1 Introduction

When speakers produce discourse, they exchange information that is organised in a sequence of temporally ordered units. They structure the information within and across these units in such a way that the common ground shared between speaker and hearer is constantly updated. This is referred to as information structure (Halliday Reference Halliday1967a) or information packaging (Chafe Reference Chafe1974). In English, intonation is used as a major resource to structure information in real time (Halliday Reference Halliday1967a; Crystal Reference Crystal1969; Tench Reference Tench1996; O'Grady Reference O'Grady2013). Speakers can also rearrange information in English either by modifying the linear order of syntactic elements or by shifting the alignment between semantic elements and syntactic functions through the use of information-packaging constructions. In this article, we focus on one such construction, the specificational it-cleft, e.g. (1), which is traditionally viewed as repackaging the information structure of the corresponding non-cleft sentence, (2), through a combination of syntactic, information structural and prosodic features.Footnote 2

(1) It's their credibility that's in question. (LLC–1)Footnote 3

(2) Their credibility is in question.

Regarding the syntax of it-clefts, we adhere to the ‘non-derivational’ structural analysis argued for in Davidse (Reference Davidse2000), Lambrecht (Reference Lambrecht2001) and Huddleston & Pullum et al. (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002). It-clefts consist of a matrix and a relative clause. The ‘cleft relative clause … is not syntactically part of the subject [it]’ and ‘does not form a constituent with its antecedent’ (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 1416; see also Reeve Reference Reeve2011). The antecedent of the cleft relative clause is the full complement NP, which refers to a fully determined instance, e.g. their credibility in (1), in contrast to restrictive relative clauses, whose antecedent is the nominal head, designating an entity-type (Davidse Reference Davidse2000: 111; Lambrecht Reference Lambrecht2001: 473). It-clefts are specificational constructions because the complement of the matrix specifies a value, their credibility, for a variable, i.e. the gap in the proposition expressed by the relative clause, ‘x that's in question’. It is generally accepted that this syntax highlights the value vis-à-vis the presupposed open proposition in the cleft relative clause.

The matrix of it-clefts is a specificational identifying clause (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 1416–17), which construes its complement as an identifier (Halliday Reference Halliday1967a: 224; Davidse Reference Davidse2000: 1120). That is, the matrix complement is equated with the ‘x’-element of the cleft relative clause. The identifying syntax of the matrix triggers the conversational implicature that its complement exhaustively specifies the value for the variable (see Declerck Reference Declerck1988). For instance, in (1) ‘the x that's in question’ is just their credibility.

The literature on clefts has focused strongly on the relation with their ‘declefted’ counterpart, (2), even claiming it to be a recognition test for clefts, although it is not always available (see also Karssenberg Reference Karssenberg2018: 22).Footnote 4 As we will argue in this article, the closest counterpart of clefts in terms of shared syntactic, semantic and pragmatic features given is formed by monoclausal specificational clauses, as in (3), which have been referred to as reduced clefts (Declerck Reference Declerck1983; Declerck & Seki Reference Declerck and Seki1990) or truncated clefts (Hedberg Reference Hedberg2000; Huddleston & Pullum Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002 et al.; Collins Reference Collins2006; Mikkelsen Reference Mikkelsen, Geist and Rothstein2007).

(3) cos all sorts of things go into port don't they I mean it's not just wine [that goes into port] (LLC–1)

As in full clefts, the complement of reduced clefts specifies the value corresponding to the semantic gap in a presupposed open proposition, which, however, is not overtly expressed but has to be inferred from the preceding text, as shown within square brackets in (3). While we will continue to use the entrenched term ‘reduced clefts’, we stress that they are constructions in their own right, offering language users the option of a monoclausal specificational structure besides the bi-clausal full cleft structure.

The literature on the information structure of it-clefts has been strongly influenced by both the formal–pragmatic approach inspired largely by Lambrecht (Reference Lambrecht1994, Reference Lambrecht2001) and the functional approach instigated by Halliday (Reference Halliday1967a, Reference Halliday1967b) and Halliday & Greaves (Reference Halliday and Greaves2008). Theoretically, these two approaches differ greatly but this may not be immediately obvious because focus, prosody and discourse-familiarity figure in both. Lambrecht (Reference Lambrecht2001: 474) conceives of information structure as the pragmatic structuring of propositions, whereby the pragmatic assertion differs from the presupposition in terms of the focus. The focus is typically accented, but this is not part of its definition. In the Hallidayan tradition, by contrast, information units and information foci are intrinsically coded by prosody in English spoken discourse (Halliday Reference Halliday1967a: 200). Speakers are viewed as having considerable freedom to mark off information units whose internal structure always features focal information, typically related to non-focal information.

In descriptive practice, studies from both traditions make claims about accented foci in it-clefts, which as such can be assessed empirically. Many studies hold that the value-constituent either carries the only information focus coded by a nuclear accent (Clark & Haviland Reference Clark, Haviland and Freedle1977; Givón Reference Givón2001; Lambrecht Reference Lambrecht2001), or carries the main information focus marked by the relatively most prominent accent of multiple nuclei (Prince Reference Prince1978; Declerck Reference Declerck1984; Patten Reference Patten2012). Other studies have challenged this systematic mapping by showing that some values do not have information focus (Halliday Reference Halliday1967a; Delin Reference Delin1990; Collins Reference Collins1991, Reference Collins2006; Kimps Reference Kimps2016).

This article is situated in the Hallidayan tradition, within which it is, to the best of our knowledge, the first large-scale study of full and reduced it-clefts in sound file data whose prosody has been analysed with a mix of auditory and instrumental analysis. The structure of this article is as follows. In section 2, we set out the functional approach to information structure that we follow vis-à-vis the formal–pragmatic approach, first in general (sections 2.1 and 2.2) and then as applied in studies of it-clefts (section 2.3). The bulk of the article is devoted to a corpus study. We typified and quantified the distribution of discourse-given and discourse-new information and of prosodic foci over the syntactic constituents of value and variable. Section 3 details our data and methodology. In section 4, we summarise our main results, comparing full clefts with reduced clefts. We further interpret these results in section 5. We show not only that it is untenable to claim that the value of it-clefts is always accented as the most salient new information, but we also argue that clefts highlight information by means of two strategies, (i) syntactic and (ii) prosodic, and involve speakers manipulating grammar, prosody, linearity and context to manage information flow in real time.

2 Analytical framework

In this section, we set out the functional approach to information structure that we follow vis-à-vis the functional (section 2.1) and formal–pragmatic approaches (section 2.2) first in general and then as applied in studies of it-clefts (section 2.3).

