1 Introduction

Almost twenty years ago, Beal (Reference Beal2004a: 124) remarked that studying the pronunciation of Late Modern English (LModE, c. 1700–1900) had long been neglected because the period had often been regarded as too close to and not considerably different from present-day English. However, the pronunciation of LModE was indeed markedly different as changes like the diphthongisation of goat and face, bath-broadening and the loss of rhoticity in Britain, Australia and New Zealand show (see also Beal Reference Beal and Britton1996, Reference Beal1999, Reference Beal2004a; MacMahon Reference MacMahon and Romaine1999; Jones Reference Jones2006; Mugglestone Reference Mugglestone2007). The lack of research in this area has also been connected to the absence of material in digital form. Since the 1990s this has changed, at least for the eighteenth century, with the compilation of the Eighteenth-Century English Phonology (ECEP Reference Beal, Yáñez-Bouza, Sen and Wallis2015) and Eighteenth-Century English Grammars (ECEG Reference Rodríguez-Gil and Yáñez-Bouza2010) databases and corresponding publications on eighteenth-century phonology (see Beal Reference Beal2013; Yáñez-Bouza et al. Reference Yáñez-Bouza, Beal, Sen and Wallis2018; Yáñez-Bouza Reference Yáñez-Bouza2020; Beal et al. Reference Beal, Sen, Yáñez-Bouza and Wallis2020a). Moreover, several studies have been conducted on recordings of speakers born in the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (see Trudgill Reference Trudgill2004a; Hay & Sudbury Reference Hay and Sudbury2005; Trudgill & Gordon Reference Trudgill and Gordon2006; Mair Reference Mair, Kytö and Pahta2016; Hickey Reference Hickey2017; Przedlacka & Ashby Reference Przedlacka and Ashby2019). Some studies have furthermore focused on normative discourses on phonological change in LModE (see Beal & Sturiale Reference Beal and Sturiale2012; Beal & Iamartino Reference Beal and Iamartino2016). Other contributions in the present issue like Gardner (Reference Gardner2023) provide sociolinguistic accounts of ‘Speech reflections in Late Modern English pauper letters from Dorset’ and look at features such as /h/-dropping and insertion, kit lowering and final consonant deletion.

While attitudes to studying LModE pronunciation have evidently shifted in recent years, there is still a considerable amount of ground to be covered. Looking at nineteenth-century material is important not only for the sake of gaining a more complete picture of the pronunciation of LModE, but furthermore to understand how several socio-economic changes, advancements in the sciences and rising literacy rates might have influenced language change. As publications such as Ellis’ (Reference Ellis1869) Early English Pronunciation and Henry Sweet's (Reference Sweet1877) A Handbook of Phonetics illustrate, the century also marked a shift to a more scientific treatment of pronunciation and towards the development of phonetics as a science. Further, it was a vital period in the standardisation process of spoken English, culminating in the emergence of the supra-regional prestige variety RP in England. The nineteenth century was also important with respect to the emergence of American English as a separate variety (see Paulsen Reference Paulsen2022: 88–106).

From the perspective of available data, there was an enormous increase in publications of English grammars in the nineteenth century. In fact, Görlach (Reference Görlach1998) provides a list of 1,936 grammars that were published throughout the century. Anderwald (Reference Anderwald2016) compiled the Collection of Nineteenth-century Grammars (CNG) containing 258 of these grammars from Britain and North America, including one Canadian, four Irish and nine Scottish grammars. This collection serves as the main data in the present article. Anderwald (Reference Anderwald2016) collates the Irish and Scottish grammars under the category of British grammars. I also adopt this categorisation and further mark any North American grammars from the CNG with an asterisk in the running text to more easily differentiate the places of publication of these works. The grammars in this collection are mostly first editions and were written by native speakers of English for the purpose of teaching (see Anderwald Reference Anderwald2016: 10–15 for more detail on the CNG). Crucially, LModE grammars in general often feature discussions on pronunciation in sections on Orthography and sometimes also Orthoepy and are thus different to the typical make-up of present-day grammars, which mostly focus on morphology and syntax (see Görlach Reference Görlach1998; Beal Reference Beal2013). In fact, there are 166 grammars in the CNG – 64 per cent of the complete collection – that contain information on phonological variables. Thus, these grammars offer a fruitful resource for further research on the history of English pronunciation in LModE. Nevertheless, they have largely remained untouched by scholars working in the field of historical phonology. Therefore, this article presents evidence from the CNG for two major LModE changes in British and North American prestige varieties, namely the diphthongisation of the vowel in goat from /oː/ to /ou/ and the development of /r/, including its loss in post-vocalic position in Britain.

Previous research suggests that diphthongal goat variants had become common in (proto-)RP, General American (GenAm) and several other varieties of English towards the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century. However, evidence from early in the nineteenth century, for its diffusion through the lexicon and for a potential influence from dialects that had maintained earlier Middle English (ME) /ɔu/ variants (see section 2.1), is scarcer. Therefore, my aim is to evaluate the extent to which nineteenth-century grammars provide evidence for early diphthongisation. Given the complex history of words now collated under the goat set, I examine whether any orthographic or phonological environments favour diphthongal goat realisations. Existing research on /r/ indicates that regional and prestige varieties that are non-rhotic today were still at least partially rhotic in the nineteenth century (see Trudgill Reference Trudgill2004a: 69). Precise descriptions of the process of /r/-loss and the articulatory properties of /r/ are, however, hard to find before Ellis (Reference Ellis1869) and Sweet (Reference Sweet1877). Thus, this article aims to show whether grammarians provide evidence of the distribution and properties of different /r/ variants and post-vocalic /r/-loss. One overarching goal of this article is to evaluate how far grammars are suitable sources for the study of historical phonology.

I show that the vowel in goat words was the prime example of what grammarians called ‘improper diphthongs’ throughout the nineteenth century and that the earliest evidence for diphthongs comes from 1845. With respect to /r/, British and North American grammars continued to propose a twofold distinction of /r/ sounds throughout the century. Unfortunately, more often than not insightful articulatory descriptions are wanting. Furthermore, I show that there is a considerable overlap in the terminology used by grammarians to describe both features, including what I assume to be verbatim copies from authors such as Walker and Murray. Thus, I argue that nineteenth-century grammars should be treated with caution as a source for studying historical phonology as they cannot all be regarded as independent witnesses.

This article is structured as follows: in section 2.1, I start by giving an overview of the historical development of goat diphthongisation. Section 2.2 discusses monophthongal and diphthongal descriptions of the vowel in the CNG. Section 3 is devoted to the second feature, namely /r/. Similarly, I commence by describing the historical development of different /r/ variants and post-vocalic /r/-loss (section 3.1). The next section (3.2) is divided into three subsections, ordered by the number of sounds grammarians proposed for /r/: one sound, two sounds and /r/-lessness in post-vocalic position. In the final section, I discuss the implications of my data and point to limitations of the CNG as a database for investigating the history of pronunciation. I furthermore give an outlook on opportunities for future work in the fields of historical phonology and nineteenth-century grammar writing.

