Nonprofit philanthropy is fast growing in China in terms of donation amounts and the numbers of foundations, charity organizations and intermediary service organizations.Footnote 1 While observers and scholars hold different perspectives on the characteristics of the Chinese nonprofit and philanthropic field, there is consensus that internet and giant tech companies play a critical role in shaping it.Footnote 2 Solicitation of public donations through online platforms has been permitted since 2013, and has expanded massively ever since. Figure 1 shows that although online donations account for a small portion of the total annual giving in China, the increase in that portion is remarkable. In 2013, online giving accounted for only 0.4 per cent (40 million yuan) of total annual giving; in 2020, that figure was 2.2 per cent (3.17 billion yuan). The number of individual donations has similarly risen. In 2013, individuals cumulatively made 44 million donations. In 2020, this number increased 20 times to 8.46 billion individual donations, an increase largely enabled by digital platforms. According to a recent report, online fundraising is now one of the three major financial sources for civil associations, alongside government funding and foundation grants.Footnote 3

Figure 1. Overall Donations and the Proportion of Online Donations in China, 2013–2019

Source: Online donation data from 2013–2016 is from Bain and Company 2018. Online donation data from 2017–2019, the total donation amounts and online donation behaviour from 2013 to 2019 are from Yang and Zhu Reference Yang and Zhu2020. Since the 2016 Charity Law classifies donations given through crowdfunding platforms like Waterdrop (shuidichou 水滴筹) as personal help, they are not included in philanthropic giving.

Scholars and public figures are ambivalent about the prevalence of digital philanthropy and the philanthropic practices generated and transacted on digital platforms.Footnote 4 On the one hand, some observers credit this newer form of soliciting donations via digital platforms with disrupting conventional fundraising practices in China. To emphasize the potential power of digital philanthropy, some have even called these social media-driven charity projects “subversive charity” for soliciting microdonations through online votes to implicitly rebuke the government.Footnote 5 On the other hand, some scholars caution against the inevitable marketization effect on the civil associations that participate in digital philanthropy, as the giant tech companies that represent powerful market forces may encroach on civil society.Footnote 6 Although recent studies have focused on Chinese nonprofit organizations, foundations and digital impacts, few studies examine the intersection of local politics and online philanthropy.Footnote 7 The research on online crowdfunding is predominately focused on projects in urban settings or those initiated by influential online actors and well-established organizations. The perspectives of rural grassroots organizations in less privileged areas remain largely unexamined.Footnote 8

To fill this gap in the literature, we examine the founding and development of SW, a county-level grassroots child welfare organization working in a rural part of Shandong province, and its evolving relationship with the local government and online crowdfunding events. We chose SW as a case study not only because of its relative success in the 99 Giving Day (jiujiu gongyiri 99 公益日) but also because of its location in an under-resourced area that made online crowdfunding success pivotal to facilitating its formalization and professionalization.Footnote 9 This distinguishes our case study from existing studies that tend to focus on online charity projects launched by more established organizations in urban and NGO-dense areas or by key opinion leaders (KOLs).Footnote 10 Our proposed research question focuses on how online crowdfunding campaigns influence rural grassroots organizations and local politics.

The 99 Giving Day is the largest and most successful crowdfunding event in China in terms of the total amount of donations collected and number of participants.Footnote 11 It was launched on 9 September 2015 by the Chinese internet giant, Tencent (Tengxun 腾讯),Footnote 12 with the aim of scaling up charitable giving by offering matching funds through the Tencent Foundation and other business corporations. To participate, charities, nonprofit organizations and foundations list their projects on the online charity platform. In 2020, the 99 Giving Day raised more than 2.32 billion yuan in public donations over three days. Adding in the matching donations from the Tencent Foundation (0.35 billion) and other corporations (0.35 billion yuan), the event raised more than 3.044 billion yuan in total.Footnote 13 The most recent 99 Giving Day event in 2022 ran for ten days and raised 3.3 billion yuan.Footnote 14 This study uses the case of SW, a grassroots organization in rural Shandong, to answer our research question. Prior to 2015, SW functioned as an informal, online interest group. The founders then registered SW as a formal nonprofit organization in order to participate in the 99 Giving Day event.

Our analysis begins with a review of the current literature on Chinese digital philanthropy and its implications for local politics. We follow this with a discussion of the case of SW, examining its founding and evolution from a virtual volunteer-based group to a county-level social welfare organization. We present three main findings: professionalization, local mobilization and soft-budgeting (based on János Kornai's concept).Footnote 15 We then discuss the implications of our research, providing an updated understanding of the changing relationship between technology, local governance and grassroots organizations.

