Kalasha (ISO 639-3: kls), also known as Kalashamon, is a Northwestern Indo-Aryan language spoken in Chitral District of Khyber Pakhtunkwa Province in northern Pakistan, primarily in the valleys of Bumburet, Rumbur, Urtsun, and Birir, as shown in Figure 1.Footnote 1 The number of speakers is estimated between 3000 and 5000. The Ethnologue classifies the language status as ‘vigorous’ (Eberhard, Simons & Fennig Reference Eberhard, Simons and Fennig2019) but some researchers consider it ‘threatened’ (Rahman Reference Rahman, Saxena and Borin2006, Khan & Mela-Athanasopoulou Reference Khan, Mela-Athanasopoulou, Everhard and Mela-Athanosopoulou2011). Kalasha has been in close contact with Nuristani and other Northwestern Indo-Aryan languages. Among the latter, the influence of Khowar has been particularly strong because it functions as a lingua franca of Chitral District (Liljegren & Khan Reference Liljegren and Khan2017). The Kalasha lexicon includes many loanwords from Khowar, as well as from Persian, Arabic, and Urdu (Trail & Cooper Reference Trail and Cooper1999). Early efforts to put the language in writing employed Arabic script but a Latin-based script was adopted in 2000 (Cooper Reference Cooper2005, Kalash & Heegård Reference Kalash, Heegård, Johnsen, Geertz, Castenfeldt and Andersen2016).

Figure 1 Map showing the location of Kalasha (created with QGIS 2.18.15; QGIS Development Team 2018).

An early study of the Kalasha sound system is Morgenstierne (Reference Morgenstierne1973, based on fieldwork conducted in 1929). More recent studies include Trail & Cooper (Reference Trail and Cooper1985), Mørch (Reference Mørch1995), Mørch & Heegaard (Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997), Bashir (Reference Bashir, Cardona and Jain2003), Heegård & Mørch (Reference Heegård, Mørch and Saxena2004), Cooper (Reference Cooper2005), Heegård Petersen (Reference Heegård Petersen2006), Di Carlo (Reference Di Carlo2010), and Heegård Petersen (Reference Heegård Petersen2015). A dictionary consisting of about 6000 words was published by Trail & Cooper (Reference Trail and Cooper1999). A revised and searchable online version of this dictionary is being used for language education and revitalization (FLI n.d.).

Kalasha dialects can be classified into three groups: a northern group which encompasses the valleys Rumbur, Bumburet, Birir and Jinjiret; a southern group, which includes only the valley Urtsun; and a now extinct eastern group, which encompasses former Kalasha villages along the Kunar river and in the Shishi Kuh valley (Heegård & Mørch Reference Heegård, Mørch, Hansen, Hyllested and Jørgensen2017). The present description is concerned with northern Kalasha, as spoken in the Bumburet (Mumuret) valley. It is based on the speech of two male speakers from the village of Krakal (Kraka’ [kraˈka˞]). Both are co-authors of this paper: Sikandar Kalas (SK) and Taj Khan Kalash (TKK). The speakers are in their 30s. At the time of the recording, they were residing in Greece but continued to maintain close contact with the Kalasha community in Pakistan. Both have been involved in efforts to preserve and revitalize the Kalasha language and culture. Word examples presented below are from Trail & Cooper’s (Reference Trail and Cooper1999) dictionary or its revised online version (FLI n.d.). All items were confirmed with our native speaker co-authors. The recordings were made in a quiet room using a Zoom H4n digital recorder and an AudioTechnica AT831b lavalier microphone, with a 44100 Hz sampling rate. Acoustic analysis of selected data was performed using Praat (Boersma & Weenink Reference Boersma and Weenink2018). Sound files for words mentioned below are provided for one of the speakers, SK.

