Violence is recognised by the World Health Organization as a major public health priority (World Health Organization 2002). Violence contributes to lifelong ill health and early death from heart disease, stroke, cancer and other illnesses when victims of violence adopt behaviours such as smoking, alcohol and drug misuse to cope with its psychological impact. Violent crime is also associated with negative impacts on health and criminal justice systems, social and welfare services and the wider economy (World Health Organization 2014).

The negative health impact of violent behaviour is not confined to its victims. Those that commit violent crime are themselves at increased risk of developing physical and mental ill health. Personality disorder, most commonly antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), is overrepresented in offending populations (Alwin Reference Alwin, Blackburn and Davidson2006), particularly among individuals with convictions for violent offences (McMurran Reference McMurran and Howard2009). ASPD is associated with high levels of comorbid psychiatric illness, substance misuse, poor physical health and early death from suicide or reckless behaviour (Martin Reference Martin, Cloninger and Guze1985; Black Reference Black, Baumgard and Bell1996; Odgers Reference Odgers, Caspi and Broadbent2007; Piquero Reference Piquero, Shepherd and Shepherd2011). Violent acts may lead to post-traumatic stress disorder in perpetrators as well as victims (Minne Reference Minne, Gordon and Kirtchuk2008). Improving offender health has been designated by the Department of Health as a priority area (Health Inequalities National Support Team 2011).

Most professionals in any field of mental health will be exposed to violence at some point in their working life. For those who work in forensic settings, the assessment and management of risk of violence are, of course, their bread and butter, and some may also be involved in applying specific therapeutic interventions and programmes aimed at reducing violent behaviour. However, professionals in all mental health settings are at increased risk of being direct victims of violence from patients, and some work in institutions in which pathological organisational dynamics contribute to an environment of violence and fear.

Although psychoanalysts have contributed to a vast literature on aggression since Freud first wrote about the subject, psychoanalytic practice is not usually associated with violent behaviour, which is seen by most as a contraindication for therapy. However, a psychoanalytic or psychodynamic approachFootnote a may complement and enhance, although not replace, predominant theories of violence from other disciplines such as criminology, sociology and forensic psychiatry (Yakeley Reference Yakeley2010).

In this article I will highlight some of the key principles underpinning a psychodynamic framework in which to understand the aetiology and psychological development of violent and antisocial behaviour, and to assist in their management in a multidisciplinary setting. Psychoanalytic concepts such as acting out, containment, transference and countertransference will be explored in relation to understanding the causes and consequences of violence within this framework (Box 1). A psychodynamic approach to aggression and violence may help to inform risk assessment and therapeutic interventions for violent individuals.

Box 1 Psychoanalytic concepts

Acting out Expressing an unconscious wish or fantasy through impulsive action as a way of avoiding experiencing painful affects.

Countertransference Feelings and emotional reactions of the therapist towards the patient resulting from both unresolved conflicts in the therapist and the projections of the patient.

Introjection The process of internalising the qualities of an object. Introjection is essential to normal early development, but can also be a primitive defence mechanism in which the distinction between subject and object is blurred.

Mentalisation A focus on mental states in oneself and others, recognising desires, needs, feelings, beliefs and reasons, especially in explanations of behaviour. Normal mentalisation develops in the first few years of life in the context of safe and secure attachment relationships.

Object Significant person in the individual's environment, the first significant object usually being the mother.

Object relationship The individual's mode of relation to the world, determined by the child's experience, perceptions and fantasies about their relationships with significant caregivers becoming incorporated in the mind at an early stage of development to become prototypical mental constructs which influence the individual's mode of relating to others in adulthood.

Projection Primitive defence mechanism in which unacceptable aspects of the self are expelled and attributed to someone or something else.

Projective identification Projection (as above), but a more powerful unconscious defence in which the person who has been invested with the individual's unwanted aspects may unconsciously identify with what has been projected into them and may feel unconsciously pressurised to act in some way.

Splitting Primitive defence mechanism in which incompatible and polarised experiences of self and other are kept apart to prevent conflict.

Superego Structure in the mind formed by the child's internalisation of parental standards and goals to establish the individual's moral conscience.

