Scholars have long viewed the history of the Vietnam War as deeply entwined with the history of the Vietnamese Revolution. But what was this revolution, when and how did it begin, and what were its defining features? While some have depicted the revolution as the culmination of a centuries-long process of national formation, many more have depicted it as a reaction to colonial rule and the creation of French Indochina during the last decades of the nineteenth century. Recently, however, postcolonial scholars have critiqued the view of the Vietnamese Revolution as nothing more than a “response” to European conquest. This chapter does not seek to identify a singular moment of revolutionary origins, nor does it depict Vietnam’s revolution as a necessary or inevitable response to “foreign invasion.” Instead, I chart the complex political, economic, and cultural changes that transformed Indochina between the 1860s and the 1920s, paying particular attention to the strikingly different effects that these changes produced in the five regions (pays) of France’s colonial empire. By 1930, many Vietnamese had embraced revolution, but the implications and direction of the country’s revolutionary politics – and the fate of colonial rule in Indochina – appeared more uncertain than ever.

Vietnam on the Eve of French Conquest

Contrary to what some later observers supposed, the colonial-era division of Vietnam into the three regions of Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina was not a French innovation. It replicated the administrative structure devised by Emperor Gia Long when he established the Nguyễn Dynasty in 1802. Gia Long’s newly unified empire was much larger than the realm that his ancestors had established in the coastal region below the 18th parallel two centuries earlier, when they separated from the northern Viet kingdom based at Hanoi. While Gia Long’s court, now located in Huế, ruled the central region directly, one viceroy was appointed for the North and another for the South. The position of northern viceroy was abolished in 1817 but that of southern viceroy lasted until 1832. By the time the Nguyễn kingdom first came under French attack in 1858, the empire had been administratively unified for only twenty-four years. Still, the memories of this unity would nourish nationalist sentiments in the twentieth century.

Despite its heavy reliance on revenues from mining in the Northern Highlands,Footnote 1 the Nguyễn Dynasty idealized the village-based agrarian society of the Red River Delta. In northern villages, distrust of outsiders accompanied communal solidarity. Rural trade was hampered by geography and seen mostly as a remedy for poverty.Footnote 2 For ordinary residents, the path out of both village and poverty was through education and bureaucratic appointment. But in the central region with its long coast and lack of arable land, the Nguyễn ancestors to the nineteenth-century emperors had maintained the Cham tradition of long-distance maritime trade. Meanwhile, since the late seventeenth century, an influx of Chinese immigrants made possible the expansion of Nguyễn rule southward, into the fertile Mekong Delta. In response to demand for rice in Southeast Asia, canals were dug to drain swamps, bring new land into cultivation, and facilitate the transport of rice to Saigon for export.Footnote 3 In this ever-changing landscape, Vietnamese, Chinese, and Khmer peasants were constantly on the move. Unlike their northern and central counterparts, southern villages were open but lacked the former’s communitarian ethos. A scarcity of imperial officials and Confucian educators hampered the court’s efforts at administrative control and ideological conformity. Economic success rather than educational achievements and bureaucratic appointment was the chief means of social advancement. French colonial policies would exacerbate these pre-existing regional differences.

French Cochinchina Before 1885

The ill-defended southern region was the first to fall to French conquest. In 1862, the Treaty of Saigon ceded the region’s three eastern and most populous provinces to the French. In 1867, having already installed a protectorate in Cambodia in 1864, the French seized the remaining three provinces of the west. The flight of Vietnamese officials to the still-independent northern and central regions contributed to turning the Vietnamese south into the colony of French Cochinchina.

Under French rule, Cochinchina was first divided into thirteen then eventually twenty provinces. Each was governed by a French administrator. Below him were other French officials; Vietnamese were only allowed to perform clerical duties or to hold purely honorific titles. At first, the colony was governed by an admiral. In 1879, after Jules Ferry became French prime minister, a civilian governor was appointed by Paris and an elected Colonial Council was created to make the governance of the colony more democratic. Only six of the Council’s fourteen (eventually eighteen) members were Vietnamese and these were elected by a restricted pool of property-owning electors. The Colonial Council sent one delegate to the Chamber of Deputies in Paris. When France decided to resume expansion in Vietnam, the settlers objected to using the Cochinchinese budget to fund the Tonkin campaign of 1883–5. Paris reacted by replacing the colony’s first civilian governor, le Myre de Vilers, with a more compliant one.Footnote 4

Colonialism’s economic impact on the economy of Cochinchina was immediate and long-lasting. From the outset, the French had systematically seized lands whose owners had fled the conquest or who had stayed to oppose them. Once the western provinces of the Mekong Delta were annexed, agricultural settlements that had been opened to bring more land under cultivation were also confiscated on the grounds that their ownership had been transferred from the Court to the new authorities. The pre-existing network of canals was greatly expanded.Footnote 5 To hasten large-scale export-oriented agriculture, lands, either confiscated or newly brought into cultivation, were auctioned off as lots whose size and price put them out of the reach of ordinary Vietnamese. Many small cultivators lacked proper titles for the lands they had reclaimed and lost them to unscrupulous speculators and corrupt officials. Scandals associated with land grabbing were a recurring theme of southern politics throughout the colonial period. The growth of large landholdings encouraged the twin phenomena of landlessness and absentee landlordism.Footnote 6

