1. The ambiguity of colonial international law

Many societies in the global north are currently revisiting their colonial past in a cluster of debates affecting colonial artefacts, colonial violence, memory culture, but also international economic and political relations generally. This includes questions of reparations for atrocities and of restituting looted objects.Footnote 1 One driving force behind these efforts may be the desire to regain soft power and credibility in light of the massive crises and geopolitical shifts that mark the end of centuries of dominance by the global north.

However, the recovery from colonial amnesia often turns out to be half-hearted. While many in the global north today acknowledge the immoral character of colonialism, they are comparatively less prepared to make concessions in the field of law. There is a widespread assumption that ‘it was all legal’. This argument in essence rests on the doctrine of intertemporality, which commands us to measure past events by the legal standards of the past.Footnote 2 Those standards, the argument proceeds, may look shameful from today’s perspective, but one certainly cannot change the past. The only possible remedy seems to consist in superimposing contemporary morality over past law.

The German position with respect to the 1904–1908 Namibian genocide is a case in point.Footnote 3 While the government acknowledges the country’s moral responsibility,Footnote 4 its legal position has remained unperturbed by this admission.Footnote 5 Interestingly, scholarly voices from Germany mostly come in support of the government’s position.Footnote 6 The difference between domestic and foreign perspectives on this issue is notable.Footnote 7 This position also set the terms for negotiations between Germany and Namibia aimed at coming to terms with the past pending from 2015 to 2021. They resulted in a Joint Declaration, under which Germany committed to pay €1.1 billion over the next 30 years.Footnote 8 However, the German government sees these funds as a special kind of development aid intended to benefit the affected communities in particular.Footnote 9 It denies any legal obligation to pay reparations, as this would require an illegal act.

This approach, which I shall call the conventional approach, crucially rests on the assumption that we can actually reconstruct with some certainty the specific meaning of colonial international law,Footnote 10 or at least of a ‘prevalent opinion’ within colonial international legal discourse. The conventional approach has been the target of different strands of critical legal scholarship for some time now. For example, critical legal scholarship has stressed the significance of colonialism in the evolution of international law generallyFootnote 11 and exposed the instrumental character of colonial international law as well as its racist and capitalist underpinnings.Footnote 12 In this account, colonial international law, particularly during the ‘long’ nineteenth century, stood entirely in the service of European imperialism. It enabled outrageous acts and concealed them by wrapping them in the pretense of legality. While such critical legal scholarship focuses on power instead of legality, it often tends to confirm the result of the conventional view, even though for emancipatory ends.

While the analytical work of such accounts is insightful, I believe it is also incomplete. I will argue in this article that colonial international law is overall highly ambiguous and hardly gives rise to the degree of certainty claimed by the conventional approach or its critical nemesis. Colonial international law was more than just an instrument of racist, capitalist conquest. It was above all a form of bricolage.Footnote 13 As I will show, different people implied different things in different contexts and had different purposes in mind when formulating their claims about colonial international law. One can break down the resulting ambiguity into internal and external dimensions, as I will further elaborate in Section 2.

Internally, colonial international law is ambiguous because it reflects the identity crisis caused by imperialism in Europe. Its violence threatened the self-image of Europe as a rationally ordered, civilized community. International law had to bridge this gap by ensuring peace at home while at the same time legitimizing colonial violence. An impossible task leading to many tensions and contradictions. The heterogeneity of interests involved in colonial conquest made the situation worse. Neither the colonizers, nor the colonized, formed homogeneous groups, and the formation and application of colonial international law had to navigate these rapids. I seek to uncover the resulting ambiguity by means of what I call a post-colonial approach.

Externally, colonial international law is fraught with ambiguity because it was part of a struggle for jurisdiction. No universally accepted meta-rule entitled European powers to set the terms of international law. Colonial powers simply claimed that their international law governed relations between them and the colonized peoples. Contradicting this claim, recent research has revealed how encounters involving non-Europeans are characterized by clashing claims of jurisdiction, competing visions of protection, and heterogeneous treaty-making practices.Footnote 14 It is therefore time to move beyond a Eurocentric idea of international law and tap on a wider range of sources of inter-polity law, which call into question the European monopoly over international law.Footnote 15 I seek to do so by what I call a pluralistic approach to colonial international law that taps on sources of formerly colonized societies.

Sections 3 and 4 apply the post-colonial and pluralistic approaches to the analysis of territorial claims and of the legal limits to genocide and inhuman treatment in present-day Namibia under German rule. Against the conventional view, I want to carve out the ambiguity of colonial international law, both in respect of its internal contradictions and external contestations. Regarding the latter, I will reconstruct competing ideas of inter-polity law from the letters of two traditional leaders from nineteenth century Southwest Africa: Hendrik Witbooi and Samuel Maharero. Their claims about territorial relations and the laws of war call into question the applicability and content of colonial international law.

In conclusion (Section 5), the ambiguity of colonial international law compels us to abandon the conventional view that ‘it was all legal’. Not only is the historical record more complex. The conventional view also instills a sense of self-righteousness as it vindicates the European viewpoint in every respect: For the past, colonial international law determines what was right and wrong; today, Europeans are reformed, believing their moral catharsis entitles them to impose their terms of dealing with the past. Either way, it's always according to their terms. This entrenches rather than defeats amnesia. Overcoming amnesia, therefore, requires shattering the self-confidence and homogeneity of the conventional view by emphasizing the ambiguity of the legal situation.Footnote 16 While ambiguity as such does not give rise to compensation claims, other options come to mind, such as a duty to negotiate, shifts in the burden of proof – or a profound recalibration of international law towards greater solidarity.

2. Three approaches to colonial international law

2.1 The conventional approach

As indicated above, the conventional view holds that the genocide of the Herero and Nama did not violate the rules of international law in force at the time of the events.Footnote 17 At the heart of the conventional view is the reconstruction of what it supposes to be the ‘prevalent opinion’ in colonial international law.Footnote 18 While recognizing conflicting views within colonial-era doctrine and practice, suggesting that there is a ‘prevalent opinion’ implies that these issues are ultimately resolvable and that one can determine the content of colonial international law with some certainty based on a recognized set of subjects and sources of international law. This view gets combined with an approach to intertemporal law that emphasizes the static nature of the law, rather than its dynamic side.Footnote 19 Accordingly, Germany’s occupation of Southwest Africa was legal and the genocide did not violate rules of colonial international law. The moral outrage these atrocities evoke is irrelevant from the perspective of colonial international law.

However, the criteria for determining the ‘prevalent opinion’ are all but clear. Frequently, the ‘prevalent opinion’ seems to equal the opinions of the majority of colonial-era scholars who, unsurprisingly, favoured the positions of their respective governments.Footnote 20 This boils down to a method of ‘might makes right’. That, however, would be at odds with the self-description of the ‘prevalent opinion’ in the late nineteenth century, for which the preferable view was the most consistent one, not the one backed up by the strongest military or economic power.Footnote 21 The views of the most eminent colonial-era scholars may at best establish a presumption for the existence of a certain rule.Footnote 22 Of course, one can widely disagree about consistency. There is no objective standard for measuring it as it crucially depends on one’s perspective. Nevertheless, as the following sections will elaborate, the conventional view is usually more occupied with demonstrating that the position of the most eminent authors is not entirely inconsistent rather than the most consistent one. The establishment of a ‘prevalent opinion’ therefore often rests on weak foundations. Tensions between positivist and natural law approaches in the late nineteenth century, to which I will revert later, further compound the matter.Footnote 23

2.2 Post-colonial approaches

This is the point of departure of the second approach, which undertakes a reconstruction of colonial international law from the perspective of post-colonial theory. This approach does not intend to replace past judgements with present ones in a dubious act of anachronism.Footnote 24 Rather, it problematizes the reconstruction of colonial international law as a process fraught by ambiguity. In the literature, one can distinguish three different, yet related perspectives on colonial international law’s ambiguity. The third perspective probably deserves most being labelled as a post-colonial one. I shall explain them in turn.

