I

Between June 1959 and March 1964, the democratic governments of Brazilian presidents Juscelino Kubitschek (January 1956 – January 1961), Janio Quadros (January–August 1961), Ranieri Mazzilli (August–September 1961) and João ‘Jango’ Goulart (September 1961 – April 1964) received no support from the World Bank (WB), which refused to fund even a single new project during this period. The Bank insisted that this was due to the country's inability to keep inflation at bay, devise credible projects and stabilise the exchange rate. During this same period, and, more specifically, between July 1958 and January 1965, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the WB's twin institution, granted financial assistance to Brazil only twice: a controversial and highly conditional Stand-By Arrangement (SBA) signed in May 1961; and a non-conditional and automatically approved Compensatory Financial Facility (CFF), granted in May 1963 to compensate Brazil for the decrease in coffee prices on the international market.

This attitude towards Brazil changed significantly following the military coup in March 1964. The coup, which deposed the democratic government of the leftist President Goulart, established a right-wing military dictatorship that remained in power until 1985. Soon after the coup, high-ranking officials of the IMF and the WB began visiting the country regularly and established a collaborative relationship with Brazil's economic team. Money flowed into the country and by 1970 Brazil had become the largest receiver of WB funds and a chronic borrower from the IMF, signing two SBAs in 1965, and one per year between 1966 and 1972.

Although the IMF and the WB are, by their own rules, committed to ‘political neutrality’ the above description of events compels the following questions: To what extent was this change in lending to Brazil on the part of the IMF and especially the WB a result of the shift from democracy to military rule and/or from a leftist to a right-wing regime? Were the IMF and the WB ‘politically neutral’ when approving or rejecting Brazil's loan requests?

Drawing on a large corpus of historical evidence from the archives of the WB and the IMF (Washington, DC), disclosed at the authors’ request, this article seeks to examine the changing relationship between the Bretton Woods institutions and Brazil from 1961, the beginning of Goulart's presidency, until the end of the Castello Branco dictatorship in 1967. In doing so, it positions the military coup as a privileged vantage point from which to assess, on the one hand, whether the WB and the IMF preferred to collaborate with right-wing military rulers over democratic presidents, and, on the other hand, the extent to which Brazil's military regime was more eager than democratic administrations to work with both institutions. Our main argument is that the difference in the IMF's and especially the WB's relations with the military regime reflected, more than anything else, the existence of an ideological affinity between the parties with regards to the ‘right’ economic policy. Notwithstanding their alleged ‘political neutrality’, it seems that the economic policies and measures required by the Fund and Bank as crucial conditions to lending could have been carried out more fully by a right-wing authoritarian regime.

Since their foundation at the Bretton Woods Conference of 1944, the IMF and the WB have been expected to avoid political considerations in their dealings with member states. Article IV Section 10 of the WB Articles of Agreement states: ‘The Bank and its officers shall not interfere in the political affairs of any member; nor shall they be influenced in their decisions by the political character of the member or members concerned. Only economic considerations shall be relevant to their decisions, and these considerations shall be weighed impartially.’ Likewise, the IMF established three principles that were intended to direct its actions: universality and equality of treatment, which imply that the IMF should not discriminate among countries, and political neutrality, which refers to the IMF's self-imposed non-discriminatory practices between the different countries and regarding the various regimes within each member state (Guitián Reference Guitián1992, pp. 18–19).

However, the historical evidence analysed here indicates that both the IMF and the WB used this ‘political neutrality’, more than once, as a cover that enabled them to present as technical and unbiased the fact that they behaved differently in their dealings with different regimes. Between 1959 and 1964, rather than ignoring warning signs regarding Brazil's economy, as they were later to do under Castello Branco's regime, both the IMF and the WB used every minor or major ‘neutral’ economic problem as a pretext to refuse lending to the country. Furthermore, even if the two institutions were indeed ‘neutral’ in the sense that they had no a priori preference for any particular type of regime, one cannot deny that the implementation of the belt-tightening measures they requested in order to unlock their credit were more suited to and easily implemented by a repressive military regime than they were by a left-wing democratic administration whose main base of support (the workers) were the most affected by these same measures.

The IMF and the WB were not alone in providing financial assistance to the dictatorship. Under the shadow of the Cold War, the United States viewed the new regime as a more sympathetic interlocutor than the populist administrations of Vargas and Goulart or of Kubitschek, the main promotor of the Operation Panamerica (Amicci Reference Amicci2012; Sewell Reference Sewell2016, pp. 105–10). Between 1960 and 1966, Brazil received about US$2.5 billion in foreign aid.Footnote 1 In 1965 alone, it received around US$650 million (3 per cent of Brazil's 1964 GDP) from the Inter-American Development Bank, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Export–Import Bank (Eximbank) (Ribeiro Reference Ribeiro2006).

The analysis of Brazil's relations with the IMF and WB contributes to our understanding of several fields that have heretofore been surprisingly understudied. To begin with, despite the geopolitical and economic importance of Brazil in Latin America, no historical study has systematically analysed the international economic relations of the military regime or its ties with the international financial institutions (IFIs). The few studies that focus on Castello Branco's foreign relations tend to overlook foreign finance (Simoes Reference Simoes2010). Recently, scholarship has begun to address the complex interactions between commercial banks, IFIs and authoritarian regimes in Latin America. Carlo Edoardo Altamura, Raul García-Heras and Claudia Kedar have all examined different facets of the financial relations of authoritarian regimes in Latin America. Kedar has carried out extensive analyses of the relationship between the WB and the Argentine dictatorship of the 1970s (Kedar Reference Kedar2019a, Reference Kedar2019b) and between the WB, the IMF and Pinochet's Chile (Kedar Reference Kedar2017, Reference Kedar2018). García-Heras has concentrated on the international financial relations of the Argentine military junta (Garcia-Heras Reference Garcia-Heras2018a, Reference Garcia-Heras2018b), while Altamura has focused on European commercial banks and their activities in Latin America (Altamura Reference Altamura2020; Altamura and Flores Reference Altamura and Flores Zendejas2020). With regards to Brazil, however, studies are few, especially ones that focus on the post-1964 period. This is despite the fact that the dictatorship's dependency on foreign lending and the importance of economic growth for the legitimation of the regime looms large in academic publications (Frieden Reference Frieden1987; Bethell and Castro Reference Bethell, Castro and Bethell2008). In his seminal work on the economics of Castello Branco's presidency, Thomas Skidmore (Reference Skidmore1978 and Reference Skidmore1988) stressed that his years in power were crucial for the establishment of the so-called ‘Brazilian model’ – stabilisation through relatively orthodox monetary and fiscal policies, compression of real wages, maximum access for foreign investors, and resort to a modified form of indexation to neutralise factor price distortions caused by inflation. Yet still, a definitive examination of the issue has yet to be carried out.

Also beginning to emerge is scholarship on Brazil's contemporary economic history. Felipe Loureiro, for example, has published extensively on the Quadros and Goulart periods (Loureiro Reference Loureiro2010, Reference Loureiro2017). Part of his publications focus on the independent foreign policy that both presidents sought to follow, in particular vis-à-vis Washington, from the launching of the Alliance for Progress in 1961, and onwards (Loureiro Reference Loureiro2014). Loureiro shows that until mid 1962, the US adopted a somewhat moderate line towards Goulart, including loans within the framework of the Alliance for Progress. However, Goulart's increasingly defiant stance towards Washington ultimately led to the freeze of financial aid from the US government, the IMF and the WB.

Another significant issue that still remains understudied is the so-called stance of ‘neutrality’ assumed by the IMF and the WB. Relevant scholarship tends to question the actual capacity of either institution to act neutrally (Swedberg Reference Swedberg1986; Thacker Reference Thacker1999; Barro and Lee Reference Barro and Lee2002). Research tends to emphasise the link between US policies and the IMF's and Bank's decisions – a link that leads to the somewhat inevitable politicisation of their lending. Due to the adoption of a weighted voting system, the United States, the member state with the highest quota and the strongest voting power in both institutions, has always been the only member state with a de facto veto power on the Fund's and Bank's Executive Boards. Sarah Babb (Reference Babb2009), for example, examines the tension between the US Treasury and US Congress over the issues of Washington's policies towards the WB. Catherine Gwin (Reference Gwin, Kapur, Lewis and Webb1997) maintains that the US government and US-based non-governmental actors sought to influence WB policy only when US strategic interests were threatened. While most publications conclude that the major donors (United States, Britain, France, Japan and Germany) do have an impact on who received IMF and WB aid, and how much they received (Frey & Schneider Reference Frey and Schneider1986; Peet Reference Peet2003; Andersen, Hansen & Markussen Reference Andersen, Hansen and Markussen2006; Fleck & Kilby Reference Fleck and Kilby2006; Woods Reference Woods2006), others assert that these institutions are more sensitive to the economic needs of recipient states than to the strategic interests of donors (Burnside & Dollar Reference Burnside and Dollar2000). Other scholars emphasise the autonomy of the two institutions, suggesting that they were able to advance their own policies (Staples Reference Staples2002; Helleiner Reference Helleiner2014). Recently, scholars have begun to examine the IMF's and WB's ‘neutrality’ from the perspective of the member states. It has been suggested that when national policy paradigms fit with the policy paradigms of the IMF and WB, national actors tend to perceive both institutions as more impartial than politically biased (Heinzel et al. Reference Heinzel, Richter, Busch, Feil, Herold and Liese2020).

