Over the last ten years, Colombia has gone through several sociopolitical transformations that have radically changed the nation. Two events have marked the current condition of the country: the peace agreement signed in 2016 with the biggest guerrilla group, FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia), and Venezuela’s economic and political crisis, which has forced around eight hundred thousand Venezuelans to migrate to Colombia (Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores, 2018). Every day, Colombian media report on the difficulties and challenges that Venezuelan migrants have to face when crossing the frontier. Most of the episodes focus on Venezuelan abled, cis-heterosexual individuals, contributing to the invisibilization of social migrant minorities. Few newspapers or independent news agencies have followed the discrimination that Venezuelan migrants belonging to disabled, sexual, or gender minorities, for example, experience while starting a new life in Colombia or while passing through this nation to settle in other Latin American countries or in the United States.

Additionally, the current situation of disabled people in Colombia is worrisome.Footnote 1 The armed conflict has disproportionately impacted the existing disabled Colombian community (approximately seven million people). According to Correa-Montoya and Castro-Martínez (Reference Correa-Montoya and Castro-Martínez2016, 12), “although the state has recognized the disproportionate impact of violence on persons with disabilities and the risks they face—mainly through the jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court—it still needs to strengthen its institutional response and make adjustments to the policy of victims in order to adapt it to the differential approach to disabilities.” Disabled Colombians cannot “forge a life that is autonomous, independent and free of violence” (Correa-Montoya and Castro-Martínez Reference Correa-Montoya and Castro-Martínez2016, 13), despite the efforts carried out by the state through legal protections such as the National Disability and Social Inclusion Policy adopted in 2013. Furthermore, exclusionary stereotypes—some of them distributed by media—toward this community prevail at the cultural level in the country and, for example, “still justify practices such as the involuntary sterilization of persons with mental and intellectual disabilities in violation of human rights instruments” (Correa-Montoya and Castro-Martínez Reference Correa-Montoya and Castro-Martínez2016, 13). The implementation of neoliberal policies in the last two decades has also added to the difficulties of this community. The Colombian state has been putting into practice austerity measures that directly affect minority groups and has ceded the administration of public resources to private entities (Correa-Montoya and Castro-Martínez Reference Correa-Montoya and Castro-Martínez2016, 46).

In the specific case of disabled migrants in the Global South, it is important to note that they have to face challenges related to their precarious migration situation in addition to the difficulties related to their disabilities. As Pisani and Grech (Reference Pisani and Grech2015, 436) have noted, social barriers associated with poverty are “intensified throughout the forced migration process … in protracted displacement contexts where the rights and needs of disabled people are often pushed to the periphery, their voices largely unheard, their rights ignored, to crossing borders, borders marked by danger, death and human insecurity.” Colombia continuously maims the social body of the nation as well as the physical and psychological state of its citizens, as disability is produced in and through neoliberal violence associated with the Colombian armed conflict. For example, landmine victims are often forced to flee the predominantly rural areas to seek medical attention, among other services, that is typically only available in urban areas (Counter Reference Counter2018, 450).Footnote 2

To tackle the relationship between representation and disability in the Colombian neoliberal context, we study Los informantes (The informants), a magazine-format TV show produced by Caracol Television (dir. María Elvira Arango, Colombia, 2013–), which has aired some stories on the lives of disabled (migrant) Venezuelan and Colombian men. We do so by combining critical discourse analysis (Fairclough Reference Fairclough1995; Grue Reference Grue2015; Van Dijk Reference van Dijk1999; Wodak Reference Wodak, Verschueren, Östman and Blommaert2006), multimodal critical discourse analysis (Kress and Van Leeuwen Reference Kress and van Leeuwen2006), and queer linguistics (Motschenbacher and Stegu Reference Motschenbacher and Stegu2013) with disability studies (Erevelles Reference Erevelles2011; Garland-Thomson Reference Garland-Thomson1997; Mitchell and Snyder Reference Mitchell and Snyder2015) and “crip theory” (Johnson and McRuer Reference Johnson and McRuer2014; Kafer Reference Kafer2013; Puar Reference Puar2017). We chose this TV program because it is one of the most viewed during prime time on Sundays and one of the few shows that has reported on the lives of disabled people. In no way do we suggest that this TV show represents a complete depiction of disability in Colombia, nor do we imply that our analysis can be generalized beyond this specific program. We aim to study how Colombian media have constructed disability and disabled people, as this issue has not been fully explored. Addressing this gap is relevant not only in the Colombian context but also to contribute to the understanding of how disability is depicted within the Global South. Most scholarly contributions have focused on literary or artistic artifacts (e.g., novels, movies, or paintings), while print and audiovisual journalism remain underinvestigated. This research sheds light on the way language is employed in Latin American media to reify and reinforce (counter-)hegemonic ideas of the (disabled) body. By listing and analyzing several discursive strategies, this study reveals that language plays an important role in dismantling and/or sustaining ableism in the current Latin American neoliberal context.

We argue that Los informantes relies on inspirational and individualistic imagery that conceals the role of the neoliberal state in debilitating the lives of these men. By using a set of linguistic and discursive strategies (the supercrip figure, narrative prosthesis, the inclusionist model, etc.), Los informantes masks the social and political aspects of disability, adding to the dominant historical-sociocultural representations. However, it is possible to find power and resistance actions in the speech and actions of individuals featured on the show insofar as their voices cannot be and are not totally controlled by the journalist. This study seeks to contribute to the study of intersections between language, dis/ability, sexuality, and media in Latin America; to question dominant discursive constructions of disability; and to propose anti-ableist media discourses.

