Definition and purpose of diversion from custody

Diversion from custody is a policy supporting the removal of people with mental disorders from the criminal justice system to hospital or a suitable community placement where they can receive treatment. There are three principal reasons why such a policy is necessary. First, when those with mental disorders fall through the net of psychiatric services they tend to gravitate towards the criminal justice system; second, the standard of health care provided in prison is, generally speaking, poor; and third, because prison health care centres are not recognised as hospitals for the purposes of the Mental Health Act (MHA) 1983, treatment for mental disorder cannot be given against a prisoner's will unless this can be justified under common law.

Historical context

It is a common misconception that diversion from custody is a relatively recent phenomenon. John Howard clearly thought that the “idiots and lunatics” he observed in the prison system over 200 years ago were not best placed in custody (Box 1). Although mechanisms existed at that time to allow the transfer of some mentally disordered prisoners to asylums, too many escaped from these institutions and so the authorities were generally reluctant to allow it. Broadmoor Hospital was built as one solution to this problem, and when it opened in 1863 its primary function was to help relieve the burden on the prison system of those with mental disorders. The Mental Deficiency Act of 1913, which was implemented and enforced after World War I, provided further resources and statutory powers to divert certain people with mental disorders from the justice system. The Act helped to provide resources by enforcing the setting up of institutions for those with learning disabilities (the ‘mentally deficient’) and it provided powers for courts to commit offenders to such institutions rather than sending them to prison. It also made it possible for sentenced prisoners who fell within the definitions of the Act to be transferred to asylums (Reference Gunn, Robertson and DellGunn et al, 1978).

Box 1. John Howard, on the incarceration of those with mental illness and disabilities

“In some few gaols are confined idiots and lunatics – many of the bridewells are crowded and offensive, because the rooms which were designed for prisoners are occupied by lunatics. The insane, when they are not kept separate, disturb and terrify other prisoners. No care is taken of them, although it is probable that by medicines, and proper regiment, some of them might be restored to their senses, and usefulness in life.”

There have been considerable developments in policy and provision for mentally disordered offenders (MDOs) in the past three decades. The Butler report (Home Office & Department of Health and Social Security, 1975) was instrumental in bringing about the development of medium secure psychiatric facilities; Home Office circular 66/90 (Home Office, 1990) urged the diversion of MDOs from the criminal justice system wherever possible; and the Reed report (Department of Health & Home Office, 1992), which recommended nationwide provision of properly resourced court assessment and diversion schemes, the further development of bail information schemes and public interest case assessment, along with wider provision of specialised bail accommodation, promoted the development of court diversion schemes and led to an increase in the numbers of prisoner transfers to hospital.

Before describing the mechanisms by which those with mental disorders are diverted from custody and the services that facilitate this, it is important to review current levels of psychiatric morbidity in the criminal justice system and consider why there are so many MDOs in custody.

Psychiatric morbidity in custodial populations

Police custody

Robertson et al (1995), who studied people held in custody in London police stations, found that 2.7% of cases had some form of mental illness, with 1.4% demonstrating symptoms of a serious nature. Another study of London police station custody cases by the Revolving Doors Agency (Reference Keyes, Scott and TrumanKeyes et al, 1995) found overt symptoms of mental illness in 1.9% of subjects. In Manchester, Shaw et al (1999) found serious psychiatric disorders among 1.3% of defendants appearing in magistrates' court direct from the community compared with 6.6% among those held in custody overnight.

Prison custody

Recent epidemiological studies show that the prevalence of mental disorder in the prison population is high, that serious mental disorder is disproportionally prevalent and that the highest levels of morbidity are found in remand and women prisoner populations (Reference Gunn, Maden and SwintonGunn et al, 1991; Reference Maden, Taylor and BrookeMaden et al, 1995; Reference Birmingham, Mason and GrubinBirmingham et al, 1996; Reference Singleton, Meltzer and GatwardSingleton et al, 1998). The 1997 survey of psychiatric morbidity among prisoners, which covered all prison establishments in England and Wales (Reference Singleton, Meltzer and GatwardSingleton et al, 1998), found functional psychotic disorders (present within the year prior to interview) in 7% of male sentenced prisoners, 10% of male remand prisoners and 14% of all women prisoners. These findings suggest that there are currently 5000 people in prison with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. Psychiatric comorbidity was also a common finding in the 1997 prison survey: fewer than one in 10 prisoners showed no evidence of mental disorder (psychosis, personality disorder, neurotic disorder or drug- and alcohol-related disorders), more than seven out of 10 had two or more of these disorders and those with functional psychotic disorders were more likely to show evidence of three or four such disorders.

