On a rainy afternoon in January 1937, President Franklin Roosevelt encouraged Americans “to find through government the instrument of our united purpose to solve for the individual the ever-rising problems of a complex civilization.”Footnote 1 Half a century later, President Ronald Reagan told Americans that “the nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I'm from the government, and I'm here to help.”Footnote 2 These two presidential statements illustrate a fundamental shift in how Americans perceived and talked about the government's ability to address domestic problems. But the two statements, and the two presidencies, did not mark neat beginning and end points.Footnote 3 By the time Roosevelt delivered his second inaugural address, a big effort to disparage domestic programs had been underway for more than a decade. This persuasion effort—and the conservative movement it propelled—primed Americans to embrace a strand of selective anti-statism that began to shape American political development long before Reagan's presidency.

The literature on American conservatism blossomed after respected political historian Alan Brinkley lamented the state of the field in 1994.Footnote 4 Despite the outpouring of scholarship, however, leading conservatism scholar Kim Phillips-Fein is correct that “the larger questions that Brinkley posed about reckoning with the strength of conservatism in our larger U.S. history narratives have not been fully answered.”Footnote 5 One of the biggest of these unresolved questions is why many Americans soured on domestic state building in the mid-twentieth century. Scholars have advanced many promising answers to this question, ranging from public discontent at labor turmoil and growing fears of communism to the simple change in the country's economic fortunes in the 1940s.Footnote 6 These explanations all have merit. But they tend to rely on changes in public opinion reflected in opinion polls or in the even cruder proxy of electoral outcomes. Both explain only what people believed, not why.

The use of polling data to try to determine why Americans believed what they believed in this period is particularly problematic. Opinion polling was in its infancy in the first half of the twentieth century, and sampling methods did not meet subsequent standards for representativeness. Rather than probability sampling—in which every American was equally likely to be interviewed—these early polls typically relied on “quota-controlled” sampling, meaning pollsters decided whom to interview.Footnote 7 This methodological deficiency renders the results suspect. A group of political scientists devised ways to correct for this problem, but when using the cleaned data to try to explain why public support for domestic state building eroded, these scholars concluded that the precise determinants of opinion could not be traced backward from the data.Footnote 8

Colleagues in psychology suggest an alternative—and broadly applicable—way of determining which inputs matter. They established long ago that the frequent repetition of messages shapes minds.Footnote 9 Public opinion scholar Robert Shapiro has urged inquiries applying this insight to the study of American political development, calling for greater attention not just to the content of political messages but also to their volume.Footnote 10 Applying this approach to the question of why many Americans soured on domestic state building brings the nascent conservative movement to center stage.Footnote 11 During the intense fight over the government's domestic responsibilities from the 1920s through the 1950s, conservatives sent an ever-increasing and ultimately enormous volume of political messages—billions of them—disparaging domestic programs.Footnote 12 By the 1940s, the volume of conservative messaging swamped messages delivered by the champions of domestic state building. If the frequent repetition of messages shapes minds, then this deluge of conservative messaging demands attention.

Thanks to the careful work of many scholars, we know quite a bit about the people and organizations responsible for these messages.Footnote 13 The work of the Du Pont brothers and J. Howard Pew, to name a few people, and the Sentinels of the Republic, the American Liberty League, and the National Association of Manufacturers, to name a few organizations, have all received thorough attention. But scholars have struggled to render clear judgments about the impact these people and organizations had on public opinion, on the development of the conservative movement itself, and on American political development more broadly. The problem stems from a tendency to evaluate these early conservative persuasion efforts independently at moments in time rather than considering their collective impact over a longer period, coupled with a tendency to pay more attention to direct messaging than to indirect influence.Footnote 14 By clarifying the connections between these efforts and evaluating their impact collectively—paying attention to both indirect influence and to the volume of repeated messaging—this article helps resolve longstanding uncertainty about what these early conservatives achieved.

Analyzing large numbers of records associated with the people and organizations responsible for these early conservative persuasion efforts reveals a striking continuity of personnel and messaging that makes clear that these efforts were neither independent nor episodic.Footnote 15 This analysis shows that the conservative movement originated in the 1920s when a small number of business leaders organized and financed initiatives to turn public opinion against the expansion of the government's domestic responsibilities.Footnote 16 This interlocking directorate of business leaders formed the nucleus of what grew into the big tent conservative movement, as historian George Nash aptly characterized it.Footnote 17 The first step toward a fuller appreciation of what the persuasion efforts overseen by these business leaders achieved is to see these efforts as they saw them: as components of a long-term campaign. This campaign served as a rallying point for the conservative movement starting before Franklin Roosevelt's presidency and helped the movement coalesce and gain influence by the late 1940s, more than a decade earlier than the current scholarly consensus suggests—and long before Ronald Reagan took the presidential oath.Footnote 18

The people running the conservative persuasion campaign believed that if Americans doubted the government's ability to solve domestic problems, they would be less willing to support domestic programs. Government—and taxes—would shrink as a result. Putting this premise into action, conservatives sowed doubt about the government's competence in the domestic sphere. The clever ways conservatives disparaged domestic programs—through amusing but damning anecdotes delivered repeatedly via trusted “opinion molders” and through “public service advertising”—helped a negative impression of domestic programs burrow into American political consciousness largely unopposed and with the methods largely unnoticed. Indeed, the fullest scholarly exploration of why the public came to look skeptically on the government focuses on what the government did to create what Amy Lerman calls a “reputation crisis” for itself.Footnote 19 Government actions that many Americans found disagreeable or inept undoubtedly contributed to negative public perceptions. But this focus on government action minimizes the conservative persuasion campaign's decades-long role in interpreting government action to the public—usually critically—and therefore overlooks the extent to which those who wanted the public to hold the government in low regard helped manufacture the “reputation crisis.”