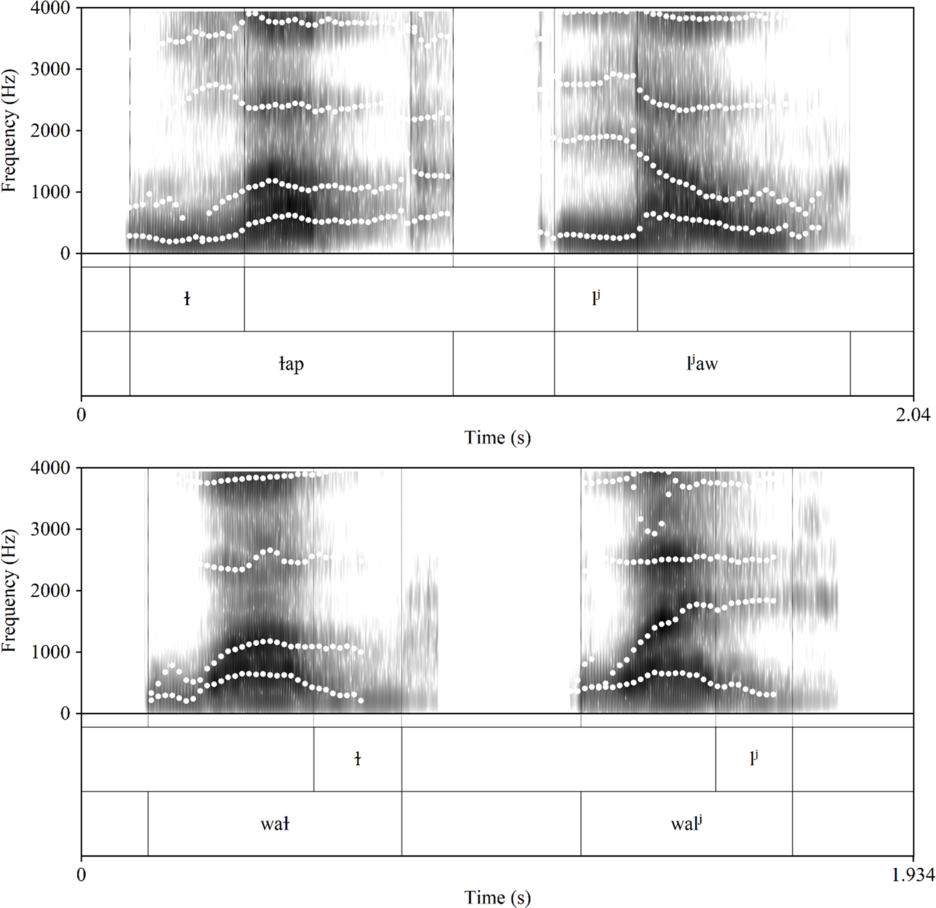

Consonants

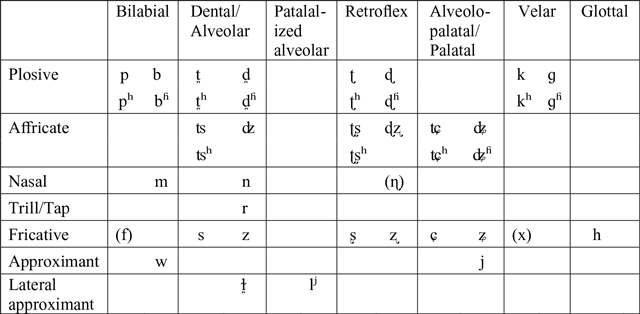

An important characteristic of the Kalasha consonant inventory is a robust set of place contrasts within the class of coronal obstruents, which includes a three-way distinction between dental/alveolar,Footnote 2 retroflex, and alveolopalatal affricates and fricatives, and a two-way distinction between dental and retroflex plosives. While retroflex plosives are typical of Indo-Aryan languages, retroflex affricates and fricatives are an areal feature of the Hindu-Kush region (Ramanujan & Masica Reference Ramanujan, Masica and Sebeok1969, Arsenault Reference Arsenault2017). Another important characteristic is the four-way laryngeal contrast in plosives and (to a lesser extent) affricates, which includes plain voiceless, plain voiced, aspirated voiceless, and breathy voiced categories. A four-way contrast of this kind is quite common in Indo-Aryan languages of the subcontinent (at least in plosives); however, most languages of the Hindu-Kush region tend to have a reduced, three-way contrast (plain voiceless, plain voiced, and aspirated voiceless; Hussain Reference Hussain2018). Sample words with these and other consonants in word-initial position are provided below, both in phonemic IPA transcription and in the Kalasha orthography.

Plosives and affricates

The four-way laryngeal contrast in plosives and affricates is maintained word-initially and word-medially and is neutralized to voiceless word-finally. The neutralized consonants are generally unaspirated, while showing some degree of aspiration utterance-finally or in careful speech (which can be regarded as a phonetic effect). Neutralization appears to be blocked when voiced plosives become prenasalized (see the section on Nasalization). As in Old Indo-Aryan (Whitney Reference Whitney1945), aspirated and breathy voiced segments do not occur more than once within a word. Breathy voiced consonants are somewhat unstable. The breathiness can be realized on adjacent vowels or lost completely; it may also appear sporadically with lexically plain voiced plosives/affricates (Mørch & Heegaard Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997: 9–10; Heegård & Mørch Reference Heegård, Mørch and Saxena2004: 31–32, 50). In our data, the contrast is relatively well preserved in isolated forms; some loss of breathiness can be observed in the passage (see e.g. /ɡʱoˈˈĩ/ ‘quotative particle’ pronounced as [ɡoˈˈĩ]).

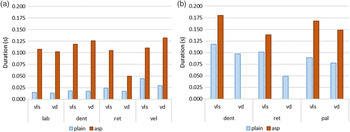

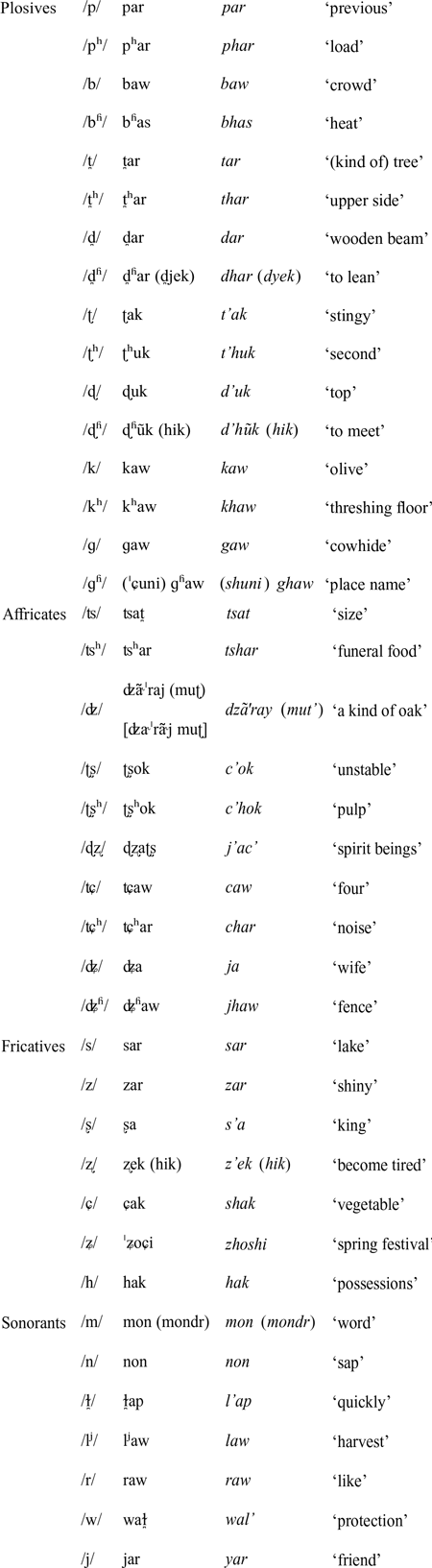

Duration differences among the laryngeal classes can be seen in Figure 2, which plots average release durationsFootnote 3 for word-initial plosives and affricates produced by our two speakers. In plosives, average release durations are 25 ms for plain voiceless, 110 ms for voiceless aspirated, 19 ms for voiced, and 103 ms for breathy voiced. This shows an average difference of 84 ms between the plain and aspirated/breathy categories. The contrast is somewhat smaller for the retroflex place. As would be expected, affricate releases are longer, but still maintain a sizable 67 ms duration contrast between plain and aspirated/breathy categories. On average, releases in our data are 103 ms for plain voiceless, 162 ms for voiceless aspirated, 74 ms for voiced, and 148 ms for breathy voiced affricates (the category that is limited to /ʥʱ/). These results show that the laryngeal contrasts are indeed well-differentiated by duration alone (see also Prosody on f0 differences).

Figure 2 Average release duration for initial (a) plosives and (b) affricates by place (labial, dental, retroflex, alveolopalatal and velar) and laryngeal features (plain and aspirated/breathy categories, voiceless and voiced), based on a total of 440 tokens; note that the breathy voiced dental and retroflex affricates are absent from the inventory.

