Introduction

Involuntary re-experiencing is a hallmark symptom of posttraumatic stress disorder (e.g. Horowitz, Reference Horowitz1976). Involuntary trauma memories are easily triggered by a wide range of stimuli (e.g. Ehlers, Hackmann and Michael, Reference Ehlers, Hackmann and Michael2004; Foa and Rothbaum, Reference Foa and Rothbaum1998) and usually take the form of relatively brief sensory impressions such as images, sounds, tastes or smells (e.g. Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Hackmann, Steil, Clohessy, Wenninger and Winter2002), which are accompanied by the original emotions that the individual experienced at the time of the event (Foa and Rothbaum, Reference Foa and Rothbaum1998; Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). Patients with PTSD usually have a small number of intrusive memories that can keep re-occurring in the same form for years (Hackmann, Ehlers, Speckens and Clark, Reference Hackmann, Ehlers, Speckens and Clark2004). These correspond closely to the most distressing moments of the trauma (Holmes, Grey and Young, Reference Holmes, Grey and Young2005). There is a debate in the literature about whether and in what way intrusive memories in PTSD are different from other involuntary memories in everyday life. Some studies emphasize similarities (e.g. Kvavilashvili and Mandler, Reference Kvavilashvili and Mandler2004; Ball and Little, Reference Ball and Little2006), while others emphasize differences (e.g. Peace and Porter, Reference Peace and Porter2004; Berntsen, Willert and Rubin, Reference Berntsen, Willert and Rubin2003; Megias, Ryan, Vaquero and Frese, Reference Megias, Ryan, Vaquero and Frese2007). Nevertheless, the persistence and frequency of intrusive memories in PTSD needs explanation.

Theories of unwanted trauma memories

Why do people with PTSD keep experiencing unwanted distressing memories of the trauma? Theories of PTSD concur that such intrusive memories are due to the way trauma memories are encoded, organized in memory, and retrieved. Several theorists suggest that compromised cognitive processing during the trauma leads to certain deficits in the autobiographical memory for the event that facilitate retrieval of trauma memories to a wide range of stimuli. Several different hypotheses about the nature of this deficit have been suggested in the literature. Early theories highlighted a deficit in memory representations that facilitate intentional recall (Brewin, Dalgleish and Joseph, Reference Brewin, Dalgleish and Joseph1996) or highly fragmented memories (Foa and Rothbaum, Reference Foa and Rothbaum1998; Herman, Reference Herman1992; van der Kolk and Fisler, Reference Van Der Kolk and Fisler1995).

Empirical tests of these hypotheses in clinical populations are sparse. The fragmentation hypothesis has received some, albeit not always consistent, support (for reviews see McNally, Reference McNally2003; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Hackmann and Michael2004). There is evidence that trauma survivors with PTSD give more disorganized narratives of traumatic events than those without PTSD (e.g. Jones, Harvey and Brewin, Reference Jones, Harvey and Brewin2007; Harvey and Bryant, Reference Harvey and Bryant1999; Halligan et al., Reference Halligan, Michael, Clark and Ehlers2003). Ehlers et al. (Reference Ehlers, Hackmann and Michael2004) further suggested that the proposed deficits may not apply equally to the whole traumatic event (see also Hellawell and Brewin, Reference Hellawell and Brewin2002). As only some moments of the traumatic event are later re-experienced, the proposed deficits may mainly apply to the memory of these moments. Evans, Ehlers, Mezey and Clark (Reference Evans, Ehlers, Mezey and Clark2007) indeed found that trauma narratives around the time of the intrusive memories were more disorganized than other segments of the trauma narrative.

