INTRODUCTION

In March 1939, the British section of the Comité mondial des femmes contre la guerre et le fascisme (CMF) used its journal, Woman To-day, to appeal to members to contribute to its most recent campaign: a child sponsorship initiative for Chinese children orphaned by the Second Sino-Japanese War. To convince readers to donate, the journal stressed the increasingly globalized world in which they were living:

China – so far away, people say – what has it to do with us? That may have been so many years ago, but to-day China is near us and so are her people. (Charlotte Haldane, Special Delegate to China from the Women's Committee for Peace and Democracy, flew from London to Hong Kong in five and a half days.)Footnote 1

The CMF endeavoured to forge connections and collaboration between the Western European centre of operations and the rest of the world in the 1930s. A communist, anti-fascist organization targeting women, the CMF viewed the expansion of women's activism into Africa, Asia, and the Americas as integral to the success of its mission. As such, the carnage of the Second Sino-Japanese War and its impact on women and children drew the committee's attention. Estimates of Chinese casualties in the war vary from fifteen to twenty million, occurring alongside an internal refugee crisis on an unprecedented scale as tens of millions of civilians were forced from their homes.Footnote 2 In many cases, women and children were the focus of aggression from the invading Japanese troops: the most infamous example of this aggression was the massacre in Nanjing over the winter of 1937/38, in which Chinese estimates state that 300,000 civilians were murdered and as many as 80,000 women and girls were raped.Footnote 3 The overwhelmingly gendered nature of the violence and its impact on children was the main concern of the CMF.

The first section of this article will consider how imperialist rhetoric clashed with feminism in CMF work, as it invoked stereotypical depictions of Chinese women as quiet, stoic mothers, while simultaneously allowing Chinese women a platform through which to dispel these assumptions and articulate their experiences. In addition, there were frank discussions of the mass rape that they experienced, but no attempts to construct a feminist strategy to confront it. In the second part of this article, I will discuss how the CMF utilized maternalist rhetoric to forge connections between Western and Chinese women as a humanitarian strategy, which often ignored the nationalist priorities of the Chinese population. Third, I will examine how the CMF used the concept of child sponsorship to fundraise for children orphaned by the war, known colloquially as “Warphans” in the press. The “Warphans” campaign was also gendered along traditional, Western lines to encourage women as (potential) mothers to contribute, as well as employing violent language to create a short but successful humanitarian campaign.

Before the globalization of women's activism, which occurred in the post-1945 period, exemplified by organizations such as the Women's International Democratic Federation (WIDF, which Mercedes Yusta has presented as a successor to the CMF), CMF activists were actively facilitating processes of mobility and exchange across borders, in this case between Western Europe and China.Footnote 4 The CMF's China campaign bore clear similarities with the WIDF's mission to North Korea in 1951 as socialist women activists travelled to a nation that was devastated by war and experiencing a vast refugee crisis. Celia Donert has argued that WIDF used “maternalist language to legitimate women's ‘independent’ role as observers in conflict” and graphic descriptions of violence against women and children in its report on the Korean conflict, both of which were key tactics in the CMF's work in China.Footnote 5

This article will be the first study on how the CMF conducted its campaigns; there has not been much examination of the CMF in the historical literature, and what has been written has tended to give a surface level overview of the committee without examining its processes or its campaigns on issues faced by women across the globe.Footnote 6 This article rectifies this gap in the literature, as it offers new opportunities through which to study the practice of women's socialist activism on a global scale in the 1930s. It will highlight processes of information exchange and the contradictions inherent in them to demonstrate that, while Chinese women gained an international voice by publicizing their struggle in CMF spaces, colonialist tropes, maternalist language, and a certain infantilization of the Chinese people were invoked to stimulate sympathy despite the committee's ideological and political positions.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE COMITÉ MONDIAL DES FEMMES CONTRE LA GUERRE ET LE FASCISME

Formed in 1934, in Paris, the Comité mondial des femmes contre la guerre et le fascisme was an international communist front organization that provided communists with new opportunities to reach working-class women who were heavily underrepresented in their parties. To take one example, the Parti communiste français had a female membership of just 200 in 1929, totalling 0.6 per cent of its members.Footnote 7 The CMF was created, in part, as an attempt to shift this imbalance by engaging with women deemed prime for political conversion to communism: socialists; Labour Party women; left-leaning non-party women; intellectuals; and working women in particular. However, this desire to attract non-communist women to the committee served another purpose. The CMF publicly declared itself to be above parties and was therefore used by the Comintern to test the Popular Front strategy of collaboration between parties on the left before adopting it as official policy. Like its sibling organization, the Amsterdam-Pleyel movement, the CMF was developed to discover whether left-wing activists could pool their strengths and coordinate actions against the threat of fascism effectively, despite the conflicts that had ravaged the left after 1917. This policy achieved some success in attracting socialist women to work with communist women in the CMF. Most notably, the Belgian socialist women's leader, Isabelle Blume, led the Belgian national section in tandem with the communist municipal councillor, Marcelle Leroy. However, continued concerns about communist influence on the CMF prevented it from becoming a fully effective Popular Front movement.

The CMF aimed to unite women from across the globe against fascism and imperialism and tried to reconcile the conflict between socialism and “bourgeois” feminism that had raged since the late nineteenth century. It differed from larger international women's organizations, including the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) and the International Council of Women, for two key reasons: first, it was deeply influenced by the politics of communist internationalism and second, it did not oppose warfare in the quest for national independence, communist revolution, or defeating fascism. It offered socialist women an avenue through which to work with feminists and utilized the “rhetoric of internationalism” (to borrow from June Hannam and Karen Hunt), specifically anti-fascist internationalism, to encourage feminist women to eschew their reservations about the influence of communism on the committee.Footnote 8 The CMF's approach to gender was complex, as the group simultaneously espoused maternalist conceptions of women's role in the home and championed women's right to work by necessity or choice. Further, it celebrated those women who took up arms in the fight against fascism and war and supported traditional feminist demands, including the fight for women's suffrage.

