Introduction

The story is well-known and diffused to this day in many popular books, websites, and personal blogs: Pope Urban IV, having decided to establish a universal feast in honor of the Eucharistic Christ, commissioned the Dominican Thomas Aquinas, Lector of the Sacred Palace, and the Franciscan Bonaventure of Bagnoregio, Minister General, each to compose an Office and Mass for the new solemnity, reserving to his pontifical judgment the right of selecting the new liturgical texts. The two mendicants, bound by filial piety, obliged the pontiff's wish. On the day appointed for examination—with Thomas presenting first—the now-beloved hymns in praise of the Blessed Sacrament were heard for the first time by Urban, the curial cardinals, and the Seraphic Doctor, all of whom were visibly moved by the stunning poetic achievement placed before them. Bonaventure, compelled by humility, silently tore the manuscript still hidden beneath his habit. Upon finishing his exposition, Thomas yielded the floor to Bonaventure; Bonaventure, in turn, ceded the contest to Thomas. The chief of the Friars Minor fell at the pope's feet and, revealing the shredded papers, confessed the secret deed carried out while the Angelic Doctor held the attention of all:

Holy Father, while listening to Brother Thomas, I felt as if I heard the Holy Ghost speak, for only He could inspire such sublime thoughts; I am sure that those words came from the Most High, revealed by a special grace to my Brother Thomas. Dare I confess this, O Holy Father? I would have considered it sacrilege if I were to have allowed my poor work to stand beside such marvelous beauty (Avrei creduto di commettere un sacrilegio se avessi lasciato esistere la mia debole opera vicino a quelle meravigliose bellezze). See, Holy Father, what remains of my work.Footnote 2

Unfortunately, this lovely account—which reads more like a medieval exemplum than an historical chronicle—is probably legendary. We cannot, however, dismiss it as easily as did one recent liturgical commentator, who suggested the story's impossibility since, at the time of Corpus Christi's composition, Bonaventure would have been in Paris while Thomas resided in Orvieto near the Roman Curia.Footnote 3 Sed contra: Bonaventure was in fact in Italy for most of 1264, even writing his Eucharistic sermon De corpore Christi Footnote 4 in Italy during the spring of that year—the very period in which Thomas would have been working on the Mass and Office.Footnote 5 Bonaventure is furthermore known to be at Orvieto by 31 AugustFootnote 6—less than three weeks after Urban IV promulgated the new feast from that same city through the bull Transiturus.Footnote 7 In sum, the possibility of direct contact between the two mendicants in the presence of the curia in the spring and summer of 1264 cannot be rejected as out of hand, and indeed it seems more probable, as Minister General of an Order under the protection of the Apostolic See, that Bonaventure had ample reason to visit Orvieto often during his travels through Italy in that year. Disproving the legend thus requires historical evidence beyond the presumption of a static Parisian residency on Bonaventure's part. To that end, Francesco Petrangeli Papini's small article ‘San Tommaso, San Bonaventura, e l'Ufficio del SS. Sacramento’Footnote 8 is of invaluable assistance.

Although Papini focuses on the emergence of artworks depicting or referencing the presumed contest (or, in some cases, the collaboration) between Aquinas and Bonaventure on the Corpus Christi liturgy, his rather simple yet lucid historical presentation points to the improbability of the legendary accounts which link both Doctors to the composition of the Mass and Office. Papini notes that many important works connecting both Thomas and Bonaventure with Urban IV and the Feast, specifically in those places associated with the three figures (especially Lyon, Orvieto, and Bagnoregio), date only from the seventeenth century onward. Meanwhile, in Orvieto itself—and as emphasized by Papini himself in a more expansive monographFootnote 9—the earliest depictions of the Feast of Corpus Christi, as well as the earliest historical narratives of the Feast's origins, show Urban IV and Thomas only; presentations of Bonaventure are conspicuously absent in paintings in the Cathedral of Orvieto (executed between 1338 and 1357) and in two early chronicles, Sacra rappresentazione and Historia Bolsenese (1325-1330 and 1323–1344, respectively).Footnote 10 That the city of Orvieto, jealously proud of its historical connection to the solemnity since its inception, should adorn its first depictions of the Feast with images of Urban and Thomas—without Bonaventure—strongly indicates the later origin of the ‘contest’ story.