“Nowness” and lack of context as important features of intrusive trauma memories

Recent cognitive theories of PTSD build on clinical observations and empirical data showing that survivors with and without PTSD do not only differ in the frequency of unwanted trauma memories, but also in their characteristics. Two aspects of intrusive memories in PTSD are particularly interesting from a theoretical point of view. First, trauma survivors with PTSD describe to a greater extent that intrusive memories appear to happen in the “here and now” than those without PTSD (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). This sense of “nowness” is more predictive of subsequent PTSD than the frequency of intrusive memories (Michael, Ehlers, Halligan and Clark, Reference Michael, Ehlers, Halligan and Clark2004). Second, Ehlers and Clark (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) and Ehlers et al. (Reference Ehlers, Hackmann and Michael2004) observed that intrusive memories appear disjointed from other relevant autobiographical information. They describe cases of patients with PTSD who (1) kept re-experiencing an intrusive memory of an earlier part of the trauma as well as another intrusive memory from another part of the trauma that contradicted the individual's impressions during the first memory; and (2) kept re-experiencing moments of the trauma and the corresponding emotions although they knew the predicted horrific outcome did not occur (e.g. they were still living with their children although they expected during the trauma never to see them again). Thus, during retrieval of the intrusive memories, the patients had difficulties retrieving subsequent information that corrected their original impressions and predictions during these moments. This relative lack of contextual information distinguished between the intrusive memories of trauma survivors with and without PTSD and predicted subsequent PTSD (Michael et al., Reference Michael, Ehlers, Halligan and Clark2004).

Poor integration into the autobiographical memory base as an explanation for intrusive memories

On the basis of these observations, Ehlers and Clark (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) suggested that one of the factors leading to intrusive memories in PTSD is that the worst moments of the trauma memory are poorly elaborated and inadequately linked with their context of relevant subsequent and preceding information and other autobiographical memories. This suggestion builds on Conway and Pleydell-Pearce's (Reference Conway and Pleydell-Pearce2000) model of autobiographical memory. Conway and Pleydell-Pearce proposed that autobiographical memories are transitory dynamic mental constructions, which are retrieved from an “autobiographical memory base”, where each specific memory is stored as part of a general event, which in turn is part of a lifetime period. One of the functions of the incorporation of memories into the autobiographical memory base is thought to be the inhibition of cue-driven unintentional memory retrieval. Poor incorporation of trauma memories would have the consequence that unintentional memories can be easily triggered by matching cues, and are experienced without a context of other information, which would give them a sense of “nowness”. There are several reasons for why such poor incorporation could occur. Ehlers and Clark (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) and Ehlers et al. (Reference Ehlers, Hackmann and Michael2004) highlight the role of cognitive processing during the trauma, in particular data-driven processing (i.e. predominant processing of sensory information), dissociation and lack of binding. Conway and Pleydell-Pearce (Reference Conway and Pleydell-Pearce2000) suggest that during a traumatic experience there are no current goals and plans that may mediate integration of the experience, resulting in an event-specific memory representation with no contextualizing abstract autobiographical knowledge.

Aims of the present study

To our knowledge, no study to date has experimentally tested the hypothesis that trauma memories are poorly integrated with other autobiographical information. The present study aimed to provide such an experimental test in a sample of assault survivors. Script-driven imagery was used to induce memories of (a) the traumatic event and (b) an unrelated negative event that happened at about the same time. We used the speed with which participants could retrieve other autobiographical information during the imagery as an indirect measure of the degree of integration of a memory within the autobiographical memory base. If the worst moments of trauma memories are poorly integrated into the autobiographical memory base, this would delay the speed with which other autobiographical information is retrieved. We expected that participants with PTSD would take longer to retrieve non-trauma autobiographical information while imagining the worst moment of their assault (“hot spot”, Foa and Rothbaum, Reference Foa and Rothbaum1998, Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000)), when compared to (a) participants without PTSD (between-subject) and (b) imagining the worst moment of another negative event (within-subject). In addition, we expected that the delay in retrieval during trauma hot spots would be correlated with re-experiencing, in particular with the “nowness” of intrusive memories, and with cognitive processing styles that are thought to lead to poor integration of trauma memories (dissociation, data-driven processing, and lack of binding; Brewin et al., Reference Brewin, Dalgleish and Joseph1996; Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Hackmann and Michael2004).

