Meditation has been studied extensively over the past decades (Goleman & Davidson, Reference Goleman and Davidson2017). While mindfulness meditation (i.e. practices designed to cultivate non-judgmental, present-moment awareness) has become the most studied type of meditation (Davidson & Dahl, Reference Davidson and Dahl2018), there is also an emerging body of research on loving-kindness meditation and other similar practices (e.g. compassion meditation) that involve the cultivation of positive emotions toward oneself and others (Graser & Stangier, Reference Graser and Stangier2018). These two groups of meditation practices target different psychological processes (Singer & Engert, Reference Singer and Engert2019) and yet both seem to have positive effects on mental health (Galante, Galante, Bekkers, & Gallacher, Reference Galante, Galante, Bekkers and Gallacher2014; Goldberg, Riordan, Sun, & Davidson, Reference Goldberg, Riordan, Sun and Davidson2022), which is a commonly reported motivation for meditation practice (Jiwani, Lam, Davidson, & Goldberg, Reference Jiwani, Lam, Davidson and Goldberg2022). Previous research suggests that the amount of practice time can have a small but significant impact on outcomes (Parsons, Crane, Parsons, Fjorback, & Kuyken, Reference Parsons, Crane, Parsons, Fjorback and Kuyken2017), but there are many psychological barriers (e.g. low perceived benefit) that can come in the way of regular meditation practice (Hunt, Hoffman, Mohr, & Williams, Reference Hunt, Hoffman, Mohr and Williams2020). It is therefore important to investigate adjunctive interventions to support and encourage meditation practice.

While certain non-pharmacological interventions have shown promise as a way to support meditation practice (e.g. neurofeedback; Hunkin, King, and Zajac, Reference Hunkin, King and Zajac2021), recent research suggests that pharmacological interventions such as psychedelics may also support meditation practice. For example, in a randomized placebo-controlled trial, psilocybin administration was found to increase meditation depth among experienced meditators who participated in a mindfulness mediation retreat (Smigielski et al., Reference Smigielski, Kometer, Scheidegger, Krähenmann, Huber and Vollenweider2019; see also Griffiths et al., Reference Griffiths, Johnson, Richards, Richards, Jesse, MacLean and Klinedinst2018). Another study found that lifetime psychedelic use was associated with more days of mindfulness meditation practice in the past week in a representative sample of the US adult population (Simonsson et al., Reference Simonsson, Chambers, Hendricks, Goldberg, Osika, Schlosser and Simonsson2023a). No association was observed between lifetime psychedelic use and number of days of loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice in the past week (Simonsson et al., Reference Simonsson, Chambers, Hendricks, Goldberg, Osika, Schlosser and Simonsson2023a; see also Simonsson & Goldberg, Reference Simonsson and Goldberg2023), but it is possible that a larger sample would be needed to observe significant associations in less common practices such as loving-kindness or compassion meditation. Notably, the subjective experience of insight (i.e. psychological insight) during respondents' most insightful psychedelic experience was associated with more days of both mindfulness meditation practice and loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice in the past week (Simonsson et al., Reference Simonsson, Chambers, Hendricks, Goldberg, Osika, Schlosser and Simonsson2023a). It has been hypothesized that psychedelic experiences may increase the motivation to practice meditation and ultimately lead to more engagement with meditation practice (Payne, Chambers, & Liknaitzky, Reference Payne, Chambers and Liknaitzky2021), which would be important to test in longitudinal studies.

Other research also indicates that meditation practice might influence the acute psychedelic experience. For instance, results from a thematic analysis of responses among naturalistic users of psychedelics indicate that meditation practice may be helpful in preparation for the psychedelic experience (Azmoodeh, Thomas, & Kamboj, Reference Azmoodeh, Thomas and Kamboj2023). Another study found that trying to calm the mind was the most commonly reported helpful intervention during respondents' most challenging, difficult, or distressing experience using a psychedelic (Simonsson, Hendricks, Chambers, Osika, & Goldberg, Reference Simonsson, Hendricks, Chambers, Osika and Goldberg2023b; see also Carbonaro et al., Reference Carbonaro, Bradstreet, Barrett, MacLean, Jesse, Johnson and Griffiths2016). Such findings suggest that meditation practice (e.g. mindfulness meditation, loving-kindness or compassion meditation) before or during the acute psychedelic experience could potentially reduce the likelihood and length of psychologically difficult states.