Aspirated plosives are optionally realized in Kalasha as fricatives: /pʰ/ as [f] or [ɸ], /t̪ʰ/ as [θ], and /kʰ/ as [x] (or [kx]). At least [f] and [x] occur primarily in lexical loans (Trail & Cooper Reference Trail and Cooper1985, Heegård & Mørch Reference Heegård, Mørch and Saxena2004), and therefore can be considered marginal phonemes. In addition, the voiced bilabial /b/ is occasionally lenited to [w] (Mørch & Heegaard Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997: 47). All these realizations are present in the recorded passage.

Kalasha plosives are produced at the bilabial, dental, retroflex, and velar places of articulation. All affricates are sibilant coronals, occurring at the alveolar, retroflex, and alveolopalatal regions. This three-way contrast is typical of languages in the Hindu-Kush region (see Palula: Liljegren & Haider Reference Liljegren and Haider2009; Khowar: Liljegren & Khan Reference Liljegren and Khan2017). All the place contrasts occur word-initially, medially, and finally. Retroflex plosives are typically retracted post-alveolars, which can vary in the degree of retraction and apicality. Affricates, on the other hand, tend to be more retroflex – produced with the tongue tip curled back (Trail & Cooper Reference Trail and Cooper1985). This was confirmed by Mørch & Heegaard (Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997: 51–52) using static palatography.

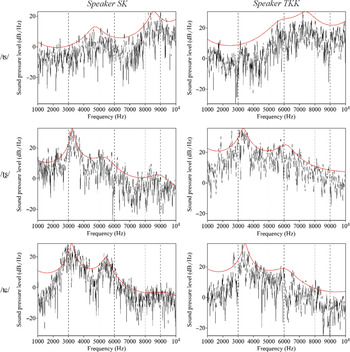

Figure 3 FFT (black) and LPC (red) spectra (made with a 46 ms window centred on the peak of noise intensity) of the frication noise in tsat ‘size’, c’ar dyek ‘ripen’, and car ‘grass’ (single tokens) produced by both speakers.

As in other languages, Kalasha retroflex plosives are acoustically more salient in post-vocalic position than in prevocalic position (see Dave Reference Dave1977 for Gujarati; Hussain et al. Reference Hussain, Proctor, Harvey and Demuth2017 for Punjabi). The following words illustrate the dental–retroflex contrast in plosives post-vocalically: /bʱot̪/ bhot ‘evening meal’ vs. /pʰoʈ/ phot’ ‘chaff, wood shavings’; /bʱut̪/ bhut ‘evil spirit’ vs. /muʈ/ mut’ ‘tree’.

In affricates, the place contrast is distinguished primarily by a combination of noise spectra and formant transitions with adjacent vowels. Spectra for sample tokens are shown in Figure 3. They indicate that the anterior affricate /ts/ is characterized by a greater concentration of high intensity noise at higher frequencies (centre of gravity (COG) is 7300–8200 Hz). In contrast, the two posterior affricates, /ʈʂ/ and /ʨ/, have a concentration of high-intensity noise at much lower frequencies (COG of 3300–3700 Hz). Both also show two main peaks, with the lower frequency one being more intense. The two posterior affricates differ from each other in the lower-frequency slope towards the peak, which is steeper for /ʨ/ than /ʈʂ/. The spectral differences among the affricates are further enhanced by CV transitions, with F2 being the highest for /ʨ/ and lowest for /ts/. F3 is lowered by /ʈʂ/. (For a more extensive acoustic investigation of the Kalasha affricates, the reader is referred to Kochetov & Arsenault, published online 17 January Reference Kochetov and Arsenault2020)

Voiced affricates can vary freely with fricatives for some speakers [ɖʐaʈʂ ∼ ʐaʈʂ]j’ac’ ‘spirit beings’ (Trail & Cooper Reference Trail and Cooper1985), but they are realized consistently as affricates in our data. Other notable variation includes the realization of voiced plosives /b/ and /ɡ/ as [m] and [ŋ] after a nasal vowel or before a nasal consonant. In utterance-final position, voiceless velar /k/ is sometimes unreleased or realized as [ʔ] or glottalization on the vowel (see Trail & Cooper Reference Trail and Cooper1985).

Fricatives

The main class of fricatives in Kalasha are sibilants, which, like affricates, occur at the alveolar, retroflex, and alveolopalatal places. As with affricates, this three-way place distinction is typical of languages in the Hindu-Kush region (Ramanujan & Masica Reference Ramanujan, Masica and Sebeok1969, Bashir Reference Bashir, Cardona and Jain2003, Arsenault Reference Arsenault2017). Voicing is contrastive in sibilant fricatives, but only voiceless fricatives occur word-finally. Non-sibilant fricatives [ɸ f θ x] occur as variants of aspirated plosives (see the discussion of plosives above).

Like affricates, the place of fricatives is distinguished by spectral shapes and vowel transitions. As shown in Figure 4, anterior /s/ has a higher-frequency concentration of energy, while the energy of posterior /ʂ/ and /ɕ/ is concentrated at lower and mid frequencies. Compared to the alveolopalatal affricate discussed above, the alveolopalatal fricative /ɕ/ shows an even sharper drop in energy at the lowest frequencies and a more defined primary peak. Like its affricate counterpart, it substantially raises F2 in CV transitions (Mørch & Heegaard Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997: 66). The retroflex fricative lowers F3 (Mørch Reference Mørch1995) in a similar way to the retroflex affricate.

The voiceless laryngeal /h/ is highly variable. Between vowels or next to sonorants, it is realized as breathy voiced [ɦ] or lost altogether. There are also cases of /h/ shifting to another syllable or [ɦ] being produced in words where it is absent phonemically. The latter has been observed in pretonic intervocalic position, where [ɦ]-insertion is an apparent hiatus resolution strategy (Mørch & Heegaard Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997: 47–48; e.g. /ʂo˞ ˈek/ ʂo˞ ˈɦek]s’o’ek ‘to plug’ produced by SK). This highly labile behavior of /h/, combined with the variability of breathy voiced plosives/affricates (see above), suggests the possibility of analyzing aspiration/breathiness in Kalasha as a word-level prosody (Heegård & Mørch Reference Heegård, Mørch and Saxena2004: 31–32).

Figure 4 FFT (black) and LPC (red) spectra (made with a 46 ms window centred on the peak of noise intensity) of the frication noise in /sak/ sak ‘very great’, s’a ‘king’, and shak ‘vegetable’ (single tokens) produced by both speakers.