The first perspective is rooted in international legal doctrine. It claims that colonial international law’s ambiguity derives from its dynamic character. Accordingly, international law has always hinged between stasis and progressive development, and any reconstruction of past law needs to make choices whether it puts the emphasis on the static or on the progressive signals in international law at the time. Consequently, the International Court of Justice followed not for the first time an evolutionary approach when holding that the United Kingdom did not acquire sovereignty over the Chagos Islands in 1965,Footnote 25 as this would have violated emerging principles of international law consolidated only five years later in the Friendly Relations Declaration.Footnote 26 Similarly, it is possible to conclude that by committing genocide between 1904 and 1907, the German government did violate emerging basic rules of humanity widely accepted in the public sphere at the time that would soon crystallize into proper rules of international law.Footnote 27

The second perspective considers ambiguity as an instrumentality of colonial international law. This perspective overlaps with the thesis that international law is indeterminate.Footnote 28 There are two sub-variants of the indeterminacy thesis.Footnote 29 The first, (neo)marxist sub-variant reads the indeterminacy of colonial international law as a deliberate strategy that enabled the exclusion or inclusion of subjects, sources, or objects as the colonial powers deemed it appropriate. Accordingly, international law is a superstructure to legitimize capitalist exploitation. The second, deconstructivist sub-variant claims that indeterminacy renders international legal arguments pointless and arbitrary, oscillating forever between oppression and emancipation. Both sub-variants can be combined, as recent research has shown.Footnote 30 Ntina Tzouvala has elaborated how key concepts like ‘civilization’ were deeply Janus-faced. They served to exclude the ‘uncivilized’ according to the logic of biology as much as they offered them a developmental perspective according to the logic of improvement.Footnote 31 Jochen von Bernstorff tracks similar patterns in the legal discourse justifying German occupations.Footnote 32

There is a lot of merit in these two perspectives on the ambiguity of colonial law. Nevertheless, I wonder whether this is the full story. In fact, these two perspectives show ambivalence rather than ambiguity in colonial international law. No doubt, colonial international law oscillates between the poles of stasis and evolution; biology and improvement. Beyond that, I believe that there is also genuine ambiguity in colonial international law, which results from the identity struggles among the actors involved – states, governors in the colonies, legal scholars, or individual claimants. This presupposes that one understands law not only as a structure that interacts with the economy, but as a defining aspect of the human condition as such. Establishing the law, past and present, and situating oneself in relation to it, is an exercise in identity formation, rather than the revelation of some objective truth.Footnote 33 We construe our identity, personal and social, primarily by distinguishing ourselves from others, and by distinguishing our present identity from past ones.Footnote 34 One can therefore reconstruct the legal status of others under colonial international law and their relationships only against the background of one’s own status and relationships – and the past of international law only against the background of its present.

Seen from this angle, the conventional approach is fraught by ambiguities emerging in colonial contexts for the identity of the colonizers. These ambiguities reflect the general identity crisis of persons and societies in industrial modernity. Industrial modernity threatens people with a sense of ‘anomie’ due to experiences of crisis and isolation.Footnote 35 Colonialism may have been intended as a way of overcoming the identity crisis by creating an ‘other’ around which Western identity could converge;Footnote 36 in fact, it added to this crisis by the inherent contradictions of buying into a racist ideology to spread civilization, as Aimé Césarie argued.Footnote 37 According to Homi Bhabha, the experience of violence in the colonial context unsettles the self-understanding of a rationally ordered, ethical idea of Western society.Footnote 38 One cannot sustain this image while legitimizing brutal violence. Colonial social practices mirror these contradicitons and the vain desire to overcome them.Footnote 39 Colonial international law seeks to paper over them by universalizing the particular: It reconstructs a fictitious ‘prevalent opinion’ that denies agency to non-whites and structures international legal doctrine accordingly, including by Eurocentric canonizations of the sources and subjects of international law.Footnote 40

Colonial international law therefore had to combine and reconcile the appearance of a well-ordered, ethical structure while justifying extreme injustice and violence, all with one single legal vocabulary.Footnote 41 It had to reassure Europeans of their civilization and sustain their self-image as ‘enlightened’, progressive societies while they engaged in unspeakable atrocities. The concept of civilization, to which I will revert below,Footnote 42 is a case in point.Footnote 43 It is worthwile recounting the dual use made of this term by Franz von Holtzendorff. Von Holtzendorff was a German liberal in the progressive sense of the term, an advocate for penal reform and women’s rights.Footnote 44 In his assessment of the Franco-Prussian war, he reminded his fellow citizens of their status as a civilized nation to advocate for clemency in the peace treaty with France.Footnote 45 Only a few years later, he justifies colonial conquest with the advancement of civilization,Footnote 46 conveniently overlooking that peace in a Europe of nation states was made possible by shifting the agression to the colonial battlegrounds. One should, therefore, read colonial international law as the expression of a European identity crisis. It is this aspect of identity crisis that distinguishes the second and third perspectives. Whereas the former resembles a conceptual hare-and-hedgehog game as a discursive strategy of power-thirsty colonizers, the latter emphasizes the vain attempts of colonial law to escape the irreconcilable contradictions which colonialism evoked for the identity of the colonizers.

Exacerbating that identity crisis was the fact that the colonizers themselves were a heterogeneous crowd featuring many different identities and diverging interests. This heterogeneity resulted from the major transformations in North Atlantic societies during the nineteenth century following industrialization, urbanization, bureaucratization, and the rise of capitalism generally. Take the territory of present-day Namibia as an example. In the files of the colonial administration, you will meet tradespersons venturing into unknown territories with their profits in mind, settlers seeking land they could not obtain in Europe, corporals seeking to advance their career at home, companies greedy for mines, missionaries competing to win the most souls for Christianity. Their interests and identities collided as frequently among themselves as they did with those of the autochtonous population.Footnote 47 Add to this the clashes between different colonial powers. How could colonial international law ever be expected to form a coherent whole to allow a ‘prevalent opinion’ to emerge? If at all, then only to cover up these struggles.Footnote 48 The second, post-colonial, approach seeks to reveal this side of colonial international law and to rescue it from its retrospective homogenization.Footnote 49

2.3 Pluralistic approaches

The third approach explores the external ambiguity of colonial international law. This ambiguity results from doubts about colonial international law’s claim to universality and primacy. Colonial international law rests on the implicit assumption that it is applicable everywhere to everyone and takes precedence over other, competing visions of inter-polity law. This assumption objectifies the European viewpoint, as if trying to prove Frantz Fanon right, who held that ‘[f]or the native, objectivity is always directed against him’.Footnote 50 The third approach seeks to debunk this assumption and reveal the positionality of colonial international law by juxtaposing it with competing ideas of inter-polity law. After all, colonial international law emerged in the context of colonial encounters between vastly different actors and groups. Many of them had their own, particular visions of inter-polity law. Colonial settings are therefore characterized by a pluralism of inter-polity laws.Footnote 51 Absent any meta-rules on their scope and order of precedence, their sources or even the relevant subjects, the universality and primacy of colonial international law is couched in ambiguity. All that exists are competing claims and visions of inter-polity law, European and non-European ones.

