Introduction

In cognitive behavioural journals and scientific meetings, the subject of grief seems to receive less attention than other emotional states, such as anxiety or depression. Grief is recognised as a normal human reaction to the death of a loved one and incorporates unpleasant, potentially distressing emotions, psychological phenomena, such as intrusive images, and physical sensations. Understandably, there has been reluctance to pathologise grief responses. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has put the subject of death centre stage as millions of people worldwide have been bereaved in extraordinary circumstances. Psychological therapists have been asked to provide effective therapeutic responses for clients with enduring distressing grief reactions.

In this paper, we draw on decades of research and clinical expertise from our experience in applying cognitive therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) to enduring grief reactions. We derive lessons learned for treating prolonged and traumatic bereavement. Many of the clinical trials at the Oxford Centre for Anxiety Disorders and Trauma and Omagh/Queen’s University Belfast trauma centres have included patients who have experienced significant traumatic loss (Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Gillespie and Clark2007; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Hackmann, Grey, Wild, Liness, Albert, Deale, Stott and Clark2014; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Wild, Stott, Warnock-Parkes, Grey and Clark2022).

During the pandemic the authors of this paper delivered several workshops on prolonged and traumatic grief where clinicians raised a number of thought-provoking questions. Our responses form the basis of this paper.

-

(1) How do we differentiate between normal and abnormal or pathological grief?

-

(2) How should we describe or categorise or label pathological grief, and is it a specific and distinct condition or disorder?

-

(3) How effective are existing therapies for prolonged and traumatic grief and is there a role for CBT in the treatment of these conditions?

-

(4) Can our experiences with cognitive therapy for PTSD (Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Clark, Hackmann, McManus and Fennell2005) help with these conditions or are different techniques and skills required?

The purpose of this paper is to answer these important questions and in so doing, consider the historical and theoretical concepts relating to complex and traumatic grief; factors that differentiate normal grief from abnormal grief; and maintenance factors as well as implications for CBT treatments.

(1) How do we differentiate between normal and abnormal or pathological grief?

Experience of grief

For most bereaved people, any initial intense emotions reduce within weeks and months. However, a proportion of bereaved relatives experience difficulties that persist rather than diminish over time, ranging between 10% (Kersting et al., Reference Kersting, Brähler, Glaesmer and Wagner2011) and 20% (Shear et al., Reference Shear, McLaughlin, Ghesquiere, Gruber, Sampson and Kessler2011), and many do not seek clinical help (Lichtenthal et al., Reference Lichtenthal, Nilsson, Kissane, Breitbart, Kacel, Jones and Prigerson2011) despite significant social impairment.

Studies have demonstrated that resilience to persistent grief is shown by around half (between 45 and 65%) of bereaved individuals (Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Wortman, Lehman, Tweed, Haring, Sonnega and Nesse2002; Mancini et al., Reference Mancini, Sinan and Bonanno2015). In a 6-year study of tourists who survived tsunamis (Sveen et al., Reference Sveen, Bergh Johannesson, Cernvall and Arnberg2018), most bereaved were resilient (41%) or recovered (48%), with a minority reporting chronic grief reactions (11%). In an 18-month study of grief trajectories, Smith and Ehlers (Reference Smith and Ehlers2020) found that 40.7% of bereaved adults reported low levels of grief throughout the study period. Most bereaved individuals adjust and are able to re-connect with society and re-engage in pleasurable activities (Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Wortman, Lehman, Tweed, Haring, Sonnega and Nesse2002; Mancini et al., Reference Mancini, Sinan and Bonanno2015), even after a major loss (Wortman and Silver, Reference Wortman and Silver1989).

In the literature different terms are used to categorise pathological grief reactions, including complicated grief (CG), traumatic grief (TG), prolonged grief disorder (PGD), and prolonged complex bereavement disorder (PCBD). In this paper we will use the terms uncomplicated grief (UG), complicated grief (CG) and prolonged grief disorder (PGD), the term now accepted within the ICD-11 and the DSM-5 diagnostic manuals.

Uncomplicated vs prolonged grief

When feelings of grief wane and the bereaved person experiences positive emotions alongside episodes of sadness and loss, their experience is described as uncomplicated grief. In complicated grief, however, episodes of grief are frequent, prolonged and more intense. In UG there is a reduced longing for the deceased and gradual acceptance of the death, whereas with prolonged grief, a sense of intense yearning persists. In UG, memories of the deceased are interspersed with other memories, but in prolonged and traumatic grief, the bereaved can be engrossed in long periods of thinking about the deceased. They may be ambivalent or unable to accept the death. They may be pre-occupied with or dwell upon the death, which can trigger intrusive images of how the person died. In UG, life still holds meaning and purpose, therefore, despite feeling sad and missing the deceased, the bereaved are able to resume activities and develop relationships. However, with prolonged grief, avoidance and social withdrawal are more enduring features and predict worse outcomes for those bereaved (Smith and Ehlers, Reference Smith and Ehlers2020). Prigerson et al. (Reference Prigerson, Maciejewski, Reynolds, Bierhals, Newsom, Fasiczka, Frank, Doman and Miller1995) have proposed that the most useful items to differentiate complicated grief from uncomplicated grief are: shock; intrusions about the deceased; resentment about the death; psychic numbing (being stunned or dazed by the loss); functional impairment; hostility and avoidance of reminders of the death.

(2) How should we describe or categorise or label pathological grief? Is it a specific and distinct condition or disorder?

