New Ways of Working is about supporting and enabling consultant psychiatrists, among others, to deliver effective and person-centred care. Work on New Ways of Working started in 2003 when two national conferences for consultant psychiatrists (in March and April 2003) summarised the problems in the profession - significant difficulties in recruiting and retaining consultant psychiatrists because of the increasing demands of the role, increasing degrees of burnout among consultants, unsustainably high case-loads and crippling expenditure on agency locum doctors to try and plug the gaps. The National Steering Group, jointly chaired by the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the National Institute for Mental Health in England (NIMHE) explored and reviewed the role of psychiatrists and their interface with other mental health professionals. 1 The NIMHE, the Department of Health and the Royal College of Psychiatrists jointly set up the New Ways of Working initiative to address these concerns.

One key aspect of New Ways of Working was the modification of the consultant psychiatrist's job as an in-patient specialist or ‘working across the acute care pathway in crisis and in-patient work’. 2 Many National Health Service (NHS) trusts have developed these roles as a part of the so-called ‘functional model’ in at least part of their area. 2 The functional model includes many changes, but its core feature is that consultants work either on the in-patient or the community side, with one specialist team rather than in the old-styled geographical sectors. Closely related to this functional division is the status of in-patient psychiatry. Currently, acute psychiatric in-patient care is one of the top priorities. 3 Recently there has been a lot of debate about acute in-patient psychiatry being a separate subspecialty, which needs a set of expertise and skills different from that of community psychiatry. Reference Middleton4 It is argued that there should be a dedicated medical team exclusively for in-patient care. Success stories of such arrangements do exist, Reference Dratcu, Grandison and Adkin5,Reference Dratcu6 however this approach is far from unopposed. Reference Holloway7

Regardless of the subspecialty status of acute in-patient psychiatry, the provision of separate consultants to deliver mental health services in the community and in-patient settings is increasingly being accepted across the NHS. From the perspectives of the service users and carers, the practical implication is that the responsibility for a patient's care will shuttle between two consultants with each admission and discharge. This is different from the traditional approach in which the same consultant was responsible for a patient both in and out of hospital (geographical sectorised model). This arrangement was initially adopted in places such as Leeds, Newcastle and Norwich, and was later followed elsewhere. People have expressed their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with this change for various reasons. Although it is too early to decide on the actual impact of this change, this study explores the views of mental health professionals, general practitioners (GPs) and service users on this component of New Ways of Working.

Method

The aim of this study was to investigate health professionals', service users' and carers' opinions about the provision of separate consultants for in-patient settings and the community through a semi-qualitative survey.

Design

This was a multicentre survey covering three NHS sites: North Hertfordshire; the south lakes region of Cumbria; and Winchester. A semi-structured questionnaire was developed to collect both the objective and descriptive (qualitative) opinions of the respondents, including their experience and expectations. The responses to objective questions, as listed in Table 1, needed one of the three choices: improvement, worsening or no effect as a result of this change. Descriptive responses were invited to explore their opinion on the need for this change, its long-term future, their satisfaction, the advantages and disadvantages of this change, suggestions for improvements, the effect on the clinical skills of consultants and on the training of junior doctors, and their opinion on the separate subspeciality status of in-patient psychiatry. The last three items and objective questions 9-14 (Table 1) were considered to be inappropriate for service users and so were not asked of them. The participants were also given an information leaflet that included a brief description about the provision of separate consultants, the need for this study, informed consent and the anonymity of the responses. It did not include any information that could have biased the responses. An online version was also developed for those professionals who could be accessed by email.