Other far-reaching changes came in the realm of culture. The system of Confucian education, culminating in bureaucratic employment, held little attraction for the southern peasants and merchants. It was thus easy to jettison the traditional curriculum. The earliest French-affiliated institution of new learning, the Catholic Collège d’Adran, was founded in 1861 even before the Treaty of Saigon was signed. By 1869, Cochinchina counted 126 public schools where Vietnamese students were taught in the Romanized script (quốc ngữ). After the third grade, students could transfer to more advanced schools in which the language of instruction was French, though few did. The first such school, the Collège Chasseloup-Laubat, opened in Saigon in 1874. In 1879, the Collège de Mỹ Tho was established on the prior foundation of a primary school to serve the needs of students from the Mekong Delta. In 1882, Jules Ferry mandated universal education in France and pushed for opening more public (and secular) schools in the colonies.Footnote 7 New Franco-Annamite schools were thus opened throughout Cochinchina – though they catered mainly to the children of wealthy Vietnamese and Chinese (Figure 2.1).

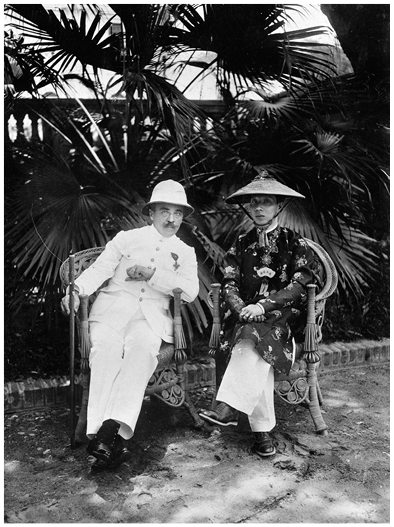

Figure 2.1 The governor-general of French Indochina, Albert Sarraut, with Emperor Khai Dinh of Annam (April 1918).

In 1865, the Vietnamese Catholic polymath known as Petrus Trương Vĩnh Ký began publishing Gia Định Báo (Gia Dinh Journal). Printed in quốc ngữ, it functioned as an unofficial journal of record. Besides official notices and legal documents, the weekly journal, which ran until 1897, published articles on agriculture and culture.Footnote 8 Beginning in 1879, all official documents were issued in French and quốc ngữ, thereby cementing the latter’s use as the script for communicating with and among Vietnamese. By the time French colonial conquest resumed in the rest of the country in 1882, the Vietnamese south had already experienced profound political, economic, and cultural transformations that magnified previous differences with the rest of the country.

The Conquest of Tonkin and Annam

After the French annexation of the southern provinces, the rest of the country fell prey to economic difficulties, rebellions, and factionalism among court officials. Owing to the chronic indecisiveness of Emperor Tự Đức (1847–83), his court failed to take advantage of the hiatus in France’s colonial expansion between its defeat in the war with Prussia of 1870 and Jules Ferry’s assumption of the premiership in 1879. Although the Vietnamese court had previously sought assistance from China in vain, in 1883, a new appeal found a favorable response among conservative Qing officials, leading to war between France and China. But the Sino–French war ended badly for Vietnam. The Treaty of Tianjin of June 1885 affirmed the French annexation of the remaining Vietnamese territory and its division into the protectorates of Tonkin and Annam in the North and center respectively.

The following month, several attempts to restore the Nguyễn monarchy to power, known collectively as the Aid the King Movement (Cần Vương), were launched.Footnote 9 Imperial regents whisked the twelve-year-old emperor Hàm Nghi to the hills of central Vietnam to lead the struggle, but his absence from the court gave the French a pretext to enthrone his elder half-brother Đồng Khánh. From Đồng Khánh onward, Vietnamese emperors ruled in name only, with effective power residing in the hands of French officials.

In 1887, the colony of Cochinchina and the three protectorates of Cambodia (since 1864) and of Tonkin and Annam (since 1885) were brought together in a new entity, the Indochinese Union, to which Laos was added in 1893. A governor-general was appointed at the head of the Union, above the governor of Cochinchina and the French résidents supérieurs of the four protectorates. Although the governor-generals initially resided in Saigon’s Norodom Palace (later Independence Palace), the capital of the Union was moved to Hanoi in 1902.

Although the traditional imperial bureaucracy was preserved in both Tonkin and Annam, each protectorate had its own political and administrative regime that was headed by a French résident supérieur. In Tonkin, each province remained nominally administered by a Vietnamese governor (tổng đốc), but actual power was exercised by a French résident, the equivalent of a Cochinchinese administrator. The résident supérieur governed with the assistance of an advisory council that, unlike the Cochinchinese Colonial Council, was neither elected nor endowed with the power of the purse. In Annam, the seat of the Nguyễn court, there was no French administrator below the résident supérieur. But that official had total, if indirect, control over the Nguyễn court bureaucracy. He presided over meetings of the imperial cabinet and set their agenda. Vietnamese ministers were barred from introducing any new item for discussion and were especially prohibited from discussing matters of personnel or taxes, including their amount, collection, or distribution.

During these decades, few Vietnamese living in Tonkin or Annam ever saw a French official or settler. They experienced colonialism indirectly as Vietnamese prefects and magistrates continued to discharge their functions as before, albeit while taking their orders from the colonial rather than imperial state.Footnote 10 While Vietnamese officials were subservient to the French authorities, many abused the power they wielded within their local jurisdictions. As a result, in the two protectorates, traditional governance – and the Confucian ideology on which it was supposedly based – became indelibly and negatively associated with colonial rule.

