Introduction: “I am Hồ Chí Minh”

One day in late January 1950, an old man accompanied by a group of young guards appeared at Vietnam’s border with China. “I am Hồ Chí Minh,” he told the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) soldiers who stopped him, in fluent Chinese. He was the Vietnamese communist leader, he said, and he had come to China to confer with his old friends Chairman Mao Zedong and Premier Zhou Enlai in Beijing.

Mao was then in Moscow for meetings with Stalin. Liu Shaoqi, the second-in-command of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), acted in Mao’s stead during the Chairman’s absence. Liu knew that a high-ranking Vietnamese communist delegation would be visiting China, as the Chinese and Vietnamese parties had exchanged telegrams after a letter, written in August 1949 by Hồ Chí Minh to Mao requesting Chinese aid in all forms, was delivered to the CCP leadership by two high-ranking cadres from the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP).Footnote 1 But Liu did not know that Hồ Chí Minh himself would come to China. He immediately instructed that Hồ be “warmly welcomed” at the border and “secretly escorted” to Beijing.Footnote 2

Liu’s was a natural response. Hồ Chí Minh was an old friend and comrade of many CCP leaders. He had worked with Zhou Enlai and Zhu De as early as the 1920s in Paris. Thereafter he met Mao in Guangzhou. He and other Vietnamese communists had since accumulated extensive connections with the Chinese communists. Upon receiving Hồ’s August 1949 letter, CCP leaders made two decisions: first, to invite a high-ranking Vietnamese delegation to Beijing to “discuss all important issues,” and second, to dispatch to Vietnam Luo Guibo, a PLA commander with extensive guerrilla war experience during China’s war of resistance against Japan.Footnote 3 Luo departed Beijing for Vietnam on January 16 as the CCP’s liaison representative to the ICP. On January 18, a few days before Hồ Chí Minh arrived at the Chinese border, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) formally recognized Hồ Chí Minh’s Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN) – the first country in the world to do so. Hồ Chí Minh had arrived in China at an opportune moment.

Planning Support for the Vietnamese Communists

Hồ Chí Minh arrived in Beijing on January 30. Liu met with him the same evening. Hồ Chí Minh told Liu that he had “walked barefoot for seventeen days before setting foot on Chinese soil,” and reiterated that he had come to Beijing to seek extensive Chinese support. Liu cabled Mao with Hồ Chí Minh’s requests, suggesting that the CCP should “satisfy all of them.” Mao agreed completely.Footnote 4 Hồ said that he also would like to meet with Stalin and Mao in Moscow and obtain military, political, and economic assistance from the Soviets too. Mao immediately telephoned Stalin to convey Hồ Chí Minh’s request. Stalin replied that Hồ Chí Minh could pay a secret visit to Moscow.Footnote 5 Hồ Chí Minh left Beijing by train on the evening of February 3 and arrived in Moscow one week later.

Hồ Chí Minh’s reception in Moscow was lukewarm. Stalin’s attitude toward him was skeptical. The Soviet leader agreed to recognize Hồ Chí Minh’s government. But, as his primary concerns lay in Europe and he was unfamiliar with – even suspicious of – Hồ Chí Minh’s intentions, and also doubtful about the DRVN’s capabilities, Stalin directed Hồ Chí Minh’s request for support to the Chinese. To Hồ Chí Minh’s great satisfaction, Mao and Zhou promised, first in Moscow and then in Beijing (Hồ had accompanied the two on their train ride back to China from Moscow), that the CCP would do its best “to offer all the assistance needed by Vietnam in its struggle against France.” This included military aid for the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN), as the DRVN military forces were now officially called.Footnote 6

The CCP leaders’ enthusiastic response to Hồ Chí Minh’s request for support reflected their belief that it was their mission as communists to promote an Asian revolution modeled on China’s. It was also the result of a “division of labor” agreement that Liu reached with Stalin during his secret visit to the Soviet Union in late June through early August 1949, according to which the Chinese should take a larger role in promoting revolutionary movements in East Asia. Furthermore, it revealed the CCP leaders’ belief that standing by their Vietnamese comrades would serve their goal of safeguarding China’s national security interests. In 1949–50, Mao and the CCP leadership were particularly concerned about the prospect of a possible military confrontation with imperialist countries and their acolytes in the Korean peninsula, Indochina, and the Taiwan Strait.Footnote 7 In the case of Vietnam, this view was supported by the fact that some Chinese nationalist units still loyal to Jiang Jieshi had fled to the Chinese-Vietnamese border area, making the area a source of insecurity for the fledgling Chinese communist regime.Footnote 8

When Hồ Chí Minh came to China in late January, Luo had already left for Vietnam. He arrived at the DRVN headquarters in Vietnam’s Northern Highlands in early February. With Luo’s onsite assistance, in April 1950, the ICP Central Committee asked the CCP to send more military advisors to serve at PAVN headquarters and commands at different levels, and to provide the DRVN with substantial materiel and other support. On April 17, the CCP Central Committee decided to honor the request, and to form a “Chinese Military Advisory Group” (CMAG) to render the support to the DRVN.Footnote 9

On June 25, 1950, the Korean War broke out. CCP leaders now saw the task of supporting their Vietnamese comrades as even more urgent. Two days later, Mao, Liu, and other top CCP leaders met with the Chinese military advisors who were to work in Vietnam. It was China’s “glorious internationalist duty” to support the Vietnamese revolution, CCP leaders emphasized. Mao assigned the advisors two specific tasks: to help the Vietnamese comrades establish a formal army, and to aid them in the planning and execution of major operations to defeat the French colonists. Liu stressed that Vietnam was an important area for China, that sending Chinese military advisors there would have worldwide significance. If the enemy were allowed to stay in Vietnam, he warned, China would also face a difficult situation.Footnote 10