Table 1 Opinion of the participants: quantitative data

| Service providers (n = 114) | Service users (n = 43)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Favouring change, n (%) | Against the change, n (%) | No effect, n (%) | Favouring change, n (%) | Against the change, n (%) | No effect, n (%) |

| 1. Quality and appropriateness of care while in-patient | 31 (27.2) | 28 (24.6) | 55 (48.2) | 10 (25) | 9 (22.5) | 21 (52.5) |

| 2. Duration of stay in the hospital while in-patient in an episode | 46 (40.4) | 20 (17.5) | 48 (42.1) | 15 (38.5) | 7 (18) | 17 (43.5) |

| 3. Frequency or need of unplanned contact with services/crisis team (e.g. accident and emergency) | 22 (19.3) | 52 (45.6) | 40 (35.1) | 12 (31) | 9 (23) | 18 (46) |

| 4. Continuity of care and therapeutic alliance | 20 (17.5) | 82 (72) | 12 (10.5) | 11 (27.5) | 14 (35) | 15 (37.5) |

| 5. Quality and appropriateness of care in community | 28 (24.6) | 32 (28.1) | 54 (47.3) | 12 (28.5) | 12 (28.5) | 18 (43) |

| 6. Frequency or need of admission for an individual patient | 24 (21) | 28 (24.6) | 62 (54.4) | 13 (30) | 8 (19) | 22 (51) |

| 7. Patient's adherence with treatment plan | 18 (15.8) | 48 (42.1) | 48 (42.1) | 11 (27) | 7 (17) | 23 (56) |

| 8. Patient's satisfaction with the services or the treatment | 21 (18.4) | 78 (68.4) | 15 (13.2) | 8 (20.5) | 11 (28) | 20 (51.5) |

| 9. Carer's satisfaction with the services and treatment | 23 (20.2) | 72 (63.2) | 19 (16.6) | |||

| 10. Course and prognosis of mental illness | 24 (21) | 49 (43) | 41 (36) | |||

| 11. Risk to self/others/property | 13 (11.4) | 40 (35.1) | 61 (53.5) | |||

| 12. Cost-effectiveness of care/treatment | 38 (33.4) | 32 (28) | 44 (38.6) | |||

| 13. Clinical skills of psychiatristb | 14 (14.6) | 38 (39.6) | 44 (45.8) | |||

| 14. Quality of training of junior doctors in psychiatryb | 16 (16.7) | 32 (33.3) | 48 (50) | |||

The responses were collected personally, by post and online. An email was sent to all mental health professionals at each study site inviting them to participate in the survey. It included an information sheet and a link to the online questionnaire. A reminder was sent after a month to increase the response rate. We contacted the service users and carers through community mental health team (CMHT) centres, out-patient clinics, mental health units and other places (e.g. the local centre of MIND). They were given a choice of giving their responses personally or sending them by post using a pre-addressed, pre-stamped envelope. Actively unwell or admitted patients were not approached as their participation in the survey may have caused them undue distress and their opinion could have been biased. We liaised with receptionists, team leaders and care-coordinators to facilitate the process.

Analysis

We analysed the quantitative data with descriptive statistics. A framework analytic process was used to qualitatively analyse descriptive responses and identify the key issues and themes. Framework analysis is now increasingly used in applied health policy and social research. Reference Ritchie, Spencer, O'Connor, Ritchie and Lewis8 Unfortunately, the responses from carers were too few to be included in the final analysis.

Results

Quantitative data

Service providers

A total of 330 professionals (85 from mental health and 25 GPs from each site) were invited to participate in the survey; 170 responded giving a response rate of 52.2% for mental health professionals and 49.3% for GPs. Fifty-six participants only completed the introductory questions. Out of the remaining 114, 96 participants responded to questions 13 and 14 (Table 1).

In general, participants were quite experienced with approximately 72% participants having more than 6 years experience in mental health. The respondents included GPs (n = 37), community psychiatric nurses (n = 34), psychiatrists (n = 30), social workers (n = 23), staff nurses (n = 12), support workers and managers (n = 7 each), occupational therapists (n = 3), psychologists (n = 2) and others (n = 15). The breakdown of work settings was as follows: CMHT (n = 63), primary care (n = 37), in-patient units (n = 35), crisis team (n = 19), assertive outreach team (n = 10), liaison (n = 2), substance misuse (n = 2) and other (n = 2).