Three phases of the conservative persuasion campaign contributed most directly to the negative shift in the way Americans perceived and talked about domestic programs. The first important phase began during the second half of the 1930s when the business executives leading the conservative movement hired public relations professionals to orchestrate the campaign. These public relations specialists developed the reach and persuasion playbook that became central to the campaign's effectiveness and, by extension, to the conservative movement's influence. The introduction of two tactics in this foundational phase mattered most. First, the campaign's architects used endless repetition to cultivate impressions and make them stick. Second, the campaign's architects relied not just on direct messaging, which those who disagreed with the message might ignore, but also on indirect persuasion. The campaign's architects wooed women, teachers, religious leaders, and other “opinion molders” who could deliver tailored anti-statist messages to trusting audiences over an extended period. In this foundational first phase of the campaign, conservatives fostered the impression that the government could not solve the day's most pressing domestic problems and that its efforts to do so were farcical. But with the Roosevelt administration and its allies delivering a large volume of messages advocating for domestic economic security programs amid persistent economic depression, conservatives made little immediate headway.

During the campaign's second important phase in the first half of the 1940s, conservatives used the reach and persuasion tactics developed in the first phase to tell two stories about World War II that sowed further doubt about the government's domestic abilities.Footnote 20 First, conservatives cultivated the impression that the private sector, not the government, deserved credit for the return of prosperity that accompanied the huge increase in production triggered by the war. Second, conservatives argued that the private sector's wartime production record proved its superior competence compared with the government, which—according to conservatives—produced little more than miles of “red tape” during World War II. Conservatives’ success peddling these narratives in the face of contrary facts testified to the conservative persuasion campaign's growing power, a function largely of the increase in the volume of its messaging relative to countervailing messages.

In the campaign's third important phase beginning in the late 1940s, the campaign's architects used amusing examples of domestic policy incompetence unearthed by former President Herbert Hoover's Commission on the Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government to belittle domestic programs more broadly. Working through the ostensibly nonpartisan but conservative-run Advertising Council, conservatives successfully used the guise of “public service advertising” to cloak their efforts to disparage domestic programs. This clever ruse provided the conservative persuasion campaign with a veneer of nonpartisanship and abundant free advertising space—a potent combination that enabled conservatives to swamp countervailing messages and, as n-gram charts make clear, helped conservatives cement rhetoric disparaging domestic programs in mainstream political discourse.Footnote 21

In these ways, the conservative persuasion campaign primed many Americans by the late 1940s to embrace a strand of selective anti-statism that paired mockery for and reluctance to fund domestic economic security programs with rhetorical and financial support for a robust military and foreign policy establishment.Footnote 22 Working in concert with and reinforcing other historical developments, this strand of selective anti-statism did much to shape American political development after World War II. Under this selective anti-statism, many Americans supported the creation of robust state capacity in the military and foreign policy realms but resisted comparable efforts to build the government's domestic policy capacity. The ironic result was a patchwork and little-respected—but still large and expensive—domestic policy establishment and an enormous, expensive military and foreign policy establishment.

The Origins of the Conservative Movement and Its Efforts to Shape Public Opinion

The modern American conservative movement and the accompanying effort to undermine public confidence in the government's ability to solve domestic problems originated in the battle to repeal the Eighteenth Amendment, which outlawed the production, transport, and sale of alcohol.Footnote 23 The interlocking directorate of businessmen who served as the conservative movement's leaders saw the Eighteenth Amendment as what historian Robert Burk calls “The Opening Wedge of Tyranny.”Footnote 24 In their eyes, Burk writes, the Eighteenth Amendment exemplified “the federal government's growing threat to private property, individual liberty, and personal choice.”Footnote 25 To meet this threat, William H. Stayton, a conservative-minded, wealthy Washington lobbyist, founded the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment (AAPA) in 1918.Footnote 26 Stayton's objective with the AAPA was broader than its name implied. Uneasy over what he saw as the trend toward greater centralized government power, he hoped to “educate the public on the broader subject of a ‘proper’ interpretation of the Constitution.”Footnote 27 Despite Stayton's efforts, the AAPA made little progress toward its objectives in the first decade of its existence.Footnote 28

In the final years of the 1920s, however, a group of business leaders led by the brothers Pierre, Irénée, and Lammot du Pont took over the AAPA and expanded its efforts as part of what Pierre du Pont deemed an attempt “to straighten out our political affairs.”Footnote 29 In addition to an immediate desire to replace corporate and income taxes with taxes on legalized alcohol, the du Ponts hoped an invigorated AAPA could turn public opinion against future expansions of the government's domestic responsibilities.Footnote 30 Pierre du Pont's private observation that “the collateral issues outweigh the liquor question” underscored that du Pont, like Stayton, saw the AAPA's work as deeper than its stated focus on Prohibition.Footnote 31

With the generous backing of the du Ponts and the other business leaders who joined the AAPA's leadership ranks, the AAPA became a laboratory for conservatives to experiment with organizational approaches and persuasion techniques to shape public opinion at scale. As historian George Wolfskill notes, “For sheer power and professional efficiency the propaganda machine of the AAPA surpassed anything the country had ever seen.”Footnote 32 The AAPA's persuasion efforts marked the beginning of the conservative movement's organized effort to develop a shared vocabulary with which to disparage domestic programs. The AAPA operated research and information bureaus, which disseminated anti-Prohibition propaganda nationwide emphasizing the dangers of expanded government responsibilities and the expense, corruption, and ineptitude that followed.Footnote 33 The association also cultivated grassroots and grasstops support among women, professional groups, and youth by creating committees and auxiliaries.Footnote 34 Between 1928 and 1932, the du Pont brothers contributed $400,000 to the AAPA, equivalent to more than $6 million today—a huge sum by the standards of political spending at the time.Footnote 35

Although they eventually succeeded in helping to end Prohibition, the conservatives behind the AAPA had not achieved their larger goal of halting the expansion of the government's domestic responsibilities. On the contrary, the expansion accelerated in the early 1930s. As the Great Depression deepened, the public looked increasingly to the government to address the country's economic problems. As a result, when the AAPA board of directors mothballed the organization in December 1933, they resolved “that the individual members of the Executive Committee … continue to meet from time to time and have in view the formation of a group, based on our old membership in the association, which would in the event of danger to the Federal Constitution, stand ready to defend the faith of the fathers.”Footnote 36 To the du Pont brothers and their long-time colleague John J. Raskob, the danger materialized in June 1934 when Franklin Roosevelt proposed what became known as Social Security.Footnote 37 In a series of intense discussions during July 1934, the du Pont brothers; Raskob; John W. Davis, a leading New York corporate lawyer and 1924 Democratic presidential nominee; executives from General Motors and General Foods, including Colby Chester; and other business leaders decided to try to turn the public against Roosevelt's efforts to expand the government's domestic responsibilities.Footnote 38