On a positive note, this opens the opportunity for a truly global history of international law. There have been few attempts to make the inter-policy law of the colonized fruitful for the history of international law.Footnote 52 The methodological premises of such research has yet to be fleshed out in many respects.Footnote 53 It goes without saying that such approaches should not be guided by a positivist, Euro-centric idea of law. The wide, inclusive concept of multinormativity seems more appropriate.Footnote 54 It opens legal scholarship to a wider range of sources, including political, religious, and philosophical writings, oral history, and archaeological sources. It is emphatically not limited to the works of lawyers – which even European international law never was.Footnote 55

On this premise, the article goes beyond the sources of international law recognized by the conventional approach and explores the legal issues raised by the Namibian Genocide from the perspective of the inter-polity law emerging from the letters and records of the captains of traditional communities in Southwest Africa.Footnote 56 Since the middle of the nineteenth century, these captains maintained a lively correspondence with each other and their European counterparts.Footnote 57 I will focus in the following on the writings of two captains, the Herero captain Maharero Tjamuaha (1820–1890) and the Nama-Orlam captain Hendrik Witbooi (1834–1904). Equally ambitious and controversial personalities, each of them left behind extensive writings, which have survived to this day, albeit incompletely. Witbooi’s journals, most of which have been preserved, provide an invaluable insight into his life and thinking. They are in the first place accounting books in which Witbooi meticulously recorded his claims and debts against other captains and Europeans, but Witbooi’s scribes also used them to track his correspondence.Footnote 58 Maharero’s written legacy consists, among other things, of 75 letters preserved in the National Archives of Namibia (NAN) in Windhoek, which the missionary and amateur historian Heinrich Vedder found in the garbage in Okahandja.Footnote 59 In their writings, the two captains release their explicit and implicit views about the normative premises of inter-polity relations.

Of course, the reconstruction of inter-polity law from these writings is all but trivial. It is virtually impossible to read these sources independent of our background knowledge of colonial international law or of European ideas about law generally. How can we be sure we share enough of an epistemology to read their letters faithfuly? Yet, the letters originate in a colonial context, emerging often from correspondence with colonizers. In fact, the development of a basic bureaucratic organization by traditional leaders manifested in their letter culture is the result of colonial influences. The letters therefore reflect colonial encounters and anti-colonial thinking rather than pre-colonial traditions. Moreover, one needs to keep in mind that the two captains only raise claims in their letters. One should not objectify and homogenize their views just as the conventional approach objectifies and homogenizes colonial international law. In this regard, it would be the task of another study to contrast the claims raised in the letters with other sources, including oral history.

The following sections will put the ambiguity of colonial international law to a test. They compare the three approaches with regard to legal issues crucial for evaluation of the Namibian genocide to challenge the notion that ‘it was all legal’.

3. The international legal status of Southwest Africa

The legal status of colonized territory under international law is a fork in the road for many issues of colonial international law, including reparation claims. The three approaches lead to widely diverging results about the legal status of Southwest Africa under German rule.

3.1 The conventional approach

It suffices to summarize the conventional view here.Footnote 60 Accordingly, Germany lawfully obtained sovereignty over Southwest Africa by occupying a so-called terra nullius.Footnote 61 This doctrine of occupation undergirds Articles 34 and 35 of the General Act of the Berlin Conference. Accordingy, states were allowed to occupy and annex territories uncontrolled by any other subject of international law.Footnote 62 The argument goes that the traditional communities of Southwest Africa did not enjoy international legal personality because they did not belong to the exclusive circle of civilized peoples. Moreover, as nomads, they also lacked effective territorial control. By establishing effective control, Germany acquired sovereignty over Southwest Africa. Only German law, rather than international law, therefore governed relations between the traditional communities and Germany.Footnote 63

3.2 Post-colonial approaches

The conventional view invites a post-colonial critique as it is based on two highly ambiguous notions: membership in the circle of civilized peoples; and control over a specific territory. Both criteria reflect the colonial powers’ troubled identity. The criteria are somewhat overlapping, as the manner in which territorial rule is exercised by a community allows drawing conclusions about its level of ‘civilization’.

3.2.1 Civilization and international legal personality

No other legal concept expresses the idea of ‘othering’ with greater clarity than the nineteenth century requirement that subjects of international law belong to the ‘civilized peoples’. Its main function was to consolidate Europe despite its heterogeneity and internal conflicts. This made the concept of civilization entirely obscure.

While the concept’s history reaches back several centuries,Footnote 64 it became an organizing principle for the international order only during the Sattelzeit. The enlightenment ideas of liberty, rationality, and progress instilled in Europeans a sense of superiority and put them on a mission for the worldwide expansion of their civilization.Footnote 65 Hence, we have to understand nineteenth century imperialism as a constitutive part of the idea of the enlightenment. A case in point is Kant’s treatise on Eternal Peace. Considering it a moral duty to establish a world federation of states entailed that the rest of the world had to emulate the political organization of the civilized Northern Atlantic states.Footnote 66

Civilization quickly acquired a legal connotation. The first international law treatise appearing after the Vienna Congress, Ludwig Klüber’s 1819 Droit des gens européen, in a passage alluding to Kant’s Eternal Peace, held that the European peoples, including Northern America, form a special legal community.Footnote 67 The rationality of European international law allowed the exclusion of the others. Only that Klüber did not use the word ‘civilization’. This had to wait until 1836, when Wheaton referred to the Northern Atlantic states as the ‘civilized states’.Footnote 68 Civilization was now in its prime, dividing the world into conquerors that enjoyed the capacity to concluded treaties to ensure the balance among them, and into the (yet to be) conquered, which could only form the object of such treaties.Footnote 69 A number of ‘half-civilized’ states were pushed back and forth between these categories as the situation required.

However, the notion of civilization had a paradoxical effect on international law and European identity. Civilization laid the foundation for an expansion nourished by the idea of progress. It would ultimately elevate the ‘uncivilized’ to the status of civilized people, sending Europe’s identity into crisis, and endangering its power interests. It was therefore rational for Europeans to deprive non-Europeans of the status as civilized peoples as far as possible. The trick was to shift back and forth between emancipatory and racist understandings of civilization.Footnote 70 For example, on the one hand, liberals like von Holtzendorff considered traditional communities in the colonial territories as underage children that were to be educated.Footnote 71 On the other hand, Germany introduced impermeable legal barriers between whites and non-whites in the protectorates.Footnote 72 That status difference had nothing to do with civilization in the broadest possible meaning of the term, but a lot with racism. The colonial administration made status change impossible, e.g., by prohibiting inter-marriage.Footnote 73

As a result of these tensions and paradoxes, the concept of civilization in international law remained highly disputed and contradictory throughout the nineteenth century.Footnote 74 This makes it impossible to retrospectively reconstruct the concept as a monolithic, meaningful one as the conventional view does. These controversies reached their apex when the Institut de Droit International failed in two attempts to concretize it. In 1885, when the Institute set about defining the concept of occupation referred to in the Final Act of the Berlin Conference, Friedrich von Martitz proposed that any territory not occupied by civilized peoples should be considered terra nullius and therefore capable of legitimate occupation.Footnote 75 In the discussion relating to the concept of civilized peoples, the French ambassador Engelhardt in particular took a stand against Martitz’s view. Engelhardt, a cosmopolitan career diplomat, pointed out the high degree of political organization prevalent in some African empires such as the Egbas. Although they differed from modern bureaucratic statehood, Engelhardt pleaded to understand these empires as normative orders in their own right.Footnote 76 This apparently convinced many members of the Institute. In the end, the Institute’s final resolution skirted the question of the requiremenets for making a territory susceptible to valid occupation. Another commission of the Institute established in 1879 sought to clarify the consular jurisdiction of European states in the states of the Orient. Touching again upon sensitive questions of civilization, it never came up with a resolution.Footnote 77

The events at the Institute reflected disagreement in the scholarship of the time. The textbooks of the period differ significantly on this point. Membership in the group of civilized nations is mentioned as a prerequisite for statehood in the standard works of Lawrence, Westlake, or Heffter (which bears the telling title ‘European International Law’), but is absent in the writings of Moore, von Liszt, or Solomon.Footnote 78 To the extent that the criterion was still upheld in the literature, its meaning mostly boiled down to the ability to participate in international relations and especially to enter into legal agreementsFootnote 79 – which in turn placed the criterion entirely in the hands of the colonial powers that unilaterally decided to conclude and ignore treaties at will. Against this background, Charles Salomon doubted the suitability of the concept of civilization for international law in 1889.Footnote 80 One year later, Gaston Jèze concluded with regard to the debates at the Berlin Conference that the civilization requirement no longer constituted a valid part of international legal doctrine due to its internal contradictions.Footnote 81

Overall, the concept of civilization marks the epitome of a European identity crisis. Its ambiguity reveals the insurmountable contradiction between European expansion and Europe’s civilizing mission. Hence, the International Court of Justice has ignored this concept when adjudicating past issues.Footnote 82 It calls into question the monolithic character of colonial international law cultivated by the conventional view.