The 1997 national survey did not concern itself with treatment needs. Estimates of this nature are provided by earlier research, which reported lower rates of psychiatric morbidity. Gunn et al (1991), who screened male sentenced prisoners, found psychiatric disorders (including substance misuse diagnoses) in 37% and psychotic disorders in 2%; they judged 23% of this population to have immediate treatment needs, including 3% who required transfer to psychiatric hospital. Maden et al (1995), who carried out a similar point prevalence study on the unconvicted male remand population, found psychiatric disorders in 63% and psychosis in 5%; 55% had immediate treatment needs and 9% were deemed to require transfer to hospital. Birmingham et al (1996) screened male remand prisoners at first reception into prison; 26% were reported to be suffering from mental disorder (excluding substance misuse), with 4% actively acutely psychotic. Thirty per cent of their population was judged to have psychiatric treatment needs (excluding needs related to substance misuse), with 3% requiring immediate transfer to psychiatric hospital.

Why are there so many with mental disorders in custody?

Over the past 20 years the number of psychiatric beds in England and Wales has more than halved as a result of the hospital closure programme, whereas the prison population has continued to rise (Reference GunnGunn, 2000). Failures in community care and a series of homicide inquiries have raised anxieties about care of those with mental illness in the community, and proposed changes to the law relating to people with mental disorders (Home Office & Department of Health, 1999) indicate an increasing emphasis on public safety.

The Penrose hypothesis (Reference PenrosePenrose, 1939) suggests that the changes described above and the current prevalence of mental disorder in the prison population are linked by a complex relationship that centres on changing values in society. Penrose proposed that the approach society adopts towards people who behave in a socially unacceptable manner is largely dictated by prevailing social norms, the political climate and the availability of a suitable route for disposal. Thus, according to this hypothesis, an individual who behaves in a disorderly fashion is more likely to be dealt with by mental health services if such services are well-resourced and hospitalisation is favoured. In contrast, the same individual is more likely to be seen as an offender and sent to prison in a society where resources and statutory provision favour imprisonment.

Penrose also proposed that the proportion of society that ‘requires’ institutional care remains relatively constant over time, implying that if people with mental disorder cannot access hospital beds they will gravitate towards prison.

Although Penrose based his hypothesis on a study of criminal statistics and mental hospital populations across 14 European countries carried out over 60 years ago, the situation in many Western countries today where prison populations have risen significantly following the scaling down of in-patient psychiatric facilities certainly seems to fit the same model.

