In December 1970, white women’s liberationist Ellin Hirst voiced the clear frustration of many activists in 1960s social movements who felt pressured to choose between issues, ideologies, and tactics when she declared:

I want a movement that is for me and my head in its entirety. I don’t want to be boxed up and have my mind in drawers. I don’t want to have to leave women, the people who I am, in order to do things which I, as a woman, want to do. … Because we understand our own oppression, does that supersede the knowledge that we already had of the evil that the US visits daily on black people, on Vietnamese, Chicano, Puerto Rican, Brazilian, Palestinian, on every people? When we say that we want freedom and liberation does that deny that want in others? Does my liberation mean not your liberation? Is there competition for freedom, for struggle?Footnote 1

In the summer of 1969, the New Left organization Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) imploded at its national convention when Black Power, women’s liberation, and revolutionary youth activists quarreled with one another and could not find a compromise. Nevertheless, Hirst’s desire for unity, if not uniformity, was not unique, but rather representative of many who wanted to force a change in US society and foreign relations, including putting an end to US involvement in Vietnam. Unfortunately, many activists and organizations did not agree on tactics, proposed solutions, or even the underlying problems. This diversity of opinion within antiwar circles grew out of 1950s peace, civil rights, and Old Left movements, each of which focused on different aspects of US foreign and domestic policies, and eventually incorporated strategies and ideas that stemmed from New Left, Black Power, Asian American, Chicano, and women’s liberation movements. Instead of coalescing or forming a singular voice, by the end of the 1960s, activists’ and organizations’ arguments against the American war in Vietnam ranged from pacifist principles against all war to revolutionary statements in support of a Vietnamese victory over “US imperialism.” What they had in common was that each of these movements tied US action abroad with domestic policies at home; that is, the war remained a salient touchstone in activists’ and organizations’ drive to create a more just society regardless of why or how they protested the war or injustice.

The tangle of 1960s activism can easily restrain the historian’s ability to capture the breadth of antiwar sentiment and protest during the US–Vietnam War years. The desire and need to limit and categorize participants in histories of civil rights, antiwar, and feminist movements, for example, have led scholars interested in anti–Vietnam War activism to pay more attention to groups, people, and demonstrations geared primarily or solely toward opposing US intervention in Vietnam. These histories, although valuable, do not fully reflect the complexity of antiwar sentiment prevalent throughout US society. Many scholars of 1960s social movements know that activists crossed movement and organizational boundaries to protest US involvement in Vietnam as well as to support the social and economic rights of communities of color and to call attention to women’s unequal status. Although the 1960s antiwar, civil rights, and feminist movements each have hundreds of volumes dedicated to their study, the time is ripe to uncover the cross-fertilization between movements. Some scholars, particularly those studying civil rights movements, have begun this work by researching antiwar activism in communities of color or by analyzing women of color feminisms.Footnote 2 Building off of this work, this chapter considers the relationship of a myriad of 1960s social movements to antiwar arguments and actions.

Beginning such a project (and writing a brief account of it) is a daunting task, but here, the 1960s North Vietnamese government steps in to help. President Hồ Chí Minh believed that Hanoi needed to foster people-to-people relationships with American citizens (as well as citizens of other nations) who might oppose US military and government actions.Footnote 3 The initiation of these kinds of relationships with Americans began well before the US war years; in 1945, the Vietnamese–American Friendship Association formed “to enable the two peoples to make a thorough acquaintance of the other’s culture and civilization,” but soon the mission was suspended when the United States supported France during the French Indochina War.Footnote 4 Twenty years later, during the American war in Vietnam, Hanoi officials renewed efforts to establish ties with American citizens in the hope that by informing the American public about the bombing of nonmilitary targets in North Vietnam, the use of nonconventional weapons, and the deaths of civilians, American citizens would pressure the US administration into withdrawing US troops.

On the American side, limited press coverage early on during the war created a vacuum of information that drew activists to communicate with Vietnamese to find out more about the situation on the ground.Footnote 5 One of the first such contacts occurred in May 1965, just two months after US bombing over North Vietnam began, when white peace activists Lorraine Gordon and Mary Clarke visited the North Vietnamese Embassy in Moscow and accepted an invitation to travel on to Hanoi to meet with members of the Vietnamese Women’s Union (VWU).Footnote 6 The VWU fell under the leadership of the Vietnamese Workers’ Party (VWP) in North Vietnam and was charged with establishing people’s diplomatic ties with women’s organizations around the world. This initial meeting between American citizens and Vietnamese set the stage for about 200 anti–Vietnam War activists, from a variety of 1960s social movement circles, to travel to North Vietnam during the US war years.Footnote 7 Some Americans traveled to South Vietnam, and many more met with Vietnamese at antiwar conferences held around the world. There, Americans learned of antiwar efforts happening in other countries, exchanged notes on effective protest strategies, and planned international antiwar actions.

