Classic Maya rulers presented themselves as divine pivots. People revolved around them, drawn in and guided by their authority. The hieroglyphic texts present fully formed and unchanging royal personas. Instead of accepting this narrative, we ask how Classic Maya naturalized sociopolitical roles and institutions.

The formation of polities offers the opportunity to study subjectification; that is, the process of creating and eventually submitting to a political authority. From our relational perspective, leaders build their authority. Materialized narratives allow them to set themselves apart from competitors and attract non-elites. Although elites claim absolute power, we argue that rhetoric should not be mistaken for reality. Subjectification requires non-elites to recognize the emerging political hierarchy and its leaders. It calls attention to co-constitutive processes involving collaboration and negotiation.

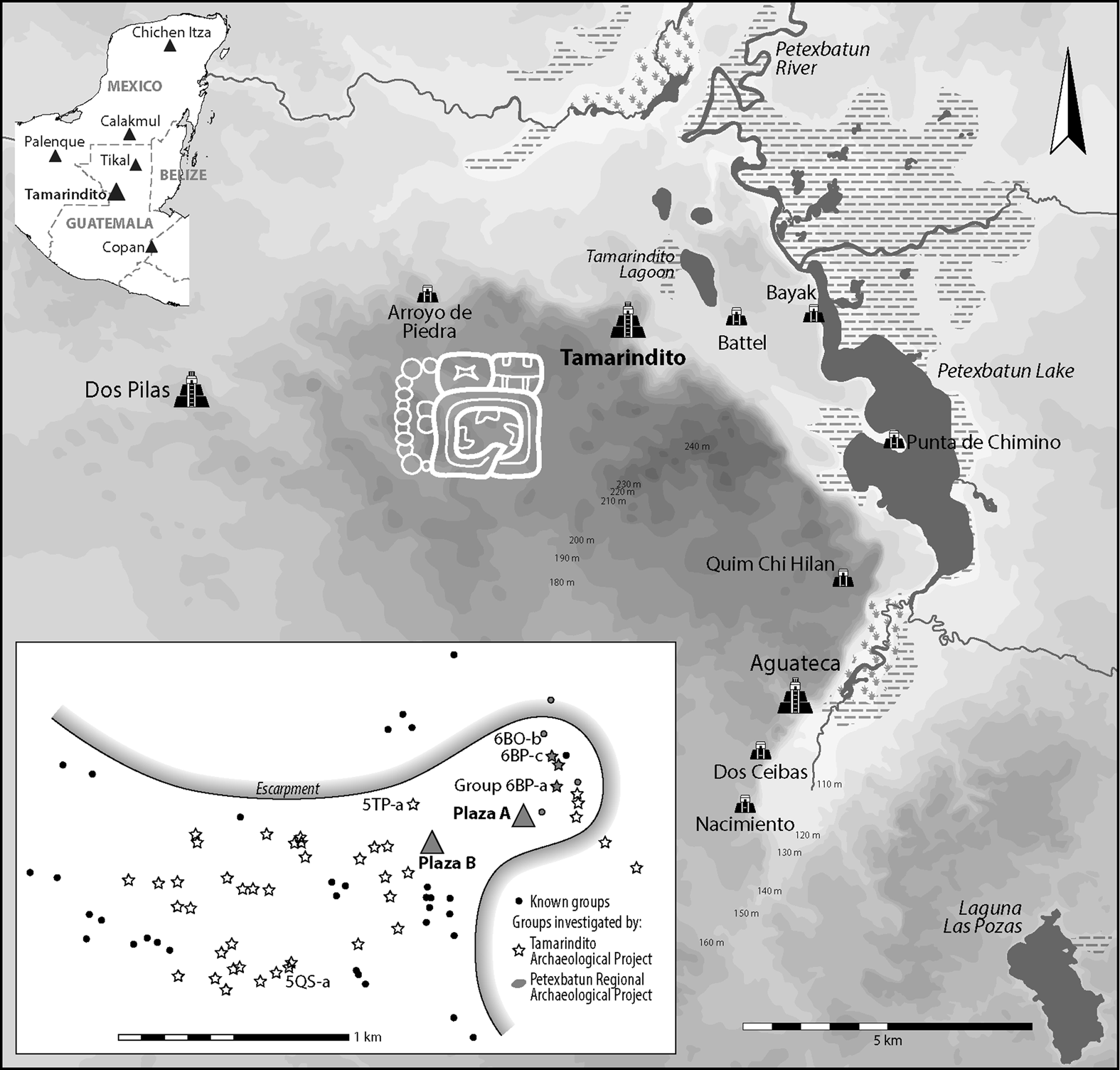

Our case study is the Foliated Scroll polity in the south-central Maya Lowlands; its capital was the site of Tamarindito in Guatemala (Figure 1). The polity's origins have been linked to environmental changes and elite intervention. At the end of the Preclassic (around AD 350 in the Petexbatun region), environmental degradation is assumed to have forced people to move from riverine settlements to Tamarindito where they encountered deep virgin soils (Dunning et al. Reference Dunning, Rue, Beach, Demarest, Inomata, Palka and Escobedo Ayala1991; O'Mansky and Dunning Reference O'Mansky, Dunning, Demarest, Rice and Rice2004). Foliated Scroll rulers made the site their capital at least as early as the fifth century AD and expanded their reign from there across the Petexbatun region. The Petexbatun Regional Archaeological Project (PRAP) and the Tamarindito Archaeological Project (TAP) investigated Tamarindito extensively. Their findings suggest that earlier models fail to fully explain the site's emergence. Instead, we propose a centuries-long process of subjectification during which Foliated Scroll rulers built their authority while non-elites subjectified themselves slowly.

Figure 1. The royal Maya capital of Tamarindito in the Petexbatun region; the emblem glyph of the Foliated Scroll dynasty is shown between Arroyo de Piedra and Tamarindito. Insets: (upper left), Tamarindito's location in the Maya Lowlands; (lower left), schematic site map identifying known residential groups and those investigated by PRAP and TAP; groups with Early Classic ceramics are labeled (all figures by Markus Eberl except where noted).

Forming Polities and Subjectivities

The anthropology of becoming locates people in immanent fields (Biehl and Locke Reference Biehl and Locke2010). By studying what people do and might do, scholars reveal forces that circumscribe actions while leaving room for potentiality. This future-oriented perspective challenges archaeologists to question hindsight's certainty. Recent archaeological discussions of polities exemplify the shift from a preordained rise, peak, and fall to experiments, fragility, and alternative pathways (Fargher and Heredia Espinoza Reference Fargher and Heredia Espinoza2016; McAnany Reference McAnany and Yoffee2019; Yoffee Reference Yoffee2019). As they form a polity, people create novel sociopolitical roles, relations, and institutions. The outcomes—encapsulated in terms like “citizen” and “state”—conceal a process of becoming and changing subjectivities.