By closely examining the attitude of the IMF and WB towards the governments of Brazil before and after the coup of 1964, this article seeks to fill part of this glaring historiographical vacuum. With regards to the WB, projects submitted by Brazil before the coup were systematically rejected on economic grounds, as the economic policies of the democratic governments were deemed ineffective in controlling inflation, labour demands and fiscal deficits. Once the military government came to power, the WB actively supported the new economic plan (Plano de Ação Econômico do Governo, PAEG) of planning minister Roberto Campos and finance minister Otávio Gouveia de Bulhões. The IMF, by contrast, was more flexible than the Bank and found ways to remain active in Brazil regardless of the nature of the regime in power. This does not mean, however, that it treated all the Brazilian regimes equally.

The article is divided into six sections. As IMF loans tend to be a precondition for WB lending, Sections II and III focus on Brazil's relations with the IMF before and after the coup. Sections IV and V reconstruct Brazil's relations with the Bank in the same period, and Section VI provides concluding thoughts and observations.

II

Brazil signed its first SBA in July 1958, during the presidency of Kubitschek. The second SBA, worth US$160 million, was signed in May 1961, by President Quadros (Amicci Reference Amicci2012; Loureiro Reference Loureiro2013, Reference Loureiro2014).Footnote 2 Two months later, due to Brazil's non-compliance with the terms of the agreement, the IMF unilaterally interrupted the SBA. This interruption initiated a lending break that lasted throughout the whole presidency of Goulart who, from the start, was perceived as the heir of Vargas's populism and therefore remained under the suspicious scrutiny of conservatives within military and civilian circles. To this should be added the traumatic manner in which Goulart assumed the presidency following Quadros's sudden resignation, as well as the diminished power that was left in his hands by the Congress,Footnote 3 which augmented doubts already festering in the halls of the IMF and the WB regarding the administration's ability to implement a coherent economic plan and comply with its international commitments (Ramírez Reference Ramírez2012, p. 257).Footnote 4 This break, in which a small CFF granted in May 1963 was the only exemption, ended in January 1965, when the IMF approved an SBA to Castello Branco's dictatorship. In fact, between 1965 and 1972 the IMF granted Brazil's dictatorship eight consecutive SBAs, and an additional three between 1983 and 1985. Not only did the IMF intensify lending to Brazil after the coup, but, following a request from Otávio Bulhões (Brazil's governor to the IMF and WB), Rio de Janeiro hosted the 1967 annual meeting of the board of governors of the IMF and the WB, thus indicating a more than symbolic seal of approval of the dictatorship on the part of the Bretton Woods institutions.

The IMF and WB were not alone in refusing financial support to Goulart's administration, mainly because the US government and private lobbies opposed what they perceived as the administration's ties with communists and radical labour unions, as well as Goulart's independent foreign policy (Weis Reference Weis1993, ch. 6; Rabe Reference Rabe1999, pp. 64–7, 196–7). This was by no means unusual. US-based institutions often used their financial assistance as leverage to persuade their borrowers to adopt ‘correct’ policies (Kofas Reference Kofas2002, ch. 7; Kedar Reference Kedar2013, chs. 3 and 5). Furthermore, although the IMF did not grant any SBA to Goulart, his team had to deal with the commitments assumed by previous administrations. For instance, in March 1962, Walter Moreira Salles, Goulart's minister of finance, sent a letter to Per Jacobsson, the IMF's managing director (1956–63), requesting a postponement of the repurchase equivalent of US$20 million scheduled for 31 March to September 1962.Footnote 5 Whereas the IMF staff felt that Brazil's policy would not curb inflation or solve the budget deficit, it recommended that the EB (executive board) approve the request.Footnote 6 It believed that Brazilian technocrats (unlike Brazil's government) were ‘fully competent to evolve an effective program’ and were ‘fully aware of the need to bring the Brazilian inflation under control and to strengthen the balance of payments’.Footnote 7 In August 1962, finding itself still unable to meet IMF financial demands, Brazil formally requested the postponement of its obligations to the Fund.Footnote 8

On 12 December 1962, Jorge del Canto (director of the IMF's Western Hemisphere Department, WHD) informed Frank Southard Jr (IMF deputy managing director) about an informal meeting he had had with a ‘Brazilian friend’ of the Fund, Proença de Gouvea, head of the Exchange Department of the Banco do Brasil. Del Canto intended to visit Rio to meet officers of the Banco do Brasil and other ‘[IMF] friends at the Ministry of Finance’ for ‘an informal appraisal of the situation’.Footnote 9 He reported that according to Proença, the Brazilian government was working on a stabilisation plan and that it would request a Fund mission to discuss it. In order to make this plan politically acceptable, Proença argued, it would have to be presented together with a development plan.Footnote 10 Proença explained that although in mid 1962 Brazil's balance of payments was ‘very bad’, it had since improved. He stressed that most difficulties were attributed to heavy repayments against foreign indebtedness.Footnote 11 Despite Proença's optimism, the WHD estimated that the deficit, which stood at US$122 million, would worsen mainly due to a 50 per cent increase in government salaries and to the application of new subsidies on rice and beans – which the IMF disapproved. In any case, under the coordination of minister of planning Celso Furtado, Goulart launched in December 1962 the Triennial Plan for Economic and Social Development or Plano Trienal (1963–5) – a stabilisation plan that sought to implement many of the IMF's recommendations. This plan recognised two major problems in Brazil's economy. The first was the deficit of the federal government. The second was the country's chronic inability to import goods, which required permanent adjustments in the internal offer and currency devaluations (Bastian Reference Bastian2013). The ultimate goal of the plan was to stabilise the economy at an inflation rate of 10 per cent by 1965 without prejudicing economic growth. In this sense, the plan eschewed a purely orthodox shock therapy in favour of a gradualist or ‘eclectic’ approach (Fonseca Reference Fonseca2004).

Despite, or probably because of, the eclectic nature of the plan, the Plano Trienal was harshly criticised on both the right and the left. Trade unions saw it as caving in to Washington and the more conservative sectors of Brazilian society. Industrialists, who had initially supported the plan, grew increasingly dissatisfied with the lack of controls on wages (Almeida Reference Almeida2010). The plan was abandoned in July 1963 (Loureiro Reference Loureiro2010, pp. 109–43).

In February 1963, Brazil's government was at risk of defaulting on its foreign debt payments. In mid March 1963, minister of finance San Tiago Dantas travelled to Washington to negotiate a US aid package in what scholars recognised as Brazil's ‘last chance to save democracy’ (Loureiro Reference Loureiro2013). Dantas requested an ambitious package totalling US$839.7 million. The negotiations were particularly difficult due to the US government's fear of communist infiltration in Goulart's administration (Loureiro Reference Loureiro2013). Yet obtaining external credits was an essential part of the Plano Trienal, which estimated the financial needs for the 1963–5 period at US$1.5 billion. Without external support, any effort to stabilise prices was doomed to fail as the only two options open to Goulart's government were either to devalue the exchange rate or, alternatively, to contract domestic demand (Bastian Reference Bastian2013, p. 159).

In order to avoid a default, the US provided immediate assistance totalling US$84 million and a further much larger loan of US$314.5 million pending agreement with the IMF, the WB, Western European countries and Japan. While in Washington, Dantas asked to meet Per Jacobsson and Southard to discuss a postponement of the US$26.5 million repurchases that were due in March 1963.Footnote 12 While referring to a potential SBA, Del Canto confirmed that Brazil was eligible for an SBA of US$117.6 million. He added that there was a shortfall in coffee exports in 1962 that was attributable to circumstances beyond Brazil's control, thereby making Brazil eligible for IMF assistance under the new compensatory financing policy (CFF) established in 1963. Del Canto considered that a new SBA could be justified ‘if a satisfactory plan [was] worked out between the Fund and Brazil and effective implementation of such a plan [was] insured by Brazil …’.Footnote 13

On 21 March 1963, Per Jacobsson wrote to Dantas that the Fund was impressed by Brazil's determination to design a stabilisation plan.Footnote 14 He stressed, however, that Brazil still had to reduce the operating deficits of the railways, merchant marine and post office, and that subsidies formerly provided could not be reintroduced. He added that emergency measures had to be taken, including reductions in the subsidies to state agencies, increases in tax revenues, the imposition of a new exchange tax and the formulation of a new coffee policy. The Fund recommended establishing a realistic and stable exchange rate and encouraging larger inflows of private capital in order to avoid increases in Brazil's short and intermediate-term external debt.Footnote 15 Undoubtedly, the Fund's requests, especially the elimination of subsidies and a contractionary wage policy that implied dropping real wages, posed a harsh political challenge to Goulart as they would negatively affect the social groups to which he was most committed. Under these circumstances, Bicalho informed Del Canto that he would accept a Fund mission to finalise elaborating the stabilisation programme but only after mid April in order to give the authorities time to move the exchange rate to Cr 600 per US dollar and firm-up the wage increase to 40 per cent.Footnote 16 This postponement seems to imply that even when Goulart's administration was prepared to compromise with the IMF, neither Bicalho nor Del Canto wanted to have the IMF mission appear to be associated with the implementation of controversial austerity measures.