The Impact of Digital Philanthropy on Grassroots Organizations in China

Digital philanthropy in contemporary China can be traced back to the introduction of the internet in the late 1990s.Footnote 16 At that time, there were sporadic cases in which individuals used online bulletin board systems (BBS) to solicit support. These activities were typically organized by individuals rather than through a dedicated giving platform.Footnote 17 The current understanding of “digital philanthropy,” however, is a relatively recent phenomenon. It began when tech giants like Tencent and Alibaba set up corporate foundations in the late 2000s. Subsequently, following the promulgation of the New Charity Law in 2016, the Ministry of Civil Affairs began allowing philanthropic foundations to fundraise on online public charitable platforms.Footnote 18

The boom in digital philanthropy has been enabled by giant tech companies’ online platforms and super apps.Footnote 19 These platforms allow unconventional actors to enter the traditional charity field. In the past, philanthropy was organized by governmental or semi-governmental organizations such as the Chinese Red Cross. This older model was considered less efficient, more prone to corruption and, most importantly, less effective at solving social problems. Now, online celebrities with millions of followers use their public influence to raise awareness of certain charitable causes.Footnote 20 With the backing of powerful tech companies, digital philanthropy is believed to have the potential to transform charitable giving and empower nonprofit organizations.Footnote 21

In their response to the push to transform traditional charity, Chinese tech giants have established corporate foundations as their charitable arms. The growing number of these foundations has been the focus of recent studies.Footnote 22 Digital philanthropy is especially favoured by social-purpose businesses like social enterprises as it offers a flexible channel for aspiring social entrepreneurs to launch organizations for social causes.

Following the passage of the 2016 Charity Law, optimism about the potential of digital philanthropy abounded. For example, the global nonprofit giant United Way and the consulting firm Bain and Company co-published a report entitled, “Digital philanthropy in China: activating the individual donor base.”Footnote 23 The report highlights the potential of digital philanthropy to transform the Chinese charitable status quo by expanding the individual donor base. According to the report, most charity donations are made by corporations, and individuals account for only about 20 per cent of all charitable giving. In this regard, because digital philanthropy is highly accessible, it is a more effective means of engaging individuals than traditional fundraising models (for example, street solicitation). Digital philanthropic projects no longer need to be affiliated with formal organizations to be successful. For example, “Free lunch” (mianfei wucan 免费午餐) is a Weibo-based philanthropic campaign that has gained nationwide influence. Kellee S. Tsai and Qingyan Wang's study on Weibo-initiated micro-charity projects (weigongyi 微公益) such as “Free lunch” suggests that crowdfunding campaigns (gongyi zhongchou 公益众筹) have limited influence on setting policy agendas unless they have gained government support.Footnote 24 Furthermore, these online charity projects are hardly subversive in that their success depends on close alignment with the national policy agenda. Although their study shows why some crowdfunding succeeds at the platform level, the local processes, including implementation and negotiation between different organizations, remains underexplored. As Figure 2 demonstrates, Sina Weibo, despite being a widely popular subject for scholarly research in this field, accounts for only a small portion of online giving. In comparison, Tencent facilitates 100 times more donations than Weibo, but the impact of digital philanthropy conducted via Tencent by grassroots organizations has not been examined in depth.

Figure 2. Donations on Three Online Giving Platforms

Sources: We derive some information from Song, Lee and Han Reference Song, Lee and Han2023. The 2021 Tencent and Alibaba data are from the Ministry of Civil Affairs, https://www.mca.gov.cn/article/xw/mtbd/202205/20220500041907.shtml. Accessed 3 February 2023.

Tencent's high online donation rate can be attributed to its 99 Giving Day campaign, which was launched in 2015. Although the 99 Giving Day may seem similar to Giving Tuesday, there are significant differences.Footnote 25 Giving Tuesday is organized by a nonprofit organization and lacks its own social media platform. In contrast, the 99 Giving Day is a well-coordinated event mobilized on Tencent's WeChat platform and incorporates various online business, social media and advertisement platforms from 7 to 9 September. Donations during the 99 Giving Day event primarily come from two sources: direct donations from individuals to specific projects, and matching donations from corporations. Tencent plays a crucial role by offering matching funds, hosting the event on its platform infrastructure, providing technical support to participating nonprofits and screening charity projects. According to Tencent's public data, in 2015, Tencent and other private corporations contributed over 100 million yuan in matching funds; in 2019, the matching funds totalled over 700 million yuan.Footnote 26 The number of projects supported by the 99 Giving Day has also increased, from 2,000 in 2015 to over 10,000 projects in 2022, benefiting 2,500 social organizations nationwide.Footnote 27

The 99 Giving Day's success in becoming China's largest and most influential crowdfunding event is attributed to Tencent's involvement and its mega platforms. Tencent's role in setting the rules and guidelines for fundraising aligns with the recent findings on market encroachment serving as an alternative to civil society governance.Footnote 28 The existing literature on the state–society relationship has found that Chinese civil associations are learning to “coexist” with the tightening state control and becoming more dependent on the government for their operations.Footnote 29 With the rise of powerful foundations backed by big companies, Chinese civil associations’ already limited autonomy may be further curtailed.Footnote 30 For example, Weijun Lai and Anthony Spires highlight the potentially disruptive effects of market forces on Chinese NGOs, which could “derail [the already limited space of] civil society development.”Footnote 31 Some scholars have claimed that NGOs engaging in strategic collaboration with the government are more in the “non-critical realm of civil society.”Footnote 32 Not all scholars agree with the negative assessment of the impacts of marketization. Jianxing Yu and Kejian Chen compare nonprofit marketization in China and the US and conclude that while marketization may undermine civil society in the Western context, the process of marketization brings about autonomy, transparency and accountability in China.Footnote 33 However, none of the extant studies examine how online crowdfunding events transform the rural grassroots organizations and local politics.