American delegations to Hanoi and to international conferences were often diverse. North Vietnamese officials made a point of inviting participants from a variety of social movement circles to Hanoi because they knew that in order for people’s diplomacy to work, Hanoi needed to reach a cross-section of the American population. Indeed, “Vietnamese communist leaders … adapted their antiwar messages to appeal to different audiences in the global antiwar movement,” according to historian Lien-Hang T. Nguyen.Footnote 8 Americans also wanted to build a united antiwar front and worked with their Vietnamese counterparts to invite civil rights, feminist, and other activists to Hanoi or to international antiwar conferences. A few established peace activists, such as Dave Dellinger and Cora Weiss, suggested and recruited American citizens to travel to Vietnam or to attend meetings elsewhere. They, as much as the Vietnamese, had a desire to include American activists who might increase efforts to protest the war. Looking at a few of these delegations provides a window onto the variety of antiwar activity and sentiment, indicates the transnational dynamic of opposition to the Vietnam War, and shows the cross-fertilization that occurred between movements. Ironically, travel to an enemy nation – an act that one might assume only the most radical of activists would have undertaken – is a means to create a sample of the breadth of antiwar sentiment and activism.

Civil Rights Influences on Antiwar Sentiment

Activists involved in pacifist and nuclear disarmament campaigns of the 1950s and early 1960s were, unsurprisingly, some of the first to speak out against US involvement in Vietnam, but from the earliest days of antiwar protest, some civil rights advocates also made known their opposition to the war. Indeed, immediately following the deployment of US ground troops in Vietnam in the spring of 1965, editors of the civil rights periodical Freedomways published an op-ed calling the war “one of the most tragic and morally unjustifiable adventures in our nation’s history” and asking for “fuller cooperation between the grass-roots participants and leaders of the Peace Movement and Civil Rights Movement.”Footnote 9

Cooperation would not come easy, however. Indeed, in November 1965, some 1,500 activists met at a contentious convention hosted by the National Coordinating Committee to End the War in Viet Nam (NCCEWVN). There, participants agreed on future dates for demonstrations, but little else – tactics, goals, and strategies remained contested. The few civil rights activists in attendance “dismissed the convention as irrelevant.”Footnote 10 By the spring of 1966, the “breadth and vitality” of antiwar sentiment was clear, but no single organization or central directorate could encompass or fully harness it.Footnote 11 Nevertheless, some antiwar leaders sought to build broadbased support to end the war, and civil rights advocates described their stance on the war as stemming from a position of “moral conscience.”Footnote 12

Both Hanoi officials and white American antiwar activists wanted to make full use of the opposition of civil rights leaders to the war to forward their cause. Thus, when the VWU looked to host a delegation of American women in Hanoi in the winter of 1966, evidence suggests that members of the North Vietnamese government asked white antiwar activist Dave Dellinger, who visited Hanoi in the fall of 1966, for names of women in peace and civil rights organizations.Footnote 13 Ultimately, a group of four women – African American Diane Nash, known for her role in organizing 1960 sit-ins in Nashville, Tennessee; Puerto Rican Grace Mora Newman, sister of one of the Fort Hood Three, a group of soldiers who refused to serve in Vietnam; white pacifist Barbara Deming, who had visited Saigon in the spring of 1966; and white Southeast Asian scholar Patricia Griffith – traveled to North Vietnam in December 1966, in the midst of heavy bombing.

Besides all participating in this extreme undertaking, the four women had little in common, according to Diane Nash. They disagreed on everything “from childcare and men to politics and nonviolence”; like many who held antiwar stances, they simply all opposed the war.Footnote 14 For Nash’s part, she told reporters she had traveled to Hanoi because she had seen a photograph of a “distraught [Vietnamese] mother holding a wounded or dead child” and wondered whether the depiction was accurate.Footnote 15 To find out the truth behind the photograph, she and her three companions visited hospitals, surveyed recently bombed-out buildings, and met with important political figures, including Hồ Chí Minh.

