Introduction

Nursing homes are facing the challenge of delivering quality care to a rapidly growing number of older adults (Quadagno and Stahl, Reference Quadagno and Stahl2003; Towers et al., Reference Towers, Palmer, Smith, Collins and Allan2019). Researchers have examined the extent to which the quality of nursing care such as organisational characteristics (e.g. propriety status, urban versus rural), other structures of care (e.g. material resources) and processes of care (e.g. type of care provision) affect older adults’ physical health and psycho-social adjustment (see Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Anderson, Brode, Jonas, Lux, Beeber, Watson, Viswanathan, Lohr and Sloane2013). Some interventions have been found to improve the processes of care for residents of nursing homes (Sloane et al. Reference Sloane, Hoeffer, Mitchell, McKenzie, Barrick, Rader, Stewart, Talerico, Rasin, Zink and Koch2004; Fritsch et al., Reference Fritsch, Kwak, Grant, Lang, Montgomery and Basting2009). Reviews of the research (see Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Anderson, Brode, Jonas, Lux, Beeber, Watson, Viswanathan, Lohr and Sloane2013) have concluded, however, that there is insufficient empirical evidence to support the effectiveness of the factors affecting the qualities of nursing homes on physical health and psycho-social adjustment of the residents. The current study investigated the relation between a process of nursing home care, in the form of residents’ trust beliefs in nursing home carers (NHCs), and psych-social adjustment to residential care.

During pandemics, such as COVID-19, NHCs play a role in the residents’ physical and mental health by engaging in the requisite health and safety regimes (see Hodgson et al., Reference Hodgson, Grimm, Vestesson, Brine and Deeny2020). With respect to more normal nursing home routines, NHCs provide a range of services to the residents such as helping with immediate needs and providing emotional support. As a result, older adults’ trust beliefs in NHCs to carry out those tasks could be associated, and potentially affect, their adjustment to residential care. Nevertheless, research with children and adolescents indicate that those who hold very high trust beliefs in others are at risk of psychosocial problems (Rotenberg, Reference Rotenberg and Sasaki2019a). Similarly, older adults who hold very high trust beliefs in NHCs could be at the risk of poor adjustment to residential care. The current study was designed to examine those issues.

Conceptualisation of older adults’ trust beliefs in their NHCs

The current study was guided by the Basis, Domain, and Target Interpersonal Trust Framework (the BDT; Rotenberg, Reference Rotenberg and Rotenberg2010, Reference Rotenberg2019b). According to the BDT framework, trust beliefs include expectations that others show: (a) reliability by fulfilling their word or promise; and (b) emotional trustworthiness by refraining from causing emotional harm primarily by acceptance of disclosures and maintaining confidentiality of them.

Reliabilty trust beliefs

Several studies show that individuals’ reliability (as well emotional) trust beliefs in others are concurrently associated with, and longitudinally predict, psychosocial adjustment in children, adolescents and young adults (see Rotenberg, Reference Rotenberg2019b). Regarding older adults, it has been found that their generalised reliability trust beliefs in others are associated with their satisfaction, physical health and longevity (Barefoot et al., Reference Barefoot, Maynard, Beckham, Brammett, Hooker and Siegler1998; Nummela et al., Reference Nummela, Raivio and Uutela2012; Miething et al., Reference Miething, Mewes and Giordano2020). In that context, older adults’ reliability beliefs in their NHCs could play a role in their adjustment to residential care. Specifically, NHCs promise to help older adult residents with their immediate needs (e.g. assisting in meals) and basic daily tasks (e.g. paying bills). If older adult residents believe that their NHCs fulfil promises to help them with their immediate needs and daily tasks then they may be better adjusted to residential care.

Emotional trust beliefs

Young adults’ low emotional trust beliefs in others are concurrently associated with, and longitudinally predict, loneliness and social disengagement (Rotenberg et al., Reference Rotenberg, Boulton and Fox2005). Regarding older adults, researchers have highlighted the importance for care providers (including nurses) to be supportive of older adults’ disclosure of their emotional states in order to understand them and foster their wellbeing and health (Hupcey et al., Reference Hupcey, Clark, Hutcheson and Thompson2004; Corbett and Williams, Reference Corbett and Williams2014). Also, older adults expect that a good nurse provides emotional support to them by being acceptant of disclosure (see Van der Elst et al., Reference Van der Elst, Dierckx de Casterle and Gastmans2012). Finally, older adults’ reminiscing as part of their dyadic relationship with their care providers has been found to foster psychosocial adjustment (O'Rourke et al., Reference O'Rourke, Cappeliez and Claxton2011; Ingersoll-Dayton et al., Reference Ingersoll-Dayton, Kropf, Campbell and Parker2019). If residents of nursing homes believe that their NHCs refrain from causing emotional harm by being acceptant of disclosures and maintaining confidentiality of them (i.e. emotional trust beliefs) then adjustment to residential care is likely.

