From 2017 to 2021, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) faced five Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreaks in different provinces, including the Equateur Province, North and South Kivu and Ituri in the Eastern regions, and the Bas-Uele Province.Reference Adepoju1 The mortality rates of these outbreaks ranged between 42.31 and 65.83%.2–6 The 2018–2020 EVD outbreak in the Eastern regions was the second largest after the 2013–2018 epidemic.Reference Wadoum, Sevalie, Minutolo, Clarke, Russo and Colizzi5 As of 21 June 2020, at the end of this outbreak, the DRC reported 3470 EVD cases and 2287 deaths.2–4 The Equateur Province was particularly affected by a double outbreak of both EVD and COVID-19 in 2020.

Studies conducted in different DRC provinces affected by EVD have found high prevalence rates of depression, psychological distress and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms among adults.Reference Kaputu-Kalala-Malu, Musalu, Walker, Ntumba-Tshitenge and Ahuka-Mundeke7–Reference Cénat, Farahi, Dalexis, Darius, Bukaka and Balayulu-Makila10 For instance, studies conducted in health zones affected by EVD in the Equateur Province reported that 62.03, 45.58 and 58.81% of adults experienced symptoms of depression, psychological distress and PTSD, respectively.Reference Cénat, McIntee, Guerrier, Derivois, Rousseau and Dalexis9–Reference Cénat, Noorishad, Dalexis, Rousseau, Derivois and Kokou-Kpolou11 In addition, studies conducted in the DRC Eastern regions found that 23.5 to 24.3% of adults experienced symptoms of depression, and 24.1 to 53.7% exhibited symptoms of PTSD.Reference Kaputu-Kalala-Malu, Musalu, Walker, Ntumba-Tshitenge and Ahuka-Mundeke7–Reference Cénat, Felix, Blais-Rochette, Rousseau, Bukaka and Derivois12,Reference Lawry, Stroupe Kannappan, Canteli and Clemmer13

Studies conducted among populations affected by EVD in DRC and elsewhere also found that being a woman, living in a rural area, being unemployed, being an EVD survivor and being aged 50 years and above were associated with symptoms of depression, anxiety and other mental health issues.Reference Kaputu-Kalala-Malu, Musalu, Walker, Ntumba-Tshitenge and Ahuka-Mundeke7--Reference Cénat, McIntee, Guerrier, Derivois, Rousseau and Dalexis9--Reference Bah, James, Bah, Sesay, Sevalie and Kanu14--Reference Secor, MacAuley, Stan, Kagone, Sidikiba and Sow16 However, the most important risk factors related to depression, anxiety, PTSD, psychological distress and other mental health issues among populations affected by EVD were the degree of exposure to the virus and the related stigmatisation.Reference Cénat, McIntee, Guerrier, Derivois, Rousseau and Dalexis9--Reference Cénat, Noorishad, Dalexis, Rousseau, Derivois and Kokou-Kpolou11--Reference James, Wardle, Steel and Adams15

Although studies have explored the mental health of adults in populations affected by EVD, no studies have been conducted on the prevalence and factors associated with depression, anxiety and other mental health issues among adolescents in communities affected by EVD. However, adolescents are among those most affected when populations are struck by EVD.Reference Amuzu, James, Bah, Bayoh and Singer17 Indeed, children and adolescents are particularly at risk of financial, psychosocial and health consequences of EVD.Reference Amuzu, James, Bah, Bayoh and Singer17,Reference Denis-Ramirez, Sørensen and Skovdal18 In addition to the risk of being infected, they may become orphans, lose their homes, lose the opportunity to attend school, and experience various forms of EVD-related stigma and psychological stressors.Reference Amuzu, James, Bah, Bayoh and Singer17–Reference Evans and Popova19 For example, in a qualitative study of youth experiences in populations affected by EVD, participants reported social exclusion, stigma, fear and social isolation, among other stressors.Reference Denis-Ramirez, Sørensen and Skovdal18 The two published studies (both conducted in Sierra Leone) that attempted to explore mental health issues among adolescents in populations affected by EVD only presented limited cross-sectional results. First, Amuzu and colleagues reported that mood changes were more prevalent in EVD survivors than in non-infected youth.Reference Amuzu, James, Bah, Bayoh and Singer17 Second, a study demonstrated that youth EVD survivors experienced higher scores of depression and anxiety than youth with close contact with EVD patients.Reference Shantha, Canady, Hartley, Cassedy, Miller and Angeles-Han20 The prevalence and factors associated with mental health problems have not been studied in the DRC or elsewhere.

