Suicide is an important global healthcare issue, and suicide rates vary according to region, gender, age, time, ethnic origin and, to a certain extent, practices of death registration. Reference Hawton and van Heeringen1 In Japan, the annual number of suicides rose sharply to 30 000 in 1998, and has remained high to the present day. 2 In 2012, suicide was the seventh major cause of death in Japan. Moreover, the suicide rate in Japan is the highest among all high-income countries. 2 Therefore, suicide prevention is a major target of public health efforts.

Ajdacic-Gross et al Reference Ajdacic-Gross, Weiss, Ring, Hepp, Bopp and Gutzwiller3 used mortality data from the World Health Organization to illustrate great variations in the preferred method of suicide across countries. They commented that the main methods of suicide typically change very slowly except for suicide by charcoal burning (carbon monoxide poisoning by burning charcoal in a closed space). Epidemics of charcoal burning suicide in Hong Kong and Taiwan began in the late 1990s. Reference Liu, Beautrais, Caine, Chan, Chao and Conwell4-Reference Law, Yip and Caine10 In Hong Kong, only 16 people died by suicide from charcoal burning in 1998; however, this number increased to 276 in 2002. Reference Liu, Beautrais, Caine, Chan, Chao and Conwell4 Similarly, in Taiwan, only 32 people died by suicide from charcoal burning in 1998, but this number increased to 1346 in 2005. Reference Lin, Chang and Lu5 The dramatic increase in charcoal burning suicide in Hong Kong and Taiwan is worth noting. In Japan, an epidemic of charcoal burning suicide also emerged from 2003. Reference Yip and Lee8,Reference Hitosugi, Nagai and Tokudome11 In February 2003, one man and two women, all strangers, formed a pact and killed themselves by burning charcoal. Reference Yip and Lee8,Reference Hitosugi, Nagai and Tokudome11 This incident attracted a lot of media attention and initiated a number of copycat suicide pacts in the following months. Since then, this disturbing trend has been creeping across Japan, with charcoal burning frequently used in suicide pacts. The reason for this is that charcoal is easily obtained in shops and the method is recognised as being simple and painless. The Complete Manual of Suicide is a Japanese book written by Wataru Tsurumi, Reference Tsurumi12 which was first published in 1993. It provides explicit descriptions and analyses of a wide range of suicide methods such as overdosing, hanging, jumping and carbon monoxide poisoning. However, the charcoal burning method was not listed in this book, and as such, was not yet a popular suicide method among Japanese at that time.

Although social, economic, cultural and psychological factors are significant contributors to suicide rates there is good evidence that the changing availability and popularity of lethal methods is also important. Reference Cantor and Baume13,Reference Florentine and Crane14 Compared with the number of population studies conducted on the impact on overall suicide rates when a specific method is restricted, little attention has been paid to the impact of newly emerging methods on overall suicide rates. Reference Thomas, Chang and Gunnell7 Thus, the rapid emergence of burning charcoal indoors as a source of toxic carbon monoxide for taking one’s own life provides a unique opportunity to study the impact of method availability on overall suicide rates. Whether a specific method results in death is related to both its lethal properties and its accessibility, and the case fatality rate of suicide methods varies greatly. Reference Yip, Caine, Yousuf, Chang, Wu and Chen15 The case fatality rates for firearms (80-90%), building jumping (70%), drowning (65-80%) and hanging (60-85%) are estimated to be high, whereas the rate for medication overdose (1.5-4%) is low. The case fatality rates for charcoal burning (40-50%), car exhaust gas (40-60%) and bridge jumping (35-60%) are estimated to be modest. The case fatality rate of pesticides ingestion (6-75%) has a comparatively wide range. Therefore, if the charcoal burning suicide method appeals to individuals who would have used other highly or relatively lethal methods, the emergence of this method may consequently result in little or no increase in overall suicide rates and a substantial decrease in other method-specific suicide rates. On the other hand, if this method appeals to many individuals who might not have used other highly or relatively lethal methods available, the emergence would lead to a substantial increase in overall suicide rates and little or no decrease in other method-specific suicide rates. Reports from both Hong Kong and Taiwan have indicated that the emergence of charcoal burning methods is associated with an increase in overall suicide rates, and almost no decrease in other method-specific suicide rates. Reference Liu, Beautrais, Caine, Chan, Chao and Conwell4,Reference Thomas, Chang and Gunnell7,Reference Law, Yip and Caine10 However, in Japan, little is known about the impact of charcoal burning suicide on overall and other method-specific suicide rates. Therefore, in order to address this question, we examined the impact of the charcoal burning suicide epidemic on overall and other method-specific suicide rates in Japan.

Method

Data sources

The number of deaths from suicide by gender, age (5-year age bands) and the ICD-10 codes between 1998 and 2007 was obtained from the Vital Statistics of Japan. 16 To identify the method of suicide, the underlying cause of death according to ICD-10 was used. 17 Data on suicide victims 14 years old or younger were not analysed in this study. Yearly age standardised rates were calculated for those aged 15 years and over using the World Standard population. Reference Ahmad, Boschi-Pinto, Lopez, Murray, Lozano and Inoue18

