A marketplace of pleasure emerged, and that market, open and sensitive to foreign influences, made possible new socialities of seduction. […]. In Abidjan, people talk freely about carnal pleasures, they express at liberty sexual curiosity during conversations that should be limited to friends. (Le Pape and Vidal Reference Le Pape and Vidal1984: 111–12, my emphasis)Footnote 1

Since its opening two months ago, our bar has been successful. We opened it so these kids can have fun and give each other pleasure. (Bar manager quoted in Diawara Reference Diawara2016, my emphasis)

The terms “plaisir” and “marketplace” in this article come from the largely forgotten 1984 essay by Marc Le Pape and Claudine Vidal on the relationship between sexual pleasure and liberalism in Abidjan. Although the words are not defined in the essay, they point to an unrestrained erotic acceptance that has been facilitated since the country’s 1960 political independence and which has amplified in the last two decades, as Abidjanais have created new ways of enjoying, managing, and profiting from the greater available marketplace of erotic pleasure.

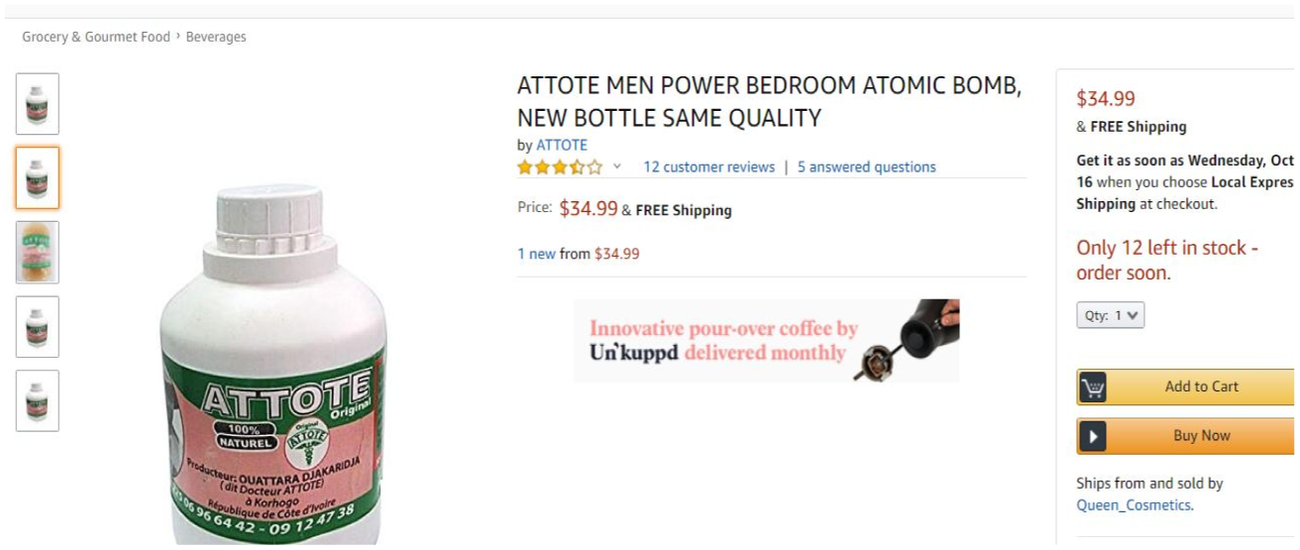

Taking Le Pape and Vidal’s terms seriously, I offer an overview of the contemporary sexual economy of pleasure in Abidjan, focusing in particular on materials such as branded objects that others have overlooked. In French, Malinké, and Nouchi, these materials include dildoes, packaging and flyers for body-enhancing products, and aphrodisiacs. Although I provide a larger context that shows the richness of materials in this sexual ecosystem, I focus on eight visuals: five of male aphrodisiacs (AtoteFootnote 2 and Baracouda or 40 mns to Orgasm) and three on female buttocks-, hip-, and breast-enhancing capsules and syrups. Two objects relate to the popular male sexual enhancer Atoté; one is an advertisement on an e-commerce site, and the other is an Amazon seller’s description of a product. The other visuals are (1) a flyer for Baracouda in Abobo’s popular market, (2) two stands selling female and male aphrodisiacs in Koumassi and Adjamé, (3) a store in Treichville that trades in the buttocks-enhancing product, the botcho cream, and (4) the logo of its self-proclaimed original manufacturer, the so-called Dr. Zoh. These visuals, which I photographed in four of the ten communes of Abidjan—Abobo, Adjamé, Koumassi, and Treichville, a number that suggests the widespread nature of the sexual free-thinking economy—show the use of images and replicas of sexual organs, direct messages, and the credentials, photographs, and addresses of manufacturers as part of sophisticated marketing and branding campaigns.