In its short lifetime (it disbanded circa 1940), the CMF had representatives and national committees on every continent, all of whom were committed to confronting the threat of the far right, to developing the socialist consciousness of working women in their own countries, and to creating an organization that united women from “all points of the earth” against a common enemy.Footnote 9 The International Executive Committee of the CMF was based in Paris and the group's largest national section was the French group; by March 1937, the French section totalled 200,000 women in 2,000 local committees and contributed to and organized events on a variety of topics, from strikes to women's enfranchisement.Footnote 10 It also had substantial support in Belgium and amongst German and Italian refugees.

The CMF was led by women who held important roles in the international communist and international feminist movements. Of particular importance here is Charlotte Haldane, the leader of the British section of the CMF, whose visit to China in 1938 made her an important witness to the suffering faced by Chinese civilians during the war. Haldane was a journalist for the Daily Express newspaper in the 1920s and published the dystopian science fiction novel Man's World in 1926. By 1927, Haldane had joined the communist party; she organized volunteers for the International Brigades in Paris for the Comintern and acted as a guide for important people who toured Spain during the Civil War, including the American entertainer Paul Robeson. She was charged with visiting China by the CMF and the Comintern, but her role extended beyond being a communist delegate; she also represented the China Campaign Committee, was a special correspondent in China for the Daily Herald, and relayed letters and sentiments to the Chinese leadership from Clement Attlee and Archibald Sinclair, leaders of the Labour Party and Liberal Party in Britain, respectively. She also published a report on the “situation in China and the Far East” for the House of Commons on her return to Britain.Footnote 11 Haldane's connections with major politicians and newspapers despite her communism were significant and provided a greater sense of legitimacy to her work for Chinese women and children.

The CMF Executive Committee was primarily concerned with the threat that fascism and war posed to women and children. It organized aid and information campaigns based on the experiences of women in the Spanish Civil War, Nazi Germany, and during the Italian invasion of Abyssinia by employing a dichotomous discourse that positioned women as either the caring mother or the masculinized fighter, with little overlap between the two. For a committee that publicized and attempted to alleviate the impact of war and fascism-related violence on women, the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) was a source of anxiety that mobilized them to consider new strategies to ameliorate the situation of their Chinese “sisters” and their children.

THE CONTRIBUTIONS AND CONSTRUCTION(S) OF CHINESE WOMEN IN CMF DISCOURSE

The personal experiences of Chinese women during the war were integral to CMF efforts to raise consciousness about Japanese aggression in China. The committee worked with various Chinese women to stimulate strong enough bonds of “sisterhood” and sympathy across borders to pledge donations of money, food, or clothing. It gave Chinese women the opportunity to speak for themselves and to recount their experiences in graphic detail. Of particular importance, the committee provided a space for discussion of the mass rapes perpetrated by Japanese soldiers on Chinese women. Rape has been a feature of warfare for millennia, but it became more apparent in the public consciousness with the widespread sexual assault of French and Belgian women by German soldiers during World War I. However, contemporary propaganda discourses on the “Rape of Belgium”, as this event has become known, tended to conflate the violated female body with the nation, minimizing the personal trauma of women who had been the target of these attacks as a result.Footnote 12 The CMF, however, blended its socialist feminism and internationalism to highlight the real impact of sexual trauma during wartime on its female victims and their children in its humanitarian propaganda.

The Nanjing Massacre in late 1937 was the subject of a speech given by a Chinese sociology student, Loh Tsei, at the CMF's Marseille Congress in 1938 (Figure 1). She had gained a reputation as “China's Joan of Arc” in the American press for her role in the Chinese student movement and was particularly well-known for her contribution to the demonstration against Japanese imperialism that took place on 16 December 1935 in Beijing, during which she opened a gate to allow between 2,500 and 8,000 students to join the protest.Footnote 13 Arrested and “beaten with gun butts”, she became a leader in the Chinese student movement after her release and was sent to Europe and the United States to advocate for support.Footnote 14

Figure 1. Loh Tsei, the Chinese student activist, photographed by Carl Van Vechten in New York on 16 September 1939. Labelled as China's “Joan of Arc” by the press during her propaganda tours of America, she was a key figure in the December 9th student movement in 1935. I thank the Carl Van Vechten Trust for kindly giving me permission to use the image in this article. Carl Van Vechten / Beinecke Library, ©Van Vechten Trust.

Loh Tsei spoke graphically about the Nanjing massacre, in which Chinese women suffered “humiliations which exceed the imaginations of civilized peoples”. In a “moving” speech, Loh Tsei told of how “Japanese soldiers […] search from house to house for all the women and inflict a terrible fate on them: raped, tortured, sometimes almost killed”, with husbands shot if they tried to help their wives.Footnote 15 She utilized emotive and violent language to expose the horrors of the massacre, citing a missionary who wrote that he had seen a woman in the hospital who “had been raped twenty times” and whose head the Japanese soldiers had attempted to remove, “resulting in a serious throat injury”. Tsei stated that “100 cases of rape” at the University of Nanking were reported in just one night, including two girls of eleven and twelve years of age.Footnote 16 She utilized this language not only to report the incidents of violence towards Chinese women accurately, but also to induce a response in the women who were listening in person and who read the congress report; it was intended to create a sense of horror among the audience, which would propel them to act on behalf of the victims.

