Historically, skill formation in China has followed an unstable path. During the Cultural Revolution, educational policy focused on general education for all, while enterprises developed workplace skills through apprenticeships and training.Footnote 1 During the 1980s and 1990s, conversely, about half of upper secondary students attended a vocational middle school (VMS).Footnote 2 Competition for a place at those VMSs that offered permanent employment at state-owned enterprises (SOEs) was fierce.Footnote 3 Such advantages diminished with the SOE reforms of the late 1990s, persistent labour market informalizationFootnote 4 and premature expansion of higher education, in which well-performing VMSs were merged and upgraded to colleges.Footnote 5 In the 2000s, VMSs struggled with problems enrolling students, irrelevant practical training and high drop-out rates.Footnote 6 At the same time, college graduates’ position in the labour market became more precarious.Footnote 7 Finally, the occupational standards of the planned-economy were merged with British-style vocational qualifications, creating a system of skill certification widely perceived as ineffective.Footnote 8 Similar to the Italian system, Chinese skill formation is state-driven and densely regulated on the surface, but its underlying dynamics are market-driven due to the weakness of state intervention.Footnote 9

Market-based skill formation tends to produce inadequate transferable skills due to redistributive problems between employers and employees.Footnote 10 The manifestations of market failure include skill shortages and high turnover rates, which are well-documented in China.Footnote 11 It can cause labour productivity to stagnate, as in China in the 2010s,Footnote 12 facilitating “a low-skill equilibrium in which firms pursue capital-intensive or price-based, low-skill production strategies,”Footnote 13 and causing the economy to become stuck in the middle-income trap.Footnote 14 Public school-based vocational education (VE) systems like China's tend to be expensive, inflexible and disconnected from labour market demand, according to evidence from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.Footnote 15 But hierarchical steering through strong industrial policy can narrow the gap between VE and labour market demand in small economies, as South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore have demonstrated.Footnote 16 Conversely, coordinated market economies like Japan or Germany focus on company-based training, relying on support structures such as lifelong employment or corporatist associations – neither of which are strongly developed in China.Footnote 17 Large, heterogeneous economies like Russia, China or the USA usually rely on decentralized skill formation systems, with cooperative arrangements to narrow the gap between skill formation and labour market demand.Footnote 18

Accordingly, since the 1990s, the Chinese government has promoted cooperation between vocational schools and companiesFootnote 19 to render VE skill sets more meaningful in the context of its ineffective certificate system and overcome market failure. The 2022 Vocational Education Law legally codified “cooperation between schools and enterprises” (xiaoqi hezuo 校企合作) and the “integration of production and teaching” (chanjiao ronghe 产教融合) as guiding principles.Footnote 20 However, companies have long voiced dissatisfaction with the quality of VE graduates’ skills, labour turnover deters many companies from investing in training and cooperative projects, and two new apprenticeship programmes failed to develop adequately balanced skill sets in Guangdong province.Footnote 21 Why does cooperative education in China struggle to overcome market failure in skill formation?

This study employs the concept of positive coordinationFootnote 22 to analyse cooperation between companies and vocational colleges, which have become the backbone of Chinese VE. Section one introduces the conceptual approach and reviews the literature, and section two describes the data and methods. Section three analyses cooperation projects as negotiated agreements between vocational colleges and companies, focusing on the production of added value and embeddedness in networks that are either informal and interpersonal, or formal and inter-organizational. Section four analyses redistributive issues, most notably regarding the preferences of students/workers. Section five links the findings to the development of skill shortages and mismatches in the labour market. The underlying dynamics of cooperation are determined by the inability of negotiated agreements between colleges and companies to solve redistributive issues, most notably between students/workers and companies. Cooperation alleviates skill mismatches but remains fragile. The turnover problem persists, undermining tertiary VE's contribution to labour productivity.

Conceptual Framework and Literature Review

This section introduces the concept of positive coordination, which is part of the broader heuristic of actor-centred institutionalism – a branch of rational-choice institutionalism that focuses on interactions of composite actors in specific institutional settingsFootnote 23 – and reviews the literature to reconstruct the main actors’ preferences. The focus is on voluntary cooperation projects between vocational colleges and companies outside the state-bureaucratic system, which are the backbone of employment and productivity in China. In joint projects to facilitate the school-to-work transition, colleges and companies negotiate the skills to teach students. Regulatory context is important: the Ministry of Education (MOE) maintains a system of vocational specializations, within which vocational colleges design their curricula in a decentralized manner. This allows them to adapt their offers to local demand. Vocational curricula are simplified scientific curricula devoid of genuine vocational pedagogy, which lowers costs but raises challenges for students.Footnote 24 The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security (MOHRSS) maintains and develops a system of occupational standards inherited from the planned economy. This is the basis for occupational licences and qualification certificates akin to English National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs).Footnote 25 There are five skill levels, and a policy entitled “dual certificates” (shuang zhengshu 双证书) usually requires vocational students to obtain a certificate to graduate. But MOHRSS certificates tend to be outdated, and the aforementioned projects aim at compensating for this problem on a bilateral basis.Footnote 26

Negotiations are a double-faced mode of interactions. They have the advantage of solving coordination problems – in which actors would benefit from exchanging goods or services, thereby jointly producing added value.Footnote 27 In this study, the added value is the improved match between students’ skills and the human resource demand of the company, sector or industry. However, the division of the respective costs and benefits causes redistributive problems because one actor can improve their outcome at the expense of another.Footnote 28 For example, students do not directly participate in the negotiations, but they can decide whether to work for the training company upon graduation. Their decisions are influenced by expected career prospects and job opportunities in other companies and sectors. Other companies may offer higher salaries to benefit from skills that did not cost them anything to produce, which is a variation of the ideal-typical training dilemma in the theory of market failure.Footnote 29 If the company is unable to recruit the desired number of graduates, it may choose to downgrade or cancel cooperation with the college. Positive coordination means a mode of negotiations that solves both the coordination problems and the distributive problems involved. As section four shows, the difficulty of this process often ends up derailing projects.Footnote 30

