The holy grail for many comparative scholars has been a definitive list of which parties conform to the definition of populism. This quest has been largely driven by the quantitative and electoral growth of European populist parties, their increasing impact on politics and participation in national governments and in the European Union (EU), and by interest in their Eurosceptic agendas. Despite their increased prominence, it is notable that works which offered comprehensive lists were more frequent when such parties were rarer and more marginal (Ignazi, Reference Ignazi1992; Betz Reference Betz1994; Taggart, Reference Taggart1995). In more recent years, such efforts have been somewhat less common (but see Mudde, Reference Mudde2007; Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg2011; van Kessel, Reference van Kessel2015; Zulianello, Reference Zulianello2020).

Lately, this gap has been filled by ‘The PopuList’ (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, de Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019), which has aimed to pool research expertise to provide an authoritative listing of populist, far right, far left, and Eurosceptic parties across Europe. The PopuList is an international scholarly project that has used expert judgements by over 80 academics across a range of countries to assess which parties could be regarded as populist. It has aimed to be comprehensive and to cover all parties that have gained at least one seat or 2% of the vote in general elections since 1989, moving a first step towards their assessment over time. The project has ultimately provided a nominal classification allowing for the production of a data set that can then be applied in a quantitative manner. The PopuList draws on the ideational approach to define populism (Mudde, Reference Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017) – seeing populism as having a core set of ideas emphasizing ‘the people’ and considering it the linchpin of any rightful political goal and decision; criticizing ‘the elite’; and capitalizing on a sense of (real or perceived) crisis (Taggart, Reference Taggart2000; Mudde, Reference Mudde2004; Rooduijn, Reference Rooduijn2014), rather than as a strategic phenomenon or one that is fundamentally malleable (Rovira Kaltwasser et al., Reference Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Carlin, Littvay and Rovira Kaltwasser2018).

The collaborative research effort of The PopuList has taken place amid increasing interest in the measurement of party-based populism (Polk et al., Reference Polk, Rovny, Bakker, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Koedam, Kostelka, Marks, Schumacher, Steenbergen, Vachudova and Zilovic2017; Engler et al., Reference Engler, Pytlas and Deegan-Krause2019; Norris, Reference Norris2020; Meijers and Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021).Footnote 1 A growing number of expert survey projects have been concerned with measuring the degree of populism and its latent aspects. With the 2014 wave, the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) started measuring parties' anti-elitism and anti-corruption salience (Polk et al., Reference Polk, Rovny, Bakker, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Koedam, Kostelka, Marks, Schumacher, Steenbergen, Vachudova and Zilovic2017) – that is, some of the dimensions subsumed under the concept of populism (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004). In the following wave, the CHES team expanded the list of questions so as to account for party positions on ‘people-centredness’, with which experts were asked to locate parties on a ‘direct vs. representative democracy’ dimension. The Populism and Political Parties Expert Survey (POPPA) has tried to unpack populism further as a concept ‘constituted by multiple related but distinct dimensions’ (Meijers and Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021: 373), arguing that measures should also consider the issues advanced by individual parties and, thus, address the constitutive ideological elements of their populism. Sitting somewhere between the broad-ranging scope of CHES and the specialist focus of POPPA, the Global Party Survey ambitiously sought to combine several aspects and capture party policy positions and their populism across the globe (Norris, Reference Norris2020). These studies are clearly contributing to the development of quantitative measures of party-based populism.

Art (Reference Art2020) has recently written about the over-use of populism and provides a powerful critique of some of the trends towards generalization. His argument is that what is currently characterized as a populist wave is better viewed as nativism and is linked to immigration politics. The emergence of left-wing populism in Europe has, he argues, waned and support for other populists seems rooted in nativism and authoritarianism. However, we suggest that there is nothing exclusive about identifying parties as populist and, given the thin-centred nature of populism, it is indeed often useful to analyse populist parties under different categorizations.

Our contribution adopts The PopuList's crisp logic for classification and focuses in depth on the ideology, electoral performance, and participation in government of populist parties in Europe. The aspiration here is to link the data presented on parties identified as populist to their national context through substantial qualitative assessments (see Appendix) and present a comparative overview spanning different aspects. We conceive our data as a resource on the state of European populist parties before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, which complements and expands upon The PopuList in two major respects: differentiation and description. In our contribution, we hold time constant and look at only one year (2019) to allow a standardized cross-country comparison across various dimensions. In terms of the ideology of these parties, this allows us to expand the ideological range used by The PopuList (far left, far right, or neither of the two) to include other positions along the left–right axis.Footnote 2 From the ideational perspective, to which our work subscribes (Mudde, Reference Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017), we thus respond to the mounting concerns on the obfuscation of populism's ‘ideological companions’ (Art, Reference Art2020). By looking at the whole set of populist parties in Europe and unpacking their ideological features, we explicitly acknowledge the role exerted, for example, by nativism (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007), democratic socialism (March, Reference March2011), or reformism (Hanley and Sikk, Reference Hanley and Sikk2016) in their agendas. We also further differentiate the monolithic category of Euroscepticism used by The PopuList to distinguish between various stances on the EU and European integration. In order to offer some sort of measure of relative importance, we report on national electoral performances in 2019 or in the year most closely prior to 2019. We report any participation in national governments that took place in 2019. We also look, for EU member states, at the electoral performance of populist parties in the 2019 European Parliament (EP) election and the group affiliation for those parties that secured members of the EP (MEPs). A further significant way in which we complement existing knowledge is by providing qualitative country descriptions of the state of populist parties in 30 European countries – that is, the 27 EU member states plus Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom (see Appendix).

The motivation behind our endeavour is that no study of active political parties can aspire to be conclusive: parties do change their stances over time and adapt to circumstances – and this surely holds for chameleonic entities like populist parties (Taggart, Reference Taggart2000). Hence, this overview is not concerned, at this stage, with outlining longitudinal trends, but is designed as a synchronous comparative exercise and a resource. We focus on 2019 because this was the most recent complete calendar year at the time of our research, and provides a ready empirical application of The PopuList, which was also released the same year. It was also the year of the latest EP election, which is a useful electoral benchmark for the performance of these parties. With hindsight, 2019 might turn out to be a high point for European populism. Amid the fundamental challenges arising from the COVID-19 pandemic, it now remains to be seen whether and how national electorates will reward populist parties for their responses to the crisis. In the following section, we briefly outline the rationale guiding our classification strategy and the different dimensions underlying it.

Differentiating among European populist parties

The primary focus of our study is on EU member states, but we have also included Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The data for this contribution focuses on a number of issues – the ideological placement of the parties, their performance in the EP election in 2019 (where relevant) and most recent national elections, their participation in government, and (where relevant) the parties' EP affiliations. Our research draws on our own reading of programmatic documents, the media coverage, and the secondary literature about populist parties.

We treat populism as an ideology or set of ideas and start with the presumption that it is possible to operate the first distinction between populist and non-populist parties (van Kessel, Reference van Kessel2015). There have been recent attempts to gauge party-based populism (Norris, Reference Norris2020; Meijers and Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021), but before considering as a matter of degree how populist parties are, we feel there is value in identifying which parties qualify as populist. The PopuList (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, de Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019) moved an important step in this direction subscribing to a crisp logic, but it is somewhat less sensitive to party change over time. Our decision to focus on one single year responds to this concern and presents a classification of parties for the year 2019. This is essentially why we feel compelled to define membership in the populist set. In our classification, we attempted to include all populist parties which have either contested the last national elections or ran in the EP in 2019 (where appropriate) returning at least 2% of the vote or one seat either at the national or supranational level, with a broad aspiration to meet Sartori's criteria of relevance (Reference Sartori1976: 121–123). By doing this, we can identify 63 European parties that meet our criteria and can be classified as populist in 2019.Footnote 3

After identifying populist parties, we locate them along the ideological left–right continuum. We cover the whole spectrum from radical left to the radical right, including moderate right, centre, and moderate left positions in between. The meaning of this distinction is based on an overarching notion of equality (Bobbio, Reference Bobbio1997), whereby the radical left can be interpreted as the most inclusionary and egalitarian and the radical right as the least egalitarian and most exclusionary. The extreme poles of this continuum broadly correspond to the endorsement of democratic socialism (radical left, as per March, Reference March2011) and nativism and authoritarianism (radical right, as per Mudde Reference Mudde2007). Further differentiations in between are articulated in more detail in the qualitative part of this study (Appendix) and rest on whether parties embody social-democratic values (moderate left), social conservatism and/or economic liberalism (moderate right), or centrist reformism (centre).

The other ideological aspect we consider is the party stance on European integration. Although The PopuList does identify whether the parties are broadly Eurosceptic, much of the literature on party-based Euroscepticism argues for differentiating between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ Euroscepticism where the ‘hard’ classification means advocating non-membership of the EU. There is, as yet, no comprehensive classification of what type of Euroscepticism populist parties hold (if any), so we have offered this classification in the data. We essentially determine whether the party falls into the Eurosceptic category, and then distinguish between ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ Eurosceptic positions (Szczerbiak and Taggart, Reference Szczerbiak and Taggart2008) based on the stances elaborated in their most recent manifestos or their official websites and the secondary literature.

In order to facilitate comparisons between the relative importance of the parties in their national party systems, we report both on the performance in 2019 national elections (or most recent election prior to 2019) and in the 2019 EP election. We then look into any government participation in 2019. These two aspects resonate with the steady electoral growth of right-wing populist parties across Europe (Halikiopoulou, Reference Halikiopoulou2018; Bernhard and Kriesi, Reference Bernhard and Kriesi2019) and the overall influence exerted while sitting in government (Pirro, Reference Pirro2015; Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016; Wolinetz and Zaslove, Reference Wolinetz and Zaslove2018). Finally, we report on the political group affiliation within the EP to monitor the latest developments at the level of supranational party group membership, which is part of a broader concern with shifting alliances and influence at the EU level (McDonnell and Werner, Reference McDonnell and Werner2019). Looking across the data generated we can make some broad-based comparison across the range of cases.

