A. Introduction

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

Th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay

. . .

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin?Footnote 1

The judiciary is an institutional technology developed over thousands of years of human experimentation for one sole purpose: To solve disputes by enforcing the rules.Footnote 2, Footnote 3 A well-functioning judiciary is essential to the development of any nation. From a public perspective, the existence of an impartial dispute settlement mechanism allows political groups to reach ex ante compromise solutions—that is, laws—that, if violated, will be duly imposed ex post by this external mechanism—enforcement. From a private perspective, not only does the judiciary protect citizens’ rights against possible violations by the government itself—checks and balances—and others, but it also allows individuals to cooperate with one another to achieve their private goals through the generation of credible commitments called contracts. The institutional function of the judiciary, however, requires that any right violation be corrected in a timely manner. In this context, court congestion is a socioeconomic problem that reduces the effectiveness of the judiciary as a mechanism for fostering cooperation, development,Footnote 4 and in the long run, the coordination value of law itself.

Almost anywhere in the world, it is commonplace to say that the judiciary is in crisis.Footnote 5 In many countries, the judiciary is considered slow, inefficient, and expensive.Footnote 6 Numerous reforms have been implemented to try to expedite courts,Footnote 7 and many more are currently underway.Footnote 8 But the results have thus far not been quite satisfactory and it is fair to say that the caseload and court congestion may be rising in many jurisdictions. Numerous reasons have already been offered to explain court congestion: Lack of resources,Footnote 9 complex procedures,Footnote 10 lawyers’ incentives,Footnote 11 judges’ incentives,Footnote 12 poor management,Footnote 13 culture,Footnote 14 bad laws,Footnote 15 and an excessive number of laws,Footnote 16 among others. Efforts have been made to first try to identify the relevance of each of these possible explanations and then to solve them.Footnote 17 Nevertheless, until now, the idea that the very nature of law and the adjudicatory system may contribute to the congestion problem has not been fully explored. This very idea is what I plan to explore in this Article.

The knowledge of the economic nature of law and courts is an important step toward fully understanding the behavior of adjudicative systems around the world and may be a substantial step toward a positive economic theory of law. Until now, the literature has generally conceived law as a public good. In this Article I would like to diverge from this literature to show that law has a dual nature—coercion and compliance—and that law as coercion is actually a club good that requires a complementary good to be useful, courts. But because courts are private goods in nature, the bundled product will behave as a private good. However, the unrestricted implementation of access-to-justice policies with the objective of increasing the people’s access to courts will transform the bundled product into a common pool resource. The counterintuitive result of this transformation is that granting unrestricted access to the judicial system might actually prevent people from accessing their rights.

It is no coincidence that, in parallel with the increase in the demand for public adjudicative services, many countries have also been adopting reforms that have substantially decreased the costs of utilizing the judiciary to solve all types of disputes, including procedures simplification, creation of small-claims courts, and implementation of free public defenders’ schemes, among others. Nonetheless, access to public adjudicating services continues to be limited in practice and court congestion remains an endemic problem. Unexpectedly, the inquiry conducted in this Article predicts that this condition is the natural result of those policies due to the economic nature of law, courts and the resulting bundled product.

After this brief introduction, Section B.I initiates the discussion by exploring the economic nature of law using the traditional economic theory of goods and services to recognize the duality of law’s nature. Section B.II discusses that law and courts are complementary goods—a bundled product—while Section B.III shows the private nature of courts. Once the economic nature of law and courts is established, Section B.III.1 explains that access-to-justice policies will transform the economic nature of courts into a common-pool resource, and that such a transformation will result in its overuse—hence, utter court congestion—what I call the tragedy of the judiciary. Two policy implications are then explored: Section C explores the relationship between the tragedy of the judiciary and legal uncertainty, and Section D explores the potential adverse selection problem resulting from court congestion. Brief conclusions follow in Section E.

B. The Economic Nature of Law and Courts

I. The Economic Nature of Law

Because lawyers and economists frequently use the same words with different meanings, it is useful to have some conceptual uniformity. For a long time in the economic literature, the basic discussion about public versus private goods has been an endeavor about distinguishing between what should be the province of markets and what should be the province of governments. If something were called a private good, it should be provided by markets. If something else were called a public good, it should be provided by governments.Footnote 18 Yet, our comprehension of the attributes of goods or services has evolved toward encompassing more than merely the rivalry attribute identified by Samuelson Footnote 19 to also include a second attribute called “excludability.”Footnote 20

In this modern approach, access excludability refers to the possibility for the possessor of a certain good or provider of a certain service to exclude others, at low costs, from enjoying the good or service provided. On the one hand, a computer is an exclusive good because its possessor can prevent others from using it at low costs. On the other hand, national security is a non-exclusive good because it is not feasible to exclude other people from enjoying it once it has been provided. It is widely accepted that excludability is a requirement for the market provision of any good or service, because it allows for the provider to deny access to the prospective consumer unless both parties can reach mutually agreeable terms. It is the excludability feature that imposes upon one party the obligation to come up with something of interest for the other party so that the exchange may voluntarily occur; in other words, it is the excludability feature that makes the creation of a market possible.

Alternatively, rivalry occurs when consumption by one person either substantially prevents the same good from being consumed by another or otherwise significantly diminishes its utility. An apple and a glass of water are rival goods because their consumption by one individual prevents another from fully enjoying them. On the one hand, a good that is not eligible for consumption by someone else would be considered a rival good. On the other hand, if a good may be enjoyed by more than one person without substantially reducing the possibility of that good’s enjoyment by another, then it would be considered a non-rival good. National security and weather forecasts are examples of non-rival goods, because the consumption of these services by one individual does not preclude others from enjoying the same benefits, but rather they remain available for use by others in substantially undiminished quantity and quality.

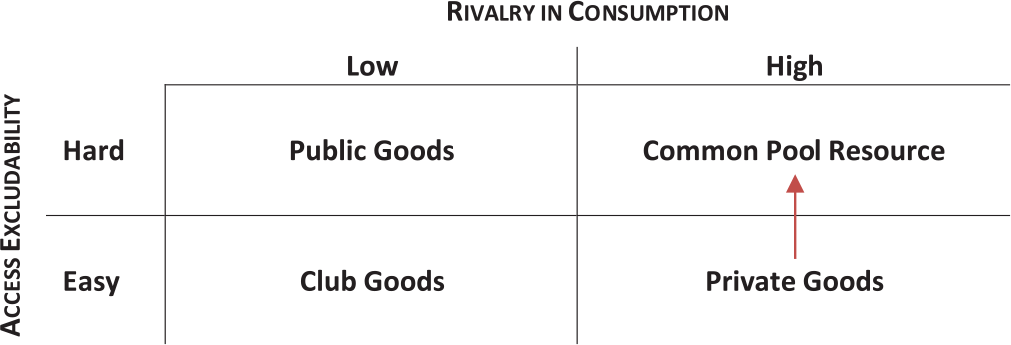

Although we normally talk about these two characteristics in binary terms to make the discussion easier, in fact, they vary significantly in degree from one extreme to the other in accordance with the good or service and the actual context. In any case, excludability and rivalry are two independent characteristics that can be combined to create four different types of goods: (1) Public goods are, simultaneously, non-rival and inclusive (non-exclusive);Footnote 21 (ii) private goods are opposed to public goods as they are rival and exclusive; (3) common pool resources (CPRs) share the non-exclusivity of public goods, but their consumption substantially diminishes utility for other users, rendering them rivals in use, as are private goods; and (4) club or toll goods are exclusive as are private goods, but are non-rivals as are public goods.Footnote 22 For clarity purposes, we can summarize this classification as demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Economic Types of Goods.

Now the traditional discussion regarding the provision of goods by governments or markets becomes even more nuanced. It is relatively clear that private goods can be efficiently provided by markets. “Efficiently,” in this context, means only that—in a perfectly competitive market—this kind of good would be provided for all those who would be willing to pay the costs for the provision of the good. It is also clear that market mechanisms can be used to provide club goods, as the provider may easily demand a price for access to the service or good.Footnote 23 The good may still be enjoyed collectively, although only by those who actually paid the toll, unless the provider decided to offer the good for free and bear the costs of provision alone.