When the Aid the King Movement ended in 1895, the Indochinese government switched from pacification to economic exploitation. In 1897, a new governor-general, Paul Doumer, set about reforming the Indochinese budget, which depended heavily on subsidies from the metropole. He introduced new taxes, including monopolies of opium and salt. Later, alcohol was added to these two sources of revenue (although policing them turned out to be quite costly).Footnote 11 A new bureaucratic apparatus, the general services, was created to administer projects that transcended state borders, but also to solidify the position of the governor-general over the heads of the five states of Indochina, in particular the governor of Cochinchina. The colony contributed 40% of the Union’s budget; consequently, the Cochinchinese settlers and their representatives in both Saigon and Paris exerted enormous power over the affairs of the Indochinese Union. The general services enabled the governor-general to siphon off revenues from Cochinchina, mitigate the influence of the settlers, and restrict the power of the governor of Cochinchina.

In Tonkin and Annam, land plots tended to be small and property registers were better kept than in the developing Mekong Delta and thus did not attract land speculators. The socioeconomic landscape changed more gradually than in Cochinchina, but the new taxes weighed more heavily on their inhabitants than on those of the South, where greater social (and geographical) mobility accompanied rapid development. Although the colonial administrators stopped above the village level, French rule had a profound impact on rural life in both regions. Peasants in Tonkin and Annam existed at subsistence level, their crops often mortgaged before they had ripened, in order to pay their taxes. In the early 1880s, the colonial authority introduced a series of measures to increase tax revenues. First, the census, which determined the amount of taxes owed by each village, was no longer conducted by village councils but by agents of the state. It was no longer possible for the councils to minimize their villages’ tax liability by underreporting population figures. The traditional distinction between registered peasants who had the right of citizenship in their village and those who were nominally exempted from taxes because of their supposedly transient status (a situation that could persist over three generations) was gradually eliminated; every villager was now a taxpayer. Furthermore, a new tax was introduced as replacement for the traditional corvée, which was usually performed by villagers in the offseason and close to home. As the large-scale projects undertaken by the general services required year-round manpower, coerced labor details known as corvée remained a hated feature of rural life until the end of the colonial period. Under the new system, peasants were forcibly recruited, even kidnapped, to work on projects far from home for long periods and were severely punished for breaking contracts.Footnote 12

While they no longer conducted the census, village councils remained responsible for collecting taxes and remitting them in full. The introduction in 1897 of tax receipts as forms of identification opened villagers to new exploitation by village councilmen. Having previously served as buffers against the imperial state, they now became reviled as rapacious agents of the colonial regime. In 1927, the colonial regime introduced a measure to shore up the representativeness of village councils in Tonkin, but their prestige continued to decline. Throughout the 1920s, the northern Vietnamese press routinely called for reforming village government.

Reform and Collaboration

The end of the Aid the King Movement coincided with Japan’s victory over China in 1895. These two events convinced the traditionally trained scholars who made up the leadership of the movement to abandon its purely restorationist objectives and to embrace cultural reform as a prerequisite for independence. Inspired by Chinese reformers such as Liang Qichao, they jettisoned the ideal of social harmony as the organizing principle for society and replaced it with Social Darwinian notions of racial competition. They accepted that Vietnam had fallen to colonial conquest because its civilization had become stagnant and unable to compete against a more vigorous West.

The first advocate of reform was Phan Bội Châu (1867–1940). After the end of the Aid the King Movement in which he had played a minor role, he concentrated on his studies and obtained a degree in the regional examinations of 1900. In 1903, he penned the first of his appeals for reform. This was A New Letter from Ryukyu Written in Blood and Tears (Lưu Cầu Huyết Lệ Tân Thư). In it, he drew parallels between the loss of Ryukyu’s annexation by Japan in 1879 with Vietnam’s own loss of independence to the French. He echoed Chinese reformers’ calls for immediately developing the people’s intellect and cultivating the people’s strength. The following year, he created the Reform Society (Duy Tân Hội) whose main activity was the Eastern Travel Movement (phong trào Đông Du), aimed at bringing young Vietnamese to Japan to acquire a more modern education than was available in Vietnam. The most noteworthy of these students was Prince Cường Để (1882–1951), a direct descendant of the Nguyễn dynastic founder. But while the aim was to send students abroad from the two protectorates, most of the Vietnamese who joined the Eastern Travel Movement came from the more prosperous South. This pattern of southern support for Phan Bội Châu would continue throughout the first decades of the twentieth century and shape his politics. Not long after his arrival in Japan, Phan Bội Châu wrote another pamphlet, A History of the Loss of Vietnam (Việt Nam Vong Quốc Sử) for which Liang Qichao wrote a preface. Liang also had it printed and distributed as far as Korea. Both the New Letter from Ryukyu Written in Blood and Tears and the History of the Loss of Vietnam were written in classical Chinese, the language in which Phan Bội Châu had been educated. Although an ardent advocate of quốc ngữ, he never learned it.