Early psychoanalytic theories of aggression

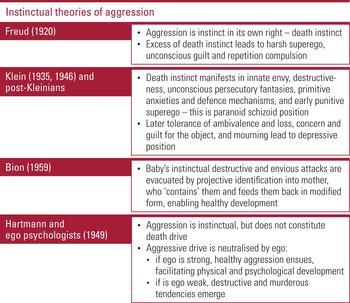

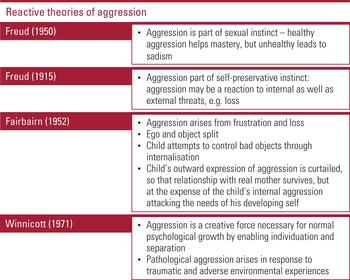

Psychoanalysts have had a lot to say on the nature of aggression since Freud first posited the existence of the death instinct (thanatos), an innate destructive force that operates insidiously in opposition to the life instinct (eros) (Freud Reference Freud and Strachey1920). The death instinct, however, represented the last of his partial theories, which were never completed, on the fate of aggressive instincts in the individual; prior to this he had located aggression first as a component of the sexual instinct used in the service of mastery (Freud Reference Freud and Strachey1905) and then within the self-preservative instincts, where aggression was a response to both internal and external threats, such as loss (Freud Reference Freud and Strachey1915, Reference Freud and Strachey1917). Subsequent early analytic writers on aggression tended to elaborate particular aspects of Freud's thinking at the expense of building a coherent and comprehensive theory. They may be divided into those who viewed aggression as an instinct, such as Melanie Klein and Wilfred Bion in the UK and Heinz Hartmann and ego psychologists in the USA (Fig. 1), and those who saw it as reactive to environmental traumas and deprivations, such as Donald Winnicott and Ronald Fairbairn (Fig. 2).

FIG 1 Instinctual theories of aggression.

FIG 2 Reactive theories of aggression.

Klein furthered Freud's concept of the death instinct by emphasising the instinctual origins of aggression. She believed that envy and destructiveness were manifestations of the death instinct and predominated in early life, giving rise to persecutory anxieties and primitive defences, unconscious fantasies and an archaic superego, all of which formed the ‘paranoid schizoid’ position (Klein Reference Klein1946). This gradually develops into the more mature ‘depressive position’ with the tolerance of loss and ambivalence (Klein Reference Klein1935). Winnicott (Reference Winnicott1971), by contrast, saw aggression as a creative influence necessary for normal psychological growth, enabling individuation and separation; pathological aggression and violence arose in response to traumatic and adverse experiences.

This polarisation of constitutional or instinctual versus environmental or reactive theories of aggression has been mirrored in more recent debates regarding the relative strength of genetic versus psychosocial factors in the genesis of pathological violence. Within contemporary psychoanalytic thought, a more balanced approach has emerged embracing both biology and psychology, recognising that although the capacity for aggression is innate and universal, aggressive behaviour occurs in response to threats that the self perceives in relation to internal or external objects. Furthermore, there may be different types of aggression, which are exhibited in different forms of violence.

A typology of violence

Violence is distinguished from aggression by being a behaviour that involves the body. Glasser (Reference Glasser1998) defined violence as an actual assault on the body of one person by another, involving penetration of the body barrier, ‘the intended infliction of bodily harm on another person’. Violence is also an interpersonal phenomenon, involving bodies and minds. De Zulueta (Reference De Zulueta1994) defined violence as a form of interpersonal human behaviour in which a thinking ‘subject’ is doing something destructive to an ‘other’ human. A psychoanalytic approach focuses on exploring the mind of the violent person, who communicates via bodily action motivated by internal and external object relationships.