Visuals undeniably constitute a markedly important aspect of our lives, and they are central in shaping behaviors and selling anything. Selling the promise of and also giving sexual pleasure via flyers, dildoes, and packaging, I argue, all relate to what I call the pleasure market. Here, I understand the term “market” in its primary sense of marketing and purchasing within a given ecosystem. A detailed analysis of these visuals offers compelling examples of how to consider this sexual openness as the domain of economic actors, homines economici, in the most technical sense.Footnote 3 Although vendors rely on visuals to dispense and sell the promise of pleasure, the visuals can themselves be sources of pleasure for the customers, who rely on images and their appeals to help them make a purchasing decision. Thus, I acknowledge the agency of all the participants in the market of sexual pleasure without pronouncing on their moral preferences or imposing mine on them. While I do not minimize the health impact of these behaviors, I refuse to reduce the people involved to the status of children who can only be seen through the prism of those who want to set them straight, be those aid donors, religious principals, moralizing journalists, or patronizing academics.

Upon sketching out the broad contours of the context in which the actors and the visuals interact, this article embarks on a definitional excursion of pleasure before investigating the ways in which the logic of branding and marketing determines the rational characteristic of the pleasure market. In sum, through the economic dimension of things, as it intersects with visuality, this study expands the outlines of the vibrant scholarship on pleasure that has principally celebrated queer and female pleasure and explored sex work and the transactional aspect of sexual and affective relationships in cities such as Nairobi, Dakar, and Abidjan.Footnote 4

Abidjan by Pleasure

The above-mentioned eight visuals which are the crux of this study do not exist in a vacuum. In fact, they participate in the greater milieu in which the proliferation of sexual activities and actors demonstrate how Abidjanais are sensitive to and deploy proactive strategies to profit from the economic boom and the seeming indifference of the state to the hypervisibility in the public sphere of images and scenes of sexual pleasure. Sex and the city entertain an entangled relationship, which is even more compelling because a cursory look at the major streets of Abidjan, at its online spaces, and in news reports (between 2007 and 2021), demonstrates that the city is vibrating with sexual pleasure. The unfettered sale of aphrodisiacs, the repurposing of “bars climatisés” (air-conditioned bars) and market stalls (guattas) into pseudo-brothels and motels, the feminization of the mougoupan,Footnote 5 the emergence of new economic actors such as the géreuz de bizi and les free-lances, increased teenage pregnancies, unregulated sex work, new sartorial tendencies, and sexually suggestive dance moves and pop music confirm this rampant erotic free-thinking, which elicits primary reactions of repugnance and condemnation, depending on the constituencies.

Back in 2008, bars caught the attention of several Ivorian and African newspapers (Diawara Reference Diawara2016; Notre Voie Reference Voie2015; Fraternité Matin 2012; Kangah Reference Kangah2010; I. T. Yéo Reference Yéo2008). In his apocalyptically titled “Le sexe envahit les bars climatisés d’Abidjan” (“Sex is Invading Air-Conditioned Bars in Abidjan” [my emphasis]), Issa Yéo (Reference Yéo2008) noted the repurposing of existing bars into pseudo-brothels. Unsurprisingly, the term “invading” reveals the reporter’s disapproving attitude toward this sexual hypervisibility. His statement “Abidjan est ‘gâté’” [“Abidjan is rotten”], a popular phrase, explains the rollicking-but-unsavory aspect of the capital. These bars offer alcohol, cigarettes, strip-tease performances, and even orgies (Yéo Reference Yéo2008; Armand Reference Armand2012). In 2016, the Reporter de Guinée published an article with the headline “A la découverte des pratiques incroyables des ‘bars climatisés’ à Abidjan” [“Uncovering Unbelievable Practices in Air-Conditioned Bars in Abidjan”]. Complete with pictures of girls in their underwear, the article names several bars in two communes as places where young people aged fourteen to twenty-five congregate to “have fun and give each other pleasure,” as a bar manager was quoted as saying (Diawara Reference Diawara2016).Footnote 6 Perhaps more preoccupied with the rewarding economic outcome, rather than with the moral implication, the bar manager celebrates this development. Regardless of his moral position, the presence of the youth in the establishment suggests the emergence of new modes and spaces of sexual expression and freedom. Although Moussa Diawara does not provide the bar manager’s definition of pleasure, perhaps because he assumes that everyone knows what pleasure is, the meaning of pleasure is anything but a simple affair, a point I revisit below.