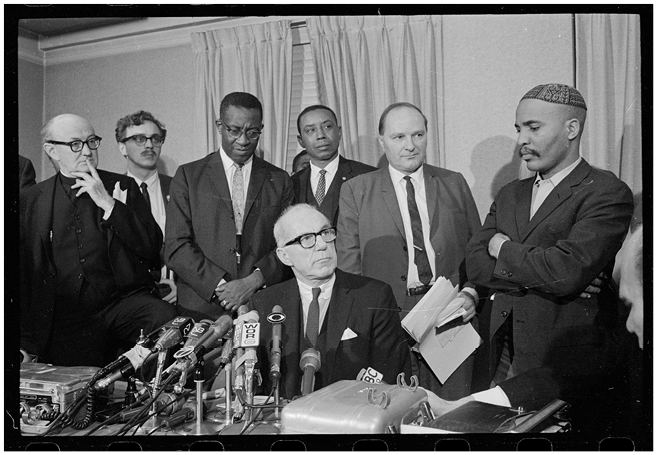

Judging from an article Nash penned following her trip, the prevalence of civilian casualties particularly struck her. In it, she included gruesome details told to her during interviews with recent victims of US bombings. These testimonies complemented what she observed in and around Hanoi, as well as what she heard in meetings with doctors, municipal officials, and religious leaders. Citing all of these sources, Nash testified that conditions for civilians were worse than she had imagined – widespread bombing frequently killed women and children, in contradiction to official reports about the war coming from US government sources. Her observations of life in Hanoi led Nash to sum up her view of the war as “using murder as a solution to human problems”Footnote 16 – terms repeated by her husband, civil rights leader James Bevel, at the Spring Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam in April 1967, an action meant “to encourage cooperation between the peace and civil rights movements.”Footnote 17 Indeed, observers noted the diversity of both the crowd and march leaders, who included renowned white pediatrician Benjamin Spock alongside Martin Luther King, Jr. James Bevel proclaimed a simple purpose for that rally: to protest “the mass murder of people, period.”Footnote 18

The potential double meaning of Bevel’s comment should not go unremarked: it connected the, at times state-sanctioned, violence met by nonviolent civil rights protestors to the violence enacted upon Vietnamese civilians by US military action. Bevel’s statement echoes the above-mentioned 1965 editorial in Freedomways that “connect[ed] Selma and Saigon,” declaring that, “the very day that 3,500 U.S. troops were landing in Vietnam, the Negro citizens of Selma, Alabama, were being beaten, tear-gassed, and smoke bombed by Alabama State police for trying to march in peaceful protest against being denied the right to vote.”Footnote 19 The piece further argued that the United States’ refusal to uphold the civil rights of African Americans directly related to its abandonment of free elections in South Vietnam.Footnote 20 A 1966 statement made by members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and other articles written by civil rights advocates made similar points linking violence and injustice faced by Blacks in the United States with violence and injustice in South Vietnam.Footnote 21

Figure 4.1 Dr. Benjamin Spock (seated) holding a press conference with leaders of the Spring Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam (April 1967). James Bevel is on the far right.

Similarly, Hanoi and the National Front for the Liberation of Southern Vietnam (NLF, or Viet Cong) made use of racial unrest in the domestic United States in an attempt to illustrate the comparable treatment of Vietnamese and African Americans at the hands of the US government. Western news outlets provided much of the content for these portrayals; in fact, people’s diplomat Pham Van Chuong stated in 2015 that part of his mission as a correspondent in Eastern and Western Europe during the war years was to monitor Western news sources and disseminate bulletins about recent events.Footnote 22 Hanoi and the NLF may have also incorporated information shared by American activists to influence the word choices in their English-language propaganda – one activist recalled Vietnamese at an international antiwar conference asking for suggestions on slogans meant to encourage GIs to desert.Footnote 23 Regardless of the source of information, Hanoi’s and the NLF’s French- and English-language periodicals, Vietnam Courier and South Viet Nam in Struggle, respectively, carried stories about race riots in the United States as a way to convince readers that the US government acted unjustly toward its own people as well as toward the Vietnamese. Many activists recalled Hanoi officials claiming that the US government, not the American people, was the enemy, and this line of reasoning asserted that Hanoi could rely on civil rights activists for support.