Building the Conservative Persuasion Playbook and Expanding the Campaign's Reach

The July 1934 discussions produced the American Liberty League. Headed by former AAPA president Jouett Shouse and launched in August 1934 from the same Washington, DC office from which Shouse had run the AAPA, the Liberty League said it wanted “to preserve for succeeding generations the principles of the Declaration of Independence, the safeguards of personal liberty and the opportunity for initiative and enterprise provided under the Constitution.”Footnote 39 Although ostensibly an inclusive organization intended to advance the interests of all Americans, the League's dependence on the activism and generous financing of a couple dozen wealthy businessmen and bankers made the organization easy to caricature and dismiss.Footnote 40 Democratic National Committee Chairman Jim Farley said the Liberty League “ought to be called the American Cellophane League” since “first, it's a du Pont product and second, you can see right through it.”Footnote 41

Despite these political liabilities, the League boosted the conservative movement's prospects by capitalizing on the recent revolution in the fields of advertising and public relations, which became much more effective in the first three decades of the twentieth century thanks to a boom in academic psychology and the extensive experience public relations specialists gained manipulating public opinion during World War I.Footnote 42 The fields evolved from a reliance on the dry presentation of facts to the cultivation of impressions through multichannel repetition, and from direct persuasion to indirect persuasion via opinion leaders.Footnote 43 Public relations specialists also learned to provide people with sticky rhetoric they would repeat, amplifying the original message.Footnote 44 The conservative movement benefited disproportionately from these advances because leading public relations professionals counted as clients many firms headed by the conservative movement's leaders. The Liberty League's decision to retain public relations consultants such as Edward Bernays, a leader in the field, brought these modern persuasion techniques into the conservative persuasion campaign, and they continued to shape the conservative movement for decades.Footnote 45

But adopting these persuasion techniques did not guarantee success. The campaign's effectiveness also depended on its ability to reach large numbers of Americans. To that end, the League and its public relations advisors expanded the campaign's reach, sending millions of pamphlets and press releases to thousands of public and college libraries; to hundreds of newspapers and press associations and editorial writers; and to an ever-growing mailing list.Footnote 46 By passing its material off as “news,” the League gained extensive media coverage without having to pay for advertising.Footnote 47 The League even started its own news service, the Western Newspaper Union, to supply news stories and editorials—both written with a conservative slant and without attribution to the League—to more than 1,600 newspapers in the South, Midwest, and West.Footnote 48 The League also took advantage of free time offered by radio stations to push its conservative message over the airwaves.Footnote 49 Finally, the League published a bulletin featuring not only articles and updates on League activity but also funny and embarrassing anecdotes about the Roosevelt administration's domestic policy foibles—a continuation of earlier AAPA efforts to sow doubt about the government's ability to solve domestic problems.Footnote 50

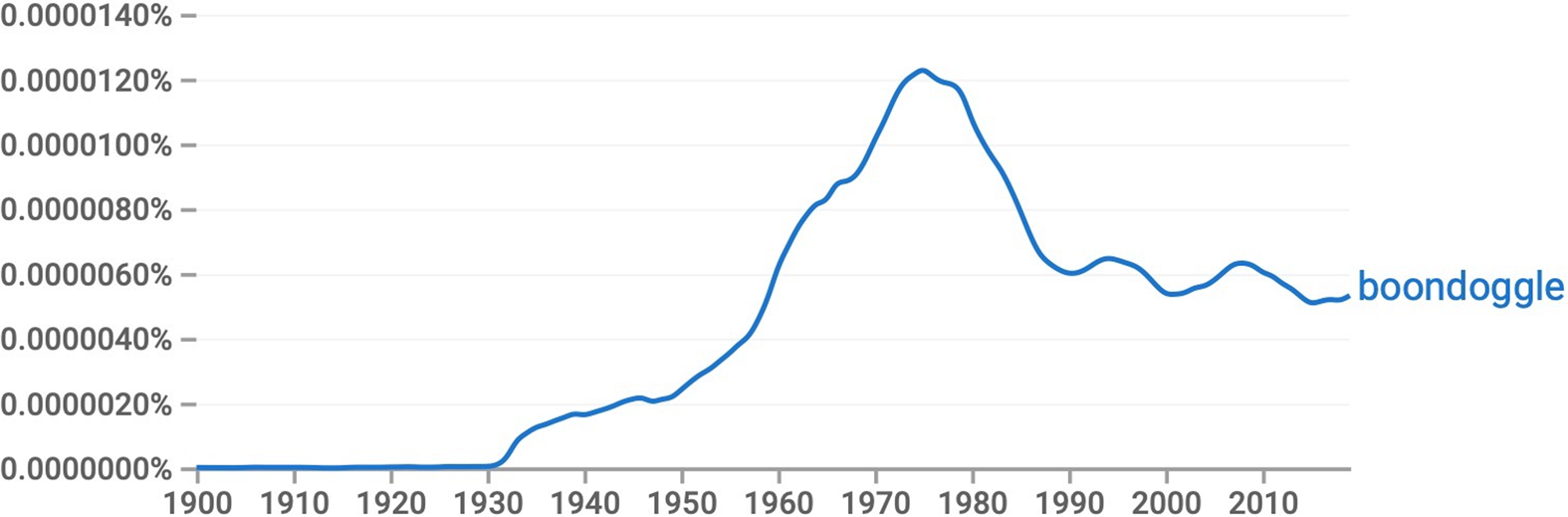

The League mocked domestic economic security programs as farcical and ruinously expensive using a recent addition to the American political vocabulary: “boondoggling.”Footnote 51 The word originally referred to a leather decoration Boy Scouts produced and wore on their uniforms beginning in the second half of the 1920s.Footnote 52 By the mid-1930s, however, conservatives had begun using the term to refer to domestic economic security programs of questionable value. The term burst onto the national political scene in April 1935, when the Chicago Tribune and the Wall Street Journal pounced on an amusing story about a crafts-maker seeking work relief funds to make boondoggles.Footnote 53 The Wall Street Journal published a piece the next day decrying “A Nation of Boon-Doggles.”Footnote 54 The League amplified these efforts to belittle domestic programs through its multichannel persuasion campaign. In a national radio broadcast in June 1936, League President Jouett Shouse told Americans, “The New Deal has instituted a series of boondoggling enterprises which are as ridiculous as they are unwise.”Footnote 55 The League also distributed lengthy lists of questionable domestic economic security initiatives to millions of Americans in a leaflet called “The New Deal Boondoggling Circus” and in a longer pamphlet.Footnote 56 An n-gram chart showing boondoggle's increasingly frequent appearance in print sources beginning in the 1930s makes clear that the word stuck (see Figure 1).Footnote 57

Figure 1: n-gram chart for “boondoggle” in American English, 1900–2019.