Actor-centred institutionalism employs institutions to reduce complexity and to generalize hypotheses. Actors are typically institutionally constituted organizations or collective bodies that act boundedly rational. This section describes the core preferences of vocational colleges, companies outside the state-bureaucratic system and students. As a setting, institutions facilitate and constrain actors’ choices. Positive coordination typically requires cooperation in networks, which facilitate mutual trust and reduce transaction costs. Section three discusses both informal, interpersonal and formalized, inter-organizational networks as settings for voluntary negotiations. For comparison, cooperative projects in the state-bureaucratic system take place in an organizational setting, which facilitates compulsory negotiations and hierarchical direction involving SOEs, public service units or even joint ventures.Footnote 31 These modes of interaction are better suited to guaranteeing quality internships or certificates conveying meaningful skills and career opportunities than voluntary negotiations.

Vocational colleges

This study focuses on public vocational colleges as actors, reconstructing their preferences, while abstracting from their diversity of institutional forms and historical trajectories.Footnote 32 By 2020, the average vocational college (gaozhi zhuanke yuanxiao 高职、专科院校)Footnote 33 in China had a total revenue of 163.8 million yuan, of which fiscal support constituted 66.24 per cent and tuition fees 24.28 per cent.Footnote 34 Tuition fees are typically fixed by the local pricing authorities and differ between specializations (zhuanye 专业). Total revenue is thus influenced by the number of students on campus and the specializations offered. Overall, vocational colleges are underfunded,Footnote 35 which limits the quality of VE, though this may not apply to some elite institutions. Furthermore, the boundaries between vocational and academic higher education are hazy, given that some universities also offer three-year post-secondary curricula (Dazhuan 大专) or engage in cooperative projects, and some vocational colleges offer vocational and technical BAs.Footnote 36

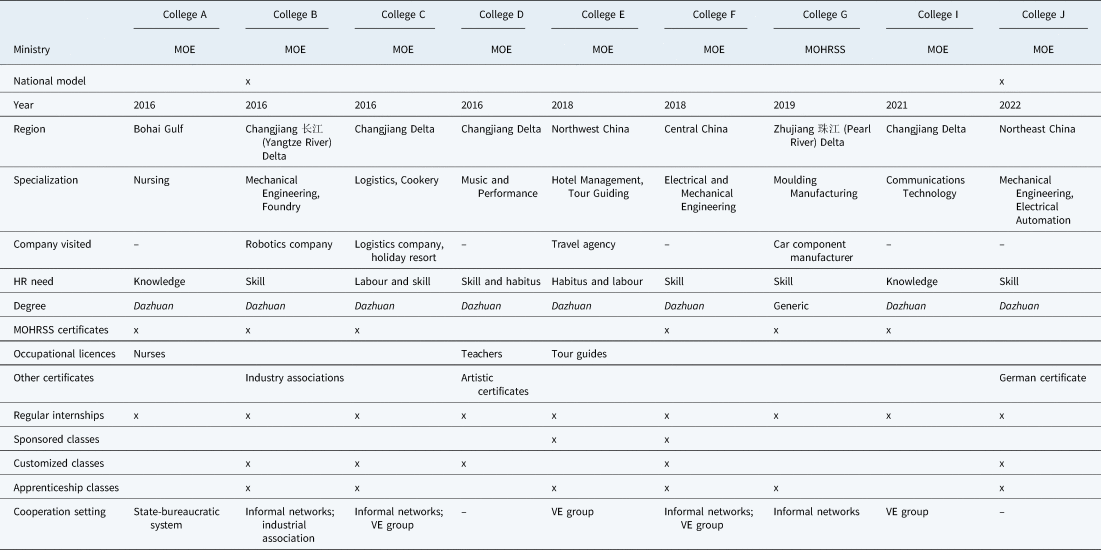

The administration of VE is decentralized. Most vocational colleges are under the jurisdiction of provincial or city governments.Footnote 37 Colleges under provincial governments tend to have a stronger disciplinary focus and recruit better-performing students.Footnote 38 Colleges’ teaching and human resources are typically overseen by subnational education departments, but they may be owned and run by different – public or private – organizations. As of 2020, 38.49 per cent of vocational colleges were run by subnational departments of education, like College E. Some 22.96 per cent were privately owned (minban 民办)Footnote 39 and only 3.20 per cent were owned by local SOEs, including Colleges B and C.Footnote 40 Colleges F, G, I and J were owned and operated by city-level departments, but these cities are comparatively wealthy, so this need not translate into severe underfunding. Additional information on the above-mentioned colleges is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Vocational Colleges, and the Main Specializations and Partner Companies

Vocational colleges are evaluated using different mechanisms. The results affect their revenues from fiscal transfers and tuition fees. Beyond the assessment of basic capacities, they are required to compile and publish educational quality reports online (see www.tech.net.cn). There are also various types of performance evaluations, as well as national and subnational programmes for model colleges.Footnote 41 A key indicator in evaluations are graduates’ employment outcomes, which influence the scope of recruitment and teachers’ salaries.Footnote 42 However, colleges largely create the data for these evaluations themselves,Footnote 43 providing substantial leeway for manipulation. Analysis is typically conducted by third parties such as McKinsey. Overall, vocational colleges all prefer to maximize revenues, and increasing enrolment serves this purpose but in turn requires high graduate employment rates.