A comparative overview of contemporary European populist parties

Table 1 summarizes the data presented so far. An extensive qualitative overview of the 30 national cases is supplied in the Appendix. The overall picture we get is one of variance. The table lists the parties and provides a measure of their electoral relevance with their result in the most recent national elections (either in or before 2019), their national vote share in the 2019 EP election (for EU member states) as well as their party group affiliation in the EP (where relevant). We also provide a characterization of their position on European integration under the ‘Euroscepticism’ column where we classify them as either hard or soft Eurosceptic (Szczerbiak and Taggart, Reference Szczerbiak and Taggart2008), or as not Eurosceptic or as holding an ambiguous position.

Table 1. Description and performance of populist parties in Europe

Notes

• Bulgaria: The parties marked with an asterisk ran as part of the United Patriots (OP) coalition in 2017, hence the same electoral results. In 2019, Ataka was ousted from OP.

• Cyprus: The Citizens' Alliance ran in the 2019 EP elections with the Movement of Ecologists.

• Denmark: The Danish People's Party provided external support to the minority Liberal-Conservative coalition government until June 2019.

• Finland: Blue Reform, a breakaway from the Finns Party, maintained ministerial positions that had gained in the 2015 election as part of the Finns Party.

• France: National election results refer to the first round of the 2017 presidential election.

• Italy: The League remained in government with the M5S until August 2019.

• Poland: Kukiz’15 contested the 2019 general elections as part of the Polish Coalition (KP).

• Portugal: Chega!'s EP election results refer to the Basta! coalition.

• Slovenia: The Slovenian Democratic Party ran with the Slovenian People's Party (SLS) in the 2019 EP elections.

• Spain: Elections were held twice in 2019. Podemos ran as part of the Unidas Podemos (UP) coalition at the national level and joined the government coalition coming out of the November elections.

European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR); Identity and Democracy (ID); not applicable (n/a); European People's Party (EPP); Non-Inscrits (NI); Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD); European United Left/Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL); Socialists and Democrats (S&D).

Looking at the table overall, we can make some comparative observations about the state of populist parties in Europe before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. The first observation we can make is that populist parties are by no means a unified phenomenon and there is diversity among those parties that fit into the category. This means that we need to be careful about not overgeneralizing populism in contemporary Europe or conflating populism and right-wing politics (Art, Reference Art2020). Such variance can be seen in a number of different ways. In terms of ideological diversity, while there is an electoral preponderance of the radical right (with 40 of 63 parties), there are parties distributed across the whole left–right spectrum, including radical left parties, centre parties, and parties of the moderate left and right (Table 1). The last decade has seen the emergence and consolidation of a number of populist left parties (Katsambekis and Kioupkiolis, Reference Katsambekis and Kioupkiolis2019). Some of them rose to prominence in response to the austerity measures implemented after the breakout of the Eurozone crisis (della Porta et al., Reference della Porta, Fernández, Kouki and Mosca2017) and cast doubt on the interpretation of European populism as the chief preserve of ‘exclusionary’ actors (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2013). Notable populist left parties like the Greek SYRIZA or the Spanish Podemos have become significant players in their party systems.

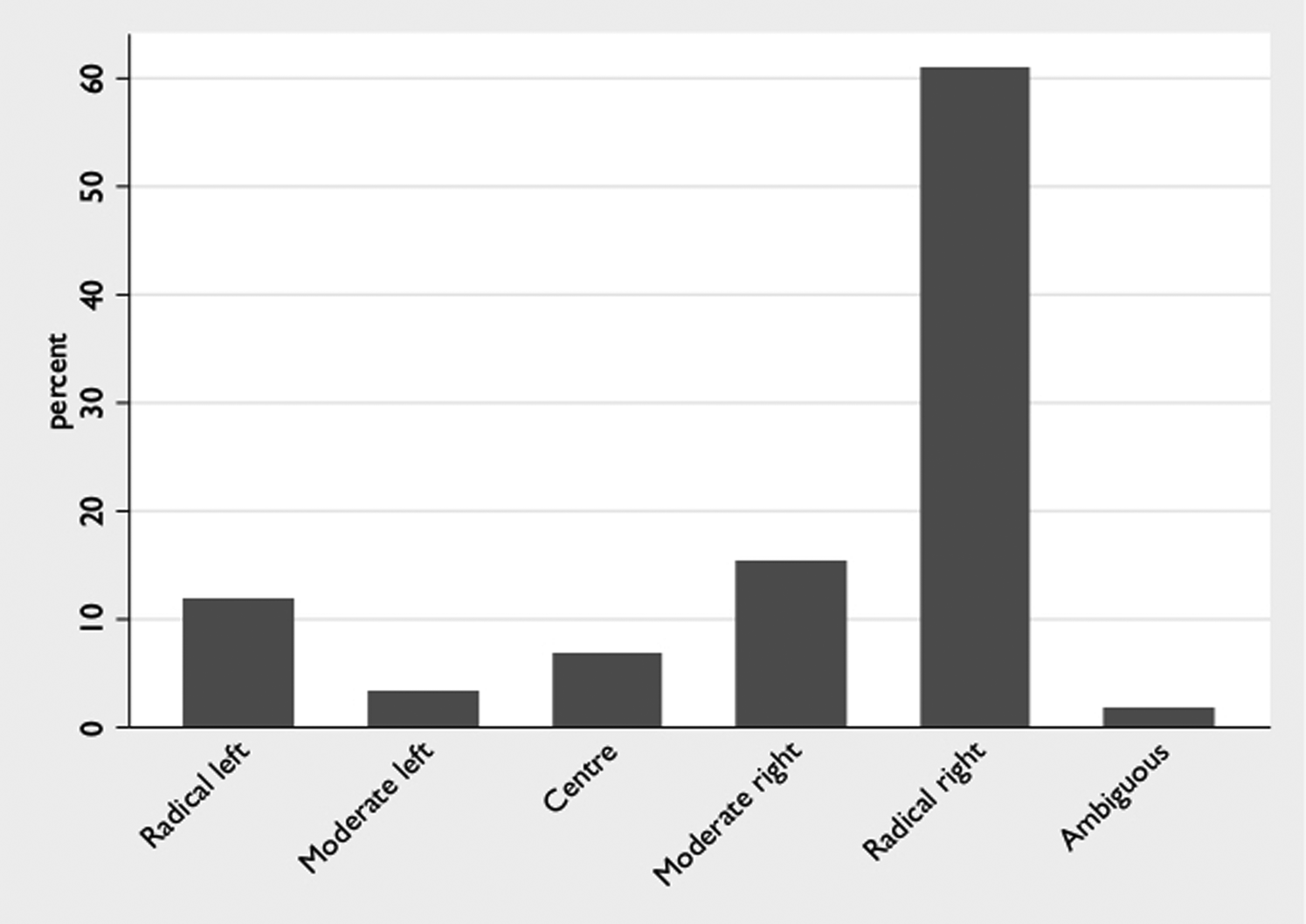

The populist right (i.e. radical and moderate) is, on average, electorally dominant among European populist parties. Three-quarter of electoral gains by populists went to parties of the radical and moderate right (Figure 1), further qualifying the electoral gains of the right across the past two decades (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Clarke, Barr, Holder and Kommenda2018). With the exception of SYRIZA, the Slovak Direction-Social Democracy (Smer-SD), and to a lesser extent Podemos – which were incidentally also governing forces in 2019 – the populist left has not made anything like the same electoral inroads of the populist right into national party systems.

Figure 1. Relative electoral strength (within the populist set) in 2019 national elections (or most recent elections prior to 2019), per ideological position.