Methods and Data

The sources for our study come from a year of digital ethnography of SW's crowdfunding mobilization process and three field trips to the county between 2020 and 2022 by the third author during the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2018, the Shandong Province Charity Federation, with which SW is affiliated, raised around 10 million yuan during the 99 Giving Day; SW alone raised more than 6 million yuan. According to the 2018 Tencent public information on county-level organizations, SW ranked among the top 30 organizations with respect to the total amount raised, alongside mostly larger GONGOs and national private foundations.Footnote 34

We followed the ethical guidelines to obtain informed consent from participants before interviews and observation. Because the research was conducted during the pandemic and so with travel restrictions in place, the third author acted as the local research coordinator, interacting with the research participants in an effort to understand offline mobilization dynamics. We closely monitored the online activities of SW before, during and after the 99 Giving Days in 2019 and 2020. In addition to following the organization's public WeChat account, we obtained permission from SW to join the internal WeChat group for SW's volunteers and leaders. SW has two major WeChat working groups: a daily working group with 162 people and a special taskforce group formed during the 99 Giving Day with 80 people. Most of SW's members are unemployed women aged between 40 and 50 who have been with SW for four years on average. The founder and the Party secretary, both men in their early forties, are the only full-time staff. In total, we interviewed ten core staff members involved in the 99 Giving Day for about 1.5 hours each, interacted regularly with 30 active volunteers on WeChat, observed some internal meetings online and offline, and held informal conversations with local officials and supporters to gain external perspectives on the development of SW.

An Offshoot of the 99 Giving Day

SW is a grassroots social welfare organization in a rural county, SS, in Shandong province. The county has two subdistricts (jiedao 街道) and 11 townships (zhen 镇), and is made up of a total of 586 villages and ten urban communities. It has a population of around 650,000 people. Although the local government has vigorously promoted industrial development, the average annual income is 17,000 yuan (about $265 USD). Income inequality between urban residents and rural villagers is significant (24,000 yuan and 13,000 yuan, respectively). The county is one of the poorest in the province, ranking 130 out of 137 in respect to average incomes. The total county government budget is around 800 million yuan. In 2020, 22 million yuan was dedicated to social welfare (shehui fuli 社会福利) and about 3 million yuan to child welfare. Those figures have since increased to 25 million yuan for social welfare and 4 million yuan for child welfare.Footnote 35

SW was formed in 2011 (see Table 1), but only formally registered as a nonprofit organization (minban feiqiye 民办非企业) in January 2016, with the mission of providing direct support for rural youth to continue their education. There are currently 15 employees (two full-time and the rest part-time) who are supported by around 170 registered volunteers (40 of whom are core volunteers). Besides the director/founder, the associate director and the Party secretary, staff members are hired from the unemployed workforce in SS county and paid a monthly salary of 1,000 yuan. SW's founder is not a formal civil servant but a contract employee working in the county government. Owing to the success of SW, the county government allows him to maintain his government position while working full-time for SW.Footnote 36

Table 1. SW's Institutionalization, 2011–2022

At the time of writing, SW had visited 5,200 families in 596 villages, supported 1,901 children and youth, and raised over 17 million yuan in funds since it was formally registered. SW relies mainly on overheads from its fundraising (around 5 per cent) to finance its daily operations. At first glance, SW may look like any other grassroots social organization that aims to alleviate rural poverty and help left-behind youth. However, the 99 Giving Day has had a deep impact on SW's organizational development since its founding, resulting in its inevitable entanglement with local politics.

Table 1 summarizes SW's evolution from an online photography hobby group to a registered social organization. Initially, SW operated as a local branch of an online provincial-based photography group and from 2011 was run entirely by volunteers. Its primary goal was to capture local images, some featuring local children, during visits to rural villages. Occasionally, the volunteer photographers helped to raise online donations for these children. The voluntary and sporadic sharing of these photos gradually attracted more public attention and new volunteers. In 2014, SW started focusing on the plight of left-behind children and created profiles of these children on Weibo to attract additional public donations.

This change in SW's mission significantly increased the organization's financial burden. One of the founding members shared that, back in 2015, there were more than 300 cases in need of assistance, but that the organization lacked the resources to support them.Footnote 37 The passive nature of posting children's profiles online to raise funds did not guarantee a steady stream of donations. Besides posting the children's profiles on Weibo, the volunteers tried to publicize cases through a mailing list and by posting on major foundations’ public accounts, but these efforts did not generate consistent donations either.

A turning point came in 2015 when one of the founding members came across a story about successful fundraising campaigns featuring children in difficult circumstances during Tencent's 99 Giving Day. These campaigns inspired SW's founding members to evaluate the possibility of using online fundraising platforms to raise much-needed resources for disadvantaged children. As the founder recalled:

[Back in 2015] when every effort we could think of to raise money [for the children] had failed, we opened the front page of the Tencent Foundation and saw a campaign to support children in difficult circumstances. The fund increased exponentially [within hours]; at first it was 4 million, and the second time [we refreshed the page] it was already at 10 million.Footnote 38

Following this serendipitous encounter with the power of Tencent giving, SW decided to pursue a fundraising campaign on the platform. The next year, the founder of SW established a partnership with the China Charities Aid Foundation for Children (Zhonghua shaonian ertong cishan jiuzhu jijinhui 中华少年儿童慈善救助基金会, CCAFC hereafter). In 2016, after receiving training and guidance from the CCAFC about online fundraising, SW participated in Tencent's 99 Giving Day for the first time. Since then, about 70–80 per cent of SW's annual income has come from online crowdfunding.

