Constable Robert Simpson: During the period I was there I did not see any civilians throwing stones.

Lord Scarman: But your camera did.

Simpson: Oh yes, I probably did, but as I say I did not see it; my camera was held above my head.Footnote 1

On 12 August 1969, Constable Robert Simpson had been assigned the task of photographing criminal behavior in Londonderry for future prosecution.Footnote 2 However, as the day progressed and violence between nationalists and the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) intensified, he found it harder and harder to get clear shots of protagonists. Instead, he resorted to taking general photographs of the unfolding riot for illustrative and contextual purposes. Moving up William Street with a crowd of RUC and civilians, he was unable to see anything at all. Instead, he lifted his camera above his head and aimed it in the direction of the noise and movement in front of him. The blurred and crooked photograph that resulted showed a crowd, a building, and some broken windows. During the subsequent tribunal that investigated the violence, the significance of this image was contested: Lord Scarman believed it showed unionist rioters stoning the windows of the nationalist Rossville Flats, whereas Simpson attempted to refute this interpretation by instead asserting that he had not actually seen what was in front of him as he took the photograph and so could not authenticate what the image purported to show (Figure 1). The photograph—and the story Simpson told about how he came to take it—was only one of hundreds scrutinized by the tribunal. Indeed, the exchange between Scarman and Simpson is indicative of the complex and contingent processes through which images of violence were produced, how they were used to make sense of civil disorder, and the problems and possibilities they contain for historians.

Figure 1 Rossville Flats, 12 August 1969 (Robert Simpson). Image courtesy of the Chief Constable of the Police Service of Northern Ireland.

From the late 1960s, Derry's streets were increasingly the backdrop to marches, riots, and violence. Catholic demands for housing, jobs, and equal rights were often met with heavy-handed responses both from unionist civilians and security forces. Loyalist and republican paramilitary groups increasingly organized and came into conflict, while the government in Stormont oscillated between force and reform.Footnote 3 Throughout the summer of 1969 there were fractious exchanges between communities and the police in the city: these reached a crescendo in mid-August, when three days of rioting, remembered as the Battle of the Bogside, followed the Protestant Apprentice Boys parade. In subsequent days, street protests spread to cities across Northern Ireland, leading to massive displacement of people, the destruction of property, and the deployment of the British Army.Footnote 4 However, even as Scarman investigated the causes and events of this summer of unrest, events were overtaking him, relations between communities and the security forces were worsening, and paramilitary groups were growing in strength and organization. With the introduction of internment during the summer of 1971, attacks on both people and property only increased, with a large part of Londonderry becoming a no-go area for British security forces. On 30 January 1972, journalists and photographers were back in the city for a banned civil rights march. In the late afternoon, thirteen civilians were shot dead by paratroopers, while another fifteen were wounded; “Bloody Sunday” became the most famous day of the Troubles, and was an important moment of radicalization for Northern Ireland's Catholic community.Footnote 5

The British government responded to these moments of crisis by implementing a series of inquiries. On 27 August 1969, Lord Scarman was appointed to lead an inquiry to ascertain the facts of the Battle of the Bogside, the Burning of Bombay Street, and other disturbances across the province during that year. The tribunal sat for more than three hundred days between 1969 and 1972; the testimony of its 440 witnesses provided a revealing and detailed picture of a society on the cusp of transformative change. In contrast, the inquiry into Bloody Sunday was much more narrowly focused and reached its conclusions more quickly. Facing outrage across Ireland, on 31 January 1972 the prime minister, Edward Heath, appointed Lord Chief Justice John Widgery to lead an investigation to determine the circumstances of the civilian deaths. The tribunal soon became another area of grievance for Derry's Catholics; in its scope and conduct the process frequently gave more consideration to the needs of the army than the victims and relatives of the dead. Moreover, its findings—that soldiers were fired upon first and shot only at suspected gunmen, and that some of the dead had been handling firebombs or guns—was read as a second act of violence towards the already traumatized community of the Bogside. As Dermot Walsh has observed, the inquiry had “a devastating effect on nationalist confidence in the rule of law and the integrity of the state. If they could not depend on the judicial arm of the state to deliver justice when they were shot on the streets en masse by British soldiers, why would they withhold support from those within their community who would use force of arms in an attempt to overthrow that state?”Footnote 6

Despite the impact of these tribunals on the direction of communal relations and policing, scholarship has tended to focus on their final reports, with less emphasis on how they functioned and used evidence in order to come to their conclusions. Historians have tended to reproduce—often verbatim—the findings of the Scarman tribunal as the narrative of the three days of riots in August.Footnote 7 However, the findings of the Widgery Report were, from the day of publication, far more controversial. While Widgery's conclusions were generally accepted as fact by the British media and establishment, residents of the Bogside and their allies worked hard to overturn the report and have their account of the day known and accepted. Indeed, a large number of witness accounts of Bloody Sunday were published, including Fulvio Grimaldi's Blood on the Streets (1972) and Simon Winchester's In Holy Terror (1974), while Samuel Dash's Justice Denied: A Challenge to Lord Widgery's Report on “Bloody Sunday” (1972) attempted to provide a legal counterweight to Widgery's version of events.Footnote 8 Since then, a large body of scholarly work by historians, including Graham Dawson and Dermot Walsh, has successfully picked apart the failings and injustices of Widgery's investigation. Moreover, after years of campaigning by victims and the families of the deceased for a new tribunal, the twelve-year Saville Inquiry (1998–2010) provided a remedial process and an account that is now widely accepted as the definitive version of the day.Footnote 9 Indeed, as shown by Tom Herron and John Lynch, the uses of virtual technologies during the Saville Inquiry reshaped the ability of victims, relatives, and legal representatives to discuss events.Footnote 10

Focusing on Londonderry, this article returns to the early Troubles to compare how photographs were used at the Scarman and Widgery inquiries. In so doing, I foreground the material and social dimensions of photographs in order to unite close critical readings of images with an exploration of how they were understood and circulated contemporaneously.Footnote 11 I examine the role that photographers—amateur, professional, police, and army—played during these episodes of intensified violence, and how their photographs came to be presented as evidence in the tribunals. Using the papers and minutes of the Widgery and Scarman tribunals, I then explore how these photographs were handled as evidence and how they were used to frame causal narratives of violence and civil disorder. A close reading of the minutes of the tribunals shows how the existence of certain photographs served to anchor discussions of trajectories of violence around certain places and moments, how photographs taken for publication in newspapers were reread as evidential documents, and indicates how each photograph provided a range of plausible truths. Indeed, the power that photographs had was always contingent, circumscribed, and produced through the complex interplay of their social, material, and visual dimensions. Through an examination of the differing uses of images at the two tribunals, I seek to explore the relationship between an image's production, how its claims to truth were understood and validated, and the uses that photographs had in underpinning state-sanctioned histories of the events of the early Troubles.Footnote 12

