Introduction

The world has seen a significant reduction in the burden of new infections of HIV since the beginning of the 21st century (UNAIDS, 2015a). The virus has affected more than 76 million people, with almost 40 million people living with HIV across the globe as of 2016 (UNAIDS, 2017). Although the new infection rate has reduced by almost 40%, it remains a global health challenge with at least 35 million people still living with the virus in spite of this remarkable progress (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Wright, Safrit and Rudy2011; UNAIDS, 2014). Low- and middle-income countries continue to bear the largest burden of HIV cases and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) accounts for almost two-thirds of people living with HIV (UNAIDS, 2017). The virus is a public health concern that needs to be tackled, and goal three of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) seeks to end AIDS and other diseases including tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis and water-borne diseases by 2030 (UNAIDS, 2018).

The virus has been destructive in SSA due to the existence of different strains of HIV, economic marginalization, poverty and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), coupled with opportunistic infections (Amuche et al., Reference Amuche, Emmanuel and Innocent2017). The main mode of transmission is by sexual intercourse, and it occurs across all categories of the population, including children, young people, adults, women and men. However, there are new occurrences of HIV infections among men in the general population as well as female sex workers, people who inject drugs and men who have sex with men (National AIDS Control Council, 2014; UNAIDS, 2015b).

The reduced rate of new infections in many SSA countries is as a result of behavioural changes such as increased condom use, fewer sexual partners and delayed sexual debut among young adults (Ghys et al., Reference Ghys, Gouws, Lyerla, Garcia-Calleja and Barrerre2010). It is estimated that less than half of young adults worldwide have an error-free knowledge of HIV. Undoubtedly, there has been an improvement in knowledge and awareness of HIV transmission (Ghys et al., Reference Ghys, Gouws, Lyerla, Garcia-Calleja and Barrerre2010; UNAIDS, 2010). The virus has impacted negatively on the economies in the world, especially in SSA (World Health Organization [WHO], 2015). Although HIV-related deaths in SSA have declined and new infection rates have stabilized, only 45% of people in SSA know their HIV status and men are more likely to be unaware of their status than women (UNAIDS, 2014).

In SSA, males are less likely to access health services compared with females, as evidence suggests various challenges to the uptake of HIV testing. Individual factors such as gender norms, fear of results, stigma and discrimination, low perception of risk and fear of disclosure, as well as provider attitude and confidentiality, inadequate supplies and equipment, have been documented to hinder access to testing services (Sylvester et al., Reference Sylvester, Braitstein, Michael, Ochieng, Daniel and John2010; Ziraba et al., Reference Ziraba, Madise, Kimani, Oti, Mgomella and Matilu2011; Shattuck et al., Reference Shattuck, Burke, Ramirez, Succop, Costenbader and Attafuah2013; Treves-Kagan et al., Reference Treves-Kagan, El Ayadi, Pettifor, MacPhail, Twine and Maman2017; Rhead et al., Reference Rhead, Skovdal, Takaruza, Maswera, Nyamukapa and Gregson2019). People living with undiagnosed HIV, especially men, contribute significantly to the transmission of the virus (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Holtgrave and Maulsby2012).

There is still no effective vaccine for HIV. However, measures have been taken to scale up HIV preventive measures and voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) among men in SSA. Despite this, testing coverage remains low among men in many SSA countries (Kharsany & Karim, Reference Kharsany and Karim2016; Statistics South Africa, 2017). However, it has seen some improvement based on community and home-based HIV counselling and testing models (DiCarlo et al., Reference DiCarlo, Mantell, Remien, Zerbe, Morris and Pitt2014; Hensen et al., Reference Hensen, Taoka, Lewis, Weiss and Hargreaves2014, Reference Hensen, Lewis, Schaap, Tembo, Mutale, Weiss, Hargreaves and Ayles2015). HIV testing, as an intervention in itself, underlies the effectiveness of most other prevention approaches (Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Carballo-Diéguez, Coates, Goodreau, McGowan and Sanders2012).

