The ‘Landscapes of (Re)Conquest’ project (LoR) is a new programme of research investigating the character of medieval frontiers in the Western Mediterranean. Societies here were characterised by multiple and shifting frontiers during the Middle Ages, a formative period for modern Europe (Bartlett & MacKay Reference Bartlett and MacKay1992; Bartlett Reference Bartlett1994; Abulafia & Berend Reference Abulafia and Berend2002). These frontiers were created by periods of conflict between opposing societies defined, above all, by religious differences, with populations composed of fluctuating resident and migrant communities. Their material legacy is exemplified by spectacular monuments—the fortified centres of authority built to secure and control these frontiers. In Iberia, these dramatic castles are emblematic of the military conquests that have been merged into one lengthy, unrelenting reconquista; a term popularised in late nineteenth-century historiography with the aim of promoting a nationalist agenda of unification (Ríos Saloma Reference Ríos Saloma2013). Following this narrative, the process of unification was the direct result of a ‘reconquest’ of Christian Visigothic territories that had been lost to Arab and Berber Islamic forces. This was completed in Portugal in 1249 with the capture of Faro, and in Spain in 1492 with the annexation of Granada (Figure 1). Since 1978, many Iberian scholars have rejected the term reconquista in favour of regional ‘conquests’, but it still has international currency and remains in use within conservative sectors of Spanish society (Torró Reference Torró2000; García-Sanjuán Reference García-Sanjuán2018). Its main effect is to present an essentialist dichotomy between Christianity and Islam as driving the emergence of modern Iberian societies. In order to engage critically with public and scholarly perceptions of this problematic term, the use of ‘(re)conquest’ in the LoR project is deliberate.

Figure 1. Map showing the process of the Christian conquests of Iberia: A) Christian conquests of Islamic Taifa kingdoms and lands of Almoravid Emirate, AD 1080–1130; B) Christian conquests of lands of Almoravid Emirate and Almohad Caliphate, AD 1130–1210; C) Christian conquests of lands of Almohad Caliphate, AD 1210–1250; D) Christian conquests of Nasrid Emirate, AD 1480–1492 (figure by Aleks Pluskowski).