Foregrounding these photographs provides a new way into histories of Northern Ireland during a transitional phase in its history. The Troubles produced a large quantity of journalistic and artistic photographic responses, with photographers such as Eamon Melaugh, Don McCullin, and Willie Doherty playing an important role in shaping the visual economy of the conflict.Footnote 13 These photographs have received extensive treatment by art historians and cultural critics as straddling traditions of social realism and war photography—as part of a genre of “combat photography that the public had been accustomed to since the Korean and Vietnam wars.”Footnote 14 The use of photographic evidence during the original tribunals of the late 1960s and early 1970s has been largely unstudied; however, there is much to be learned through a close examination of the processes through which these tribunals functioned and practices through which “truth” could be identified, ascertained, and embedded. First, this close reading of the uses of photography at these landmark tribunals shows how archival material relating to the history of the Troubles provides a view of the past that is partial and that was highly politicized even in the way it was amassed. Second, scholarship on the Troubles has tended to combine a focus on the politics of the street with discussions behind closed doors in Stormont and Westminster, without a critical eye on the processes that linked these places. Following John Tagg's examination of the relationship between the state and photography, I examine this question by exploring photography as a crucial part of the technologies of state that joined the Bogside and Westminster in order to explore the instruments through which the citizens of Northern Ireland were quantified, described, and made visible.

I do not seek to provide a new account of the Battle of the Bogside or Bloody Sunday or reappropriate blame. Rather, this study shows the importance of exploring the processes and mechanisms through which the state made sense of Northern Ireland to understand how causal accounts of conflict were produced and authenticated—and how, in turn, those explanatory regimes shaped the policies of the British state, and the responses of local communities, and became embedded in historical writing on the Troubles. The emergence of violence was understood, truth claims were constructed, and the actions of the state and the security forces were validated through a complex nexus of personal testimony, the demands of the national press, photographic epistemologies, and judicial procedure. However, the difference between the ways photographic evidence was handled at the Scarman and Widgery tribunals is also indicative of how these factors could be instrumentalized in very different ways. At the Scarman tribunal, photographs provided a starting point for many memories of the Battle of the Bogside to be discussed and evaluated, with the mutability of photographs allowing witnesses to provide many conflicting, yet equally plausible, readings of the same evidence. Nevertheless, the inquiry needed to find a post facto validation for the deployment of the British Army. Photographs that purported to represent Catholic violence, alongside images that showed the RUC unable to restrain Protestant gangs from the Bogside, were central to the inquiry and to how the story of the three days in August was constructed. In contrast, Widgery's aim was to display the culpability of those who died. To do so he capitalized on the photographic emphasis on the dead and injured; Widgery used photographs originally taken to emphasize the emotive horror of events on the streets of Derry to seek out instead weapons in the hands of those shot by the British Army. At the tribunals, photographs, which drew on various aesthetic conventions, and which had been assembled through a range of commercial conduits, were scrutinized in very different ways. Despite this, Scarman and Widgery both produced final reports that flattened these processes and ambiguities into one fixed, official, narrative. These photographs were co-opted by the state to reinforce its seeming objectivity, the rectitude of its policies, and inversely, the irrationality of Londonderry's Catholic community.

BATTLE OF THE BOGSIDE AND THE SCARMAN TRIBUNAL

On the morning of 12 August 1969, the Protestant Apprentice Boys walked out from St. Columb's Cathedral through the city of Londonderry, retracing their steps, and the steps of their fathers, in marching around the city to commemorate the lifting of the siege on Derry in 1689. However, while the suits, sashes, and music echoed what had gone before, by 1969 the city had changed. A combination of housing shortages, unemployment, a civil rights movement at home, and global protests on television had radicalized the Catholic community, and violence was becoming increasingly frequent. The morning had been characterized by low-level disturbances between groups: some Apprentice boys tossed coins from the city walls onto bystanders below, while at around 2:30 p.m. Catholic onlookers threw nails at police, followed by stones. “From this small beginning,” as Thomas Hennessey puts it, “developed a riot which enveloped the city for two days and nights and which became known as the Battle of the Bogside.”Footnote 15 Rippling out from the Bogside, violence spread across Northern Ireland. The impact of these events for both Ireland and Britain cannot be understated. These riots led to hundreds of injuries, nine deaths, the burning of large areas of residential Belfast, and the displacement of more than two thousand people from their homes. These disturbances ended only when the British Army was deployed to the streets of Belfast and Londonderry—heralding the beginning of Operation Banner, the single longest continuous deployment of the British Army.Footnote 16

There were many different types of photographer in Derry during the days of violence in August—for example, Robert Simpson, the RUC photographer; James Gibson O'Boyle, a photographer with an American newspaper; and Bernard McMonagle, a resident of Bogside, all took photographs that appeared before the tribunal. Indeed, Scarman estimated that there were approximately 200 to 300 pressmen in Londonderry on 12 August, present in the city only to record the anticipated disturbances.Footnote 17 These photographers played an important role in creating an atmosphere of tension they sought to record. Many testimonies given at the Scarman tribunal record the city as a site not only of violence, but also spectacle—accompanying every crowd throwing stones there was a second crowd observing and recording events.Footnote 18 For example, O'Boyle's “first hint . . . of any kind of trouble” was when he was taking pictures of the parade in front of the City Hotel and “half a dozen or so of the reporters went galloping by with their equipment yelling at me that it had just started down at Waterloo Square.”Footnote 19 However, these photographers also became subject to attack themselves. O'Boyle reported that he “was accosted by crowds” in Little James Street, “stone throwing, threatening to smash the camera, shoving you around, threatening to hit you.”Footnote 20 Bernard McMonagle described the cameramen as “a target for everybody these days . . . sometimes I would be stopped by the police and sometimes stopped by people in the Bogside.”Footnote 21

The RUC interpretation of the Battle of the Bogside was put forward by Constable Robert Simpson, who presented a book of fifty-seven photographs of the events of 12 August to the Scarman tribunal. His role as a police photographer was to be present at the scene of violence in order to take photographs of “persons engaged in crime for identification purposes.”Footnote 22 His photographs included images of the crowd watching the Apprentice Boys' parade, a petrol bomb exploding, men throwing stones, and women and television crews watching events from doorways. Several of the photographs retain the marks of their disciplinary function: many of the images have the faces of stone throwers, and even those engaged in minor acts of dissent, such as pushing over crash barriers, ringed and identified.Footnote 23 In taking these photographs, Simpson shaped how the disturbances on the streets of Londonderry were recorded and understood. From the images he submitted to the tribunal, it is clear that Simpson hid behind police lines, focusing his gaze on the Catholic crowds who confronted him, showing only the backs of RUC officers and excluding acts of violence towards the Catholic community from the image frame. For example, Simpson's photograph No. 23, taken in Rossville Street, shows a crowd in the distance, while No. 24 shows a group of young men seemingly rioting in isolation—the targets of their stones and any other crowds they were interacting with remain unrecorded (Figure 2). Indeed, the effect of Simpson's positioning on how he recorded events can also be seen with regard to his photograph 57 (discussed above). Moving as part of a crowd of RUC and civilians as they entered the Bogside, he was unable to get a clear enough view to record acts of vandalism and assaults against residents of the area.