The present study

Given the critical gap in the literature, the present study aimed to document the prevalence and the risk and protective factors associated with depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents living in the health zones affected by EVD in the DRC Equateur Province during the COVID-19 pandemic, using a two-wave longitudinal design. We hypothesised that: (a) there would be a high prevalence of depression, anxiety and comorbid symptoms among adolescents living in areas affected by EVD and COVID-19; (b) the degree of exposure to EVD and stigmatisation related to EVD would be the most important predictors of depression and anxiety symptoms; and (c) social support would negatively predict symptoms of depression and anxiety, given its vital role in those communities’ well-being.Reference Mohammed, Sheikh, Gidado, Poggensee, Nguku and Olayinka21

Method

Design and procedure

Based on estimates from the National Statistics Institute, participants were recruited according to a four-stage stratified sampling based on: (a) the proportions of girls and boys in affected settings, (b) the demographic weights of the rural and urban areas affected by the outbreak, (c) the ages of participants in affected settings (12–17 years) and (d) the school enrolment rate. Given the lack of data on the population of the Equateur Province, this four-stage stratified sampling was used to ensure adequate gender, urban/rural and age representation of participants and to consider that not all adolescents are enrolled in school. The baseline survey (T1) was conducted from 11 March to 23 April 2019, 7 months after the end of the 2018 EVD outbreak. The follow-up survey (T2) was conducted about 17 months later, from 12 August to 26 September 2020. Two psychologists coordinated the research assistants in the recruitment of participants. During T1, we collected data to facilitate the conduct of the follow-up survey (e.g. schools, addresses). However, many times addresses were non-existent. So, we noted details about areas and location points (e.g. school, church, small stores closest to the house, community leader) to help the coordination of the recruitment. T2 was conducted while the province of Equateur was encountering cases of both EVD and COVID-19. All the research assistants wore personal protective equipment, washed their hands after each interview and maintained physical distance. Back-translation methods were used to cross-culturally adapt survey questionnaires into Lingala. The entire translation process was carried out by a panel of seven professors from DRC universities in linguistics, psychology, psychiatry and education. Before the use of the questionnaire in the survey, cognitive interviews were conducted to ensure that participants understand the measures well. The psychometric properties of all the measures were explored and found to be reliable, valid and accurate. The same process was followed for other languages, and the questionnaires were also available in French, Tshiluba, Swahili, Kikongo and English. Considering the school enrolment rates in urban and rural areas, research assistants reached 67.33% of the participants in school, on weekdays, and 32.67% through the door-to-door method. Regarding the demographic characteristics of participants, there were no significant differences between school recruitment and the door-to-door method. Twenty-six French- and Lingala-speaking research assistants trained for 2.5 days in different areas related to the survey, including ethical practices, and collected data in Bikoro, Iboko and Wangata, the three health zones in Equateur affected by EVD outbreaks. Written informed parental consent (from parents or guardians) was obtained for all participants. The research protocol received ethical approval from the University of Ottawa Research Ethics Board (ethics file number: H-01-19-1893), the University of Kinshasa and the National Institute of Biomedical Research.