Having equalized terms and concepts, we can move on to explain how the application of the economic theory of private and public goods may illuminate our search for the economic nature of law and courts and assist our understanding of legal phenomena.

The question regarding what the law is, or rather, the definition of law, is a recurring issue in legal philosophy that has spurred all kinds of answers.Footnote 24 It is not the purpose of this Article to tackle the issue from a philosophical perspective. Instead, this Article aims to use the public and private good theory to try and better understand both the economic nature of what we normally call “law” and the economic nature of accompanying adjudicative systems, in order to advance toward a positive economic theory of law.

The majority of the discussion on the economic nature of law is primarily, in effect, just an argument within the broader debate about whether an anarchist society is viable,Footnote 25 or instead whether a government should be created and called upon to impose order. For those who argue in favor of the public provision of law—meaning its creation and enforcement by government—law is considered a public good. For example, Buchanan used the public and private good theory with Samuelson’s traditional approach to affirm that, since law is a kind of heterodox public good—an externality—it would not be provided by markets.Footnote 26

Expressly mentioning Buchanan’s work, Landes and PosnerFootnote 27 also argued that law is a public good, but their argument to support this claim entailed that precedents—not necessarily law—could be used by one person without substantially diminishing its utility as a precedent to another person. We should observe here that the argument is based solely upon the precedent non-rivalry attribute. In a later work, Landes and PosnerFootnote 28 also argued that a precedent is a public good, although this time the argument entailed that precedents created in a private litigation may also be useful in the future for those not taking part in the original dispute that created the precedent. One can observe that the argument now claims that precedent creates a positive externality.Footnote 29 Interestingly enough, Landes and Posner argued that if the precedent was useful only for the original litigating parties, then the precedent would actually be considered a private good.Footnote 30 The same kind of argument is presented by authors worldwide, such as Carvalho, who stated that something is a public good if it generates a positive externality, or more directly that the law is a public good.Footnote 31 Regardless of the reasoning, the idea of law as a public good seems to be quite commonly accepted.

Along with this tradition, although slightly diverging, I would like to argue that law can, in fact, act both as a public and a club good. In its simplest conception, law is nothing but information regarding how adjudicative systems are likely to behave when presented with a dispute—coercion—as well as information regarding how people are likely to behave in general—compliance. As I will demonstrate shortly, just as light may behave either as a particle or a wave—known as the wave-particle dualityFootnote 32—law behaves as a club good when we are discussing coercion, and it behaves as a public good when we are dealing with spontaneous compliance—the law duality.

In the first, more traditional perspective of law as coercion,Footnote 33 I acknowledge that when someone goes to a lawyer and inquires about the law, he is actually asking one of several questions: How courts will behave if a given dispute arises, how the government expects him or his business to behave, or otherwise, how the government may employ its powerful apparatus to make him behave—hence, enforcing the law. This is why it is possible to say that the first nature of law is to inform in which direction enforcement will go, and the utility that law provides is the knowledge of this direction—and how to channel or avoid it.Footnote 34

From this perspective, it is easier to perceive that, when authors declare that law is a public good, they are normally dictating it is a public good in the same way that any information is a public good.Footnote 35 The fact that I know how courts will behave and then use this information to conduct my daily business affairs does not preclude your knowing of the same information, nor does it affect your conducting of your business accordingly. This analysis fails, however, to grasp that what is being discussed here is not actually the economic nature of law itself. Rather, what is being discussed is that law is non-rival.Footnote 36 When we say that the consumption of law by one person does not preclude its consumption by another, we are only saying that this knowledge can be consumed by both you and me. We are not saying anything about its excludability, and I would like to argue that law as coercion is, in reality, highly excludable.

Legal theorists are constantly involved with the question of jurisdiction, referring to either a government’s general power to exercise authority over all persons and things within its territory or a court’s power to decide a case or issue a decree.Footnote 37 The key word here is power—the simple fact that the enforcement of legal rules requires jurisdiction means that, at times, a government or a court is legally powerless to enforce its rules. In this case, even though the parties may know which law would theoretically be applied de jure, the lack of jurisdiction means that the considered law will not be enforced; hence, the law is inapplicable de facto. Consider an international arbitration award that is to be enforced in another country that does not recognize part of the applied substantial law used to solve the dispute. As a matter of fact, although you know what the applicable law is, its enforcement is effectively denied. This hypothetical situation is just one example of how law can be excluded from the consumption of an individual. I will, however, offer two alternatively interesting historical examples to make the point even clearer.

Originally, when Rome was just a city-state, Romans named the law that applied to themselves ius civilis (civil law), and this law applied exclusively to the citizens of Rome. Thus, although most people dwelling within Roman territory knew about ius civilis, those who were not Romans were effectively excluded from its application and protection; hence, they were excluded from the consumption of ius civilis.Footnote 38 With the growth of the Roman empire, Romans gradually introduced legal rules also applicable to those who were not Roman citizens, which became known as ius gentium: The body of legal institutions and principles common to all Roman subjects regardless of their origins.Footnote 39 In this sense, although both ius civilis and ius gentium are non-rival in nature and would be considered public goods by the authors discussed before,Footnote 40 the former was actually excluded from consumption by non-Romans, while the latter was consumed freely.

Another clear example of the excludability of law is the history of commercial law in Brazil. Prior to the enactment of the 2002 Civil Code,Footnote 41 Brazilian citizens were divided into two different groups: The regular citizens, whose business and actions were considered civil in nature and were duly regulated by the 1916 Civil Code,Footnote 42 and the merchants, who normally explored commerce and industry and, as a result, were regulated by a different set of rules as established by the 1850 Commercial Code.Footnote 43 Note that the action would often be strictly the same in all relevant aspects, such as the sale of a good, but if the seller was a merchant, the Commercial Code would be applied to the transaction. Alternatively, if the seller was not a merchant, the Civil Code would be applied. As in the ius civilis/ius gentium dichotomy, here, the traditional authorsFootnote 44 would say the law embedded in the Civil and Commercial Codes was a public good because its application to one subject would not prevent its application to another subject; but again, this reflects only its rivalry dimension. In fact, the Commercial Code brought many special provisions—such as, asking for bankruptcy,Footnote 45 issuing a public power of attorney without a notary,Footnote 46 and executing specific contractsFootnote 47—that regular citizens could not enjoy. As a result, non-merchants were barred from consuming the law embedded in the Commercial Code—illustrating excludability—although, in principle, the consumption by one agent would not preclude another from enjoying it—illustrating non-rivalry.

In this sense, although we all agree that law is non-rival in nature—as is information in general—it is quite clear that law as coercion is highly excludable; ergo, law is not a public good in nature, but rather it is a club good.Footnote 48 One may ask: What are the implications of recognizing that law is a club good if it is non-rival anyway? The simplest answer to this question is that, since law as coercion is excludable, the provider or supplier of the adjudicative service may withhold services from those that refuse to pay the costs of providing such services. As a result of the excludability of law as coercion, there can be a market for law even in the absence of government.Footnote 49 In a more technical way, law as coercion is not vulnerable to the free-rider problem because it is excludable. Yet, the issue here is not that the market for law would be vulnerable to the free-rider problem and law would therefore not be provided by a market, as BuchananFootnote 50 argued, but that law is strongly characterized by a positive externality—undersupply by the market.

