Introduction

Land protection initiatives are a crucial component of global goals to maintain functioning ecosystem services as a foundation for resilient communities (UN General Assembly 2015). Valuable ecosystem services provided by open space lands include watershed protection, flood control, prevention of soil erosion, cooling, carbon sequestration, cultural heritage, pollination, recreation, and the opportunity to access or experience nature (Reid et al. Reference Reid, Mooney, Cropper, Capistrano, Carpenter, Chopra, Dasgupta, Dietz, Duraiappah and Hassan2005; Daily and Matson Reference Daily and Matson2008; de Groot et al. Reference De Groot, Alkemade, Braat, Hein and Willemen2010; Guerry et al. Reference Guerry, Polasky, Lubchenco, Chaplin-Kramer, Daily, Griffin, Ruckelshaus, Bateman, Duraiappah and Elmqvist2015; Costanza et al. Reference Costanza, De Groot, Braat, Kubiszewski, Fioramonti, Sutton, Farber and Grasso2017; Bratman et al. Reference Bratman, Anderson, Berman, Cochran, De Vries, Flanders, Folke, Frumkin, Gross and Hartig2019). Governments and conservationists are seeking permanent protection for up to 30% of terrestrial and marine areas by 2030 and 50% in the long term (e.g. Dinerstein et al. Reference Dinerstein, Vynne, Sala, Joshi, Fernando, Lovejoy, Mayorga, Olson, Asner and Baillie2019; Díaz et al. Reference Díaz, Zafra-Calvo, Purvis, Verburg, Obura, Leadley, Chaplin-Kramer, De Meester, Dulloo and Martín-López2020). These efforts are backed by substantial funding opportunities. Finance for support of global biodiversity was recently estimated at $78–91 billion per year (OECD 2020). In the U.S., the Great American Outdoors Act is supporting up to $900 million annually for investments in land and water conservation (National Park Service 2020, Walls Reference Walls2020) and the Department of Agriculture is spending more than $6 billion per year through the current farm bill on programs including incentives to restore natural land cover and easements to preserve land from development (Economic Research Service 2019).

Economists have played a key role in establishing the values of ecosystem services and articulating why land protection policies are needed to support their provision (e.g. Salzman et al. Reference Salzman, Thompson and Daily2001; Barbier et al. Reference Barbier, Baumgärtner, Chopra, Costello, Duraiappah, Hassan, Kinzig, Lehman, Pascual, Polasky, Naeem, Bunker, Hector, Loreau and Perrings2009; Boyd et al. Reference Boyd, Ringold, Krupnick, Johnson, Weber and Hall2015; Polasky et al. Reference Polasky, Tallis and Reyers2015; Costanza et al. Reference Costanza, De Groot, Braat, Kubiszewski, Fioramonti, Sutton, Farber and Grasso2017). Economists have also contributed to assessments of the efficacy of land protection policies and recommendations to improve policy design or targeting (e.g. Albers and Robinson Reference Albers and Robinson2007; Somanathan et al. Reference Somanathan, Prabhakar and Mehta2009; Ferraro et al. Reference Ferraro, Hanauer and Sims2011; Pfaff and Robalino Reference Pfaff and Robalino2012; Alix-Garcia et al. Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims and Yañez-Pagans2015; Hellerstein Reference Hellerstein2017; Walls and Kuwayama Reference Walls and Kuwayama2019). As land protection policies continue to grow in budget and scope, economists have an important opportunity and responsibility to analyze how they matter for social equity.

This article reviews three key concerns about how land protection policies may impact equity and assesses evidence for each, drawing on global literature as well as examples from the U.S. I propose areas for future research and pathways forward to potentially improve the equity of land protection policies. Opportunities to move towards greater equity include specific links between land protection and local community benefits, careful zoning and timing, prioritization of equity in policy initiatives, and processes that centre community views and needs. These suggestions focus on specific changes to policy mechanisms or processes that could bring immediate gains. Clearly, broader societal transformations to reduce underlying disparities of income, wealth, or social privilege are also needed to ensure more fundamental and lasting equity in land protection.

Land protection and ecosystem services

Land protection encompasses a broad set of policy initiatives, differing in the degree, goals, and scope of protection across a range of global settings. Figure 1 groups selected policies by the mechanisms that they use to influence landholder choices, as these may play a central role in the equity of each policy. Mechanisms for direct regulation include area-based conservation through parks and sanctuaries (e.g. Maxwell et al. Reference Maxwell, Cazalis, Dudley, Hoffmann, Rodrigues, Stolton, Visconti, Woodley, Kingston and Lewis2020) and rules-based mechanisms, such as wetlands protection laws (e.g. Sims and Schuetz Reference Sims and Schuetz2009) or forest codes (e.g. Assunção et al. Reference Assunção, Gandour, Pessoa and Rocha2017). Area-based conservation can be highly heterogenous in size and scope, ranging from landscape-scale initiatives with an array of strict protection and mixed use (e.g. Blackman Reference Blackman2015) – to the protection of narrow strips of land for urban greenways along rivers or roads (e.g. Lindsey et al. Reference Lindsey, Man, Payton and Dickson2004). In May 2022, the World Database on Protected Areas reported more than 270,000 protected areas across 245 countries and territories with approximately 15% of global land area protected (UNEP-WCMC 2022).

Figure 1. Mechanisms for land protection and examples.

While direct regulation has been a dominant form of land protection, it has also been controversial because it is based on restrictions or prohibitions on use (e.g. Adams et al. Reference Adams, Aveling, Brockington, Dickson, Elliott, Hutton, Roe, Vira and Wolmer2004, Ferraro and Pressey Reference Ferraro and Pressey2015; Oldekop et al. Reference Oldekop, Holmes, Harris and Evans2016). In part due to this pushback, land protection initiatives have also emerged that induce greater voluntary provision of ecosystem services by changing the incentives of landholders. For example, payments for ecosystem services programs (“PES”) seek to compensate landowners with financial or in-kind contributions for avoiding the loss of natural land cover or restoring land uses and habitat that enhance service provision (e.g. Pattanayak et al. Reference Pattanayak, Wunder and Ferraro2010; Alix-Garcia and Wolff Reference Alix-Garcia and Wolff2014; Salzman et al. Reference Salzman, Bennett, Carroll, Goldstein and Jenkins2018). Payments for ecosystem services have grown in popularity, with large national programs in place for at least five to ten years in Mexico, Costa Rica, China, Ecuador, Peru, Brazil, Vietnam, and the U.S. (Alix-Garcia et al. Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims, Orozco-Olvera, Costica, Fernández Medina and Romo Monroy2018). Conservation easements, which place long-term legal restrictions on the use of land, have also increased dramatically as a form of private protection, particularly in the U.S. (Parker and Thurman Reference Parker and Thurman2019).

Land may also be protected by changing the locus of decision-making to support collective action, usually by giving more control to local communities over resource rules and use (e.g. Andersson and Ostrom Reference Andersson and Ostrom2008). These community-based or joint forest management policies are important initiatives, as local communities have legal rights to more than 15% of the world’s forests (Rights and Resources Initiative 2017). Decentralized decision-making rests on the idea that communities can use place-specific knowledge to make and implement more sustainable and effective management of local resources than would be imposed by central regulations (e.g. Chhatre and Agrawal Reference Chhatre and Agrawal2009; Somanathan et al. Reference Somanathan, Prabhakar and Mehta2009; Baland et al. Reference Baland, Bardhan, Das and Mookherjee2010; Khanal Reference Khanal2013).

Although operating through different mechanisms and in an array of very different institutional settings, land protection policies share a common goal: to shift land-use or land-cover patterns towards those that are socially valuable, but tend to be underprovided by dominant market structures. Left to themselves, land markets operating with few restrictions will tend to allocate land to the most profitable private uses, rather than the most beneficial social ones. This is the result of individual choices by landowners, resting on the comparison of potential returns or “rents” to uses on each parcel, including agriculture, pasture, forestry, natural land covers, or developed residential, commercial, or industrial uses (e.g. Chomitz and Gray Reference Chomitz and Gray1996; Irwin and Geoghegan Reference Irwin and Geoghegan2001; Irwin et al. Reference Irwin, Bell, Bockstael, Newburn, Partridge and Wu2009; Barbier et al. Reference Barbier, Burgess and Grainger2010; Alix-Garcia et al. Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims and Yañez-Pagans2015). Individual decisions to allocate land to the highest rent use lead to familiar patterns, such as the concentric circles of land-use types around cities described by Von Thünen (e.g. Walker Reference Walker2021), and familiar pressures, such as the rapid conversion of ecologically rich forests or sustainable agricultural systems to industrial agriculture or suburban and urban development (Barbier and Burgess Reference Barbier and Burgess2001; Irwin and Bockstael Reference Irwin and Bockstael2004).