Historically, there is only limited self-testing rates available for men with HIV, and SSA is no exception, with the proportion of the male population receiving an HIV test and obtaining a test result in the last 1 year spanning from 1.6% in Niger to 41.7% in Eritrea (Instituto Nacional de Saude et al., Reference Instituto Nacional, Instituto Nacional and Macro2010). A focus on knowledge, prevention and treatment among men should greatly impact on mortality, new infections and the economic impact of HIV in SSA (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Beyrer, Birungi and Dybul2012). Mozambique has been severely impacted by HIV/AIDS (Gona et al., Reference Gona, Gona, Ballout, Rao, Kimokoti, Mapoma and Mokdad2020). It increased the number of adults undergoing HIV testing compared with baseline testing rate in 2003, but by 2009 only a minority of men (17.2%) reported ever receiving an HIV test and being aware of their status (WHO et al., 2010). Mozambique is ranked amongst the highest in terms of HIV prevalence (Instituto Nacional de Saude et al., Reference Instituto Nacional, Instituto Nacional and Macro2010). It is among the ten countries in the world with the highest HIV burden and accounts for 8% of all new HIV infections in SSA, with HIV prevalence of 13.2% in adults aged 15–49 in 2009 (Mocumbi et al., Reference Mocumbi, Gafos, Munguambe, Goodall and McCormack2017).

Kenya is recognized as a priority in SSA and is one of its hardest hit countries, with almost 2 million people living with the virus (Kimanga et al., Reference Kimanga, Ogola, Umuro, Ng’ang’a, Kimondo and Murithi2014; Kharsany & Karim, Reference Kharsany and Karim2016; UNAIDS, 2017). Nonetheless, about 84% of infected persons in Kenya were unaware of their HIV status in 2013, resulting in a call for universal access to HIV testing (Ng’ang’a et al., Reference Ng’ang’a, Waruiru, Ngare, Ssempijja, Gachuki and Njoroge2014). HIV testing has been part of many national household surveys, including the Kenya Demographic and Health Surveys (2003 and 2008–09) and the Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey (KAIS) in 2007. These surveys estimated that HIV prevalence in adults ranged from 6.3% to 7.4% (Kimanga et al., Reference Kimanga, Ogola, Umuro, Ng’ang’a, Kimondo and Murithi2014). The HIV incidence rate is currently 7%, with a number of new infections occurring almost always in specific key populations, including female sex workers, men who have sex with men and people who inject drugs (Kharsany & Karim, Reference Kharsany and Karim2016; Bhattacharjee, Reference Bhattacharjee, Rego, Musyoki, Becker, Pickles and Isac2019).

The UNAIDS 95-95-95 by 2030 targets are for at least 95% of the world population being made aware of their HIV status and an ‘AIDS-free generation’ (UNAIDS, 2014). This meant HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment campaigns focusing on other sub-population group, including women and children (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Beyrer, Birungi and Dybul2012). This means that fewer measures have directly targeted HIV prevention, testing and care at men in SSA (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Beyrer, Birungi and Dybul2012; Gunn et al., Reference Gunn, Asaolu, Center, Gibson, Wightman, Ezeanolue and Ehiri2016). While some studies on HIV among men in Kenya and Mozambique largely focused on their role in the Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT) services or oral self-testing, and less on men as HIV testing clients (Okal et al., Reference Okal, Lango, Matheka, Obare, Ngunu-Gituathi, Mugambi and Sarna2020) and men who have sex with men (Horth et al., Reference Horth, Cummings, Young, Mirjahangir, Sathane and Nala2015), no previous study has assessed the comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge and testing of men in Kenya and Mozambique. The purpose of this study was therefore to assess the association between comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge and HIV testing among men in Kenya and Mozambique. It was hypothesized that there would be a positive association between comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge and the probability of being tested for HIV.

Methods

Study design and data source

The study utilized data from the men’s re-code file of the Demographic and Health Surveys of Mozambique in 2015 and Kenya in 2014. The DHS is a nationally representative survey that is conducted in over 85 low- and middle-income countries globally. It focuses on essential markers such as breastfeeding, fertility, family planning, immunization, HIV/AIDS, child health and nutrition (Corsi et al., Reference Corsi, Neuman, Finlay and Subramanian2012). The survey employs a two-stage stratified sampling technique, which makes the data nationally representative. The study by Aliaga and Ruilin (Reference Aliaga and Ruilin2006) provides details of the sampling process. A total of 3395 men in Mozambique and 8433 men in Kenya who had complete information on all the variables of interest were included in the study. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology’ (STROBE) statement was followed closely when writing the manuscript (Von Elm et al., Reference Von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke2007). The dataset is freely available for download at: https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm

Definition of variables

Outcome variable

The outcome variable was ‘HIV/AIDS testing’, derived from survey responses to the question ‘Have you ever tested for HIV?’ Responses were ‘Yes’ and ‘No’, and were coded as No=0 and Yes=1 (Seidu, Reference Seidu2020).