2 Analysing the vowel in goat

2.1 Historical background

Before going into the specifics of the evolution of /ou/, it is important to note that Wells’ (Reference Murray1982) goat and force sets both historically contained the vowel traditionally known as ‘long o’ and were thus often regarded as the same category by LModE writers. The goat set comprises the following spellings: <o, oCe, oa, ow, ou> in words such as no, note, boat, know and dough, and <o, ou> before <l> in words like roll and soul. Affected pre-/r/ spellings are <or, ore, oar, oor > and <our>, which can be found in words like sport, fore, coarse, door and four (cf. Wells Reference Wells1982: 146–7, 160–2). Furthermore, the vowel in goat words has two different sources, namely late ME /ɔː/ and /ɔu/. The former was used in words like no, while the latter occurred in <ow>, <ol(C)> and <oul> spellings in words like know, toll and shoulder. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries /ɔu/ then monophthongised and merged with /ɔː/ (cf. Lass Reference Lass and Lass1999: 93). However, the Scottish lexicographer Buchanan (Reference Buchanan1757) still has /ɔu/ for words like tow and shoulder (see ECEP Reference Beal, Yáñez-Bouza, Sen and Wallis2015). According to Trudgill (Reference Trudgill2004a: 55), this distinction had been maintained in many nineteenth-century accents. It is also still present in some regional varieties of English today (see for instance Beal Reference Beal2004b: 124; Trudgill Reference Trudgill2004b: 170–1). In prestige speech, however, monophthongs of the quality [oː] were the dominant form in goat and force words at the end of the eighteenth century. I will follow the conventions adopted in the ECEP (Reference Beal, Yáñez-Bouza, Sen and Wallis2015) and refer to words historically related to ME /ɔu/ as the goat_b subset and to all other contexts as goat_a. MacMahon (Reference MacMahon and Romaine1999: 459) names the Scottish scholar William Smith (Reference Smith1795) as the first author to explicitly mention diphthongal pronunciations in goat. Jones (Reference Jones2006: 303), however, claims that it is not until the middle of the nineteenth century that diphthongal variants were established in prestige speech ‘at the earliest’. Based on Ellis (Reference Ellis1889), Trudgill (Reference Trudgill2004a: 52–3) shows for regional accents that the diphthongisation of face of goat was in its early stages of development in the nineteenth century.

John Walker (Reference Walker1791: 21, 34–8) describes this sound as the ‘long open sound’ of the letter O, which occurs in words such as no, goat, toe, door, though, know. He therefore proposes a monophthong, i.e. [oː], and still includes the force set. Beal (Reference Beal2004a: 138) points out that his use of the word ‘open’ is characterised by relative openness in contrast to Walker's (Reference Walker1791) ‘slender o’, i.e. [uː]. Moreover, the sound in words like coat and crow are labelled ‘improper diphthongs’ by Walker (Reference Walker1791: 26). Murray (Reference Murray1795: 4) similarly contends that ‘[a]n improper diphthong has but one of the vowels sounded; as, ea in eagle, oa in boat’. It is important to bear in mind that a clear-cut distinction between spelling and pronunciation is still lacking in the majority of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sources that have been consulted for the present article. Smart (Reference Smart1836: v) remarks that in London the sound of ‘ō’ (long o) is ‘not always quite simple, but is apt to contract toward the end, finishing almost as oo in too’ and thus records diphthongal variants in London speech. Ellis (Reference Ellis1869: 602), however, noticed a difference in some speakers between no and know, with the former containing monophthongal forms and the latter having diphthongal realisations. Furthermore, he observes in his own phonology that <ow> spellings as in know regularly have a diphthong, and that for <o> spellings in unchecked syllables like no, he often uses diphthongs (Reference Ellis1874: 1152). The quality of these diphthongs is [oː] plus what he calls ‘a labial modification’ of [w] (Ellis Reference Ellis1869: 9).Footnote 1 What Ellis is describing here could represent the history of the vowels in <o> and <ow> spellings in the goat_a and goat_b sets (cf. MacMahon Reference MacMahon and Romaine1999: 412). However, Ellis states (Reference Ellis1874: 1152) that the vowel is most likely to diphthongise before a pause and before /p/ and /k/ and least likely preceding the alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/. As regards diphthongal pronunciations of the word boat, Ellis (Reference Ellis1874: 1152) claims that [ou] ‘is not only strange to me but disagreeable to my ear and troublesome for my tongue’ and adds that even a diphthong of the quality [oːw̹] in boat, i.e. one with a longer onset, ‘sounds strange’. He further argues that a consistent use of diphthongal forms in the goat and face sets ‘as the only received pronunciation thoroughly disagrees with my own observations’ (see also MacMahon Reference MacMahon and Romaine1999: 411–12, 459–61 on Ellis’ discussion of /oʊ/). In contrast, what we would, from a present-day perspective, consider ‘traditional RP’ (cf. Upton Reference Upton2004) has a diphthong across all spellings and phonological environments of Wells’ (Reference Wells1982) goat set. Jones (Reference Jones1964: 103), however, notes that ‘[t]he English vowel o occasionally appears without a following u, but only in unstressed syllables and before another vowel’ as in words like obey or November. Moreover, he notices that many speakers do not seem aware of the diphthongal quality in open syllables like so and home (cf. Jones Reference Jones1964: 102). Centralised onsets now typical in RP were first noted towards the end of the nineteenth century, while they became established as the standard variant in British prestige speech only during the twentieth century (cf. Wells Reference Wells1982: 237; MacMahon Reference MacMahon and Romaine1999: 460–1; Beal Reference Beal2004a: 138).

Regarding the vowel system in North American English, Webster's (Reference Webster1790: 13–14) list of diphthongs only includes <oi, oy, ou> and <ow> spellings in words like voice, joy and loud, and thus essentially the choice and mouth sets. In contrast, the word note is described as containing ‘long o’. Similar to Walker (Reference Walker1791), in Worcester (Reference Worcester1859: 14–16) we find [oː] described as the traditional ‘long o’ in a variety of different spellings comprising goat and force words like no, goat, door, court, though and know. For Krapp (Reference Krapp1919: 37), the vowel in goat has a long monophthong before voiceless consonants such as note and boat, but diphthongal variants with the value [ou] before voiced consonants and in open syllables as in road, toe, know, though and others. He does, however, add that the latter environments and words like oath ‘are often pronounced simply with [oː]’ (Krapp Reference Krapp1919: 94). Before consonants the diphthongal quality is described as ‘less marked’, while Krapp (Reference Krapp1919: 73, 81) also notes that ‘a slight glide [ə] … is sometimes present’ in words like stole. Force words have a number of possible realisations for Krapp (Reference Krapp1919: 85, 88), namely [ɔː] [ɔˑ], [ɔːə], [ɔˑə], [oː], [oˑ], and [o]. The more raised variants, nevertheless, are identified as older and as restricted to <or>-spellings. Even some GenAm speakers today maintain a distinction between force [or ~ oɚ] and north [ɔr ~ ɔɚ] (see Wells Reference Wells1982: 160–1; Kretzschmar, Jr Reference Kretzschmar2004: 264). Archival data from speakers born between 1850 and 1960 furthermore show the presence of monophthongal variants throughout the regions of the Upper Midwest (cf. Purnell et al. Reference Purnell, Raimy, Salmons and Hickey2017: 321).

2.2 goat in the CNG

Concerning goat in the CNG, 99 grammars (i.e. 60 per cent of grammars in the CNG that treat pronunciation) either allow us to deduce a quality for the vowel in goat words or explicitly mention it. These thus include grammars that explicitly refer to the vowel in goat words as ‘simple vowel’, ‘pure sound’, ‘improper diphthong’ or the like, but also those that provide a list of diphthongs of the English language that lacks any goat spellings. The latter grammars are thus implicit evidence of monophthongs as we can often only derive this information based on the absence of goat words in the grammarians’ lists of English diphthongs.