So did the negative impression of domestic programs the word boondoggle fostered. But the League's progress incorporating modern persuasion techniques into the conservative persuasion campaign and popularizing derisive rhetoric that devalued domestic programs proved insufficient to defeat Roosevelt in 1936, while what one conservative critic called “New Deal propaganda” continued to flood the country.Footnote 58

Roosevelt's resounding re-election largely discredited the American Liberty League and left the business executives leading the conservative movement in need of a new vehicle for their persuasion efforts. They found it in the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM). Established in 1895 to represent the interests of American manufacturing companies, the NAM fell on hard times during the Depression.Footnote 59 During the winter of 1931–1932, however, a group of business leaders calling themselves the “Brass Hats” did to the NAM what the du Pont brothers had done to the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment, taking over the organization, revitalizing it, and placing it in the vanguard of the conservative persuasion campaign.Footnote 60 The reinvigorated NAM concentrated on making public opinion less favorable to the government and more favorable to the private sector.Footnote 61 The NAM decided not merely to retain public relations consultants—as the Liberty League had done—but also to bring public relations specialists Walter Weisenburger and James P. Selvage in house, marking a further step in the professionalization of the conservative persuasion campaign.Footnote 62 When General Foods Chairman and former Liberty Leaguer Colby Chester took over the NAM presidency in 1936, NAM's persuasion efforts took off.Footnote 63

The NAM developed an effective persuasion playbook that built on the successes and learned from the mistakes of the AAPA and the Liberty League. The playbook emphasized reach and repetition. Observers at the time expressed astonishment at the NAM campaign's reach. An unnamed United States Senator noted—accurately, if perhaps apocryphally—that the NAM “used every possible method of reaching the public but the carrier pigeon.”Footnote 64 After spending the better part of an afternoon listening to Walter Weisenburger describe NAM's efforts, a member of the NAM's Public Relations Advisory Committee declared “I am perfectly overwhelmed by the amount of work you people do.”Footnote 65 The NAM campaign repeated the conservative message to tens of millions of Americans every day, often multiple times per day.Footnote 66 A NAM campaign summary captured the extent to which Americans of all ages—mostly unwittingly—encountered the conservative persuasion campaign from the time they woke up in the morning until the time they went to bed at night.Footnote 67 Americans heard the conservative message on the radio upon waking, read it in articles planted in their morning newspapers, encountered it on billboards and public transit ads on the way to work, read it again in publications provided at work or at school, and heard it again in lectures in civic clubs and at the movies in the evening.Footnote 68 This daily deluge of conservative messaging mattered because, as psychologists have shown, the frequent repetition of messages shapes minds.Footnote 69

The public relations professionals running the NAM campaign also concluded from the Liberty League's direct messaging failures that shifting public opinion would take time and that conservatives needed to devote more energy to delivering messages indirectly through trusted “opinion molders,” among whom the NAM counted women, religious leaders, and teachers.Footnote 70 These people had the power to deliver the conservative message to trusting audiences without arousing suspicion, and they also had special influence over what the NAM called the “on-coming generation.”Footnote 71 The NAM's efforts to woo different groups of opinion molders followed the same pattern: lavish them with attention, supply them with material, and groom them at conferences.Footnote 72 For example, the NAM sent packages to the heads of women's clubs around the country containing everything needed to hold a successful meeting on topics of interest to conservatives: sample meeting invitations and announcement flyers, program outlines, talking points for the discussion leader and other speakers, and even a draft discussion summary to distribute after the meeting.Footnote 73 The importance of women and religious leaders to the conservative movement's subsequent development suggests the NAM invested wisely.Footnote 74

The NAM's efforts to shape young minds via teachers proved just as important to the conservative movement's long-term fortunes. The NAM sent thousands of lesson plans to teachers, complete with supporting print and visual materials as well as booklets teachers could assign as homework.Footnote 75 By 1939, Weisenburger reported, “We are getting more requests [for this material] than we can possibly fill,” and by the early 1940s, “two of every three American high school students” read NAM booklets in school.Footnote 76 The NAM also worked to control the distribution of rival messages by commissioning a study of 800 popular school textbooks “so that its members might move against any that are found prejudicial to our form of government, our society or to the system of free enterprise.”Footnote 77 The NAM also took an active interest in high school and college debate, working through proxies to shape debate topics and providing material with what Weisenburger called “a conservative viewpoint” to debaters.Footnote 78 Participants’ difficulties obtaining needed material elsewhere only increased the opportunity for influence in Weisenburger's eyes.Footnote 79 The NAM rushed to meet the need. In addition to printed material, the NAM also distributed films for use in schools. “[P]ictures,” NAM Public Relations Director James P. Selvage explained, “have become accepted more and more as the most impressive medium for leaving a lasting impression upon children … during their formative years.”Footnote 80 The NAM wanted to start the repetition process early. Weisenburger reported that, as with printed material, demand from schools for NAM films far outstripped supply.Footnote 81 Like its courting of women and religious leaders, the NAM's efforts to influence young people via teachers greatly expanded the conservative persuasion campaign's influence.Footnote 82

