Introduction

In October 2017, members of the North Carolina Senate filed a state constitutional amendment that would decrease the terms for state supreme court justices to two years. All current justices would see their terms end in December 2018. The political situation in North Carolina that pitted the Republican-controlled state legislature against a newly elected Democratic governor and moderate supreme court, fueled the political tensions that led to this introduction. Similar events happened in Kansas in the previous years. This battle between the branches in Kansas raged until the legislature failed to pass a bill giving themselves the power to impeach any state supreme court justice for decisions they made (and a Democratic governor was elected in 2018).Footnote 1 In 2018, there were also significant threats of impeachment against some members of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court for a decision they made striking gerrymandered legislative maps.Footnote 2 Similarly, all members of the highest court in West Virginia were impeached for corruption due to excessive spending by two of the justices (the Chief Justice would go on to resign after being charged with related federal crimes).Footnote 3 Court curbing continues apace, with members of the South Carolina house of representatives introducing a plan in 2021 to increase their state high court from five to seven members. In South Carolina, members of the house appoint members of the state’s highest court. Additionally, the 2021 Pennsylvania legislature is seeking to change elections for their state supreme court from statewide to district contests.Footnote 4 All of these bills are designed, in one way or another, to reduce the power of the court and increase decisions by the court that are in line with the preferences of the state legislature.

The study of interactions between the legislative, executive, and judicial institutions in American state politics has long suffered from a lack of readily available data that allows for cross-institutional comparisons. The nature of the 50 states and their unique institutional constructions makes the collection of comparable data over time for each of the states a challenge, but also particularly ripe area for comparative study. New methods like web scraping or other automated data collection practices have improved the ability of scholars to collect information that allows for comparisons across states and within states across institutions (e.g., Bonica Reference Bonica2014; Bonica and Woodruff Reference Bonica and Woodruff2015; Hall and Windett Reference Hall and Windett2013). However, data that links the state legislatures and state courts to allow for the testing of theories on the separation of powers and policy making remains scarce. In this article, I introduce a new set of data on court-curbing introductions by state legislatures that will create avenues for additional research on state supreme courts, state legislatures, and state-level separation of powers struggles as it adds to the literature that considers these institutional interactions (e.g., Blackley Reference Blackley2019; Bosworth Reference Bosworth2017; Grey Reference Grey2019; Johnson Reference Johnson2014; Reference Johnson2015; Langer Reference Langer2002). Court-curbing legislation provides significant information about the relationship between the branches of government. It can also be used to capture legislative preferences for judicial independence and the balance of institutional power in the states. Examining this legislation across the states provides an indicator of the preferences of state legislatures about the state high court at a time when state legislators in many states are seeking to limit the power of courts (as well as governors and voters).Footnote 5

At the state level, this court-curbing legislation has garnered significant public interest as well as increasing media attention focusing on the often undemocratic or anti-judicial independence nature of the legislation. Yet, answers to why and when separation of powers struggles happen in the states and what is motivating these decisions are lacking in the literature (but see Blackley Reference Blackley2019; Johnson Reference Johnson2015; Leonard Reference Leonard2016). We do not know if these bills are simply a way for state legislators to position-take for their constituents (e.g., Clark Reference Clark2011) or if these are more serious or successful attempts at changing the decisions of the court or undermining democratic institutions. In this article, I introduce new data on legislative introductions of court-curbing bills over a nine-year period from 2008 to 2016, which can be used to address these relevant research questions among others. Covering nine years and all 50 states, this data expands on previous research by providing state and bill-level data with information about the policies and sponsors of each piece of legislation. In doing so I provide an explanation of how the data was collected, descriptive statistics, a theory testing initial questions on court curbing, and possibilities for use in future research.