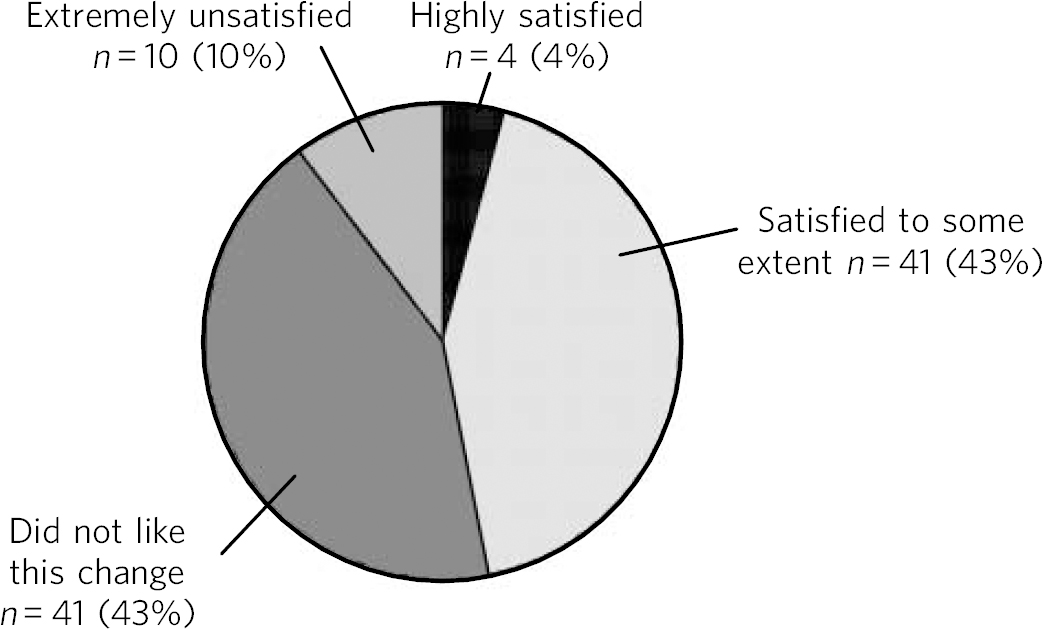

Interestingly, 36 (21.2%) participants were unaware of these changes in service delivery, most of whom were GPs. The responses are summarised in Table 1. Out of 96 respondents, 47 believed that this change was needed, with the other 49 opposing the idea. Two-thirds of the respondents (n = 66) felt that the new system would probably continue, whereas according to the rest (n = 30) it is likely to go back to the old system with the same consultant managing patients in both the settings. Figure 1 shows that the level of satisfaction with this change was evenly divided. Regarding the debate about whether in-patient psychiatry and community psychiatry are two separate specialties, an overwhelming majority, 88 (91.7%) were of the view that they are two aspects of the same specialty, whereas 8 respondents considered them to be two different specialties.

Fig 1 Level of service providers' satisfaction with two separate consultants.

Service users

Forty-three service users responded to the survey (although not everyone responded to all the questions). It was not possible to calculate the response rate because of the way responses were collected. Primary diagnoses were: depression (n = 18), anxiety disorders (n = 7), psychosis (n = 6), bipolar disorder (n = 5) and personality disorder (n = 5). Overall, 15 people had been known to the mental health services for 2-5 years, 13 participants for more than 10 years, 8 participants for less than 2 years, and 7 for 6-10 years. Twenty respondents had a history of one or more admissions to a mental health unit.