We define subjectivity as the interweaving of people's inner lives with institutions, knowledge structures, and symbolic forms (based on Biehl et al. Reference Biehl, Good, Kleinman, Biehl, Good and Kleinman2007:5–6). This definition harks back to the Middle English subject as a person who “owes obedience.” As social beings, individuals act within mutually constituted systems of meaning-giving relations. They restructure these relations in emerging polities by beginning to share a political identity (Paynter Reference Paynter1989:383) and becoming members of what Durkheim (Reference Durkheim1965:62) calls a moral community (Davenport and Golden Reference Davenport, Golden, Kurnick and Baron2016; Houston et al. Reference Houston, Escobedo, Child, Golden, Muñoz and Smith2003).

Polity formation involves subjectification. People create a political hierarchy and eventually see themselves as subjects to an authority. We agree with Smith (Reference Smith2011:416) that authority is “not a substantive quality to be possessed but rather a condition of political interactions, embedded in the ‘actualities of relations.’” Correspondingly, we speak of interweaving to foreground the co-constitution of hierarchical political relations. Leaders in certain kinds of political structures project absolute power and present themselves as uniquely endowed individuals. Traditionally, studies focused on them as creators of polities. Segmentary state, theater state, and galactic polity models revolve literally and metaphorically around the ruler (Geertz Reference Geertz1980; Southall Reference Southall1988; Tambiah Reference Tambiah1977). Noble households often seed a settlement and form its core (Fox Reference Fox1977; Sanders and Webster Reference Sanders and Webster1988:524; Weber Reference Weber1958:66–67).

Royal activities and monuments have been seen as representing the entire polity (Granet Reference Granet1934; Wheatley Reference Wheatley1971). In recent years, scholars have used the concepts of cooperation, collaboration, and collective action to conceptualize the previously neglected or implicit contributions of households, lineages, and other social groups (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2008, Reference Blanton and Fargher2016; Carballo and Feinman Reference Carballo and Feinman2016; Fargher and Heredia Espinoza Reference Fargher and Heredia Espinoza2016; Halperin Reference Halperin2017; Jennings and Earle Reference Jennings and Earle2016). Feinman and Carballo (Reference Feinman and Carballo2018) debate the sustainability of different modes of governance that vary between authoritarian and collective. Polity formation rests on leaders negotiating and building alliances while non-elites engage, avoid, and resist them (Eberl Reference Eberl2017:92–95; Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Bustamante and Levine2001; Schortman et al. Reference Schortman, Urban and Ausec2001; Scott Reference Scott1985).

The creation of polities is future oriented. People envision a new sociopolitical organization and persuade others to join. Their discourses are not second-order representations but “practices that systematically form the objects of which they speak” (Foucault Reference Foucault and Sheridan Smith1972:49). Elites play a privileged role: power allows them to establish totalizing discourses and marginalize alternatives (Asad Reference Asad1993). However, elite discourses are not simply confining subjectivities, as Foucault implies. Deleuze and Guattari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1986) understand them as immanent fields that enable potential actions. We argue that this forward-looking perspective characterizes actors in emerging polities. Their discourses do not determine but outline desired political structures and may fail or have unforeseen outcomes.

Material forms are inherent in immanent fields. We differ in this respect from other scholars who differentiate discourse from matter and see the latter mediating the former (Coole and Frost Reference Coole, Frost, Coole and Frost2010:26). For us, people's situatedness forms the lay of the land and facilitates relations not between but along (Ingold Reference Ingold2010:12): places and things form vectors of subjectification (Kosiba Reference Kosiba2015). Leaders materialize the sociopolitical persona in their public persona and behavior. In medieval Europe, officeholders merge with their office (Kantorowicz Reference Kantorowicz1957). The medieval Western concept of the body politic and comparable concepts elsewhere (Houston and Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1996) are not simply gestures but are critical to the implementation of polities.

The Royal Capital of Tamarindito

Topographically, Tamarindito is one of the most prominent sites in the south-central Maya Lowlands (Figure 1). It occupies the elbow of the L-shaped escarpment that rises up to 70 m above the surroundings. Plaza A, a leveled hilltop and the royal seat during the Early Classic (AD 350–600), marks the elbow's joint and offers imposing views to the north and east (Figures 2 and 4). It offers limited space, however. Late Classic (AD 600–830) rulers focused on Plaza B 400 m to the southwest. Residential groups clustered to the east of Plaza A and to the west and southwest of Plaza B. A few residential groups spread from the foot of the escarpment toward the Tamarindito Lagoon and the site of Battel (O'Mansky Reference O'Mansky, Demarest, Escobedo and O'Mansky1996; O'Mansky and Demarest Reference O'Mansky, Demarest, Demarest, Valdés and Escobedo1994; O'Mansky et al. Reference O'Mansky, Joshua Hinson, Wheat, Sunahara, Demarest, Valdés and Escobedo1994; Van Tuerenhout et al. Reference Van Tuerenhout, Hope Henderson, Wheat, Valdés, Foias, Inomata, Escobedo and Demarest1993).

Figure 2. Tamarindito's Plaza A and its surrounding area (maps of Groups 6BO-b, 6BP-e, 6BP-g, and 6BQ-b after Chinchilla Reference Chinchilla, Valdés, Foias, Inomata, Escobedo and Demarest1993:115). Insets: (upper left), Stela 5 (after Houston Reference Houston1993:77); (lower right), Stela 3 (after Lehmann and Lehmann Reference Lehmann and Lehmann1968: Figure 103).

After Tamarindito's discovery in 1958, scholars documented its hieroglyphic inscriptions (Greene Robertson et al. Reference Greene Robertson, Rands and Graham1972; Houston Reference Houston1987, Reference Houston1993). In 1984, Stephen Houston (Reference Houston1993:50) and his team created the first map of Tamarindito's Plazas A and B. During the 1990s, PRAP extended the map's coverage and started excavations, particularly in the center (Demarest Reference Demarest2006:121–122; Valdés Reference Valdés1997). All Early Classic inscriptions come from Plaza A, and the archaeological studies documented substantial building activity there from this and later time periods. Plaza B became prominent during the Late Classic.