3.2.2 Territorial control

Along similar lines, the view that the traditional communities residing in Southwest Africa lacked territorial control over their traditional lands is difficult to maintain, as the relevant standards are fraught with ambiguity. On the one hand, it is unclear what degree of territorial control was required for an area not to be considered masterless; on the other hand, considerable misconceptions about the relations of traditional communities to their territories blurred European analyses at the time.

In theory, any territory that did not meet Jellinek’s criteria of sovereign statehood was considered ‘masterless’.Footnote 83 The exact degree of territorial control required under it remained largely unexplored, however. One needs to understand the idea of territorial control against the background of the emerging bureaucratic state in industrialized countries, as described by Max Weber.Footnote 84 That concept was developed to distinguish the industrialized countries from supposedly less developed forms of territorial rule.Footnote 85 According to a frequently encountered view, non-European urban cultures of the Near East and South and East Asia possessed sufficient territorial control, but not ‘nomadic barbarians’.Footnote 86 These classifications probably tell at least as much about the classifiers as about the classified; one needs to understand them as acts of othering.

Requiring a high degree of territorial control, however, would have raised the bar for European colonial powers and placed a huge burden on their expansion. Hence, the Berlin Conference remained relatively vague on the concept of territorial control. According to Article 35 of the General Act, the power seizing possession of a coastal strip had ‘to ensure the existence of an authority sufficient to protect acquired rights and, where appropriate, freedom of trade and transit under the conditions agreed upon for the latter’.Footnote 87 Importantly, the ability to secure peace in the affected territory was removed from the draft for fear of being drawn into conflicts among the local population. The measures necessary to achieve these goals were left to the discretion of those implementing them.Footnote 88 Tellingly, the French ambassador noted that in certain cases it would be possible to rely on existing institutions.Footnote 89 If, however, existing institutions of traditional communities were capable of allowing Europeans to exercise territorial control through them, it would become difficult to argue that the territory was terra nullius in the first place. Unimpressed by the apparent double standards, the proposal actually made it into the resolution of the Institut de Droit International Law – again at the suggestion of a French delegate.Footnote 90

Proposals in the literature do not provide much clarification. Von Holtzendorff vaguely speaks of the ‘establishment of maritime institutions of powers’ or the ‘establishment of judicial and administrative authorities’, but then admits that this would not require much more than an ‘act of landing’ or the ‘stationing of any force’ on the respective territory. Larger military forces were deemed unnecessary and occupation was assumed even if its success was not yet permanently assured.Footnote 91 In particular, the occupying power would not have to be constantly present with its troops ‘at all threatened points of a certain territory’ or be able to intervene immediately.Footnote 92

The ambivalence surrounding the notion of territorial control persists to this day in the case law of the ICJ. On the one hand, it recognized as early as 1975 in the Western Sahara case that traditional communities exercised sovereignty over the territory in question despite having comparatively weak territorial ties at the time of Spanish colonization in 1884.Footnote 93 On the other hand, in Cameroon v. Nigeria, it remained unclear which significance the ICJ attached to the 1884 protection treaty concluded between Great Britain and traditional leaders of the Bakassi Peninsula. At one point, the court refers to the Western Sahara case, which indicates acquisition by treaty, requiring traditional leaders to exercise territorial control. At another point, the court questioned the effectiveness of the rule exercised by the traditional leaders, which relied chiefly on personal loyalty.Footnote 94 Based on such vague, contradictory standards for territorial control, one can once more have doubts about the conventional approach. In line with this finding, various domestic courts have recognized indigenous land rights in different contexts, undermining the assumption of terra nullius.Footnote 95

Yet, standards are only the first ambiguous element. The second element relates to misconceptions and racist stereotypes concerning the conditions of life of traditional communities at the time. International law textbooks seem to imply that traditional communities with ‘nomadic’ lifestyle did not stand in a close relationship to their territory. Historical research on Southwest Africa in the nineteenth century contradicts this. Under the influence of European colonialism, emanating especially from the Cape Colony, the structure of many traditional groups had changed considerably. Being originally based on personal allegiance (kinship), they gave way to larger, more hierarchical and steadier associations based on ethnicity.Footnote 96 This was accompanied by a less nomadic, more territorial lifestyle and, especially for the Herero, extensive cattle ownership.Footnote 97 Major settlements were mostly established in geographical proximity to mission stations.Footnote 98 Other points of stability were water holes, while the boundaries between different groups were subject to dynamic change as a result of repeated conflicts between the different groups.Footnote 99 Hence, the traditional captains did indeed control the use of their core territories.Footnote 100 In recognition of this new social and territorial reality, the German colonial administration, too, assumed that the captains exercised some official, political form of ‘dominion’ that exceeded the powers of private landowners.Footnote 101

To summarize, the assumption that traditional communities lacked territorial control was based on an ambiguous standard regularly applied following prejudice rather than proper judgment. The conventional view was imbued by the contradictions of European identity struggles. Europe’s self-image of a well-ordered society based on the concept of the nation state and territorial control clashed with their difficulties in gaining control over overseas territories, not least because these territories were all but unoccupied. Aggravating these difficulties was the fact that at this point in time, to establish territorial control, it was no longer possible to refer to property ownership,Footnote 102 as the distinction between property and sovereignty became determinative of the modern state.

3.3 Pluralistic approaches

Let us now turn to Hendrik Witbooi and Maharero. At the outset, it seems apposite to investigate the normative order they deemed to govern relations between themselves and other groups. Colonial international law in the conventional view denied them legal personality, but was it relevant to them at all? Moreover, how did they understand their relationship with territory?

3.3.1 Inter-polity law

In the second half of the nineteenth century, conflicts between the Ovaherero and Namaqua abounded, triggered by climatic and demographic conditions that pushed the Namaqua away from the Cape Colony to the north, provoking conflicts with the Herero. Europeans arriving in larger numbers further complicated the situation. In this context, the correspondence between Witbooi and other Nama and Herero Captains revolves around the normative premises governing their relationships with other groups. As different groups pacted at different periods with Europeans to gain advantages, the question soon arose whether the Europeans were just another group among many or should be categorically distinguished from autochtonous groups.

Interestingly, law becomes an important point of distinction that called colonial international law’s claim to universality into question. As encounters with Europeans intensified in the 1870s, Jan Jonker in a letter to Maharero highlighted different legal traditions as a crucial feature separating Africans from Europeans:

Our country is full of different people and they are familiar with the laws of the Cape Colony … This makes it a challenge for us to cultivate true friendship with each other for the benefit of our country and peoples.Footnote 103

Hendrik Witbooi challenged the universal aspirations of colonial international law even more directly, offering the alternative vision of a pan-African legal community. In fact, Witbooi was among the first to consider the Europeans not simply as yet another community settling in the Southwest, as he recognized the fundamental threat posed by colonialism to pre-colonial society. In reaction, he attempted to tune down conflicts between traditional communities and form alliances against the Europeans. It is against this background that Witbooi protested to the Nama Captain Joseph Fredericks, who owed him allegiance, for assigning farms on his territory to Europeans:

For I think this part of Africa is the territory of Red chiefs. We are one of colour and custom. We obey the same laws, and these laws are agreeable to us and to our people; for we are not severe with each other, but accommodate to each other, amicably and in brotherhood. And if the people of one chief want to live with another chief’s people, in his settlement, they can do so in peace, and both chiefs are content. They do not make prohibiting laws against each other, concerning water, grazing or roads; nor do they charge money for any of these things. No, we hold these things to be free for any traveller who wishes to cross our land, be he Red, White, or Black … But with White people it is not so at all. The White men’s laws are quite unbearable and intolerable to us Red people: they oppress us and hem us in in all kinds of ways and on all sides, these merciless laws which have no feeling or tolerance for any man rich or poor.Footnote 104

Another letter to Maharero conveys the same sense of pan-Africanism.Footnote 105 Overall, there are no indications that traditional leaders accepted colonial international law, precisely because they saw major differences between Europeans and Africans in the law.