Loneliness and social engagement in older adults

It has been found that loneliness increases, and social engagement decreases, with age primarily when individuals enter old age and are male (Dugan and Kivett, Reference Dugan and Kivett1994; Tijhuis et al., Reference Tijhuis, De Jong-Gierveld, Feskens and Kromhout1999; Graneheim and Lundman, Reference Graneheim and Lundman2010; Isherwood et al., Reference Isherwood, King and Luszcz2012; Nicolaisen and Thorsen, Reference Nicolaisen and Thorsen2014). Those shifts in loneliness and social engagement with age are associated with the loss of a partner and when individuals move into an old age home. Loneliness and low social engagement are predictive of poor health (e.g. cardiovascular problems), psychosocial problems (e.g. depression) and mortality in old age (Shankar et al., Reference Shankar, McMunn, Banks and Steptoe2011; Ong et al., Reference Ong, Uchino and Wethington2016; Courtin and Knapp, Reference Courtin and Knapp2017; Derwin et al., Reference Derwin, Takeshi, Liman Man Wai and Xin2017). Research shows that trust beliefs in others is concurrently and prospectively associated with low loneliness and social engagement (Rotenberg et al., Reference Rotenberg, Addis, Betts, Fox, Hobson, Rennison, Trueman and Boulton2010). If older adults hold elevated trust beliefs in their NHCs then that could have the potential to decrease their loneliness and enhance their social engagement.

The current study tested the hypothesis that older adults’ trust beliefs in their NHCs would be linearly associated with their adjustment to residential care (high satisfaction with carer, low loneliness and high social engagement with others in the nursing home). In addition to the separate measures, the study examined older adults’ adjustment to residential care as a convergence of their experience of adjustment to residential care. The convergent experience of adjustment to residential care was assessed by the latent factor underlying those three measures.

There is a greater prevalence of women in nursing homes which has been ascribed to age-related frailty of men as care providers (McCann et al., Reference McCann, Donnelly and O'Reilly2012). Research has yielded some gender differences in the correlates of satisfaction with nursing homes. It has been found that the length of stay in the nursing home predicts satisfaction with the nursing home for men but not for women (Claridge et al., Reference Claridge, Rowell, Duffy and Duffy1995). Also, male residents more often complained about technical, impersonal and legalistic issues pertaining to nursing homes, whereas women more often complained about personal care and socio-emotional-environmental issues pertaining to nursing homes (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Nelson, Gruman and Cherry2006). Nevertheless, the research did not provide a definitive basis for expecting gender differences in the relations between trust beliefs in NHCs and adjustment to residential care.

Are there risks of holding very high trust beliefs for older adults?

Researchers have found that holding very high trust (as well as very low) beliefs in others have negative consequences for psychosocial maladjustment during childhood and adolescence (see Rotenberg, Reference Rotenberg2019b). Quadratic (curvilinear) relations have been found between trust beliefs and psychosocial adjustment during childhood and adolescence. In comparison to children and adolescents with the middle range of trust beliefs, those with very high trust beliefs and those with very low trust beliefs have been found to show elevated: (a) internalised maladjustment across time, (b) rejection and exclusion by peers, (c) aggression to hypothetical peer provocation, and (d) aggression to peer provocation in a natural setting (Rotenberg et al., Reference Rotenberg, Boulton and Fox2005, Reference Rotenberg, Betts and Moore2013, Reference Rotenberg, Qualter, Barrett and Henzi2014; also see Rotenberg, Reference Rotenberg and Sasaki2019a). Some studies have shown that the quadratic relations are skewed such that those with very low trust beliefs showed lower psycho-social adjustment than those with very high trust beliefs (see Rotenberg et al., Reference Rotenberg, Boulton and Fox2005). This finding supports the conclusion that holding very low trust beliefs may have more detrimental effects on psychosocial adjustment than holding very high trust beliefs.

Mechanisms responsible for the quadratic relation

Three mechanisms have been advanced to account for the observed quadratic relations (Rotenberg et al., Reference Rotenberg, Boulton and Fox2005, Reference Rotenberg, Qualter, Barrett and Henzi2014). First, individuals with extreme trust beliefs violate social norms and thus they tend to be rejected by others. Second, individuals with very low trust beliefs demonstrate psychosocial maladjustment because they are not inclined to integrate with others socially (e.g. lack friends). Third, and finally, individuals with very high trust beliefs show elevated psychosocial maladjustment primarily because they are at risk of being betrayed, and thus disappointed, by others.

The current study investigated the hypothesis that there would be a quadratic relation between older adults’ trust beliefs in NHCs and adjustment to residential care on each of the three measures and a latent measure. It was hypothesised that adults with very low trust beliefs in NHCs would show lower levels of adjustment to residential care relative to those with a middle range of trust beliefs in NHCs. The study was guided by the notion that NHCs would infrequently demonstrate trustworthiness or sustain trustworthiness across time. Consequently, NHCs would fail to fulfil expectations of being highly trustworthy by those older adult residents with very high trust beliefs who would feel betrayed and disappointed. The measure of satisfaction with carers served a dual purpose. In addition to serving as a measure of adjustment to residential care, it served as a marker of the hypothesised feelings of betrayal and disappointment by older adults with very high trust beliefs in NHCs. The older adult residents who held very low trust beliefs were expected to display very poor adjustment to residential care because of the heightened social withdrawal that accompanies low trust beliefs.