Diversion mechanisms

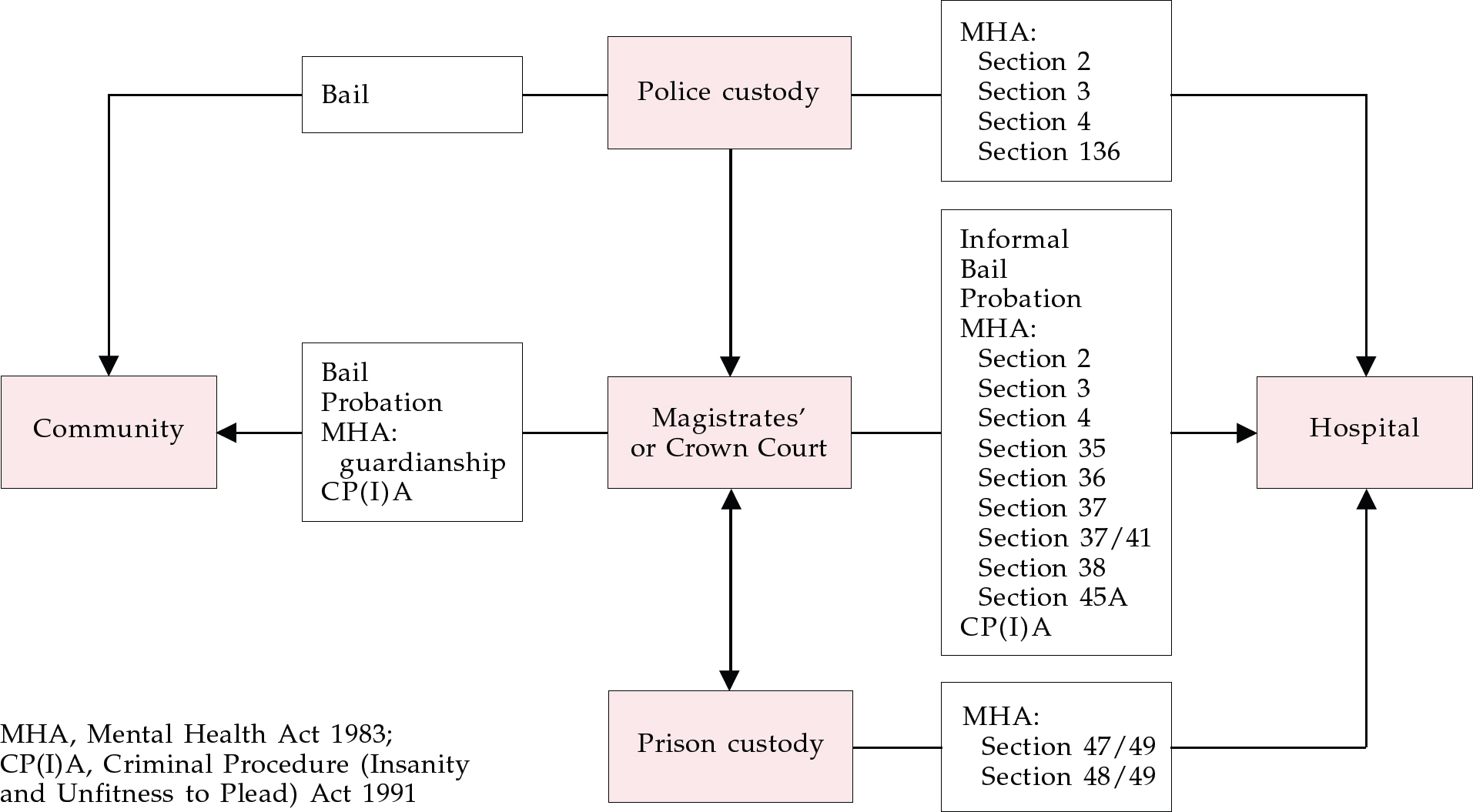

A number of mechanisms may be employed to divert MDOs from custody into hospital or a suitable community setting where they can receive treatment (Fig. 1). Some, which allow the MDO to be diverted from custody, need to be used in conjunction with a second mechanism in order to divert the person to somewhere where treatment can be given. The decision not to proceed with prosecution followed by detention under part II of the MHA 1983 is one such example. Other mechanisms, for example section 37 of the MHA, do both.

Some mechanisms, for example sections 35, 36 and 48 of the MHA, can be regarded as temporary diversion measures because they do not rule out the possibility of the person returning to custody at a future point during that episode of contact with the criminal justice system. Others, for example section 37, provide a definitive psychiatric disposal. The various mechanisms used to facilitate diversion from custody at different stages in the criminal justice process are described in more detail below. Box 2 summarises the functions of the sections of the MHA that may be used.

Box 2. Sections of the Mental Health Act 1983 used in diversion

-

• Part II

-

• Section 2: admission for assessment

-

• Section 3: admission for treatment

-

• Section 4: emergency admission for assessment

-

-

• Part III

-

• Section 35: remand to hospital for report on mental condition

-

• Section 36: remand to hospital for treatment

-

• Section 37: hospital order and guardianship order

-

• Section 37/41: restricted hospital order

-

• Section 38: interim hospital order

-

• Section 45A: hospital direction order

-

• Section 47: removal to hospital of sentenced prisoners (for treatment)

-

• Section 48: removal to hospital of other (remand) prisoners (for urgent treatment)

-

-

• Part X

-

• Section 136: mentally disordered persons found in public places

-

Alternatives to prosecution

Section 136 of the MHA allows a police constable, on finding in a place to which the public have access a person who appears to be suffering from mental disorder and to be in need of immediate care or control, to remove that person to a place of safety (in most cases this is the local police station rather than an accident and emergency department or psychiatric hospital) if he or she thinks this is necessary in the interests of that person or for the protection of others. The person may be held there for up to 72 hours, during which time arrangements must be made for a further (MHA) assessment to be carried out to determine whether or not admission to hospital is required. It is reassuring to note that in about 90% of cases, initial detention under section 136 does result in admission to hospital (Reference TaylorTaylor, 1996).