Del Canto's new mission stayed in Brazil between 8 and 29 May 1963, during which time labour demonstrations demanding land reform also demanded that Goulart cease talks with the IMF mission.Footnote 17 Although Del Canto doubted that Brazil would adopt a programme that could justify an SBA, he recommended continuing to maintain a dialogue with Brazilian authorities.Footnote 18 On 5 June 1963, the EB approved a CFF worth US$60 million to Brazil due to export shortfalls.Footnote 19 It was thus under Goulart's administration that Brazil became the first member state to receive a CFF (Boughton Reference Boughton2012, pp. 216–17). Significantly less controversial than an SBA, the CFF constituted a politically more acceptable way of maintaining IMF–Brazil cooperation, especially at times of ideological disagreement between the parties. The CFF, to be sure, constitutes a kind of emergency aid which not only provides the country part of the sums it needs to solve a temporary crisis, but also sends a green light to other creditors and international markets. It is worth noting that Salvador Allende (1970–3), the socialist president of Chile, was also granted three CFFs (Kedar Reference Kedar2015, pp. 717–47). In any case, the lack of new SBAs served as a pretext for the US administration to adopt a hard line towards Goulart's regime, including non-lending and, ultimately, supporting the coup (Loureiro Reference Loureiro2014, pp. 344–6).

In summary, although the IMF disagreed with Goulart's economic policy and had serious doubts about his ability to deal with the social and political tensions in Brazil, it strove to avoid an open dispute by following the same conciliatory line that it tended to adopt when dealing with other populist and left-wing leaders in the region, such as Salvador Allende and Juan Perón in the 1970s. Determined to help Brazil avoid a default on its foreign debt, including debts owed to the Fund, it granted Goulart's administration a non-conditional CFF, which by no means implied that the IMF favoured Goulart's regime. The CFF, in turn, allowed Goulart to access IMF funds without taking what he feared were unacceptable political risks. Thus, it seems that the pragmatism that characterised IMF–Brazil relations during Goulart's presidency was an expression of, and facilitated by, the IMF's ‘political neutrality’. On the one hand, the IMF did not provide significant financial support to a government that did not fully adopt its policy prescriptions, thereby securing the IMF's prestige as a neutral and responsible lender. On the other hand, based on ‘pure’ economic criteria, it granted Brazil a CFF that did not require any policy reform. Simply put, the IMF found a ‘neutral’ balance between its fundamental disagreements with Goulart's economic policy and its determination to help Brazil avoid a deeper economic crisis. Brazil, for its part, used the IMF's ‘neutrality’ to its own benefit as it allowed Goulart to have his cake and eat it too, namely, to ignore most of the IMF's policy advice but benefit from its non-conditional financial assistance.

III

From his first day in office, President Goulart aroused the suspicions of Brazil's right-wing and conservative elites. Under the shadow of the Cold War, his strong ties with organised labour and his defiant stand towards Washington convinced the US to support a coup to depose him. Soon after the coup, on 9 April 1964, the Supreme Revolutionary Command (SRC) composed of the commanders-in-chief of all military services, issued the First Institutional Act (AI-1) – the first of many steps aimed at purging the political system. The SRC immediately cancelled the mandates of 40 congressmen, fired 122 officers from the military, and suspended for ten years the political rights of 100 politicians and ‘subversive elements’ including union leaders and intellectuals (Stepan Reference Stepan1971, pp. 123–4). On 11 April Congress ratified the appointment of Castello Branco to serve as president for the remainder of Goulart's term. Four days later, he assumed the presidency, vested with emergency powers. Although he intended to permit limited political activities and transfer power to a civilian president in 1966, political setbacks in important states and pressure coming from hard-liners, including General Artur da Costa e Silva, led Castello Branco to adopt a more authoritarian approach. Thus, on 27 October 1965 he issued AI-2. This second act established indirect elections for the presidency; intervened with the composition of the supreme court; and abolished all traditional political parties, establishing in their stead a bipartisan system composed of the National Renewal Alliance (ARENA) and the Brazilian Democratic Movement (MDB). It also extended Castello Branco's term to 1967 (Skidmore Reference Skidmore1988, pp. 45–9). As Roberto Campos, Castello Branco's minister of planning, stated in September 1967, the postponement of the elections that were originally scheduled for 1966 also had economic motivations, since the stabilisation and development plans launched by the military regime were not expected to have visible effects before 1970. Moreover, as Campos argued, the military believed that no civilian leader would have the power, let alone the will to implement a stabilisation policy (Stepan Reference Stepan1971, pp. 217–18). The repressive character of Brazil's military regime became more evident under Costa e Silva. On 13 December 1968, he issued AI-5, which permitted the military to close Congress, enabled the president to rule by decree, allowed the military to suspend any citizen's political rights for 10 years and gave the military the power to dismiss public employees on all levels of government. AI-5 also suspended the right to habeas corpus, permitted trials before military tribunals and reinstated the death penalty. In the coming months, new decrees further curtailed democratic principles: all scheduled elections were cancelled and strict censorship was implemented over cultural mediums and the press (Guerchon Reference Guerchon1971, pp. 265–9; Skidmore Reference Skidmore1988, pp. 81–4).

In contrast with deposed president Goulart, Castello Branco adopted a pro-US stance. This included breaking diplomatic ties with Cuba in 1964, supporting the US invasion of the Dominican Republic in 1965, and publicly celebrating US economic and political achievements. The Lyndon Johnson administration recognised Brazil's military regime two days after the coup and that same day, Johnson promised to augment US financial assistance to Brazil (Simoes Reference Simoes2010, pp. 41–2). As ties with the US administration improved, IMF missions and loans to Brazil multiplied.

The first IMF mission to the military regime, led by David Finch and Herbert Zassenhaus (WHD), visited Rio from 5 to 20 May 1964.Footnote 20 They met, among others, Otávio Gouveia de Bulhões (minister of finance), Roberto de Oliveira Campos (minister of planning and coordination and the main architect of the Governmental Economic Plan of Action) and Luis Moraes Barros (president of the Central Bank). Although the new economic programme was still being worked out, Brazilian authorities explained that they sought to restore the pre-1962 rate of economic growth, curb inflation and overcome the chronic budgetary deficit. They intended to raise taxes and tariffs, eliminate subsidies and liberalise the 1962 law on the remittance abroad of earnings from foreign capital. One can imagine how satisfied the mission was to learn that the military regime intended to implement ‘correct’ policies. Although the mission's report was overly technical, a comment regarding the ‘widespread understanding that substantial changes have to take place’, in particular regarding ‘intolerable inflation rates’, led the staff to claim that, contrary to deposed President Goulart, ‘the new authorities, armed with extraordinary powers, [were] therefore faced with an opportunity to take decisive action’.Footnote 21

The foreign debt constituted one of Brazil's most urgent economic problems. Maturing debts totalled about US$3.5 billion but the annual exports hardly reached $1.3 billion.Footnote 22 Under these circumstances, meetings were held in Paris during March–July 1964, between Brazil's representatives and ten major creditor countries: Austria, Belgium, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Switzerland, the UK and the US. Representatives of the IMF, the WB and the OECD were also present. The parties agreed to refinance payments on credits due in 1964 and 1965.Footnote 23 In June, the US granted Brazil a US$50 million credit and Ambassador Gordon promised additional funds through the Alliance for Progress (Simoes Reference Simoes2010, p. 44).

In late July, John Bullitt, assistant secretary of the Treasury and US executive director to the WB, offered a lunch at the WB for representatives of the State Department, the WB and the IMF.Footnote 24 Discussions focused on Brazil's development plan. Del Canto expressed willingness to soon start lending to Brazil. The WB representatives, by contrast, stressed that they would resume working in Brazil only in October and that no financial assistance should be expected before March 1965. When Bullitt asked about a possible joint WB–IMF mission to Brazil, Del Canto responded that the IMF would prefer two parallel missions. Initially, the WB agreed with Del Canto.Footnote 25 The State Department representatives then asked about the timing of the IMF's negotiations for an SBA. Del Canto answered that Brazil would not be ready to negotiate before October and stated: ‘we all agree that the new group is well-intentioned; they are our friends and they deserve full sympathetic consideration’,Footnote 26 thus explicitly recommending adopting a sympathetic attitude towards the military authorities. Revealing a sense of competition vis-à-vis the WB he stressed: ‘in view of the large Bank mission [to Brazil] we need to reaffirm our expertise knowledge in our own field and thus hope to have the Bank rely on our work in the financial field’.Footnote 27

On 20 October 1964, Del Canto participated in the Inter-American Committee for the Alliance for Progress (CIAP) review of Brazil. He first praised Minister Campos, ‘a long-standing friend of the Fund’.Footnote 28 Then, he applauded the military regime because it was ‘more aware than many previous Brazilian governments of the urgency to combine a strong economic development policy with a determined attack on the problem of inflation’ and because it was ‘engaged in the execution of a comprehensive plan of economic and social action’. Del Canto also referred to the need to curb inflation and to improve the balance of payments. He added that the Fund was not yet ready to make decisions, but an IMF mission was already in Brazil.Footnote 29

Del Canto's optimism was short-lived. In late November 1964, while heading a mission to Brazil, he updated Schweitzer about his meetings with Bicalho, Campos and Bulhões.Footnote 30 He argued that he was careful not to give the Brazilians the impression that the IMF favoured granting an SBA under the existent economic situation. However, the Brazilians insisted that they needed an SBA because they were negotiating loans with the US government and needed ‘the [IMF's] green light’. Del Canto concluded that ‘unless [the IMF] reach a clear and enforceable agreement on exchange rate policy and a program to liquidate commercial arrears, it would be absolutely impossible for the management even to consider the idea of a stand-by’.Footnote 31 Following this update, Schweitzer wrote to Campos that if a satisfactory agreement with the mission was reached, Del Canto would assist him in drafting a letter of intent towards an SBA.Footnote 32 Del Canto, it appears, was not the only IMF official who was keen to resume lending to Brazil.