Crowdfunding-driven Professionalization

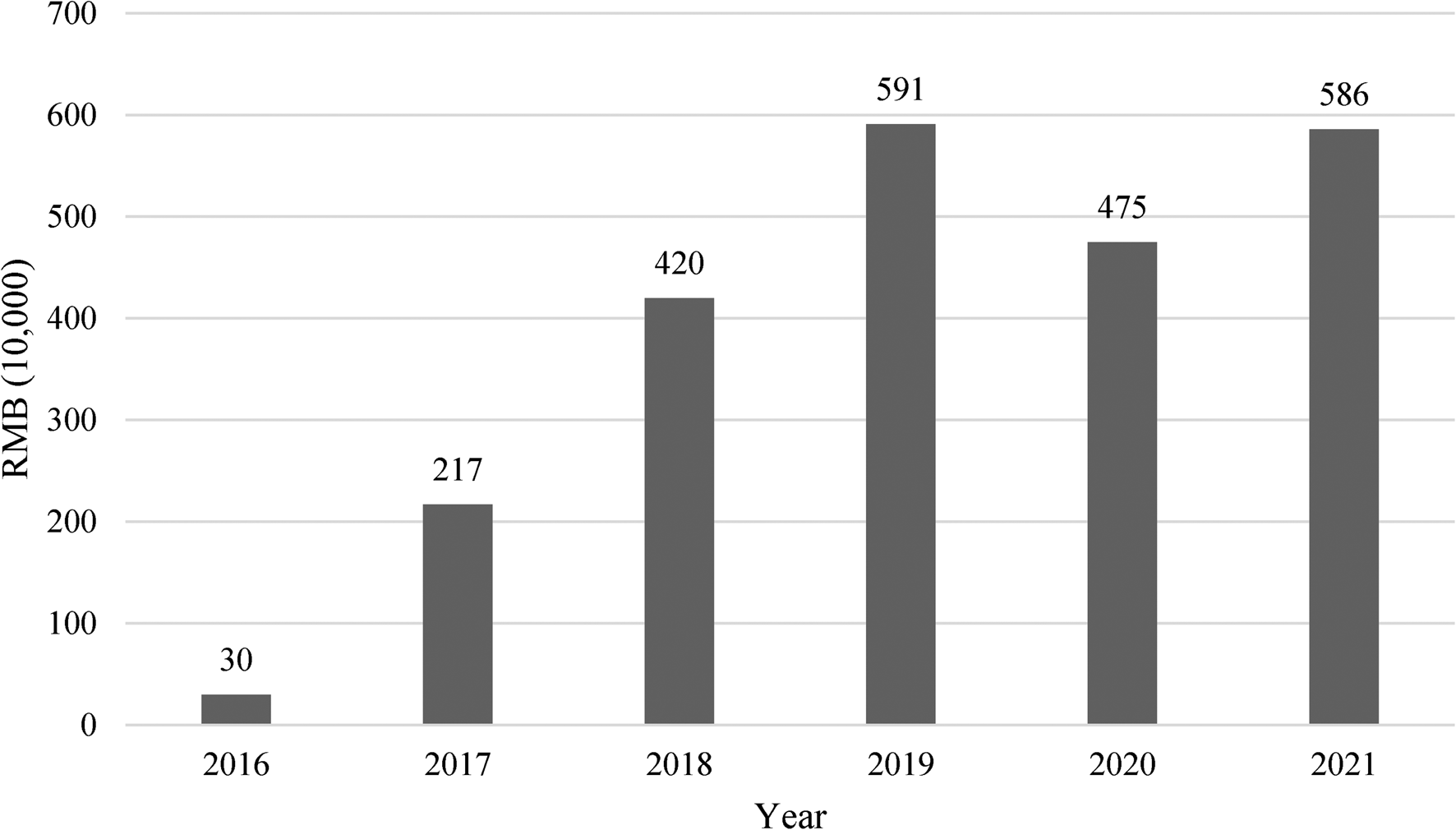

Although still run by volunteers, participation in the 99 Giving Day has transformed SW from an online volunteer group into a formally registered organization. Figure 3 shows the growth in total donations received from the annual three-day event since 2016. In 2019, SW received nearly 6 million yuan in donations during the event; in 2021, despite the Covid-19 pandemic, it successfully raised over 5 million yuan in donations. This stable source of income has enabled SW to embark on more ambitious projects to address the needs of rural left-behind children.

Figure 3. SW's Donations Received during 99 Giving Days

Source: Data provided by SW.