Nasals

There are fewer place contrasts for nasals than for plosives. Bilabial /m/ and dental/alveolar /n/ are well established, contrasting in a variety of contexts. The status of retroflex /ɳ/ is more ambiguous. It contrasts marginally with /n/ in word-final position as a result of (variable) consonant cluster simplification: [moɳ ∼ moɳɖr]mond’r ‘whey’ as opposed to [mon ∼ mond̪r]mondr ‘word’. However, some researchers report that it may occur independently in a small number of words (Mørch & Heegaard Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997: 51; Trail, p.c. 2009). An articulatory investigation is required to confirm these observations, as dental and retroflex nasals are difficult to distinguish reliably on purely acoustic and auditory grounds. Moreover, native speakers do not appear to have clear intuitions about retroflex nasals, apart from those arising through final cluster simplification. The process of cluster simplification can also result in word-final alveolopalatal and velar nasals, which are otherwise sub-phonemic, occurring only before homorganic affricates and plosives (see Mørch & Heegaard Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997).

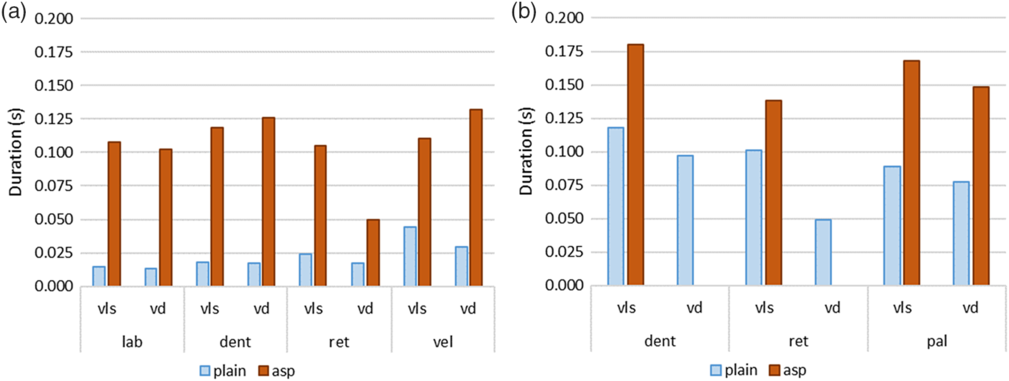

Laterals

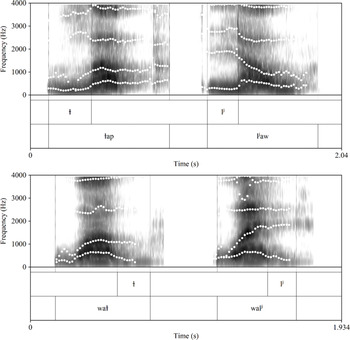

Kalasha has two lateral approximants. /ɫ̪/ is a velarized apico-dental, while /lʲ/ is a palatalized lamino-alveolar (Trail & Cooper Reference Trail and Cooper1985), as in /ɫ̪ap/ l’ap ‘quickly’ and /ljʲaw/ law ‘harvest’. These differences of articulation were corroborated by Mørch & Heegaard (Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997: 52; see also Heegård & Mørch Reference Heegård, Mørch and Saxena2004) using static palatography. Acoustically, the laterals differ in F2 during the closure; F2 is lower for /ɫ̪/ and higher for /lʲ/, indicative of moderate velarization and palatalization. The velarized lateral induces some backing in adjacent vowels, while the palatalized lateral induces fronting. This can be seen in Figure 5, which provides an annotated spectrogram of the two laterals occurring word-initially and word-finally. Note that the place difference in F2 during the closure is about 700–800 Hz. Our larger-scale acoustic investigation of Kalasha laterals (produced by 14 speakers of different age groups and genders) revealed that /ɫ̪/ velarization was clearly present in younger speakers and largely absent in older speakers (Kochetov, Heegård Petersen & Arsenault Reference Kochetov, Heegård Petersen and Arsenault2020). This suggests that palatalization is the main distinctive feature of the contrast, while velarization has developed more recently, either as an enhancement strategy or due to the influence of Khowar.Footnote 4 Thus, the contrast can be alternatively classified as /l̪/ vs. /lʲ/.

Figure 5 Formant patterns (Hz) in words with contrastive laterals: l’ap ‘quickly’ vs. law ‘harvest’ (top), and wal’ ‘protection’ vs. wal ‘pity’ (bottom) by speaker SK.

Rhotics

The phoneme /r/ has a rather variable realization. It tends to be weakly trilled or fricated word-initially and after a plosive (Mørch & Heegaard Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997: 51). Similar, but devoiced, realizations occur utterance-finally. Intervocalically, /r/ is often a tap. Our data confirm these observations, while also pointing to occasional retroflex approximant-like realizations (see e.g. [pʰaɻ]phar ‘load’ by SK). Utterance-initially, /r/ may be preceded by a short vocoid (e.g. /ra/ ra ‘way’ as [ᵊra]). Next to a nasalized vowel, /r/ is optionally realized as [ɾ͂] (e.g. the first instance of /ˈsirã/ sirã’ ‘wind’ in the passage, realized as ˈsiɾ͂ã]).

In addition to /r/, the Birir variety of Northern Kalasha has a retroflex flap /ɽ/. This phoneme does not occur in the Bumburet variety described here, which has retroflex vowels instead (see the discussion of vowels, below). (See also Mørch & Heegaard Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997: 63–64 and 80–85; Heegård & Mørch Reference Heegård, Mørch, Hansen, Hyllested and Jørgensen2017: 243 on rhotics in other varieties of Kalasha.)

Glides

There are two glides in Kalasha. The bilabial /w/ is often realized in onset position as labiodental [ʋ] or [v], especially before front vowels (Trail & Cooper Reference Trail and Cooper1985; Mørch & Heegaard Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997: 52–55). The palatal /j/ shows little variation.

