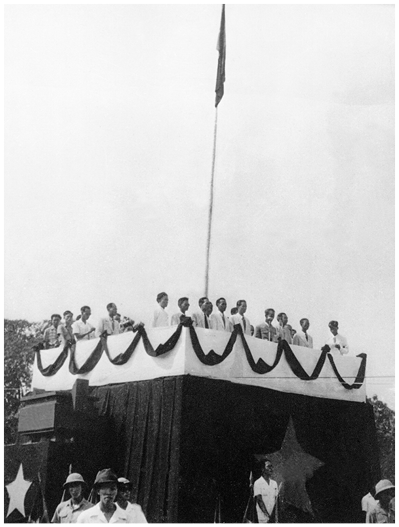

The frail-looking man who addressed the mass gathering in Hanoi on September 2, 1945 (Figure 6.1), was unknown to almost everyone present, yet his independence message made an indelible impression, and soon reverberated around the country. After vigorously denouncing eighty years of French colonial practice, Hồ Chí Minh, the president of the newly proclaimed Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN), turned his final remarks to immediate diplomatic circumstances. He announced the cancellation of all treaties signed by France that dealt with Vietnam. Then he concluded:

Vietnam has the right to enjoy liberty and independence, and in fact has become a free and independent country. The entire Vietnamese people (dân tộc) are determined to devote their physical and mental strength, to sacrifice their lives and possessions, in order to safeguard that liberty and independence.Footnote 1

Of course, Hồ Chí Minh knew that it was one thing to declare independence, quite another to gain external recognition. In his speech Hồ Chí Minh expressed hope that the Allied powers would adhere to relevant statements made at the Allied conferences at Teheran in 1943 and San Francisco in April 1945. He was concerned that Allied leaders meeting at Potsdam in late July had designated Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Chinese Army to take the Japanese surrender in Indochina north of the 16th parallel, and British forces to the south of that line. The most pressing question in early September was whether French troops would accompany either Allied contingent. General Lu Han, the Nationalist Chinese commander, proceeded to rebuff French attempts to reintroduce units that had fled to Yunnan following the March 9 Japanese coup against the French colonial administration. In Saigon, by contrast, British General Douglas Gracey employed Japanese forces together with British-Indian and some French units to drive DRVN adherents to the countryside. Popular Vietnamese euphoria gave way to fury at British actions. Cries of “Independence or Death!” echoed from south to north.

Figure 6.1 Hồ Chí Minh proclaims the independence of Vietnam in Hanoi (September 2, 1945).

At this moment we can imagine Hồ Chí Minh reflecting soberly on Vietnam’s past encounters with powerful foreign forces. Classical strategic doctrine delineated three choices: negotiate; fight; or concede defeat. Despite popular belief, Vietnam’s monarchs had usually tried negotiations first. Ngô Sĩ Liên, the famous 15th-century historian, had advised rulers first to bring “words” to imminent invaders, even to offer them precious gems and silk. If these did not succeed, then battles had to be fought, vowing to resist unto death.Footnote 2 Words had failed with the French in the 1860s and 1870s. Armed resistance collapsed a decade later. Anticolonial literati at the turn of the century grappled with this bitter chain of events.

By 1945, Hồ Chí Minh had lived through decades of war, revolution, and the failure of numerous efforts to restore international stability. The United Nations offered new hope in 1945, but only sovereign states were eligible. And with France a permanent member of the Security Council, Hồ Chí Minh probably doubted that much could be accomplished there. He clearly hoped that the United States might provide counterweight to French, British, and Chinese ambitions, but nothing learned in September offered room for optimism. In this precarious situation, the most immediate task was to build a DRVN state that could credibly promote Vietnamese independence on the global stage.Footnote 3

State Creation

The kind of state that Hồ Chí Minh and other Vietnamese elites hoped to build was one that possessed a defined territory, hard borders, a governing hierarchy, a common identity and culture, and undivided sovereignty. Interestingly, no decree signed by provisional president Hồ Chí Minh defined the territorial or maritime borders of the DRVN. Only a decree listing provinces and cities to participate in a national election offered guidance. Those units were identical to French colonial demarcations for the three regions of Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina. No DRVN claims were made on neighboring territories, nor was there any mention of possible claims by neighbors on Vietnam’s territory.

Early DRVN decrees and public pronouncements revealed a strong preference for centralized government, the result of ten centuries of monarchical rule, eighty years of French statism, and twenty years of intellectual fascination with the Soviet Union, Italy, and Germany. The capital, Hanoi, would possess a full complement of ministries, bureaus, and departments, as well as a National Assembly. Three regional committees would implement policies in the north, center, and south. Province committees would provide the linchpin between the center (trung ương) and the district and commune committees below. Soon every state document, and much citizen correspondence, possessed the heading “Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Independence, Liberty, Happiness.”

Vietnamese employees of the former colonial system were ordered to remain on the job, and the majority did so. Agents of the French Sûreté (colonial security and police service), mandarins, court clerks, and tax agents tried to make themselves scarce. Hồ Chí Minh signed more than fifty decrees in September, each one telegraphed to the newly formed regional and province committees. Message traffic from below was extensive as well. The PTT network – both staff and equipment – was perhaps France’s most valuable gift to the DRVN. The “wiring” of the colonial state more broadly had largely survived, to be used by new masters.

The DRVN’s most serious domestic challenge, indeed a test of its right to rule, was to ward off another terrible famine. In early 1945, 1 million or more people had died of starvation in Tonkin and northern Annam. In mid-August, the Red River had broken through dikes to inundate one-third of Tonkin’s summer rice crop. Efforts to transport surplus rice from Saigon northward were terminated by the British on arrival in mid-September. Fast-growing replacements (corn, yams, beans) were planted wherever possible. Distribution was supervised. About ten thousand people still died of starvation before the May 1946 rice crop was harvested, which was still fewer than those who died from cholera or typhoid fever.

The revolutionary spontaneity of August carried through in the countryside for some weeks in September. Symbols of the colonial past were trashed, landlords thrown out of their homes, village notables humiliated, alleged traitors incarcerated or killed. People celebrated Hanoi’s elimination of the hated head tax, then were upset to hear that the new government intended to collect most other colonial-era taxes. Having found the Imperial Vietnam treasury almost bare, and the Bank of Indochina still guarded by Japanese soldiers, the government mounted a series of patriotic donation campaigns. Young women proved most adept at convincing families to donate rice on a monthly basis. Cash or jewelry obtained was mostly used to purchase arms and ammunition. This left very little to pay continuing civil servants. The government urged state employees to apply for leave without pay, anticipating that many would still continue to work. Relying on a combination of family ingenuity and free food on the job, thousands of employees took this option. Particularly in the provinces, continuing participation in the administration offered some protection against revolutionary harassment. Young civil servants sought transfer to the National Guard, where their past was less likely to be challenged.

Although the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) was easily the most influential political organization in Vietnam, it did not control the DRVN civil administration, its fledgling National Guard, or even the majority of the self-proclaimed “Việt Minh” groups that had cropped up around the country. Many ICP members returning from jail or hiding found the exuberant crowds, speechmaking, media ferment, and government regulations quite disorienting. Young Việt Minh activists honored the past anticolonial efforts and personal sacrifices of ICP returnees, but often found it hard to work with them. Central party publications described an open, ideologically forthright status for the ICP. Some veterans from the 1930s assumed that the ICP would function like the French and Italian communist parties, with members seeking election to the National Assembly. Such expectations came to an abrupt halt on November 11, when Hồ Chí Minh announced the “self-dissolution” of the ICP to placate Chinese Nationalist commanders. Although this caused considerable confusion, some members probably felt more comfortable returning to clandestine practices. The police no longer pursued them, of course. Indeed, the ICP would become the only political organization permitted to communicate secretly. The party’s priority now was to gain leadership over all the Việt Minh committees. In central Vietnam this would take a year or more.