Pursuant to or concomitant with the sexual invasion, in a 2013 Netherlands radio program on the life of youth in Abidjan, a group of six Ivorian students complained that sex was “everywhere”—newspapers, television, on their cell phones, in their streets, and even in their homes. They added that they no longer needed to look for sex because it came to them; it found them (Radio Netherlands Worldwide 2013). Sex has thus acquired an agency of its own, forcefully occupying spaces and subjecting youth to its domineering presence. This oppressive existence led one journalist to recycle the lyrics from the national anthem, “Côte d’Ivoire: The Land of Hospitality” (Côte d’Ivoire: Le pays de l’hospitalité): “The land of hospitality wears its libido hanging on its sleeves [….]. Ivorians constantly have it [libido] on their minds. And in their mouths [consumption of aphrodisiacs]. Sex has become the major subject of discussion and concern” (Kwacee Reference Kwacee2015).Footnote 7 In uncanny ways, Améday Kwacee’s interpretation echoes Le Pape and Vidal’s observation of almost four decades ago. In 2015, another journalist investigated the world of aphrodisiacs in the streets and markets, comparing Abidjan to a vast and open market of “sexual healing” (Koffi Reference Koffi2015). Serge Alain Koffi’s use in his French paper of the title of Marvin Gaye’s 1982 hit song “Sexual Healing” is a shortcut that resonated with his readers, most of whom would have been familiar with the song that frequently played on radio in the 1980s and 90s. Music works here as a prominent vehicle in discussions of the public display of sex in its enticing, satisfying, healing, and oppressive capacities.

In this context, journalists also identify new economic actors and sites selling promises of sexual pleasure: retailers of Atotté (male aphrodisiacs), sellers of Bobaraba (buttocks-enhancing syrups and capsules), advertisers of penis- and breast-enlargement surgeries, géreuz de bizi (occasional female sex workers), les free-lances (North African high-end female sex workers), landlords of guattas (random market stores that are rented out to sex workers on a client-by-client basis), and managers of bars (Ouédraogo Reference Ouedraogo2007; Gnantin Reference Gnantin2013; Koffi Reference Koffi2015; Kadiri Reference Kadiri2017). These commentators point systematically to deleterious structural factors, namely the high unemployment rate, pauperization, the consistent disappearance of the welfare state, and the unstable socio-political logic, as the impetus forcing these actors to seek new sources of income.Footnote 8

Similarly, these reporters adopt a patronizing stance, castigating those who provide sexual services or who purchase Bobaraba or Attoté potion as ignorant and irrational risk-takers (Adélé Reference Adélé2015; Gnantin Reference Gnantin2013; Koffi Reference Koffi2015; Koffi Reference Koffi2011; Kwacee Reference Kwacee2015; Yéo Reference Yéo2008; Yeo Reference Yeo2016). The perceived disregard by the sellers and buyers for their personal safety during the still-rampant HIV/AIDS epidemic influences the condemnatory tone of these articles. This presumption of ignorance or misinformation places the patrons in a state of victimhood, denying them the capacity to rationally assess situations and take calculated risks. This normative approach to what people ought to do with their sexual lives and economic prospects aligns with the problematic epidemiological approaches to sexuality; it borrows from the HIV/AIDS prevention discourse that often regards these actors as misinformed and in need of education (Ssewamala et al. Reference Ssewamala2019; Toska et al. Reference Toska2017).

However, a closer look at the visuals and the activities of the buyers highlights the marketing sophistication behind the products, a feature that belies the interpretation of consumers as uninformed, infantile, reckless, and/or irrational. Additionally, one may ask, and for good reasons, what does pleasure have to do with sex? The answer is, two things. The most direct ways to engage with erotic pleasure are through subjective expression and through the objects associated with it, explicitly aphrodisiacs and sex toys. Given my methodological approach of not interacting with people, subjective expression is not part of my investigation. Thus, my emphasis is on these objects. Relatedly, as I demonstrate below, sellers of aphrodisiacs and buttocks-enhancing products are not selling sex. What they are selling instead is the promise of pleasure. Aspiration and consumption of pleasure also unfolds with the ads, as they themselves may be viewed as pleasurable. This fits into the discussion of scopophilia, the “love of looking,” which is most often associated with the objectification of women. Identifying what constitutes pleasure is, nonetheless, a fraught enterprise, because of the ever-shifting nature, objects, and strategies for attaining or providing pleasure.

(Sexual) Pleasure: “Wheyting be Dat?”

This section exposes the supposed struggle to operationalize pleasure. I reprise the title of Chris Dunton’s Reference Dunton1989’s essay, and ask “Wheyting be Dat?” Given the importance of pleasure in the life of organisms, including humans, most academic disciplines and intellectual traditions, from utilitarianism and queer studies to Marxism, ethics, and film studies, have engaged the term and the emotion. In no particular order, I categorize these engagements along the following lines: what pleasure can do, what it feels like, how it is used, and what it should be used for. A second organizational schema can be based on five lines of inquiry: (1) the difficulty of defining pleasure (Foucault Reference Foucault1978, Reference Foucault, Rabinow and Hurley1997; Hartman Reference Hartman, Kermode and Alter2004; Sullivan Reference Sullivan1999; Mulvey Reference Mulvey1975); (2) pleasure as vital force (Lorde Reference Lorde1978, Nzwegu Reference Nzegwu2010, Aristotle Reference Irwin1999); (3) pleasure as conscious and unconscious (Freud et al. Reference Freud, Dufresne and Richter1922; Berridge & Kringelbach Reference Berridge and Kringelbach2008); (4) pleasure as ideology (Harvey Reference Harvey2005; Brown Reference Brown2015; Jameson Reference Jameson and Jameson1983; Halperin Reference Halperin and Stanton1992); and finally (5) pleasure as pleasing and painful (Perros Reference Perros1960; Berlant Reference Berlant2008).