Method

Participants

Assault survivors who had been assaulted more than 3 months ago were recruited from the Accident and Emergency Department of an urban teaching hospital in South London via invitation letter (n = 56), as well as through flyers at local news agents (n = 29). Of 85 assault survivors who attended the research session, 74 completed the experimental task described in this paper.Footnote 1 Twenty-five of these (34%) met diagnostic criteria for PTSD according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID, First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams, Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1996). The assaults were mainly physical attacks (96%), and a minority (4%) were sexual assaults. Table 1 compares the demographic and clinical characteristics of PTSD and no-PTSD groups. The PTSD group were less likely to be Caucasian, less likely to be working, and had lower incomes than the no-PTSD group. As expected, the PTSD group reported more severe symptoms of PTSD and depression. The groups did not differ in objective assault severity, as measured by a composite score described below (Dunmore, Clark and Ehlers, Reference Dunmore, Clark and Ehlers1999).

Table 1. Participant characteristics

Notes: 1combined household income; 2equivalent to 11 years of education; 3equivalent to 13 years of education; 4composite score scale: 0–8.

Experimental task

Generation of imagery scripts

Imagery scripts for the assault and a non-traumatic negative event that had happened at approximately the same time as the assault were generated following the procedure described by Blanchard, Hickling, Taylor, Loos and Gerardi (Reference Blanchard, Hickling, Taylor, Loos and Gerardi1994) and Blanchard et al. (Reference Blanchard, Hickling, Buckley, Taylor, Vollmer and Loos1996). Participants gave a detailed account of their assault. To facilitate the identification of a suitable negative event, participants were given a list of negative events (e.g. failing a test, burglary, argument with friends) and asked to choose which one applied to them. They then gave a detailed account of this event. Next, participants indicated which items from a list of bodily and emotional responses (e.g. “heart racing”, “breathing heavily”) applied to them during the assault and the negative event, respectively. They also specified the worst moment of the assault and the negative event, respectively (hot spot). From the participants' descriptions and their reported bodily reactions, imagery scripts were constructed and audio taped (see also Pitman, Orr and Steketee, Reference Pitman, Orr and Steketee1989). These described the events in the second person and in the present tense (e.g. “You are going down the street when you hear footsteps behind you . . .”). Scripts were tape-recorded in a neutral tone of voice. The tapes were timed to last approximately 2 minutes, and included up to five of the bodily responses. All scripts were timed as precisely as possible to reach the worst moment of the assault/negative event after one minute.

Autobiographical memory retrieval during script-driven imagery

The experimental task tested the time it took participants to answer questions from the Autobiographical Memory Inventory (AMI; Kopelman, Wilson and Baddeley, Reference Kopelman, Wilson and Baddeley1989) while imagining the assault and the other negative event described in the scripts. Before the task, participants were instructed to listen carefully to the tapes with their eyes closed, and to imagine the event as vividly as possible, as if they were actually participating in it. The experimenter explained that each tape would be interrupted twice to answer some questions, and asked participants to answer the questions as quickly as possible. Before listening to the tapes, participants answered two baseline questions from the AMI (“Where did you spend last Christmas?” and “When you were a child, where did you live before you went to primary school?”)

The two imagery tapes were then played in counterbalanced order. Each tape was stopped at the worst moment of the assault/negative event at approximately 1 minute, and at the end of the script. At both time points, participants answered questions about autobiographical information from the AMI, such as the place where they spent their last birthday or the name of a teacher. Half of the questions asked about recent memories (e.g. questions about their last birthday or holiday), the other half asked about past memories (e.g. the name of the street where participants grew up, or the name of their primary school). The same questions were used for each participant. Questions were determined randomly for the trauma and negative event tapes, with the restriction that one past and one recent question was asked during each tape condition. Participants' answers were tape-recorded and memories were later transcribed. The latency to retrieve the (first) answer for each question was measured using a stopwatch. When an answer was inappropriate (e.g. no autobiographical memory, or response did not answer the specific question), and participants had been prompted during the task, latencies to subsequent responses to cues were accumulated.