Recent literature has highlighted that many social service organizations in wealthier urban areas receive a large share of their funding from government contracts for public services (zhengfu goumai fuwu 政府购买服务).Footnote 39 In contrast, SW did not receive any direct financial support from the government service procurement scheme until 2020 because of the county government's dire financial status. As Figure 4 shows, the funds raised during the 99 Giving Day have become the main source of SW's operational budget. Currently, SW receives its funding from three primary sources: 70 per cent from online donations, 20 per cent from foundation grants and 10 per cent from individual donations. Among online donations, 90 per cent of all funds are raised during the 99 Giving Day, 40 per cent of which originate outside of SS county. This means that SW's online fundraising campaign has grown beyond the county-level mobilization.

Figure 4. SW's Financial Sources

Source: Data provided by SW.

The 99 Giving Day pushed SW to professionalize. In order to participate, nonprofit organizations like SW are required to be familiar with Tencent's formal rules for the event – for example, eligibility criteria stiplulate that a nonprofit must be formally registered in order to participate. Furthermore, Tencent requires participating organizations to demonstrate transparency and accountability. Before SW's formal registration, online volunteers did not play a crucial role in the donation process. They only shared photos and information about rural children, while the donors themselves were responsible for sending funds directly to the children. Even during the early days of SW, staff members were responsible only for preliminary home visit investigations, recording information, posting online and following up on donations. However, when SW started to participate in the 99 Giving Day, the organization had to establish standardized accountability mechanisms so that donations and beneficiaries could be tracked over time.

During this time, SW professionalized quickly by setting up the first and only information filing system in Shandong that tracked educational assistance for impoverished children. It also drafted the SW code of conduct, provided real time reports for financial disclosures and project status, and made reports on the beneficiaries’ conditions accessible to the general public and donors. The Tencent Foundation further requires that the organization disclose its financial and staff information. After the giving event ends, the Tencent Foundation regularly shares updates and reports on the fundraising projects with donors using WeChat messages. The event platform also offers feedback to the participant organizations. In a sense, receiving donations is not the end goal of the campaign, but rather the beginning of fulfilling campaign promises. An interviewee elaborated: “Participating in the campaign greatly enhances our organization's capacity and the skills of our employees, but it comes with a cost.”Footnote 40 Below, we discuss how crowdfunding rules shaped the development of SW in ways that inevitably led to local government intervention.

Crowdfunding Rules

Tencent establishes the rules and guidelines for the duration of the charity event. Even though these rules may look neutral at first glance, they have a profound impact on SW's overall operations. Below, we discuss three critical rules.

The first rule is the participation rule. The participant organization is not merely a passive recipient of donations; it is an active participant in the process. The event platform asks each participant to set a financial goal (for example, to raise 3 million yuan) and to disseminate the campaign message to a certain number of WeChat friendship circles.

Second is the transparency rule. Participating nonprofits must disclose the total amount of donations received, relevant financial information and the charitable project's progress. Each organization must also disclose its spending at each stage of the project's progression.

Finally, there is the matching-funds rule, which continues to evolve. In 2015, Tencent made a one-for-one matching gift for every yuan donated by individuals. After the first year, the matching amount and how the matching funds are allocated were determined according to a sophisticated algorithm. Other companies also joined Tencent in offering matching funds. This greatly increased the total amount of matching funds donated to participating organizations. In order to maximize matching funds, the nonprofits must be familiar with each corporation's rules for matching donations.

Tencent's 99 Giving Day rules force grassroots organizations to professionalize their organizational structure and practices but, at the same time, they create new issues and additional burdens. A senior project manager at SW told us, “We are very tired of these changing rules. Sometimes, you need to do the chain of games, or like the other time, you need to give a red flower [as a gift on a WeChat page to support the charity project]. Many people will just give up [because of the complex rules].”Footnote 41 Because Tencent has ultimate power in establishing the rules for the charity event, the grassroots nonprofit organizations that rely on the crowdfunding have no choice but to keep themselves abreast of all the changing guidelines. This uncertainty not only affects the nonprofit organizations but also the private companies that take part in the event as matching fund providers. One long-term fundraising volunteer at SW further told us:

The rules of the 99 Giving Day event change every year. We have to study and then brief our donors. We spend a lot of time [trying to decipher the rules] each year. However, the rules have become more and more complicated and are often released only few weeks or days before the event. We need to update the businesses that are interested in supporting us, because if they cannot understand the rules, they will not donate to us, and consequently we cannot get matching funds.Footnote 42

The increasingly elaborate event rules add to the grassroots organizations’ administrative burdens as they attempt to complete the complicated tasks. Our fieldwork revealed that some organizations use various means to make fake donations to their projects in order to earn more matching funds – an action known as a donation trap (taojuan 套捐). Donation traps are possible because matching funds are based on the total number of individual donations each project obtains. For example, some nonprofit organizations will donate their own funds or ask their employees to donate a certain amount to qualify for matching funds. According to a Tencent report, such fake donations account for 1.26 per cent of all matching funds.Footnote 43 However, the system cannot identify every fake donation.Footnote 44 Thus, the platform constantly changes its requirements for nonprofit accountability and transparency. In turn, this creates additional pressure and tremendous amounts of administrative work for grassroots organizations.

The associate director of SW commented on how SW needs to mobilize more people to achieve this kind of market-driven professionalization, “99 Giving Day is [Tencent's] public advertising event. The number of participants is an indicator of success. Tencent wants more participants to advertise it, and thus we must engage with more and more people.”Footnote 45 In this regard, thousands of nonprofit organizations become the platform's instruments and are used as symbols of the event to publicize and popularize the platform to drive online traffic.