Methods: Multimodal critical discourse analysis, disability/crip studies, and queer linguistics

Motivated by the situation described above, we seek to answer the following questions: How are disabled men represented in Los informantes? What discursive strategies are put into practice to construct these representations? What kinds of implications do these representations produce in the current sociopolitical situation of Colombia? What alternatives do disabled men have to contest their mediatized depiction? To answer these questions and to be able to address the complexity of identities, intersections, and discursive characteristics presented in the TV program, we opted for an interdisciplinary and intersectional approach.Footnote 3 From critical discourse analysis, including multimodal analysis, we borrow the idea that the selection of certain discursive strategies is purely ideological. That is to say, the producer of the texts chooses, from a repertoire of semiotic resources, the elements that better convey their interests and intentions, while erasing or leaving other components behind (Kress and Van Leeuwen Reference Kress and van Leeuwen2006). By examining the linguistic and nonverbal elements used by the producer of the discourse, we can determine what information the discourse ignores and, most importantly, the ideological interests it conveys. As Fairclough et al. (Reference Fairclough, Graham, Lemke and Wodak2004, 1) have argued, the critical objective of critical discourse analysis is not only to analyze the roots of social problems but also to spot feasible ways of resolving them. The goal of our study is to shed light on how disability is depicted in Colombian audiovisual media and, by answering this question, present alternatives to contest dominant representations.

Linking critical discourse analysis and multimodal analysis with queer linguistics allows us to better understand how masculinity intersects with disability in Los informantes. Queer linguistics questions how normalized (sexual and gender) practices are constructed discursively and provides a poststructuralist and Foucauldian perspective on discourse. According to Motschenbacher (Reference Motschenbacher2010), discourses should be conceived as practices that form the object to which they refer. Additionally, dominant discourses “have in the course of a continual process of citation and re-citation reached a degree of materialisation that enables them to be perceived as normal or natural” (Motschenbacher Reference Motschenbacher2010, 11). Thus, our analysis reveals how Los informantes constructs the bodies of these three men as both departing from and replicating an existing ideal of normalcy.

In this same sense, disability studies and crip theory are essential tools for our analysis. These two approaches consider disability not essentially as a property of bodies. On the contrary, it is “a representation, a cultural interpretation of physical transformation or configuration, and a comparison of bodies that structures social relations and institutions” (Garland-Thomson Reference Garland-Thomson1997, 6).Footnote 4 Although this cultural definition works to highlight the impact that depiction generates over disability, our analysis also focuses on the phenomenological and historical materialistic aspects of physical and mental impairment. We conceptualize disability as entangled with a set of elements that produce clear and real impacts on the lives and bodies of disabled people. As Erevelles (Reference Erevelles2011, 6) has noted, disability should be conceived “as the central analytic, or more importantly, the ideological linchpin utilized to (re)constitute social difference along the axes of race, gender, and sexuality in dialectical relationship to the economic/social relations produced within the historical context of transnational capitalism.”

Previous contributions: The depiction of disability

There has been ample research on the cultural representation of disability, particularly in the United States and Europe (Clare Reference Clare2017; Fraser Reference Fraser2013; Garland-Thomson Reference Garland-Thomson1997, Reference Garland-Thomson2009; Gallop Reference Gallop2019; Grue Reference Grue2011, Reference Grue2015; McRuer Reference McRuer2006, Reference McRuer2018; Mitchell and Snyder Reference Mitchell and Snyder2000, Reference Mitchell and Snyder2015; Shildrick Reference Shildrick2009; Siebers Reference Siebers2010; Stamou, Alveriadou, and Soufla Reference Stamou, Alveriadou and Soufla2016).Footnote 5 To our knowledge, previous research on the representation of disability in Latin America has focused mainly on cinema and literature from Mexico, Chile, Brazil, and Argentina (Antebi Reference Antebi2009; Antebi and Jörgensen Reference Antebi and Jörgensen2016). Colombia remains marginal, and only a handful of studies have been produced (Espinosa Reference Espinosa, Antebi and Jörgensen2016; Gutiérrez-Coba et al. Reference Gutiérrez-Coba, Salgado-Cardona, García Perdomo and Guzmán-Rossini2017; Pardo Pedraza Reference Pardo Pedraza, Fanta Castro, Herrero-Olaizola and Rutter-Jensen2017; Rutter-Jensen Reference Rutter-Jensen, L’Hoeste, Irwin and Poblete2015).

Juan Manuel Espinosa (Reference Espinosa, Antebi and Jörgensen2016), from a literary perspective, focuses on the Asperger’s syndrome in One Hundred Years of Solitude, the acclaimed novel by Colombian writer Gabriel García Marquez. Espinosa reads the first page of the novel in an Asperger’s-like key, paying particular attention to “the moments when readers bear witness to the creation of an imaginative world that does not follow preestablished categories, and when the text forces readers to release those received ideas and patterns and create a new image of that ‘new’ world” (Espinosa Reference Espinosa, Antebi and Jörgensen2016, 247). Chloe Rutter-Jensen (Reference Rutter-Jensen, L’Hoeste, Irwin and Poblete2015) analyzes the tensions between sports, nation, disability, and social justice in Colombian media. Specifically, she explores how bodies are included and excluded in Colombian national mythmaking via sports. She found that disability in sports in Colombia is treated paradoxically: disabled athletes experience glory and media attention, while the nonathletic disabled body is excluded from citizenship participation (Rutter-Jensen Reference Rutter-Jensen, L’Hoeste, Irwin and Poblete2015, 176).Footnote 6

From a cultural studies approach, Diana Pardo Pedraza (Reference Pardo Pedraza, Fanta Castro, Herrero-Olaizola and Rutter-Jensen2017) studied the Remángate (Roll up your pant leg) campaign from 2014, an initiative that was part of the International Day for Mine Awareness to create awareness about land mines and their victims in Colombia. She found that the discursive production of disabled bodies in this audiovisual campaign conceals gender, class, race, and other intersections linked to the land mines and to the long-standing armed conflict in the nation. Using a content analysis approach, Gutiérrez-Coba et al. (Reference Gutiérrez-Coba, Salgado-Cardona, García Perdomo and Guzmán-Rossini2017) explore the coverage of mental health in the Colombian press, analyzing 545 journalistic notes about mental health that were published in seven Colombian newspapers from July 1, 2013, to June 31, 2014. The authors found that journalists lack knowledge about mental health, denying the reader the opportunity to learn about this type of disability beyond mere facts. Therefore, the study calls for better training on disability topics in university journalism programs in Colombia.