Manipulation checks

Participants rated tape imageability (how much of the tape's description they could picture in their own mind) on a scale from 0 to 100%. For each tape, they also rated the perceived vividness of imagery, the degree to which they felt that the event was happening again, and whether there was something disturbing about the voice on the tape (on scales from 0 to 10). In addition, participants rated the intensity with which they experienced negative emotions (7 items, anxious, angry, sad, furious, hopeless, ashamed, guilty; α = .89 for the assault tape, α = .87 for the negative event tape) and dissociation (3 items, detached, numb, unreal, α = .80 assault tape, α = .85 negative event tape) while listening to each of the scripts, each on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 = not at all, 10 = very much.

Demographic and assault characteristics

Sociodemographic information

A semistructured interview adapted from Halligan et al. (Reference Halligan, Michael, Clark and Ehlers2003) was used to obtain demographic information, and a comprehensive assessment of assault characteristics.

Objective assault severity

Objective assault severity was scored as a composite score from the following severity indices: number of assailants, assault duration, injury severity, and weapon usage (Dunmore et al., Reference Dunmore, Clark and Ehlers1999).

Clinical symptoms and processing measures

PTSD diagnosis and clinical symptoms

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID, First et al., Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1996) was conducted by two trained masters/doctoral level psychologists to determine whether participants met diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Interrater reliability was high, κ = .82 (based on 56 interviews, 2 raters). PTSD symptom severity was assessed using the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS; Foa, Cashman, Jaycox and Perry, Reference Foa, Cashman, Jaycox and Perry1997), a validated and widely used self-report measure of PTSD symptom severity. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery, Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979), a standardized questionnaire of established reliability and validity, assessed the severity of depressive symptoms.

Nowness of intrusive memories

Participants were asked to describe their most frequent intrusion of the assault and rate its “nowness” (the extent to which it feels as if it was happening now instead of being something from the past; Hackmann et al., Reference Hackmann, Ehlers, Speckens and Clark2004) on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 100 (very much). The retest-reliability (1-week interval) in a sample of 44 PTSD patients was r = .68 (Speckens, Ehlers, Hackmann and Clark, Reference Speckens, Ehlers, Hackmann and Clark2006).

Cognitive processing during the assault

Three scales measured the extent to which participants processed the assault in a way that is thought to lead to disjointed memories (Brewin et al., Reference Brewin, Dalgleish and Joseph1996, Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Hackmann and Michael2004). Participants rated how much each statement applied to them during the assault until help arrived, each on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very strongly).

The Data-driven Processing Scale (Halligan et al., Reference Halligan, Michael, Clark and Ehlers2003) is an 8-item scale that assesses the extent to which participants primarily engaged in the processing of sensory as opposed to meaning information during the assault (data-driven processing, e.g. “It was just like a stream of unconnected impressions following each other”). The scale has been demonstrated to predict the development of analogue PTSD symptoms and disorganized narratives following exposure to a distressing videotape (Halligan, Clark and Ehlers, Reference Halligan, Clark and Ehlers2002), and to prospectively predict PTSD symptoms in trauma survivors (Halligan et al., Reference Halligan, Michael, Clark and Ehlers2003; Rosario, Ehlers, Williams and Glucksman, in preparation). The internal consistency was α = .85 in this sample.

The State Dissociation Questionnaire (SDQ; Murray, Ehlers and Mayou, Reference Murray, Ehlers and Mayou2002, α = .88) is a 9-item scale assessing different aspects of dissociation such as derealization, depersonalization, detachment, altered time sense, emotional numbing, and reduction of awareness in surroundings. The SDQ showed good reliability and validity in traumatized and nontraumatized samples (Halligan et al., Reference Halligan, Clark and Ehlers2002, Reference Halligan, Michael, Clark and Ehlers2003; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Ehlers and Mayou2002). It correlates strongly with the Peritraumatic Dissociation Scale (Marmar, Weiss and Meltzer, Reference Marmar, Weiss, Meltzer, Wilson and Keane1997); r = .79 (Rosario et al., in preparation). The internal consistency was α = .92 in this sample.