Figure 2 Crowd in Little James Street, 12 August (Robert Simpson). Image courtesy of the Chief Constable of the Police Service of Northern Ireland.

Many Catholic witnesses called before the tribunal refused to cooperate with the RUC's uses of visual evidence, and in the process suggested the presence of other perspectives on scenes of violence. When Eddie MacAteer, the former Nationalist MP for Derry, was shown photographs of stones on the ground, he pointed out that there was nothing to prove whether these had been thrown by Catholic youth or by Protestant crowds at the Catholic crowd.Footnote 24 Eamon Melaugh, who went on to be one of the most famous photographers of the Troubles and a high-profile Catholic activist in Londonderry in the 1970s and 1980s, used his knowledge of photography to attempt to subvert the state's power as personified by the RUC photographer. Asked if Simpson's photograph No. 7 showed a man throwing a stone at the Protestant procession, he replied, “Well, it could be, yes. You could get that impression. You could also, if you look at the photograph quite closely, get the impression that he was watching a missile coming in his direction and was going to take evasive action.”Footnote 25 Pushed again to concede that this man was throwing a stone, he went on: “I would reluctantly agree although, my Lord, I am somewhat of an expert on photographs, a very keen amateur photographer, and I can assure you that still photographs can give the wrong impression.”Footnote 26 He also tried to push against the logic of these RUC photographs in other ways. On several occasions, when asked to identify people in the photographs, he claimed to “know them, but I do not know their names,” despite the small and close-knit nature of the Catholic community in the Bogside.Footnote 27 Seán Keenan, chairman of the Derry Citizens Defence Association, took a similar tactic when dealing with images presented to him, answering “I have seen him around” and “could be somewhere around there” to questions about several people's names and addresses.Footnote 28 Indeed, he failed to recognize a single person from Simpson's fifty-seven photographs.

These RUC images of rioters were also interrogated by photojournalists who took their photographs from alternate viewpoints, thereby foregrounding violence towards the residents of the Bogside. Two photographs submitted as evidence by Father Mulvey, the Catholic priest for the area, caused considerable controversy and were the subject of intense debate at the tribunal.Footnote 29 The first image, labelled Exhibit 6, showed a crowd of men, some in the uniform and helmets of the RUC and some in suits, clambering across a barricade. The scene was dominated by a billboard advertising Guinness, declaring jarringly, “The Most Natural Thing in the World” (Figure 3). The second photograph, Exhibit 7, showed another mixed crowd of darkly clothed men, running away from the camera up a street with a high building on the left. For Mulvey, there was a looming sense of determinism about events of the Apprentice Boys' march, which the photographs both contributed to and reinforced. Although Mulvey had not been present at the time the photographs were taken, they showed that what he had “expected to happen” and “feared might develop” had occurred: “these photographs reveal the police in riot equipment moving into the Bogside area accompanied by a certain number of civilians some of whom are throwing missiles.”Footnote 30 Moreover, Protestant civilians and police were acting together in entering the Bogside.Footnote 31 Mulvey told Lord Scarman that the events “portrayed in these pictures” were critical to his “assessment of these riots.”Footnote 32 Indeed, these images have had a continued impact on historical understandings of the Battle of the Bogside. Mulvey's comment that “I would only regard it as a community revolt rather than a street disturbance or a riot” was quoted in the final report and has been frequently reproduced by historians.

Figure 3 RUC entry into the Bogside, 12 August 1969 (James Gibson O'Boyle).

These photographs had been taken by James Gibson O'Boyle, a photographer with the Pottstown Mercury, a newspaper based in Pennsylvania. O'Boyle had been on his way to Israel in the summer of 1969 but had changed his plans and traveled to Londonderry when he heard news of the violence in the city. Wholly converted to the cause, a few days after the Battle of the Bogside he abandoned his camera and took an active role in the defense of the Catholic areas of the city. O'Boyle saw himself as a photographer-adventurer; during the inquiry he prefaced his discussion of his photographs by recounting how he had climbed on to a shed with five or six other photographers on the corner of Rossville Street between 6.30 p.m. and 7:00 p.m. on the day of the Apprentice Boys' parade.Footnote 33 He described the scene:

Suddenly there was this breakthrough and as the first people of the crowd started to run I looked round sort of frantically and the one police armoured car drove across and I suddenly saw these civilians there and started taking pictures—these are some of them. I took some pictures and as the police charged by I started to focus again on the civilians. It was almost exclusively civilians who were tearing down the barricade.Footnote 34

When the crowd started to stone him and the other photographers on the roof he had to jump off, but the pictures he took before this played a definitive role in forming the tribunal's line of inquiry regarding the police entry into Rossville Street. He described Exhibit 6 as showing “the police charging from William Street and Little James Street across the barricades erected at the foot of Rossville Street, and police and civilians charging behind the armoured car in the first photograph.”Footnote 35 He told the tribunal that if the photograph could have been extended to the right “there would be the crowd from the Bogside running in front of the two armoured cars and there would be also some police and some more civilians—quite a few more civilians.”Footnote 36 Exhibit 7 showed “more of the police charge and civilians throwing stones through the windows of the flats on the right hand side of Rossville Street, facing in.”Footnote 37 The events presented by O'Boyle's photographs were corroborated by Bernard McMonagle, a control mechanic and amateur photographer, who ascended to the fourth floor of the high flats on Rossville Street in order to record the baton charge by the police towards the Bogside.Footnote 38 He told the tribunal, “No. 1 was the very first photograph I took on the evening of the 12th approximately about a quarter to seven, around that, and in it you will see the first wave of police coming towards the Bogside and in amongst them you will see a lot of civilians and particularly there is one there throwing stones towards the windows of the low maisonettes. There was no attention paid to him at all.”Footnote 39