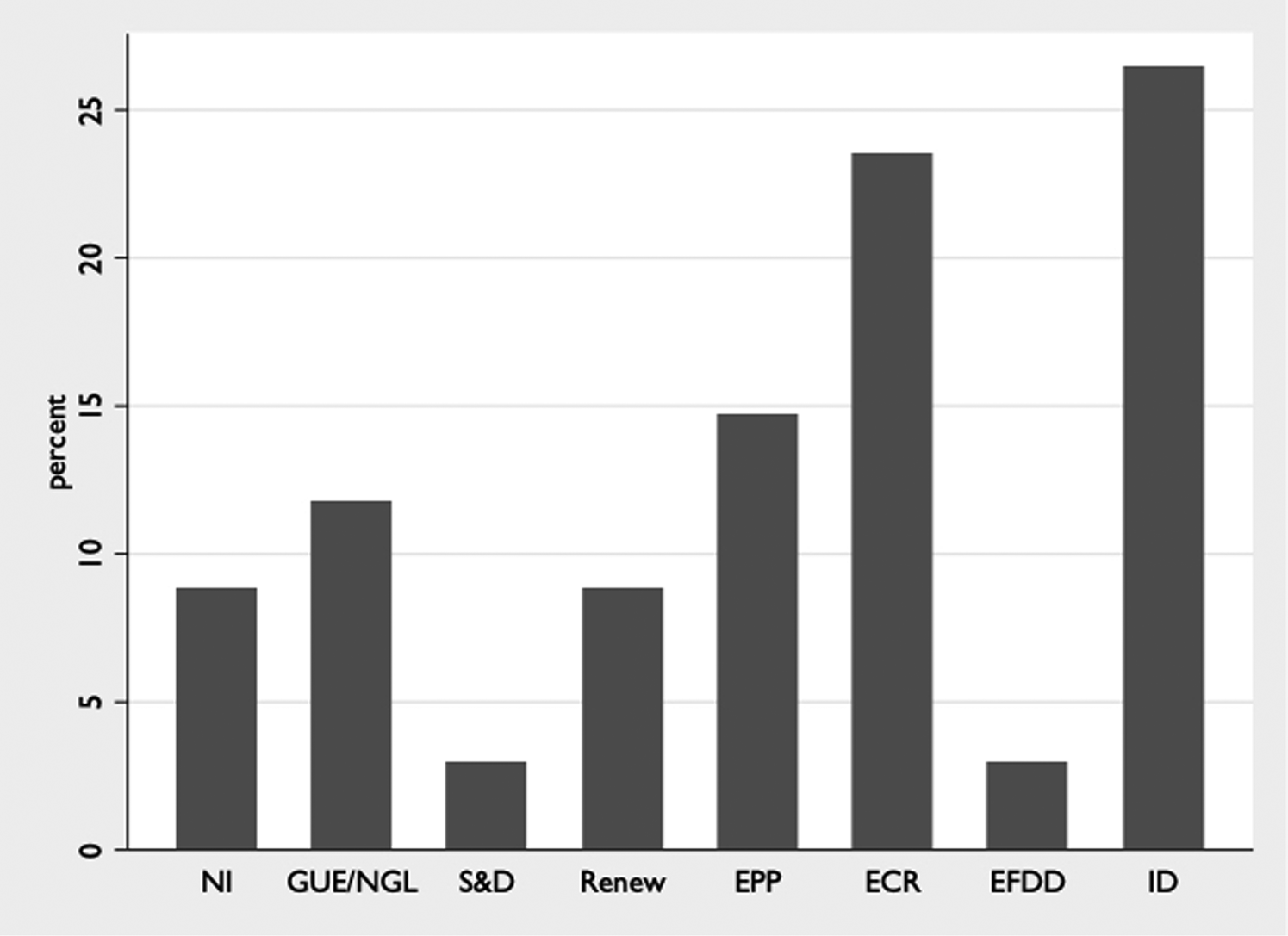

The overall diversity of European populism is probably best exemplified by Figure 2 which shows, where countries are EU members, the relative electoral weight of populist parties in the 2019 EP election, arranged by party group affiliation. Even here we can see a high degree of variation. This diversity should not surprise us as populism is a thin-centred ideology that attaches to other ideologies. But it is important that, despite the slight electoral prevalence and broad ideological homogeneity of the nativist Identity and Democracy (ID) group, we do not mistake populism in contemporary Europe with being an exclusively radical right phenomenon, or attribute a necessary correspondence between the ideological orientation of the party and group affiliation in the EP. As a case in point, the gains of the populist radical right are almost evenly split between the ID group and the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR). Within the radical right subset, we then find the Hungarian Fidesz-KDNP and Slovenian Democratic Party sitting together with other moderate right and pro-EU forces as part of the European People's Party (EPP). Fidesz's group membership was, however, suspended in March 2019, showing the EPP's half-hearted efforts to deal with an enfant terrible in its midst. Finally, and with the sole exception of the Slovak Smer-SD (Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats, S&D), all major populist parties of the left are members of the European United Left/Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL) group. This overview suggests that international/supranational affiliations might still serve poorly as ideological proxies (Mair and Mudde, Reference Mair and Mudde1998).

Figure 2. Relative electoral strength (within the populist set) in 2019 European Parliament election, per party group.

Note: Non-Inscrits (NI); European United Left/Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL); Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D); Renew Europe (Renew); European People's Party (EPP); European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR); Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD); Identity and Democracy (ID).

The 2019 EP election was widely anticipated as a test for further electoral growth and coalition-building among populist radical right parties (Erlanger, Reference Erlanger2019). Although the populist radical right did indeed gain some ground (but not as much as predicted), it did not end up coalescing under a single EP group banner. Nonetheless, populists’ actions and alliances at the supranational level are becoming even more visible (McDonnell and Werner, Reference McDonnell and Werner2019) and we can see a higher degree of convergence and cooperation, at least within the ID group. Besides pragmatic considerations on the access to resources granted by group membership, it may be that the traditional concerns defining far-right politics in Eastern and Western Europe (Pirro, Reference Pirro2015) have been equalized by the politicization of immigration across the whole continent after the European ‘migrant crisis’ of 2015. If anything, the populist radical right may be rallying around the ID flag on the basis of a common ideological denominator now comprising not only Euroscepticism but also opposition to immigration.

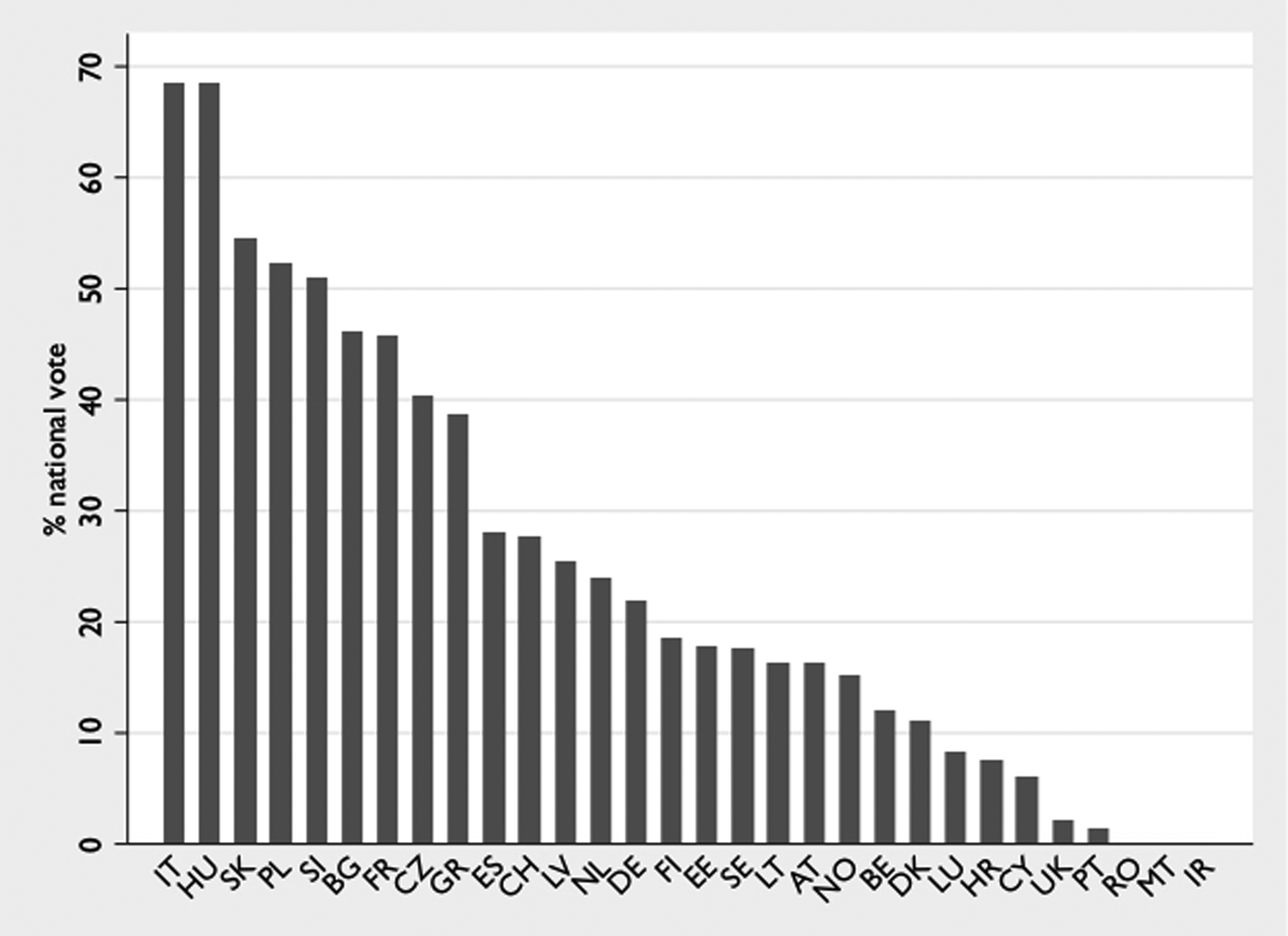

Looking at the geographical distribution of party-based populism and its cumulative performance in the last national elections (Figure 3), there appears to be some regional diversity: populist parties do very well in Central and East European countries. There is a clear set of cases that stand out as having comparatively high support for populist parties that amounts to over 30% of the vote. Of these nine countries, all but three (Italy, Greece, and France) are in Central and Eastern Europe. Populist parties single-handedly or cumulatively scored over 40% of the vote in national elections in Bulgaria, Czechia, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia; in Hungary, two right-wing populist parties (Fidesz-KDNP and Jobbik) captured two-thirds of the national vote share in 2018. The converse is, however, not true; those countries with comparatively low levels of support for populist parties are not mainly from any part of Europe as the eight countries with under 10% support are from Southern, Central and Eastern, and Western Europe.

Figure 3. Cumulative populist party vote share in 2019 national elections (or most recent elections prior to 2019), by country.

Note: Italy (IT); Hungary (HU); Slovakia (SK); Poland (PL); Slovenia (SI); Bulgaria (BG); France (FR); Czechia (CZ); Greece (GR); Spain (ES); Switzerland (CH); Latvia (LV); The Netherlands (NL); Germany (DE); Finland (FI); Estonia (EE); Sweden (SE); Lithuania (LT); Austria (AT); Norway (NO); Belgium (BE); Denmark (DK); Luxembourg (LU); Croatia (HR); Cyprus (CY); United Kingdom (UK); Portugal (PT); Romania (RO); Malta (MT); Ireland (IE)

Considering the debate as to whether populist parties are moving into the ‘mainstream’, we can see how many of the parties had some sort of government role in 2019. It is remarkable that 23 of 63 populist parties were in government in 2019. Of course, there are some real differences between the governmental experiences of these parties. There are parties like Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland and Fidesz-KDNP in Hungary that are essentially majority parties of government, and there are populist coalitions such as the League and the 5 Star Movement in Italy (Conte I Cabinet: June 2018–September 2019), but most of the remaining cases are coalition partners with a variation of importance within the governing coalition. What is really significant is that over one-third of European populist parties were in government at some point in 2019.