Following ICD-10, all reportable deaths with an external cause code in the range from X60 to X84, that occurred in the study period, were classified as suicide. 17 For the purpose of this study, since there is no specific ICD code for suicide from carbon monoxide poisoning due to charcoal burning, we followed the practice that all reportable deaths with an external cause code of X67 that satisfied the definition of ‘intentional self-poisoning by and exposure to other gases and vapours’ were included as charcoal burning suicide. Reference Liu, Beautrais, Caine, Chan, Chao and Conwell4 Although this approach to coding the manner of death has been used before, it is potentially confounded by the inclusion of suicides by motor vehicle exhaust gas, other carbon monoxide sources, other specified gases and vapours, and unspecified gases and vapours. Based on data from the National Police Agency in Japan, Hitosugi et al Reference Hitosugi, Nagai and Tokudome11 investigated the number of suicides by charcoal burning in 2007. They reported that 8.2% of all suicides were by charcoal burning (males: 10.0%, females: 4.0%). Based on data from the Vital Statistics of Japan, 9.9% of reportable deaths with an ‘X60 to X84’ code corresponded to those with an X67 code in 2007 (males: 11.9%, females: 4.9%). Therefore, we estimated that in 2007 about 80% of reportable deaths with an X67 code were charcoal burning suicides.

Period of time under study

From 1997 to 1998, the number of suicides in Japan had increased by 34.7%, and reached more than 30 000 per year. 2 The economic recession in the 1990s is thought to have led to this dramatic increase in suicides. Reference Andrésa, Haliciogluc and Yamamurad19 Since then the annual suicide rate in Japan has remained at around 25 per 100 000. The charcoal burning suicide epidemic in Japan emerged in 2003. Reference Yip and Lee8,Reference Hitosugi, Nagai and Tokudome11 However, from January 2008 there was a large increase in suicide attempts using homemade hydrogen sulfide gas. 20,Reference Morii, Miyagatani, Nakamae, Murao and Taniyama21 Compared with 2007, there was substantially increased use of this method. Since there is no specific ICD code for suicide by hydrogen sulfide gas, hydrogen sulfide suicides are included in deaths with an external cause code of X67, which also includes charcoal burning suicide. For this reason we chose 2007 as the final year for our time series analysis. Consequently, in this study, the period between 1998 and 2002 is considered to be the pre-epidemic period of charcoal burning suicide, whereas 2003-2007 is when the epidemic occurred.

Statistical methods

All analyses were conducted separately for males and females. Suicide method was dichotomised into charcoal burning (X67) or other methods (not X67). Age was stratified into the following four groups: 15-24, 25-44, 45-64 and 65+ years.

For the analysis of age-adjusted suicide rate trends by gender, age and methods used in Japan between 1998 and 2007, we performed a joinpoint regression analysis using the Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.0.4 for Windows (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, http://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/).

Joinpoint regression is a log-linear model that uses Poisson regression, creating a Monte Carlo permutation test to identify points where the trend line changes significantly in magnitude or in direction. Reference Kim, Fay, Feuer and Midthune22 The analysis starts with the minimum number of joinpoints (a zero joinpoint, which is a straight line) and tests whether one or more joinpoints are significant and should be added to the model. In the final model each joinpoint (if any was detected) indicates a significant change in the slope. The maximum number of joinpoints, minimum number of observations from a joinpoint to either end of the data and minimum number of observations between two joinpoints were set at one, three and four respectively (default settings). The estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) and 95% confidence interval were estimated for the time segments on both sides of the inflection points. In addition, in order to compare the estimated changes in the age-adjusted suicide rates during the overall research period (1998-2007), the pre-epidemic period (1997-2002) and the epidemic period (2003-2007), the average annual percentage change (AAPC) was calculated. The AAPC is a summary measure that is computed, over a fixed interval, as a weighted average of the slope coefficients of the joinpoint regression with the weights equal to the length of each detected segment over the interval. When no joinpoint is detected, the AAPC coincides with the EAPC.

All analyses, with the exception of the joinpoint regression, were performed using Stata statistical software, version 12.1, for Macintosh. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P-value of <0.05. To examine the influence of charcoal burning suicide on overall suicide epidemiology in Japan between 1998 and 2007, negative binomial regression analyses were performed using the number of suicides per year and age groups as the outcome variable. Negative binomial regression is Poisson regression with an additional gamma distributed parameter to adjust for overdispersion (extra-Poisson variation) in the data. The regression equation contained a dummy variable (D) as an independent variable that took the value 0 or 1 to indicate the pattern of charcoal burning suicide in the pre-epidemic period (0) or in the epidemic period (1) respectively. Thus, the estimated slope coefficient (β) from the regression model represents the effect size attributable to the charcoal burning suicide epidemic. In addition, to adjust for the age difference in suicide rate and the population growth rate for the 10-year period under study, we also included age at suicide and the offset term of mid-year population size of corresponding year into the regression equation as the confounding variables. Mathematically, the regression equation is written as follows:

In principle, a change in the number of suicides can just be attributable to an underlying annual time trend in epidemiology instead of the influence of an epidemic of charcoal burning suicides. Thus, when analysing the long-term influence of an epidemic, any significant transition trend needs to be taken into consideration. To adjust for the time trend of suicide rate, we added the year of suicide to Model 1 as a confounding variable. This model assumed that the annual trend was uniform over the research period. Mathematically, the regression equation is written as follows:

In order to evaluate the impact of the charcoal burning suicide epidemic on overall and method-specific suicide rates in Japan, we fitted overall and method-specific suicides into the model. If the number of overall suicides in the epidemic period was significantly larger (β>0), the epidemic of charcoal burning suicide would lead to an increase in the number of overall suicides. In addition, it is important to ascertain whether charcoal burning displaced suicidal individuals from other lethal methods. To assess the potential for means-substitution, we fitted other suicide methods into the aforementioned model. If the effect of displacement does not exist, the number of other methods of suicide in the epidemic period should not be significantly smaller (β<0) when compared with the pre-epidemic period. In addition, we investigated evidence of statistical interaction between the epidemic pattern of charcoal burning suicide and gender with the suicide outcomes.