Overview of the study and hypotheses

Older adults residing in nursing homes in the United Kingdom (UK) completed standardised scales assessing reliability and emotional trust beliefs in NHCs and adjustment to residential care (satisfaction with care-giving, social engagement with others in the nursing home, loneliness and a latent measure).

The hypotheses were:

(1) The older adults’ trust beliefs in NHCs would be linearly associated (correlated) with the measures of adjustment to residential care (linear trust-adjustment hypothesis).

(2) The linear relations would be qualified by quadratic relations between trust beliefs in NHCs and each of the measures of adjustment to residential care. It was expected that older adults with very high and those with very low trust beliefs in NHCs would demonstrate lower levels of adjustment to residential care relative to those with the middle range of trust beliefs in NHCs (quadratic trust-adjustment hypothesis).

(3) The quadratic relations would be found for satisfaction with care providers uniquely because it was a marker for the feelings of betrayal and disappointment by older adults who hold very high beliefs in NHCs (betrayal and disappointment hypothesis).

Some methodological and statistical issues

Different judgement formats were used in the different measurement scales. The measure of trust beliefs in NHCs required older adults to report their expectations of the trustworthiness of NHCs for very concrete activities. The measures of adjustment to residential care (e.g. satisfaction with care-giving and loneliness) required older adults to make relatively abstract and general judgements. The different formats were designed to minimise the role that common judgement biases played in associations between the two sets of measures (see Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003).

The study was guided by the premise that older adults’ trust beliefs in NHCs are a potential cause of adjustment to residential care as shown by linear and quadratic relations. The study included tests for the reverse quadratic relation to examine the reverse direction of potential causation. This strategy was guided by the principle that a quadratic relation between variable X (a predictor) and variable Y (the dependent measure) is not statistically equivalent to the reverse quadratic relation (i.e. Y is the predictor and X is the dependent measure) (see Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken2003). Finding quadratic relations between trust beliefs in NHCs and adjustment to residential care, rather than the reverse, would yield evidence in support of the hypothesised direction of causality

Method

Participants

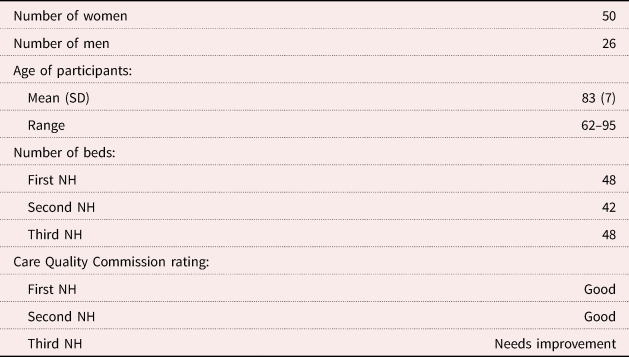

The participants were 76 older adults with the demographics shown in Table 1. Older adults with records of very severe illnesses (e.g. Alzheimer's) or mental deficits according to nursing home records were excluded from participating in the study. Participants participated if their native language was English and they had sufficient hearing capacity to hear the questions (items) posed. The participants were drawn from three nursing homes (see Table 1). The ratings and size of the nursing homes are typical of nursing homes in the UK (see Q CareQuality Commission, 2021). Approximately 65 per cent of the residents in each nursing home participated in the research. Only a few residents (i.e. 5%) declined to take part in the study.

Table 1. Participant demographics and nursing home (NH) details

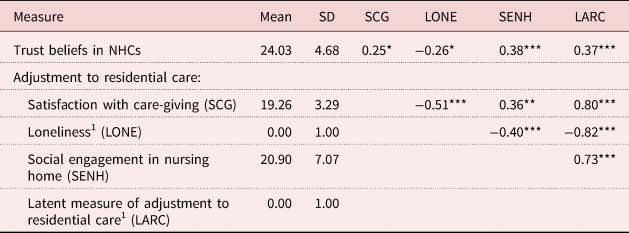

Table 2. Correlations between the measures

Notes: Degrees of freedom = 74. 1:Standardised scores. NHCs: nursing home carers.

Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Participation in the research was secured by consent from: (a) the nursing home, (b) the individual's next of kin, and (c) the individual himself or herself. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the appropriate ethics committee of Keele University. The study adhered to American Psychological Association and British Psychological Society ethics guidelines.

Measures

Trust beliefs in NHCs

This was assessed by eight items from the Trust in Specific Person scale developed by Johnson-George and Swap (Reference Johnson-George and Swap1982) that assessed reliability trust beliefs (four items) and emotional trust beliefs (three items). Those items were those found to be common to males and females. One additional reliability item identified by Johnson-George and Swap (Reference Johnson-George and Swap1982) for trust beliefs by females was included in the current study in order to achieve more balanced scales. The items were considered by the administrative staff of the nursing homes to be suitable for testing older adults.

Johnson-George and Swap (Reference Johnson-George and Swap1982) found evidence for the reliability of the reliability trust beliefs subscale (four items) and emotional trust beliefs subscale (three items) with α values > 0.71. As evidence of validity, the reliability trust beliefs items and emotional trust beliefs items had substantial loadings on their respective factors in the factor analysis. Evidence for the criterion validity of the two subscales was found in two studies. In one study, the participants held lower reliability, but not lower emotional, trust beliefs in a partner who had not shown up to an experimental session as promised as compared to a control condition. In the second study, participants held lower emotional, but not reliability, trust beliefs in a therapist who was described as being low rather than high in emotional trustworthiness.

