Introduction

Striving to find meaning in life can be classified as a resource, which helps one cope with various events in life. For advanced cancer patients, meaning is a primary motivational force and a critical factor in their psychosocial adjustment to the threat of cancer; thus, meaning-based coping is recognized as a possible mechanism by which dignity-related distress can be addressed (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Cohen and Edgar2004). Those who self-report greater meaning had higher sense of dignity and less distress despite the uncertain and unpredictable nature of cancer (Henry et al. Reference Henry, Cohen and Lee2010). Therefore, it is essential for healthcare providers to address the meaning in life while providing dignity-conserving care for advanced cancer patients.

Dignity therapy (DT) as a brief, empirical-based psychotherapy can elicit responses that embrace the meaning of life, thus supporting patients to open a dialogue centered on meaning-making (Bluck et al. Reference Bluck, Mroz and Wilkie2022). In DT, patients are guided by trained therapists to reflect on their life experiences, affirm core values, reinterpret their diagnosis by contextualizing their illness within their larger life story, and leave something such as lessons, suggestions and wishes for others who will outlive them, thus constructing the meaning in life (Hack et al. Reference Hack, McClement and Chochinov2010). These conversations are tape-recorded, transcribed, and edited into a generativity document, which could be given to the patients to be bequeathed to their families as a memoir (Chochinov et al. Reference Chochinov, Kristjanson and Breitbart2011), thus making meaning through generativity. DT has been implemented to advanced cancer patients with good acceptability and high satisfaction and has proven to be effective to enhance the sense of meaning and dignity of patients (Li et al. Reference Li, Li and Hou2020; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Chow and Liu2019).

Several studies have examined the DT narration of patients by analyzing the contents of generativity documents from newly diagnosed advanced cancer outpatients, hospitalized terminal patients, hospice patients in a community setting, and patients with early-stage dementia to better understand patients and provide individualized care for them. These studies identified the common topics discussed by patients during DT, such as family, significant events, remarkable moments, acknowledgments, forgiveness and resolution, reflection on life, existentialism of life, messages left to others, hopes, and dreams (Dose and Rhudy Reference Dose and Rhudy2018; Hack et al. Reference Hack, McClement and Chochinov2010; Johnston et al. Reference Johnston, Lawton and Pringle2017; Julião et al. Reference Julião, Sobral and Johnston2022; Montross et al. Reference Montross, Winters and Irwin2011). Another study by Tait et al. (Reference Tait, Schryer and McDougall2011) analyzed narratives emerging in DT and showed that DT provided a time-oriented template assisting terminal patients in generating evaluation, transition, and legacy narratives. Considering the vital role of meaning-making in DT, Buonaccorso et al. (Reference Buonaccorso, Tanzi and De Panfilis2021) explored the answers of the last two DT questions salient to generativity and found that the meaning of cancer patients concerned their present life and clinical conditions, thoughts/actions toward the self and significant others. However, few studies have comprehensively examined aspects of life meaning constructed from the whole narrative process of DT.

Rooted in Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, the traditional Chinese culture has certain uniqueness compared with the western culture, which may influence the DT implementation and the generativity needs of Chinese patients. For example, patients put their family first in their life, emphasize on collectivism, and view the consummation of morality as a lifelong pursuit. Based on this, we developed a culturally sensitive family-based DT in China (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Guo and Geng2022). In order to integrate the novel psychological intervention into routine cancer care earlier, we implemented it to advanced cancer patients receiving chemotherapy beyond the end-of-life stage. Through DT, patients could positively cope with the loss of dignity caused by cancer and chemotherapy by constructing life meaning, thus improving the quality of life. This study aims to explore the multidimensional constructs of life meaning of advanced cancer patients receiving chemotherapy in traditional Chinese culture by examining the thematic features of their DT generativity documents from the perspective of meaning-making.

Methods

Study design

We used a qualitative approach because of the importance of capturing the voices of patients from generativity document most directly to generate a comprehensive interpretation of the phenomenon of interest. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies framework was used to report the study (Tong et al. Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007).

Setting and population

The quasi-experimental trial of DT for advanced cancer patients was conducted in a daycare center at a tertiary cancer hospital in northern China between September 2021 and April 2022. Inclusion criteria were as follows: diagnosed with advanced stage III or IV cancer, receiving chemotherapy in a daycare center, 18 years of age or older, able to speak and read Chinese, able to provide written informed consent, showing no evidence of confusion or delirium based on clinical consensus, and willing to participate in this study. The participants were recruited by H.Z. and F.L., who introduced the purpose of the study and the intervention of DT to patients. Five patients refused to participate due to physical suffering, the limitation of cultural level, or lack of interest, and finally, 27 patients participated in this study.