Late in July, the CMAG, composed of seventy-nine experienced PLA commanders, was formally established. Wei Guoqing, a PLA army corps commander, commanded the group, and Mei Jiasheng and Deng Yifan, both PLA army-level commanders, served as deputy heads. Wei and other members of the group arrived in Vietnam in August, and immediately set to work alongside the PAVN forces.Footnote 11

The Border Campaign

When Hồ Chí Minh and Liu met in Beijing in early February, they discussed the idea of PAVN troops launching a campaign along Vietnam’s border, to link the DRVN’s base areas with China’s Yunnan and Guangxi provinces. In May 1950, the CCP leadership decided to send General Chen Geng, a CCP Central Committee member and one of the most talented high-ranking PLA commanders, to Vietnam to help organize the campaign. CCP leaders also agreed to help train PAVN troops in Yunnan in preparation for the border campaign.Footnote 12 Luo arranged for General Võ Nguyên Giáp to meet with Chen in Yunnan (where Chen’s units were stationed) to brief him on the situation in Vietnam.Footnote 13

A CCP Central Committee instruction to Chen, drafted by Liu, outlined his main tasks in Vietnam:

Your primary task, in addition to discussing and resolving some specific issues with the Vietnamese comrades, is to work out a practical, general plan according to conditions in Vietnam … regarding the scope of our assistance (especially the conditions for shipping supplies). We will use this plan as a guide to implement various aid programs, including making a priority list of materials to be shipped, training (Vietnamese) cadres, training and rectifying (Vietnamese) troops, expanding recruitment, organizing logistical work and fighting battles. The plan should … be approved by the Vietnamese Party Central Committee.Footnote 14

Chen traveled to the DRVN’s bases in northern Vietnam in mid-July. After meeting with Hồ Chí Minh, Giáp, and other DRVN leaders, he suggested that in launching the border campaign the PAVN should “concentrate their forces and destroy the enemy troops by separating them into isolated groups,” a principle that had proven effective for the communists in the Chinese civil war. Hồ Chí Minh and the Vietnamese accepted Chen’s plan.Footnote 15 Originally, the DRVN leadership had hoped to carry out the border campaign aimed at both Lào Cai and Cao Bằng. Due to grain supply problems, in late June, after consulting with Chinese advisors, they decided to “abandon the plan to attack Lào Cai,” and go ahead with the campaign in Cao Bằng first.Footnote 16

On July 22, Chen conveyed his plan for the campaign in a telegram to the CCP Central Military Commission (CCMC). The Vietnamese would begin by annihilating some of the enemy’s automotive units “in mobile operations” while destroying a few of the enemy’s small strongholds, so as to gain experience for larger operations and heighten their soldiers’ morale. They would then launch an offensive against Cao Bằng. Rather than attack the town head-on, they would surround it and assault the enemy’s strongholds in the surrounding area one by one, while at the same time intercepting and destroying the enemy’s reinforcements coming from Lạng Sơn. Finally, the troops would seize Cao Bằng. Chen believed that if this strategy succeeded and Cao Bằng was taken, “the balance of power between the enemy and us in northeastern and northern Vietnam would be completely changed in our favor.”Footnote 17 Four days later, the CCMC approved Chen’s plan. Experienced CMAG members were assigned to the PAVN’s battalion, regiment, and division headquarters to guarantee the proper execution of Chen’s strategy.

CCMC leaders in Beijing understood that increasing the PAVN’s combat capacity was of vital importance. From April to September, the Chinese supplied their Vietnamese comrades with more than 14,000 guns; 1,700 machine guns; about 150 pieces of different types of cannons; 2,800 tons of grain; and large amounts of ammunition, medicine, uniforms, and communication equipment.Footnote 18 Meanwhile, CCP leaders also issued orders to accelerate the completion of roads to the Vietnamese borders in Yunnan and Guangxi, while repeatedly urging party organs in these two provinces to “overcome all difficulties to guarantee the transportation to Vietnam of the grain needed by the DRVN.”Footnote 19

The border campaign began on September 16 and ended with a sweeping DRVN victory. Chen and CMAG members played a crucial role in directing the PAVN forces’ operations during each phase of the campaign. In particular, when the French dispatched five battalions of troops to attack the DRVN capital at Thái Nguyên in response to the PAVN offensive against Cao Bằng, Chen insisted upon increasing pressure on Cao Bằng.Footnote 20 By October 13, according to CCP statistics, the PAVN forces had eliminated seven French battalions – a total of nearly 3,000 troops – forcing the French to abandon their long-standing blockade line along the Vietnamese-Chinese border. The vast territory of the PRC thus became the DRVN’s strategic rear – a development that would prove highly advantageous for the Vietnamese communists. Chen left Vietnam in early November for a new assignment in Korea.

Setbacks in the Red River Delta

Having claimed victory in the border campaign, what would be the DRVN’s next move? Giáp and the PAVN military leadership, after discussing the matter with the Chinese advisors, decided to wage the next phase of the war inside the French-controlled Red River Delta. They hoped that weakening the French defensive system in the delta would further enhance the DRVN’s standing and pave the way toward a final victory in Indochina. Both Beijing and the ICP leadership endorsed the plan.Footnote 21

Meanwhile, the French strategy in Indochina had also changed significantly with General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny’s appointment as high commissioner and commander-in-chief in Indochina. After assuming his new position in Saigon, he launched a series of moves to strengthen the French position in the delta area. The DRVN’s new offensive plan was now complicated by the efforts of a determined French general.