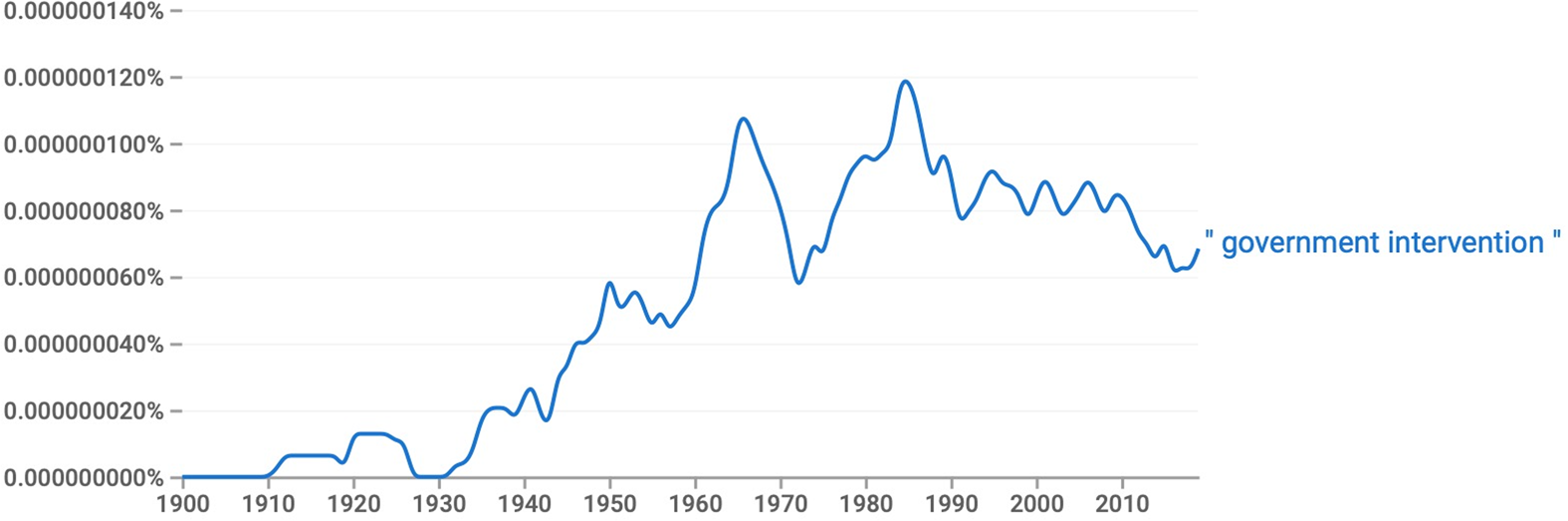

The NAM used regular public opinion polling to understand public attitudes and concerns, gauge the effectiveness of persuasion efforts, and adjust as necessary.Footnote 83 Based on these surveys, the NAM decided to use the term “government intervention” rather than “the more common terms ‘government control’ or ‘government regulation’” because “government intervention” “not only summons up a more graphic picture of actual government management of business, but it has an added semantics value in that fewer people will attempt to defend government intervention than will try to justify either government regulation or government control.”Footnote 84 Similarly, the NAM emphasized the shortcomings of “bureaucracy,” the “symbol which is most illustrative of the public's distaste of undue governmental power.”Footnote 85 Large-scale analysis of print sources in the United States since the 1930s makes clear that the careful choice of words and framing worked. An n-gram chart shows how the phrase “government intervention” took off after conservatives made it a focus of their messaging (see Figure 2).Footnote 86

Figure 2: n-gram chart for “government intervention” in American English, 1900–2019.

The phrase remains a negative keyword in discussions of economic policy, and “bureaucracy” remains a byword for government inefficiency—facts that continue to reinforce the negative perception of domestic economic security programs conservatives want the public to hold. Although the NAM campaign could not claim immediate political results amid a continuing deluge of countervailing messages from Roosevelt and his allies in the late 1930s, the NAM's efforts nevertheless positioned the organization as the central force in the conservative persuasion campaign. “One of the most encouraging things,” Weisenburger told the Public Relations Advisory Committee in 1939, “is the fact that more and more we are becoming recognized as conservative headquarters.”Footnote 87

Private Sector > Government

The people running the NAM campaign used its wide reach and indirect influence to tell Americans repeatedly that they could not count on the government to provide the economic security they wanted and that they should look to the private sector instead. Just as Franklin Roosevelt called attention to the government's constructive role in communities through visits to stadiums, bridges, dams, and other pieces of federally funded infrastructure, so too did NAM member companies begin publicizing the role their operations played in sustaining communities around the country. But the NAM and its member companies also took this approach one step further by minimizing or omitting completely the government's contributions. A General Motors (GM) campaign exemplified this approach. At open houses, in short films, and in newspaper advertisements, GM emphasized that its paychecks enabled local businesses to thrive.Footnote 88 The government did not feature. As the NAM campaign's architects summarized the message: “private enterprise is the only source of jobs” and therefore the only source of “real security.”Footnote 89

The public relations specialists running the NAM campaign saw in World War II an opportunity to emphasize the private sector's contributions to Americans’ wellbeing and to minimize the government's contributions.Footnote 90 Massive government wartime spending paid for a dramatic increase in production and a return to full employment, but the NAM campaign did everything possible to ensure the government did not receive credit for the return of prosperity. And at this crucial moment, the Roosevelt administration dialed down the volume of its messaging in support of its domestic economic security agenda.Footnote 91

Along with the endless repetition of their messaging, conservatives succeeded in denying credit to the government because most Americans engaged in war production felt they were working for companies, not the government. As historian Mark Wilson has shown, this belief was an ironic consequence of the Roosevelt administration's decision to use the government-owned, contractor-operated (GOCO) model for the vast majority of wartime production.Footnote 92 Under the GOCO model, the government paid for vast new plants like the million-square-foot bomber plant near Dallas, Texas, and leased many of them for $1 a year to companies like North American Aviation to operate.Footnote 93 At its peak, 38,000 people worked at the North American Dallas bomber plant, and they received paychecks from North American—not the government.Footnote 94 Reliance on the GOCO model for so much wartime production allowed conservatives to foster the impression that business, not government, deserved credit for the increased economic security many Americans felt even though government contracts provided those jobs.Footnote 95

The public relations specialists running the NAM campaign also used World War II to cultivate the impression that the private sector was more competent than the “bungling” government and that the government's principal contribution to the war effort was miles of “red tape.”Footnote 96 Conservatives lionized the private sector's contributions to war production and omitted the crucial details that the government paid for and supervised the overwhelming majority of it.Footnote 97 An October 1943 Service for Plant Publications article circulated by the NAM emphasized the leadership of business executives, the “men who equip our fighting forces, men who meet payrolls, pay taxes, employ millions—the men upon whom Americans have always leaned for jobs, for wages, for a higher standard of living.”Footnote 98 A piece in the March 1944 issue of Service for Plant Publications argued similarly that “Production is Proof” that “We Run It”—in other words, business runs the country.Footnote 99 Using every element of its multichannel campaign, conservatives told Americans again and again that the private sector deserved credit for the “miracle of production” and the return of prosperity. By denying credit to the government for both, the NAM hammered home the message that the private sector was both more competent and better able than the government to provide the economic security Americans sought as they emerged from the Great Depression.Footnote 100