The kidnapping of Chinese women by Japanese soldiers was similarly highlighted by the CMF during its humanitarian activism. During the “Warphans” campaign (which will be explored in detail later in the article), the committee revealed that some of the children orphaned by the Second Sino-Japanese War had witnessed a particularly gendered, violent attack on their families, in that they saw their mothers kidnapped (and sometimes killed) by Japanese soldiers. Japanese soldiers kidnapped Chinese women, girls, elderly, and pregnant women frequently during the Second Sino-Japanese War to rape, use as sex slaves, or to force them to work in “comfort stations” established for institutional sexual slavery. The first official “comfort station” was established in Shanghai in 1932 shortly after the Japanese invasion of Manchuria.Footnote 17 Chinese women were not only targeted for mass sexual violence because of the sexual deviancy of the Japanese forces, but also because they represented the “body of the nation” and rape stood as a “gesture of conquest”, as Belgian women had been twenty years earlier.Footnote 18

By March 1939, Western observers would have known, to some extent, that mass sexual violence was occurring in China. However, it is not clear how far CMF members would have understood the subtext of rape in the description of mothers being “abducted” or “taken away” by Japanese soldiers. However, the result was still horrifying, even if readers of Loh Tsei's report did not fully understand that the kidnap of Chinese women ultimately meant their sexual assault. In addition, an article in the CMF's French journal, Femmes dans l'action mondiale, profiled four Chinese children who had seen the kidnap and murder of their mother by Japanese soldiers, demonstrating the extreme violence that the children had witnessed. It also suggests that the children interviewed for this article had witnessed the entire attack on their mother, from kidnap to rape and murder, a fact that some of the more informed readers would have understood and that may have encouraged them to act out of horror and sympathy for the children.Footnote 19

However, the committee's discourse on sexual violence had several limitations. Although it publicized a traumatic and often overlooked aspect of war and gave Chinese women the opportunity to discuss it on their terms, the group used these descriptions of gender-based atrocities entirely as propaganda for its humanitarian work. It did not engage with feminist politics to examine the motivations behind these atrocities or to suggest solutions, nor did it collaborate with other international groups on campaigns on civilian protection. Beyond some participation in women's delegations to the League of Nations and cooperation with organizations in a national context, the CMF tended to work unilaterally. Despite the group's resolute commitment to exposing all the horrors of the war between China and Japan, in practice its frank portrayal of sexual assault served little purpose other than consciousness-raising amongst Western women.

The involvement of several Chinese women provided a sense of legitimacy and ensured the international character of CMF work. The most renowned name attached to CMF work in China was Soong Ching-ling. As the wife of the first President of the Republic of China, Sun Yat-sen, and an important figure in Chinese politics in her own right (including being named the Honorary President of the People's Republic of China shortly before her death in 1981), Soong had broken with the nationalist Kuomintang party in 1927 after its leader, Chiang Kai-shek, expelled communists from the party and ordered the slaughter of “thousands” of communist cadres in Shanghai.Footnote 20 In 1927, she spent a few months in Moscow and Berlin, making contact with representatives of the Comintern through whom, it is likely, she became involved with the CMF. She held a position on the Comité d'honneur for the group's founding congress in 1934, although neither she, nor any other Chinese delegate attended the meeting in person.Footnote 21 Her involvement lent legitimacy to the success of CMF work; for example, the Cantonese pottery that she provided for the CMF's China Bazaar in the winter of 1938 raised £400 to send to the Chinese International Hospital.Footnote 22 When Charlotte Haldane travelled to China under the auspices of the Comintern, Soong Ching-ling travelled from her home in Hong Kong to Canton (Guangzhou) to meet her, demonstrating a personal commitment to the CMF. The two had “several long and intimate talks” about the Sovietization of China and Soong's concerns about the growing “fascist” nature of the Kuomintang under Chiang's leadership.Footnote 23 These discussions were not published at the time, with the committee focusing entirely on the threat of Japanese imperialism and ignoring the internal conflicts of the Chinese nationalist movement in its publications.

Depictions of Chinese women's experiences during the war in CMF journals often reinforced the Western stereotype of Chinese women as having “little or no freedom”, which had, by the interwar period, transformed into a “more complete political and social freedom than any country in the world excepting the Soviet Union”. Charlotte Haldane, for example, emphasized the contribution of women to the war effort with their “unsurpassed record for physical valour and courage”, evidenced by the “Chinese Florence Nightingales, Joan of Arcs, Judiths, Boadiceas, and Nurse Cavels by the dozen”. However, even here Haldane described Chinese women as serene and unassuming, performing their valiant actions with a “quiet ‘take it for granted, it's all in the day's work’ type of heroism”. She also made claims that were disputed by Chinese women themselves. Haldane asserted that the Second Sino-Japanese War had “hastened the development [of Chinese women's rights] which began in 1919”, while some Chinese communist women writing for a Chinese audience claimed the opposite; for example, Pan Yihong cited Jun Hui, a member of the Chinese Communist Party, who argued that the men “responsible for defending the country” had established “tighter supervision and control over women's every move” alongside their withdrawal in the face of Japanese troops.Footnote 24

The height of women's emancipation in China had come in the mid-1920s, as some Chinese women adopted the image of the emancipated “New Woman” in terms of style and political engagement. Women from the Kuomintang and revolutionary parties alike worked to encourage peasant women to engage with politics, and some women began to crop their hair into bobs and wear masculine clothes. However, in April 1927 the Kuomintang turned against revolutionary parties, including feminists; some women with bobbed hair were persecuted or even killed as they “symbolized a liberated woman”.Footnote 25 Concurrently, the dual conflicts between the nationalists and the communists, and between China and Japan, made women's emancipation less of a priority than the emancipation of the nation. It is important to note that “party-political cleavage was never a defining feature of elite women's public communication and engagement in the 1930s” in China, as women's groups formed a “united front” to fight for national salvation, regardless of party.Footnote 26

Still, this desire for national sovereignty clashed with the main principles of international women's organizations. Many non-Western women supported military action to achieve independence, which was inherently at odds with the total pacifism of the largest women's groups. Mona Siegal has identified “feminist orientalism” on the part of Western women activists, the “recalcitrant nationalism” of Chinese women, “differing understandings of war and political violence, and the relationship of each to feminism” as barriers to collaboration between the WILPF and Chinese women in the interwar period.Footnote 27 However, these factors did not present much of an impediment to collaboration between the CMF and Chinese women; although there were orientalist and nationalist aspects to CMF work on China, it by no means negatively impacted the extent to which women from one group cooperated with women from the other. Further, Chinese women and the CMF shared a much closer understanding of the use of warfare than the WILPF did, as the CMF actively encouraged violent struggle against fascism and imperialism and for revolutionary purposes. Thus, the CMF's Chinese campaign had an integral consonance and alignment of philosophies that was lacking in previous associations between Chinese women and international women's groups.