Terminology and co-morbidity

Various terms have been used to define enduring and severe forms of grief reactions such as prolonged, complex, complicated and traumatic. The range of terminology reflects a historical lack of consensus in the field about how to categorise complex grief (Stroebe et al., Reference Stroebe, van Son, Stroebe, Kleber, Schut and van den Bout2000), and whether prolonged and complicated grief requires a distinct diagnostic category (Prigerson et al., Reference Prigerson, Horowitz, Jacobs, Parkes, Aslan, Goodkin and Raphael2009; Stroebe et al., Reference Stroebe, Schut and Finkenhauer2001). It is recognised that bereaved individuals can develop a number of psychological disorders such as depression (Zisook et al., Reference Zisook, Shuchter, Sledge, Paulus and Judd1994), anxiety disorders (Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs, Hansen, Kasl, Ostfeld, Berkman and Kim1990) and PTSD (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Braun, Tillery, Cain, Johnson and Beaton1999; Schut et al., Reference Schut, de Keijser, van den Bout and Dijkhuis1991). There are also high rates of co-occurrence between complicated grief and other disorders. A review by Komischke-Konnerup et al. (Reference Komischke-Konnerup, Zachariae, Johannsen, Nielsen and O’Connor2021) estimated that up to 70% of adults meeting criteria for prolonged grief disorder (PGD) experienced one or more other type of complicated grief reaction, whilst 46% experienced two or more other types of complicated grief reactions. The review estimated that co-occurring disorders with PGD were as follows: depression (63%), anxiety (54%) and PTSD (49%). In a review specifically focusing on mental disorders in widowhood, the pooled prevalence reported in studies for depression was 40.6% and 26.9% for anxiety disorders (Kristiansen et al., Reference Kristiansen, Kjær, Hjorth, Andersen and Prina2019).

Complex grief vs major depressive disorder

There are distressing symptoms amongst those with severe bereavement reactions that do not seem to be adequately captured by broader diagnostic categories (Prigerson et al., Reference Prigerson, Bierhals, Kasl, Reynolds, Shear, Day, Beery, Newsom and Jacobs1997). For example, when comparing major depressive disorder (MDD) with complex grief (PGD), there are subtle and important differences. The all-encompassing loss of interest and pleasure in MDD is different to the loss of interest and pleasure in PGD, which is linked to an intense yearning for the company of the deceased. Repeated proximity seeking behaviours to the deceased common in PGD are not relevant to MDD, and the attentional focus on loss characterises PGD and not MDD. Pre-occupation with thoughts and memories of the deceased in PGD are similar to, but different from, ruminations of perceived failures in MDD. Finally, social withdrawal is common in both MDD and PGD, but in CG, there is a more specific avoidance of activities, situations and people associated with the deceased.

Categorisation of complex grief

In the most recent edition of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11) (World Health Organization, 2012), PGD was installed as a new diagnostic category. In contrast to ICD-11, the authors of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) initially decided that the evidence was not yet sufficient to merit a formal diagnostic category. Instead, when DSM-5 was published, a set of criteria for ‘prolonged complex bereavement disorder’ (PCBD) was inserted in the appendices as a condition requiring further study. However, in November 2020, the American Psychiatric Association Assembly approved the formal inclusion of PGD as an update to the DSM-5 (Prigerson et al., Reference Prigerson, Boelen, Xu, Smith and Maciejewski2021) indicating a growing international consensus on definitions and diagnostic criteria for the disorder. One important difference between the two classification systems is the duration of the symptoms required to meet the diagnosis: DSM-5 requires symptoms to persist for a minimum of 12 months; ICD-11 requires a minimum of 6 months.

The core element of prolonged grief definitions for DSM-5 and ICD-11 diagnostic categories is persistent yearning for or intensely missing the deceased, or pre-occupation with the circumstances of the death. Yearning is an intense longing for the deceased to return and fill the void created by the loved one’s death. Additional symptoms include: difficulty accepting the death, feelings of loss of a part of oneself, anger about the loss, guilt or blame regarding the death, or difficulty engaging with new social or other activities due to the loss.

However, questions remain. For example, it is unclear whether the ICD-11 (World Health Organization, 2012) category for PGD conceptualises complicated grief as a homogenous diagnosis, or whether there are sub-categories relating to traumatic grief or traumatic loss. Stroebe et al. (Reference Stroebe, Schut and Stroebe2005) have made a case for complicated grief to be considered separately from traumatic grief. They contend that the distinction between the two relates to the theoretical underpinnings unique to each condition. Whereas traumatic grief arises from ‘abnormal’ traumatic life events and its aetiology is informed by theories of post-trauma psychopathology, complicated grief is typically associated with ‘normal’ life events, i.e. death and bereavement, and is informed by attachment theories, which emphasise the nature of the relationship with the deceased. Such deliberations raise questions about whether trauma-based models derived from traumatic stress research, or loss-based models linked to attachment theories, are best placed for guiding treatment development and delivery.

Predictors of prolonged and complex grief

It is not possible to provide a comprehensive list of risk factors for PGD within the scope of this paper. However, in a review of published studies, Prigerson et al. (Reference Prigerson, Horowitz, Jacobs, Parkes, Aslan, Goodkin and Raphael2009) report risk factors and clinical correlates of PGD: a history of childhood separation anxiety; controlling parents; parental abuse or death; a close kinship relationship to the deceased; insecure attachment styles; marital supportiveness and dependency; and lack of preparation for the death. These variables suggest that attachment issues may be relevant to vulnerability to PGD.