Alternatively, the officer may decide to make an arrest and take the individual to the police station. If it is apparent that the person has mental health needs, a mental health assessment may be requested to help determine the most appropriate method of dealing with the case. This may result in admission to hospital, informally or formally (under section 2, 3 or, in an emergency, section 4 of the MHA), or placement in the community if suitable facilities are available. If it is clear that the interests of all concerned are not best served by pressing charges, diversion from custody may be accompanied by discontinuation of criminal proceedings. In other cases, in which unconditional release is not appropriate, the granting of police bail allows diversion to a suitable hospital or community setting to take place while the criminal justice process continues.

Once charged, the person must appear before a magistrate. If there is sufficient evidence to discharge the burden of proof and a successful prosecution is likely, the case may proceed. If not, the detained person must be released from custody. Further guidance provided by the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) stresses the importance of prosecution being in the public interest. If the prosecution of an MDO is not in the public interest, or it could place undue strain on the defendant and a suitable alternative to prosecution is available, the CPS may agree to discontinue proceedings and the individual will be diverted from custody. In general, proceedings are more likely to be discontinued during the early stages of a prosecution and in cases involving lesser charges.

It is important to stress that diversion from custody should not be equated with discontinuation of criminal proceedings. Indeed, the criminal justice process is central to the efficient function of many diversion schemes (described below).

It is true that in certain circumstances the decision to discontinue criminal proceedings may confer significant benefits, in that it avoids the cost and additional work associated with a court case and it removes the risk that the court will remand the person into custody. However, it may not offer the best outcome for all concerned. In cases where the need to protect others is a particular concern, a prosecution means that options such as disposal under part III of the MHA or returning the person to custody if the risk cannot be managed safely in hospital remain possible.

Alternatives to remand in custody and transfer of remand prisoners to hospital

The police may grant bail and the courts are also obliged to consider remanding an accused person on bail unless there is a reason to remand in custody. Unfortunately, circumstances often conspire against MDOs (Box 3) and as a result they are more likely than counterparts without mental disorder to be remanded in custody. This may be because they are more likely to be homeless, considered less likely to comply with bail or be perceived as more dangerous by virtue of their mental illness (Reference Taylor and GunnTaylor & Gunn, 1984). Another reason is that the 1976 Bail Act includes a number of objections relating to bail for mentally disordered defendants, even when the offence itself is not punishable by imprisonment (under normal circumstances a defendant cannot be remanded in custody for an offence that is not punishable by imprisonment; Joseph, 1990). Furthermore, although remanding MDOs to prison for the preparation of medical reports is now discouraged, a lack of suitable hospital or specialist bail facilities may mean that there is no other practical alternative.

Box 3. Inequalities in the treatment of mentally disordered offenders (MDOs)

MDOs are more likely than counterparts without mental disorder:

-

• to be arrested

-

• to be remanded into custody

-

• to be viewed as more dangerous simply by virtue of their mental illness

-

• to spend longer on remand

Sections 35 and 36 of the MHA provide the court with powers to remand to hospital instead of remanding in custody (or granting bail). Section 35 allows a court to remand to hospital for a report on the person's mental condition. Evidence is required from one registered medical practitioner to satisfy the court that there is reason to suspect that the person is suffering from mental illness, psychopathic disorder, severe mental impairment or mental impairment and the court must be satisfied that it would be impracticable for a report on mental condition to be made if the individual were remanded on bail. Section 35 allows for detention for up to 28 days, renewable for further periods of 28 days, up to 12 weeks in all. The court may terminate the order at any time if it considers it appropriate to do so.

Section 36, which allows remand to hospital for treatment, requires two medical recommendations; it is applicable only to persons suffering from mental illness or severe mental impairment and can be imposed only by a Crown Court. Initial duration and renewal criteria are the same as those for section 35.

Section 48 enables prisoners held on remand to be transferred to hospital for treatment. Like section 36, it applies only to those who suffer from mental illness or severe mental impairment and it requires two medical recommendations; however, the transfer direction is made by the Secretary of State (the Home Office) rather than the court and the order has no limit of time.