The other towering figure of the reformist movement, Phan Châu Trinh, likewise wrote in Chinese. Born in 1872, Phan Châu Trinh had been too young to participate in the Aid the King Movement. His father had, however, been assassinated by fellow insurgents. Unlike Phan Bội Châu who was willing to resort to violence in the pursuit of independence, Phan Châu Trinh renounced it entirely. Blaming the monarchy for his father’s assassination, he became an ardent advocate of republicanism. And while Phan Bội Châu saw cultural reform in purely utilitarian terms as a useful instrument for political action, Phan Châu Trinh believed that independence could only be sustained after a thorough process of cultural change that might last decades. To the dismay of Phan Bội Châu, whom he met in both Japan and China, he distrusted Japan and was willing to learn from the French.Footnote 13 In 1907, Phan Châu Trinh became involved in the Tonkin Free School Movement (Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục) which advocated the spread of quốc ngữ as a bridge between the elite and ordinary Vietnamese. The Tonkin Free School operated impromptu classes that not only taught quốc ngữ but also introduced new ideas from East Asia and Europe. Several of its leaders were graduates of the School of Interpreters that had opened in Hanoi in 1886 to train intermediaries between the French authorities and imperial officials. The school’s curriculum combined a smattering of Chinese, quốc ngữ, and French with new subjects of study, so its graduates became known as scholars of New Learning. Some members of the Tonkin Free School also opened businesses, both to provide financial support for its operations and to elevate the status of trade and traders.Footnote 14

The reforms advocated by the Tonkin Free School aimed to replicate developments in Cochinchina, where the use of quốc ngữ was widespread and commerce and entrepreneurship had always enjoyed popularity. Gia Định Báo had ceased publication in 1897, but some of its mission was resumed in 1901 with the launching of a new journal, Nông Cổ Mín Đàm (Forum for Agriculture and Commerce). Like Gia Định Báo, it was written entirely in quốc ngữ. It had few paid subscribers but a wider readership. As its title indicated, it aimed to promote the interests of Vietnamese farmers and businesspeople. It provided regular information about the price of rice for export and advice on agricultural matters, but it also devoted columns to cultural issues. It published translations of Chinese historical novels such as the Romance of the Three Kingdoms and short stories from Chinese, French, or English, as well as original poems; it also reproduced news from European newspapers. Fully two pages were taken up by advertisements. There was nothing like it in Tonkin or Annam.Footnote 15

The reformers’ educational enterprise included a significant innovation. Women had traditionally been barred from taking the civil service exams; their education had been limited and haphazard, focusing mainly on moral prescriptions and domestic advice. It turned out that women, who were not tied to a Chinese-language education, were quicker learners of the Romanized script than the men. Thus, when he found out that his daughter was already fluent in the new script, Lương Vӑn Can put her in charge of the women’s section of the Tonkin Free School.Footnote 16

A Collège du Protectorat (colloquially known as Trường Bưởi) was established in 1908 in Hanoi to cater to Vietnamese students. In Huế, the Imperial Academy (Quốc Học) was founded in 1896, but it began actual operations only in 1909. The limited availability of Franco-Annamite education in Tonkin and Annam was due not only to their protectorate status but also to the persistence of the traditional civil service exam system as the means of staffing the imperial bureaucracy. The system continued to function for an entire decade after its abolition in China. The last regional exams were held in the North in 1915; but only in 1919 was the last metropolitan exam held in Huế.

In addition to building new institutions, the reformers also sought to transform Vietnamese mores. They encouraged their peers to cut their hair and nails short and embrace Western-style modernity. Paradoxically, in the South, where all the measures advocated by northern reformers had long taken hold, some chose to express their patriotism by clinging to traditional hair and clothing styles and to profess allegiance to the Vietnamese monarchy that no longer reigned over the colony.

For all the publicity it generated then and later, the Tonkin Free School Movement lasted only one year. In 1908, the last significant armed revolt against French conquest ended after a plot to poison the colonial garrison in Hanoi was uncovered and its mastermind, Đề Thám, was captured. The same year, peasants in Annam staged protests against the corvée and against the introduction of a new currency that severely disadvantaged them. Leaders of the Tonkin Free School lent their support by writing poems and songs that the colonial authorities deemed subversive. Phan Châu Trinh and other supporters of the protests were arrested and the classes of the Tonkin Free School were shut down. The University of Hanoi (actually School of Medicine), which had opened in 1902 to address Vietnamese calls for educational reforms, was also shut down and did not reopen until 1917. Scholars of New Learning such as Nguyễn Vӑn Vĩnh and Phạm Duy Tốn, who had enthusiastically embraced the Movement because it vindicated their own educational trajectory, took fright. While many continued to pursue cultural endeavors, they largely ceased to be involved in what might be deemed political activism.Footnote 17

Meanwhile, in 1909 Phan Bội Châu was expelled from Japan at the behest of the French colonial authorities. After wandering in Siam (where many former participants in the Aid the King Movement had taken refuge) and Hong Kong, Phan Bội Châu settled in South China. He quickly immersed himself in the political activities of the Vietnamese émigrés there as well as in Chinese politics. An enthusiastic supporter of the 1911 Revolution that ended Manchu rule over China, in 1913, he tried to form an anticolonial movement that drew its inspiration from Sun Yat-sen’s Revolutionary Alliance (Tongmenhui). However, its proposed republican platform encountered opposition from his southern supporters who furnished him with the bulk of his funds. To placate them, he placed prince Cường Để at the head of the League for the Restoration of Vietnam (Việt Nam Quang Phục Hội). Seeking to publicize the new organization, he encouraged a bomb plot in the Saigon–Cholon area. This was carried out through the intermediary of the clandestine Heaven and Earth Society. The Society, which originated in China, had replaced its anti-Manchu slogan (“Fight the Qing, Restore the Ming”) with an anticolonial one (“Fight the French, Restore Vietnam”). Phan Xích Long, the local mastermind of the bomb plots, was arrested before the plot could be carried out while Phan Bội Châu was sentenced to death in abstentia.Footnote 18 The French authorities were able to convince the governor of Guangdong to arrest him, but not to deport him back to Vietnam. Phan Bội Châu spent the next four years in a Chinese prison.Footnote 19