Here, I concentrate on two putatively opposite trends: the difficulty of operationalizing pleasure and compelling definitions of pleasure. As mentioned earlier, like Le Pape and Vidal, journalist Diawara does not provide the bar manager’s definition of pleasure. The presumption of transparency and familiarity that undergirds that methodological approach frustrates those who argue that pleasure eludes or exceeds all conceptualizing efforts.

The French historian-philosopher Michel Foucault’s famously irritated “Pleasure—nobody knows what it is” stands as a reminder (Reference Foucault, Rabinow and Hurley1997:359). Yet, Foucault proceeded to situate pleasure within power relations, advocating an ethics of sexual behavior based on pleasure and its potentially liberatory characteristic (Reference Foucault1978). His unconvincing stance on the definitional difficulty surrounding pleasure resonates with that of many thinkers. Standing out among those who argue the impossibility of defining pleasure are literary theorist Geoffrey Hartman and queer scholar Nikki Sullivan. For Hartman, “The word pleasure is problematic—I am attempted to say ‘abysmal’— for several reasons. First, for its onomatopoeic pallor, then for its inability to carry with it the nimbus of its historical associations [ …]. Though literary elaboration has augmented the vocabulary of feeling and affect, pleasure as a critical term remains descriptively poor” (Reference Hartman, Kermode and Alter2004:58). Definitions of pleasure have mushroomed since Hartman made his claim. For Sullivan, pleasure is queer because it is a “pre-discursive, pre-subjective event, an exposure, a becoming-open that is unnamable. Pleasure is a transformative process, not because it is something I can employ to my own ends, but because it inaugurates the very site of (un)becoming. Pleasure exists before the question of its meaning, its use, arises” (Reference Sullivan1999:254).

It is obvious that those who argue the difficulty of defining pleasure actually end up formulating it. Thus, they join those who explicitly provide meanings. More broadly, pleasure affectively designates the subjective experience of conscious or unconscious niceness, which includes all fleeting affects of joy, gladness, liking, and enjoyment. Neurobiologists, however, are much more specific, as they define pleasure as whatever tickles our limbic system or sets our dopamine, the pleasure chemical, surging (Berridge & Kringelbach Reference Berridge and Kringelbach2008). As such, pleasure is understood as one of the key motivational components of reward-motivated behavior. The enticing nature of pleasure explains its potentially obsessive and destructive nature.

The unconscious or conscious nature of sexual pleasure, the eagerly sought after or unwanted experience of erotic pleasure, the possibility of offered or stolen sexual pleasure, the staggering number of norms regulating sexual pleasure, and the infinite variety of languages to recognize, interpret, and communicate ideas and meanings of pleasure make it challenging to rely on subjective expression for its study. Hence my attention to objects and publicity strategies. Conventionally, aphrodisiacs (substances or foods that are alleged to augment sexual desire, arousal, performance, or pleasure), sex toys (objects or devices used for sexual stimulation or to enhance sexual pleasure), and sex work (provision, availability, and pursuit of sexual satisfaction) are useful to suggest ideas, practices, and notions of pleasure.

However, is there something called pure pleasure, pleasure that is beyond social pressures, personal goals, cultural expectations, and situational factors? What about memories, fantasies, and perceptions? It is a futile exercise to disambiguate the pursuit of sex and the satisfaction of pleasure. Necessarily, the use of sexual objects and the deployment of sexual strategies respond to other motivations: cultivating self-worth, expressing machismo, justifying boasting rights, and more. These other motivations belie typical formulations of pleasure as something pure. As such, Jill Lewis and Gill Gordon draw on their work on sexual health, rights, and safety within many communities to offer an extensive definition of pleasure. Their runaway eclecticism deserves a lengthy quotation:

Pleasure itself can be defined in different ways. If your children or grandparents are starving or ill, if you are unemployed or poor, if you are in a conflict zone far from home, then a paid sexual encounter could be joyful not because of actual physical or emotional satisfaction, but because you are accessing possibilities of affirmation. If the sex is consolidating the support you need to give you and your children respect in a community, the pleasure can be in the confirmation of the pact. If you are far from home in a risky conflict situation, far from the intimacies of family or community, living in discomfort, facing the unknowns of danger, injury or death, under pressure to keep up a “front” in mostly male company, then the pleasure of sex with a local woman, enabled by financial exchange, may not be just about orgasm, but involve a whole range of reassurances and comfort. If you live in a civil war, with collapsed social infrastructure, widespread abject poverty and minimal family resources and violence in the home, your sexual experience with the older sugar daddy (who is enabling your only possible access to education, as a girl) may also be the kindest, most pleasuring relation you have. If the necessity of work or trading take you away from home, boredom, loneliness and curiosity can draw you into private exploratory pleasures not necessarily condoned back home. If you live in a community scarred by HIV and AIDS, the greatest pleasure may be gained by knowing how your exploring sexual pleasure has absolutely no chance of getting you infected, or infecting your partner. (Lewis & Gordon Reference Lewis and Gill2006:111)

It is precisely this variety of tastes, goals, and strategies that vendors tap into to sell the promise of pleasure via visuals.

Visualizing, Promising, Marketing, Branding Pleasure

The proliferation of economic actors in the marketplace of pleasure in Abidjan is in tandem with their ever-increasing dependence on visuals to sell and buy wares and services. Visuals are decidedly an important part of our lives, and they are central in shaping behaviors and selling anything. As these actors compete for the attention and resources of buyers, their marketing tactics become ever more sophisticated and numerous. Social media platforms (Tiktok, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Twitter), e-commerce sites (Esty, eBay, Amazon), and the Web, due to their highly visualized nature, provide the means to explore the current sexual economy of pleasure. However, despite their centrality in our lives, these visuals have been overlooked in the study of erotic pleasure in Abidjan.Footnote 9

In the dense field of local and China- or India-made male and female aphrodisiacs operates an intricate web of figures: naturopaths, medicine women and men, manufacturers, importers, distributors, salespeople, retailers, facialists, hairdressers, and manicurists.Footnote 10 They offer potions, powders, pomades, pills, creams, and injections, promising their male clients intense pleasures and enlarged penises and their female clients increased buttocks, breasts, and hips, and by extension marital fidelity, and/or financial rewards.

These merchants of pleasure deploy sophisticated marketing and branding tactics, including colorful images on their packaging and advertising flyers, appealing names for their products, and bombastic credentials of manufacturers and retailers. They openly offer their merchandise on various sites, from the most concrete to the most digital. Markets, streets, and major bus stations are replete with flyers promoting various products. Audio-visual platforms such as vehicles mounted with loudspeakers, boomboxes with recorded messages in market streets, and radio and television stations reach audiences that written texts and images may miss or offend. The audio ads utilize local languages that non-French speakers can access. The sonic component also boosts the strength of the message with music, using entertainment to sell. The digital sphere augments the hypervisibility of ads for aphrodisiacs. Such platforms as Amazon and social media reach a still larger audience, those with access to a smartphone and an internet connection.

In relation to naming their products and businesses, these businesswomen and men use popular terms in indigenous languages, Nouchi, and French with an eye toward marketing and branding. Specifically, female-targeting capsules, syrups, and pomades are named after the body parts they putatively enhance: Bobaraba, Botcho, Big Botoss, or Awoulaba 18+, iPhone X (see Figure 1) (protuberant buttocks), and Lolos (big breasts). The increased demand for these products was noted in the mid-2010s (AFP Reference Presse2016). The Malinke (bobaraba), Nzeman (lolo), Akan (awoulaba), and Nouchi (big botoss, botcho) terms have been popularized through pop music and pageant contests. The music video of the pop artist Meiway’s 2001 hit song “Miss Lolo” features big-breasted women.

Figure 1. A market stand of iPhones, buttocks-enlarging syrups, and healing products. Adjamé market, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, July 25, 2021. Courtesy of author.

The latest name in buttocks- and breast-enhancing products is iPhone X, which builds on the popularity and the upscale nature of the Apple brand. This stand (see Figure 1) in the popular market of the commune of Adjamé (in September 2021) proposes several items—whitening creams, stomach-flattening lotions, fat-burning capsules, and hip-, buttocks-, and breast-augmenting syrups. The male vendor refused to have his stand photographed unless I purchased an item, which I agreed to do. I was particularly interested in the iPhone X syrup, whose name and packaging were designed with an eye toward marketing. One side of the packaging is covered with the image of a black female body from her buttocks to her head, dressed in a thong and a skimpy lacey bra. The back of the figure faces the viewer, displaying her protruding and shiny buttocks, one side of which is tattooed with intricate signs. Her nether part is covered with a stock picture of a medley of fresh fruits, highlighting the supposed natural composition of the syrup. The syrup as the form of the product suggests conventional accounts of female parts as juicy or as a fruit. Wearing a wig, the model looks over her shoulder with her eyes lowered in a coy and inviting look. Across her back is splashed the name, iPhone X. A different side of the packaging features another female figure, dressed in a thong and sitting on three iPhones. These images are not only aspirational but also pleasurable. In enacting the visual in this manner, the ads become a source of pleasure in and of themselves, for the customers, this writer, and ostensibly her readers as well. The catchphrase reads, “chéri donne moi iPhone. Je vais te mettre bien” [“Baby, give me an iPhone, and I’ll make you feel good”). The transactional nature of the message works this way: the female consumes the product and enhances her buttocks, the male enjoys the visual and by extension the carnal pleasure and gives in return to the female the coveted object, the iPhone.