Data collection

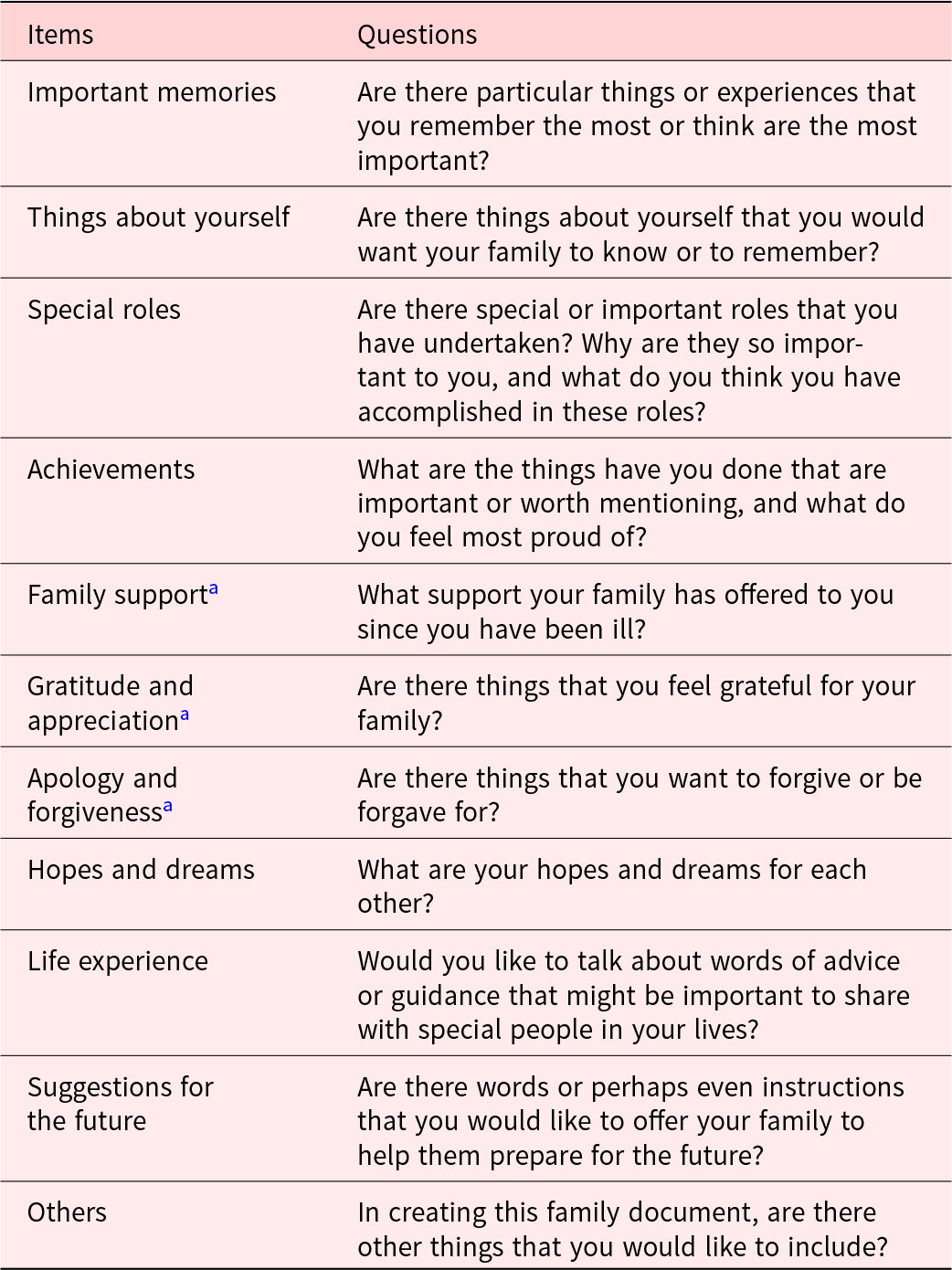

The DT interviews were conducted by J.L., X.L., and Q.G.. Q.G. was trained by Dr Chochinov who developed the DT; J.L. and X.L. have received a series of DT training offered by Q.G., including theoretical basis, interview skills, implementation procedure of DT, and practice exercises. Patients were guided to complete a recorded, face-to-face interview in a private meeting room following the DT interview protocol with culture-specific themes added to the Chochinov DT protocol (Chochinov et al. Reference Chochinov, Kristjanson and Breitbart2011), including “apology and forgiveness,” “gratitude and appreciation,” and “family support” (Table 1). The development of this protocol has been introduced in detail in another study (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Guo and Geng2022). Prior to the interview, patients completed a brief demographic questionnaire. Within 3 days after the DT interview, the recording was transcribed verbatim and paraphrased into an original edition of generativity document, which was then returned to the patient to verify, and contribute to the formulation of the final generativity document.

Table 1. DT interview protocol

a New culture-specific themes different from the original question protocol.