Consonant clusters

Onset clusters consist of obstruent + liquid or /j/. Examples include /praɕ/ prash ‘soft’, /t̪rip/ trip ‘sickness’, /ʈrits/ t’rits ‘kind of bird’, /ˈkriʂna/ kris’na ‘black’, /blʲats/ blats ‘short’, and /kɫ̪uʨ/ kl’uc ‘quickly’. Sequences of dental plosive + /j/ are realized as (alveolo)palatal plosives (e.g. /d̪jek/ in dhar dyek ‘to lean’ as [ɟek]). Some initial clusters can be broken up with a short epenthetic vowel (e.g. [sᵊras(t̪)]srast ‘avalanche’; see Mørch & Heegaard Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997). Trail & Cooper’s (Reference Trail and Cooper1999) dictionary also includes sequences of sonorant + /h/, as for example in /mhalʲ/ mhal ‘curse’, /ɫ̪ho˞ʂʈ/ l’ho’s’t’ ‘charcoal’, and /rha/ rha ‘cedar’. In our data, however, these words tend to lack frication or breathiness. They are pronounced much like the single-onset sonorants in /malʲ/ mal ‘goods’, /ɫ̪om/ l’om ‘a measure’, and /ra/ ra ‘way’. The word /ˈlʲhojak/ lhoyak ‘smooth’, as produced by speaker SK, is an exception: /h/ is realized here as breathy voiced [ɦ] and preceded by a short epenthetic vowel ([lʲəˈɦojak], which makes it clearly different from the onset in /lʲots/ lots ‘lightweight’). This indicates that sonorant + /h/ sequences are only marginally present in this variety of Kalasha.

Final coda clusters include: homorganic nasal + plosive; fricative + plosive; dental plosive + /r/; and approximant /w, j/ + consonant. Examples include /ɖoɳɖ/ d’ond’ ‘double bride-price’, /prost̪/ prost (hik) ‘to bow’, /ɡoʂʈ/ gos’t’ ‘barn’, and /ʈʂʰet̪r/ c’hetr ‘field’. In many lexical items final clusters are simplified by leaving the second consonant unpronounced, as for example in [ɖoɳ ∼ ɖoɳɖ]d’ond’ ‘double bride-price’, [d̪raʂ ∼ d̪raʂk]dras’k ‘small amount’, and [sᵊras ∼ sᵊrast̪]srast ‘avalanche’.

Vowels

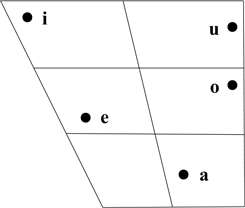

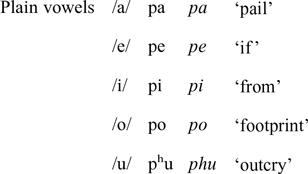

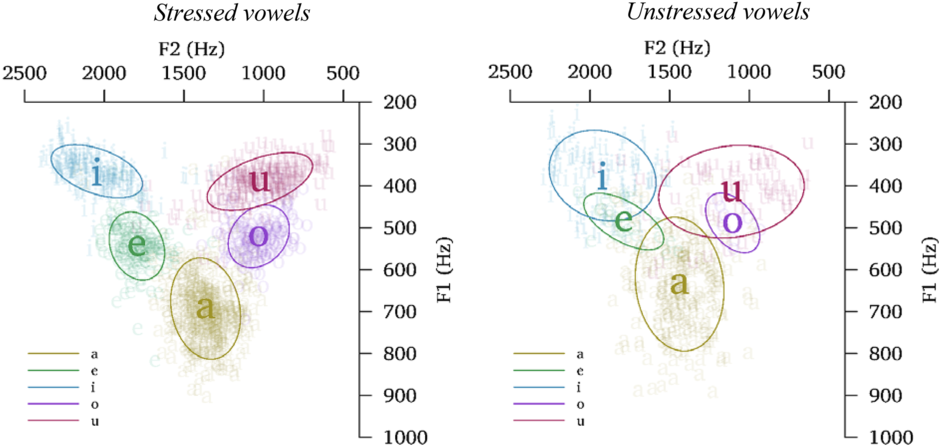

Kalasha has five primary vowel qualities (plain vowels), as indicated in the cardinal vowel chart above. The positioning of these vowels on the chart is approximate and is based on F1 and F2 values produced by our two speakers in the words presented below (see also Figure 6). Note that the front mid vowel /e/ is somewhat low, relative to its back counterpart /o/, and could be transcribed as [ɛ].

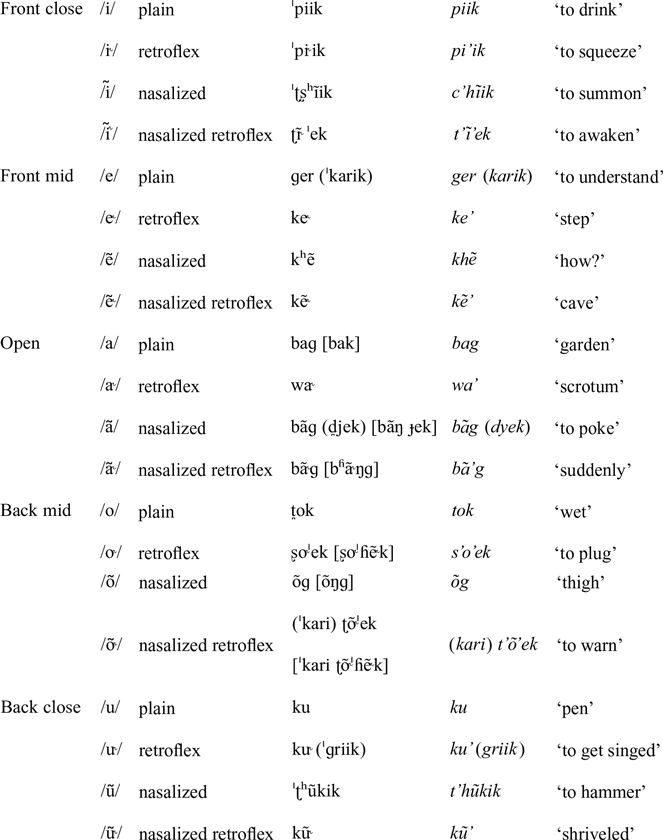

Each of the five vowel qualities can be accompanied by contrastive nasalization (/a͂ e͂ ĩ o͂ u͂/), retroflexion (or rhotacization; /a˞ e˞ i˞ o˞ u˞/), or both (/a͂˞ e͂˞ ĩ˞ o͂˞ u͂˞/). As a result, the language has 20 vowel phonemes belonging to four classes: oral non-retroflex (plain), oral retroflex, nasalized non-retroflex, and nasalized retroflex. Nasalized and retroflex vowels bear a low functional load relative to their oral and non-retroflex counterparts (Cooper Reference Cooper2005). The phonemes /i˞/ and /ĩ˞/ are particularly rare, probably due to the conflicting articulatory requirements of retroflexion, on the one hand, and a high front (‘palatal’) tongue position, on the other (Hamann Reference Hamann2003). These contrasts are illustrated separately for each vowel quality in the table below. Phonetic transcriptions are provided in cases where the speaker’s realizations deviate from the phonemic form (due to various processes of neutralization, assimilation, or sporadic variation).