These waves of anticolonial activity made it difficult for the new governor-general, Albert Sarraut (Figure 2.2), who arrived in Indochina in 1911, to implement his program of economic development (mise en valeur) of the colonies. Sarraut’s plan relied on mollifying native populations with concessions to promote social stability. But it soon ran afoul of the French settlers’ belief that social unrest should be met with severe reprisals. By the time ill-health forced Sarraut to return to France in 1913, he had not been able to accomplish much in the way of reforms, though he succeeded in releasing Phan Châu Trinh from prison. Phan Châu Trinh left for Paris and was even given a subsidy (it was withdrawn when World War I broke out).

Figure 2.2 A Franco-Annamite school in Đồng Khê (Upper Tonkin) in 1902.

French Indochina initially refused to become involved in the metropole’s war with Germany but changed course in 1915. The government immediately set about rounding up “volunteers” to serve on the front or relieve French workers in factories. Eventually, 94,000 such volunteers, the overwhelming majority coming from Vietnam, went to France during the Great War.Footnote 20 Although they were supposed to go of their own free will, in fact, most were conscripted, sometimes even kidnapped. Riots broke out throughout the country. In Cochinchina, anticonscription protests merged with an attempt by members of the Heaven and Earth Society to spring Phan Xích Long out of the Central Prison of Saigon in 1916. Eventually, thirty-eight men involved in that failed attempt were publicly executed. In Annam, too, political unrest was rife. The sixteen-year-old Emperor Duy Tân was persuaded by a Taoist scholar, Trần Cao Vân, to plot an attack on French military installations in Annam. When the scheme was discovered, Duy Tân was sent into exile together with his father Thành Thái, whom the French had deposed in 1907 after he called on the French to restore prerogatives that by treaty were supposed to be reserved for the court.

In August 1917, a revolt took place among colonial troops stationed in Thái Nguyên in the north. The insurgents made common cause with some of the political prisoners detained in the prison, notably Lương Ngọc Quyến, the son of the reformist scholar Lương Vӑn Can. The authorities dealt with the uprising with ferocious intensity, mobilizing 500 troops who, in the space of five days, razed the town that had given shelter to the insurgents.Footnote 21 The French authorities and settlers usually described incidents of unrest as either expressions of opposition to colonialism (as would Vietnamese historians later) or as purely local disturbances caused by dissatisfaction with specific policies. In the case of the Thái Nguyên uprising, there was ample reason to lay the blame on the French résident, Darles, who mistreated both prisoners and colonial troops equally. At the same time, the presence of political prisoners also suggested that the uprising had been inspired in part by anticolonial sentiments. Albert Sarraut, who had arrived back in Indochina in January 1917, chose to interpret the uprising as a purely local affair. It is likely that his choice was motivated by his desire to implement the program of “Franco-Annamite collaboration” he had proposed prior to the war (Figure 2.2).

The New Journalism: Politics vs. Culture

The post–World War I situation made Sarraut’s program of collaboration seem more necessary and more possible. Even after Governor-General Paul Doumer had tried to put the finances of Indochina on a sounder footing, the colony had continued to depend on subsidies from the metropole. Given the parlous state of the postwar French economy, reducing Indochina’s financial dependence on Paris was imperative. Sarraut proposed to institute a constitution that would give Indochina greater independence from Paris in return for becoming financially self-sufficient. The colonial state also faced a dearth of European personnel, due to the staggering casualties sustained on the battlefields of Verdun and the Somme.Footnote 22 This meant appointing Vietnamese to positions hitherto reserved for French people. It also spurred educational reforms that greatly increased the number of schools in Cochinchina and extended the system of Franco-Annamite education to Tonkin. In Annam, where the last traditional metropolitan exam was held in 1919, the classical curriculum was reformed to purge it of anticolonial elements. In a bow to girls’ education, the Đống Khánh School opened in Huế in July 1917.Footnote 23