2.1 The relation between focus and discourse-familiarity: the functional approach

In the Hallidayan (Reference Halliday1967a, Reference Halliday1967b, Reference Halliday1994; see also Halliday & Greaves Reference Halliday and Greaves2008) functional tradition, intonation is viewed as the main coding means by which English speakers structure information into focal and non-focal information (Tench Reference Tench1996; O'Grady Reference O'Grady2013). English speech progresses as a succession of melodic units, which, according to Halliday (Reference Halliday1967a: 202) ‘represents the speaker's blocking out of the message into quanta of information, or message blocks’. That is, each tone unit realises an information unit (Halliday Reference Halliday1967b), or what Cruttenden (Reference Cruttenden1997) calls a ‘presentation unit’. Information units correspond to a clause in only a small majority of cases (O'Grady Reference O'Grady, Bowcher and Smith2014b), being smaller or larger than a clause in the remaining percentage. Information focus is coded by the placement of the nuclear accent on a specific syllable of the tone unit, which ‘carries the main pitch movement’ (Halliday Reference Halliday1994: 296), i.e. the tonic syllable. The domain of the information focus is typically not just the tonic syllable as such but the larger constituent it is part of (Halliday Reference Halliday1967a: 204). Semantically, information focus is what the speaker presents as the most salient new information the hearer has to attend to. Information is generated by the speaker from the tension between what s/he presents as recoverable, i.e. given, and non-recoverable, i.e. new (Halliday Reference Halliday1994: 296–9). Halliday (Reference Halliday1967a: 203–9; Reference Halliday1994: 295–9) distinguishes two types of information focus. A marked focus relates to presupposed information, which may precede and/or follow the focus. This focus is ‘informationally contrastive … either within a closed system or lexically’ (Halliday Reference Halliday1967a: 207). An unmarked focus does not mark any information as presupposed. It always falls on the last lexical constituent of the information unit, which it marks as the most salient new, without specifying the information status of the remainder, which, at the beginning of discourse may be wholly new. These two types are exemplified in example (4), in which the saleslady of a silver department is prepping a new job student, Anne. The different pitch movements on the nuclei are indicated as falling (\) or rising (/) or a combination of both, and the tone unit boundaries are marked by double slashes. In the first information unit, which consists of a prepositional phrase only, th\/is has a marked, non-final, information focus. Contrastive th\/is points exophorically to the context of situation and ‘signal[s] the taken-for-grantedness that Anne is there to do a job’ (Halliday Reference Halliday1994: 369). The second information unit presents information as corresponding simply to an implied question like ‘what is happening?’ (Halliday Reference Halliday1967a: 208), and introduces s\ilver as an unmarked final focus.

(4) // ^in th\/is job Anne we're // working with s\ilver // (Halliday Reference Halliday1994: 368)

As illustrated in (4), what the elements of the information unit present as focal, presupposed, etc. shows some, but by no means complete or straightforward, correlation with what is actually given or new in the discourse. Halliday (Reference Halliday1994: 301) stresses that speakers, within given discursive conditions, may ‘play with the system … to produce an astonishing variety of rhetorical effects’.

To investigate how speakers manipulate actual discourse-familiarity in their moment-by-moment selection of the foci they want the hearer to attend to, we will work with Kaltenböck's (Reference Kaltenböck2005) model of discourse-familiarity. Kaltenböck revises Prince's cognitively oriented (Reference Prince and Cole1981) new–given taxonomy of NP referents into a strictly text-based model of discourse-familiarity applicable to the referents of both NPs and clauses.Footnote 5 The different categories are visualised in figure 1.

Figure 1. Model of discourse-familiarity based on Kaltenböck (Reference Kaltenböck2005: 127)

In this model, referents are discourse-given when they are present in the co-text or the extralinguistic context, while a referent is discourse-new when it cannot be retrieved from the prior discourse. Referents are classified as given if they are either (i) evoked, i.e. present as such in the text or situation, or (ii) inferable, which encompasses all the referents of NPs or clauses linked to other linguistic entities through inferential bridges like whole–part relations, or event-frames ‘composed of a network of related actions’ (Du Bois Reference Du Bois and Chafe1980: 246). Referents are classified as discourse-new when they are (iii) new-anchored, i.e. introduce a new referent into the discourse but one which can only be interpreted via some link to the preceding text (Gentens Reference Gentens2016: 20–1), or (iv) brand new, i.e. interpretable wholly out-of-context.

The categories of discourse givenness and newness are often applied retrospectively. For instance, for anaphora resolution the analyst has to trace the direct or indirect antecedent. By contrast, we want to assess how given/predictable from the context or how new/unpredictable discourse-referents are. This is in accordance with the forward-moving directionality of the information flow of speech pointed out by Sinclair (Reference Sinclair, Davies and Ravelli1992) and Emmott (Reference Emmott1997). The distinction retrospective–prospective is particularly important for the dividing line between inferable and anchored-new referents. For instance, in (5), a retrospective analysis would probably lead us to treat the open proposition x have revolted against the conception of the eleven plus as inferable from the mention that grammar schools were abolished. However, looked at prospectively, the abolition of the grammar school does not as such imply that it was motivated by a revolt of any kind. We therefore analyse the proposition as new-anchored.

(5) finally there is something which I ought to allude to […] and that is the effect of changes in the curriculum the ways of teaching in the schools this is not anything to do necessarily with comprehensive schools or the abolition of the grammar school it is notable that in this country it is the middle classes thems\elves# who have revolted ag\ainst# the conception of the eleven pl\us# (LLC–1)

Our approach to information structure takes the Hallidayan model further in two ways. Firstly, the rather static model according to which information structure is ‘mapped onto’ transitivity and mood structure is replaced by the more dynamic model of speakers balancing grammatical and prosodic choices moment by moment in real time (O'Grady Reference O'Grady2010; O'Grady & Bartlett Reference O'Grady and Bartlett2019). The choices are shaped both by the nature and extent of information shared between speaker and hearer and by their awareness of communicative purposes. Utterances are produced in real time as part of a textual chain, which moves the discourse forward while simultaneously grounding the discourse in the shared context.

Secondly, the investigation of information management is extended beyond the sentence to larger discursive (dialogic) contexts. Initial and final positions of intonational units are especially important as they signal relations with the previous unit and anticipate hearer response to the upcoming update of the common ground (O'Grady Reference O'Grady2010, Reference O'Grady2014a). Onsets in particular have been shown to serve as an interactional device to signal how the upcoming material relates to the previously generated expectations (O'Grady Reference O'Grady2013, Reference O'Grady2014a). The onset is the ‘first prominent syllable in a tone unit’ (O'Grady Reference O'Grady2014a: 691), which indicates the ‘key’, i.e. the pitch level at which the current utterance starts. Brazil (Reference Brazil1997) classified key choices as high, mid or low relative to the height of the previous onset, which may be part of discourse by the same or by the previous speaker. A high onset indicates a change or disruption in the discourse such as the introduction of a new topic or disagreement, while a low onset signals support of the previously generated expectations. A mid onset is the unmarked option and projects that the upcoming unit is not contrary to expectations.