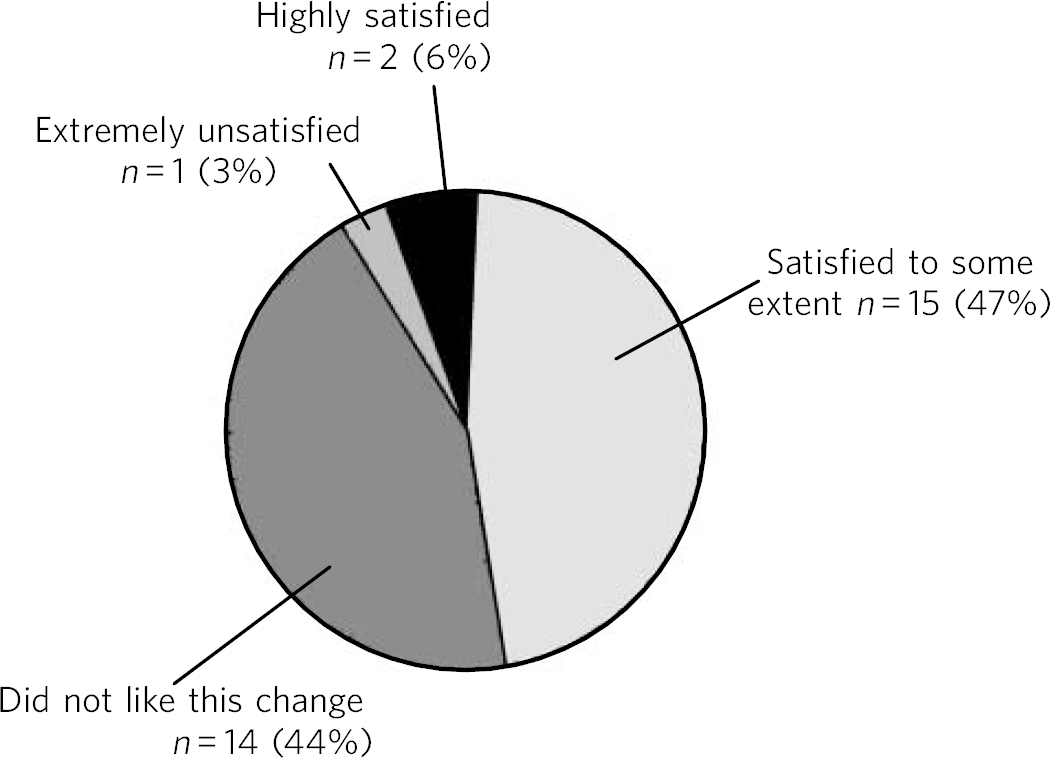

The majority, 27 (64.3%), of the respondents was unaware of these changes in service delivery. Responses are summarised in Table 1 (questions 9-14 were not asked of service users). Figure 2 shows their level of satisfaction with the changes, which almost mirrors that of the service providers.

Fig 2 Level of service users' satisfaction with two separate consultants.

Qualitative data

A total of 96 service providers and 43 service users responded to the descriptive questions. We derived a thematic framework (Fig. 3) based on the overall findings of our survey. This framework illustrates the interplay of various factors and suggestions for improvements. Some of the more interesting comments are summarised in Box 1. Common themes are mentioned below and differences in opinion between service providers and service users, where identified, are mentioned separately.

Fig 3 Thematic framework of qualitative data. NWW, New Ways of Working; CPA, care programme approach.

-

1 Need for this change: most of the participants were either unaware of this change or did not know why it was needed. Common themes included - ‘need to save money and/or time’, ‘a service need rather than a clinical one’, ‘to reduce workload on consultants’ and ‘to improve patient care’.

-

2 Long-term future: about two-thirds of the respondents felt that this change would be permanent. Common themes included - ‘it is driven by financial issues and the constraint in resources will prevent reverting back to the old system’ and ‘it is a positive move which is already working well in London’. The other third thought that it would not work and would be reversed.

-

3 Advantages of this change: service providers think that this change is good for specialisation of doctors in an individual setting and for the empowerment of nursing staff. Service users commented that it would give them a chance to have a second opinion about their management. Although most of the participants identified better in-patient care, saving money and time and a reduction in stress and workload on the consultants as being the main advantages, almost a third of them could not find any advantages to this change.