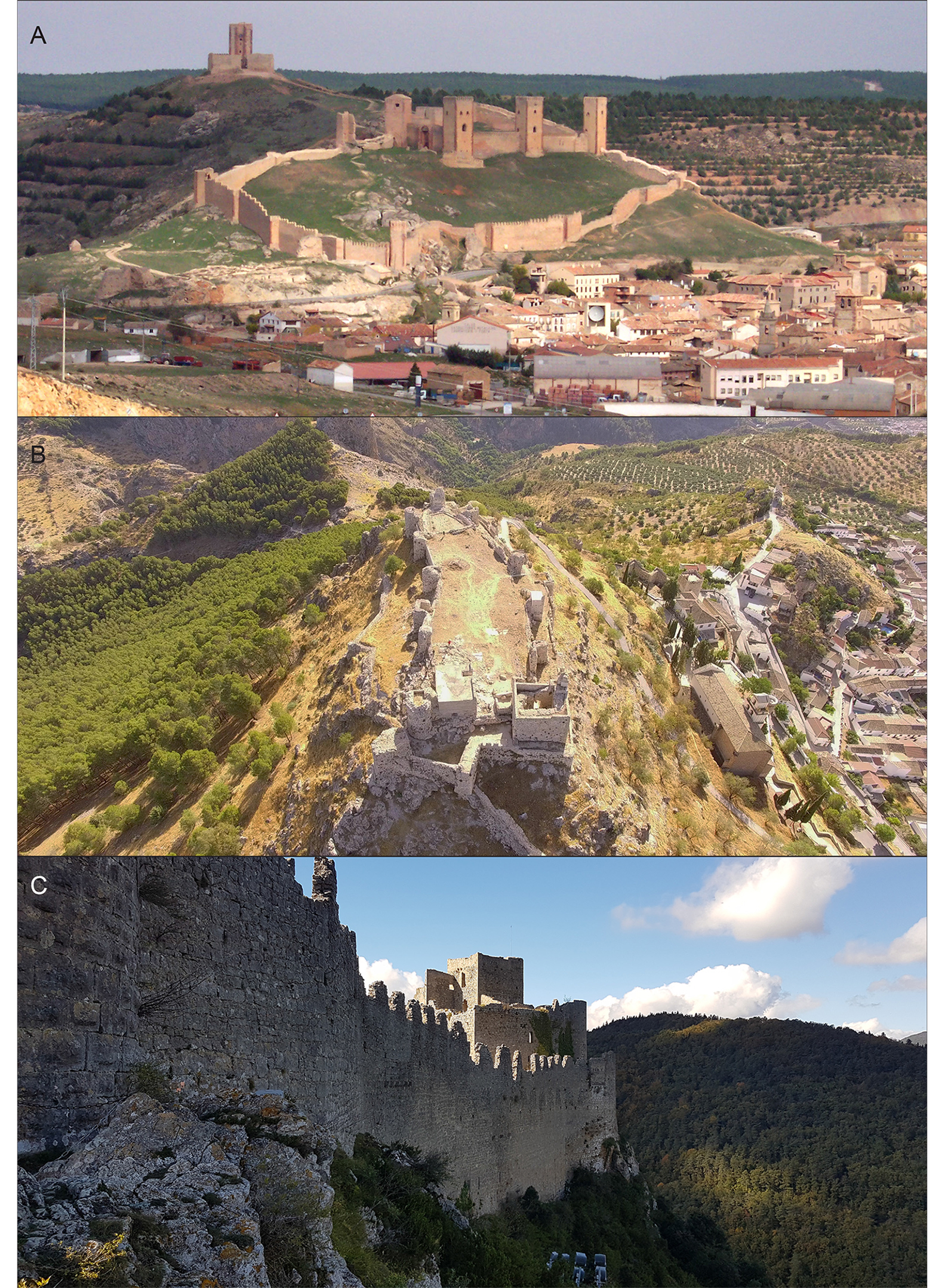

The geopolitical situation in the Western Mediterranean was far more complex than suggested by the previous narrative, and frontiers not only existed between nominally opposed Christian and Muslim states, but between those sharing the same world-views. Within Iberia, these were created between rival Islamic and Christian territories. To the north, the Pyrenees, which had formed a frontier between Carolingian and Islamic polities in the eighth century, the so-called ‘Spanish March’, saw the development of distinct Occitan lordships that were annexed by the Kingdom of France after a brutal crusade in the early decades of the thirteenth century. In 1258, the mountains became a new frontier between the kingdoms of France and Aragon (Sahlins Reference Sahlins1989). From an archaeological perspective, the imposition of French authority has been linked to a programme of rebuilding and expanding frontier castles, while the impact on communities has been dominated by studies of the suppression of Occitan heresy (e.g. Moore Reference Moore2012). In both Spain and the eastern French Pyrenees, these castles are major tourist attractions, often presented as centrepieces within enduring narratives of violent struggles for cultural hegemony (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The castles that functioned as centres and symbols of fronter authority: A) Molina de Aragón (Guadalajara) (https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Real_Se&per;C3&per;B1or&per;C3&per;ADo_de_Molina&hash;/media/Archivo:Molina_de_Aragon2.jpg); B) Moclín (Granada); C) Puilaurens (Occitanie) (B–C by Aleks Pluskowski).

A crucially important aspect of these sites remains largely neglected, however—their cultural landscape. In recent decades, landscape archaeology has reshaped our understanding of medieval communities, stressing the connection between places and their associated territories. This perspective has had limited impact on the European heritage sector. At the same time, the UNESCO Geoparks programme has sought to “explore, develop and celebrate the links between that geological heritage and all other aspects of the area's natural, cultural and intangible heritages” (UNESCO 2017). Our approach is inspired by this statement and the principal pilot for the LoR project was developed at the castle of Molina de Aragón (García-Contreras Ruiz et al. Reference García-Contreras Ruiz, Banerjea, Brown and Pluskowski2016), whose historical territory is partly encompassed by the Molina-Alto Tajo UNESCO Geopark (Figure 3). The landscapes around Molina, including the Geopark, can be characterised as a frontier between Christian and Muslim societies, and between opposing Christian societies, for a period of several centuries. In the context of frontiers created in a climate of religious tension, the cultural landscape provides a fundamental lens for understanding the impact of a new regime and social norms on its resident population. The aim of our project is therefore to reconnect key regional medieval monuments with their cultural landscapes, and to explore the nature of multiculturalism resulting from the interaction of migrant and resident communities in different frontier regions.