Studying a construction like it-clefts with this broader view of information management allows us to link their internal information structure to their larger discursive-interactional context.

2.2 The relation between focus and discourse-familiarity: the formal–pragmatic approach

For Lambrecht (Reference Lambrecht1994: 5), information structure is concerned with how propositions as conceptual representations of states of affairs are paired with lexicogrammatical structures that interlocutors can interpret as pragmatic units. Focus is defined as the unit by which the pragmatic assertion differs from an utterance's presuppositions (Lambrecht Reference Lambrecht2001: 474). The presuppositions are the set of propositions lexicogrammatically evoked by a sentence which the speaker assumes the hearer already knows or is ready to take for granted, ‘which is more or less equivalent to the notion “hearer-old” in the system of Prince (Reference Prince, Mann and Thompson1992)’ (Lambrecht Reference Lambrecht2001: 474). The assertion is the proposition the speaker expects the hearer to know or take for granted as a result of hearing the utterance, i.e. the ‘new information’. The focus is the denotatum that makes the utterance into an assertion and is ‘by definition an unpredictable part of the proposition’, which explains why, with a few motivated exceptions, the focus constituent ‘necessarily requires an accent’ (Lambrecht Reference Lambrecht2001: 479).

Summing up, the pragmatic approach to information structure differs from the functional one in that it

(i) takes the pragmatically structured proposition, rather than the prosodically coded information unit, as basic unit,

(ii) treats accent as a possible corollary, not the intrinsic realisation, of focus, and

(iii) correlates components, like presuppositions, more or less straightforwardly with discourse-old and discourse-new information in the cognitively oriented sense of Prince (Reference Prince, Mann and Thompson1992).

2.3 Focus and discourse-familiarity in clefts

On Lambrecht's (Reference Lambrecht2001) analysis, it-clefts assert a simple proposition, which their bi-clausal syntax constructs into pragmatic components. The postverbal NP in the matrix is the focus, i.e. the element by which the assertion differs from the presupposition expressed by the cleft relative clause. Indeed, according to Lambrecht (Reference Lambrecht2001), the syntax of clefts is dedicated to coding these pragmatic functions. It + be in the matrix is a focus marker which unambiguously codes the ‘predicative argument of the copula’ (Lambrecht Reference Lambrecht2001: 467) as an argument-focus, e.g. champagne in (6a), whose predication is coded by the cleft relative clause, I like x. By contrast, the non-cleft counterpart (6b) is pragmatically ambiguous between having argument focus, which answers an implied wh-question, or sentence focus, which answers a question like ‘what is the case?’ (Lambrecht Reference Lambrecht1994: 221–3). While for Lambrecht the focus-presupposition articulation is coded by the syntax of clefts, he (Reference Lambrecht2001: 478–93) nevertheless makes descriptive claims about the pitch accents carried by them: the focus phrase is ‘necessarily accented’ (Reference Lambrecht2001: 493) and the presupposition typically ‘unaccented’ (Reference Lambrecht2001: 479), unless it adds something to the presupposed current concern that was not ‘sufficiently salient in the discourse’ (Reference Lambrecht2001: 480), e.g. I crave in (6c). In such a case, there may be a pitch accent on an element of the cleft relative clause, which, because of that unit's inherent presupposed status, is analysed as a topic accent (not a focus accent) (Reference Lambrecht2001: 480).

-

(6)

(a) It is CHAMPAGNE that I like. (Lambrecht Reference Lambrecht2001: 469)

(b) I like CHAMPAGNE. (ibid.)

(c) It is CHAMPAGNE that I CRAVE.

The pattern that Lambrecht posits as being the most prototypical and frequent one for the it-cleft construction is the one illustrated in (6a).

Unlike Lambrecht (Reference Lambrecht2001), we do not view clefts as merely coding the structural organisation of pragmatic information of a simple proposition, with its matrix it + be not contributing any propositional meaning. Rather, as stated in section 1, we hold that the matrix codes specificational identifying semantics, construing its identifier as the value for the variable described by the relative clause, and triggering an exhaustiveness implicature. The de-coupling and cross-coupling of prosody and lexicogrammar proposed in section 2.1 allow us to do justice to the many different information structures with a great variety of focus assignments actually attested in usage (see section 4). As pointed out early in Halliday (Reference Halliday1967a: 236–7; Reference Halliday1968: 179), the value-constituent can be focal or non-focal, and the cleft relative clause can feature no, one or multiple foci. Halliday's views on the possibility of multiple information-structural patterns in it-clefts are in line with the many accounts recognising the occurrence of multiple foci in clefts (Declerck Reference Declerck1984; Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 1384–5; Geluykens Reference Geluykens1988; Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 1424–5). It is also supported by empirical data presented by Delin (Reference Delin1990), Collins (Reference Collins1991, Reference Collins2006) and Kimps (Reference Kimps2016), of which only the last includes an in-depth instrumental and auditory analysis of the prosody of a restricted number of sound files. With this more extended study of sound data, we investigate how speakers manipulate the actual discourse-givenness of the syntactic constituents of full and reduced clefts in their selection of foci and how they relate the clefts to the surrounding discourse.

3 Data and methodology

The dataset we used for this study was extracted from the complete 100 texts of the first London–Lund Corpus of Spoken English (LLC–1), which comprises monologues and conversations in British EnglishFootnote 6 (Svartvik & Quirk Reference Svartvik and Quirk1980; Svartvik Reference Svartvik1990). Occurrences of full and reduced it-clefts were retrieved by searching for the sequence it + form of be and manually sorting all the hits. This very general query ensured netting full clefts with zero relative marker [ø], e.g. I thought perhaps it was the - the sopr/\ano had got drowned (LLC–1), as well as reduced clefts. As recognition criteria we used, amongst others, non-referentiality of it and presence of (part of) the variable in prior discourse.Footnote 7 We excluded instances of different constructions realised by superficially similar syntagms such as copular sentences with referential it and copular sentences with a restrictive relative clause. An overview of the dataset obtained is given in table 1.

Table 1. Overview of the LLC–1 dataset

Our research questions hinge on how speakers manipulate the discourse-familiarity of the syntactic constituents when they make their moment-by-moment choices to manage the information flow. The relevant prosodic features we analysed are tones, tone units, nuclear accents and onsets (see section 2.1 for definitions).