Type of loss experienced does seem to influence rates of chronic grief with higher rates being reported for violent traumatic death (Currier et al., Reference Currier, Holland and Neimeyer2006). Child loss has been found to be a strong predictor of chronic grief (Meert et al., Reference Meert, Shear, Newth, Harrison, Berger, Zimmerman, Anand, Carcillo, Donaldson, Dean, Willson and Nicholson2011; Sveen et al., Reference Sveen, Bergh Johannesson, Cernvall and Arnberg2018). In a population-based prevalence study (Kersting et al., Reference Kersting, Brähler, Glaesmer and Wagner2011), highest rates of complicated grief were for bereaved individuals who had lost a child (23.6%), followed by loss of a spouse (20.3%), violent death (20%), suicide (18.1%), and death by cancer (10.1%). High risk predictors for developing complicated grief were female gender, lower income, older age, having lost a child or a spouse, or cancer as the cause of death (Kersting et al., Reference Kersting, Brähler, Glaesmer and Wagner2011). Smith and Ehlers (Reference Smith and Ehlers2020) found that of all loss characteristics such as mode of death and age, only child loss was a unique predictor of severe and enduring grief.

Prolonged grief arising from violent or traumatic events appears to differ from non-traumatic prolonged grief. Some studies have found that violent losses are more likely to generate distressing intrusive memories than non-violent deaths (Djelantik et al., Reference Djelantik, Smid, Mroz, Kleber and Boelen2020). In a study of bereaved spouses, Kaltman and Bonanno (Reference Kaltman and Bonanno2003) found that violence of the loss, but not suddenness of the loss, was related to PTSD symptoms. Smith and Ehlers (Reference Smith and Ehlers2021) found that bereaved people meeting criteria for PGD, or PGD+PTSD, or PTSD-only, show different cognitive risk factors. Differences in loss-related cognitions, memory characteristics and coping strategies distinguished PTSD from PGD, as well as from PGD co-morbid with PTSD, pointing to distinct cognitive correlates of post-loss clinical problems. Memory characteristics (such as being reminded of the loss for no apparent reason or struggling to access positive memories without the deceased), negative grief appraisals (such as believing one could never be strong again without the deceased), and perceived social disconnection were cognitive predictors most prominent in the co-morbid PGD+PTSD class compared with the PTSD-only class, suggesting that cognitive processes linked to severe grief reactions may be different from traumatic grief responses.

Another point of interest relates to how to define ‘traumatic loss’. Does losing a loved one in extraordinary circumstances such as the COVID-19 pandemic constitute a traumatic loss? Such theoretical discussions invite scholarly debate and have vital implications for clinical practice.

Social and inter-personal considerations

Neimeyer and colleagues (Reference Neimeyer, Keese, Fortner, Malkinson, Rubin and Witztum2000) posit that the experience of grief is an active process that is personal and inherently social in nature. The social context (Bonanno and Kaltman, Reference Bonanno and Kaltman1999; Walter, Reference Walter1999), cultural factors (Klass and Chow, Reference Klass, Chow, Neimeyer, Harris, Winokuer and Thornton2011), and human values (Maercker et al., Reference Maercker, Mohiyeddini, Muller, Xie, Yang, Wang and Muller2009) can influence how an individual psychologically and emotionally processes loss. Dyregrov et al. (Reference Dyregrov, Nordanger and Dyregrov2003) highlighted that psychosocial problems, such a self-isolation, are associated with post-loss mental health problems. In a study of cognitive predictors of grief trajectories over 18 months, Smith and Ehlers (Reference Smith and Ehlers2020) found that impaired social connectedness was an important predictor for those who met criteria for PGD co-morbid with PTSD.

Disenfranchisement

Doka (Reference Doka2002) introduced the concept of ‘disenfranchised grief’ when grief is not openly acknowledged, socially validated or publicly observed in a usual and traditional manner such as with religious rituals, funerals and community-based activities. This concept can be relevant to bereavement complications in circumstances such as civil conflict, where death may occur in controversial circumstances and grief may not be openly acknowledged or socially accepted. This concept is also relevant to the recent COVID-19 pandemic, during which many people died in extraordinary circumstances. People died in hospital wards isolated from family members, attendance at funerals was restricted and for some, there was an element of stigma attached to death by a new frightening disease.

Dependency

The type of relationship with the deceased has been found to be an important factor associated with chronic grief. Pre-loss interpersonal dependency as well as dependency on the deceased have been found to be associated with chronic grief (Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Wortman, Lehman, Tweed, Haring, Sonnega and Nesse2002). Smith and Ehlers (Reference Smith and Ehlers2020) found that those with higher levels of adaptation to loss reported healthier dependency styles compared with those who struggled to adapt to their loss.

Sources of support

In a survey of 678 bereaved people Aoun et al. (Reference Aoun, Bree, White, Rumbold and Kellehear2018) identified that the most frequently used sources of support were informal, such as family, friends and funeral providers whilst professional resources, such as social workers, psychologists and psychiatrists were the least used. Aoun and colleagues (Reference Aoun, Bree, White, Rumbold and Kellehear2018) reported that professional sources had the highest proportions of perceived unhelpfulness. In a study with families of homicide victims, Bottomly and colleagues (Reference Bottomley, Burke and Neimeyer2017) highlight the limits of psychotherapy or peer support groups to provide sufficient aid in the wake of traumatic loss. Bottomley et al. (Reference Bottomley, Burke and Neimeyer2017) found that the most helpful forms of social support were practical, physical assistance and subsequently recommended clinicians to adopt a public health focus facilitating access to specific services (e.g. child care, financial assistance).

Self-appraisal

In keeping with our clinical experiences, Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Wild and Ehlers2020) found that appraisals about social disconnection predicted the severity of symptoms of prolonged grief disorder and may act as a barrier to utilising social support. Patients with strong negative appraisals about the self, the world and others after loss are more likely to disengage from social interaction. Appraisals such as: ‘I have changed’, ‘Other people will regard me differently’, ‘I am permanently changed and no one will be able to relate to me’, can lead to increased social avoidance, which in turn, can reinforce such beliefs as well as creating more time for unhelpful periods of rumination. The more prolonged these periods of isolation are, the more entrenched beliefs become about a changed sense of self. One mother who lost two children in separate tragedies became convinced that she was completely changed and now ‘abnormal’, believing that other mothers would instantly view her in this way.