Civil rights leaders also wondered whether African Americans were being sent to fight in Vietnam to deflect charges of racism as a motivation for the war – that is, the presence of Black GIs in Vietnam would disrupt images of the United States as an all-white nation invading a country composed of people of color.Footnote 24 In the context of the growing draft resistance movement,Footnote 25 Diane Nash and other civil rights advocates pointed out the disproportionate number of African American GIs serving in Vietnam, thereby adding a racial component to the heated debate over military service.Footnote 26 At the 1967 Spring Mobilization, civil rights speaker Stokely Carmichael “quipped that the draft was ‘white people sending Black people to make war on yellow people to defend land they stole from red people.’”Footnote 27 For her part, Diane Nash argued that it would be better for African American youth to refuse to serve and face prison terms than to risk their lives in a fight against other people of color.Footnote 28 Vietnamese officials must have caught wind of the debate over African American military service because in the late 1960s the NLF produced a number of pamphlets geared toward persuading Black GIs to desert.Footnote 29 Some of the pamphlets referenced specific events, such as Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination in 1968, while others featured more general arguments depicting racial discord within the United States. Taken together, all of the propaganda produced with an African American audience in mind made the point that Black Americans’ fight was at home against the US administration and American racism, not in Vietnam.

Hanoi’s courting of civil rights activists came at a moment of heightened debate within the Black Freedom Struggle. Namely, the SNCC, under the leadership of Stokely Carmichael, began to turn to more militant tactics and revolutionary rhetoric, popularizing the term “Black Power” and expelling whites from the organization.Footnote 30 Although the SNCC as an organization did not weather the storm that followed this transition, some activists, particularly those who included themselves in the emerging “Third World Left,”Footnote 31 embraced the idea of revolution as they identified themselves as anti-imperialists struggling alongside peoples of color in decolonizing nations.

At the same time, the US administration blamed antiwar protestors for a potential US military failure, and red-baiting continued to be a tactic to discredit activists. For instance, in his November 1969 “Silent Majority” speech, President Richard Nixon tapped into Americans’ fear of losing the war and found a scapegoat when he asserted that “North Vietnam cannot defeat or humiliate the United States. Only Americans can do that.”Footnote 32 More broadly, anticommunism permeated domestic debate over the war, causing distrust of antiwar actions and activists. Indeed, in 1965, when community organizers for SDS in Cleveland made known their antiwar stance, local community members, both Black and white, charged them with being communists.Footnote 33 Again, in the spring of 1970, members of Congress argued that the United States must be leery of any united front against the war because broadbased antiwar coalitions allowed for communist infiltration and exploitation.Footnote 34 Organizations that had survived red-baiting tactics in the 1950s remained on guard as they tried to maneuver around assumptions that they were communists who thought that “everything the United States does is wrong and everything Hanoi does is right.”Footnote 35 While some activists and organizations tried to work within the constraints of contemporary American society, others saw victory for North Vietnam as central to their struggle for social and economic justice in the United States.

Anti-imperialist Perspectives on US Intervention

As Asian American Alex Hing, minister of information for the Red Guard Party of San Francisco, explained in 1970, “If we take an anti-imperialist stand, then we clearly support the liberation struggles of the people of the world. In fact,” he continued, “we want the Vietnamese to win against US imperialism.”Footnote 36 The Black Panther Party agreed and put forward an image of themselves as having a unique bond with the Vietnamese as revolutionaries. This kind of alliance between African Americans and Asians was not new: during the early Cold War, such prominent African American activists as W. E. B. DuBois and Robert Williams expressed solidarity with the Chinese, and the Chinese government reciprocated. They defined their shared struggle as against US imperialism, racial discrimination, and economic injustice.Footnote 37 The Black Panthers, founded in 1966, built upon this foundation by citing Asian socialists as ideological visionaries, and in August 1970 Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver led an eleven-member Anti-imperialist Delegation, which included Alex Hing, on a three-month tour of North Vietnam, North Korea, and China. The Anti-imperialist Delegation was, in part, a way to create more tangible ties between the Black Panthers and Asian nations. The Vietnamese responded by hosting an International Day of Solidarity with Black Americans during the delegation’s visit. Vietnamese coverage of the commemoration praised the Black Power movement for meeting “violence with violence.”Footnote 38