While psychedelics have shown promise as a way to support meditation practice (and vice versa), the data to support this contention are limited. Using a longitudinal observational research design with samples representative of the US and UK adult populations with regard to sex, age, and ethnicity (N = 9732), we investigated potential associations between self-reported psychedelic use and meditation practice. We hypothesized that respondents who reported psychedelic use during the 2-month study period would have a greater increase in the number of days of mindfulness meditation practice and loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice in the past week than respondents who did not report psychedelic use in the study period. We conducted exploratory analyses to investigate whether greater psychological insight during respondents' most intense psychedelic experience in the same time period was associated with increases in the number of days of mindfulness meditation practice and loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice in the past week. We also conducted exploratory analyses to investigate whether more days of mindfulness meditation practice and loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice in the past week at baseline would be associated with less severe challenging psychedelic experiences during the study period.

Method

Participants

The study (hypotheses, design plan, sampling plan, variables, and analysis plan) was preregistered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/e28c9 (see online Supplemental Materials for power analysis). The exploratory analyses were not preregistered. US (N = 4867) and UK (N = 4865) residents (18 years or older) were recruited on Prolific Academic (https://app.prolific.co). We used Prolific Academic's representativeness function to stratify the samples across sex (Male, Female), age (18–27, 28–37, 38–47, 48–57, 58+), and ethnicity (White, Mixed, Asian, Black, Other) to reflect the demographic distribution of the US and UK adult populations. The study description in recruitment materials did not mention psychedelic use (see online Supplemental Materials for recruitment materials) to avoid self-selection bias.

Materials and procedure

In August 2022, respondents were asked to complete the baseline survey (T1), which included items related to demographic characteristics, substance use, psychedelic use, and meditation practice. Approximately 2 months later (October 2022), respondents were invited to complete the follow-up survey, which included items related to substance use, psychedelic use, and meditation practice. This study was part of a larger survey and completion of the baseline survey (Md = 8.7 min) resulted in £0.9 payment and completion of the follow-up survey (Md = 6.6 min) resulted in £0.9 payment. Study procedures were determined to be exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin – Madison.

Measures

Demographics

At T1, all respondents were asked to report age, gender identity, educational attainment, religious belief, and political affiliation.

Substance use

At T1, all respondents were asked to report which, if any, of the following substances they had ever used: alcohol, nicotine products (e.g. cigarettes, e-cigarettes, cigarillos, little cigars, smokeless tobacco), cannabis products (e.g. weed, THC, CBD, hemp oil), MDMA, major stimulants (e.g. cocaine, methamphetamine), illicit narcotic analgesics/opioids (e.g. morphine, heroin, oxycodone), illicit benzodiazepines and barbiturates (e.g. Valium, Alprazolam [Xanax]), inhalants (poppers, whip-its, nitrous oxide, glue), and other substances. At follow-up, all respondents were asked to report which, if any, of the same substances they had used in the past 2 months (i.e. in the time between T1 and T2).

Psychedelic use

At T1, all respondents were asked to report which, if any, of the following psychedelics they had ever used: ayahuasca, N, N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), mescaline, peyote, San Pedro, and psilocybin. If respondents reported use of any psychedelic, they were asked if they had used them in the past 2 months. At T2, all respondents were asked to report which, if any, psychedelics they had used in the past 2 months (i.e. in the time between T1 and T2). If respondents reported use of any psychedelic during the 2-month study period, they were asked to report the dose (low, moderate, large, very large, extreme) used during their most intense psychedelic experience in the same time period. Those respondents who reported use of any psychedelic during the study period were also asked to look back on their most intense psychedelic experience in that time and complete the Psychological Insight Questionnaire (PIQ; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Barrett, So, Gukasyan, Swift and Griffiths2021), which was designed to capture the subjective experience of insight during the acute psychedelic experience. The responses were rated on a 0- (‘No, not at all’) to 5-point (‘Extremely (more than ever before in my life)’) Likert scale. Total PIQ score was calculated as the average of all items. The internal consistency was excellent (alpha = 0.97 using unimputed sample at T2). Those respondents who reported use of any psychedelic during the study period were further asked to look back on their most intense psychedelic experience in that time and complete the Challenging Experiences Questionnaire (CEQ; Barrett, Bradstreet, Leoutsakos, Johnson, and Griffiths, Reference Barrett, Bradstreet, Leoutsakos, Johnson and Griffiths2016), which was designed to capture psychologically difficult states (i.e. ‘bad trips’) during the acute psychedelic experience (i.e. grief, fear, death, insanity, isolation, physical distress, paranoia). The responses were rated on a 0- (‘None; not at all’) to 5-point (‘Extreme’) Likert scale. Total CEQ score was calculated as the average of all items. The internal consistency was excellent (alpha = 0.97 using unimputed sample at T2).