Companies

From a rational-choice perspective, companies prefer cooperation projects to focus on company-specific skills, of which they will be the sole beneficiaries.Footnote 44 Many skills are, however, transferable because they are useful for other companies too. This is no problem under special conditions, like in economic clusters or certain large companies.Footnote 45 But generally, company investment in transferable skills carries the risk of poaching, which can deter companies from investing altogether, facilitating market failure. If companies acquire transferable skills by hiring VE graduates, VE can alleviate skill shortages for technicians, professionals and skilled workers.Footnote 46

Empirically, companies’ motivation to cooperate with vocational colleges also depends on the scope and type of human resource needs. A company with sufficiently high demand for a type of human resources may go beyond offering internships and initiate an in-depth cooperation project. He et al. distinguish four ideal-typical human resource needs, which are frequently concentrated in specific industries and sectors.Footnote 47 First, skill-dependence (jineng yilaixing 技能依赖性) means a need for practical and psychomotor abilities. It strongly encourages comprehensive cooperation, including internships, research and development, staff training and curriculum development. It is typical for cooperation in the car and machine industry and illustrated by the examples of Colleges B, D, F, G and J and their respective cooperation partners discussed below. Second, knowledge-dependence (zhishi yilaixing 知识依赖性) means the need to understand domain-specific facts, theories and rules. It weakly promotes some forms of cooperation, such as updating curricula and training teachers, as is reflected in the example of College I and its cooperation with the IT industry.

Third, habitus-dependence (suzhi yilaixing 素质依赖性) means a need for certain emotional attitudes, sets of behaviours and ways of speaking.Footnote 48 It is just an average motivator for cooperation and is characteristic of service work. At College E, tour guide apprenticeships aimed at retaining graduates in the profession by developing a more resilient habitus through early exposure to real work conditions.Footnote 49 Fourth, labour-dependence (tili yilaixing 体力依赖性) points to a significant need for manual work, typical of labour-intensive industries and services. In the hotel industry, for example, interns are often treated as cheap labour, and internships often consist of simple, tiring tasks with little job rotation.Footnote 50 The distribution of these four types of human resource needs across sectors, industries and companies strongly depends on their regimes of production.Footnote 51

Students/workers

Students/workers constitute an aggregate actor – a group of individuals with similar preferences behaving in similar ways without institutionalized coordination.Footnote 52 Economic theory assumes that students/workers prefer general and transferable skills, which give them more options in the labour market. Studies validate this assumption, while disagreeing about the reasons.Footnote 53 The Chinese government manages these preferences through a regime of educational tracking. Following nine years of compulsory schooling, students take an exam that sorts them into general and vocational upper middle schools.Footnote 54 The National College Entrance Exam (NCEE) sorts general upper middle school graduates into regular universities and vocational colleges.Footnote 55 Vocational college students usually take three-year Dazhuan programmes, which also recruit some VMS graduates with the corresponding specialization.Footnote 56 For students and their parents, VE at secondary or tertiary level is usually a second-best solution, and students with rural, migrant or working-class backgrounds are over-represented in VE.Footnote 57 Educational tracking is the primary means to adjust education to the labour market.

Methods and Data

Data was collected during multiple rounds of fieldwork in 2016, 2018 and 2019. This involved 117 interviews (single or group) and participant observation at 14 VE providers and 30 employers/companies. Additional online fieldwork was added in 2021 and 2022. The focus was on nine vocational colleges and their partner companies. The questionnaire was based on an extensive review of the Chinese literature on VE cooperation and structured in thematic, actor-specific blocks. It comprised more than 50 pages altogether. Information about students/workers was mostly collected from college and company staff. Informal interviews with students were conducted whenever possible, and most of these 20 single and group interviews were conducted in East China in 2016. Unrestricted access to campuses became more difficult in subsequent years and in the interior regions. Companies not belonging to the state-bureaucratic system were identified through contextual information and binary self-identification as public (guoyou 国有) or private (siyou 私有). The sample of colleges had above-average resource endowments. Most were administered either by provincial departments or comparatively wealthy cities. In College E in Northwest China, some buildings were in dire need of renovation, which stood in marked contrast to the modern buildings in the coastal colleges. But these differences reflect interregional gaps in socio-economic development rather than differences in administrative status. Table 1 provides an overview of the nine colleges.