Looking at these parties' role in public office, Cas Mudde (Reference Mudde2013: 4) concluded that: ‘All in all, populist radical right government participation remains a rarity in Western Europe’. Although this is a subset of our sample, it seems fair to note from our data that the situation has changed in recent years. The fact that a significant proportion of contemporary populists have had an experience of government is confirmation of the trend that European populist parties have moved from being insurgent parties to being potential and existing parties of government (Albertazzi and Mueller, Reference Albertazzi and Mueller2013; Albertazzi and McDonnell, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015; Pirro, Reference Pirro2015; Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016; Wolinetz and Zalsove, Reference Wolinetz and Zaslove2018). Although populist parties are still in many cases insurgent anti-establishment parties, a significant number of them have eventually moved into being a part of the establishment.

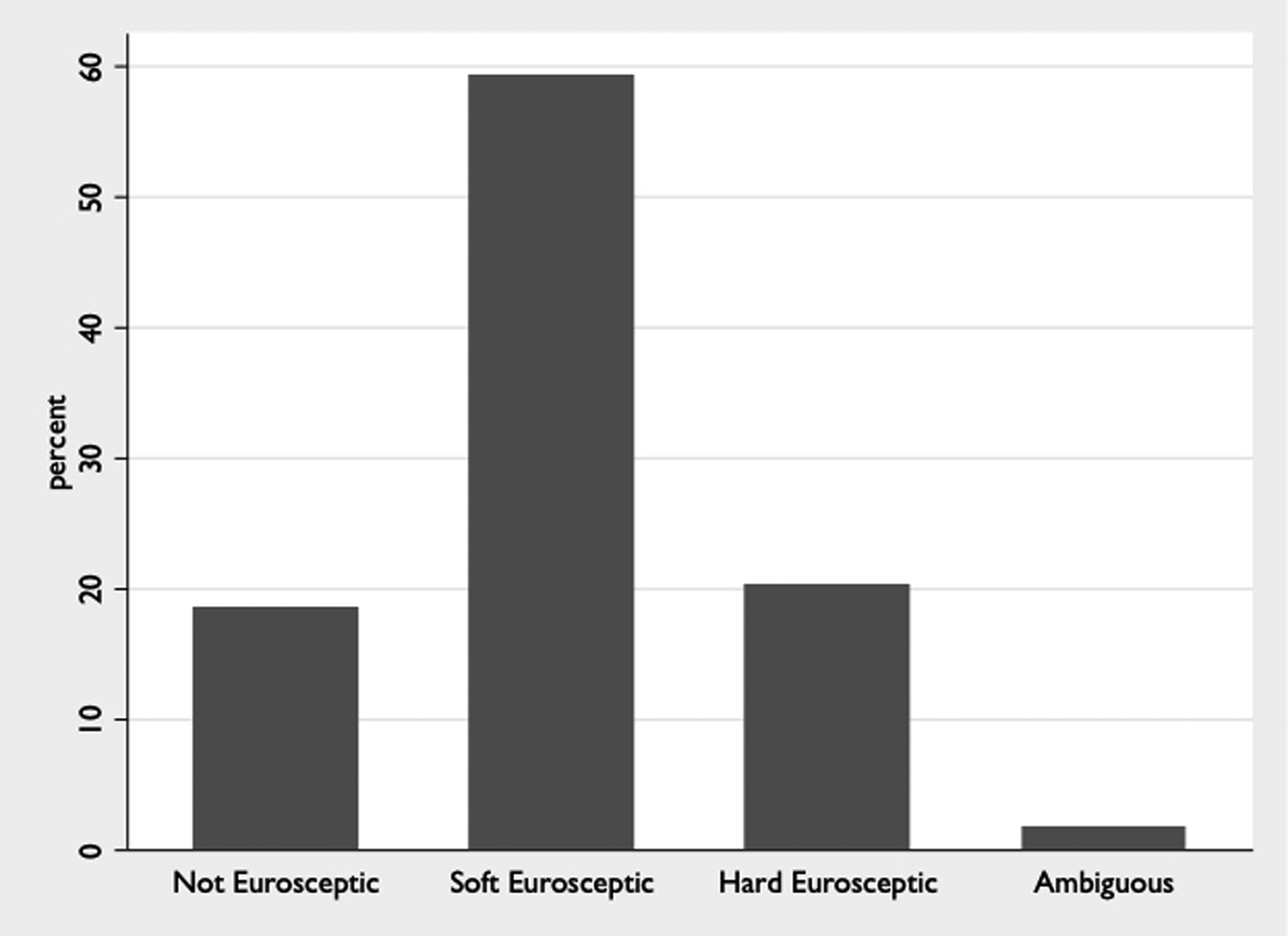

The final overall comment we can make about populist parties in 2019 concerns the position of these parties on European integration. In terms of party-based attitudes on the EU, there is no one-to-one correspondence between populism and Euroscepticism (Pirro and Taggart, Reference Pirro and Taggart2018; Rooduijn and van Kessel, Reference Rooduijn, van Kessel and Thompson2019), and our extensive survey goes a long way corroborating it. We can observe that, just as populism is a diverse category, so there are important differences between types of Euroscepticism. The distinction between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ Euroscepticism, which we have applied here, differentiates between those parties whose hostility to European integration is such that they want their states to leave (or not join) the EU and those soft Eurosceptics that are hostile to European integration/EU but stop short of eschewing membership (Szczerbiak and Taggart, Reference Szczerbiak and Taggart2008). Soft Euroscepticism is far more prevalent than hard Euroscepticism among our populist parties, with 38 soft-Eurosceptic and 14 hard-Eurosceptic parties – almost half of which hailing from countries that are not, or are no longer, EU member states (Table 1). This fits with other findings concerning the 2019 EP elections which show that, of all parties expressing Euroscepticism, hard Euroscepticism is very rare (Taggart, Reference Taggart, Bolin, Falasca, Grusell and Nord2019).

Not all of the populist parties are Eurosceptic. Eleven populist parties endorse EU membership and the process of European integration, and all but one of these (Silvio Berlusconi's Forza Italia) are from Central and Eastern Europe. Pro-EU populist parties managed to attract, on average, roughly one-fourth of the populist vote in recent national elections, meaning that a positive stance on the EU is far from incompatible with populism and not at all marginal, electorally speaking. Figure 4 shows this in terms of relative electoral strength for populist parties in the latest national elections.

Figure 4. Relative electoral strength (within the populist set) in 2019 national elections (or most recent elections prior to 2019), per stance on European Union (EU).

Only one party, the Progress Party in Norway, has taken an outright ambiguous position on European integration. While populist parties' stances on ‘Europe’ have wavered in the face of the multiple crises (Pirro and van Kessel, Reference Pirro and van Kessel2017; Reference Pirro and van Kessel2018) elusive positions are becoming more and more common – and clearly so among the populist radical right. Looking at the Freedom Party (Austria) and League (Italy), Heinisch et al. (Reference Heinisch, McDonnell and Werner2020) have argued that these parties best fit a third category of ‘equivocal Euroscepticism’, which collapses the binary nature of hard and soft Euroscepticism. In a similar way, Hloušek and Kaniok (Reference Hloušek, Kaniok, Hloušek and Kraniok2020) argue that soft Euroscepticism in Central and Eastern Europe in the 2019 EP elections blended into support for the EU. All in all, it is clear that there is a preponderance of soft Euroscepticism among European populist parties in 2019, but there is also a range of other positions on the issue of European integration and that we should be careful not to simply equate European populism with Euroscepticism.

Concluding remarks

Europe has generally witnessed a growing tide of support for populist parties in recent years. By building on recent classifications and by freezing the timeframe of analysis, we were able to provide a clear snapshot of the nature, strength, and impact of populist parties in 30 European countries. There have always been significant variations in the fortunes of populist parties across the continent, but now they are almost ubiquitous and increasingly important to many of their respective party systems and institutions of supranational governance. There is therefore a temptation to generalize across the cases. We have shown however that populist parties are relatively diverse in terms of ideology, electoral performance, supranational affiliation, and attitudes to European integration.

Taken together, populist parties are a telling indicator of wider changes in contemporary European politics. But taking them apart, the picture is one with a degree of diversity and means that we need to be careful about overgeneralizing European populism. The economic, financial, and migration crises as well as Brexit have played a clear role, albeit in different ways, in providing issues, sources of mobilization, and ready constituencies for these parties in the period before 2019. Looking forward to the reaction of populist parties to the COVID-19 pandemic, along with the changing form of European politics, means we should expect diverse responses, and not be seeking to predict a single outcome for populist parties in Europe.

Funding

The research received no grants from the public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Neil Dooley, Igor Guardiancich, Daphne Halikiopoulou, Marco Lisi, Martín Portos, Dragomir Stoyanov, Aleks Szczerbiak, and Giorgos Venizelos for their generous insights on specific country cases. We also wish to extend our gratitude to the two anonymous reviewers and the editors of the journal for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this work.

Appendix

Populist parties in 30 European countries

Austria

Austria has long had a populist radical right party in the Freedom Party (FPÖ), which has already been in government as part of a coalition between 2000 and 2005. In 2019, the party was once again in coalition with the People's Party (ÖVP) – an agreement that was reached after the 2017 election. The Freedom Party was led by Heinz-Christian Strache and has established itself as a party focused on defending Austrian identity, and with an anti-immigration and soft-Eurosceptic position. In the 2019 EP election, the party managed 17.2% of the vote and joined the ID group. In May 2019, a scandal involving Strache being secretly filmed soliciting funds in return for committing to censor the media led to the collapse of the coalition government. Strache left the party leadership shortly after. As a result of the government collapse, new elections were held in September 2019 with the Freedom Party gaining 16.2% of the vote. The People's Party this time formed an unprecedented coalition with the Greens. In October Strache resigned from the Freedom Party; the current leader was a former presidential candidate and Strache advisor, Norbert Hofer.