Saigon and the Mekong Delta

In Cochinchina, events unfolded quite differently. Here the Communist Party had yet to recover from severe French repression in 1940. Two different regional committees claimed leadership. Two religious movements, the Cao Đài and Hòa Hảo, had grown large and confident, partly due to Japanese protection. Following the overthrow of the French in March 1945, the Japanese had encouraged the formation of the paramilitary Vanguard Youth (Thanh niên Tiền phong). Cao Đài adepts, former colonial functionaries, monarchists, Trotskyists, and ICP members jostled for leadership of Vanguard Youth branches. ICP fortunes received a major boost when word arrived of Tokyo’s surrender and the Việt Minh takeover in Hanoi four days later. Armed Vanguard Youth units bearing Việt Minh flags soon occupied government facilities in Saigon. A huge September 2 meeting on Norodom Square, timed to coincide with Hồ Chí Minh’s independence declaration in Hanoi, descended into chaos when shots rang out from an adjacent building. Bands of Vietnamese then pursued, assaulted, and in several cases killed French civilians.

When British General Gracey arrived in Saigon on September 12, he immediately ordered his Gurkha escort to accompany a Japanese unit to evict the DRVN-affiliated Southern Provisional Executive Committee from the former governor-general’s palace. Trotskyists had already condemned the ICP for being dupes of the Allies. Now they advocated an immediate attack on the British before reinforcements arrived. The executive committee instead declared a general strike, which Gracey used to justify proclaiming martial law. On September 22, Gracey rearmed previously interned French soldiers and civilians, who proceeded to rampage through Saigon. Vietnamese bands struck back ruthlessly the next day, killing more than 150 French civilians, including women and children. Meanwhile, armed ICP squads began to track down and kill a number of Fourth International/Trotskyist adherents. No leader – British, French, or Vietnamese – was in a position to reverse the cycle of bloodshed and widespread torching of property. On October 3, the French cruiser Triomphant debarked the first thousand-man, battle-hardened army contingent from the metropole.

In the Mekong Delta in August, the alternative ICP “Liberation” Regional Committee had organized rallies and takeovers at Mỹ Tho and several other towns. Cao Đài and Vanguard Youth groups took control elsewhere. The most serious domestic confrontation anywhere in Vietnam began on September 8, when ICP adherents killed or wounded several hundred Hòa Hảo members marching into Cần Thơ. Hòa Hảo devotees were quick to exact revenge, killing a hundred or more ICP and Vanguard Youth members. Elsewhere, the substantial Khmer minority mounted demonstrations in favor of national independence for Cambodia. Mobs of ethnic Vietnamese (Kinh) later attacked a number of Khmer villages in what amounted to pogroms.

Given pre-existing political, religious, and ethnic animosities in the Mekong Delta, it seems unlikely that anyone could have prevented these serious outbreaks of domestic violence following the Japanese surrender. Attempts by the Southern Region Executive Committee to build a grand coalition were bound to fail. There was almost no awareness of what the Việt Minh represented beyond the flag and some slogans upholding DRVN independence and the territorial unity of Vietnam from the Chinese frontier to the Cà Mau peninsula.

Word of the September 22 French rampage in Saigon and Vietnamese retaliations the following day spread quickly through the country. Henceforth the date “September 23” was a marker of national resistance. Nonetheless, Hồ Chí Minh instructed the Southern Region Executive Committee to negotiate an immediate ceasefire with General Gracey. Several meetings did take place, and shooting dropped off, but during those eight days British and French forces went from a vulnerable 1,500 men up to more than 12,000 troops equipped with artillery, armored cars, and trucks. Gracey gave the Vietnamese twenty-four hours to lay down arms, but serious fighting soon resumed. Separate bands of Cao Đài, former Garde Indochinois soldiers, and Vanguard Youth suffered heavy losses trying to resist Allied and Japanese advances beyond Saigon. Vietnam was already at war in the South.

The Southern Advance

Hearing earlier that the French might well be coming back to Saigon with the British, groups of young men in the North and center began heading down the coast. Province committees sponsored battalion or company-size contingents, and the public donated food, clothing, money, and medicine. The first well-organized unit arrived from Quảng Ngãi on September 25, just as Saigon descended into chaos. The first northern unit, battalion-size Detachment 3 (Chi đội 3), arrived in Biên Hòa on October 7. Detachment 3 had been raised among ethnic minority men in the Việt Bắc hills, then incorporated Kinh platoons along the way in Hanoi, Thanh Hóa, and Nghệ An. Approaching the Saigon River, Nam Long, the commander, was ordered to disable the rotating arch on the Bình Lợi bridge, only to be stopped by intense machine gun fire from a British-Indian unit on the opposite side. A Japanese officer then approached and advised Nam Long to withdraw quickly, as the British had just ordered a Japanese attack from the rear. The retreat became chaotic, with some Detachment 3 members ending up with southern units for the war’s duration, others making it east to Xuân Lộc, where they joined more than a thousand rubber plantation workers to occupy trenches dug by the Japanese nine months earlier. British armored cars and Japanese infantry overran Vietnamese defenders at the end of October. Survivors straggled to Phan Thiết, 125 miles (200 kilometers) further east.

By this time newspapers and radio broadcasts were touting a grand “Southern Advance” (Nam tiến) movement coming to the aid of beleaguered countrymen. This term had been employed previously to characterize the migration of ethnic Kinh from north to south over a period of 700 years. Early twentieth-century writers, influenced by Social Darwinism, had extolled the Nam tiến as proof of Vietnamese superiority compared to neighboring “races” (chủng tộc). At each railway station down the coast, Nam tiến units encountered big crowds, women offering food and drink, officials making speeches, slogans being yelled, and everyone joining in patriotic songs. Former members of the colonial Garde Indochinois were well represented in these units. Many desired to demonstrate loyalty to the DRVN and impart skills to the other volunteers, most of whom had no military experience.

At Phan Thiết, additional Nam tiến contingents kept arriving from points north, intent on pressing toward Saigon. Suddenly everyone had to face a Japanese battalion arriving by sea with British orders to disarm all natives. Three days of combat saw Vietnamese defenders forced into the countryside, where some joined locals to begin to learn how to fight guerrilla-style. Detachment 3 managed to retreat northeast to Phan Rang, where they caught the Japanese post by surprise, killing ten and capturing a quantity of arms and ammunition. Residents organized a victory banquet, with speeches, songs, banners, drums, and the ringing of temple and church bells. Detachment 3 was now exhausted, having fought four battles in six weeks, taken heavy casualties, and been reduced from 700 to only 250 men. On November 27 it withdrew toward Nha Trang, only to be thrown into action the next day.

Nha Trang, the largest town along the south-central coast of Vietnam, had a sizable Japanese base to care for several thousand wounded from the Burma front. On October 20, under British orders, the Japanese released and rearmed several hundred French colonial soldiers. Armed Vietnamese retaliated by seizing the train station and destroying the power station, but were forced to withdraw under bombardment by French warships. West of the city, Nha Trang evacuees and villagers dug a long trench line, aiming to prevent the French from cutting off movement of soldiers and supplies from north to south. In late January, the French Army launched a dramatic pincers offensive (Operation Gaur), dispatching one armored column through the Central Highlands to the coast just north of Nha Trang, and the second column through Đà Lạt and Phan Rang, then up the coast to Nha Trang. This threatened to trap all Vietnamese defenders in a French meat grinder. Several units managed to escape inland, then traipsed north across the hills to Phú Yên. Others joined local militia groups that would combat the French in Khánh Hòa province until 1954.

Võ Nguyên Giáp, National Guard commander and DRVN interior minister, happened to arrive outside Nha Trang just as the French columns approached. Giáp, who had never seen combat of even company-size magnitude, now witnessed French naval bombardment, artillery fire, air sorties, and armor and infantry units tightening the noose. Ordered by telegram from President Hồ Chí Minh to return to the capital, Giáp first detoured to An Khê, Pleiku, and Kon Tum in the Central Highlands – places he realized could become strategically significant. At a February 15 press conference in Hanoi, Giáp criticized the decision at Nha Trang to dig trenches and try to face the enemy, while neglecting to destroy roads and bridges, mobilize the populace, and begin to learn guerrilla tactics. At that moment it seemed likely the French would continue to advance up the central coast to Đà Nẵng. They chose instead from late February to concentrate on taking control in Tonkin. This gave DRVN adherents in the center precious time to build civilian and military capabilities in what became Region 5 (Khu 5), headquartered in Quảng Ngãi.