Mindfulness meditation

At T1, all respondents were asked to report whether they had ever tried mindfulness meditation, including Vipassana, Zen Buddhist meditation, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy. If respondents reported having tried mindfulness meditation, they were asked to estimate their total lifetime number of hours of mindfulness meditation practice (1 = 0–10, 2 = 11–100, 3 = 101–500, 4 = 501–1000, 5 = 1001–5000, 6 = 5001 + ). Those who reported having tried mindfulness meditation were also asked to report on how many days they engaged with mindfulness meditation over the past week (0–7). If respondents reported not having tried mindfulness meditation, they were coded as 0 days. At T2, all respondents were asked to report on how many days they engaged with mindfulness meditation over the past week (0–7). The reason for using the past-week reference for mindfulness meditation was to maximize the likelihood of capturing post-psychedelic changes in mindfulness meditation practice – it was assumed that most psychedelic use during the study would have occurred prior to T2 minus seven days for most participants.

Loving-kindness or compassion meditation

At T1, all respondents were asked to report whether they had ever tried loving-kindness or compassion meditation, including Metta, Compassion Cultivation Training, and Cognitively-Based Compassion Training. If respondents reported having tried loving-kindness or compassion meditation, they were asked to estimate their total lifetime number of hours of loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice (1 = 0–10, 2 = 11–100, 3 = 101–500, 4 = 501–1000, 5 = 1001–5000, 6 = 5001 + ). Those who reported having tried loving-kindness or compassion meditation were also asked to report on how many days they engaged with loving-kindness or compassion meditation over the past week (0–7). If respondents reported not having tried loving-kindness or compassion meditation, they were coded as 0 days. At T2, all respondents were asked to report on how many days they engaged with loving-kindness or compassion meditation over the past week (0–7). The reason for using the past-week reference for loving-kindness or compassion meditation was the same as for mindfulness meditation, which is described above.

Statistical analyses

As specified in the preregistration, we used multiple linear regression to assess whether there were significant differences in past 7 days practice of mindfulness meditation change scores between those who reported psychedelic use in the 2-month study period versus those who did not, controlling for age (recoded as: 18–27, 28–37, 38–47, 48–57, 58+), gender (recoded as: male, female, other), educational attainment (Bachelor's degree or higher, no Bachelor's degree), degree of religiosity (not at all religious, a little religious, moderately religious, quite religious, very religious), political affiliation (Democratic Party or Republican Party for US respondents; Remain side or Leave side for UK respondents), past 2 month use of alcohol, nicotine products, cannabis products, MDMA, major stimulants, illicit narcotic analgesics/opioids, illicit benzodiazepines and barbiturates, inhalants, and other substances at T2 (all substances entered as separate covariates), and psychedelic use in the past 2 months at T1. Equivalent models were run focusing on loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice. The control variables were preregistered and chosen based on a previous longitudinal study on psychedelic use (Forstmann, Yudkin, Prosser, Heller, & Crockett, Reference Forstmann, Yudkin, Prosser, Heller and Crockett2020). Sensitivity analyses were conducted using zero-inflated negative binomial models.