Overall, the findings of these studies corroborate the need for more information on disability issues and their representation by the media. There is a gap in our understanding of how disability is depicted in Colombian media and its intersections with gender, sexuality, and race. Our study is the first that follows the critical discourse analytical framework, in combination with disability studies and crip theory, to explore the representation of male disability and sexuality in Colombia and to disentangle the discursive and cultural sets of elements that produce and impact the lives and bodies of disabled people as represented in multimodal discourses. Although our study borrows theoretical concepts from other studies of the cultural representation of disability, mainly those from the United States and Europe, our exploration diverges from them as it is informed by how neoliberalism has affected the Global South in general, and how current Colombia’s political situation impacts the lives of its disabled communities in particular. Therefore, our study indirectly contributes to the decolonization of disability studies. As Meekosha (Reference Meekosha2011) and Connell (Reference Connell2011) have argued, current debates in disability studies in the Global North have mainly ignored the experiences of disabled people of the Global South despite the fact that the majority of disabled people live in the Global South.

A crip/queer discursive analysis of disability in Los informantes

Under the direction of María Elvira Arango, a well-known Colombian journalist, Los informantes has been broadcast in Colombia for more than five years and has produced more than 250 episodes, each composed of three reports approximately fifteen minutes long. Los informantes narrates “stories of incredible people, places and situations [historias de personajes, lugares y situaciones increíbles]” and its motto is “Grandes historias” (Great stories). This TV show has received several awards and can be seen in the United States or other countries through Caracol International through subscription-based services. We studied three reports that follow the lives of three cisgender disabled men: Alca, a physically disabled Venezuelan migrant (“ALCA un completo incompleto” [ALCA an incomplete whole] in episode 241); Sergio, a young Colombian with Down syndrome (“La vida a MI manera” [Life MY way] in episode 241); and Diego, a physically disabled Colombian lawyer living in Great Britain (“Su distinguida señoría” [His distinguished lordship] in episode 243) (figures 1, 2, and 3). Given space limitations for this article, we mainly use examples of the first report to illustrate the discursive strategies analyzed in the corpus.

Figure 1. Introductory image to Alca’s episode (Los informantes, episode 241, 2018).

Figure 2. Introductory image to Sergio’s episode (Los informantes, episode 241, 2018).

Figure 3. Introductory image to Diego’s episode (Los informantes, episode 243, 2018).

“ALCA un completo incompleto” tells the story of a twenty-five-year-old Venezuelan diagnosed with congenital femoral agenesis, a medical condition that affects the development of the femur, ranging from minor shortening to its total absence, as in Alca’s case. He migrated to Colombia with his pregnant wife and relocated to Barranquilla, one of the biggest cities in this nation. Alca’s life has received a lot of attention in several media outlets, and he has become a motivational speaker.

The second report, “La vida a MI manera,” portrays the life of Sergio and his battle against interdiction—a state law that can serve to declare a mentally disabled person legally incompetent when considered necessary and appropriate for their well-being. Sergio, after being interdicted by his mother, demands his rights to decide, to work, and to marry. In the report, Sergio is portrayed as a warrior who “is here to take over the world regardless of his disability [sale a comerse el mundo sin importar su discapaciadad].” In contrast, “Su distinguida señoría” tells the story of Diego Soto Miranda, a lawyer diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy since childhood. The lack of resources in Colombia to treat Diego’s condition led his family to move to England to obtain better medical care. He later became a well-recognized lawyer in the UK. In the story, Diego is portrayed as someone trapped in a motionless body but whose brilliant mind provided him with a successful career: “Barely able to move a single finger, he became the first and only Latin American to be part of the old Order of Barristers.” (Sin apenas poder mover un solo dedo, consiguió ser el primer y único latinoamericano en formar parte de la antigua orden de los barrister.)Footnote 7

In the Los informantes report on Alca’s story, compared with other news media, we note an erasure of the struggles he and his wife had to endure when migrating. Additionally, this TV program does not make any reference to the several social forces involved in his displacement: the Venezuelan government and the still-existing Colombian armed groups. In news outlets such as AFP (Agence France-Presse) and Perfil (Argentina based), Alca names these two political actors and how they intervened in his decision to move to Colombia. We will turn most of our attention to this concealment and to the discursive strategies used in Los informantes to construct Alca’s subjectivity.

The narratives that media implement do not only create a descriptive view of how disabled people live. These discourses also produce a normative effect insofar as many disabled people must accept tropes such as the “tragic victim” or the “resilient hero” to secure media attention (Grue Reference Grue2015). In other words, an amalgamation of symbolic constructs and social practices exists. This phenomenon is particularly evident in Los informantes’ report on Alca. This disabled man is constructed through a familiar allegorical figure of disability, the “supercrip.” This tag, which has been widely studied (Hardin and Hardin Reference Hardin and Hardin2004; Harnett Reference Harnett2000; Norden Reference Norden1994; Schalk Reference Schalk2016), is “usually given to people who are clearly—visibly—disabled, but who nevertheless achieve something remarkable and impressive (particularly something that requires physical exertion)” (Grue Reference Grue2015,110).Footnote 8 Supercrips do not rely on technological development, they “may simply be people with impairments who display superhuman willpower and fortitude” (Grue Reference Grue2015, 110). This discursive strategy generates a complex situation vis-à-vis disability representation as impairment is constructed positively. Any criticism of this figure may end up being interpreted as cruel and unsympathetic. Therefore, it is necessary to intersect it with the “coercive ideologies of compensation and achievement” (Grue Reference Grue2015, 110) and with the erasure of the social factors that affect disability.