Participants

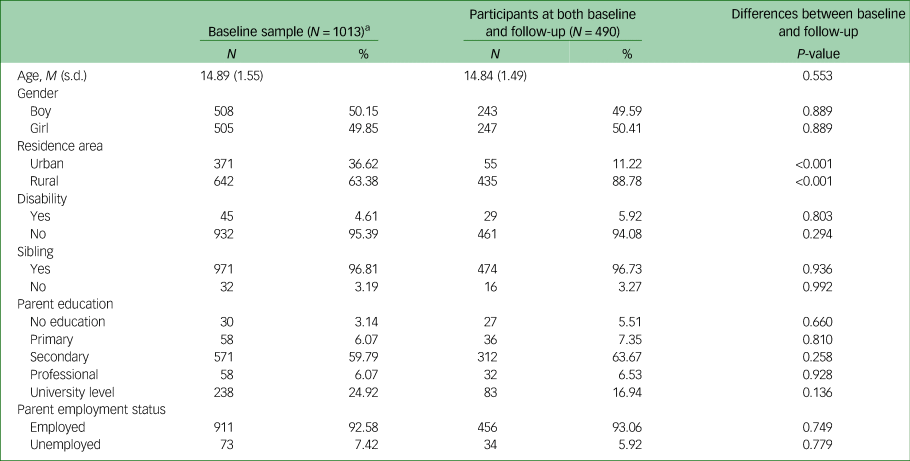

Participants were included if they: (a) were living in one of the 18 urban and rural areas affected by EVD since 1 March 2018; (b) were able to speak Lingala or French; (c) were aged 12 to 17 years old; (d) were not experiencing a mental health disorder that interfered with their judgement; (5) did not have any medical or legal constraints. The baseline sample (T1) included 1013 participants (49.85% girls; 50.15% boys). Owing to the nomadic culture and the problems of cadastral registration in the Equateur Province, especially in rural areas, a previous plan was developed to recruit in T2 adolescents who had participated in T1. This plan allowed the recording of landmarks and addresses (e.g. schools, churches, health centres, offices and small businesses). The objective was to recruit at least 44% of the adolescents that had participated at baseline. A total of 490 participants completed the survey at follow-up (T2: 50.41% girls, 49.59% boys; retention rate = 48.4%). Sociodemographic characteristics between baseline (T1) and follow-up (T2) were compared and found to be similar, except that the proportions of those living in urban and rural areas at follow-up were different from those at baseline (Table 1).

Table 1 Sample characteristics at baseline

a. Sample characteristics of participants who completed baseline measures.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics

The sociodemographic characteristics assessed were gender, age, educational level, residence area, number of siblings and physical disabilities. In addition, the education level and employment status of the participants’ parents were documented.

The Children's Depression Inventory (CDI)

The CDI is a 27-item scale that measures cognitive, affective and/or behavioural symptoms of depression among children and adolescents aged 7 to 17 years old (e.g. self-hate, sadness, sleep disturbance).Reference Kovacs and Beck22,Reference Kovacs23 Responses are rated on a three-point scale (0, 1, 2) reflecting increasing disturbance severity. Total scores range between 0 and 54, with higher scores indicating increased severity of depressive symptoms. A cut-off score of ≥19 was used for severe depressive symptoms in community-based samples.Reference Doerfler, Felner, Rowlison, Raley and Evans24 The Cronbach's α in the sample was 0.71 at baseline and 0.73 at follow-up.

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

The BAI is a 21-item scale that measures the severity of anxiety symptoms (e.g. fear of dying, nervousness, being terrified).Reference Beck, Epstein, Brown and Steer25,Reference Beck and Steer26 It has been widely used in youths and adults across several cultural settings. Each item is rated on a three-point scale (0, 1, 2) reflecting increasing severity of anxiety symptoms. Total scores ranges from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating increased severity of anxiety. A cut-off score of ≥19 was used to identify participants with moderate to severe anxiety symptoms.Reference Beck, Epstein, Brown and Steer25 The Cronbach's α in the sample was 0.97 at both baseline and follow-up.

Exposure to Ebola Scale (EBS)

The EBS is a 17-item scale that measures the level of exposure to the Ebola virus (e.g. ‘Has a member of your family fallen ill because of the Ebola virus?’). This scale was inspired by the Trauma Exposure Scale, which assesses dimensions of exposure to a potentially traumatic event.Reference Cénat and Derivois27 Responses were rated on a dichotomous scale (‘yes’ or ‘no’). The EBS demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the present sample. Cronbach's α in the current sample was 0.86 at baseline and 0.96 at follow-up.

Stigmatisation related to EVD

A stigmatisation related to EVD and COVID-19 scale has been widely used in the DRC Ebola and COVID-19 context.Reference Cénat, McIntee, Guerrier, Derivois, Rousseau and Dalexis9--Reference Cénat, Farahi, Dalexis, Darius, Bukaka and Balayulu-Makila10--Reference Cénat, Rousseau, Bukaka, Dalexis and Guerrier28, Reference Cénat, Noorishad, Kokou-Kpolou, Dalexis, Hajizadeh and Guerrier29 It includes 20 items with a five-point Likert response type, ranging from ‘never’ (0) to ‘always’ (4), e.g., ‘Someone refused to talk to you … ’; ‘A company refused to hire you … ’. Cronbach's α in the current sample was 0.97 at baseline and 0.98 at follow-up.