The RUC officers interviewed resisted the interpretation of events presented in these photographs. They privileged their own memories and experiences above the images captured by O'Boyle, and they used their testimonies to shore up the version of events presented by Simpson. County Inspector G. S. McMahon agreed that Exhibit 6 indicated that the police must have been aware of the presence of civilians, but the photograph did not show other important information necessary to assess the scene, including what was “in the immediate front of the police.”Footnote 40 McMahon's reflections on the reality presented by the image provide an echo of Stanley Cavell's observation that “What happens in a photograph is that it comes to an end . . . When a photograph is cropped, the rest of the world is cut out. The implied presence of the rest of the world, and its explicit rejection, are as essential in the experience of a photograph as what it explicitly presents.”Footnote 41 McMahon's acceptance of the image was not typical of RUC officers interviewed. Head Constable Thomas Fleming used the picture's aesthetic and compositional qualities to throw doubts on its authenticity, stating, “this gives a very beautiful picture.” But he could not “relate that photograph to 7pm on 12th October [sic].”Footnote 42 In so doing he drew on perceptions, explored by Susan Sontag, that within documentary traditions, the “taint of artistry” is “equated with insincerity or mere contrivance.”Footnote 43 Indeed, many of the RUC officers involved in the operation on 12 August also used the position and materials of the barricade in order to debate the veracity of the photograph. Sergeant Henry Pendleton stated, “this barricade was not of this structure at all. At no time did I see what you see in Exhibit 6.”Footnote 44 District Inspector Kenneth Cordner thought, “the fact that the barricade does not appear to be the barricade I went over and the Land Rover is not in position, the armoured car is not in position, there were no police behind it like that, that does not represent what I saw.”Footnote 45 Of particular significance, in his recollection “there were no civilians at Meehans, there was not a soul in that street except police—not a living soul except police.”Footnote 46

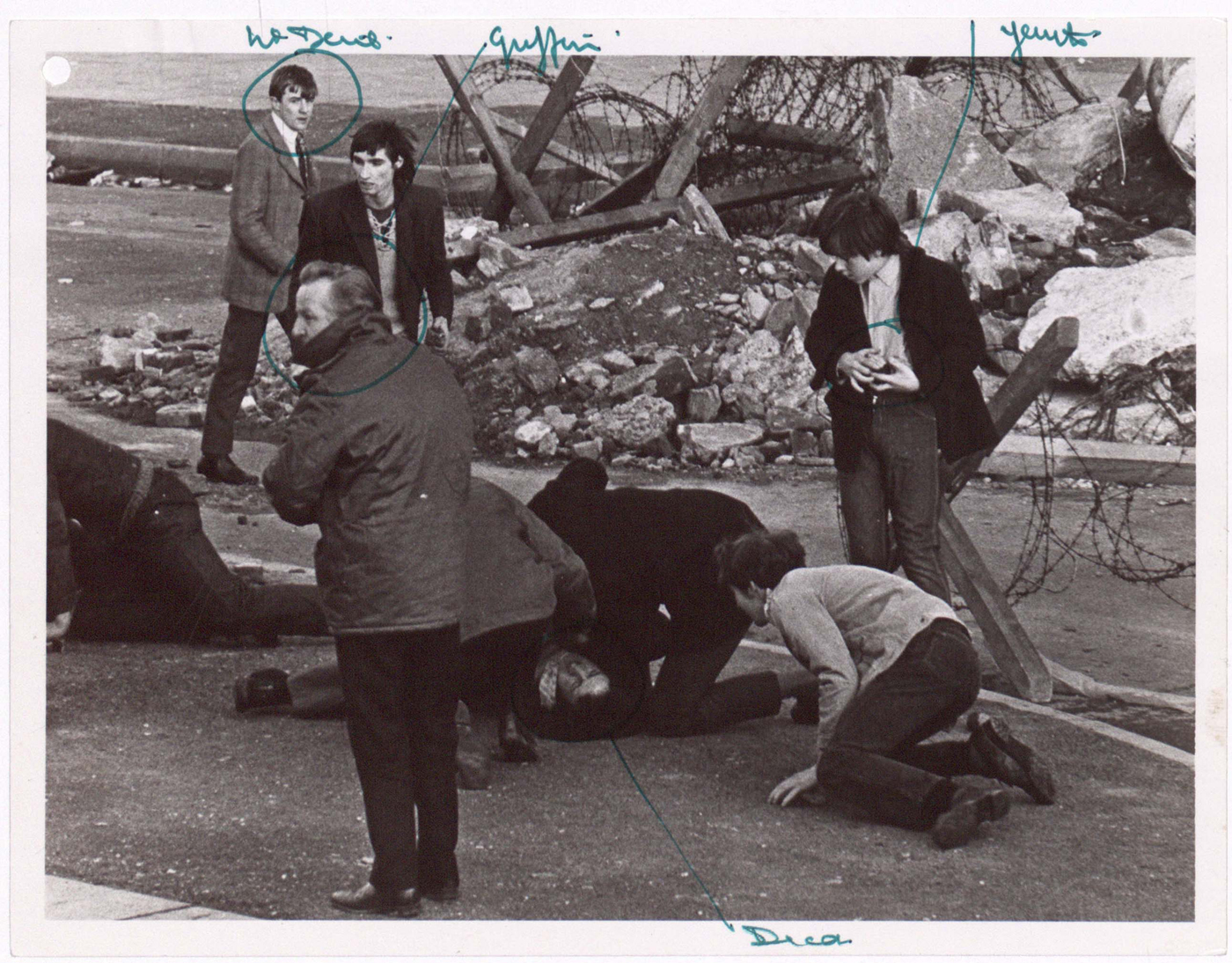

Some of the photographs presented before the tribunal showed things that could not be corroborated or remembered by any party. While hearsay, or secondhand oral evidence, was immediately dismissed by Scarman as having no validity within the court, there was no framework for dealing with similar problems with photographic evidence, which were instead handled uneasily by witnesses and barristers alike. One of the most contentious images debated at the inquiry was a photograph showing a group of policemen in the foreground with their backs to the camera, being stoned by a group of young men located in the background of the photograph (Figure 4). On the right-hand side, there was what appeared to be an older man, in a sports coat and felt hat, pointing a gun at the police officers. The existence of the man on the right aiming the firearm was crucial; it was “one direct piece of evidence of a firearm in the hands of a Bogsider during the August riots.”Footnote 47 But this photograph revealed the conflicting and problematic nature of photographs as sources. It was taken by Kenneth Mason, a photographer attached to the Daily Telegraph and Morning Post, and first appeared in the Sunday Times on 17 August. Called to the witness box, Mason attested that the confrontation the image depicted had lasted less than a minute.Footnote 48 Indeed, when he took the picture he had not seen “any figure in the vicinity of that buttress.”Footnote 49 He became aware of the figure while he was taking the next shot and then he moved further to the left to try to get a clearer image of the man with the gun. Mason had some experience of guns; he told the tribunal that the man was handling the weapon “A little nervously I would say—not used to firearms.”Footnote 50 However, he never saw him fire the gun.