MOTHERHOOD AS A MARKER OF SOLIDARITY

Western writers also heavily relied on essentialist tropes of motherhood to simulate bonds between women separated both by geographical space and by cultural differences. Harriet Hyman Alonso has argued that women did not have to be mothers because “just possessing the proper biology or the emotional capacity to ‘mother’” was enough.Footnote 28 Moreover, contemporary feminists argued that women could understand emotions, show compassion, and “envision peace” better than their male counterparts because of their maternal instinct to nurture. It was one of the dominant discourses in twentieth-century feminism, socialist or otherwise, as the potential for motherhood represented one of the few characteristics shared by women across the globe. The CMF's appeals to women as mothers were therefore part of a longer tradition of maternalism as a feminist strategy. For example, Marie Hoheisel argued in the International Council of Women Bulletin that the “power to mother the world was inherent in all women, whether or not they had borne a child”, and groups like the WILPF “embraced maternalist rhetoric to advance a pacifist agenda and claim a place for women on the global stage”.Footnote 29 Maternal language was used to generate “a sense of global affinity among women and mothers” by international socialist women's organizations in the post-war period, too. For example, activism by the Women's International Democratic Federation (WIDF) in North Korea, Vietnam, and Chile employed maternalist rhetoric as an “important mobilising function” amongst women.Footnote 30 The CMF sat somewhere between these two strands of feminist thought, both chronologically and politically.

The CMF strategy of representing women suffering under fascism or war as either mothers or fighters aimed to create emotional solidarity and “sisterhood” across borders that were otherwise difficult to traverse. This was clear in many of the committee's international campaigns: female fighters were masculinized and an abstract figure of aspiration (seen most plainly in how milicianas in the Spanish Republican forces were presented), while maternity was something that connected women on the basest level, regardless of whether one was a mother.Footnote 31 This reflected the idea, still propagated in many socialist and communist circles of the period, that a woman's most important job was as the bearer of and carer for the next generation of workers. CMF publications themselves emphasized the importance of mothers to socialize and educate children to become effective socialist citizens.Footnote 32

In contrast, Chinese women were eager to dismantle the orientalist image of the Chinese woman as “ethereal and dainty creatures […] with eyebrows as thin as that of a moth, and feet that move so light that they, under the rustling silk, would not even leave footprints on the dust”. The playwright Yang Jiang condemned this image of her countrywomen to the “dead and irrevocable past”, asserting that Chinese women had possessed “indomitable will and courage” during the war.Footnote 33 Similarly, Mrs Tsui-Tsing Chang refuted the “erroneous, but popular, notion among Western people that Chinese women are inferior to men, that they are helpless and always dependent”, a notion solidified by early twentieth-century missionary reports that emphasized Chinese women's “victimization and weakness”.Footnote 34 Instead, she argued that the rights of women had been enshrined in the laws of the Chinese Republic and that the modern Chinese woman desired higher education, a profession, and to make contributions to society.

For many Chinese correspondents, national salvation was key to their conceptions of feminism: only when the nation was emancipated could women be. The CMF also worked with other prominent female Chinese political figures who advocated for support for China in the war. In a letter to the CMF published in December 1936, nine prominent Chinese women argued that resistance was necessary to “support world peace and freedom by a brave national liberation war” and asked for support from anti-fascist women across the globe. He Xiangning, a committee member on the All-China National Salvation Association and a former minister for Women's Affairs, explained that the “only right we should strive for is the right to save the country”, for without that there would be “no women's rights left to strive for”.Footnote 35 This letter was also signed by Shi Liang, a lawyer who was the liaison director of the Women's Advisory Council, a “cross-party national women's organization for national resistance”, and a member of the People's Political Council, an official “forum for public opinions”.Footnote 36 Here, Japanese imperialism was presented as an extension of capitalism and the women acknowledged that only after the expulsion of the imperialist aggressors could women work effectively to achieve gender equality.Footnote 37

Much of the CMF material generated from late 1938 focused on the plight of Chinese women. Images of Chinese women and children with expressions of sadness or pain often accompanied this material in conjunction with questions like “Will You Let This Child Be Bombed?”, which constructed a spectacle for European readers. This exploitation of Chinese women's suffering was designed to elicit a strength of feeling that would galvanize the audience into action, either through protest or donation. This tactic was also utilized by the Chinese women writing for the journal, however. Yang Jiang wrote an article for Woman To-Day in late 1937 in which she deployed violent and emotive language to obtain sympathy from readers. Labelling the Second Sino-Japanese War “the cruellest war the world has ever seen”, Yang described the “thousands of peaceful homes [which] have been reduced to ruins, women and children […] murdered in cold blood, and […] [those who] survived have seen their dear ones tortured and killed before their very eyes”. Yang emphasized the “meaningless atrocity” of the war and argued that this was why Chinese women participated in the conflict.Footnote 38 This allowed European readers to confront the real suffering of women and children and to feel sympathy based on their shared gender.

Maternalism was by no means the dominant discourse employed by Chinese women, but they did, on occasion, utilize the commonality of motherhood and the potential suffering associated with that experience to surmount cultural differences between them and their European audience. They linked motherhood with an inherently peaceable nature, creating a sympathetic image of Chinese women as non-violent and unwilling spectators to the suffering of others. For example, “Madame Quo Tai Chi”, the wife of the Chinese ambassador to Britain, wrote that Chinese mothers had seen their sons struggling “against the invader” and their daughters “meeting the national crisis with every ounce of aid they can give”. She used motherhood as a common identity by asking British women to understand that their Chinese counterparts hoped to witness the development of their children without interference from a foreign power, because “surely that is what all mothers desire for their sons and daughters”. Similarly, the poet Lu Jingqing, who was living in Britain at the time, wrote of the millions of Chinese children “torn by Japanese bombs and shells”, utilizing emotive, violent, and graphic language to appeal to the maternal instincts of the reader. She extended her sympathy to Japanese women as mothers, too, stating that, “millions of Japanese mothers mourn their sons, and wives grieve for their husbands who have been driven to war by the Japanese militarists and Fascists and have lost their lives in Chinese territory”. In this depiction, Japanese women had little agency and argued that women were simply unwilling spectators in the conflict.Footnote 39 Leila Rupp has argued that “violence against women, like motherhood, had the potential to unite women across cultures, since all women were fair game, especially in war”.Footnote 40 This maternal rhetoric, which emphasized the pain of mothers losing their children during wartime, was deployed by the CMF to create connections between women with few cultural bonds separated by great geographical distance, to generate support and material and moral contributions to the campaign.