Societal and cultural factors

Societal and cultural factors are relevant to grief experiences. One question that emerges is whether it is necessary to assess needs and provide interventions at individual and community levels to deal with grief recovery, especially after large scale trauma with multiple deaths. Such large scale traumatic events generally result in higher levels of PGD among the bereaved (Li et al., Reference Li, Chow, Shi and Chan2015; Liang et al., Reference Liang, Cheng, Ruzek and Liu2019 Shear et al., Reference Shear, McLaughlin, Ghesquiere, Gruber, Sampson and Kessler2011). Understanding traumatic grief in such circumstances requires attention to societal and cultural norms, including rituals and ceremonies, which may influence grieving processes and may vary across cultures and religious groups. One of the research objectives after the Omagh bombing was to discover possible effects on community cohesion and the results were encouraging, with 40.6% reporting that they felt ‘more a part of the community’ since the bombing (Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Bolton, Gillespie, Ehlers and Clark2013). The Omagh studies were used to inform interventions at individual, community and societal levels, targeting social connectivity for the bereaved and other victims.

(3) Psychological therapies for CG and TG?

Non-CBT informed models of grief

Early models of grief derived from Freud’s theories (Reference Freud and Strachy1963) proposed that grief was the necessary process of breaking attachment to a love object, ‘the cost of commitment’ (Parkes, Reference Parkes1985). Subsequent models were derived from Kubler-Ross’s (Reference Kubler-Ross1969) observations of people living with a terminal illness proposing that the bereaved had to adjust to the loss via stages of shock, denial, bargaining, depression and finally acceptance. Bowlby and Parkes (Reference Bowlby, Parkes and Anthony1970) produced a stages theory of grief derived from attachment theory, suggesting phases of: numbness, yearning, disorganisation/despair and reorganisation. Later, Bowlby (Reference Bowlby1980) described these stages as shock, protest, despair, detachment, and personality reorganization. These models tended to view the person grieving as passive and the grief process as linear, sequential, and time limited. The goal for therapists adopting these frameworks was to facilitate the bereaved client to relinquish attachment to the deceased person and phrases such as ‘moving on’ and ‘letting go’ were part of the grief therapy nomenclature. Pathological grief was considered to be associated with an ambivalent relationship to the deceased.

Later theorists challenged the assumption that ‘detachment from’ the deceased is the desired outcome of grieving. Worden (Reference Worden1991) proposed four tasks of mourning: accepting the reality of the loss, working through the pain, adjusting to the environment, and ‘moving with’ the grief. The concept of continuing bonds, and looking at ways of ‘moving with’, rather than ‘moving on’ or relinquishing attachments from the relationship with the deceased, has important clinical implications (Klass et al., Reference Klass, Silverman and Nickman1996; Neimeyer, Reference Neimeyer2001). Grieving, based on this conceptualisation, involves reconstructing personal beliefs that have been challenged by the loss, and finding a means of retaining memories of the deceased, without focusing on how the person died and the distress associated with the death.

Stroebe and Schut’s (Reference Stroebe and Schut1999) dual process theory of bereavement proposes that the bereaved oscillate between loss-orientated processes (such as experiencing loss related intrusions, continuing bonds with the deceased, avoiding restoration of one’s life) and restoration-orientated processes (such as attending to life changes, distracting oneself from grief and forming new roles and relationships). Stroebe and colleagues (Reference Stroebe, Schut and Stroebe2005) submit that different coping styles are employed and effective for bereaved people according to their attachment style. Thus, they suggest that for some bereaved individuals, it will be more appropriate to work toward retaining ties, and for others to work toward loosening ties with the deceased person.

Evidence for non-CBT models of grief

There is little evidence of benefits from ‘grief work’ in general to come to terms with the death of a loved one. A meta-analysis of 35 grief therapy studies, undertaken before many of the current complex grief treatments were developed, found that treatments had a limited and small effect relative to psychotherapy for other conditions (Litterer et al., 1999). Subsequent studies of grief interventions for grief reactions have reported low to medium effects (Currier and Holland, Reference Currier and Holland2008; Wittouck et al., Reference Wittouck, Van Autreve, De Jaegere, Portzky and van Heeringen2011). A review by Jordan and Neimeyer (Reference Jordan and Neimeyer2003) concluded that generic grief interventions for bereaved populations are not necessary and ineffective. Currier and Holland’s (Reference Currier and Holland2008) meta-analysis of grief therapy studies found that interventions had a small effect at post-treatment but no statistically significant benefit compared with control groups at follow-up. However, interventions were more likely to be successful if they exclusively targeted grievers displaying marked difficulties adapting to loss. Whilst some of these findings have been challenged (Larson and Hoyt, Reference Larson and Hoyt2007), a consensus seems to be emerging that psychological therapy is more appropriate only for those who experience more severe and enduring grief reactions.