Belgium

Flemish Interest (VB) is a populist radical right party looking to represent Flemish nationalism, seeking secession from Belgium. Flemish Interest opposes multiculturalism and is soft Eurosceptic. The party achieved 12% in the 2019 national election (with 18.5% in Flanders) and 12.1% in the 2019 EP election. The party is a member of the ID group in the EP. The year 2019 was good for the party as its electoral success challenged the cordon sanitaire that the major parties have traditionally held against any cooperation with it. This meant that, after the election, leader Tom van Grieken was invited to meet the King, which was unprecedented. Government formation talks continued throughout 2019 and when they were completed (in 2020) Flemish Interest was not included.

Bulgaria

Populism is a central feature of Bulgarian politics. In 2019, there were five relevant populist parties in the country. The first and most important is the moderate right Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB), which has led coalition governments since 2014. The party headed by Prime Minister Boyko Borisov is a conservative and pro-EU force that gained 31.1% of the vote in the 2019 EP election. The party is a member of the EPP. In the aftermath of the 2017 general election, GERB formed a coalition with the United Patriots (OP), an electoral alliance comprising a number of radical right and Eurosceptic parties: Ataka (Attack), the National Front for the Salvation of Bulgaria (NFSB), and the Bulgarian National Movement (VMRO).Footnote 4 Ataka was ousted from United Patriots in July 2019 and is no longer part of the government coalition. Ataka combines a radical right anti-establishment agenda with hard Euroscepticism and a pro-Russia stance (Pirro, Reference Pirro2015). It is led by Volen Siderov and it campaigns on the slogan ‘To get Bulgaria back’ arguing that the Bulgarian establishment is in cahoots with the EU and the United States. In the last EP election, Ataka only attained 1.1% of the vote. The radical right NFSB was established by Valery Simeonov as a breakaway from Ataka in 2011. It is an anti-establishment, anti-immigrant, and anti-minority party, and has a soft-Eurosceptic stance. It endorses government spending and is protectionist in terms of Bulgarian business. It attained 1.2% of the vote in the 2019 EP election. VMRO, the longest living radical right party in post-communist Bulgaria, is an anti-establishment party that was originally founded to represent the Bulgarian diaspora. The party, led by two-time presidential candidate Krasimir Karakachanov, takes an anti-minority and anti-immigrant position, and argues for the protection of Bulgarian culture and society with its slogan ‘We defend Bulgaria’. The party gained 7.4% of the vote in the 2019 EP election and is a member of the ECR group. Finally, Volya (Will) is a radical right anti-establishment party led by Veselin Mareshki, who suggests that he could run the country like a business and is critical of established politicians for their incompetence and corruption. The party has a soft-Eurosceptic position and initially offered external support to the GERB-led government in 2017. It gained 3.6% in the 2019 EP election.

Croatia

Populism has played a secondary role in Croatia's party duopoly between the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) and the Social Democratic Party. Much of these parties' dominance was, however, challenged by the rise of the Bridge of Independent Lists (Most). The moderate right party, founded and led by Božo Petrov, was a kingmaker both in the 2015 general election and the snap election called in 2016. The party is concerned with good governance and liberal reforms, and while it bears an anti-establishment profile, it does not qualify as a fully fledged case of populism (Grbeša and Šalaj, Reference Grbeša and Šalaj2017).Footnote 5 Croatia has two populist parties represented in parliament: the left-libertarian Human Shield (ZZ) and the right-wing Croatian Democratic Alliance of Slavonia and Baranja (HDSSB). Human Shield centres on its leader Ivan Vilibor Sinčić, who ranked third in the 2016 presidential election. The party has an anti-eviction, anti-globalist, pacifist, and environmentalist platform, and advocates referendums on withdrawal from the EU and NATO. In the run-up to the 2019 European election, ZZ started inconclusive talks with the Italian 5 Star Movement to form a joint group in the EP. The party scored 5.7% and returned one MEP, Sinčić himself. The Croatian Democratic Alliance of Slavonia and Baranja is now a marginal party that failed to gain representation in the 2019 EP election. It is a case of regionalist populism, founded and led by convicted war criminal Branimir Glavaš (Kukec, Reference Kukec, Heinisch, Massetti and Mazzoleni2020). The party emerged in 2006 following Glavaš's ousting from the HDZ and defines itself as liberal and pro-EU. It opposes the corruption and political mismanagements of the central government, and promotes the economic advancement of Slavonia and Baranja within a united and federal Croatia.

Cyprus

Citizens' Alliance (SP) qualifies as Cyprus's only populist party. Citizens' Alliance presents itself as ‘post-ideological’ and puts at the heart of its vision Cyprus and its citizens. The party is primarily concerned with the peaceful resolution of the Cypriot question, aiming at the withdrawal of the Turkish army from the island as the only prospect for the security and prosperity of all ethnicities in a common homeland. Its founder, Giorgos Lillikas, has been involved in Cypriot politics for several years within the ranks of the radical left Progressive Party of Working People (AKEL); he served as Minister of Commerce, Industry, and Tourism as well as Minister of Foreign Affairs; and then ran as an independent presidential candidate in 2013. Citizens' Alliance scored 3.3% of the vote at the 2019 EP election as part of a joint alliance with the Movement of Ecologists.

Czechia

Accusations of ‘democratic backsliding’ in Central-Eastern Europe are also increasingly centring on the path undertaken by Czechia (Hanley and Vachudova, Reference Hanley and Vachudova2018; Vachudova, Reference Vachudova2020). The main party seen as responsible for this in the country is the Action of Dissatisfied Citizens (ANO) of Andrej Babiš, who has led a minority government since 2017, and in coalition with the moderate-left Czech Social Democratic Party since 2018. ANO is an anti-establishment pro-business party that gained 21.2% of the vote in the 2019 EP election. Babiš, a billionaire and former businessman, has run the country ‘as a firm’, hence preferring decisionism over deliberation: ‘Babiš has effectively reduced politics to a technocratic exercise on behalf of the people’ (Buštíková and Guasti, Reference Buštíková and Guasti2019: 318). ANO's leader recently faced investigations of fraud and misuse of millions in EU funds. Throughout 2019, people took the streets in huge numbers urging Babiš to resign. These have been the largest demonstrations held in the country since 1989. Babiš's party is member of the liberal group Renew Europe in the EP. Czechia also has a populist radical right party with Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD), which scored 9.1% in the EP election. Freedom and Direct Democracy is led by Czech–Japanese entrepreneur Tomio Okamura and is a vocal anti-immigrant party, especially concerning immigration from Muslim countries (Wondreys, Reference Wondreys2020). The party advocates greater use of direct democracy, among other things on continued EU membership – a reason for which SPD qualifies as hard Eurosceptic. Freedom and Direct Democracy is part of the ID group in the EP.

Denmark

The Danish People's Party (DF) is a long-standing populist radical right party. It is an integral part of the Danish party system having formed in 1995 as a breakaway from the Progress Party, which originally developed as an anti-tax party. Its agenda has combined opposition to immigration, including latterly an anti-Islam position, with soft Euroscepticism, but it does not endorse the free market as it in principle opposes tax cuts. The party started in 2019 with a strong position, providing external support to the minority Liberal-Conservative coalition government. As a result, it had, in the words of Kosiara-Pedersen (Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2020: 1012), ‘left more than light footprints on government policies’ with respect to immigration, integration, and economic policies. The EP election in May 2019 was followed quickly by the national election. The Danish People's Party gained 10.8% in the first and only 8.7% in the latter held in June. These results came down to a massive drop from the 21% the party achieved in 2015. This was despite the prominence of immigration as an issue in the elections. The Danish People's Party is a member of the ID group in the EP. A new virulently ethnic nationalist party, called Hard Line (SK), clearly ate into its vote in the national election as did the move of the Social Democratic Party to a harder line immigration stance. Hard Line is essentially based around its leader Rasmus Paludan and is an anti-Islamic ultranationalist party and only borderline populist. The New Right (NB) is a relatively new populist party, formed in 2015 and led by Pernille Vermund, a disillusioned Conservative Party member. The party also pulled votes from the Danish People's Party, though from a more liberal economic position, a harder line on immigration, and a hard-Eurosceptic stance. It did not contest the EP election but gained 2.4% in the national election.

Estonia

The Conservative People's Party (EKRE) has enjoyed growing popularity since 2015. The year 2019 was particularly rewarding at the electoral level: EKRE first scored 17.8% of the vote in the March general election and then 12.7% in the EP election in May. The party was invited to join the government led by Jüri Ratas (Centre Party) alongside the rightist Isamaa (Fatherland), gaining control of seven ministerial posts. EKRE party leader Mart Helme was Minister of the Interior and his son, Martin Helme, Minister of Finance. EKRE stems from the merger of the agrarian People's Union of Estonia and the pressure group Estonian Patriotic Movement, and qualifies as a socially conservative ethnonationalist populist party, with a pronounced anti-cosmopolitan, anti-immigrant, and anti-Russian profile, and a soft-Eurosceptic agenda (Braghiroli and Petsinis, Reference Braghiroli and Petsinis2019). In the EP, the party is affiliated to the ID group and transnationally with two other far-right parties, the Latvian National Alliance (NA) and the electorally marginal Lithuanian Nationalist Union.