From late December 1950 to June 1951, the PAVN command sent its best units, including the “iron division” (the 308th Division), to wage three offensive campaigns in the delta, hoping that this “general counteroffensive” would bring them closer to liberating Vietnam. However, the delta was no mountainous border area. DRVN forces were dealt heavy casualties by a robust French defense supported by superior artillery fire. By mid-1951, General Giáp was forced to call off the offensive. Chinese advisors agreed that the DRVN needed a different strategy.Footnote 22

But de Lattre would not allow his enemy to simply pivot to a new strategy. He now hoped to capitalize on the momentum gained by the French success in the delta by securing control of Hòa Bình, the key node in the DRVN’s North–South line of communication. If it succeeded, this offensive would allow the French to establish a corridor from Haiphong through Hanoi and Hòa Bình all the way to Sơn La, thus splitting the DRVN’s entire territory in two.

Giáp, Luo, and other Chinese advisors held several urgent meetings against this grim backdrop. Luo suggested that PAVN troops should not only attack Hòa Bình but also dispatch some units into French-occupied zones in the delta to conduct guerrilla operations to harass the enemy and establish bases. The DRVN leadership approved Luo’s plan and decided in late November to start an all-out effort to repel the French offensive. They would deploy four divisions to attack Hòa Bình while sending elements of two divisions behind enemy lines.Footnote 23

Giáp’s bid to dislodge the French from Hòa Bình by force did not succeed. During a three-month battle from November 1951 to February 1952, the PAVN sustained heavy losses in repeated assaults on the heavily fortified French positions. Giáp was eventually forced to withdraw. However, as Christopher Goscha has shown, the French victory at Hòa Bình turned out to be pyrrhic. After the PAVN withdrew, French commanders decided they had to abandon Hòa Bình in order to counter the stepped-up PAVN attacks in the Red River Delta. The PAVN were thus able to regain control of this key corridor, even though they had not prevailed on the battlefield. The outcome was a costly lesson for Giáp and his Chinese advisors, but one that would prove highly valuable in the long run.Footnote 24

Turning to the Northwest

In the aftermath of the heavy PAVN losses sustained in the delta and at Hòa Bình during 1951, DRVN leaders needed a new strategic approach. Luo recommended that the PAVN shift its operational focus to Vietnam’s northwestern region, adjacent to Laos. By forcing the French to fight in these mountainous districts far from Hanoi and the Red River Delta, the DRVN might expose some of the weakest links in the enemy’s military system.Footnote 25

Early in 1952, the CMAG proposed to the DRVN leadership a new operation, the northwest campaign, which the Chinese advisors believed would further consolidate the DRVN “liberated zone” in northwestern Vietnam, and form the basis for a future strategic counteroffensive.Footnote 26 On February 16, the CMAG advised the PAVN High Command to focus on guerrilla tactics and small-scale mobile wars for the duration of 1952. This would buy time for their main formations to undergo political and military training in preparation for future combat operations in the northwest.Footnote 27 That same day, Luo stated in a report to the CCMC in Beijing that PAVN troops might engage in reorganization and training for the first half of 1952 before dedicating the next six months to expelling the enemy from Sơn La, Lai Châu, and Nghĩa Lộ in northwestern Vietnam. Luo further suggested that in 1953 Vietnamese forces might treat northwestern Vietnam as a base from which to launch forays into upper Laos. Chinese leaders in Beijing promptly accepted the plan; Liu commented, “it is very important to liberate Laos.”Footnote 28 The DRVN leadership also gave their approval. In April 1952, the Politburo of the ICP, which had by then renamed itself the Vietnamese Workers Party (VWP), formally decided to initiate the northwest campaign.

Around this time, DRVN leaders inquired with Beijing through Chinese advisors whether China might send “volunteers” to Vietnam to ensure victory in this crucial campaign.Footnote 29 On July 22, the CCMC categorically rejected the request to send Chinese troops to Vietnam. In its response, the CCMC cited the long-standing principle that Chinese troops should not undertake operations across the border. Instead, the CCMC instructed Chinese advisors to advocate a strategy of “concentrating forces” to deal with “the easiest first and the most difficult last.” This meant seizing the town of Nghĩa Lộ before attempting to occupy the entire northwest. The CCMC also advised the CMAG and DRVN leaders that, while striving for total victory in the northwest by the end of 1952, they should be prepared for a protracted war as PAVN troops still lacked offensive experience.Footnote 30

In late September 1952, Hồ Chí Minh secretly visited Beijing to confer with CCP leaders. The two parties reached a consensus on the overall strategy for the next stage of the war: PAVN forces would first direct their attention on the northwest (including northwestern Vietnam and upper Laos), then march southward from northern Laos, and finally push eastward toward the Red River Delta. As for concrete steps, Chinese and PAVN military planners decided first to concentrate on Nghĩa Lộ. Upon capturing Nghĩa Lộ, PAVN troops would not immediately attack Sơn La but focus on establishing bases around Nghĩa Lộ and building a highway linking Nghĩa Lộ and Yên Bái.Footnote 31

The northwest campaign began on October 14, 1952. PAVN leaders gathered eight regiments to attack French strongholds in Nghĩa Lộ. In ten days, they annihilated most enemy posts in the area. After a short period of readjustment, PAVN troops continued on to attack French positions in Sơn La and Lai Châu provinces. By early December 1952, large parts of the northwestern provinces were under DRVN control. In February 1953, the VWP leadership decided to move further west to connect the “liberation zone” in northwestern Vietnam with communist-occupied areas in northern Laos. By May, DRVN control extended across upper Laos, greatly augmenting its position in northwestern Indochina.