Crowd Mobilization for Crowdfunding

The 99 Giving Day is the most important factor driving SW's professionalization, and SW's operational sustainability relies heavily on successful crowdfunding during this single event (donations from the event make up more than 60 per cent of is operating budget). Ironically, while the crowdfunding platform empowered SW to expand into its current form, SW must spend most of its time and energy ensuring its success in the 99 Giving Day campaign. SW's preparations for the three-day charitable event begin at least three months in advance, with staff mobilizing all possible local resources and connections. In short, the campaign requires a massive mobilization effort at the local level as well as the local government's endorsement. We further analyse SW's crowdfunding campaign through an examination of its social media and offline mobilization.

Conducting an online crowdfunding campaign requires a level of familiarity with the internet. In the words of SW's associate director, “If there were no internet, [county-level] grassroots organizations [like us] would never develop.”Footnote 46 Even though many of SW's volunteers, including the founder of SW, have experience working in state-related organizations and are familiar with promoting different welfare initiatives, a successful online fundraising campaign requires a more emotive and powerful online narrative in order to attract a netizen's attention.Footnote 47 The volunteers all agreed that the internet presents both an opportunity and a challenge for small grassroots organizations. Sometimes, with a compelling narrative to catch people's attention, smaller grassroots organizations can succeed in an online campaign even while lacking resources or staff.

Before its participation in the 99 Giving Day, SW's founders maintained several digital platforms simultaneously – an official website, Weibo account, WeChat account and an online broadcasting channel. However, publishing news on official channels alone is not enough to guarantee successful digital mobilization. Beyond these formal channels, SW uses WeChat groups and WeChat Moments to update donors on the campaign's progress and to share campaign information. Other online communication channels include Baidu Baike, Weibo and Douyin, all of which play a role in the online mobilization scheme.

During the campaign mobilization period, SW asks volunteers to associate their WeChat handle with the campaign and to create regular posts to circulate financial and project status updates in their WeChat Moments. According to our interviewees and our observations of SW's meetings, a successful online fundraising campaign relies heavily on offline mobilization and local coordination, such as holding regular weekly team meetings to build solidarity. Volunteers and employees feel more comfortable using this traditional style of face-to-face meeting to discuss fundraising goals and strategies. According to one volunteer:

The WeChat group is good for reporting work-related activities but is not suitable for people to share their reflections. Writing alone cannot properly and accurately express what they really feel. People are reluctant to provide feedback [in WeChat groups]. [The weekly meeting] provides a better atmosphere to have a face-to-face discussion on the online campaign.Footnote 48

Alongside creating a comfortable and decentralized offline participation model for its volunteers and employees, SW's offline mobilization involves extensive engagement with different local actors. Because of the matching funds process and its complex set of rules, SW needs to maximize the number of individual donors in order to maximize the matching funds. Securing pledges from local actors is an important task as it is easier to secure donations through local networks than it is to attract non-local support. For example, SW holds nightly workshops from 1 September (one week prior to the event's launch date) onwards to explain the 99 Giving Day's rules and guidelines to different local stakeholders (such as schools and local business owners). Furthermore, several months before the event, SW sends out volunteers and staff to visit every village and business in the county to gather support for the 99 Giving Day. These efforts are positively reflected in SW's online giving statistics, in which donations from organizations account for more than 70 per cent of the total funds raised, while individual donations account for less than 30 per cent.

According to SW's leaders, this offline mobilization strategy is the primary reason for SW's stellar countywide fundraising records in the past few years. However, instituting successful crowd mobilization is not an easy task in rural regions.

Engaging with Local Politics as a Performance Indicator and Welfare Soft-budgeting

According to the 2020 annals for the county, SW's performance in the 2019 99 Giving Day as the number one participant organization in Shandong was ranked fifth in the top ten news events of 2019. SW has a conspicuous presence in the county annals because it has been the top donation recipient in the entire province for the past three consecutive years. The annals praised SW for creating a welfare model in the county.Footnote 49 Above, we noted that SW's founding was made possible by the 99 Giving Day; however, its continued success in the event would not have been possible without its ongoing engagement with local politics and support from the local leaders. Although our fieldwork and interviews indicate that SW is cautious in maintaining its relative autonomy, in reality, rural grassroots organizations are dependent on local government support. The director of SW explained: “Without the support of the government, it is impossible for any grassroots social organizations to grow [in the county].”Footnote 50

However, the relationship between SW and the local government is not as straightforward as some may think. In fact, even though SW's founders and key members all had government work experience, their time in the state sector did not help them to secure any direct government funding for SW owing to the county's poor financial status. Nevertheless, their government-affiliated experience did facilitate their work in substantive ways. Our fieldwork reveals that before SW was formally registered, it frequently received guidance from other, more established county-level organizations through the director's personal connections. Largely because SW's work with left-behind children complemented the county's welfare services, SW was even permitted to host its official website on a government server.Footnote 51 The local office of poverty alleviation even helped SW to establish its online file management system.

