of beginning with using the Indigenous language in five, ten, fifteen-minute intervals and increasing from there. Teachers can use specific activities to stretch what they do know, for example, counting from 1 to 10 could be a ten-minute activity that maintained student’s interest throughout with song, humor, and physical movements. Or teaching about spring foods (roots) can include a traditional story taught in the dominant language using the Indigenous words for roots, colors, season, and place names. Learners can then use the language that they have learned in the classroom at their community celebrations and when they are root digging in their traditional gathering places. This teaching strategy nurtures authentic language use in everyday communication and traditional practices, meaning that it has immediate application for learners in their community.

Some Concluding Words

Our goal in writing this chapter was to share teaching methods and strategies that support language use. The hands-on activities highlighted show how learning can be accessible and support language use in daily life. Our experience has shown us that these activities motivate learning, bridge classroom and home learning, and bring language use into the community. We hope you will try these activities and that they enrich your teaching, and that, ultimately, you will experience similar results. Please feel free to contact any one of us.

15.1 Ka Hoʻōla ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi I O Nā Kula: Hawaiian Language Revitalization through Schooling

Hawaiian revitalization efforts currently focus on Hawaiian-medium education as an effective framework to reverse the demise of the marginalized Indigenous Hawaiian language and cultural identity. Using the Native Hawaiian language as the medium of education began with the founding of the ʻAha Pūnana Leo in 1983, a nonprofit education organization that established its first preschools in 1984–1985 for children aged three to five. These schools continue until today and are conducted five days a week throughout the school year, from 7:00 AM to 4:00 PM, where Hawaiian is the only language heard while education takes place. The ʻAha Pūnana Leo preschool children served as the impetus for the first HawaiʻiFootnote 24 Department of Education’s Hawaiian Language Immersion Program, started in 1987. Currently there are twenty-four Hawaiian immersion school sites in the Hawaiian Islands. In 2019 the Hawaiʻi public schools Hawaiian immersion program graduated its twentieth consecutive preschool (three to five years old) through twelfth grade high school (sixteen to seventeen years old), or P-12 Hawaiian immersion class since the first such Hawaiian immersion graduation cycle was achieved in 1999.

The term ‘Hawaiian immersion’ is now moving into ‘Hawaiian-medium’ education, where Hawaiʻi’s Indigenous language is more than just a ‘novel’ way of ‘immersing’ a child in a foreign language separate from a country’s mainstream language to conduct a child’s education. Hawaiian medium education utilizes the endangered, unconventional Native Hawaiian language totally as the language of instruction, interweaving the Indigenous Hawaiian cultural identity and rendering the Hawaiian language as the Hawaiian foundation to engage the world. This Hawaiian medium education philosophy establishes its own conventions of education, and in the case of Hawaiʻi, also achieving the educational standards of a mainstream English society.Footnote 25

Currently, the Hawaiian Language College, Ka Haka ʻUla O Keʻelikōlani, of the University of Hawaiʻi at the Hilo campus, serves as the major source for Hawaiian medium teacher certification and the College’s Hale Kuamoʻo Hawaiian Language Center develops Hawaiian medium curriculum resources for use in schools. The Hawaiian Language College offers a Bachelor’s degree in Hawaiian language as well as Master’s degrees in Hawaiian language and the state’s first Doctorate degree for the Revitalization of Hawaiian and Indigenous Language and Culture. These graduate degrees represent the first graduate degrees to be offered in the USA for any Indigenous language. So as Hawaiʻi now witnesses the death of its very last native speakers and the success of its Hawaiian immersion and Hawaiian medium P-12 programs, it is imperative that the College of Hawaiian Language continues to generate highly fluent second language speakers of Hawaiian focused on Hawaiian medium tertiary education.