France

France has had one of the longest and most durable populist parties in the form of the National Rally (RN, formerly National Front). Marine Le Pen's leadership has shifted the position of the party under its former leader Jean-Marie Le Pen in an attempt to soften the edges of its hard-line position on immigration but remains a party that contests and mobilizes on immigration, law and order, and national identity (Shields, Reference Shields2013). The National Rally has had a sustained soft-Eurosceptic position and is one of the main drivers behind the ID group in the EP. In the 2019 EP election, the party received the highest share of the vote with 23.3% and this built on Le Pen's success at securing the second round of the 2017 presidential election, where she was beaten by Emmanuel Macron. The party has effectively become the main party of opposition to Macron's En Marche. On the left, the party of Jean-Luc Mélenchon, La France Insoumise (‘Unbowed France’, LFI) continues Mélenchon's radical left positioning, but combines this with a disdain for the governing ‘caste’ of French politics and calling for a sixth republic with popular sovereignty as the guiding principle. He is critical of the EU's economic liberalism and the challenge it poses to French sovereignty but does not call for withdrawal and is, therefore, soft Eurosceptic. The year 2019 has seen the party riven with internal conflict and with a clear loss of direction. LFI gained 6.3% in the 2019 EP election and sits with the European United Left in the EP. A final populist party drawing on the Gaullist tradition is the moderate right Debout La France (‘France Arise’, DLF), which is effectively the vehicle for Nicolas Dupont-Aignan. DLF emphasises direct democracy and the need for political reform and takes a soft-Eurosceptic position. The party has only one national representative and scored 3.5% of the vote in the 2019 EP election. With the rise of the gilets jaunes, France appears to be a country awash with populist parties and movements, but most of these remain minor players compared to the National Rally.

Finland

Finnish populism is epitomised by the Finns Party (PS) – previously True Finns and successor to the Rural Party. In recent years, the party had both experienced government participation with its former leader Timo Soini becoming the Foreign Minister, and a split in 2017 when 20 MPs left to form what became Blue Reform (SIN). The Finns have long maintained an anti-establishment stance and have been characterized as a populist radical right party, but with more muted xenophobia than other parties in that family (Arter, Reference Arter2010). The Finns' long-standing leader Timo Soini was replaced in 2017 by Jussi Halla-aho who took a harder line on immigration. The Finns left the government coalition that they had taken part in since the 2015 parliamentary election, while Blue Reform remained an important governmental player until 2019. In the 2019 general election held in April, the Finns campaigned on opposition to the mainstream, and particularly on issues of immigration and climate change. As result, the Finns returned to their pre-split levels of support with 17.5%, while Blue Reform collapsed with less than 1% of the vote (Arter, Reference Arter2020). In the 2019 EP election, the position seemed to be consolidated with the Finns gaining 13.8% and Blue Reform 0.3%. The Finns sit in the EP with the ID group.

Germany

Germany has two parties that can be considered populist. On the right, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) has emerged as a radical right party. The party began in 2013 as an anti-Euro party but was soon transformed into an anti-establishment and anti-immigrant soft-Eurosceptic party (Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer2015; Olsen, Reference Olsen2018). AfD scored 11% of the vote in the 2019 EP election and is a member of the ID group. On the other side of the political spectrum, Die Linke (The Left) grew out of the communist successor party and has established itself as a party with a populist ideology (Hough and Koss, Reference Hough and Koss2009). It is suspicious of globalization and critical of the existing form of democracy arguing for more direct democracy (Olsen, Reference Olsen2018). The party gained 5.5% in the 2019 EP election. The party is a member of the European United Left group. 2019 saw the party gain power in the eastern state of Thuringia where, for the first time, it won the highest share of the vote in any German state. The subsequent election of the minister-president saw Thomas Kemmerich (Free Democratic Party) designated with the support of the Christian Democrats and the AfD. The support of the AfD caused a national political storm and the ire of Chancellor Angela Merkel; as a result, Die Linke formed a minority government.

Greece

The Coalition of the Radical Left (SYRIZA) is one of the key populist parties of the past decade, and certainly the most prominent and successful among those of the left. SYRIZA rose from the ashes of crisis-riven Greece in the early 2010s after years of electoral marginality and ran a government coalition with the Independent Greeks (ANEL) through two consecutive mandates between 2015 and 2019. The party led by Alexis Tsipras is a textbook example of democratic socialism combined with populism, whereby ‘the people’ replaced ‘the working class’ in its discourse (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004). SYRIZA stands for labour rights and the welfare state, social justice, democracy, diversity, and environmental protection. While starting from radical left and fairly Eurosceptic positions, the party moderated under the mounting pressure of government responsibility and the burden of the memorandums of understanding with the Troika (Vasilopoulou, Reference Vasilopoulou2018). SYRIZA can now be defined as a left-wing populist party with soft-Eurosceptic traits: it supports EU membership but strives to revert its excessive economic liberal and technocratic character. SYRIZA's compromise eventually led Greece out of the memorandums in August 2018, but cost it defeat to the right-wing New Democracy in the 2019 European and general elections, where Tsipras' party scored 23.8 and 31.5% of the vote, respectively. The party belongs to the European United Left group. SYRIZA's unusual partner in government was the radical right ANEL, a nationalist and social conservative party with anti-immigration positions. The two parties effectively converged on their criticism of the EU and a common rejection of loan agreement terms with the Troika. ANEL pulled out of the governing coalition in January 2019 upon the Greek government resolution of the Macedonia naming dispute. ANEL gained 0.8% in the 2019 EP election and did not participate in the general election held in July. The radical left European Realistic Disobedience Front (MeRA25) is also linked to the broader anti-austerity movement, and was founded in 2018 by former SYRIZA MP and Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis. MeRA25 presents itself as a progressive and responsible alternative to debt and bankruptcy. Varoufakis' party proposes, among other things, to restructure public debt, abolish austerity, reduce tax rates, and support creative entrepreneurship. While its members have criticized Greek Eurozone membership, they would rather pursue their policy goals within the Eurozone than outside of it, hence qualifying as soft Eurosceptic. MeRA25 barely missed the 3% threshold in the EP election and gained 3.4% of votes in the general election. Another new party that attained representation in 2019 is the radical right Greek Solution (EL), which scored 4.2 and 3.7% of the vote in the EP and national elections, respectively. EL was founded in 2016 and is a splinter of the populist radical right Popular Orthodox Rally (LAOS), with which it shares nationalist, anti-immigrant, and clericalist views. The party is opposed to Greek Eurozone membership and qualifies as soft Eurosceptic. The party is a member of the ECR group.

Hungary

Over the past decade, Hungarian politics has been dominated by Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and the populist powerhouse Fidesz (alongside its satellite Christian Democratic People's Party, KDNP).Footnote 6 Fidesz's landslide victories in the last three general elections translated into parliamentary supermajorities that gave Orbán ample room for manoeuvre to set Hungary on an illiberal-democratic track (Enyedi, Reference Enyedi2020). The party gained 52.6% of the vote in the 2019 EP election. After 2010, Fidesz decidedly veered towards the far-right end of the ideological spectrum in an attempt to woo voters of the Movement for a Better Hungary (Jobbik) (Pirro, Reference Pirro2015). Orbán largely succeeded in his endeavour, in no small part thanks to the politicization of ‘anti-immigration’ at the peak of the 2015 ‘migration crisis’. His nativist populist government continues to wage war against internal and external enemies (i.e. liberals and progressives, Soros, migrants, the EU), in no small part thanks to the complacency of the EPP – Fidesz's party group in the EP.Footnote 7 From main (radical right) opposition force, Jobbik embarked on a moderation trajectory in the mid-2010s (Pirro et al., Reference Pirro, Pavan, Fagan and Gazsi2021) and is presenting itself as a conservative people's party. The party so far paid a double toll for this strategy. It not only failed to (substantially) improve its electoral performance in 2018, but also lost several votes in the 2019 EP election, where it scored 6.3% of the vote. While preserving a nativist outlook, the party has lost much of its radical aura and is now teaming up with other liberal opposition parties to defeat Fidesz at the local and national levels. One of the by-products of Jobbik's moderation was the ousting of its most radical members. Our Homeland Movement (MHM) was formed in response to these developments in 2018 with the idea of upholding the original radical right ideas that brought Jobbik to prominence. Outgoing members of Jobbik, which are now part of MHM, have been represented in the Hungarian parliament after the recent split. MHM scored marginal results at the 2019 EP election (3.3%) and failed to return any MEP.

Ireland

The Republic of Ireland has long been one of the few countries without significant populist parties and notable as such (O'Malley, Reference O'Malley2008; O'Malley and Fitzgibbon, Reference O'Malley, Fitzgibbon, Kriesi and Pappas2015; Pappas and Kriesi, Reference Pappas, Kriesi, Kriesi and Pappas2015). This is particularly remarkable in recent years given the profound impact of the Euro crisis on both the Irish economy and Irish politics. The 2011 election saw the meltdown of the traditionally dominant parties of Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil, but there was no populist party filling the vacuum with independents taking up the slack (Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Farrell, Marsh, McElroy, Marsh, Farrell and McElroy2017). Sinn Féin is sometimes characterized as a populist party.Footnote 8 However as a Republican and left party in both Northern Ireland and the Republic, it has experienced important changes in recent years. The peace process since 1998 brought the party into both power-sharing in Northern Ireland and a steadily growing share of the vote in the Republic. And with the accession of Mary-Lou MacDonald as leader of the party in 2018, it has become less associated with Republicanism and more squarely associated as a left party with an agenda of housing, homelessness, and health care, while being less clearly populist.