CHILD SPONSORSHIP STRATEGIES: THE “WARPHANS” CAMPAIGN

The CMF combined these essentialist assumptions with imperialist stereotypes in its shortest, but most successful, humanitarian campaign. The “Warphans” child sponsorship campaign combined a focus on European women as potential mothers and inherent carers with the rhetoric of otherness to develop a charity strategy that presented Chinese children and, by extension, the Chinese population, as passive and in need of direction. It utilized a child sponsorship strategy that sometimes deployed rhetoric influenced by colonialist understandings of China, which occasionally infantilized China. Further, the CMF's “Warphans” campaign severely underplayed the role of Chinese women in organizing support for the at least two million orphans created by the conflict before 1945, as well as giving them little credit for the initial creation of the propagandized image of “Warphans” as a fundraising tactic.Footnote 41 However, these strategies were incredibly effective and made a substantial contribution to the humanitarian effort surrounding the crisis.

The charitable strategy of child sponsorship was still in its infancy by the late 1930s, although its exact origins have been the subject of debate. Henry Molumphy traced the origins of child sponsorship to the Foster Parents Plan for Children in Spain during the Spanish Civil War in 1937 (later Plan International), while Larry Tise asserted that the China's Children Fund was the originator of child sponsorship initiatives during the Second Sino-Japanese War (later ChildFund).Footnote 42 However, recent scholarship by Brad Watson and Emily Baughan has presented Save the Children as the true innovator of the child sponsorship model. Formed in response to the 1919 famine in Austria, Save the Children presented children as apolitical, passive actors to encourage its British patrons to donate to citizens of their recent enemy; Save the Children portrayed children as innocent and helpless, surmounting difficulties of “nationality”, “ambition”, and “material wealth”.Footnote 43 Baughan has argued that Save the Children positioned children as “objects of innate pathos” and “extra-national figures […] entirely removed from questions of nationality or politics”, which fostered the myth that child sponsorship strategies “existed beyond self-interest, political concerns, and international diplomacy”.Footnote 44

The CMF's child sponsorship activities were heavily inspired by Save the Children. By April 1938, 37,253 children were reported as orphans by the China War Orphans Relief Commission, creating a humanitarian crisis that fit the CMF's raison d’être as an activist organization.Footnote 45 In its child sponsorship campaign, the CMF effectively utilized the sympathetic figure of the child not only to place children in an apolitical space that existed beyond national borders, but also to elicit a gendered response from its membership based on maternal feeling. For the CMF, too, these children represented “the standard-bearers of ‘internationalism’”, both politically and geographically. The sponsorship of children from across the globe not only reinforced CMF claims of being “international” but contributed to ideas of a socialist internationalism, which wanted to safeguard the next generation of humanity.Footnote 46

The first mention of the “Warphans” was in the January 1939 edition of Woman To-day in an article penned by Charlotte Haldane following her visit to China, during which she visited an orphanage in Chengdu, Sichuan province. Her account alternates between graphic, violent language, when recounting the experiences of the orphans, and sympathetic descriptions of the orphans themselves, thereby constructing the children as tragic symbols deserving of compassion. With the “Warphans”, this violent language was inherently linked with the idea of children as innocent witnesses. Haldane wrote:

Imagine the plight of one little child, which has seen its home bombed, its mother raped and then murdered by the Japanese soldiery, its father clubbed on the head, or shot in cold blood, when trying to defend her. There are millions of little Chinese children whose eyes bear the memory of such sights that no child should ever be allowed to look upon.Footnote 47

Establishing refugee status was key to this construction of children as objects of pathos. Haldane explained how the orphans had undertaken a nearly 2,000-km journey between Anhui province (where most of the children originated from) and the orphanage in Sichuan, but qualified that it was the only option “to save their poor little lives and limbs from the pitiless massacre of Japanese bombs”.Footnote 48

Haldane's construction of these violent experiences and her construction of individual children as figures of pathos were inextricably linked. When telling CMF members about a specific child, she attempted to create a sense of familiarity for her readers, based on their personal experiences as mothers and carers. For example, Haldane described an eleven-year-old boy as a “pale-faced, keen-eyed little chap; intelligent but not in the least precocious”, stating that the Chinese orphans were “not in the least different from our own children, except that they are somewhat quieter and better behaved, a concomitant, unfortunately, of all that they have been through”. Here, she constructed a personal connection between her readers and the children of China; she was encouraging women to view the “Warphans” as reflections of their children and children they knew in order to foster certain maternal, and subsequently charitable, feelings. However, these descriptions of children were also infused with stereotypes about the Chinese nationality influenced by imperialist assumptions about race. Haldane demonstrated her Western prejudices by claiming that a boy who related his story to her had the “natural dignity and politeness of his race, but without a trace of conceit or self-satisfaction”. Haldane then demonstrated some explicitly hierarchical attitudes towards the children. She wrote of how impressed she was that the boy chosen to talk to her had “no trace of vanity” for being chosen and that his “comrades” showed no “envy” that they were not, suggesting that she felt that the child was lucky to talk to her, a European woman with important international contacts.Footnote 49