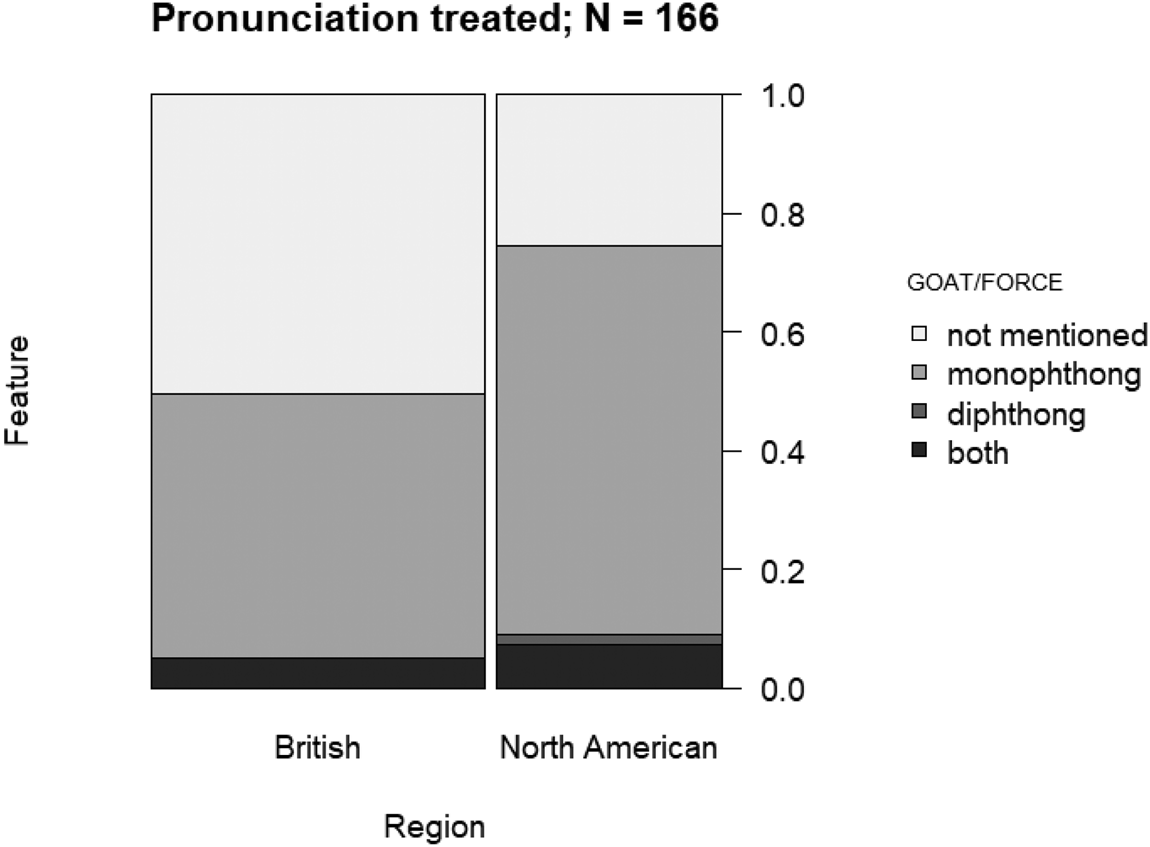

In absolute terms, the results are regionally balanced. However, if we consider that fewer North American grammars treat pronunciation to begin with, relatively speaking fewer British grammars provide information on the vowels in goat and force words as illustrated in figure 1. N stands for the total number of grammars that treat pronunciation. The y-axis illustrates the percentage of goat and force variants mentioned in relation to N (see table A1 in the Appendix). Evidence for diphthongal variants can be found in 11 grammars in total (5 British and 6 North American). It is worth noting that not all of these grammars consider every possible spelling. In fact, <oa> spellings are by far the most prominent words that are treated in connection with this vowel. However, this is mostly due to the fact that <oa> spellings appear to be the prime examples of ‘improper diphthongs’ for many grammarians in the CNG. Therefore, even if a grammar does not feature a lengthy treatment of pronunciation but just gives definitions of different types of sounds under the heading orthography, <oa> spellings are mentioned. All cases of ‘improper diphthongs’ have been counted as monophthongs.

Figure 1. Evidence for goat and force variants in the CNG

2.2.1 Monophthongs

Forty-three of the 88 grammars (52 per cent) that propose monophthongs for the vowel in goat identify them as ‘improper diphthongs’. It is in 41 of these grammars that <oa> spellings, and often exclusively the word boat, are used as examples of ‘improper diphthongs’. However, grammarians also make use of other terms such as ‘impure diphthong’, ‘pure vowel’, ‘simple vowel’, ‘regular vowel’, ‘monophthong’, ‘digraph’ and ‘digram’. The grammarians’ arguments are often similar to Walker (Reference Walker1791) since they suggest that the affected words contain two graphemes representing vowels of which only one is actually realised in speech; hence, they are treated as ‘improper’, as illustrated in (1).

(1) Q. 20. Diphthongs are of two kinds, proper and improper. Can you define them? A. A Proper Diphthong has both the vowels sounded; as, oi in voice, ou in sound. An Improper Diphthong has only one of the vowels sounded; as, oa in boat, ea in bread. (Caldwell Reference Caldwell1859: 18–19)*

Five grammarians in the collection, however, criticise the term ‘improper diphthong’ as it is based on the spelling of the word rather than the actual pronunciation (Crombie Reference Crombie1809: xvi; Fisk Reference Fisk1822: 37*; Barnes Reference Barnes1854: 8; Hart Reference Hart1864: 9*; Mulligan Reference Mulligan1868: 56–7*). Turner (Reference Turner1840) also describes the vowel as an ‘improper diphthong’ and calls it ‘open o’. In his grammar, force words are part of the same category, as words like court and four are said to also contain ‘open o’ and are named in the same instant as dough and though.

Twenty-four of the grammars (27 per cent) that propose monophthongs also include spellings from the force set in the same category. Nevertheless, grammars similar to Turner (Reference Turner1840) are usually very thorough as they walk their readers alphabetically through every possible spelling of vowels and consonants and consistently employ the same terms, e.g. ‘improper diphthong’ and ‘long o’ or ‘open o’. This way of elaborating on the sounds of English was customary already in authors like Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780), Walker (Reference Walker1791), Murray (Reference Murray1795) and to a certain degree also Webster (Reference Webster1790), who all proceeded in a similar fashion.

2.2.2 Diphthongs and variation

As concerns the timespan of diphthongal variants in the CNG, two grammars are from 1845 (Atkin Reference Atkin1845; Frazee Reference Frazee1845*) and three from the 1850s and early 1860s (Brown Reference Brown1851*; Fowler Reference Fowler1855*; York Reference York1862*). The remaining six instances are found in grammars from the close of the century, published between 1880 and 1902 (Speers Reference Speers1880; Hall & Sonnenschein Reference Hall and Sonnenschein1889; Gow Reference Gow1892; Ramsey Reference Ramsey1892*; Nesfield Reference Nesfield1900; Carpenter Reference Carpenter1902*). However, there is no evidence of centralised variants in the CNG. Table 1 provides an overview of all the evidence of diphthongisation in my data, sorted chronologically, and including information on the spelling and the phonological environment in which diphthongs are described. Moreover, it shows the example words used by the grammarians to illustrate the sounds, the lexical sets to which they pertain and my interpretation of the sound in modern IPA. The spellings mentioned only serve as examples for the grammarians and it is possible that diphthongs may have been used in other contexts.