Italy

Italy presents multiple cases of populism (Verbeek and Zaslove, Reference Verbeek and Zaslove2016) with four contemporary parties.Footnote 9 The oldest party still represented in the Italian parliament is the Lega (‘League’, formerly Northern League), a radical right party that gained 34.3% of the vote in the 2019 EP election and joined forces with the 5 Star Movement (M5S) to form a government in the aftermath of the 2018 general election. Having turned into the most popular force in Italy, Lega's leader Matteo Salvini tried to instigate a snap election in the summer of 2019. The M5S instead opted to work with the Democratic Party and other left-wing parties to remain in government. Under the leadership of Salvini, the Lega cemented its nativist and populist profile, placing emphasis on being anti-immigration and Eurosceptic, but now from the angle of a fully fledged national force (Albertazzi et al., Reference Albertazzi, Giovannini and Seddone2018; Pirro and van Kessel, Reference Pirro and van Kessel2018). The Lega is one of the driving forces of the ID group in the EP. The ideologically ambiguous M5S (Pirro, Reference Pirro2018) paid the biggest price for joining government – and doing so with a party like the Lega. This is demonstrated by the dramatic drop in support in the 2019 EP election (17.1%). Despite being the senior coalition partner, the M5S appeared often outmanoeuvred by the Lega, which displayed more political experience and a clearer agenda. The approval of M5S's trademark policy proposal – the citizens' income scheme – did not win votes in the election. The moderate right Forza Italia (FI) of former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi proved a remarkably resilient populist party over the years. The party seems, however, set on a path of electoral decline, as showed by the performance in the EP election (8.8%), in light of Lega's rise to prominence as the main party of the (populist) right bloc. FI progressively moved from economic liberalism to endorsement of a ‘social market economy’ (Albertazzi and McDonnell, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015: 27), only sporadically diverging from its pro-EU profile. Throughout 2019, Berlusconi's party maintained a confrontational stance towards the M5S. FI is a member of the EPP. The final party in the populist category is the radical right Brothers of Italy (FdI), which is slowly but steadily improving its electoral showing. The party gained 6.4% of the vote in the 2019 EP election. Leader Giorgia Meloni has thrived on her media savviness and the combination of the traditional national-conservative agenda of the Italian (far) right – de facto drawing on the legacy and personnel of the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement and its successor National Alliance – on top of the anti-immigration and Eurosceptic stance of the Lega. Meloni unsurprisingly works in close alliance with Salvini but places greater emphasis on moral issues. FdI sits with the ECR group in the EP.

Latvia

The Latvian party system has recently experienced moderate-to-significant swings in the fortunes of its populist parties. The anti-establishment, economic liberal, and soft-Eurosceptic newcomer Who Owns the State? (KPV LV) was founded in 2016 by actor and radio host Artuss Kaimiņš. The moderate right party fared particularly well in the 2018 general election, where it came second with 14.3% of the votes. Who Owns the State? then formed a government coalition with the liberal-conservative New Conservative Party and New Unity, the populist radical right National Alliance (NA) as well as the liberal Development/For!. Who Owns the State? has been since afflicted by infighting and, among several high-profile departures and expulsions (including Kaimiņš's), is now on the verge of dissolution. This should explain the party's poor performance in the EP election, where it scored a meagre 0.9%. The other populist party, NA, is on a much better footing.Footnote 10 The party has been part of government coalitions since 2011 and has gained 16.4% of the votes in the 2019 EP election. NA stems from the merger of the far-right All for Latvia! and the national-conservative For Fatherland and Freedom/LNNK and qualifies as an ethnonationalist and Eurosceptic party that opposes immigration and multiculturalism (Braghiroli and Petsinis, Reference Braghiroli and Petsinis2019). The party is a member of the ECR group in the EP and also a signatory of the Bauska Declaration, a strategic document for transnational cooperation with the Estonian Conservative People's Party and the Lithuanian Nationalists, in which they affirm their common nativist outlook.

Lithuania

Three populist parties are represented in the Lithuanian parliament. The first is the Labour Party (DP) of entrepreneur and billionaire Viktor Uspaskich, which is a centrist force concerned with economic, social, health, and cultural development. It particularly seeks to develop a strong middle class and make sure that the free market works for the common good of Lithuania. The DP aspires to bring together and elect honest, principled, and hard-working people, and create a system of MP recall to make them accountable. The DP gained 8.5% of the vote at the 2019 EP election and is member of the Renew Europe group. The second populist party is the Lithuanian Centre Party (LCP), a soft-Eurosceptic centrist force motivated by the common sense and goodwill of the Lithuanian nation, which strives to guarantee individual and societal freedoms through the emphasis on work and wealth. The LCP favours localism over globalism, and thus emphasises national interests and identity over European ones. The party gained 5.1% of the vote at the 2019 EP election but did not gain any seats. The third populist party is Order and Justice (TT), which is a nationalist and social conservative radical right force. TT places at the heart of its programmatic vision a Lithuanian revival, to be attained economically through the promotion of industry, innovation, and agriculture; and culturally, through education and family policies. The party stands for national sovereignty and values, which leads it to oppose immigration and migrant quotas and to reject the idea of a federal EU. TT's fate has been tightly linked to former chairman and Lithuanian president Rolandas Paksas, despite his impeachment in 2004 and eventual resignation from party leadership in 2016. TT experienced a steady decline since the late 2000s and failed to gain any MEPs in the 2019 EP election (2.7% of the vote).

Luxembourg

The Alternative Democracy Reform (ADR) Party is the only populist party in Luxembourg. It began as a party campaigning on pension equality between private and public sectors and has evolved into a right-wing soft-Eurosceptic party. It uses anti-establishment positions related to migration and the economy and proposes more use of direct democracy. In the EP election in 2019, the party gained 10% and in the national election held in the previous year, it gained 8.3%.

Malta

Malta has no substantial populist parties. The only party with populist credential is the radical right Maltese Patriots Movement (MPM) which is opposed to Islam, multiculturalism, and immigration, but it is electorally irrelevant as it gained 0.3% of the vote on the 2019 EP election.

The Netherlands

The Dutch party system has witnessed a number of influential populist radical right parties since the breakthrough of the List Pim Fortuyn in 2002. In this sense, the 2019 EP election was characterized by the poor performance of Geert Wilder's Party for Freedom (PVV) and the rise of Thierry Baudet's Forum for Democracy (FvD). In this election, the two parties scored 3.5 and 11% of the vote, respectively. Wilder's hard line on Islam and endorsement of a Dutch withdrawal from the EU are well-documented (van Kessel, Reference van Kessel2015; Pirro and van Kessel, Reference Pirro and van Kessel2018; van Kessel et al., Reference van Kessel, Chelotti, Drake, Roch and Rodi2020). Although starting from relatively similar ideological premises, the Forum for Democracy denounces a more general influx of immigrants and the reluctance of the ‘party cartel’ to address the issue; the Party for Freedom, on the other hand, was singularly focused on Islam. At the same time, both parties moved away from hard-Eurosceptic positions, but the Forum for Democracy seemed recently willing to reconsider the ‘Nexit’ option until ‘Brexit’ is complete and its consequences are properly assessed. As far as European issues are concerned, the Forum for Democracy prioritises withdrawal from the Eurozone and the restoration of internal border checks. The party sits with the ECR group in the EP. Ultimately, the Forum for Democracy has been able to capitalize on better educated and economically right-wing voters (Otjes, Reference Otjes2020). On the other side of the ideological spectrum, we find the radical left Socialist Party (SP), which has also experienced a setback in the EP election, gaining just 3.4% of the votes and no seats. The party presents a democratic socialist profile and is critical of privatization and globalization. The Socialist Party qualifies as soft Eurosceptic as it attributes an excessively undemocratic and neoliberal character to the supranational institution.

Norway

The Progress Party (FrP) is a long-standing populist party in Norway. It was formed in 1973 as an anti-tax party and has been through many subsequent changes. While becoming one of the major parties in the Norwegian party system, it has remained a right-wing populist party in that its anti-establishment orientation has now become embedded in its anti-immigration position. The party has sustained a position of ambiguity on European integration as it has always mixed both pro-EU and Eurosceptic positions (Sitter, Reference Sitter, Szczerbiak and Taggart2008: 338). Its ideology is ‘a rather erratic mixture of neo-liberalism, conservatism and populism’ (Hagelund, Reference Hagelund2003: 47), and the party is less definitively on the radical right than parties elsewhere. The party came into power for the first time as a junior partner in the coalition government 2013–2017 with the Conservative Party and maintained its place in government as part of a broader moderate right coalition as a result of the 2017 election where it attained 15.2% of the vote (Aardal and Bergh, Reference Aardal and Bergh2018).

Poland

Law and Justice (PiS) is led by Jarosław Kaczyński and has been at the forefront of Polish politics for almost two decades. Since 2015, the party has ruled the country on the basis of a nativist populist platform with strong conservative positions emphasizing traditional values and frequently attacking the judiciary and liberal civil society (Szczerbiak, Reference Szczerbiak2017; Bill and Stanley, Reference Bill and Stanley2020). In 2019, Kaczyński's party significantly improved its performance at the May EP election (45.4%) and in the national election held later in October with 43.6%. However, despite an increased share of votes compared to 2015, the party lost its majority in the Senate due to a lower portion of wasted votes. PiS is a member of the ECR group in the EP. The other populist party is Kukiz’15, which centres on the former musician Paweł Kukiz. The party scored 3.7% in the 2019 EP election and ran as part of the moderate Polish Coalition (KP) in the following general election. KP gained 8.55% of the votes and Kukiz’15 overall returned six MPs. While starting out from far-right positions (at least, in light of the alliances with a series of far-right parties), Kukiz’15 has progressively moved towards milder socially conservative and economic liberal positions. Throughout his political history, Kukiz has focused his anti-establishment agenda on direct democracy and the reform of the electoral system, advocating a shift from a proportional to a majoritarian system.

Portugal

Portugal had been one of the negative cases of populism in Europe with very little evidence of parties being populist (Lisi and Borghetto, Reference Lisi and Borghetto2018; Salgado, Reference Salgado2019). A new party, Chega! (Enough!), was formed in 2019 under the leadership of André Ventura, a former member of the moderate right Social Democratic Party (Mendes and Dennison, Reference Mendes and Dennison2020). The ideology is radical right with an anti-bureaucracy and anti-tax agenda, also combined with nationalism and populism. The party is soft Eurosceptic: it stands for a Europe of the peoples and nations but rejects any dilution of European identity. Chega! contested the 2019 EP election as part of the Basta! the coalition which secured 1.5% of the vote but won no seats. In October 2019, national elections were held, which resulted in a Socialist Party government. Chega! contested the election and gained 1.3% of the vote and secured one MP.