If Hendrik Witbooi and Maharero did not accept colonial international law, which legal order should govern the relationship between the colonial powers and the colonized communities? At best, one might distinguish between a thin layer of universal legal rules and a thicker layer that regulates the relationship between local groups.Footnote 106 This requires further, systematic study of the sources. In any case, the pluralism of international law gets in the way of the claim that ‘it was all legal’.

3.3.2 Territorial control

What did the normative order that Witbooi and Maharero deem to apply among traditional communities say about territorial control? What where the contours and content of their claims to territorial control? Ample written evidence exists on this issue. Even if tactical reasons may have motivated some claims, the resulting picture testifies to the ambition of the captains to exercise a high level of territorial control.

This reflects a shift towards a more territorial and more political understanding of communities. That shift was ongoing at least since Maharero emerged victorious from the conflicts with the Nama-Orlam of the 1860s. After the peace of Okahandja in 1870, he gave Windhoek to the Nama-Orlam leader Jan Jonker Afrikaner as a loan.Footnote 107 Jan Jonker apparently accepted Maharero’s territorial control. For example, he asked for permission to have a merchant settled.Footnote 108 The expansion of Herero rule under MahareroFootnote 109 led to a stratification and territorialization of power relationships,Footnote 110 which shines through in a dispute between Jan Jonker and Maharero. Apparently, Herero had murdered some Bergdamara (a group controlled by Jan Jonker), but the local leaders could no longer hold them responsible because their leader Jan Jonker was now under Maharero’s rule.Footnote 111 At the same time, Jan Jonker and Maharero co-operated to protect their territorial control against Boer settlements.Footnote 112

The political character of such hierarchical and territorial relationships had yet to develop, though. Terminological ambiguities are indicative of this transition. For example, in a letter written in 1871, Maharero states that the Baster van Wyck received Rehobot from him as his property (‘tot sein eigenthom’).Footnote 113 In a letter from 1878, van Wyck acknowledges that he is not staying here in his own right, but thanks to Maharero’s permission (‘ob U vergonnung’).Footnote 114

Similarly, it was not always clear whether land was to be politically controlled or rather an asset of the captain acting on behalf of his group. While Maharero, in the course of the conflict with Jan Jonker in June 1876, based his territorial authority on the fact that his ancestors were buried thereFootnote 115 – a common reference even in today’s Namibia – he was simultaneously negotiating with the British envoy Palgrave in September 1876 about the establishment of a protectorate. Although this transaction would not have affected his jurisdiction over the Herero, it would have implied the comodification and cessations of land.Footnote 116

As the Germans arrived, however, the political and territorial character of traditional rulership emerged with greater clarity. Maharero soon realized German rule as a threat to his position. This led him to assert his territorial and political control with greater insistence. Thus, when the Nama captain Piet Haibib agreed with Lüderitz in 1884 to buy large areas of land at an alarmingly low price of 40 Marks,Footnote 117 Maharero responded with the following proclamation, drafted in German and Otjiherero:

I, Maharero, Chief of Damaraland [traditional name for Hereroland], hereby declare on behalf of and with my sub-chiefs that the borders of my country are as follows:

1. to the north the whole Kaoko area up to the coast,

2. to the south, the Tsoachaub and Omaruru areas up to their estuaries,

3. to the south, the Rehobot area, which I have granted to the bastards allied with me,

and hereby protest most earnestly against all and every acquisition of land and minerals within these stated limits, by whomsoever it may be acquired or purchased except by me, as against all right and therefore as completely void.

Written from the mouth of Mahareros by his

Secretair

William Kaumunika.Footnote 118

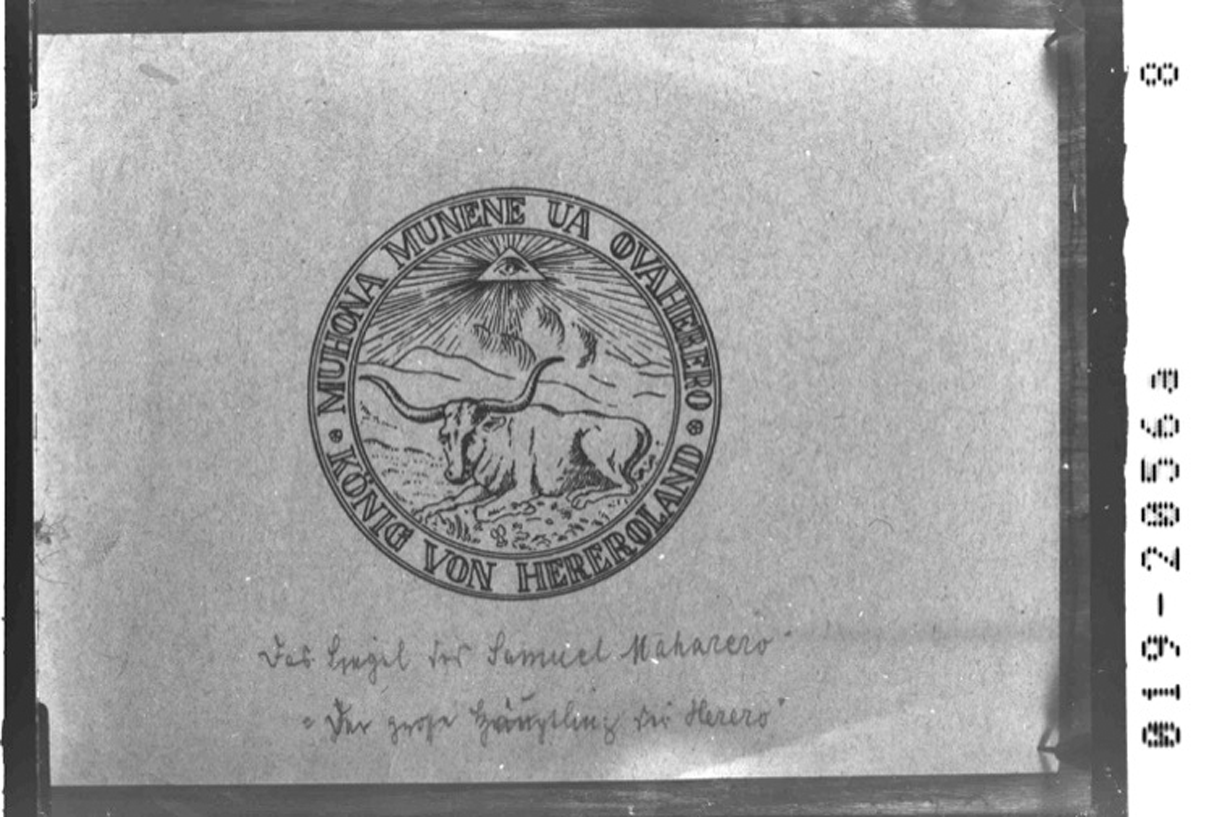

Rather than using land as a disposable asset only, Maharero now considered it as a basis of his political authority. The colonial encounter seems to have instilled ideas of territorial control taken from the colonizers. This is underscored by Maharero’s emulation of European symbols of power. For example, he used a seal since 1884 that identified him as ‘King of Hereroland’ (Figure 1):Footnote 119

Figure 1. Maharero’s seal. Picture archive of Deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft, University Library Frankfurt am Main, no. 019-2056a-08.