Variations of the Trust in Specific Person scale (Johnson-George and Swap, Reference Johnson-George and Swap1982) have been used in other studies. Rotenberg et al. (Reference Rotenberg, Addis, Betts, Fox, Hobson, Rennison, Trueman and Boulton2010) used ten-item versions of reliability trust beliefs and emotional trust beliefs (which included the seven common items) to test undergraduates across a six-month period. It was found that a total scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, α values > 0.71, and stability across time (r = 0.50, p < 0.001). Factor analysis carried out by Sook-Jeong (Reference Sook-Jeong2007) on a Korean version of the Trust in Specific Person scale yielded evidence for reliability and emotional trust belief subscales. Inspection of the factor analysis indicates that seven gender-common items had factor loadings on their respective reliability and emotional trust factors.

The items from the Trust in Specific Person scale were used for the following three reasons. First, to our knowledge, there were no other scales that assess older adults’ trust beliefs in their NHC. The scale served that purpose. Second, the items were concrete, simple linguistically and required limited testing time. Consequently, answering the items placed minimal demands on the language ability, comprehension and attention-span of the older adults. Third, the items paralleled those used to assess older trust reliability trust beliefs as part of generalised trust belief scales (Rotenberg, Reference Rotenberg1990) and the finding that older adults expect a good nurse to fulfil their emotional trust beliefs (see Van der Elst et al., Reference Van der Elst, Dierckx de Casterle and Gastmans2012).

For each item in the scale, the participant judged his or her specific NHC (by the carer's initials) on five-point Likert scales that ranged from very unlikely (1) to very likely (5). The trust in NHCs scale was composed of four reliability trust beliefs items that assessed expectations that carers fulfilled a promise (e.g. ‘If my alarm clock was broken and I asked my carer to call me at a certain time I could count on receiving the call’ and ‘If my carer was going to give me a ride somewhere and didn't arrive on time, I guess there was a good reason for the delay’). The scale was composed of four emotional trust items that assessed expectations that the carer would refrain from emotional harm by uncritically accepting disclosures and maintaining confidentiality of them (e.g. ‘I would be able to confide in my carer and know that he/she would listen’ and ‘I would be able to confide in my carer and know that he/she would not discuss my concerns with others’). Initially, the items were summed, and averaged, to construct a reliability trust belief subscale (α = 0.83) and an emotional trust belief subscale (α = 0.76). The two subscales were substantially correlated, r(74) = 0.68, p < 0.001, and there were similar patterns of findings for each subscale. Consequently the subscales were summed, and averaged, to construct a trust beliefs in NHCs scale and that demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, α = 0.73. Larger numbers on the scale denoted greater trust beliefs in NHCs.

Social engagement in the nursing home

This construct was assessed by six items from the Social Engagement Index (ISE; Mor et al., Reference Mor, Branco, Fleishman, Hawes, Phillips, Morris and Fries1995). Two of the items were: ‘I found it easy interacting with others’ and ‘I actively seek involvement in the life of the facility’. The items were judged on five-point Likert scales ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Mor et al. (Reference Mor, Branco, Fleishman, Hawes, Phillips, Morris and Fries1995) administered the ISE to 1,848 residents from 268 homes in ten states in the United States of America. It was found that the ISE demonstrated acceptable internal consistency and validity by its association with the average time spent in activities in the nursing home and level of cognitive/physical functioning. The Social Engagement in Nursing Home scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, α = 0.80. The six items were summed to construct the Social Engagement in Nursing Home scale in which high scores denoted greater social engagement in the nursing home.

Loneliness

This was assessed by the full (20-item) revised version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell, Reference Russell1996) in one sample and by a shortened (four-item) version of that scale in another other sample. The items include ‘How often do you feel that you are “in tune” with the people around you?’ and ‘How often do you feel alone?’ Those were judged on five-point scales ranging from not at all to very frequently. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale and a short form of the scale have been found to demonstrate both construct validity and reliability (Russell, Reference Russell1996) and have been used frequently with older adults (Courtin and Knapp, Reference Courtin and Knapp2017). In the current study, the Loneliness scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency with α = 0.84 and 0.91 for the 20- and four-item scales, respectively. The scales were standardised for each subsample as z scores to yield a scale for the entire scale in which higher scores denoted greater loneliness.

Satisfaction with care-giving

This was assessed by the five-item satisfaction scale derived from the Caregiver Content for Resident Satisfaction Surveys in Nursing Homes (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Lucas, Castle, Lowe and Crystal2004). The scale was composed of two negatively worded (e.g. ‘I am rarely treated as an individual’) and three positively worded items (e.g. ‘I am always treated with respect’). Those were judged on five-point Likert scales ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The items were selected from those identified by Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Lucas, Castle, Lowe and Crystal2004) as cutting across the content of established survey instruments and from interviews with residents of nursing homes regarding their frequent satisfactions with care providers. In the current study, the Satisfaction with Care-giving scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, α = 0.65. The items were summed, and averaged, to yield a scale in which higher scores denoted greater Satisfaction with Care-giving.