Crucially, these market-driven private choices do not tend to result in patterns of land use that are socially best, particularly from an ecosystem services perspective. Land in natural wetlands, in forests, in meadows and prairies, and even in small strips or parcels of buffer vegetation, hedgerows, or urban gardens, provide tremendously valuable, life-sustaining ecosystem services (Reid et al. Reference Reid, Mooney, Cropper, Capistrano, Carpenter, Chopra, Dasgupta, Dietz, Duraiappah and Hassan2005; Daily and Matson Reference Daily and Matson2008; de Groot et al. Reference De Groot, Alkemade, Braat, Hein and Willemen2010; Guerry et al. Reference Guerry, Polasky, Lubchenco, Chaplin-Kramer, Daily, Griffin, Ruckelshaus, Bateman, Duraiappah and Elmqvist2015; Costanza et al. Reference Costanza, De Groot, Braat, Kubiszewski, Fioramonti, Sutton, Farber and Grasso2017; Bratman et al. Reference Bratman, Anderson, Berman, Cochran, De Vries, Flanders, Folke, Frumkin, Gross and Hartig2019). Yet since most ecosystem service values accrue to other people beyond the individual landholder, they are not easily factored in to the individual choices that dominate land-use changes. Indeed, these positive externalities lead to a core market failure: private markets will tend to underprovide land-use types with crucial ecosystem service benefits. Despite their high social value, lands with important ecosystem service value will always be in short supply unless communities and policymakers engage intentionally in collective action, voluntary private provision, or effective public efforts.

Key equity concerns of land protection

Although land protection policies are clearly needed to sustain functioning ecosystems, they interact in complex ways with economic distribution and social equity. In general, land protection policies change the structure of private rents and social values, creating new winners and losers. From an equity perspective, this raises substantial concerns, particularly where land protection deepens existing disparities or further privileges the already privileged.

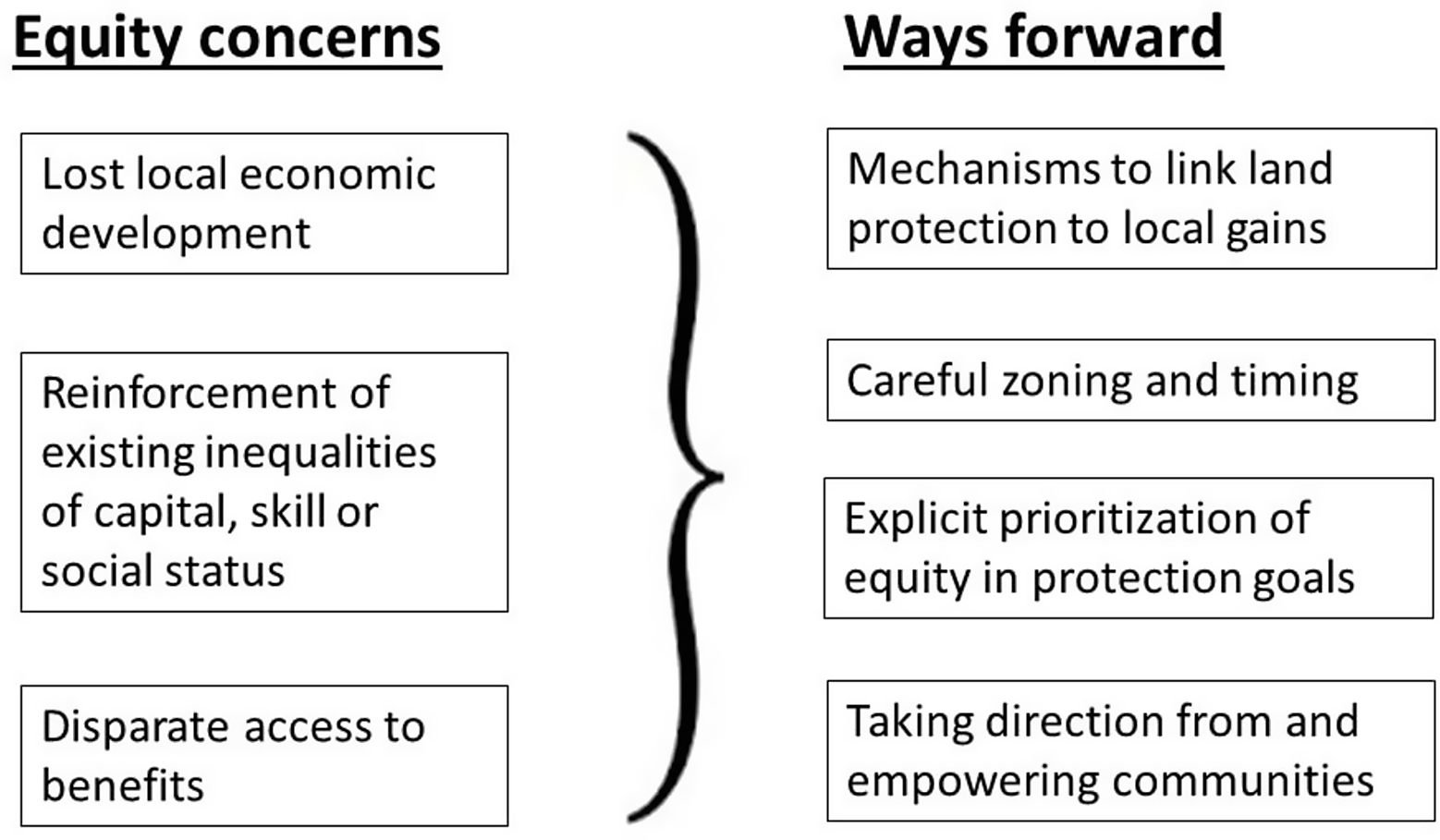

In particular, three major equity concerns emerge from economic frameworks. Land protection may result in: (1) lost local economic development or increased local poverty due to the costs of land protection; (2) economic development opportunities that differentially reinforce existing inequalities of capital, skill, or social hierarchies; and (3) patterns of access to the benefits of protected land that reflect and reinforce broader social disparities. As described below, there is substantial evidence from existing literature that each of these is a real concern, both domestically and globally. Additional research by economists could play an important role in understanding these dimensions, highlighting the conditions under which equity concerns are most likely, and recommending or testing changes in policies or process that may reduce disparities. Figure 2 previews the key concerns and pathways forward that are developed in the rest of this article.

Figure 2. Equity concerns of land protection and potential pathways for improvement.

Lost local economic development or increased local poverty due to land protection

The concern that land protection may harm local economic development and exacerbate local poverty stems from the inherently inequitable spatial distribution of benefits and costs of many land protection policies (Dixon and Pagiola Reference Dixon and Pagiola2001). The majority of the benefits of land protection are often regional or global. For example, payments for biodiversity conservation and biosphere reserves in Mexico support species that are nationally and internationally important (Koleff et al. Reference Koleff, Urquiza-Haas, Ruiz-GonzáLEZ, Hernández-Robles, Mastretta-Yanes, Quintero, Sarukhán and Pullaiah2018). Nepal’s community forests provide carbon sequestration that contributes to global climate goals (Chhatre and Agrawal Reference Chhatre and Agrawal2009). In Thailand, forested areas in the north of the country protect watersheds that support the agricultural and urban areas of the central plains (Emphandhu and Chettamart Reference Emphandhu and Chettamart2003). Yet the costs of land protection – including in the cases above – are mainly local.