Separate analyses were also conducted for the following age groups: 15-24, 25-44, 45-64 and 65+. When we performed the separate analyses by age groups, the regression equations are written as follows:

To quantify the effect size of the charcoal burning suicide epidemic we modified the formula by Law et al Reference Law, Yip, Chan, Fu, Wong and Law23 to estimate the average percentage change (APC) in the number of suicides between the pre-epidemic and epidemic periods as follows:

The 95% confidence interval for the APC was calculated with negative binomial regression in a corresponding manner.

In addition, we carried out sensitivity analyses to assess any effects of possibly misclassified cases of suicide. All reportable deaths with an external cause code in the range from X10 to X34 (event of undetermined intent) that occurred in the study period, were included as suicide, and a code of Y17 was included as charcoal burning suicide.

Results

The ten most popular suicide methods based on ICD-10 code in 1998 and 2007 are shown in Tables 1 and 2. In males, the ranking of X67 had risen from third place in 1998 to second place in 2007 (Table 1). In females, it had risen from eighth place in 1998 to fourth place in 2007 (Table 2). In both 1998 and 2007, the contribution of X67 to overall suicides in females is smaller than that in males.

Table 1 Ten leading suicide methods based on ICD-10 code in males in Japan, 1998 and 2007Footnote a

| Rank | ICD-10 code | n (%)Footnote a |

|---|---|---|

| 1998 | ||

| 1 | X70 Hanging, strangulation and suffocation | 15 843 (70.9) |

| 2 | X80 Jumping from a high place | 1826 (8.2) |

| 3 | X67 Other gases and vapours | 1410 (6.3) |

| 4 | X76 Smoke, fire and flames | 615 (2.8) |

| 5 | X71 Drowning and submersion | 586 (2.6) |

| 6 | X78 Sharp object | 563 (2.5) |

| 7 | X81 Jumping or lying before moving object | 513 (2.3) |

| 8 | X68 Pesticides | 473 (2.1) |

| 9 | X83 Other specified means | 156 (0.7) |

| 10 | X61 Antiepileptic, sedative-hypnotic, etc. | 143 (0.6) |

| 2007 | ||

| 1 | X70 Hanging, strangulation and suffocation | 15 555 70.7) |

| 2 | X67 Other gases and vapours | 2615 (11.9) |

| 3 | X80 Jumping from a high place | 1497 (6.8) |

| 4 | X78 Sharp object | 506 (2.3) |

| 5 | X81 Jumping or lying before moving object | 420 (1.9) |

| 6 | X71 Drowning and submersion | 401 (1.8) |

| 7 | X76 Smoke, fire and flames | 306 (1.4) |

| 8 | X68 Pesticides | 241 (1.1) |

| 9 | X61 Antiepileptic, sedative-hypnotic, etc. | 154 (0.7) |

| 10 | X83 Other specified means | 87 (0.4) |

a. Percentages in the table are based on a total n = 22 349 for X60-X84 in 1998 and a total n = 22 007 for X60-X84 in 2007.

Total number of charcoal burning suicides in the pre-epidemic (1998-2002) and epidemic (2003-2007) periods by gender and age group are shown in Table 3. There were 152 743 suicides in Japan (males: 109 169, females: 43 574) during the pre-epidemic period, and 153 657 suicides (males: 111 013, females: 42 644) in the epidemic period. During both periods, the proportion of X67 suicides out of total suicides was larger in males than in females. Regardless of age group or gender, the proportion of X67 suicides out of total suicides during the epidemic period increased compared with that of the pre-epidemic period. With regard to males, during the epidemic period, the proportion was overrepresented in the 25-44 age group and smallest in the 65+ age group. For females, it was relatively large in the 15-24 and 25-44 age groups and smallest in the 65+ age group.

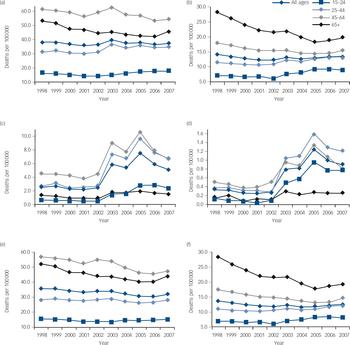

Time trends in age-adjusted suicide rates by gender, age group and method-specific use between 1998 and 2007 are presented graphically in Fig. 1. The results of joinpoint regression analyses are summarised in Tables 4 and 5. The overall suicide rate in males of all ages remained comparatively flat from the pre-epidemic period through the epidemic period (Fig. 1(a) and Table 4). The trend in males aged 15-24 years significantly increased between 2001 and 2007, although it significantly decreased between 1998 and 2001. The trend in males aged 25-44 years significantly increased without a joinpoint throughout the research period. In females, the overall suicide rate trend for all ages significantly decreased between 1998 and 2001, whereas it significantly increased between 2001 and 2007 (Fig. 1(b) and Table 5). The trend in females aged 15-24 years significantly increased without a joinpoint throughout the research period. The trend in females aged 25-44 years significantly increased between 2001 and 2007, although it decreased between 1998 and 2001.