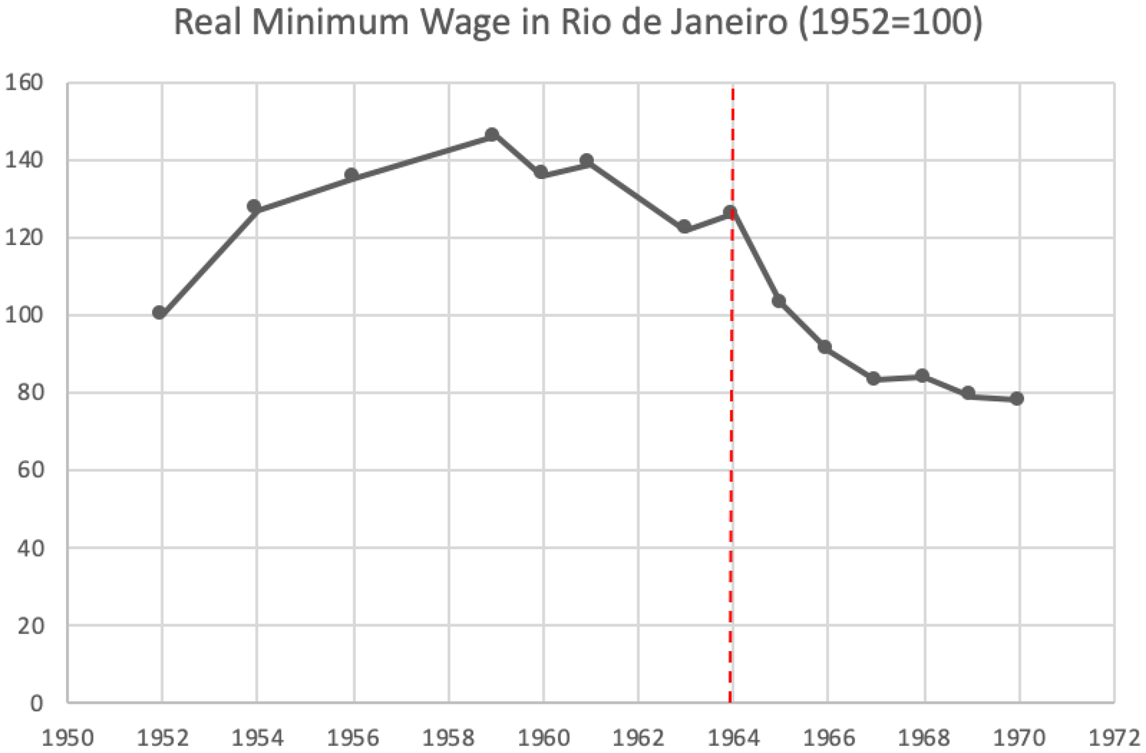

The first economic plan of the regime, the PAEG, assumed that inflation, which had reached around 90 per cent in 1964, was the main obstacle to development. The plan stressed the need to restore economic growth to the pre-1962 period; to fight the inflationary process in order to bring inflation under control by 1966; and to fight balance of payment deficits that were endangering the continuity of the development process by creating bottlenecks in import capacity (Lara Resende Reference Lara Resende1982). According to the Plan, and in line with the IMF's monetarist precepts, inflation was primarily caused by excess demand. Excess demand, in turn, derived from public sector deficits, excessive credit to the private sector and wage increases that were higher than the increase in productivity rates, i.e. cost inflation (Skidmore Reference Skidmore1978, p. 154; Bastian Reference Bastian2013, p. 146). Interestingly, the PAEG had more in common with the Plano Trienal than one would assume. Under an orthodox façade, the PAEG shared with the Plano Trienal a gradualist approach, seeking to lower inflation without prejudicing economic growth. Further, monetary growth was expected to reach 70, 30 and 15 per cent respectively in 1964, 1965 and 1966 (Lara Resende Reference Lara Resende1982, p. 76; Bastian Reference Bastian2013). Both plans targeted an inflation rate of 10 per cent by the last year of their plans. On the fiscal side, the PAEG expected the federal government to reduce all non-priority expenditures; and increase revenues via a reformed fiscal system and a new market for public debt with the creation of the Obrigação Reajustável do Tesouro Nacional (ORTN). On the monetary side, the PAEG sought to limit the public deficit and control credit to the private sector (Bastian Reference Bastian2013, p. 148). A significant difference between the two plans, however, was the emphasis placed by PAEG's policymakers on the control of wages in order to break the inflationary spiral (Fishlow Reference Fishlow1974; Lara Resende Reference Lara Resende1982), something Goulart was unable to do. As a result of the new wage and labour policies, the real minimum wage between February 1964 and March 1967 dramatically decreased (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Real minimum wage in Rio de Janeiro, 1952–70

Source: Lara Resende (Reference Lara Resende1982) p. 779, based on IBGE Anuário Estatístico do Brasil.

Together with the compression of wages (Lara Resende Reference Lara Resende1982, pp. 803–4), there was a visible change in the concentration of income: if in 1960 the income shares of the top 5 per cent of the population was 27.69 per cent, in 1970 it was 34.86 per cent. By contrast, the income shares of the bottom 50 per cent decreased from 17.71 per cent in 1960 to 14.91 per cent in 1970 (Lara Resende Reference Lara Resende1982, p. 804). The Gini coefficient increased from 0.49 to 0.56 between 1960 and 1970 (Fishlow Reference Fishlow1974, p. 33). A final but crucial difference between the Plano Trienal and the PAEG was the very unequal treatment that these two fairly similar plans received from international creditors (Ribeiro Reference Ribeiro2006). Thanks to ‘generous’ external support, Castello Branco's economic plan avoided the ‘external strangulation’ experienced by the earlier plan (Bastian Reference Bastian2013, p. 159), thereby alleviating the pressure on the balance of payments, which remained in equilibrium in 1964 (US$2 million deficit) and in surplus in 1965 (US$218 million) compared to a substantial deficit in 1962 (US$118 million in 1962) and 1963 (US$37 million) (Bastian Reference Bastian2013, p. 164).

On 5 December 1964, thus, Bulhões requested a US$125 million SBA, to be effective from 1 January 1965.Footnote 33 Two days later, Del Canto sent Bulhões a list of actions that his government would be required to institute before the SBA's request could be submitted to the EB vote. These actions included, among others, determining the percentages of the surcharges on import payments and on financial payments; the abolition of export restrictions; the introduction of exchange retentions on exports; and tariff increases. Del Canto requested that Campos should update Schweitzer directly once such decisions were taken and send weekly updates to the WHD.Footnote 34

It seems that these two uncommon requests reflected Del Canto's reservations about Brazil's capability to fully implement the economic plan that the SBA was aimed at supporting. A secret memorandum further reveals his doubts and concerns. Del Canto was apprehensive that the lack of a central bank in Brazil would impede the plan's implementation. This worry evaporated on 31 December 1964, a few days before the EB vote on the SBA request, when, partially due to IMF pressure, Brazil founded its Central Bank.Footnote 35

In any case, in December, the SBA proposal was submitted to the EB. The WHD recommendations stressed that the SBA was aimed at supporting Brazil's PAEG, which, among others, outlined agrarian and administrative reforms and the modernisation of the banking system.Footnote 36 The basic objectives for 1965 were to decelerate inflation and to reactivate economic growth in order to obtain a GDP annual rate of increase of about 6 per cent in 1965–6. Changes in the taxation system included making the personal tax more progressive, maintaining the corporation tax rate at 28 per cent, establishing a new petroleum tax and imposing limits to total budget expenditures.Footnote 37 The WHD concluded that if applied in full, the PAEG would lead to a drastic reduction of the inflation rate by late 1965. One should keep in mind that the plan was expected to generate price increases and, consequently, labour unrest. The IMF stressed that the government would have to be firm and resist pressure to augment wages in the public sector or allow credit expansion. Del Canto believed that Castello Branco's military regime could, and would, resist such pressures.Footnote 38 The EB approved the first SBA to Castello Branco's regime on 13 January 1965.Footnote 39 This paved the way for additional credit. In December 1964, the US Treasury signed a US$150 million programme loan for Brazil from the US-AID. Ultimately, US loans to Brazil in 1965 totalled over US$450 million.Footnote 40 In March 1965, 16 US commercial banks granted Brazil credit worth US$80 million,Footnote 41 while European bankers agreed to lend Brazil US$50 million.Footnote 42

In February 1965, a new IMF mission arrived in Brazil. It reported that Brazil was advancing positively with the SBA and had requested two technicians to advise the Central Bank's Exchange Department. The Brazilians stressed that they wanted technicians recommended by the Fund but not associated with it – a rather uncommon request that Del Canto nonetheless accepted.Footnote 43 It seems that the dictatorship and the IMF were equally interested in blurring the deep traces of the IMF's involvement in the turbulent domestic sphere.