The Lack of Binding Scale is a 5-item exploratory scale developed for the purposes of the study. It measures the extent to which the participants processed their different experiences during the assault as unconnected events (e.g. “I felt like nothing linked all that was happening together”; “Every moment seemed unconnected to others”). The internal consistency was α = .88 in this sample.

Procedure

The study was approved by the local ethics committees. Assault survivors were contacted by letter and telephone. The nature of the study was described on the telephone and in an information sheet. If interested, participants were invited to attend the research session. In the research session, participants gave written consent after remaining questions had been answered. They then filled in the questionnaires (including a number of questionnaires unrelated to the present study). Participants gave descriptions of their assault and the negative event, and completed the script-driven imagery task. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV followed. Participants were reimbursed with £25 for their time and travel expenses.

Data analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 13.0) was used for all analyses. A series of analyses of variance compared retrieval times for answers to AMI questions between the PTSD and no-PTSD groups (factor group). Seven of the participants had to be excluded from the data analysis of the memory task because they did not fully comply with task instructions (n = 4), or retrieval latencies deviated more than two standard deviations from the mean (n = 3). Excluded participants (n = 7) did not differ significantly in key demographic variables from those that were included (all p's > .167), but reported greater PTSD symptom severity, F(1,71) = 5.88, p = .018. Thus, the final sample comprised 66 participants. A one-way ANOVA compared retrieval times for baseline questions. The main analysis was a repeated measures ANOVA for the imagery hot spots, with group (PTSD vs. no-PTSD) as the between-subject factor and imagery script (assault, negative event) as the within-subject factor. A similar analysis was conducted for retrieval latencies at the end of the tapes, and for the manipulation check variables. To check whether order of imagery scripts influenced the results, a further ANOVA included order of tapes as an additional between-subject factor. For correlational analyses, a difference score was computed by subtracting retrieval times during the negative event hot spot from the respective retrieval time during the assault hot spot. Pearson correlations were calculated as variables were normally distributed. Alpha was set at .05.

Results

Manipulation checks

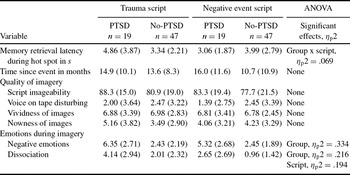

On average, participants retrieved autobiographical information in response to baseline AMI questions in 3.48 s (SD = 2.28 s), which is comparable to other studies of autobiographical memory retrieval (e.g. Conway, Reference Conway, Bjork and Bjork1996). Table 2 shows the manipulation check variables. There were no main effects or interactions in measures of how well participants could imagine the events, namely the ratings of imageability, vividness, nowness, and voice characteristics. The PTSD group rated more negative emotions for both imagery scripts than the no-PTSD group, F(1, 67) = 33.62, p < .001, and greater dissociation, F(1, 67) = 18.45, p < .001. For dissociation, but not for negative emotions, there was also a main effect of script, F(1, 67) = 16.09, p < .001. Trauma scripts led to greater dissociative symptoms in both groups. There were no significant group x script interactions for the emotion and imagery emotionality ratings. There were no main effects or interactions for time since the events.

Table 2. Results of the script-driven imagery task. Means (standard deviations) for autobiographical memory retrieval latencies and manipulation checks for assault and negative event scripts

Note: Ranges: Script imageability: 0 to 100%; Voice characteristics: 0 (not disturbing) to 10 (very much disturbing); Vividness and nowness during imagery, emotions during tape: 0 (not at all) to 10 (very much); ηp2 effect size.

Retrieval of autobiographical information before and after the tapes

Participants with and without PTSD did not differ in the latency of retrieval of autobiographical memories at baseline, M PTSD = 3.51, SD = 2.96; M No-PTSD = 3.48, SD = 2.08; F(1,62) = .01. p = .962.

Similarly, an ANOVA for retrieval latencies at the end of both tapes yielded no significant main effects for script, F(1, 60) = 1.54, p = .22, or group, F(1, 60) = .71, p = .79, and no significant interaction, F(1, 60) = .46, p = .50. Participants with and without PTSD thus did not differ in the retrieval latencies measured at the end of both imagery tapes.