It is widely recognised that there are at least two different forms of human violence, underpinned by different neurophysiological pathways (Meloy Reference Meloy1992). Affective violence is an immediate defensive reaction in which the person mounts a ‘fight or flight’ response to a perceived threat, and it involves activation of the autonomic nervous system, resulting in a state of high arousal and anxiety. By contrast, instrumental or predatory violence lacks emotional involvement: it is purposeful and calculating and characterised by a lack of empathy for the victim. Such violence is more common in people with prominent psychopathic traits. A bimodal distribution of violence has been supported empirically by physiological (Stanford Reference Stanford, Houston and Mathias2003), psychopharmacological (Barratt Reference Barratt, Stanford and Felthous1997) and neuroimaging (Raine Reference Raine, Meloy and Bihrle1998) studies.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, Glasser (Reference Glasser1998) proposed a similar typology in distinguishing what he called ‘self-preservative’ violence from ‘sadomasochistic’ violence. Self-preservative violence corresponds to affective violence, and is a primitive response triggered by any perceived threat to the physical or psychological self. Such threats might be external, such as attacks on the person's self-esteem, frustration, or feeling humiliated or insulted. The person can also feel threatened by internal sources, such as feelings of disintegration and internal confusion that might occur in psychosis. The violent response is immediate and aimed at eliminating the source of danger. Sadomasochistic violence is similar to predatory or instrumental violence. Glasser proposed that sadomasochistic violence is derived from self-preservative violence via an unconscious process of sexualisation.

The main difference between these two forms of violence involves their relationship to the object (i.e. the person towards whom the violence is directed). In self-preservative violence, the object is perceived as being of immediate danger and must be eliminated, but holds no other personal significance for the perpetrator. By contrast, in sadomasochistic violence the object and its responses are of great interest to the perpetrator. The object must be made to suffer, but must be kept alive in order to achieve this. Sadomasochistic violence also involves sadistic pleasure, which is not a component of self-preservative violence, where anxiety is always present (Table 1).

TABLE 1 Two types of violence

The difference between the two types of violence may be illustrated on the one hand by the soldier who kills the enemy in a battle to prevent himself from being killed (self-preservative violence), and on the other hand by the soldier who captures the enemy and tortures him to make him suffer (sadomasochistic violence).

The role of the object, the interpersonal world and the core complex

Many individuals with violent and antisocial behaviour report histories of neglect, rejection and abuse, dysfunctional family relationships, time spent in care or other traumatic childhood experiences. How may we understand from a psychodynamic perspective how these early adversities and disrupted relationships contribute to the development of pathological aggression and violence?

Many psychoanalytic writers on aggression and violence locate the origins of violence in a pathological early relationship between mother and infant, where the mother is more concerned with her own needs than those of her child. The mother may be experienced as neglectful, or overwhelming and intrusive, but in either case the child is prevented from developing a sense of separate identity and uses aggression as a desperate measure to create space between self and m/other. The inner world of the child is populated with primitive unconscious fantasies of a maternal object that is engulfing and obliterating, and violence is seen as an unconscious fantasised attack on the mother's body (Fonagy Reference Fonagy and Target1995; Perelberg Reference Perelberg1995; Bateman Reference Bateman and Perelberg1999; Campbell Reference Campbell and Perelberg1999).

Glasser (Reference Glasser and Rosen1996) also considered the relationship to the mother to be fundamental in the genesis of aggression and violence in his concept of the ‘core complex’. This refers to a particular unconscious constellation of interrelated feelings, ideas and attitudes, a major component of which is a deep-seated and pervasive longing for an intense and intimate closeness to another person. Such longings occur in all of us, but where there has been an early relationship to a narcissistic mother, who prioritises her own needs over her child's, they persist as primitive unconscious persecutory anxieties unmodified by later stages of development. The person wishes to merge and achieve a ‘state of oneness’ or a ‘blissful union’ with a significant other, but these wishes develop into fears of a permanent loss of self, an annihilation of existence, an engulfment by the object. To defend against this annihilatory anxiety, the person retreats to a ‘safe distance’ from the object. But this provokes painful feelings of emotional isolation, rejection and abandonment, which prompt the desire for contact and union with the object again, so that the person is caught up in a vicious circle in which no satisfactory emotional contact can be sustained.