The Road to Điện Biên Phủ

In retrospect, by summer 1953, the confrontation between the DRVN and the French in Indochina had reached a turning point. The DRVN’s gains over the past two years meant that it could set its sights on attaining overwhelming superiority in the war. Meanwhile, with the end of the Korean War in July 1953, the Chinese were able to pay more attention to their southern neighbor. With the possibility of victory now seemingly in sight, the VWP leadership and the CMAG began to formulate military plans for the upcoming 1953–4 campaign.

Changes also took place on the French side. In May 1953, General Henri Navarre replaced General Raoul Salan (who had succeeded de Lattre in 1952) as the French commander in Indochina. Supported by the United States, Navarre adopted a new three-year strategy to regain the upper hand on the battlefield. He divided Indochina into northern and southern theaters along the 18th parallel; he also planned to eliminate the enemy in southern and south-central Vietnam by spring 1954 and then, by spring 1955, concentrate sufficient strength to fight a decisive battle against the communist forces in the Red River Delta. The United States, released from its heavy burden in Korea, now fretted about the consequences of a French loss in Indochina and boosted its military and financial support to France.

On August 22, 1953, the VWP Politburo, on Giáp’s initiative, decided to revert the focus of PAVN’s future operations from the mountainous northwestern area to the Red River Delta area. The former would remain on the PAVN’s operation agenda would no longer be a priority. Luo, who attended the VWP Politburo meeting, immediately reported this intended change to Beijing.Footnote 32 The CCP leadership, after reviewing Luo’s report, dispatched two urgent messages to Luo and the VWP leadership on August 27 and 29, respectively. The messages urged that the original plan – to focus on the northwestern battlefield – not be changed. As the CCP leaders stated in the August 29 telegram:

We should first annihilate enemies in the Lai Châu area, liberating northern and central Laos, and then gradually extend the battlefield toward southern Laos and Cambodia, thus putting pressure on Saigon. By executing this strategy, we will be able to limit the enemy’s human and financial resources and atomize his troops, leaving the enemy in a disadvantageous position … The realization of this strategic plan will surely contribute to the final defeat of the French imperialists’ colonial rule in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Of course, we need to overcome a range of difficulties and prepare for a prolonged war.Footnote 33

The VWP Politburo met in September to discuss the dispatches from Beijing. Hồ Chí Minh favored the advice given by the Chinese. The Politburo, after much debate, determined that the PAVN’s operational emphasis would remain in the northwestern area.Footnote 34 In late October and early November, the CMAG and the PAVN High Command worked out the operation plans for winter 1953 and spring 1954: PAVN forces would continue to focus on operations in Lai Châu, and would try to seize it in January 1954; then, they would attack various French strongholds in upper and central Laos. At the same time, PAVN troops would also move from central Vietnam toward Laos, making lower Laos the target of attacks from two directions. The VWP Politburo approved this plan on November 3.Footnote 35 Around the middle of the month, five regiments of PAVN forces headed toward Lai Châu.

On November 20, General Navarre responded to the PAVN’s march on Lai Châu by evacuating French forces from the area and dropping six parachute battalions into Diện Biên Phủ, a strategically important yet previously little-known village located in Vietnam’s mountainous northwest. If the French troops controlled Điện Biên Phủ, Navarre believed, they could prevent the communists from occupying the entire northwestern region and attacking upper Laos; moreover, the French could use the town as a “jumping-off point” for offensives against DRVN forces. The French quickly reinforced their troops in Diện Biên Phủ, secured the airstrip, and built defensive works there, transforming a mountain settlement into a fortified military base. Điện Biên Phủ quickly emerged as a focal point of the Indochinese battlefield.

When Wei Guoqing, who by then had returned to his post as head of CMAG after a long sick leave, learned of the French activity in Điện Biên Phủ, he suggested that the PAVN troops, while sticking to the original plan to attack Lai Châu, launch a separate campaign to surround the French forces at Điện Biên Phủ.Footnote 36 The VWP Politburo then decided to launch the Điện Biên Phủ Campaign, establishing in early December a frontline headquarters with Giáp as commander-in-chief and Wei as Giáp’s top Chinese advisor. Hồ Chí Minh called on the whole Party, people, and army “to spare no effort to ensure the success of the campaign.”Footnote 37 Thousands of peasants were mobilized to build roads and carry artillery pieces and ammunition over formidable mountain ranges, and PAVN troops gradually encircled the French forces. In response, Navarre sent more troops there.