Section 48 is almost invariably accompanied by a restriction on discharge provided by section 49. This removes the authority of the responsible medical officer to grant leave under section 17 or to discharge the patient.

Although section 48 states that the subject must be in urgent need of medical treatment, this requirement does not restrict the use of this order in practice because the threshold for transfer to hospital is set at a level determined by (secure) bed availability. If a bed is available, section 48 provides a quick, simple and flexible method of transferring a remand prisoner with mental illness (or severe mental impairment) to hospital. The main disadvantage of section 48 as a diversion mechanism is that if for any reason the subject ceases to be a prisoner on remand (for example, is bailed or the case collapses) the powers conveyed under section 48 cease with immediate effect. If there is a real risk of this happening a concurrent civil order (section 3 of the MHA) can be imposed.

Hotopf et al (2000), who reviewed the use of the MHA between 1984 and 1996, note the perceived failure of sections 35 and 36 (and 38, described below) to do what the Butler Committee (Home Office & Department of Health and Social Security, 1975) intended. They ascribe the dramatic increase in the use of section 48 (from 77 in 1987 to 481 in 1996) to the fact that more psychiatrists visit prisons than they did 15 years ago, more prisons have sessions with local forensic psychiatrists and court diversion schemes may not always divert, but they do lead to the identification of psychiatric disorder. In my opinion, sections 35, 36 and 38 are probably underused because psychiatric hospital beds are a precious commodity and compared to section 48, which is a quite user-friendly mechanism for diverting remand prisoners to hospital, these orders are relatively inflexible.

Non-custodial disposal

Mentally disordered offenders who are convicted of a criminal offence may be dealt with in a variety of ways. Certain disposals, for example a suspended sentence, may divert the MDO from custody but make no direct provision for psychiatric treatment. A probation order can include a condition of psychiatric treatment, which may also be accompanied by a condition of residence. This can be used to direct the offender to reside in a specified psychiatric hospital, but it does not allow treatment to be enforced against the person's will.

Part III of the MHA provides several options for non-custodial psychiatric disposals via the court. A hospital order (section 37) allows the court to direct the offender to a named hospital, which has agreed to admission, for treatment. Once in hospital the order operates in the same manner as section 3, with the exception of certain details of the appeals procedure, which are different. Section 37 can also take the form of a guardianship order (akin to that provided under section 3).

A hospital order may be accompanied by restrictions (under section 41) if the court considers this is necessary to protect the public from serious harm. A restriction order, which has the effect of limiting the powers of the responsible medical officer to discharge the patient or grant leave, can only be imposed by a Crown Court.

Section 38 (an interim hospital order) may be used to assess response to treatment in hospital with a view to determining whether a hospital order should be made. Unlike section 37, section 38, which lasts up to 12 weeks in the first instance and is renewable for further periods of 28 days up to 1 year, does not provide a definitive disposal.

The power of the Crown Court to make a hospital direction order (under section 45A of the MHA), which was introduced by the Crime (Sentences) Act 1997, provides a mechanism for the temporary diversion of certain individuals suffering from psychopathic disorder to allow them to receive treatment in hospital. However, as this is so rarely used it will not be discussed further here.

The small number of MDOs appearing before the courts each year who are found unfit to plead or not guilty by reason of insanity are dealt with under the Criminal Procedure (Insanity and Unfitness to Plead) Act 1991. This provides a range of disposals from absolute discharge up to the equivalent of a restricted hospital order.

Transfer of sentenced prisoners

Section 47 of the MHA allows mentally disordered sentenced prisoners to be transferred to hospital for medical treatment in much the same way as section 48 (described above) provides for the transfer of remand prisoners. Whereas section 48 applies only to those suffering from mental illness and severe mental impairment, section 47 applies to all categories of mental disorder defined under section 1 of the MHA. Unlike those detained under section 48, the detention of prisoners whose sentence expires while they are receiving treatment in hospital under the provisions of section 47 is extended automatically by a notional section 37, which comes into force at that point. Like section 48, section 47 is almost invariably accompanied by restrictions under section 49 (described above).