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS)

The MSPSS is a 12-item questionnaire that evaluates three sources of social support: family (items 3, 4, 8 and 11), friends (items 6, 7, 9 and 12) and significant others (items 1, 2, 5 and 10).Reference Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet and Farley30 Each item is rated on a seven-point scale: from ‘very strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘very strongly agree’ (7). The Cronbach's α in our sample was 0.91 at baseline and 0.94 at follow-up.

Statistical procedure

Data from the longitudinal observations were analysed. Missing observations of the longitudinal data were imputed using multiple imputation procedures. We first computed descriptive statistics to estimate the prevalence of severe symptoms of depression and anxiety and of comorbid depression–anxiety symptoms, according to the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample, using Pearson's chi-squared and Fisher's exact tests at baseline and follow-up. The prevalence of comorbid depression and anxiety was estimated using contingency tables for participants who had severe symptoms of both depression and anxiety. The comorbidity group was compared with a group of participants who had only anxiety, only depression, or no severe symptoms of depression or anxiety. The prevalence rates and mean differences across time were tested using McNemar's test and paired t-tests, respectively.

We used hierarchical linear generalised estimating equation (GEE) models to test for changes in mean anxiety and depression over time. An autoregressive correlation structure was selected as it was suitable for repeated measures designs.Reference Gary31 Model 1 examined the longitudinal changes in mean anxiety and depression symptom scores from baseline to follow-up. Model 2 tested associations between sociodemographic variables and outcome variables (mean anxiety and depression symptom scores). Exposure to Ebola was added to model 3. Ebola stigmatisation was added to model 4, and social support was included in model 5. All model fits were compared using the quasi-likelihood under independence model criterion. Age, exposure to Ebola, social support and stigmatisation related to Ebola were time-varying predictors. Standardised scores for continuous variables were used for the GEE analyses. Sociodemographic variables, including gender, disability, residence area, having a disability, parents’ education and employment status, were time-invariant predictors; hence, the baseline variables were used for all the analyses. We also used two models to test the moderating effect of social support on the associations of Ebola stigmatisation and exposure to Ebola with anxiety and depression after controlling for sociodemographic factors. We used IBM SPSS Statistics 28 for all statistical analyses.

Results

In total, 1013 participants completed the baseline measurement (T1), and 490 participants aged 12–17 years (M = 14.84, s.d. = 1.49) completed both T1 and T2. Of the participants, 50.41% were girls, 88.78% were living in rural areas, 94.08% did not have disabilities and 96.73% had siblings. Participants’ sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Anxiety and depression across time

Paired sample t-tests were used to test mean differences across time. Mean anxiety scores significantly decreased from baseline (M = 13.92, s.d. = 14.83) to follow-up (M = 9.99, s.d. = 12.73); t(489) = 4.67, P < 0.001, d = 0.21 (95% CI: 0.12, 0.30). However, mean depression scores significantly increased from baseline (M = 19.98, s.d. = 6.70) to follow-up (M = 24.77, s.d. = 4.71); t(489) = −13.13, P < 0.001, d = −0.59 (95% CI: −0.69, −0.50). McNemar's test was used to test differences in prevalence across time. The prevalence rates of moderate-to-severe anxiety symptoms at baseline and follow-up were 36.33% and 24.90%, respectively (z = 4.06, P < 0.001); those of moderate-to-severe depression symptoms at baseline and follow-up were 56.94% and 91.43%, respectively (z = −11.37, P < 0.001), and those of moderate-to-severe comorbid anxiety and depression symptoms at baseline and follow-up were 26.12% and 23.27%, respectively (z = 1.05, P = 0.294).

The prevalence rates of anxiety symptoms at baseline (χ 2 = 3.73, P = 0.054) and follow-up (χ 2 = 0.53, P = 0.465) were not significantly different statistically between boys (T1 = 32.10%, T2 = 26.34%) and girls (T1 = 40.49%, T2 = 23.48%). The prevalence of anxiety symptoms in girls decreased over time (χ 2 = 16.42, P < 0.001), whereas the prevalence in boys did not change over time (χ 2 = 1.95, P = 0.163). The prevalence rates of depression symptoms at baseline (χ 2 = 1.06, P = 0.304) and follow-up (χ 2 = 1.81, P = 0.178) were not statistically significantly different between boys (T1 = 59.26%, T2 = 89.71%) and girls (T1 = 54.66%, T2 = 93.12%). However, the prevalence of depression symptoms in both boys and girls increased over time (χ 2 = 58.29, P < 0.001; and χ 2 = 94.69, P < 0.001, respectively). Moreover, the prevalence rates of comorbidity at baseline (χ 2 = 3.04, P = 0.081) and follow-up (χ 2 = 0.28, P = 0.598) were not statistically significantly different between boys (T1 = 22.63%, T2 = 24.28%) and girls (T1 = 29.55%, T2 = 22.27%). No changes over time were observed regarding the prevalence of comorbidity in boys or girls (χ 2 = 0.18, P = 0.669; and χ 2 = 3.42, P = 0.065, respectively).