The supercrip trope appears in Alca’s story from the beginning of the episode. Los informantes frames the depiction of this disabled man within the current abortion debate. Alca’s strength and powerful willingness are bound up with this current subject. After addressing the different perspectives one can take on this polemical issue and explaining that Alca’s impairment was produced by several abortion attempts, the journalist states: “He knows what it is to live by overcoming obstacles. Without complaints, he makes the best out of having been an unwanted child, even the pain.” (Él sí que sabe lo que es vivir saltando obstáculos. Sin quejas, saca lo mejor hasta del dolor de haber sido un niño no deseado.) An ideology of achievement can be easily grasped in the construction of these sentences. For example, the use of the affirmative adverb sí does not simply mark a strong emphasis but, most important, it implies that we, the presumably able-bodied viewers, should reconsider our ideas of what an obstacle is and the better way to address it. Simply put, Alca is constructed as a resilient hero with a moral message. This discursive phenomenon is emphasized by the use of expressions such as “sin quejas,” “hasta del dolor,” and most clearly in “Alfonzo Mendoza [Alca] was stronger than the rejection and lack of love from his own mother … since he was in her womb; he opposed his mum.” (Alfonzo Mendoza fue más fuerte que el rechazo y el desamor de su propia madre … desde el vientre le llevó la contraria a su mama.) However, one must question the erasure of the reasons why Alca’s mother tried to abort him. There is no further explanation of the vulnerability, precarity, or violence that she may have had to face at the time of pregnancy and abortion. A sociocultural approach to this decision does not materialize in the whole report. Because this information is elided, the audience is denied the opportunity to know about Alca’s family and its past. Abortion and the origin of the disability here are decontextualized so that they can be used as a discursive tool to craft the supercrip figure.

One of the strategies that add to the suppression of the social aspects of disability and to the construction of Alca as a supercrip figure is the constant employment of sentences in which abstract and concrete nouns such as “obstacles” are personified or animated. For example, “[Alca] spends his time overcoming obstacles that cross his path [se la pasa saltando obstáculos que se le cruzan en el camino].” This type of sentence masks the sociopolitical and economical elements that continue debilitating these subjectivities. The obstacles that Alca overcomes daily have been socially constructed. Disability, as in Alca’s case, should not be reduced to a fixed state that has to be accommodated. Quite the contrary, it “exists in relation to assemblages of capacity and debility, modulated across historical time, geopolitical space, institutional mandates, and discursive regimes” (Puar Reference Puar2017, xiv). These components, however, are not depicted in Los informantes, leading the viewers to forget that the current neoliberal state and other institutions (e.g., media) contribute daily to both the precarization and commodification of a significant number of (disabled) bodies.

As Jasbir Puar (Reference Puar2017, 35) has noted, the current situation of disability and racialized gender nonconforming identities in local places under global neoliberalism is characterized by two interconnected principles: on the one hand, the politics of debilitation, that is, the bodily injury and social exclusion brought on by economic and political factors, and, on the other hand, the commodification of minorities. In the case of Alca’s episode, the process of making his body visible serves the supercrip trope while erasing social and political constraints that disabled Colombians face daily. Los informantes does not refer to the many ways in which the Colombian state has debilitated many of its citizens by denying access to health services, for example. Coleman (Reference Coleman2007), following Santos (Reference Santos2002, 208), notes that the majority of citizens in neoliberal Colombia live in a precarious state characterized by different forms of exclusion. Colombians’ rights have been commodified or denied by the implementation of common neoliberal strategies such as the privatization of services, the flexibilization of labor through contractualization, and the reductions of social investment programs with the support of the World Bank and other international funders. In other words, neoliberal structures in the country have created an “uncivil civil society” (Santos Reference Santos2002, 451–452). Although an important number of laws that aim to protect citizens’ rights exist, Colombians live in permanent anxiety about their future, as in reality those rights are undermined, debilitating the nation’s (disabled) communities at large.

If Alca’s body and life are there to be seen and admired without any connection to social aspects, it is because one can extract some value from this representation. The politics of sympathy, which converts injury “into cultural capital not only through rhetorics of blame, guilt, and suffering but also through those of triumph, transgression, and success” (Jain Reference Jain2006, 24), is the mechanism used by Los informantes to achieve this. The worth given to Alca’s story relies not only on a spectacularizing strategy, which has been constantly used by media outlets. It depends, most importantly, on the moral message it delivers. This can be corroborated by utterances like “Alca is a great person and has no limitations. The limits are yours. And know that he is the one who says so.” (Alca es un grande y no hay limitaciones. Los límites los pones tú. Y qué lo diga él.) In this passage, which ends the episode, one can find the ideological message of Los informantes. The (mainly Colombian) viewers should discard any sociological explanations of the difficulties disabled individuals may confront in life. Moreover, the complex and precarious situation in which most of them live in this nation, as we described before, does not require any state intervention, since solid willpower will suffice.Footnote 9