When I say that law is knowledge of how courts or government agencies will behave—enforcement—we can separate two aspects of this assumption: One being for the consumer of this information, and the other being for the employer of this information—the adjudicator.Footnote 51 On the one hand, the subjects under the law know how to behave and how to predict the behavior of others simply by possessing the knowledge of what the law is—the applicable rules. This knowledge will allow these subjects to make choices and coordinate their behavior. On the other hand, the adjudicators will know how to solve a dispute simply by being aware of what the law is—the applicable rules—and then applying those rules to the facts before them—known as syllogism. In both cases, law is information regarding what rule is most likely to be enforced in a given case.Footnote 52 This system creates a feedback loop in which the more a rule is applied to the same set of cases, the more the rule’s value is reinforced and spontaneous or enforced behavior will fit into the expected rule of conduct, constituting a positive feedback. This is the demand-side economies of scale of the rule of law, or its network effect.Footnote 53 The greater number of people who know about what the law is and the more they can sustain a rational expectation that these are the rules that will be enforced in the emergence of a dispute, the more people are likely to spontaneously follow it—hence, the more valuable this knowledge is.Footnote 54

The network effect associated with law reinforces the importance of statutes created by parliaments—which are nothing more than publicly provided, specialized legislative systems—and may put into check the highly debated efficiency hypothesis of the common law system.Footnote 55 In any case, the assertion that the production of law creates a positive externality or that law as enforcement is highly characterized by network effects does not alter its economic nature, meaning that it is non-rival and highly excludable—ergo, a club good.

The focus on law as knowledge of how the adjudicative system will behave when presented with a dispute explains its value in social contexts where enforcement plays a major role. This explanation, however, does not elaborate upon why we witness so much compliance with legal rules even in contexts in which enforcement is less likely. To understand this phenomenon, one must recognize that law also serves as a focal point for how people are likely to behave and, in doing so, induces collective behavior toward certain paths that will generate self-sustaining equilibria, creating compliance without enforcement.

In this second, less traditional perspective of law, I refer to the fact that people at times comply with legal rules even in the absence of a credible threat of coercion—in the absence of enforcement. Social scientists have struggled to explain why this is the case, and some argue that, when agents perceive legal order to be legitimate, they will follow the rules naturally or their behavior will be restricted by social beliefs.Footnote 56 More recent authors have tried to explain the same phenomenon by employing game theory to show that social behavior can emerge naturally from human interaction, and the existence of law itself provides focal pointsFootnote 57 that will attract collective behavior and generate behavioral equilibria.Footnote 58 In accordance with this more modern approach, it is reasonable to say the second nature of law involves informing how people normally behave, and because most people will likely behave in such a way, there is ultimately no gain in behaving differently; hence, compliance becomes a self-sustaining equilibrium. In this case, the utility that law provides is not the enforcement of a certain rule, but the knowledge of this social direction, and how to behave accordingly.Footnote 59

It is important to stress that a Nash equilibrium is defined as a stable state of a system involving the interaction of different agents in which no participant can gain by a unilateral change of strategy, if the strategies of the others remain unaltered. In other words, a social state is considered a Nash equilibrium when no individual gains from changing his own behavior unless someone else also changes her behavior, and because there is no individual gain in changing behavior, that social state—equilibrium—is stable.

One may observe how the network effect of law is even more relevant when dealing with law as compliance. As the greater number of people behave in a certain way, the higher the probability becomes that others will adjust their behavior accordingly; hence, the prominent behavior role as a focal point is stronger and that particular equilibrium is more likely to result. I may even claim that law as compliance becomes an equilibrium only when the network effect is so powerful that it transforms general non-compliance behavior into irrational behavior, meaning the payoff for non-compliance is generally lower and the behavior becomes self-sustainable.

In any case, if law as coercion is clearly a club good—non-rival and excludable—the same cannot be said about law as compliance. Law as compliance is also non-rival because your knowledge of how most people behave within a given society does not preclude me from knowing the same and enjoying the benefits resulting from this knowledge. Yet, since law as compliance does not require enforcement, it is pure information and, once available, it cannot be withdrawn from the public; hence, law as compliance is non-excludable. As a result, I reason that law as compliance is a public good in nature because it is non-rival and non-excludable.

Considering that here I am really interested in the relationship between law and courts—the bundled product—and, debatably, law as compliance may not require enforcement—meaning, law as compliance may not require an adjudicative system to work—I shall focus on law as coercion henceforth. By analyzing the economic nature of adjudicative systems and their relationship with law as enforcement, it is my objective to explain interesting aspects of judicial systems at large.

II. The Complementarity of Law and Courts

In the previous section, I demonstrated that law as coercion is non-rival though excludable from consumption at low costs—excludability—and hence, it is a club good. Now, I would like to explain how this insight reveals something very important about the relationship between law and adjudicative systems: Law and courts are complementary goods.

When we understand law as coercion, it becomes clear that we are referring to law as the set of rulesFootnote 60 that are applied by an adjudicative system to solve disputes within a given jurisdictionFootnote 61 and consequently shape collective behavior. In this sense, the informational utility of law resides precisely on the indication of how the adjudicative system will behave or how force will be employed if a given dispute is brought before it.Footnote 62 This informational role may, in fact, be enjoyed only if there is an actual enforcement mechanism and if this mechanism is able to enforce its decision. In other words, law is useful only if there is an effective adjudicative system to support it, just as an intravenous medicine is useful only when accompanied by a syringe. From an economic perspective, these statements are equivalent to saying that law and adjudicative systems are complements. In fact, I would like to argue here that law and adjudicative systems are perfect complements, meaning they must be consumed together in order to be considered useful. They are a bundled product.

On the one hand, an adjudicative system that follows no rule—court without law—would be no different from an ergodic stochastic system. Regardless of the case brought before it, there would exist a random chance that the claimant would succeed and, at any dispute, the chance of prevailing would be independent of the initial state of the system. In this scenario, there would be no need for a judge or any alternative decision mechanism other than a computer with a random seedFootnote 63 to settle the dispute. The dispute resolution service would be provided almost instantaneously, but the result would be a complete social waste, as agents would be unable to coordinate behavior ex ante—one cannot know what decision will be taken—and the result would be useless for coordinating behavior ex post—how this case was decided is irrelevant for similar future cases. In other words, the whole point of having a legal system is to coordinate behavior by establishing a rational expectation of others’ behavior, including the government’s.Footnote 64 If the dispute resolution mechanism is ergodic and stochastic, this basic function of law is denied, and one may claim not only that there is no law at all, but also that courts are useless. That is why I stated at the beginning of this Article that the judiciary is an institutional technology developed through thousands of years of human experimentation with one purpose only: To solve disputes by enforcing the rules. If rules are not enforced, the sole purpose of law and courts is denied.

On the other hand, a legal system without an enforcement mechanism—law without court—would be ineffective for coordinating behavior when people disagree about the law. First, if two interacting agents ex ante agree that their course of action is the best option for their own interest, there is no need for law to establish what conduct should be followed.Footnote 65 There is no dispute. The agreed-upon behavior is a dominant strategy, and therefore cooperation will result. This is also true if the agents are already in a Nash equilibrium, even though, ex post, they may not agree that this situation is the best option for one of them. Since no agent can improve his or her results by unilaterally changing his or her own behavior, the equilibrium is self-sustainable, and no additional enforcement is required.

Law is useful when there exists more than one interesting conduct possible either preceding or following the interaction. If the law precludes one of the parties from engaging in ex post divergent behavior, the other party may trust ex ante that the agreement will follow through, and cooperation is rendered viable. In order to do so, however, law must be able to coercively preclude such divergent behavior; hence, enforcement is required. One may clearly argue that the more frequently those rules of conduct are internalized, the less enforcement will be required, but unless one can construct a society of perfect human beings, some level of enforcement—however light—is still required.

Second, from a social perspective, law is also relevant when, although the engaged parties fully agree with the conduct in question, their cooperation produces negative effects over third parties—known as externalities. In this scenario, assuming that the transaction costs are considerable,Footnote 66 it is in the public’s interest that law is able to prevent, to limit, or to require adequate compensation for such behavior; because the agents involved may be unwilling to comply, again, enforcement will be required.

Third, people at times may disagree among themselves regarding what was actually agreed upon, what the legal rule is, or whether there exists a legal rule at all. In these cases, a dispute mechanism is required to resolve ambiguities and fulfill legal gaps, which is normally the other ancillary function of the adjudicative system.Footnote 67 Still, even though we normally consider ambiguity reduction and gap-filling functions as attributed to the courts in most, if not all, legal systems around the world, these roles are not really a required function of the adjudicative systems.