Two of the authors codirected the Tamarindito Archaeological Project (TAP) since 2009 (Eberl and Vela González, eds. Reference Eberl and González2016). Gronemeyer (Reference Gronemeyer2013) documented all the hieroglyphic inscriptions and summarized the history of the site and of its royal dynasty. Our archaeological survey produced a topographic map that extends over 1 km2. Illegal deforestation of most of the site allowed us to identify and document even small and low archaeological features. In seven field seasons, we explored Plaza B, a nonresidential group, and 43 non-elite residential groups through 204 test pits, the cleaning of 13 looted buildings, and four extensive excavations. After documenting looted buildings, we refilled them. About 80% of Tamarindito has been surveyed, and we estimate that our investigations cover two-thirds of all residential groups. PRAP and the current project studied all residential groups near Plaza A, except one.Footnote 1

Two explanations have been offered for the emergence of Tamarindito and the Foliated Scroll polity. First, scholars observed that Petexbatun settlements concentrated along rivers, lagoons, and lakes during the Preclassic (Dunning et al. Reference Dunning, Rue, Beach, Demarest, Inomata, Palka and Escobedo Ayala1991; O'Mansky and Dunning Reference O'Mansky, Dunning, Demarest, Rice and Rice2004). Overuse degraded these riverine environments, and at the end of the Late Preclassic, people abandoned their settlements. It was proposed that they moved to Tamarindito, the most prominent Early Classic settlement in the region where virgin soils, terraces, and other forms of intensive agriculture assured their survival. Urbanization would then have led to the formation of a polity (see Jennings and Earle Reference Jennings and Earle2016). Second, Tamarindito served as the capital of the first Classic period polity in the Petexbatun region (Houston Reference Houston1993). Its divine rulers identified themselves as k'uhul ajawtaak or “divine lords” over the foliated scroll (inset in Figure 1; see the later discussion of the Foliated Scroll moniker). Hieroglyphic texts detail Tamarindito’s history from the fifth through eighth centuries AD. Together with the archaeological record, they allow us to ask which roles were played by divine rulers and non-elites in establishing Tamarindito and the Foliated Scroll polity.

Creating Royal Authority

In the Maya Lowlands, divine rulers and rulers project fully formed subjectivities. They portray themselves as time-honored authorities with invariant roles and individuals as institutions. For example, dynasties often trace their origins to a deep and mythological past (Grube Reference Grube1988; Schele Reference Schele1992; Stuart Reference Stuart, Bell, Canuto and Sharer2004). Titles like ajaw allow nobles to claim seemingly unchanging roles. Elites also institutionalize themselves through impersonation. In one case, the noble Nabnal K'inich conflates the person with the office by calling himself the “personification” (u b'aah-ahnul) of his house (Supplemental Figure 1). These statements need to be critically examined, however. The title for k'uhul ajaw or “divine lord” emerges, for example, only during the Late Classic (Martin Reference Martin2020:102–142). We argue that individuals formed subjectivities narratively in Classic Maya society. This dynamic process is evident during polity formation when elites claim authority.

In a similar fashion as their peers, Foliated Scroll rulers portray themselves as having been in charge since time immemorial and as being part of an institution that transcends individual lives. They kept track of their royal dynasty by noting their position and that of their dynasty's founder. Although some of these founders like Tikal's Yax Ehb’ Xook were historical people, others go back thousands, if not millions, of years and are fused with timeless supernatural beings (Eberl Reference Eberl and Braswell2014b). The Foliated Scroll's founder belongs in the latter category, appearing at the beginning of time or 3114 BC in the Western calendar (Houston Reference Houston1993:100–101). A Classic ruler wears a face mask presumably with the hieroglyphic name of his dynasty's founder on Stela 3 (lower-right inset in Figure 2). In this way, the king claims a past beyond the reach of normal mortals. He embodies his ancestor and, in a process of subjectification, takes on a predefined identity. Fittingly, the ruler is unnamed and could be any one of a long line of kings. With his ancestor as template, he is the Foliated Scroll ruler. He and other Foliated Scroll rulers project continuity.

On Hieroglyphic Stairway 3, an early eighth-century ruler claims to be the twenty-fifth descendant of the founder. However, only 12 rulers are attested so far (Gronemeyer Reference Gronemeyer2013:8–27). Assuming an average reign to be between 22.5 and 30.6 years (Grube Reference Grube, Blos and Cucina2006:154; Martin Reference Martin, Kerr and Kerr1997:853–854), 24 predecessors would push the Foliated Scroll dynasty's beginning to the Preclassic (the Foliated Scroll emblem refers to the Petexbatun region, as we discuss later; therefore, its rulers did not establish their dynasty elsewhere in Preclassic times and then move to the Petexbatun region). In intertwining narratives, Foliated Scroll rulers consecrate themselves with a mythological ancestor, see themselves as an institution, and claim to have reigned for many centuries.

Overburden has often made it difficult to study the foundations of royal dynasties archaeologically in the Maya Lowlands (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Muñoz and Vásquez2008; Sharer et al. Reference Sharer, Traxler, Sedat, Bell, Canuto and Powell1999). Extensive investigations at Tamarindito, however, allow us to evaluate the royal narratives. In the Petexbatun region, Preclassic settlements existed at Aguateca, Bayak, Dos Ceibas, and Punta de Chimino (Figure 1; Bachand Reference Bachand2006; Eberl Reference Eberl2014a:179–215; Eberl et al. Reference Eberl, de los Ángeles Corado, Vela González, Inomata, Triadan, Ruiz and Seijas2009; Foias Reference Foias1996:262; Inomata Reference Inomata1995:274–281; O'Mansky Reference O'Mansky, Demarest, Escobedo and O'Mansky1996; O'Mansky et al. Reference O'Mansky, Joshua Hinson, Wheat, Sunahara, Demarest, Valdés and Escobedo1994; Van Tuerenhout et al. Reference Van Tuerenhout, Hope Henderson, Wheat, Valdés, Foias, Inomata, Escobedo and Demarest1993). They were hamlets mostly near rivers and lakes. Tamarindito's ceramic assemblage dates from the Late Preclassic to the Postclassic (300 BC to about AD 1300; Eberl et al. Reference Eberl, Schwendener, González, Eberl and González2016:147–153; Foias and Bishop Reference Foias and Bishop2013:77). PRAP excavated a few Faisan Chicanel ceramics at Plaza A, Plaza B, and residential groups near Plaza A (Foias and Bishop Reference Foias and Bishop2013:77) but encountered no Preclassic constructions. TAP investigations complement earlier studies. Most of our ceramic assemblage comes from nonroyal residential groups and has a striking temporal distribution (Table 1). More than 98% of all ceramic sherds date to the Late Classic, and Late Preclassic sherds account for less than 0.5% of all datable sherds. Faisan Chicanel ceramics are not only rare but also are scattered indiscriminately across the site and mix with later materials. We found no Preclassic buildings or construction levels (Eberl and Vela González Reference Eberl, González, Eberl and González2016:162–163). The comprehensive investigations indicate that Tamarindito lacks a Preclassic predecessor.

Table 1. Chronological Distribution of the Ceramic Assemblage Excavated by the Tamarindito Archaeological Project.

Note: The investigations covered 43 non-elite residential groups, a possible lookout, and Plaza B.

a “Other” sherds include temporally disputed types and sherds classified only to the ware level.