Military Organizing in the North

In May 1945, two company-size Việt Minh contingents in the Việt Bắc had merged to form the Vietnam Liberation Army, renamed the Vietnam National Guard in October. Although remaining de facto army commander, Võ Nguyên Giáp’s main job in the first DRVN cabinet was minister of interior. There was not much for a command headquarters to do at this point. More important was establishment of the General Staff (Tổng Tham mưu), headed by Hoàng Vӑn Thái, and the defense ministry, headed for some months by Chu Vӑn Tấn.Footnote 4 Thái recruited intellectually keen young men to fill sections for operations, intelligence, training, and personnel. Hoàng Đạo Thúy, respected Boy Scout commissioner, began building a military communications and liaison system.Footnote 5 A courier net begun earlier in the Việt Bắc was soon extending across the Red River Delta and down the north-central coast.

The fledgling defense ministry blitzed regional and province committees with action orders. Each province was to report: numbers of soldiers; names of unit commanders and political officers; numbers and types of weaponry; quality of ammunition; method of food supply; and “how the problem of uniforms was to be dealt with.”Footnote 6 Each northern province was to send ten men urgently to a platoon leaders’ course in Hanoi. The search began for relevant chemicals to make gunpowder and detonators. Army units were ordered not to frisk women while on patrol or initiating house searches. Any person detained by the military was to be turned over quickly to the police. Military courts would be established to try persons charged with harming Vietnam’s independence. When provinces began to ask about military pay and allowances, they had to be told that the treasury was nearly bare. Provisioning most troops became a province responsibility. Until the May 1946 harvest, the primary limitation on expanding the regular army was the severe shortage of rice.

Creating a national military school naturally followed. Already in the Việt Bắc hills of northern Tonkin, three short classes for platoon leaders and political officers had graduated 234 students. The first class in Hanoi began September 15, with a high proportion of students coming from the city’s secondary schools. A mix of Việt Bắc cadres, former officers of the colonial Civil Guard, and NCOs from the French Army constituted the teaching staff. Political lectures treated the current situation in Indochina and the world at large, the “liberation revolution,” and principles of leadership. President Hồ Chí Minh visited the academy, inspected the mess hall and lavatories, gave a short speech, and reviewed the class in drill formation.

With staff eager to find space for live firing and tactical maneuvers, the school was shifted to Sơn Tây, 21 miles (35 kilometers) west of Hanoi, a place of military significance for centuries. Each student now received one former Civil Guard uniform, a forage cap, and a pair of leather shoes, plus use of a kapok mattress, mosquito net, and wool blanket. With departure of Class 7 on April 16, 1946, the school could count a total of 1,500 small-unit leaders and political officers having graduated since the previous June. Two months later, General Nguyễn Sơn opened the Quảng Ngãi Ground Forces Academy, relying mostly on Japanese officers and NCOs for instruction.Footnote 7 Four hundred men took part in the first class. Everywhere the National Guard was being built along conventional lines, with guerrilla alternatives an afterthought at best.Footnote 8

Founding an army medical corps proved more difficult. As of October 1945 there were only three clinics for military personnel. All National Guard enrollees were supposed to undergo medical examinations, but standards were lax. Most ill soldiers were referred to civilian hospitals or clinics. Despite reports of heavy casualties in the South, and mindful that fighting might break out elsewhere, the General Staff failed to prepare medically for combat conditions. In November, the government suddenly ordered conscription of all doctors (y sĩ) and pharmacists (dược sĩ). This was the only attempt at conscription in the early life of the DRVN, and it failed. One year later, the DRVN health minister could only report 32 out of 182 doctors in the North enrolled in the National Guard. Training of medics proved more rewarding, with some 120 having graduated by July. A new army medical school inaugurated by President Hồ Chí Minh in November 1946 had to be shifted to the Việt Bắc when full-scale war broke out the following month.

The Nationalist Chinese Military Presence

Hồ Chí Minh understood that Vietnamese resistance to incoming Nationalist Chinese forces would be disastrous. Urgent orders went out to province people’s committees to avoid any altercations. Members of the Vietnam Nationalist Party (VNQDĐ) and Vietnam Revolutionary League accompanied Chinese units and pushed aside some Việt Minh groups in towns along the entry routes. Chinese quartermasters searched aggressively for food. Those villagers who failed to hide their grain in time were compelled to exchange it for an alien currency (Chinese “gold units”) of dubious value. On September 16, General Lu Han summoned Hồ Chí Minh to inform him of the exchange rate and discuss feeding Chinese troops. Lu Han could have shoved aside the DRVN government, but almost surely would have faced trouble in the countryside. On September 22, the day after General Gracey declared martial law in Saigon, Lu Han assured Hồ Chí Minh that he had no intention of following the British precedent, providing that public order was maintained. It soon became clear that Lu Han and other senior officers expected the DRVN to accept members of the Nationalist Party and Revolutionary League into a coalition government. Meanwhile, Chinese officers looked for ways to exploit the Indochinese economy down to the 16th parallel.

There were numerous local altercations between Chinese troops and Vietnamese civilians, most commonly in the marketplace. On arrival, the Chinese had simply seized rice warehouses without compensation. President Hồ Chí Minh’s promise to provide monthly deliveries fell well short. Chinese officers flew to Saigon to purchase shipments of rice to Hải Phòng for their troops, but as of November the British had only released 2,000 tons. Assuming that Chinese Army quartermasters had 100,000 mouths to feed, they required at least 2,500 tons of rice each month. The onus often fell on province administrative committees, at a time when many Vietnamese families were only eating one meal a day. As the Chinese began to withdraw in April 1946, province committees were left with large quantities of vastly inflated “gold units” that nobody would accept. Nonetheless, those ICP and Nationalist Party cadres who had witnessed terrible treatment of civilians during the war in China probably breathed a sigh of relief. Hồ Chí Minh appreciated that Lu Han had given the DRVN government six months of de facto protection from French attack north of the 16th parallel.

Learning by Doing

None of the ministers or vice ministers in the provisional DRVN cabinet had life experiences commensurate with their sudden responsibilities. The French had made sure of that. Ministers had to rely on third-echelon former colonial employees to explain decree and edict formats, record-keeping, budgeting, and reporting. Despite this, the new state performed surprisingly well. There was no interruption in telegraph and postal traffic. Food production and distribution took top priority. Personnel issues consumed much attention for several months. Tax collections resumed haltingly. A new Independence Fund (Qũy Độc Lập) began to receive public donations. French properties were requisitioned. Vietnamese properties seized in August became the object of petitions and counterpetitions. Families sought information on fathers and sons who had been taken away. As during the Pacific War, allocation of many commodities, including salt, alcohol, cloth, coal, newsprint, and opium, was subject to government control.

One new responsibility was preparing to elect a National Assembly. The provisional government immediately began drafting the necessary electoral rules and implementing instructions, relying on French-trained lawyers for advice. Each province or city was assigned a specific number of seats to be contested, based on 1937 population statistics. From early December, articles and editorials about the impending election proliferated, nudged on by the ministry of propaganda and Việt Minh activists. Registration of candidates proceeded slowly, and negotiations between Hồ Chí Minh and leaders of the Nationalist Party and Revolutionary Alliance stalled several times. Restrictions were enforced on individual campaigning. Newspapers in Hanoi became election vehicles for specific slates, a media practice learned from the French during the 1920s and 1930s.

National election day, January 6, 1946, took on the aura of a traditional festival in many villages and urban neighborhoods in Tonkin and Annam, with voters putting on their best clothing, flag-bearing youths marching from one street to another, and people converging on the community hall (đình) or office of the local administrative committee. Ballots did not have the names of candidates printed on them, so literate voters wrote in their selections, while illiterate voters who constituted the majority were often helped by Việt Minh youths, with predictable results. In Cochinchina, meanwhile, administrative confusion and French counteraction severely limited voting. The election was hardly an example of popular sovereignty, but it was certainly memorable. Most Vietnamese wanted to believe in the legitimacy of the DRVN, and the January 6 elections were considered proof positive by many.