Separation of Powers in the States

The independence of the judiciary is more tenuous in the states than at the federal level. Unlike the US Supreme Court, very few state supreme court justices serve for life, as most face either the voters or the other branches of government in seeking to maintain their position on the bench. Beyond life tenure, other institutional rules highlight the difference between the highly independent US Supreme Court and state high courts such as constitutional amendment processes that make judicial review decisions easier to reverse than at the federal level (see Langer Reference Langer2002). State high court justices often must seek reelection to the court, sometimes through contestable partisan or nonpartisan elections, or for others through retention elections. These retention mechanisms necessarily change how the justices on state high courts make decisions, as they consider the preferences of the public along with their own preferences (see e.g., Brace and Boyea Reference Brace and Boyea2008; Canes-Wrone, Clark, and Kelly Reference Canes-Wrone, Clark and Kelly2014). In addition, like the US Supreme Court, some state high courts have fully discretionary dockets, where they can choose which cases to hear and therefore choose when and how to make policy. In other states, the high court may have mandatory jurisdiction for all cases or in areas such as the death penalty, which can crowd their dockets leaving them with large caseloads, or limited power to make decisions on some cases. These institutional variations change how justices on these courts make decisions, the court’s ability to affect policy outcomes, as well as the ways they are constrained by the other branches of government (e.g., Langer Reference Langer2002).

Ultimately, court curbing is about the interactions between the court and legislature and each institution’s ability to affect policy outcomes. However, our understanding of state court interactions with state legislatures and executives is still fairly limited, with a few exceptions. Examining responses to court decisions directly, Bosworth (Reference Bosworth2017) finds clear evidence of court-legislative communication in the states. Langer (Reference Langer2002; Reference Langer2003) demonstrates how this interaction works within the separation of powers game, where state high courts vote in line with the preferences of the other branches of government when they fear retaliatory punishment as a result of their decisions. Similarly, Johnson (Reference Johnson2014; Reference Johnson2015) shows that the court also fears executive retaliation and makes decisions in favor of the executive branch when necessary. When making decisions, all branches of government in the states are aware of the actions and potential reactions of the other branches. Court curbing must be considered within this institutional context and should be examined to tell a more complete story of this interaction.

Court Curbing at the Federal and State Level

Relatively little is known about court-curbing introductions in the states. It is assumed that much of this legislation is introduced in response to specific politicized court decisions or changes in social issues via court decisions such as same-sex marriage (see e.g., Klarman Reference Klarman2013). Conventional wisdom also suggests this legislation is designed to threaten via its introduction and may simply be a way for state legislators to position-take in the Mayhew (Reference Mayhew1974) sense. But, in the examples above, only the threatened impeachment of the Pennsylvania justices stopped at the introduction stage. Impeachment trials were held for the four sitting members of the West Virginia Supreme Court. The Kansas legislature passed and the governor signed legislation limiting the court’s selection power for chief justices. A year later, the governor signed a bill that would cut all funding for the courts if the selection bill was ruled unconstitutional. (The court did rule it unconstitutional.) In 2017, overriding the governor’s veto, the North Carolina legislature imposed partisan elections for their state courts.Footnote 6 There is reason to believe, as previous research demonstrates, that most court-curbing bills do not become law, but no systematic study has examined which do and why (Leonard Reference Leonard2016).

Court-curbing legislation is a type of signaling from the legislature, both to the public and to the court (Clark Reference Clark2011). This legislation should provide significant information about how state legislators view their corresponding state high courts and can serve as an indicator of legislative preferences. Much has been written on Congress’ use of court-curbing legislation. Clark (Reference Clark2009; Reference Clark2011) argues that for the member of Congress the introduction of this type of legislation is used to position-take as described by Mayhew (Reference Mayhew1974). Nagle (Reference Nagel1965) examined federal court curbing and finds that ideological difference, divided government, interest groups, a current crisis, and public opinion all affected the use of this legislative strategy. Initial work suggests that court curbing at the state level is driven by republican partisanship and institutional ideological disagreement, rather than the institutional structure of the court (Blackley Reference Blackley2019; Hack Reference Hack2021; Leonard Reference Leonard2016).

Rosenberg (Reference Rosenberg1992) more definitively ties federal court curbing to judicial independence, arguing that if the Supreme Court were wholly independent it would make decisions without regard to the preferences of Congress or the executive (371). He finds, however, that in periods of intense court curbing, the Supreme Court acquiesced to Congress. Clark (Reference Clark2011) demonstrates that the Supreme Court is responsive to this legislation, limiting its use of judicial review as the number of court-curbing introductions increases. Thus, court curbing can be used as a check on the Supreme Court, as it reads the increased number of introductions as a sign of current public opinion toward the Court (Clark Reference Clark2009; Reference Clark2011). Examining the justices individually, scholars find that the justices respond differently to court curbing based on their position within the court. The chief justice and the most moderate swing justice are the most responsive to court-curbing introductions, altering their behavior to be less likely to invalidate legislation than the others (Mark and Zilis Reference Mark and Zilis2018b).