This individualization and decontextualization of the struggles (disabled) individuals undergo can also be interpreted as a clear example of the entrepreneurial narrative that regulates current neoliberal societies (Aizura Reference Aizura2018; Fritsch Reference Fritsch2013; Irving Reference Irving and Enke2012). Alca’s life is worth showing since it is not a burden to his new nation; his body is economically productive despite his impairment. The scenes that show Alca earning an income for his family through rapping are one of the main aspects of the episode. This discursive strategy normalizes Alca’s subjectivity, on the one hand, and on the other, contributes to maintaining heteronormative neoliberal ways of living. As noted by Mitchell and Snyder (Reference Mitchell and Snyder2015, 35), to respect the demands of neoliberalism, disability must make itself “knowable within the parameters of heteronormativity (i.e. to see disability as less differentiated from other conditions of embodiment and, therefore, within the range of the ‘normal’ rather than deviant).” In Los informantes, Alca’s masculinity is constructed through the traditional figure of the breadwinner, and a segment of the episode is dedicated to answering the question: “How does one flirt with a girl?” (¿Uno cómo coqueta con una chica?) Additionally, fatherhood is constructed as a feat intersecting sexuality and disability: “The boldest of all [adventures] is his brand-new role as a father.” (La más audaz de todas las es su recién estrenado rol de papá.) This normalization of disabled people’s sexuality also emerges in the other two reports, where the fact that a young Colombian with Down syndrome longs to get married is highlighted.

In “La vida a mi manera” and “Su distinguida señoría,” the entrepreneurial discourse also constitutes a central part of the reports. Both Sergio and Diego are portrayed, in Wendy Brown’s terms (Reference Brown2003), as individuals whose actions are imagined in terms of their capacity for entrepreneurial gain. Sergio’s disability did not prevent him from becoming a respected lawyer. Diego is described as someone who has achieved social recognition by being a good worker, son, and respected member of society. Their desires for upward mobility and self-determination are presented as a force that confers on them recognition, rights, tolerance, and acceptance. This neoliberal model of describing disabled individuals, as we have noted, hides the intersections between disability and exploitative economic structures of the capitalist society in contemporary Colombia. Many disabled individuals in this nation do not have access to work or are underemployed, allowing the (able-bodied) capitalist class to accumulate wealth.

Another excerpt illustrates perfectly a common trope employed when representing disability, the narrative prosthesis: “Alca is a great person and has no limitations. The limits are yours. And know that he is the one who says so.” (Alca es un grande y no hay limitaciones. Los límites los pones tú. Y qué lo diga él.) Several scholars (Mitchell and Snyder Reference Mitchell and Snyder2000; Puar Reference Puar2017) have shown how literature and film constantly employ tragedy and lack to reconsolidate the able body. To be exact, “the body that no longer functions properly, whether physically, emotionally, or sexually, drives narrativization through a cause-and-effect relation to rehabilitation and resolution, highlighting the normativity of able bodies and leading to the climax of the story” (Puar Reference Puar2017, 85).Footnote 10 Since the disabled bodies represented in Los informantes cannot be physically rehabilitated, the resolution happens in terms of a lecture. “Los límites los pones tú” not only negates the social factors that debilitate disabled people but also reaffirms the able body by obscuring physical dis/ability. Because limits can be overcome via a positive attitude, there’s no need to tackle how bodies are affected by economic and health policies and environmental arrangements. This would explain why important issues for the disabled community such as accessibility and accommodation are not addressed in this TV program. The same strategy is found in Diego’s case. The journalist addresses his mobility issues but not in relation to how accessibility is limited. On the contrary, the journalist sees these environmental and architectural arrangements as barriers that Diego has torn down. The discussions on who built those barriers are, once again, elided from the narrative.Footnote 11

As for the visual elements of the episodes, one could argue that they, too, reinforce this ideological representation of disability. The camera primarily alternates between two techniques to characterize Alca: the talking head method and observational shots. The former is employed when Alca is being interviewed by the reporter (figure 4). Although it may be interpreted as a technique that allows the subaltern to speak, paraphrasing Spivak, Alca’s voice is controlled by the questions of the journalist. These interrogations aim to understand this “strange” body, as in “What clothes do you wear on the bottom?” (¿Qué ropa usas abajo?), where a daily activity needs to be thoroughly explained by Alca. This type of question is quite common in the report and work along with the normalization of Alca’s life. It is relevant not to forget that “the able body cannot solidify its own abilities in the absence of its binary Other” (Snyder and Mitchell Reference Snyder and Mitchell2001, 368). The depiction of Alca’s body as something atypical restates ableness. It seems that we need a voyeuristic construction of this corporality to come to the understanding and consolidation of our own (able) bodies. As Garland-Thomson argues (Reference Garland-Thomson1997, 41), “the disabled figure in cultural discourse assures the rest of the citizenry of who they are not while arousing their suspicions about who they could become.”

Figure 4. Talking head shot. The reporter interviews Alca (Los informantes, episode 241, 2018).