Procedure

The participants were tested individually with a cross-sectional design. Individualised testing was required because the research examined each participant's trust beliefs in his or her own NHC. This method was adopted in order to avoid assessing older adults’ stereotypes of NHCs and to examine trust in specific NHCs. The participant identified the NHC who carried out his or primary caring duties as the ‘person who did the most or majority of the caring duties’. The participant identified (by initials) his or her NHC in the trust scale. Drawing upon nursing home records, it was confirmed that the NHC identified by each participant matched his or her actual NHC. The size of the sample was the product of this individualised intensive research strategy.

During the testing, the participant was informed that there were no right or wrong answers and his or her answers would be anonymous. The tester read the scale items to the participants and ensured that the items were heard by the participants’ verbal confirmation. The research spanned two years with one group of participants tested in the first year and a second group of participants tested in the second year. The same procedure was followed for both groups except that the Loneliness scale was reduced in length in testing during the second year. The scores by year were converted to z scores for use in the data analyses. Statistical comparisons (t and z comparisons) confirmed that there were no appreciable differences between the two times on the properties of the scales or associations between them.

Strategies for the analyses

First, the adjustment to residential care measures were subjected to a principal components analysis to assess the latent measure of adjustment to residential care. Second, the data were subjected to correlational analyses in order to examine the hypothesised associations between the measures. A supplemental step-wise regression tested whether there were gender differences in the associations and gender differences.

Third, the data were subjected to regression analyses in order to examine the linear and quadratic relations between trust beliefs in NHCs and the measures of adjustment to residential care (satisfaction with care-giving and latent measure of adjustment to residential care). The regression analyses were tested for quadratic relations by assessing whether the scores adjusted by the main associations conformed to a quadratic curve. The measures were centred for the regression analyses (see Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken2003). Fourth, and finally, in order to examine the issue of reverse causation, the regression analyses were repeated with the measures of adjustment to residential care as predictors of the dependent measure of trust beliefs in NHCs.

Results

Latent measure of adjustment to residential care

The principle component analyses of the three measures of adjustment with a varimax rotation yielded a common underlying factor/dimension with an eigenvalue of 1.85 that accounted for 62 per cent of the variance. Satisfaction with care-giving, loneliness and social engagement had weights on the underlying factor of 0.80, −0.82 and 0.72, respectively. The regression factor scores from the analysis served as a measure of the latent measure of adjustment to residential care.

Correlations between the measures

The correlations between the measures (with means and standard deviations) are shown in Table 2. The expected correlations between each of the four measures of adjustment to residential care (including the latent measure) were found. There were correlations between satisfaction with care-giving, social engagement in the nursing home and the latent measure of adjustment to residential care and negative correlations between those and loneliness. In support of the linear trust-adjustment hypothesis, trust beliefs in NHCs were: (a) correlated with satisfaction with care-giving, social engagement and the latent measure of adjustment to residential care, and (b) negatively correlated with loneliness. Step-wise regression analysis (main effects and then the interaction) showed that the association between trust beliefs in NHCs and social engagement in the nursing home was moderated by gender, β = 0.87, p = 0.036. The correlation between the two variables was stronger in males, r(24) = 0.76, p < 0.001, than in females, r(48) = 0.16, p = 0.26.