Both institutional and individual motivations have been assessed to determine which legislators court-curb. On the individual level, Mark and Zilis (Reference Mark and Zilis2018a) find that lawmakers on the judiciary committee, those who are in the majority party, and those who are furthest ideologically from the court are more likely than their colleagues to introduce court-curbing legislation. Looking to the lower federal courts, Moyer and Key (Reference Moyer and Key2018) find that court-curbing legislation that focuses on splitting the ninth circuit is driven by ideology. More conservative members introduce more legislation to split the court. In the states, Blackley (Reference Blackley2019) finds that individual members of state legislatures that introduce court-curbing bills do so when they are ideologically distant from the court, but also electorally secure.

New Data on Court-Curbing Legislation

To examine when and how state legislators use court-curbing threats and the nature of these threats, I collected an original set of data covering the introduction of court-curbing legislation in all 50 states from 2008 to 2016. I used the Gavel-to-Gavel database, a project from the National Center for State Courts that tracks all court-related legislation introduced in the states. This provided a list of 8,559 court-related bills from all 50 states from 2008 to 2016 (Gavel to Gavel Blog Database).Footnote 7 All legislation in the data came from this database. Not all legislation is designed to curb the court, so for each piece of legislation, we used the summary provided by the database to separate out those bills that would not curb the court’s power. For example, some bills name courthouses, others provide the budget for the court, and some bills create new courts like drug or veterans’ courts. A bill signed into law in Arizona in 2012 allowed for courts to charge convenience fees when collecting fees via credit card charges. Another noncurbing bill introduced in South Carolina in 2015 would have changed the state constitution to allow judges in the state to participate (only) in the South Carolina lottery. These are routine pieces of legislation about the courts, that might change the system or structure, but do not limit the power of the courts or judges in any way and are not considered court curbing. Approximately 85% of court-related legislation in the states over this period was coded as not court curbing.

To determine which legislation was designed to curb a court, I used a definition where a bill was determined to be curbing if it somehow limited the power of the court or justices or changed how they made decisions in certain policy areas (see also Leonard Reference Leonard2016).Footnote 8 Following Clark (Reference Clark2011) and Rosenberg (Reference Rosenberg1992), the definition the coders followed was that a court-curbing bill is a statute or constitutional amendment “introduced … having as its purpose or effect, either explicit or implicit, Court reversal of a decision or line of decisions, or Court abstention from future decision of a given kind, or alternation in the structure of functioning of the Court to produce a particular substantive outcome” (Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg1992, 377). In coding, we took a broad definition of the bills, including not limiting them to just those that would hurt the power of the state supreme court but lower courts as well. This resulted in 1,253 total curbing bills over the nine-year period or 15% of the total court-related bills. These include an average of 139 bills per year with a high of 221 in 2012 and a low of 78 in 2008. When the same bill was introduced in the lower and upper chambers in the same year, the bill was only counted once.Footnote 9 In addition to the bill-level information, the data is separately structured in a state-year format (Leonard Reference Leonard2022).

Notably, court curbing can encompass several actions that range in severity and can even include opposite actions—such as expanding or reducing the number of justices on the court. Bills that would change the methods of selection were included, even when some would force justices to face elections and others would give power to the governor to appoint justices. The most common example of a court-curbing bill was those that would prohibit courts from citing foreign law. This issue garnered some attention after a series of death penalty decisions by the US Supreme Court referenced international law. Other examples of court-curbing legislation increased or set qualifications for judges. Some court-curbing bills would have a more severe effect, with at least three bills introduced that would remove the judicial review power of the court, and others would allow for a legislative override of court decisions.