When SW was officially registered in 2016, the local bureau of civil affairs acted as its supervising agency. To be eligible for public fundraising, SW first partnered with the CCAFC, a Beijing-based national public foundation, in 2016. SW's unexpected crowdfunding success significantly raised the organization's profile across Shandong and, as a consequence, the provincial charity federation wanted a part of this.Footnote 52 In 2018, the Shandong Province Charity Federation (Shandongsheng cishan zonghui 山东省慈善总会) became SW's online fundraising collaborative partner. This partnership change signalled SW's rising status across the province and its inevitable co-evolution with local politics.

According to our interviewees, the local government did not actively engage with the organization until 2019, when SW became one of the most successful grassroots charity organizations in Shandong. Before 2019, preparations for the 99 Giving Day were the sole responsibility of SW. Beginning in 2019, the local government became actively involved with SW's offline mobilization. This positive engagement, led by the new county mayor and the county deputy secretary, encouraged all government units to support SW's crowdfunding as part of a local initiative to end poverty.

Beginning in 2019, county government leaders asked different government units, including local schools, to participate in SW's various campaigns. The county government saw SW as a necessary step towards alignment with the new policy initiative on poverty reduction. The government's active involvement mobilized the local education system to support SW's crowdfunding projects and, as a result, primary schools were mobilized in the 99 Giving Day campaign. With active involvement from students and their parents, the scale of SW's mobilization expanded massively beginning in 2019. Most importantly, the government's involvement in SW's campaign did not directly force participants to donate nor did the government set a donation goal or a strict performance benchmark. Participation was voluntary. SW's associate director explained: “Setting a [strict] benchmark and forced donations will incur strong resistance [which we try to avoid].”Footnote 53

To further leverage SW's capabilities, the county government allows SW to be in charge of new volunteer sites and publicizes SW's activities on its official media. For example, in 2019, the county government helped SW to establish ten volunteer teams in different villages and provided them with office space. SW was then asked to join the “Don't forget the original mission” (buwang chuxin 不忘初心) propaganda team. An interviewee recalled that during the event, the county Party secretary encouraged other government leaders to join SW's offline events and even helped to sew a blanket for an impoverished youth.Footnote 54 The county mayor even brought gifts when visiting volunteers during the 99 Giving Day fundraising event in 2019. During our fieldwork, we learned that SW's success during the 99 Giving Day was acknowledged by higher-level government and Party units. For example, the provincial Communist Youth League asked SW to lead a province-wide project; however, owing to SW's organizational capacity, the project was ultimately implemented in several selected locations in collaboration with other local nonprofits. In 2021, SW was recognized as an exemplary model for grassroots organizations in rural China by the deputy director of the China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation at a national event on internet charities.

Maintaining a good relationship with the Party and with the local government go hand-in-hand. SW's Party unit (dangzhibu 党支部) was established in 2017, and its Party secretary was appointed by the higher Party organization. Our fieldwork revealed that more than 60 per cent of SW's volunteers work within the Party system or in other government-related organizations (for example, as school teachers). SW's Party secretary acted as an auxiliary to the director. While our case supports a long-standing observation about Chinese civil associations, especially those in rural areas, that government control leaves little autonomy in the social sector, it is more of a co-dependency.Footnote 55 In the case of SW, staff and organizational leadership do not view government involvement or Party penetration as a hindrance. They are well aware that in order to help rural youth, they cannot work independently. The founder of SW explained to us: “You could never develop your own organization if you cut off ties with the Party. Without the support of the Party, your organization will be small. A charity organization with a well-developed Party organ is always better off than those without one.”Footnote 56 However, he also recognized the dilemma that “while Party building sometimes becomes a formality, SW's work relies heavily on Party members. Major participants [both volunteers and paid employees] are mostly Party members. It is these people who sacrifice their vacations to lead activities and do the most difficult jobs. Therefore, in our organization, the leadership is mainly composed of Party members.”Footnote 57

Returning to our question about how the 99 Giving Day event impacts local politics, we find that on the one hand, the event hardly alters the conventional practices of local politics. The county government and the Party organization are already tightly enmeshed with the operations of local social organizations. However, our findings show that even as an organization in a poor county with an annual social welfare budget of only slightly more than 20 million yuan, SW's success in the 99 Giving Day event brings significant funds into the county which supplement the deficiencies in the government budget. In other words, there is a tendency for the local government to view SW's mobilized funding during the 99 Giving Day event as a form of “welfare soft-budget” to finance welfare services that the government cannot afford to provide on its own. This may explain why the local government has actively involved itself in fundraising and campaigning activities since 2019. Furthermore, the success of SW in the 99 Giving Day, a high-profile nationwide event, has enhanced the county's national standing. Before this event, the county was just another unknown, poor, rural area, which attracted little provincial, let alone national, attention. SW's successful fundraising, especially after being featured on Tencent's fundraising platform, has raised this county's profile. The positive feedback has further endorsed the county government's role in supporting SW's model of social welfare.