-

4 Disadvantages of this change: lack of continuity of care, communication breakdown and breakdown in the therapeutic relationship, frustration and stress to the patients (as they would have to repeat their histories and concerns) were reported as the main disadvantages by most of the respondents. Additionally, service users reported other disadvantages such as reduced holistic care, friction and disagreements between consultants, a lesser understanding of the patients and their circumstances by the in-patient consultant and shifting of the responsibility to the other consultant.

-

5 Specialty status of in-patient psychiatry: the vast majority believed that in-patient psychiatry is not a separate specialty as it deals with the same patients but with different intensities of need. Most of the skills required are the same as in community psychiatry.

-

6 Skills of consultants and the training of junior doctors: the most common concern was that the psychiatrists would specialise in the particular sector of their work (in-patient or community) at the cost of becoming deskilled in the other sector. Some respondents commented that the overall skills of the consultants would increase because they would carry out their respective jobs in a more focused manner and would have sufficient time to participate in teaching, management and other non-clinical work. Some respondents felt that, because of the lack of continuity, they would not be able to see the full course of an individual episode resulting in possible deskilling. Very similar responses were given with regard to the training of junior doctors in psychiatry.

-

7 Suggestions and recommendations: several suggestions were put forward to counteract some of the perceived disadvantages. The most common suggestion was to increase the involvement of service users and GPs in making these kinds of changes. Many GPs and service users were unhappy about not being consulted and informed. The respondents also emphasised the need for measures to enhance efficient communication and coordination between the two consultants, such as an active role for care-coordinators in bridging the gap and attendance of both consultants in the care programme approach meetings. Another suggestion was the use of shared electronic records between the mental health services and primary care. Rotation of the consultants' role between in-patient and community settings was also suggested to prevent their deskilling. Similarly, placement in both community and in-patient settings was recommended for psychiatric trainees. Despite these measures, psychiatrists may still not see the full course of an individual episode according to some of the respondents.

Box 1 Some interesting comments by participants

General practitioners

-

• The new system is more patient-centred than the previous one.

-

• Quality and efficiency of the in-patient work has improved, I have had no complaints from patients about the change. Challenges in communication are not insurmountable.

-

• It should change - but towards integrating care with primary care (e.g. community psychiatric nurses attached and working with each practice) and crisis and home treatment teams may be looking after but ultimate care retained by those with longer-term responsibility.

-

• Assessment tools and referral notes are not a substitute for first-hand knowledge of a patient and their circumstances

-

• A recipe for disaster; too many cooks scenario.

-

• Thank you for finally asking us what we think - will it make any difference? GPs should be taken on board before changes.

Mental health professionals

-

• It will help in smooth running of psychiatric wards.

-

• This change is led by financial status of NHS, so is likely to continue.

-

• Likely to improve in-patient and community care individually but discontinuity will offset advantage.

-

• Communication is the key to success.

-

• Exposure of trainees to an illness episode will be fragmented. The sum of the parts will be less than the whole.

Service users

-

• The old system (same consultant) was on paper and we were seeing a different consultant every 3 months anyway.

-

• At last somebody took our opinion.

-

• It will reduce the clinic waiting list.

-

• I don't want it. Go back to how it was.

-

• We do not want to repeat our history again and again. It's hard to build relationships with two consultants.

Discussion

There is a limited evidence base for or against New Ways of Working. A recent survey of psychiatrists in the West Midlands Reference Dale and Milner9 showed that attitudes towards it were generally negative, particularly regarding the effect on patient care, the erosion of the professional role of the consultant and the effect on quality of work life. Some evidence suggests that providing dedicated in-patient consultants has led to demonstrable improvements in the in-patient experience of service users, carers and staff. 2 However, further evidence is required to reach a definitive judgement. Our survey focused on the functional model within New Ways of Working and looked beyond the in-patient experience, providing some useful insights into the expectations and perceived effects of this model in other areas too, including community experience, course and prognosis of the illness, and the training and skills of psychiatrists.