Early Classic Genesis of the Foliated Scroll Polity

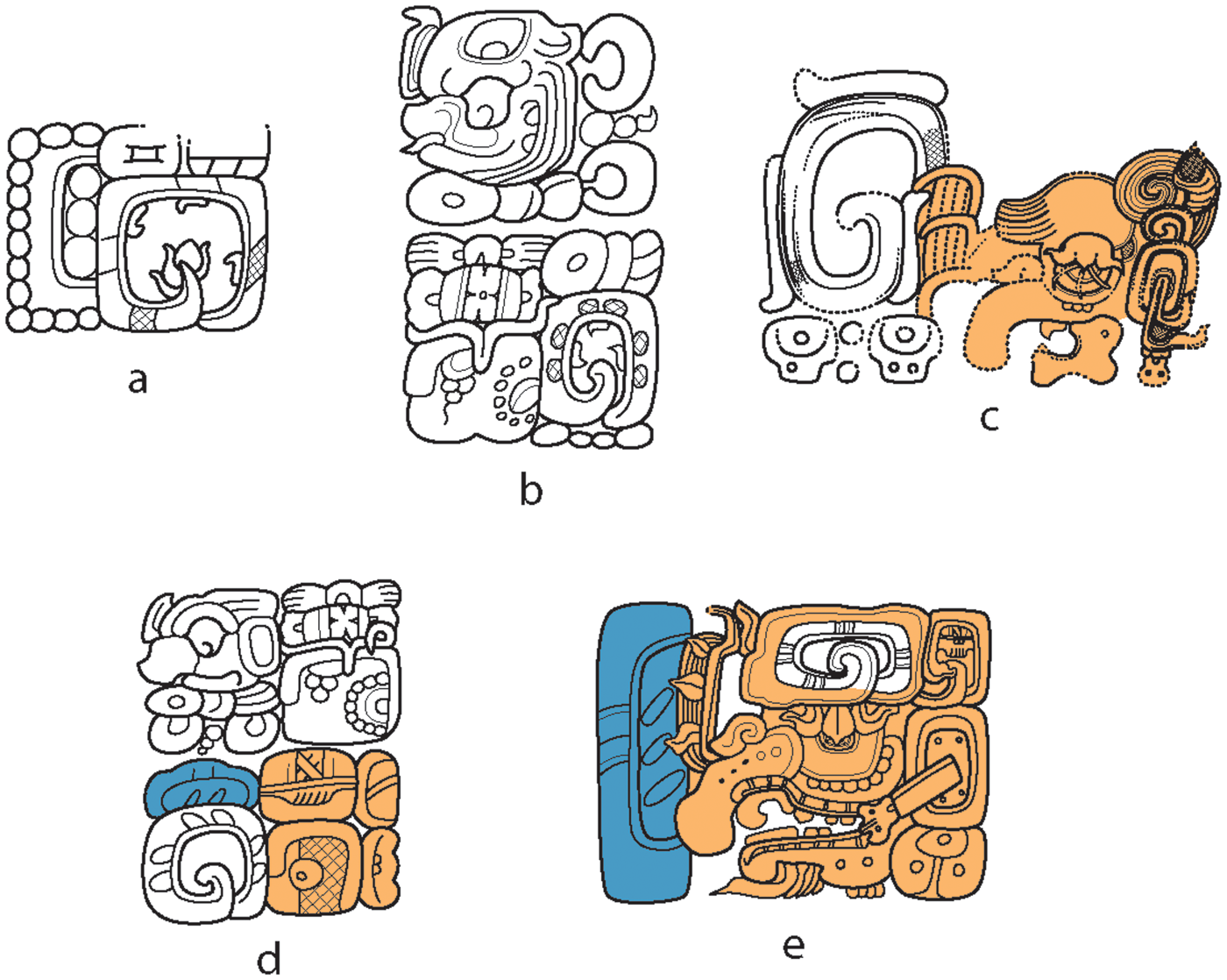

The first historically attested Foliated Scroll ruler was born in AD 472 (Houston Reference Houston1993). In the following decades, Tamarindito and Arroyo de Piedra became the dynasty's capitals (Figure 1; Valdés Reference Valdés1997; for Arroyo de Piedra, see Escobedo Ayala Reference Escobedo Ayala1997).Footnote 2 Inscribed monuments proclaim the official history. The foliated scroll emblem of the royal dynasty consists of glyph T856—sometimes suffixed with the syllable la—and remains undeciphered (on Arroyo de Piedra Stela 6, the foliated scroll is called nal, or “place”; the la may phonetically complement the latter and not the foliated scroll glyph). An inscription shows the foliated scroll as the curly stalk of a water lily (Figure 3a; also Buechler Reference Buechler2012:533). These vegetal elements set the foliated scroll emblem apart from scrolls at Altun Ha and other sites.

Figure 3. The foliated scroll in selected hieroglyphic texts and art (orange background highlights chan ch'een “sky (and) cave” and green-blue yax “green-blue, first”; color version available online); (a) k'uhul “foliated scroll” ajaw from Tamarindito Miscellaneous Text 2, glyph B (redrawn from Gronemeyer Reference Gronemeyer2013:95); (b) “it happened at Aguateca in the ‘foliated scroll’” from Aguateca Stela 1, glyphs D9 and D10 (redrawn from Graham Reference Graham1967:4); (c) “foliated scroll” chan ch'een from Arroyo de Piedra Stela 1 (dated to AD 613); (d) yax “foliated scroll” chan ch'een from Aguateca Stela 2, glyphs G6 and G7 (redrawn from Graham Reference Graham1967:10); (e) yax “foliated scroll” chan ch'een from Tamarindito Stela 3 (redrawn from Lehmann and Lehmann Reference Lehmann and Lehmann1968: Figure 103).

Unlike many dynasty-specific emblem glyphs, the foliated scroll references locale (see also Gronemeyer Reference Gronemeyer and Behrens2016). On Aguateca Stela 1, a period ending was celebrated in AD 741 “at the great-sun split mountain [the Classic Maya name for Aguateca] in the foliated scroll” (Figure 3b; also Figure 3d). By this time, Tamarindito's rulers had ceded control over Aguateca to Dos Pilas's mutul dynasty. Therefore, the foliated scroll is best explained as a regional place name that refers to the Petexbatun region and includes Aguateca and Punta de Chimino (Buechler Reference Buechler2012:21; Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine2013:66).