Problems, however, were quick to arise. On 3 April, Del Canto reported that the Bank of Brazil was exceeding the ceilings stipulated in the SBA.Footnote 44 On 28 April, in order to avoid declaring that Brazil had violated these ceiling limitations and thereby increasing the risk that the agreement would be stopped, a minor modification of the SBA was approved.Footnote 45 This change, though minor, was significant. It clearly shows the IMF's tendency to downgrade the seriousness of economic problems so long as the regime in power was ready to follow its policy recommendations. Moreover, in June, Del Canto reported that the Brazilian government feared a recession.Footnote 46 In order to certify Brazil's eligibility for the next drawing, Del Canto began to organise a mission scheduled to arrive in Brazil around 12 July. However, the impression at the WHD was that Bicalho was hesitant to accept the IMF's presence in the country ‘in view of the heated controversy around the Plan that [was] going on in Brazil’.Footnote 47 Yet a large IMF mission headed by Del Canto visited Brazil from 2 November to 16 December and opened SBA negotiations.Footnote 48 While in Rio, it was in touch with a WB mission and with Ambassador Gordon and a US team that was negotiating a new aid programme.Footnote 49 Negotiations with the IMF, WB and US government continued to take place also after October 1965, when Castello Branco issued the AI-2.

On 16 December 1965, Bulhões requested a second SBA for US$125 million.Footnote 50 In its recommendations, and despite the problems already mentioned, the WHD stressed that Brazil's economy had made substantial progress over the course of 1965.Footnote 51 On 2 February 1966, the EB approved Brazil's request. While detailing the measures adopted by the Brazilian government, Del Canto mentioned incentives in the building industries; a 30 per cent increase in railroad rates; a reduction in the interest rate on rural credit; a programme of new fiscal incentives; decontrolling of meat prices; adjustment of gasoline and petroleum prices to the new exchange rate; new limits to wage increases; and more.Footnote 52 Weeks later, Brazil sent a formal request for technical assistance, which the IMF approved.Footnote 53 In the meantime, US private investments in Brazil increased, reaching nearly US$1 billion.Footnote 54

The implementation of the second SBA was not without its challenges. Two IMF missions, in mid 1966, focused on the coffee policy and decreasing earnings; bank credit, which continued to expand at a rate of 2.5–3 per cent per month; and the balance of payments.Footnote 55 In October, Del Canto arrived in Rio to negotiate a third SBA. This time, the Brazilians wanted a US$30 million SBA, as ‘they were more interested in the arrangement for the internal discipline it would provide, rather than for the financial support it would offer’. This was by no means extraordinary. More than once, countries signed SBAs not because they intended to draw the money but because they needed the IMF's seal of approval. In fact, the implementation of the US-AID assistance programme in the country depended on Brazil's entering into a new SBA.Footnote 56

On 22 December 1966, Bulhões requested a US$30 million SBA, which the EB approved on 13 February 1967. As in the previous EB meetings, no political questions about Brazil's dictatorial regime were asked.Footnote 57 On 27 January 1967, Del Canto held a 15-minute meeting with the man who would go on to become the next president of Brazil, Artur da Costa e Silva. The latter referred to the forthcoming annual meeting in Rio and said that he hoped to address the opening session to which Del Canto enthusiastically responded that the IMF ‘would not consider the meeting fully successful unless he were to address [the participants]’. Costa e Silva then said that he was looking forward to a discussion at the Rio meeting about ‘the important subject of the international monetary reform’ to which Del Canto responded affirmatively.Footnote 58

IV

The relationship between Brazil and the WB, as Burke J. Knapp (WB vice president) put it, was ‘more unhappy and strained than [with] any other member’ (Kapur et al. Reference Kapur, Lewis and Webb1997, p. 105).

Brazil received its first WB loan in 1949. With a total of 11 loans in the 1950s, Brazil became one of the WB's main clients. Yet WB lending was interrupted after the suicide of President Getulio Vargas in 1954 (until 1958) and then again from 1959 to 1965 during the presidencies of Kubitschek, Quadros and Goulart. This is even more remarkable given that at the time Brazil was among the fastest growing economies in the western hemisphere.

The first WB loan to Brazil was granted 27 January 1949, to Brazilian Traction, a foreign-owned utility company operating in southeast Brazil (US$75 million), and was not warmly received by the government who would have preferred the loan to be in favour of a state-owned company or project. The second loan was for a US$15 million project to develop the potential of the San Francisco River and provide hydroelectric power to the northeast.

The WB–Brazil relationship continued to strengthen throughout the early 1950s. By 1951, a joint Brazilian–US Commission for Economic Development was established. Projects approved by the commission were presented to the WB and the Eximbank for financing. The first US head of the commission (co-directed with a Brazilian) was Francis Adams Truslow, former head of the New York Curb Exchange who had previously served as head of the WB mission to Cuba. One of Truslow's first decisions was to agree to set up a Brazilian Development Bank to finance the local currency costs of the projects that the commission was expected to present to the WB and Eximbank. Unfortunately, Truslow died while en route to Rio in July 1951. The US sent Mervyn Bowen to act as US head of commission until Burke Knapp obtained leave of absence from the WB and was able to take Bowen's place. Bowen filled the position for one year.

The projects financed by the Bank in 1952–3 were essentially those presented by Brazil after having been approved by the commission. By early 1954, the Bank made 10 loans totalling US$194 million principally for power production (seven loans totalling US$166 million) and railways (two loans totalling US$25 million). The relationship soured as coffee prices began to fall at the end of 1954 and Brazil's financial position deteriorated. Between 1954 and 1959, the price of ‘Santos 4 Coffee’ on Wall Street decreased from 78.9 cents/pound to 36.9 cents/pound.Footnote 59 After 1954, the Bank ceased lending operations in Brazil until fiscal rectitude was assured. In the period 1954–6 Brazil received several loans from the United States, including a commitment of US$150 million from Eximbank for the railways. Things improved further when technocrats such as Lucas Lopes and Roberto Campos became part of Kubitschek's economic team and led the efforts to elaborate the Plano de Metas and, subsequently, the Plano de Estabilização Monetária (PEM) (Lopes Reference Lopes1991).Footnote 60 The Furnas Hydroelectric Project was financed in 1958 by the Bank with a US$73 million loan for the first stage of what was at the time the largest hydroelectric project ever undertaken in Latin America. After Lucas Lopes suffered a stroke and the PEM was abandoned, the WB once again ceased its lending operations in Brazil. Apart from ideological discrepancies, the relationship was made especially difficult by Brazilian unwillingness to give much-needed rate adjustments in the energy sector, in which the Bank was deeply financially involved, thus forcing ‘the private utilities into a hopeless financial position’.Footnote 61

In February 1962, Campos, now as ambassador of Brazil in Washington, DC, headed a delegation composed of the president and two directors of the Centrais Electricas de Urubupungá (a company created by the State of São Paulo in 1951) to the WB. The delegation met with Knapp and Barend A. de Vries (at the time economic adviser to the WB-WHD) to discuss the Bank's interest in supporting the first stage of the construction of a hydroelectric project involving eight units of 166MW each for an estimated amount of US$150 million. Knapp responded that although ‘the Bank was in a position to do this type of financing’, it ‘could not discuss financing of the Urubupungá project at the present time, having regard to Brazil's unsatisfactory financial position, both internal and external’. Knapp concluded with a damning remark: ‘Until confidence has been restored in Brazil, we have to delay consideration of any project.’Footnote 62

The meeting preceded, by two months, the meeting between newly elected Brazilian president Goulart and WB president Eugene Black (1949–63). In a memorandum, Orvis Schmidt (director, Department of Operations – Western Hemisphere) briefed Black on potential topics of discussion. With regards to the conditions to resume lending, Schmidt remarked that ‘the Bank could not lend until it sees a prospect of Brazil's carrying out a program which would effectively strengthen its international position and give us grounds for a judgement that the total service on Brazil's external debt … would be within Brazil's ability to pay on schedule’.Footnote 63 With regard to International Development Association (IDA, part of the World Bank Group) lending, Schmidt suggested Black take a tough stance on that topic as well, saying that ‘until Brazil takes measures to stabilise its domestic financial position (balance the budget) and stop the drain on its resources … the use of IDA resources would not be justified’. Not unexpectedly, given these premises, Goulart's mission was a failure.