Beijing’s leaders observed the ongoing Điện Biên Phủ Campaign with much enthusiasm. In particular, they emphasized that a DRVN victory at Điện Biên Phủ could have enormous impact on the development of the international situation, to say nothing of its military and political importance. This emphasis on Điện Biên Phủ’s international significance should be understood in the context of a new communist general strategy that took shape in late 1953 and early 1954. Following the end of the Korean War in mid-1953, the communist world initiated a “peace offensive.” On September 26, the Soviet Union proposed in a note to the French, British, and US governments that a five-power conference (including China) convene to facilitate the easing of international tensions. On October 8, PRC premier Zhou Enlai issued a statement supporting the Soviet proposal. Finally, the “Big Four” conference in Berlin at the end of January 1954 endorsed the Soviet-led plan to convene an international conference in Geneva to discuss the restoration of peace in Korea and Indochina. Beijing was invited to send a delegation to the conference. A victory at Điện Biên Phủ would greatly bolster the communists’ bargaining power at the forthcoming conference. In early to mid-March 1953, Zhou cabled Chinese advisors and Hồ Chí Minh himself to alert them to the forthcoming “international struggle” at Geneva. “To succeed in the field of diplomacy,” Zhou stressed, “DRVN troops should strive for a glorious victory on the battlefield.”Footnote 38

To strengthen the PAVN fighting force, the Chinese accelerated the delivery of military supplies. To cut Điện Biên Phủ off from French airborne support, Beijing sent back to Vietnam four Vietnamese anti-aircraft battalions that were then training in China. During the months of the Điện Biên Phủ siege, China rushed to provide Vietnam with more than 200 trucks; more than 10,000 barrels of oil; more than 100 cannons; 3,000 guns of assorted types; around 2,400,000 bullets; over 60,000 artillery shells; and about 1,700 tons of grain.Footnote 39

The Fall of Điện Biên Phủ

By March 1954, PAVN troops had been gathering at Điện Biên Phủ for three months. The Geneva Conference on Korea and Indochina was scheduled to begin in late April. The PAVN High Command, having consulted with their Chinese advisors, decided to launch the attack on Điện Biên Phủ on March 13. After PAVN forces captured two of the most vulnerable French outposts, Navarre ordered reinforcements to parachute into the besieged garrison.

On March 30, PAVN forces attacked the center of Điện Biên Phủ, where the French command headquarters was located. When Chinese advisors reported that sturdy French defenses had halted the PAVN advance, leaders in Beijing summoned engineering experts from the Chinese troops in Korea to advise the Vietnamese about digging trenches and underground tunnels.Footnote 40 On April 9, the CCMC telegraphed Wei, guaranteeing that the PAVN would receive enough artillery ammunition to finish the battle. The CCMC also instructed Wei to propose the following tactics to his PAVN counterparts: to cut off the enemy’s front by attacking the middle; to destroy the enemy’s underground defenses one section at a time with concentrated artillery fire; to immediately consolidate a newly seized position, no matter how small, thus continuously tightening the circle around the enemy; to use snipers widely to restrict the enemy’s activity; and to use political propaganda to undermine the enemy’s morale.Footnote 41

By mid-April, French troops in Điện Biên Phủ were confined to a small area of less than eight-tenths of a square mile (2 square kilometers), and the air bridge that they used to resupply the garrison had been severed. At this moment, Washington threatened to intervene. In a speech to the Overseas Press Club of America on March 29, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles issued a powerful warning that the United States would tolerate no communist gain in Indochina and called for “united action” on the part of Western countries. One week later, President Dwight Eisenhower invoked the “falling domino” theory to express the necessity of joint military operations against communist expansion in Indochina.

Despite the threat of US intervention, Chinese advisors in Vietnam insisted on continuing with the campaign. Wei believed the Vietnamese should not squander the superior position on the battlefield that they had fought so hard to attain. On April 19, the VWP Politburo decided to move ahead with the plan to crush the garrison with a new wave of attacks in early May. In preparation, the Chinese transferred large amounts of materiel to the Vietnamese. Two Chinese-trained Vietnamese battalions equipped with 75mm recoilless guns and six-barrel Katyusha rocket launchers arrived at Điện Biên Phủ on the eve of the final assault. Once again Beijing assured the Chinese advisors in Vietnam: “To eliminate the enemy totally and to win the final victory in the campaign, you should use overwhelming artillery fire. Do not save artillery shells. We will supply and deliver sufficient shells to you.”Footnote 42

The final communist assault on Điện Biên Phủ began on the evening of May 5. The newly delivered rocket launchers played a critical role in smashing the remaining French defenses. By the afternoon of May 7, French troops had neither the ability nor the will to fight, and surrendered. The Điện Biên Phủ Campaign ended in a spectacular victory for the Vietnamese communists.

Conferring in Geneva

As has occurred countless times throughout history, the French Indochina War was fought on the battlefield but its ultimate outcome would be decided at the negotiating table. As soon as Beijing decided to attend the Geneva Conference, Zhou managed to find time in his busy schedule to prepare for it. In late February, Zhou and his associates at the PRC foreign ministry worked out a plan to realize Beijing’s top priority goals for Geneva, which were to dismantle the United States’ “blockade, embargo and rearmament policies” against the PRC, and to highlight “New China’s diplomatic accomplishments in front of the world.” Indeed, Zhou and his associates deemed it essential that China not only “actively participate in the conference” but also “make it a success.” The United States’ negative attitude meant that the conference was not likely to reach a breakthrough on Korea. However, the prospect of reaching an agreement on Indochina looked brighter, especially as there were some areas of disagreement between Paris and Washington. China should thus adopt “a policy of showing the carrot to France while using the stick to deal with the United States” and make sure that the conference “does not end inconclusively.” On March 2, top CCP leaders approved the plan.Footnote 43

Zhou knew that he needed to coordinate strategies with Beijing’s communist allies for his plans to succeed. When Hồ Chí Minh and Phạm Vӑn Đồng, deputy prime minister and foreign minister of the DRVN, visited Beijing in late March, Zhou emphasized that the Vietnamese communists should “actively participate in” the Geneva Conference and strive for a peaceful settlement. To this end, Zhou suggested, the DRVN might consider accepting “a relatively fixed demarcation line in Vietnam,” as this would allow them to “control an area that is linked together.”Footnote 44

Together with Hồ Chí Minh and Đồng, Zhou flew to Moscow in early April 1954. He found that the post–Stalin Soviet leadership was equally eager to end the conflict in Indochina through negotiation. Molotov, the Soviet foreign minister, told Zhou that the Geneva Conference could potentially solve one or two problems. Zhou said to Molotov that as this was the first time the PRC would attend an important international conference they would be more than willing to listen to the opinions of their Soviet comrades.Footnote 45 Zhou and the Soviet leaders reached a broad consensus about their respective countries’ strategies at the Geneva Conference.