CBT informed models of grief and PGD

A number of models derived from cognitive and behavioural theories have been applied to grief and complicated grief reactions. Malkinson and Ellis (Reference Malkinson, Ellis, Malkinson, Rubin and Witztum2000) developed a rational emotive behaviour therapy (REBT) model for grief-related conditions. The approach identifies ‘irrational beliefs’ and teaches clients to practise more adaptive thinking about their loss whilst maintaining bonds with the deceased. Other CBT based complicated grief treatments are derived from treatments for disorders, such as depression and PTSD. Behavioural activation (BA) has been adapted for complicated grief (Papa et al., Reference Papa, Rummel, Garrison-Diehn and Sewell2013a) from the BA protocol for depression and includes completing a functional assessment to identify the links between symptoms and behaviours. This approach advocates self-monitoring via activity records, identifying avoidant behaviours related to maladaptive ‘grief loops’ and implementing alternative behavioural responses (Papa et al., Reference Papa, Sewall, Garrison-Diehn and Rummel2013b). Treatment components from CBT models for PTSD have been applied with good effect to complicated grief; for example, imaginal exposure was used successfully to enable veterans to engage with traumatic grief memories, and to learn that they were able to tolerate associated distressing emotions (Steenkamp et al., Reference Steenkamp, Litz, Gray, Lebowitz, Nash, Conoscenti, Amidson and Lang2011). Boelen and colleagues (Reference Boelen, van den Hout and van den Bout2006) developed a CBT-based treatment for complicated grief, which combines exposure and cognitive restructuring components, similar to the core elements of the cognitive model for PTSD (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). Other models for complicated grief have been developed from different therapeutic modalities. Shear and colleagues (Reference Shear, Frank, Houck and Reynolds2005) have designed a manualised complicated grief therapy (CGT) integrating components of cognitive behavioural therapy for PTSD with elements of interpersonal psychotherapy for depression.

Evidence for CBT models of PGD

A Cochrane protocol for a systematic review of CBT therapies for PGD has been published and will provide a more in-depth analysis of the current evidence base for CBT-based therapies for PGD and bereavement-related PTSD and MDD (Roulston et al., Reference Roulston, Clarke, Donnelly, Candy, McGaughey, Keegan and Duffy2018). Within the limited scope of this paper, we can state that the evidence base for CBT-based models is developing and encouraging. For example, Boelen et al. (Reference Boelen, de Keijser, van den Hout and van den Bout2007) compared two CBT interventions (exposure therapy and cognitive restructuring) with supportive counselling and found that both CBT interventions were more effective than supportive counselling. In one meta-analysis of psychological therapy randomised controlled trials (RCTs) for adults with PGD, Wittouck et al. (2011) concluded that cognitive behavioural grief interventions were more effective than control conditions (supportive or other non-specific therapy, or waitlist).

Several RCTs that compared interventions comprised of CBT components with wait list have reported significant between-group differences in PGD symptoms post-treatment (Barbosa et al., Reference Barbosa, Sa and Carlos Rocha2014; Eisma et al., Reference Eisma, Boelen, van den Bout, Stroebe, Schut, Lancee and Stroebe2015; Papa et al., Reference Papa, Sewall, Garrison-Diehn and Rummel2013b; Rosner et al., Reference Rosner, Bartl, Kotoucova and Hagl2015). However, two items of concern emerge from these studies. First, end-of-treatment gains diminish at follow-up and secondly, non-completer rates are high. For example, Eisma et al. (Reference Eisma, Boelen, van den Bout, Stroebe, Schut, Lancee and Stroebe2015) reported that a third dropped out from their trial exposure group and 59% did not complete therapy in the BA treatment arm of the study. Similar high non-completer rates were reported in a trial by Shear et al. (Reference Shear, Reynolds, Simon, Zisook, Wang, Mauro, Duan, Lebowitz and Skritskaya2016) in a study combining medication and psychological treatments. Twenty-six percent non-completers were reported in the psychological therapy arm (CGT group) and overall a 37.5% loss was reported for the 6-month follow-up data point. Clearly it is undesirable that substantial proportions of participants do not complete therapy.

(4) Can cognitive therapy for PTSD help with these conditions, or are different techniques and skills required?

PTSD vs PGD

To answer this question, it is important to be aware of the symptoms where PTSD and PGD overlap and where these disorders fundamentally differ. Common characteristics include: a sense of being stunned or shocked (by the trauma in PTSD and by loss in PGD), emotional numbing, intrusive memories and thoughts, avoidance of reminders, survivor’s guilt, feeling detached from others, and intense emotions with significant functional impairments (Rando, Reference Rando1993). A number of researchers have reported important differences between PGD and PTSD (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Dickstein, Maguen, Neria and Litz2012; Shear et al., Reference Shear, Frank, Houck and Reynolds2005). The primary emotions in PTSD are usually fear, anger, guilt or shame depending on the dominant appraisals, whereas in PGD the primary emotional response is usually intense sadness and yearning. Intrusions are common to both disorders, but in PTSD, are associated with the traumatic event and involve a sense of external threat or threat to the sense of self, whilst in PGD intrusions concern the deceased and predominantly involve a sense of loss. In PTSD individuals avoid reminders linked to the traumatic event, whereas in PGD, avoidance is linked to reminders of the reality or permanence of the loss. In PTSD, sensory cues such as sounds, colours or smells that match the past trauma, trigger intrusive memories (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). In PGD, a wide range of reminders of the deceased are commonly present, rather than being limited to the circumstances of the loved one’s death. It is important to differentiate between triggers for distressing traumatic intrusions of how the person died and triggers that induce loss-related memories in order to apply the most appropriate therapy techniques. As an example, the stimulus discrimination technique derived from CT-PTSD is effective in discriminating between the trauma then, and triggers in the present now that bring to mind the traumatic memory, whereas the technique of ‘postponing and containing remembering periods’, commonly used in CBT for depression, can be helpful to apply to loss-related memories associated with long periods of rumination about life without the deceased.

Some researchers have reported that the hyperarousal and exaggerated reactivity common in PTSD is not typically reported with complex grief reactions (Jordan and Litz, Reference Jordan and Litz2014). However, in our clinical experience, PTSD symptoms, such as hyper-vigilance, can be present in PGD, especially amongst parents who lose a child in sudden traumatic circumstances (either accidental or violent traumas). In such cases, bereaved parents can become hyper-vigilant in relation to protecting their surviving children. It is important to discover the specific appraisals linked with these behaviours which usually relate to the theme of over-generalised and exaggerated threat. Techniques, such as behavioural experiments, used in CT-PTSD to test and then update appraisals linked to an over-generalised sense of danger can then be applied.