For each piece of legislation, the data includes the state, year, and bill number. There is a short description of the bill and a categorization for the last action taken on the legislation. Both of these categorizations were provided by the Gavel-to-Gavel database, but then hand-coded and expanded to further separate and categorize. Each bill was sorted into twelve separate categories for the type of legislation. These include, for example, jurisdiction, selection, removal, qualifications, decision making, among others. Each bill was also coded to determine which court or courts were affected by the legislation with a categorical variable ranging from 1 to 8. For example, some bills address just the state supreme court, others trial courts, or only appellate courts. Finally, the last action of the legislation—if it was just introduced or died in committee, or signed by the governor—is indicated with a categorical variable ranging from 1 to 7.Footnote 10

With the list of bills that would be considered court curbing we searched for each bill in the relevant legislative session in the state. For more than 80% of the bills, we were able to determine sponsorship information for the bill. The name of the sponsors, if there were cosponsors, the number of cosponsors, and the partisan information about the sponsors were all collected when available. For the sponsor, we also determined if they were a member of the judiciary committee or a member of the chamber leadership when that information was available.Footnote 11 Finally, for the sponsors, we added their ideology score from the DIME data (Database on Ideology, Money in Politics, and Elections, Bonica Reference Bonica2014). When there were multiple sponsors listed, the sponsor ideology is the median ideology of the sponsors listed. Sponsorship information was not available for all of the bills in the dataset. This is due to differences across states in reporting and archiving legislation proposed in previous sessions. Most of the bills where sponsor information was not available were from the early years of the data, so the missing sponsor information is not randomly distributed across the states and years but is concentrated based on the bill information a state makes publicly available.

Previous examinations of court curbing in the states looked at this legislation either as a count of the number of bills introduced in a state year (Hack Reference Hack2021; Leonard Reference Leonard2016) or if an individual legislator introduced (or not) a court-curbing bill (Blackley Reference Blackley2019). The data introduced here moves beyond this initial work by including several details about each piece of court-curbing legislation that will allow for state-year or bill-level studies. The expanded nine-year period allows for researchers to see changes over time and the effects of national forces on these state legislative decisions, such as the response to national changes on same-sex marriage, or the upholding of the Affordable Care Act.Footnote 12 This extended period allows for researchers to address questions with measures that include but are not limited to spikes in the number of bills related to the Republican takeover after the 2010 elections and the response to the 2009 Iowa Supreme Court decision legalizing same-sex marriage (see e.g., Leonard Reference Leonard2016).

Descriptive Statistics

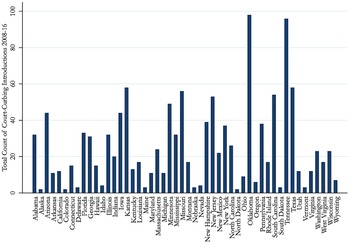

Figure 1 displays the use of court-curbing legislation by state. All states introduced at least some court-curbing legislation, but a few states stand out. The political situations in Iowa and Kansas have been previously mentioned and explain their high counts. Two other states that stand out are Tennessee and Oklahoma. Over the course of the nine-year period, Tennessee had 96 court-curbing introductions, and Oklahoma 98. Most of the introductions in both states were changes to the method of selection and retention. In Tennessee, this was driven by what was known as the “Tennessee Plan”—a battle between the courts and the legislature over the constitutionality of the method of selection in the state. After three court-curbing bills were introduced in Tennessee in 2008, from 2009 through 2013 an average of 16.2 court-curbing bills were introduced in Tennessee each year. In 2014, the voters of Tennessee ratified a constitutional amendment that gave the governor and state legislature a larger role in the method of selection.Footnote 13 Following those changes, the legislature has averaged four court-curbing introductions in a year. Many of the introductions in Oklahoma were also bills that would tinker with the details of the merit selection plan.

Figure 1. Court-curbing bills per state.

In Table 1, I include a series of descriptive statistics and coding of many of the legislative-level indicators in the data. This table also provides some interesting substantive information. Notably, 71% of court-curbing legislation during this time was introduced by Republican legislators. In examining the ideology of the sponsors, the mean ideology of all sponsors is 0.438 (CF Score), which is on a −2 to 2 scale. Therefore, on average, the sponsors are right of center. This tracks with previous work that shows Republicans are more likely to sponsor court-curbing legislation (see e.g., Leonard Reference Leonard2016). About half (45%) of the bills introduced had at least one cosponsor, 17% included cosponsors from both parties, with the average number of cosponsors being 3.2. In looking at the positions of the members who introduce court-curbing bills, about 39% of the sponsors sat on the judiciary committee or its equivalent in their state, and just 14% were members of the chamber leadership at the time of introduction.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics on court curbing by state legislatures