The X67 suicide rate in males of all ages tended to remain flat between 1998 and 2002, followed by a rapid increase from 2.4 to 5.9 per 100 000 between 2002 and 2003, peaking at 7.5 per 100 000 in 2005, and then dropping to 5.2 per 100 000 in 2007 (Fig. 1(c)). An increase in the rate in males between 2002 and 2003 was also observed among all age groups. The trends in males of all age groups increased without a joinpoint through the research period (Table 4). The AAPC of X67 during the epidemic period (2003-2007) in males aged 15-24 years was a comparatively large positive number, whereas the AAPCs in males from the other age groups were negative. The time trend in females of all ages is similar to that of males (Fig. 1(d)). It remained flat between 1998 and 2002, increased rapidly from 0.3 to 0.8 per 100 000 between 2002 and 2003, peaked at 1.2 per 100 000 in 2005, and then dropped to 0.9 per 100 000 in 2007. An increase in the rate in females between 2002 and 2003 was also observed among all age groups. The trends in females among all the age groups increased without a joinpoint through the research period (Table 5). The AAPCs of X67 during the epidemic period, in females of all ages and aged 15-24 and 25-44 years, were positive, whereas the AAPCs in females aged 45-64 and 65+ years were negative.

Table 2 Ten leading suicide methods based on ICD-10 code in females in Japan, 1998 and 2007Footnote a

| Rank | ICD-10 code | n (%)Footnote a |

|---|---|---|

| 1998 | ||

| 1 | X70 Hanging, strangulation and suffocation | 5768 (61.3) |

| 2 | X80 Jumping from a high place | 1200 (12.8) |

| 3 | X71 Drowning and submersion | 719 (7.6) |

| 4 | X68 Pesticides | 410 (4.4) |

| 5 | X76 Smoke, fire and flames | 329 (3.5) |

| 6 | X81 Jumping or lying before moving object | 324 (3.4) |

| 7 | X78 Sharp object | 200 (2.1) |

| 8 | X67 Other gases and vapours | 181 (1.9) |

| 9 | X61 Antiepileptic, sedative-hypnotic, etc. | 126 (1.3) |

| 10 | X64 Other and unspecified drugs, etc. | 54 (0.6) |

| 2007 | ||

| 1 | X70 Hanging, strangulation and suffocation | 5488 (62.2) |

| 2 | X80 Jumping from a high place | 1143 (13.0) |

| 3 | X71 Drowning and submersion | 506 (5.7) |

| 4 | X67 Other gases and vapours | 433 (4.9) |

| 5 | X81 Jumping or lying before moving object | 276 (3.1) |

| 6 | X61 Antiepileptic, sedative-hypnotic, etc. | 206 (2.3) |

| 7 | X76 Smoke, fire and flames | 194 (2.2) |

| 8 | X78 Sharp object | 180 (2.0) |

| 9 | X68 Pesticides | 176 (2.0) |

| 10 | X64 Other and unspecified drugs, etc. | 107 (1.2) |

a. Percentages in the table are based on a total n = 9406 for X60-X84 in 1998 and a total n = 8820 for X60-X84 in 2007.

Table 3 Sum of X67 suicides in the pre-epidemic (1998-2002) and epidemic (2003-2007) periods by gender and age groupFootnote a

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1998-2002 | 2003-2007 | |

| Males | ||

| All ages | 6750 (6.2) | 15 381 (13.9) |

| 15-24 | 248 (3.9) | 833 (13.6) |

| 25-44 | 2286 (8.6) | 6713 (22.0) |

| 45-64 | 3725 (7.1) | 6906 (13.9) |

| 65+ | 487 (2.2) | 916 (3.9) |

| Females | ||

| All ages | 792 (1.8) | 2356 (5.5) |

| 15-24 | 37 (1.4) | 249 (8.3) |

| 25-44 | 283 (3.1) | 1060 (9.8) |

| 45-64 | 393 (2.6) | 858 (6.3) |

| 65+ | 78 (0.5) | 179 (1.2) |

a. The percentages represent the proportions of X67 suicides out of total suicides by period, gender and age group. X67: ICD-10 code that includes suicides by charcoal burning and other gas poisoning.

In males, the rates by suicide using methods other than gassing for all ages, as well as for those aged 45-64 years tended to decrease without a joinpoint from the pre-epidemic period through the epidemic period (Fig. 1(e) and Table 4). In females, the suicide rate using methods other than gassing tended to decrease significantly for all ages between 1998 and 2001, and then remained comparatively flat between 2001 and 2007 (Fig. 1(f) and Table 5). In the sensitivity analyses including cases where cause of death was classified as undetermined intent (Y10-Y34), the results of the joinpoint regression analyses hardly changed (online Tables DS1 and DS2). In other words, the only difference was that the overall suicide rate trend in men aged 65 years or above significantly decreased without a joinpoint through the research period.

Table 4 Trends in age-standardised suicide rates by age and methods used in Japanese males aged 15 years or older, 1998-2007

| Jointpoint analyses (1998-2007) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segment 1Footnote a | Segment 2Footnote a | AAPC | |||||

| Period | EAPC | Period | EAPC | 1998-2007 | 1998-2002 | 2003-2007 | |

| Overall | |||||||

| All ages | 1998-2007 | −0.09 | −0.09 | −1.8 | −1.5 | ||

| 15-24 | 1998-2001 | −4.9Footnote * | 2001-2007 | 4.1Footnote * | 1.0 | −3.6Footnote * | 4.0Footnote * |

| 25-44 | 1998-2007 | 1.7Footnote * | 1.7Footnote * | −0.7 | −1.0 | ||

| 45-64 | 1998-2007 | −1.2Footnote * | −1.2Footnote * | −1.3 | −3.7Footnote * | ||

| 65+ | 1998-2005 | −3.2Footnote * | 2005-2007 | 3.8 | −1.7 | −4.4Footnote * | −0.2 |