Table 1. Evidence of goat and force diphthongs in the CNG

aBased on Rush (Reference Rush1827: 62). However, Brown (Reference Brown1851)* argues against Rush's scheme.

bBased on Rush (Reference Rush1827: 62).

In Atkin (Reference Atkin1845: 6), which is one of the ‘catechism’ grammars (like Caldwell Reference Caldwell1859*, illustrated in (1)), the teacher asks the student to provide examples of ‘proper’ and ‘improper’ diphthongs and give an explanation as to why that is the case. The student answers that oa in the word coat is a proper diphthong, i.e. a diphthong in our modern sense of the word. Their reasoning is that if it were only the a that was pronounced, the word in question would be cat – without the a it would be cot; hence the explanation is based on orthography. This is, however, a phonologically and historically implausible argument for a diphthongal realisation. Based on that reasoning every digraph that stands for a vowel would have to be realised as a diphthong. Amongst the ‘improper diphthongs’ we can find words such as crow. For Atkin (Reference Atkin1845: 6), <oa> spellings before a voiceless plosive are thus treated as diphthongal, while <ow> spellings are not. Frazee (Reference Frazee1845: 11)* from the same year illustrates diphthongal sounds or ‘compound sounds’ by providing the examples fine, tube,Footnote 2 toil and count, i.e. the price, choice and mouth sets, and goose after /j/. He then uses the vowel in the word boat as an example of a digraph, i.e. one vowel represented by two graphemes. Since he does not list <oa> spellings as examples of ‘compound sounds’ but of digraphs, we can confidently contend that this vowel is supposed to be a monophthong for him. Interestingly, three pages further into his grammar he provides a list of ‘monophthongs or vowels’ and one of ‘diphthongal sounds’, of which the latter category contains ‘Long o, as in vote, hope’ (Frazee Reference Frazee1845: 14)*. He elaborates that the O in the word ode ‘has its own peculiar radical, and its vanish is the sound of oo in ooze’. Therefore, he suggests a diphthong ending in [u] for <oCe> spellings, while <oa> spellings in boat are regarded as monophthongs.

Brown (Reference Brown1851: 152, 169)* provides loaf as an example of ‘improper diphthongs’, but remarks that his contemporary Rush (Reference Rush1827) suggests the o in old to be diphthongal. However, Brown (Reference Brown1851: 152)* does not seem to approve of this classification as the following statements show: ‘he [Dr Rush] begins by confounding all distinction between diphthongs and simple vowels …. But in the a of ale, he hears ā’-ee … in the o of old, ō’-oo’. Brown continues by calling Rush's descriptions ‘mysteries’ and eventually ends his treatment of Rush's vowel system with a sarcastic comment ‘My opinion of this scheme of the alphabet the reader will have anticipated’. In the appendix of his grammar, he identifies every possible goat and force spelling as ‘open or long o’ (Brown Reference Brown1851: 1006)*. While he thus proposes monophthongs for the two lexical sets, he still provides evidence for the presence of diphthongisation in his contemporaries’ phonology in the goat_b set.

Fowler (Reference Fowler1855: 145–6)* lists the word note under vowel sounds, whereas the vowels found in fine, rude, house and voice are collated in the category ‘compound vowel sounds’, i.e. his equivalent of diphthongs. Discussing different representations of the same sounds, he contends that all possible spellings have the long monophthong also found in note (Fowler Reference Fowler1855: 212)*. The only evidence for the existence of diphthongal variants that Fowler (Reference Fowler1855: 145)* provides is when he illustrates Rush's classification, where old is described as a diphthong. York (Reference York1862)* is the sole grammarian that only mentions a diphthongal variant for force, which he in fact calls a triphthong. He embraces terminology that is admittedly based on Comstock (Reference Comstock1808), namely the use of ‘radical’ and ‘vanish’ to refer to the first and second segments of diphthongs. For words like more he moreover adds the ‘median’; hence making it a triphthong. In Comstock's (Reference Comstock1808: 19) system this vowel is also found in old and no. York's (Reference York1862)* scheme suggests that the ‘radical’ and ‘median’ are the same sound, namely ‘ō’ and that the ‘vanish’ is ‘w’. However, his symbol for the triphthong itself is ‘ō’. Thus, his description is circular.Footnote 3 In Comstock's (Reference Comstock1808: 21) original system the first sound of this triphthong is ‘a sound characteristic of this element’ and the second and third element is the ‘diphthong’ he describes for too and move. The different elements of the triphthong involve ‘gradual diminution of the aperture of the mouth’ (Comstock Reference Comstock1808: 23). Unfortunately, neither Comstock nor York is very specific on the quality of these vowels. However, based on their descriptions, I would suggest a quality somewhat like [ouw].

As for the late nineteenth-century sources, Speers (Reference Speers1880: 7) claims that the vowel in the word cloak is an ‘improper diphthong’. However, he states that the letter <w> ‘is a vowel when it is united with another vowel going before, as in cow, flow’ and therefore suggests that the vowel in flow is a diphthong, analogous to the word cow, about which he writes ‘Notice that w = u in cow, which would be pronounced quite the same if spelt cou.’ This could be a claim based on spelling analogy to <ow> mouth words or relate to the historical difference between the vowel in goat_a and goat_b sets. Hall & Sonnenschein (Reference Hall and Sonnenschein1889: 60) categorise the goat words no, boat, toe, crow, soul and sew as ‘simple vowel sounds’ as opposed to diphthongs and transcribe them as ‘o’. Force words, on the other hand, are listed separately and transcribed as ‘ɔ’. However, they add a general remark, which reads ‘Long Vowels in Mod. Engl. are rarely pure (i.e. uniform) vowel sounds, but have mostly become diphthongal in character: … the o of “no” ends in faint oo [u] sound’ (Hall & Sonnenschein Reference Hall and Sonnenschein1889: 60; square brackets in the original). Gow (Reference Gow1892: 6, 11) and Carpenter (Reference Carpenter1902: 228)* describe diphthongal variants in a similar fashion.

Ramsey (Reference Ramsey1892: 149)* provides evidence for a less marked diphthong in the word know, which we could perhaps transcribe as [ou]. He writes about the letter <w> that ‘[a]fter o it either forms a perfect diphthong, as in now, or is very faintly heard, as in know’. In <ou> spellings before /l/ such as the word soul, Ramsey (Reference Ramsey1892: 167)* also describes a diphthong, likely similar to that in know as his use of the word ‘faint’ suggests: ‘It [the spelling <ou>] was next employed to express the sound of o in soul, in which some think they hear both vowels – a distinct o, followed by a very faint (u).’ Based on Ellis, he also suggests that the vowel in no is diphthongal (Ramsey Reference Ramsey1892: 164)*. He furthermore notes that words like glory are increasingly pronounced as if spelt glawry in England as opposed to the US (Ramsey Reference Ramsey1892: 164)*. Thus, he implies a lowered and distinct vowel in force words in England.