Data analysis

The randomly selected generativity documents were analyzed using content analysis and constant comparative techniques (Elo and Kyngäs Reference Elo and Kyngäs2008). First, two researchers independently read through the documents to obtain a sense of the whole and capture the unit of the data related to life meaning, which was then open-coded and organized into an initial set of themes. Constant comparative techniques were used to verify the distinctions between the code labels and the accuracy of fit between each unit of analysis in each theme and to determine the extent of coder agreement through regular meetings among the research team. After the analysis of the first three documents, core concepts about life meaning emerged, including the features and sources of meaning, which stimulated a return to the literature of meaning theory. The features and sources of meaning were found to be similar to the interpretation of meaning proposed by Auhagen and Holub (Reference Auhagen and Holub2006), that is, the ultimate meaning of life is to find one’ s real self and realize the purpose in life, and the sources of meaning included circumstances, things, and relationships providing meaning in peoples’ lives. These contributed to a category template for later analysis. The selected documents continued to be coded and grouped into high-order themes, which were assigned into corresponding categories constructing life meaning. Data saturation was reached after coding 24 documents.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the institutional review board at Capital Medical University (Approval No. Z2019SY038). All participants signed the informed consent form and were informed that they could refuse to participate or withdraw from the study at any time. Each participant was given a numerical identification number (e.g. [ID8]) to protect their personal information.