Figure 4 Columbcille Court, 13 August (Kenneth Mason). Image courtesy of the Times.

None of the policemen who had been present in Columbcille Court remembered the figure by the wall being in possession of a gun. Constable Ian Forbes, who was in the foreground of the image, remembered seeing the man during the incident, but not at the wall, and not with a firearm; rather, he remembered the figure among the group throwing stones. Constable Thomas McLaughlin, the policeman on the extreme right of the photograph, also observed the man in the middle of the crowd throwing stones.Footnote 51 District Inspector F. I. Armstrong, the officer in charge of the police in this area on 13 August, had received no reports from any of his men of the presence of a gunman or to the existence or use of firearms in Columbcille Court.Footnote 52 Despite the dissonance between the photograph and the policemen's memories, this image took on a central importance in the inquiry regarding events in Derry, as the presence of the figure with the gun validated the explanations provided by members of the RUC that they had responded legitimately and proportionately to the threat of an Irish Republican Army (IRA) rising in the Bogside. Indeed, several RUC officers attempted to reconcile the photograph with their memories. Armstrong stated that “that man could actually be there with a gun and none of them have seen him” due to the way in which photographs simplified complexities of movement, sound, depth, and time into a single, readable image: “it is very easy, looking at a photograph, to study it and say why could not, or why would not, they have seen them, but if that were a moving picture it is an entirely different set up, particularly when you have got to watch the stones and we were watching stone throwers all the time. When watching people in action, anybody standing you would not notice.”Footnote 53 Indeed, McLaughlin, Forbes, and Constable Albert Neill all remembered having a gun pointed towards them from a different vantage point while in Columbcille Court; McLaughlin attested to the presence of “a youth on top of the small flats and he had, to me it was a rifle, and several times he was sighting it down the gap there towards the police from the top of the flats.”Footnote 54

As this discussion suggests, at the Scarman tribunal, photographs submitted by journalists, residents, and the RUC were co-opted into the judicial process and became loci of debate regarding the course of events. These images served to focus discussion on a series of moments that had been depicted photographically, while various competing readings of events were discussed and assessed. The range of plausible interpretations was bounded by the limitations of photographic technologies, alongside the visual tropes of street fighting and urban protest employed by photographers who were working within the demands of the market in images. This had particular repercussions with regard to the framing of Catholic violence as the activity of the “hooligan” and the “mob.” This language was a key element of the vilification of the Catholic community's responses to the police and the military; as Stuart Hall pointed out in 1973, this way of framing urban disorder was a key part of the de-politicization of violence on the streets of the United Kingdom.Footnote 55 For example, Lord Scarman described Exhibit 7 as showing “what I will loosely call the Bogside mob in the distance,” while District Inspector Armstrong described the photographs taken in Columbcille Court as taken when they were attempting to “drive the mob back who were throwing petrol bombs.”Footnote 56 These discourses were constituted and reinforced by the way these manifestations of urban disturbances were visualized through photography. The descriptive categories of the “hooligan” and the “mob” were reinforced by the Catholic community appearing in the background—as a mass—in many of the photographs taken, placed in this position by photographers who inevitably hid behind police lines, and homogenized by distance and focal depth. Indeed, it is notable how little effort was made to identify participants in many of the photographs shown. This way of seeing a crowd took on a crucial importance during Bloody Sunday, when, as Tom Herron and John Lynch have described, “the British authorities set out to confront, in their terms, a faceless crowd, an indiscriminate mass of Derry Young Hooligans/yobbos/terrorists, organizers of, and participants in, a march that challenged the authority of the state to intern members of the nationalist community without trial and to contain a community within its defined boundary. On that day all of those marching, regardless of their political affiliations, motivations and reservations, were simply a ‘crowd.’”Footnote 57

BLOODY SUNDAY AND THE WIDGERY TRIBUNAL

On 5 February 1972 a RUC officer traced a route around the walls of Londonderry city, taking photographs of the Bogside below. The photographs he took record an almost ordinary day in suburban Northern Ireland in 1972: boys playing football, a man washing his car, and women in headscarves carrying bags of shopping home from town (Figure 5). The mixture of maisonettes, newly built houses, Victorian terraces, and derelict cleared sites also located the photographs within the specific urban geographies of the postwar settlement. But even a cursory inspection shows that violence was only just beneath the surface of this urban scene. Gun placements, sandbags, and burned-out cars formed part of the street furniture alongside streetlights, postboxes, and benches. There were few people present on the streets; indeed, the photographs reveal an uneasy sort of calm on the streets of Derry.

Figure 5 RUC photographs 5 February 1972 (photographer unknown). Image supplied under the Open Government License.

Six days before these photographs were taken, thirteen men had been shot dead and another fifteen wounded by members of the First Battalion, the Parachute Regiment, during a civil rights march on these residential streets. Contrasting and conflicting versions of events started circulating immediately; spokesmen from the Bogside described how the Paratroopers had shot indiscriminately, while the army claimed that the soldiers had opened fire only when fired upon.Footnote 58 In the subsequent days, these rival versions were challenged and reinforced by images of Derry that were disseminated around the world. The photographs taken by Gilles Peress, a French photographer with Magnum, appeared in Life magazine. Stephen Donnelly's photographs appeared in the Irish Times. Robert White's image of men at the barricade appeared in the Sunday Independent and in the Londonderry publication Republican News.Footnote 59 The subsequent tribunal, led by the Lord Chief Justice John Widgery, conducted seventeen public sessions between 21 February and 14 March 1972, in which it heard 117 witnesses, including priests, press and television reporters, photographers, cameramen and sound recordists, soldiers, police officers, doctors, forensic experts, pathologists, and “other people from Londonderry.”Footnote 60 Twenty-one pressmen were interviewed by Widgery. As many participants in the march and residents of the Bogside either were not called or refused to participate in the inquiry, these pressmen often played a crucial role in putting forward the perspective of those critical of the army. The Scarman and Widgery reports were both published in April 1972; yet despite the proximity of these two inquiries, it is notable how differently photographic evidence was used at the Bloody Sunday inquiry, reflecting a range of factors, including the differing personalities of those adjudicating, the upsurge in violence in the province, and the different genre of photographs scrutinized.