One ‘solution’ that the child may resort to is to mount an aggressive response to the unconscious fantasies of annihilation and experience of being overwhelmed by the object – usually the mother at this very early developmental stage – who must be destroyed so that the infant survives. But this would lead to the loss of any security, love and warmth that she offers. At this point the infant has two options – to withdraw into a narcissistic state to protect the mother, but at the expense of the development of the infant's nascent self, or to resort to aggression towards the mother to preserve the self. Glasser proposed that this was the origin of self-preservative violence. Sadomasochistic violence may emerge at a later stage in development by converting self-preservative aggression into sadism. This resolves the vicious circle of the core complex, as the mother/object is not destroyed but survives to be manipulated and controlled by the child.

Distinguishing between these two types of violence, and the underlying associated anxieties of the core complex, may be important in risk assessment. Self-preservative violence is more likely to be triggered by persecutory feelings of being engulfed and intruded upon, whereas sadomasochistic violence is triggered by fears of being abandoned by the object. These conflicting anxieties, which provoke the defensive reactions of the core complex, may be heightened by interpersonal situations of intimacy, which may then become potent triggers for violence.

The role of the father, the ‘third object’ and the superego

Many of the above-mentioned psychoanalytic theorists have focused on role of the mother in the genesis of violence. What influence does the father have in this model? In normal development, the father or father substitute (who may be any third person significant for the child) may be thought of as having an essential role in creating a space to facilitate the child in gradually separating from the mother and assuming an identity of his (or her) own. The paternal relationship is internalised by the child to form an intrapsychic paternal or ‘third object’ that acts as an intermediary object by preventing pathological symbiosis and fusion between the self and primary/maternal object. Many violent individuals, however, have histories of absent or emotionally unavailable fathers, or abusive fathers who did not provide any source of love or care that the child could trust. In such individuals there is a lack of an adequate paternal identification and the person feels trapped in a dyadic relationship with the mother where there is no possibility of another/third perspective.

This failure of internalisation of a secure paternal function has been linked to impairments in the constitution of the superego or conscience. Freud (Reference Freud and Strachey1923) introduced the concept of the superego as an intrapsychic structure that, in a boy, results from the identification with the father to avert castration anxiety and, in a girl, results from identification with the mother to avoid loss of her love. The superego is today broadly understood as the internalisation of parental values, goals and restrictions to form an internal structure in the mind that represents the person's conscience, which can be experienced as supportive, punitive or absent. Deficits in superego functioning may explain the lack of empathy and remorse in psychopaths; by contrast, an overly harsh superego may lead to internal persecutory feelings of intolerable shame and guilt that lead to the eruption of self-preservative violence.

Attachment and mentalisation

Integrating some of these psychoanalytic ideas with those from attachment theory, writers such as de Zulueta (Reference De Zulueta1994) and Meloy (Reference Meloy1992) emphasise the deleterious effects of poor attachment experiences between the infant and its primary care givers. Early experiences of trauma, neglect and loss have an impact on the attachment process by interfering with the normal development of affect recognition and expression, empathy and impulse control. In these circumstances, the child resorts to violence as an angry protest; but, in the face of rejection, aggression is turned against the self or develops into more pathological destructive aggression. Violence can therefore be understood as being rooted in a failure in adequate caregiving or ‘faulty attachments’ (de Zulueta Reference De Zulueta1994).

Fonagy and colleagues extend these ideas by proposing that early trauma and disrupted attachments involving physical and emotional abuse may lead to aggression and violence by interfering with the development of mentalisation (Fonagy Reference Fonagy and Target1995). In normal psychological development the child becomes increasingly aware of his own mind and its contents through his growing awareness of his mother's mind by her capacity to demonstrate to him that she thinks of him as a separate person with intentions, beliefs, feelings and desires that are distinct from hers. However, if the mother is abusive or neglectful to the child, this prevents him from developing a capacity to feel safe about what others think of him. In such children, aggression therefore arises as a defence for the fragile emerging self against the assumed hostility of the object. If the abuse or neglect is ongoing, aggression and self-expression become fused in the mind of the child, impairing his capacity for reflection and mentalisation of his own and others' minds, and leading to adult relationships to self and others that are mediated against a background of aggression and violence.