Diversion initiatives

Most of the literature on diversion from custody concerns diversion initiatives established at magistrates' court level. However, there are accounts of services based on formal collaboration between police, health and social services and other agencies concerned with offenders and people with mental disorders that provide a multi-agency approach to diversion, with schemes operating at police stations, magistrates' courts and local remand prisons. Some schemes are closely linked to local psychiatric services and a few have access to community facilities such as bail and probation hostels specialising in MDOs (Reference Chung, Cumella and WensleyChung et al, 1998).

Police liaison schemes

According to James (1999), there are currently around 40 diversion schemes operating at police stations in England and Wales. The Diversion at Point of Arrest (DAPA) scheme in the West Midlands (Reference Chung, Cumella and WensleyChung et al, 1998) and the Police Liaison Community Psychiatric Nurse Project in London (Reference EtheringtonEtherington, 1996) are two examples of such schemes. These schemes employ community psychiatric nurses (CPNs) based at police stations to provide on-the-spot mental health assessments of detainees, liaison with police officers and other agencies and training.

A recently published study (Reference Riordan, Wix and Kenny-HerbertRiordan et al, 2000) reported that 0.63% of all arrests dealt with at the five police stations covered by the West Midlands DAPA scheme over a 4-year period (1993–1997) were assessed by the CPN following referral by the police. Of these, 85% were found to have significant mental health problems (the most commonly specified illness was schizophrenia, found in 16%). Admission to hospital was recommended in one-third of cases and in the vast majority of cases this was achieved. The number admitted informally was double that for admissions under the MHA.

James (2000), who studied the London scheme described by Etherington (1996), found that 1.1% of custody cases at the three police stations concerned were assessed over a 31-month period. Ninety per cent were found to be suffering from some form of mental disorder (most commonly schizophrenia or allied states, evident in 42%). Thirty-four per cent of referrals were judged to need hospital admission and 31% of referrals were admitted. Unlike the West Midlands scheme, only 14% of hospital admissions were informal; 77% were under civil sections and 9% were under part III of the MHA (after referral to the court diversion scheme).

Magistrates' court diversion schemes

There are about 340 magistrates' courts in England and Wales. According to James (1999) the magistrates' court was chosen for a new form of diversion intervention because it is located near the beginning of the criminal justice process and it provides a cost-effective filter through which all cases must pass.

The first magistrates' court diversion scheme was established in London in 1989 (Reference Joseph and PotterJoseph & Potter, 1990). Rapid expansion of local court-based initiatives followed and by 1999 there were about 150 of these schemes in operation across England and Wales (Reference JamesJames, 1999). However, the nationwide network of schemes recommended by the Reed report (Department of Health & Home Office, 1992) is still far from complete. Some schemes are stretched across several courts, many operate on a part-time basis and of the 47 prisons in England and Wales that take unsentenced prisoners, fewer than one-fifth have court diversion schemes covering all the courts they serve.

There is no single model on which court diversion services are based. Some schemes seek to screen all detainees, but most operate a filter system accepting referrals from non-health care staff who raise suspicions of underlying mental disorder. The majority of schemes are run by CPNs, but some, particularly in London, are run by psychiatrists who attended court on certain days. Professionals from other agencies, such as approved social workers and probation officers, may also provide input.

Court diversion schemes use a variety of mechanisms to achieve diversion and some are more successful at this than others. Owing to a lack of approved social workers all formal admissions to hospital via the court liaison service described by Exworthy & Parrott (1993) were completed using part III of the MHA. In contrast, use of part III in another London scheme, described by James & Hamilton (1992), proved problematic, not because the courts were unwilling, but because of the bureaucratic approach of catchment area services when part III sections were recommended. In another London scheme (Reference Joseph and PotterJoseph & Potter, 1990) most formal admissions were achieved using part II of the Act and all cases admitted under civil sections were discontinued by the prosecution. In Leeds, Chambers & Rix (1999) reported low rates of discontinuation and in Rotherham, where access to secure beds proved difficult, magistrates were not willing to cooperate with recommendations for admission to open units or out-patient treatment (Reference Rowlands, Inch and RodgerRowlands et al, 1996).

Features of schemes that are successful at diverting MDOs from custody are summarised in Box 4. According to James (1999), schemes that are most successful at diverting cases into hospital tend to be run by psychiatrists (especially consultants) and ‘owned’ by a mainstream general or forensic service. Nurse-led schemes are most effective when closely linked to local psychiatric services.