Results

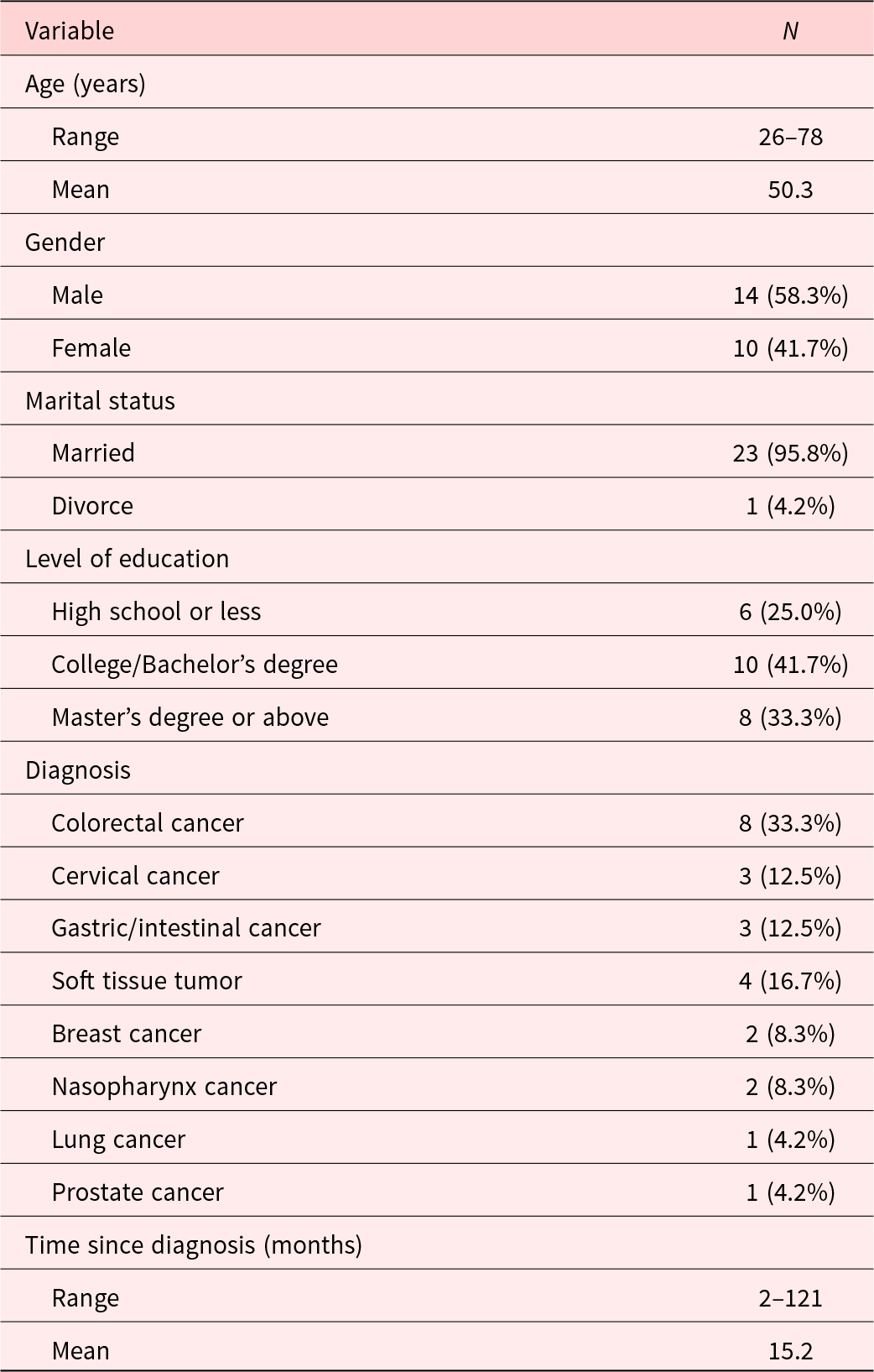

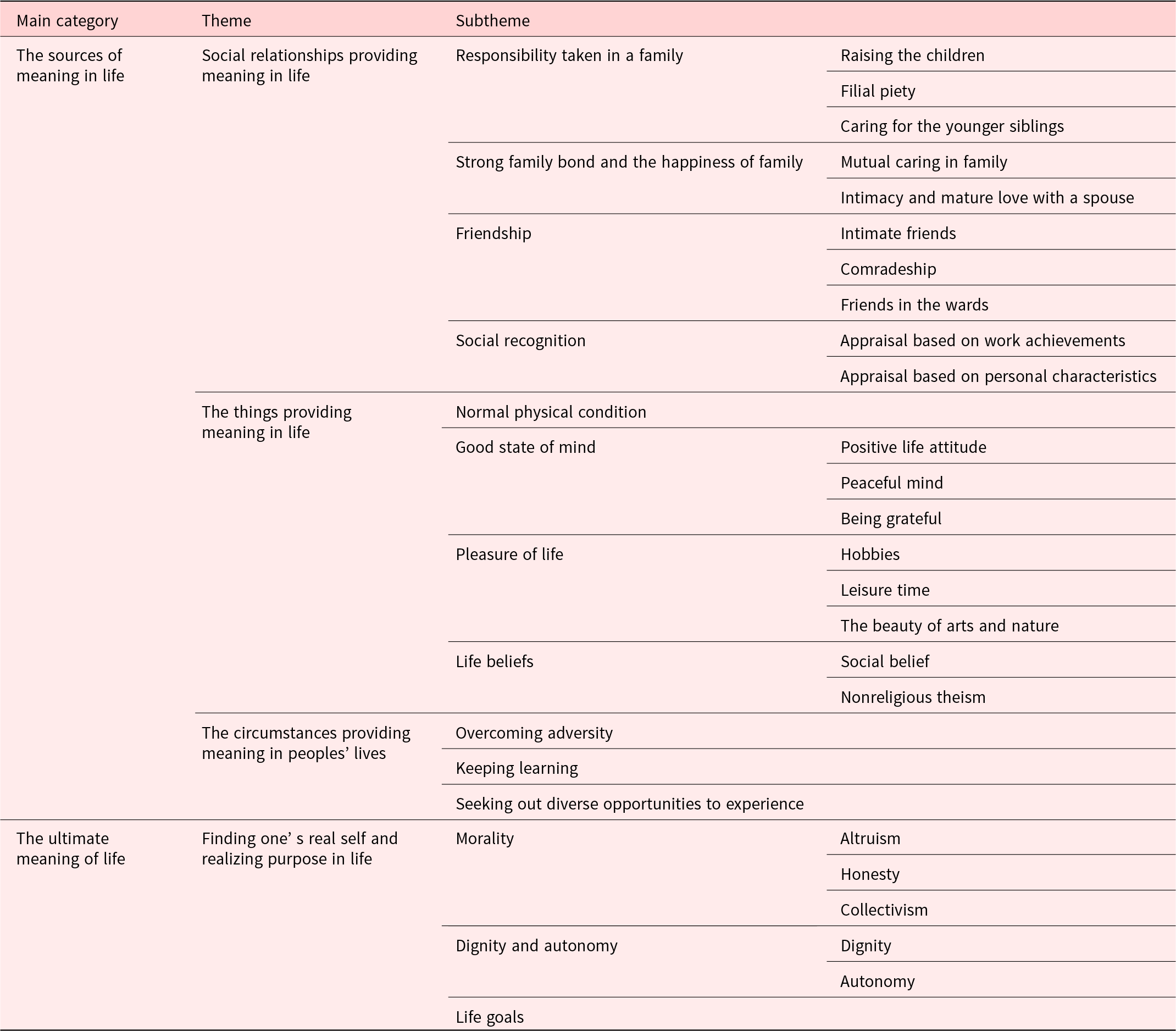

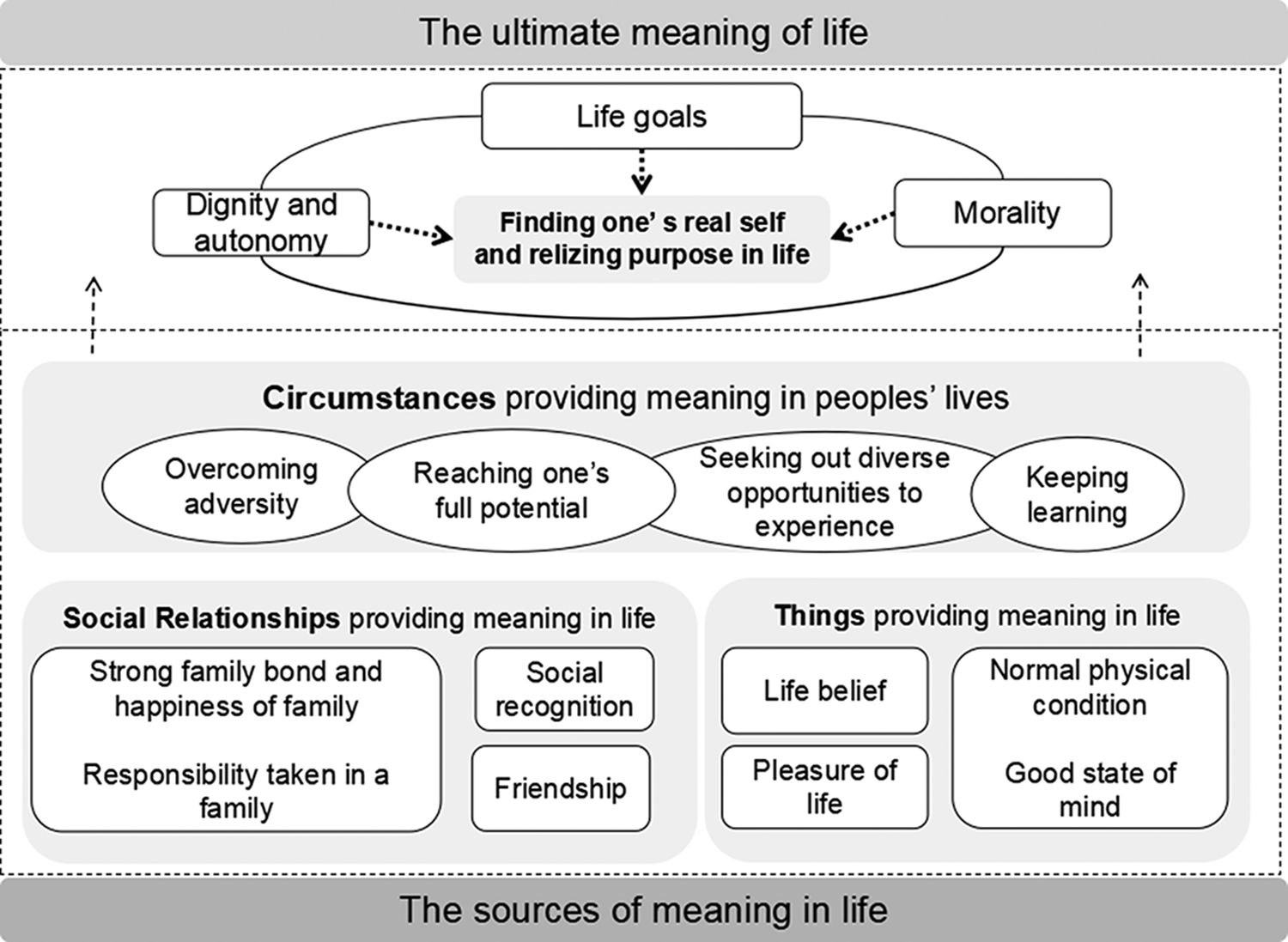

The demographic characteristics of 24 participants are shown in Table 2. Two main categories around which patients construct life meaning in DT emerged, including the sources of meaning in life and the ultimate meaning of life (Table 3). Figure 1 presents the construct of meaning for advanced cancer patients receiving chemotherapy in traditional Chinese culture. Themes are reported in detail below with associated quotes.

Table 2. Participants’ characteristics (N = 24)

Table 3. The summary of the qualitative data

Fig. 1. The construct of life meaning for advanced cancer patients receiving chemotherapy in traditional Chinese culture.

The sources of meaning in life

Patients with a broad range of life experiences had a variety of sources for meaning, which were classified into three categories in this study, including social relationships, things and circumstances providing meaning in life.

Social relationships providing meaning in life

The main source of meaning in life of patients in this study is social relationships, especially with family. Some patients also identified friends and social recognition as origins of life meaning when recalling their life experiences and achievements.

Responsibility taken in a family

Patients reported that they undertook the significant roles as parents to raise their children, as a child to be filial to their parents, and as the eldest child to care for the younger siblings in the family. They took familial responsibility as a moral request and found their life meaning through doing it.

Raising the children. “Every night my three daughters studied until midnight. I did not sleep until my children went to bed; it was meaningful for me to be dedicated to my children, and I was willing to do it.” (ID8)

Filial piety. “I think I should accompany with my parents and give them everything, as it’s my moral duty, so I bought her a lot of things, such as bracelets, rings. I lived far away from my parents, but I tried to visit them every week.” (ID22)

Caring for the younger siblings. “My father passed away early. As the eldest child in my family, I took on the responsibility to take care of the whole family. Through my efforts, I got my younger siblings out of a poor situation, which was my achievements in life.” (ID19)

Strong family bond and the happiness of family

Patients frequently mentioned their strong familial bond and the happiness of the family while sharing their important life memories. They particularly valued and appreciated the supportive family and intimate, harmonious relationship with family members, especially after the diagnosis of cancer.