Using “Public Service Advertising” to Disparage Domestic Economic Security Programs

The Advertising Council, run by an influential set of conservative public relations experts and business executives, succeeded the National Association of Manufacturers as the most important player in the conservative persuasion campaign in the late 1940s. The Ad Council developed out of advertising executives’ frustration with negative public perceptions of their profession in the 1930s and dissatisfaction with Franklin Roosevelt's success in expanding the government's domestic economic security responsibilities. At a joint meeting of the Association of National Advertisers and the American Association of Advertising Agencies in Hot Springs, Virginia, in November 1941, leading advertising executive James W. Young made the case to his colleagues that they needed to deploy the power of advertising on behalf of themselves and “free enterprise.”Footnote 101 The final lines of Young's speech called his colleagues to arms: “We have within our hands the greatest aggregate means of mass education and persuasion the world has ever seen—namely, the channels of advertising communication. We have the masters of the techniques of using these channels. We have power. Why do we not use it?”Footnote 102 Young's address moved his colleagues to action, but before they could get their effort off the ground, Japanese attacks and a German declaration of war brought the United States fully into World War II.Footnote 103

Like the public relations specialists running the NAM campaign, the Ad Council's conservative leaders saw the war as a tremendous persuasion opportunity. Through what they called “public service advertising,” advertisers and businesses would aid the war effort and generate public goodwill for themselves while also demonstrating business leadership on matters of national importance and subtly denigrating domestic programs. Although ostensibly a nonpartisan organization, in private the Ad Council's leaders made clear their conservative views and opposition to the Roosevelt and Truman administrations' domestic economic security policies.Footnote 104 Like the NAM, the organization was, as Ad Council Director and General Foods executive Charles Mortimer, Jr. put it, “a creature of business.”Footnote 105 The Ad Council's decision to continue operating after the war reflected its leaders’ belief that the organization could play an important role in the coming “ideological battle.”Footnote 106 At least some Ad Council staffers clearly agreed. When they came across a pamphlet from an organization called The People's Lobby advocating further expansion of the government's domestic economic security responsibilities, they marked up the pamphlet in pink pencil—noting the deliberate use of that color to reflect what they perceived as the pamphlet's socialist tinge—and filed the pamphlet in their Future Plans folder.Footnote 107

But the Ad Council's conservative leaders understood that the organization's ability to influence public opinion depended on maintaining a solid veneer of nonpartisanship.Footnote 108 The Ad Council's success maintaining that nonpartisan veneer enabled the organization to sell its work as “public service advertising,” making the organization even more valuable to the conservative movement than the continuing NAM campaign. In “public service advertising,” the Ad Council developed a subtler and more effective means of indirect persuasion than what the NAM achieved working through “opinion molders.” The nonpartisan image also enabled the Ad Council to obtain vast amounts of free advertising content and space from media and advertising companies, giving the organization even greater reach than what the NAM, quite impressively, had managed.Footnote 109 Messages delivered by the Ad Council made billions of reader, viewer, and listener “impressions” each year.Footnote 110 As a repetition tool, the Ad Council had no match.

In the period after World War II when the government's domestic responsibilities remained undetermined, the Ad Council helped to foster a selective anti-statism by encouraging Americans to support spending for “national security,” defined narrowly to include only foreign policy and physical security, and to oppose spending for domestic economic security programs increasingly saddled with the “welfare” label.Footnote 111 Truman understood and deplored what conservatives were trying to do. He noted in January 1947: “There are certain programs of Government which have come to be looked upon as ‘welfare programs’ in a narrow sense. This has placed them in an insulated compartment,” where, Truman understood, they would likely receive less public support.Footnote 112 The cold war's onset a few months later all but guaranteed substantial investments in military and foreign policy capacity.Footnote 113 The question at the time was: would the country also expand its domestic policy capacity substantially? The conservative persuasion campaign helped ensure the answer would be no. “[T]he essence of the advertising method,” Ad Council Director Charles Mortimer, Jr. reminded his fellow Ad Council board members, “is repetition—of saying basic facts over and over until, like postage stamps, they stick to one thing until they get there.”Footnote 114 In the years after World War II, the “basic facts” the Ad Council repeated over and over sowed doubt about the government's domestic policy competence and testified to the private sector's superiority.

Ironically, former President Herbert Hoover rose from the political grave to supply the Ad Council with ammunition for its subtle but powerful selectively anti-statist campaign. Beginning in late 1947, Hoover chaired the Commission on the Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government, which the Republican-controlled 80th Congress created to provide the template for shrinking the government ahead of an anticipated Republican victory in the 1948 presidential election.Footnote 115 Even before Harry Truman's surprise victory denied conservatives the opportunity to enact the commission's recommendations directly, Hoover saw the need to sell the public on the commission's recommendations. A Hoover Commission memo from January 1948 underscored the importance of making “people see the entire meaning of the whole report in terms they can understand,” such as “The hope for freedom and lasting good government,” “Removal of the fear of bureaucratic control,” and “Inviting them to fight waste, duplication, and the cancerous growth of bureaucracy.”Footnote 116 Truman's victory only made the task more urgent.

Hoover sought a public relations expert to help build public support for his commission's recommendations. On the advice of a friend, he selected Charles Coates, an assistant director of public relations at General Foods, the company that had supplied so many of the conservative persuasion campaign's architects.Footnote 117 Coates and the other conservative public relations experts advising the Hoover Commission devised a simple and devastating strategy for publicizing the commission's findings. They decided to highlight amusing examples of government folly in the domestic policy realm unearthed by the commission to persuade the public that such ineptitude was endemic and that the “bungling bureaucrats” working on domestic policy did not deserve high levels of either tax dollars or public trust.