Testing the hypothesised quadratic relations

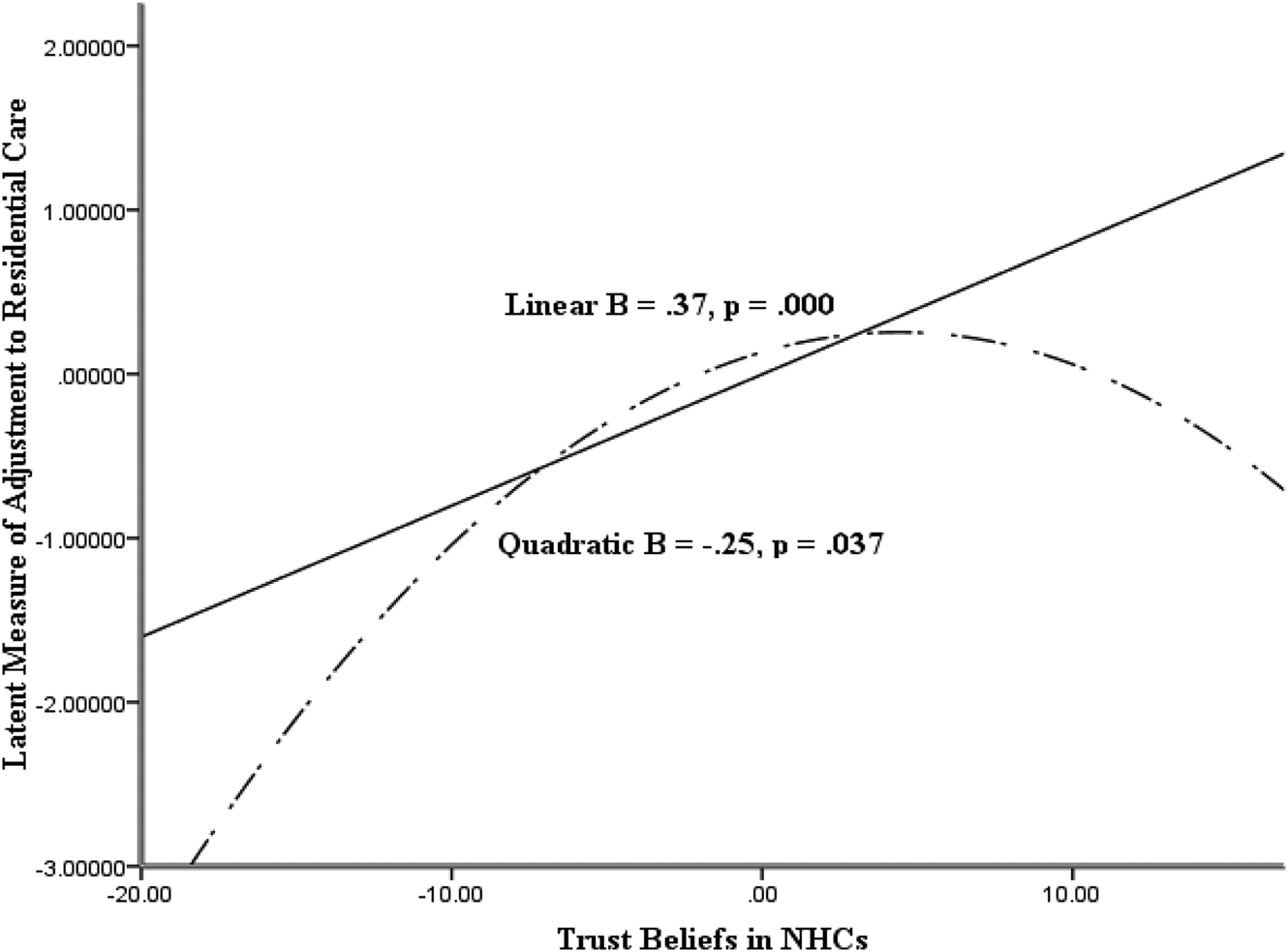

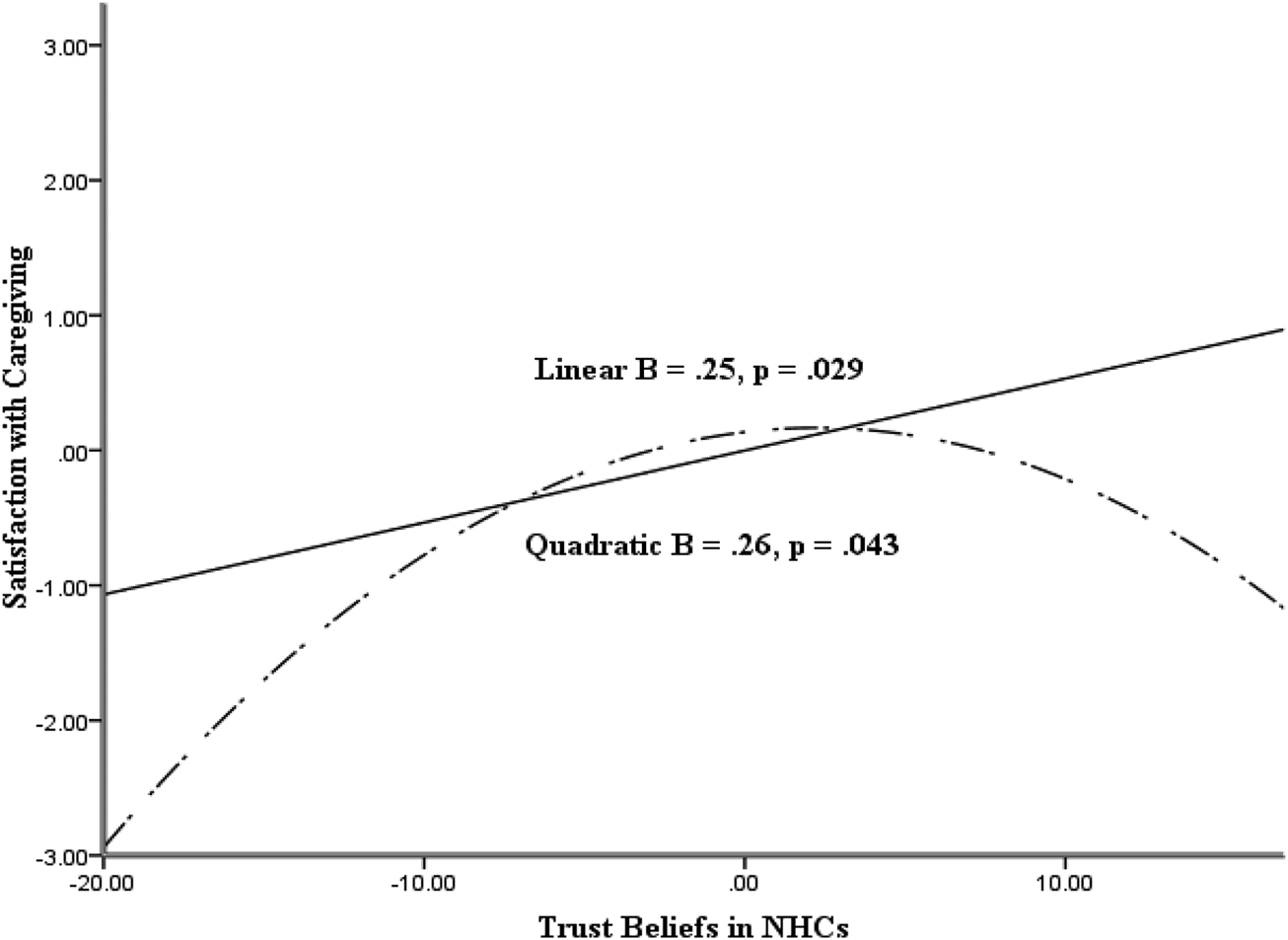

In support of the linear trust-adjustment hypothesis, the regression analyses yielded linear relations between trust beliefs in NHCs and each of the measures of adjustment to residential care: (a) latent measure of adjustment (see Figure 1), (b) satisfaction with care-giving (see Figure 2), (c) loneliness adjusted by gender (see Figure 3), and (d) social engagement (B = 0.38, p < 0.001). These correspond to the observed correlations shown in Table 1. In support of the quadratic trust-adjustment hypothesis, the regression analyses also yielded quadratic relations between trust beliefs in NHCs and: (a) latent measure of adjustment to residential care, (b) satisfaction with care-giving, and (c) loneliness adjusted by gender (at a trend level). Regarding social engagement, regression analysis yielded β = −0.13, p = 0.31, as a quadratic effect. The observed quadratic curve was similar to those found in other measures of adjustment to residential care but the effect did approach or attain statistical significance. As expected, participants with very low and those with very high trust beliefs in NHCs showed lower levels of the latent measure of adjustment to residential care, satisfaction with care-giving and loneliness relative to those with the middle range of trust beliefs in NHCs. The quadratic curves were representative of the distribution of the scores. The curves were modestly skewed, though, such that lower levels of adjustment to residential care tended to be shown by participants with very low trust beliefs relative to those with very high trust beliefs. The quadratic analyses and the observed curves are consistent with the disappointment/betrayal hypothesis because the quadratic effects were found primarily for satisfaction with care-giving. Those with very high trust beliefs in NHCs showed depressed levels of satisfaction with care-giving relative to those with the middle range of trust beliefs in NHCs.

Figure 1. Linear and quadratic relations between trust beliefs in nursing home carers (NHCs) and the latent measure of adjustment to residential care.

Figure 2. Linear and quadratic relations between trust beliefs in nursing home carers (NHCs) and satisfaction with care-giving.

Figure 3. Linear and quadratic relations between trust beliefs in nursing home carers (NHCs) and loneliness (adjusted by gender).