Shame and humiliation

Where psychological development and the capacity for mentalisation have been impeded, the individual's sense of self remains precarious because it is based on more primitive modes of thinking and subjective experience. Psychodynamically, the mind of the violent person may be conceptualised as being formed by immature affects and defence mechanisms that may be normal in a young child, but are pathological if they predominate in adulthood. The person may experience affects primarily concerned with the self, such as anxiety, excitement, envy and shame, but may find it more difficult to have more mature feelings that involve appreciation of others, such as guilt, remorse, empathy and sadness. Similarly, more mature defence mechanisms, such as repression or sublimation, which would prevent aggressive impulses from erupting into violence, are lacking; instead the person is reliant on more primitive defences such as projection, splitting, projective identification and acting out. Emotions associated with vulnerability are particularly difficult for the person to process and hold within the mind, and instead are disowned and either projected into others in fantasy or acted out by actual violence. Shame and humiliation are particularly difficult emotions for all of us to tolerate, but for people with such a fragile sense of identity and agency, these affects are felt to have the power to violently disrupt the person's state of mind and therefore have to be expelled via violent action towards others.

In his work with inmates in high security prisons in the USA, Gilligan (Reference Gilligan1996) discovered that almost all of them justified their violent offences by believing that they had been ‘disrespected’ by the victim(s). This had evoked intolerable feelings of shame and humiliation that were rooted in much earlier experiences of being rejected, abused or made to feel that they did not exist. This had predisposed them as adults to being particularly sensitive to feeling ostracised, insulted, criticised or ignored. Gilligan proposes that shame and humiliation underlie all forms of violence, and that words alone may constitute trauma and trigger violence.

A psychodynamic framework for working with violence

How may some of these psychoanalytic ideas regarding the origins of violence inform the assessment, management and treatment of violent patients and offenders? A psychodynamic framework (Box 2) acts to organise and ground some of these psychoanalytic concepts in the context of working with violence in mental health and forensic settings. The framework involves consideration of several overlapping constructs. These include: the setting in which the person is managed, in which issues of containment, risk, boundaries and disclosure of information are paramount; assessment for risk and treatability; engaging the offender in a therapeutic process; specific therapeutic interventions; and recognition and analysis of the powerful countertransference reactions that violent individuals provoke in those involved in their care. Understanding how the offender's unconscious communications and utilisation of immature defence mechanisms affect the teams and institutions looking after them can be used to refine therapeutic interventions and the assessment and management of risk. This psychodynamic framework may be helpful in organising the various facets of managing and caring for violent offenders whatever the discipline of the professional and their prevailing model of understanding.

BOX 2 Psychodynamic framework for working with violent offenders

-

• A containing therapeutic environment/setting

-

• Careful assessment

-

• Engaging the patient

-

• Specific therapeutic interventions and modalities

-

• Monitoring countertransference

-

• Working with other professionals involved with the patient

Containment

Containment has a specific meaning within psychoanalytic theory, referring to the holding of emotions and feelings within the mind. ‘Containment’ is a term introduced by Bion (Reference Bion1959, Reference Bion1962) in describing the function of unconscious projective processes that occur between therapist and patient in the analytic situation as paralleling the way the baby projects its unbearable distress into the mother, who ‘contains’ it and responds by modifying the baby's anxieties. This is similar to Winnicott's (Reference Winnicott1954) notion of the ‘holding’ function of the analyst and of the analytic situation, providing an atmosphere in which the patient can feel safe and contained even when severe regression has occurred.

Although these authors were not describing forensic patients, their concepts of containment and holding are highly relevant to forensic settings. For violent offenders and patients, the provision of a safe and containing therapeutic environment is essential for risk management and treatment to be effective. Risk can only be managed safely if the anxieties of patients, individual staff and the institutions in which they work are adequately contained. But, as described above, many violent individuals lack the mature and robust internal mental structures that are needed to tolerate anxieties aroused by strong and conflicting emotions, particularly those associated with vulnerability, shame and humiliation. Such feelings have to be expelled from the mind through violent action or projected into other people's minds, including the professionals they are in contact with. Moreover, owing to the original failures in care that they suffered in childhood, these individuals have been unable to internalise parental values or societal standards and they mistrust authority figures, so are likely to break any boundaries or rules imposed on them. This may elicit unconscious retaliatory responses in clinical and managerial staff to impose even stricter and more punitive regimes.