This did not remain an isolated case. Pieter Haibib promptly reacted with a similar statement:

Proclamation. I, Piet Haibib, therefore say: I have heard Kamaharero’s Proclamation; but I protest against it & hereby make known the borders of my country. My territory is the whole Kuisib area up to Gansberg & from there to Onanis & Horobis in the Zwachaub & from there to Karibib, in a straight line from there to the sea. So the copper mines, which are on this my land belong to me & who sells something from this land without my consent is doing wrong.

Walfischbay 1 Octbr 1884

signed Piet HaibibFootnote 120

Another incident confirms the political character of the captains’ control. It relates to a dispute between Maharero and the missionaries over the sale of a building on the mission’s grounds in Okahandja in 1888. The mission wanted to grant a merchant private ownership of a plot of land belonging to the mission. Maharero protested sharply:

I thought I would keep the key to my house.Footnote 121

The conflict escalated when Maharero banned the mission from ringing bells and questioned the protection treaty with the Germans, which prompted the Imperial Commissioner Göring to flee to Walvis Bay.Footnote 122 In this conflict Maharero also invoked his responsibility for the graves of his ancestors, who had made the land unsaleable.Footnote 123

With the consolidation of territorial control, border transgressions became a frequent bone of contention. For example, in a letter dated 7 November 1889, the Nama leader Willem Christian complained to Witbooi as follows:

But now, my dear Friend, it appears that you came within my borders without letting me know, or asking me for whatever you need in my district. I therefore, dear Captain, request you kindly to go back, lest there be unpleasantness between us. It really is beyond me how one captain can enter into the district of another without letting him know, or without seeking permission.Footnote 124

When Maharero concluded a second protection agreement with the Germans because of the war with the Nama, Witbooi reacted outraged, asserting the territorial sovereignty of traditional groups:

I learn from this letter that you have given yourself into German Protection, and that Dr. Göring has thus gained the power to tell you what to do, and to dispose as he wills over our affairs, particularly in this war of ours with its long history. I am amazed at you, and take it very ill of you who call yourself the leader of Hereroland. That you are indeed. This dry land is known by two names only, Hereroland and Namaland. Hereroland belongs to the Herero nation, and is an autonomous realm. And Namaland belongs to all the Red nations, and these too are autonomous realms – just as it is said of the White man’s countries, Germany and England, and so on, whatever these countries are called.Footnote 125

Territorial sovereignty was not incompatible with the idea of a universal order:

No other captain or leader has any right to force his will; for every leader on this earth is merely a steward for our common great God, and is answerable to this great God alone, the King of kings, the Lord of lords …Footnote 126

When the German authorities tried to convince Witbooi to conclude a protection agreement, Witbooi unequivocally rejected their offer, insisting on the exclusive character of territorial sovereignty:

An independent and autonomous chief is chief of his people and land – because every ruler is chief over his people and country, to protect it himself against any danger or disaster which is threatening to harm his people or land. That is why there are separate kingdoms, and each ruler rules his own people and country. It is thus: when one chief stands under protection of another, the underling is no longer independent, and is no longer master of himself, or of his people and country.Footnote 127

It seems that the captains of traditional communities had developed a political understanding of the control they exercised over their territories. While the commodification of ancestral lands remained a temptation, the captains often resisted such attemts and respected the spiritual relationship between their communities and their land.Footnote 128 Moreover, and perhaps different from traditional understandings, they understood political control as exclusive. This understanding emerged well before Witbooi was forced to sign a protection agreement after his defeat at Hoornkrans in 1894.

4. Genocide and inhumane treatment under international law

4.1 The conventional approach

As indicated above, the prevalent opinion in contemporary German international legal scholarship is of the view that the 1904 genocide and inhumane treatment of the Herero and Nama did not constitute a violation of international law at the time due to the lack of international legal subjectivity of these communities.Footnote 129 Hence, only domestic German law applied, and at the relevant time, it provided no basis for reparation claims. Liability of civil servants under Section 839 of the German Civil Code did not apply because civil servants were under no official duty to protect the inhabitants of the colonies against inhumane treatment.Footnote 130

Even if one were to assume the applicability of international law, as argued in the preceding section, the victims of German colonialism could not claim reparations following the conventional view. The protection treaties are deemed to lack binding legal force,Footnote 131 to entail a right of occupation,Footnote 132 or they are considered terminated by the outbreak of war.Footnote 133 The 1948 Genocide Convention defies retroactive application.Footnote 134 Article 6 of the Final Act of the Berlin Congress obliged the German Empire to protect the autochtonous population. However, some derive from the context of the Final Act that this obligation was under the proviso that it would not endanger colonial rule.Footnote 135 Moreover, the Final Act only applied between the signatory states and did not give rise to rights and obligations of third parties.Footnote 136 The (Second) Hague Convention on the Laws and Customs of War and annexed Regulation of 1899 were only applicable among contracting states.Footnote 137 Even the Martens clause of the preamble does not help in this view. Accordingly:

Until a more complete code of the laws of war is issued, the High Contracting Parties think it right to declare that in cases not included in the Regulations adopted by them, populations and belligerents remain under the protection and empire of the principles of international law, as they result from the usages established between civilized nations, from the laws of humanity and the requirements of the public conscience.Footnote 138

The clause is said to merely refer to the customary international law in force at the time, applicable only among ‘civilized’ states.Footnote 139 Although an expansion of the Red Cross Convention of 1864 to colonial wars had been debated for some time during the nineteenth century, it was never accepted by the colonial powers due to a lack of reciprocity.Footnote 140

Finally, colonial-era scholarship postulating a humanitarian minimum to be respected in relation to colonial peoples as a matter of international law is played down. International law at the end of the ‘long’ nineteenth century, it is claimed, was characterized by positivism.Footnote 141

4.2 Post-colonial approaches

A post-colonial perspective is able to carve out ambiguities in colonial international law which reflect the colonial powers’ shaken self-image. In the context of the Namibian Genocide, the ambiguities comprise the contradictory classifications of protection agreements and the uncertainty surrounding the principle of humanity. The two categories are relevant insofar as they might guarantee rights of the affected victims or at least standards of behaviour undermining the claim that the Genocide and related inhumane treatment was in conformity with international law.

4.2.1 Protection agreements

The legal nature and content of the protection agreements is mired in legal ambiguity. It reflects the vain attempt to conquer colonial territories while respecting the rule of law. Nevertheless, upholding the image that the rule of law would be respected was crucial to sustaining the self-image of colonial powers as forces of civilization. Consequently, it is unclear whether the protection agreements would be legally binding, and what kind of protection they would actually encompass for the autochtonous population.

Regarding the legal nature of the protection agreements,Footnote 142 this paradoxical setting prompted almost desperate attempts on the part of legal scholarship to simultaneously vindicate and downplay the legal significance of the protection agreements. On the one hand, they did play a significant role in allowing Germany to claim overseas territories. Germany hardly exercised effective control over the territories in question at the time it claimed them as colonies.Footnote 143 It therefore required the loyalty of the local population. On the other hand, considering the protection agreements as international treaties and honoring them would have created protectorates with their own legal capacity, thereby compromising Germany’s plan to control and suppress the territories and their population. This constellation led to considerable ambiguity in scholarly discourse on the legal nature of the protection agreements.Footnote 144 Scholars like von Martitz and Stengel held that the protection agreements should only prevent the other European powers from claiming certain territory. Still, they claimed the protection agreements had legal significance for the local population, which, despite lacking international legal personality, apparently had sufficient legal personality of some other kind to recognize Germany’s authority over them.Footnote 145 Many agreed and invented new concepts like ‘qualified occupation’ to maintain the superstition that the territories in question had been unoccupied.Footnote 146 A second group distinguished between occupations as the basis of acquisition in relation to other empires, whereas protection agreements would be needed to lawfully acquire territories from their population.Footnote 147 A third group attributed a private law character to the protection agreements,Footnote 148 while a fourth, smaller group considered the agreements as constitutive of German sovereignty.Footnote 149 After all, Germany paid meticulous attention to the correct ratification of these agreements by the traditional communities concluding them.Footnote 150 Moreover, downplaying their significance hardly reflected colonial practice, including the acquisition of land,Footnote 151 in particular in North America,Footnote 152 not to mention the somewhat diverging interests of the French and British governments.Footnote 153 Hence, the impossibility of justifying outright injustice clouded the legal qualification of the protection agreements, thereby calling into question the entire legal framework for the exercise of sovereign rights in the former protectorates.