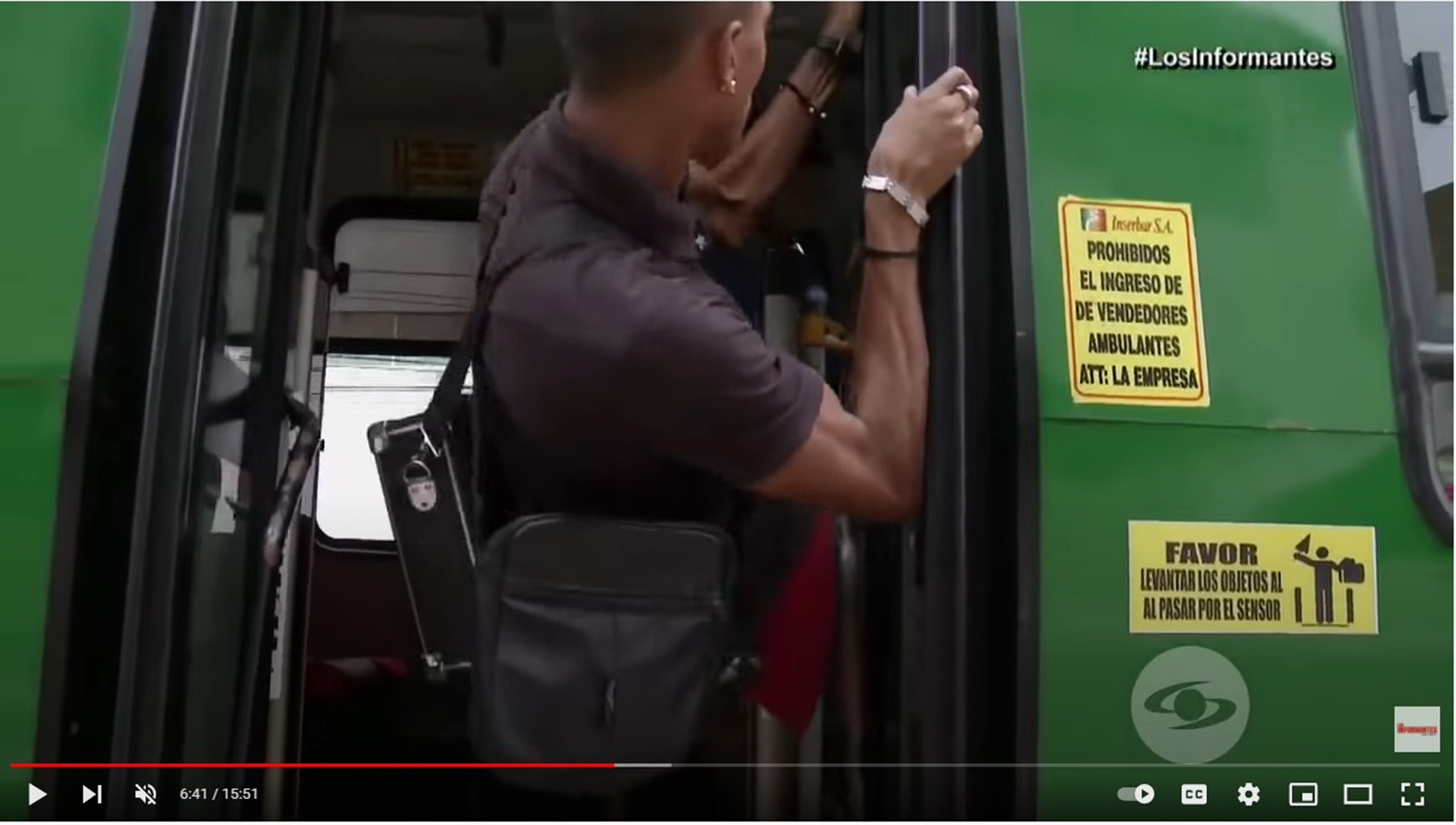

The observational shots primarily consist of takes of the subject, Alca in this case, carrying out some activities. Alca becomes an offer image (Kress and Van Leeuwen Reference Kress and van Leeuwen2006) in that he does not turn his gaze to the viewers. Quite the contrary, we inspect his life and how he copes, for example, with mobility. Alca uses a skateboard to commute and as his favorite sport (see figure 5). This fact is underscored visually by several observational shots and by statements like “as it is his means of transport [a skateboard], almost an extension of himself, he has become an expert who flies between ramps and skating rinks.” (Como es su medio de transporte, casi una extensión de sí mismo, se ha vuelto un experto que vuela entre rampas y pistas de patinaje.) This personalization of mobility via a concentration on the feeling of freedom and grandiosity occupies all the narrative time, leaving no room for the discussion of ableist assumptions toward access. A scene in which he climbs through the door of a bus to access it and to work rapping on the bus suitably portrays this aspect as well as the concealment of the social factors of disability. While Alca gets into the bus, the reporter affirms: “And he would like to pursue extreme sports or give lectures about his life, but while other doors open, he sneaks into one of the urban buses in the busy streets of Barranquilla.” (Y quisiera dedicarse a los deportes extremos o a dar conferencias sobre su vida, pero mientras se abren otras puertas, se cuela en la de los buses urbanos en las agitadas calles de Barranquilla.) This linguistic choice is particularly important. On one hand, the use of the hypothetical subjunctive (quisiera) creates a sense of impossibility. Alca’s desire to “improve” his life is dismissed by this verbal mode. Furthermore, the social aspects are not directly mentioned. They are constructed metaphorically and via impersonalization (“se abren otras puertas”). If we extrapolate Kress and Van Leeuwen’s (Reference Kress and van Leeuwen2006) theory of reading images to this case, we could claim that the “real” is mainly presented by the nonverbal element, Alca entering the bus, and reinforced verbally (“se cuela en los buses urbanos”). The “real,” or status quo, will not change and does not need to since any possibility of modification is constructed hypothetically. Alca has the physical strength and willpower to adjust to the dominant society despite his disability. As Kress and Van Leeuwen (Reference Kress and van Leeuwen2006) have noted, gaze demands that the audience enters in an imaginary relationship with the represented participants or actors. The spectators of Alca, Sergio, and Diego fail to scrutinize their responsibility, positionality, and implications in disability. The journalists mediate the viewers’ sympathy for these participants while also reproducing an “ethnographic gaze” that marks the disabled body as socially different.Footnote 12

Figure 5. Observational shot. Alca commuting in Barranquilla (Los informantes, episode 241, 2018).