Box 4. Features of successful court diversion schemes

-

• ‘Owned’ by mainstream general or forensic services

-

• Staffed by (senior) psychiatrists

-

• Nurse-led and closely linked to local psychiatric services

-

• Good working relationship with magistrates and the prosecution

-

• Good methods for obtaining health, social services and criminal record information

-

• Access to suitable interview facilities

-

• Use of structured screening assessments

-

• Direct access to hospital beds

-

• Ready access to secure beds

-

• Access to specialised community facilities

-

• Integrated with police liaison and remand liaison schemes

There has been very little research conducted into the medium- and long-term outcomes of subjects diverted from custody by magistrates' court diversion schemes. The few studies that have been published involve small numbers. Joseph & Potter (1993), who examined 65 hospital admissions, concluded that 77% derived some or marked benefit, but 46% of those admitted absconded. A subgroup who did badly were more likely to be of no fixed abode, have higher rates of criminality and previous compulsory admissions to hospital. Rowlands et al (1996), who followed up 82 diverted individuals for a mean period of 12 months, found that 38% gained no benefit from intervention at the court: they either absconded from hospital within a few days of admission or did not attend as out-patients; reoffending occurred in 18% of cases. Those who were admitted to hospital were more likely to benefit than those who were not. Holloway & Shaw (1993), who carried out an 18-month follow-up of 22 patients for whom psychiatric or social care was arranged, concluded that individulas with mental illness who were diverted were ‘maintained’ despite poor cooperation. Chung et al (1999) followed up 65 individuals at 6 months after diversion and 22 at 1 year. They found that the quality of life of these people was poor, there was little change in their psychiatric condition, and although over half (12) of those followed up at 1 year were still in contact with their general practitioner, there was a significant drop in those consulting hospital doctors.

Remand liaison schemes

To provide continuity of care for MDOs who are remanded by the courts, a number of diversion schemes based in magistrates' courts have extended their input into local remand prisons. Remand liaison schemes, which are often run by CPNs associated with the local court diversion scheme, serve to track MDOs who are remanded into custody and help ensure that their treatment needs are met. One of the most important roles of a remand liaison scheme is to ensure that the court, prison and psychiatric services communicate with one another.

Chung et al (1998) describe a CPN-led remand liaison scheme at a local remand prison in Birmingham that operates as an extension of the West Midlands forensic diversion services. Community psychiatric nurses screen all newly remanded prisoners and bring those with mental health needs to the attention of prison health care staff. Referrals are also made to visiting forensic psychiatrists.

Murray et al (1997) and Weaver et al (1997) describe a different type of remand liaison scheme operating at Wormwood Scrubs prison. The Bentham service, which opened in 1994 with a 14-bedded locked ward (formerly an interim medium secure unit) run by nursing staff and a multi-disciplinary team led by a consultant forensic psychiatrist, was set up to provide a rapid assessment service, identify mentally disordered remand prisoners and speed their transfer from prison to National Health Service (NHS) care. Murray et al (1997) state that in its first year the service assessed 150 referrals, of whom 42% were admitted. Most were transferred under section 48 of the MHA with minimal delay. At 3-month follow-up 56% were still in-patients and 21% were being followed up subject to supervision in the community.

Psychiatric services for prisoners

All prisoners in England and Wales undergo health screening at first reception into prison. This routine medical examination has been part of the regime in some prisons for over two centuries. Unfortunately, current prison reception health screening procedures have been shown to be ineffective (Reference Birmingham, Mason and GrubinBirmingham et al, 1997). As a result, the majority of MDOs entering prison on remand are not identified as such and they are placed on ordinary location (in a standard cell on the prison wing or houseblock) where their needs are liable to remain unrecognised (Reference BirminghamBirmingham, 1999).

Until very recently the NHS had no statutory responsibility for the provision of health care to prisoners. As a result, prisoners have traditionally been afforded poor standards of health care and NHS psychiatric input into prisons has been patchy and poorly coordinated. Relatively few prisons have formal arrangements with NHS psychiatric services to provide regular input from a multi-disciplinary team. Indeed, many prisons still receive no regular input from the NHS at all. If a prisoner in one of these prisons becomes mentally unwell the prison is usually faced with having to transfer the inmate to a larger prison that does have access to visiting NHS psychiatrists.