Mutual caring in family. “My family care for me with love every day, even if I brought burden to them due to disease. I also understood their concerns, thus trying my best to relieve their burden.” (ID1)

Intimacy and mature love with a spouse. “I think building a family with my wife is the biggest pride in my life. We have an intimate relationship and never quarrel. I remember the time we were together with each detail.” (ID12)

Friendship

Patients mentioned that close companionship with friends in different life stages brought them a lot of power and supports to make their life meaningful. Even if they got an illness, their friends never abandoned him/her.

Intimate friends. “My greatest achievement is having several close friends. We had almost 20 years of friendship. My friends always try to help me financially and encourage me in spirit even if I cannot repay them due to illness.” (ID14)

Comradeship. “The relationship in the army is sincere. As comrades in the army, we lived and worked together almost everyday. After so many years away from the army, we still keep in touch with each other.” (ID11)

Friends in the wards. “I was sometimes touched by the sincere help from the ward mates during my stay in hospital. We often help and encourage each other due to the same condition.” (ID18)

Social recognition

Being recognized by others signifies a person’s reputation based on their work achievements and personal character, which supported them to work harder and make more meaning in life.

Appraisal based on work achievements. “My boss and colleagues are affirmative of my work, which is a kind of strength and spiritual encouragement to me. I am pleasured and feel that all my effort is meaningful.” (ID21)

Appraisal based on personal characteristics. “My friends often ask me for help when they are in a dilemma or need to make decisions. They trust my personality and ability, which keeps me making contributions for others.” (ID3)

The things providing meaning in life

Life was meaningful for many patients because of the important things in life that they owned, such as their physical and psychological well-being, life beliefs, and the pleasure of life they have enjoyed.

Normal physical condition

Patients highlighted that keeping a normal physical condition was the premise of everything learned from the diagnosis of cancer. They tried to physically perform daily activities independently, which made their life meaningful, and they guided their family to stick to healthy regimes and hoped them not go through illness.

“Nowadays, young people pay very little attention to their health. No matter what people do, they must have a healthy body first. I felt pleasured while quitting bad habits such as smoking and eating junk food to keep in a good condition, and I really hope my family to keep healthy.” (ID11)

Good state of mind

Patients described that they valued a good state of mind, which was equally important as physical health. They adjusted themselves psychologically to keep a positive life attitude and a peaceful mind, as well as be grateful for everything in life especially after being diagnosed with cancer.

Positive life attitude. “Everyone will reach the final days of life, so we should be optimistic. If I were to die at eight tomorrow morning, I would still clean up, eat breakfast and express gratitude to others at 7 a.m.” (ID19)

Peaceful mind. “We are all ordinary beings. I told myself that simple is the best and do not pursue unrealistic goals. I tried to be more peaceful after getting cancer.” (ID10)

Being grateful. “There are lots of people to be appreciated in my life. I am a person who knows how to repay kindness and I will never forget the people who have helped me throughout my life.” (ID11)

Pleasure of life

When discussing meaningful life experiences, patients shared the pleasure in life with a smile, such as their hobbies, leisure time, and the beauty of arts and nature they appreciated, which supported them to fight with cancer to experience more happiness in life.

Hobbies. “I learned the sport of bridge by myself. I have participated in various tournaments of the bridge and won many championships. I will take part in more games when I am in a better condition” (ID9)

Leisure time. “My mother often bought us fashionable clothes, and I could collect many sets of postcards of movie stars which were rare at that time. These are joys in my life and I always recall them.” (ID22)

The beauty of arts and nature. “I love to travel around the world and I have been to some countries such as Germany. When I stepped on the floor of the palace or hung out in a small town, the picturesque scenery impressed me deeply.” (ID2)

Life beliefs

Due to a variety of life experiences and worldviews, patients had different life beliefs, which were defined as the spiritual supportive source for patients in the process of meaning-making.

Social belief. “As a soldier, my belief is to put the interest of my country first. Until now, it is still one of the most significant meanings of life for me.” (ID6)

Nonreligious theism. “I believe in the existence of a supreme being, who has a plan to convey a sense of purpose in life events, so everything that happened to us was a part of the journey and in control.” (ID9)

The circumstances providing meaning in peoples’ lives

When reflecting on life achievements, patients stated that they found the meaning in life under the creation inspiring circumstances, including overcoming adversity, reaching their full potential, keeping learning, and seeking out diverse opportunities to experience. These were important ways to attain personal growth and enrich life experiences, thus making life meaningful, which extended across their lifetime.