Nasalization

Following Trail & Cooper (Reference Trail and Cooper1985, Reference Trail and Cooper1999), vowels that occur before a homorganic nasal + plosive sequence are analyzed as nasalized vowels followed by a plosive; the homorganic nasal is treated as non-phonemic. Thus, a broad transcription such as /o͂ɡ/ for õg ‘thigh’, shown above, typically corresponds to [o͂ŋ ɡ] or [o͂ŋɡ] in narrow transcription (see Masica Reference Masica1991 for discussion of this issue in other Indo-Aryan languages). (Note that final devoicing does not apply here, being blocked by consonant nasalization.Footnote 5) In some cases, the nasalization spreads through the following plosive resulting in realizations such as [ba͂ŋ] for /ba͂ɡ/ (in bãg dyek ‘to poke’). In polysyllabic words, the precise locus of nasalization can vary, as nasalization optionally spreads to vowels in adjacent syllables (e.g. [ˈwe͂.a ∼ ˈwe.a͂ ∼ ˈwe͂.a͂]wẽa ‘far upstream’; see Mørch & Heegaard Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997: 43–44).

Retroflexion

Retroflexion is the most intriguing aspect of the Kalasha vowel system. Kalasha may be the only known language with a fully symmetrical set of retroflex (or rhotacized) and non-retroflex vowel phonemes.Footnote 6 The precise articulatory mechanism involved in the production of these vowels is not clear. Trail & Cooper (Reference Trail and Cooper1985) suggest that the vowels are produced by ‘slightly curling’ the tip of the tongue, but Heegård & Mørch (Reference Heegård, Mørch and Saxena2004) found variation among their informants, who produced the vowels either by curling the tongue tip or by raising and bunching the middle of the tongue (see Ladefoged & Maddieson Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996). Despite the variation, Heegård & Mørch favour the term ‘retroflex’ over ‘rhotacized’, arguing that retroflexion of the tongue tip appears to be the most common strategy for producing the vowels. Whether this is correct or not (see Hussain & Mielke Reference Hussain and Mielke2018 for some ongoing articulatory work), the term ‘retroflex’ seems appropriate given the phonological patterning of the sounds (as part of a larger system of consonants and vowels) and their historical sources.

Historically, the retroflex vowels evolved from plain vowels primarily under the influence of a following intervocalic retroflex plosive or nasal, or Old Indo-Aryan (OIA) /r/ in its various phonetic forms. The consonants were eroded through lenition, leaving retroflexion on the vowels (and nasalization, in the case of [ɳ]); e.g. /aˈʐa˞i/ az’a’i ‘apricot’ < OIA /aʂaɖʱiːja/; /ˈgɦũi˞/ ghũ’i ‘goat-hair coat’ < OIA /ɡoːɳiː/ (Mørch & Heegaard Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997: 77–86; Trail & Cooper Reference Trail and Cooper1999; see also Morgenstierne Reference Morgenstierne1973: 191; Heegård & Mørch Reference Heegård, Mørch and Saxena2004: 67–72). A retroflex flap [ɽ] is still preserved before /i/ in the Birir (Biriu) variety of Kalasha, and sporadically in others (compare Birir /aˈʐaɽi/ ‘apricot’ and /ˈɡu͂ɽi/ ‘goat-hair coat’ with their Bumburet cognates, listed above; Heegård & Mørch Reference Heegård, Mørch and Saxena2004, Reference Heegård, Mørch, Hansen, Hyllested and Jørgensen2017; see also Di Carlo Reference Di Carlo2010).Footnote 7