Since the establishment of the ʻAha Pūnana Leo in 1983 for Hawaiʻi’s first Hawaiian language-medium Pūnana Leo preschools, thirty-six years of advancement in Hawaiian language-medium preschool to twelfth grade education into the public school system has resulted in unprecedented outcomes for Hawaiʻi. A standard of 100 percent high school graduation and 80 percent college entry rate for Hawaiian medium education students has been attained. These positive outcomes have uplifted the confidence and pride of a colonized minority Native population and have instilled achievable goals for the survival of the Hawaiian language and culture in its own homeland. Perhaps more significant has been the creation of highly fluent second language speaking parents who are now raising the new generation of Hawaiian first language speakers from the home. This sets the stage for further developments in formal Hawaiian-medium education that will continue to reach into the economic, social, legal, and political structures of society to regain the Hawaiian language and cultural identity’s rightful place in its own Native land while moving into the wider world.

15.2 Kristang Language Revitalization in Singapore under the Kodrah Kristang Initiative, 2016–Present

Kristang is an endangered Portuguese creole, once spoken in various forms across Southeast Asia from the seventeenth century. Today, it is spoken mostly by older speakers in Melaka, Malaysia, where the language arose after the Portuguese conquest of the city in 1511, and Singapore, whose Kristang community (today known as Portuguese-Eurasians) developed in the early nineteenth century following the establishment of a British trading outpost in 1819. The dominance of the English language in colonial and then independent Singapore, together with the perception of Kristang as ‘patois Portuguese’, ensured that by the late twentieth century, knowledge of the language’s very existence in Singapore was almost forgotten, even by younger Portuguese-Eurasians. Intergenerational transmission most likely ceased by the late 1960s, and the language is not taught in schools, or used in media or publications. As a result, it was estimated that, in 2015, less than 100 speakers of Kristang remained in Singapore.

Kodrah Kristang (‘Awaken, Kristang’) is a youth-led grassroots revitalization movement that started in March 2016 with a free pilot class for adult learners in Kristang following a year of documentation in Singapore. This first class was a collaboration between an older speaker involved in documentation who wanted the language preserved, and a younger Kristang learner who led the documentation effort. Successive rounds of this class were then developed into a full structured 160-hour curriculum based on Communicative Language Teaching and Task-Based Language Teaching principles (for more details see below). A thirty-year revitalization plan for the language, developed in 2016 at the Institute on Collaborative Language Research (CoLang) at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, also informed the development of the curriculum. This plan is divided into five phases: Prendeh (‘Learning’: 2016–2017), Abrasah (‘Embracing’: 2017–2018), Alkansah (‘Achieving’: 2018–2021), Kriseh (‘Increasing’: 2021–2035), and Subih (‘Elevating’: 2035–2045). Ultimately, the plan seeks to redevelop space for Kristang in the Singaporean home, whether Portuguese-Eurasian or otherwise, and invite, encourage, and sustain community ownership in the revitalization of the language.

The Kodrah Kristang initiative focuses on outreach and collaboration, building a broad base of contacts while maintaining a strong focus on attracting young people and ensuring that the effort is grassroots/community-oriented and low-cost. Kodrah’s youth-led core team is multiethnic, with only two out of five of the present team being of Portuguese-Eurasian descent. Classes are open to anyone of any ethnicity, not just Portuguese-Eurasians. This is due to the initiative’s urban context, the small size of the Portuguese-Eurasian community (about 0.4 percent of the population, or 16,000 individuals), and strong sensitivities in Singaporean society and the Singapore Eurasian community about language and race. The core team continues to work with remaining Kristang speakers to deliver lessons, with a (younger) core team member leading classes from the front and one or more Kristang speakers usually present among the students to provide feedback and support. Lessons are structured almost entirely around games and interactive activities to facilitate the growth of a new Kristang-speaking community founded on strong interpersonal relationships.

All classes and class-related materials are free, as the initiative has cultivated a system of reusable long-term capital and strong relationships with venue partners to reduce financial barriers to long-term sustainability. Broadly speaking, most class activities make use of common household items and games (e.g. poker cards, dice, rough paper) that cost little and can be reused as long-term capital. Slides are uploaded online so printing is left to the individual learner’s discretion. The team makes use of a small amount of funds accumulated from the Kristang Language Festival in 2017 (see below) and sales of Kristang dictionaries and games fund the printing of some worksheets and purchasing of long-term capital such as dice and cards. Meanwhile the current Core Team are all registered People’s Association (PA) trainers in Singapore, which allows them to run classes at any community center in Singapore for a very minimal fee.