During February, while Hồ Chí Minh was concentrating on diplomacy vis-à-vis the French and the Chinese, other DRVN leaders prepared to convene the first National Assembly session, which would elect a government of national union, formulate legislative procedures, draft a constitution, and enhance Hanoi’s capacity to direct local affairs. Getting 242 elected delegates to the Hanoi Opera House on the morning of March 2 was an extraordinary achievement – though only one delegate from the South made it. At the opening session, Hồ Chí Minh received assembly approval to add seventy “Vietnamese comrades from overseas who had not had time to participate in our country’s general election.” These Nationalist Party and Revolutionary League members were then escorted into the auditorium amidst calls of “Unity! Unity!” Hồ Chí Minh and Nguyễn Hải Thần, head of the Revolutionary League, were then elected president and vice president, although Thần was already furtively exiting the city.Footnote 9 President Hồ Chí Minh then presented his new coalition cabinet to the assembly. All swore fidelity to the Fatherland (Tổ quốc), as symbolized by an ancestral altar positioned at the back of the stage.

In what must have been disconcerting news to many delegates present, the meeting chair informed everyone that “In face of the current grave circumstances, the National Assembly […] must adjourn today.” The most pressing business was to elect a standing committee and a constitution-drafting committee. The chair then for the first time invited delegates to speak, which triggered more than an hour of animated debate concerning powers of the standing committee. Regarding the powers to declare war and cease hostilities, President Hồ Chí Minh insisted they must rest with the government, not the parliamentary standing committee. Rather than put this weighty question to a vote, the chair simply declared the issue had been decided. Nguyễn Vӑn Tố was elected chair of the 15-person standing committee.Footnote 10 The meeting’s chair then told everyone to return to their localities to “continue the resistance,” and to reconvene at a favorable opportunity, which turned out to be late October.

The DRVN’s Most Dangerous Moment

Rounding up C-47 Dakota aircraft from British or American sources, the French Army tried to convince General Lu Han to let it land a combat force at Bạch Mai airstrip in Hanoi. He rejected this idea. In mid-February, Hồ Chí Minh heard from Chinese sources that the French intended to land at Hải Phòng. Dire rumors soon swept through Tonkin. The principal Việt Minh newspaper was shut down by DRVN censors for three days for repeating a Reuters report. In a February 28 Sino-French agreement, French troops were authorized to relieve Chinese units north of the 16th parallel, in exchange for China being granted a free port at Hải Phòng, customs-free transit of goods, and special status for Chinese nationals residing in Indochina. The agreement completely ignored the existence of a Vietnamese authority, much to the dismay of both Hồ Chí Minh and the Vietnamese nationalists who had depended on Chinese support. Hồ Chí Minh immediately stepped up his negotiations with Jean Sainteny, and a Franco-Vietnamese “preliminary convention” was signed on March 6, recognizing the “Republic of Vietnam” as a “free state,” with its own government, parliament, army, and finances. On the thorny issue of Cochinchina, France agreed to accept the results of a future referendum concerning “reunion of the three Ky (regions).” Vietnam agreed to greet amicably French Army units coming to relieve the Chinese.

Hồ Chí Minh had kept all but a handful of lieutenants ignorant of the negotiating details, which caused other DRVN and ICP luminaries to take contradictory positions in public. The first indication that citizens had of the March 6 decisions was when, the next morning, proclamations were affixed to lampposts and walls in Hanoi and Hải Phòng. Public reaction ranged from quiet relief to vocal outrage. Later on March 7, Võ Nguyên Giáp, Vũ Hồng Khánh (Nationalist Party leader), and President Hồ Chí Minh addressed a large audience in front of the Hanoi Opera House, at what may have been the most critical meeting of Vietnam’s entire independence struggle. Giáp defended the convention on the grounds that the French were going to return anyway, at a time that the country was not ready for war. That left a deal as the only alternative. Khánh spoke next, emphasizing that complete independence was the ultimate objective, but that it would not be achieved in a single leap.

Taking the rostrum last, President Hồ Chí Minh asked rhetorically, “Why in fact sacrifice 50,000 or 100,000 men when we can by means of negotiation attain independence, perhaps in five years?”Footnote 11 Nonetheless, the immediate danger was that unruly youths would attack French civilians, or that rogue militia would shoot at arriving French soldiers. Extensive patrolling by Chinese troops helped to prevent this from happening. On March 9, the ICP standing bureau issued an “instruction” to members titled “Compromise in order to Advance.” While predicting that reactionary French colonialists would try to sabotage the preliminary convention, starting with the question of Nam Bộ/Cochinchina, the standing bureau also saw a “New France with a new spirit of freedom.” Therefore, the new party slogan was “Ally as equals with New France.”Footnote 12 On March 18, a French column of 220 vehicles with 1,200 troops traveled from Hải Phòng to Hanoi with no incident.

Patriots/Traitors

In August–September 1945, probably no feeling was more widespread than national solidarity – the joy expressed when “the people” join together to defend the “nation,” or, more colloquially, “our country” (nước ta). Simultaneously, however, rumors of sedition swept Vietnam’s towns and villages. Alleged “Vietnamese traitors” and “reactionaries” were detained, humiliated, beaten up, and sometimes killed. At the September 2 mass meeting in Hanoi, Võ Nguyên Giáp told the audience that “division, doubt, and apathy are all a betrayal of the country.” Toward the end of the meeting, when Hồ Chí Minh was given the ceremonial sword of former emperor Bảo Đại, he joked that henceforth it would be used to “cut off traitors’ heads” rather than oppress the people as before. In the following weeks, the government failed to provide any definition of treason or sedition.Footnote 13

A host of “secret investigation” (trinh sát) units had cropped up earlier, often not reporting to any government committee or political party. The ICP possessed a central investigation committee, headed by Trần Đӑng Ninh, which worked to insert ICP members into local investigation units.Footnote 14 From early 1946, the government tried via the police to exercise more authority. The Nationalist Party condemned secret investigation units for striking fear into citizens, ignoring due process, and siphoning off resources better allocated to the military. A quiet but intense struggle for control of the police (Công an) took place, with the independent and respected interior minister, Hùynh Thúc Kháng, unable to prevent the ICP from shoving aside his appointee as general director.Footnote 15

One of Hồ Chí Minh’s early decrees had authorized the “security service” to arrest persons “dangerous to the DRVN” and send them to deportation camps (trại an trí). Subsequently local committees were ordered to either release people who were confined or send them to the nearest deportation camp. Most province committees managed to ignore Hanoi requests to supply political detainee names and locations. Droves of petitions addressed to President Hồ Chí Minh sought information on family members believed to be detained somewhere.Footnote 16

Nine military courts were decreed in September to punish past “enemies of the revolution” and delineate what constituted treason against the new democratic republic. It took some months to select judges and begin taking cases. Perhaps the first trial took place in Huế, with the prime accused being Nguyễn Tiến Lãng, former mandarin and director of emperor Bao Dai’s cabinet. Condemned as a French lackey, Lãng was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment and the loss of two-thirds of his property.Footnote 17 Lãng’s better-known father-in-law, Phạm Quỳnh, had been killed earlier in Huế by the ICP city committee. Military courts soon fell behind in their 1946 case calendars, with an increasing number of cases dealing with acts taking place after establishment of the DRVN.Footnote 18

The most significant challenge to DRVN authority came from the Vietnam Nationalist Party. ICP/Nationalist competition had existed earlier among political prisoners in colonial jails, and between émigrés in southern China during the Pacific War.Footnote 19 The ICP jumped ahead of the Nationalist Party in early 1945, as its Việt Minh message attracted thousands of enthusiasts in Tonkin particularly. Nationalist Party members coming into Tonkin with the Chinese Army garnered followers along the way, but then suffered a major setback when General Lu Han decided to work with Hồ Chí Minh. The Nationalist Party’s daily newspaper, Việt Nam, offered a lively counterpoint to Việt Minh papers. Party leaders secured positions in the DRVN cabinet of national union, but once the Chinese Army began to leave the ICP stepped up its pressure. Its tactic, as delineated by Trường Chinh, head of the ICP’s Standing Bureau, was to win over some members, exacerbate divisions, then repress the “traitorous elements.” By July, armed Nationalist Party units were forced northward, thence across the border. A few Nationalist Party delegates to the National Assembly remained on in a figurehead capacity. In the countryside, to be labelled a Nationalist Party member became synonymous with treason.Footnote 20