Figure 3. The historical territories of Molina de Aragón, showing the location of the UNESCO Geopark in green and the outlines of the modern provinces in the background: A) the distribution of Berber tribes during the Emiral period, AD 756–929; B) the Christian-Umayyad frontier (AD 929–1031); C) the frontiers between Taifa kingdoms and Castile after the fall of the Umayyad Caliphate; D) the Christian-Almoravid frontier until AD 1125; E) the Christian lordships are formed, c. AD 1125–1177; F) late medieval boundaries between the Christian polities of Castile and Aragon (figure by Guillermo García-Contreras).

While significant advances have been made in understanding frontiers, the LoR project provides a new approach, connecting site-specific archaeology with landscapes and heritage perspectives. The LoR project is a comparative investigation of three different frontier regions in Spain and Pyrenean France, as well as the province of Granada, involving collaborations with existing projects (Figure 4). Within each region, we will focus on discrete macro-regions corresponding to historically defined frontier lordships. Frontiers are regions with fixed temporality, and by adopting a long-term diachronic perspective we will contextualise the impact of multiple periods of conquest. The key questions we will ask are: how did conquering authorities deal with the creation of multicultural societies in these frontiers, how did they relate to central authorities and how did conquered communities respond to the imposition of new political and social norms?

Figure 4. The case-study regions in the ‘Landscapes of (Re)Conquest’ project, showing the three primary regions and the secondary study region of Granada (figure by Aleks Pluskowski).

Drawing on a range of archaeological, environmental and historical data, the LoR project will investigate changes in settlements, religious, commercial and political centres alongside environmental changes, assessing whether territorial reorganisation and the influx of migrants resulted in intensified resource exploitation, or to what extent earlier trends continued. Although changes in the character and intensity of environmental exploitation at the frontier are valuable indicators of the effective reach of the conquering authority and the economic demands of the polity's heartlands, this dimension is the least well-understood aspect of frontier societies in the Western Mediterranean. Important studies of Iberian landscapes have certainly been produced (e.g. Glick Reference Glick1996; Torró Reference Torró2000; Clemente Ramos Reference Clemente Ramos2001; Kirchner Reference Kirchner2010; Torró & Guinot Reference Torró and Guinot2012; Malpica Reference Malpica2014), but environmental and conventional archaeology remain segregated from each other, more broadly from historical research, and from how these sites are presented to the public. We will integrate animal and plant remains, alongside palynological, geoarchaeological and biomolecular data, as well as the better-known historical sources, to map changes in natural resource exploitation and their connections with social and ideological transformations associated with regime changes in our selected case-study regions (Figure 5). One of the most important indicators of these changes will be long-term changes in diet based on multi-proxy data. Food culture in frontier societies connected the dietary choices of individual households with nearby rural provisioning and longer-distance trade networks (e.g. García García Reference Garcia García2019).

Figure 5. Excavations of a medieval irrigation channel in the town of Molina de Aragón (figure by Aleks Pluskowski).

We will also compare the permeability of the range of frontiers encompassed by the study, and to what extent people, animals, commodities and ideas moved across them. Finally, we will bring all this information together to assess levels of cultural resilience in frontier societies—the ability of conquered communities to adapt to the imposition of a new regime. Environmental exploitation is an increasingly used index of this resilience. From this, the LoR project will develop visual and digital resources to enable public beneficiaries to engage with the cultural landscapes associated with the iconic monuments of frontier authorities.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council for funding this research project (grant number AH/R013861/1), as well as our partners: UNESCO Geopark of Molina de Aragón—Alto Tajo, Alex Brown (Wessex Archaeology), Quentin Borderie (Université de Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne), Acter Archéologie, Université de Perpignan—UPVD, and the Museum of the Order of St John, London. Further details of the project are available at: https://research.reading.ac.uk/re-conquest/