The most likely profile of sponsor of a court-curbing bill is a conservative or Republican member who does not sit on the judiciary committee and is not a member of leadership. More detailed research would be needed to tell why exactly this is the case, but the Republican takeover of state legislatures in 2010 is one major explanation (in part the high sponsorship percentage of Republican lawmakers was simply that there were more Republican legislators during this time). More evidence of this simplistic explanation shows that after Democratic gains in the 2012 state legislative elections, there is a decrease in the introduction of this legislation. During this time there is also a perception that courts were more liberal than their legislative counterparts (see Bonica and Woodruff Reference Bonica and Woodruff2015 for a comparison of the ideology of state institutions). This is likely because of higher profile decisions, especially in morality policy cases such as LGBTQ rights, abortion, and the death penalty. As such, Republican state legislators have used court-curbing introductions to respond to these decisions and communicate to their constituents that they were doing so. While initial data used in previous work captures some of the response to these decisions, including the years after the Windsor and Obergefell decisions help capture this response even more.

Figure 2 displays the court-curbing introductions by year. There is some variance in the number of introductions during the time period. The number of bills introduced jumped in 2009 and stayed high through 2012. The initial surge here is likely a response to the Varnum v. Brien (2009) Iowa Supreme Court decision legalizing same-sex marriage in the state. However, the numbers stayed high over the next few years, likely because of the significant Republican takeover of state legislatures in the 2010 elections.

Figure 2. Court-curbing bills by year.

There has long been interest in which courts face the most court-curbing legislation, especially as it relates to the methods of selection and retention of the justices. This follows the hypothesis that more independent courts should face more curbing legislation—but to date, none of the systematic examinations of court curbing has found significant differences in introductions based on the methods of selection or retention (Blackley Reference Blackley2019; Hack Reference Hack2021; Leonard Reference Leonard2016) Figure 3 displays the number of introductions by the methods of selection. As methods of selection partisan elections are used in 8 (16%) states, nonpartisan in 13 (26%), merit selection in 16 (32%) states, appointments with no elections but with reappointment are used in 9 (18%) of states.Footnote 14 The remaining four states (8%) have life tenure for their appointed justices. If there were one type of method of selection that was driving the decision to introduce court-curbing legislation, we would expect the percentages in this graph to be far different than the percentages of states that use that method of selection. Figure 3 suggests that this is not the case. States with retention elections get slightly more, and states with nonpartisan selection, slightly less court-curbing bills than might be expected.

Figure 3. Introductions by methods of selection.

In Figure 4, I display where these court-curbing bills progress in the legislative process. About 78% of this legislation does not make it past being sent to committee. In other words, the large majority of court-curbing legislation in the states is merely introduced, giving credence to the assumption that the legislation may simply be for position-taking purposes. Though some of the legislation does move through the process a bit more, only 4.3% ends up on the desk of the governor, where they veto 0.6% of this legislation.

Figure 4. Progress of court-curbing introductions.

Explaining the Progress of Court-Curbing Introductions

Conventional wisdom about court-curbing introductions is that members who sponsor this legislation do so to “position-take” or communicate with their constituents about their preferences toward the court. The goal, in other words, is not in the passage of the bill but is in this communication. Previous work on court curbing in the states makes this assumption, as it examines bills as they are introduced and not when they become law (e.g., Blackley Reference Blackley2019; Hack Reference Hack2021; Leonard Reference Leonard2016). This conventional wisdom is taken from studies of the US Supreme Court and curbing bills introduced by members of Congress (e.g., Clark Reference Clark2009). I examine this assumption by asking which factors explain the movement of these bills through the legislative process. As we can see from the descriptive statistics above, very few of these bills pass. But, if there are factors that consistently explain the forward movement through the legislative process, that may indicate that some, but not all, of this legislation is to position-take or denote preferences.

I examine the progress of legislation and expect that certain characteristics of members will help move this legislation further through the process. Members of the judiciary committee, members of leadership, and members of the majority party should be more successful at moving their legislation through the process as the rules of a legislature benefit these members over those not in the majority or leadership positions. I also control for the ideology of the sponsor (or median ideology if there are multiple sponsors) as well as the ideological distance between the sponsor and the court. The institution itself may also affect the process of legislation. Legislatures with higher levels of professionalization should also move through the process of lawmaking easier than in legislatures with less professionalism.