Over-arching cognitive theme and maintenance of PGD

One of the important advances in psychological therapy in recent times has been the development of disorder-specific cognitive models to conceptualise a patient’s condition (Clark, Reference Clark1999). At the core of these models is a central cognitive theme linked to the particular disorder, which helps to guide therapy by focusing on beliefs and behaviours that relate to the central theme. As an example, Ehlers and Clark (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) discovered that the central theme in PTSD is a sense of serious current threat, maintained by a disjointed trauma memory, unhelpful behaviours and excessively negative appraisals. Ehlers (2006) posed the question: is there a similar over-arching cognitive theme relating to PGD or are there separate themes for separation distress and traumatic distress? In this respect, like PTSD, a sense of threat may be present with PGD but relates to being unable to face a life without the deceased. Thus, the world and the future after loss may seem threatening. However, the core theme in PGD is likely to be one of loss and in this respect attachment theory may be helpful in understanding the concept of yearning that is central to PGD (Bowlby and Parkes, Reference Bowlby, Parkes and Anthony1970). The nature of the relationship to the deceased, for example parenthood, can help explain how certain types of bereavement, particularly child loss, have been found to be a strong predictor of chronic, severe and enduring grief (Meert et al., Reference Meert, Shear, Newth, Harrison, Berger, Zimmerman, Anand, Carcillo, Donaldson, Dean, Willson and Nicholson2011; Sveen et al., Reference Sveen, Bergh Johannesson, Cernvall and Arnberg2018; Smith and Ehlers, Reference Smith and Ehlers2020). However, the type of relationship as a single variable does not adequately explain why some bereaved relatives develop PGD and others do not. In our clinical experiences with many bereaved victims including large scale tragedies such as the Omagh bombing, the relationship to the deceased did not adequately differentiate between those who were able to adapt to their loss and those who developed prolonged grief reactions.