Testing the reverse quadratic relations

A regression analysis showed that there was a linear relation between each of the four measures of adjustment to residential care and trust beliefs in NHCs with β = 0.37, p = 0.001 (latent measure), β = 0.25, p = 0.029 (satisfaction with care-giving), β = 0.38, p = 0.001 (social engagement) and β = −0.26, p = 0.022 (loneliness). These are consistent with the observed correlations. The linear relations were not qualified, however, by quadratic relations with β = −0.04, p = 0.72 (latent measure), β = 0.03, p = 0.81 (satisfaction with care-giving), β = −0.10, p = 0.34 (social engagement) and β = −0.10, p = 0.42 (loneliness).

Discussion

The findings yielded by the current study highlight the importance of older adults’ trust beliefs in their NHCs for their adjustment to residential care. As expected, the more older adults held trust beliefs in their NHCs, then the more they were adjusted to residential care in the form of high satisfaction with nursing home care-giving, low loneliness, high social engagement with others in the nursing home and high latent measure of adjustment to residential care. These findings are consistent with the range of studies showing that trust beliefs in others are associated with psychosocial adjustment in children, adolescents and young adults (Rotenberg et al., Reference Rotenberg, Boulton and Fox2005, Reference Rotenberg, Qualter, Barrett and Henzi2014). The findings complement research that shows that older adults’ generalised trust beliefs in others are associated with their life satisfaction and physical health (e.g. Barefoot et al., Reference Barefoot, Maynard, Beckham, Brammett, Hooker and Siegler1998). The current study uniquely showed this relation, however, with respect to older adults’ trust in their NHCs and adjustment to residential care.

The association between trust beliefs in NHCs and social engagement in the nursing home was stronger in men than in women. One explanation of those gender differences is that women show a modestly greater orientation to social communion in social relationships by greater striving for intimacy, social connectedness and social solidarity (Wiggins, Reference Wiggins, Grove and Cicchetti1991; Zarbatany et al., Reference Zarbatany, Conley and Pepper2004). It may be that those tendencies become manifest in women's social relationships with other nursing home residents and thus override the influence of their trust beliefs in their NHCs on social interactions.