Without presenting a clear smoking gun, however, Papini lends further credible weight to the lateness of stories linking Bonaventure to Corpus Christi by producing two extracts from the canonization process of Bonaventure, which concluded only in 1482. These records antedate the artworks depicting both Thomas and Bonaventure but postdate the aforementioned Orvieto paintings. In one deposition from 1480, a lawyer named Antonio Pisi

testified that he was once present in Paris during a sermon on Saint Thomas Aquinas given by some public preacher, and he heard that while Saint Thomas was in his study, dictating the Office of Corpus Christi, the lord Bonaventure arrived with other scholars to pose some questions to Saint Thomas. And ascending alone to the door of the study, [Bonaventure] saw the aforementioned Saint Thomas writing, and the Holy Ghost in the form of a dove holding a scroll in its mouth, as if suggesting to Saint Thomas what to write. And turning to the others, Bonaventure said, ‘Let us depart from here, for where the Holy Ghost labors, there do we work in vain’, revealing to his companions what he saw. And holding in his hands a certain folio on which [Bonaventure] had written some of the aforementioned things, he tore it in the presence of his companions (tenens in manibus certam papirum in qua scripserat aliquid de materia predicta incontinenti presentibus sociis illam fregit), saying that what he had written should never be seen, for the Holy Ghost had placed its hands on the dictation of Saint Thomas.Footnote 11

While this version varies from the ‘contest’ narrative reported by Theuli, it contains the motif of Bonaventure destroying his works, commonly represented in the later seventeenth century artworks mentioned by Papini. A reference to a more collaborative account is given by a Dominican friar in the same canonization proceedings.

William Turini, doctor of sacred theology, of the Order of Friars Preachers in the convent of Lyon… attested that… when he was in Paris, he heard it commonly said that the aforementioned lord Bonaventure was a contemporary of Saint Thomas Aquinas; and when the pope charged the same Saint Thomas to write the Office of Corpus Christi as well as answers to certain questions on the Body of Christ, the lord Bonaventure was asked by not a few great doctors of Paris to do the same, that is, to compose an office of Corpus Christi and answers to the same questions (idem facere scilicet officium de corpore christi et conclusionem earundem questionum facere); which [Bonaventure] did and communicated these things to Saint Thomas afterward.Footnote 12

This might be the earliest known written source for a collaboration between the Saints, which is depicted or referenced in several later artistic pieces, such as a 1622 cover image for an edition of Bonaventure's Opera Omnia,Footnote 13 and in a notable seventeenth century oil painting of Thomas and Bonaventure before the Sacrament, found in the old Franciscan convent of Spirito Santo in Ferrara.Footnote 14 In any case Turini's testimony still postdates the works in Orvieto Cathedral which seem to definitively exclude Bonaventure from the Corpus Christi origin story. In light of both these citations from the Bonaventurean processus, both of which involve persons hearing these stories said in the open, perhaps the passing suggestion offered at the beginning of this paper—that the stories involving both friars in the redaction of the Corpus Christi liturgy might be medieval exempla used for popular preaching—could have some truth behind it.

Since Papini, to my knowledge no other early texts attesting to Bonaventure's participation in the composition of Corpus Christi—whether as Thomas's competitor or collaborator—have been found. Meanwhile, the twentieth century labors of many prominent Thomistic scholars, especially Jean-Pierre Torrell and Pierre-Marie Gy, have affirmed the sole authorship of Thomas.Footnote 15 We need not wonder, therefore, whether Bonaventure even had an opportunity to plead ‘no contest’ in favor of the Thomistic Mass and Office, since the story, too late in provenance, is not referenced in the earlier accounts. However, perhaps we can imagine what such a contest would have really been like: not a sweet, simple, and easily resolved confrontation like those found in so many exempla, but one which takes into consideration the real differences between the philosophical, theological, and poetic approaches of the two Doctors. In doing so, we might better intuit whether—had a contentio carminum truly taken place—one friar might have really conceded victory to the other.

This paper proposes a small contribution to comparative studies on Aquinas and Bonaventure through an examination of their poetics, with a view to suggesting a possible ‘victor’ of a hypothetical challenge. While the literature investigating their respective philosophical and theological doctrines has expanded greatly over the last century, the literature on their poetics pales in comparison. And while important work on the Corpus Christi liturgy has been produced by Thomistic scholars in recent decades,Footnote 16 this increased interest in Aquinas's poetry has not been matched by a corresponding scholarly curiosity about the Seraphic Doctor's poetry; in fact, Bonaventure's poetic output remains largely obscured by his better-known academic and mystical treatises. One of the secondary aims of this paper, therefore, is to (re-)introduce Bonaventure the Poet to a larger audience, that this neglected area of Bonaventurean studies might be considered by scholars in light of his wider opera.

Following this historical introduction, the essay will proceed in three main sections followed by a synthetic conclusion. First, I will consider Bonaventure's hymns from his Officium de Passione Domini, now generally counted among his authentic works.Footnote 17 This text, on account of its liturgical nature (unlike Bonaventure's devotional poetry like the one in the programmatic prologue of Lignum Vitae Footnote 18 or the longer poem Laudismus de Sancta Cruce Footnote 19) will allow for a closer comparison with Aquinas's hymns for the Office of Corpus Christi, which will be examined in the third section. The second section, linking the two, will consider a direct contrast between Aquinas and Bonaventure on their mode of composing the final doxological verses of their respective hymns. This work will accordingly involve close textual criticism of the poems, with special attention to the compositional technique of each Doctor and their respective uses of prosodic devices such as rhyme, meter, assonance, and the like. For the sake of space, only excerpts of the poems can be considered here, but the selected extracts will be sufficient to sketch the distinctive nature of each author's poetic works. After this summary examination of both poet-theologians, I will conclude by suggesting an answer to the question: had there been a poetic contest between the two, who might have won?