Autobiographical memory retrieval during hot spots

The results for latency of autobiographical memory retrieval during the hot spots in the script-driven imagery task are shown in Table 2 and Figure 1. The ANOVA showed a significant script x group interaction, F(1, 64) = 5.87, p = .018, and no main effects of group, F(1, 64) = .31, p = .578, and script, F(1, 64) = 1.30, p =.258. Participants with PTSD took significantly longer to retrieve autobiographical information during the assault hot spot than those without PTSD, F(1, 65) = 4.04, p = .049, but not during the worst moment of the negative event script, F(1, 65) = 1.79, p = .181, with means pointing in the opposite direction. Estimated marginal means tests revealed that the difference between the two scripts was significant for the PTSD group (p = .043), but not for the no-PTSD group (p = .338) (Figure 1). Order of imagery scripts did not have an effect on retrieval times and did not interact with the other factors.

Figure 1. Mean latencies (in seconds) to retrieve autobiographical information during hot spots of trauma and negative event scripts for assault survivors with and without PTSD. Significant differences are indicated. All other differences were nonsignificant.

Correlations with impaired memory retrieval

Impaired accessibility of autobiographical information as measured by the difference between retrieval latencies for assault and negative event hot spots correlated, as expected, with cognitive processing during the event, namely data-driven processing, r = .35, p = .004, lack of binding, r = .30, p = .014, and dissociation, r = .29, p = .019. It also correlated, as expected, with the perceived nowness of intrusive memories, r = .35, p = .035; and with reexperiencing symptoms as measured by the PDS, r = .40, p = .001.

Further analyses explored whether the difference in retrieval latencies between trauma and negative event script was related to any of the demographic variables that had shown group differences (ethnicity, socioeconomic status, employment). There were no significant associations (all p values greater than .304).

Discussion

The experiment used an autobiographical memory retrieval task during script-driven imagery to investigate the hypothesis that the worst moments of trauma memories in PTSD are disjointed from other autobiographical material. As expected, participants with PTSD took longer to retrieve other autobiographical memories while imagining the worst moment of their assault than participants without PTSD, while no such group difference was found while participants imagined the worst moment of another negative event that had happened at a similar time. Retrieval time differences were unrelated to objective assault severity, indicating that it is not just the complexity of the event contributing to longer retrieval latencies. The group differences could not be attributed to general problems in autobiographical memory retrieval, as the PTSD group showed similar retrieval latencies as the no-PTSD group before and after the imagery tasks. This makes it unlikely that a general deficit in attentional resources was responsible for the findings (Kangas, Henry and Bryant, Reference Kangas, Henry and Bryant2005), although we cannot completely rule out a possible transitory attentional deficit in participants with PTSD during the hotspot. The results could also not be attributed to greater emotional arousal, as there was no group x script interaction in negative emotions during scripts.

In line with our expectations, the PTSD group took longer to retrieve autobiographical memories during trauma hot spots than during negative event hot spots. This finding parallels Ehlers et al.'s (Reference Ehlers, Hackmann and Michael2004) clinical observation that the worst moments of the trauma appear disjointed from subsequent information that updates the impressions the individual had at the time. It would be interesting to explore further what processes impede the integration of trauma memory hot spots with subsequent information.

Thus, the findings provide preliminary support for the hypothesis that trauma memories in PTSD may be insufficiently integrated into the autobiographical memory base, as proposed by Conway and Pleydell-Pearce (Reference Conway and Pleydell-Pearce2000) and Ehlers and Clark (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). Other models of PTSD, such as Brewin et al.'s (1986) Dual Representation Theory, which assumes a deficit in verbally accessible trauma memories, also appear compatible with the findings, as one could assume that such a deficit may lead to slower retrieval of verbal information when the trauma memory is triggered.