In February 1963, a memorandum on Brazil was submitted to the WB executive board. The picture of Brazil under Goulart was bleak and tainted by the fear, among US and WB officials, of an imminent Marxist takeover. According to the memorandum's author, David Beaty III, over the previous 15 years ‘the communist party has been making great headway in placing members of its apparatus in key government posts’. Furthermore, ‘when Jango Goulart became president he brought with him a group of leftist advisors, thereby accelerating this infiltration into important key positions’.Footnote 64 On the economic front, inflation was rising by 50 per cent year-on-year. In October 1962, the last gold reserves of around US$60 million were sold to satisfy commercial debts. Beaty estimated that Brazil's exports would be US$150 to US$200 million less than in 1961, partly because coffee exports (which accounted for 60 per cent of Brazil's export) were, through November 1962, 620,000 bags less than in 1961, or down about 4 per cent. Distrust in the economic policies and institutional reforms of the Goulart government was also evident in Beaty's memorandum. A new law on profit remittances and a revised income tax law were especially criticised: ‘due to the lack of confidence in the administration of these laws, the effect has been to accelerate the flight of capital out of Brazil and further discourage the foreign investor’. If in the past years foreign investments had provided around US$300 million per year to Brazil's balance of trade, with the ‘present lack of confidence almost all of this will be lost to the country’.Footnote 65 Beaty concluded, ‘what do we look forward to in Brazil?’ He expected growing nationalism, ‘continuation towards the socialistic state’ and ‘further infiltration on the part of the communists into key government posts and trade unions’.

In March 1963, finance minister San Tiago Dantas was scheduled to meet with George Woods, former chairman of First Boston Corporation who succeeded Black as president of the WB in 1963. As indicated above, the goal of Dantas's visit was to illustrate the Plano Trienal to Woods in the hope of receiving US, IMF and WB support. The task was made more difficult by the government's inflationary policies and by the shaky external financial position resulting from an overvalued exchange rate, a poor cocoa harvest and an uncertain coffee policy.

Prior to this meeting, Schmidt prepared a memorandum to brief Woods. According to Schmidt, the biggest issues facing Brazil were: excessive investments in politically motivated projects; excessive fiscal deficits financed by the Central BankFootnote 66 fuelling inflation; monetary inflation; external imbalance because of excessive imports; excessive indebtedness because of the reliance on short-term borrowing; last but not least, anaemic economic growth. With regards to the attitude of the Bank towards Brazilian requests for assistance, Schmidt suggested Woods take a hard stance. According to Schmidt, ‘until Brazil takes measures to strengthen its financial positions and use its resources more efficiently, neither the IDA nor the Bank can help’.Footnote 67 The IMF shared the same view and de Vries reported: ‘Although the meeting had been held in a friendly atmosphere, the Fund officials had made it clear that the Fund could not enter into a new standby agreement on the basis of the steps the Brazilians had taken thus far, but that more performance was needed.’Footnote 68

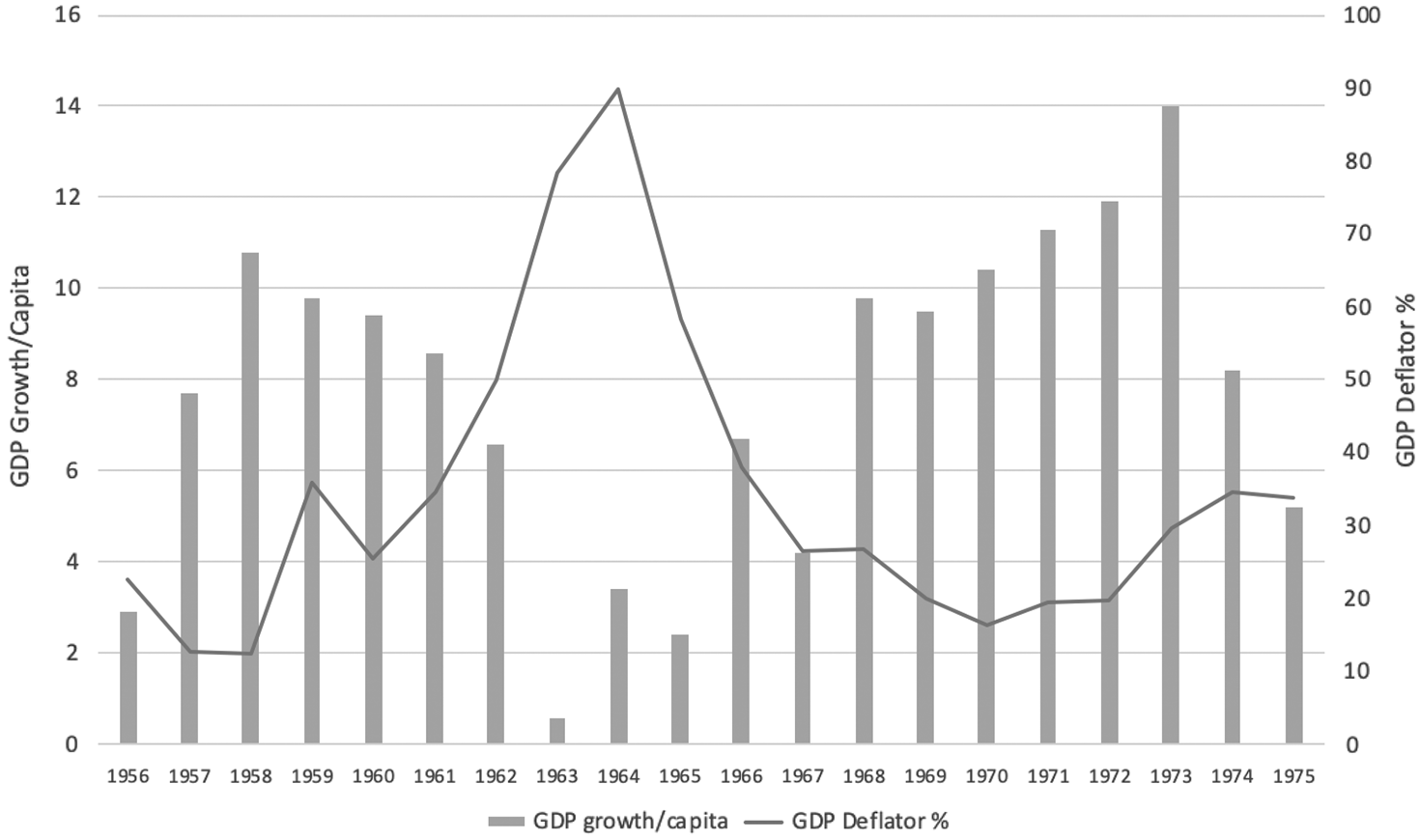

On the Bank's side, even before sending a mission to assess the economic position or study potential projects, ‘the Bank would want to know that Brazil has a program capable of achieving the desired objectives and have the Government take some steps toward carrying it out’. Under these circumstances, the meeting which took place on 13 March was not really conclusive. Dantas illustrated Brazil's economic plans, asked for an economic mission to visit Brazil ‘right away’ and invited Woods and his wife to visit the country. Woods replied that he couldn't commit to when such a mission would take place, saying: ‘it might be next summer or it might be in the fall’. With regards to the personal invitation, Woods said that ‘he would certainly like to do so soon but could not say just when it would be possible’. As Figure 2 shows, the macroeconomic and political situation in Brazil was spiralling out of control, or, at least, this was the perception of foreign investors.

Figure 2. GDP/capita growth and GDP deflator in Brazil, 1956–75

Source: IBGE Estatísticas Históricas do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, 1990.

The Brazilians sent a new mission headed by Carlos Alberto Alves de Carvalho Pinto, the new minister of finance who replaced Dantas, to have a meeting with WB officials in Washington in October 1963. After the usual courtesies, Carvalho Pinto opened by saying that the government of President Goulart had been working hard to rectify its ‘critical financial situation’.Footnote 69 Coping with a severe recession accompanied by rising fiscal deficits and inflation (Ayres et al. Reference Ayres, Garcia, Guillen and Kehoe2018), cash and support were badly needed. Weakened financially and increasingly challenged on the political front, the meeting between Carvalho Pinto and the WB took place during one of the most difficult periods of Goulart's presidency. Since September 1963, the failure of the anti-inflationary measures and the final defeat of Goulart's ambitious agrarian reform weakened the president on both sides of the political spectrum. In Santos, a general strike was coordinated by the powerful Comando Geral dos Trabalhadores (CGT). The same month, lower-rank officers occupied several locations in Brasilia, including the Ministry of the Navy and the National Congress, establishing the Comando Revolucionario de Brasilia. The revolt only lasted 12 hours, following which over 500 members of the military were imprisoned. Carvalho Pinto was adamant in pointing out that it would take time to put together a plan that would satisfy the IMF but he hoped that the Bank would be ready when this finally happened ‘since Brazil would subsequently have to depend very much on the Bank’. Given Brazil's financial needs, particularly worrisome was the structure of the country's debt. Cut off from most sources of long-term financing, Brazil had to resort to short-term loans that were aggravating its already precarious balance sheets. After this initial statement, Carvalho Pinto went straight to the point and ‘inquired whether the Bank was prepared to resume lending to Brazil’.

Woods was not impressed by Carvalho Pinto's request. He told his interlocutor that ‘the Bank would very much like to resume lending to Brazil but it would have to be at the proper time and under the proper conditions’. Crucially, before making any decision in favour of Brazil there would have to be a ‘meeting of minds with the IMF’. Also, Knapp stressed, Brazil would first need to ‘rectify the position of her budget, balance of payments and external debt’. The meeting ended in failure, with Brazil continuing not to receive any help for the time being from the Bank.