As of May 2019, about 280 individuals, including 15 children of various ages, have completed the entry-level Kodrah 1A course and the associated ALKAS assessment, a diagnostic tool developed to determine learners’ progress after two modules. Thirty students from the pioneer group in July 2016 completed the first round of highest-level 4A and 4B courses in November 2018. Meanwhile wider public outreach has been extensive, with the initiative nominated for the prestigious Singapore President’s Volunteer and Philanthropy Award in 2017 and 2018, for demonstrating Kampong Spirit. Other initiatives include a pilot children’s class in July 2017 and the successful launch of the first Kristang Language Festival, held in May 2017 and attended by over 1,400 individuals. A number of Kodrah students have independently initiated projects of their own featuring Kristang, including a film (Nina Boboi), a graphic novel (Boka di Stori), a children’s book series, and a Massive Multiplayer Online Roleplaying Game (MMORPG). These are not part of the revitalization plan but have seen significant support from both the Eurasian community and wider Singaporean society; Nina Boboi featured on the online streaming service Toggle and the graphic novel Boka di Stori was funded by a Yale-NUS Futures of Our Pasts grant.

15.3 Teaching and Learning of Wymysiöeryś

As a child I was obsessed with thinking about what would happen if the native speakers of my language died out. When I was ten, the youngest of them were over seventy years old, so I realized that it would unfortunately come fast. Then I would be alone in Wilamowice as if in a fremd (foreign) place.

I knew that the only way to change this situation was to teach my friends. At that time, they would rather tease me than show an interest in learning Wymysiöeryś. As I was thinking about how to deal with it, I discovered that lessons in Wymysiöeryś were to be organized at the school, led by an old Vilamovian – Józef Gara fum Tołer. He taught a few children, but unfortunately, because of his age (he was about eighty), he could not do it for long. Then, after two years, the lessons stopped. It was the year 2006. I thought that may be the time spent teaching children, who do not learn much, could be better spent recording the last living native speakers and undertaking language documentation.

Then, in 2011, I decided to start teaching the language. I thought about focusing on documentation, but I realized that I did not want to feel guilty that I kept the new generation of speakers from knowing the old native speakers. The first group were children from the Dance Group ‘Wilamowice’, then came their friends and I had to organize a couple of groups at different levels. They did their homework with the Wymysiöeryś native speakers: they helped them with housework while speaking Wymysiöeryś together. The old people are often alone, so they were very happy to have guests who were young and interested in their language and in their life stories.

There were years when I had about twelve groups and I taught about twenty-four hours per week. In 2011 I was eighteen, so my workload included preparation for the secondary school exit exams and then university, where I also had many exams. My parents did not like that I would spend more time teaching than learning and I failed my university exams twice. For them and for some friends of mine it was a big tragedy and they could not understand why I kept teaching children and teens who would sometimes stop learning or not treat me well: what if nobody wanted to continue? But I knew that it was the price and the risk that we as Indigenous people take every day. That was not the only decision that I took in 2011. I was thinking every day that while there were many children here who stopped learning, there were also many academics who abandoned their activities in Wilamowice, because they felt dissatisfied with their effectiveness. For example, some people wanted to start projects, but then they realized that their work would remain unknown, or that there are too few native speakers, or that young people do not speak in the same way as before World War II, or that this town is too small for them and they cannot spend a couple of months here because of the lack of entertainment. So why should I believe more in scholars than in my pupils?