The most extreme potential local costs anywhere in the world are from direct displacement through forced resettlement: the livelihoods and social capital lost if communities are removed from protected areas or forced out by environmental regulations (e.g. Dowie Reference Dowie2005; Brockington and Igoe Reference Brockington and Igoe2006; Curran et al. Reference Curran, Sunderland, Maisels, Oates, Asaha, Balinga, Defo, Dunn, Telfer and Usongo2009; Krakoff Reference Krakoff2018). However, even without direct displacement, land protection policies usually restrict local options for livelihoods or development by prohibiting or restricting certain uses or extractive activities. Land protection may potentially mean reduced subsistence agriculture, lost rents from higher profit land uses, lost rights to grazing, hunting and fishing, reductions in the collection of timber or non-timber forest products, or slower growth of regional economies (e.g. Dixon and Sherman Reference Dixon and Sherman1990; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Hunt and Plantinga2002, Reference Lewis, Hunt and Plantinga2003, Robalino Reference Robalino2007; Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Albers and Williams2008; Sims Reference Sims2010). Depending on governance structures, land protection may also lead to losses of potential tax revenue for local communities due to less commercial or residential development (e.g. King and Anderson Reference King and Anderson2004; Vandergrift and Lahr Reference Vandegrift and Lahr2011; Kalinin et al. Reference Kalinin, Sims, Meyer and Thompson2023).

Although these concerns about high local costs are very real, land protection may instead help to encourage local growth or alleviate poverty by solving collective action problems or creating new economic opportunities. Benefits may include improved infrastructure such as road networks, increased ecosystem services such as water provision or timber and non-timber forest products, recreation-based employment opportunities, and amenity-driven growth (e.g. Dixon and Sherman Reference Dixon and Sherman1990; Sims Reference Sims2010; Ferraro and Hanauer Reference Ferraro and Hanauer2014; Rasker et al. Reference Rasker, Gude and Delorey2013).

A key empirical challenge in this literature is that land protection initiatives are often targeted to areas that are poorer and more isolated at baseline – for reasons of political economy or cost (e.g. Joppa and Pfaff Reference Joppa and Pfaff.2009). Therefore, simple comparisons of poverty rates between areas with and without land protection are often confounded by these underlying differences (Andam et al. Reference Andam, Ferraro, Sims, Healy and Holland2010; Ferraro et al. Reference Ferraro, Hanauer and Sims2011). An increasing body of evidence, with substantial contributions from agricultural and resource economists, uses quasi-experimental methods (and occasionally true randomized controlled trials) to account for selection bias and to estimate impacts relative to the development trajectories likely to have occurred in the absence of land protection policies.

With respect to protected areas, this literature indicates mixed results, with evidence for both net local economic losses and gains, depending on the context (Table 1). Several studies from a variety of global settings have found that protected areas contributed positively in net to poverty alleviation or local growth. In Thailand and Costa Rica, for example, Andam et al. (Reference Andam, Ferraro, Sims, Healy and Holland2010) found that protected areas reduced poverty headcounts for sub-districts or census tracts near parks. Protected areas in Nepal (Yergeau et al. Reference Yergeau, Boccanfuso and Goyette2017; den Braber et al. Reference den Braber, Evans and Oldekop2018), Bolivia (Canavire-Bacarreza and Hanauer Reference Canavire-Bacarreza and Hanauer2013), and Cambodia (Clements et al. Reference Clements, Suon, Wilkie and Milner-Gulland2014, Reference Clements, Neang, Milner-Gulland and Travers2020) also reduced poverty rates or improved local incomes for nearby households. Research on protected federal lands in the rural U.S. West (Rasker et al. Reference Rasker, Gude and Delorey2013; Walls et al. Reference Walls, Lee and Ashenfarb2020) found that these lands led to increased local per capita income or growth of employment opportunities, while Sims et al. (Reference Sims, Thompson, Meyer, Nolte and Plisinski2019) found that employment rates in New England towns and cities were boosted by new land protection. Using data from 34 developing countries, Naidoo et al. (Reference Naidoo, Gerkey, Hole, Pfaff, Ellis, Golden, Herrera, Johnson, Mulligan and Ricketts2019) found that children living near protected areas with tourism were better off than comparable children far away from these areas, and Kandel et al. (Reference Kandel, Pandit, White and Polyakov2022) found overall positive impacts in a globally focused meta-analysis of protected area impacts.

Table 1. Protected area impacts on local communities – quasi-experimental evidence

At the same time, multiple rigorous studies in this literature have found evidence for negative impacts or for a lack of positive local impacts from protected areas, particularly in the short run. Ferris and Frank (Reference Ferris and Frank2021) found short-term job losses in the timber industry due to the U.S. Northwest Forest Plan, which restricted logging in large areas previously open for public concessions, while Lewis et al. (Reference Lewis, Hunt and Plantinga2002) found no impacts of the plan on county level growth in the medium-term. Howlader and Ando (Reference Howlader and Ando2020) find that protected areas in Nepal reduced household access to firewood, while Miranda et al. (Reference Miranda, Corral, Blackman, Asner and Lima2016) find no robust gains for poverty alleviation due to parks in the Peruvian Amazon. Sims and Alix-Garcia (Reference Sims and Alix-Garcia2017) find that strictly protected areas in Mexico led to less poverty alleviation than in similar comparison localities. Cheng et al. (Reference Cheng, Sims and Yi2023) found mixed results of China’s protected areas, with positive effects on local poverty alleviation but possible negative impacts on employment. This is consistent with previous mixed results from studies of selected giant panda reserves (Duan and Wen Reference Duan and Wen2017; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Cai, Zheng and Wen2019) and China’s National Forest Protection Program (Mullan et al. Reference Mullan, Kontoleon, Swanson and Zhang2010). In addition, the meta-analysis by Kandel et al. (Reference Kandel, Pandit, White and Polyakov2022) found that studies from African countries were less likely to show positive welfare impacts than those from Asia or South America, indicating important heterogeneity across contexts.

This record of mixed evidence regarding the impacts of protected areas is perhaps not surprising, given that protected areas present both restrictions and opportunities. Payments for ecosystem services programs, on the other hand, have often been expected to contribute more positively to local economic development because they are voluntary and provide direct compensation for environmental stewardship (Pagiola et al. Reference Pagiola, Arcenas and Platais2005; Engel et al. Reference Engel, Pagiola and Wunder2008; Jack et al. Reference Jack, Kousky and Sims2008; Alix-Garcia et al. Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims and Yañez-Pagans2015). PES should theoretically only induce households or communities to enroll if the expected benefits are higher than the costs of participating.

However, in reality, gains for local communities from PES are not guaranteed and may not be universal. Recipients may not understand the tradeoffs involved, the programs may not be fully voluntary, the payments may just cover participation costs, or PES may be beneficial for a community as a whole but have negative impacts on some members or on the social fabric of a community. There is less existing research about the socioeconomic impacts of payments for ecosystem services than for protected areas, but studies from a variety of locations generally support the idea that PES in practice has had small positive or neutral impacts for local communities (Table 2). Evidence for large positive gains, however, has been elusive, and some concerns have emerged.

Table 2. Payments for ecosystem services, community-based forestry impacts on local communities – quasi-experimental evidence

A small number of studies on PES find statistically significant evidence for positive household impacts. For example, Alix-Garcia et al. (Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims and Yañez-Pagans2015) found that in Mexico, early cohorts of the federal payments for hydrological services program resulted in reductions in locality poverty and gains in household wealth for poor households, as measured by ownership of durable goods and quality of home structures. Liu and Lan (Reference Liu and Lan2015, Reference Liu and Lan2018) found positive impacts of China’s Sloping Land Conversion program on household diversification of livelihoods as well as productivity. Adjognon et al. (Reference Adjognon, van Soest and Guthoff2021) found that a PES program in Burkina Faso that compensated households for maintenance of newly planted trees clearly improved food security; Clements et al. (Reference Clements, Neang, Milner-Gulland and Travers2020) also found that some types of PES in Cambodia likely improved food security.

At the same time, the hope that PES would lead to very strong gains for local livelihoods often has not materialized. Several studies, including from later PES cohorts in Mexico, Costa Rica, Brazil, and the U.S. Conservation Reserve program, find no substantial effects on livelihoods, food security, or local growth (Table 2). A possible key reason for this is that in addition to the opportunity costs of PES, the participation and transaction costs of many programs have been higher than anticipated. Participation costs in PES include the time and vehicle costs of monitoring, as well as labor-intensive management practices such as building fire breaks, undertaking pest control, or installing and maintaining fencing. For example, in the case of Mexico’s PES, Alix-Garcia et al. (Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims and Yañez-Pagans2015) estimated that the value of additional labor devoted to forest management activities was equivalent to 84% of the average payments for communal properties.