For example, in 1603, the Portuguese Philippines Ordinations allowed for courts to resolve law ambiguities and fill the gaps using many techniques, including subsidiarily applying the Roman Corpus Iuris Civilis, or the canonic law.Footnote 68 Due to excessive freedom in interpretation, however, the Law of Good Reason of 1769 withdrew most of such functions from courts and allocated them back to the Portuguese Crown.Footnote 69 Another similar example is the Brazilian Imperial Constitution of 1824, which separated the role of fact-finding for juries and the role of law adjudication for courts and restricted the rule-making and legal interpretation roles for the General Assembly.Footnote 70 In any case, even if the gap-filling role is attributed to courts, enforcement will be required to make such judge-created rules effective, and even if the ambiguity-solving task is attributed to courts, enforcement will be required to make the chosen interpretation effective. In this sense, choice hermeneuticsFootnote 71 also requires enforcement.

As a result, whatever technique courts adopt to solve a dispute—mere adjudication, ambiguity reduction, or gap-filling—the fact is that the result most likely will become law, and enforcement will be necessary if spontaneous compliance does not come through. In any case, law will be useful only if a workable adjudicative mechanism is available; hence, law and courts are complementary goods—a bundled product.

III. The Economic Nature of Courts

Once it has been established that law as coercion is a club good and its excludability is deeply related to its complementarity with courts, the inquiry into the economic nature of the adjudicative system should help us understand some aspects of the legal system’s dynamic. This will lead to the surprising conclusion that unrestricted access-to-justice policies may, instead of granting rights, actually result in their de facto denial.

Similar to law, any adjudicative system is excludable by nature. Consider an arbitration court and the requirement that, prior to the commencement of the arbitration, the complainant or both parties pay part of the filing fee or the arbitrator’s fees. Without payment, the arbitration remains uninitiated: Until consumers pay for the service, the adjudicative service provider will not provide the service. The same can be said about public courts. In many jurisdictions, for every filed case, there must be the payment of an initial filing fee, otherwise the case will not move forward. The filing fee may fully cover the costs of providing the service or it may be subsidized, but in both cases, without payment, the adjudicative service will not be provided. The idea here is not to discuss whether or not the filing fee actually exists or whether the service is subsidized or not, but to make clear that such a fee could easily be implemented to regulate access to the service; ergo, adjudicative services are excludable at very low costs.

To make the point even clearer, the excludability of the adjudicative service need not occur in the form of a filing fee nor expressly as a price. Access to the services can be rationed using other mechanisms, such as quotas or cost-benefit analyses. For example, since the Constitutional Amendment No. 45 of 2004 was implemented, the Brazilian Federal Supreme Court will hear constitutional cases through extraordinary appeal only if the Court deems the issue at hand to be of general repercussion.Footnote 72 Even if a case truly involves a potential constitutional violation but the issue is restricted to the parties, the Brazilian Supreme Court may refuse to hear it. One can observe here that the general repercussion legal standard is actually an inquiry into the positive externality nature of the issue at hand. If the issue brought before the Supreme Court generates a positive externality, meaning it is useful for other actual or potential parties, then the scarce resources of the Supreme Court can be allocated toward solving it. If not, then the case is dismissed and, for all purposes, the litigants are denied the adjudicative services of the Supreme Court. Here, the adjudicative service is rationed without the use of a price mechanism and rather employs an implicit cost-benefit analysis called “general repercussion.”

The same kind of service-denial discretionary power was granted to the Supreme Court of the United States by the Judiciary Act of 1925 and the Supreme Court Case Selections Act of 1988. According to these statutes, most potential consumers of law are prevented from receiving adjudicative services from the Supreme Court as a matter of right.Footnote 73 Just as in the general repercussion case in Brazil, a party who desires that the American Supreme Court review a decision of a federal or state court must first file a petition for writ of certiorari, and the Supreme Court possesses the discretionary power to decide whether or not to grant certiorari. In fact, most cases are denied certiorari. Once again, access to the judicial service is rationed at low costs without the use of a price mechanism, and hence, courts are excludable.

The next question is whether or not adjudicative services are rival. When discussing the law, we have observed that, because law is information, it is non-rival. The knowledge of the law by one person does not preclude another from enjoying the same benefits and conducting her business accordingly. The same can be said about judges when applying the law. The fact that a judge applied a statute or a precedent in a case does not preclude another judge from applying the same legal rule. In fact, in both cases, the application of law by one agent only reinforces the utility of the law for others, its network effect. The case for the adjudicative systems is different, as they are normally rival in nature, although the discussion is somewhat subtler.

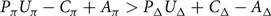

If we understand that the judiciary possesses high rivalry, then we must conclude that it is a private good—rivalry + excludability. If we understand that it is non-rival, then, similar to law, it is a club good—non-rivalry + excludability. I believe the judiciary can be both, depending upon the context. Consider a single judge called to solve a single dispute. Depending upon the complexity of the case, the judge could simultaneously hear another case without substantially slowing down the analysis of the first. Remember that a case is a series of actions, not all of them simultaneous or exclusively executed by the judge; hence, there are many opportunities for the judge to perform other parallel acts while he or she waits for the other parties to perform their actions. In this scenario, at least initially, adjudicative services are non-rival—therefore, the judiciary would be a club good, just as law is a club good. In contrast, if simultaneously analyzing two or more cases would lead to excessive complexity or if the number of cases is greater than available supply, then adjudicative services are rival in use and the judiciary would start behaving similarly to a private good. In this sense, it is reasonable to say that, at first, the judiciary is a club good if the installed capacity is superior to the perceived demand. As quantity demanded increases, it begins acting more like a private good, becoming rival and prone to congestion if its use is not rationed somehow. In other words, the judiciary is a highly congestible good (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Judiciary as a Private Good.

At this point, it should be clear that, even at an earlier stage when the supply is greater than the perceived demand, the judiciary is a club good—easy excludability—never a public good—hard excludability. Nevertheless, when it begins to befall rivalry due to a mismatch between supply and demand, the judiciary will gradually begin behaving as a private good because each additional case filed will be added to the case log and will slow down the adjudicative service that is to be provided in other cases; henceforth, each additional case filed will decrease the utility of employing the judiciary for everyone. In this sense, although consumption is not entirely rivalrous initially,Footnote 74 each additional filed case imposes a negative externality on the other users of the judicial system. If no other rationing mechanism is installed, that negative externality will materialize in the form of queues, which, combined with the shorter time available to judges to consider each case, will result in increasing degradation of the quantity and quality of the services provided. For our present purposes, this utility-reduction effect means that the judiciary will begin behaving as a rival service.Footnote 75 The fact that the judiciary is congested in so many places worldwide only corroborates the idea that courts are a rival resource.

1. The Tragedy of the Judiciary

Now that I have shown that courts behave like private goods while law as coercion is a club good, it is relatively easy to understand that the unrestricted access to adjudicative services will lead to the natural formation of queues to ration the supply. Any additional use of the adjudicative service would prevent or substantially diminish the utility of the service for other users, just as the inclusion of an additional car diminishes the utility of congested roads for other drivers.

Since courts are private goods, the simplest solution for the court congestion problem would be to exclude users from the services through means such as general repercussion or certiorari civil procedure tools—non-price rationing mechanisms. Another solution may be to let the free market work and the price mechanism regulate demand in the same way that it regulates demand for arbitration courts. The competition among users would raise the prices of the adjudicative services, and the resulting price increase would ration the scarce resources, naturally excluding users that attribute less value to the service. Thus, an equilibrium between supply and demand would be reached. As a result, there would be a smaller number of actions filed and those claims whose litigants assigned the lowest value, according to their willingness to pay, would not be judged or would be served with a much longer waiting time.Footnote 76

Of course, since the market only captures the preferences of those who are capable and willing to express their preferences through payment—referred to as revealed preferences—the price mechanism would solve the congestion problem at the expense of the most vulnerable element of society—the poor—who would be excluded from enjoying the service even though they might actually value the service more than its costs. In addition, because law and courts are complementary goods, the exclusion of some users from access to the adjudicative services necessarily implies they will also be excluded from enjoying the benefits of law itself. In other words, by excluding some citizens from accessing the courts, we would also be excluding them from accessing their rights. This is unacceptable. In this sense, from an economic perspective, adjudicative services may be considered merit goods, meaning they are so important for human development that every individual should have access to them on the basis of some concept of need rather than ability or willingness to pay.