ICP Operations

“Self-dissolution” of the party in November 1945 did not slow down the de facto standing bureau’s efforts to gain hegemony over Việt Minh groups everywhere. After acknowledging how many workers, peasants, youths, and intellectuals were devoted passionately to the revolution, Trường Chinh instructed subordinates: “Have confidence in them, employ them boldly, guide them patiently, but do not forget to control them” [his emphasis].Footnote 21 The Vietnam Democratic Party (Đảng Dân chủ Việt Nam), proud member of the Việt Minh Front since 1944, resisted ICP efforts to infiltrate and dominate. Its daily newspaper, Độc Lập (Independence), offered readers significantly different interpretations from the ICP-run Cứu Quốc (National Salvation). Democratic Party members could be found in most government ministries and Việt Minh committees operating in northern towns. The party’s National Congress in September 1946 counted 235 delegates present from as far away as Huế. Debate was wide-ranging and lively. If war had been averted, the Democratic Party would have played a more significant role in Vietnam’s history than proved to be the case.Footnote 22

Trường Chinh was quite disturbed about ICP behavior in Cochinchina. In August 1945, he had favored the Liberation regional committee. Subsequently Trần Vӑn Giàu and Phạm Ngọc Thạch were told to disband the overall Vanguard Youth organization, then ordered to come to Hanoi for disciplinary action.Footnote 23 Trường Chinh criticized cadres in the South for allowing “all sorts of opportunists, provocateurs, and persons of complicated background” to enter the party. He subsequently chose Lê Duẩn, a native of Quảng Trị, but possessing many southern friends from shared prison time, to return south to form a committee to reorganize the party in Cochinchina. It appears that many Vanguard Youth adherents gravitated instead to southern National Guard units under the command of Nguyễn Bình, who was not an ICP member.Footnote 24

In late July 1946 in Hanoi, the ICP organized its first central cadres conference, to communicate the current line and signal a push for more political power. Each comrade was to nominate one new member to his party cell, higher echelons would open training classes for lower echelons, and pamphlets would be printed for cells to use in study sessions. In the party’s mass mobilization efforts, priority would be assigned to workers, women, and youths. In mid-October, Trường Chinh chaired a military conference that marked an unmistakable move by the ICP into the realm of defense policy. Much discussion was devoted to the question of how to increase ICP control within the National Guard. The party set a goal of at least one cell within each National Guard company within two months, which would not be achieved until much later.Footnote 25

At commune (xã) and village levels, Việt Minh activities continued to be sparked mostly by members of the Youth National Salvation and Women’s National Salvation groups. Any available ICP member tended to be older and probably not yet in contact with higher echelons. Party pronouncements from Hanoi often did not reach local members for months, if at all. A party meeting in Huế criticized members for terrorizing or denigrating petit bourgeois intellectuals, state employees, and shopkeepers. Comrades within the government failed to “submit to party discipline.”Footnote 26 By the end of 1946, total ICP membership may have climbed to 25,000 compared to the scattered 5,000 in August 1945. This still only amounted to perhaps one ICP member per 800 of the population. And most recruitment took place on a personal, ad hoc basis, with very little organizational vetting and no indoctrination.

Trường Chinh and others made no secret of the ICP’s determination to monopolize power. The ICP gained hegemony over much of the police in 1946, and aimed to do the same with the National Guard. But it seems that Hồ Chí Minh, Võ Nguyên Giáp, and Hoàng Vӑn Thái had other priorities, even though all three were party members. The DRVN civil administration and National Guard continued to function distinctly from the ICP, although senior party members undoubtedly shaped policies. Only after establishment of the People’s Republic of China in late 1949 did Trường Chinh and others have the opportunity to engineer an ICP takeover of the DRVN state.

Popular Organizing

From August 1945, newly minted DRVN citizens came together to talk politics, form groups, demonstrate loudly, occupy colonial properties, and seek out contacts beyond their own village or neighborhood. Young men and women took the lead, scornful of elders who cautioned against haste or intemperance. Vietnam’s villages had a rich history of organizing groups for multiple purposes, but public oratory, clapping, marching, and yelling slogans was new. Revolutionary imagery, dramatic skits, and patriotic music captivated audiences. Most compelling of all was the red flag with yellow star, which quickly came to symbolize the nation for all but a small minority. Thousands of meetings began with a solemn flag-raising ceremony. Catholic groups took the flag as national standard, despite its ICP/Việt Minh Front origins. The marching song “Advancing Army” (Tiến Quân Ca) by Vӑn Cao and Đỗ Hữu Ích was already becoming the national anthem.Footnote 27

Forming a local militia (tự vệ) group took top priority among young men. Most carried only a machete or bamboo spear, with perhaps several individuals boasting a shotgun or old musket. A former Civil Guard member might teach basic drills. Every tự vệ member took turns standing guard at the village gate and patrolling at night, while tilling fields the rest of the time. Militiamen often aspired to be accepted into a provincial-level National Guard battalion. Young women were free to form their own militia group. Militias not only prepared to fight foreign invaders, but often took part in local power struggles. Some dared to harass agents of higher authority, notably tax agents. Local administrative committees and Việt Minh committees sometimes competed for control of the militia.

Literacy classes cropped up around the country. Early on, Hồ Chí Minh had listed the “ignorance bandit” (giặc dốt) for elimination, along with the “famine” and “foreign aggressor” bandits. When his efforts to redirect colonial-era education inspectors and senior pedagogues toward a mass literacy campaign became bogged down, Hồ Chí Minh turned to Youth and Women’s National Salvation groups to take the initiative. In the preface to an early literacy textbook, Hồ Chí Minh pointed out that “Women especially need to study, since they have been held back so long. Now is the time for you sisters to work to catch up with the men, to demonstrate that you are part of the nation, with the right to elect and be elected.”Footnote 28 Many literacy instructors had only three or four years’ schooling themselves. Crude slates and chalk had to suffice in the absence of paper and pens. Outside, individuals who could not read a patriotic slogan or recite the alphabet were publicly shamed. The most humiliating village practice was to set up a “Gate for the blind,” through which all illiterates had to pass while being jeered by children mobilized for the occasion. National Guard members proved the most disciplined literacy pupils.Footnote 29

Probably an additional 300,000 citizens could read a newspaper article or leaflet as a result of the mass literacy campaign, far fewer than wished. The outbreak of full-scale war in December 1946 disrupted the campaign for several years. Still, village cadres knew they could not fulfill their responsibilities without at least acting as if they could read the burgeoning number of handwritten permits, authorizations, and requests that came their way. The operative slogan soon became “We must be literate to emerge victorious in the Resistance.”Footnote 30

Health challenges faced the DRVN government from the beginning. Epidemics had to be tackled, the colonial-era medical system upgraded, and the populace informed on health realities. Given financial constraints, however, there was no hope that the state would soon address the ambitious modernizing agenda that Vietnamese health professionals had in mind. As noted earlier, the highest priority was assigned to building an army medical corps. Next the ministry of health increased vaccine production and inoculation efforts. It also tried to sustain the modest existing hospital system and train more nurses in particular. Newspapers recruited Western-trained physicians to write a health column. District and village Việt Minh groups took up the challenge of convincing citizens to improve public hygiene and sanitation. Wherever such hygiene efforts succeeded it was because they formed part of a wider mass mobilization strategy. “To be hygienic is to love your country” was daubed on walls. Cadres also employed peer pressure, and came back again and again to ensure compliance. Military units set the best example, boiling drinking water, burying feces, disposing of garbage, treating cuts, and showing high regard for their medics.Footnote 31

Young women wishing to engage wholeheartedly in the revolution faced many more problems than young men. Often they remained under pressure from their families to stay at home, get married, and bear children. Those young women who did “emancipate” (thoát ly) themselves from home and village still faced a political culture dominated entirely by men. Women of all ages joined the Women’s National Salvation Association in order to be able to convene away from men, share experiences, make a public contribution, and, they hoped, carve out some political space for themselves. Association members collected donations, cultivated secondary crops, organized literacy classes, enforced hygiene rules, and assisted families of absent soldiers. Chairs of women’s committees routinely served on Việt Minh committees, and interacted with chairwomen in adjacent villages.Footnote 32 At the central level, however, only eight out of 290 National Assembly delegates who convened in late 1946 were women.Footnote 33 Female representation in the higher echelons of the ICP was no better.