Conservatives did not want the Hoover Commission to share the fate of so many other blue-ribbon panels that faded into obscurity soon after completing their work. To keep pressure on the White House and Congress and to keep the Commission's findings at the top of the public's mind ahead of the 1950 midterms and the 1952 presidential election, in March 1949 a group of conservatives launched and generously financed the Citizens Committee for Reorganization of the Executive Branch of the Government.Footnote 118 The Citizens Committee nurtured public skepticism about domestic programs by fostering the impression of government incompetence in the domestic sphere. In a fundraising letter to the heads of top companies, Citizens Committee Campaign Chairman—and former Liberty Leaguer and NAM President—Colby Chester made clear the bottom-line benefits businesses would reap from the campaign: “The long-range value of an educated, tax-conscious, civically-alert public cannot be estimated in dollars and cents.”Footnote 119

Charles Coates moved over from the Hoover Commission staff to lead the Citizens Committee's public relations effort, which drew on and expanded the persuasion playbook developed by public relations professionals for the NAM. It was a big operation. A speaker's bureau supplied speakers for appearances around the country and equipped them with “startling facts”—most drawn from domestic programs—that underscored “the absurdities of poor [government] management.”Footnote 120 Advertising across all media, a touring exhibition, and a series of conferences reinforced this derisive way of talking about government.Footnote 121

The Citizens Committee also continued the conservative movement's efforts to shape young minds, sending materials to schools and universities and setting up student committees on campuses.Footnote 122 In addition to material for instructors to use in the classroom, the Citizens Committee offered a movie that provided “A colorful & dramatic picture of the work of the Hoover Commission…. The camera takes you to Washington for an intimate sightseeing tour of the sprawling government departments, bureaus, and agencies…. It takes you inside for a view of the people at work…. It reveals the obsolete equipment, the vast tangle of red tape … the overlapping and duplication.”Footnote 123 Material of this sort not only sowed doubt about the government's competence, it also reinforced wartime conservative messaging about the private sector's superiority. Like the NAM's earlier emphasis on students, the Citizens Committee's student work proved a shrewd investment in the conservative movement's future.

The Citizens Committee also continued the pattern of cultivating women, including by giving women prominent speaking roles at the National Reorganization Conference in December 1949. Oveta Culp Hobby, an influential conservative, set the tone for the conference in her opening speech.Footnote 124 The government, she said, had become “unwieldy and clumsy. Being so, it has become irksome and of decreasing service and satisfaction to the people.”Footnote 125 A subsequent speech, delivered by a person identifying herself as Mrs. Wesley C. Ahlgren, cleverly cast doubt on the government's competence. Ahlgren called her address “The Housewife's Point of View” and argued that the responsibilities of the housewife and the government were broadly similar but that the way the government went about the job left much to be desired. Ahlgren said she was “flabbergasted” to learn from the Hoover Report how incompetently the government did its job. She then provided some folksy examples.Footnote 126 “When you go marketing, you first look to see what is in the cupboard, and make your marketing list accordingly. Not so Uncle Sam. The Hoover Commission estimated that government supplies to a value of probably 29 billion dollars are stored in various offices and warehouses, with no complete inventory of them anywhere.”Footnote 127 She concluded that she “could continue indefinitely with examples of confusion, overlapping, and waste in our Federal Government that would produce some mighty unpleasant conversations around the dinner table if they had been duplicated, on a smaller scale, in our own homes.”Footnote 128

The Citizens Committee launched two large advertising campaigns to spread this selective message of government incompetence far and wide. The first campaign, the National Reorganization Crusade, began in 1950 and included robust print and radio components.Footnote 129 The Citizens Committee followed a simple formula in this campaign: emphasize the Hoover Commission's bipartisan credentials and then sow doubt about the government's competence by providing amusing examples—almost always from the domestic policy realm—of government “waste,” “red tape,” and “inefficiency.” One newspaper ad showed a puzzled farmer who received five different responses from five different agencies to a query he sent the government. Another provided a longer list of similar examples of government incompetence.Footnote 130 Radio programming highlighted examples of government “waste” and “inefficiency” in vivid terms. “Automobiles are clogging our streets, but Uncle Sam is still using horse-and-buggy methods,” said one ad.Footnote 131 “Twenty four administrators and supervisors for 25 workers,” declared another.Footnote 132 The radio content also continued the long-running conservative effort to increase “tax consciousness.”Footnote 133 “I know a business that's losing over 8 million dollars a day. It's your business … [the] Federal Government … your money being lost!”Footnote 134 Another radio spot reported that “If you are an average citizen, you work 47 days a year to support this good old Pandemonium on the Potomac known as your Federal Government.”Footnote 135

In 1951, the Citizens Committee persuaded the Ad Council to coordinate an even larger advertising campaign on behalf of the Hoover Report. Howard Chapin of General Foods coordinated the campaign. Leading advertising agency J. Walter Thompson prepared the ads.Footnote 136 Like the 1950 National Reorganization Crusade, the Ad Council campaign dramatized the Hoover Report's vivid accounting of government “waste” and “inefficiency” to sow doubts about domestic programs. A series of ads depicted Americans talking about government “boondoggles.” One trucker asks another, “Isn't that the load of government lumber I hauled down from Alaska a week ago?” “Yeah,” the other trucker replies, “I just got orders to haul it back again!”Footnote 137 In another ad, a woman and a man stand outside a new building. The man asks, “Isn't that new government hospital open yet?” The woman replies, “NO. They never even bothered to find out whether they could get enough doctors to staff it!”Footnote 138

Other ads nudged Americans toward a form of selective anti-statism by encouraging them to support spending for “national security” but to oppose spending for “welfare.” These ads accepted higher taxes to pay for physical security but provided vivid examples of why citizens should not want to pay for “wasteful,” “bungling” domestic programs. “Defense costs mean higher taxes—no one can help that. But no one wants to pay higher taxes for waste and inefficiency.”Footnote 139 The headline at the top of one ad declared, “Poor service at prohibitive cost is typical of many government agencies.”Footnote 140 Another ad compared public insurance programs unfavorably to private ones. Two men watch a woman walk down the street with her two children. The first man says to the other, “We ought to get together and do something for Mrs. Green!” The second man replies, “That's right! Bill died almost 3 months ago and his G.I. insurance hasn't come through yet.”Footnote 141 The ad noted that “private insurance companies settle most death claims within 15 days.”Footnote 142