Networks and Joint Production

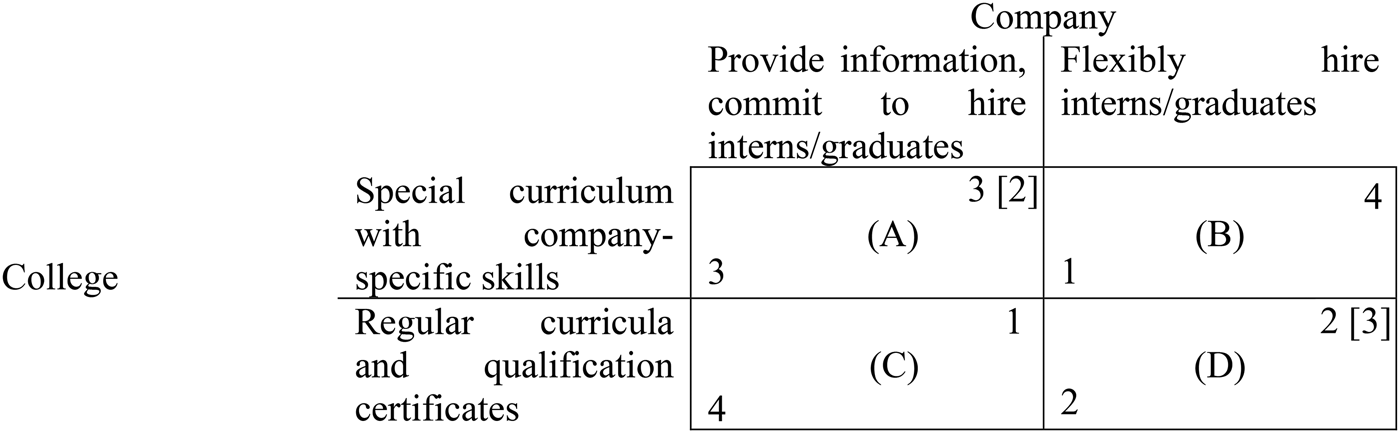

This section focuses on the joint production aspect of negotiated agreements between vocational colleges and companies, while the next section analyses the distributional aspect. Figure 1 illustrates the basic causal mechanism for joint production and the potential shifts in preferences (in square brackets) that may occur when the effects of the distributive aspect described in the next section manifest themselves. Joint production resembles a prisoner's dilemma, which can be overcome through negotiations. However, the distributive dimension may lead to changes in preferences over time, which alter the dynamics and undermine cooperation by rendering unilateral action more attractive for companies. Field D is the standard outcome, also achievable through unilateral action alone: colleges train students according to regular curricula and certificates; and companies may offer internships and hire graduates according to short-term demand.

Figure 1. The Underlying Dynamics of Cooperation

Note: Actor preferences are presented in an ordinal scale.

Joint production means a process of cooperative problem solving. It allows a college and a company to reach Field A and its added value (i.e. an improved match between students’ skills and the human resource needs of the company and its sector or industry). The full potential of cooperation includes the company providing the college with important information for updating curricula and rendering its practical skills more relevant than MOHRSS certificates; the college agreeing to create special curricula imparting company-specific skills that decrease the costs of training incurred by the company; and the company in turn agreeing to hire the special-curricula graduates. Skill- and habitus-dependence, in particular, facilitate such cooperation. For comparison, Field C includes structured nursing apprenticeships in the state-bureaucratic system.Footnote 58 Field B can include one dominant company setting standards relevant for the wider industry; or a transitory stage, in which cooperation is relaxed or collapses, as described later in the “Distributive Dimension” section. Figure 1 does not cover forced labour – involuntary internships unrelated to the specializationFootnote 59 – for this exchange of resources is similar but not skill-related. While Field D can be sustained by unilateral action, here, networks facilitate the organization of internships and job opportunities. When moving towards Field A and in-depth cooperation, networks are a crucial precondition. This section analyses positive coordination embedded in informal and formalized networks.Footnote 60

Informal, interpersonal networks

This subsection presents a case of cooperation between a logistics company and the corresponding specialization in College C. It was mainly driven by labour-dependence: processes in the company were semi-automated and frontline work was extremely deskilled. As the entrepreneur described: “If you can use a smart phone, you can work here!”Footnote 61 Interns from the college worked alongside frontline workers with lower or upper secondary school degrees. The company suffered from high turnover: in 2016, only 30 of 120 employees had been there for more than a year.Footnote 62 The entrepreneur thus sought to reduce the costs of initial training. In theory, vocational qualification certificates should provide students with transferable skills for the logistics industry. But the entrepreneur felt the certificates did not convey any meaningful practical skills, and the company therefore did not pay higher salaries to certified workers. This, in turn, made it more difficult to retain employees in the company or the industry. He explained: “If the certificate system was working, we would not have the turnover problem.”Footnote 63 The company thus needed larger numbers of interns/graduates with relevant skills to reduce the costs of initial training.

Informal networks facilitate in-depth cooperation (Field A). Here, the entrepreneur was an alumnus of College C. His company was located near the college enabling students to work there while living on campus and the professor to check on them. The company had been founded in 2013 and was one of the closest cooperation partners of the logistics specialization.

Cooperation benefited both sides. The professor sought to make practical courses more meaningful. These comprised between one-third and half of the courses in the three-year Dazhuan curriculum. The first year featured general courses, including management. In the second year, more specific courses dominated the curriculum, such as storage and transport management, or logistic information systems and applications. The fifth semester featured specific and supplementary courses, including corporate culture and strategic management. In the sixth semester, the students completed an internship at a company. Their thesis was usually the internship report, in which they described practical problems and proposed solutions. For the professor, cooperation involved visiting the company to check on interns and talk to staff. This was helpful in assessing which parts of the specific courses and practical training were most relevant and what content might be missing or outdated. Cooperation thus provided the college with crucial information, internship placements and employment for graduates.Footnote 64

The company benefited from the creation of a special curriculum by the college. It was organized as a customized class (dingdan ban 订单班).Footnote 65 The Logistics School had between 90 and 120 students per year, who were then separated in the third year: some 30 students would not follow the regular curriculum but attend either customized classes or the new Modern Apprenticeship (xiandai xuetuzhi 现代学徒制) class, which had places for ten students. Boundaries were hazy between these two types of class, for which there were no detailed central regulations. The students began working for the assigned company in their fifth semester, which combined work and online study. The skills the entrepreneur had negotiated to be included in the curriculum were mostly company-specific, which lowered the costs of initial training. He expressed satisfaction with the project.Footnote 66