Independent variables

The main independent variable was ‘comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge, defined as: i) knowing that consistent use of condoms during sexual intercourse and having just one uninfected faithful partner can reduce the chance of getting an HIV infection; ii) knowing that a healthy-looking person can have the AIDS virus; and iii) rejecting the two most common local misconceptions about AIDS transmission or prevention (i.e. it is transmitted via mosquito bites or witchcraft/supernatural means). Comprehensive HIV knowledge was dichotomously coded Yes = 1 if a respondent demonstrated correct knowledge of all the preceding elements and No = 0 if a respondent did not demonstrate correct knowledge of all the elements (Ochako et al., Reference Ochako, Ulwodi, Njagi, Kimetu and Onyango2011; Agegnehu et al., Reference Agegnehu, Geremew, Sisay, Muchie, Engida, Gudayu and Liyew2020; Darteh, Reference Darteh2020).

Control variables

Eleven control variables were considered, broadly grouped into individual and contextual variables. The individual variables included age, employment status, marital status, educational level, frequency of reading newspapers/magazines, frequency of listening to radio, frequency of watching television, condom use and number of sexual partners. The contextual factors included wealth quintile and urban/rural place of residence. These variables were not determined a priori, but were based on parsimony, theoretical relevance and practical significance with HIV/AIDS testing.

Statistical analyses

The data were analysed with Stata version 14.0. The analysis was done in three steps. The first step was the computation of the prevalence of HIV testing in Mozambique and Kenya. The second step was a bivariate analysis that calculated the proportions of HIV/AIDS testing across the outcome variable with their significance levels (Table 1). The last step of the analysis was a binary logistic analysis, using the variables that were significant from the chi-squared test of fitness, which was carried out in a hierarchical order. Three models were used for the logistic regression analysis. The first model, Model I, looked at the bivariate analysis of comprehensive knowledge of HIV/AIDS and HIV/AIDS testing in Mozambique and Kenya. In Model II, individual variables were added to Model I. Finally, individual and contextual variables were added to form the complete model.