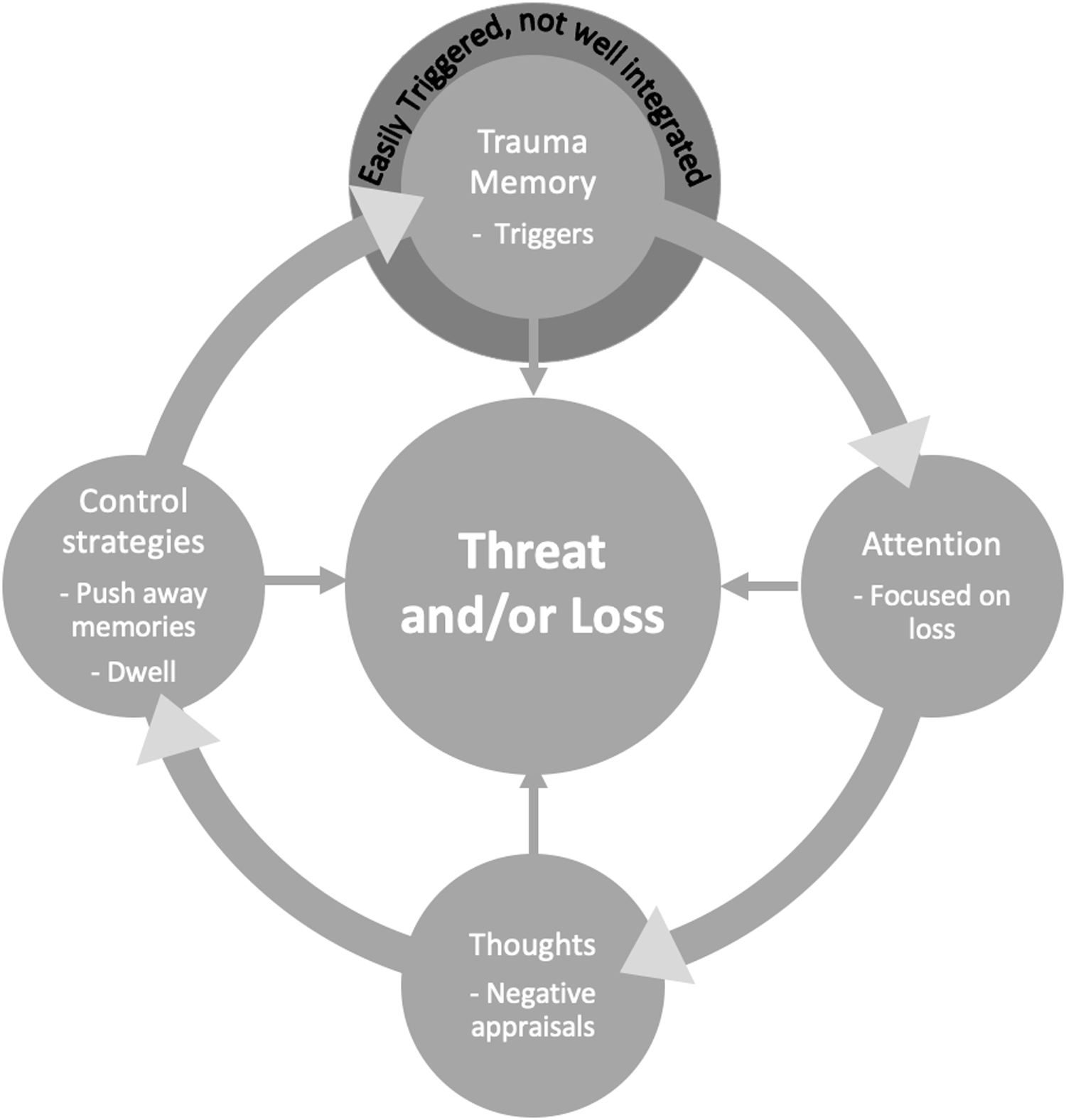

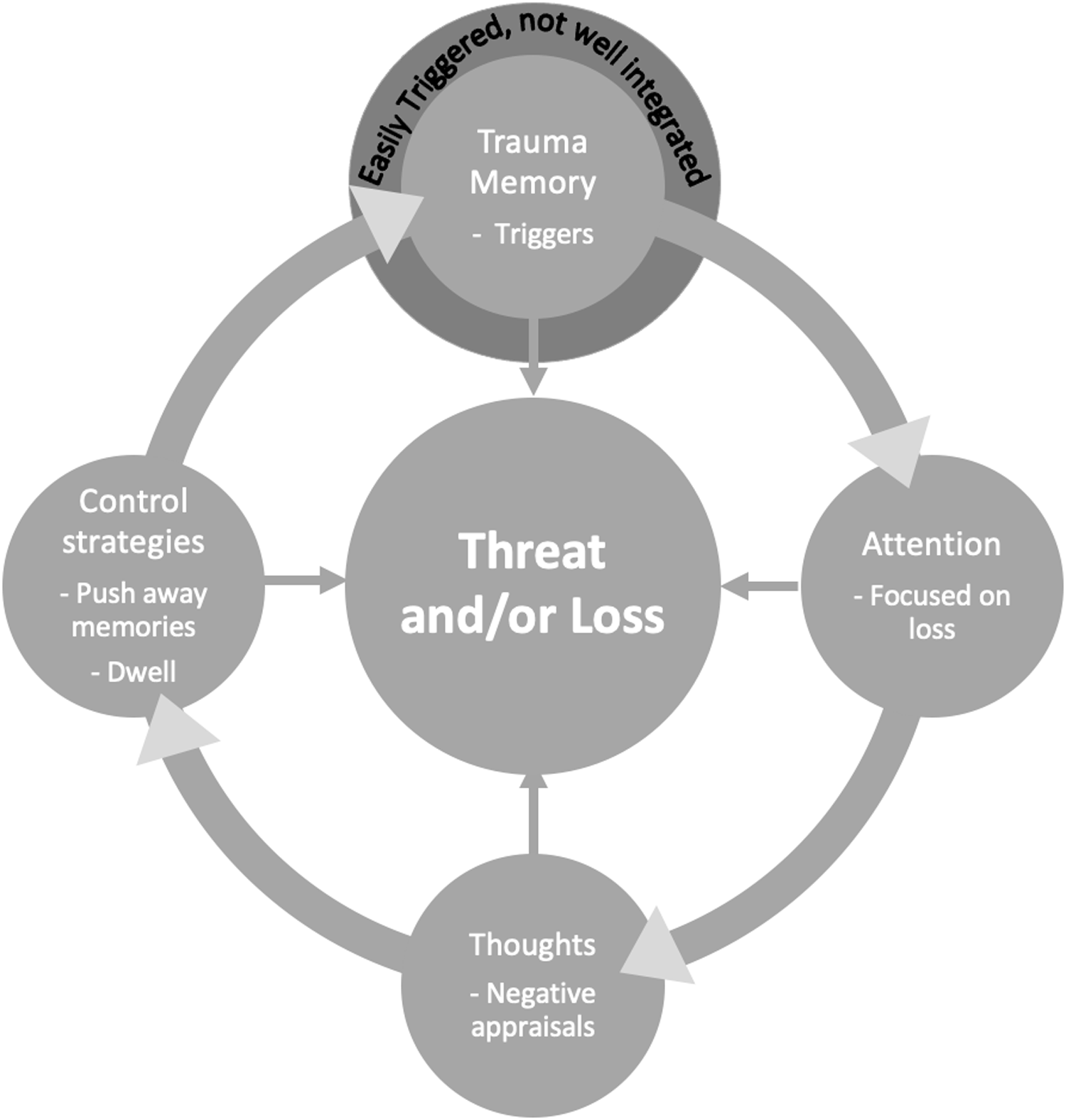

We apply the cognitive model of PTSD (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) to conceptualise maintenance factors and therapy targets for PGD. The CT-PTSD model emphasises the important maintenance role of negative appraisals, unhelpful coping strategies, and characteristics of the trauma memory. We have found in our clinical practice with PGD that many of these strategies keep the patient’s attention focused on loss, and so we take this into account in the following simplified cycle (Fig. 1) that we share with patients.

Figure 1. A cycle of prolonged grief disorder for clinical practice.

Memory and appraisals

Activation of and attention to loss memories

In the cycle of prolonged grief disorder depicted in Fig. 1, the traumatic memory of loss is not well integrated with other autobiographical memories. It is easily activated by reminders of the loved one in the patient’s environment, giving rise to a strong sense of loss. Trauma triggers which bring to mind the memory of how the patient’s loved one died may be relevant for some patients, engendering a sense of threat. The triggers keep the memory active in the patient’s mind. Negative appraisals about the memory and the meaning of the loss maintain the patient’s sense of loss and for some, threat. In response, the patient may engage in behaviours to feel less distressed. These behaviours, such as frequent visits to their loved one’s grave or reducing contact with friends, keep their attention on loss and maintain their distress. If they do engage in new activities, they typically focus on the absence of their loved one, maintaining their focus on loss. Or they may engage in safety-seeking behaviours to reduce the sense of danger, such as checking the safety of surviving children, which keeps their focus on threat. The patient may ruminate about why their loved one died or make efforts to push memories of their death out of their mind, which keep such thoughts in mind for longer. These strategies focus the patient on loss as well as, for some patients, on threat, and prevent the traumatic loss memory from being better integrated with autobiographical memories. This makes it difficult to access memories from before the loss and difficult to move forward with the loss. Thus, treatment will help the patient to shift their focus and work with the thoughts, strategies and the memory which are keeping their grief in place so that they may move forward with loss rather than feeling stuck in it.