Derrick Tucker was the only Bogside resident to have his photographs examined as part of the tribunal. From his bedroom and living room in the high flats he had been able to see down Chamberlain Street to William Street, and he had observed the crowd approaching the open ground around the Rossville Street flats. He described how the crowd had moved in “a very quiet manner; just like a Sunday afternoon stroll.”Footnote 61 He also witnessed the atmosphere deteriorate as the Saracen armored cars drove into Rossville Street and the marchers fled in front of them. Using a camera that he normally used for holiday photos, he recorded these scenes as the previously peaceful crowd ran away from the approaching military vehicles. Indeed, his were also the only color photographs submitted to the tribunal; uniquely his photographs record the colors of the cold winter sunset as the army arrived. Tucker continued to watch as the violence of the afternoon unfolded outside his bedroom window; however, his film ran out and he was unable to record what he witnessed.Footnote 62 The photographs he took that afternoon played a central role in the subsequent tribunal: Widgery described them as “the best indication I have had so far of how many people were running into the courtyard” while they were also shown to several soldiers (including Soldier V, below) as an indication that the crowd ran away—and was not aggressive—when it entered Rossville Street.Footnote 63

As Tucker ran out of film in his Rossville flat, photographers in the street below took out their cameras as the paratroopers opened fire. These photographers had a particular relationship to the violence that they recorded. Their press passes and relative distance from the scenes that surrounded them gave them an ability to move through the city and observe events that most of those who lived locally or had been on the march lacked. When Cyril Cave, a BBC cameraman, heard shots coming from the direction of the soldiers, he recounted, he “just automatically ran. They said ‘They're shooting!’ And we ran across towards where we thought the shots came from.”Footnote 64 Jeffry Morris, a photographer with the Daily Mail, described how he “looked across [Rossville Street] and saw this youth running and being challenged and I saw the paratrooper coming from behind him and I could virtually see what was going to happen, so I started running towards it to get a better picture.”Footnote 65 However, these photographers were also part of the scene they were recording; they were subjects of violence and their presence played a role in shaping how events unfolded. Peress was shot at as he walked across Chamberlain Street, and Grimaldi was shot at through a window while hiding in Rossville high flats.Footnote 66 Two paratroopers held Morris against a wall with a rifle across his neck. One kneed him in the groin when he tried to get his press pass out of his pocket, and the other hit him across the face with a rifle when he tried to take a photograph.Footnote 67

Grimaldi described how he had been surrounded by violence but had seen himself more as a spectator than a participant. He described his journey through the Bogside:

I photographed Doherty as he was dying and I photographed McGuigan as I had seen him dying. At the point I photographed McGuigan the first time there was no Saracen down in Rossville Street, there was no military presence to be seen. . . . I went further down along the front of the shops and I photographed a young man called, I believe, Gilmour, who was dead. As I stood in this place for a couple of minutes a girl was going hysterical. I photographed her.Footnote 68

Grimaldi's seemingly dispassionate photography of those in pain, injured, or dying without coming to their aid provides an example of how he focused on individuated moments of suffering and heightened emotion in his construction of the events of Bloody Sunday. For example, his photographs of Jack Duddy, the first civilian killed as he ran away from the approaching army vehicles, showed Father Edward Daly waving a handkerchief as three others carried Duddy's body; alongside the BBC footage of the same incident, it became one of the most enduring images of the Troubles.Footnote 69 Grimaldi's construction of events was matched by that of many other photographers who focused their gaze on the dead and dying rather than pictures of crowds or the army. This differed notably from images of the Battle of the Bogside, perhaps resulting from the photographers' instinctive visual response to death. Peress recorded Patrick Doherty's final moments in a series of four images as he attempted to crawl to safety under a wall bearing the slogan “Join your local IRA unit.”Footnote 70 Hugh Gilmour was shot as he ran away from soldiers in Rossville Street; the moments after he was wounded were captured by Robert White.Footnote 71 Barney McGuigan left a position of cover to attend to Patrick Doherty; despite waving a white handkerchief, he was shot almost instantly. Both Grimaldi and Peress photographed his body in the moments after he died, while men and women sheltered from gunfire in the background.Footnote 72 Michael Kelly, John Young, Michael McDaid, and William Nash all died in Rossville Street. Kelly was hit first; his body was photographed by the barricade by Robert White, a freelance photographer from Derry.Footnote 73 Michael McDaid was pictured in the background of this image in the moments before he was also fatally wounded. Gerald Donaghy, James Wray, Gerald McKinney, and William McKinney were all shot in the northerly courtyard of the Glenfada Park flats; the tribunal scrutinized no photographs of the moments surrounding their deaths (but did examine photographs of Donaghy's body—see below), nor any images relating to the fifteen people who received nonfatal gun wounds.

While these photographers focused on the emotive power of death and victimhood, Widgery's primary aim in examining their photographs was to find validation for his contention that those who had been shot had handled, or could be legitimately thought to have handled, firearms. The photographers' movement towards, rather than away from, gunfire and scenes of violence, driven by an artistic and commercial imperative for a “successful” photograph, meant that they saw themselves as well placed to offer a perspective on the presence or absence of weapons in the Bogside on 30 January. On several occasions, photographers and cameramen stated that if civilians had had guns or nail bombs they would have photographed them. Cave, for example, was adamant that he heard no automatic gunshots coming from the civilians on the barricade. He told Widgery that “if I had heard automatic fire I would probably have started the camera running to pick it up on the soundtrack.”Footnote 74 During questioning, Peress stated that he, like “any journalist,” was eager to get a photograph of a “civilian with a weapon”: taking this kind of photograph was “something that you cannot help doing.”Footnote 75 He also agreed that he would have been keen to take a photograph of “a weapon lying beside a dead man, or an injured man” or “if a weapon had been removed from a dead or injured man,” but he had at no point seen this occur.Footnote 76 Despite these assurances, the tribunal repeatedly sought weapons in the photographs presented to them by these photographers. When Peress's photograph of Duddy being attended to by Father Daly was examined by Edward Gibbens, counsel for the Ministry of Defence, the central focus of the scene was not the priest and the dying teenager but rather the object in the hand of the man crouched beside them. Gibbens told Peress that “that can be . . . a stick or it could be other things”; one of the “other things” he had in mind was a gun.Footnote 77 Similarly, when the images Peress took of Patrick Doherty attempting to crawl away from army gunfire were examined by Mr. Preston, counsel for the tribunal, Preston asked Peress why Doherty's right hand was in a different position in photographs Nos. 8 and 9 than Nos. 10 and 11, speculating that this could be because a weapon had been removed from his body.Footnote 78