| X67 | |||||||

| All ages | 1998-2007 | 13.6Footnote * | 13.6Footnote * | −2.8 | −1.2 | ||

| 15-24 | 1998-2007 | 23.4Footnote * | 23.4Footnote * | −7.2Footnote * | 14.8 | ||

| 25-44 | 1998-2007 | 15.9Footnote * | 15.9Footnote * | −2.7 | −0.5 | ||

| 45-64 | 1998-2007 | 9.8Footnote * | 9.8Footnote * | −1.6 | −5.3 | ||

| 65+ | 1998-2007 | 5.9 | 5.9 | −11.7Footnote * | −3.1 | ||

| Not X67 | |||||||

| All ages | 1998-2007 | −1.6Footnote * | −1.6Footnote * | −1.7 | −1.6 | ||

| 15-24 | 1998-2002 | −3.6Footnote * | 2002-2007 | 2.3Footnote * | −0.3 | −3.5Footnote * | 2.5 |

| 25-44 | 1998-2007 | −0.7 | −0.7 | −0.5 | −1.1 | ||

| 45-64 | 1998-2007 | −2.4Footnote * | −2.4Footnote * | −1.3 | −3.4 | ||

| 65+ | 1998-2005 | −3.5Footnote * | 2005-2007 | 4.2 | −1.9Footnote * | −4.2Footnote * | −0.03 |

EAPC, estimated annual percentage change; AAPC, average annual average percentage change; X67, ICD-10 code that includes suicides by charcoal burning and other gas poisoning; Not X67, ICD-10 code with an external cause code in the range from X60 to X84, except X67.

* EAPC or AAPC is statistically significantly different from 0 (two-sided P<0.05).

a. Segment 1 and Segment 2 are the time segments identified by the jointpoint regression analyses.

Average percentage changes in the number of method-specific suicides and age groups for males between 1998 and 2007 are shown in Table 6. Regardless of age group, significant increases in the APCs of X67 suicides were observed in both Model 1 and Model 2. For all ages, a significant increase of about 9% in the APC of overall suicides was observed in Model 2, although an increase of only about 2% was seen in Model 1. Whereas a significant decrease of about 7% in the APC of suicides using methods other than gassing was observed in Model 1, hardly any change in the APC was observed in Model 2.

Regarding stratified results by age group, increases of about 10% in the APCs of overall suicides in the 15-24 age groups were observed in both Model 1 and Model 2, and significant increases of more than 10% in the APCs of overall suicides in the 25-44 age groups were also observed in both Model 1 and Model 2. A marginally significant increase of about 8% in the APC of overall suicides in the 45-64 age group was observed in Model 2, although a decrease of about 4% was seen in Model 1. Furthermore, although significant decreases of more than 10% in the APCs of suicides using methods other than gassing in the 45-64 and 65+ age groups were observed in Model 1, only small changes were observed in Model 2. The results of the sensitivity analyses indicated that the APCs in Model 1 and Model 2 for males were less affected when undetermined intent cases were included (online Table DS3).

Average percentage changes in the number of method-specific suicides and age groups for women between 1998 and 2007 are shown in Table 7. Regardless of age group, significant increases in the APCs of X67 suicides were observed in both Model 1 and Model 2. For all ages, an increase of about 9% in the APC of overall suicides was observed in Model 2, although an increase of only about 1% was seen in Model 1. A decrease of about 4% in the APC of suicides using methods other than gassing was observed in Model 1, whereas an increase of about 4% was seen in Model 2. Regarding stratified results by age groups, significant increases in the APCs of overall suicides in those aged 15-24 and 25-44 years were observed both in Model 1 and Model 2. Although significant decreases of more than 10% in the APCs of suicides using methods other than gassing in those aged 45-64 and 65+ years were observed in Model 1, small increases of 1.6-2.3% were seen in Model 2. For women, the APCs in Models 1 and 2 were also less affected when undetermined intent cases were included (online Table DS4).

Fig. 1 Trend in age-adjusted suicide rates by age group in Japan, 1998-2007.

(a) Overall suicides in males, (b) overall suicides in females, (c) X67 sucicides in males, (d) X67 sucicides in females, (e) Not X67 sucicides in males, (f) not X67 sucicides in females. X67, ICD-10 code that includes suicides by charcoal burning and other gas poisoning; Not X67, ICD-10 code with an external cause code in the range from X60 to X84, except X67.

Statistical analyses show that, for all ages, associations of the epidemic with suicide differed between males and females and was weak in suicides overall (P-value for interaction 0.975) or in suicides using methods other than gassing (P = 0.486), whereas statistical evidence was strong for suicides by charcoal burning or other gassing (P = 0.004).