Overcoming adversity. “When we were encountering difficulties in life, such as illness and pain, we should embrace them bravely rather than avoid them. I will keep on active treatment to fight with cancer until the final day, even if I am suffering.” (ID7)

Reaching one’s full potential. “To work hard, and to realize one’s potential is a life achievement. I do not want to waste my time, and will try to leave something valuable.” (ID21)

Keeping learning. “I think that one’s life should be a process of constant improvement. There is lots of knowledge to learn, so we should keep learning and improving ourselves. I want to keep on working even if during the treatment” (ID21)

Seeking out diverse opportunities to experience. “We need to experience more and try to broaden our horizons. Everyone is born the same, but the gap between each person is getting bigger when we grow up due to different experiences.” (ID7)

The ultimate meaning of life

Patients in this study mentioned that morality, dignity and autonomy, and their life goals contributed to their identity and life purpose, which was viewed as the ultimate meaning in life.

Morality

Possessing morality, including altruism, honesty, collectivism, and kindness, was considered a culture-specific component of life meaning, which was particularly valued by Chinese patients.

Altruism. “I think helping people is worthwhile and I have helped those in need as much as possible. I helped a girl until she graduated from college, and now I am helping two more students. All these bring me a sense of meaning.” (ID21)

Honesty. “I have done everything with a clear conscience all my life, and always say honest and sincere words, which is my life faith and duty. Now I guide my children to do the same thing.” (ID1)

Collectivism. “Everyone has different working abilities and methods, so we need to hold on collectivism to put the group interest first and play the advantages of each one, thus achieving a group success.” (ID11)

Kindness. “My grandmother always could bear hardships and were kindful. She always sympathized and helped the poor and the needy. I have learned from her and kept kindness to make life meaningful.” (ID2)

Dignity and autonomy

Some patients described living with dignity and having the right of autonomy to make their own decisions regardless of surroundings or others as significant parts of life meaning, even if they were in severe sufferings.

Dignity. “I don’t want to live a life with a low status of spirit. Everyone has different life value, but I think the most important one is dignity, and I do not want to be insulted.” (ID11)

Autonomy. “Even if in the most difficult time of life, we should make decisions depending on our own needs. Don’t be dominated or swayed by other people and surroundings around us.” (ID19)

Life goals

When reflecting on life, patients frequently mentioned that they always stuck to achieve their life goals that guided them forward and helped to construct ultimate meaning in their life.

“I have always been interested in Medicine since I was a child, and I considered studying Medicine as my life goals and I strove constantly to achieve it, which was the most important part of meaning in life.” (ID20)

Discussion

This study explored the multidimensional construct of life meaning revealed in DT generativity documents from advanced cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy in mainland China. The social relationships including family, friends, and social recognition, things including physical and psychological well-beings, life pleasure, and life belief, and creative circumstances including enriching life experiences and attaining personal development provided meaning in patients’ s life. The personal life goals, dignity and autonomy, and morality contributed to finding one’s real self and realizing purpose in life, thus achieving the ultimate meaning in life. These findings were helpful to generate a rich description for each of the various aspects of life meaning in the context of active cancer treatment, which might inform integrating dignity-conserving care based on meaning-making into comprehensive cancer care in the early stage of the cancer trajectory.

Clarifying patients’ sources of meaning in life is essential for helping them seek motivation in life and delivering meaning-based dignified care for them. Social relationship was the most significant source of meaning for advanced cancer patients revealed in generativity documents, which powerfully supported them to endure pains, fight against cancer, and strive to survive (Salamanca-Balen et al. Reference Salamanca-Balen, Merluzzi and Chen2021). Family was a reoccurring relationship, which is consistent with the findings of a study conducted in western countries (Hack et al. Reference Hack, McClement and Chochinov2010). The unconditional love from family members supported patients to maintain hope in life (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Ma and Chen2021). In turn, patients tried to support their families in a role reversal, reciprocal situation, which gives indications to the future support network of mutual caring between patient and family. Chinese patients highlighted “filial piety” for their parents in DT sessions, which means a moral duty for adult children to take good care of their parents in Confucian culture (Bedford and Yeh Reference Bedford and Yeh2019). In contrast, while talking about family in DT interviews, western patients mostly referred to children and marriage rather than parents (Julião et al. Reference Julião, Sobral and Johnston2022), which may be because the center of family is the husband–wife relationship in western society and caring for their young children is a parental obligation and morally required, but looking after aged parents is voluntary (Alavi et al. Reference Alavi, Latif and Ninggal2020). Thus, the cultural characteristic should be taken into consideration while implementing DT and delivering dignity-conserving care for Chinese cancer patients. Besides cultural influences, the differences in family-related topics in DT interviews may also vary with age groups. For example, older patients whose parents have passed away would mention their children more frequently, while younger patients might place equal emphasis on their children and parents during DT.