Whether or not missiles or firearms were being used by Michael McDaid, John Young, and William Nash formed a central part of the inquiry's investigation of how and why they died. A copy of the Sunday Independent from 6 February 1972, with an image of the three men at the Rossville Street barricade, was submitted by Gibbens. The image showed Michael Kelly's body being attended to in the foreground; behind him McDaid had his back to the soldiers, while another man held an object between outstretched fingers (Figure 6).Footnote 79 When Stephen Donnelly, a photographer with the Irish Times, was shown the image, he thought that the object looked “like it could be a nail bomb.”Footnote 80 According to Widgery, the man had “clearly got something in his hand, about the size of an orange, and it is black.”Footnote 81 Gibbens played on the apparent resonances between the poor reproduction of the photograph in the newspaper and the confusion of violence in order to implicate the group, telling Widgery that “in suitable circumstances of security your Lordship would like to see a nail bomb”; Widgery agreed.Footnote 82 The image had been taken by Robert White, a freelance photographer from Londonderry, who had been at the barricade with another local photographer, William Mailey. Called before the tribunal, Mailey stated that he had not particularly noticed the man or what he was doing as he was taking photographs. However, Gibbens presented him with a particular interpretation of what it showed: “he is obviously holding some object in a very ginger fashion, is he not, between his extended fingers . . . do you know that nail bombs are about the size of what he is holding?”Footnote 83 Mailey resisted this reading of the photograph and replied, “I had a quick glance over at what was happening and obviously I did not want to get involved. Had there been any guns or nail bombs I would not have stayed on the barricade, I had a look, they were simply throwing stones and I felt reasonably safe as long as I moved right out of their way.”Footnote 84 Despite Mailey's testimony, and the absence of a positive identification of the man or the object, in the final report of the tribunal Young and Nash were said to have probably discharged firearms.Footnote 85 The line of questioning regarding the men on the barricades, Doherty, and the man with Duddy shows how Widgery and his team of barristers pushed against the meaning of photographs and sought instead the slightest visual evidence for their own narratives of events. In photographs that had used tropes of war and suffering to foreground the victimhood of the Bogsiders, they instead searched irregular patches of lights and shade on the edges and in the background in order to assemble plausible weapons in these images in Coleraine County Hall. Indeed, Widgery exploited the tension between the perceived objectivity of photographic evidence and its implicit ambiguities of meaning in order to imply the guilt of the deceased.

Figure 6 Barricade in Rossville Street, 30 January 1972 (Richard White). Image courtesy of Richard White.

The contents of the pockets of Gerald Donaghy formed a central part of debates around his death, and photographic evidence was central to this.Footnote 86 Donaghy had been with James Wray, Gerald McKinney, and William McKinney near the barricade in the Glenfada Park area when he was shot.Footnote 87 Soldier PS.34 described how he was directed to a car park on Foyle Road, where he photographed the body of a youth, a white Cortina, and four nail bombs. He watched as one nail bomb was removed from his pocket and saw the others removed from the car by the ammunition technical officer, Soldier 127.Footnote 88 This series of images was repeatedly shown to witnesses who had attended to Donaghy as he died, who in turn resisted the seemingly damning evidence of the photographs. Hugh Young had been looking for his brother, John Young, on the afternoon of the march. He came across Donaghy lying injured in William Street and dragged him by the legs into the home of Raymond Rogan, the chairman of the Abbey Park Tenants’ Association. He then searched the two top pockets of Donaghy's denim jacket looking for identification.Footnote 89 He affirmed, “If I had known he had a nail bomb I would not have dragged him across the road.”Footnote 90 However, “the pockets of Mr. Donaghy that I searched were completely empty.”Footnote 91 Similarly, Rogan, who helped carry Donaghy from his front door into his living room, and Kevin Swords, a doctor who attended to Donaghy, did not come across any nail bombs.Footnote 92 When Young and Rogan attempted to drive Donaghy to hospital they were forcibly removed from their vehicle at a military checkpoint.Footnote 93 The car was then driven by a soldier to the Regimental Aid Post of the 1st Battalion Royal Anglican Regiment, where Donaghy was examined by the medical officer (Soldier 138), who pronounced him dead but who, in the course of his examination, discovered no nail bombs.Footnote 94 This focus on what, if anything, was in Gerard Donaghy's pockets contained a deliberate effort to change the terms of the debate. Although Widgery was criticized for setting the parameters of the investigation as from “the period beginning with the moment when the march first became involved in violence and ending with the deaths of the deceased and the conclusion of the affair,” with reference to Donaghy the main focus of his investigation was whether he had nail bombs in his pockets, not whether or not he had thrown one at the soldiers or had been intending to use one when he died.Footnote 95 Indeed, the photographs served an important function in this respect, anchoring debate over Donaghy's death in the moments after he died, and adding an extra layer of authority to the soldiers' version of events.

Just as at the Battle of the Bogside eighteen months previously, photography was used as a coercive and disciplinary mechanism by security forces on the day of Bloody Sunday. But the army and the RUC were certainly not omniscient presences in the Bogside; indeed, the absence of official images of the events was notable and significant. In questioning, General Robert Ford, the commander of the army in Northern Ireland, stated, “The directive issued to both the Army and the RUC for dealing with illegal marches was that if practicable the leaders would be arrested at the time, either by the RUC under the Public Order Act or by the Military under the Special Powers Act, but that if this was not practicable they would be identified [by photograph] for possible prosecution later.”Footnote 96 However, none of these photographs were produced as evidence. The only soldier interviewed by the tribunal who had taken photographs within the Bogside on 30 January was Soldier 028, a press officer for the 22nd Light Air Defence Regiment of the Royal Artillery. He told the tribunal, “One of the shots is of the ambulance sitting outside Block 1 of the Rossville Flats after the shooting or during the lull in the shooting and some are of some soldiers. I am not a professional photographer and it is not an automatic camera.” He did not bring the photographs with him when he was called to appear at the tribunal because he did not think they were “particularly relevant.”Footnote 97 Similarly, stills from a film of the march taken from a military helicopter were blurred and unclear, and they were infrequently used to provide evidence or contextual information. This absence did not go unnoticed: in his final address, James McSparran, counsel for the next of kin of the deceased, pointed out that alongside the large numbers of press in the city, RUC personnel were also present on top of the embassy building, which had a substantial section of the immediate area under view.Footnote 98 Not only did the army's evidence run counter to the narrative constructed through images, but, McSparran also suggested, the army deliberately suppressed the photographs that prejudiced their case. He pointed out that, despite there being army photographers present in the Bogside on 30 January, no army photographs taken “from the ground during the trouble” were produced. Indeed, he posed the rhetorical question: “Is that another situation where the film just did not come out or something happened to prevent that man's photographs being made available to the tribunal?”Footnote 99