The distributional impacts of PES may also depend strongly on local land ownership patterns. For example, PES programs may result in shifting labor allocation within households (e.g. Jack and Cardona-Santos Reference Jack and Santos2017) or may lower the demand for agricultural labor, reducing incomes of non-landholding households. Villalobos et al. (Reference Villalobos, Robalino, Sandoval and Alpízar2023) found that Costa Rica’s PES may have increased poverty in places where land is owned mainly by wealthier households, consistent with a situation where landholding households benefitted from the program payments but landless laborers lost agricultural job opportunities.

An additional reason why the socioeconomic gains due to PES may be small is due to the inherent tension between program goals of increasing the land area enrolled versus supporting meaningful gains for those participants who are enrolled (e.g. Kirwan et al. Reference Kirwan, Lubowski and Roberts2005; Pagiola et al. Reference Pagiola, Arcenas and Platais2005; Zilberman et al. Reference Zilberman, Lipper and McCarthy2008; Alix-Garcia et al. Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims and Yañez-Pagans2015, Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims and Phaneuf2019). Policymakers seeking to protect as much land as possible on a limited budget should set PES payments just high enough to induce participation (e.g. Alix-Garcia et al. Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims and Phaneuf2019). However, lower payments mean less surplus for landowners and thus less potential for PES to substantially reduce poverty or improve local economic development (e.g. Zilberman et al. Reference Zilberman, Lipper and McCarthy2008; Alix-Garcia et al. Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims and Yañez-Pagans2015). Greater budgets and higher payments will likely be necessary to truly improve local livelihoods. Yet, this recommendation raises broader questions about whether other social programs would be more effective or efficient in combatting poverty directly than PES. Little research to date has been able to explore the long-term social impacts of PES versus other social support programs in order to inform this debate.

Concerns have also been raised that the introduction of additional external funds to communities through PES programs may be disruptive to local norms or traditions of voluntary contributions (e.g. Bowles Reference Bowles2008; Muradian Reference Muradian2013; Pascual et al. Reference Pascual, Phelps, Garmendia, Brown, Corbera, Martin, Gomez-Baggethun and Muradian2014). For example, Ravikumar et al. (Reference Ravikumar, Uriarte, Lizano, Farré and Montero2023) finds that Peru’s PES funding structure – which required program recipients to establish new local businesses – did not promote opportunities that were well matched with local skills and may have undermined traditions of shared labor. In contrast, researchers in Mexico found that PES did not decrease contributions of labor to shared community activities and increased social capital (Alix-Garcia et al. Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims, Orozco-Olvera, Costica, Fernández Medina and Romo Monroy2018). Vorlaufer et al. (Reference Vorlaufer, Laat and Engel2023) also found that in Uganda, PES did not lead to lasting shifts in resource sharing practices and may have induced stronger long-term norms for resource sharing. Given the importance of understanding the deeper social impacts of PES, there is considerable scope for future collaboration between researchers using both qualitative and quantitative methods to further investigate potential context-specific channels of social change driven by land protection initiatives.

In addition to the impacts of protected areas and PES, a growing body of research also explores the local economic impacts of community-based management and other types of land protection. Several studies have shown that community-based forest management interventions can result in positive gains for local livelihoods or for economic development. In Nepal, Paudel (Reference Paudel2018) found that households with access to community forests had greater food consumption, while Oldekop et al. (Reference Oldekop, Sims, Karna, Whittingham and Agrawal2019) found greater reductions in poverty for localities with more land devolved to community forests, compared to matched control areas. Santika et al. (Reference Santika, Wilson, Budiharta, Kusworo, Meijaard, Law, Friedman, Hutabarat, Indrawan and St. John2019) found livelihood gains from community forestry initiatives in Indonesia compared to matched controls, but substantial heterogeneity across interacting conservation zone types. Bocci et al. (Reference Bocci, Fortmann, Sohngen and Milian2018) found that community-managed forest concessions in Guatemala were generally positive for rural livelihoods, and Rasolofoson et al. (Reference Rasolofoson, Ferraro, Ruta, Rasamoelina, Randriankolona, Larsen and Jones2017) found small positive impacts of community forests on household consumption expenditures in Madagascar. Community-based conservation in Namibia was found to have supported increased livelihoods but also increased human–wildlife conflicts and may have reduced food security (Meyer and Börner Reference Meyer and Börner2022).

Evidence on certification and land tenure initiatives is also emerging. Miteva et al. (Reference Miteva, Loucks and Pattanayak2015) found that forest certification in Indonesia reduced firewood dependence and improved health outcomes. A review of forest-focused sustainable supply chain initiatives in Brazil finds that they have increased farm incomes (Garrett et al. Reference Garrett, Levy, Gollnow, Hodel and Rueda2021). Recent work also indicates that land tenure interventions may improve human well-being outcomes in some cases (Tseng et al. 2021), although they may not necessarily have positive impacts for ecosystem services unless coordinated with other protection efforts (e.g. Probst et al. Reference Probst, BenYishay, Kontoleon and dos Reis2020).

Despite substantial progress in understanding the livelihood impacts of land protection across multiple mechanisms, there is considerable room for additional research. In particular, there are only a small number of rigorous, quasi-experimental evaluations of the socioeconomic impacts of indigenous protected areas (e.g. BenYishay et al. Reference BenYishay, Heuser, Runfola and Trichler2017), regulatory requirements such as Brazil’s forest code (e.g. Assunção and Rocha Reference Assunção and Rocha2019), efforts to link credit provision to compliance (e.g. Assunção et al. Reference Assunção, Gandour, Rocha and Rocha2020), or global restoration initiatives (Strassburg et al. Reference Strassburg, Iribarrem, Beyer, Cordeiro, Crouzeilles, Jakovac, Braga Junqueira, Lacerda, Latawiec and Balmford2020). In particular, if past efforts are a guide, current massive efforts to restore forests and biodiversity may require labor and land resources that impose substantial burdens on the global poor unless compensation mechanisms are dramatically increased (Brancalion et al. Reference Brancalion, Meli, Tymus, Lenti, Benini, Silva, Isernhagen and Holl2019; Erbaugh et al. Reference Erbaugh, Pradhan, Adams, Oldekop, Agrawal, Brockington, Pritchard and Chhatre2020). There is also substantial room for new synthesis work that compares the findings from multiple studies using meta-analysis or theory-driven comparisons based on compilations of literature (e.g. Ferraro et al. Reference Ferraro, Hanauer and Sims2011; Pfaff and Robalino Reference Pfaff and Robalino2012; Hajjar et al. Reference Hajjar, Oldekop, Cronkleton, Newton, Russell and Zhou2021). To inform equity dimensions, this work can continue to investigate systematic predictors of local costs or benefits for all types of land protection as well as the dimensions of tradeoffs between greater ecosystem services and gains for local livelihoods that have been found in specific studies (e.g. Alix-Garcia et al. Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims and Yañez-Pagans2015; Pfaff et al. Reference Pfaff, Robalino, Herrera and Sandoval2015).

Reinforcement of existing inequalities of capital, skill, or social status

A second key equity concern is that the economic opportunities that land protection provides may reinforce existing disparities in wealth, skill, or social status. As described above, there are many documented cases in which land protection has helped to sustain or increase local economic activities. These tend to be activities that require collective action, and therefore benefit from government intervention, support of community governance, or legal easements that facilitate access to lands. In particular, land protection frequently supports new economic activity based on recreation or tourism (Dixon and Sherman Reference Dixon and Sherman1990; Wu and Plantinga Reference Wu and Plantinga2003; Rasker et al. Reference Rasker, Gude and Delorey2013; Koontz et al. Reference Koontz, Thomas, Ziesler, Olson and Meldrum2017). Land protection may also help to maintain businesses that rely on the sustainable harvest of natural products including timber and non-timber forest products, or may provide access to these resources in times of economic distress (Vasquez and Sunderland Reference Vasquez and Sunderland2020; Ferraro and Simorangkir Reference Ferraro and Simorangkir2020; Murray et al. Reference Murray, Catanzaro, Markowski-Lindsay, Butler and Eichman2021). However, these possibilities also raise concerns that the type of development opportunities created by land protection may especially reinforce existing inequalities of capital or skill. Many of the types of economic activity that are compatible with land protection require substantial start-up costs or prior knowledge, e.g. capital for lodging, restaurants, or guide services; language, marketing and accounting skills to effectively compete in and benefit from recreation economies or eco-tourism. Literature on the political economy of environmental regulation generally supports the notion that regulations tend to create high fixed costs of compliance, which may favor larger scale, well-capitalized business operations (Heyes Reference Heyes2009).