Appraisals and coping strategies

A number of studies support the role of negative appraisals in the maintenance of prolonged grief (Boelen et al., Reference Boelen, van den Hout and van den Bout2006; Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Wortman, Lehman, Tweed, Haring, Sonnega and Nesse2002). Smith and Ehlers (Reference Smith and Ehlers2021) found that loss-related memory characteristics, such as struggling to remember positive times without the deceased, and negative grief appraisals, such as believing that letting go of grief would betray the person who died, predicted grief symptoms in the first 6 months after bereavement. Negative appraisals and unhelpful coping strategies, such as grief rumination or proximity seeking, predicted lower levels of adaptation to loss. Some studies have reported that appraisals of injustice such as a pre-occupation with unfairness of the death or the deceased’s lost opportunities in life, are associated with prolonged grief responses (Rees et al., Reference Rees, Tay, Savio, Maria Da Costa and Silove2017; Tay et al., Reference Tay, Rees, Chen, Kareth and Silove2015). Smith and colleagues (Reference Smith, Wild and Ehlers2020) found that particular appraisals about social disconnection (negative interpretation of others’ reactions to grief expression, an alteration of the social self, and perceptions of being safer in solitude) predicted the severity of symptoms of prolonged grief disorder. Such appraisals lead to specific strategies which inhibit the loss memory from being more fully integrated into the autobiographical memory base. Control strategies, such as rumination and avoidance, are common and will be discussed in more detail by the authors in a clinical practice paper on traumatic bereavement (Wild et al., Reference Wild, Duffy and Ehlersin press).

Elaboration of loss memories as a treatment approach

Similar to TF-CT for PTSD (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000), a key goal of therapy for prolonged grief is to elaborate the trauma memory associated with the death (see Smith and Ehlers, Reference Smith and Ehlers2020a, Reference Smith and Ehlers2020b). Thus, the traumatic loss becomes integrated with information pre- and post-traumatic death, and memories of the deceased or the death are contextualised and connected to replace intrusions with intentionally retrievable memories (see Smith et al., Reference Smith, Wild and Ehlers2022). Creating a sense of continuity with the meaning of the loved one is a core component of treatment that seems to help the patient to move forward with their grief, and is discussed in detail in our clinical paper on how to treat PTSD arising from traumatic bereavement (Wild et al., Reference Wild, Duffy and Ehlersin press). The therapist and patient work together to spot the meaning of what the patient has lost and aim to bring that meaning back into their lives whilst recognising what they have not lost. In doing so, the therapy helps patients to create a new relationship to loss. It is no longer about letting go or saying good-bye to their loved one. Rather, it is about how to take their loved one forward with them in an abstract yet meaningful way. One father whose son was killed, missed his son’s gentle manner. As a means of carrying his son’s memory with him, he intentionally became more self-aware of how he interacted with his pupils as a teacher. He quite purposively showed more empathy and interest in their well-being and would smile as he could hear his son say ‘well done Dad’. A mother said that when her daughter was well, she was incredibly supportive. She believed this quality best represented her daughter. She set up a website for survivors of suicide to exchange support. In creating a supportive environment for others, she carried the meaning of her daughter forwards.

Conclusions

The cognitive model for PTSD has been a helpful starting point for conceptualising and treating prolonged, complicated and traumatic grief reactions and indeed our previous trials for PTSD have included numerous patients who were traumatically bereaved (Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Bolton, Gillespie, Ehlers and Clark2013; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Hackmann, Grey, Wild, Liness, Albert, Deale, Stott and Clark2014; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Wild, Stott, Warnock-Parkes, Grey and Clark2022). In this paper we have answered questions posed by workshop participants and considered historical and theoretical concepts relating to PGD. In doing so, we have highlighted components of a CBT model of PGD. We have provided a theoretical and empirical rationale for applying the cognitive model of PTSD (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) to guide our conceptualisation of maintaining factors relevant to prolonged grief disorder. We have focused on, for example: understanding the importance of specific triggers (i.e. loss-related vs trauma memory triggers); recognising the importance of appraisals and behaviours (e.g. social withdrawal), and cognitive processes (e.g. rumination, attention) that maintain traumatic grief symptoms and which appear to disrupt the integration of the loss memory with the patient’s broader autobiographical memories.

We have presented a clinical cycle used with our clients to help them make sense of their post-loss distress and to illustrate what treatment will target. One of the core aims of CT-PTSD, as applied to traumatic grief, is to help the patient update the relationship to their loss memory, such that they can move forward with the meaning of their loved one in their lives. A more detailed discussion on how to treat PTSD and co-morbid grief arising from traumatic bereavement can be found in our clinical practice paper on moving forward with the loss of a loved one (Wild et al., Reference Wild, Duffy and Ehlersin press).

Data availability statement

No new data are presented.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Professor Anke Ehlers for sharing her clinical insights on PTSD arising from loss trauma, valuable theoretical discussions and as always, her exquisite expertise in linking theory to practice. The authors extend heartfelt thanks to the many patients they have had the privilege to work with on their recovery from PTSD as they move forward with the loss in their lives

Author contributions

Michael Duffy: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Jennifer Wild: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

J.W.’s research is supported by MQ, the Wellcome Trust (00070), NIHR Applied Research Collaboration Oxford and Thames Valley, and the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.