When the soldiers of the First Battalion Parachute Regiment were questioned, they had no real sense of how the photographs taken by journalists might reconcile with—or interrogate—their memories or accounts of events. Soldier V, for example, spoke with a sense of indeterminacy and confusion, and he had no understanding of what the implications of photographs he was shown were or how they might match or contradict his own memories. He first described how a hundred men were at the end of Chamberlain Street, stoning and throwing bottles at the army. However, he was then shown Derrick Tucker's photograph of the crowd running away from an approaching military vehicle, and was asked, “it is quite clear on that picture that nobody is turning in your direction to throw anything. They are running in the other way, are they not?”Footnote 100 When prompted to reconcile the photographs with his telling of events, he said that he could not.Footnote 101 McSparran told him, “you must have fired, if you are telling the tribunal the truth, when there were a substantial number of people around the forecourt of those flats. What I am suggesting to you is that that photograph proves that.” However, Soldier V resisted the reading of events presented by the photograph: he rejected McSparran's contention and he also denied being any of the soldiers in the photograph.Footnote 102

A close reading of how photographs were handled at the Bloody Sunday tribunal reveals the complex ways in which competing truth claims were navigated. On the day the tribunal opened, Lord Widgery had set out to give the proceedings the appearance of rigorous judicial impartiality. He stated, “The tribunal is not concerned with making moral judgements; its concern is to try and form an objective view of the precise events and the sequence in which they occurred, so that those who are concerned to form judgments will have a firm basis on which to reach their conclusions.”Footnote 103 Photographs were central to this process: more than five-hundred photographs were collected as official exhibits of the tribunal, and their privileged status as devices of positivism and objectivity accorded them a central status in the processes of the tribunal. However, Widgery used photographic evidence in a highly selective and subjective fashion, pushing at the boundaries of shapes, flaws of images, and ambivalences regarding timing and directions of movement within photographs to reinforce the inquiry's focus on the guilt of those who died. This dualism, whereby a rhetoric of photographic positivism was employed alongside an exploitation of the ambivalences of photography, was continued in the final report. Indeed, the report described the “large number of photographs produced by professional photographers” as “a particularly valuable feature of the evidence.”Footnote 104 Giving the investigation the appearance of a fact-finding mission backed by objective source material, images were identified by long reference numbers under headings that included “Narrative” and “Responsibility.” However, preventing the possibility of multiple interpretation, copies of the images discussed were not included.

CONCLUSION

One of the best-remembered images of the Troubles is that of the body of Jack Duddy being carried by four people, still under gunfire, as Father Daly walked in front, waving a bloodied white handkerchief. The young boy's prone body, the priest, and the seemingly unexplainable violence, reproduced and reinforced images already associated with Ireland and came to symbolize the trauma and pain of the whole Catholic community throughout the Troubles. As such, the photograph has become divorced from the moments of brutal horror as a teenager died in a car park in Derry. However, the reinsertion of this iconic image into the context of its production and dissemination is revealing of the link between the market and the state in the formation of narratives of violence in Northern Ireland. While scholars have often characterized photography as part of the disciplinary arm of the state, these examples reveal the complexity of this relationship. In both the Scarman and Widgery tribunals, the critical mass of photographs were taken by journalists, not the RUC photographers, while the uses of photography as evidence were highly contingent and problematic.Footnote 105 Indeed, the construction of state-sponsored truth was dependent on the nexus of the market in images, stereotypes of Ireland, media constructions of violence, and judicial processes.

Throughout both tribunals tropes of violence and victimhood dominated how the community in the Bogside was viewed. But these themes played out very differently at each tribunal. Photographs of the Battle of Bogside tended to be of rioters, stone-throwers, and barricades. But if the Catholic community was often represented as a “faceless” crowd, the Protestant community was simply absent. It must be noted how few photographs, whether taken by the RUC, journalists, or amateurs, feature Protestant crowds or Protestant areas—as if the violence of these Catholic crowds had no object, and as if the Protestant community barely retaliated. The exceptions to this were photographs by McMonagle and O'Boyle that turned the gaze back upon the RUC, revealing an overstretched police force and validating the deployment of the British Army. However, the photographs examined before the Widgery tribunal were very different. Following photographic conventions of war, photographs of Bloody Sunday focused on the victims; these were photographs suffused with emotion showing bloodied bodies on the concrete of Rossville Street.Footnote 106 The framing was tighter and more consistently focused on individuals than it was in the photographs submitted to Scarman. The tendency of photography to decontextualize, to isolate events from longer histories, was exploited by Widgery to focus the inquiry on the short moments of shooting and to pull the events away from longer histories of state policy in the province. But the emotive focus on victimhood by the professional photographers who overwhelmingly supported the Catholic community's interpretation of Bloody Sunday actually contributed to a process in which the focus of the tribunal turned to the actions of the dead rather than those of the army. Indeed, these photographs became part of a group of documents that enabled those who produced the final report to deal only with the circumstances around which the victims died, focusing on the question “Were the deceased carrying firearms or bombs?”Footnote 107

The perceived evidential properties of photographs were also used to provide appropriate readings of civil disorder and violence. Photographers who saw themselves and their medium as in the service of telling stories of injustice instead found that their images were read to reinforce the actions the state and security forces had already taken. At the Scarman tribunal, the ambiguities around viewpoints, distances, and directions of movement were interrogated, and the implications of these competing readings were discussed. Photographic evidence provided a route to a democratized forum where a variety of versions of the same events could be heard and given equal weighting, albeit bounded by photographers with a gaze trained consistently on the activities and spaces of the Catholic community. However, there was no direct link between the proliferation of photographic equipment and a democratization of truth. At the Widgery tribunal, the range of readings an image could provide was narrowed and so, therefore, were the range of interpretations of events curtailed. In contrast to the conduct of the Scarman tribunal, Widgery exploited culturally specific notions of photographic truth to shut down debate about what the photographs presented. However, even as he did this he exploited the malleability of light and shade in the images placed before the tribunal in order to build a case for the guilt of those who died.Footnote 108 The focus on the camera's gaze renders visible the mechanisms by which seemingly neutral or objective state processes became part of the systematic attribution of blame for violence to the Catholic community. This process is both representative and a constituent of the process whereby the history of the commencement of the Troubles was understood contemporaneously, and by scholars since, as the story of the transformation, or radicalization, of the Catholic community following seeming timeless narratives of a colonial community with an underbelly of violence ready to reemerge at any moment.