Maya kingdoms like the Foliated Scroll polity did not exist in the abstract but materialized in specific places and people: royal actions are grounded. The phrase u kabjiiy refers to events that a Maya ruler directed or oversaw. It likely means the tilling of fields and links the ruler's statecraft to a farmer's agriculture (Houston and Inomata Reference Houston and Inomata2009:145; see Jackson Reference Jackson2013). In hieroglyphic texts, royal dynasties and arguably polities are called chan ch'een or “sky (and) cave” (Hull Reference Hull, Hull and Carrasco2012:107–108; Stuart and Houston Reference Stuart and Houston1994:12–13). As in the altepetl in Highland Mexico, chan ch'een refers to an institution in both abstract and graspable ways. For example, successful wars eradicate the ch'een of a Maya kingdom, destroy the statues of its patron gods, and crush the bones of their enemies’ ancestors (Brady Reference Brady1997; Eberl et al. Reference Eberl, Gronemeyer and González2019:669–970; Martin Reference Martin2020). The foliated scroll is one of these chan ch'een “sky-caves” (Figures 3c and 3d). Tamarindito's Plaza A was likely the or one of the landmarks that embodied it.

Foliated Scroll rulers saw themselves as hegemons. On Stela 3 and elsewhere, they had the glyph yax carved before the foliated scroll toponym (Figures 3d and 3e). Yax means “green-blue” and, more broadly, “fresh, new” (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Claudia Brittenham, Tokovinine and Warinner2009:40–42). As the color of jade, it denotes precious objects. Ancient Maya qualified water with yax to highlight its life-giving importance. The second set of meanings is apparent in phrases like calling each of humankind's ancestors yax winik or “new person.” Yax is also the color of the center around which the world revolves. Since at least AD 573 when they call the foliated scroll yax on Arroyo de Piedra Stela 6, rulers ascribed temporal and spatial prominence to their polity. They expressed this aspiration not only in their emblem glyph but also visually. Erected in front of or on Plaza A's pyramid (Structure 6AQ-2), Stela 3 shows a Late Classic ruler standing on the foliated scroll (Figure 3e; lower-right inset in Figure 2). Perched on the highest point in the region, the stela manifests the ruler's claim over the region at large. The Lowlands are literally at his feet.

Foliated Scroll rulers stress their uniqueness, but their political reality was more complex. The “yax foliated scroll” statement replicates the self-identification of Tikal or ancient mutul as yax mutul (Martin Reference Martin2020:403n12). This link to the powerful Early Classic center seems no coincidence. The Lady of Tikal, an early sixth-century ruler, possibly supervised a Tamarindito ruler during the period-ending celebrations in AD 534 (Gronemeyer Reference Gronemeyer2013:12; Martin Reference Martin2020:245). Early Foliated Scroll rulers may have been acting under Tikal's hegemony. They also started to expand beyond their capitals only in the mid-fifth century; that is, several generations after their dynasty's foundation (Eberl Reference Eberl2014a:35–38; Houston Reference Houston1993). The earliest evidence comes from Punta de Chimino; a Foliated Scroll ruler gifted an inscribed Early Classic ceramic bowl to a Punta de Chimino noble. This likely took place during the latter part of the sixth century because this site's center was abandoned until at least the AD 530s (Bachand Reference Bachand2006, Reference Bachand2010). Foliated Scroll rulers then expanded their reign farther south. For example, one ruler celebrated a period-ending ceremony at Aguateca in AD 613. They governed the then-settled parts of the Petexbatun region only by the beginning of the Late Classic.

Materializing a Divine Pivot

The Foliated Scroll rulers constituted themselves and their polity in Tamarindito's Plaza A. There they built their first pyramid, palace, and plaza during the Early Classic (Figure 2). Deep soils nearby promised sustainable and bountiful harvests. Yet, we argue that the rulers’ choice reflects more than only a favorable environmental setting. Over the course of the Early Classic, rulers made Plaza A their place.

Because the bedrock was uneven, rulers first had Plaza A's hill leveled. Their workers then built gravel or stucco floors in front of the palace and the pyramid. At some time later, during the Early Classic, they resurfaced the plaza and extended it across the western part of the hill (Figure 4). They also added a low platform in front of the pyramid (Foias Reference Foias, Valdés, Foias, Inomata, Escobedo and Demarest1993:101). The plaza covered the entire hill only during the Late Classic. The pyramid (Structure 6AQ-2) dominates the southern part of Plaza A. The association of the Early Classic Stela 5 with Pyramid 6AQ-2 or a predecessor suggests that the Early Classic version of Plaza A looked like its final version, with a palace in the north, a central plaza, and a pyramid in the south (the pyramid was not excavated due to extensive looting). Three buildings—Structures 6BP-29, 6AP-3, and 6AP-4—and both the West and East Courts are attested for the Early Classic palace (Foias Reference Foias, Valdés, Foias, Inomata, Escobedo and Demarest1993, Reference Foias, Demarest, Valdés and Escobedo1994). The best-studied example is Structure 6BP-29 (previously known as Structure 13; inset in Figure 4). Its Early Classic predecessor was a platform that rose 1 m above the East Court plaza.

Figure 4. Plaza A during the later part of the Early Classic (only the northern and central part of Plaza A are shown). Inset, construction sequence of Structure 6BP-29 (previously known as Structure 13; north profile modified after Valdés Reference Valdés1997:324).

As part of the site-wide survey, we remapped Plaza A and calculated construction volumes and plaza areas. Plaza A's buildings and plaza have a total construction volume between 8,200 and 11,000 m3 and represent 17,000–23,000 person-days of labor.Footnote 3 Almost 80% of the labor effort involved quarrying limestone, roughly 10% went to transporting the limestone, and another 10% to the construction of platform and structure fill. These estimates do not account for manufacturing veneer stones and dressing façades. Plaza A was smaller during the Early Classic before later additions to the palace, so less labor would have been needed for its Early Classic version (Valdés Reference Valdés1997:322–325). Nonetheless, the rough estimate shows that the scale of construction was limited. The combined labor effort equals about 579–781 person-years, based on the assumption that preindustrial farmers can set one month annually aside for nonagricultural work (Lewis Reference Lewis1951:156). Twenty-three to 31 workers could have built Plaza A in 25 years.

The construction history of the plaza in Plaza A attests to a slow growth that mirrors Tamarindito's settlement history. Antonia Foias (Reference Foias, Valdés, Foias, Inomata, Escobedo and Demarest1993) identified two Early Classic and one Late Classic construction episodes. First, builders smoothed out the hill's surface with a floor that was 0.06–0.11 m thick. Because test pits encountered the floor at different depths, we assume that it covered only parts of the hill, likely forming plazas before the palace and the pyramid. The total volume of 250 m3 represents the labor of at least 530 person-days (this estimate omits the making of lime for the stucco surface). A handful of laborers could have completed this task within a few years. Later during the Early Classic, Plaza A was resurfaced. The construction volume for this second construction episode varied between 750 and 2500 m3 and required a more substantial labor effort: 1,600–5,300 person-days. During the Late Classic, a third construction episode extended the plaza to its final version by adding 660–1,770 m3 of fill requiring 1,420–3,800 person-days of labor.