As the presence of Alex Hing on the Anti-imperialist Delegation attests, the “Third World Left” in the United States extended beyond Black Power circles to include Asian Americans. Hing’s activism had roots in the recent identification of Asian Americans with the Vietnamese as a people sharing a common racial identity. Prior to the 1960s, Asian American communities within the United States usually grouped themselves by ethnicity, thus undermining the possibility of racial solidarity.Footnote 39 In the 1960s, with a generation of Asian American youth attending college in unprecedented numbers and joining student protest movements, they forged interethnic relationships based on common experiences as Asian Americans. Activists noted that American society often treated all people of Asian descent in a similar manner – either considering them as “Asians in America” or ignoring them altogether.Footnote 40 In the context of the Vietnam War, Asian Americans faced racial discrimination – for example, being called “gook,” a racial epithet used against the Vietnamese – that identified them as “the enemy” and cemented a racial bond.Footnote 41 In turn, some activists developed particular antiwar narratives by adopting the idea that they were uniquely connected to the Vietnamese. Describing the war as “genocide” against Asians, they claimed it was a mere accident of birth that they themselves were living in the United States, not dying in Vietnam alongside their “Asian sisters and brothers.”Footnote 42 For some activists, their movement for social justice and their antiwar work became inseparable; the American war in Vietnam brought Asian Americans together for a common cause, but soon the war itself was seen as a symptom of the larger issue of US imperialism and anti-Asian racism. Activists folded antiwar protest into their push for social and economic justice for the “Third World” at home and abroad.Footnote 43

In a similar fashion to Black and Asian American activists, Chicanos incorporated antiwar protest into their social justice activism. Opposing the Vietnam War marked a historic shift in tactics for Mexican Americans. During World War II and the Korean War, Mexican Americans largely supported US war efforts and saw military service as a way to assimilate into white society. The discrimination Mexican American soldiers faced upon their return to the United States in the 1940s and 1950s, however, dampened enthusiasm for serving in the Vietnam War.Footnote 44 By 1970, the Chicano movement rejected Mexican American participation in the military as a means to gain equality and instead insisted that the Mexican American fight was at home in the United States, not in Vietnam, echoing statements made by civil rights advocates and Vietnamese propagandists. For some activists, the argument went no further, so while the war in Vietnam made them pause to reconsider how to gain social justice in the United States, their objection to the war did not greatly alter established antiwar slogans.

For other Chicano activists, however, US involvement in Vietnam paralleled the history of US imperialism in the Southwest. Contributors to the Chicano periodical El Grito del Norte, published in New Mexico, championed this portrayal of the war by directly likening the Vietnamese to Mexican Americans trying to preserve their culture and connection to ancestral lands. Given that the newspaper was dedicated to covering the land grant struggle of northern New Mexico and southern Colorado, such a depiction may have helped to explain to readers why editor-in-chief Elizabeth “Betita” Martínez chose to cover the American war in Vietnam in its pages at all.Footnote 45 But for Martínez, the reason was simple: she believed there was “a great big connection between colonialism and racism.”Footnote 46 Thus, with Martínez at the helm, El Grito covered struggles for independence happening all over the world.

When she had the opportunity to visit Hanoi in the spring of 1970, Martínez did not hesitate to witness the war herself. In North Vietnam, she paid particular attention to issues that paralleled those facing Mexican Americans – that is, the treatment of ethnic minorities, the availability of bilingual education, and the prosperity of agrarian communities. Upon her return, Martínez depicted the Vietnamese as peasants fighting for their land just like Mexican Americans in the Southwest. This portrayal repeated claims made by other El Grito contributors covering the US war in previous issues.Footnote 47 But Martínez also felt encouraged by the Vietnamese example: they seemed to have succeeded in creating self-sufficient cooperative communities, and she looked to incorporate what she had learned in Vietnam into the Chicano struggle in the Southwest by writing about it.

Women’s and Feminist Voices in Antiwar Circles

The previous examples make clear that international organizing against the war often found productive soil when rooted in transnational identities based on race, but the VWU also nurtured relationships specifically between women. Many women’s organizations reciprocated by creating an international antiwar network based on gendered assumptions about women – that is, as mothers, their utmost desire was to care for children and, in order to care for children, they had to end war. The Soviet-influenced Women’s International Democratic Federation (WIDF), for instance, hosted conferences about the Vietnam War and invited VWU members to speak to international audiences that included American observers. At these and other women’s conferences, VWU members described the woes of Vietnamese mothers and children as they simultaneously vilified the US government by showing how US actions destroyed families.Footnote 48 Telling compelling stories in speeches, open letters, and the VWU’s own periodical, Women of Vietnam, Vietnamese women provided easily adoptable and adaptable narratives to share with audiences around the world. The unique harm that women, as mothers, suffered seemed to be a safe argument that women from all nations could make to protest the war.