Imagining the Country

In mid-1946, a newspaper article published in Huế artfully described an exchange about the “Fatherland” (Tổquốc) between a Catholic village elder and a young intellectual. The elder invoked the communal house (đình), pagoda, church, graves, family, village rice fields, and “all the achievements of my ancestors.” The youth scorned this vision as narrow-minded and provincial. “The Fatherland is our mountains and rivers, our cultural inheritance, the history bequeathed by our ancestors,” he insisted. To this the elder replied, “Your Fatherland is remote, insipid, lifeless.” When the two of them began to debate Marshal Pétain’s wartime slogan of “Work, Family, Fatherland,” the DRVN censors terminated the article in mid-sentence.Footnote 34

Most intellectuals considered “fatherland” too remote a term. They much preferred the more emotive đất nước (literally “land-water”) or variations thereof, such as nước nhà. One respected writer took nước nhà to link personal feelings with collective demands:

Interestingly, reversing nước nhà to nhà nước produced the blunt, unemotional designation for “the state.” Patriotism was literally “to love one’s country” (yêu nước), which is why the English term “nationalism” fails to express Vietnamese sentiments.

Much of Vietnam’s political vocabulary was quite new. Forty years earlier Vietnamese literati had encountered Japanese and Chinese words that had only recently been coined from Western language terminology. These included: nation, society, struggle, progress, modernity, democracy, republic, independence, freedom, and sovereignty. The new intelligentsia of the 1920s and 1930s had begun to integrate these new words into the Vietnamese language, but it was not until 1945 that the population at large began to take them on via speeches, slogans, banners, leaflets, and literacy classes. When talking among themselves, the intelligentsia continued to use French terms like nation, état, unité, societé, progrès, révolution, réactionnaire, modernité, élan, and mobilisation when talking among themselves.

How was the name Democratic Republic of Vietnam selected? Being a shortwave news addict at his Tân Trào camp during the summer of 1945, Hồ Chí Minh would have heard quickly about a number of eastern European states occupied by Soviet troops being given new titles. There was the Polish People’s Republic, Hungarian People’s Democracy, Socialist Republic of Romania, People’s Republic of Bulgaria, and People’s Socialist Republic of Albania. Hồ Chí Minh undoubtedly assumed that Stalin was directly involved. Deliberately avoiding rank imitation, Hồ Chí Minh chose a name with some semantic elbow room. “Democratic republic” was internationally unique. It was approved at the very brief National People’s Congress on August 16 and reaffirmed at the Independence Day mass meeting on September 2. Meanwhile, however, Hồ Chí Minh and some others employed the title “Republic of Vietnam” when communicating in French or English. And the March 6, 1946, preliminary convention, signed by Hồ Chí Minh, Jean Sainteny, and Vũ Hồng Khánh, spoke of the Republic of Vietnam, not the DRVN. This may only have been diplomatic cosmetics. But it is also possible that Hồ retained the option of dropping “democratic” in the nation’s constitution being drafted in Hanoi while he was in Paris. If so, he doesn’t seem to have raised the idea upon his return in October.

Peace and War Conflated

Franco-Vietnamese armed conflict unfolded in various parts of Indochina throughout the sixteen months from September 1945 to December 1946. First Cochinchina was embroiled, then southern Annam. The General Staff Agreement signed April 3, 1946, in Hanoi was adhered to north of the 16th parallel for some months. French intransigence at a Franco-Vietnamese conference in April–May at Dalat shocked the twenty prominent Vietnamese intellectuals who participated. On June 1, Indochina’s new high commissioner, Admiral Georges Thierry d’Argenlieu, announced the formation of the Autonomous Republic of Cochinchina. When President Hồ Chí Minh heard of this in Cairo, en route to Paris on an official visit, he considered returning home. French forces seized Pleiku and Kontum on June 21. Four days later they took over the former governor-general’s palace in Hanoi as it was being vacated by Nationalist Chinese forces, triggering a general strike.

On August 3, a large French convoy en route from Hanoi to Lạng Sơn came under sustained machine-gun fire as it passed through Bắc Ninh town, with fifteen French soldiers killed and more than thirty wounded. Perhaps some senior ICP cadres had linked up with an army unit based in Bắc Ninh and the local militia. Realizing the gravity of this attack, Võ Nguyên Giáp worked together with French officers to prevent further such incidents.Footnote 36

A modus vivendi signed by Hồ Chí Minh in Paris on September 14 was a big disappointment at home. The noncommunist press dissected it critically. Trường Chinh convened the ICP standing bureau to discuss war. “Sooner or later, the French will attack us and we certainly will have to attack them,” the meeting concluded.Footnote 37 The only tangible result of the modus vivendi was a ceasefire in Cochinchina and southern Annam, which held for a couple of days before armed confrontations resumed. Hồ Chí Minh and d’Argenlieu exchanged messages reiterating bluntly the most important issue at stake between the two sides: was Cochinchina part of Vietnam or France? The French Army then took advantage of a dispute in Haiphong over customs duties to send tanks into the city and bombard whole neighborhoods with naval gunfire, killing thousands of people. Vietnamese newspapers immediately grasped the gravity of events, and the ICP/Việt Minh general headquarters published a rousing declaration that assumed war was inevitable.

In early December, Jean Sainteny told Hồ Chí Minh that DRVN troops must be withdrawn from Cochinchina, Haiphong would remain under French control, Radio Bach Mai should be relinquished, and France would be free to suppress all terrorism. The French Army wanted the Vietnamese to attack first. Hồ Chí Minh tried hard to make contact with León Blum, the new Socialist Party prime minister, without success. Instructions went out to prepare for nationwide attacks, but the subsequent execution order gave units only seven hours to get into position. Assaults in Hanoi were poorly coordinated and mostly failed to achieve their objectives. Elsewhere the element of surprise was lost when French units received word of the fighting in Hanoi before coming under attack themselves.

The clash of two political forces intent on regaining or gaining national honor and a sense of collective purpose had made compromise impossible. For many Vietnamese participants it was the Anti-French Resistance (Kháng chiến chống Pháp) that was now underway, not the Indochina War or the Vietnam War.

Thousands of DRVN civil servants evacuated the capital in late December, mostly lacking information on where to go. Some had already sent their families to home villages, others left them in Hanoi, still others brought them along to an uncertain fate. President Hồ Chí Minh and other cabinet members headed westward toward a planned “safe area.” In late February, Hồ Chí Minh visited Thanh Hóa province to consider whether to move the central government down there or not. Thanh Hóa had the merits of a large population and extensive rice fields, but any French offensive that forced the government into the hills would have left them vulnerable to enemy attack from Laos. In early March, a French armored sortie from Hanoi westward convinced Hồ to shift the government northward to the Việt Bắc hills.Footnote 38

For the National Guard to endure during the summer of 1947, regiments had to disaggregate to battalions, and commanders often found it necessary to disperse companies to different districts to obtain food and shelter. In early October, the French Army began a three-pronged offensive (Operation Léa) in the Việt Bắc designed to capture or kill the DRVN leadership, destroy supply depots hidden in limestone caves, and sever contacts with China. Trường Chinh was almost captured, and one senior government official killed.Footnote 39 After three months the French withdrew, except for several new bases along the Chinese frontier. The DRVN central government would not again be seriously threatened during either the First or Second Indochina War.

Power, Authority, and Legitimacy

Việt Minh groups seized power in Hanoi and vicinity in late August 1945, enabling Hồ Chí Minh to announce the establishment of the DRVN and declare Vietnam’s independence. Elsewhere, groups waving Việt Minh flags took over public buildings, formed committees, and received their first DRVN telegrams from “the center.” Next, the government had to forge authority so that people would obey rules and practices, whether new or continuing, without significant opposition. Communication of this new order was achieved by print, radio, speeches, and word of mouth. Authority required Hồ Chí Minh and his ICP lieutenants to work together with members of the progressive intelligentsia and former colonial employees to address immediate issues of food, defense, finances, and foreign affairs.