Discussion

Main findings

This study examined the impact of the charcoal burning suicide epidemic on overall suicide rates and other method-specific suicide rates in Japan. The results showed that the epidemic resulted in an increase of about 9% in overall suicide rates for males and females of all ages in Model 2, although in Model 1 the epidemic hardly resulted in an increase in either gender. Since the epidemic did not necessarily affect overall suicide rates before adjustment for time trend, we need to carefully consider the impact on the overall suicide rate. Furthermore, the epidemic led to a significant decrease of about 7% in other-specific suicide rates in males in Model 1, and a decrease of about 4% in females. However, after adjustment for time trend, the epidemic did not necessarily result in a decrease in both genders. The stratified analyses by age group showed that, in males, the charcoal burning suicide epidemic led to an increase of about 10% in overall suicide rates in those aged 15-24 and an increase of more than 10% in those aged 25-44, without an apparent decrease in other method-specific suicide rates. Concerning females, the epidemic led to an increase of more than 20% in those aged 15-24, and an increase of more than 10% in those aged 25-44 years, without an apparent decrease in other method-specific suicide rates. However, in those aged 45-64 years and 65 years or above for both men and women, no such trend was observed. Therefore, these results suggest that, in 15- to 24- and 25- to 44-year-old males and females, the charcoal burning method appealed to many individuals who might not have used other highly or relatively lethal methods available and therefore led to an increase in overall suicide rates during the epidemic period in Japan. In addition, the time trend in age-adjusted rates of suicide using charcoal burning and other gas poisoning for males aged 15-24 years and females aged 15-24 and 25-44 years increased substantially during the epidemic period, whereas the trend for males aged 25-44 years appeared to be flat.

Table 5 Trends in age-standardised suicide rates by age and methods used in Japanese females aged 15 years or older, 1998-2007

| Jointpoint analyses (1998-2007) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segment 1Footnote a | Segment 2Footnote a | AAPC | |||||

| Period | EAPC | Period | EAPC | 1998-2007 | 1998-2002 | 2003-2007 | |

| Overall | |||||||

| All ages | 1998-2001 | −4.5Footnote * | 2001-2007 | 1.7Footnote * | −0.4 | −3.6Footnote * | 1.3 |

| 15-24 | 1998-2007 | 4.0Footnote * | 4.0Footnote * | −3.2Footnote * | 4.6 | ||

| 25-44 | 1998-2001 | −1.8 | 2001-2007 | 4.2Footnote * | 2.1Footnote * | −1.3 | 2.9Footnote * |

| 45-64 | 1998-2005 | −2.9Footnote * | 2005-2007 | 3.7 | −1.5 | −3.9Footnote * | −0.09 |

| 65+ | 1998-2005 | −5.6Footnote * | 2005-2007 | 3.1 | −3.7Footnote * | −6.9Footnote * | −2.7 |

| X67 | |||||||

| All ages | 1998-2007 | 19.0Footnote * | 19.0Footnote * | −5.4 | 4.0 | ||

| 15-24 | 1998-2007 | 29.8Footnote * | 29.8Footnote * | −13.8 | 11.5 | ||

| 25-44 | 1998-2007 | 20.2Footnote * | 20.2Footnote * | −7.4Footnote * | 4.2 | ||

| 45-64 | 1998-2007 | 12.9Footnote * | 12.9Footnote * | −0.9 | −0.4 | ||

| 65+ | 1998-2007 | 8.3 | 8.3 | −9.6 | −1.0 | ||

| Not X67 | |||||||

| All ages | 1998-2001 | −4.6Footnote * | 2001-2007 | 0.6 | −1.1 | −3.6Footnote * | 1.1 |

| 15-24 | 1998-2007 | 2.8Footnote * | 2.8Footnote * | −3.0 | 4.0 | ||

| 25-44 | 1998-2001 | −2.1 | 2001-2007 | 2.8Footnote * | 1.1 | −1.1 | 2.8 |

| 45-64 | 1998-2005 | −3.8Footnote * | 2005-2007 | 4.7 | −2.0Footnote * | −4.0Footnote * | −0.03 |

| 65+ | 1998-2005 | −5.7Footnote * | 2005-2007 | 3.1 | −3.8Footnote * | −6.9Footnote * | −2.7 |

EAPC, estimated annual percentage change; AAPC, average annual average percentage change; X67, ICD-10 code that includes suicides by charcoal burning and other gas poisoning; Not X67, ICD-10 code with an external cause code in the range from X60 to X84, except X67.

* EAPC or AAPC is statistically significantly different from 0 (two-sided P<0.05).

a. Segment 1 and Segment 2 are the time segments identified by the jointpoint regression analyses.

Table 6 Average percentage change (APC) between the pre-epidemic and epidemic periods of the number of suicides by method used and age group for males aged ⩾15 years, 1998-2007

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APC (95% CI) | P | APC (95% CI) | P | |

| All ages | ||||

| Overall | 1.77 (−2.39 to 6.10) | 0.411 | 8.97 (0.49 to 18.16) | 0.038 |

| X67 | 137.53 (106.71 to 172.95) | <0.001 | 165.26 (99.57 to 252.57) | <0.001 |

| Not X67 | −7.09 (−9.98 to −4.12) | <0.001 | −0.21 (−5.79 to 5.71) | 0.944 |

| 15-24 years | ||||

| Overall | 10.36 (2.45 to 18.88) | 0.009 | 9.65 (−6.03 to 27.94) | 0.242 |

| X67 | 287.67 (194.67 to 410.03) | <0.001 | 199.77 (72.20 to 421.83) | <0.001 |

| Not X67 | −0.86 (−6.87 to 5.53) | 0.786 | 2.15 (−9.98 to 15.92) | 0.741 |

| 25-44 years | ||||

| Overall | 13.89 (10.39 to 17.50) | <0.001 | 18.13 (11.51 to 25.15) | <0.001 |

| X67 | 190.34 (151.07 to 235.75) | <0.001 | 211.83 (131.81 to 319.46) | <0.001 |