Bonaventure: Officium de Passione Domini

The Officium de Passione, found in Volume 8 of the Quaracchi edition of Bonaventure's Opera Omnia, includes antiphons, readings, and orations for the various hours, in addition to hymns for each hour. Thus, as compared to the Office of Corpus Christi (which only features hymns for Matins, Lauds, and Vespers), Bonaventure's poetic production is significantly longer than that of Thomas. King Louis IX of France personally requested Bonaventure to compose this Office of the Lord's Passion, a task which the Seraphic Doctor completed in March 1263.Footnote 20 It is thus separated only by about a year from the composition of Thomas's Office, and this near-contemporaneity further disposes both Offices to a direct comparative analysis.

This Office proceeds on the basis of eight-syllable lines grouped into stanzas of four lines. For Matins and the minor hours, the rhyme scheme moves in couplets (AABB, etc.), while for Lauds and Vespers, a more complex scheme involving rhymes alternating by line (ABAB, etc.) with the addition of internal rhymes in the first and third lines of each stanza. Lauds and Vespers also feature a device common in high medieval Latin hymns: the final line of each stanza is a taken from the incipit of an older Latin hymn.Footnote 21

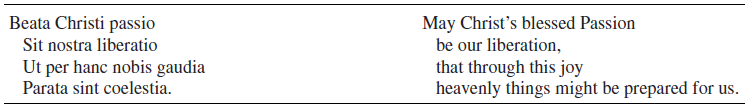

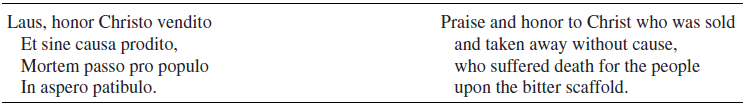

We begin with a verse from None whose simplicity shines through the use of rhyme and meter.

Here we find the straightforward, hortatory tone which often marks Bonaventure's poetry. This particular stanza is notable for its succinct completeness, expressing in versified form the features of petitionary prayer, such as the use of the subjunctive to indicate a desired future result. The use of iambic dimeter is stable, producing a memorable and pleasantly rhythmic flow (although ‘Ut hanc per nobis gaudia’ would sound smoother). However, this metrical regularity is not consistently present across the Office. At Vespers, we find the following.

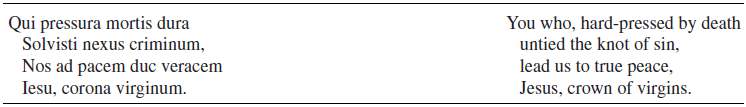

Beginning with an accented syllable, the first line accordingly ends with an unaccented syllable; however, this produces an awkward rhythmic transition to the second line, which itself begins with an unaccented syllable, in turn creating a kind of interruption in its enuncuation. Meanwhile, because Bonaventure holds himself to citing the titles of older hymns in the final lines of each stanza (choosing ‘Iesu, corona virginum’ in this instance), its particular deployment here seems rather out of place, since the line's original liturgical context (Vespers for the Common of Virgins, that is, a liturgy with a more festal character), has little direct connection with the themes of suffering of death. Later in the same vespertine hymn, the stanza cited below also breaks the iambic dimeter by presenting two unaccented syllables between the first and second lines; this then leads to the second line ending without accent. In turn this moves more comfortably into the accented ‘Fac’ of the third line, which however leads to a repetition of the same double unaccented transtition between lines three and four.

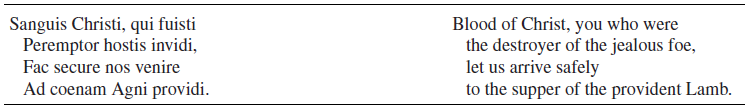

As noted before, Bonaventure in this poem strictly follows a quatrain format marked by eight-syllable lines with a complex rhyme scheme; however, his inconsistent attention to (or disregard for) metrical feet produce unpredictable rhythmic disturbances in the poem's enunciation. It is possible, however, to suggest a charitable interpretation of these metrical irregularities by reading these sudden shifts in tempo as mirroring the chaotic, stuttering, and tedious procession to Calvary undertaken by Christ; nevertheless, definitively proving this authorial intent is simply impossible. Bonaventure here in any case demonstrates the grave risk undertaken by poets who from the outset insist on rigid adherence to a specific prosodic format (i.e., rhymed quatrains of eight-syllable lines), for when the author arrives at a compositional difficulty and simply cannot find the mot juste, a break from the format becomes all the more evident, appearing less as a deliberate choice for the sake of a certain rhetorical-poetic effect, and more as a poetic failure. We glimpse this same sense of failure when, in the third line, an internal rhyme to parallel the first line's Christi-fuisti is conspicuously absent.