There were many moments when I was in doubt, but now, I see my students writing poems and songs, playing in theatrical performances in Wymysiöeryś, teaching other children, speaking Wymysiöeryś with each other, using it on Facebook and creating websites about Wymysiöeryś. I can confirm for people who are thinking about taking a similar decision, that I do not regret it. I remember all the moments of doubt, but I know that this is the price that we, as locals, have to pay and nobody can do it for us. We are grateful for help from the universities in Warsaw and Poznan in preparing teaching materials and negotiating with local authorities, but organizing things on an everyday basis, teaching and as looking for new students, are all up to us.

15.4 Immersive Łemko Ethnophilology

Łemko ethnophilology was a degree course at the Pedagogical University of Kraków between 2001 and 2017. This program was needed because the Lemko training had been available only at the level of primary and high school and there was not space to prepare Łemko teachers and Łemko intelligentsia. It was closed because of standardized majority criteria for university programs: The university authorities decided there were not enough participants, whereas the recruitment rules were not adjusted to the specific situation of an ethnic minority. It was the only higher education course in Poland designed to prepare students for using the Łemko language in the public spaces and domains where minority languages are used in Poland, i.e. teaching, journalism, cultural animation, social work, research.

Students learned through common creative activities. During group and individual work they created texts in Łemko. These are published in a special section of Łemko newspapers and include book reviews as well as reports about Łemko events. The students participated not only in classes but also in journalism and music workshops. They also took part in linguistic and cultural practices in various places where Łemkos live and learn. This means that the development of their Łemko training was also shaped by the local socio-political and cultural life of this minority community. Students also had teaching practice in schools where Łemko is taught and during summer camps for Łemko youth. The most important part of these activities was the emphasis on their social meaning and social utility. The positive, family-like emotions they felt while learning creatively in Łemko-language situations reinforced their language awareness and learning.

A very important achievement of this program was the originality of the teaching method, which meets the needs of members of minority language communities and cultures. The main feature of this method was full immersion from the very start. It was possible because the lecturers were native users of Łemko who uphold Łemko customs in their private and social lives. Those students who were brought up knowing the Łemko language and culture provided important support for new speakers. Their innate knowledge of the domains of language and culture had positive impact on all the students – including those who had never had any contact with Łemko before. Working in such a diverse group of people is most effective as it shapes immersion dynamically and creates a special communicative and emotional sensitivity. If there are no native speakers in the group (and it happens), contact with the broadest possible range of students and Łemko youth is needed. This should happen in an environment where cultural and linguistic patterns of behavior are continued. Such emerging relationships among students bring about good results in the domains of information and emotion (and this is a priority when it comes to minority languages) as they motivate learning through approval – like in family relations. Students who aren’t Łemkos are symbolically introduced into the family as they obtain their Łemko names and acquire the community language. This makes them feel special but also creates an obligation for them with regard to the language and its transmission. Students who are native speakers of Łemko are put in the position of teachers and supervisors. They also become aware of the mechanisms how the language is passed down in family environment along a number of contexts of its use and what is special about it. All this helps them have the confidence to use it in public spaces. The alumni of the Łemko ethnophilology course are among the most engaged revitalizers of the Łemko language and traditions (Figure 15.4.1).

Figure 15.4.1 A presentation of Łemko books by Olena Duć-Fajfer, the founder of the Łemko philology, and Petro Murianka, a Łemko poet, writer, and teacher.

15.5 Culture Place-Based Language Basketry Curriculum at the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community

Place-based learning has emerged in Indigenous communities as a promising approach for language learning, revitalization, and maintenance. Place-based education has links to communicative and culturally based approaches. With community at the center, students learn about core values, culture, their homelands, their people’s history, and current tribal affairs as they learn their language. Students become connected to what is essential to their tribal community and to the ways of their ancestors. It also links students with members of their larger, not just tribal, community who contribute to its diverseness, and in so doing it opens students’ awareness to elders, leaders, mentors, and peers they might not have encountered in a more teacher-centered classroom learning experience. ‘Diverseness’ means that students learn about people in their community; they learn about jobs and what people do; they learn about their government and the departments in their government. Students drive learning as much as teachers.