| Not X67 | −2.75 (−6.16 to 0.78) | 0.125 | 0.74 (−5.83 to 7.77) | 0.831 |

| 45-64 years | ||||

| Overall | −4.41 (−9.71 to 1.19) | 0.121 | 7.78 (−0.07 to 16.25) | 0.052 |

| X67 | 88.12 (61.01 to 119.80) | <0.001 | 128.93 (72.74 to 203.40) | <0.001 |

| Not X67 | −11.46 (−16.33 to −6.31) | <0.001 | −1.24 (−9.03 to 7.22) | 0.766 |

| 65+ years | ||||

| Overall | -9.84 (-15.28 to -4.04) | 0.001 | 0.87 (−8.68 to 11.43) | 0.864 |

| X67 | 58.20 (33.53 to 87.44) | <0.001 | 126.99 (83.11 to 181.39) | <0.001 |

| Not X67 | −11.36 (−16.64 to −5.75) | <0.001 | −1.70 (−11.22 to 8.85) | 0.742 |

X67, ICD-10 code that includes suicides by charcoal burning and other gas poisoning; Not X67, ICD-10 code with an external cause code in the range from X60 to X84, except X67.

Table 7 Average percentage change (APC) between the pre-epidemic and epidemic periods of the number of suicides by method used and age group for females aged ⩾15 years, 1998-2007

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APC (95% CI) | P | APC (95% CI) | P | |

| All ages | ||||

| Overall | 1.27 (−5.50 to 8.52) | 0.722 | 8.87 (−5.26 to 25.10) | 0.231 |

| X67 | 215.42 (163.40 to 277.70) | <0.001 | 226.31 (125.2 to 372.64) | <0.001 |

| Not X67 | −3.58 (−9.37 to 2.59) | 0.250 | 4.03 (−8.05 to 17.68) | 0.531 |

| 15-24 years | ||||

| Overall | 27.91 (17.21 to 39.58) | <0.001 | 23.65 (3.34 to 47.95) | 0.020 |

| X67 | 677.03 (414.27 to 1074.03) | <0.001 | 486.60 (182.21 to 1119.30) | <0.001 |

| Not X67 | 18.85 (9.95 to 28.48) | <0.001 | 16.31 (−0.88 to 36.48) | 0.064 |

| 25-44 years | ||||

| Overall | 15.95 (10.81 to 21.33) | <0.001 | 11.14 (1.90 to 21.22) | 0.017 |

| X67 | 271.14 (205.30 to 351.18) | <0.001 | 274.53 (149.71 to 461.73) | <0.001 |

| Not X67 | 7.85 (3.02 to 12.90) | 0.001 | 3.45 (−5.26 to 12.96) | 0.450 |

| 45-64 years | ||||

| Overall | −8.69 (−13.45 to −3.66) | 0.001 | 1.02 (−6.90 to 9.62) | 0.807 |

| X67 | 122.32 (81.99 to 171.57) | <0.001 | 142.19 (61.87 to 262.35) | <0.001 |

| Not X67 | −12.19 (−17.16 to −6.92) | <0.001 | −2.95 (−11.67 to 6.64) | 0.534 |

| 65+ years | ||||

| Overall | −20.34 (−28.21 to −11.59) | <0.001 | 2.32 (−8.92 to 14.96) | 0.699 |

| X67 | 97.95 (51.73 to 158.26) | <0.001 | 125.80 (36.03 to 274.80) | 0.002 |

| Not X67 | −20.90 (−28.72 to −12.21) | <0.001 | 1.67 (−9.45 to 14.15) | 0.779 |

X67, ICD-10 code that includes suicides by charcoal burning and other gas poisoning; Not X67, ICD-10 code with an external cause code in the range from X60 to X84, except X67.

Comparison with epidemics in Hong Kong and Taiwan

The charcoal burning suicide epidemics in both Hong Kong and Taiwan preceded that of Japan. Reference Liu, Beautrais, Caine, Chan, Chao and Conwell4,Reference Thomas, Chang and Gunnell7,Reference Law, Yip and Caine10 In the former two countries, it was reported that the charcoal burning epidemic led to an overall increase in suicide rates, and this increase was most prominent among those in their middle years. In our study, we performed separate analyses by gender and age group. The results showed that the epidemic in Japan increased overall suicide rates in 15- to 24- and 25- to 44-year-old males and females only. Overall suicide rates before the emergence of charcoal burning suicide were 26.0 per 100 000 in Japan (in 1998), 13.3 in Hong Kong (1998) and 7.6 in Taiwan (1995), whereas those after the epidemic were 25.3 in Japan (2007), 16.4 in Hong Kong (2002) and 19.3 in Taiwan (2006). Reference Liu, Beautrais, Caine, Chan, Chao and Conwell4,Reference Pan, Liao and Lee9 Since the overall suicide rate before the emergence of charcoal burning suicide in Japan was considerably higher than those of Hong Kong or Taiwan, the impact of the charcoal burning suicide epidemic on overall suicide rates in Japan might have been restricted compared with the other two countries. Furthermore, it is possible that the introduction or increased use of one suicide method may result in a decline in other methods. Reference Cantor and Baume13 However, previous research has indicated that the emergence and growth of charcoal burning suicide in Hong Kong and Taiwan was not associated with a reduction in other methods of suicides. Reference Liu, Beautrais, Caine, Chan, Chao and Conwell4,Reference Thomas, Chang and Gunnell7,Reference Law, Yip and Caine10 In fact, the potential for means-substitution was found only among married Hong Kong women. Reference Law, Yip and Caine10 Our results also suggest that the potential for means-substitution was limited in Japan.

Japan is geographically close to Hong Kong and Taiwan, and the starting time of the epidemic in Japan was also temporally close to those of Hong Kong and Taiwan. However, from our investigation, we are unable to clarify whether the epidemic in Hong Kong and Taiwan had any effect on that of Japan. Further research is needed to examine the influence of the epidemic of charcoal burning suicide in Hong Kong and Taiwan on that of Japan.