The idea that the judiciary is a merit good has taken over the world, as most countries have decided that adjudicative services are a fundamental right and, therefore, governments should grant free access to all in equal terms. According to the United Nations:

Access to justice is a basic principle of the rule of law. In the absence of access to justice, people are unable to have their voice heard, exercise their rights, challenge discrimination or hold decision-makers accountable. The Declaration of the High-level Meeting on the Rule of Law emphasizes the right of equal access to justice for all, including members of vulnerable groups, and reaffirmed the commitment of Member States to taking all necessary steps to provide fair, transparent, effective, non-discriminatory and accountable services that promote access to justice for all . . . . United Nations activities in support of Member States’ efforts to ensure access to justice are a core component of the work in the area of rule of law. Footnote 77

In reality, this idea has been around for quite a while. The twentieth century witnessed an increasing preoccupation with access to justice. The first wave was concerned with legal aid for the poor and started in the West in the 1920s in Germany and England.Footnote 78 The second wave was concerned with the representation of diffuse interests and efforts to address the problem of representing groups and collectives other than the poor, which started in the late 1960s in the U.S. Footnote 79 The third wave went beyond advocacy by focusing not only on legal aid and the defense of diffuse interests, but also on all kinds of institutional barriers to a more effective access to justice.Footnote 80 These waves of reform, aimed toward increasing access to justice, keep coming from time to time.Footnote 81

In the 1970s, Mauro Cappelletti directed a research project funded by the Ford Foundation and the Italian National Council of Research (CNR), called the “Florence Access-to-Justice Project.”Footnote 82 Cappelletti and Garth stated:

The right of effective access is increasingly recognized as being of paramount importance among the new individual and social rights since the possession of rights is meaningless without mechanisms for their effective vindication. Effective access to justice can thus be seen as the most basic requirement – the most basic “human right” – of a modern, egalitarian legal system which purports to guarantee, and not merely proclaim, the legal rights of all.Footnote 83

In other words, as I propose here using economic theory, Cappelletti and Garth recognized that law and adjudicative services are perfect complementary goods. One is useful only in the presence of the other. In other words, law as coercion and courts are a bundled product. The problem is that the behavior of the bundled product will be determined by the limitations of the combined good.

No reasonable person would deny that access to justice is a fundamental requirement for both human development and the implementation of the rule of law. Nevertheless, what this kind of initiative fails to understand is that, if public policy subsidizes access to the adjudicative services or creates a legal right to unrestricted, free access to the judiciary—which is a private good in nature—in practice, this public policy changes the economic nature of courts by making it legally hard to exclude users. Yet, because the judiciary’s rivalry attribute is inevitable, if the judiciary is turned into a free access system, then the result is the transformation of the judiciary into a common pool resource (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. The Judiciary as a Common Pool Resource.

As a result of unrestricted free access policies, the judiciary becomes a common pool resource system vulnerable to overexploitation and prone to court congestion.Footnote 84 The more governments around the world implement policies to incentivize people to use the judiciary, the more courts will become congested,Footnote 85 just as would occur with any other overexploited common resource. The resulting court congestion substantially increases both the amount of time required to solve a dispute and the probability of low quality or simply incorrect results, as judges become overwhelmed by growing caseloads while simultaneously receiving demands for increasingly expeditious answers. Within the chaotic world of overexploitation of the judicial system, it is not unreasonable to expect that judges would focus as much effort as possible on dispute resolution to reduce the case log and invest as little effort as possible on legal certainty,Footnote 86 the latter of which is a positive externality that only marginally reduces the case log for any specific court.

In sum, once unrestricted access-to-justice policies are in place, it becomes relatively straightforward that the judiciary will become non-excludable and more users will access the system. However, since adjudicative systems are rival in nature, the expected result will be the overexploitation of the system leading to the substantial degradation of the services provided.Footnote 87 We all want everyone to have access to adjudicative services, because being able to vindicate one’s rights is an essential feature of being able to exercise them. Nevertheless, once unrestricted access to courts is granted, the system itself will be overloaded with cases, and although access to the system will be granted, the adjudicative service itself will not be provided in a timely manner, or it will be provided, but at a much lower quality; this result is exactly what I call the tragedy of the judiciary.Footnote 88

The more people use the judiciary, the more congested it becomes and the less useful it will be for the next user, as its ability to provide public adjudicating services will be hindered. The problem is focusing on access to the system—the judiciary—when focus should be placed on the possibility of using and enjoying its fruits—rights—which are, to a large extent, what people actually want. By focusing only on rights awareness and encouraging the unrestricted use of the judiciary without recognizing that it is already overloaded with cases, public policy is accelerating and encouraging the overexploitation of the judicial system, which is already dysfunctional in many jurisdictions. By recognizing the common pool resource nature of the judiciary, we can better understand what is happening within courts all across the world in which free access policies are increasing pari passu with court congestion.

It may be no coincidence that some authors have identified an unprecedented growth in caseload, resulting in court congestion during the 1960s—the same period in which the biggest wave of access-to-justice policies occurred. Posner showed that, although court caseload has been steadily increasing in the Federal Courts of the United States, this growth was modest and easily accommodated by the three-tiered system created in 1891 until the 1960s, when the caseload exploded.Footnote 89 The Task Force on Administration of Justice reached the same conclusions,Footnote 90 and Landes reinforced the argument, stating, “[i]t is widely recognized that the courts are burdened with a larger volume of cases than they can efficiently handle.”Footnote 91

One may notice the irony and clear contradiction of Cappelletti’s and others’Footnote 92 defense of free access to justice while simultaneously defending that court congestion is actually inaccessible justice.Footnote 93 Similar to modern defenders of unrestricted access to justice, Cappelletti simply could not perceive that these two goals are plainly contradictory. The objectives of greater access and greater speed are, to a large extent, incompatible. If the number of cases widely exceeds the judiciary’s capacity for analysis and prosecution, each case will take more and more time to be solved, and the analysis of each case will be increasingly more superficial because judges will not have enough time to carefully go through each one. This condition diminishes the quality of decisions and, at the limit, undermines the reason for having a judiciary.

On top of this, another issue that seems to escape the perception of some social scientists is that, while the production of law by courts creates a positive externalityFootnote 94 and a positive network effect, the judiciary is a rival resource and its overexploitation creates congestion, which is a negative externality. In other words, we can consider the precedents or the jurisprudence constante or the ständige Rechtsprechung produced by courts, as a byproduct of their dispute resolution activities, a positive externality, because others may be able to enjoy the benefits of the created precedent or case law without having contributed toward the cost of producing it.Footnote 95 Nonetheless, the filing of a case itself will slow down the provision of adjudicative services as a whole for everyone else, resulting in an offsetting negative externality. Since most cases do not produce a precedent or jurisprudence constante or ständige Rechtsprechung, while all filed cases contribute to court congestion, I believe the negative externality of court congestion by far offsets any value resulting from the positive externality of precedent or case law production. This conclusion renders moot any economic argument for the provision of subsidies for litigation for the purpose of increasing precedent or case law production.

The tragedy of the judiciary leads us to a puzzling conundrum: People should be able to vindicate their rights without substantial barriers, but unrestricted access to the adjudicative system for each person undermines access to justice for everyone else. It should be possible to create some governance mechanisms that prevent the overexploitation of the judiciary,Footnote 96 although the recognition of the economic nature of courts leads to the conclusion that some kind of rationing may be necessary. This requires some strategic thinking about how to better structure courts and the judicial system, which may ultimately lead to some policy implications.