Our results add to the growing literature on problems in autobiographical memory retrieval in PTSD. They extend the results of studies showing that trauma survivors with PTSD have problems with recalling trauma memories, in particular its worst moments, as an organized event with a linear temporal sequence (e.g. Evans et al., Reference Evans, Ehlers, Mezey and Clark2007; Halligan et al., Reference Halligan, Michael, Clark and Ehlers2003; Harvey and Bryant, Reference Harvey and Bryant1999; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Harvey and Brewin2007). The present data go beyond these findings of disjointedness within the trauma memory, in that they suggest disjointedness between the trauma memory and other autobiographical information. They also extend findings of an over general memory bias in PTSD (Moore and Zoellner, Reference Moore and Zoellner2007). Trauma survivors, in particular those with PTSD, have been shown to exhibit problems in retrieving memories of specific autobiographical events in response to emotional cue words. Note that in these experiments trauma memories were not explicitly triggered. The present study required participants to retrieve factual (neutral) autobiographical information. The results for retrieval before and after the imagery tapes suggested that people with PTSD do not show a general impairment in retrieving autobiographical information to factual questions, which contrasts the pattern of group differences observed for generating autobiographical memories in response to emotional retrieval cues. Rather, the present study suggested that there was a specific deficit in accessing autobiographical information when people with PTSD recalled the worst moment of their traumatic event, supporting the disjointedness hypothesis.

The Ehlers and Clark (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) model further specifies certain processing styles that are expected to lead to such poor integration of the worst moments of the trauma memory with other autobiographical information, namely data-driven processing and dissociation. Consistent with the model, questionnaire measures of data-driven processing and dissociation during the assault correlated with the delayed retrieval of other autobiographical memories when remembering trauma hot spots, as indexed by the difference in retrieval times between trauma and negative events. An exploratory measure of the lack of binding of information during the assault (Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Hackmann and Michael2004) also correlated with delayed retrieval during the assault script. Lack of integration into the autobiographical memory base is thought to be one of the factors that explain re-experiencing in PTSD (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). In line with this suggestion, the “nowness” of intrusive memories and re-experiencing correlated with delayed retrieval. The pattern of correlations is in line with the theory-derived hypotheses and thus supports the notion that the experimental paradigm indeed assessed an index of poor memory integration.

The experimental task employed in this study was novel, and the results should therefore be interpreted with caution. A number of further limitations need to be noted. First, the study used a cross-sectional design that precludes causal interpretations. Second, due to the nature of the study, only a limited number of autobiographical memories could be elicited. This is likely to have increased error variance and decreased the power of the study to detect group differences. Third, other explanations for the patterns of findings are possible. The PTSD group reported greater negative emotion during both the trauma and the negative event script than the no-PTSD group. Although the pattern of group differences in the questionnaire measures did not explain the pattern of differences in retrieval latencies, it remains conceivable that other differences, for instance in physiological arousal or in transitory attention, may in part be responsible for the observed differences. In future experiments, it would thus be desirable to include further measures, such as psychophysiological measures, and other questions that do not concern autobiographical memories (e.g. mental arithmetic) to test whether the retrieval delays are specific to autobiographical material. Fourth, the no-PTSD group reported some PTSD symptoms, and studying extreme groups may have given clearer group differences. Fifth, we were unable to study whether the results are specific to PTSD as we did not include a further group of trauma survivors with disorders other than PTSD.

In conclusion, this experiment was to our knowledge the first to experimentally investigate the hypothesis that trauma memories lack integration into the autobiographical memory base in PTSD (Conway and Pleydell-Pearce, Reference Conway and Pleydell-Pearce2000; Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). The results support the notion that the moments during the trauma that are later re-experienced are disjointed from other autobiographical material. This would explain the clinical phenomenon that re-experiencing appears to lack the context of other (often subsequent) information that corrected impressions the person had at the time of the event (Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Hackmann and Michael2004) and is characterized by a sense of “nowness”.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by grants from the Psychiatry Research Trust and the Wellcome Trust (Ref. 069777). We thank Dr Edward Glucksman and the staff of King's College Hospital's Accident and Emergency Department for their support; and Johanna Hissbach and Sarah Überall for their help with recruitment and data entry.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.