Maternalist arguments against war were neither new nor unique,Footnote 49 so what is more interesting is that, for some American women who had not originally seen their antiwar activism as based in their identity as women, their interactions with Vietnamese brought these possibilities to light. For 21-year-old white SDS member Vivian Rothstein, her attendance at an antiwar conference that took place in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia in September 1967 marked the moment she first became aware of her potential role as a woman protesting the war, thanks to the VWU. At first glance, the conference between about forty American activists and twenty North Vietnamese and NLF representatives seems an unlikely place for Rothstein to have made such a discovery. American historians have labeled the conference an embarrassment to the antiwar movement,Footnote 50 despite the praise it originally received in contemporary reports and in Vietnamese accounts.Footnote 51 The conclusion of American scholars stems from conference organizer Tom Hayden being quoted in Newsweek as stating something like, “Now we’re all Viet Cong,” an assertion that lacked any subtlety, played into charges that communists led antiwar organizations, and alienated mainstream Americans.Footnote 52 The larger issue was the seemingly uncritical and naive acceptance of Vietnamese propaganda by these activists. Indeed, many American participants at the Bratislava conference, as well as antiwar activists more generally, had difficulty criticizing the Vietnamese, especially in public. Even so, in private, Americans admitted that direct contact with Vietnamese led to new understandings of them as people (who had faults), not simply victims.Footnote 53 Regardless of Hayden’s alleged impolitic statement, the Bratislava conference was one of the first transnational meetings between Americans and Vietnamese,Footnote 54 and it successfully brought together a variety of American activists representing religious, Black Power, academic, pacifist, and other groups, at a time when such alliances were strained.

In the preceding months, some antiwar activists, particularly those who took part in the counterculture, began to see resistance, disruption, and civil disobedience as necessary tactics not only to end the war in Vietnam, but also to create a new society. Other antiwar activists, such as those in the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE), wanted to continue to rely on legal and peaceful protests to push for “democratic means to bring about change.”Footnote 55 Events leading up to the October 1967 March on the Pentagon, a demonstration of 100,000 Americans in the nation’s capital, illustrate this split even as a coalition of organizations decided to hold two simultaneous demonstrations – one that included civil disobedience and one that did not – as a compromise. Countercultural influence on aspects of the October 1967 March – which included levitating the Pentagon to exorcise its demons – brought a realm of the absurd to the demonstration, to the consternation of many. In contrast, face-to-face meetings with Vietnamese brought a sense of urgency and responsibility to antiwar activism.

For Vivian Rothstein, the significance of the Bratislava conference stems from her attendance at an all-woman session – this was only the second time she had participated in such a meeting, and she had not initially seen any point in separating women from men. But the Vietnamese had urged such a meeting because they believed that women were particularly effective at communicating antiwar messages, and they wanted to be sure to share Vietnamese women’s experiences of the war with American women.Footnote 56 Consequently, when the Vietnamese invited a smaller number of Americans from the Bratislava conference on to Hanoi, they insisted that women be included on the seven-person delegation. Rothstein firmly believes that only because of this request, she and Carol McEldowney, white SDS member and community organizer in Cleveland, soon found themselves on a plane headed toward a war zone.Footnote 57

In Hanoi, the VWU again requested Rothstein and McEldowney meet with them separately in order to discuss women’s concerns. Despite her hesitancy to attend the all-woman session in Bratislava, in North Vietnam, Rothstein came to see the VWU as an example of a successful broadbased women’s coalition. At meetings in Hanoi and in the surrounding countryside, Rothstein learned about the organization of the VWU – women at the village and provincial levels held workshops, opened childcare centers, and established health clinics to support community members. At the national level, the VWU had a voice in the Politburo. The purpose of the VWU, which was founded in 1930, was to educate and empower women in North Vietnam; a 1965 issue of Women of Vietnam demonstrated just how successful the organization had been since 1945, when Hồ Chí Minh declared independence, by providing statistics on the increased number of day-care centers, women’s educational opportunities, and women’s political appointments. The VWU inspired Rothstein to form the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union (CWLU) upon her return to the United States. Her hope was to create a similar political force made up of American women that would have an expansive agenda. As she envisioned it, the CWLU would take up such issues as childcare needs and women’s empowerment.