Nesfield (Reference Nesfield1900) is by far the most thorough grammar with respect to the distribution of goat diphthongs in the CNG. In words like obey he admits a shortened variant of the long o, i.e. [o], or [ə]. Nesfield (Reference Nesfield1900: 280) observes that ‘a man will at one moment say o'bey and at another əbey’. However, word-final reduction to schwa in words like fellow he regards as vulgar. He further claims that the vowel in obey ‘does not, however, make a perfect pair with the o in note; for in this and other syllables that end in a consonant, the sound of o is followed by a glide or slight after-sound expressed by u’ (Nesfield Reference Nesfield1900: 280). Thereby, he describes a diphthong in words like note. The vowel quality in so, Nesfield (Reference Nesfield1900: 458) observes, is ‘in fact impure; for it not only expresses the German o, but is followed by a slight after-sound, like a faint utterance of the Eng. u in full. This after-sound is expressed by w in the case of the word know, pronounced as (nou).’ This vowel quality he also suggests for soul and know. Therefore, we could perhaps transcribe it as [oʊ ~ ou]. Nevertheless, he categorises this vowel only as partly diphthongal because not all words collated under this vowel category are always diphthongs. Indeed, he claims that vowels that end a syllable, like noble and poet, are monophthongal.Footnote 4 His choice of example words for the illustration of the vowel quality suggests, however, that this does not apply to its occurrence in open syllables of monosyllabic words such as so, know or the name of the letter O. Moreover, force words are described as having the ‘au sound’, and are thus treated as distinct from goat by Nesfield (Reference Nesfield1900: 288).

3 The distribution of /r/ variants

3.1 Historical background

One of the most striking phonological changes of the LModE period is the completion of the loss of /r/ in post-vocalic position in standard speech in England, Australia and New Zealand, where it is absent in present-day English unless it occurs between vowels. Accents of Scotland and Ireland in contrast are still rhotic today. For regional accents in mid-nineteenth-century England, Trudgill (Reference Trudgill2004a: 69–71) shows only two non-rhotic areas: (i) ‘from the North Riding of Yorkshire south through the Vale of York into north and central Lincolnshire, nearly all of Nottinghamshire, and adjacent areas of Derbyshire, Leicestershire and Staffordshire’ and (ii) ‘all of Norfolk, western Suffolk and Essex, eastern Cambridgeshire and Hertfordshire, Middlesex, and northern Surrey and Kent’. As for North America, post-vocalic /r/ absence is only attested in parts of the South and eastern New England, and in AAVE today, although there is increasing evidence of rhoticity in these varieties as well (see Labov et al. Reference Labov, Ash and Boberg2006: 47–8; Stanford Reference Stanford2020: 275–80). At the beginning of the twentieth century, Krapp (Reference Krapp1919: 21, 22) notes ‘that [ɹ] is regularly omitted by some speakers, especially in the East and South in America’. In fact, in North America this /r/-less pronunciation was taught by speech, acting and elocution schools until the end of the Second World War (Labov et al. Reference Labov, Ash and Boberg2006: 47).

At the end of the eighteenth century, Walker (Reference Walker1791: 50) still proposes two different /r/ variants: ‘rough’ and ‘smooth’ as shown in (2). According to Walker, the former is characteristic of the pronunciation in Ireland, whereas the latter is the /r/ sound of England. While he notices that in London it ‘is pronounced so much in the throat as to be little more than the middle or Italian a’ and that some speakers drop the sound of /r/ altogether, Walker proposes an allophony of ‘rough’ and ‘smooth’ variants. He advises speakers to ‘avoid a too forcible pronunciation of the r, when it ends a word, or is followed by a consonant in the same syllable’, but admits that ‘we may give as much force as we please to this letter at the beginning of a word, without producing harshness to the ear’ (Walker Reference Walker1791: 50). He thus concludes that ‘Rome, river, rage, may have the r as forcible as in Ireland; but bar, bard, card, hard, &c. must have it nearly as soft as in London.’

(2) The rough r is formed by jarring the tip of the tongue against the roof of the mouth near the foreteeth: the smooth r is a vibration of the lower part of the tongue, near the root, against the inward region of the palate, near the entrance of the throat. (Walker Reference Walker1791: 50)

From his articulatory description it looks like the ‘rough’ variant is an alveolar trill, tap or fricative as ‘jarring the tip of the tongue’ (apical) and ‘against roof of the mouth near the foreteeth’ (alveolar ridge) suggest. The meaning of his ‘smooth’ variant is trickier to unfold. It has been proposed that it refers to an approximant [ɹ] (cf. Beal Reference Beal2004a: 154). I would argue that his remark on the ‘lower part of the tongue, near the root, against the inward region of the palate near the entrance of the throat’ could indicate a bunched or velar realisation rather than a post-alveolar variant. However, if we take the /r/ in England to be ‘little more than the middle or Italian a’ and the smooth /r/ to resemble the pronunciation of England, we cannot exclude the possibility of him referring to a vocalic realisation for ‘smooth’ /r/s per se. In fact, Krapp (Reference Krapp1925: 224) suggested that Walker's ‘soft r was practically not a consonant at all’. Murray (Reference Murray1795) also embraces a distinction of ‘rough’ and ‘smooth’ /r/s but does not provide any articulatory information: ‘R has a rough sound; as in Rome, river, rage: and a smooth one; as in bard, card, regard.’ Smart (Reference Smart1836: x) in his Walker Remodelled argues for ‘a trill or trolling of the tongue against the upper gum’ and ‘a smoother sound of the letter r, which it takes at the end of syllables when another r or a vowel does not follow in the next’. Similar to Walker (Reference Walker1791: 50), Smart (Reference Smart1836: vii) and Ellis (Reference Ellis1869: 603) both observe the dropping of /r/ in London speech.

The use of trill cannot be directly translated into our understanding of the term without some caution as some might have employed the term to similarly apply to fricatives.Footnote 5 Ellis (Reference Ellis1889: 84) for instance still adds that his notation (r) is the ‘“true” trill’ which is used by Italian and Scottish speakers. Indeed, Jones (Reference Jones1964: 194) still regards fricative pronunciations as ‘[t]he most usual English r’ and so does Krapp (Reference Krapp1919: 20–2), while both mention a trill as variable pronunciation. Thus, a fricative [ɹ̝] is at least in the realm of possibility for LModE. Krapp (Reference Krapp1919: 20–2) suggests that /r/ is generally realised as a voiced alveolar fricative [ɹ̝] in initial position and as a (post-)alveolar approximant [ɹ] in final and pre-consonantal position.Footnote 6 However, ‘[a] trilled or rolled r, though not very common in American speech, is sometimes heard, especially for r between vowels, as in very, hurry, etc.’.

Earlier North American scholars such as Webster (Reference Webster1790: 15), however, state that /r/ ‘has always the same sound, as in barrel and is never silent’. Worcester (Reference Worcester1859: 18) also describes only one sound, which he terms trill and ‘is never silent’. He nonetheless remarks that ‘[t]here is a difference of opinion among orthoëpists respecting the letter r’, which is that some authors propose only one sound for /r/, whereas others suggest a twofold distinction. His list of the former includes scholars like Johnson and Sheridan. Regarding the latter, Worcester (Reference Worcester1859: 18) mentions Walker and Smart.

3.2 /r/ in the CNG

My focus in this section concerns the ideal distribution of different /r/ variants described by grammarians and the question of whether weakened variants and /r/-loss are mentioned at all in this context. This section is thus structured based on how many sounds grammarians suggest for /r/, i.e. either one sound, regardless of position, two sounds depending on position, or a description suggesting a distribution comparable to present-day non-rhotic varieties, with e.g. centring diphthongs or a complete loss of /r/ in non-prevocalic position. The last option is subsumed under the category ‘post-vocalic /r/ absent’.