Romania

There are no populist parties represented in the Romanian parliament in 2019. The short-lived but relatively successful People's Party – Dan Dionescu (PP-DD) dissolved after its leader was convicted for extortion in 2015. The trial had been ongoing since 2013 and Dionescu was released early in November 2017. The populist radical right Greater Romania Party (PRM) has lingered at the margins of Romanian party system since the 2000s and has continued to operate after the death of long-standing leader Corneliu Vadim Tudor in 2015. Between 2017 and 2019, his daughter Lidia tried to revive the legacy of his father acting as President of the party's National Council but left in dissent amid attempts by the party leadership to ally with the far-right United Romania Party (PRU).

Slovakia

The Slovak party system has a number of relevant populist parties. The first in order of importance is Robert Fico's Direction-Social Democracy (Smer-SD), which has dominated Slovak politics since 2006 and held government duties since 2012. Fico's party presents itself as a modern social-democratic and pro-EU force but effectively flirted with nativism in several occasions, either to make concessions to its radical right coalition partner Slovak National Party (SNS) (Pirro, Reference Pirro2015) or align with the anti-immigration stance of other governments of the Visegrád Group. The last government (2016–2020) was a coalition between Smer-SD, the radical right SNS, the ethno-liberal Most-Híd (Bridge), and the moderate right Sieť (Network). The murder of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée on 21 February 2018 deeply affected the course of government. Kuciak had been working on cases of tax fraud and misuse of EU funds, and ultimately connected operations of the Italian mob (‘ndrangheta) in Slovakia with top-level politicians of the ruling Smer-SD and Most-Híd. The issue of anti-corruption dominated the 2019 presidential and EP elections, resulting in a clear setback for Smer-SD and affiliated parties. Smer-SD returned 15.7% of the votes in the 2019 EP election – a result that has to be also related to increased turnout – coming second to the liberal coalition comprising Progressive Slovakia of President Zuzana Čaputová and SPOLU (Together), which scored 20.1%. Smer-SD is a member of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) in the EP. The right-wing Ordinary People and Independent Personalities (OĽaNO) of Igor Matovič had played a somewhat secondary role until then (5.3% in the 2019 EP election) but consistently stressed its outsider anti-establishment role. The social conservative party vows to root out corruption from the country and, while it opposes migrant relocation quotas from the EU, it is not Eurosceptic. OĽaNO is member of the EPP. Another populist party is the radical right We Are Family (SR). The party scored 3.2% in the 2019 EP election but fared much better in the 2016 general election when it gained 6.6% of the votes and 11 MPs. We Are Family is led by businessman Boris Kollár and is strongly committed to family policies, which are paired with anti-immigration and soft-Eurosceptic views. Squeezed by other competitors on the far-right end of the ideological spectrum (We Are Family and the extreme-right Kotleba's People's Party-Our Slovakia) and tainted by participation in government, the Slovak National Party failed to attain representation in the EP (4.1% in 2019).

Slovenia

Four populist parties are currently represented in the Slovenian parliament. The once-moderate Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS) currently qualifies as a populist radical right party. The party, led by Janez Janša since 1993, is a national and social conservative force committed to the free market. The SDS opposes ‘left-sponsored’ immigration, ‘false solidarity’, and multiculturalism, listing among those parties who opposed EU migration quotas at the peak of the ‘migration crisis’. The party however sees EU and NATO membership fulfiling its foreign policy goals and, while warning about the risk of EU disintegration, its stand on the EU resembles more that of other partners in the EPP group in the EP than Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán's – with whom Janša maintains close ties. The party came first in the 2018 general election (24.9%) but was not able to form a government. The SDS ran in alliance with the Slovenian People's Party (SLS) in the 2019 EP election, gaining 26.4% of the vote. The List of Marjan Šarec (LMŠ) is a new anti-establishment reformist party led by the homonymous former comedian and Kamnik mayor. Šarec launched the LMŠ after ranking second in the 2017 presidential election and scored 12.6% of the vote in the 2018 general election. His party teamed up with the Social Democrats, the Modern Centre Party, the Party of Alenka Bartušek, and the Democratic Party of Pensioners to form a minority government after the 2018 election, listing Šarec as Prime Minister. The LMŠ is a centrist social-liberal force advocating reform in different areas (e.g. electoral system, public administration, IT, environment, etc.), pledging to counter political crime and corruption, and stating that politics should serve the people and not vice versa. The party gained 15.6% of votes in the 2019 EP election and is a member of the Renew Europe group. Levica (Left) is a populist radical left party successor of the United Left alliance. Levica provided external support to the government coalition led by Šarec, and gained 6.3% of the vote at the 2019 EP election. The party stands for ecological and democratic socialism, advocating sustainability, democratic economy planning, and workplace democracy, among other things. Levica defines the EU as an ‘ordoliberal hell’ and envisages an alternative plan outside of the Union, but does not actively campaign on Slovenian exit. Finally, the populist radical right Slovenian National Party (SNS) is a quite marginal force in Slovenian politics. Founded in 1991, and still led by Zmago Jelinčič Plemeniti, the SNS returned 4% of the vote in the last EP election. The party advocates withdrawal from the EU and NATO, and thus qualifies as hard Eurosceptic. It opposes immigration from Asia and Africa and, as a result, it calls for restrictions on the foreign labour force. Although liberal for what it concerns abortion and religious creed, the SNS firmly opposes same-sex marriage and Islam.

Spain

Long regarded as a case of far-right exceptionalism (Alonso and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Alonso and Rovira Kaltwasser2015; Mendes and Dennison, Reference Mendes and Dennison2020), Spain has only recently seen the rise of a populist party on the far-right end of the ideological spectrum. After returning four MEPs in the 2019 EP election (6.2% of votes), the radical right VOX (Voice) improved its standing at the snap national election of November 2019, where it gained 15.1% of the vote. The party had scored 10.3% in the previous national election held in April 2019. VOX emerged as a split from the right-wing People's Party in 2013 and made its first significant inroads in Andalusia in 2018. The party preserves some specificities proper of the Spanish context. On top of its opposition to multiculturalism and immigration, VOX indeed stands for the abolition of autonomous communities. The party is economically liberal and soft Eurosceptic with regard to Spanish EU membership. In line with its traditionalist outlook, it is anti-feminist and firmly rooted in the Catholic heritage of Spain. VOX is a member of the ECR group. On the other side of the ideological spectrum, there is the populist left Podemos (We Can). The party contested the 2019 EP election in alliance with the United Left and other parties of the left as Unidas Podemos (feminine for ‘United We Can’, UP), gaining 10.1% of the votes.Footnote 11 In the two national elections held in 2019, it scored 14.3 and 12.8% of the vote, respectively. Podemos stems from the Spanish 15-M movement and is a populist anti-establishment party with a democratic socialist and libertarian agenda promoting equality, environmentalism, and civil rights. After the November 2019 election, UP joined the Spanish Socialist Worker's Party to form a government coalition. Podemos is a member of the European United Left group in the EP.

Sweden

Sweden has currently one party that can be classed as populist. Sweden Democrats (SD) is a long-standing party that has come in from the margins of politics in recent years (Widfelt, Reference Widfeldt2008) to grow in support and become an important parliamentary force. The party is radical right with a socially conservative and nationalist agenda, and strong anti-immigrant and Eurosceptic views. It draws from working-class former social-democratic voters (Oskarson and Demker, Reference Oskarson and Demker2015). It was only in January 2019 that the national election held in September 2018 gave rise to a (Social Democratic Party led) government. The profound difficulties of forming a coalition were in no small part due to the new parliamentary arithmetic thrown up by the success of the SD in that election, with 17.5% of the vote and 62 parliamentary seats (Aylott and Bolin, Reference Aylott and Bolin2019). Many of the difficulties in forming a stable coalition stemmed from the divisions between and within parties as to whether any sort of support from SD was to be countenanced. In January 2019, SD shifted from a hard- to a soft-Eurosceptic position in the light of Brexit and gained 15.3% of the vote in the subsequent EP election. Here, SD sits with the ECR group.

Switzerland

The largest party in Switzerland is the Swiss People's Party (SVP), which is a long-standing populist radical right party with a strong anti-immigrant agenda and a hard-Eurosceptic position. The nature of the Swiss political system effectively guarantees the top five parties membership of government and so the SVP has been represented in government (Federal Council) for many years. In 2019, the Swiss federal election saw the SVP as the most successful party with 25.6% of the vote but this was seen as a setback as the vote share had dropped since the last election in 2015. In office, the party had been frustrated in its hard-line efforts to limit immigration as other parties supported a softer position designed to sustain Swiss-EU relations (Bernhard, Reference Bernhard2020). In addition to the SVP, there are two other parties that can be considered populist – the Ticino League (Lega) and the Federal Democratic Union of Switzerland (EDU). These are relatively small parties that attained 0.8 and 1.0% of the votes, respectively, in the 2019 election. The Lega is a populist regional nationalist party (Albertazzi, Reference Albertazzi2006) seeing itself as representing the interest of Ticino residents against the Swiss state, and has long been hard Eurosceptic (Mazzoleni and Ruzza, Reference Mazzoleni and Ruzza2018). The EDU is a right-wing populist party with a fundamentalist protestant perspective and a hard-Eurosceptic position. The once-relevant populist radical right Geneva Citizens' Movement (MCG) promotes a leaner state as well as small and medium enterprise; it has a tough stance on immigration, and stands for an independent and sovereign Switzerland within a confederal Europe (i.e. hard Euroscepticism). In 2019, the party lost its only seat in the National Council, scoring 0.2% of the vote.

United Kingdom