The origin of the term “Warphan” was in Chinese nationalist propaganda. The nationalist Kuomintang needed to convince the Chinese people that the welfare of children was a national responsibility, not solely the responsibility of the family as traditional discourse had asserted. Traditionally, the family system instilled appropriate behaviours in children within the home, which were then extended to interactions with society. However, during the war, orphans were “elevated to a national priority” for whom the state was responsible and around whom a concomitant debate was formed. M. Colette Plum has traced how attitudes towards orphans in China developed during the war with Japan and argues that they became a “potent cultural symbol infused with nationalist ideology” as they became threatened by Japanese influence or extermination. Before the war, orphans were often seen as problematic for the state as they represented a threat to societal harmony. They came to be viewed as especially open to manipulation by the Japanese occupiers, which would threaten the minzu (nation, the building of the nation) that the Kuomintang had carefully cultivated since the 1911 Revolution. Those orphaned by war were placed into children's homes and instilled with values to create an inherently nationalist society; this had long-term effects on orphans living in the state children's homes, who grew to maturity with a “strong sense of national belonging and with images of themselves as contributing members of what was described to them during their childhoods as a ‘future China’”.Footnote 50

The “Warphan” was the focal point of child sponsorship initiatives by Chinese women activists before European women launched their campaigns. Key to these Chinese driven initiatives was Soong Mei-ling, who was the first woman to harness the propagandized image of the “Warphan” for foreign fundraising opportunities. The wife of Chiang Kai-shek and the sister of Soong Ching-ling, Soong Mei-ling's most important public work during the conflict was with war orphans; she set up the first orphanage for the children of soldiers in Nanjing and established the Chinese Women's National War Relief Society to care for them. It was Soong Mei-ling who coined the name “Warphan” to refer to those children who lost their parents during the war. She shaped the ideological direction of the children's homes, ensuring that the children felt a belonging to the nation through their common experiences. According to Soong Mei-ling, “Warphans” all spoke Mandarin, dressed uniformly, ate “the same food, [sang] the same songs, [and recited] the same lessons”. She directed the “Warphans” campaign in China itself, imploring her fellow Chinese to care for the “future citizens” of the nation and asking them to “Adopt a warphan for a month!” or to “Adopt as many warphans as your income will allow!”Footnote 51 She was also a frequent visitor to the number one children's home in Chongqing where she ensured “that money and food allocated to the refugee children were not embezzled by corrupt officials”.Footnote 52

The CMF gave Soong Mei-ling little credit for her activism for “Warphans”. Beyond acknowledging that Soong Mei-ling had coined the term, the CMF ignored her role in campaigning and fundraising amongst the Chinese people, giving the impression that the origins of Chinese child sponsorship lay with the CMF. This perpetuated the idea, intentionally or otherwise, that the Chinese people depended on European activism and aid to protect their children, reflecting negative images of Chinese people as helpless, depoliticized, and unable to direct their aid. The criticism of the CMF's erasure of Chinese activism towards children can, and has, been levied against modern child sponsorship organizations, particularly those operating in the 1980s, which deployed “destructive stereotypes” of those in need of aid in the Global South that did not reflect the true extent of their agency.Footnote 53

One of the key narratives in the CMF's “Warphans” campaign positioned donors as “foster parents” who had some level of parental responsibility for their “adopted” child. The “Warphans” child sponsorship scheme was inaugurated in the March 1939 editions of Woman To-day and Femmes dans l'action mondiale with a brief article couched in terms of parenthood and the discourse of adoption. Potential “foster parents” were encouraged to give three pounds a year to adopt a “Warphan”, which would ensure that the parental task of making sure a child was “well-looked after” was carried out by securing “food, shelter, education and medical attention” for their chosen orphan.Footnote 54 Potential donors were approached by deploying language that positioned European “parents” as the saviours of these children; articles told readers “why you must rescue them”, to convince them that they could, as white Europeans, positively alter the course of a child's life by giving only three pounds a year.Footnote 55