Formalized, inter-organizational networks

There has been a trend towards formalized, inter-organizational networks during the past two decades, which are usually called VE groups (zhiye jiaoyu jituan 职业教育集团).Footnote 67 Compared to interpersonal networks, VE groups can reduce the transaction costs of cooperation and hiring between numerous spatially distant actors, enable studies on labour market demand and train numerous graduates with standardized skill sets.Footnote 68 But they are neither sufficient nor necessary preconditions for in-depth cooperation projects. Most VE groups are weakly institutionalized: few have their own staff and many lack a website or have no company members at all.Footnote 69 The HR staff of a partner company of College C's cookery specialization were not even aware that the company was a member of the college's VE group.Footnote 70 A groups’ effectiveness depends on synergies between participants’ preferences. For example, College B – a national model college – saw little added value in a VE group.Footnote 71 Groups created only at the request of the government often remain inactive: the main activity of College F's group for example was an annual meeting.Footnote 72

Groups provide advantages for the labour- and habitus-dependent tourism industry. The tourism VE group at College E in Northwest China illustrates this point. The group was created as part of the city government's strategy of tourism-based development. However, the city was only a minor tourist attraction, and local hotels did not have the capacity to hire large numbers of interns. Therefore, the Tourism School cultivated cooperative relations in coastal provinces, where the low-wage, labour-intensive hotel business had run into severe human resource problems. Mid-range and top-end hotels searched large cohorts of interns to replace regular staff, and thus cooperated with vocational colleges in Central and Western China.Footnote 73 The secretary of the VE group described the formalized network as a crucial platform to maintain interregional cooperation. Its so-called sponsored classes (guanming ban 冠名班)Footnote 74 reduced the duration of initial training in some hotels from one month to one week. She also indicated, however, that agreements in the VE group were not legally binding, that cooperation remained superficial and that holding partner companies accountable was difficult.Footnote 75

The Distributive Dimension

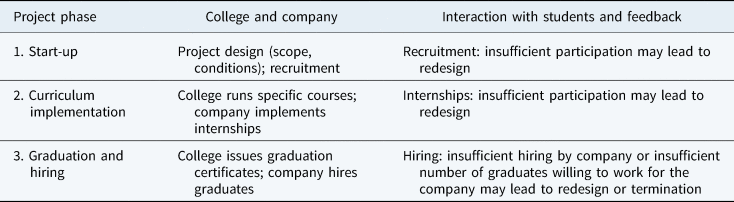

Positive coordination is challenging because it must simultaneously address aspects of production and of distribution. Cooperative projects improve the match between students’ skills and the company's human resource needs. But redistributive problems arise concerning how to divide the costs and benefits of this added value between the company and its (potential future) employees. Graduates expect privileged remuneration and career prospects as a reward for their investment in company-specific skills, whereas the company prioritizes recovering the costs of training and making a profit. Empirically, these redistributive problems can manifest themselves in different phases of customized class and apprenticeship projects, as Table 2 illustrates. First, the college is expected to provide a suitable number of recruits, but students may not want to invest in company-specific skills. Students also often change their minds in the course of the project and refuse to work for the training company upon graduation. A competitor might then benefit from the transferable skills the training company helped create and reward the opportunistic graduate accordingly. These and other problems create feedback loops that can lead to changes in programme design, or even programme termination.

Table 2. Process Model of Collaboration Projects

The regulatory standards governing these relationships are partial and ambiguous. The MOE's regulation of internships in schools and colleges under its jurisdiction requires the actors to sign internship agreements specifying the basic internship conditions.Footnote 76 Colleges normally preselect internship companies, and internships are often distributed through career fairs. Students who want to pick a different employer need to file an application with the college.Footnote 77 The new Vocational Education Law allows colleges to make a profit from cooperation and to use part of this for staff salaries and bonuses.Footnote 78 Colleges may also retain part of students’ salaries for internships or post-graduation employment organized through its networks.Footnote 79 Customized classes and apprenticeships lack detailed and binding regulation. Apprentices should sign a labour contract (laodong hetong 劳动合同) with the company including social insurance coverage, as was reported at College G for example.Footnote 80 But most companies hire interns as quasi-employees (zhun yuangong 准员工) from the college, often only with commercial accident insurance.Footnote 81 This still fulfils the basic legal requirements for an employment relationship (laodong guanxi 劳动关系).Footnote 82 So, in-depth cooperation projects’ curricula and contracts partially operate in a regulatory void. They try to prestructure the school-to-work transition, but contracts may prove incomplete and unenforceable if distributive problems arise. This can undermine network-based cooperation, as the following subsections describe.

Phase 1: Recruiting students

A student's decision to join a special programme has distributive consequences, as special curricula tie them to a specific company and may make them less competitive in the labour market. A vice-director at College J highlighted the importance of perceived career opportunities for students’ readiness to join a programme, pointing to the high attractiveness of apprenticeships with a German automotive and aeronautics manufacturer.Footnote 83 Furthermore, the timing of recruitment matters: the attractive German company managed to hire students for three-year apprenticeships when they enrolled at the college. The professor of logistics saw recruitment during the second year produce more motivated students.Footnote 84 Conversely, staff at College F reported problems with company-dominated recruitment of apprentices prior to enrolment as students were still preparing for the NCEE and not looking for jobs.Footnote 85 Timing and attractiveness influence whether students have a genuine interest in the programme and the company.