For illustrative purposes, I can think of a few examples of policies focused on mitigating the tragedy of the judiciary, such as higher sham litigation penalties when parties abuse the adjudicative system (bad faith litigation) and increased incentives for and possibilities of collective actions to improve the provision of the services with reduction of traffic. Just as public transportation is a more efficient solution for traffic jams than is the building of more roads, collective actions are more useful in reducing court congestion than is the building of more courts. By the same token, the number of collective actions available against government bodies, including class actions about tax and social security purposes, should be expanded, as a great number of cases are filed against governments. Nevertheless, there is one special issue that I would like to explore further: The importance of legal certainty.

C. Legal Certainty and the Tragedy of the Judiciary

In the law and economics tradition on litigation inaugurated by Friedman,Footnote 97 the initial premise is that the agent choosing to litigate makes a rational choice. A lawsuit for the litigant—whether the plaintiff or the defendant—is a rational decision in which the costs and benefits expected from using this adjudicative mechanism are weighed. With or without lawyers’ assistance—as in small-claims courts—even if intuitively, the litigants try to estimate the probability of success as well as the costs associated with reaching a settlement or continuing to litigate. Both parties know they incur in a margin of error along this estimate.

The outcome of these individual estimates will largely determine the parties’ ability to settle. As in any voluntary exchange, there is room for a bargain when the maximum proposal accepted by the rational defendant exceeds the minimum proposal acceptable to the rational plaintiff. The rational plaintiff will settle when the expected return of the claim is equal to or close to the amount offered by the defendant—assuming risk neutrality. The rational defendant will enter the settlement when the expected value of the action is greater than or near the value that the rational plaintiff is willing to accept—also moving away from complexities related to risk aversion. It is assumed that the joint private cost of litigation is higher than the joint private cost of reaching a settlement. In such a scenario, the settlement will not occur only when the parties’ estimates do not coincide minimally, and thus there is no perceived cooperative surplus to be divided. In other words, the logic of a settlement is similar to the logic of a voluntary exchange, that is, a contract: It will occur only if the parties perceive a cooperative surplus to be distributed.

Thus, on the one hand let π represent the plaintiff in a potential litigation and let us denote, by Uπ, the expected benefit of that litigation at an expected cost, Cπ—for example, initial fees, attorney fees, and expert fees. On the other hand, let Δ represent the defendant of this potential litigation, and let U Δ represent her return from that litigation, which is most often negative—it is a cost—but not necessarily. The costs incurred by Δ to use the judicial system as a dispute settlement mechanism are denoted by C Δ. Consequently, in the event of a litigation, the maximum return for the plaintiff is Uπ − Cπ and U Δ − C Δ for the defendant.

If the parties were able to predict exactly what the outcome of the trial would be, that is in a world in which there were maximum legal certainty—perfect information and a perfect judiciary—there would exist no asymmetry of information between the parties and the issue would be a purely distributive one. In addition, the loss for the defendant would be equal to the gain for the plaintiff and vice versa Uπ = U Δ, and the plaintiff and the defendant could then maximize joint welfare by making an out-of-court settlement and dividing the cost saved from the court dispute Cπ + C Δ, minus the cost of entering into a settlement. Along this simplified approach in which the parties know exactly what the outcome of the judiciary would be, the tendency is to make an out-of-court settlement as it is unreasonable to waste resources by litigating.Footnote 98

Considering the Brazilian experience as an example, this first model may seem unrealistic because the number of settlements in filed cases seem to be much lower than the number of cases that go to trial following the investigation procedure. In 2018, it was estimated that only 11.5% of filed cases in Brazil ended in settlement.Footnote 99 Nevertheless, in the U.S. legal system, the judgment rate is substantially lower, with only 10% of cases being initiatedFootnote 100—that is, more than 90% of cases end in settlements prior to final judgment. As an example, in New York, 98% of bodily injury cases resulting from negligence end in settlement,Footnote 101 while cases regarding medical errors end in settlement 50% of the time even before reaching courts and about 40% are closed during the investigation—that is, before the final judgment—while less than 10% actually go to trial.Footnote 102

Still, the theory must be able to explain why some cases do not end in settlements, be it the larger or the minor portion of the universe. Therefore, we must insert the idea of risk into this evaluation. The judiciary does not generate perfect information regarding how each case will be decided, the parties are not able to interpret these signs perfectly, and there also exists private information between the parties—commonly referred to as asymmetry of information. Moreover, there is evidence that parties and lawyers are consistently optimistic about the outcome of future judgments,Footnote 103 and lawyers may not fully disclose the facts to their clients, as they gain more if there is a dispute—a principal-agent problem. I will interpret this noise as a risk—that is, a measurable amount of probability, as opposed to uncertainty, in which case the risk is not measurable. In this case, we would have:

$$V{R_\pi } = {P_\pi }{U_\pi } - {C_\pi } + {A_\pi }$$

$$V{R_\pi } = {P_\pi }{U_\pi } - {C_\pi } + {A_\pi }$$ $$V{R_\Delta } = {P_\Delta }{U_\Delta } + {C_\Delta } - {A_\Delta }$$

$$V{R_\Delta } = {P_\Delta }{U_\Delta } + {C_\Delta } - {A_\Delta }$$where Pπ and P Δ are the subjective probabilities attributed by the plaintiff and the defendant, respectively, to the success event of the plaintiff; VRπ is the reserve value of the plaintiff—that is, the minimum that he must receive to accept an agreement; VR Δ is the defendant’s reserve value—that is, the maximum she is willing to offer for settlement; and Aπ and A Δ are, respectively, the costs of entering into an agreement for the plaintiff and the defendant. As one may observe, in this model the litigation costs borne by the parties affect their propensity to litigate rather than settle: The higher the costs, the lower the litigation rate, and the lower the cost, the higher the litigation rate. Perceptibly, access-to-justice policies decrease those costs.

Since the litigants are rational agents, the condition of litigationFootnote 104 states that VRπ > VR Δ, or:

$${P_\pi }{U_\pi } - {C_\pi } + {A_\pi } > {P_\Delta }{U_\Delta } + {C_\Delta } - {A_\Delta }$$

$${P_\pi }{U_\pi } - {C_\pi } + {A_\pi } > {P_\Delta }{U_\Delta } + {C_\Delta } - {A_\Delta }$$assuming Uπ = UD, the inequation can be rewritten as:

$${\rm{Pr\ Litigation }} = {\rm{f}}\left( {{P_\pi } - {P_\Delta }} \right)U > \left( {{C_\pi } + {C_\Delta }} \right) - \left( {{A_\pi } + {A_\Delta }} \right)$$

$${\rm{Pr\ Litigation }} = {\rm{f}}\left( {{P_\pi } - {P_\Delta }} \right)U > \left( {{C_\pi } + {C_\Delta }} \right) - \left( {{A_\pi } + {A_\Delta }} \right)$$This simple model has some direct and important implications. First, all other things being equal, the greater the utility of the good in dispute (U), the greater the likelihood of litigation. Second, the probability of litigation is a growing function of the expectations gap—that is, the distance between the assessment of the probability of success by the plaintiff and the defendant (Pπ − P Δ). Third, the less costly a settlement (Aπ + A Δ) and the more expensive it is to litigate (Cπ + C Δ), the greater the probability becomes that a settlement will be reached. Thus, the cheaper the litigation, the greater the probability of litigation.

Clearly, changing the assumptions of the model can substantially alter this scenario. For example, if the parties are risk-averse, the increase in U can proportionally increase more the number of settlements, as the parties would value a more certain return than the expected value of the litigation. But if the damage to one of the parties has already occurred and the action is interpreted as a way of reducing or eliminating such loss, aversion to lossFootnote 105 may work in reverse and thus encourage litigation. While the concavity of the value curve in relation to gains generates risk aversion, the convexity of the value of losses can generate risky behavior and thus result in more litigation. Here, the way in which society or the lawyer poses the question to the potential litigant—the framing—can make a significant difference. Alternatively, a repeated litigant—for example, the government or a telecommunication company—may value the byproduct of the litigation for future cases—precedent or jurisprudence constante—more than the outcome in any single case—dispute resolution. In such a scenario, the value of litigation for one of the parties may be higher than the amount actually discussed in the particular case (Uπ ≠ U Δ), encouraging the litigation according to Inequation 4. The same may occur if the litigant wants to build a reputation of being a hard negotiator and, as a result, is willing to invest in litigation.