Given that these products supposedly increase targeted female body parts, their primary use in the context of sexual pleasure is highly mediated through visual pleasure, as they supposedly make a woman feel that she is more feminine than her peers. Whereas products sold to males are those that claim to directly enhance male pleasure, those offered to women frame the female body as the site of male pleasure. Thus, a gendered division remains in place in this specific African urban setting when it comes to the experience of pleasure for males and females. Male pleasure is privileged, as it is the one that both females and marketers cater to. As such, I propose to designate such products as male aphrodisiacs.

Similar to female products, names of male aphrodisiacs—Bazooka (weaponry), Black Cobra (the action movie), Caiman (night puller and alert worker), and Baracouda ou 40mns avant de jouir (Baracuda or 40mns to orgasm)—borrow from popular culture. However, unlike the names of female items that reference body parts and point to happy households and similar taglines, “Baby, give me an iPhone, and I’ll make you feel good” or “foyer, bonheur” (household, happiness), names of male products evoke power, resistance, domination, and danger. Some male products carry names with still more suggestive connotations, such as Erect E- 40, and Excellence 4. The “40” and “4” refer to the length of the bazooka or the number of minutes to reach orgasm.

The name “Baracouda ou 40mns avant de jouir,” with the alternative connector “ou” (“or”), is unequivocal in its specificity. Taken in the context of the popular market of Abobo, the flyer (see Figure 2) appears in an unlikely place. The store that offers dry goods such as rice, millet, and beans is staffed by men from either the Malinké/Dioula group of Mali, Guinea, and northern Côte d’Ivoire, or the Hausa group of Nigeria and Niger. Not surprisingly, given the conventional understanding of these individuals as publicly restrained in matters of sexuality, I did not expect such a place to serve as the advertising spot for a sexual enhancement product. I spotted the same flyers in other neighborhoods. Explicit in its message and crude in its design, the poster features no picture or colors (other than black and white) that may offend some sellers as well as buyers. The crudeness of the design may reflect the seller’s intended goal, thus indicating sophistication (as she knows her audience), or lack of resources for a more colorful ad. “Baracouda” in the appellation of the product is a nod to the widely known American actor Mr. T, who remains in Abidjan and perhaps elsewhere the epitome of traditional masculinity, with his bulging muscles, threatening facial expressions, and an intimidating physical and emotional makeup.

Figure 2. Flyer advertising Baracouda or 40mns to Orgasm in the market. Abobo, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, December 20, 2021. Courtesy of author.

Other names such as Attoté and Cure-dent Gouro have strong ethnic affiliations. The oldest name of all, “Cure-dent Gouro,” includes the French word: cure-dent (toothpick) and Gouro (the name of an ethnic group from central-west Côte d’Ivoire). Cure-dent Gouro refers to a toothpick whose juice putatively carries aphrodisiac effects. In 2013, singer-songwriter Bi Sery Zéphirin released an album with the song “Cure-dent Gouro.” Note that in September 2021, the cure-dent gouro festival was held in Zuenoula, Gouroland. One of the newer and most popular sexual stimulant brand names is Attoté, as exhibited below. Attoté is a polysemic Malinké word that means “I’m full” (in the food sense) or “Stop/I can’t take it” (in the sexual sense). The late pop artist DJ Arafat’s 2015 song “Attoté” disseminated the term beyond the circles of men who use the potion.

As suggested earlier, the logic of branding and advertising extends to images on packaging that often feature penises of an unlikely large dimension and prominent female buttocks in various states of positioning and covering. In some settings, however, sexual objects, namely dildoes, become advertising strategies, as with the stand of a seller of male aphrodisiacs at the Grand-Carrefour of Koumassi, a busy location (see Figure 3). During the three years (2019 to 2021) that I followed this retailer, unconventionally large black and white dildoes have been the markers of his wares. I have never interacted with him directly for methodological reasons; the choice of leaving out the actors’ formulations of their intentions overlaps with my focus on the visual.

Figure 3. Man selling male aphrodisiacs and a captivated prepubescent girl. Grand Carrefour, Koumassi, Abidjan. Côte d’Ivoire, September 2020. Courtesy of Adjara Diabaté.