Plaza A was designed for large crowds. Like large plazas elsewhere, people gathered there to witness their rulers during period-ending ceremonies and other events (Inomata Reference Inomata2006). Its Late Classic version extends more than 3,334 m2 and could hold approximately 3,300 people (estimates range from 926 [at 3.6 m2 per person] to 7,248 people [at 0.46 m2 per person] based on Inomata [Reference Inomata2006:816]). The plaza was smaller during the Early Classic and, after its first extension, provided room for approximately 1,650 people (Figure 4).

Although few buildings studded Tamarindito's Plaza A during the Early Classic, they must have appeared imposing because they formed a ring around an isolated 70 m high natural hill. Springs are at its foot, and cave-like quarries pockmark its sides. These features characterize the flower mountain that figures prominently in the Maya cosmovision. The ancestral couple emerges from a cave in it to establish humankind (Eberl Reference Eberl2017:2, 116; Saturno et al. Reference Saturno, Taube and Stuart2005:14–21; Taube Reference Taube2004). Plaza A resonates with the aspirations of the Foliated Scroll rulers. From there, the Petexbatun region lay at their feet, and thousands of people could gather for their public ceremonies. Rulers transformed Tamarindito's Plaza A into their divine pivot: a seat for a divine dynasty, a place of sustenance, and the center of a regional polity.

Non-elite Subjectification

An emerging polity offers the opportunity to study how people subjectify themselves as they become residents. During the Early Classic, rulers established the Foliated Scroll polity. Their chan ch'een places them in the center of the cosmos and materializes in Tamarindito's Plaza A. Our archaeological investigations allow us to suggest how non-elites responded to the royal grandeur. Although their internal motivations often remain opaque, the non-elite took advantage of the politically fragmented Maya Lowlands and, voting with their feet, decided under whose authority to live (Inomata Reference Inomata, Lohse and Valdez2004). Recent studies link successes or failures of divine rulers to rapidly increasing or falling populations at their capitals (Martin Reference Martin2020:231–333). Settlement histories thus offer a way to reconstruct non-elite subjectification.

In the case of Tamarindito, our evidence points to a very small Early Classic settlement. Corresponding construction levels and buildings were only found in Plaza A, Plaza B, and two nearby residential groups (Groups 6BO-b and 6BP-a; Figure 3). Plaza B's Early Classic construction is limited to a stuccoed floor below the southwest corner of its Late Classic palace (between Structures 5TR-6 and 5TQ-22; Valdés Reference Valdés, Valdés, Foias, Inomata, Escobedo and Demarest1993:90–91). No building is associated with this floor, and Plaza B's Early Classic appearance remains unclear.

Outside the royal center, PRAP detected an Early Classic occupation in Group 6BO-b (previously known as Group Q5-1; Valdés et al. Reference Valdés, Monterroso, Cabrera, Demarest, Valdés and Escobedo Ayala1994). All visible buildings date to the Late Classic (Valdés et al. Reference Valdés, Monterroso, Cabrera, Demarest, Valdés and Escobedo Ayala1994:116), but the northern building may have had an Early Classic predecessor (Valdés et al. Reference Valdés, Monterroso, Cabrera, Demarest, Valdés and Escobedo Ayala1994:109). Foias and Bishop (Reference Foias and Bishop2013:112n2) identified Early Classic ceramic deposits in three additional buildings and the plaza. It is unclear, however, whether these deposits correspond to Early Classic construction levels.