To advance his program, and to counter the opposition of the French settlers that was even more virulent than in 1913, Sarraut courted the Vietnamese elites of Cochinchina and Tonkin with notable success. In Cochinchina, the rising middle class had achieved political visibility by enthusiastically voicing its patriotism toward “the mother country” (mẫu quốc) of Great France (Đại Pháp) and buying war bonds. Sarraut’s main supporter was Bùi Quang Chiêu, whose biography suggests the educational gulf that existed between Cochinchina on the one hand and Tonkin and Annam on the other. Bùi Quang Chiêu was born in Bến Tre in 1867, the same year as Phan Châu Trinh. But while Phan Châu Trinh in Quảng Nam received a traditional education culminating in a degree in 1902, Bùi Quang Chiêu went to Algeria in 1894 and graduated three years later with a degree in agronomic engineering. Back in Vietnam, he was an enthusiastic supporter of the reform movement, particularly of the Tonkin Free School. Albert Sarraut tapped him to become the editor-in-chief of the French-language newspaper La Tribune Indigène for which the colonial regime provided generous subsidies (paid for by villages, which were required to purchase the newspaper though their residents were largely illiterate even in their own language). In 1919, the newspaper announced that it was the organ of the Constitutionalist Party and openly supported Sarraut’s attempt to forge an Indochinese constitution. The newspaper benefited from the policy of relative press freedom that allowed French-language newspapers to discuss economic and political matters. La Tribune Indigène advanced the interests of Vietnamese landowners and businessmen against both the French settlers who had their own mouthpieces in several newspapers and against the Chinese businessmen who dominated the economic sector, especially the rice trade. In 1919, the newspaper spearheaded a boycott of Chinese businesses. Bùi Quang Chiêu had another target: the poor and uneducated. He had become a believer in Social Darwinism as an explanation for personal success or failure. He used his newspaper to campaign for greater Vietnamese representation on the Cochinchinese Colonial Council but feared that the illiterate peasants who had gone to France as “volunteers” would be rewarded for their war service with the right to vote when they returned. Their sheer numbers would dwarf those of the Vietnamese businessmen and landowners who were eligible to vote on the basis of their education and wealth. The Constitutionalist Party was never a mass organization.Footnote 24

In Tonkin, the elite was still dominated by graduates of the civil service exam system and the press operated under a far stricter regime than in Cochinchina. It was prohibited from discussing political matters (interpreted broadly to include economic affairs as well). Sarraut entrusted a new journal, Southern Wind (Nam Phong), to Phạm Quỳnh (1892–1945), a graduate of the Lycée du Protectorat who had begun working at the EFEO at the age of sixteen years old. Nam Phong was launched in July 1917. Nam Phong originally had three sections: a summary in French, a short section in Chinese, and a longer one in the Romanized script. Gradually, the Chinese section shrank as the quốc ngữ section grew. Unlike the southern press, which openly debated economic and political issues and showed little interest in questions of culture, Nam Phong concentrated on cultural issues. Phạm Quỳnh was a proponent of innovation in literature and especially of fiction as more than a vehicle for entertainment. The journal was also a platform for discussing the question of women in debates that pitted modernity against tradition, patriarchy against youth. While Southerners did journalistic battle with hard-line settlers, Chinese traders, corrupt politicians, and land speculators, Nam Phong was the mouthpiece of the emerging generation of graduates of the Franco-Annamite schools in the North who sought to supplant the classically trained scholars as the new elite. The closest that Nam Phong came to political debates was on the topic of reforming village councils. But these were also couched in the language of cultural reform, villages having become, in the eyes of their modernizing detractors, repositories of outmoded and oppressive customs.Footnote 25 Sarraut made no effort to win over the even more conservative elite of Annam. It was only in 1927 that the newspaper Tiếng Dân (The People’s Voice) was launched by Huỳnh Thúc Kháng, a classical scholar who had taken part in the Reform movement of 1908.

By the time Sarraut left for France in 1923, he had not succeeded in implementing an Indochinese constitution, but he had profoundly altered the terms of political discourse among Vietnamese. In Cochinchina, La Tribune Indigène became the dominant voice of the Vietnamese who espoused Franco-Annamite collaboration though few went as far as Bùi Quang Chiêu in calling for total assimilation. While Bùi Quang Chiêu enthusiastically supported landowners and businessmen, Nguyễn Phan Long, his successor as editor-in-chief of the newspaper, championed the interests of Vietnamese civil servants and other professionals whose numbers had risen in the aftermath of World War I. In the constantly developing south, La Tribune Indigène took for granted the profound changes in the social structures and culture of the region. The opposite was true of Southern Wind which, forced to eschew political and economic matters, concentrated on discussing and even advocating cultural reforms.

Radicals on the Rise

Not every Vietnamese subscribed to Sarraut’s paternalistic view that they were not yet ready for self-rule. New kinds of anticolonial activists were emerging in France and China, as well as in Vietnam. In France, sometime during World War I, the exiled Phan Châu Trinh met up with Phan Vӑn Trường, a lawyer married to a Frenchwoman. In 1917, they were joined by Nguyễn Tất Thành (soon to be better known as Nguyễn Ái Quốc and later as Hồ Chí Minh) who had arrived in Paris from London. Nguyễn Tất Thành had left Vietnam in 1911 at the age of twenty-one (according to his official biography) and worked as a sailor then as a cook in hotels in various countries. Inspired by Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points of January 1918, the three men drafted a document entitled “Revendications du Peuple Annamite” that they signed with the collective name Nguyễn Ái Quốc (Nguyễn the Patriot?). They sent this document, which called for home rule for Vietnam, to all the senior Allied leaders at the Versailles Conference in 1919. None responded. On behalf of the trio, Nguyễn Tất Thành took copies of the document to all the Paris newspapers. Only that of the Socialist Party, L’Humanité, agreed to publish the text of the Revendications. Nguyến Tất Thành was also warmly welcomed into the Socialist Party by Jean Longuet, a grandson of Karl Marx. From then on, the name Nguyễn Ái Quốc was exclusively attached to him.