The literature that explores how land protection in particular has affected inequality, capitalization, or the scale of businesses is limited, but there are enough examples of supporting evidence to indicate this is an area of concern. For example, Sims (Reference Sims2010) finds that protected areas in Thailand increased local-level inequality even though they reduced poverty overall. This is consistent with a situation where more of the gains from tourism went to households that were already better off. In Costa Rica, Robalino and Villalobos (Reference Robalino and Villalobos2015) found that wages increased for workers who found park-related employment, and particularly in locations close to park entrances. However, they did not find gains for agricultural wages in the area, suggesting that protection-based economies did not lead to broader gains for workers overall. Considering the case of federal protection in the U.S. West, Rasker et al. (Reference Rasker, Gude and Delorey2013) found that economic gains were driven primarily by an increase in non-labor income in the affected counties. This is suggestive of amenity-driven growth fueled by an influx of retirees with money to spend; again, a trend that may increase local inequality. Walls et al. (Reference Walls, Lee and Ashenfarb2020) found that new National Monuments in the West drove job gains due to growth in hotels and lodging services, business services, and finance, investment and real estate services, all sectors that are likely to be capital and skills intensive.

An additional concern is that while the initial gains from tourism created by land protection may be broad, competition over time may substantially dissipate those gains or lead to consolidation that favors a few well-resourced businesses. For example, Quadri-Barba et al. (Reference Quadri-Barba, Sims and Millard-Ball2021) found that cultural heritage sites in Mexico may have decreased local poverty initially but not in the longer term. Khanal (Reference Khanal2011) found that inequality across income groups increased among forest users after community forestry was implemented in 30 community forests in Nepal. Tumusiime and Sjaastad (Reference Tumusiime and Sjaastad2014) found that in Uganda, overall benefits from a national park were not only positive but also increased local economic inequality because the main economic gains were not widely distributed.

Although there are substantial concerns that land protection may reinforce existing inequalities of capital or skill, this does not necessarily have to be the case, and indeed, some research also suggests that land protection has the potential to reduce existing inequalities. In Nepal, den Braber et al. (Reference den Braber, Evans and Oldekop2018) found that compared to similar matched locations, conservation areas established earlier in time may have reduced inequality (although later ones did not). Phan et al. (Reference Phan, Brouwer, Hoang and Davidson2018) found significant reductions in income inequality due to PES for forests in Vietnam. Additional future work is needed in this area, particularly to understand the conditions under which economic opportunities created by land protection can support equitable distribution of the gains.

In addition to privileging development that requires access to capital or skills, land protection may amplify existing inequalities driven by social hierarchies, particularly by reinforcing patterns of spatial sorting and economic segregation driven by property wealth or historically discriminatory processes. Substantial literature from the U.S. establishes that land protection policies change the values of nearby land, both by creating supply constraints and by boosting amenity values (Wu and Plantinga Reference Wu and Plantinga2003; McConnell and Walls Reference McConnell and Walls2005; Wu and Cho Reference Wu and Cho2007; Anderson and West Reference Anderson and West2006; Irwin et al. Reference Irwin, Jeanty and Partridge2014; Zipp et al. Reference Zipp, Lewis and Provencher2017). For example, Heintzelman (Reference Heintzelman2010) and Lang (Reference Lang2018) both showed that the approval of dedicated open space funding by local voters substantially raised property values in subsequent years. The potential distributional impacts of these gains in property value depend on existing patterns of ownership as well as how property tax burdens or land acquisition patterns change in response to higher values. Higher values created by land protection are likely to reinforce the wealth of those who already own property, while potentially displacing renters or lower income households who cannot afford to pay increased annual tax bills or who fall into debt and need to sell their land. Kalinin et al. (Reference Kalinin, Sims, Meyer and Thompson2023) find that changes in land protection across the New England region do not have substantial impacts on municipal level tax rates overall, but may have raised taxes in lower income municipalities, highlighting the potential for unequal impacts on local tax burdens. Lang et al. (Reference Lang, VanCeylon and Ando2023) analyzed the distribution of capitalized benefits in home values from land protection in Massachusetts and found disproportionate benefits for wealthier and white households, again consistent with problematic reinforcement of existing inequalities.

Changes in land values due to policy changes are also likely to lead to sorting patterns that may reinforce inequality and social segregation. Researchers have previously documented substantial sorting patterns based on proximity to environmental harms as one of the crucial mechanisms underpinning environmental injustices (e.g. Pastor et al. Reference Pastor, Sadd and Hipp2001; Banzhaf et al. Reference Banzhaf, Ma and Timmins2019; Melstrom and Mohammadi Reference Melstrom and Mohammadi2022). Globally, payments for ecosystem services programs or restoration initiatives may raise the value of eligible lands, creating new incentives to acquire those lands (McAfee Reference McAfee2012), while protected areas may raise the value of nearby lands for eco-tourism businesses (Green and Adams Reference Green and Adams2015). These situations may similarly result in displacement of long-standing community members. Concerns about displacement due to land protection, particularly of lower-income households, renters, or the landless poor, have been raised in literatures on “green gentrification” (e.g. Anguelovski et al. Reference Anguelovski, Connolly, Pearsall, Shokry, Checker, Maantay, Gould, Lewis, Maroko and Roberts2019; Rigolon and Németh Reference Rigolon and Németh2020; Black and Richards Reference Black and Richards2020) and “land grabbing” (e.g. Fairhead et al. Reference Fairhead, Leach and Scoones2012; Holmes Reference Holmes2014).

However, only a limited number of economic studies have examined whether land protection policies specifically have resulted in spatial sorting. A study by Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Lewis and Weber2016) found that the U.S. Northwest Forest plan led to overall positive long-term growth in median incomes for small communities due to the positive amenity effects of the protection. Subsequently though, Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Lewis and Weber2021) showed that these recreation-based amenities created spatial inequality by differentially attracting higher skilled workers to the amenity-rich localities. There is clearly scope for additional empirical economics research to help further understand the magnitudes and dimensions of equity concerns related to capitalization and sorting, both in urban and rural contexts.

Patterns of access to benefits that reflect and reinforce social disparities

Finally, a third equity concern is that patterns of land protection may create unequal access to the benefits of nature because they mirror overall patterns of social inequality. The focus on environmental justice within economics has frequently been centred around environmental harms (e.g. Banzhaf et al. Reference Banzhaf, Ma and Timmins2019). However, environmental justice requires not just reductions in harm, but support for the conditions that enable thriving, healthy communities, including access to ecosystem services and open space (e.g. Benner and Pastor Reference Benner and Pastor2015; Askew and Walls Reference Askew and Walls2019; Lado Reference Lado2019; Schell et al. Reference Schell, Dyson, Fuentes, Des Roches, Harris, Miller, Woelfle-Erskine and Lambert2020). Indeed, access to parks and open space are issues that have been raised from the beginning by environmental justice scholars and have also been part of local organizing efforts within disadvantaged communities for decades (e.g. Taylor Reference Taylor2000; Agyeman et al. Reference Agyeman, Bullard and Evans2003). Access to open space is often a concern in heavily developed urban areas, but can also be surprisingly difficult in more rural areas, particularly where private lands that were historically used by local communities are developed or posted by new private owners to prohibit public access.

There is a growing body of evidence that documents how patterns of land protection tend to reflect and reinforce underlying patterns of structural inequality, with these disparities driven by mechanisms including underlying historic racist practices, the targeting of cheap land for protection (which tends to be far from population centres), funding criteria such as the requirement of matching contributions, or ongoing outright discrimination. Prior work demonstrates that lower income neighborhoods in the U.S. have less access to open space, as parks are fewer in number, smaller, and have fewer amenities (e.g. Jennings et al Reference Jennings, Johnson Gaither and Gragg2012; Trust for Public Land 2020; Chapman et al. Reference Chapman, Foderaro, Hwang, Lee, Muqueeth, Sargent and Shane2021). In the New England region, Sims et al. (Reference Sims, Lee, Estrella-Luna, Lurie and Thompson2022) found substantial disparities in access to nearby protected open space at the census tract level: communities with the lowest income or the highest proportions of people of color defined by quartiles had just half as much nearby protected land as those in the opposite quartiles. An analysis of 37 cities across the US by Locke et al. (Reference Locke, Hall, Grove, Pickett, Ogden, Aoki, Boone and O’Neil-Dunne2021) showed that current patterns of urban tree canopy were linked to residential segregation patterns determined by historical redlining, with substantially less investment in trees for communities of color. A report by Rowland-Shea et al. (Reference Rowland-Shea, Doshi, Edberg and Fanger2020) found that the highest rates of loss of natural areas in recent decades in the U.S. coincided with communities that were lower income or had higher proportions of people of color, illustrating disparities in loss of existing open space. Despite this growing evidence of disparities in access to ecosystem benefits, there are still substantial gaps in understanding of these disparities at the national and global level and differences across regions and contexts.