In terms of characteristics of the bills themselves, certain bills should move through the legislative process more easily. Those bills that have more cosponsors and cosponsors from both parties should be more successful based on their support and support from both parties. The content of the legislation is likely to affect its movement through the legislative process. The bills included here are all court-curbing and in some way designed to limit the power of the court. I have no theoretical reason to expect that a bill on foreign law or the method of retention may move further through the process. However, I want to control in some manner for the content of the legislation. For example, threats to remove the power of judicial review are far more likely to be idle threats than those bills that would require a limited jurisdiction court judge to have a law degree. To address this, I use the Bartels and Johnston (Reference Bartels and Johnston2020) categorization of this type of legislation as broad or narrow court curbing. Narrowly targeted court curbing is designed to affect a small number of decisions in a narrow way and is not intended to fundamentally change the power of the court. On the other hand, broadly targeted bills would fundamentally change the power of the court in an enduring way (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2020, 53). I except narrowly targeted bills will be more likely to move through the process as narrow, limited changes are more likely to get legislative support than broad, significant changes to the court.

Model and Results

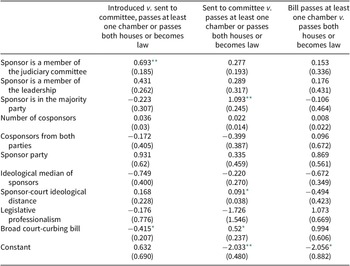

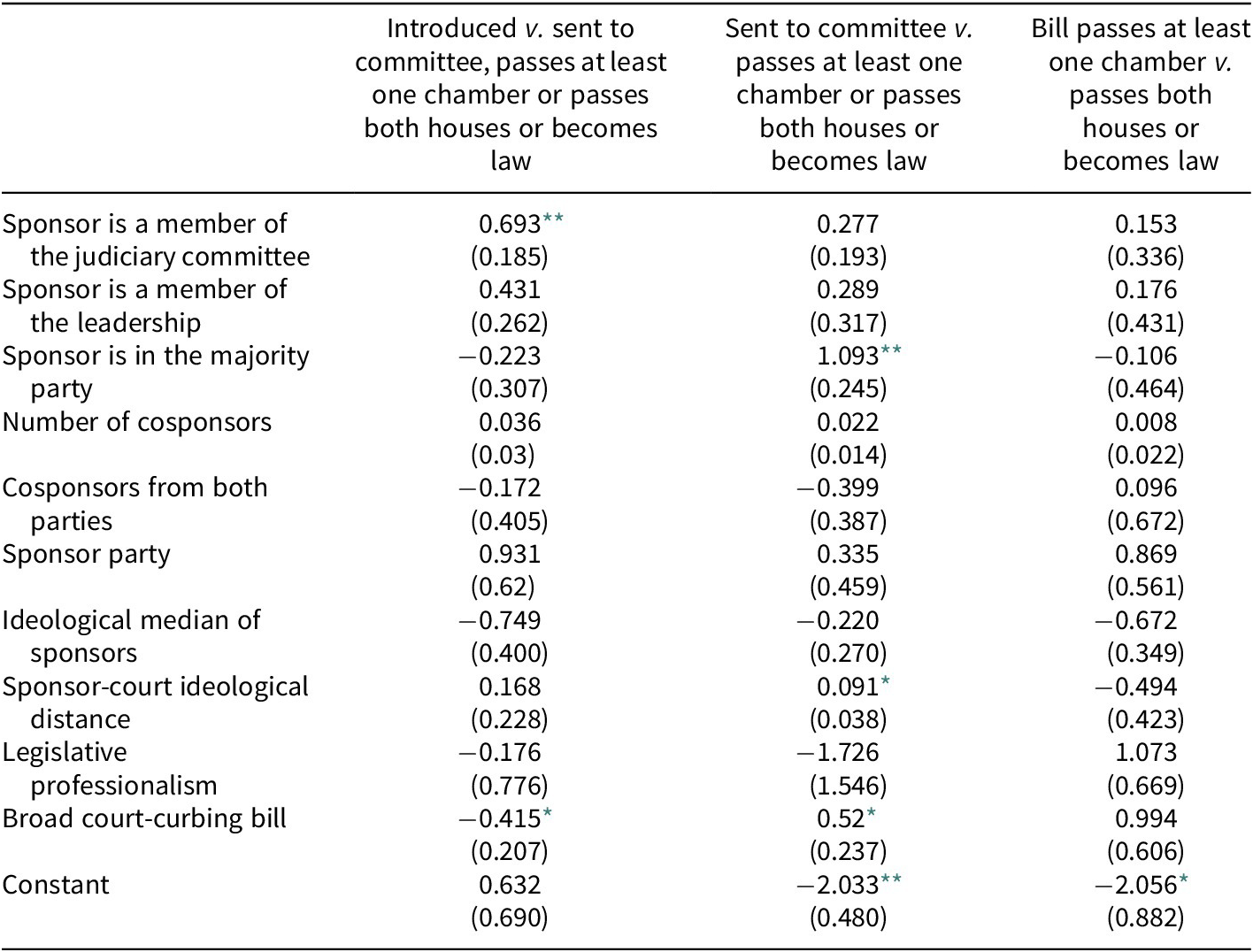

Scholars who study court curbing have examined this legislation from the perspective of the legislature and the courts. They have argued that court institutional structures and individual legislative characteristics have affected the introduction of this legislation (Blackley Reference Blackley2019; Hack Reference Hack2021; Leonard Reference Leonard2016). Here, I include an examination of this data, asking what explains which court-curbing bills move past the introductory stage of the legislative process. The assumption, based on research at the federal level, is that court curbing is position taking and designed to be a link to constituents rather than become law. Figure 4 demonstrates that most of this legislation is left at the introductory stages of the process, but what about the bills that progress through the process. Is there something about that legislation that is different? In Table 2, I display the results of a sequential logistic regression that compares what predicts that court-curbing legislation will be simply introduced, is sent to committee, will pass at least one chamber of the legislature, or will pass both houses or become law.Footnote 15

Table 2. Sequential logit: Progress of court-curbing legislation

Note. Standard errors clustered by state, n = 869.

** p < 0.00.

* p < 0.05.