To typify and quantify these features in all tokens of the dataset, the first and second authors carried out an inter-rater auditory and instrumental analysis, visualising the sound wave of each cleft with the assistance of Praat (Boersma Reference Boersma2001). They then compared their analyses with the original prosodic transcriptions of LLC–1 and made changes of three types.Footnote 8 They corrected the analysis of the tones in a number of cases and they also implemented two systematic changes regarding compound tones and subordinate tone units, which are part of the original LLC–1 transcriptions. Compound tones were defined by Halliday (Reference Halliday1967b) as the fusion of two tones, yielding two nuclear syllables within a single tone unit. The existence of compound tones was rejected by Tench (Reference Tench1996) and O'Grady (Reference O'Grady, Bartlett and O'Grady2017) on two criteria. Firstly, Tench (Reference Tench1990) shows contra Halliday (Reference Halliday1967b) that a pre-tonic segment can in fact be inserted before the second tonic, which justifies adding a tone unit boundary breaking the compound tone into two. Secondly, Tench (Reference Tench1990: 51) and O'Grady (Reference O'Grady, Bartlett and O'Grady2017) point out the incompatibility between Halliday's (Reference Halliday1967b) postulate that one tone unit always codes one information unit and the very existence of compound tones. Example (7b) illustrates our changes to the original transcription (7a) for the two issues just discussed.Footnote 9 The final tone is falling rather than rising, as shown by the Praat image in figure 2, and the compound tone is reanalysed into a sequence of two distinct tones.

-

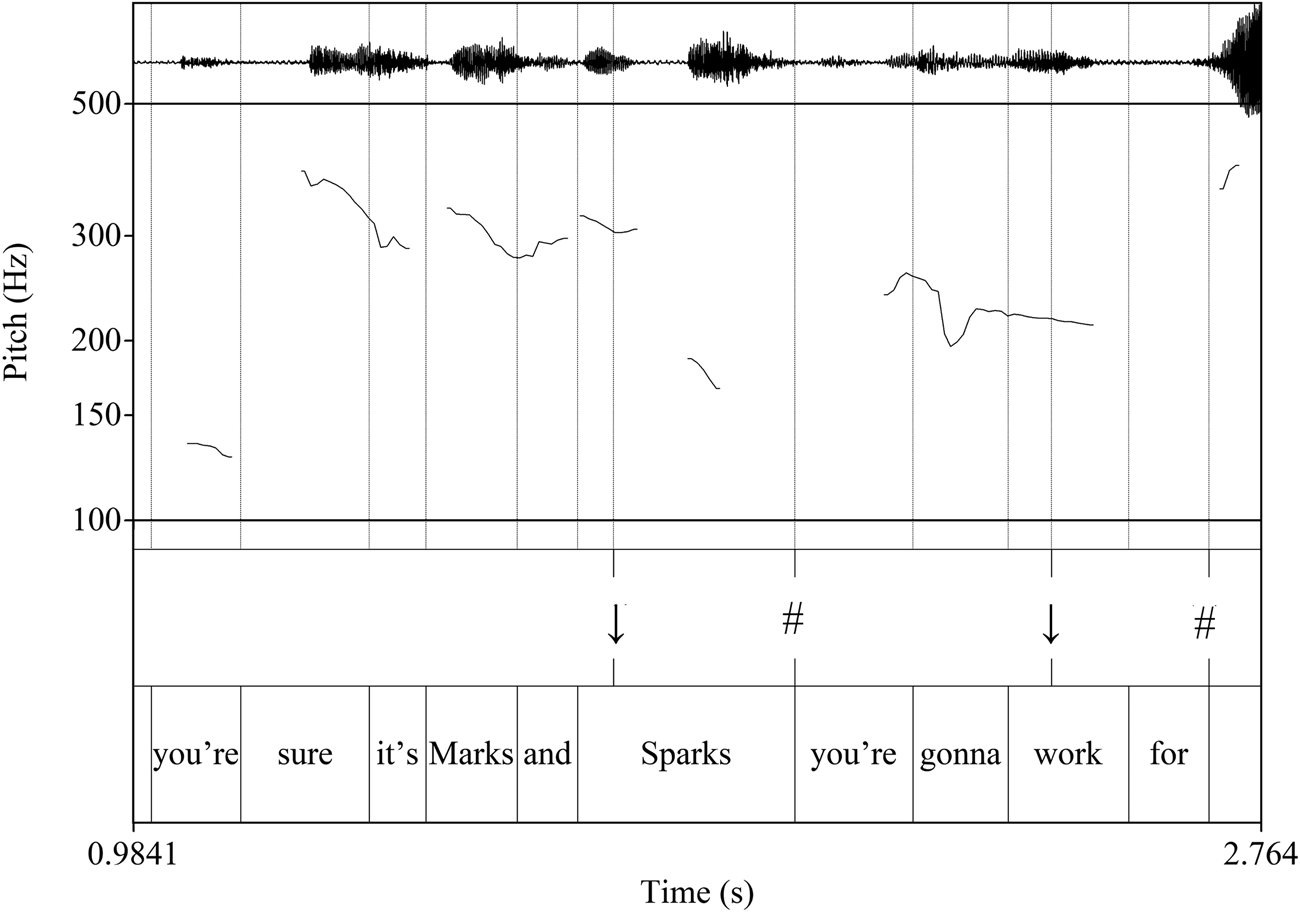

(7)

(a) he said you're ^sure it's Marks and Sp\arks you're going to w/ork for#

(b) he said you're ^sure it's Marks and Sp\arks# you're going to w\ork for#

Subordinate tone units, indicated by braces in the LLC–1 transcription as in (8a), were also eliminated in view of the flat nature of phonological patterning, which prohibits any kind of recursion (O'Grady Reference O'Grady2013). They were replaced by full-fledged tone units, as shown in (8b).

-

(8)

(a) n\o# it's the \Union# - - ^as dist\/inct from SRC {that runs th/at#}#

(b) n\o# it's the \Union# - - L^as distM\/inct from SRC# that runs thM/at#

Figure 2. Praat image of example (7)

Finally, we analysed the onsets, i.e. the first accented syllable of the intonation unit, which may be a pitch accent preceding the nuclear accent, e.g. as in (8), whose onset status is symbolised by ^, or the nuclear accent itself if it comes first or is the only accent in the tone unit. Onsets are analysed in terms of three degrees of relative pitch height, high, mid and low, indicated by small capitals h, m and l immediately prior to the onset. Relying on instrumental analysis of the pitch curve, we assessed the pitch height of each onset relative to that of the nucleus within the same tone unit. The typical threshold we assumed for significant step-ups, i.e. movements from one plateau to another, was 0.05 logHertz or more.

On the basis of this analysis, we typified and quantified the prosodic patterns realising information management in the it-clefts. The first question we addressed is the one that has been central to the various typologies of clefts as information packaging constructions proposed in the literature: which constituents of clefts carry prosodically marked information foci? We categorised each pattern in terms of the focal-non-focal status of the value and of the cleft relative clause if expressed, and the copula be. The status of the copula was only included in the list of patterns if it was focal.