Future developments

The past decade has seen a considerable growth in local diversion initiatives, especially those operating at the magistrates' court level. However, because service development has not been centrally coordinated or strategically planned we now have a patchy national network, comprising a heterogeneous group of diversion schemes. This falls a long way short of the sort of service recommended in the Reed report (Department of Health & Home Office, 1992).

The era of the pilot project, set up at the local magistrates' court with Home Office ‘pump-priming’ funding, has now passed. The literature suggests that many such schemes, which find themselves isolated from mainstream psychiatric services, fail to achieve what they were set up to do. Diversion initiatives operating at the magistrates' court level must adhere to a model based on the characteristics shared by the relatively small number of schemes that do function effectively (Box 4). They must also be regarded as part of mainstream services for people with mental disorder provided by the NHS.

Although a great deal of attention has been focused on the development of court diversion schemes, a truly effective diversion service requires a complementary range of diversion initiatives operating at every stage in the criminal justice system. Such services need to incorporate police-liaison and remand-liaison schemes, as well as court diversion schemes and services intended to provide better health care in prisons. They need to use effective screening methods to identify detainees with mental health needs and they must have access to appropriate facilities into which those who need treatment can be moved. The complex nature of the problems caused by those with mental disorder in contact with the criminal justice system means that diversion services need to adopt an integrated, multi-agency approach. In future, services must be properly coordinated (locally and nationally) and provided with adequate resources.

The report of the Prison Service and NHS Executive Working Group (1999) on the future organisation of prison health care represents a recent milestone in the reform of health care in prisons and the future of diversion from custody. The main reason for this is that it resulted in a formal partnership between the NHS and the prison service to provide improved standards of health care to prisoners. The report also advocates the principle of strategic development in prison health care, but it does not suggest how the changes that are recommended will be resourced. An indication of the Government's commitment in this area is provided in the NHS Plan (Department of Health, 2000). This document includes recommendations for more resources to improve services for people with mental disorder in community, hospital and other specialist settings as well as in prison.

What effect these extra resources, promised by the Government, will have on services for those with mental disorders remains to be seen. What is clear is that at present our social and political climate is such that these people remain vulnerable to imprisonment and there are currently thousands of people with mental disorders in our prison system who need treatment in hospital. Even if these individuals were identified they could not be afforded hospital treatment because NHS in-patient resources are currently struggling to accommodate the minority of severely mentally disordered prisoners whose needs have been recognised. In light of this, it seems reasonable to conclude that the prison health service and NHS services involved in diverting those with mental disorders from custody will continue to experience an uphill struggle for some time to come.

Multiple choice questions

-

1. The following sections of the MHA 1983 are available to magistrates:

-

a section 35

-

b section 36

-

c section 37

-

d section 38

-

e section 37/41.

-

-

2. Diversion at the magistrates' court level in England and Wales:

-

a consists of some 340 schemes

-

b consists mainly of nurse-led schemes

-

c is not centrally coordinated and funded

-

d is proven to be successful in most cases

-

e began in 1979.

-

-

3. Court diversion schemes successful at diverting defendants to hospital are more likely to:

-

a be ‘owned’ by psychiatric services

-

b be staffed by psychiatrists

-

c have direct access to hospital beds

-

d use structured (as opposed to standard clinical) screening interviews

-

e use section 47 of the MHA 1983.

-

-

4. Remand to prison is more likely if:

-

a section 136 has been used

-

b the defendant has a mental illness

-

c the defendant is homeless

-

d the defendant faces minor charges

-

e the defendant needs a medium secure bed.

-

-

5. In prison (in England and Wales):

-

a reception health screening identifies most of those with mental health problems

-

b treatment for mental disorder under the MHA 1983 can be given only in the prison's health care centre

-

c there are about 5000 people withschizophrenia

-

d section 47 of the MHA 1983 is used to transfer mentally disordered sentenced prisoners to hospital for treatment

-

e the NHS is now responsible for all health care delivered to mentally disordered prisoners.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | T | a | F | a | T | a | F | a | F |

| b | F | b | T | b | T | b | T | b | F |

| c | T | c | T | c | T | c | T | c | T |

| d | T | d | F | d | T | d | F | d | T |

| e | F | e | F | e | F | e | T | e | F |

Fig. 1 Diversion from custody

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.