Place-based education supports recommendations of Indigenous educators for Indigenous students. Place-based education meets the call for the integration of the local and the inclusion of cultural knowledge in teaching, as well as increased involvement by the community. Incorporating culture into learning affords the opportunity for students to participate in traditional practices of the community today, linking the past to the present. In addition, culture place-based language learning builds identity and connection to surroundings. By design, it is collaborative and cultivates relationship building. It is experiential and so nurtures learners’ curiosity, builds cooperation among students, and strengthens problem-solving abilities.

A culture place-based learning approach positions curriculum and lessons in local events and places, and acknowledges that learning happens not only in formal educational settings but also outside of school in families and communities. This reinforces connections to one’s home, family, community, and world. Included components can be the cultural, historical, social, religious, and/or economic relevance of specific locations or regions.Footnote 26

Culture place-based learning supports communicative language use as students work together on projects to investigate and understand the world at large. Here, for example, they use learned skills to make observations, collect data, and interview community members to carry out a group learning task. At the end of a project they disseminate the result in presentations at school and to community groups. Cooperation and communication are essential throughout the process, and team members learn to respect each other’s views and contributions.

Since 2000, I have been a member of the curriculum team at the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community (CTGR) in Grand Ronde, Oregon in the United States. We have been writing culture place-based curriculum for their preschool, elementary, and high-school Chinuk Wawa immersion classroom where students three to ten and thirteen to seventeen years of age receive instruction. Our goal has been to create lessons that will promote learning, foster curiosity, and develop the connection to community. And they must be written and taught in ways that inspire learners to want to learn more.

Initially, a curriculum team (teachers, elders, curriculum writers, linguists, science, language arts teachers, community cultural specialists, parents) brainstorms ideas, and develops a topical curriculum web that provides interrelated themes, language needed, the sequence of what will be taught, and accompanying materials and resources (people as well as objects). Throughout, culture place-based objectives are incorporated into academic standards that meet school district requirements.

In developing culture place-based curriculum, we begin with:

(1) Curricular topic idea that comes from teachers, students, a member of the community, and parents, for example, ‘basketry’. From a topic,

(2) Thematic units are determined and created; one could be material resources for basket-making: cedar basketry, hazel basketry, juncus basketry (plant resources). Or a unit could center on basket types (function) – for root digging, storage, holding water, for cooking. Another unit can center on basketry patterns. After units are determined we develop

(3) Lessons and materials

Here are some other topic examples:

traditional lifeways (basketry, canoe making, digging roots) – each of these can be its own topic as seen above with basketry

animals (beaver, elk, deer, condor)

roots (celery, camas)

fish (salmon)

berries (huckleberry, salal)

acorns

canoes

land

An example of a place-based curriculum is the project Basketry: Place, Community, and Voices, a multidisciplinary, year-long unit. The project emerged from parent‒community Chinuk Wawa language curriculum meetings. For decades, adult basketry-making classes/workshops have occurred year-round in Grand Ronde. Now parents wanted their children to learn about basket-making and initiated that classes be taught in the schools. Specifically parents and teachers wanted students to:

understand that baskets are an important part of Grand Ronde culture

know that juncus and hazel are used in creating traditional baskets

identify different weaving materials in situ and in class

be able to talk about weaving processes in both Chinuk Wawa and English

weave different types of baskets with these materials.

Curricula meet Oregon State standards in math, science, social studies, history, art, and literary arts. Some examples of preschool – fifth-grade lessons include:

(1) Math – counting weavers; Geometric basket designs; Estimation; Even and odd numbers.

(2) Social Studies and History – Use of baskets and basket weavers past and present; Influence of outside communities.

(3) Stories and Literature – Hattie Hudson – a story of a past elder basket weaver.

(4) We Go Gather – a story about giving back to nature when taking from it.

(5) Science – Where, when, and how to harvest; Charring sticks for bark removal; Best management practices for guaranteeing future harvests; Processing materials; Qualities of good basketry materials; Experimenting with materials.