Gaze also depends on the meanings communicated by other modes. In the reports, there is always a voice-over that guides or frames the two visual techniques explained above. The viewer must interpret the scenes by means of what the narrator declares. As a result, any scene is resignified to both maintain the idea of Alca (as well as Diego and Sergio) as a supercrip and to avoid any reference to the way social factors intersect with disability. An instance of this phenomenon is the shots of Alca heading to work (figure 6). His commute turns into a moral lecture, not because of the physical effort this activity may require, as we see in the scene, but mainly because of what the reporter states: “Not only are his legs missing, he lives in scarcity, he does not have a stable job and he needs every peso he earns, but the trick is that he never thinks about his limitations.” (No solo le faltan las piernas, vive en la escasez, no tiene trabajo estable y necesita cada peso que se gana, pero el truco está en que no piensa jamás en sus limitaciones.) Nowhere is the individualization of disability more evident than in the previous excerpt. Limitations do not have a social factor attached to them. Despite the difficult conditions he and his family live under, a positive attitude suffices to cope with them.

Figure 6. Alca getting on the bus to work (Los informantes, episode 241, 2018).

Sara Ahmed (Reference Ahmed2006, 3) has described orientation as to how we inhabit space, how we apprehend this world, and to whom or what we are allowed to direct our energy and attention. This critic has also noted that whiteness is a social and physical orientation that eases passage through the world for individuals who are white. These bodies “inhabit the world as if it were home, then these bodies take up more space. Such physical mobility becomes the grounds for social mobility” (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2006, 136; emphasis added). Ahmed’s theorization of whiteness and mobility could also be expanded to ability. The able body also inhabits the world as if it were home. Los informantes presents mobility as something given, natural, not part of a privilege that only certain individuals can enjoy. In the report, Alca’s disability is portrayed as the limitation that restrains him from free mobility. The way race and ability constrain his mobility is not mentioned. Race is particularly important since it intersects with ability and migration. Ahmed’s use of motility, as the ability of an organism/body to move independently, alerts us that mobility in many cases depends on the immobility of others.

The supercrip trope posits mobility as an ability that every individual possesses or can possess, not associated with race, gender, and other intersections. By disconnecting mobility from privilege, Los informantes presents it as mere geographical traveling. In “Su distinguida señoría,” for example, Diego uses a wheelchair and depends on his mother and his assistant to carry out everyday activities. The narrator states that “his assistant, or better said, his shadow sticks to him the rest of the day and takes him to the office in the heart of London.” (Su asistente o mejor dicho, su sombra se le pega el resto del día y lo lleva a la oficina en el corazón de Londres.) There is no mention of the cost involved in having an assistant, or how Diego gained access to a wheelchair that satisfies his needs. Many disabled Colombians have limited mobility due to the negligence of the state to provide them with wheelchairs and other medical supplies. Los informantes loses the opportunity to discuss disability in a broader sense and in relation to who has access to citizenship. Portraying disability and, by extension, mobility as something that can be respectively overcome and achieved serves to promote an entrepreneurial discourse of the disabled body.

Mobility is particularly important in Alca’s case as he is a migrant. This migratory status in intersection with mobility, as represented in the show, plays into broader stereotypes of migrant status as otherness. It exists a fascination with strangeness as to how and where the disabled body circulates. In this sense, as Ahmed (Reference Ahmed2000, 33) has stated, “movement becomes a form of subject constitution: where ‘one’ goes or does not go determine what one ‘is’, or where one is seen to be, determines what one is seen to be” (emphasis in the original). Although Alca is depicted as a stranger due to his physical condition, the fact that he circulates in different spaces in Barranquilla to accomplish social norms (earn income for his family, for example) makes him a commodified stranger; one that contributes to neoliberal determinations of productivity while also being perceived as a strange body to look at.

The semiotic and linguistic elections made for depicting disabled men in Los informantes are political inasmuch as they valorize certain aspects of social reality while implicitly hiding others. One may question why “crip time” is not represented in this TV show. This important concept, developed by disability communities and critical disability theory, refers not only to “a slower speed of movement but also about ableist barriers over which one has little to no control” (Kafer Reference Kafer2013, 26); most importantly, “crip time involves an awareness that disabled people might need more time to accomplish something or to arrive somewhere” (Kafer Reference Kafer2013, 26).Footnote 13 Los informantes invests no time in representing Alca’s temporal needs. As mentioned earlier, the supercrip narrative ends up normalizing Alca to the extent that the extra time he spends, for example, commuting or accessing public transport is not discussed. All this is politically relevant in Colombia, where being disabled entails racialized socioeconomic structures of inequality, long-standing discriminatory practices, and lack of access to health care and resources (El Espectador 2014). Moreover, these factors are intertwined with a global neoliberal logic (Antebi and Jörgensen Reference Antebi and Jörgensen2016; Erevelles Reference Erevelles2011). Ignoring them, through a normalized representation, ratifies the oppression and marginalization of disabled people in general.

In Diego’s and Sergio’s cases, crip time is also omitted. The audience perceives Diego as a resilient individual who became an important lawyer thanks to his remarkable intellectual abilities and his strength to overcome obstacles. However, the extra time needed to access education and use of facilities at tertiary educational institutions, among other additional needs, are not discussed. As for Sergio, there is no mention of how much time it took him to find an educational institution, to find a job, to navigate bureaucracy as mentally disabled, or to start having loving relationships. This is important to highlight since institutions and sociability, in general, have mainly been conceived by able-bodied norms.