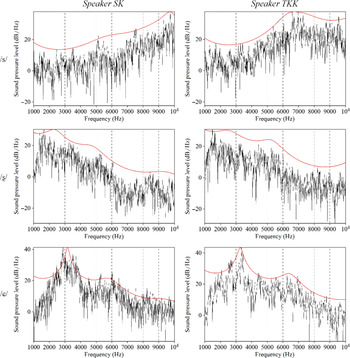

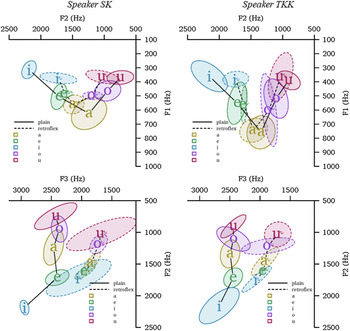

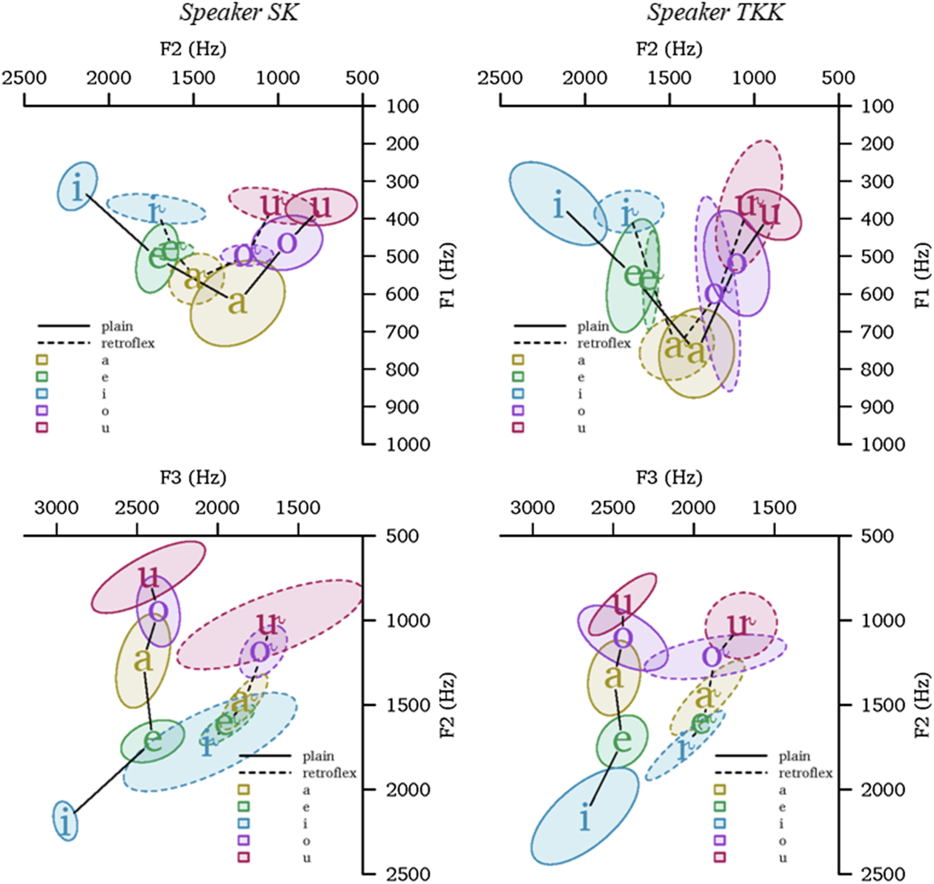

Acoustically, retroflex vowels are more centralized than their plain counterparts, and are most clearly characterized by a lower F3 (see Heegård & Mørch Reference Heegård, Mørch and Saxena2004). This is evident in Figure 6, which plots the formants F1 and F2 (the top plots), and F2 and F3 (the bottom plots) for non-nasalized vowels produced by our two male speakers.Footnote 8 Note that the retroflex vowels produced by SK are more centralized (in F1 and F3) than those for TKK; both speakers, however, show similar differences in F3 (see also Kochetov, Arsenault & Heegård Petersen Reference Kochetov, Arsenault, Heegård Petersen, Calhoun, Escudero, Tabain and Warren2019).

Figure 6 F1/F2 (top, Hz) and F2/F3 (bottom, Hz) plots showing means (indicated by IPA sound symbols) and 2 standard deviations (indicated by ellipses) for oral vowels produced by the speakers SK and TKK (based on 157 and 140 tokens, respectively); the vowels occur in words with no other retroflex vowels, retroflex consonants or /r/.

As with nasalization, the locus of retroflexion can vary in polysyllabic words, and sources differ as to which vowels are transcribed as retroflex (e.g. [ˈku.a˞k ∼ ˈku˞.ak ∼ ˈku˞.a˞k]kua’k ‘child’; see also the words ‘to plug’ and ‘to warn’ in the table above). Moreover, retroflexion tends to ‘spread’ from retroflex vowels to plain vowels in adjacent syllables, often permeating intervening consonants and crossing morpheme boundaries (Mørch & Heegaard Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997: 44; Arsenault & Kochetov, Reference Arsenault and Kochetovin press), as, for example, in [t̪raˈpu˞i ∼ t̪raˈpui ∼ t̪raˈpui]trapu’i ‘eye disease’. In our data, retroflex harmony of this kind is bidirectional, but predominantly progressive, and tends to spread through non-coronal consonants (other than /j/).

Allophonic variation

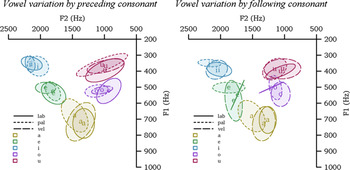

Vowels show some moderate variation depending of the place of articulation of adjacent consonants, and most notably next to alveolopalatals and labials. As can be seen in Figure 7, the front mid vowel /e/ appears to be most variable, showing some differences in height, [e ∼ ɛ] (see Trail & Cooper Reference Trail and Cooper1985; Mørch & Heegaard Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997: 41). All vowels are considerably fronted and show an [j]-like offglide/onglide next to alveolopalatals. As a result, back vowels in this context can be narrowly transcribed as [ʉ]/[u̟], [o̟], and [Æ] (Mørch & Heegaard Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997: 41). In addition, all vowels show some lowering in F3 (not shown in the figure) next to retroflex consonants and /r/. The degree of this retroflexion appears to be greater in the context of retroflex fricatives. At least some of these cases can be considered categorical assimilation resulting in a neutralization of the retroflex contrast for vowels in that context.Footnote 9

Figure 7 F1/F2 (Hz) plots showing means (indicated by IPA sound symbols) and 2 standard deviation ellipses for oral stressed vowels in CVC syllables by selected places of articulation of the preceding and the following consonant, as produced by SK (based on 334 and 267 tokens, respectively); the consonant places are ‘lab(ial)’, ‘pal(atal)’, and ‘vel(ar)’ (with other places, as well as the consonants /r j w/ excluded).

Vowel length

Vowel length is closely tied to prosody in Kalasha (discussed below) and is not generally considered phonemic. However, some researchers have suggested that there may be limited contrast. Bashir (Reference Bashir1988: 35) notes that vowel length and stress may be independent variables in Kalasha, although she does not elaborate. Heegård & Mørch (Reference Heegård, Mørch and Saxena2004) suggest that length may be contrastive, at least for /a/ in open stressed non-final syllables (see Heegård Reference Heegård, Niemi, Odlin and Heikkinen1998), but they leave the question open for future, more focused studies.

Sequences of vowels

Sequences of two vowels are common and can include sequences of identical vowels. Vowel sequences are always syllabified as two syllables (e.g. ˈʂo˞/.ek/ s’o’ek ‘to plug’, /ˈɡri.ik/ in ku’ griik ‘to get singed’) (and variably separated by [ɦ], as noted above). Hence, they are regarded as true sequences as opposed to diphthongs or long vowels.

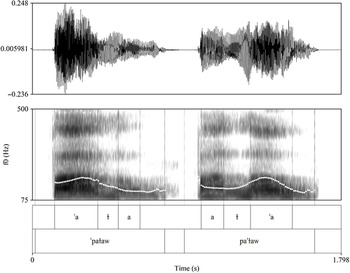

Prosody

Stress is lexical and can fall on virtually any syllable, but some lexical items exhibit variable stress. The following minimal pair illustrates the stress contrast: /ˈpaɫ̪aw/ pal’aw ‘(he) falls’, /paˈɫ̪aw/ pal’aw ‘apple’. In our data, stressed vowels are characterized by overall higher pitch (see Mørch & Heegaard Reference Mørch and Heegaard1997: 55–57), longer duration, and greater amplitude. This can be seen in Figure 8 which shows waveforms and spectrograms, along with pitch tracings, for the minimal pair mentioned above. The stressed variants of /a/ show differences in the pitch (white speckles), duration (annotated intervals), and intensity (amplitude of the waveform) compared to the unstressed variants. It should be noted that this generalization holds for words uttered in isolation, where pitch contours reflect a combination of stress and (declarative statement) intonation. A more systematic study of stress in Kalasha is required to determine if the generalization holds in connected speech.