The results in Table 2 support some of these propositions—that some bills are more likely to move through the legislative process. These bills may not be designed just to position-take, but the legislator may be seeking passage. Members of the judiciary committee and majority party have more success with their court-curbing legislation. The results in the table correspond to the log-odds of passing each transition. Sponsors on the judiciary committee are more likely to see their legislation move past the introductory stage of the process. The probability of moving into the later stages increases by 23.9% for members of the judiciary committee. Additionally, those broad court-curbing bills are less likely to make it out of the introductory stage, being 2.2% less likely to move forward. Members of the majority party are 12.9% more likely to see their bills sent to committee, as opposed to moving past the committee stage. Interestingly, nothing predicts the bills that will make it to the late stages of the legislative process, perhaps owing to the conventional wisdom that this legislation is not designed to pass, but to communicate.

If we treat each stage of the process as ordinal and not sequential, the results are similar. A full table of results from the ordinal logistic regression model is included in the Supplementary Material. Looking at the results graphically, Figure 5 displays the changes in the predicted probability of each category for members of the judiciary committee. This graph demonstrates that when the sponsor is a member of the judiciary committee, they are significantly less likely to have the bill end at the introductory stage as they are significantly more likely to have their bill be sent to committee. Additionally, particularly for members of the leadership, the probability that the bill will pass at least one chamber increases significantly. But, again, neither indicator affects the likelihood that a bill passes both chambers or becomes law. In simpler terms, court-curbing legislation is similar to all other types of legislation in state legislatures. That which is introduced by the members of the relevant committee or the majority party has a significant advantage in moving through the legislative process.

Figure 5. Change in predicted probability of each outcome: Member of judiciary committee (ordinal logistic regression).

Discussion and Conclusion

In 2013, members of the Senate in Washington introduced a bill that would reduce the number of justices on the state supreme court from nine to five. The five justices who would continue to serve would be determined by drawing straws.Footnote 16 In 2016, the lower house in Wyoming introduced legislation that would allow the legislature to override decisions of the Wyoming Supreme Court by two-thirds vote.Footnote 17 In Texas, any judge that recognized same-sex marriage would have been forced to forfeit their salary, if legislation introduced in 2015 had passed.Footnote 18 All of these provide examples of how the state legislators use bill introductions to communicate to the state courts and the public. Some legislation would result in dramatic institutional changes, others would simply punish individual judges for decisions out of step with the ideological preferences of the legislature. In either case, this legislation is providing significant information about the relationship between the branches of government in the American states.