The pathological culture of many forensic institutions and prisons mirrors the pathology of the patients and offenders housed in them. The primitive intrapsychic anxieties and defensive constellations of individuals become unconsciously reflected in the structure and function of the organisation. The offenders' early relationships, defined by aggression and violence, are recreated in their relationships with professionals, triggering internecine conflicts between offenders and staff members, and within the staff group itself, and causing splitting and fragmentation of the institution. Working in such toxic environments often leads to high levels of staff turnover, sick leave and burn out.

A containing environment is achieved not only by ensuring that robust physical and procedural security measures are in place, but also by attending to the unconscious communications between patients and staff and between different members of the multidisciplinary team or institution. Understanding the intense pressures and projective forces that they are exposed to, acknowledging the anxieties provoked within them, and recognising how the psychopathology of the patient may be re-enacted in the institution are vital in maintaining healthy interpersonal relationships and mutual care and respect. These often intense, unconscious countertransference responses can be elucidated and understood via multidisciplinary work discussion, staff support or reflective function groups so as to mitigate the destructive dynamics that paralyse therapeutic functioning.

The uses and misuses of countertransference in risk assessment

The role of clinical intuition in violence risk assessment has been recognised as a valuable addition to the application of traditional validated structured risk assessment tools in forensic practice (Carroll Reference Carroll2012). Intuition involves the use of emotions as a source of data; in psychodynamic terms this involves the countertransference. Countertransference refers to the emotional responses that the therapist or clinician has towards the patient. It reflects a dynamic in which the patient's unconscious communications interact via reciprocal processes of projection and introjection with the therapist's own conflicts and personal history to produce affective states and bodily responses that may feel alien to the clinician. Countertransference is by definition unconscious and therefore conscious feelings about a patient, such as boredom, may be misleading and disguise more unconscious unacceptable feelings, such as disgust or hatred.

Countertransference reactions to violent and antisocial patients are often disturbing (Box 3). These may range from therapeutic nihilism – the belief that the patient is untreatable – to excitement and fascination, often imbued with erotic feelings, which are rarely admitted to by the clinician (Yakeley Reference Yakeley and Meloy2012; Meloy Reference Meloy, Yakeley, Gabbard and Gunderson2013). Patients with severe psychopathic traits may invoke feelings of disgust (Hale Reference Hale and Dhar2008) or atavistic fear that, even in the absence of threatening behaviour, the therapist experiences viscerally as autonomic arousal (Meloy Reference Meloy and Meloy2002).

BOX 3 Common countertransference reactions to a violent patient (Meloy & Yakeley Reference Meloy, Yakeley, Gabbard and Gunderson2013)

-

• Therapeutic nihilism

-

• Illusory treatment alliance

-

• Fear of assault or harm

-

• Denial and self-deception

-

• Helplessness and guilt

-

• Devaluation and loss of professional identity

-

• Hatred and the wish to destroy

-

• Fascination, excitement or sexual attraction

Countertransference is a tool through which the patient's internal world may be accessed, and it is a cornerstone of the technique of psychoanalytic psychotherapy used to inform therapeutic interventions. However, if unacknowledged or unexplored, the clinician's emotional responses to the patient can contribute to subjective judgements that interfere with accurate evaluations of risk. Blumenthal et al (Reference Blumenthal, Huckle and Czornyj2010) investigated the relative contribution of actuarial and emotive information in determining how experienced forensic mental health professionals, who were well-trained in structured and actuarial risk tools such as the Historical Clinical Risk Management-20 (Douglas Reference Douglas, Hart and Webster2013) and Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (Hare Reference Hare2003) rated the risk of violence. They showed that these professionals were unaware how they often minimised the importance of well-known actuarial factors in risk assessment, and that their judgement was disproportionately influenced by emotive factors, for example ‘liking’ or feeling frightened of the patient.

The clinician's unrecognised subjectivity may result in errors, often in overestimating risk. Feelings of anger, fear or disgust in response to a patient's violence may elicit conscious or unconscious punitive or sadistic responses in the clinician, such as unnecessary restraint or prolonged incarceration. This in itself may increase the risk posed by the offender, in provoking anger and resentment so that he is likely to behave more dangerously. Some patients present themselves as victims of mistreatment and misunderstanding, eliciting sympathy in the clinician, who may then underestimate their risk. If the patient reoffends and inadequate risk assessment is exposed, this may lead to unhelpful defensive practices.