At the Congress of the French Socialist Party held in Tours in July 1920, Nguyễn Ái Quốc, who had been invited to attend despite not being a French citizen or subject (he was born in Nghệ An, Annam), decided to join the breakaway Communist Party because it seemed more interested in colonial problems than the socialists. He read Lenin’s “Theses on the National and Colonial Question,” in which Lenin connected imperialism to capitalism but also predicted that colonies, as the weak links of capitalism, would end the domination of colonial powers. Nguyễn Ái Quốc was assigned to edit the party’s paper Le Paria (The Pariah) but eventually became disenchanted with what he saw as the party’s indifference toward workers and colonial people. He left some time in 1923 for Moscow, re-emerging in late 1924 in Guangzhou.Footnote 26

Also in 1923, twenty-three-year-old Nguyễn An Ninh, the son and nephew of anticolonial activists, returned to Saigon from France with a law degree and a burning desire to inspire Vietnamese youth to action. He launched a French-language newspaper, La Cloche Fêlée, which took aim at the financial scandals that plagued French Cochinchina in the postwar years. But his main goal was to urge young Vietnamese to achieve their personal independence from family and tradition by working for the independence of the nation. Unlike Southern Wind, which was respectful toward Confucianism, Nguyễn An Ninh portrayed Confucianism as a straitjacket that prevented the Vietnamese from being creative and self-reliant. While his advocacy of change was ardent, his actual program of action was rather vague. But he became an object of adulation among young Vietnamese who passed his newspaper from hand to hand clandestinely. He also gained support not only in Saigon but also in rural areas, belying the limited number of copies his newspaper sold. Of the Saigon-based activists and journalists, he was nearly the only person who sought to mobilize workers.Footnote 27

In 1924, Phạm Hồng Thái, a native of Tonkin, tried to assassinate Governor-General Merlin during his visit to the French concession in Guangzhou. His attempt having failed, Phạm Hồng Thái committed suicide, but his deed resonated among the expatriate population in southern China. Soon thereafter Nguyễn Ái Quốc, newly trained in revolutionary strategy in Moscow, arrived in Guangzhou as a representative of the Comintern. He founded the Vietnam Revolutionary Youth League (Việt Nam Thanh Niên Cách Mạng Đồng Chí Hội) with the aim of training patriotic young men and women in anticolonial activism. At the core of the League was a secret group that was meant to be the nucleus of an eventual communist movement.Footnote 28

In 1926, the Revolutionary Youth League received a sudden influx of recruits thanks to a fortuitous concatenation of events. In 1925, Phan Bội Châu was arrested in China and brought back to Hanoi for trial. The hard-line settlers scheduled his trial for 1926 to embarrass the new governor-general, Alexandre Varenne, who had a reputation as a liberal. Then in March of that year came news of the death of Phan Châu Trinh. He had been suffering ill health for several years but had not dared return to Vietnam until the death in 1925 of Emperor Khải Định, whom he had offended three years earlier by publishing a list of his “crimes.” Phan Châu Trinh never was in good enough health to return to his native Quảng Nam and died in Saigon. On the day his death was announced came news that Nguyễn An Ninh had been arrested for distributing inflammatory anti-French leaflets. The trigger for his action had been the deportation of a Vietnamese activist from Tonkin who had been agitating on behalf of workers.

The conjunction of these three events galvanized young Vietnamese, especially students at Franco-Annamite schools. They asked for permission to organize a state funeral for Phan Châu Trinh, taking as their inspiration the funerals for Sun Yat-sen in 1924 (themselves inspired by the funerals of Lenin in 1922). Denied permission to attend the funerals, they staged strikes or wore black armbands. These shows of patriotism, which spread from Cochinchina to Tonkin and Annam, and lasted through the following year, led to their expulsion from schools ranging from the Collège de Cần Thơ in the Mekong Delta to the Đồng Khánh School for girls in Huế and to vocational schools in Tonkin. Many of the expelled students joined underground organizations in Vietnam; others made their way to France or to China. In France, where the most Southerners went, newcomers had an array of organizations to choose from, including the French Communist Party and more moderate groups. Some went on to Moscow for training. France had emerged as the capital of international Trotskyism in the wake of Stalin’s purge of Trotsky and a few Vietnamese students became Trotskyists. From Tonkin and Annam, many went to South China where they joined the Revolutionary Youth League. After a few months, they returned home to recruit new members among their families and friends. This pattern of recruitment had a significant effect on the distribution of the League’s membership. Measures aimed at limiting travel between Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina failed to prevent determined Vietnamese from moving between the three regions, so the League was active in all three. But the relative freedom of the press, movement, and association allowed in Cochinchina enabled the League to operate there more or less openly; but it also made it easy for the French Sûreté (colonial security and police service) to follow activists and to plant informers in their midst. In Tonkin and Annam, all political activities had to be clandestine, a situation that encouraged underground organizing.

The student activism of 1926–7 and the press debates it generated promoted the emergence of a new political party in Tonkin. Founded by Nguyễn Thái Học, it represented the coming of age of a new generation of students formed in the Franco-Annamite schools that had been established since 1919. The Vietnamese Nationalist Party (Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng – VNQDĐ) shared some features with the Revolutionary Youth League since both had been inspired by the Guomindang before it split with the Chinese Communist Party in 1927. Unlike the League, the VNQDĐ was limited to Tonkin. Competition between these two groups was fierce. The VNQDĐ particularly targeted workers and colonial troops whose ill-treatment by French officers and officials had continued since the Thái Nguyên uprising of 1917. In the post–World War I period, speculators had flocked to Indochina, whose economy had sustained less damage than the French economy. New plantations were opened (often by dispossessing Vietnamese cultivators), especially after rubber began to be cultivated on a large scale. A Michelin plantation was opened in the Southern Highlands in 1925. That year, the Cochinchinese Council estimated that the colony needed an annual influx of 25,000 new workers to sustain economic growth. By 1928, 80,000 workers were employed in plantations; more than half came from Tonkin and had often been recruited under false representations and made to sign onerous labor contracts for multiple years.Footnote 29 Coolie recruiters had become a symbol of the cruel exploitation of workers and peasants.