Exploring the basic model, legal uncertainty may lead to an increase in the distance between the plaintiff’s subjective probability attributed to his own success (Pπ) and the probability attributed to the same event by the defendant P Δ. An increase in the expectations gap increases the expected return on litigation and, all other things being equal, the amount of litigation. If there are adequate incentives for judges to invest in legal certainty, the expansion of the number of cases would cause precedents or jurisprudence constante to be formed, which, for a time, would inform the plaintiff and defendant at a low cost as to which set of rules would be applied by the judiciary in similar cases in the future, therefore converging the subjective probabilities Pπ → P Δ. At the limit, assuming the absence of private information, Pπ = P Δ.

As discussed in a previous work,Footnote 106 the law of a given society is the result of its experiences and values over time. The larger the number of legal rules accrued by a society and applied by the judiciary, the greater the number of situations in which agents can foresee the probable outcome of a particular conflict if taken to the judiciary; therefore, it is easier to allocate risk or enter into an out-of-court settlement. This legal certainty allows for long-term planning, better allocation of risks, discouragement of opportunistic behavior, and—ultimately—cooperation.

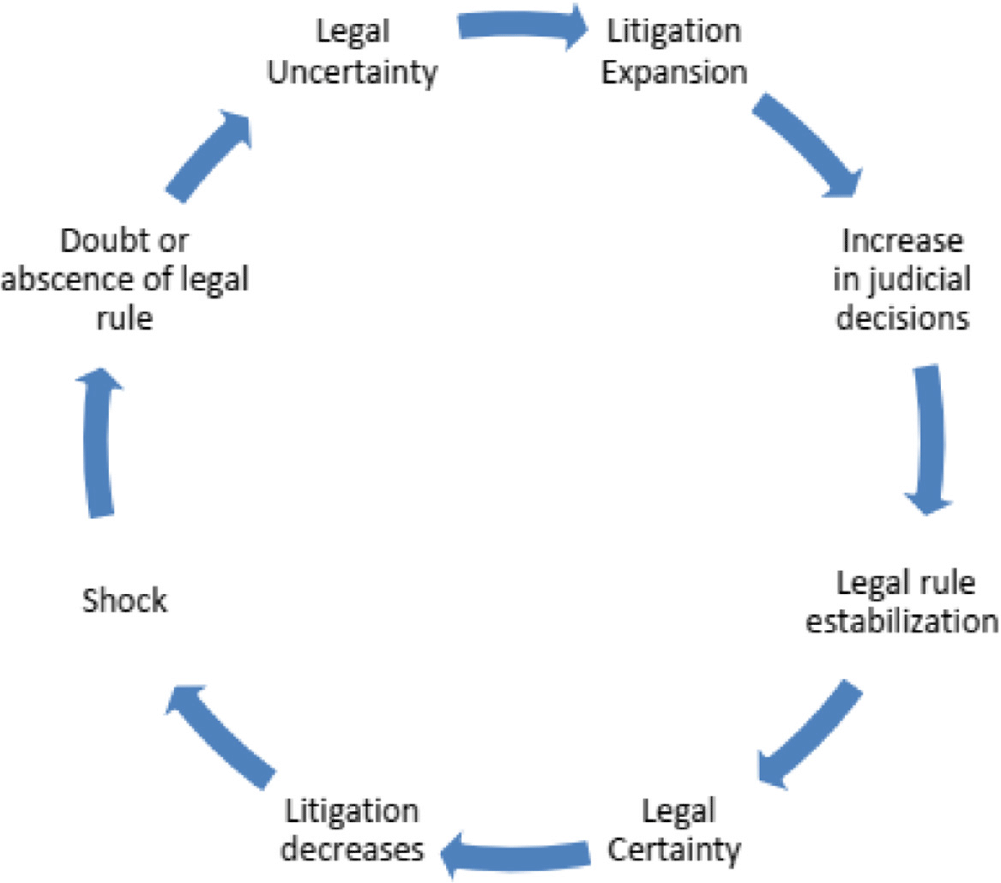

Nevertheless, the behavior inducement effect presupposes that the legal rule is previously established and that it is known to or can easily be discovered by all interested parties. This is not always the case. Suppose there is a shock that causes the predictability of legal rules in a particular field of law to fall. This may result from a Supreme Court change of position due to a new composition, a change in legislation—such as the introduction of a new civil code—or unexpected changes in socioeconomic conditions—such as the 2020 pandemic crisis. Any of these shocks can immediately render obsolete part of the stock of existing legal rules that will lead to legal uncertainty. Assuming the legislature does not address the issue in a timely manner, this uncertainty will increase the number of cases brought before the judiciary, as the parties will find it more difficult to foresee what the legal rule applicable to their specific case would be, and, therefore, what the expected value of a particular settlement would be. The result will be a temporary increase in litigation that will force the judiciary to reevaluate the issue until it settles on a new rule or reaffirms the old one, thus eliminating legal uncertainty. Once legal certainty is reestablished, litigation in that particular area of law will decrease, and a new litigation equilibrium will be reached until the next shock occurs, when the cycle will then resume. This simple dynamic between litigation and legal certainty can be easily illustratedFootnote 107 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. The Litigation Cycle.

From a tragedy of the judiciary perspective, policymakers and judges should be working relentlessly to achieve as much legal certainty as possible and, when a shock is inevitable, reduce the expansion phase and decrease the contraction phase of the litigation as much as possible by quickly re-establishing the applicable legal rule. The litigation cycle is inevitable as a whole, but a comprehension of the economic nature of courts and the impact of legal uncertainty on access to justice should be more than enough to convince legal scholars that legal certainty is the most important feature of any legal system.Footnote 108

Notwithstanding this, if the legal rule applied to each case varies along with the preferences of each judgeFootnote 109 or the judiciary is too noisy to create and apply a single legal rule in a timely manner,Footnote 110 and the distribution of cases is random, then the plaintiff and the defendant may experience great difficulty in estimating Pπ and P Δ, which may subsequently increase the expectations gap. At the limit, such an estimate may be impossible, and the parties would be faced with uncertainty.

The difficulty of estimating the probability of success of a demand may trigger a cognitive limitation known as a bias of unrealistic optimism or even comparative optimism.Footnote 111 The bias of optimism is a cognitive limitation already identified in the literature in various contexts, according to which the human brain is programmed to be optimistic—that is, on average, people believe they are exposed to minor risks of experiencing negative events than are others. Because they are optimistic, people can, for example, invest less in prevention by utilizing fewer contraceptive methods,Footnote 112 not wear seatbelts, or drive in excess of the speed limit.Footnote 113 In the present case, an optimistic plaintiff and an optimistic defendant may overestimate their respective chances of success, therefore diminishing or simply eliminating the possibility of reaching a settlement. The more difficult it is to estimate these probabilities, the greater the chance becomes that the optimism bias will be more relevant.

Legal uncertainty, however, affects not only the parties’ ability to estimate their success probabilities, but also their ability to estimate what is legally available as a result of the litigation itself—that is, U. Faced with the absence of clear legal rules, potential plaintiffs—optimists or not—may initiate actions to reduce interest on a consumer loan even if such interest is in line with the market, request that a judge compel the other party to negotiate a discount on the school monthly fee, request $500,000 from a hospital for alleged moral damages resulting from supposedly rough medical care even though the treatment was effective, and so on. Without a clear parameter as to what is or is not a valid claim,Footnote 114 the plaintiff’s imagination and optimism are the limit for what can be claimed in courts. Entrepreneurial lawyers will certainly play a significant role here.