Psychodynamic interventions for the treatment of violence

Violence has always been considered one of the more serious contraindications for psychoanalytic treatment. It was thought that violent patients had weak ego strength and primitive defences and were therefore unlikely to be able to use psychoanalytic therapy, which is aimed at exploring the unconscious fantasies of the internal world, and that such treatment might increase the risk of the patient acting violently. However, a few early psychoanalysts, such as Karl Menninger (Reference Menninger1968) in the USA and Edward Glover in the UK (Glover Reference Glover1933), were interested in expanding the boundaries by treating violent patients. Glover worked at the Portman ClinicFootnote b in London, founded in 1931 to offer psychoanalytically informed treatments for violent, delinquent and ‘perverse’ patients, and employing many prominent psychoanalysts. These pioneering analysts laid the foundations for the discipline of forensic psychotherapy – the application of psychoanalytic expertise to the treatment of mentally disordered offenders.

The work of forensic psychotherapists over the past 25 years has challenged the widely held belief that psychoanalytic therapy is ineffective, if not harmful, for patients who act out in violent ways. Traditional psychoanalytic techniques have been adapted and refined for patients with a limited capacity for reflection, unstable affect regulation and impulsivity. Modifications of technique include actively fostering a positive therapeutic alliance, avoiding the use of free association or long periods of silence, limiting transference interpretations, and using supportive techniques to build ego strength such as identifying and distinguishing the different affects associated with violence (e.g. anger, excitement and anxiety). Although a psychodynamic understanding of violent patients assumes that unconscious determinants play a major role in their behaviour, interpretations of unconscious thoughts, fantasies, affects and motivations are used with caution, as these may be misunderstood as referring to concrete realities, which may disturb and destabilise the patient. The therapist is also alert to the patient's lack of trust and sensitivity to feeling criticised or slighted, which may be triggers for violence, and so will actively cultivate a containing and therapeutic stance in relation to the patient. Therapy aims to foster the development of a psychic function in the patient's mind that can begin to experience and tolerate loss, remorse, concern and empathy, and to learn to insert feeling and thought between impulse and action.

Group therapy is often more effective than individual therapy for many violent individuals. People whose aggression stems from intense core complex anxieties may find the perceived intimacy of individual therapy too threatening and may feel more contained in a group where the multiple relationships with other patients offer more than one target for their aggressive impulses and, paradoxically, attenuate them (Welldon Reference Welldon, Cordess and Cox1996). Engaging in a therapeutic group and seeing their own difficulties reflected in others can help to reduce antisocial behaviour and bring about therapeutic change. Group therapy also offers more opportunities to mentalise minds in relation to other minds. Moreover, the patient's dysfunctional patterns of relationships will inevitably be repeated in their relationships with other people in the group, including the therapist. This can be helpful in identifying the interpersonal triggers of violence and, if the consequent anxieties and conflicts can be tolerated and understood, patients may learn that disagreements and misunderstandings do not always have to be resolved by violent solutions. An important therapeutic focus in group therapy is how the group negotiates its rules and boundaries, and this is particularly important for individuals who have experienced inappropriate boundaries from their original caregivers. The experience of a therapist modelling appropriate boundaries that are consistent yet flexible can help antisocial offenders to become more trustworthy of others and prosocial.

Some of the therapeutic techniques and modifications for the treatment of violent behaviour detailed above have been operationalised into specific psychodynamic manualised therapies for people with personality disorders who exhibit violence towards self and others. Perhaps the most prominent is mentalisation-based treatment (MBT). Originally developed for the treatment of borderline personality disorder, MBT has been adapted for people with antisocial personality disorder and is increasingly being delivered in forensic settings (Adshead Reference Adshead, Moore and Humphrey2013; Bateman Reference Bateman and Fonagy2016: pp. 377–413).