However, students find many programmes unattractive.Footnote 86 If the number of candidates is insufficient, a feedback loop may motivate the company to improve its offers. For example, the mechanical engineering specialization at College B ran customized classes with a turbine manufacturer. Only some of the students could expect to be hired upon graduation, creating uncertainty about career prospects. Students’ tuition fees were waived as an incentive, which is a common way for companies to improve programme attractiveness.Footnote 87 A student of numerical control at College B also hinted that there had been coercive recruitment for customized classes in that specialization with companies in a different region.Footnote 88 A complementary strategy was to recruit students from rural and poor backgrounds, who have lower expectations than urban youth from East China. Recruits for the New Apprenticeship Programme (xinxing xuetuzhi 新型学徒制) between a car component manufacturer and College G in Guangdong came exclusively from poor areas, some as far away as Shaanxi province.Footnote 89

Phases 2 and 3: Hiring, turnover and downgrading projects

Employment upon graduation is the riskiest stage of positive coordination for the company. Students cease to be answerable to the college and could refuse to stay with the company or be poached after hiring. The resulting feedback loop can lead the company to redesign or terminate the programme. Students’ readiness to work for the company or in their fields of specialization often declines during their final internships.Footnote 90 A crucial problem is the distinction between the professional status of Dazhuan graduates and that of the middle school graduates and migrant workers they work with during the internship.Footnote 91 Attractive career opportunities like a potential rise to middle management are thus important to motivate Dazhuan graduates to do frontline work. At the car component manufacturer cooperating with College G, graduates should receive a higher initial salary than regular workers and retain an advantage throughout their career.Footnote 92 Providing such incentives may impose additional costs on the company.

A company investing in customized or apprenticeship classes must have the first choice in recruitment,Footnote 93 especially in expensive, skill-dependent projects. Here internship agreements typically specify a minimum period of service with the company upon graduation, and students who violate the agreement are supposed to compensate the company for training and support expenditures.Footnote 94 Conversely, in the labour-dependent logistics project, the entrepreneur also described problems with retaining graduates. But here, students who signed a supplementary agreement to work for the company upon graduation merely had the incentive of accommodation in the company dormitories during their internships.Footnote 95 Ultimately, the German company aborted the project with College J in the fourth year due to high training costs and labour turnover.Footnote 96 This raises questions regarding the effectiveness of the aforementioned fines.

Finally, skill certifications affect the school-to-work transition. Both the car component manufacturer in the Zhujiang Delta and the German company working with College J used German standards for their training programme. Apprentices at College J received a regular Dazhuan in Mechanical Engineering or Electrical Automation and a German skill certification. Due to the dual curriculum, their workload was substantially higher than that of regular Dazhuan students. Conversely, College G apprentices received MOHRSS certificates in Moulding at the third level (gaoji 高级) as their main graduation qualification.Footnote 97 At College B, such qualifications were acquired alongside the regular curriculum and not considered a significant challenge.Footnote 98 Here, the certificates did not represent the full curriculum but merely the students’ preferred special field.Footnote 99 Accordingly, at the partner company of College G, a Dazhuan graduate in Mechanical Engineering could be hired for moulding, as well as various other positions, but would need more initial training than the apprentices.Footnote 100 At College G, the MOHRSS certificates helped consolidate apprenticeships because they only partially certified the skills acquired and thus made it harder for students to change jobs upon graduation.Footnote 101 In 2019, the entire first cohort of 29 apprentices became employees of the company.Footnote 102

Downgrading or abandoning projects could result from opportunistic behaviour by students/graduates as well as companies. Inability to hire graduates as expected frustrates training companies; and students and colleges are frustrated if the company changes its original hiring plans due to worsening business conditions and/or failure to accurately forecast human resource demand.Footnote 103 Hiring issues frequently led to the downgrading of cooperation: from structured three-year apprenticeships to short and flexible customized classes at College J; from customized classes to sponsored classes with less clear expectations about hiring at College F; or to the company merely providing curricula for practical training and support with curriculum upgrading in knowledge-dependent cooperation at College I.Footnote 104 So, the driving forces of market failure result in a relaxation or breakdown of cooperation projects in different ways.

Skill Shortages and Skill Mismatches

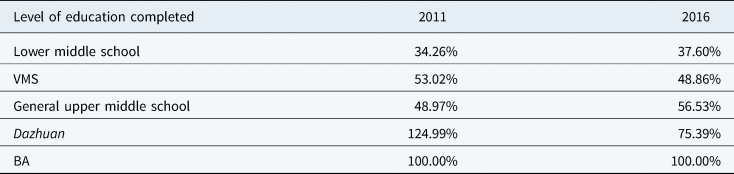

This section returns to a macro-perspective on China's education and skill formation. It uses nationally representative survey data to assess the development and intensity of skill shortages and mismatches during the period of observation and how they relate to collaborative projects. As noted above, educational tracking is the primary policy tool for adjusting educational output to labour market demand. Wage differentialsFootnote 105 provide a crude but effective tool to evaluate this coordination and detect skill shortages. Table 3 shows wage differentials for 2011 and 2016. First, for higher education, there was a shortage of Dazhuan graduates around 2011, which is reflected in their higher average income relative to Bachelor's graduates. This shortage was resolved by 2016. Second, for secondary education, there was a shortage of vocational graduates in 2011, which had eased somewhat by 2016. Overall, the wage differentials point to improved coordination between education and the labour market.

Table 3. Wage Differentials for General and Vocational Education

Note: Figures represent annual work income and are weighted.

Source: China General Social Survey (CGSS) 2012 and 2017.