The growth of new political parties – a departure from Vietnamese political tradition – masked the emergence in the South of a new movement that combined religion and politics: the Cao Đài. Begun by a group of spirit mediums in Saigon in 1925, it soon attracted members by the hundreds and even thousands among colonial civil servants, wealthy landowners, and ordinary peasants. Its growth was aided by the relative freedom of religion in the colony and it even managed to spread into Cambodia. But the colonial authorities hid behind the fiction of Vietnamese sovereignty in Tonkin and Annam to prevent it from spreading into the two protectorates. Cao Đài ideology did not distinguish between secular and religious matters and many of the teachings emanating from its oratories had an anticolonial flavor. Thus, while the Revolutionary Youth League and the VNQDĐ dominated underground anticolonial activities in Tonkin and Annam, in Cochinchina the political scene was more diverse as well as more overt.

Meanwhile, several members of the Revolutionary Youth League were secretly laying the groundwork for the transformation of the League into a communist party as had been envisaged by Nguyến Ái Quốc. But after the collapse of the United Front in China, he had fled from Guangzhou in April 1927, leaving secondary leaders to seek guidance from Moscow. The Comintern was in its ultra-left phase in which class struggle trumped mere patriotism. The several draft platforms that League members submitted were severely criticized. Tracked down in Siam, Nguyễn Ái Quốc rejected their pleas to resume the leadership of the League.

The assassination of a League member in Saigon in December 1928 gave the French Sûreté the opportunity to arrest not only members of the League but also of other groups operating in the South. Altogether, sixty people were arrested for the “Crime de la rue Barbier.” Among those arrested, two-thirds hailed from Nguyễn Ái Qủc’s home province of Nghệ An, where the League was strongest. Three men were executed in May 1931 for their role in that political assassination.Footnote 30

Competition between the Revolutionary Youth League and the VNQDĐ also produced upheavals in Tonkin. Although Nguyễn Thái Học had contemplated a merger with the League, in the event, he rejected it on the grounds that the League’s program was too extreme. Thereafter the two groups vied for the allegiance of the same segments of the population.Footnote 31 In order to prove the VNQDĐ’s bona fide status to workers, in late 1928 one of its members, Nguyễn Vӑn Viên, proposed to assassinate a prominent coolie recruiter named Bazin. Although he was urged not to do so, Viên carried out the assassination of Bazin in February 1929. This provoked reprisals not only against the VNQDĐ but also against the northern branches of the Revolutionary Youth League at a time when its adherents were also being hunted by the Sûreté in Cochinchina.

Nguyễn Thái Hóc had envisaged a three-stage process for achieving independence through revolution, of which the last stage would be a general uprising combined with a general offensive. Faced with the coming destruction of the VNQDĐ, he decided to launch a general offensive in early 1930. But only the colonial garrison at Yên Bái and other scattered groups responded to his call to rise up. The colonial authorities responded by bombing the village of Cổ Am where Nguyễn Thái Học had taken refuge. On June 17, 1930, Học and twelve other leaders of the VNQDĐ went to the guillotine. Other leaders who had escaped arrest fled to South China. For the rest of the 1930s, the VNQDĐ ceased to be an active participant in anticolonial politics within the country.

On February 6, 1930, three days before Nguyến Thái Học launched his ill-fated general offensive, Nguyễn Ái Quốc finally emerged from his self-imposed exile to preside over the formation of the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) in Hong Kong. The disappearance from the scene of the VNQDĐ left the field clear for the new party to seize control of the emerging current of opposition to colonial rule in Annam. Only a few months later, protests against taxes erupted in Nghệ An and neighboring Hà Tĩnh. The ICP, implementing the ultra-left policies of the Comintern, targeted both the Vietnamese officials tasked with carrying out colonial policies and landowners, even patriotic ones. Frightened imperial ministers pleaded for the return from France of eighteen-year-old Emperor Bảo Đại to heal the social divisions engulfing Tonkin and Annam. In Cochinchina, reactions to colonial rule ranged from advocacy of Franco-Annamite collaboration to anticolonial activism both overt and covert. In the countryside, the Cao Đài movement, which was gathering followers by the tens of thousands, had been predicting the end of French rule and encouraging its members to stop paying taxes. The different types of social organizations prevailing in the South, their different programs of action and visions for the future, posed significant competition for the nascent ICP.

As the new decade began, the fate of Vietnam’s revolution seemed harder to predict than ever. Interest in revolution in Vietnam – especially among youth, students, intellectuals, and urban residents – was running high. But the surveillance and repression meted out by colonial police and security services meant that most of Vietnam’s revolutionary groups and activists faced an uncertain future at best. Indeed, in some respects, the colonial state seemed more powerful and more entrenched than before. It was also difficult to see how any of Vietnam’s several revolutionary parties or movements would be able to build broadbased popular support across all three of Vietnam’s regions, or to mobilize the rural farmers who made up the vast majority of the country’s population. For most Vietnamese, the era of revolutionary politics and upheaval still lay in the future, despite the many changes that the country had endured in the decades prior to 1930.