Besides the deep entanglement with local politics, SW's organizational development and fundraising model could be viewed as products of the 99 Giving Day. Unlike government contracting, online crowdfunding platforms offer grassroots organizations an opportunity to fundraise for resource-intensive charity projects that would otherwise fall through the cracks at the government level. Success in online crowdfunding enhances the grassroots organization's bargaining power with the local government as it not only brings in significant amounts of donations that can cover the local welfare deficit but it also draws the attention of higher levels of government to the local government's performance – a powerful incentive for relationship-building. In this regard, success in the 99 Giving Day empowers SW both in its organizational capacity and its public legitimacy. However, the crowdfunding platform's empowering effects may be limited to organizations whose agendas align with the overall national policy, like rural revitalization. Nevertheless, not all rural organizations can easily replicate the successful online crowdfunding path of SW. The leaders of SW recognized that its success was partially owing to the relative open attitude of the county leaders in allowing SW to experiment and even expose the “uglier” sides of the county social welfare situation during the online campaign.

Conclusion

The influence of giant tech companies and their online platforms has transformed China into a platform society and many daily activities are now performed on digital platforms.Footnote 58 The country has also witnessed the “platformization” of its nonprofit and philanthropic spheres.Footnote 59 While existing studies have begun to evaluate the influence of online charitable campaigns, our study fills the research gap on the connection between crowdfunding campaigns and local politics. Using the case study of a grassroots civil organization in rural Shandong, our study contributes to the theoretical debate on the entanglement of market forces and local politics in the under-resourced local nonprofit field.

Empirically, our study presents the following findings. First, Tencent's 99 Giving Day is an incubator for rural grassroots organizations. Without this event, many grassroots organizations in resource-poor areas have little chance to formalize. Second, to engage with this platform, grassroots organizations must professionalize in order to fit the standards set by the platform. Third, successful online crowdfunding requires extensive offline mobilization practices to satisfy the matching fund rules set by the platform. Fourth, to effectively mobilize offline, support from the local government is necessary. However, the crowdfunding campaign's success may later be co-opted as a form of soft-budgeting to cover deficits in local government's welfare expenditure, And, fifth, a fundraising campaign's success may be regarded as a performance indicator for the local government. This creates an incentive for the local government to be actively involved.

Theoretically, our findings neither reject nor endorse the marketization thesis or the empowerment thesis on digital philanthropy.Footnote 60 In our case, market forces represented by the platform do have a profound impact on grassroots organizations. Their ever-changing rules even become a burden for some organizations. At the same time, market forces help to upgrade grassroots organizations by offering seed funding, training programmes and requirements around accountability and transparency. The close relationship between platforms and grassroots organizations does not indicate that the market forces are unchecked. In our case, the local government carefully monitored the fundraising campaigns and became involved when the project succeeded. The local government and Party units are the most powerful actors in rural areas, and digital philanthropy, rather than being “subversive,” facilitates the co-evolution of grassroots organizations and local politics. Furthermore, nonprofits and charities with government backgrounds can easily capitalize on the opportunities offered by crowdfunding platforms. The involvement of these state-affiliated organizations will further reduce the donation share that grassroots organizations attract through the platforms. Nevertheless, for grassroots organizations in poorer areas, crowdfunding platforms offer a rare opportunity to fulfil their welfare missions. We reveal a complicated and dynamic relationship between different social actors. Our case study shows that internet crowdfunding empowers not only grassroots organizations but also local state actors. This finding forces us to carefully re-examine the over-simplified theoretical frameworks that attempt to explain the government–market–nonprofit relationship in China.

Finally, our study only represents one type of grassroots organization, whose mission fits with the government's broader policy agenda. For grassroots organizations like SW, their mission alignment with poverty alleviation contributes to the overall stability of the local society. Thus, they are more likely to receive support from the local government after their crowdfunding is successful. Other studies have already shown that certain types of projects may be excluded from participating in the 99 Giving Day.Footnote 61 In this regard, the platform companies serve a role in disciplining social organizations to fulfil the government's agenda.Footnote 62

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the members of SW for generously sharing their valuable information. Qi Song received support from the Major Project of the National Social Science Foundation in China, entitled “AI and precise international communication” (Project No. 22&ZD317). Ling Han acknowledges support from the research start-up fund from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contributions made by students Bixuan Jia and Zhengkang Chen from Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Competing interests

None

Ling HAN is an assistant professor in the gender studies programme at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. As a sociologist, her research focuses on the intersection of gender, digital platforms, technology and nonprofit organizations. She co-leads the Singapore research team for Stanford University's Civic Life of Cities Lab. Her latest project delves into exploring the meanings of work among young social innovators and platform workers in greater China. She leads the research cluster of Gender and Digital Wellbeing and is working on a book manuscript about the politics of care and the nonprofits in China.

Chengpang LEE is an assistant professor in the department of applied social sciences at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. He was previously a postdoctoral fellow in China public policy at the Ash Center of the Harvard Kennedy School and worked at the National University of Singapore. His recent research focuses on the transformation of social science knowledge, and medical and health issues in the greater Chinese world. He is currently collaborating with colleagues to build a large-scale computer-assisted database on epidemics and diseases in China since the Ming Dynasty.

Qi SONG is a lecturer in the College of Public Administration at Huazhong University of Science and Technology. He earned his PhD from the School of Journalism and Communication at Peking University. His primary research interests encompass political sociology and internet politics, with a particular focus on China. Currently, he is engaged in a project exploring the relationship between the internet, civic engagement and local governance in China.