Mirroring the attitude of the IMF, the troubled relationship with the Bank did not mean that the contacts between the Bank and the Brazilian government were interrupted completely. In November 1963, a few weeks after Carvalho Pinto's mission, de Vries flew to Brazil to attend the Inter-American Economic and Social Council. During and after the conference, he spent time in Brazil in a private capacity. After talking to São Paulo industrialists, de Vries reported to the Bank that they were ‘very discontented with the lack of leadership displayed by Goulart, but, on the other hand, also seemed quite confident of the future’.Footnote 70 The ‘root of the problem’ in Brazil, according to de Vries, was the deficit in the public sector which was expected to reach around US$400 million by 1963; de Vries reported that he left Brazil ‘with the feeling that in no single sector was the Government trying to achieve any retrenchment’. The cause of these huge deficits was, de Vries reported, twofold. On the one hand, the Brazilian government was investing at an unsustainable rhythm, on the other, President Goulart was too weak when dealing with labour demands. The latter aspect had resulted in a government wage bill taking up an increasing share of total expenditures, and a substantial operating deficit for the railroads and the merchant marine. According to de Vries, ‘Even if Goulart were to be replaced by a much stronger Government, it would have a hard time managing the persistent demands for higher wages which broad sectors of the population have come to expect with large-scale industrialisation and urbanisation, and the improvement in communications.’

The very last meeting between the democratic government of Brazil and the Bank took place in Geneva on 25 March when Woods met Vilar de Queiroz, who was in charge of the renegotiation of Brazilian debt. After making it clear to Woods that ‘there is NO [sic] suggestion that any debt owing by Brazil to the World Bank should be rescheduled’, Woods told de Queiroz to visit him at the Bank the following week when a Brazilian delegation was scheduled to be in Washington, DC, for consultations. This meeting was fated never to take place, as the military coup of 1964 overthrew the democratically constituted government of Brazil and inaugurated one of the longest periods of military rule in Latin America in the past century.

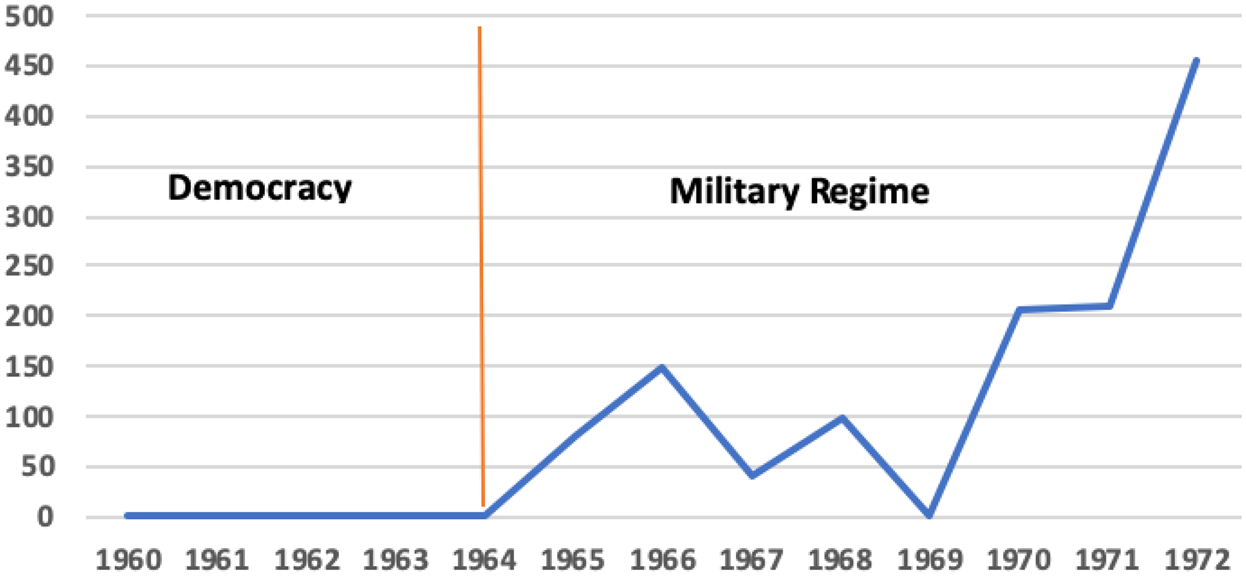

As Figure 3 illustrates, once Goulart was out of the way, the relationship between Brazil and the WB changed dramatically, so that it is possible to talk of a before and after scenario economically as well as politically.

Figure 3. World Bank lending to Brazil, 1960–72 (in million US$)

Source: World Bank projects and operations https://projects.worldbank.org

V

A mere month after the coup, Knapp met with two officials from the US State Department prior to their departure on a six-day mission to Brazil, in order to update them about the Bank's ‘current thinking’ on Brazil.Footnote 71 After outlining the problems between the Bank and the Goulart administration over the previous few years, Knapp told his guests that ‘the Bank may soon want to take a fresh look at the situation in Brazil and determine whether it can resume lending on a larger scale’. The first act of the new relationship between the Bank and the regime was the invitation extended to Woods by Bulhões, to send a mission to Brazil as soon as possible. Bulhões wrote to Woods that ‘it is my conviction that the financial measures now being undertaken by this Government will go to a long way towards creating an appropriate climate’.Footnote 72 The invitation was forwarded to Woods by Israel Klabin, an industrialist and heir to Klabin Irmãos & Cia. KlabinFootnote 73 had been invited to the United States by a group of American bankers and industrialists, led by David Rockefeller as chairman of the Business Group for Latin America, who were interested in developing business relations between the Brazilian and American communities. The group of Brazilian businessmen included several representatives from the Institute for Economic and Social Research (IPES) including one of its founders, Paulo Ayres Filho, who in 1987 said that ‘the 1964 Revolution was made in my living room’ (Schneide Reference Schneide2019, p. 159).

During his North American tour, Klabin also visited Knapp. The latter's attitude during this visit was markedly different from previous encounters with Brazilian delegates. Knapp ‘assured Mr. Klabin that the Bank is very eager to work closely with the new Brazilian government’.Footnote 74 Woods, not entirely surprisingly, responded positively to Bulhões's request and replied that he had instructed Schmidt, de Vries and two other officials to visit Brazil in the third week of June. The ‘Schmidt mission’ that arrived on 23 June in Rio, less than three months after the coup, inaugurated a long and fruitful relationship between the WB and Brazil's military regime. The goal of the mission was to prepare the ground for a larger mission later that year.

Once back in Washington, Schmidt reported on his trip to the country. He remarked that the ‘first matter to record is the important change in the general climate in Brazil’.Footnote 75 Schmidt was especially appreciative of the ministerial team composed of ‘men of integrity and competence’, starting with Bulhões (minister of finance), Mauro Thibau (minister of mines and energy), Juarez Távora (minister of transportation), Campos (minister of planning) and Vasco Leitão da Cunha (minister of foreign affairs). During discussions held with Benedicto Dutra (deputy minister of mines and energy), the Bank decided to support several projects for an initial amount of US$75 million (around US$600 million today). The relationship with a large and prestigious institution such as the WB was not only essential to secure funding for development projects but also, and probably more importantly, for political reasons. The political role that the Bank played was evident to Brazilian policymakers. During a high-level meeting in Tokyo in September 1964, which included Woods, Knapp and Bulhões among others, Bulhões began the meeting by inviting Woods to Brazil, adding that ‘such a visit was important for political reasons’.Footnote 76 Woods replied cordially that he was ‘personally very sympathetic to the idea of visiting Brazil’.

The relationship between the Bank and the Brazilian regime, despite ups and downs, continued to strengthen in the second half of the 1960s. After the first loans that followed Schmidt's mission money continued to flow into Brazil. In April 1965, the WB Loan Committee authorised a one-year lending programme of US$130 million for three power projects, which was subsequently raised to US$150 million.

The Bank remarked in September 1965 that ‘Since the revolution, the Government has given ample evidence of capacity to take decisive action on difficult and unpopular issues of policy and institutional reform.’Footnote 77 By June 1966, the issue on the table was whether to increase by a further US$200 million the loans to be made during the fiscal year 1966–7. The Bank appreciated that the increase in prices had been slowed, that the government's budget deficit had been cut, that export controls and price subsidies had been eliminated, and that the government was pursuing a flexible exchange rate policy. On the negative side, inflation proved to be more stubborn than anticipated.Footnote 78 Ultimately, the confidence in the regime's policies justified an increase of US$200 million in Bank loans for the period 1966–7. The flow of money reflected the increased frequency of interactions between the Bank and Brazil, notably a substantial increase in the number of WB economic missions. After neglecting Brazil for more than five years during democratic rule, the Bank now started to pay regular visits to the military regime, sometimes several times per year. By August 1966, a new visit was planned for November–December 1966, the third such mission in less than three years. The Bank was aware of its close links with the regime and recognised that the upcoming 1966 mission was ‘part of a process initiated in 1964 to resume Bank lending operations in Brazil on a significant scale, after several years during which the contacts between Brazil and the Bank were minimal’.Footnote 79 The fact that the Bank was openly speaking of a ‘process initiated in 1964’ seems to suggest that there was a plan to allow the new military regime to access Bank resources prior to the implementation of satisfactory monetary and economic policies, thus suggesting a possible bias in favour of the new regime. The context in which relations were renewed was that of a ‘new government making unprecedented efforts to bring a long and intractable inflation under control’. The Bank, though, quickly realised that even a repressive regime committed to monetary orthodoxy could have trouble eradicating inflation. In their back-to-office report, Bank's officials who visited Brazil (the mission was postponed until January 1967) reported that ‘The main disappointments are in the areas of price stabilization and economic growth.’Footnote 80 In 1966, inflation remained at around 60 per cent, roughly half its 1963 levels but in line with the preceding years.