Crip time refers not only to the additional time needed by people with disabilities to carry out their daily activities but also to a temporality imposed by neoliberalism. Our societies, informed by ableism and capitalism, conceive disabled time as slow and unproductive. Disabled, fat, elderly, and gendered subjectivities are conceived as a “waste” of time for not performing within normative parameters (of productivity and cis-heterosexuality). Thus, crip time could be a sort of criticism of disabled people who fail to respect ableist temporality (Baril Reference Baril2016, 159). However, in Los informantes, the potentiality of crip time is not allowed to appear. Alca, for instance, is constructed as adhering to the ableist productive temporality through the politics of respectability. That is to say, he is the sole individual to assume responsibility for behavioral self-regulation and self-improvement within moral, education, and economic regulations imposed by neoliberalism. In Los informantes, individuals who use crip time to contest normativity and the entrepreneurial trope are not deemed worthy of representation. In addition, the temporality of the television program itself—the use of segments and transitions—does not allow for much flexibility in modes of temporality. As each story can only last between fifteen to twenty minutes, Los informantes prefers to focus on tropes such as the supercrip figure rather than portraying disabled men as complex individuals.

Furthermore, the iconography and the rhetorical strategies used to portray the young Colombian with Down syndrome and the physically disabled Colombian lawyer living in Great Britain do not significantly differ from the ones studied in Alca’s case. The main change falls in the simplistic understanding of how the dominant ableist Colombian society limits the lives of disabled men. The episode in which the man with Down syndrome is the main protagonist centers on how parents of mentally disabled people can legally make decisions for their children by appealing to the legal concept of interdiction. Although the report aims to depict the effects of interdiction and how the disabled community has contested it, it endorses normative ways of living and does not question the ableist and capitalist society at large. The protagonist, Sergio, is constructed as a productive citizen who works and longs to form a heterosexual family. Since he replicates the normative idea of a good neoliberal individual, he should not be excluded from participating in the (job market) society. In other words, Los informantes employs an inclusionist profitability narrative in which “the subjects of recognition (formerly abandoned social identities) [are] called to present difference (their alternative modes of living) in a form that feels like difference but does not permit any real difference to confront a normative world” (Povinelli Reference Povinelli2011, 450–451). Sergio’s and the lawyers’ representations, consequently, are based on anticipation of his capacity to approximate, as much as possible, the neoliberal able-bodied and heteronormative social practices.

Although Los informantes produces an inspirational and normalized depiction of disabled men, we can find resistance embedded within it. This resistance can be found in the voices and opinions of these men, particularly in the responses Alca offers during his episode. Nowhere is this contestation of the dominant representation more palpable than when he affirms, “What I [Alca] see down there, you don’t see up here.” (Lo que yo veo allí abajo, tú no lo ves acá arriba.) This statement is given while he is seated at the same height as the journalist. The use of the adverbs of place (allí abajo, acá arriba) signals a particular perspective. Alca’s disability allows him to perceive and conceptualize the world differently. As Susan Wendell (Reference Wendell1996, 69) suggests,

it becomes obvious that people with disabilities have experiences, by virtue of their disabilities, which non-disabled people do not have, and which are [or can be] sources of knowledge that are not directly accessible to non-disabled people. Some of this knowledge, for example, how to live with a suffering body, would be of enormous practical help to most people…. Much of it would enrich and expand our culture, and some of it has the potential to change our thinking and our ways of life profoundly.

In this short but powerful statement resides a “cripistemology,” following Johnson and McRuer (Reference Johnson and McRuer2014), that can question the hegemonic discursive construction of disability in Colombian media. Thinking about disability from a critical, social, embodied, and personal position may lead us to challenge the normalized and ableist society we live in. Therefore, we need mainstream media to open a space for disabled people to construct their own representations and, at the same time, to turn our attention to media already produced by disabled individuals. Disabled YouTubers and filmmakers, for example, are constantly sharing embodied knowledge and experiences that may challenge more dominant representations. An analysis of these media productions needs to go hand in hand with an examination of the ways neoliberalism forecloses contestatory options while, at the same time, it includes marginal voices that can be commodified.

Concluding remarks

By analyzing Los informantes, a Colombian TV magazine format show produced by Caracol Television, the present study contributes to understanding the current representation of male disability in Colombian audiovisual media. Our objective was to explore how disability is depicted in Colombian media and how it intersects with gender, sexuality, and race. We found that the TV show relies on inspirational and individualistic imagery that suppresses the role of the state in debilitating the lives of disabled men. Los informantes is built on a set of linguistic, visual, and discursive strategies that serve to mask the social and political facets of disability. This representation of male disability contributes to the establishment of a dominant discourse of male disability in neoliberal Colombia. However, we also observed that it is possible to find power and resistance in the speech and actions of social actors represented in the reports since their voices cannot be and are not totally coerced by the journalists and the narrator.

One main implication of this study relates to social inequalities and discourses of acceptance, tolerance, assimilation, heteronormativity, and neoliberalism in relation to disabled minorities. The reports explored in the present work negatively depict disability, perpetuating the social hierarchies present in mainstream Colombian media. This hierarchization has been noted in studies about the representation of gender nonconforming individuals as well as members of the gay and lesbian communities (García León and García León Reference García León and García León2017; García León Reference García León2021; García León Reference García León2018; Rivera Reference Rivera2013). The present study, in dialogue with other research, proves that Colombian media place the male, cis-sexual, white, able body in the highest position of the media hierarchy. Therefore, there is a need for more representations of Colombian disability produced by disabled individuals. We cannot forget that the people most affected by oppression in most cases do not have the means to produce representations of their own lives. This situation has led people from outside the group, in this case nondisabled individuals, to document the lives of a group to which they do not belong. Discourses produced by disabled individuals in intersection with race, gender, and class will offer other ways of understanding this corporality and will also serve as tools to deconstruct the social hierarchy produced by mainstream media. However, representations by disabled individuals will only solve the problem if accompanied by a more thorough rearrangement of discourses and socioeconomic systems.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andre Blackburn for the style corrections of the manuscript and Anastasia Ramjag for the Spanish to English translations. We also thank Kent Brintnall, Susan Antebi, and the two evaluators for their valuable comments.