There are 57 grammars in the CNG that provide information on the quality or distribution of /r/, i.e. 34 per cent of those that treat pronunciation. It is in 43 of these grammars that there is enough information to allow us to determine a distribution of /r/ variants. Twenty-six (60 per cent) of these are from North America and 17 from Britain (40 per cent). The majority, i.e. 31 grammars, propose a distribution of two different /r/ sounds. Suggesting only one sound for /r/ is the second most common strategy in the CNG (9 grammars). Grammarians that describe post-vocalic /r/-loss without any value judgements are the minority in the collection (3 grammars). In total 12 grammars provide evidence of non-rhoticity, 9 of which present negative evaluations of the feature. Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of proposed /r/ variants ‘one sound’, ‘two sounds’ and ‘post-vocalic /r/ absent’. The last category only includes neutral descriptions of /r/-lessness (see table A2 in the Appendix).

Figure 2. /r/ distribution based on region

There is no significant difference between British and North American grammars with respect to the distribution of /r/ variants. The only obvious difference is that North American grammars discuss /r/ more often, both in relation to the sum of grammars that mention /r/ and to the general number of grammars that treat pronunciation.

3.2.1 One sound

Two grammars of the ‘one sound’ category provide descriptions that allow us to deduce articulatory features of /r/. These indicate an alveolar trill (Oliver Reference Oliver1825) and a bunched approximant (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1849)*. Oliver (Reference Oliver1825: 311) proposes that ‘[t]his letter [R] is always sounded’ and elaborates that ‘it is termed the jarring letter because it has a jarring sound’. Moreover, he complains about what is likely to be a weakened variant: ‘the true sound of r is its sound in an Italian and in a Spanish mouth, which renders the jar perfectly perceptible, not degenerating into a semi-sound, the opprobrium of language’ (Oliver Reference Oliver1825: 311). While the use of words like ‘jarring’ might not have always referred to the obstruction of air (see MacMahon Reference MacMahon and Romaine1999: 488), Oliver's praise of the Italian and Spanish realisations suggests an alveolar trill or tap. Kenyon (Reference Kenyon1849: 252)* suggests a bunched approximant as for him /r/ ‘is formed by articulating the sides of the middle part of the tongue with the upper back teeth’. Furthermore, the pointing down of the tongue tip common for bunched approximants is indicated: ‘and then rolling down the end and emitting the breath through the opening thus formed’. He moreover notes trilled realisations but claims that there are few speakers skilled enough to properly pronounce this sound: ‘though the trilling sounds very well, when done by a skillful speaker, yet the number who so manage it, are too few to give authority to the practice’ (Kenyon Reference Kenyon1849 247)*. If he is referring to a trill in our modern sense, his judgement may be evidence for trills becoming less common, although they were indeed still evaluated positively.

The remaining grammarians are considerably more brief. Pinnock (Reference Pinnock1830: 19) contends that ‘R has one uniform, rough, vibrating sound, and is never silent.’ His use of the word ‘uniform’ and his claim that it ‘is never silent’ reveal that he wants speakers to use one sound, irrespective of its position. This sound is identified as ‘rough’ and ‘vibrating’ and could indicate a tap, trill or fricative or perhaps even an approximant as he does not comment further on this. He moreover evaluates its sound positively before what essentially appear to be front vowels as he adds that ‘[i]t produces a fine tone before the softer letters, as in rather, red, read, rhyme’ (Pinnock Reference Pinnock1830: 19), which might suggest that the sound he had in mind in fact was not ‘uniform’, but subject to phonetic constraints. However, he does not comment on this any further. Perhaps he had noticed weakened realisations in other contexts but was reluctant to acknowledge that. Weld (Reference Weld1848: 16)* and Munsell (Reference Munsell1851: 8)* write, ‘The following consonants have but one sound … r as in rate’ and ‘R, has but one sound, as in Rome, and is never silent’ respectively. Others are even less explicit and it is impossible to state with full certainty that they proposed only one /r/ sound in every position and every phonological environment, e.g. Goodenow (Reference Goodenow1839: 44)*, who simply states that ‘[t]he linguals are produced by the interruption of the tongue bent upwards, and are two in number, l and r, as heard in the words lull and roar’. He only provides us with an example which contains pre-vocalic and non-prevocalic contexts without further discussing the respective sounds. However, this itself could be evidence of him suggesting the same sound to be used in both positions. After criticising ‘even well-bred people’ and the ‘vulgar’ Londoners for omitting their /r/ in words like father or mother, Higginson (Reference Higginson1864: 9) contends that ‘[t]he distinct but not excessive trill of the r is a great characteristic of good articulation’. Therefore, he argues against post-vocalic /r/ omission and for a distinct pronunciation and sanctions ‘excessive’ variants. It is unclear what ‘trill’ refers to because he does not explain the sound.

Other grammarians suggest one sound but note variation. Ridpath (Reference Ridpath1881: 27)* claims that ‘[t]he consonant r has one sound, illustrated in the word ruin’. However, he adds a note, which reads ‘Some orthoëpists maintain that r has two sounds: first, the trilled r, as in rock; second, the smooth r, as in fair.’ Wells (Reference Wells1847: 38)* very briefly states that ‘R has the sound heard in rare’, which implies that for him /r/ has just one sound, regardless of whether it occurs at the beginning of the word rare or at the end. To this line, however, he appends a footnote which says, ‘The following quotations present a general view of the different opinions which exist among orthoëpists respecting this letter.’ Following this, he simply lists quotes and names of a number of other scholars such as Sheridan (Reference Sheridan1780) and Webster (Reference Webster1790) that contend that /r/ has only one sound. Furthermore, he includes quotes by scholars such as Comstock (Reference Comstock1808) and Smart (Reference Smart1841), who argue for twofold distinctions. Nevertheless, Wells (Reference Wells1847)* does not comment any further on this.

3.1.2 Two sounds

The grammars that describe two sounds mostly utilise the terminology that we find in Walker, Murray and Smart, namely a ‘rough’ sound or a ‘trill’, and some form of ‘smooth(er)’, or ‘soft(er)’ variant. These terms are used in 27 of these 31 grammars.Footnote 7 The former are proposed for initial /r/, the latter variants usually in final position. Moreover, in four cases the ‘smooth’ variant is also used after a voiceless plosive and intervocalically (Turner Reference Turner1840; Brown Reference Brown1849*; Hallock Reference Hallock1849*; Brown Reference Brown1857*). However, most grammars that fall in the ‘two sounds’ category do not provide any information on the articulation of the two variants (22 of 31 grammars). Table 2 provides a summary of articulatory properties of /r/ sounds for the remaining 9 grammars that embrace a twofold distinction. It is ordered chronologically and based on place of publication. The first sound refers to prevocalic environments, while the second sound stands for final and sometimes medial position.