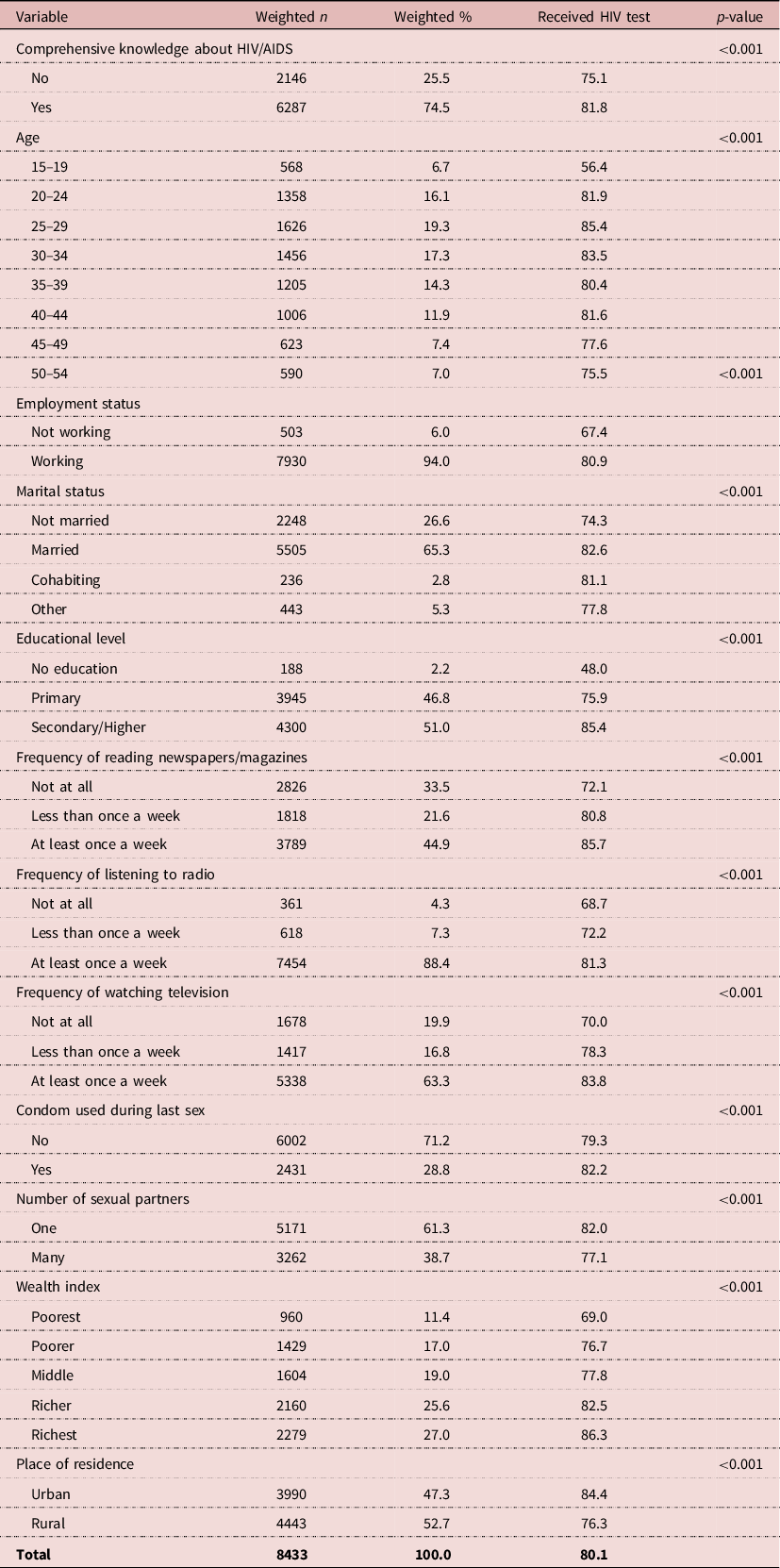

Table 1. HIV testing by explanatory variables in Mozambique

Results

HIV testing by explanatory variables in Mozambique

Table 1 shows HIV testing by explanatory variables in Mozambique. The overall prevalence of HIV testing among men in Mozambique was 46.7%. Apart from number of sexual partners, all the explanatory variables showed significant associations with HIV testing among men in Mozambique. More than half (55.3%) of the men who had comprehensive knowledge of HIV/AIDS tested for their HIV status. In Mozambique, the age groups of men with the largest proportions testing for HIV were 25–29 years (57.0%), 30–39 years (52.1%) and 55–59 years (51.8%). Less than half (49.1%) of men who were working had tested for HIV. A greater proportion of men who were cohabiting (57.3%) had tested for HIV than those of other marital statuses. The richest (67.9%), those with secondary/higher education (63.8%), those who read newspapers/magazines at least once a week (69.7%), those who listened to radio at least once a week (53.2%), those who watched television (64.6%), those who used a condom during sex (62.8%) and those residing in urban centres (59.0%) were the groups reporting the highest proportions of HIV testing. Also, less than half (49.3%) of the men with multiple sexual partners had tested for HIV.

HIV testing by explanatory variables in Kenya

Table 2 shows HIV testing by explanatory variables in Kenya. The overall prevalence of HIV testing in Kenya was 80.1%. All the explanatory variables had significant associations with HIV testing among men in Kenya. A large majority of the men who had comprehensive knowledge of HIV/AIDS (81.8%) had tested for HIV. In Kenya, the age groups of men with the largest proportions testing for HIV were 15–19 years (56.4%), 20–24 years (81.9%), 25–29 years (85.4%), 30–34 years (83.5%), 35–39 years (80.4%), 40–44 years (81.6%), 45–49 years (77.6%) and 50–55 years (75.5%). A greater proportion of men who were working (80.9%) and who were married (82.6%) tested for HIV than those who were not working or who were unmarried. The richest (86.3%), those with secondary/higher education (85.4%), those who were exposed to newspapers at least once a week (85.7%), those who were exposed to radio at least once a week (81.3%), those who were exposed to television (83.8%), those who used a condom during sex (82.2%) and those residing in urban centres (84.4%) were the groups reporting the highest proportions of HIV testing. Also, a greater proportion (82.0%) of the men with one sexual partner tested for HIV than those with many sexual partners.

Table 2. HIV testing by explanatory variables in Kenya

Binary logistic regression of the association between comprehensive HIV/AIDs knowledge and HIV testing

Table 3 shows the binary logistic regression of the association between comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge and HIV testing among men in Mozambique and Kenya. Men in Mozambique who had comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge (aOR=1.26, CI: 1.07–1.47) were more likely to test for HIV compared with their counterparts who had no comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge. Similarly, in Kenya, those who had comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge (AOR=1.23, CI: 1.09–1.39) were also more likely to test for HIV compared with their counterparts who had no comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge.