In exploratory analyses, we conducted additional multiple linear regression models among those who reported psychedelic use during the 2-month study period. First, we assessed whether greater psychological insight during respondents' most intense psychedelic experience during the study period was associated with past 7 days practice of mindfulness meditation change scores, controlling for age (recoded as: 18–27, 28–37, 38–47, 48–57, 58+), gender (recoded as: male, female, other), educational attainment (Bachelor's degree or higher, no Bachelor's degree), degree of religiosity (not at all religious, a little religious, moderately religious, quite religious, very religious), political affiliation (Democratic Party or Republican Party for US respondents; Remain side or Leave side for UK respondents), past 2 month use of alcohol, nicotine products, cannabis products, MDMA, major stimulants, illicit narcotic analgesics/opioids, illicit benzodiazepines and barbiturates, inhalants, and other substances at T2 (all substances entered as separate covariates), dose used during respondents' most intense psychedelic experience during the study period, and psychedelic use in the past 2 months at T1. Equivalent models were run focusing on loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice. Second, we assessed whether past 7 days practice of mindfulness meditation at T1 was associated with less severe challenging psychedelic experiences during the 2-month study period, controlling for age (recoded as: 18–27, 28–37, 38–47, 48–57, 58+), gender (recoded as: male, female, other), educational attainment (Bachelor's degree or higher, no Bachelor's degree), degree of religiosity (not at all religious, a little religious, moderately religious, quite religious, very religious), political affiliation (Democratic Party or Republican Party for US respondents; Remain side or Leave side for UK respondents), lifetime use of psychedelics, alcohol, nicotine products, cannabis products, MDMA, major stimulants, illicit narcotic analgesics/opioids, illicit benzodiazepines and barbiturates, inhalants, and other substances (all substances entered as separate covariates), dose used during respondents' most intense psychedelic experience during the study period, and lifetime hours of mindfulness meditation practice. Equivalent models were run focusing on loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice.

For all analyses, p values are reported with three decimal places, allowing the reader to estimate any p value corrections of the reader's choosing. There were no missing data at T1. Missing data at T2 was addressed by using Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE; Van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, Reference Van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn2011). The MICE package version 3.15.0 in R Studio (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mice/index.html) was used to impute the missing data twenty times using random forest imputations as method. We subsequently replaced imputed values on hierarchical variables (i.e. variables that should have missing data by design) before we analyzed the data. Model were run across imputations and pooled according to Rubin's (Reference Rubin1976) rules using the ‘pool’ function in the ‘mice’ package.

Results

7667 respondents completed the follow-up survey (79% retention rate) and 100 respondents (1.3% of follow-up survey completers) reported psychedelic use during the 2-month study period (see online Supplemental Tables S1 for descriptive statistics of psychedelic-related variables).

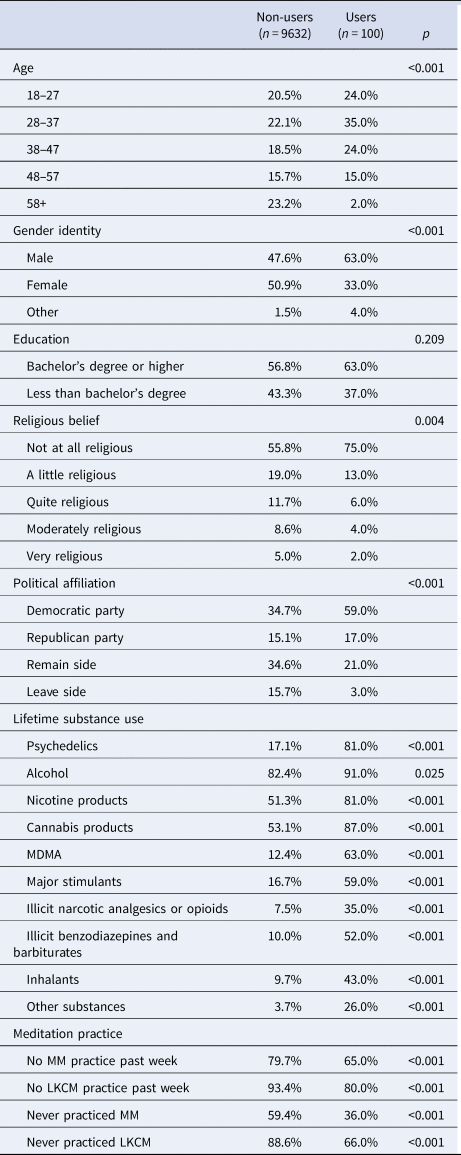

Table 1 shows sample characteristics. As shown in the table, among those who reported psychedelic use during the study period, 36 percent had never tried mindfulness meditation before the start of the study and 66 percent had never tried loving-kindness or compassion meditation before the start of the study, which was significantly lower than those who did not report using psychedelics during the same time period (59 and 89 percent, respectively; see online Supplemental Table S2 for descriptive statistics of meditation-related variables).

Table 1. Sample characteristics at baseline

Note: This table shows sample characteristics at baseline of respondents who did not report psychedelic use during the study period (i.e. non-users) and respondents who did (i.e. users). MM, mindfulness meditation; LKCM, loving-kindness or compassion meditation; all percentages were rounded to the nearest 0.1%; cumulative percentages may not add to 100.0. Pearson's χ2 tests were used to examine the characteristics of users v. non-users.