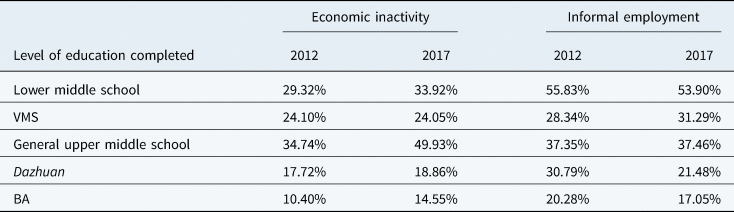

Table 4 presents complementary figures for economic inactivity – an indicator for unemployment – and informal employment of working age individuals in 2012 and 2017. Economic inactivity was higher among Dazhuan graduates than BA graduates in both years and increased over time for both groups. The differences between both groups had narrowed by 2017, when 14.55 per cent of BA graduates and 18.86 per cent of Dazhuan graduates remained economically inactive. Informal employment displays similar features, but overall levels for tertiary graduates decreased rather than increased. For both indicators, students with a higher education fared better than those with secondary education. However, VMS graduates outperformed regular middle school graduates, pointing to persisting skill shortages. Overall, educational tracking appeared more effective at tertiary level than at secondary level.

Table 4. Economic Inactivity and Informal Employment at Working Age by Educational Level

Note: Figures are weighted. Working age was defined as 15–64 years old. Informal employment was measured as the share of employees without a labour contract at each educational level.

Source: CGSS 2012 and 2017.

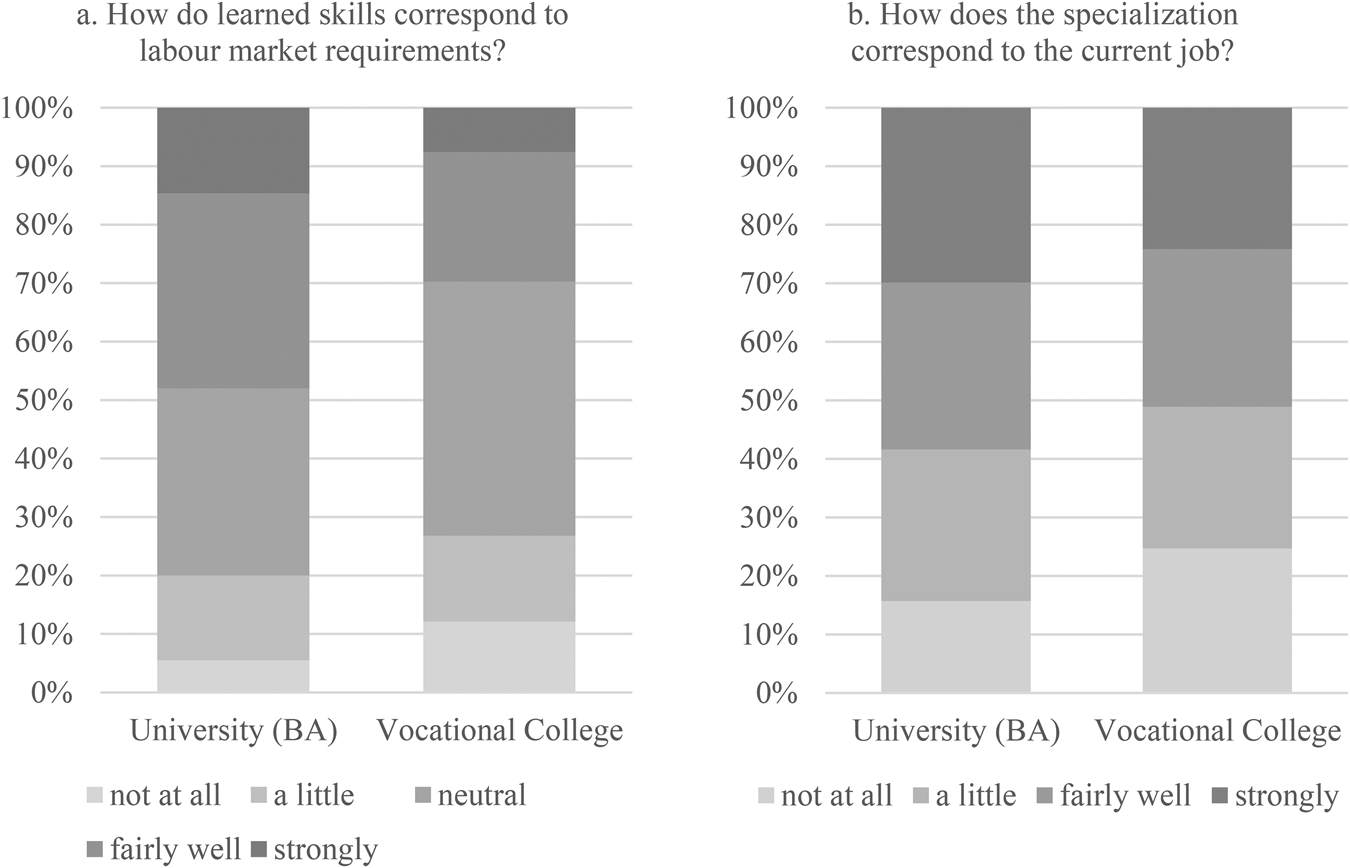

However, more fine-grained data points to massive skill mismatches, especially for Dazhuan graduates. As Figure 2a illustrates, Dazhuan graduates perceive a stronger mismatch between the skills they are taught and those in demand in the labour market. Less than one in three find them to correspond fully or fairly well. Such mismatches are inherent to school-based VE in generalFootnote 106 and are exacerbated in China by the underfunding of VE. Cooperation projects improve the figures for Dazhuan graduates by increasing the flow of information between companies and colleges and facilitating the updating of curricula. For students attending customized and apprenticeship classes, the effect depends on the hiring outcomes discussed above.