President Truman understood what conservatives were doing, found it infuriating, and tried to push back. Conservatives, Truman told the National Civil Service League in a feisty speech on May 2, 1952:

Know that they cannot persuade the people to give up the gains of the last 20 years. But they think they can undermine those gains by attacking the men and women who have the job of carrying out the programs of the Government. And so they have launched a campaign to make people think that the Government service as a whole is lazy, inefficient, corrupt, and even disloyal.Footnote 143

Truman thundered that “there is no more cancerous, no more corrosive, no more subversive attack upon the great task of our Government today, than that which seeks to undermine confidence in Government.”Footnote 144 Truman was not just pandering to his audience. His superheated rhetoric reflected anger at conservatives’ success in undermining public support for his efforts to address lingering socioeconomic problems through domestic policy.Footnote 145

Conservatives had attacked domestic programs as wasteful and inefficient since the 1920s, but the public could dismiss these critiques as self-interested or partisan when they came directly from organizations known to be run by wealthy business executives. The National Association of Manufacturers’ use of indirect persuasion via “opinion molders” helped make these criticisms stick. So did the Ad Council's delivery of conservative messaging through “non-partisan public service advertising.” By making a sport out of highlighting examples of domestic policy ineptitude and fostering the impression that such ineptitude was widespread, the Ad Council's “public service advertising” cemented a derisive way of talking about domestic programs that contributed to the growth of a strand of selective anti-statism that embraced “national security” spending but resisted “welfare” spending. Even before the onset of the cold war in March 1947 re-opened the taps of military spending, Truman's budget requests began to reflect this selective anti-statism. When he presented his 1948 budget request to the Republican-controlled Congress in January 1947, Truman asked for nearly ten times more money for the military and international initiatives than for domestic programs to address domestic problems—a disparity that persisted through the end of Truman's presidency.Footnote 146

Consequences

As a prominent citizen in the 1950s and a politician beginning in the 1960s, Ronald Reagan embodied the strand of selective anti-statism that opposed domestic economic security programs but supported “national security” spending. Testifying before the House Ways and Means Committee in 1958, Reagan emphasized his support—and the motion picture industry's support—for defense spending but pressed for “an across-the-board percentage cut” in the government's other programs.Footnote 147 In his role as a General Electric spokesperson in the 1950s and then as a professional politician beginning in the 1960s, Reagan followed the approach honed by the conservative persuasion campaign since the 1920s, peppering his speeches with “startling facts” belittling domestic programs to build support for this selective anti-statism.Footnote 148 The 1964 speech “A Time for Choosing” that launched Reagan's national political career epitomized the approach.Footnote 149 In the speech, Reagan wove together amusing examples of domestic policy incompetence—a three-year-old, $1.5 million building in Cleveland demolished by government planners! Youth training programs that cost more per year than Harvard tuition!—into a coherent narrative supporting his assertion that “government does nothing as well or as economically as the private sector.”Footnote 150 “There's been an increase in the [number of] Department of Agriculture employees,” Reagan told the audience. “There's now one for every 30 farms in the United States, and still they can't tell us how 66 shiploads of grain headed for Austria disappeared without a trace.”Footnote 151 The conservative audience laughed.Footnote 152

By the time the upheavals of the 1970s might have led even Americans who did not identify as conservative to doubt the government's domestic policy competence, the conservative persuasion campaign had spent decades and millions of dollars using repeated messaging to prime Americans to see domestic programs in a negative light.Footnote 153 To the many Americans who had received this conservative message unwittingly for years and who were looking for an explanation for the country's recent troubles, the domestic policy incompetence message rang true—and not just among conservatives and Republicans. Three years before Ronald Reagan told Americans in his first inaugural address that “government is the problem,” President Jimmy Carter declared flatly in his 1978 State of the Union address that “Government cannot solve our problems.”Footnote 154 Bill Clinton's presidency continued the Democratic Party's turn away from using domestic policy to address domestic problems.Footnote 155 By 2021, even many self-identified liberals and progressives considered the government less competent than the private sector.Footnote 156 Low regard for domestic policy and the strand of selective anti-statism to which this sentiment contributed had crossed party lines and become defining features of American politics.

The conservative persuasion campaign's reach, indirect influence, and repetition of messages disparaging domestic programs contributed much to its success. But the campaign also benefited from two features of the American political system that have often left domestic programs with few defenders. Americans generally have a low level of knowledge of what the government does and are often oblivious, sometimes by design, to the ways in which they benefit from domestic programs.Footnote 157 And Americans’ elected representatives in Congress have an interest in the public perceiving the government as incompetent domestically because that perception enables elected officials to present themselves as essential troubleshooters for constituents.Footnote 158 These two features of the American political system left the field open for those who wanted the public to hold domestic policy in low regard to spread their message largely unopposed.

Viewed as a whole, the conservative persuasion campaign launched in the 1920s must be taken seriously by anyone who wants to understand American political development thereafter. And so, more broadly, must any big efforts to shape public opinion that achieved similarly high levels of reach and repetition.Footnote 159 The champions of limited government lacked a widely shared rhetoric with which to diminish public support for domestic state building prior to this campaign. With the introduction of rhetoric belittling domestic programs, the conservative persuasion campaign supplied that shared rhetoric, helping conservatives coalesce into an effective movement and then—through the campaign's reach, indirect influence via “opinion molders” and “public service advertising,” and use of repetition—helping the conservative movement grow and priming many Americans to embrace a strand of selective anti-statism that became a defining feature of post–World War II American politics.

Under this selective anti-statism, many Americans supported the creation of robust state capacity in the military and foreign policy realms but resisted comparable efforts to build the government's capacity to address domestic problems through domestic policy. Ironic consequences followed. While conservatives succeeded in slowing and constraining domestic state-building—it took more than twenty years for liberals to build on the foundation Roosevelt laid, and even the Great Society programs of the 1960s were more limited than they might have been—the imbalanced state that emerged still proved far larger than the conservative persuasion campaign's original architects envisioned.Footnote 160 The reduction in public confidence in domestic policy long sought by conservatives also proved costly. Without public support to create sufficient capacity to address domestic problems with domestic policy, politicians at times turned to the military and foreign policy to try to solve domestic problems—at great cost to the United States and the world.