Figure 8 Waveforms and spectrograms of the words /ˈpaɫ̪aw/ pal’aw ‘(he) falls’, /paˈɫ̪aw/ pal’aw ‘apple’ produced by speaker SK; pitch (Hz) is indicated by white speckles.

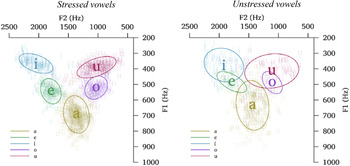

Our acoustic analysis of a larger data set revealed that unstressed plain vowels are about 30% shorter than stressed vowels in duration. They are also considerably more variable (being affected by consonant contexts) and centralized, compared to stressed vowels. This can be seen in Figure 9.

Figure 9 F1/F2 (Hz) plots showing individual tokens (smaller IPA sound symbols), means (larger symbols), and 2 standard deviation ellipses for stressed and unstressed vowels produced by SK (based on 1219 and 480 tokens, respectively).

Some languages of northwestern South Asia have developed lexical tone contrasts (often triggered by the loss of breathy voicing in plosives; Masica Reference Masica1991: 102). Kalasha is not generally counted among them (see Reference StrandStrand in press), although Bashir (Reference Bashir, Cardona and Jain2003: 851) has noted the occurrence of ‘salient pitch/tone contours’ in northern Kalasha. In our data, some pitch differences can be observed depending on the laryngeal specification of preceding plosives (or affricates). For speaker SK in particular, f0 is lower at the vowel onset after aspirated and breathy voiced plosives than after plain voiceless and voiced plosives (by 17–21 Hz on average). For TKK, f0 differences are mostly between voiceless (plain/aspirated) and voiced (plain/breathy) categories, with the latter having lower values (by 18–24 Hz on average). While some of these differences are presumably automatic (e.g. f0 suppression next voiced stops; Kingston & Diehl Reference Kingston and Diehl1994), others appear to be language-specific, most notably the lowering of f0 after voiceless aspirated stops). This might be indicative of emerging pitch patterns in Kalasha. Similar low or low-rising pitch contours have been reported after aspirates in other Northwestern Indo-Iranian languages, including Khowar (Liljegren & Khan Reference Liljegren and Khan2017) and Kalam Kohistani (Baart Reference Baart2004). Thus, a closer examination of pitch variation in Kalasha is required.

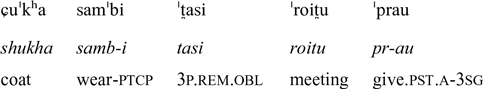

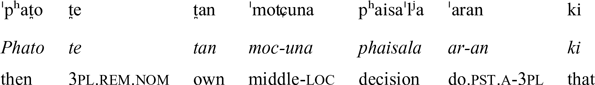

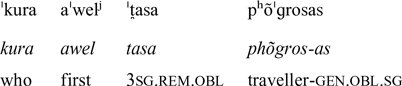

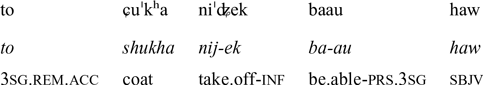

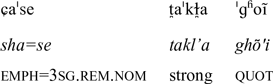

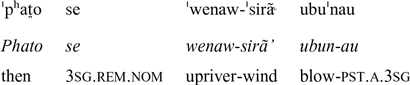

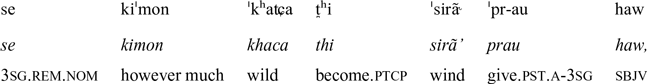

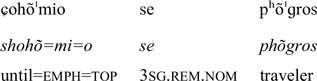

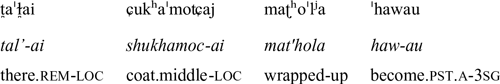

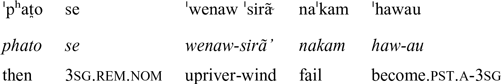

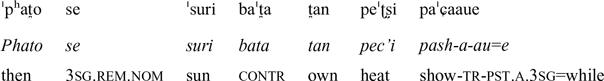

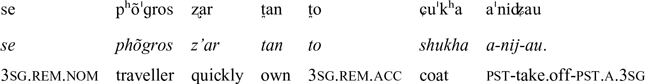

Transcription of a recorded passage

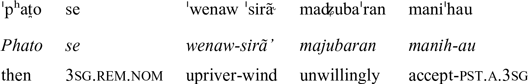

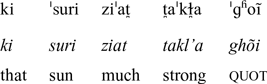

The following text is a free translation of the ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ fable produced by one of the authors, Sikandar Kalas (speaker SK).

The order of the presentation is:

Broad phonetic transcription

Orthographic version

Morphemic glossing

Translation

‘The North Wind and the Sun were arguing between themselves (about) who is stronger;’

‘All of a sudden a traveler wearing a cloak stumbled upon them.’

‘Between them they decided that who(ever) can make the traveler take off his cloak first is the stronger one.’

‘Then the North Wind blew,’

‘(but) no matter how strong and wild he blew,’

‘the traveler only covered himself with the cloak;’

‘then the North Wind gave up.’

‘Then as the Sun showed his heat,’

‘the traveler immediately took off his cloak.’

‘Then the North Wind conceded’

‘that the Sun is stronger.’

Abbreviations

3 = third person

A = actual (past)

acc = accusative

anim = animate

contr = contrastive

emph = emphasizer

gen = genitive

inf = infinitive

loc = locative

nom = nominative

obl = oblique

p = plural (verbs)

pl = plural (nouns)

prs = present

pst = past tense

ptcp = participle

quot = quotative particle

refl = reflexive

rem = remote (pronoun)

sbjv = subjunctive particle

sg = singular

top = topicalizer

tr = transitivizer

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ida Elisabeth Mørch, Ron Trail, and Greg and Elsa Cooper for sharing and discussing with us their Kalasha materials. We would also like to thank the JIPA Editor Amalia Arvaniti, the journal audio manager André Radtke, and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback and assistance with improving the manuscript. The research was partly supported by a Social Sciences & Humanities Research Council of Canada grant (#435-2015-2013) to the first author.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100319000367.