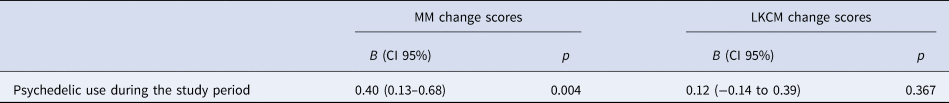

Table 2 displays results from the multiple regression models testing the associations between psychedelic use and meditation practice. As indicated in the table, psychedelic use during the 2-month study period was associated with increases in the number of days of mindfulness (but not loving-kindness or compassion) meditation practice in the past week. Sensitivity analyses showed broadly the same results.

Table 2. Psychedelic use during the study period predicting past-week meditation practice change scores

Note: This table shows two separate multiple linear regression models using multiple imputation (imputed n = 9732). B, unstandardized regression coefficient; MM, Past 7 days practice of mindfulness meditation; LKCM, Past 7 days practice of loving-kindness or compassion meditation. The regression models controlled for age, gender, educational attainment, degree of religiosity, political affiliation, past 2 month use of alcohol, nicotine products, cannabis products, MDMA, major stimulants, illicit narcotic analgesics/opioids, illicit benzodiazepines and barbiturates, inhalants, and other substances at T2, and psychedelic use in the past 2 months at T1. See online Supplemental Table S4 for additional statistics.

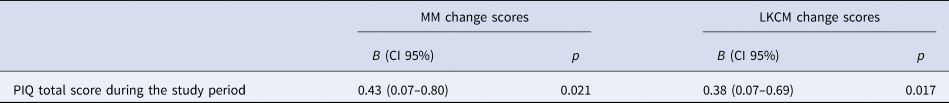

Table 3 displays results from the multiple regression models testing the associations between psychological insight and meditation practice. As indicated in the table, among those who reported psychedelic use during the study period, psychological insight during respondents' most intense psychedelic experience in that time was associated with increases in the number of days of mindfulness and loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice in the past week.

Table 3. PIQ total score during the study period predicting past-week meditation practice change scores

Note: This table shows two separate multiple linear regression models (n = 100). B, unstandardized regression coefficient; MM, Past 7 days practice of mindfulness meditation; LKCM, Past 7 days practice of loving-kindness or compassion meditation; PIQ, Psychological Insight Questionnaire. The regression models controlled for age, gender, educational attainment, degree of religiosity, political affiliation, past 2 month use of alcohol, nicotine products, cannabis products, MDMA, major stimulants, illicit narcotic analgesics/opioids, illicit benzodiazepines and barbiturates, inhalants, and other substances at T2, dose used during respondents' most intense psychedelic experience during the study period, and psychedelic use in the past 2 months at T1. See online Supplemental Table S5 for additional statistics.

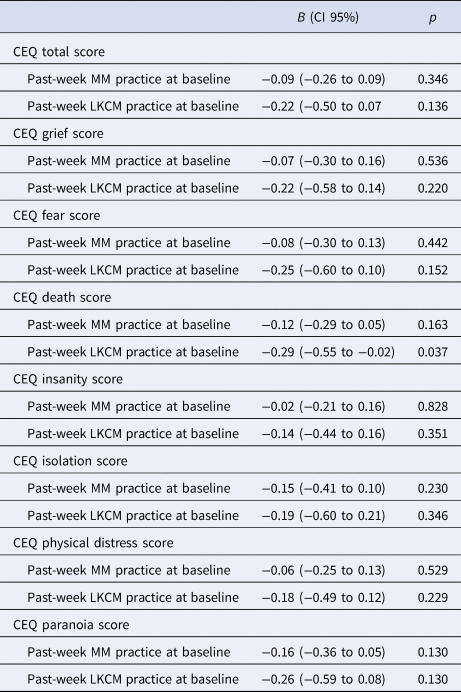

Table 4 displays results from the multiple regression models testing the associations between meditation practice at T1 and the severity of challenging psychedelic experiences during the 2-month study period. As indicated in the table, among those who reported psychedelic use during the study period, more days of loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice in the past week at baseline was associated with less severe subjective feelings of death or dying during respondents' most intense psychedelic experience in the study period, though no other associations were observed between meditation practice and the severity of challenging psychedelic experiences.