Prior work has also highlighted the importance of social hierarchies and structures in determining the distribution of benefits from land protection within communities. Even land protection mechanisms such as payments for ecosystem services or community-based forest management that are intentionally designed to be pro-community may reinforce existing social structures in ways that can disempower marginalized community members. For example, Agarwal (Reference Agarwal2009) examines how community-based forest use rules may be related to the number of women on governance committees and discusses the complex intersectionality of gender and social status in rule-making and enforcement. Bardhan and Dayton-Johnson (Reference Bardhan, Dayton-Johnson, Ostrom, Dietz, Dolsak, Stern, Stonich and Weber2002) also document how heterogeneity in wealth and social status frequently affect outcomes for cooperative irrigation systems. Alix-Garcia et al. (Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims and Yañez-Pagans2015) found that gains in household assets attributable to Mexico’s PES program went primarily to full-rights members of agrarian reform communities, a legacy of the one-to-one inheritance structures in that context. At the same time, Bocci and Mishra (Reference Bocci and Mishra2021) find that participation in community forest management in Guatemala effectively empowered previously disadvantaged women by increasing their household bargaining power. Sills and Jones (Reference Sills, Jones, Dasgupta, Pattanayak and Smith2018) emphasize the role of institutions in the success of land protection efforts, noting that the details of how policies are implemented and by who may generate substantial heterogeneity in outcomes. Again, there is considerable scope for additional research that seeks to understand how the benefits of land protection policies are distributed and how these patterns intersect with existing structural inequalities across and within communities.

Moving towards greater equity in land protection

As outlined above, there are clearly reasons to be concerned about how land protection may result in outcomes that privilege the already privileged. At the same time, there are several potential ways to move forward by ensuring that policies and practices more actively seek to promote equitable outcomes. In particular, I identify four possible avenues for change (Figure 2): specific mechanisms that link land protection to local economic gains, careful zoning and timing, prioritization that explicitly includes equity goals, and taking direction from local communities.

Specific mechanisms that link land protection to local economic gains

In many cases, gains from land protection are possible but are unlikely to materialize unless there are concrete, intentionally designed governance and benefit sharing mechanisms that ensure a link between land protection and local livelihoods. These may include rules and institutional structures for local revenue sharing, local hiring, support for local infrastructure, compensation for wildlife-induced damages, or support for new small businesses.

Across the globe, many protected area systems do require some return of park revenues to local communities (Adams and Infield Reference Adams and Infield2003; Snyman and Bricker Reference Snyman and Bricker2019). In Nepal, for instance, conservation area management committees with representation from an array of stakeholders have historically governed the distribution of funds based on park entrance fees, and may retain 100% in some conservation areas and 30–50% in buffer zones (Heinen and Shrestha Reference Heinen and Shrestha2006; Thakali et al. Reference Thakali, Peniston, Basnet and Shrestha2018). These funds are to be used for community development, such as improving drinking water, education, roads, or sanitation. Similarly, in Costa Rica, local advisory boards for parks can work to promote local benefits, including local hiring. As documented by Basurto and Jiménez-Pérez (Reference Basurto and Jiménez-Pérez2013), these local hires often became crucial park guards, naturalists, and firefighters. US Federal agencies also prioritize local hires in some areas (e.g. state residents are sought by the National Park Service for jobs in Alaska).Footnote 1 Multiple U.S. federal agencies also maintain roads, bridges, culverts, public restrooms, and other infrastructure that support recreation economies,Footnote 2 as do other parks agencies globally. Seeking to foster more representative leadership, the NPS also supports employee resource groups that celebrate a diverse set of identities and values, can advise NPS leadership, and develop a future set of leaders (National Park Service 2022). Several government agencies or programs globally provide compensation for crop or livestock damages that occur due to conservation-induced human–wildlife conflicts (e.g. Ravenelle and Nyhus Reference Ravenelle and Nyhus2017). Others provide payments in lieu of property taxes (“PILOT” payments) when land is acquired by state, provincial, or federal owners. Although often underfunded, these payments are designed to compensate for the potential lost local tax revenue when land is owned publicly rather than privately (Kenyon and Langley Reference Kenyon and Langley2010; Hall Reference Hall2013). Incentive-based land protection programs such as payments for ecosystem services have promised a direct link between conservation and tangible local benefits. For example, communities enrolled in Mexico’s federal PES program used funds for maintaining schools, communal meeting spaces, and for the purchase of communal vehicles for patrolling and other collective needs, in addition to for land management (Alix-Garcia et al. Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims, Orozco-Olvera, Costica, Fernández Medina and Romo Monroy2018). Peru’s PES program provided funds to communities for starting businesses to provide alternate livelihoods to timber extraction (Börner et al. Reference Börner, Wunder and Giudice2016), although as previously mentioned, concerns have been raised about the appropriateness of the match between allowed uses and true local needs (e.g. Ravikumar et al. Reference Ravikumar, Uriarte, Lizano, Farré and Montero2023).

Some conservation efforts may be well linked to local communities not because they seek to provide new revenue streams or jumpstart new business, but because they preserve the continuance of existing local livelihoods. For example, in Grand Lake Stream, Maine, public and private partners protected formerly private timberlands that had historically allowed public access through a combination of purchases and easements. These agreements facilitated continued access to lands that directly supported existing local businesses for guiding, hunting, and fishing (Highstead Foundation 2019). The lands also provide an allowance of up to four cords of hardwood for every household, which is enough to cover a winter’s worth of heating for many families, providing a direct and valuable local benefit of the protection.

At this point in time, many agencies and conservation organizations have decades of experience seeking to directly link land protection and livelihoods – a key tenet of the integrated conservation and development project literature (McShane and Wells Reference McShane and Wells2004). Yet the still frequent lack of direct, appropriate, and sustained links to local livelihoods has been identified as one of the key reasons for failure of many conservation projects (Blom et al. Reference Blom, Sunderland and Murdiyarso2010). Continuing research on benefit sharing mechanisms may strengthen the case for more substantial and longer-term funding streams as well as identify the most locally appropriate processes. In addition, new research is needed to understand how increased information access and globalization are changing the opportunities and challenges of linking land conservation to local development.

Careful zoning and timing

A second key theme that has emerged across different places and cases is that zoning and timing matter for the success of land protection. Flexibility in zoning means seeking to creating a spatial balance between areas with strict prohibitions and those that allow for sustainable harvests, limited extraction or managed development. Economists have demonstrated that multiple possible uses of land mean that optimal management strategies require spatial planning (e.g. Albers and Grinspoon Reference Albers and Grinspoon1997; Albers and Robinson Reference Albers and Robinson2007). Albers and Robinson (Reference Albers and Robinson2007) demonstrate how a combination of a strictly protected inner core area and a buffer zone forming a ring around that area leads to the highest level of net benefits in a protected area situation where surrounding communities rely on forest extraction. Indeed, multiple use, defined as a mandate to ensure that public lands allow uses and development of land resources that meet the needs of multiple people, is a founding concept of public lands in the U.S. (Pressey et al. Reference Pressey, Visconti and Ferraro2015). The balancing of multiple needs has been applied globally as well, particularly in work to develop biosphere reserves, which are intentionally zoned to accommodate a mix of core areas with strict protection, areas that allow for tourism and recreation, and areas that allow for human settlements and sustainable use (Brunckhorst Reference Brunckhorst2001), and through other landscape approaches to conservation (Sayer et al. Reference Sayer, Sunderland, Ghazoul, Pfund, Sheil, Meijaard, Venter, Boedhihartono, Day and Garcia2013).