Table 2. Evidence for articulatory properties of twofold /r/ distinctions

Of the British grammars, Clarke (Reference Clarke1853), Lowres (Reference Lowres1863) and Gostwick (Reference Gostwick1878) only provide implicit information on the place of articulation of /r/ as they categorise them together with other (post-)alveolar sounds. Of these, Gostwick is the only grammar from which a quality of the second sound can be derived. According to Gostwick (Reference Gostwick1878: 20–1), /r/ is a ‘dental’, i.e. a category which includes all alveolar sounds and ‘j’, in words like rose and sometimes a guttural as in work. Since his ‘gutturals’ include [k], [ɡ], [j] and [ŋ], I would argue for a velar, bunched or potentially uvular realisation. In contrast, Hort (Reference Hort1822: 20–1) provides more information on the quality and distribution of the ‘rough’ and ‘softened’ /r/: ‘R. This letter has a rough, rattling sound, which is formed by turning the tip of the tongue up towards the roof of the mouth, and breathing strongly, so as to shake the tongue, and make it vibrate … This is a little softened when the letter occurs in the end of words, before d and t.’ His mentioning of the tip of the tongue, the description of the sound as ‘rattling’ in addition to the shaking of the tongue caused by a strong breath suggests an apico-alveolar trill.

Kelke (Reference Kelke1885: 29–31, 37) classes /r/ as well as /l/ as palato-lingual trills, the former as a central and the latter as a lateral trill. Palato-linguals also include his equivalents of [s], [z], [ʃ] and [ʒ] and thus (post-)alveolar sounds. He moreover notes that it ‘would be far more natural to class them with y and w as Semi-vowels’ than ‘along with n and m as Liquids’. Both these statements suggest an understanding similar to that underlying our modern classification of [ɹ]. Hence, ‘trill’ does not seem to mean [r] or [ʀ] but potentially an approximant. Furthermore, he classes /r/ with the glides: ‘[c]ertain consonants are so termed when final and almost imperceptible … as in bar’, which implies a weakened vocalised or even zero variant. With respect to the realisation of the sound, he also seems to be influenced by the spelling as he claims the /r/ to be stronger in <rr> as in barrow than in row or hero.

Brown (Reference Brown1851: 1007)* embraces a distinction between a ‘rough or pretty strong’ and a ‘smooth’ or ‘soft’ /r/. He argues against one single sound for /r/ as he criticises Wells’ (Reference Wells1847)* ‘indecision’, which ‘forebears all recognition of this difference’ between a rough and a smooth /r/. He further complains that Wells’ example rare is unlikely to ‘exhibit twice over the rough snarl of Johnson's r’. His articulatory description suggests a sound produced with the tip of the tongue at the alveolar ridge or somewhere along the palate (Brown Reference Brown1851: 1007):

The letter R turns the tip of the tongue up against or towards the roof of the mouth, where the sound may be lengthened, roughened, trilled or quavered. Consequently, this element may, at the will of the speaker, have more or less – little or nothing, or even very much – of that peculiar roughness, jar, or whur, which is commonly said to constitute the sound.

Since it may only be turned ‘towards the roof of the mouth’ it could very well be an approximant as friction would thus be avoided. His reference to the will of the speaker could indicate idiosyncratic variation. Brown further argues against ‘the excessive trilling’ and omission of the /r/. Roughness and softness thus seem to be relational terms on a continuum with excessive trills and zero as the forbidden extremes.

Fowler's (Reference Fowler1855: 150)* /r/ in run is ‘formed by placing the tongue at such a distance from the palate as to suffer it to jar against it, the breath being propelled from the throat to the mouth’. Allowing the tongue to be in a position to ‘jar’ against the palate implies a (post-)alveolar trill, tap or fricative as for an approximant there would be no need to prepare the tongue for contact with the palate. The /r/ sound is also described as ‘canine letter, from the snarling of dogs’ by Fowler (Reference Fowler1855: 211)*, which has been interpreted as a (potentially uvular) trill in other descriptions that refer to /r/ as the sound of dogs (cf. Jones Reference Jones2006: 110, 259–60). Fowler (Reference Fowler1855: 202)* furthermore lists /r/ together with ‘k, g, l, q, and c when equivalent to k’ and terms these sounds ‘palatals’ or ‘gutturals’. This could support a uvular interpretation or imply a velar or bunched realisation. The second sound he describes as ‘vocal’ in words like dare, her, bird, for, syrtis and thus the square, nurse and north sets: ‘The vocal sound of this letter, uniting with a preceding vowel sound, modifies it.’ ‘Vocal’ is not to be confused with ‘vowel’ as vocal refers simply to voiced sounds in Fowler (Reference Fowler1855: 144)*. This description of post-vocalic /r/ could either suggest a deliberate exclusion of devoiced variants or imply a more sonorous sound than the first. This would have to be a vowel or an approximant, depending on how we interpret the first sound of /r/. It could furthermore point to rhotacised vowel, e.g. [hɚ] her. However, the complete omission of /r/ after vowels in words like card he considers an error (Fowler Reference Fowler1855: 189)*.

York (Reference York1862: 68)* embraces a distinction between a ‘trilled R’ and a ‘smooth R’. The former can be interpreted as an alveolar trill or fricative as it ‘is formed by causing the tongue to vibrate against the gums of the upper incisory teeth while the breath is propelled through the mouth’. The smooth variant is used ‘when it follows a vowel: as in air, etc.’ and is ‘made with the tip of the tongue elevated towards the center of the roof of the mouth, and propelling the breath through the mouth’. This indicates a consonant articulated further back than the first one and could thus indicate post-alveolar approximant produced with the tip up.

The /r/ that Ramsey (Reference Ramsey1892: 130)* proposes is a (post-)alveolar approximant. The sound is listed together with /j/, /l/ and /w/ in the category of semi-vowels and ‘the tongue is raised and made to vibrate with the passing vocal breath but does not touch the teeth or palate’. In initial positions it is ‘pronounced more distinctly than the medial or final’ (Ramsey Reference Ramsey1892: 168)*. Nonetheless, while he does not elaborate on this we can exclude complete absence of /r/ in final position because he is one of the fiercest opponents of non-rhoticity in the CNG (see Ramsey Reference Ramsey1892: 139, 145, 148, 169)*.

3.1.3 /r/-lessness

Concerning the absence of /r/ after vowels, the CNG contains 12 grammars in which non-rhoticity is mentioned. However, the majority of those grammars (9 out of 12) display negative evaluations of non-rhoticity. Generally, these evaluations occur in British as well as North American grammars, and the feature is often identified as ‘vulgar’, ‘corrupted’ or as typical of London. For a detailed discussion of prescriptive comments on non-rhoticity, see Wiemann (Reference Wiemann, Yáñez-Bouza, Rodríguez-Gil and Pérez-Guerraforthcoming). Nonetheless, there are three grammars that describe non-rhoticity in a neutral fashion. In Gow (Reference Gow1892: 11), we can find a description of the use of schwa as a substitute for /r/ in the letter set, linking /r/, centring diphthongs and a long nurse vowel; hence an illustration of traditional RP.

The second grammar, namely Nesfield (Reference Nesfield1900: 271), first describes what may be a trill or a fricative as he writes, ‘In sounding r the tongue, after almost touching the hard palate, is made to vibrate towards the upper gums. Hence r has been called the trilled consonant.’ Following this he adds a regional distribution to the use of this sound: ‘Except in the North, however, it is never really heard as a consonant, unless it is followed by a vowel in the same or in the next word; cf. far-ther (sounded as father), farr-ier.’ Thus, he observes that in the north of England there are speakers that still pronounce the post-vocalic /r/ and for whom farther and father are not homophonous. What he perceives as the standard, nonetheless, is the absence of /r/ unless it occurs intervocalically. The final grammar is Carpenter (Reference Carpenter1902)*. He discusses non-rhoticity but also mentions variation as he states that ‘[t]he letter r after vowels (e.g., in far) has already become silent in New York, as well as in other parts of America and England, though it is still pronounced in our western states’ (Carpenter Reference Carpenter1902: 221)*.