Moving to Lauds, we find the following verse:

Without repeating the same issues regarding meter and feet, the lexical selection shown above leaves much to be desired. The formulation ‘Poena fortis tuae mortis’ resounds awkwardly, for ‘fortis’—a generally positive adjective in Latin—is used here to modify ‘poena’. Constrained to find a rhyme for ‘mortis’, the author clumsily settles for an unfitting modifier, and the poetic expression suffers for the sake of extrinsic structure. At Terce, the issue of strange yet unimaginative diction also arises:

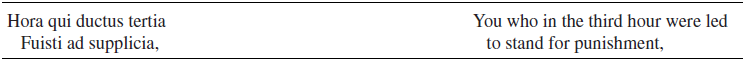

where use of ‘fuisti’ once again appears as an ungrammatical poetic choice bound strictly to the predetermined syllabic scheme. The correct Latin usage of the present or imperfect forms of the verb sum-esse (‘es’ or ‘eras’, respectively) as auxilliary to the participle ‘ductus’ would clearly not suffice for Bonaventure's format. To resolve this challenge, here he utilizes what is obviously a retrojection of a Romance construction (i.e., the perfect of ‘to be’ as auxiliary to the fourth principal part) into Latin, with less than satisfactory results.

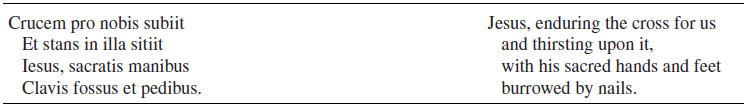

By now, the metrical weaknesses of Bonaventure's Office are apparent, as seen again in this verse from Sext. At the words ‘Crucem pro’, the doubled unaccented syllables generate the same rhythmic problems as before, but which could have been easily avoided by rewording the line as ‘Pro nobis crucem subiit’. The next phrase, ‘Et stans in illa sitiit’, is marked by a particular verbosity, almost devoid of poetic force, whose main purpose is simply to fill the requisite syllables. The thirst of Christ and anguish linked to it could have been illustrated with a host of other adjectives or adverbs; meanwhile, the choice of ‘stans’ to describe Christ's position on the cross feels far too weak, wholly inadequate to the monstrous terror of Calvary.

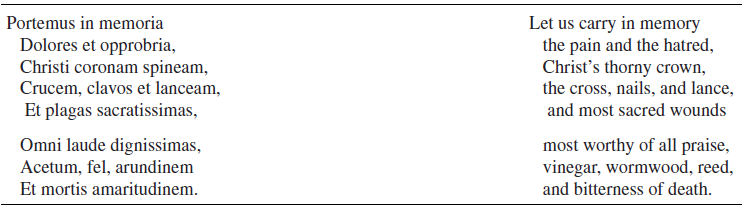

At Matins, the Office exhorts its participants to remember the details of the Passion:

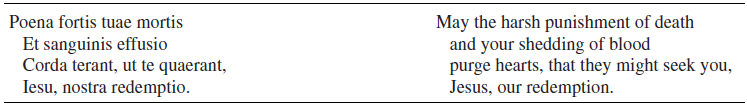

Likewise at Lauds, the individual sufferings endured by Christ are recalled:

This manner of listing a set of objects in close succession without recourse to several modifiers brings to mind Catherine Pickstock's critique of modern language and syntax given in After Writing. The list, which she associates with an imperious Cartesian gaze upon a mass of res extensae immediately ‘available’ to the sovereign thinking subject,Footnote 22 is also linked to the near-exclusive use of asyndeton (the absence of coordinating conjunctions)Footnote 23 at the expense of more complex syntactical forms such as parataxis (the use of coordinating conjunctions to link clauses) and hypotaxis (employment of subordinate clauses).Footnote 24 Note the lists of objects to be memorialized without a coordinating ‘et’: ‘thorny crown, | cross, nails, lance’; ‘vinegar, wormwood, reed’; ‘bruises, | spittle, whips, scourges’. All these things are simply compiled together, without further explanation, in a facile asyntactic mode of composition. Even when the conjunction is present (‘Crucem, clavos, et lanceam’), its usage remains bound to the completion of the syllabic line, while in the following stanza, the line ‘Et mortis amaritudinem’ provides an extra syllable, breaking Bonaventure's chosen format more egregiously. I need not launch the full weight of Pickstock's position upon the Seraphic Doctor's hymnody, but we might at least consider how the lack of hypotaxis and parataxis shown here, taken with the asyndetic and list-like presentation of objects, might suggest a rather superficial and immanent use of language which tends toward the purely indicative and fragmented vision more characteristic of secular modernity than the integrated doxological ethos represented by the language of the Roman Rite and (as we hope to show later) the poetics of Thomas Aquinas.