Despite the new direction in which Rothstein found her activism headed, she continued her antiwar efforts, giving hundreds of talks and working in antiwar organizations. Rothstein felt significant pressure placed on her by her Vietnamese hosts, who made it clear that “they depended on us.” “It was a big deal,” she explained, “for adults to invest that kind of hope and responsibility in us. For me,” she continued, “it was transformative.” So, although the Vietnamese example inspired her to become “an organizer of women,” she continued her antiwar activism.Footnote 58

Rothstein’s experiences were in many ways representative of other white women’s liberationists of her generation. Although the VWU’s reliance on maternal and familial language to appeal to women around the world was off-putting to some young American women seeking to remake traditional gender roles and family structures, others somehow forgave Vietnamese women for such “old forms” of performing gender.Footnote 59 Perhaps the fact that the VWU promoted Vietnamese women fighting for “women’s liberation” and national liberation simultaneously provided enough of a commonality that members of this younger generation could look past incompatibilities between the groups.

Indeed, according to a Vietnamese proverb, “proper” womanhood married women’s loyalty to family with their loyalty to the nation; this meant that women could take up arms to defend the nation as part of their role as good wives and mothers. It declares, “When war strikes close to home, even the women must fight.”Footnote 60 During the US war years, the VWU fleshed out this doctrine by putting forward the “three responsibilities”Footnote 61 of Vietnamese women – to take up arms to defend villages, to produce food and goods in men’s absence, and to care for children. By the late 1960s, this prescription of Vietnamese womanhood came to be paired in US and transnational antiwar circles with an image of a Vietnamese woman holding a rifle in one hand and a baby close to her breast in the other arm. This depiction of the “woman warrior” was recreated in publications geared toward white women’s liberationists, Chicanas, Black activists, and Asian American women alike. It spoke to each of these constituencies in a different fashion, however. For instance, for many Chicanas, such illustrations showed that women could join the revolutionary struggle and maintain their femininity as mothers – an important ideal in many Mexican American communities.Footnote 62 This interpretation of the “woman warrior” related fairly closely to the Vietnamese ideal, but those who wanted to shake off the shackles of marriage or motherhood would have seen ways in which the Vietnamese version of “proper” womanhood fell short, if they had looked closely. In fact, some Vietnamese expressed surprise when they learned of the sexual revolution taking place in the United States that separated sex, marriage, and procreation.Footnote 63 But it seems that neither VWU members nor American women’s liberationists wanted to scrutinize the other side too closely; instead, “they look[ed] for those ways in which we are the same.”Footnote 64

Young American women, regardless of their race, and their Vietnamese counterparts seemed to agree that the image of the “woman warrior” would attract a base of female support to oppose the war. In 1969, “following the death of Hồ Chí Minh,” writes historian Lien-Hang T. Nguyen, “leaders in Hanoi sought to present a new face of the Vietnamese revolution.”Footnote 65 They chose Nguyễn Thị Bình to act as foreign minister for the Provisional Revolutionary government of the Republic of Southern Vietnam (PRG) at the Paris Peace Talks because she could embody the “woman warrior” on the international stage. Besides, she had the right credentials. Bình came from a revolutionary family: her grandfather, Phan Châu Trinh, resisted French colonialism in the late nineteenth century and supported reformation of Vietnamese society. In 1945, Bình joined the Việt Minh in resisting the French and was arrested in 1951. After her release in 1954 and after the signing of the Geneva Accords splitting Vietnam in two along the 17th parallel, Bình regrouped to the North, where she married, had two children, and studied at the Nguyễn Ái Quốc Political Academy. When the NLF was formed in 1960, Nguyễn Thị Bình took up a new post, concentrating on people’s diplomatic efforts. That meant that throughout the early 1960s, Bình attended international conferences where she promoted the NLF’s cause. When Bình became foreign minister of the PRG in 1969, Lien-Hang T. Nguyen argues, her position advanced Hanoi’s portrayal of Vietnam as a woman warrior in contrast to the United States, which was presented as a masculine invader in Vietnamese propaganda.Footnote 66

Such a depiction resonated with women’s liberationists in the United States who analyzed gendered aspects of US involvement in Vietnam. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, women’s liberationists grappled with how to create a movement that spoke to their desire to end all forms of oppression, as seen in the statement by Ellin Hirst that opened this chapter. Hirst was a white member of the feminist collective Bread and Roses in Boston, and was connected to a network of women’s liberation organizations across the country. In July 1969, she attended a women’s antiwar conference in Canada hosted by two women’s peace organizations, where she met people’s diplomat Nguyễn Ngọc Dung. Ngọc Dung worked closely with Nguyễn Thị Bình and traveled to Canada with two other Vietnamese women to inform American audiences about their perspectives on the war and its effects on their lives. During the conference, Ngọc Dung met separately with a group of women’s liberationists and spoke of the difficulties women in the resistance movement faced in terms of male chauvinism. She informed the young American women that once Vietnamese women showed how useful they could be in terms of reconnaissance and village defense, however, they earned men’s respect. Nevertheless, the fight for equality continued in terms of political representation and would continue long after the war ended, Ngọc Dung predicted. For Hirst, this conversation reassured her that fighting for women’s liberation was not divisive or selfish, but part of the necessary steps needed to form a revolutionary society. “It was really important to have our movement and our feelings seem legitimate,” Hirst concluded.Footnote 67