A similar amount of ambiguity afflicts the content of the protection agreements. As the overwhelming majority of scholars referred to in the preceeding paragraph considered the protection agreements as legally significant in one way or another, one might wonder which rights and duties actually derived from them. In this respect, the protection agreements are remarkably vague.Footnote 154 Germany usually promised protection to the traditional group. A typical example is the 1885 treaty concluded between the Reich and Maharero, which was terminated in 1888 but subsequently reaffirmed.Footnote 155 Article I invokes the friendly relations prevailing among the parties. The emperor then ‘assures’ Maharero of his protection. Read in the context of the other provisions of the agreement and the circumstances of its conclusion, this assurance primarily envisages military protection against other groups, particularly against the Nama-Orlam led by Hendrik Witbooi.Footnote 156 Still, would the granting of such important protection be reconcilable with a right to suppress and ultimately exterminate the protected group? The agreements remain silent on the issue. Later agreements often contain a provision in which the traditional leader pleads to observe the applicable German law.Footnote 157 One could derive from this the obligation on the part of Germany to respect the rule of law. After all, this provision implies that Germany exercises power through law, rather than by the arbitrary will of German colonial officials. Again, this provision begs the question how one should possibly understand the entire machinery of colonial suppression as government by law.

One way of solving the paradox would be to rely on a purely formal rule by law, rather than the rule of law, which evoked positive connotations even during colonial times.Footnote 158 However, atrocities like Lothar von Trotha’s infamous extermination order are hard to reconcile with even the most formal understanding of the rule of law. For one, it remains obscure whether Trotha was authorized to issue the respective order. The only evidence that the emperor had given him the requisite instructions is his own testimony.Footnote 159 Moreover, it is unclear to what extent the order was approved by the general staff. The emperor’s consecutive order to Trotha of 9 December 1904 ‘to show mercy to Hereros who volunteered to surrender’Footnote 160 is open to different interpretations. Further compounding the legal situation is the fact that until the Battle of Waterberg the division of powers between the civilian colonial administration under Governor Leutwein’s control and Trotha’s Schutztruppe, in which Leutwein only had the rank of a corporal, was genuinely unclear and disputed.Footnote 161 Finally, even if Trotha’s elimination order had been valid under German law, it certainly exceeded what the Herero could be expected to respect under the protection agreement. One might rationalize this consideration as a violation of the reciprocity requirement underlying the protection agreement like any other treaty, or as a case for the implicit clausula rebus sic stantibus.Footnote 162

Overall, if the protection agreements were all but a fraud, which in itself would throw a dubious light on German colonialism, they are notoriously difficult to reconcile with the genocide and related atrocities. Colonial violence imbues colonial law with essential ambiguity.

4.2.2 Principles of humanity

Another case of legal ambiguity concerns the principle of humanity, which oscillates between lex lata and lex ferenda, emphasizing the civilizing mission of colonial international law while relegating its implementation to another day. ‘Humanity’ was a ubiquitous reference point in nineteenth century international law. In fact, it derived from the Enlightenment idea of civilization – with both its emancipatory and its expansive side. This is once more evident in Kant’s Eternal Peace. Accordingly, the world federation serves to secure peace and freedom; for this purpose, the European states are to carry it into the world.Footnote 163

The integration of the idea of humanity into international law was not long in coming. The Declaration on the Prohibition of the Slave Trade in the Final Act of the Congress of Vienna mentions a ‘principle of humanity’ for the first time in an international legal document. It has an affinity with ‘general morality’, but the declaration distinguishes the two terms at a conceptual level.Footnote 164 One of the more tangible consequences of the principle of humanity was the prohibition of looting for victorious warring parties, which arose in the aftermath of the Coalition Wars.Footnote 165 This prohibition, however, governed the relations between European powers. In a colonial context, states typically invoked the idea of humanity primarily when it corresponded to their strategic interests.Footnote 166 For example, the enforcement of the ban on the slave trade was sometimes used as a justification for colonial rule.Footnote 167

Hence, humanity existed at the margins of the nineteenth-century international legal order. That order itself, however, was quite different from today’s. International law between 1815 and 1918 often oscillated between rules and desiderata, between law and morality, with a tendency towards positive law near the end.Footnote 168 The gaps in international legal practice required legal scholarship to analogize and extrapolate from existing rules. Consequently, even towards the end of the long nineteenth century, important textbooks on international law often referred to Roman law, moral-philosophical writings, or even the works of the classics of natural law such as Grotius, Pufendorf and Vattel, to substantiate their claims to the existence of certain rules.Footnote 169

The humanity principle is exemplary of this ambiguity. The international legal literature of the time contains ample reference to a humanitarian minimum that ruled out at least obvious and serious inhumane acts against non-Western societiesFootnote 170 or against the civilian population in the event of war.Footnote 171 The boundary between lex lata and lex ferenda was, however, rather fluid. In 1821, for example, Klüber characterized the behaviour expected from civilized states in armed conflict as ‘wartime manners’. Violations of wartime manners were ‘not unlawful, but nevertheless immoral to a high degree’.Footnote 172 Klüber added that exceptions to wartime manners would only be considered ‘permissible … as countermeasures, or under other extraordinary circumstances’. Whether ‘permissible’ functions here as a legal or moral category is hard to infer. The aforementioned quotation may speak for morality, but a few sentences later Klüber writes: ‘The natural law of nations approves the same (exceptions to the use of war) as far as they are appropriate to the purpose of the war …’Footnote 173 Similar contradictions are contained in the 1867 edition of Heffter’s textbook. Accordingly, restrictions on warfare belonged to the realm of honor and ‘humanity’. However, certain types of warfare, such as the use of poison, were ‘absolutely forbidden, because inhumane’.Footnote 174

Only one year later, Bluntschli’s textbook impressively demonstrated the ambiguous character of the humanitarian minimum in colonial contexts. Accordingly:

At present, the modern sense of justice is even less sensitive to wild tribes. International law does not protect them, because it is considered they do not belong to the great families of peoples that make up civilised humanity, because they have no active interest in the application of international law. I see this as another shortcoming in today’s international law. Because if the wild are human beings, they must be treated humanely and not denied all human rights. They may be difficult to get used to a legal system; their education to become civilized people may be an ungrateful business, which rewards great efforts with only little success. But it is still the task and the duty of the civilized peoples to take care of this training of the roughest tribes and to educate them to a more humane state. It must never again be admitted that the hunt for wild people is free to everyone or may be permitted by the authorities, just as the hunt for foxes and wolves.Footnote 175

Bluntschli’s statement that traditional communities should not be denied all human rights might at first sight appear to relate to the field of morality. However, human rights enjoy an ambiguous status in Bluntschli’s thinking. For him, the abolition of slavery ‘recognized the natural human right of the person’.Footnote 176 Similarly, Martens’ work also plays with the ambivalence between positive law and supra-positive, humanitarian ideas.Footnote 177 Outright calls to massacre ‘non-civilized’ peoples if needed were rare.Footnote 178

Taking together these findings, one cannot exclude with certainty that humanity had no legal significance in nineteenth-century international law. According to Mégret, the ambiguity is related to the high level of trust in the chivalry of colonial officials.Footnote 179 This allowed blurring the boundary between law and politics or morality, calling into queston the conventional view that all was legal.