Table 3. Binary logistic regression on the association between comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge and HIV testing among men in Mozambique and Kenya

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Ref. = reference category.

Discussion

This study examined the association between comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge and HIV testing among men in Kenya and Mozambique. The prevalence of HIV testing among men was higher in Kenya (80.1%) than in Mozambique (46.7%). Staveteig et al. (Reference Staveteig, Wang, Head, Bradley and Nybro2013) reported similar but lower HIV testing prevalences for men in Kenya (40.4%) and Mozambique (17.2%). Other previous studies in Kenya (Cherutich et al., Reference Cherutich, Kaiser, Galbraith, Williamson, Shiraishi and Ngare2012; Waruiru et al., Reference Waruiru, Ngare, Ssempijja, Gachuki, Njoroge, Oluoch and Kim2014) and Mozambique (De Schacht et al., Reference De Schacht, Hoffman, Mabunda, Lucas, Alons, Madonela and Guay2014; Horth et al., Reference Horth, Cummings, Young, Mirjahangir, Sathane and Nala2015) also reported a lower prevalence of HIV testing among men than the present study. The variations in the prevalence figures could be attributed to the different periods in which the studies were conducted. Perhaps the high prevalence of HIV testing among men in the two countries recorded in the present study could be attributed to HIV testing intervention programmes implemented in these countries in the past few years.

In Mozambique, for instance, increased funding from foreign governments and international organizations has resulted in a significant increase in the number of health care units providing voluntary counselling and testing services (Yao et al., Reference Yao, Agadjanian and Murray2014). Apart from the improved access to, and minimization of, structural barriers to HIV testing (Yao et al., Reference Yao, Agadjanian and Murray2014; Ha et al., Reference Ha, Van Lith, Mallalieu, Chidassicua, Pinho, Devos and Wirtz2019), the use of community-based advocacy and intervention programmes such as ‘Male Champions’ and male-to-male community health agents to counsel male partners on the importance HIV testing has also contributed to an increased HIV testing uptake among men in Mozambique (Audet et al., Reference Audet, Blevins, Chire, Aliyu, Vaz, Antonio and Vermund2016).

With regards to Kenya, increased HIV testing rates among men had been associated with interventions such as male involvement in Prevention of Mother-To-Child HIV Transmission (PMTCT) services (Osoti et al., Reference Osoti, John-Stewart, Kiarie, Richardson, Kinuthia, Krakowiak and Farquhar2014), as well as the use of home-based voluntary counselling and testing services (Aluisio et al., Reference Aluisio, Richardson, Bosire, John-Stewart, Mbori-Ngacha and Farquhar2011; Waruiru et al., Reference Waruiru, Ngare, Ssempijja, Gachuki, Njoroge, Oluoch and Kim2014). Kenya and Mozambique are also beneficiaries of the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which has contributed immensely towards the management and prevention of HIV/AIDS, including scaling-up of HIV testing programmes in the two countries (El-Sadr et al., Reference El-Sadr, Holmes, Mugyenyi, Thirumurthy, Ellerbrock and Ferris2012; Fauci & Eisinger, Reference Fauci and Eisinger2018).

Despite the relatively high rate of HIV testing uptake among men in Kenya and Mozambique, Kenya recorded a higher testing rate (80.1%) than Mozambique (53.3%). The high level of stigma towards people living with HIV/AIDS in Mozambique (20.7%) than Kenya (11.9%) (UNAIDS, 2017) might have contributed to the lower testing rate among men in Mozambique. Recent studies have shown that stigma continues to be one of the major barriers to HIV testing uptake among men in Mozambique (Ha et al., Reference Ha, Van Lith, Mallalieu, Chidassicua, Pinho, Devos and Wirtz2019) and elsewhere in SSA (Hatzold et al., Reference Hatzold, Gudukeya, Mutseta, Chilongosi, Nalubamba, Nkhoma and Corbett2019; Hlongwa et al., Reference Hlongwa, Mashamba-Thompson, Makhunga and Hlongwana2020; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Rosen, Allen, Benbella, Camacho and Cortopassi2020). Meanwhile, high HIV testing uptake among men is important for the early initiation of treatment and to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with the disease (Hatzold et al., Reference Hatzold, Gudukeya, Mutseta, Chilongosi, Nalubamba, Nkhoma and Corbett2019). This calls for interventions to scale up HIV testing among men, especially in Mozambique where only 61% of men who have HIV know their status, compared with 88% in Kenya (UNAIDS, 2019).