Among things providing meaning in life, the belief of patients and pleasure of life they experienced in daily life shaped their personalities, which might likely be overshadowed by suffering (Julião et al. Reference Julião, Sobral and Johnston2022). Therefore, knowing these things opens a door for healthcare providers to better understand patients as a whole and not solely the embodiment of their life-limiting condition, thus providing a holistic dignity-conserving care for patients. Besides, physical and psychological well-being was the basic source of meaning. Patients wished to keep in a good condition, particularly while receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy, which was viewed as the basic human needs by Maslow (Zalenski and Raspa Reference Zalenski and Raspa2006). Moreover, advanced cancer patients with a better quality of life could be helped in giving meaning to the disease through transferring the lessons learned from the diagnosis of cancer to their loved ones to fulfill the generativity needs. Therefore, it is significant for healthcare providers to help patients keep a good quality of life through assessing and controlling physical and psychological symptoms of patients timely and precisely, thus assisting them in making meaning better (Buonaccorso et al. Reference Buonaccorso, Tanzi and De Panfilis2021; Rosa et al. Reference Rosa, Chochinov and Coyle2022).

The creation inspiring circumstances also provided meaning in life, even though when patients were in sufferings, which indicates the significance of empowering cancer patients in meaning-creating efforts (Johnsen et al. Reference Johnsen, Eskildsen and Thomsen2017). For example, to help patients learn more knowledge, healthcare providers could communicate with them fully and offer sufficient information about diseases and treatments to them, as well as encourage them to involve in medical decision-making process. To enrich life experiences of patients and help them reach potentials, healthcare providers could provide more diversified, productive opportunities for cancer patients such as art therapy and horticultural therapy at the intermission of chemotherapy (Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Chen and Xie2020; Masel et al. Reference Masel, Trinczek and Adamidis2018), thus relieving their stress and enhancing sense of meaning. Notably, some advanced cancer patients in this study viewed receiving aggressive cancer treatments as overcoming adversity to construct life meaning, which also was mentioned by Liao et al. (Reference Liao, Wu and Mao2020). This view could help patients keep positive attitudes and maintain hope of life, but it might to some extent hinder early referral to palliative care, especially for Chinese patients influenced by the death-taboo culture (Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Guo and Chen2021).

The ultimate meaning involved one’ s self and purpose of life, which was the core value as a person accompanied by spiritual experience. Among the ultimate meaning identified in this study, morality of altruism, honesty, collectivism, and kindness were mentioned frequently, which was supported by the previous study showing that morality is a vital part of death with dignity for terminal patients (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Ma and Chen2021). In traditional Chinese culture, people have intrinsic meaning from taking moral behaviors and responsibilities to society, thus the priority of morality is over personal autonomy (Li Reference Li2022). Understanding the ultimate meaning of patients with cultural uniqueness is essential for helping patients maintain ego-integrity, which is the philosophical underpinning of person-centered dignified care. These also could offer insights into how to refine the protocol of DT implementation (Hack et al. Reference Hack, McClement and Chochinov2010). During DT sessions, healthcare providers could intentionally address these meanings of patients and guide them to discuss related topics, which might help to get deeper into patients’ inner feelings and bring additional benefits of therapy.

This is the first study to focus on the life meaning constructed from the whole narrative process of DT in mainland China by qualitatively analyzing the generativity documents from advanced cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. The findings of this study could help healthcare providers to fully understand the various aspects of life meaning and provide individualized, culture-specific dignified care for patients with traditional Chinese cultural backgrounds, both in China and other countries. Besides, the data were derived from the patients undergoing active cancer treatment rather than impending death, which adds more information on early integrated dignified care beyond the field of end-of-life care.

Limitations

This study also has several limitations. First, patients in this study were recruited from a tertiary cancer hospital in northern China, potentially limiting the generalizability of these findings to patients from other hospitals or from other parts of China. Besides, patients with religious beliefs were not represented in the sample; thus, how their perspectives might inform the study findings is unknown. Future study on a more diverse sample of patients would be needed to enrich the study findings.

Conclusions

This study explored the various aspects of life meaning in traditional Chinese culture revealed from the generativity documents of advanced cancer patients receiving chemotherapy in mainland China. The sources of meaning in life consisted of social relationships, things, and circumstance related to meaning-making, through which patients found their real self and realized purpose in life, including personal life goals, dignity and autonomy, and morality, thus achieving the ultimate meaning in life. These findings could provide insights into dignity-conserving care based on the meaning constructed from DT for patients with distinctive Chinese cultural characteristics and provide evidence for refining the implementation protocol of DT through intentionally addressing the ultimate meaning of patients in the therapeutic session.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to the participants in this study who generously gave their time and shared their thoughtful insights.

Authorship contributions

J.L. contributed to the investigation, data curation, data analysis, and writing original draft. H.Z. contributed to the investigation, data curation, formal analysis, and resources. L.X. contributed to the investigation and data curation. F.L. contributed to the investigation, data curation, formal analysis, and resources. W.L. contributed to the investigation, data curation, and writing – review and editing. Q.G. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, data analysis, funding acquisition, and writing – review and editing. All authors approved the final manuscript and have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content. J.L. and H.Z. are regarded as co-first authors. W.L. and Q.G. are regarded as co-corresponding authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared none.