Transition: The Doxological Verses of Bonaventure and Aquinas

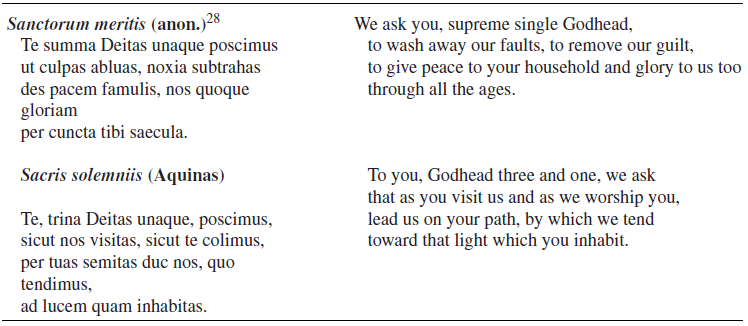

As a specific point of comparison with Aquinas's Office worth anticipating here, whereas the Angelic Doctor's hymns each end with a unique Trinitarian doxology, the hymns for each hour in Bonaventure's Officium conclude with the same doxological quatrain focused on Christ alone.

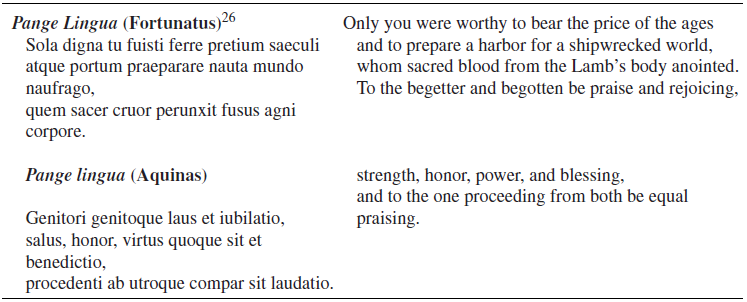

We can set aside the accentual inconsistency once again evident in the transition from the second to third line, concerning ourselves instead with the recurrence of this verse through the Office. The notion of identically repeating the same ending at each hour—despite the fact that, at Lauds and Vespers, this requires breaking the rhyme scheme—perhaps points to a degraded sense of creativity in Bonaventure's poetics, a judgment made clearer in light of the closing doxological stanzas composed by Thomas. Before proceeding, it is helpful to recall that Aquinas's hymns for Corpus Christi are contrafactions of older hymns, which is to say, he takes the structure and melody of hymns from the venerable repertoire of the Roman Rite and models his own Eucharistic hymns upon them. Pange lingua gloriosi corporis mysterium for Vespers is a contrafaction of Venantius Fortunatus's Pange lingua gloriosi proelium certaminis for the Feast of the Holy Cross; Sacris solemniis for Matins is a contrafaction of Sanctorum meritis for the Feast of the Ascension; and Verbum supernum prodiens for Lauds is a contrafaction of Aeterne rex altissime.Footnote 25 Examining the Thomistic doxologies in light of their more ancient precedents will further place into relief the relative quality of Bonaventure's poetry as expressed in his use of a repeated closing stanza.

Fortunatus's hymn is notable in that it originally has no concluding doxology, so the final verse is reproduced above simply to give the reader a sense of its style. Thomas, resolving to end all his hymns with an explicit cry to the Triune God, must therefore compose a doxology which holds to Fortunatus's format and to the general characteristics of Trinitarian praise while employing his own lexical ingenuity. It seems that he indeed found success in that enterprise. ‘Genitori genitoque’ rings as a clever alliterative phrase expressing both the close similarity and distinct difference between Father and Son, while nomination of the Spirit as procedens hearkens back to the language of the Creed.Footnote 27

Aquinas's Trinitarian shift is obvious as he changes ‘summa’ to ‘trina’. The parallelism in Sanctorum meritis at ‘culpas abluas, noxia subtrahas’ is matched by Aquinas's ‘sicut nos visitas, sicut te colimus’. However, the relatively vague reference to a desire for peace and glory in the older hymn finds a clearer sacramental and soteriological counterpart in Sacris solemniis, where the ‘path’ leading to the eschatological light where God dwells references the Eucharist.

While the formula ‘cum Patre et Sancto Spiritu | in sempiterna saecula’ is a stock phrase concluding many Latin Christian hymns,Footnote 30 Aquinas takes a different approach by invoking the Trinity first, and concluding once more with a specific reference to the eschatological terminus of participation in Christ's Body and Blood, which is everlasting life in heaven.