4 Summary and discussion

As concerns the vowel in goat, my analysis has shown that monophthongal descriptions clearly dominated in grammar writing in the nineteenth century. The grammarians’ frequent use of the term ‘improper diphthong’ and the example spellings <oa> suggest that they oriented themselves closely towards authors like Walker (Reference Walker1791) and Murray (Reference Murray1795). This does not necessarily entail that monophthongal variants were infrequent in the nineteenth century. In contrast, it is evident in Ellis, Worcester and Krapp that, at least in certain phonological environments, monophthongs were still used in the second half of the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century. While only a few grammarians show that they do not consider the term ‘improper diphthong’ appropriate to describe monophthongs, their use of the term can also be interpreted as a lack of adequate terminology to describe what they were observing. Furthermore, there are a considerable number of grammarians who consider goat and force to have the same vowel. Reasons for this could, similar to the use of the term ‘improper diphthong’ for <oa> spellings, also be that they belonged to the same category for Walker (Reference Walker1791), whose dictionary was very influential throughout the nineteenth century, as several reprints and editions show (cf. Beal Reference Beal and Cowie2009: 149, 172). The high number of monophthongal variants could also be due to a lack of awareness of diphthongisation, which Jones (Reference Jones1964: 103) still notes for words such as so or home. Grammarians might not have recognised those diphthongs with shorter offsets or a smaller qualitative difference between the two segments in contrast to diphthongs found in mouth and price words. This could furthermore explain the striking absence of prescriptive comments, except Brown's (Reference Brown1851)* rather ironic treatment of Rush (Reference Rush1827). The fact that there are no diphthongal descriptions before 1845 furthermore appears to confirm Jones’ (Reference Jones2006: 303) point that the middle of the century marks the earliest possible point for the proper establishment of diphthongal variants in prestige speech.

The few diphthongal descriptions suggest that, for nineteenth-century grammarians, the change to diphthongal variants was lexically gradual and that the most favourable phonological environments for diphthongal goat variants were open syllables as in no or know, before lateral approximants as in soul or old and before voiceless stops as in coat or note. Moreover, three of the late nineteenth-century grammars mention general diphthongisation. Since the number of grammars and example words described by them are comparatively low and do not show a consistent pattern, we can only draw limited conclusions about the distribution of diphthongs. Nonetheless, the use of diphthongal goat variants in both <o> and <ow> spellings is in line with what Ellis (Reference Ellis1874) observed towards the end of the century for Britain and conforms to Krapp's (Reference Krapp1919) observations in early twentieth-century America. A clear distinction between the goat_a and goat_b subsets, which Ellis (Reference Ellis1869) seemed to suggest, is not visible in the CNG. The only source that could be interpreted as indicating such a distinction is Speers (Reference Speers1880). The use of diphthongs in words such as boat or note is different to what we would expect based on Ellis and Krapp. The fact that diphthongal descriptions can be found in British and North American grammars is not surprising as the diphthongisation of goat words was a parallel development in both regions – at least in the sense that the outcome of this change was the presence of diphthongal variants in the majority of standard pronunciation in both localities. Based on previously available data, the increase of diphthongal descriptions towards the end of the century is to be expected as the change was likely to have been more widespread than at the beginning of the century.

As regards /r/, having two sounds is by far the most frequent description in the CNG. The relevant passages almost exclusively contain the terms ‘rough’ or ‘trill’ for the first variant and ‘soft(er)’ or ‘smooth(er)’ for the second variant. Assigning one specific variant to either of these terms is not possible due to insufficient data and also unlikely to have been the reality. The few grammars that offer some information on the articulation suggest (post-)alveolar and potentially bunched approximants as well as trills, taps or fricatives for initial /r/ and approximant, vocalic or rhotacised realisations for the second sound. A bunched approximant and an alveolar trill are each once described as the only sound for /r/. Clear and neutral descriptions indicating fully non-rhotic varieties only occur at the end of the century. Concerning the frequency of descriptions of /r/, more North American grammars provide sufficient information to derive a distribution of /r/ variants. Given the general frequency of a twofold distribution and the infrequency of proposing one sound, regardless of position, I would argue that nineteenth-century speakers in Britain and North America at least displayed two different /r/ sounds.

My data thus show monophthongal goat variants and a twofold distinction of /r/ sounds throughout the century, which could mean that they were indeed used by educated speakers. However, we have to bear in mind that the CNG is technically a ‘norm corpus’, and not a usage corpus. A comparison of my findings from the collection with a usage corpus in a similar fashion to what Anderwald (Reference Anderwald2016) did for morphosyntactic features is thus not possible. MacMahon (Reference MacMahon and Romaine1999: 376) also points out that ‘[c]onsiderable caution is needed, nevertheless, when interpreting the pronunciations given for the period from the mid-eighteenth century until the time of Alexander Ellis in the 1860s’. Therefore, conclusions about actual language use based on the CNG have to be treated with caution. This is especially due to similarities to the influential scholars of the time such as the pervasiveness of the terms ‘improper diphthong’ and ‘rough’ and ‘smooth’ or ‘soft’ to refer to goat and /r/ respectively, which could indicate strong influence from Walker (Reference Walker1791), Murray (Reference Murray1795) and others. In fact, by copying from renowned eighteenth- and nineteenth-century authors, compiling a grammar could have been a matter of a few nights’ work for many (cf. Michael Reference Michael1997: 39; Anderwald Reference Anderwald2016: 249–50). Proposing these variants could thus have been an essential part of the genre of grammar writing and could have been regarded as ‘good style’ and therefore assumed to sell better. Busse et al. (Reference Busse, Gather, Kleiber, Bös and Claridge2019: 55) show that Murray is the most frequently referenced grammarian in their collection of forty nineteenth-century grammars. This provides further evidence for the influence his grammar had. While most grammars in the CNG do not acknowledge their sources, Busse et al.'s (Reference Busse, Gather, Kleiber, Bös and Claridge2019) findings could further explain the similarity in terminology and wording to Murray. My analysis thus also shows that we have to approach nineteenth-century grammars critically if our goal is to find sources that can be regarded as direct evidence of LModE pronunciation. It is furthermore worth considering that at the same time grammars seem to have been very heterogeneous in regard to their terminology and how much space they devote to phonological variables like goat and /r/. In addition to sometimes questionable descriptions (as in Atkin Reference Atkin1845 on coat vs cat and cot), this makes it considerably harder to come up with detailed articulatory descriptions of the variants these grammarians had in mind.

Further quantitative analyses of grammarians’ terminology and their similarity to Murray, Walker and other influential scholars of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries would be fruitful. These would enable us to determine how many grammarians indeed copied from others and who copied from whom. Furthermore, given the fact that 1,936 grammars were published in the nineteenth century, I have only looked at a fraction of potential evidence. Further studies are required to establish how customary copying from influential scholars was in the nineteenth century and to evaluate the extent to which these sources generally provide enough detail to serve as historical evidence of changes in pronunciation. Another shortcoming of the present analysis is that, given the sheer number of grammars, a detailed look into individual grammarians’ biographies was not feasible.

Appendix

Table A1. Quantitative distribution goat and force

Table A2. Quantitative distribution /r/