Several empirical analyses have found support for the idea that differentiated zoning may be important to ensuring local gains from land protection. Blackman (Reference Blackman2015) found that the Maya Biosphere reserve in Guatemala generated more avoided deforestation in the multiple-use zone than in the strictly protected areas, while Bocci et al. (Reference Bocci, Fortmann, Sohngen and Milian2018) found that limited forest concessions were a key mechanism for livelihood support. Ferraro et al. (Reference Ferraro, Hanauer, Miteva, Canavire-Bacarreza, Pattanayak and Sims2013) found that strictly protected areas are not necessarily the most effective at protecting forests because governments may simply avoid designating them in high-risk areas in order to avoid social conflict, while Sims and Alix-Garcia (Reference Sims and Alix-Garcia2017) found that biosphere reserves in Mexico were the type of protected area most able to achieve avoided deforestation while maintaining local livelihoods. The prevalence of buffer zones supporting community-use and control around most conservation areas in Nepal may be part of the reason why protected areas there have contributed to meaningful poverty reduction (den Braber et al. Reference den Braber, Evans and Oldekop2018).

It is important to recognize, however, that while spatial zoning may be beneficial in balancing multiple needs and priorities, it is also a tool that has been used in exclusionary ways to control or subjugate populations, particularly those with traditional but not formal land rights or with contested claims. Vandergeest (Reference Vandergeest1996, Reference Vandergeest2003) argues that the process of defining and mapping forest zones in Thailand was a key basis for controlling and racializing ethnic minorities by the Thai government. Krakoff (Reference Krakoff2018) argues that U.S. conservation designations served to dispossess Native Americans of key territories and that ongoing processes of protected area designation could continue to undermine Native American sovereignty. García and Baltodano (Reference García and Baltodano2005) highlight longstanding conflicts over public access to beaches in California and the exclusionary control of access points and amenities as a problematic example of spatial management.

In addition to careful attention to the spatial management aspects of land protection, a focus on the timing of protection initiatives has emerged as one way to mitigate potential displacement or gentrification impacts. In cases where land protection initiatives are expected to increase land or property values, conservation actors have a chance to anticipate these potential impacts and ensure that safeguards are in place prior to protection. Clarifying land rights and tenure security can allow local communities to participate in programs such as PES and may reduce the risk of land grabbing (Chhatre et al. Reference Chhatre, Lakhanpal, Larson, Nelson, Ojha and Rao2012). In Mexico, for example, most communities had already been through a process of formal land titling and recognition (PROCEDE) prior to the establishment of federal PES programs. In contrast, PES has not been a viable option in many countries because of the lack of formal land rights for communities, despite these communities having demonstrated long-standing effective stewardship of natural resources.

Timing is also crucially important for efforts to support access to affordable housing near protected land where this is a concern. If property values are expected to rise as a result of new or improved parks, efforts to support access to affordable housing have the best chance to succeed if planned early and with coordination between organizations or government agencies (Rigolon et al. Reference Rigolon, Keith, Harris, Mullenbach, Larson and Rushing2020). Community organizations supporting affordable housing are likely to have more opportunities for purchases of property or for passage of inclusionary zoning proposals before prices rise. Yet these will only be possible if there is early outreach and dialog between organizations promoting affordable housing and land protection – or if more organizations adopt dual missions seeking to achieve both goals. Community land trusts have emerged as one possible structure to reduce gentrification through resale restrictions and asset ownership that is controlled through local governance (e.g. Moore and McKee Reference Moore and McKee2012; Choi et al. Reference Choi, Van Zandt and Matarrita-Cascante2018; Veronesi et al. Reference Veronesi, Algoed and Hernández Torrales2022). Economists have opportunities to engage with and contribute to the empirical research on these emerging partnerships.

Explicit prioritization of equity goals in land protection initiatives

To date, most land protection efforts have been driven by and focused on ecological priorities (e.g. Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Clark and Sheldon2014; Wilson Reference Wilson2016; Pimm et al. Reference Pimm, Jenkins and Li2018). Although there has been substantial concern and attention paid to how land protection affects communities, these issues are still often framed as secondary to the core purpose of conservation. Yet if access to the benefits of nature is viewed as a necessary condition for thriving human communities, then from an equity perspective, land protection planning and prioritization efforts should explicitly seek to provide equal access both in terms of outcomes and underlying processes (Agyeman et al. Reference Agyeman, Bullard and Evans2003; Estrella-Luna Reference Estrella-Luna2010; Askew and Walls Reference Askew and Walls2019; Lado Reference Lado2019; Ruano-Chamorro et al. Reference Ruano-Chamorro, Gurney and Cinner2022).

Although the incorporation of equity goals has been understudied in the conservation prioritization literature, many public conservation funding opportunities do in fact already explicitly prioritize disadvantaged communities. In Mexico, the National Forestry Commission (CONAFOR) gives additional weight to PES applications from areas with a high proportion of economically marginalized people and from indigenous communities (Sims et al. Reference Sims, Alix-Garcia, Shapiro-Garza, Fine, Radeloff, Aronson, Castillo, Ramirez-Reyes and Yañez-Pagans2014; Alix-Garcia et al. Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims and Yañez-Pagans2015). These rules are the result of a process intentionally designed to give voice to multiple stakeholders through annual review by a council including representatives from government agencies and civil society (Sims et al. Reference Sims, Alix-Garcia, Shapiro-Garza, Fine, Radeloff, Aronson, Castillo, Ramirez-Reyes and Yañez-Pagans2014). In the U.S., individual states may give extra weight to applications for Land and Water Conservation Fund dollars that improve access for environmental justice populations.Footnote 3 States may also establish their own program goals, such as New Mexico’s focus on providing outdoor recreation opportunities to a more diverse population through its “Outdoor Equity Grant Program” (Askew and Walls Reference Askew and Walls2019). Federal policy shifts towards greater prioritization of equity goals in land conservation in the U.S. are also growing. The Biden-Harris Administration’s “America the Beautiful” initiative explicitly lists collaborative and inclusive processes and conservation “for the benefit of all people” as primary goals (U.S. Department of the Interior 2022). In parallel, the “Justice 40” is an effort to ensure that at least 40% of the overall benefits from Federal investments including in infrastructure, climate, clean energy, agriculture, and conservation are delivered to disadvantaged communities (Young et al. Reference Young, Mallory and McCarthy2021; U.S. Department of Agriculture 2022). International calls for area-based conservation are also increasingly incorporating ideas of justice and equity (Zafra-Calvo et al. Reference Zafra-Calvo, Garmendia, Pascual, Palomo, Gross-Camp, Brockington, Cortes-Vazquez, Coolsaet and Burgess2019; Maxwell et al. Reference Maxwell, Cazalis, Dudley, Hoffmann, Rodrigues, Stolton, Visconti, Woodley, Kingston and Lewis2020; Ruano-Chamorro et al. Reference Ruano-Chamorro, Gurney and Cinner2022). In addition, there is growing awareness of and information about both local and global environmental justice struggles generally (Temper et al. Reference Temper, Del Bene and Martinez-Alier2015; White House Council on Environmental Quality 2022).

Future research can play an important role in providing information that can help to assess current disparities in the distribution of benefits or that can be used to develop screening tools to identify conservation opportunities (e.g. Sims et al. Reference Sims, Lee, Estrella-Luna, Lurie and Thompson2022). Research can also illuminate how the explicit inclusion of social justice as a goal of land protection is likely to shift conservation priorities, processes, and outcomes. Economists in particular may play an important role in continuing to assess the potential relationships between conservation and livelihood goals (e.g. Ferraro et al. Reference Ferraro, Hanauer and Sims2011; Alix-Garcia et al. Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims and Yañez-Pagans2015; Hajjar et al. Reference Hajjar, Oldekop, Cronkleton, Newton, Russell and Zhou2021; Meyer and Börner Reference Meyer and Börner2022) and among valuable environmental benefits or services (Newbold and Siikamäki Reference Newbold, Siikamäki, Halvorsen and Layton2015; Keeler et al. Reference Keeler, Dalzell, Gourevitch, Hawthorne, Johnson and Noe2019).