Table 4. Past-week meditation practice at baseline predicting CEQ scores during the study period

Note: This table shows sixteen separate multiple linear regression models (n = 100). B, unstandardized regression coefficient; CEQ, Challenging Experience Questionnaire; MM, mindfulness meditation; LKCM, loving-kindness or compassion meditation. The regression models controlled for age, gender, educational attainment, degree of religiosity, political affiliation, lifetime use of psychedelics, alcohol, nicotine products, cannabis products, MDMA, major stimulants, illicit narcotic analgesics/opioids, illicit benzodiazepines and barbiturates, inhalants, and other substances at T1, and dose used during respondents' most intense psychedelic experience during the study period. The regression models with mindfulness meditation as independent variable also controlled for lifetime hours of mindfulness meditation practice. The regression models with loving-kindness or compassion meditation as independent variable also controlled for lifetime hours of loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice. See online Supplemental Table S6 for additional statistics.

Discussion

This longitudinal observational study investigated potential associations between self-reported psychedelic use and meditation practice. As hypothesized, psychedelic use during the 2-month study period was associated with greater increases in the number of days of mindfulness meditation practice in the past week. Contrary to our hypothesis, however, no association was observed between psychedelic use in the same time period and changes in the number of days of loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice in the past week. In exploratory analyses, psychological insight during respondents' most intense psychedelic experience during the study period was associated with greater increases in the number of days of mindfulness and loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice in the past week. Notably, more days of loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice in the past week at baseline was associated with less severe subjective feelings of death or dying during respondents' most intense psychedelic experience in the study period, though no other associations were observed between meditation practice and the severity of challenging psychedelic experiences. Taken together, these findings indicate that psychedelic use might lead to greater engagement with meditation practices such as mindfulness meditation, while meditation practices such as loving-kindness or compassion medication might buffer against certain challenging experiences associated with psychedelic use.

If the significant findings in this study are replicated in future studies, it would be important to understand the mechanisms underlying the relationships between psychedelic experiences and meditation practices. For example, a recent cross-sectional study found an association between lifetime psychedelic use and lower likelihood of overall perceived barriers to meditation practice (Simonsson & Goldberg, Reference Simonsson and Goldberg2023). Such findings provide the basis for one potential path model: psychedelic experience → decreased perceived barriers to meditation practice → increased meditation practice (Payne et al., Reference Payne, Chambers and Liknaitzky2021). It is possible, for instance, that psychedelics can induce a transient, subjective experience of non-judgmental, present-moment awareness, which could provide a point of reference to orient future mindfulness meditation practice. This may reduce confusion around how to practice mindfulness meditation (i.e. perceived inadequate knowledge) and lead to increased motivation and engagement. It is similarly possible that a psychedelic-induced experience of non-judgmental, present-moment awareness might increase the perceived benefit of practices that cultivate trait mindfulness (e.g. mindfulness meditation; Payne et al., Reference Payne, Chambers and Liknaitzky2021). Another possibility, partially supported by findings in this study, is that the subjective experience of insight during the acute psychedelic experience might lead to greater awareness of unhelpful thinking and behavioral patterns that hinder meditation practice (i.e. perceived pragmatic barriers). Future research should explore these possibilities.

The absence of a significant association between psychedelic use during the study period and changes in the number of days of loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice in the past week corresponds with previous research (Simonsson et al., Reference Simonsson, Chambers, Hendricks, Goldberg, Osika, Schlosser and Simonsson2023a). Although it is possible that a larger sample would be needed to observe significant associations in less common practices such as loving-kindness or compassion meditation, another explanation could be that psychedelics do not reliably induce experiences that are phenomenologically similar to loving-kindness or compassion meditation, which might otherwise provide a point of reference to orient future loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice or increase the perceived benefit of practices that cultivate positive emotions toward oneself and others. If the phenomenological similarity does indeed matter, it may be worthwhile for future studies to investigate whether the number of days of loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice in the past week could be influenced by experiences with MDMA, which has been associated with positive emotions toward oneself and others (Lyubomirsky, Reference Lyubomirsky2022).