The prevalence of anxiety symptoms at baseline was higher in individuals living in urban areas compared with those living in rural areas (65.45% v. 32.64%; χ 2 = 22.73, P < 0.001), whereas the prevalence of anxiety symptoms at follow-up was higher in individuals living in rural areas compared with those living in urban areas (27.13% v. 7.27%; χ 2 = 10.29, P = 0.001). The prevalence of anxiety symptoms in individuals living in urban areas decreased over time (χ 2 = 40.23, P < 0.001), whereas there was no such change for those living in rural areas (χ 2 = 3.16, P = 0.075). The prevalence of depression symptoms at baseline was higher in individuals living in urban areas than in those living in rural areas (87.27% v. 53.10%; χ 2 = 23.25, P < 0.001). However, there was no significant differences between individuals living in rural (91.49%) and urban (90.91%) areas in the follow-up (χ 2 = 0.02, P = 0.801). The prevalence of depression symptoms in individuals living in rural areas increased over time (χ 2 = 160.06, P < 0.001), whereas no such changes were found for those in urban areas (χ 2 = 0.37, P = 0.541). The prevalence of comorbid depression and anxiety symptoms at baseline was higher in individuals living in urban areas than in those living in rural areas (58.18% v. 22.07%; χ 2 = 33.00, P < 0.001); however, the prevalence of comorbidity at follow-up was higher in individuals living in rural compared with urban areas (25.29% v. 7.27%; χ 2 = 8.88, P = 0.003). Although the prevalence of comorbidity in individuals living in urban areas decreased over time (χ 2 = 32.37, P < 0.001), no such changes over time were found for those living in rural areas (χ 2 = 1.25, P = 0.264). Prevalence estimates for all sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Prevalence rates of anxiety and depression symptoms and comorbid anxiety–depression according to sociodemographic characteristics of the sample

GEE results for anxiety

The final GEE model showed that anxiety symptoms decreased over time (B = −3.92, P < 0.001). Exposure to Ebola (B = 0.97, P = 0.028) and stigmatisation related to Ebola (B = 5.41, P < 0.001) were significantly associated with anxiety symptoms, whereas social support was negatively associated with anxiety symptoms (B = −1.13, P = 0.004). Based on the changes in the strength of the relationship between exposure to Ebola and anxiety symptoms from model 4 (B = 1.14, P = 0.007) to model 5 (B = 0.97, P = 0.028) after the inclusion of social support in the final model, it seems that social support can be regarded as a protective factor. Gender was not statistically associated with anxiety symptoms (B = 0.89, P = 0.236). Living in rural areas (B = −3.95, P = 0.002) and having a secondary education (B = −5.60, P = 0.007) were negatively associated with anxiety symptoms. Moreover, having a disability was positively associated with anxiety symptoms (B = 5.47, P = 0.003). Table 3 displays the results for anxiety. Moderation analysis showed that social support did not moderate either the association between exposure to Ebola and anxiety symptoms or that between Ebola stigmatisation and anxiety symptoms (Table 5).

Table 3 Hierarchical linear GEE for anxiety symptomsa

QIC, quasi-likelihood under independence model criterion.

a. References: time, follow-up; gender, boy; residence area, urban; disability, no; sibling, no; parents’ education, no formal education; employment status, employed.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

GEE results for depression

The final GEE model showed that depression symptoms increased over time (B = 4.79, P < 0.001). Stigmatisation related to Ebola was positively associated with depression symptoms (B = 0.45, P = 0.009). Social support was negatively associated with depression symptoms (B = −0.98, P < 0.001). Gender was not statistically associated with depression symptoms (B = 0.21, P = 0.553). Living in rural areas was negatively associated with depression symptoms (B = −2.24, P < 0.001), suggesting that living in urban areas is a risk factor for depression symptoms. Table 4 shows the GEE results for depression. Moderation analysis showed that high levels of social support attenuated the impact of Ebola stigmatisation on the development of depression symptoms (B = −0.67, P < 0.001). However, the interaction between social support and exposure to Ebola was not statistically significant (Table 5).