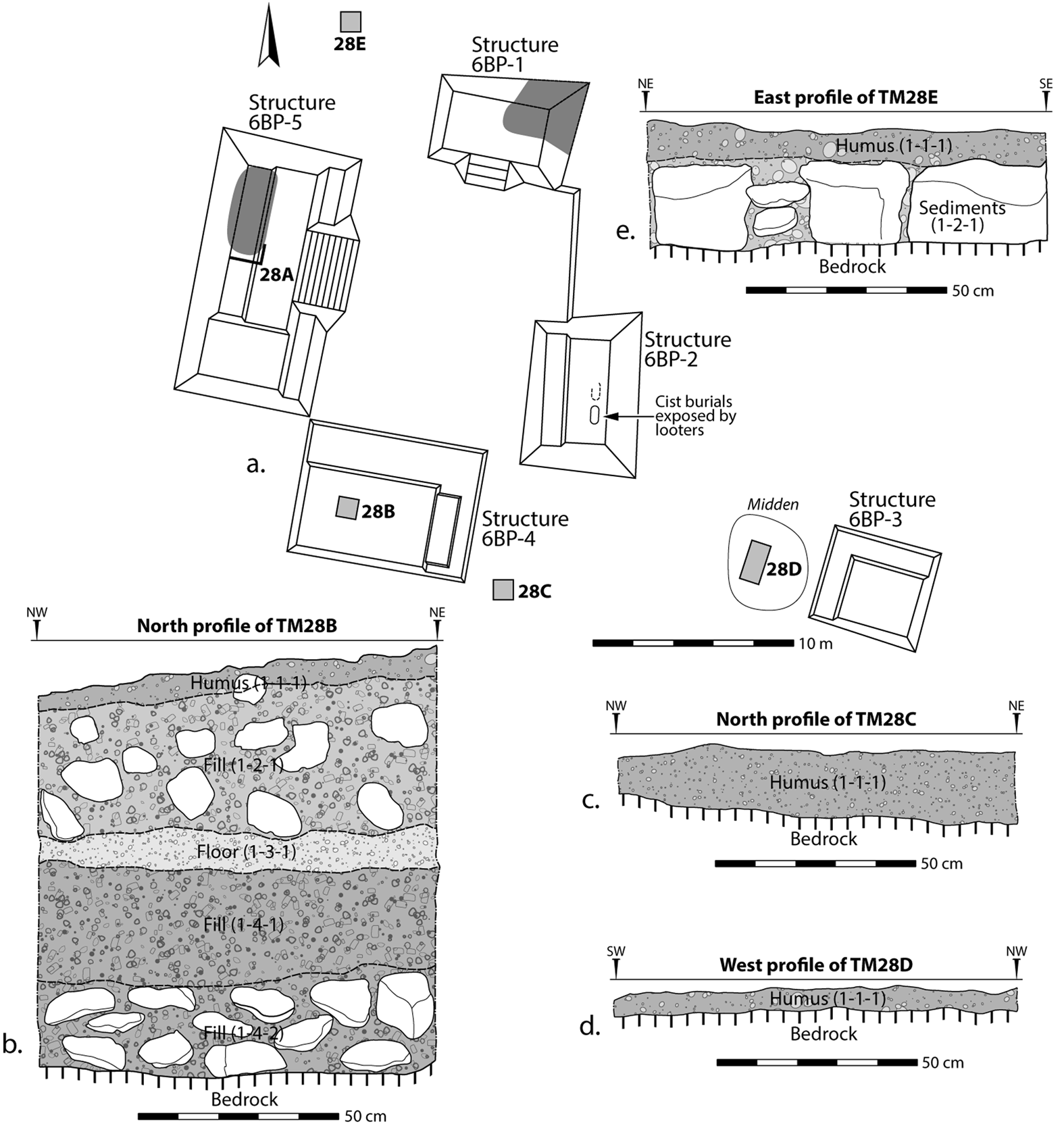

Group 6BP-a is less than 200 m east of Plaza A (Supplemental Text 1). Four buildings group around a leveled plaza, with a fifth building off to the southeast (Figure 5). We cleaned the looter's pit into Structure 6BP-5 and excavated it down to bedrock to reveal three construction episodes (Figures 6 and 7). The ceramic assemblage dates Floors 1 and 2 to the Late Classic (Supplemental Table 1). The third stucco floor was at a depth of 1.2 m, and its support fill was noticeably more compact than the fills above. The ceramic sherds from Floor 3 and its fill are from Early Classic ceramic groups like Quintal, Balanza, and Dos Arroyos and from Late Preclassic groups like Flor and Iberia. Together with the construction technique, they date Floor 3 to the Early Classic (Supplemental Text 2). Structure 6BP-5 started as a 0.5 m high building. So far, it is the only Early Classic building in Group 6BP-a and may have been an isolated building before the rest of the residential group was added.

Figure 5. Investigations in Tamarindito Group 6BP-a (profile drawings by Claudia Vela González): (a) Map of the group (dark-gray areas mark looter's pits); (b) north profile of the test pit into Structure 6BP-4 (TM28B); (c) north profile of the test pit into midden TM28C; (d) west profile of the test pit into midden TM28D; (e) east profile of the test pit into midden TM28E.

Figure 6. Excavation into Tamarindito Structure 6BP-5 (TM28A): drawing of the east profile with associated ceramic sherds (profile drawing by Claudia Vela González).

Figure 7. Excavation into Tamarindito Structure 6BP-5 (TM28A): photo of the cleared looter's pit (north arrow for scale, not direction).

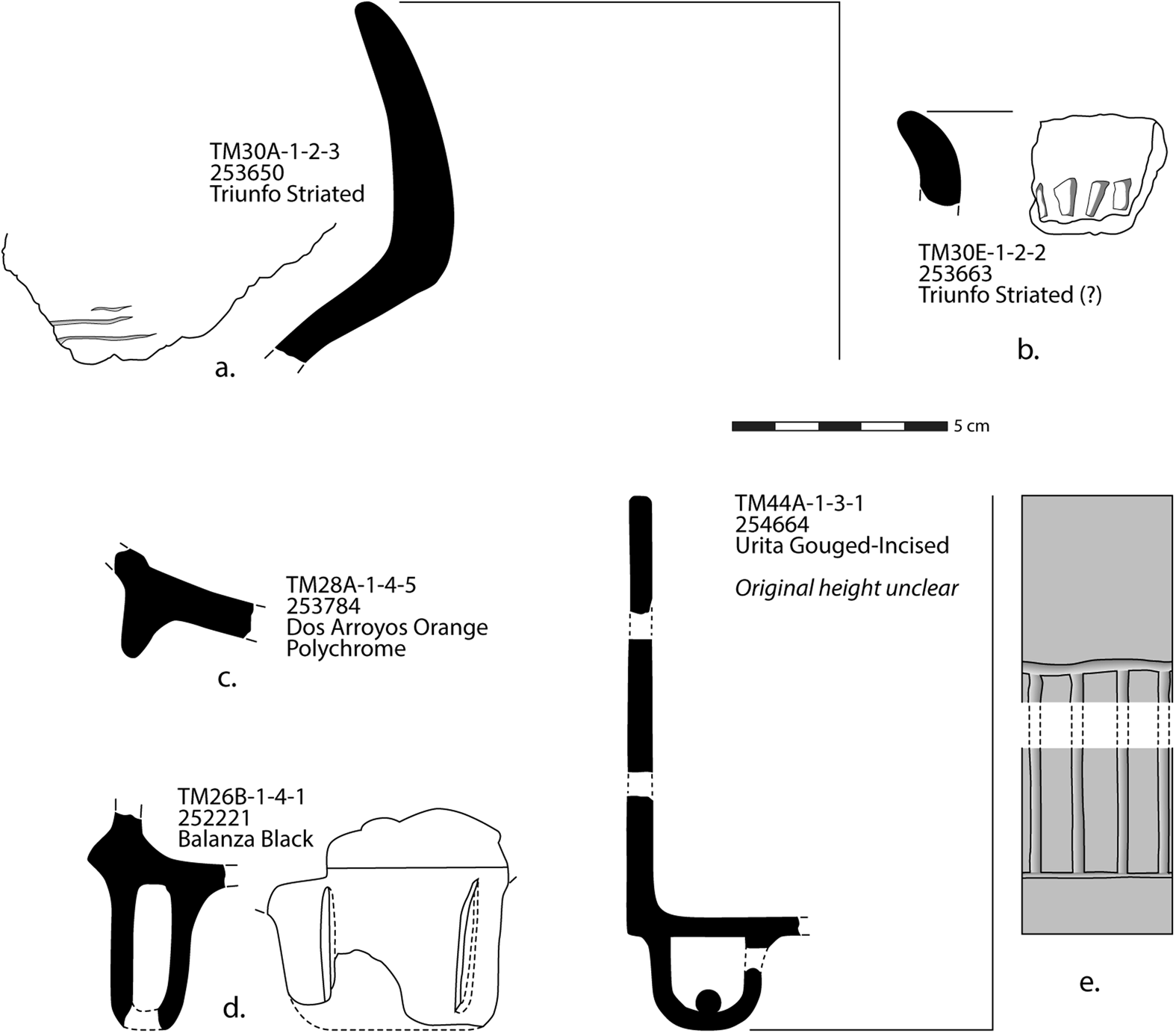

Although Early Classic ceramic sherds are dispersed widely at Tamarindito, they concentrate at and near Plaza A. PRAP encountered Jordan Tzakol ceramic sherds in Plaza A, Plaza B, and Group 6BO-b (Foias and Bishop Reference Foias and Bishop2013:112n2). In our excavations, Early Classic sherds account for less than 1% of all datable sherds (Table 1). About three of four Early Classic sherds are unslipped ceramic types like Quintal Unslipped and Triunfo Striated (Figures 8a and b). Slipped ceramics include Dos Arroyos Orange Polychrome sherds from plates with characteristic Z-shaped flanges (Figure 8c). Several Balanza Black sherds constitute the hollow foot of a cylinder vessel (Figure 8d). The only partially reconstructible Early Classic vessel is an Urita Gouged-Incised cylinder (Figure 8e). Most of the Jordan Tzakol ceramics (83.6%) come from four residential groups east of Plaza A (Groups 6BP-a through -d) and from Group 5PS-d at the southwestern edge of the site (indicated in Figure 1). Except for Groups 6BO-b and 6BP-a, Jordan Tzakol sherds are mixed into Late Classic deposits (Eberl et al. Reference Eberl, Schwendener, González, Eberl and González2016:148; Vela González et al. Reference Vela González, Díaz, Gronemeyer, Levithol, Palomo, Velásquez, Eberl, Eberl and González2016:56).