Figure 2. Higher Education Skill Mismatches in 2020

Source: Panel Study of Chinese University Students (PSCUS), as published in: Li, Chen and Wang 2022, 243f

Furthermore, as Figure 2b illustrates, the degree of correspondence between employment and training is lower for Dazhuan than for BA graduates, indicating more widespread underemployment. This mismatch is connected to turnover: within six months of graduation, 21.4 per cent of graduates switch jobs, of which 90 per cent are Dazhuan graduates.Footnote 107 As noted above, many workplaces lack distinction for Dazhuan as an educational level, and graduates working in production alongside migrant workers often get demotivated. But switching jobs during the first or second year after graduation can hinder long-term processes of skill development, which decreases VE's potential contribution to improving labour productivity. This contribution often disappears when graduates switch sectors.

Customized and apprenticeship classes should improve matching. First, the selection process helps identify students intending to work in a job that corresponds to their specialization. Second, the narrow curricula limit students’ ability to switch to other corresponding jobs. These mechanisms should reduce within-sector turnover somewhat but not necessarily turnover across sectors.

Conclusion

China tries to overcome market failure in skill formation through state intervention, with mixed results. During the period of observation, educational tracking prevented an oversupply of tertiary and general education, although there were shortages of VMS graduates. However, underfunding of vocational schools and colleges undermined the quality of VE. Moreover, public vocational qualification certificates failed to convey skills that are meaningful outside the state-bureaucratic system, resulting in a lack of incentives for employees to engage in coherent skill development and not to switch jobs across sectors and industries. As a result, despite de jure public provision of VE and dense regulation, market dynamics de facto dominate skill formation and create a lack of relevant transferable skills and high turnover rates.

A core policy to counter these dynamics is local collaborative projects within networks of vocational colleges and companies, which often take the form of customized classes and apprenticeships. Building up on previous anthropological studies and conventional policy analyses,Footnote 108 this study adopted a more structuralist collective-action perspective on those collaborative projects. They involve a negotiated mix of transferable and company-specific skills that improve the match between students’ skills and the training company's human resource needs. They facilitate graduate employment, lower the company's initial training costs and create incentives for graduates to remain with the company, thus easing the turnover problem.

Collaborative projects alleviate some symptoms of market failure but are insufficient to tackle the root causes: conflicting preferences between companies and their (future) employees regarding how to distribute the costs and benefits of training. Collaborative projects provide win-win solutions for companies and colleges, which partly depend on colleges’ hierarchical authority over students. Students may refuse to join the programmes or complete their internships, but they can be coerced to some extent. Upon graduation, however, they may choose to monetize their skills with a competing company or pursue work unrelated to their training, a practice the ineffective certificate system fails to restrain. Many projects thus try to prestructure the school-to-work transition, for example by only recruiting students from poor areas and demanding compensation for training costs from those not working for the training company for a minimum duration. However, the regulation of such projects is only partial and ambiguous, which may render some measures hard to enforce. Ultimately, many cooperation projects are unstable and fail to institutionalize the school-to-work transition in a de facto market-driven system.

Under the status quo, the dynamics of market failure in skill formation will continue to undermine VE's contribution to labour productivity in the 21st century. They will slow the progress towards a high-income society and polarize the distribution of skills and incomes. Overcoming these problems requires compulsory negotiations between business and sectoral associations, labour unions and the relevant bureaucracies. They would produce meaningful skill certification and link skill levels to salaries, thus providing incentives for employees to develop coherent skill sets and for employers to train employees.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Projektnummer 374666841 – SFB 1342.

Competing interests

None.

Appendix: List of interviews

• Interview 20160908, with the head of College A's School of Nursing.

• Interview 20160913, with senior faculty and administrative staff from College B and D.

• Interview 20160914a, with faculty and administrative staff of the School of Cookery at College C.

• Interview 20160914b, with a coordinator for college–enterprise relations at College B.

• Informal interview 20160917, with a student of numerical control at College B.

• Interview 20160921a, with a professor of logistics at College C.

• Interview 20160921b, with human resources staff at a robotics company in the Changjiang Delta.

• Interview 20160922a, with an entrepreneur in the logistics sector in the Changjiang Delta.

• Interview 20160922b, with a human resources manager in a hotel resort in the Changjiang Delta.

• Informal interview 20160923, with a piano student at College B.

• Informal interview 20160925, with a cookery student at College C.

• Interview 20180904, with a dual teacher of the School of Tourism at College E.

• Interview 20180905, with faculty and administrative staff of the School of Tourism at College E.

• Interview 20180906, with a dual teacher of the School of Tourism at College E.

• Interview 20180911, with a professor in Beijing.

• Interview 20181203, with senior faculty and administrative staff at College F.

• Interview 20181207, with the director of the School of Electrical and Mechanical Engineering at College F.

• Interview 20190912, with an expert on skill certification and the logistics sector in the Zhujiang Delta.

• Interview 20190917, with a teacher at College G.

• Interview 20190918, with a representative of a supplying company in the car industry in the Zhujiang Delta.

• Online interview 20210616, with two professors at College I.

• Online interview 20220311, with the vice-director of College J.

Armin MÜLLER is a post-doctoral researcher at Constructor University, Bremen, Germany, and principal investigator in the project “Development Dynamics of Chinese Social Policy” at the Collaborative Research Centre 1342 of the German Research Foundation (DFG) “Global Dynamics of Social Policy” (http://www.socialpolicydynamics.de/index_en.html). He formerly worked at Georg-August University Göttingen, Germany. His research focuses on social protection and the healthcare system in the People's Republic of China, as well as vocational education and migration. He wrote his PhD about China's rural health insurance at the University of Duisburg-Essen and spent one semester with the Transnational Studies Initiative at Harvard University studying transnational forms of social security.