Notably, among those who reported psychedelic use during the 2-month study period, more days of loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice in the past week at baseline was associated with less severe subjective feelings of death or dying during respondents' most intense psychedelic experience in the study period, though no other associations were observed between meditation practice and the severity of challenging psychedelic experiences. Previous research suggests that loving-kindness or compassion meditation practices may have a stronger dose-response relation with positive emotions than mindfulness meditation (Fredrickson et al., Reference Fredrickson, Boulton, Firestine, Van Cappellen, Algoe, Brantley and Salzberg2017). It is therefore plausible that the positive emotions cultivated through loving-kindness or compassion meditation practices might act as internal psychological support during challenging psychedelic experiences and thereby buffer against, for example, subjective feelings of death or dying during a psychedelic experience. This hypothesis should be tested in future research.

The findings in this study have at least two potential implications. First, previous research suggests that greater amount of mindfulness meditation practice may have small but significant effects on outcomes (e.g. depression, anxiety, stress; Parsons et al., Reference Parsons, Crane, Parsons, Fjorback and Kuyken2017), but it is still common for participants to discontinue treatment with mindfulness-based interventions (Lam, Kirvin-Quamme, & Goldberg, Reference Lam, Kirvin-Quamme and Goldberg2022; Lam, Riordan, Simonsson, Davidson, & Goldberg, Reference Lam, Riordan, Simonsson, Davidson and Goldberg2023; Nam & Toneatto, Reference Nam and Toneatto2016). The association between psychedelic use during the 2-month study period and increases in the number of days of mindfulness meditation practice in the past week could therefore have implications for mindfulness-based interventions. If psychedelic use, in fact, increases persistence with mindfulness meditation practice, psychedelic administration could be leveraged to support the maintenance of such practice, especially in populations that have been shown to benefit from mindfulness-based interventions (e.g. individuals with recurrent depression; Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Warren, Taylor, Whalley, Crane, Bondolfi and Dalgleish2016). Second, because subjective feelings of death or dying during a psychedelic experience have been associated with a retrospective, self-reported decrease in wellbeing (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Bradstreet, Leoutsakos, Johnson and Griffiths2016), the association between more days of loving-kindness or compassion meditation practice in the past week at baseline and less severe subjective feelings of death or dying during respondents' most intense psychedelic experience in the study period suggests that these types of practices could be useful tools in preparation for the acute psychedelic experience.

Limitations

Despite the promising results in this study, it is important to consider limitations when interpreting the findings. First, the recruited sample was stratified across sex, age and ethnicity to reflect the US and UK adult populations, but it might not have been representative on other variables such as income or educational attainment. Second, the covariate-adjusted regression models in this study controlled for only a subset of potential confounders. It is still possible that unmeasured confounding variables could have influenced the results (e.g. personality, mental health motivations). Third, the retention rate at follow-up was 79%. It is therefore possible that the results were influenced by attrition bias. Although we used multiple imputation, which is robust to data missing at random (i.e. missingness conditional on observed variables), it is possible that data were missing not at random (i.e. nonignorable missingness that is not recaptured with observed values; Graham, Reference Graham2009). Fourth, all variables were measured using self-report and respondents were asked to describe past meditation practice and psychedelic use retrospectively, which may have biased responses. Fifth, in the baseline survey, only those who reported having tried meditation were asked to report on how many days they engaged with meditation over the past week, whereas in the follow-up survey, all respondents were asked to report on how many days they engaged with meditation over the past week, which may have biased responses. Sixth, none of the significant results from the exploratory analyses would have survived Bonferroni-type correction for multiple comparisons. These results should therefore be interpreted with particular caution until replicated in future studies. Seventh, no conclusive causal inferences can be made due to the observational study design. Future studies should utilize randomized controlled research designs to evaluate the potential relationships between psychedelic experiences and meditation practices.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291723003082

Funding statement

OS was supported by Ekhaga Foundation and Olle Engkvist Foundation. SG was supported by a grant (K23AT010879) from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Support for this research was also provided by the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Public Health, Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development (FORMAS; FR-2018–0006; FR-2018-00246), Forte (2020-00977), and the University of Wisconsin - Madison Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and with funding from the Wisconsin Center for Education Research.

Competing interests

PSH has been in paid advisory relationships with the following organizations regarding the development of psychedelics and related compounds: Bright Minds Biosciences Ltd., Eleusis Benefit Corporation, Journey Colab Corporation, Reset Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Silo Pharma. OS was a co-founder of Eudelics AB.

Ethical standards

Study procedures were determined to be exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin – Madison. All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained digitally from all individual participants included in the study.

Availability of data and materials

The data and R script are available at the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/95smp/files/osfstorage.