The second issue we investigated was whether the foci differ in terms of degrees of prominence if a cleft has more than one focus. This operationalises the hypothesis that the focus on the value is realised by a ‘stronger’ accent than foci on other parts of the cleft (e.g. Prince Reference Prince1978; Declerck Reference Declerck1984). Relying on instrumental analysis of the pitch curve, we examined the question of different degrees of prominence of nuclei with reference to Esser's (Reference Esser1988) hierarchy of foci. We posited a hierarchy based on the combination of two parameters: pitch height of the nucleus and tone movement. To determine the pitch height of nuclei, we queried its articulatory correlate, F0. This allowed us to distinguish three levels, high, mid and low, for each type of tone movement. Tone movements were then ranked in the following order: high fall > mid fall > low fall > high rise > mid rise > low rise (Esser Reference Esser1988; Van Praet Reference Van Praet2019). Rise–fall and fall–rise are included under the fall and rise categories respectively. For values and/or variables realised with multiple tone units, we considered only the highest-ranked tone movement. Thus, when both value and variable have a final falling tone, the value is considered higher if the pitch height of the information focus and the fall are higher and vice versa. The value is also labelled as higher in the hierarchy when the value has a final falling tone and the variable a rising tone. By contrast, if the value has a final rising tone and the variable a falling tone, the value is categorised as being lower in the hierarchy. The value and variable are treated as being at the same level in the hierarchy when they have the same final tones and the difference in pitch height is not auditorily perceptible. If step ups were noted in the auditory analysis, they were typically no less than 0.05 logHertz.

The final dimension we analysed is the actual discourse-familiarity, which, as noted in section 2, is viewed as impacting on, as well as being manipulated by, speakers in their choice of which information to make focal and which non-focal. We used Kaltenböck's (Reference Kaltenböck2005) taxonomy (see section 2.1) to classify clefts according to the distribution of given or new information over value and variable. For our analysis of the prior context, we set a maximum of 20 previous turns.Footnote 10

4 Results

In this section, we present the main quantitative results of our study of prosodic features and discourse-familiarity channelling the flow of information in clefts.

4.1 Prosodic characteristics of clefts

First, we present our findings about the location of prosodically coded foci on syntactic constituents in table 2. A principled distinction is made between the patterns attested in full and reduced clefts, as they offer a different syntactic environment for prosodic choices.

Table 2. Distribution of prosodic patterns of it-clefts

In total, four prosodic patterns can be identified for full clefts and three for reduced clefts. To classify a value or variable as focal, we made no distinction in table 2 between realisation by a single or by multiple tone units. The results show that full clefts typically exhibit a focal–focal pattern (63.6%), as in (9), in which both the value and the variable contain one or more nuclei. The opposite pattern, i.e. non-focal value and focal variable, e.g. (10), is found in 23.8% of occurrences. The same pattern with added focus on the copula, e.g. (11), is found in 4.2% of occurrences only. The focal–non-focal pattern, illustrated in (12), which Lambrecht (Reference Lambrecht2001) posits as the prototypical one, is found in only 8.4% of tokens, showing that it can hardly be described as the typical prosody of it-clefts.

(9) it's H^how much they mM\ove it# that cM\ounts# (LLC–1)

(10) H^for it is the terms that really mM\atter# (LLC–1)

(11) I'm H^trying to remember where it wM\as# that I hM\eard# that you were H^likely to get sM\upport# (LLC–1)

(12) it's the grM\/ammar which is interesting# (LLC–1)

By contrast, reduced clefts show much less variety, mainly due to the absence of the cleft relative clause, with only three patterns available. The majority (93.7%) have information focus on the value only, e.g. (13).

(13) ^when does she retL\ire# it's ^not this yL\ear# M/is it# (LLC–1)

Next, for full clefts with the focal–focal pattern, we give our findings about the relative degrees of prominence of foci on value and variable in table 3, which visualises all the attested patterns.Footnote 11

Table 3. Hierarchy of nuclei in full multiple tone unit it-clefts

In the most frequent pattern, the value is hierarchically higher than the variable, either because the nucleus of the value has a higher pitch peak than the nucleus of the variable, as in (14), or because the value contains a fall while the variable contains a rise.

(14) Hemsley chipping the ball into the centre onto the head of Scullion# from the M^head of Scullion it's JM\ames# that gL\ets it# but only as far as Hockey (LLC–1)

As shown in the Praat image in figure 3, the accent on James has a larger pitch excursion size than the accent on gets. Relative to other accents, the nucleus on James corresponds to a mid single-tone pitch accent, while the nucleus in gets corresponds to a low single-tone pitch accent.

Figure 3. Praat image of example (14)

The opposite order, in which the variable carries the highest-pitched nucleus or in which the final tone of the value is a rise and that of the cleft relative clause a fall, is found in 22 per cent of cases. The results also show that clefts do not always display a hierarchy of information foci, as in (15), in which the accents on beginning and difficult are both mid-falling tone accents with a similar degree of prominence, as shown in the Praat image in figure 4.

(15) A: […] we've only got about thirteen hundred pounds in capital

B: hm hm

A: so although I could imagine that we could hm on our joint salary get perhaps quite a a a high mortgage# it's the paying it back at the begM\inning# that's M^going to be dM\ifficult# (LLC–1)

Figure 4. Praat image of example (15)

Overall, there is a tendency for full clefts to exhibit a stronger degree of prominence on the value than on the variable. However, 22 per cent of occurrences have the opposite order and 13.2 per cent are of equal level of prominence. Hence, the claim that in case of multiple foci the value always carries a ‘stronger’ accent (e.g. Prince Reference Prince1978; Declerck Reference Declerck1984) is not confirmed.

4.2 Discourse-familiarity of value and variable

Table 4, then, summarises the findings of our analysis of the discourse-familiarity of value and variable. Applying Kaltenböck's (Reference Kaltenböck2005) approach, we classified evoked and inferable referents as given, and anchored and brand new referents as new (see section 2.1). The resulting taxonomy consists of four patterns of information distribution: new–given, new–new, given–new and given–given. The given–given pattern has not been pointed out explicitly in existing taxonomies of it-clefts (e.g. Prince Reference Prince1978; Declerck Reference Declerck1984; Geluykens Reference Geluykens1988; Collins Reference Collins2006). While all four patterns occur in full clefts, only two of them are found in reduced clefts. The implied variable of reduced clefts always contains given information, either textually evoked or inferable. This comes as no surprise as the cleft relative clause can be omitted precisely because the variable is recoverable from the context (Declerck & Seki Reference Declerck and Seki1990). Overall, we observe a balance of all four types in full clefts, with the given–new type being slightly less frequent than the other three. This does not tally with Lambrecht's (Reference Lambrecht2001) descriptive claim that the cleft relative clause codes the ‘presupposition’, which ‘is more or less equivalent to the notion “hearer-old”’ (Reference Lambrecht2001: 474). With reduced clefts, the new–given pattern is more frequent than the given–given one.