The Geneva Conference began on April 26. As Zhou had anticipated, negotiations on Korea stalemated almost immediately. On the conference’s third day, Zhou reported to Beijing that while “the discussions on Korea [had] already entered a deadlock,” Indochina still looked hopeful. He noted that Georges Bidault, the French foreign minister, was “eager to discuss the Indochina question” and had already “approached Molotov” and expressed “the desire to meet with us.” Zhou predicted that “the discussion on Indochina could begin ahead of schedule.”Footnote 46

Formal discussion on Indochina at Geneva began on May 8, the day after the fall of Điện Biên Phủ. Although in preconference consultations with Beijing and Moscow the Vietnamese communists had agreed to accept a settlement based on temporarily dividing Vietnam into two zones, they now hoped to squeeze more concessions out of their adversaries at Geneva. Đồng announced that in exchange for ending the war in Indochina, the DRVN would ask to establish its virtual control over most of Vietnam. He also pushed for a package settlement that would include all three countries of French Indochina and give “due rights and position” to the “resistance forces” in Laos and Cambodia. Those “resistance forces” included many Vietnamese whom Đồng described as “volunteers,” but who were in fact DRVN-sponsored personnel.Footnote 47

Zhou, as he later acknowledged, had not paid much attention to “the distinctions and differences between the three countries of Indochina” before he arrived in Geneva. So, he and the Soviets initially supported the DRVN’s demand for a package settlement. However, Zhou quickly came to change his mind. His experience at Geneva, especially his talks with representatives from Laos and Cambodia, demonstrated to him that “the national and state boundaries between the three associate countries in Indochina were quite distinctive,” and that “the royal governments in Cambodia and Laos were seen as legitimate by the overwhelming majority of their people.” Therefore, he realized, “we must treat them as three different countries.”Footnote 48

Zhou’s changing attitude was supported by his sense that the DRVN had to be more flexible to reach a ceasefire in Indochina. His meeting with Molotov on June 1 – which the Vietnamese joined – reaffirmed the communists’ commitment to pursue a strategy of partitioning zones of control between the two sides in a ceasefire agreement.Footnote 49 Zhou highlighted the merits of this approach in his communication with Beijing and with Hồ Chí Minh and Giáp, whom he contacted through Beijing. A ceasefire in place “is not favorable to us,” he contended, as this would not allow the DRVN to control the whole northern part of the country. Conversely, dividing Vietnam into northern and southern zones would give the DRVN control of a large contiguous area while making the ceasefire much more manageable.Footnote 50

On June 15, the sessions on Korea ended in Geneva with no result. Zhou was concerned that the conference’s Indochina discussions might also fall apart. At this critical moment, the French parliament ousted Prime Minister Joseph Laniel and replaced him with Pierre Mendès France, a longtime critic of the war in Indochina. Mendès France promised that he would lead the negotiations to a successful conclusion by July 20, or he would resign. Zhou regarded this as a potential opportunity to help push the negotiations on Indochina forward.

On the day of the collapse of the discussions on Korea at Geneva, Zhou, together with Molotov, met with Đồng. Zhou was straightforward: Đồng’s refusal to admit the existence of DRVN forces in Laos and Cambodia would render the negotiations fruitless, and the Vietnamese comrades themselves would also lose a golden opportunity for a peaceful solution. Zhou proposed a new line in favor of the withdrawal of all foreign forces, including the DRVN “volunteers,” from Laos and Cambodia, so that “our concessions on Cambodia and Laos would prompt the other side to concede on dividing Vietnam into two zones.” Molotov firmly supported the proposal. Đồng, under heavy pressure, also gave his consent.Footnote 51

Zhou immediately relayed the new communist approach to the British and the French. On June 16, at 12:30 p.m., he met with Anthony Eden, the British foreign secretary. If the United States did not maintain military bases in Laos or Cambodia, he told Eden, Beijing was willing to recognize the royal governments of these two countries, and would also persuade the DRVN to recall its “volunteers.”Footnote 52 At 3:30 p.m., Zhou introduced to the Geneva Conference a new proposal for reaching a ceasefire in Indochina, which included the withdrawal of all foreign forces from Laos and Cambodia. The next day, when Mendès France became French prime minister, Zhou met with Bidault. In addition to what he had told Eden, Zhou stressed that China had no objection to Laos and Cambodia remaining in the French Union.Footnote 53

Zhou’s efforts, coupled with the French and British eagerness not to allow the conference to fail, helped the two contending sides reach an agreement on June 19 in military talks, opening the door to “the cessation of hostilities” in Laos and Cambodia. The Geneva Conference then adjourned for the next three weeks. This break afforded Zhou the opportunity to further coordinate communist strategies for the last and most crucial round of negotiations at Geneva.