In these three hymnic conclusions from Thomas, and in light of the previous reflections on Bonaventure's Office, we can already sense the rather wide difference between the respective poetic capabilities of the Angelic and Seraphic Doctors. Aquinas, by binding himself to older hymns as his structural models, paradoxically appears to be at greater liberty in his compositional enterprise; even when he closely follows the lexical patterns of his precedents, such as in the conclusion to Sacris solemniis, he nevertheless places his own characteristic stamp on the contrafaction. ‘Sicut nos visitas, sicut te colimus’, for example, is not only a parallelism which structurally mirrors the corresponding line in Sanctorum meritis, as noted before; here, Aquinas deftly describes the upward motion of doxology and the downward motion of divine emanation in a single breath. The Neoplatonic notion of exitus-reditus—itself a sign of the high medieval Dionysian reception which Thomas helped to advanceFootnote 31—is brought to bear succinctly and elegantly in this Trinitarian doxology. Non-identically repeating himself, Thomas carries the trace of the older hymns while supplementing them with his own doctrinal-poetic insights, thereby producing true cantica nova which nevertheless resound with the timeless echo of their Christ-rooted origin. The use of rhyme in Aquinas, moreover, does not seem to burden the poetry, and avoids the tedium or strain evident in Bonaventure.

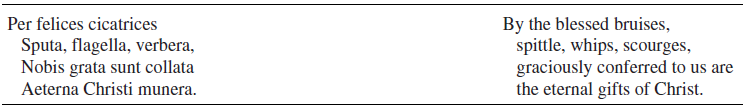

The Seraphicus, on the other hand, opts for an identical repetition of his doxological verse. This is a curious choice, since the very structure of the Hours, each one associated with a specific stage of the Passion (i.e., Christ prayed in Gethsemane at Compline, was condemned at Prime, scourged at Terce, crucified at Sext, died at None, and was taken down at Vespers),Footnote 32 would allow him to extend the unique focus of that hour into the doxology. In the main stanzas of the hymns, he already clearly references this traditional mode of dividing the events of the Passion across the Hours, for example, in the already cited lines of Terce (‘Hora qui ductus tertia | fuisti ad supplicia’) and None (‘Clamans emisit spiritum’). The selection of readings for each hour also would have also provided ample thematic and lexical content for Bonaventure to integrate into unique versified conclusions, but he seems not to have relished that particular challenge.

Thomas Aquinas: Officium Corporis Christi

Aquinas's creativity, by contrast, lies not in a simple ability to refashion venerable hymns in the manner of superficial parody; rather he adapts the received forms for the specifically new purpose of deepening his praise for Christ's Eucharistic presence. Since these hymns are far better known and have been the subject of much scholarly attention over the past several decades, I will only examine a narrower set of excerpts which nevertheless highlight Aquinas's poetic technique.

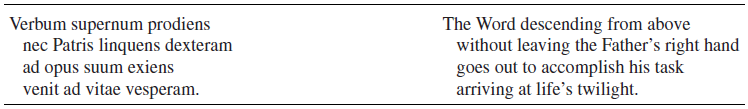

Because Aquinas is held to a narrower focus in his Office (i.e., the Last Supper and the Eucharist), as opposed to Bonaventure's wider concern for the whole Passion story, he need not draw the same kind of narrative progression traced by the Officium de Passione. Nevertheless, because the Feast thematically refers to both Maundy Thursday and the Church's continued celebration of the Eucharist, Aquinas can still recall the notion of the Last Supper as a sacrificium vespertinum as seen in the fourth line above, while also metaphorically linking the evening of Maundy Thursday to the twilight of Christ's earthly sojurn.

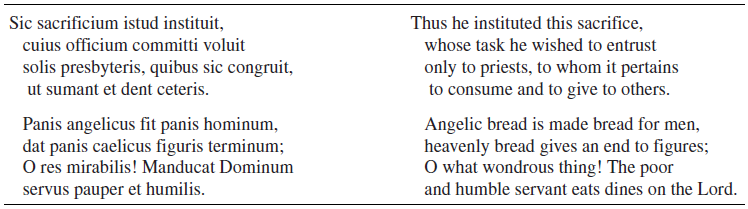

On the level of prosody alone, we find an impressive structure. These two verses of Sacris solemniis manifest the zagialesca format which became widely diffused in high medieval Latin poetry through the opera of Adam of Saint-Victor (and which also structures the sequence Lauda Sion).Footnote 33 Each verse in a pair is comprised of a series of consecutive rhyming lines (‘instituit’, ‘voluit’, ‘congruit’; ‘hominum’, ‘terminum’, ‘Dominum’) which is broken by a final line; however, the respective final lines in each pair rhyme with each other (‘ceteris’ and ‘humilis’), such that the pair as a whole is encompassed by this sense of sonic completion. What is unique in Aquinas's execution here, however, is the complex interplay of internal rhymes. In the first two lines of each verse, ‘sacrificium’ and ‘officium’ rhyme, as do ‘angelicus’ and ‘caelicus’. One might expect that third line of each verse would display a corresponding internal rhyme, but the pattern is seemingly broken. This rupture is only apparent, however, since ‘presbyteris’ in reality anticipates ‘ceteris’ in the fourth line, which thereby also matches with the corresponding ‘mirabilis’ and ‘humilis’ in the following stanza.