Table 4. Distribution of information in it-clefts

A point of special interest is the discourse-familiarity of value NPs carrying information focus, which is shown in table 5. While two-thirds of focal values in full clefts are discourse-new referents, one-third designate referents already given in the preceding discourse. For reduced clefts, the proportion of discourse-given focal values is slightly higher at almost 39 per cent.

Table 5. Discourse-familiarity of value NPs

As we will discuss more extensively in section 5.2, this distribution shows that there is no systematic mapping of prosodic prominence and discourse-newness, as has sometimes been suggested.

5 Discussion

As we saw in section 2, there have been two major theoretical influences on the study of English it-clefts as information-packaging constructions, the functional and the formal–pragmatic one. Within this dual historical background, the term ‘focus’ is the most fraught, as it refers to a function in a prosodically coded structure in the functional approach and to a syntactically coded function, the focus phrase, in the formal–pragmatic approach. Tackling these different premises on the theoretical level is beyond the scope of this article, but we can consider the empirically verifiable claims made about prosody and discourse-familiarity within mixes of the two traditions. In this section, our empirical findings about it-clefts in section 4 will be, firstly, related to some existing descriptive claims in the literature, and, secondly and more importantly, used to show what mileage we get out of them within our own approach to information management. We view information flow and communicative purpose as being managed by the speaker's simultaneous prosodic and grammatical choices (O'Grady & Bartlett Reference O'Grady and Bartlett2019). We discuss the interplay between syntax and information foci in section 5.1, and between discourse-familiarity and focal and onset accents in section 5.2. In section 5.3 we examine the interplay of grammatical and prosodic choices in reduced it-clefts.

5.1 The relation between syntax and information foci

Existing informational taxonomies of clefts (e.g. Prince Reference Prince1978; Declerck Reference Declerck1984; Geluykens Reference Geluykens1988; Collins Reference Collins2006) have already pointed out that the prosody of it-clefts is not restricted to one predominant pattern. This point is further corroborated, and refined, by our analysis of the prosodic patterns and the hierarchy of nuclei, which reveals the great variety of information focus choices speakers can make in clefts. Given the highlighting by it-cleft syntax of the value NP, we need to examine the moment-by-moment interplay between the syntax of clefts and their prosodic realisations to manage the information flow. We show this first for clefts with a single information focus, as illustrated in (16)–(18), and then for clefts with foci on both value and variable, as in (19)–(20).

(16) A: was it his first novel the first one he actually wrote

B: no no he was writing A Passage to India at the same time hm and he he stopped writing Passage to India and hm stopped off to write Maurice anyway we

A: oh it was much later than I thought I always got the impression it was

B: I think it was nineteen fiftH\een that he wrote it# (LLC–1)

(17) because there's not the same pressure on the material# it's the the pH\op material that counts# (LLC–1)

(18) A: did you meet Fuller

B: y/es# it was M^he who invH\ited me# (LLC–1)

When speakers choose to use a cleft, it always syntactically foregrounds the whole postverbal NP as the value being specified for the variable, but it offers great possibility of choice for the assignment of information focus via nucleus placement. The selection of information focus is motivated by ‘communicative purpose and the extent of presumed shared information’ (O'Grady & Bartlett Reference O'Grady and Bartlett2019: 192). In (16), the whole value NP nineteen fifteen is focal. It is what Halliday (Reference Halliday1967a: 207) characterises as a marked, non-final, focus, i.e. one that is informationally contrastive (in this context, with the other dates considered for Forster's writing of Maurice) and packages the rest of the information in the unit as a presupposition (see section 2.1). Example (17) also has a marked focus, which moreover singles out the premodifier pop of the value NP only, evoking contrast with the other types of music ‘material’ (classic, etc.) in the library, mentioned earlier in the discourse. This selective focus on pop is related to material that counts, which is discursively anchored–new, but is packaged as a presupposition within the information unit. All of this contributes to the communicative foregrounding of pop. Example (17) illustrates how our functional approach brings out the moment-by-moment interplay between the choice of elements of the prosodically coded information structure (focal–non-focal) and of constituents of the syntactic structure (value–variable) and their discourse-familiarity. In (18), the value, the anaphoric pronoun he referring back to Fuller, carries an onset accent,Footnote 13 but the information focus of the unit is put on the final lexical element of the variable, invited.Footnote 14 In Halliday's (Reference Halliday1967a: 207) approach, this cleft hence has an unmarked information focus (see section 2.1). The cleft relative clause conveys discourse-new, non-predictable information, put forth by B as an indirect response to A's question on whether B had met Fuller.

We now turn to clefts with information focus on both value and variable, which account for 63.6 per cent of our data (see table 2). Within that proportion, we found that foci on the value are relatively more prominent (65 per cent) than foci on the variable, but not as a rule (table 3), as had been suggested by e.g. Prince (Reference Prince1978) and Declerck (Reference Declerck1984). We will reconsider examples (14) and (15), reproduced as (19) and (20), to bring out the interplay between the syntactic constituents and the hierarchically ordered foci as they unfold in real time.

(19) Hemsley chipping the ball into the centre onto the head of Scullion# from the M^head of Scullion it's JM\ames# that gL\ets it# but only as far as Hockey (LLC–1)

In (19), by construing James as the value, the speaker foregrounds the point that James, not any of the other players, got the ball. In the prosodically coded information structure, James is marked by the higher-pitched nucleus as the most salient information that the speaker wishes the hearer to attend to, while gets has a secondary information focus. This is in line with Nelson's (Reference Nelson1997: 346) explanationFootnote 15 of the frequentFootnote 16 use of clefts in live sports commentaries, in which the speaker has to describe and react to a series of fast-paced actions. Clefts allow the speaker to give prominence to the ever-changing identity of the player in possession of the ball, while also putting a secondary focus on the specific actions being described.

Example (20) is taken from a conversation between a salesperson from a building society (B) and a prospective customer (A), discussing problems associated with taking out a mortgage loan.

(20) A: so that that's the kind of problem the other problem is that we haven't got an awful lot of capital we've only got about thirteen hundred pounds in capital

B: hm hm

A: so although I could imagine that we could hm on our joint salary get perhaps quite a a a high mortgage# it's the paying it back at the begM\inning# that's H^going to be dM\ifficult# (LLC–1)

The value consists of unpredictable information that has not been mentioned in the preceding discourse, while the open proposition x is going to be difficult is inferable from speaker A's admission of the problems she faces taking out a big loan. With the cleft, speaker A identifies the initial payments – rather than the capital – as the main difficulty. In the information structure, the speaker first focuses on paying it back at the beGINNing and then on DIFFicult in the cleft relative clause, presenting the two prosodically equal foci as also equally prominent informationally.