Certainly, the man is not in the business of selling dildoes, which may be visually pleasurable objects for some viewers, although that may appear to be the case at first glance. Instead, these erotic objects are intended for publicity purposes. They attract prospective clients to the man’s merchandise, which include male sexual enhancers in glass and plastic bottles, pouches, boxes, and more. These containers whose packaging features penises appear to contain artisanal and industrially-produced powders, capsules, potions, and creams. Given the vendor’s location, his items are not mediated through posters, flyers, and other audio-visual formats. The directness of the message and the availability of his products go hand in hand. The ease with which these objects occupy the public space explains the supposed indifference the scene provokes in targeted or non-ideal audiences. One of those non-targeted audience members is a prepubescent girl.

Out of dozens of pictures taken over time, I chose this particularly arresting one for one reason: the appeal or rather the intrigue the table incites in a markedly unlikely audience member, the young girl. Whereas the seller performs his act of drawing attention to his goods by screaming at the top of his lungs and using expansive body language, fellow retailers apathetically continue their activity of selling apples, as seen in the image, and passers-by carry on crossing a highway that is unfriendly to pedestrians. As for the little girl, who seems to be crossing the highway, she is distracted from her initial intention. Captivated, or rather aware of the unusual scene, she turns her upper body to the right and stares at the table, which is dominated by four dildoes, three white and one black. Although she is certainly not the target of the marketing message, the girl is nonetheless caught up in Abidjan’s vast and open market of sexual pleasure.

In that ecosystem where all marketing strategies are allowed, this seller’s marketing ploy evidently yields financial reward, as he consistently entertains buyers and has been at his trade for the last three years that he has come to my attention, and perhaps longer.

If unflinching objects, images, popular names, and bold messages appear as the leitmotiv in marketing and selling male aphrodisiacs, so are sentences such as “so many beautiful women to enjoy” in this ad for Atoté in Nouchi 2.0 (see Figure 4). Designed in a variety of blue and grey colors with the outstanding yellow color for the name of the aphrodisiac, this e-commerce flyer features a gym with exercise equipment as the setting for its narrative. The muscular male figure wears a tight blue t-shirt and holds a water-like bottle of Atoté in an alluring manner, complete with his head tilted to the side and a smile on his face. This particular composition of the poster elicits visual pleasure in both male and female audiences. The stimulating drink, which is featured twice on the poster, both in the male model’s hands and on the forefront band of the poster, targets those who work out and consume the pleasure-enhancing drink. The usual close association of sports with sex is prominently featured in this ad. The difference between the advertisement of a water brand and that of a sexual stimulant resides in the name on the bottle and the tagline: Boisson naturelle, “De petites gouttes de Atoté pour stimuler le nerf. Tant de belles femmes à enjailler… (Natural drink: Little drops of atoté to stimulate the nerve: So many beautiful women to enjoy…[my translation])”. “Stimuler le nerf (stimulate the nerve)” alludes in sophisticated ways to an erection. That sophistication is elided by the unequivocal tagline “so many beautiful women to enjoy,” which privileges male pleasure and identifies women as the objects of male desire and satisfaction.

Figure 4. E-commerce advertisement for Atoté Boisson naturelle [“natural drink”]. Slogan: “De petites gouttes de Atoté pour stimuler le nerf. Tant de belles femmes à enjailler…” [“Little drops of atoté to stimulate the nerve/muscle: So many beautiful women to enjoy…”] (my translation). Screenshot from Nouchi2.0, March 2017. Credit: Nouchi2.0.com

The names of the manufacturers and their countries of origin are an integral part of the marketing approaches. Unlike sellers of the past who did not appropriate titles, current retailers and manufacturers use authoritative titles, including those of doctors and professors. Undoubtedly this self-naming aims at inciting confidence in the buyer and at building trust in the brand. One such maker is Dr. Zoh, whose physical location is in the popular market of Belleville, Treichville (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Dr. Zoh Cosmetique store in the Belleville market. Treichville, Abidjan. Côte d’Ivoire, March 2017. Courtesy of Sia Kambou, AFP for lexpress.fr

Known as “Dr. Zoh,” the manufacturer and retailer and its store and brand offer botcho creams, sexual enhancers, and fat-burning items. On his Facebook page, his products are described in this manner:

Botchocream is a natural body beauty product, made from natural roots and herbs. its herbal and free form [sic] side effects.

-

1. Botcho Cream for bigger hips and ass

-

2. Bazooka for penis engagement/length

-

3. Breast firm/enlarge/lift [sic]

-

4. Flat tummy cream

Known as the original maker of the botcho cream, Dr. Zoh initially sold cosmetics, which catered to an enthusiastic female clientele. Today, his notoriety and ambition exceed the confines of his Belleville store, as he has enjoyed a sustained digital presence on e-commerce sites such as Jumia and a large social media following. On Instagram, he has close to eight thousand followers with 531 posts, and his Facebook page is followed and liked by more than 3000 accounts. Dr. Zoh has also been the subject of news reports and YouTube interviews with clients who are supposedly from New York and other states in the United States.