Table 4 Hierarchical linear GEE for depression symptomsa

QIC, quasi-likelihood under independence model criterion.

a. References: time, follow-up; gender, boy; residence area, urban; disability, no; sibling, no; parents’ education, no formal education; employment status, employed.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Table 5 Results of moderation analyses for anxiety and depression symptomsa

a. References: time, follow-up; gender, boy; residence area, urban; disability, no; sibling, no; parents’ education, no formal education; employment status, employed.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to examine changes over time in the prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms and their comorbidity, as well as possible risk and protective factors, in adolescents living in zones affected by EVD since the discovery of the virus in 1976. First, our results showed an increase in depression symptoms over time: at baseline, six in ten participants reported depressive symptoms, compared with nine in ten at follow-up. By contrast, anxiety symptoms decreased from baseline to follow-up. Two in five children and adolescents initially reported moderate-to-severe anxiety symptoms, compared with one in four at follow-up. In addition, the changes in the prevalence of the comorbidity did not change significantly. Regardless of change over time, all three were highly prevalent at both time points. Although the results cannot be compared with those of other longitudinal studies done in youth, as there are no such studies, we could compare them to those of previous cross-sectional studies conducted in adults affected by EVD and in adult survivors of the disease.Reference Cénat, Noorishad, Dalexis, Rousseau, Derivois and Kokou-Kpolou11

The results on depression were surprising in that they strayed from patterns found in individuals over 18 in the DRC, showing no increase in mental distress in this population during the time in question.Reference Cénat, Kokou-Kpolou, Mukunzi, Dalexis, Noorishad and Rousseau8 The prevalence estimates of depression symptoms observed at both T1 and T2 were also higher than those reported by multiple previous studies. Indeed, Keita and colleagues found that 10% of their sample had mild-to-severe depression.Reference Keita, Taverne, Sy Savané, March, Doukoure and Sow32 Another study reported that 47.2% of Ebola survivors in the northern region of Sierra Leone were diagnosed with significant depression symptoms.Reference Bah, James, Bah, Sesay, Sevalie and Kanu14 A meta-analysis of Ebola survivors in African countries found a 15% prevalence for depression.Reference Acharibasam, Chireh and Menegesha33 Another meta-analysis found that 19.92% of communities affected by EVD presented significant symptoms of depression.Reference Cénat, Felix, Blais-Rochette, Rousseau, Bukaka and Derivois12 Various hypotheses could explain these differences. First, the high levels of EVD-related stigmatisation experienced by participants in this study could reflect an adverse social context that may have affected the youth more because of the difficulties in achieving the developmental tasks associated with this period of life (studies, work and dating).Reference Racine, McArthur, Cooke, Eirich, Zhu and Madigan34 Second, the reverse trends for anxiety symptoms may be associated with the fact that when survival issues are less pre-eminent and some safety is achieved, mourning processes that had been delayed may finally begin, reactivating sadness over the multiple losses endured.

The prevalence of anxiety symptoms in adolescents at T1 and T2 in our study was higher than those reported for adult populations affected by EVD in previous studies.Reference Cénat, Farahi, Dalexis, Darius, Bukaka and Balayulu-Makila10–Reference Bah, James, Bah, Sesay, Sevalie and Kanu14 A meta-analysis showed that 14% of EVD survivors experienced significant symptoms of anxiety,Reference Acharibasam, Chireh and Menegesha33 whereas a study in Sierra Leone of adult EVD survivors and healthcare workers found that 83.3% of survivors met criteria for a diagnosis of anxiety.Reference Ji, Ji, Duan, Li, Sun and Song35 However, other studies have been more consistent with our findings. A study of EVD survivors in eastern DRC found that the prevalence of anxiety was 33.3% in their sample.Reference Kaputu-Kalala-Malu, Musalu, Walker, Ntumba-Tshitenge and Ahuka-Mundeke7

We also found that anxiety symptoms decreased over time, whereas depression symptoms increased from T1 to T2. The changes in anxiety observed in this study were consistent with the findings of a study that showed a decrease in mental distress over time among adults in areas affected by EVD.Reference Cénat, Farahi, Dalexis, Darius, Bekarkhanechi and Poisson36 This decrease in anxiety could have been associated with a decrease in the actual threat level, or it could be explained by the habituation of adolescents to anxiety-provoking situations, as has been described in armed conflict situations.Reference Cénat, Farahi, Dalexis, Darius, Bekarkhanechi and Poisson36 Participants in this study lived in areas that had been affected by EVD and COVID-19. Hence, adolescents could have become used to high anxiety levels, resulting in a decrease in their symptoms over time, as their internal alarm system would be less activated by the fear of being infected.