We conclude that clefts allow speakers to highlight elements by means of two strategies, syntactic and prosodic, which may reinforce each other or create their own different types of prominence in sequence.

5.2 Information flow management

In this section we consider the interplay between actual textual givenness and newness on the one hand and the speaker's selection of information foci and onsets on the other. As shown in table 4, values and variables can both be either textually new or given. Importantly, full clefts can have a given–given pattern, as in (21), which has not received the attention it deserves in the literature.

(21) A: from Marlborough she has hit Reading at half

B: splendid

A: past eight in the morning

B: splendid agreed but you're not

A: that is that is the other side of Reading going into Reading I will be the other side of Reading going into Reading that's where she hit the traffic traffic going in to Reading from either side

B: no you've missed the point the traffic you are worried about is the traffic going towards London

A: no Petey at half past eight in the morning

B: there is not a mysterious line which divides traffic going to London immediately at Reading

A: no but there is traffic there is a traffic rush hour at Reading when traffic piles into Reading# and it is aH^bout eight thM\irty# that my H^mother has gotten stM\uck# in H^traffic trying to get into RH\eading# (LLC–1)

In this excerpt, the two speakers are arguing about the traffic between London and Reading in which A's mother got stuck. The value of the cleft is given verbatim in one of the previous turns, as underlined, and the variable is easily derivable from that's where she hit the traffic […] going in to Reading. Moreover, the relation between these elements has already been established by speaker A in the first utterance of this excerpt.Footnote 17 The cleft comes as a closing statement meant to resolve the disagreement between the two speakers. Speaker A reasserts all the points she had already made about her mother's traffic conundrum, assigning information foci to the crucial elements, about eight th\irty, has gotten st\uck, into R\eading, all carrying assertive falling tones. Moreover, each of these three tone units contains a high onset (indicated by small capital h before ^), by which speaker A signals that she assumes a position contrary to that assumed by speaker B in their discussion.

In (22), the speaker uses a cleft to move from a general current concern, i.e. having negative feelings towards rock and roll singers, to the recalling of a specific instance of this. Both value and variable contain discourse-new information. Collins (Reference Collins2006: 1713) observes that in examples like these the proposition is held ‘in store’ in anticipation of its relevance to the unfolding discourse.

(22) there's something that makes us feel savage about these rock and roll singers and I hate it in myself and I see it in a lot of other people# now it's H^only about a year agM\/o# - that H^on this prM\ogramme# H^we were asked about I think it was Tommy StM\/eele# being mM\obbed# and I remember making some perfectly horrible remarks (LLC–1)

In (22), a new temporal setting, carrying information focus, is introduced in the syntactically highlighted value-position, it's about a year ago. This new temporal setting is added to the common ground shared between speaker and hearer and provides the knowledge necessary to engage with and react to the upcoming information in the cleft relative clause. The new information in the cleft relative clause is put across in three information units. Three of the four information units of the cleft have high onsets, including at the beginning of the cleft construction, which signal the reset involved in shifting from general current concern to a specific temporally located instance of it.

High onsets are an important feature of the prosody of clefts, whose informational and interactional meanings warrant study. In the it-clefts in our data, the onsets at the beginning of the whole construction are all high. This means that clefts are always used in our data to signal a reset vis-à-vis what preceded – be it another speaker's turn, as in (21), or the speaker's own previous utterance, as in (22). Onsets in the tone unit of the value NP serve specific rhetorical and interactional effects, which may link up with the typical discursive functions of specificational clefts.

In the full cleft in (23), the high onset on the negator not reinforces the contrastive focus on the value philologists, which is rejected as the value of x you want to convince. The following reduced cleft then provides the accurate value people who have the money. A Praat image is given in figure 5.

(23) A: […] those English philologists that I have met are in that I've talked to are most enthusiastic

B: uh it's H^not philM\ologists# you want to cM\onvince#

A: hm

B: it's the people with m\oney# (LLC–1)

Figure 5. Praat image of example (23)

In (24) the high onset on the adverb only makes explicit the implicature of exhaustiveness triggered by the identifying matrix: when they turn facing us specifies the only condition under which you get the underside full on.

(24) A: yes two of them sitting there the thing that that catches the eye if anything does is the white underside when they're sitting upright but uh perhaps the the most obvious thing is how well camouflaged they are in fact how inconspicuous they are hm

B: yeah# - it's H^only when they turn fM\acing us# that you L^get the

A: yes

B: the M\underside# - H^full M\on as it were# (LLC–1)

In sum, clefts attest each possible distribution of discourse-given or new information over value and variable, including given–given and new–new. Speakers can impose multiple foci on the points they want the hearer to sequentially attend to, irrespective of whether all the propositional material is already present in the context, as in (21), or is textually new, as in (22), or is partly given and new. But when it comes to the initial onset of the cleft, the speakers in our data always realise a high onset. In our data, it-clefts hence always convey that there is some reset (change of topic, disruption, contradiction, etc.) vis-à-vis the preceding utterances.

5.3 The interplay of grammatical and prosodic choices in reduced clefts

Although the existence of ‘reduced’ or ‘truncated’ clefts is acknowledged in a number of studies on clefts (see Declerck Reference Declerck1983; Declerck & Seki Reference Declerck and Seki1990; Hedberg Reference Hedberg2000; Collins Reference Collins2006; Mikkelsen Reference Mikkelsen, Geist and Rothstein2007), their description often remains limited. Reduced clefts are generally viewed as the monoclausal variant of full clefts whose variable is not realised. Our data support this description in so far as all variables of reduced clefts were found to be present, in part or in full, in the previous discourse context and could therefore be reconstructed. This is in line with Hedberg's (Reference Hedberg2000) findings on the correlation between the high degree of givenness of the unexpressed cleft relative clause and the selection of reduced clefts over full clefts. Example (25) exemplifies this idea. The presupposed open proposition x is banging on the ceiling can be inferred from the preceding discourse and does not need to be reiterated in order to be understood by the hearer.

(25) and how she heard repeated bangs on the ceiling# thinking it was her sM\on# [who was banging on the ceiling] she finally dashed upstairs to to confront him with it# (LLC–1)

However, although all reduced clefts are characterised by a variable that consists of given information, not all discourse-given variables are necessarily omitted. Hedberg (Reference Hedberg2000) argues that in order to accurately account for the use of reduced clefts, a distinction should be drawn between the different types of discourse-given variables, e.g. in focus, activated, familiar, uniquely identifiable. Thus, a variable that is in focusFootnote 18 in Hedberg's (Reference Hedberg2000) terminology, i.e. representing a highly salient matter of current concern, like that in (26), can be omitted but a variable that is activated but not in focus will most likely yield a full it-cleft and not a reduced one. This is exemplified in (26) where the reduced cleft it was your wife's phone message would not be enough to convey the specification relation between the value and the variable x caused the doctor to bring the details of the nursing homes as it is not in focus or salient enough.