Context of the epidemic

It is thought that several factors may have caused and promoted the rapid emergence and spread of charcoal burning suicides in Japan. First, previous studies have indicated that the way the suicide method was portrayed in the mass media played a key role in its rapid gain in popularity. Reference Liu, Beautrais, Caine, Chan, Chao and Conwell4,Reference Chan, Yip, Au and Lee6 In Hong Kong and Taiwan, having been portrayed through the media as a painless, non-violent, yet highly lethal way to kill oneself, charcoal burning swiftly became one of the most commonly used suicide methods. In Japan, previous studies of mass media reporting and subsequent suicide rates have also demonstrated a positive relationship between the two. Reference Stack24 Thus, the charcoal burning suicide epidemic in Japan since 2003 may also be attributable to mass media reporting. Reference Yip and Lee8 Moreover, for males aged 15-24 years and females aged 15-24 and 25-44 years, mass media reporting might have led to an increasing trend in age-adjusted rates of suicide using charcoal burning and other gas poisoning during the epidemic period. Media professionals should not only be made aware of the potential negative impact of the reporting of charcoal burning suicides (or any other methods of suicide that would be considered desirable by their audience), but also their potential role in suicide prevention through responsible reporting. Reference Chan, Lee and Yip25

Second, in the internet era, there is ample reason to anticipate an especially rapid spread if a new method appears comparatively more acceptable to vulnerable individuals than existing methods. Reference Alao, Soderberg, Pohl and Alao26 Since internet websites and chat rooms provide detailed information on suicide it has been argued that the internet may have a more direct influence on copycat suicides than do the print media. One of the first charcoal burning suicide victims in Taiwan explicitly stated that he learned of the method from a Hong Kong newspaper website. Reference Yip and Lee8 After the first internet-linked suicide pact in Japan in 2003, internet-linked suicide became more widespread. Reference Yip and Lee8

Third, it has been reported that the suicide rate of young people in Japan has a close correlation with the unemployment rate of recent years. 2 Despite a relative improvement in the economic situation, the employment situation for younger generations has deteriorated. Increased non-regular forms of employment such as temporary work, contract work or part-time jobs has led to many young people facing difficulty and distress. Thus, the charcoal burning suicide method may have attracted or appealed to younger individuals who failed to find employment.

Implications for suicide prevention strategies

A community-based approach to controlling such an apparent epidemic of charcoal burning is required, since means control cannot be successfully undertaken at an individual level. There is strong and consistent evidence from international studies that restricting access to specific methods can prevent suicides. Reference Cantor and Baume13,Reference Florentine and Crane14 Means restriction proves most effective when the method is common and highly lethal. Reference Yip, Caine, Yousuf, Chang, Wu and Chen15 When reduced access to a highly lethal method is possible, people who attempt suicide with less dangerous means have an increased chance of survival. Since the charcoal burning method became a popular suicide method among Japanese after the epidemic and is moderately lethal, Reference Yip, Caine, Yousuf, Chang, Wu and Chen15 restricting access to the charcoal burning method may be effective in reducing not only the charcoal burning specific suicide rate but also the overall suicide rate in Japan. Yip et al Reference Yip, Law, Fu, Law, Wong and Xu27 conducted an exploratory controlled trial to examine the efficacy of restricting access to charcoal to prevent charcoal burning-related suicides in Hong Kong. Their results indicated that the suicide rate from charcoal burning was reduced by a statistically significant margin in the intervention region but not in the control region. Therefore, although charcoal is generally perceived as a household leisure commodity used for home barbecue, and restricting it may be difficult, the efficacy of restricting access to charcoal should also be investigated in Japan.

Limitations

The study had several limitations that deserve discussion. First, not all suicides with an ICD-10 code X67 are charcoal burning suicides. However, since we estimated that about 80% of reportable deaths with an X67 code were charcoal burning suicides in 2007 in Japan, we believe that a large proportion of X67 suicides were indeed charcoal burning suicides during the charcoal burning suicide epidemic. Furthermore, since the charcoal burning method was not yet recognised as a popular suicide method in the pre-epidemic period, we believe that most X67 suicides in this period were not related to charcoal burning. We recommend the inclusion of suicide by charcoal burning in future revisions of the ICD to facilitate the monitoring of this potential global health problem. Second, one limitation of using official suicide rates is underreporting. Reference Hawton and van Heeringen1 Social, cultural and religious elements affect the reporting of suicide and are compounded by poor population estimates. The validity of reported suicide prevalence depends to a considerable degree on the method for determining the cause of death, the comprehensiveness of the death reporting system, and the procedures employed to estimate national rates based on crude cause of death data. Mortality data from Japan are considered to be a reliable estimate of cause of death and, thus, of suicide prevalence. Reference Hendin, Vijayuakumar, Bertolote, Wang, Phillips, Pirkis, Hendin, Phillips, Vijayuakumar, Pirkis, Wang and Yip28 In addition, we carried out sensitivity analyses, including cases where cause of death was classified as an undetermined intent, to assess any effects of possibly misclassified cases of suicide. The results of the sensitivity analyses were almost identical with these results. Consequently, we believe that, in this study, misclassification of mortality data would have a minimal effect on the results. Finally, we did not adjust for other variables that may influence suicide rates such as economic recession, unemployment, levels of divorce and changes in alcohol consumption, although it is unlikely that these factors would have an impact on charcoal burning suicides alone without affecting other suicide methods.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.