The end of Castello Branco's mandate coincided with the end of the Campos and Bulhões reign over the Brazilian economy. The new administration of Costa e Silva, who visited Washington to meet Woods in January 1967, heralded the arrival into power of Helio Beltrão at the Ministry of Planning and of the young economist Antônio Delfim Netto at the Ministry of Economy. In his first visit as president-elect, Costa e Silva remarked that the policies of the new administration would continue to be in line with those implemented since the coup namely, ‘austerity, dignity, constraint on Government outlays and maintaining adequate momentum in the process of economic development. Brazil would also continue to keep hers doors open to the inflow of private foreign investment.’Footnote 81

The next six years would be known as the ‘Brazilian economic miracle’ and would be marked by a reorientation of the monetary policy under Delfim Netto in favour of an increased focus on reactivating economic growth made official in the new Plano Estratégico de Desenvolvimento (PED) (Macarini Reference Macarini2000 and Reference Macarini2006). Despite occasional tensions between the Bank and the regime's new technocratic elite, especially in the first two years of the Costa e Silva administration marked by the return of economic heterodoxy, Gerald Alter (director of WHD) would propose an ambitious five-year lending programme to Brazil of US$1 billion, starting from US$75 million in 1968–9 and rising to about US$300 million by 1972–3. The five-year plan was approved by the Bank's Economic Committee in August 1968. By the late 1960s, Brazil had finally become a creditworthy borrower and, consequently, one of the largest recipients of Bank funding. In summary, recently disclosed primary sources allow us to reveal that World Bank officials, despite the insistence on objective economic criteria, also showed a more flexible attitude and generous disposition towards the generals. Contrary to current narratives on the political preference of international financial organisations (e.g. Payer Reference Payer1974), we do not find any concrete evidence that the WB was actively supporting a regime change through ‘destabilizing non-lending’ and, although we also do not find any evidence that the the goal of the WB was to integrate Brazil into the ‘worldwide economic system that the US constructed just after World War II’ (Swedberg Reference Swedberg1986, p. 384), we can see in the WB position a case of ‘indirect political pressure’ intended as economic conditions which carry important consequences for the politics of the debtor country (Swedberg Reference Swedberg1986, p. 384). For Brazil, a society deeply fragmented along socio-economic lines, complying with the requests of the WB involved taking harsh redistributive decisions that could only be carried out by a regime with a firm grip on the social and political sphere. In this case, the authoritarian character of the regime put the military in a much better position to deliver what the WB was demanding.

VI

After being one of the largest clients of the WB in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the WB entered an increasingly confrontational relationship with the left-wing administrations that governed Brazil in the second half of the 1950s until the coup of 1964. Soon after the military takeover, bilateral relations were normalised and, once again, Brazil became one of the largest recipients of WB lending. During the same period, Brazil's relations with the IMF followed a somewhat similar path: relations were tenser when leftist administrations were in power but improved under right-wing dictatorships. Recently disclosed documents from the IMF and the WB archives shed new light on several issues that have hitherto been overlooked by scholars. First, the article has shown that although both institutions shared the same economic principles and a similar ‘special relationship’ with the United States, this did not necessarily imply that they always adopted the same attitude towards different Brazilian governments. In effect, while the WB did not approve any new loan to Brazil's leftist administrations between 1959 and 1964, the IMF proved to be a more flexible partner, granting a highly conditional SBA to Quadros's administration in 1961 and a non-conditional CFF to Goulart's government in 1963. Moreover, the IMF interrupted lending only when Brazil stopped complying with the terms of the SBA.

The fact that the lending patterns of the Fund and Bank towards Brazil before the coup were partially different cannot conceal a basic truth – that neither of them approved Goulart's economic policy and his strong ties with the labour movement, and that both went out of their way to establish fruitful cooperation with the new military regime, even before any concrete macro-economic improvement was achieved. This differential attitude was noticed by contemporaries. In July 1964, The Economist published a provocative article entitled ‘Creditors Prefer Generals’ about the successful rescheduling of Brazil's medium-term debt, suggesting:

The new western warmth towards Brazil seems to have been kindled by the unceremonious departure in April of President Goulart, whose dilatory attitude towards his country's roaring inflation cost his government the sympathy of his creditors. These creditors consider the new regime of President Castello Branco with a kindlier eye, and show no great concern over its incursions into private and political liberties. For Brazil's new government has at least shown convincing signs of trying to restore economic order with credit curbs, cuts in state spending and increased taxation – all the politically unpopular measures before which Senhor Goulart had recurrent bouts of cold feet … (The Economist, 11 July 1964)

What does this undeniable preference mean in terms of the self-imposed ‘political neutrality’ of the IMF and the WB? Did these institutions really prefer generals, and, if this was the case – why?

It is significant that the Plano Trienal launched in 1962 by Goulart and the PAEG launched by Castello Branco in 1964 were similar, both a hybrid mix of orthodox and heterodox economic measures that shared numerous parallels with regards to characteristics and policies. Given that despite the similarity of the economic plans, the two regimes were accorded vastly different treatment at the hands of the IMF and the WB, it seems relevant to suggest that the reasons for this treatment must have been, at least partially, politically motivated.

In fact, as new historical evidence reveals, the IMF and the WB doubted Goulart's political capacity to cut wages, eliminate subsidies and, ultimately, curb inflation. In contrast, the two institutions were confident that a strong, repressive military regime would have the ability to implement a stabilisation plan, even one that would result in a negative impact on the real salaries and purchase power of the workers and lower classes of society. Yet to conclude that the IMF and WB completely violated their self-imposed political neutrality would be somewhat simplistic. While it is true that the Plano Trienal and the PAEG presented several similarities and therefore deserved, at least in principle, the same response, it cannot be denied that the regimes of Goulart and Castello Branco did, in reality, support significantly different economic and social policies, had different scope for political manoeuvering and enjoyed very different levels of political power. The IMF, the WB and international investors in general were certainly well aware of these substantial differences and therefore hesitated or even refused to support Goulart but were keen to support the military regime.

Given that one cannot deny that the IMF and the WB were inclined to work with the Castello Branco military regime even when his economic plan was not fully implemented and/or when it showed alarming signs of an imminent crisis, but, by contrast, significantly downgraded their financial support to populist and left-wing regimes, the question is to what extent did this specific case constitute an anomaly or was it rather part of a broader strategy on the part of the Bretton Woods institutions? Did the IMF and the WB, in fact, prefer working with military rather than democratic regimes and/or with right-wing over populist/reformist administrations? While looking at the (still understudied) experience of other Latin American cases, the picture becomes increasingly complex and significant research must be carried out on a larger number of examples before clear conclusions can be reached. That being said, there are two studies, on Argentina and Chile, that have examined the issue and seem to indicate numerous parallels with the situation in Brazil. In Argentina, the populist administration of President Perón (1946–55) was not even accepted as a member state of the Fund and Bank, with its entry into both institutions not approved until 1956, when the military regime that deposed Perón was in power. This regime, however, which governed the country until April 1958, received neither a WB loan nor an SBA, and was only able, through special permission, to access a small amount of IMF funds. In Chile in the 1970s, the WB management and staff held countless meetings with Allende's economic team but ultimately refused to submit his loan requests to the EB vote (mainly because the US representative threatened to veto any loans to the country). During the same period the IMF did grant Chile three CFFs, and in doing so emerged as the only institution in the Western Bloc to violate the economic embargo that the Nixon administration imposed against this socialist regime. Thus, while both institutions had a certain preference towards the military regimes, it is remarkable that in almost all cases indicated above, and despite the tough image of the IMF in its borrowers’ eyes, it was more flexible and pragmatic than the WB. It would therefore not be illogical to suggest that it was precisely its tough, or even negative, image among leftist, populist and nationalistic political actors in Latin America, that, more than once, led the IMF to adopt a pragmatic and non-confrontational stand that allowed it to remain ‘neutral’ and enabled it to grant these regimes financial support. After all, the IMF's experience in Latin America had certainly taught it that political instability was by no means uncommon and that a new and more (neo)liberal regime would soon come to power. The IMF, which was harshly criticised in the region in the late 1950s and 1960s, by leftists as well as by structuralist economists, made efforts to improve its image in the region, out of fear that countries would stop borrowing from it, and seems to have used its ‘neutrality’ as the means of doing so. The WB, by contrast, was in a much better position than the Fund, as it knew that all regimes would have no choice but to come knocking on its door to request much needed development loans. Therefore, it could allow itself to be less pragmatic, or, in other words, less ‘neutral’.