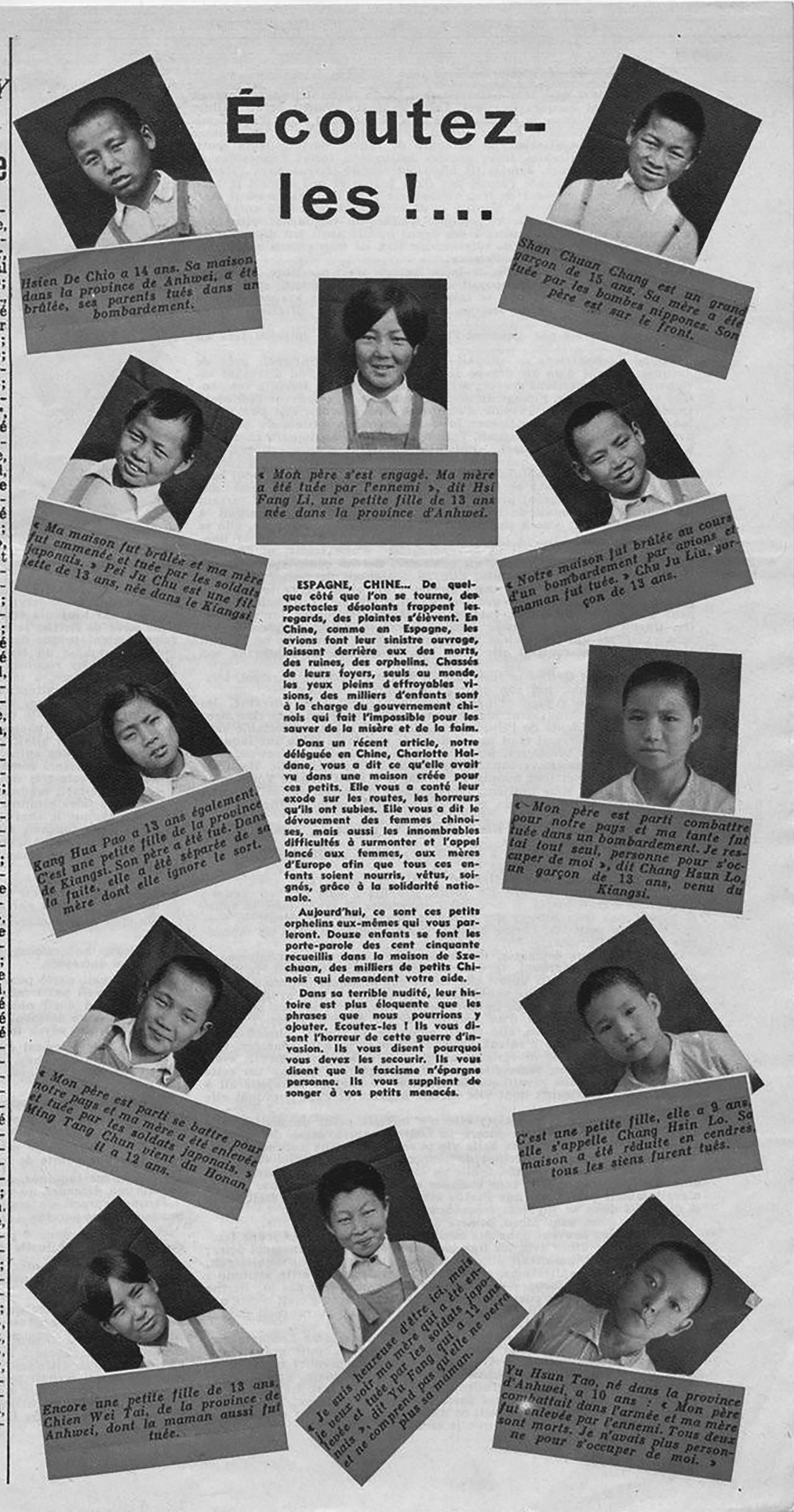

The structure of these articles was simple: a short paragraph informing the reader what a “Warphan” was, several images of Chinese children accompanied by a sentence or two explaining their situation to the audience, and a final paragraph explaining how those interested could find out more information about adopting a “Warphan”. These articles, like other CMF campaigning on the Second Sino-Japanese War, used language that reflected the emotional and violent experiences of the children to appeal to the common identity of motherhood that was so integral to the CMF's attempts to create connections across continents.

In this case, though, the CMF also deployed images of children to reinforce efforts to personalize its child sponsorship campaign. These images did not exploit the suffering of children in the same way that images of Chinese women did. Rather, the committee went to great lengths to depict the children as presentable and well-looked after by the orphanages. Woman To-day predominantly published images of girls in traditional Chinese dress with neat hair trimmed into a bob, while Femmes dans l'action mondiale published photographs of both male and female orphans dressed in the uniform of their orphanage, with bobbed hair for the girls and shaved heads for the boys (Figure 2). This was standard in child sponsorship initiatives in the interwar period; Save the Children provided “respectable head-shots” of children who were “properly clothed and groomed” so that potential donors could visually link the child in need with their own child. These images encouraged potential “foster parents” to select their child personally based on the idea that, provided “food, clothing, nurture, and a reason to smile”, the child would be like their own children.Footnote 56 The CMF borrowed this tactic because it ensured that “foster parents” would take a greater interest in choosing a child, thereby increasing the effectiveness of the campaign in attracting sponsors.Footnote 57

Figure 2. An article from the French CMF journal featuring some of the images of ‘Warphans' published by the committee for fundraising purposes. “Écoutez-les ! ...”, Femmes dans l’action mondiale (March 1939), p. 15. I thank Gallica and the Bibliothéque nationale de France for open and free usage of this image. gallica.bnf.fr /BnF.

The CMF similarly found that including images of orphans for sponsorship allowed potential “foster parents” to envision the child they wanted, based on the limited photographs that they had seen. Letters received from potential sponsors, which emphasized the child's appearance as the reason for choosing them above other factors, reinforced the importance of the image of the innocent, youthful orphan for European audiences. For example, one sponsor asked for an orphaned girl but lamented that he supposed that “all the chubby boys and pretty girls have been taken”, supposing that other sponsors would already have asked for children fitting this description, leaving only the “less desirable” children. In response, the committee found a girl whose “face portrayed the suffering she had gone through” for the donor.Footnote 58 That the CMF provided sponsors with photographs that amplified the pain of the child commodified them in a way that was predicated on concepts of pity and patronage, resembling the “pornography of poverty critique”.Footnote 59 The sponsor responded to the photograph of his “Warphan” by comparing her experience to that of children in the West; he wrote of the thirteen-year-old Chinese girl that he had adopted that: “In this country, a parent would be waiting until their children are 14 so that the money they earn will swell the family pool. This Chinese girl will have a better chance in life.”Footnote 60 The sponsor of this child genuinely believed that his five shillings a month, or three pounds a year, would dramatically improve the child's situation and affect her life for years to come, showing a lacklustre understanding of both the war itself and the corresponding political situation.

Although it did not publish graphic images of injured children, the CMF can certainly be accused of perpetuating Chinese children as spectacle; the CMF emphasized the suffering of the “Warphans” by creating a contrast between photographs that portrayed them as innocent and “naturally dignified” and the accompanying paragraphs which often deployed graphic, emotive language. Miriam Ticktin has argued that innocence became “the necessary accompaniment to suffering, required in order to designate the sufferer as worthy”, with children, as blameless figures, representing the “ideal recipients of care”.Footnote 61 On the other hand, Timothy Brook has argued that many children came out of the Sino-Japanese conflict relatively unscathed, beyond having their “innocence exploited for propaganda photographs”.Footnote 62