4.3 Pluralistic approaches

Let us hear Hendrik Witbooi and (Samuel) Maharero on the treatment due to the autochtonous population. Of interest in this context are the laws of war. War was ubiquitous in Southwest Africa in the nineteenth century. Two northward moves of the Witbooi towards the Hereroland in the mid-1880s led to repeated armed clashes with the Herero. The conflict persisted until the two groups concluded a peace agreement in 1892 under the impression of the increasing German presence.

This conflict prompted the formulation of a normative framework for warfare in the letters of traditional leaders. For Hendrik Witbooi, the conflict was governed by legal rules applicable to the relations between the two communities. In a slightly different context, he even spoke of the ‘laws of war’.Footnote 180 In a letter to Maharero from 5 January 1890, Witbooi gives an impression of what he believed to be the content of these rules:

While I was away you came and destroyed my settlement. You killed women and abducted children. Concerning the death of the men I will not say a thing …

Now I ask you seriously: what moved you to kill my women and to carry my children away as prisoners? Do not set such examples. Return my people. Let us see how the Lord disposes in our war. Women and children are innocent of our conflict. You have not defeated me yet, so do not take my children yet. Return them all forthwith … I will wait for the return of the children or an answer, but I will be busy. I will not touch women and children, however, until I receive an answer from you.Footnote 181

Accordingly, Witbooi draws a distinction between soldiers and civilians and demands Maharero to save the latter. Interestingly, he does not understand these rules as reciprocal obligations, which might point to an ethical foundation.

Later that year, Hendrik Witbooi complained about the Herero to Commissioner Göring, who in the meantime had formed an alliance with the Herero. In a letter dated 29 May 1890, Witbooi sketches a picture of the Herero as serious war criminals:

Wherever they find a person alone, they immediately plan to kill him, without provocation or reason, in the open or at his home, whether this person had done something or not. They respect no one, they fear no one, no God and no man. They do not discriminate, they merely kill, man, woman, child, or servant; Red, or White. Such notorious butchers are the Herero. Last year they came and killed my women and children, as you probably had heard.Footnote 182

Witbooi reveals the normative basis of the framework of rules he believes to be applicable in a letter to Maharero, complaining about his alliance with the Germans:

You know that this war is not lawless, and was not begun without a cause, but that it arose from your righteous deads, from the murderous heart of your people … so that you cannot spare a single person you find in the veld, but must plot to murder him without guilt or provocation. To kill in war is legitimate work, but even in this respect you go too far. Inhumanly your people hack others to death, slit the throats of living people … You regard no person a human creature of God …Footnote 183

Witbooi deems a humanitarian minimum to be applicable on the grounds of the Christian idea of imago dei. In this respect, he found himself on common ground with Europeans. Significantly, Leutwein, who, unlike Witbooi, always called Witbooi by his first name, wrote to him in 1894 in the context of an impending armed conflict:

I hope we shall agree to conduct this campaign, which has become inevitable thanks to your truculence, humanely; I also hope it may be brief.Footnote 184

Another subject of discussions were questions of ownership and property arising in the context of war. Hendrik Witbooi distinguishes peace negotiations from ordinary warfare. In diary entries of 27 June 1890, he complains about Maharero’s ambush on the occasion of peace negotiations in 1880, during which horses and guns were taken from him.Footnote 185 By contrast, in ordinary war, Witbooi insisted on making loot, as a letter to Willem Christian shows. The missionary wanted to buy land from the Veldschoendragers, which Witbooi considered his own because of a previous victory over them:

It is now my land, by every law and custom of the world, for when two nations go to war and one is beaten, then he forfeits all to the other, livestock and land. And this is how it stands with the Veldschoendragers. They no longer hold the right to negotiate over that land or to do anything with it.Footnote 186

Witbooi affirms this view in a letter to the English concerning his grandfather’s victory over the Nama captain Cornelius Oasib, once a dominating Nama leader, using explicit legal terminology:

… old Oaseb’s land is mine, clearly and indisputably, according to the universally recognized law of conquest …Footnote 187

For Witbooi, the laws of war also seem to address the right to wage war. A reference to categories of just war shines through when Witbooi claims that he bears no responsibility for the conflict with the Veldschoendragers:

Dr. Hahn [head of missionary] is well acquainted with the law of war and the law of conquest; yet I hear things about him which are beyond me.Footnote 188

In a different situation, Samuel Maharero distinguishes war and peacetime conflicts, counting widespread cattle theft among the latter:Footnote 189

I have received your few words, and have read them, but I cannot quite grasp what you are trying to tell. About your fighting I understood. I don’t know all about your fights, but I do know that you only fought two wars with my father, and that my father won them both.Footnote 190 Your fighting to the west and the east of Okahandja was not warfare but theft.Footnote 191

In his reply, Witbooi again invokes the distinction between just and unjust war, grouping into the latter category the traumatic Okahandja massacre of 23 August 1880, in which the Herero – in revenge for the Windhoek massacre committed by Jonker Afrikaner exactly 30 years earlier –had indiscriminately murdered the Nama-Orlam lodging in Okahandja:

But your father did kill me on that day in one respect, which I alone know of: I asked the Herero that day what I had done that I must die, and they replied: You have not committed any particular crime, but you shall die today because you are Red, and on that day that was the crime of all Red people who found themselves in Hereroland. So, at one time your father did kill many innocent souls cold-bloodedly, in fearsome and inhuman ways.Footnote 192

Witbooi deduces from this a right to wage war.Footnote 193 He also repeatedly invokes self-defence.Footnote 194

Finally, Witbooi’s demand for Captain Curt von François to lift the weapons restrictions is interesting:

But I look at the matter of arms like this: guns and ammunition should be free commodities for everyone. You cannot appropriate them to yourselves alone, and regulate their sale and distribution with sanctions.Footnote 195

He subsequently compares access to weapons with the right to access water. As obvious as the political motivation behind this request may be, it reveals a different understanding of fairness in armed conflicts. For Witbooi, it is not the quantity or quality of weapons, but tactics, knowledge and cunningness that are supposed to decide on victory or defeat. This is exactly how Witbooi waged war.

Hence, Witbooi and other captains had a shared sense that certain rules were applicable to wars between different polities. These rules oscillate between politics and moral-religious reasons, between interests and principle – but so did colonial international law. They rule out massacres of the civilian population and allow loot under certain conditions, but apparently only for just wars. Whether the 1904–1907 war was just according to these terms or not, there is enough evidence to cast doubt on the universality and primacy of colonial international law in these matters. Others deemed different rules applicable to inter-polity relations, and it is entirely possible that Germany violated these rules.

5. From ambiguity to solidarity

I hope that the foregoing sections have provided sufficient support for the ambiguity thesis of colonial international law. The ambiguity is two-fold. Internally, the excessive legalism characterizing German colonialism in the late nineteenth century was unable to justify blatant injustice. Externally, competing visions of inter-polity law undermine colonial international law’s justificatory narrative based on its claim to primacy and universality. If one follows the ambiguity thesis, the conventional view that ‘it was all legal’ collapses. Ambiguity is the result of deep contradictions and anxieties within colonial societies. The ambiguity thesis highlights the crisis of European identity that resulted from colonialism – and that may have contributed to European expansion in the first place, besides the obvious economic interests behind colonialism, as it provided a valve for conflicts unresolved at home.

The ambiguity thesis also has implications for contemporary European identity. ‘It was all legal’ is a justificatory narrative that instills a sense of self-righteousness, particularly in combination with the proviso that colonialism and the related atrocities were a moral wrong. This vindicates the European point of view in every respect: in respect of the past – because anything happening back then was supposedly legal; but also in respect of the present – because Europe’s moral catharsis and ability to overcome a treacherous, though legal, past in a selfless act of Vergangenheitsbewältigung seemingly confirms its civilizational superiority. By juxtaposing past law with contemporary morality, amnesia goes full circle. By contrast, emphasizing the ambiguity of colonial international law suggests that the recognition of colonial injustice is perhaps not as selfless and unwarranted as some make us believe, and that former imperial societies still have a long way to go to come to terms with their colonial past.