Although most treatment programmes for reducing violent behaviour in the criminal justice system today are based on a cognitive–behavioural model, psychodynamic treatments, particularly aimed at offenders with personality disorder, are becoming increasingly available. Following the decommissioning of the Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder (DSPD) programme (Department of Health and Home Office 1999), the Offender Personality Disorder (OPD) programme was initiated in 2011 for managing high-risk personality disordered offenders; it is based on a ‘whole systems pathway’ across the criminal justice system and National Health Service (Joseph Reference Joseph and Benefield2012). This strategy is informed by a developmental model of personality disorder and recognition of the centrality of attachment experiences in the early and current lives of offenders. It offers a variety of different psychological interventions in prisons, probation and approved premises, including those based on psychodynamic principles such as therapeutic communities, psychologically informed planned environments (PIPES) and MBT. Research and evaluation of these initiatives is ongoing.

Future directions

This article offers psychiatrists and other mental health professionals one approach to understanding some of the putative factors involved in the genesis of certain types of violent behaviour. In viewing the heterogeneity of violence through a psychoanalytic lens I have focused on the existence of two modes of violence, self-preservative and sadomasochistic, which present distinctive behavioural manifestations and neurobiological underpinnings. I have not explored the aetiology and manifestations of other types of violence that occur in different circumstances, such as psychosis, groups, crowds and warfare, nor violence in relation to other important variables such as gender and sexuality. I have focused on how psychoanalysis offers theories that explore how pathological violence arises from disturbed early familial relationships, and how these dynamics may be unconsciously repeated in the individual's adult relationships, casting professionals and others in the roles of their early caregivers, which, if unrecognised, may result in unhelpful and inappropriate countertransferential responses. However, these psychodynamic explanations must be viewed as partial theories, which may complement and expand existing theories on violence from other disciplines and methodologies. Further efforts are needed to substantiate these concepts with empirical evidence, and integrate them with contemporary biological, ethological, attachment, sociological, cultural and psychological frameworks.

Similarly, the psychoanalytic or psychodynamic approach to the management of violent individuals and their impact on professionals, teams and institutions presented in this article is not meant to replace other therapeutic models and modalities, but may assist in the assessment, engagement and treatment of patients and offenders through elucidating the unconscious meanings and triggers of their violent behaviour. The application of psychodynamic thinking may be seen as constructing a psychotherapeutic container within which different types of psychological therapy may work synergistically in the best interests of patients and staff. Research into the efficacy, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the various psychological techniques and strategies, including those grounded in a psychodynamic approach, is needed to reduce antisocial behaviour and promote health and well-being in an oft neglected group of people who relate to others primarily through violence.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Sadomasochistic violence:

-

a is similar to instrumental violence

-

b involves negation of the object

-

c is associated with anxiety and palpitations

-

d is unrelated to self-preservative violence

-

e only occurs in domestic violence.

-

-

2 Melanie Klein:

-

a emphasised the reactive origins of aggression

-

b focused on Freud's self-preservative instincts

-

c emphasised the defence mechanisms of repression and sublimation in primitive aggression

-

d believed that excessive aggression resulted in an archaic superego

-

e proposed that containment was important in mitigating destructive aggressive impulses.

-

-

3 The core complex:

-

a only occurs in individuals predisposed to violence

-

b stems from a pathological relationship to a paternal object or ‘third object’

-

c involves annihilatory wishes

-

d underlies self-preservative but not sadomasochistic violence

-

e may be activated in interpersonal situations of intimacy.

-

-

4 Countertransference:

-

a involves the clinician's conscious experience of affects and bodily reactions that feel alien

-

b reveals the clinician's unconscious fantasies

-

c is solely based on the patient's unconscious projections

-

d is always an unreliable tool in risk assessment

-

e may aid understanding of institutional dynamics.

-

-

5 Violence:

-

a is best treated in individual psychotherapy

-

b may arise from disorders of attachment

-

c when triggered by shame and humiliation is more likely to result in sadomasochistic violence

-

d if treated by psychodynamic psychotherapy requires that the therapy be adapted to avoid long silences and highlight interpretations of the transference

-

e is best treated by MBT.

-

MCQ answers

1 a 2 d 3 e 4 e 5 b

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.