(26) A: yes but that would account for him bringing the details of the nursing-home

B: well not necessarily no I phoned him on Friday morning and told him I wanted mother to go into a nursing-home

A: yes

B: and the doctor said he thought it was not necessary at all

A: yes quite right you see what I'm (coughs) asking is this your suggestion is# that H^it was your wH\/ife's phone message# that M^caused the dM\octor# to M^bring dM\etails# of the nH\ursing-homes# (LLC–1)

While it would be tempting to assume that reduced clefts are simply the unmarked option for clefts with discourse-given variable, the picture is in fact more complex. In our dataset, full clefts with a given variable represent 54 per cent of all full clefts and those with a textually evoked variable, i.e. explicitly mentioned in the preceding context, make up 45 per cent of full clefts with a given cleft relative clause. We argue that the choice of a full cleft with a discourse-given variable may be motivated not only by a lower degree of activation of the information it carries but also by rhetorical reasons. In an example like (27), whose full context is cited as (21) in section 5.2, a reduced cleft would not work and a non-cleft construction would fail to achieve the speaker's discursive purpose of closing the argument by reasserting all main points.

(27) and it is aH^bout eight thM\irty# that my H^mother has gotten stM\uck# in H^traffic trying to get into RH\eading# (LLC–1)

By the same token, reduced clefts have their own potential for realising rhetorical goals. Our data show that there are two discourse contexts in which speakers are particularly inclined to select reduced clefts. Firstly, they are often used in answer to wh-questions, which presuppose a proposition and inquire into one of its elements. In (28), speaker B is asked about the reasons driving Chaucer's pardoner to behave the way he does. A answers first with the NP not something outside himself, indicating what (kind of) value does not fill the semantic gap in the presupposed proposition, and then produces a reduced cleft specifying the values that do fill the gap in the open proposition, which itself does not need to be restated.

(28) A: and what is the pardoner being driven by - - -

B: well not not something outside himself really# it's his H^own - desire for mH/oney#

A: hm

B: I suppose# H^and a sH\/ort of power# (LLC–1)

Secondly, reduced clefts are frequently used to establish an overt contrast between two or more values. In (29), the reduced cleft contrasts the surveyor and the person who did the structural with the Abbey National with regard to the question of who should be blamed. In (30) the speakers are debating the question of who the most powerful person in the family was. Speaker A first uses a wh-interrogative pseudo-cleft, which asks this question in an open-ended way (who is the person who has the ultimate say about things?) and then produces an interrogative it-cleft. The nuclear accent on the copula be conveys that speaker A questions speaker C's suggestion that it is the daughter who is the dominant person. Speaker A ends with a reduced interrogative it-cleft contrastively proposing the father as value.

(29) A: you know the Abbey National's not to blame in the least

B: no

A: it's the the survL\/eyor# and H^the person who did the strM\uctural# (LLC–1)

(30) A: would you say that Dad is really the powerful person in the family

C: I'm not sure that the girl isn't in a way

[…]

A: we were saying at least that I I feel it's very important to get a to get to know who is the person who really hm has the ultimate say about things in the home

B: hm

A: whether it M\/is this daughter# who's H^taken on the role of

C: hm

A: mM/other# - or H^whether it is fM\ather# - because there were sort of hints about father being a fairly well suggesting that he was quite a severe man (LLC–1)

With regard to the prosodically coded information structure, reduced clefts overall show much less variation in patterns due to the omission of the cleft relative clause. The value is in the vast majority of cases focal except for cases in which the copula carries the information focus, which is illustrated in the full cleft in (30).

We conclude that reduced clefts are more than an informationally motivated variant of it-clefts, the unmarked option for clefts with discourse-given variables, so to speak. This would leave the large proportion of full clefts with discourse-given, and even textually evoked, variables, like (21) above, unexplained. Rather, reduced clefts are, like full clefts, a construction in their own right with their own potential for achieving specific rhetorical effects, such as contrasting values, and for appearing in specific discourse contexts.

6 Conclusion

In this article we have addressed the way speakers manage information flow in full and reduced specificational it-clefts. Situated within the traditions of functional linguistics and the British school of intonation, our theoretical framework assumes that speakers balance grammatical and prosodic choices in real time in view of the extent of shared speaker–hearer information and the speaker's shifting communicative purposes (O'Grady Reference O'Grady2010; O'Grady & Bartlett Reference O'Grady and Bartlett2019).

We have reported the qualitative and quantitative results of our corpus study of the full and reduced it-clefts extracted from the first London–Lund Corpus. We studied the tones, tone units, nuclear accents, onsets and the relative pitch height of the latter two, enabling comparison. We first confronted these results with existing descriptive claims in the literature, and then interpreted them within our own approach to information management.

We have shown that informational highlighting is achieved through the interplay between the cleft's bi-clausal syntax and the coding of focus through accent placement, which may reinforce each other or create their own different types of prominence in sequence. The hypothesis that the focus on the syntactically highlighted NP is always more prominent than foci on other constituents was shown not to hold. We also studied the onset, i.e. the relative height of the first pitch accent of the cleft, which projects how the upcoming propositional material relates to the expectations generated by the preceding context. Strikingly, in our data clefts always have a high onset, signalling some disruption of expectations, which can be linked to typical discursive functions of clefts such as establishing an overt contrast or expressing exclusive focus. All the different possibilities of informational highlighting afforded by clefts make them a particularly useful device for speakers responding moment by moment to informational needs and shifting communicative goals.

Our study of the distribution of textually new and given information over the clefts’ syntactic constituents confirmed existing typologies positing new–given, new–new and given–new patterns. At the same time, we pointed out the hitherto neglected given–given pattern, which, if we put full and reduced clefts together, is the second most common pattern in our data. Reduced clefts were found to show less variety than full clefts in both their informational and prosodic patterns, which was expected in view of the absence of a cleft relative clause. However, reduced clefts could be linked to some specific discursive functions such as providing the value for a wh-question and specifying contrasting values, often in sequence with full clefts. Hence, we concluded that reduced clefts are not just informationally motivated variants of full clefts, but serve specific rhetorical effects.

Appendix: Transcription symbols

- /

Rising tone

- \

Falling tone

- \/

Fall-rising tone

- #

Tone unit boundary

- ^

Onset

- H

High level

- L

Low level

- M

Mid level

- {}

Subordinate tone unit boundaries

- -

Pause