In workshops, specific basketry skills are targeted, so a year’s curriculum can be taught in four or five intensive workshops. In schools, the curriculum is year-long and follows the seasons and time of year when gathering, processing, and weaving are carried out traditionally. For example, hazel is collected in the spring when sap is running throughout the plant. This is climate dependent, so one year it could occur in March, another year could be earlier or later. Learners travel to areas in their community on the Reservation to gather it. They begin weaving in the late spring and summer (also in the fall and winter) after hazel sticks have been prepared. In the summer and early fall, they use hazel baskets to gather berries, and in the early spring in digging roots. Winter lessons include learning basketry stories as traditional stories are told after the first freeze, learning gathering and digging songs and prayers, and learning basketry patterns. Each season learners are taught how to identify hazel in its environment, and how to care for it.

In developing curricular products, we considered those that would benefit the school and the community in general. Thus materials that resulted from the project serve various learner groups. Materials were made by students, parent and family members, basket weavers in the community, teachers, and the curriculum team and include: a multidisciplinary, twenty lesson year-long unit on hazel and juncus basketry of the Grand Ronde people; story, material processing, and pictorial books; and workshop videos.

Summing up, we find that culture place-based curriculum engages youth and children in learning their language in culturally appropriate ways. It builds relationships among mentors and youth, and supports older children to be role models for younger children. We experienced first-hand that a strength of culture place-based curriculum is that it is collaborative and local. It supports the understanding of plant materials, and traditional uses and practices of basketry. This aids in developing better natural resource management practices on tribal, private, and national forest lands. The curriculum informs learners about the health of the environment and land.

We see that learners, young and older, from traditional and nontraditional homes, are more willing to participate in community events at their tribal gym, longhouse/plankhouse (places where ceremony is practiced), and on reservation land (gathering natural resources for weaving, for example) because the curriculum familiarizes learners with traditional and community practices – learning holds at its center the values and traditions (past and present) of its elders, families, learners, and community members. In this way culture place-based learning offers an opportunity for community centered learning that promotes learners’ well-being.

15.6 Sámi School Education and Cultural Environmentally Based Curriculum

In 1997, a separate Sámi School was established in Norway. It follows the principles of the Sámi curriculum in the district area of the Sámi language, emphasizing the importance of bilingualism and the improvement of the status of this Indigenous language after it became officially recognized in the Sámi administrative district in 1990.

Ideally, teaching should be sensitive to the cultural values of the surrounding community. The Sámi curriculum has been developed by working groups including Sámi representatives. This model is based on cultural sensitivity and multilingualism.

Culturally sensitive teaching goals are fulfilled when Sámi education is grounded in Sámi conceptions of place, time, and knowledge (as discussed in Case Study 7 in this chapter). In Sámi culture, the concept of space is circular. Time is sun-centered and bound to observing nature. As a result, teaching takes into account the Sámi understanding of time by organizing classes in a more flexible way and giving up the forty-five-minute scheduling typical for school culture. In addition, the eight Sámi seasons are respected by considering the livelihoods and seasonal work of the Sámi. Traditional local knowledge and linguistic concepts are also included in the learning process.

Learning centered around Sámi values guides students and helps them to understand the social connections of community, their surroundings and nature. Teaching also has to include learning about flora and fauna and should reveal the strong connections between people and nature. Sámi traditional knowledge is derived directly from the environment where people live: concrete working situations and cottages, lean-to shelters, and campfires function as venues for a type of scientific seminar, as discussions are held there and traditional knowledge spreads. Culture-based learning is achieved through storytelling, conversations, and direct participation in these activities, as well as recalled memories and experiences. When applied in the school context, it means that knowledge is a shared experience, which has at its foundation an ecological approach. Thus, education connects to every area of Sámi life, and promotes pupils’ well-being and their links to the environment and land. Building on the school educational context, community members, parents, and elders also help children to recognize and incorporate traditional upbringing practices and working methods (Figure 15.6.1).

Figure 15.6.1 A girl in a gákti (traditional Sámi dress).