Ellin Hirst’s determination came at a key moment in antiwar dissent. In the summer of 1969, two newly formed antiwar coalitions, the Vietnam Moratorium Committee (VMC) and the New Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam (the New Mobe), took contrasting stances on whether antiwar activists and organizations should focus on multiple issues or on the single issue of the war. While leaders in the New Mobe sought to form a broadbased and radical antiwar coalition that would transform US society, the VMC committed to focusing on the single issue of the war and holding local demonstrations. Despite their divergent methods and purposes, both coalitions organized successful protests that fall. On October 15, 1969, an estimated 2 million Americans took part in VMC-sponsored events across the country, calling attention to widespread antiwar dissent. Historians have since credited these protests with preventing President Nixon from increasing US military intervention in Vietnam that November.Footnote 68 One month later, the two coalitions cooperated in organizing complementary actions, which included over 45,000 protestors participating in the somber March against Death that passed the White House, where each demonstrator, in turn, said either the name of an American soldier killed in action or the name of a Vietnamese village razed during the warfare. With participants marching in single file, the demonstration lasted thirty-six hours. Neither demonstration, however, called explicit attention to the ways in which the US war reflected or exacerbated domestic issues.

Having been encouraged by Vietnamese women, women’s liberationists active in the New Mobe set about theorizing why the war was a feminist issue. Information coming out of South Vietnam helped them make connections between women’s objectification and militarism. By the late 1960s, Vietnamese people’s diplomats and North Vietnamese periodicals made the case that US involvement in South Vietnam led women in Saigon to turn to prostitution as a means of survival, caused birth defects because of the spraying of chemical defoliants, and allowed rape and sexual assault perpetrated by American GIs and US-supported Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) soldiers to go unpunished.Footnote 69 Women’s liberationists repeated these claims as evidence of the gendered nature of war and the problematic role the US military played in creating a degenerative society in South Vietnam.

By contrast, the twin narrative of women’s accomplishments in North Vietnam seemed to illustrate to American women that the North was moving on a path toward creating a revolutionary and egalitarian society.Footnote 70 Contrasting North and South Vietnam meant comparing women’s situation under socialism and capitalism. Believing that women in the North were close to achieving women’s liberation, unlike their “sisters” in the South, American women’s liberationists blamed capitalism and imperialism for women’s inequality. The US war and the way it was waged were argued to be a symptom of patriarchal and capitalist society.Footnote 71 Thus, American women’s liberationists formed feminist analyses of the war and its connection to US society in a way that informed their antiwar narratives and feminist activism.

Conclusion

The American war in Vietnam served as a touchstone for many activists in the 1960s and 1970s as they came to analyze the US government through a new lens. It was neither just the war nor just their own community’s problems – the two were intertwined and were both symptoms of underlying diseases in US society. Cross-over between groups occurred as representatives of different organizations attended the same meetings and met with the same Vietnamese people’s diplomats. Although individual activists and organizations disagreed on the best strategy to end the war and the best tactic to oppose it, peace activist Barbara Deming’s assertion that “we are all part of one another” speaks to the hopes and frustrations of many antiwar activists.Footnote 72

Gaining firsthand perspectives on the war remained central for many American activists throughout the US war years as they tried to develop nuanced narratives “to explain the war and its consequences at home and abroad.”Footnote 73 While these kinds of arguments attracted some segments of the American population to see the war as a salient issue to their communities, others continued to see it as an aberration or, indeed, as necessary. Regardless, evidence suggests that growing antiwar sentiment undercut Washington at a few key moments. For Hanoi, widespread antiwar dissent in the United States could boost domestic morale in North Vietnam at the same time that evidence of social and economic injustices in the United States undermined Washington’s portrayal of the war as supporting freedom and democracy. Both American and international audiences came to see the deterioration in South Vietnamese society as evidence of the unjustness of US intervention, as well as being related to domestic injustices. Transnational alliances forged with Vietnamese created opportunities for American activists involved in a web of social movements to see their antiwar work as a central component of their activism toward a more just American society.