In this sense, the existence of legal uncertainty leads to a reduction in the number of settlements and an increase in the number of tried cases. According to the litigation-cycle logic, this litigation expansion will be contained only when the judiciary itself starts applying the same rules to the same cases and thus clearly sends signals to the parties regarding its prospective behavior. Without internal coherence, legal uncertainty could lead to an increase in the use of the judiciary and, in effect, its overuse. Old issues will be repeatedly litigated through a vicious circle that will create a negative feedback that, on its turn, will increase legal uncertainty and result in the inevitable (over)use of the judiciary.

The problem of overexploitation of the judicial system due to legal uncertainty is even more likely when we consider that, as a rule, public policies of free access to the judicial system, such as legal aid, public defenders, creation of special courts, and expected decrease in the average value of attorney’s fees act on the right side of Inequation 4—that is, they decrease the difference: (Cπ + CΔ) − (Aπ + AΔ). As litigation becomes cheaper, the quantity demanded of public adjudicative services increases and the inclusive public policies, all other things being equal, only contribute to the tragedy of the judiciary.

These public policies focus on reducing the private costs of using the judicial system in order to expand access, increasing the likelihood of litigation at first. Following the litigation cycle logic, this initial increase in litigation would only be reflected in a greater protection of community’s rights as a whole if the additional litigation turned into legal certainty and, consequently, generated a retraction of litigation at a later stage resulting from the increased spontaneous compliance (self-composition). Otherwise, such policies reinforce and subsidize the free access to the resource system, but end up generating shortages of judicial services due to the excess of demand (congestion).

As discussed, the bundled product law-court is a scarce rival resource in that the more it is used, the more difficult it is for others to use it. However, when an individual litigant decides to take his case to court, he considers only his private costs and benefits. The litigant does not compute the social cost of his litigation, which includes the amount of time that other more or less important cases will have to wait until his case is decided. Just as the cow owner in the tragedy of the commons metaphor has the incentive to drive as many cattle as possible to pasture, litigants have the incentive to litigate as long as their expected private marginal benefits are greater than their expected private marginal costs. Their individual contribution to court congestion is externalized to society.

The combination of legal uncertainty with subsidized costs to litigate generates incentives for the parties to litigate too much, demanding public adjudicative services above the installed capacity of the judiciary. This excess demand generates queues and lower-quality judicial decisions. Litigants who do not fully bear the social cost of litigation generate queues and end up paying with their time. The result then becomes the endemic judicial difficulty of settling issues within a reasonable period of time, which has become known as the “judicial crisis” worldwide. Considering that adjudicative services are merit goods, without the proper investment in legal certainty, the expansion of litigation is followed neither by a period of retraction nor legal certainty. Therefore, underinvestment in uniformization of the law contributes directly to the overexploitation of the judicial system, and its congestion equals non-access to adjudicative services.

Assuming there are limited resources that a given society can allocate to provide adjudicative services—that is, a supply solution to the congestion problem is limited—then, we need a demand-side solution. Nonetheless, since adjudicative services are merit goods, most societies will be unwilling to restrict access to justice, effectively limiting the strategies available from the demand side too. In this sense, alongside collective actions, legal certainty can be seen as the best tool any jurisdiction has to decrease court congestion without unduly interfering with the adjudication of rights. In sum, under those conditions, legal certainty is the best solution or at least the best mitigating strategy for the tragedy of the judiciary.

D. The Adverse Selection Problem: The Other Face of the Tragedy of the Judiciary

Court delay is only one more obvious aspect of the tragedy of the judiciary. There is another aspect that can be even more serious and pernicious from the perspective of social justice as well as the economic function of the judiciary as a guarantor of political and private bargaining: The adverse selection problem resulting from court congestion and the transformation of the judiciary into a mockery of the law. On the one hand, the idea here is that once the time element is introduced in the analysis, the biggest the court delay, the lower the present value of a claim to the plaintiff. On the other hand, the biggest the court delay, the lower the present value of the obligation to the defendant is.Footnote 115 In this scenario, the decreasing value of a right will prevent marginal plaintiffs from using the adjudicative system, while, at the same time, it will encourage obligations holders to litigate only to benefit from the diminishing effects of court delay.

In Section C above, I analyzed the incentives structure for settling among plaintiff and defendant as well as the impact of underinvestment in legal certainty on this incentive structure. As explained, the result was an increase in the incentive to litigate, which leads to overuse of the judiciary and the so-called tragedy of the judiciary. At that time, however, I did not consider the mere fact that the time gap between the beginning and the end of a demand would singlehandedly reduce the present value of a possible action and therefore reduce the expected return of litigation. In other words, the parties are not indifferent to judicial delays when deciding whether or not to enter into a settlement; the longer a filed case takes to be judged, the lower its present value becomes to those vindicating their rights. The chilling effect of judicial delay was first noticed by PosnerFootnote 116 and by Cappelletti and Garth,Footnote 117 and was later developed by Priest,Footnote 118 the last of whom I will follow here.

In order to take into consideration the time value of money, we can modify the previously discussed model to include a discount rate to U, making the present value of the lawsuit dependent upon the magnitude of court delay and the time value of money, which will be represented by an interest or discount rate. Adapting Inequation 4, we have:

$${\rm{Pr}}\,{\rm{Litigation}}\,{\rm{(with}}\,{\rm{gap)}} = {\rm{f}}({P_\pi } - {P_\Delta }){U \over {{{\left( {1 + r} \right)}^t}}} > ({C_\pi } + {C_\Delta }) - ({A_\pi } + {A_\Delta })$$

$${\rm{Pr}}\,{\rm{Litigation}}\,{\rm{(with}}\,{\rm{gap)}} = {\rm{f}}({P_\pi } - {P_\Delta }){U \over {{{\left( {1 + r} \right)}^t}}} > ({C_\pi } + {C_\Delta }) - ({A_\pi } + {A_\Delta })$$where r is a discount rate per period and t is the number of periods between the filing of the lawsuit and its judgment. Here, the time gap between the right violation and the lawsuit filing date is discarded for the sake of simplicity.

Inequation 5 shows that the resolution period—that is, the time required for the adjudicative system to settle the issue—per se is capable of reducing the present value of a lawsuit—hence, the probability of a dispute arising. Ceteris paribus, there is an inverse relationship between the resolution period and the probability of litigation. Court congestion—or judicial delay—increases the probability of settlement, while judicial celerity increases the probability of litigation. This non-intuitive, inverse relationship suggests the existence of a dynamic interrelationship between the resolution period and the litigation rate.

The faster the judicial system, the greater the present value of a lawsuit, and therefore the greater the probability of a lawsuit being filed. Still, the more actions are filed, the greater the burden on the judiciary becomes, which forces it to slow down. This subsequently increase in the resolution period—an increase in t—decreases both the present value of lawsuits and the future demand for adjudicatory services. Thus, according to theory, changes in the resolution period should create compensatory effects on the number of lawsuits filed and vice versa. This relationship suggests that, given an installed capacity to provide judicial services, there must exist an equilibrium between litigation and judicial delay in each jurisdiction: A congestion equilibrium.

Just as legal uncertainty leads to litigation expansion, which should lead to law uniformity that leads to legal certainty, followed by litigation retraction—the litigation cycle—the litigation level should float above and below the congestion equilibrium level as the resolution period changes. On the one hand, the delay reduction—resolution celerity—causes marginal litigators to initiate litigation since the present value of lawsuits  ${U \over {{{\left( {1 + r} \right)}^t}}}$ may increase and cause the congestion to reach another equilibrium level. On the other hand, if the judiciary is too slow, the present value of lawsuits is reduced and marginal litigators either settle or refrain from litigating, which reduces judicial congestion and reestablishes the equilibrium level.

${U \over {{{\left( {1 + r} \right)}^t}}}$ may increase and cause the congestion to reach another equilibrium level. On the other hand, if the judiciary is too slow, the present value of lawsuits is reduced and marginal litigators either settle or refrain from litigating, which reduces judicial congestion and reestablishes the equilibrium level.