Exposure to EVD was not a significant predictor of symptoms of either anxiety or depression, in their respective full models. This contradicts findings from adult samples, where exposure to EVD is a significant predictor of mental distress.Reference Kaputu-Kalala-Malu, Musalu, Walker, Ntumba-Tshitenge and Ahuka-Mundeke7–Reference Cénat, Farahi, Dalexis, Darius, Bukaka and Balayulu-Makila10,Reference Cénat, Noorishad, Dalexis, Rousseau, Derivois and Kokou-Kpolou11–Reference James, Wardle, Steel and Adams15,Reference Secor, MacAuley, Stan, Kagone, Sidikiba and Sow16–Reference Cénat, McIntee, Guerrier, Derivois, Rousseau and Dalexis37 These results may reflect youth being less worried than adults by actual threats, which they may minimise, and more affected by the impact of an epidemic on their relational and social environment and on their development into young adults. The wide variability in exposure to EVD among participants may also explain this result; some participants had infected relatives, whereas others had barely heard of the virus. Furthermore, social support was negatively associated with both anxiety and depression symptoms, but it only moderated the association between stigmatisation and depression symptoms. In the present sample, EVD stigmatisation, a known predictor of mental health problems in the context of EVD in adults,Reference Cénat, Kokou-Kpolou, Mukunzi, Dalexis, Noorishad and Rousseau8–Reference Cénat, Noorishad, Dalexis, Rousseau, Derivois and Kokou-Kpolou11 was a much stronger predictor, and it was also significant across all models for both anxiety and depression symptoms. Hence, it is not so much being exposed to EVD but instead experiencing EVD-related stigmatisation that predicts anxiety and depression in adolescents. This explained the important role of stigmatisation related to EVD in inducing mental health problems among adolescents living in zones affected by EVD. In a study in Sierra Leone, children orphaned by Ebola were described as being ‘in a perfect storm’ because of stigmatisation related to EVD.Reference Denis-Ramirez, Sørensen and Skovdal18 Studies also showed that words and acts of stigmatisation associated with EVD are widespread in communities affected by EVD.Reference Cénat, Kokou-Kpolou, Mukunzi, Dalexis, Noorishad and Rousseau8 EVD-related stigmatisation is a key factor for prevention, because those experiencing symptoms are afraid to talk about them for fear of being a victim of stigma. It is important to note that social support negatively predicted both anxiety and depressive symptoms and was among one of the strongest predictors for both. Social support is one of the most important factors for protection against mental health problems, especially depression, in young people.Reference Cénat, Rousseau, Bukaka, Dalexis and Guerrier28–Reference Gariépy, Honkaniemi and Quesnel-Vallée38,Reference Quinn, Boyd, Kim, Menon, Logan-Greene and Asemota39 This result also showed that despite high levels of stigma, communities affected by EVD in Equateur Province have strong social resources that can help youth to build resilience. However, the results also showed that stigma and exposure to EVD are such strong factors that social support does not moderate their relationships with mental health problems, except for the relationship between stigmatisation and depression.

We also found that living in a rural area negatively predicted both anxiety and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents in this sample. This was contrary to what has been found in other research. Indeed, previous studies among adults in the same region found that living in rural areas was associated with different mental health problems.Reference Cénat, McIntee, Guerrier, Derivois, Rousseau and Dalexis9–Reference Cénat, Rousseau, Bukaka, Dalexis and Guerrier28 The findings of the present study could be explained by reduced access to information on EVD in rural settings, which can lead to increased EVD-related stigma.Reference Cénat, Broussard, Darius, Onesi, Auguste and El Aouame40 Indeed, a recent scoping review on EVD prevention measures showed that access to information is a major key in preventing EVD-related stigma.Reference Cénat, Broussard, Darius, Onesi, Auguste and El Aouame40 In addition, adolescents may experience EVD-related stigmatisation more frequently than adults, leading to mental health issues in this population. In particular, a recent study found that youth affected by EVD were more likely than adults to be bullied or mocked.Reference Crea, Collier, Klein, Sevalie, Molleh and Kabba41 Preventing stigma is thus vital in preventing mental health problems, as studies consistently show that it is the most important predictor of different mental health issues in the context of EVD, including anxiety, depression, PTSD and mental distress.Reference Cénat, Kokou-Kpolou, Mukunzi, Dalexis, Noorishad and Rousseau8–Reference Cénat, Farahi, Dalexis, Darius, Bukaka and Balayulu-Makila10