Despite adhering to this format, Thomas does not appear impeded in his expression, perhaps because of the dense theological and philosophical valence of his subject matter. Consider, for example, that the verse beginning ‘Sic sacrificium’ references what today forms part of standard Catholic doctrine on Holy Orders; that the priesthood of the New Covenant was established at the Last Supper is proposed in verse here by Thomas, a position which placed him at odds with some of his contemporaries, including Bonaventure.Footnote 34 In fact, the exact moment of the priesthood's institution remained an open question until the sixteenth century, when the Tridentine Fathers confirmed Thomas's position.Footnote 35 Following the theme of the transition from Old Israel to the Church marked by Christ, the verse ‘Panis angelicus’, known for its many famous musical settings by later composers, is also noteworthy on account of a brilliant double entendre. At first glance, ‘figuris terminum’ might appear to be a statement which, like the line ‘et antiquum documentum novo cedat ritui’ in Pange linga, simply references the New Covenant's inauguration as such, and while this meaning is certainly true, there also lies an underappreciated philosophical and sacramental angle. In Thomas's metaphysical account of transubstantiation, the Body and Blood of Christ are said to be the terminus of the conversion, while the figurae of bread and wine remain.Footnote 36 The dual meaning of terminus (as both historical end of the Old Law and as metaphysical final cause) is thereby paralleled by the dual meaning of figura (as the signs of the Old Law and as the species of bread and wine), and their joint usage in this verse is but another testament to the synthetic metaphysical-theological-poetic insight of the Angelic Doctor, which is perhaps most brilliantly expressed in the following verse from Pange lingua.

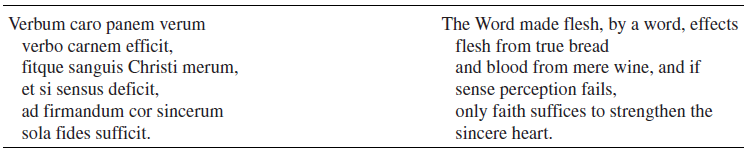

Faced with the unfathomable triplex mystery of Creation-Incarnation-Transubstantiation wrought by the Eternal Word, Thomas, adhering to Fortunatus's trochaic septenarius, boldly sings the limits of Aristotle's recourse to the certainty of sense knowledge. Other authors, in words more apt than our own, have already singled out for special praise the witty combination of assonance, alliteration, pun, and paradox which animates this famous stanza,Footnote 37 but perhaps few so have so accurately placed their finger on Thomas's pulse as the Jesuit philosopher Walter Ong.

Thomas is here concerned with the fact that it was not God the Father nor God the Holy Spirit, but the Second Person, God the Word, Who became flesh, and that this same Word, when He wishes to convert bread into His flesh uses words as the instruments for His action. This is a coincidence startling enough and too good to be missed, the more so because the use of words in connection with its sacramental ritual was plainly distinctive of the New Law inaugurated after the Word had entered the material world as man: the Paschal Lamb which in the Old Law prefigured the Eucharistic sacrifice, had, like most other ‘sacraments’ of the Old Law, no special verbal formula connected with it. It is difficult to regard all this as mere coincidence.Footnote 38

Conclusion

In the preceding pages I have traced the salient features of Bonaventure's Officium de Passione Domini and Thomas's Officium Corporis Christi; now I arrive at a general judgment of the two poetic opera. For all the heartfelt devotion and unquestionably Franciscan character of the Bonaventurean Office, nevertheless, the frequent breaks from stable meter, moments of strange diction, and repetitive doxological endings show a relative superficiality as compared to the wit and wordplay of Thomas. As Ong fittingly comments, ‘anguish and plangency, dealing as they do in elemental and, so long as they last, quite enthralling emotions, are always popular enough responses’.Footnote 39 Unfortunately, the popular, pious, and even compelling nature of such thematic elements are not enough to mask the poetic lacunae of the Seraphic Doctor. In this early Franciscan poetic tradition there seems to be no need ‘for striking juxtapositions, for the stimulus of insights freshly arrived at, estabishing intricate connections between realities apprehended in all sorts of ways and at all sorts of levels simultaneously—no need for wit in any form’.Footnote 40

Ong's judgment against the poets of the so-called ‘Franciscan school’ may sound harsh, but perhaps linking the poetics of the two Doctors to their respective approaches to philosophy and theology might vindicate his verdict from another perspective. Bonaventure, for example, displays an almost obsessive concern for extrinsic structure in his later works. From 1257 onward (that is, from his election as Minister General to his death), Bonaventure writes no more treatises in the form of scholastic quaestiones, instead using other devices to arrange his doctrinal expositions. Whether the six-winged seraphim as a programmatic model for mystical ascent (Itinerarium mentis in Deum), the six days of creation as the basis of a theology of history (Collationes in Hexaemeron), the ninefold angelic hierarchy as a model for the human soul (Breviloquium; Itinerarium), or the application of triplex sub-patterns throughout his corpus, the Seraphic Doctor often attempts to organize his doctrine according to such numerical schemata. This does not always lead to the delineation of clearly distinct or helpful classifications, but because Bonaventure has committed himself to the predetermined pattern, he is thereby compelled at times to introduce more tedious schematic divisions in order to complete his selected numerical plan.Footnote 41 Threefold, sixfold, sevenfold, and ninefold patterns are not arrived at, but presumed and imposed, while the data of observation are forced to fit the system.