Prior research has demonstrated both opportunities for win–win scenarios when social goals are emphasized, as well as the reality of true tradeoffs driven by the current distributions of social disadvantage versus ecological benefits. For example, in the context of PES, prior work has demonstrated real difficulties in achieving both poverty alleviation and ecologically effective program targeting when land at the highest risk of loss is also owned by wealthier households (e.g. Zilberman et al. Reference Zilberman, Lipper and McCarthy2008; Alix-Garcia et al. Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims and Yañez-Pagans2015). Yet this work has also identified opportunities, such as targeting PES to communal landholders and specific geographic regions which have both high rates of loss and high social marginalization (Alix-Garcia et al. Reference Alix-Garcia, Sims and Yañez-Pagans2015). Potential synergies and tradeoffs can also be identified for targeting new protected areas (e.g. Ferraro et al. Reference Ferraro, Hanauer and Sims2011). In the context of New England, Sims et al. (Reference Sims, Lee, Estrella-Luna, Lurie and Thompson2022) demonstrated substantial differences in the rankings of undeveloped and unprotected lands according to their proximity to communities with high proportions of people of color versus traditional ecological prioritization criteria. While clear tradeoffs emerged between prioritizing access for diverse populations and ecological resilience, there were potential synergies with protecting land of high value for clean drinking water. Economists can play an important role in outlining these types of tradeoffs or synergies. They can also seek to incorporate equity as a standard part of analyses of conservation prioritization and spending programs, which have often been focused on efficiency or cost-effectiveness criteria. They can present information on equity dimensions along with standard measures of benefits and costs, can be explicit about how the choice of a numéraire good in benefit–cost analysis may affect the ranking of policy choices, or can incorporate different sets of distributional weights in these analyses (Hammitt Reference Hammitt2021).

Researchers may also contribute to understanding the institutional structures that can be effective in prioritizing equity as part of conservation. Environmental justice researchers strongly emphasize the importance of more equitable processes in efforts to redress disparities (Lado Reference Lado2019; Estrella-Luna Reference Estrella-Luna2010; Askew and Walls Reference Askew and Walls2019; Ruano-Chamorro et al. Reference Ruano-Chamorro, Gurney and Cinner2022; Keller et al. Reference Keller, Harrison and Lang2022). Some of the potential changes to process that may matter are advisory groups of stakeholders, increased resource sharing by NGOs and land trusts with less well-endowed organizations, integrating diversity, equity and inclusion goals into strategic plans of conservation agencies and organizations, lowering requirements for matching funds from municipalities, assistance to localities from regional planning authorities, and improved spatial mapping tools. These potential changes to process deserve support for implementation by economists where we can contribute, as well as additional systematic study.

Taking direction from and empowering communities

Each of the above ways to potentially improve equity in land protection rests on the implicit assumption that these changes could shift policies towards outcomes and processes that benefit historically marginalized or disadvantaged populations. Yet to know what is truly benefitting people also ultimately requires opportunities to take direction from and empower these communities directly.

Engagement and listening are a first step towards understanding and redressing disparate access to the benefits of ecosystem services. Prior work illustrates that even when there is legal access to open space, marginalized populations may be excluded by experiences of racism, limited access points, congestion, or lack of transportation and leisure time (Taylor Reference Taylor2000; García and Baltodano Reference García and Baltodano2005; Roberts and Rodriguez Reference Roberts and Rodriguez2008; Erickson et al. Reference Erickson, Johnson and Kivel2009; Sister et al Reference Sister, Wolch and Wilson2010; Finney Reference Finney2014; Rodriguez-Gonzalez Reference Rodriguez-Gonzalez2021). Better understanding of these barriers can lead to ways in which land-oriented organizations can change missions, form partnerships, or provide programming that better communicates with and involves historically excluded groups to create more inclusive access (e.g. Sister et al. Reference Sister, Wolch and Wilson2010; Flores and Khun Reference Flores and Kuhn2018; Rigolon Reference Rigolon2019).

As many scholars and activists have emphasized, efforts to redress structural inequality and structural racism need to move from processes that ignore or simply inform communities to processes that collaborate with and defer to those communities (Martinez-Alier Reference Martinez-Alier, Anguelovski, Bond, Del Bene and Demaria2014; Gonzales Reference Gonzales2018; Rigolon Reference Rigolon2019; Rigolon et al. Reference Rigolon, Keith, Harris, Mullenbach, Larson and Rushing2020, Reference Rigolon, Yañez, Aboelata and Bennett2022). In some settings, community land trusts, for example, offer one possibility through collective ownership structures, as long as their governance remains truly inclusive (DeFilippis et al. Reference DeFilippis, Stromberg and Williams2018). Similarly, increased devolution of control to already collectively managed common lands globally may be an important strategy for future land protection (Erbaugh et al. Reference Erbaugh, Pradhan, Adams, Oldekop, Agrawal, Brockington, Pritchard and Chhatre2020). Rigolon (Reference Rigolon2019) and Rigolon et al. (Reference Rigolon, Keith, Harris, Mullenbach, Larson and Rushing2020, Reference Rigolon, Yañez, Aboelata and Bennett2022) emphasize the importance of both procedural and interactional justice in park management: ensuring that planning processes are deliberately seeking inclusive feedback, that leadership staff and on the ground employees of parks reflect the ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic diversity of surrounding communities, and that community outreach and in-park recreation programs welcome and engage all community members, including long-time residents. Still, a key challenge moving forward is that communities – whether within the U.S. or globally– are not homogenous units but are themselves complex systems with internal dynamics and differences (e.g. Agrawal and Gibson Reference Agrawal and Gibson1999; Agarwal Reference Agarwal2009; Tyagi and Das Reference Tyagi and Das2017; Estifanos et al. Reference Estifanos, Polyakov, Pandit, Hailu and Burton2020a).

Researchers can also do more to engage respectfully and thoughtfully, including through community-centred practices such as early listening sessions, groundwork, network mapping to understand context, presenting research goals transparently, and using reflexive approaches (Humphreys et al. Reference Humphreys, Lewis, Sender and Won2021; Rodríguez-González and Torres-Garrido Reference Rodríguez-González and Torres-Garrido2022; Rodríguez-González Reference Rodríguez-González2022). One challenge is that efforts to include marginalized voices must be balanced with the high burdens already faced by people in disadvantaged communities. Researchers can seek to ensure fair compensation for time devoted to these processes and that work products are returned to the community. In addition, the study of conservation itself can shift towards a more inclusive practice by changing the nature of the questions asked, who is doing the research, and the types of research that are valued (Cronin et al. Reference Cronin, Alonzo, Adamczak, Baker, Beltran, Borker, Favilla, Gatins, Goetz and Hack2021; Rudd et al. Reference Rudd, Allred, Bright Ross, Hare, Nkomo, Shanker, Allen, Biggs, Dickman and Dunaway2021).

Conclusion

The maintenance of ecosystem services provided by lands in forests, wetlands, riparian corridors, grasslands, sustainable agricultural systems, urban parks, and other open spaces is a core societal goal. Land protection policies ranging in size and scope are crucial to ensure the future viability of ecosystem services. These policies generate both concerns and possibilities for greater social equity by changing the rents for different land uses and creating new winners and losers. Concerns about equity stem from situations where these changes reinforce disadvantages: by burdening local communities with the costs of land protection; by reinforcing underlying inequality in capital, skills, or social status; or by deepening inequalities in access to the benefits of nature. This article has sought to provide evidence for each of these concerns and to propose concrete steps for change as new land protection policies are developed. Each of the issues and potential avenues for change that have been identified is also worthy of considerable additional investigation and future research by environmental and resource economists.

Each of the equity concerns identified here unfortunately shares roots in the fundamentally unequal distribution of income, wealth, and social power that haunts our present global society. Economists also have a clear role to play in analyzing and informing the redress of these broader structural inequalities. In addition, although economists have traditionally been more focused on outcomes than processes, equity concerns demand increasing attention to the processes of decision-making and power – including processes about which topics are studied and by whom. Although I have sought to identify some possible avenues for future research based on a broad review of the literature, additional concerns and proposals for change are likely to be identified by future outreach and listening to communities most directly engaged in and impacted by land protection.

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

This paper was developed as a keynote address for the workshop: “Ecosystem Services Foundations for Resilient Communities: Agriculture, Land Use, Coasts, and Energy for Human Well-Being,” June, 2022 in Mystic, CT. Thank you to two anonymous referees, the workshop organizers and participants for useful comments and suggestions and to the workshop funders: the USDA National Institute for Food and Agriculture and the USDA Economic Research Service. This work was also supported by USDA-NIFA Grant No. #2021-67023-34491 and Amherst College.

Funding statement

This paper was supported by workshop funding from the USDA National Institute for Food and Agriculture and the USDA Economic Research Service. This work was also supported by USDA-NIFA Grant No. #2021-67023-34491 and Amherst College.

Competing interests

The author declares that there are no competing interests.