Figure 8. Early Classic sherds from non-elite residential groups at Tamarindito: (a) Triunfo Striated jar neck from Group 6BP-c; (b) possible Triunfo Striated sherd from Group 6BP-c; (c) Dos Arroyos Orange Polychrome sherd from Group 6BP-a; (d) foot of a Balanza Black cylinder from Group 5QS-a; (e) partially reconstructible Urita Gouged-Incised cylinder from Group 5TP-a.

During the Early Classic, non-elites lived at Tamarindito in small numbers and likely arrived only during the latter part of the Early Classic. The Jordan Tzakol ceramics from non-elite contexts lack early types like Aguila Orange. In Structure 6BP-5, ceramic sherds from Floor 3 were highly eroded (75.6%; Supplemental Table 1): they were likely exposed to the elements for a long time before being reused as construction fill. This suggests that Structure 6BP-5 was first built toward the end of the Early Classic. In contrast, Aguila Orange ceramics date the earliest constructions of Plaza A to the early part of the Early Classic (Foias Reference Foias, Valdés, Foias, Inomata, Escobedo and Demarest1993; Valdés Reference Valdés, Valdés, Foias, Inomata, Escobedo and Demarest1993).

The archaeological investigations at Tamarindito help us reconstruct non-elite subjectification. The royal seat of power in Plaza A was Tamarindito's nucleus around which the later settlement grew (also Houston et al. Reference Houston, Escobedo, Child, Golden, Muñoz and Smith2003:219–226; Kingsley et al. Reference Kingsley, Golden, Scherer and de Franco2012). Urbanization, however, did not initiate the institutionalization of the Foliated Scroll polity (see also Jennings and Earle Reference Jennings and Earle2016). Elites likely founded the site a few generations before the earliest hieroglyphically attested event in AD 472. Rulers presented themselves as hegemons and converted Plaza A into an impressive monumental space. However, their aspirations clashed with reality. Plaza A's crowd capacity exceeded the local and likely even regional population multiple times (for similarly supersized building projects, see Stark and Stoner Reference Stark and Stoner2017:423; Sullivan Reference Sullivan2015:455–456). We show that non-elites started to settle at the site in small numbers and likely not until the later part of the Early Classic. During the fifth and sixth centuries, Tamarindito was a hamlet with possibly only a few dozen inhabitants.

The Making of a Maya Court, Capital, and Polity

The royal capital of Tamarindito sheds light on polity formation in the Maya Lowlands. PRAP and TAP studied approximately two-thirds of all residential groups at Tamarindito and almost every residential group near Plaza A, its Early Classic center. Our comprehensive archaeological and epigraphic investigations show that environmental changes and elite decision making fail to fully explain the site's foundation. Instead, we propose a co-constitutive process of subjectification.

Tamarindito was founded during the Early Classic at a previously uninhabited location. The lack of a Preclassic predecessor sets it apart from the origins of Piedras Negras, Yaxchilan, and Copan where investigations detected Preclassic settlements (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Muñoz and Vásquez2008; Sharer et al. Reference Sharer, Traxler, Sedat, Bell, Canuto and Powell1999). Our investigations show that the Petexbatun region collapsed even more pervasively than previously thought at the end of the Preclassic. This makes Tamarindito an ideal place to study the formation of a polity. We outline distinct stages. Elites founded Tamarindito's royal court perhaps as early as the late fourth century AD. Non-elites then trickled in over the following centuries. The Foliated Scroll polity emerged slowly. Rulers expanded their rule over the Petexbatun region only in the 500s.

Classic Maya rulers, courts, and polities tend to be seen from a Late Classic perspective when they were fully institutionalized. We critique the assumption of fully formed subjects and the resulting difficulty of explaining change. Hieroglyphic texts and art allow us to reconstruct how Maya elites claimed authority. Like their peers, Foliated Scroll rulers presented themselves as timeless. Their self-subjectification is evident on Tamarindito Stela 3, where a ruler impersonates his dynasty's founder and, by remaining nameless, transcends his person to embody an institution. The world revolved around the Foliated Scroll rulers, and they were ever ready to shape the rest of Maya society. However, this is a self-serving narrative. The inscriptions of the Foliated Scroll dynasty were—like other Maya hieroglyphic texts—not meant as objective history (Martin Reference Martin2020:48–64). They tell the origin story of royal elites through their eyes and create the perception of antiquity.

Subjectification rests on recognizing an authority. The Foliated Scroll rulers’ aggrandizing rhetoric makes this seem self-evident, yet our archaeological findings point to an immanent process. During the fifth and early sixth centuries, Foliated Scroll rulers struggled to impose their authority. They could draw only on a limited number of workers to build Plaza A. Outside Tamarindito's center, we found only two Early Classic nonroyal buildings. Tamarindito grew from an Early Classic hamlet to a Late Classic town over the course of two centuries. This slow transition suggests that non-elites did not accept royal hegemony as natural and instead played a more active role than traditionally envisioned in subjectifying themselves.

Acknowledgments

We thank Antonia Foias and Arthur Demarest for information about the Petexbatun Regional Archaeological Project’s work at Tamarindito. They were invaluable for our work and this article. We thank the Edras family for permission to investigate the residential groups on their property. Griselda Pérez and Ana Lucía Arroyave helped with our work permits from Guatemala's IDAEH (in particular, Convenio #20-2010) and permitted the publication of this article. Christian Prager discussed his interpretation of polychrome vase K2914 with us. Bruce Bachand shared his insights into the Foliated Scroll presence at Punta de Chimino. M. Eberl thanks Frauke Sachse, Christina Halperin, and David Lentz for their feedback during a Dumbarton Oaks Midday Dialogue. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive criticism and the editors for their feedback. All of them helped us improve this manuscript.

This work was financially supported by Vanderbilt University.

Data Availability Statement

No original data were used.

Supplemental Material

For supplemental material accompanying this article, https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2022.67.

Supplemental Figure 1. The embodiment of the house of Río Azul noble Nabnal K'inich (detail of Maya polychrome vessel K2914; redrawn from Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, de la Garza and Nalda1998: 290–291).

Supplemental Text 1. Investigating Tamarindito Group 6BP-a.

Supplemental Text 2. Reconstructing Early Classic Tamarindito.

Supplemental Table 1. Ceramic Assemblage from Tamarindito Structure 6BP-5 (TM28A, Unit 1).

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.