In this study, comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge was found to be associated with a higher prevalence and odds of HIV testing among men in both Kenya and Mozambique. Specifically, men who had comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge in Kenya (81.8%) and Mozambique (55.3%) had higher odds of testing for HIV compared with their counterparts who had no comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge. This finding was significant, even after controlling for age, employment status, marital status, educational level, condom use, wealth quintile, type of residence and exposure to newspapers, radio or television. The findings support those of previous studies conducted in Uganda (Gage & Ali, Reference Gage and Ali2005), Burkina Faso (De Allegri et al., Reference De Allegri, Agier, Tiendrebeogo, Louis, Yé, Mueller and Sarker2015) and Ghana (Nyarko & Sparks, Reference Nyarko and Sparks2020). One possible reason for this finding is that men with comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge are more likely to have higher education and increased access to information from the media, as found in the present study and in previous studies in SSA (Asaolu et al., Reference Asaolu, Gunn, Center, Koss, Iwelunmor and Ehiri2016; Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, Rosen, Wong and Carrasco2019). Men with comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge are better informed about the importance of HIV testing and where to access an HIV test, which may increase their likelihood of getting tested (Bwambale et al., Reference Bwambale, Ssali, Byaruhanga, Kalyango and Karamagi2008; Onsomu et al., Reference Onsomu, Moore, Abuya, Valentine and Duren-Winfield2013; Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, Rosen, Wong and Carrasco2019). Conversely, low educational attainment and limited access to information on HIV/AIDS has been shown to be related to low levels of HIV/AIDS knowledge and its associated misinformation, misconceptions and stigma (Bwambale et al., Reference Bwambale, Ssali, Byaruhanga, Kalyango and Karamagi2008; Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Ying, Tarr and Barnabas2015; Mumtaz et al., Reference Mumtaz, Hilmi, Majed and Abu-Raddad2020), which are among the major barriers to HIV test uptake among men in Kenya and Mozambique (Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, Rosen, Wong and Carrasco2019). Thus, improving HIV/AIDS knowledge through the dissemination of information in communities could reduce the misconceptions, misinformation and stigma associated with the disease (Stephenson et al., Reference Stephenson, Elfstrom and Winter2013). This could further improve testing rate among men in both countries.

This study’s major strength was the use of nationally representative data. However, it had its limitations. First, data were limited to 2015 and 2014 DHS data, so HIV testing prevalence figures were limited to the periods for which these DHS data were collected. For example, new developments in the area of HIV testing such as the large-scale introduction of oral self-test HIV kits in Kenya in the year 2017 (UNAIDS, 2017) might have significantly changed the prevalence of HIV testing in the country. Secondly, the cross-sectional nature of the study did not allow for causality to be inferred from the findings. Additionally, HIV test self-reporting is subject to recall bias, which can result in under- or over-reporting. Finally, some factors related to culture and religion were not included in the analysis due to the absence of complete data on these variables in the datasets.

In conclusion, this study found a significant association between comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge and HIV testing among men in Kenya and Mozambique. Therefore, to improve the HIV testing rate among men in these countries, it is important that interventions are geared towards improvement in comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge, especially among men. This would ensure the realization of the global HIV/AIDS target of 95-95-95 by the year 2030 (Ajayi et al., Reference Ajayi, Awopegba, Adeagbo and Ushie2020). Also, ensuring that all men have access to comprehensive HIV/AIDS education could reduce the stigma and misinformation associated with the disease, thereby further improving HIV testing uptake.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial entity or not-for-profit organization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

The DHS reports that ethical clearances were obtained from the Ethics Committee of ORC Macro Inc., as well as from the ethics boards of partner organizations in Mozambique and Kenya, including the Ministries of Health. The DHS follows the standards for ensuring the protection of respondents’ privacy. ICF International ensures that the survey complies with the United States Department of Health and Human Services’ regulations for the respect of human subjects. This was a secondary analysis of data and therefore no further approval was required since the data are available in the public domain. Further information about the DHS data usage and ethical standards are available at http://goo.gl/ny8T6X.