Summarizing the results, on an individual bill level, that legislation moves further through the process when it is introduced by a member of the judiciary committee, or leadership, or the majority party. But there are no clear indicators that predict which pieces of court-curbing legislation become law. In other words, court-curbing legislation might be more concerning to the court when it is introduced by a member of the majority party or a member of the judiciary committee, as those bills have a greater chance of moving further through the legislative process. But, overall, very few court-curbing bills even pass one house of the legislature with even fewer becoming law. This result may be unsurprising, but it provides additional information on court-curbing legislation and how courts should interpret these signals from their legislative counterparts.

Beyond the example presented here, this data could be used in many different examinations of state legislatures or state courts. Court-curbing bills have long been understood to be position-taking opportunities. This data will allow researchers to see if this legislation is introduced by members who face reelection challenges (e.g., Blackley Reference Blackley2019) or if there is a relationship between court curbing and political ambition. Trends in court-curbing legislation would lend themselves well to policy diffusion studies, knowing when and how attacks on state high courts diffuse could inform scholars about both institutions. Certainly, with trends in nationalization (e.g., Hopkins Reference Hopkins2018), how this legislation is shared across states could be particularly informative. Indeed, because court-curbing legislation is often in response to an action by a court, this data could be used to see when state legislators react to national forces (in the case of same-sex marriage Supreme Court decisions) or state forces (for example, decisions on education financing by the state supreme court) (see Bosworth Reference Bosworth2017).

Researchers wanting to examine the effects of this legislation on the courts could use the counts of the number of court-curbing bills to determine how these affect certain decisions by the state high court—say in judicial review cases, or cases in which the government is a party. Or, they could select a subgroup of the data based on state, or topic, or years. The data presented here could also be parsed by the severity of the curbing involved and used to determine if and when the court reacts to this legislation. For example, broad court curbing like impeachment threats, or court-packing may be far more effective at changing the decisions of the courts, as opposed to narrowly tailored legislation that might increase the qualifications for lower court judges, or the requirement that judges disclose financial information. Additionally, given that some of these bills are bipartisan, the effects of these indicators on court responsiveness could be of significant interest to scholars of the separation of powers.

The data can be combined with other readily available data on state legislatures and state high courts such as the Shor–McCarty individual or aggregate state legislative ideology scores (Shor and McCarty Reference Shor and McCarty2011) as well as the Bonica and Woodruff (Reference Bonica and Woodruff2015) and Windett, Harden, and Matthew (Reference Windett, Harden and Matthew2015) measures of state supreme court ideology. Additionally, any number of institutional or policy variables in the Correlates of State Policy data (Jordan and Grossmann Reference Jordan and Grossmann2020) could be used to further expand the types of research questions that could be addressed here. The data can be used to compare with court outcomes in the Hall and Windett (Reference Hall and Windett2013) data on state supreme court decisions.

In addition to court curbing being a measure of legislative preferences toward the court, it is also an indicator of legislative attempts to change rules to affect policy outcomes. There has been increasing use of these types of actions by some state legislatures to ensure policy outcomes are closer to their preferences. In North Carolina and Wisconsin during the lame-duck sessions of 2016 and 2018, respectively, Republican-controlled state legislatures rolled back the power of the governor as each state had an incoming Democratic governor, replacing a Republican.Footnote 19 While these laws limited power in other ways, the direct goal was clear: to weaken the governor and try to ensure policy outcomes closer to the legislature’s preferences. Court-curbing legislation should be seen as part of a larger effort and increasing trend—along with gerrymandering, voter suppression, and removing gubernatorial powers—to limit policy control and centralize power by state legislators. Harnessing this information can aid in increasing scholarship on this separation of powers game and increasing our understanding of policy making and democracy in the American states.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/spq.2022.8.

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials are available on SPPQ Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.15139/S3/MJMNUG (Leonard Reference Leonard2022).

Funding Statement

This research was supported by funding from the National Science Foundation, award number 1654934.

Conflict of Interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Biography

Meghan E. Leonard is as Associate Professor in the Department of Politics and Government at Illinois State University. She studies state supreme court decision-making.