The observed quadratic relations are similar to the patterns found during childhood and adolescence (Rotenberg et al., Reference Rotenberg, Boulton and Fox2005, Reference Rotenberg, Betts and Moore2013, Reference Rotenberg, Qualter, Barrett and Henzi2014). As anticipated, the quadratic relation was clearly evident in satisfaction with care providers in which older adults with very high trust beliefs showed relatively depressed levels of satisfaction with their care provider. This potentially reflects the disappointment or sense of betrayal experienced by those very old adults. The quadratic relation tended to be shown for loneliness for a related reason. When older adults held low trust beliefs in NHCs then they may be unwilling to disclose to them and experienced elevated loneliness. When older adults held high emotional trust beliefs in NHCs and that level of emotionally trustworthiness was not reliably fulfilled then the older adults may be reluctant to disclose to them and experienced elevated loneliness. The lack of an appreciable quadratic relation in social engagement could have been due to other highly influential factors that affect older adults’ social engagement in a nursing home, such as the sociability of other residents or the availability of leisure activities. The findings showed that the quadratic relation was found in the latent measure which assessed the convergence of the experience of adjustment to residential care.

As expected, it was found that older adults with very low trust beliefs in NHCs showed lower levels of adjustment to residential care relative to those with a middle range of trust beliefs in NHCs. The findings are consistent with the principle that individuals with low and very low trust beliefs in others tend to be socially disengaged from others, isolated and lonely (see Rotenberg et al., Reference Rotenberg, Boulton and Fox2005). The observed quadratic curve was modestly skewed in the current study, which supports the conclusion that it was more detrimental to adjustment to residential care if the older adults held very low than very high levels of trust beliefs in NHCs.

The findings yielded by the current study broadly lend support for the usefulness of the BDT (Rotenberg, Reference Rotenberg and Rotenberg2010) as a way of conceptualising the trust beliefs by older adults and examining its correlates. In the current study, the BDT-derived measures served as useful way to assess older adults’ trust beliefs in a specific category of persons (i.e. NHCs) and implications of those beliefs for adjustment in a given setting (i.e. nursing homes).

The current findings are cross-sectional and therefore there are limitations in inferences that can be drawn about the causal relations between the variables. In response to these issues, the trust beliefs in NHCs measure was anchored in the older adults’ expectations of concrete behaviours and regression analyses confirmed that there were no appreciable quadratic relations between the measures of adjustment to residential care and the older adults’ trust beliefs in NHCs. Longitudinal designs are required, though, to test whether older adults’ trust beliefs in NHCs are a probable cause of their adjustment to residential care. There are several problems that would be encountered in a longitudinal investigation. There are high turnover rates of NHCs (Costello et al., Reference Costello, Cooper, Marston and Livingston2020) and the limited lifespan of older adults (i.e. over 80 years). Problems would arise because of considerable variations across residents in the timing and duration of the social contact between them and their NHC.

The current study was limited to psychosocial measures of the residents. Future lines of research could include examining the extent to which trust beliefs in NHCs by older adults predicts their physical health and longevity (see Barefoot et al., Reference Barefoot, Maynard, Beckham, Brammett, Hooker and Siegler1998). In that vein, it would be worthwhile to examine the extent to which older adults’ health and cognitive functioning affected the relation between their trust beliefs in NHCs and adjustment to residential care. For example, older adults with Alzheimer's require specific forms of care and the NHCs’ trustworthy provision of that care could affect both the older adults’ trust beliefs in their NHC and adjustment to residential care. It would be worthwhile for researchers to investigate whether there is cross-cultural constancy in the relations observed in the current study. The current study added to evidence regarding the effectiveness of processes of care to affect older adults’ psychosocial adjustment. The findings may be regarded as one aspect of the quality of nursing homes that include organisational characteristics and other structures of care.

Researchers have found that some interventions (animal-assisted therapy, mindfulness-stress training and new technologies) are effective in reducing loneliness and isolation in older adults (see Hagan et al., Reference Hagan, Manktelow, Taylor and Mallett2014; Brimelow and Wollin, Reference Brimelow and Wollin2017). There have been interventions designed to increase the processes of care such as assistance with daily activities, involvement of informal care-givers and activity programmes (Sloane et al., Reference Sloane, Hoeffer, Mitchell, McKenzie, Barrick, Rader, Stewart, Talerico, Rasin, Zink and Koch2004; Fritsch et al., Reference Fritsch, Kwak, Grant, Lang, Montgomery and Basting2009). Researchers might consider implementing an intervention that trains NHCs to increase and sustain their reliability and emotional trustworthiness in interactions with the older adult residents. It would include training NHCs to be acceptant of the residents’ disclosure of emotional states/cognitions (e.g. health needs and reminiscing). There would be various other consequences of that intervention. It could increase the likelihood that older adults would receive psychological and medical treatment by permitting NHCs to convey relevant information to clinical psychological and medical professionals (see Corbett and Williams, Reference Corbett and Williams2014). The intervention could promote adaptive reminiscing by older adults as part of dyadic relationships with care providers (Ingersoll-Dayton et al., Reference Ingersoll-Dayton, Kropf, Campbell and Parker2019). The recommended intervention would assist those residents with very low trust beliefs, as well as those with very high trust beliefs, in their NHCs. Broadly, the intervention could help the nursing homes to achieve the quality of care needed to serve the growing population of older adults.

Ethical standards

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the appropriate ethics committee of Keele University. The study adhered to American Psychological Association ethics and British Psychological Society ethics guidelines.