Legitimacy derived in the first instance from people believing that the DRVN government could prevent France from retaking Cochinchina, Annam, and Tonkin. It soon became clear that the government intended to push each and every citizen to take part in this patriotic endeavor. There were repeated millenarian calls to sacrifice, to fight, and perhaps die in defense of the fatherland. Additional Việt Minh groups organized by gender, age, occupation, religion, and ethnicity sprang up in most villages and urban neighborhoods. Unless Vietnamese were very young or very old it was nigh on impossible to avoid joining up. Not surprisingly, some citizens felt this was compulsion, not voluntary support for what they agreed was a legitimate cause.

Considering how many restrictions the French colonial system had placed on “native” schooling, personal advancement, or political responsibility, the DRVN civil administration, National Guard, and growing Việt Minh network were performing remarkably well in late 1946. The claim that the DRVN was “no more than a skeleton” overlooks this unexpectedly strong performance during its first year of existence. Instead of the skeleton metaphor, the DRVN is more usefully understood as an “archipelago state.”Footnote 40 Of course, the French colonial state was also an “archipelago,” albeit one built primarily around the control of urban “islands.” In Cochinchina, the French occupied Saigon and then portions of the Mekong Delta, where the Cao Đài and Hòa Hảo sustained enclaves as well. They then moved into the towns of southern Annam, followed by Hải Phòng, Lạng Sơn, Hanoi, parts of the Red River Delta, and Huế.

The main “islands” of the DRVN “archipelago” in 1947 were the Việt Bắc, Zone III in the southern Red River Delta, Zone IV in northern Annam, and Zone V in southern Annam. In the Mekong Delta, smaller DRVN islands could be found in Zone VII (The Plain of Reeds) and Zone IX (the Cà Mau peninsula). As Goscha points out, communications proved vital to connecting the islands of the archipelago state. DRVN radio-telegraph networks continued to function. Lower-priority messages went via the labor-intensive courier system that operated in French-held areas as well as the “islands.” Each zone had its own printing presses for newspapers and broadsides.Footnote 41

Evidence suggests that DRVN legitimacy persisted for many people living in French-controlled areas after 1946. One can see this in the lightly censored Saigon press of 1946–7, as most papers backed DRVN independence and the territorial integrity of Vietnam, while condemning Cochinchina “separatists.” The most credible participant in Admiral d’Argenlieu’s Cochinchinese council, Nguyễn Vӑn Thịnh, realizing that he had neither power, authority, nor legitimacy, committed suicide on November 10, 1946.Footnote 42 DRVN legitimacy was further enhanced by French attempts to “deport” DRVN supporters from Cochinchina. In March, the French commander of the Biên Hòa region told representatives of Nguyễn Bình, head of DRVN Military Region VII, that all “Tonkinois” personnel would be sent back to Tonkin, and that Bình himself would be flown to Hanoi. In reply to the French colonel, each delegation member proudly identified himself as coming from the south, center, or north of a united nation.Footnote 43

If Cochinchinese residents had been given the referendum opportunity mooted in the March 6, 1946, accord, it is reasonable to suppose that a majority would have voted for unification. Of course, to imagine what might have happened subsequent to such a vote is speculative. What actually unfolded is clear enough: despite Hồ Chí Minh’s best efforts to find a peaceful path to independence, the fate of the DRVN and all of Indochina was to endure a massive and savage war that would last for almost a decade and cost hundreds of thousands of lives. The “Anti-French Resistance” would arguably become the bloodiest of all of the wars of decolonization that erupted around the globe after 1945; it would also draw attention and eventually direct interventions from other foreign powers, including the United States, the People’s Republic of China, and the Soviet Union. Amid the carnage and the escalating superpower rivalry, Trường Chinh and other ICP leaders would gradually secure their control over DRVN institutions and policies, especially after 1950. The result by 1954 was a state that looked and functioned very differently from the nascent DRVN state that emerged during 1945–6, while Indochina was still suspended between war and peace. The consolidation of one-party rule would have profound and lasting consequences for Vietnam, both during the era of the “Vietnam War” and down to the present day.

Legislative measures often determine the official chronology of a war, both its start and finish. After careful discussions starting in 1950, the French government approved the creation of a “Commemorative Medal for the Indochina War” on August 1, 1953. This official medal established the starting date of the “Indochinese campaign” on August 16, 1945. Legislation passed on January 29, 1958, set the end of the war on August 11, 1954, when the ceasefire brokered during the Geneva Conference officially entered into effect. During this conflict, in all, some 21,000 French soldiers from Metropolitan France had died. This represented, however, less than a quarter of the total 89,000 military deaths suffered by the French Union camp: 11,500 North Africans, 3,700 Africans, 9,200 Foreign Legion soldiers, 27,000 indigenous (mainly Vietnamese) auxiliary personnel, and 17,000 members of the armed forces of the Associated States of Indochina (the majority of whom were Vietnamese).Footnote 1 As many as 500,000 Vietnamese died during the war, civilians and combatants alike.

There are many ways to study the French side of the Indochina War. Here we focus on the international context, examining the complex issues French decision-makers faced at the crossroads of imperial, global, and regional events. Stuck in a difficult position since the humiliating defeat at the hands of Germany in the spring of 1940, French policymakers were particularly sensitive to the international dimensions of the Indochina War.

How the War Began, 1945–7

The Indochina War began at the intersection of three phenomena. First, although Europeans had realized during World War II that their empires needed to be modernized and reformed to make room for the demands of the elites of the colonized peoples, many still considered them to be an essential component of international power and prestige. During World War II, Free France relied heavily on the African empire, a source of manpower for a Free French army. Liberated by the Allies in 1944, the French counted on their empire to help rebuild a war-torn economy and return the country to the world stage. Empire would also allow the French room to maneuver between the two post–1945 giants, the United States and the Soviet Union.

Second, the humiliation of 1940 followed by the Axis occupation of France in Europe and Indochina in Asia imposed upon the French after the war the pressing need to recover their territorial possessions ante bellum. It was essential to erasing the stain of 1940 and affirming the “white man’s prestige” in Indochina. French settlers, officials, and businessmen in Indochina were traumatized by the Japanese coup de force of March 9, 1945, which brought French Indochina down. And because the French could not intervene when the Japanese capitulated to the Allies on August 15, 1945, Hồ Chí Minh and the nationalist front he created in 1941, the Việt Minh, took advantage of the power vacuum to declare Vietnam’s independence on September 2, 1945. This meant that the French would have to reconquer Indochina in order to reestablish their sovereignty there. The context in which this would occur would be one of nationalist turmoil, a result of the economic, social, and political consequences of the world war, the sudden disappearance of the Japanese empire, and anticolonial sentiments which the Japanese had fanned. It was a difficult situation for the French. Losing the Indochinese link in the imperial chain could set a precedent, encouraging nationalists in other parts of the empire to follow suit. Nonetheless, it was still possible that this anti-imperialist effervescence could still be quickly suppressed and controlled, as it had been after World War I. Or at least that’s what some French leaders thought. In any case, the French, on left and right, wanted their empire back.

Third, the imperative of reconquering and controlling the empire led to a wave of repressive violence from North Africa to Vietnam by way of Madagascar.Footnote 2 In East Asia, this wave of colonial violence combined with the brutalization of Asia societies during World War II, under the Japanese, and at the hands of a host of armed groups used by the Japanese, the British, and the Americans, to say nothing of the associations and paramilitary organizations the Japanese had operated among the young. The legitimacy of the empire and the repression used to restore it enjoyed widespread support at the time in the French ruling class. In the early years, the French Communist Party (FCP) was not yet an advocate of decolonization. Not only did the FCP want to show its nationalist credentials acquired during war against the Nazis, which guaranteed them electoral successes immediately after 1945, but the communists were also of the mind that France, for cultural and historical reasons, could and should still do much for the colonial peoples. It was also important for the PCF to protect French colonies against US imperialist ambitions.

Starting in 1943, the French provisional government led by Charles de Gaulle in Algiers sought to prepare the liberation of Indochina by force, and, to this end, de Gaulle did his best to incorporate Free France’s Indochinese strategy within the wider plans of the Allied Powers. The French provisional government begged for Allied help in arming and transporting some troops. However, the Japanese coup of March 9, 1945, not only eliminated a good deal of the underground resistance inside Vietnam, but Paris quickly realized that the liberation of Indochina would occur without the French. The Americans seemed to want to keep the French at arm’s length in the Far East. At the Potsdam Conference in mid-1945 (to which the French were not privy), the Allies decided that the Republic of China would disarm the Japanese in Indochina north of the 16th parallel while the United Kingdom would do the same below that line. Surprised by the unexpectedly early Japanese surrender, de Gaulle could not accept this. He actively pursued the departure of the Chinese and British troops and their replacement with the French Expeditionary Corps whose soldiers, upon arrival, would have the right to circulate freely in all of Indochina.