Strengths and limitations

This study had significant strengths and limitations. It was the first and only longitudinal study to be conducted among adolescents in the context of EVD. There have been no studies on youth in the Equateur Province, and particularly none on Ebola, mental health and adolescents. However, there remain limitations to consider. The high attrition rate was an important limitation of this study, although this was not surprising considering that a nomadic lifestyle is common in the Equateur Province. In addition, many individuals who participated in the first part of the study had returned to their village owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, and many schools were closed because of the health crisis. Hence, we expected only to retain 25% of the participants. Recruitment efforts were made to raise participation, and we reached 490 participants at T2. As the first longitudinal study on adolescents in EVD-affected regions, this was an important starting point for research on youth in this complex context. However, the lack of similar work limited our ability to compare our results, and it was difficult to position our study in a context where work is so limited. We compared our results with studies conducted among adults in the context of the Ebola outbreak and among youth in other contexts. Still, discussing our findings in the scientific context was a challenging task. This highlights the need for further research on this topic.

Implications and future research

As this was the first study of its kind, more work is needed on mental health in adolescents living in the context of EVD. We must urgently come to understand why youth in the Equateur Province in the DRC have come to experience depression in such high numbers. Future work should focus on understanding the underlying reasons for our findings. Priority should be given to the restoration of a supportive environment that may help youth overcome the developmental challenges associated with EVD outbreaks. The mental health needs of adolescents in this environment must also be addressed, and psychological services must be provided for this population. However, there are currently insufficient psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers and other mental health professionals in the DRC. Although increasing staffing must be a priority, measures need to be taken in the meantime. For example, teachers should be trained to recognise students struggling with EVD-related mental health challenges and to provide psychological first aid. Mental health commissions should be created in each health zone or district school board to refer young individuals who need more supportive care. Furthermore, interventions to reduce EVD-related stigmatisation, which is crucial in predicting depression and anxiety, should be prioritised. Such measures could include training for youth and adults, which could be offered to various institutions such as schools and religious settings. Schools could provide mandatory training to students, discuss the prevention of EVD, and help minimise and prevent stigmatisation. It is crucial for the DRC's ministry of health and international institutions that work in DRC, such as UNICEF and Doctors Without Borders, to recognise that the situation is dramatic and develop a strategic action plan. Urgent actions must be taken now to help young people who are suffering and prevent more from experiencing depression and anxiety symptoms.

In summary, this first study on the prevalence, risk and protective factors among adolescents living in areas affected by EVD shows that many experience mental health issues. It also shows that stigma is important in predicting their mental health. Finally, the study demonstrates that despite stigma, children and adolescents who benefit from the social support of their loved ones can find the necessary resources to build their resilience. Our findings highlight two immediate needs: (a) to conduct ongoing, longitudinal studies of youth in areas affected by EVD; and (2) to develop prevention and intervention programmes to strengthen the resilience of young people. Responses to the two emergencies of EVD and COVID-19 will provide the resources and nutrients needed to build resilience in these children. Such resources will also help to ensure that the future and development of these geographic areas – which are already facing major social and economic challenges – are not compromised.

Data availability

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the research assistants (investigators) and field supervisors and the coordinator, who made sacrifices to reach the most remote rural areas. We are extremely grateful to all the participants.

Author contribution

J.M.C. and S.M.M.M.F. had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: J.M.C., S.M.M.M.F., R.D.D. and C.R. Acquisition of data: J.M.C., J.B., D.D., C.R., O.B.-M. and N.L. Statistical analysis: J.M.C. and S.M.M.M.F. Interpretation of data: J.M.C., E.D., C.R., J.B. and R.D.D. Drafting of the manuscript: J.M.C., S.M.M.M.F., E.D., S.M., D.G.V., R.D.D. and W.P.D. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: C.R., R.D.D., J.B., O.B.-M., N.L., D.D. and W.P.D. Administrative, technical, or material support: W.P.D. and J.M.C. Supervision: J.M.C.

Funding

This work was supported by grant no. 108968 from the International Development Research Center in cooperation with the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.