Zhou’s priority concern, as he expressed in a lengthy telegram dispatched to Beijing on June 19, remained how to persuade the Vietnamese communists to make the necessary concessions at Geneva. In order to reach the best possible deal at the conference, Zhou contended, the Vietnamese delegation had to give up some of their claims, especially those about Cambodia and Laos. However, Zhou complained, they did not seem to understand this point, and their plans had “failed to match the realities” of the circumstances. If they were to stick to such an approach, “the negotiations cannot go on, and our long-term interests … will not be best served.”Footnote 54 He proposed to capitalize on the conference break by meeting with Hồ Chí Minh and Giáp face-to-face, so that “a consensus [would] be worked out.” Zhou’s comrades in Beijing approved his plans the same day.Footnote 55

The Zhou Enlai–Hồ Chí Minh Meeting at Liuzhou

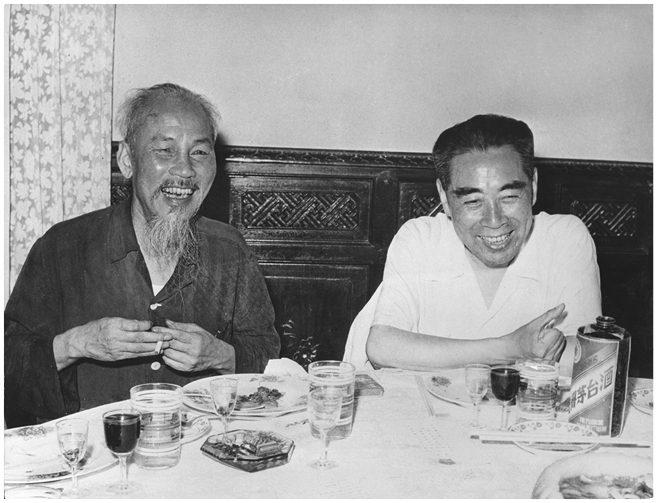

The meeting that Zhou had proposed was held in Liuzhou, a small city in Guangxi near the Chinese-Vietnamese border, on July 3–5 (Figure 8.1). First, Giáp, per Zhou’s suggestion, gave a detailed report on the military situation in Indochina. The enemy had suffered a huge setback at Điện Biên Phủ, but was far from defeated, said Giáp. New French reinforcements had arrived in Indochina, and the total strength of the enemy troops, at around 470,000, was greater than that of the PAVN, at around 300,000. Additionally, the enemy still controlled such big cities as Hanoi, Saigon, Huế, and Đà Nẵng. Giáp acknowledged that the overall balance of force between the two sides on the battlefield had not changed.Footnote 56

Figure 8.1 Hồ Chí Minh with Zhou Enlai (1898–1976), prime minister of the People’s Republic of China, during a visit by Zhou to Hanoi (1960).

Zhou began his presentation with a question: “If the United States does not interfere, and France sends in more troops, how long will it take for us to seize the whole of Indochina?” Giáp estimated that this would take another two to three years, or more likely, three to five years. Zhou then spoke at length about the correlative relationship between military operations in Indochina and the negotiations in Geneva. The Indochina War had already been internationalized, and there existed the great danger that the Americans might intervene there. Since the imperialist countries had so viscerally feared the expanding influence of the Chinese revolution, they would not allow the Vietnamese revolutionaries to win a glorious victory. Therefore, Zhou argued, “if we ask too much at Geneva, and if peace is not achieved, the United States will surely intervene,” delaying the Vietnamese communists’ victory. “We must isolate the United States and foil its plans,” emphasized Zhou, “otherwise we will fall into the US imperialists’ trap.”Footnote 57

Later in the meeting, Zhou defined four criteria for a desirable settlement: (1) Effecting a simultaneous ceasefire in all three Indochina countries; (2) Locating the demarcation line at the 16th or 17th parallel; (3) Forbidding the transportation of weapons and ammunition into Indochina after the settlement; and (4) Shutting down all foreign military bases in the three countries. In the meantime, Zhou elaborated, Cambodia and Laos should be allowed to pursue their own path of development independent of any military alliance and absent any foreign forces on their respective soil.Footnote 58

Zhou’s presentation seemed to have resonated with his Vietnamese comrades, especially Hồ Chí Minh. At the end of the meeting, Hồ Chí Minh thanked Zhou for “not only conducting the struggle in Geneva but also coming here to give this important report.” He was in “complete agreement” with Zhou and promised to adjust the DRVN’s aims and strategies in accordance with Zhou’s advice, as “now Vietnam is standing at the crossroads, headed either to peace or to war, and the main direction should be the pursuit of peace.”

The reasons for the change in the Vietnamese negotiating position remain a matter of dispute among historians. Although some credit Zhou with convincing Hồ Chí Minh and his colleagues to make concessions, others argue that the Vietnamese had already concluded that compromise was necessary. DRVN leaders appear to have been particularly worried by the announcement in late June that Ngô Đình Diệm, a staunch anticommunist with close ties to the United States, would be taking over as premier of the Saigon-based State of Vietnam (SVN). According to some scholars, DRVN leaders believed that Diệm’s appointment had heightened the risk of US intervention in the war, if they did not make peace quickly.Footnote 59

Whatever the specific circumstances, the PRC and DRVN were now in broad agreement on how to proceed in the next phase of negotiations: They would give preference to a settlement for Vietnam that provided for the country to be temporarily split at the 16th or 17th parallel, and they would accept a political settlement that might lead to the establishment of noncommunist governments in Laos and Cambodia.Footnote 60

On July 5, the VWP Central Committee issued a directive calling for a ceasefire based on the temporary partition of Vietnam, to be followed by the unification of the country through a national plebiscite.Footnote 61 The directive clearly reflected Hồ Chí Minh and Zhou’s agreement in Liuzhou.