De Gaulle wanted Indochina back in the empire. The problem is that this would not be so easy. Taking advantage of the Japanese overthrow of the French in March, followed by the Japanese capitulation to the Allies on August 15, the independence leader and founder of the Việt Minh, Hồ Chí Minh, declared the independence of Vietnam on September 2, 1945. The Vietnam the French had eliminated from the map of the world in the late nineteenth century was back and would not be sidelined so easily again in the mid-twentieth. Based out of the capital of Hanoi, the new nation-state was called the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN). It claimed all of Vietnam in a single territorial state – the regions the French called Cochinchina, Annam, and Tonkin to refer to the colony in the South and the protectorates in central and northern Vietnam, respectively.

De Gaulle and most of the French political class at the time still thought in these prewar colonial terms. The framework of the Gaullist Indochinese policy had been hammered out by the provisional government on March 24, 1945. An Indochinese federation consisting of five “regions” (Annam, Tonkin, Cochinchina, Cambodia, and Laos) would be created and join a French Union, the new name for the empire but which had yet to be formally created.Footnote 3 In negotiations with Hồ, the French were determined to create a French Union and to place Indochina within it, including Hồ Chí Minh’s Vietnam. Annoyed by Emperor Bảo Đại’s abdication in late August 1945 and his support of Hồ’s national government, de Gaulle had turned to another member of the royal family to help him recover French Indochina, Prince Vĩnh San. Nothing came of this royalist card, though: the latter died in a plane crash in December 1945.

Upon arriving in Saigon in early September, British General Gracey facilitated the return of the French to southern Indochina below the 16th parallel. The situation in Saigon was, however, very complicated. Vietnamese revolutionary committees, not all of them under Hồ Chí Minh’s control, had operated freely since the Japanese surrender a few weeks earlier. Thousands of Japanese were awaiting disarmament and repatriation. US officers who had arrived, too, sent reports to Washington on events in Indochina. Meanwhile, French settlers made no secret of their desire to see colonial rule re-established quickly, nor did they hide their disdain for the envoys from metropolitan France who counseled patience and compromise. Hostilities broke out in this explosive southern mix when Gracey allowed colonial troops imprisoned by the Japanese in March to dislodge Hồ Chí Minh’s officials from Saigon. The troops of the French Expeditionary Corps, sent by de Gaulle and led by General Leclerc, landed in southern Indochina in October and began to reestablish French sovereignty below the 16th parallel by force but not before a Vietnamese massacre of around a hundred French settlers in Saigon. War had effectively begun below the 16th parallel.

The Chinese were reticent to facilitate the return of the French to their zone of responsibility in northern Indochina, fearful of setting off a colonial war above the 16th parallel as the British had just done below it. As a result, the Chinese effectively allowed Hồ Chí Minh’s government to continue to operate from Hanoi while war raged in the south. The French realized that they would have to negotiate with the Vietnamese government in Hanoi and the Chinese occupation forces in order to return to Indochina above the 16th parallel. The treaty signed with the Chinese in February 1946 secured the withdrawal of Chinese troops. Most left in June, with the last soldiers withdrawing in September. At the same time, the French signed an accord with DRVN President Hồ Chí Minh, on March 6, 1946. This document allowed the French to transfer 15,000 troops above the 16th parallel to replace the departing soldiers. The French did not, however, have the right to overthrow the government they now recognized as part of a future Indochinese federation. The accord also stipulated that the French forces would withdraw from the DRVN within five years. In mid-March, General Leclerc entered Hanoi as French troops assumed positions in the main cities in upper Indochina. To maintain order, French military commanders joined with their counterparts in the DRVN to eliminate anticommunist nationalists who had rejected any compromise with the French in March. Meanwhile, hardliners in Paris felt that the French had given away too much to Hồ (they derided the March 6 agreement as a new “Munich”), particularly the annex limiting the duration of the French military presence in Vietnam.

Between March and December 1946, a “strange war” occurred. French officers who believed that the military situation was improving in their favor felt that it was now possible to adopt a tougher line in negotiations. On the other hand, those who believed the situation remained fragile pleaded for additional military reinforcements. Follow-up negotiations took place in Vietnam (in Đà Lạt first, which was to be the capital of the Indochinese federation) and then in France (in Fontainebleau). The question of the diplomatic representation of the DRVN was a major point of contention. The French were concerned about DRVN efforts to gain international recognition and affirm its national sovereignty as an independent state. But for Paris, there was no question about responsibility for the Union’s diplomacy – it would be the French, not the Vietnamese. Another dispute concerned the unity of Vietnam claimed by Hồ Chí Minh. De Gaulle’s high commissioner for Indochina, Thierry d’Argenlieu, who at this time enjoyed the support of the postwar government in Paris, insisted that Cochinchina was a French colony separate from Hồ Chí Minh’s Vietnam – a position backed by most settlers and certain other elites in the region.

On the French side, there was no common position in these negotiations. During 1946–8, a large part of the political battle for Indochina was played out in Paris. The hardliners opposed to decolonization succeeded in imposing themselves through bureaucratic micro-actions, such as political appointments or budgetary arbitration. The colonels of the colonial army within the National Defence General Staff were influential, too, working in cooperation with officers advising French officials in Indochina. Meanwhile, d’Argenlieu was urged to act like Gallieni and Lyautey, both of whom had confronted Paris with imperial faits accomplis in the nineteenth century. The unstable political landscape in the metropole allowed the high commissioner to do this. Even following de Gaulle’s resignation in early 1946, d’Argenlieu took advantage of the changing governments in Paris in 1946 to advance his policy to retake all of Indochina. Events came to a head in late 1946 when the Fourth Republic finally came to life. D’Argenlieu and fellow hardliners in Indochina and France suspected Léon Blum, the newly appointed socialist leader of the republic, of wanting to make concessions to Hồ. These men enjoyed the support of the Mouvement Républicain Populaire (MRP) and encouraged d’Argenlieu to act against the DRVN. They would cover him. Socialists who had colonial responsibilities, such as Marius Moutet, also supported the aggressive line on Vietnam.

The French bombing of the port city of Hải Phòng in November 1946 was one of those faits accomplis pushed by the hawks working with d’Argenlieu at the helm in Indochina. The heavy-handed reoccupation of Haiphong came at the cost of hundreds – perhaps thousands – of Vietnamese civilian lives. The high commissioner was angered by the partial application of agreements by the DRVN thus far. He also wanted to expand France’s colonial grip whenever and wherever he could, as well as to be in a position of strength to launch wider military operations if necessary. After Haiphong, leaders on both sides were losing patience with the voices calling for conciliation. Unless one side ceded on its claims to sovereignty over all of Vietnam, war was inevitable by late 1946. Their backs to the wall, the Vietnamese attacked the French on the evening of December 19, 1946, setting off full-scale war in all of Vietnam. The Vietnamese massacre of dozens of French settlers in Hanoi during the street fighting in late December allowed the hardliners to put an end to the “farce” that had constituted the talks with the Vietnamese, who, in their view, had shown their duplicity and barbarism just like the Japanese before them. It was, in fact, a pretext to retake all of Indochina by force if necessary – just as de Gaulle had directed d’Argenlieu to do upon naming him high commissioner in September 1945.Footnote 4

Several goals guided French military operations following the outbreak of full-scale war. First, the army sought to free central Vietnam from the DRVN’s hold, considered “frightening but not invincible.” Second, toward the end of 1947, the French would attack the resistance government in the Northern Highlands by capturing its leadership and destroying its army with an airborne operation known as Opération Léa. It came close to achieving the first goal, but failed on the second. Third, although the French had backed Vietnamese expansionists, ambitions upon building Indochina at the turn of the twentieth century, they now supported all those who had problems with the Vietnamese government led by Hồ. The French warned the Cambodians, Cochinchinese, and the minority peoples living in the Highlands of the dangers of “Annamese imperialism.”