The Dr. Zoh title is a marketing ploy, as he holds no degree in pharmacy, medicine, or chemistry. On one of his Facebook pages, he admits “I am Dr. Zoh, specialist of miracle pomades, BôtchôFootnote 11 et Bobaraba. I hold no degrees from Harvard and not even from the Université de Cocody-Abidjan.”Footnote 12 In YouTube interviews, his answers betray a limited knowledge of the French language. However, the design of his logo (see Figure 6) demonstrates his professionalism and aspiration to build a global brand using a product that many consider nothing more than a simple gimmick.

Figure 6. Dr. Zoh’s logo. Screenshot from Facebook.com, January 2022. Credit: Facebook.com

A 2013 report by the Chinese news organization Xinhua noted the reckless appropriation of authoritative titles and the failed attempts of the Ivorian board of physicians to hold the merchants to account. The report’s criticisms were about packaging, dubious brand names, and unproven claims about the products’ efficacy, as well a lack of information on their possible unwanted side effects. Albeit cogent, these criticisms stayed within a negative logic with the use of qualifiers such as reckless. Indeed, framing the design of the packaging as uniquely risky and nothing else (such as, for instance, sophisticated) strengthens the disabling narrative about the hypervisibility of sexual images and scenes, a trend that this essay seeks to complicate.

Professionalization of the packaging in terms of the maker’s photo, credentials, address, and medical seal is also an advantage that tends to increase commercial success and brand recognition. For instance, the bottle of Attoté male aphrodisiac drink on Amazon fulfills several of these marketing principles: a photo of the maker, Ouattara Djakaridja, and his physical address, as well as the medical seal, which establishes the product’s purported legitimacy with regard to pharmaceutical and medical approval. The product description (see Figure 7) reads “ATTOTE MEN POWER BEDROOM ATOMIC BOMB, NEW BOTTLE SAME QUALITY.” Although written in less than perfect English, the tagline’s font, straightforwardness, and bombastic appeal indicate the compelling deployment of a well thought-out marketing plan. Like the packaging for other similar products, this one displays the medical seal to encourage trust.

Figure 7. Product description of Attote sexual supplement. Screenshot from Amazon.com, October 2019. Credit: Amazon.com

Moreover, like other manufacturers and retailers, Ouattara adopts creative methods of providing convoluted directions to his physical location, in an attempt at distracting the purchaser from his lack of formal physical addresses. The bottle features such directions and contact information as mobile phone number and email address: “Producteur, Ouattara Djakaridja à Korhogo, République de Côte d’Ivoire, Points de Vente: Siège social d’Attoté, sis Quartier terrain gravé Korhogo (Manufacturer, Ouattara Djakaridja from Korhogo, République de Côte d’Ivoire, Salespoints: Attote headquarters, located in Neighborhood terrain gravé Korhogo [my translation])” (see Figure 8). But again, the inclusion of the address indicates the seller’s sophistication in legitimizing his product, in an attempt to instill confidence in his clients, aspects that deserve granular investigation.

Figure 8. Address and medical seal of Attoté sexual supplement. Screenshot from Amazon.com, October 2019. Credit: Amazon.com

Conclusion: Homines Economici

Attention to visuals indicates that the marketization of the promise of erotic pleasure, along with the search for and satisfaction of pleasure, constitute economic transactions. The buyers of such pleasure-enhancing or body-enhancing products as Baracuda, Attoté, iPhone X, or Bobaraba are quintessential homines economici. The young woman who buys Bobaraba is not a mere victim of political and social processes or a simple passive consumer; she is sensitive to packaging and brand, and her active participation in the contract leads retailers and makers to orchestrate a coherent marketing campaign for her attention and money. She is rationally investing in the promises of sensual pleasure, financial reward, emotional gratification, greater intersubjective intimacy, and an accomplished sense of femininity. She is both an active consumer and a producer of her own satisfaction, based on the capital that she has at her disposal. This investment in pleasure and enhanced body parts is calculated to yield dividends in multiple domains in which risk-taking becomes a vital market value. My reformulation of this buyer diverges from the normative approach of the commentators and the epidemiological approach, which considers the customer to be a victim of some ontologically untrammeled sexual drives that can only find satisfaction in consuming Attoté or Bobaraba. In sum, these rational economic actors engage in self-management, risk-taking, and competitive profit-making.

Acknowledgments

This analysis is indebted to the generative conversations at the April 2017 conference, “Pleasure and the Pleasurable in Africa and the African Diaspora,” organized by the late and beloved Tejumola Olaniyan at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. My thanks also go to the two anonymous reviewers, to Malam Olufemi Taiwo for thinking with me, Nidhi Mahajan for her comments, and to my research assistants in Abidjan, Adjara Diabaté, and Djakaridja Fofana.