Still, there were differences between how the British and French journals presented the children they featured. Woman To-day preferred to keep the “Warphan's” stories short and avoided explicit language. For example, Yu Lan Tuan, a fourteen-year-old girl from Henan province, told the publication that her “village was flooded by the Yellow River” and she had been sent to the orphanage as a result. This description neglects to explain the circumstances around the flood and drastically underplays its catastrophic nature; the Chinese military command had ordered the breaching of the southern dyke of the Yellow River in an attempt to stop the Japanese army from advancing further west, which killed somewhere in the region of 500,000 people and further exacerbated the refugee crisis.Footnote 63 The majority of the children featured became orphans because their fathers had joined the army as their mothers had died before the war; an eight-year-old boy from Sichuan province and a ten-year-old boy from Henan were both sent to government orphanages for this reason. However, some children had witnessed the violence of the conflict first-hand, like twelve-year-old Yu Fang, who had witnessed the kidnap (and presumably the murder) of her mother by Japanese soldiers. Despite her happiness at being in the government orphanage, she wanted desperately to see her mother. The author of the article commented pityingly that Yu Fang did not understand that “she will never again see her mother”, again utilizing language designed to appeal to a shared motherhood to alleviate the suffering of the Chinese “Warphan”.Footnote 64 Even when the language used by Woman To-day to tell the individual stories of “Warphans” was not graphic or explicit, it was emotive and designed to elicit maternal sympathy from readers. In the case of Fu Mao Wei, a fourteen-year-old boy from Hubei province, this attempt to create a link based on the potential motherhood of the readers was clear. Fu Mao Wei recounted that he had been forced from his mother who, “with tears in her eyes kissed [him] goodbye because she was too ill to be evacuated from the city”, a story designed to affect CMF members emotionally as mothers or potential mothers.Footnote 65

On the other hand, the article introducing the “Warphans” in Femmes dans l'action mondiale was more graphic in its quest to stimulate support for the cause. Every story featured in the article described some level of violence personally witnessed by the child. Five of the twelve children featured in the March 1939 issue had survived a Japanese aerial bombing on their home in which either or both of their parents or guardians had died. Children from Anhui and Jiangxi provinces experienced their houses being “burned down in the course of a bombing by plane”; two of the children featured had seen their mother die during the attack, two had seen their entire families perish, and one witnessed his aunt die while she was acting as his guardian. Chang Hsun Lo, a thirteen-year-old boy from Jiangxi, had seen his father leave to join the army, and used his story to reflect the isolation that many “Warphans” felt: he expressed that he remained all alone following the death of his family with “nobody to take care of me”.Footnote 66 A solitary child with no parental support was a particularly effective tactic for appealing to the maternal instincts of women, who, it was assumed, would want to alleviate the damaging isolation of children like Chang Hsun Lo. Lone children presented what Emily Baughan has described as a “logic of incompleteness”, which generated a feeling of “parental responsibility” from the sponsor to the child.Footnote 67

The “Warphans” campaign yielded excellent results. Within a month, women's organizations, university students, schoolteachers and pupils, and convents had already adopted more than fifty orphans out of the one hundred funded by the committee.Footnote 68 A group of women from the central branch of the Association of Women Clerks and Secretaries adopted a “Warphan” as a collective, “several sections” of the Labour Party adopted “Warphans” through the CMF, and some students from Oxford University sponsored Chinese children. Somewhat surprisingly considering the inherently gendered nature of the CMF, several men also came forward to be “foster parents”, a trend that the committee was keen to encourage. Highlighting the inequality for men when adopting domestically, the CMF wrote that the British authorities:

did not encourage men to adopt children, but our committee does. We do not mind who adopts a “Warphan”; from the lowest to the highest-paid worker. We would not refuse the Prime Minister, nor his wife.Footnote 69

The committee did not want to be exclusionary in whom it targeted, despite their entirely female, left-leaning membership. It was more concerned about the success of the campaign in general, including engaging traditional opponents of communism and socialism; for example, the British committee wanted to extend their “Warphans” activism to the public by targeting churches, through whom they could “obtain the aid of their congregations”. The “Warphans” campaign received donations and sponsorships totalling 17,500 francs in March alone, rendering it a rousing success. For comparison, the monetary aid collected for Spain by the CMF between March 1938 and the end of March 1939 (the month that the Warphans campaign began) totalled 55,000 francs, meaning that the CMF had collected around thirty per cent of the amount collected for Spain in a year for China in a month.Footnote 70

CONCLUSION

CMF campaigning in China in the late 1930s gives a new perspective on how socialist women engaged in international activism during the 1930s. The CMF was a transnational communist front organization that subverted communist rhetoric on gender equality by utilizing traditionally feminine symbols to yield what it expected to be the best outcomes. The processes of information exchange and mobility resulting from increasing communications between Europe and China gave Chinese women a unique opportunity to publicize the specific hardships that they faced during the war and to enhance Western understandings of the conflict. It also exposed European women to the gendered violence perpetrated against women in China, including the graphic sexual violence they endured. This, in conjunction with the involvement of prominent female Chinese political figures to legitimize the CMF's campaign, meant that the committee could raise consciousness about the situation amongst its members and fundraise for aid for China effectively. For example, the China Bazaar that Soong Ching-ling contributed pottery to raised 50,000 francs because of her involvement.Footnote 71 The “Warphans” child sponsorship initiative also raised an incredible amount of money in a short time, meaning that the Chinese campaign was one of the CMF's most successful despite lasting eight months at most (compared with the three years of the Spanish campaign).

However, the CMF also relied on both stereotypical and essentialist tropes to achieve this success. Chinese women and children were presented as always quiet, dignified, and innocent despite their inherent emotional strength. The committee's reliance on motherhood as the commonality between its members and Chinese women dominated almost all its discourse on the conflict, which reduced women to mothers only and failed to discuss the political work of women.Footnote 72 This also presupposed that European women involved with the organization would be more likely to respond to emotional appeals based on motherhood as opposed to more rational appeals based on politics or the international situation. Criticisms can also be made of the group's decision to present the experiences and images of Chinese women and children as a spectacle for their readers, to create pathos to encourage people to commit financially. The CMF's campaign in China was an effective means of sourcing monetary aid for a population struggling with the impact of an intensely violent war. However, it also demonstrates how the activism of the CMF, which was supposedly predicated on socialist notions of equality, including amongst races and genders as well as class (if we are to be somewhat reductive about the ideology's fundamental tenets), was much more influenced by traditional gender discourses than would initially have been expected, to attract the greatest number of supporters and therefore the largest amount of money.