Service users and GPs repeatedly emphasised that they were not informed about this change. This lack of knowledge probably left scope in the participants' minds for speculation about the possible reasons for this change. The driving force for New Ways of Working is the best use of the current workforce but surprisingly few respondents felt that this was the case. The opinion was almost equally divided about whether this change was needed, as was the level of satisfaction among both groups of respondents; however, the issue about specialty status was much clearer. Interestingly, the majority felt that the new system would continue despite a high level of dissatisfaction. Most of the descriptive responses reflected dissatisfaction unlike the quantitative data. The reason for this could well be that the dissatisfied respondents were probably more likely to give a descriptive account of their opinion.

Most of the service providers thought that the course and prognosis of the illness, associated risk and adherence with the treatment plan would either worsen or remain unaffected. Opinions regarding the clinical skills of psychiatrists and quality of training were also similar. Only a minority expressed positive views on these issues. Malik et al Reference Malik, White, Mitchell, Handerson and Oakley10 have also expressed similar concerns about the implications of New Ways of Working on the training of doctors in psychiatry. Opinion was divided on the cost-effectiveness of the new arrangement; although many respondents, particularly GPs and service users, speculated that this was a money-saving exercise (which is actually not the case according to the New Ways of Working progress report) 2 and so would most probably continue. The majority of the service providers thought that patients and their carers would not like this change. The opinion about quality and appropriateness of care was fairly divided, with half of the respondents believing that it would not be affected. Most of the respondents expected that the duration of in-patient stay during an episode would either reduce or be unaffected.

One of the most consistent views was that continuity of care, the therapeutic alliance, the doctor-patient relationship and trust would be adversely affected, and this would in turn influence many other aspects. Similar views have been expressed elsewhere previously. Reference Gee11 There are concerns that this discontinuity may be another hole in the net through which some patients may slip. It can be argued that ensuring continuity of care was already a challenge (even before this change was implemented) in the era of multiple teams such as CMHTs, assertive outreach teams, crisis teams, and early intervention in psychosis teams, so this new model may not actually pose additional new problems. Obviously, the role of care-coordinators is going to be increasingly important.

In addition to the well-established pioneering work at Guy's hospital, Reference Dratcu, Grandison and Adkin5 this model has also been evaluated in other places, for example adult mental health services in East Suffolk (where it was adopted as a pilot in 2005) and the results are very encouraging with few reported problems. 12 Our study does not make any inferences with regard to the effectiveness of this model. However, being an exploratory study, it does reflect on how it is perceived by professionals and patients.

Our sample size and response rate were modest and we are therefore reluctant to draw any definitive conclusions. There is always the possibility that those individuals with strong opinions (i.e. highly satisfied or highly dissatisfied people) are more likely to participate in such a survey, so a response bias cannot be ruled out. Similar limitations have also been reported elsewhere. Reference Dale and Milner9 Also, since this change has been introduced only recently, many service users had not actually experienced it yet. Also, as this change was introduced only recently, many service users did not experience being admitted under this new model. Their opinion could have been different had they been admitted under this model before this study. Currently admitted in-patient service users were not included in the study because of their acute illness and their views could have been different. This may have skewed the service user sample to some extent.

Nonetheless, this study serves a very important purpose. It reflects on what people are anticipating as a result of this change, by posing new questions, unveiling some of the flaws in the system and making some useful suggestions. Inclusion of three different geographical areas and different groups of participants increased the validity and generalisability of the findings. This survey is limited in its scope as it concentrated on only one of the provisions of New Ways of Working. New Ways of Working guidance affects almost all mental health professionals and is implemented widely; hence there is a need for a larger nationwide study, involving all affected health professionals, service users and carers. Obviously, a future goal should be to study the ‘actual’ long-term impact of this change.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.