On July 7, Zhou, who had returned to Beijing, reported at a meeting of the CCP Politburo that the Chinese delegation at Geneva had adopted “a policy line to pursue cooperation with France, Britain, Southeast Asian countries and the three countries in Indochina – that is, to unite with all the international forces that can be united and to isolate the United States – so that America’s plans for expanding its global hegemony will be hindered and undermined.” Mao and the CCP leadership fully endorsed Zhou’s report.Footnote 62

Zhou flew from Beijing to Moscow two days later. On June 10, he met for two hours with a group of Soviet leaders, including Georgy M. Malenkov, Kliment Voroshilov, Lazar Kagaonovich, and Anastas Mikoyan. He found that “the analysis and viewpoints of the Soviet Party Central Committee were identical to those that we discussed at Liuzhou and Beijing.” As for such issues as “the division of zones, treatment of Laos and Cambodia, responsibility and power of the committee of neutral countries, and the commitments made by the conference participants” during the next stage of negotiations, “the policy-line that we should follow is to make sure that an agreement can be quickly reached.” Therefore, the communist side should introduce “fair and reasonable conditions that the French government is in a position to accept.” In particular, it was crucial to prevent “the interference and sabotage of the United States.” Zhou also reported that “decisions on all concrete issues will be made after I return to Geneva and meet with Comrades Molotov and Phạm Vӑn Đồng, so that we may quickly reach an agreement.”Footnote 63

The End of the French Indochina War

Zhou arrived in Geneva on the afternoon of July 12. The next twenty-four hours of his schedule were packed with meetings. At 7:00 that evening, Zhou met with Molotov. He briefed the Soviet foreign minister on his meetings with Hồ Chí Minh in Liuzhou, as well as his discussions with Soviet leaders in Moscow. Molotov asked Zhou if he believed it feasible to set the demarcation line at the 16th parallel. Zhou said that he and Hồ Chí Minh had agreed to aim for a 16th parallel solution but would accept the 17th parallel if absolutely necessary. Zhou and Molotov were now allied in their mission to push the Geneva Conference toward a peaceful settlement in Indochina.Footnote 64

Zhou believed that he had detected Đồng’s reluctance to carry out the VWP’s “July 5th Instruction.” He therefore arranged to meet overnight with Đồng. He told Đồng that the “July 5th Instruction” was based on a consensus between the Chinese, Soviet, and Vietnamese leaders. He also mentioned that the danger of direct US military intervention in Indochina was serious and real. To avoid such a scenario, the communist side “must actively, positively and quickly carry out negotiations to pursue a settlement, and must keep the negotiations simple and avoid complicating them, so that Mendès France will not be forced to resign.” Zhou also promised Đồng that “with the eventual withdrawal of the French, all of Vietnam will be yours.” Đồng finally yielded to Zhou’s logic, if not to his pressure.Footnote 65

Zhou met with Mendès France at 10:30 a.m. on July 13. He found that the French prime minister was now chiefly concerned with the location of the demarcation line. Zhou told Mendès France that while the communists preferred to draw the line along the 16th parallel, they were willing to compromise.Footnote 66 At 11:45 a.m., Zhou conferred with Eden, telling him that the Chinese and Vietnamese had reached an agreement on pursuing peace in Indochina. “If France is willing to make further concessions on the question of dividing zones,” he promised Eden, “the Vietnamese will also make due concessions.”Footnote 67

Zhou meant what he said. When, at the final stage of the conference, Mendès France insisted upon setting the demarcation line at the 17th parallel, expressing that this represented the full extent of his concession, and that he would otherwise have to resign, Zhou, with Molotov’s blessing, decided to change the Communist position to the 17th to meet the French requirement.Footnote 68 Thus, the Geneva Conference reached a settlement on Indochina in the early morning of July 21; officially, Mendès France had not exceeded his deadline.

With the signing of the Geneva Accords, the French Indochina War came to an end. The Chinese delegation left Geneva having achieved nearly all of their goals for the conference: the creation of a communist-ruled North Vietnam would establish a buffer zone between China and the capitalist world in Southeast Asia; the opening of a new dialogue between China and such Western powers as France and Great Britain would help break the PRC’s global isolation; and, much more important, the crucial role played by China at the conference implied that for the first time in modern history China had been accepted by the international community – friends and foes alike – as a real world power. All of this, in turn, provided Mao and the CCP leadership new resources with which to promote broader and deeper domestic mobilizations.

But the confrontation in Indochina was far from over. The compromise peace reached at Geneva did not settle the deep disagreements among Vietnamese over the path that their country should take toward its postcolonial future. Diệm’s Saigon-based State of Vietnam and the US government both declined to endorse the Geneva Accords – moves that presaged their subsequent refusal to support the 1956 reunification elections. The DRVN also abandoned key parts of the agreement, including the provisions guaranteeing the neutrality of Laos and Cambodia. By the end of the 1950s, the uneasy peace between North and South Vietnam had given way to a new Indochina conflict that would turn out to be even longer and bloodier than the first. More surprisingly – and ironically – communist China and a unified communist Vietnam would enter the Third Indochina War in 1979 as adversaries. The origins of their enmity, however, could be traced back to their cooperation during the years of the French Indochina War.