Thomas's approach, meanwhile, allows the mysteries of sacred doctrine to unfold organically in his theological work. Certainly, there exists a structural element in the Thomistic method, in that the ascent from sense knowledge of particulars to immaterial knowledge of universals presumes the hylomorphic composition of all reality, while cognition of the mysteries of faith still requires conversion to phantasms and a hylomorphic descent from formality to materiality. Nevertheless, this underlying structure—a true metaphysical structure—need not involve the meticulous and tiresome formal imposition of threes, sixes, sevens, or nines onto the objects of investigation; rather, Thomas examines these realities in themselves, allowing his explanations to proceed not by overdetermined extrinsic schemata but through fundamental metaphysical principles, whether according to the order of reality (e.g., the Summa Theologiae) or the order of discovery (e.g., the Aristotelian commentaries). Extrinsic structure, for Aquinas, should never impede but foster contemplative penetration into the mysteries.

Does not Bonaventure's predetermined insistence on apparently clean formulaic structures in his theological reflections mirror his attempted rigid adherence to prosodic forms in his hymns, and do not his obvious failures to observe his chosen rhyme and meter parallel his somewhat strange or tedious divisional classifications in his later treatises? By contrast, does not Thomas's employment of wit and wordplay, in conjuction with the use of contrafaction as a nod to tradition, suggest a more profound engagement with dogmatic mysteries and their broader implications? As Ong observes, for a true poet-theologian,

word-play and witty conceit go hand-in-hand with preoccupation with genuinely distinctive ‘mysteries’ of Christianity. Moreover, the juncture is not accidental: here conceits are simply a normal means of dealing with the mysteries of Christianity, the distinctively Christian teachings, as well as a means of achieving a successful poetic texture.Footnote 42

The technical mastery required for a successfully ‘witty’ composition, more consistently displayed in Thomas's hymns than in Bonaventure's, appear more impressive in the Angelic Doctor's work because their almost seamless integration with fixed rhyme and meter, combined with depth of theological reflection, have the effect of supporting rather than hindering the power of the message. The integration of all these prosodic devices in the Thomistic Office produces a remarkably memorable poetic density wherein the mysteries communicated are really apprehended as true on account of, not in spite of, the resonant sonic harmonies expressed in Eucharistic hymns.

A final observation: in ancient Rome, an intensive, almost overbearing recourse to rhyme and other prosodic devices was often considered to be bad poetry simpliciter and brutally condemned by more refined critics.Footnote 43 By the Middle Ages, when the old interplay of long and short syllables had transformed into syllabic accents, the emergence of rhyme might have been welcomed as a new remedy (however inadequate) for the loss of the ancient meters in the evolution of prosody. Today we can sympathize with the classical sensibility; how often are cheap rhymes employed in contemporary verse and popular music simply to bestow the barest veneer of poetic character upon an otherwise insufferably unremarkable work! But one need not look only to our time; Bonaventurean verse, if taken as archetypical medieval poetry, would prove the classical position on the whole a correct one! On the other hand, mere recourse to dactylic hexameter or trochaic septenarius would ignore the development of a distinctly Latin liturgical language—an idiom with its own towering monuments and heroic figures—for the sake of purely pagan conventions. Perhaps between these two poles—between the mere exorcism of rhyme, on one hand, and the exclusive use of classical meter on the other—a uniquely Christian balance might be struck.

Indeed, it is Angelic Doctor who synthetically resolves the polarity not by appealing to the spirit of aut…aut but by invoking the Catholic et…et. In Thomas, the last wisps of classical air breathed by Fortunatus and the sonorous high medieval rhymes of Adam of Saint-Victor meet not as ‘a clashing gong or clanging cymbal’Footnote 44 but ring harmoniously, ‘tin tin sonando con sì dolce nota’Footnote 45 in praise of the true ‘gloriosa rota’Footnote 46—the Eucharistic host—by which the love of God enters most intimately into human hearts.

Ergo quaeritur: If a contest of verses between Thomas and Bonaventure had really taken place, who might have won the poet's laurel crown? In light of the foregoing, I propose a metrical answer from a Vespertine antiphon written after the deaths of the two friars:

Felix Thomas, Doctor Ecclesiae,

lumen mundi, splendor Italiae,

candens virgo flore munditiae,

bina gaudet corona gloriae.

Or, we could simply and prosaically affirm that there is absolutely ‘no contest’.