Making archaeology accessible underpins the archaeological process. Creating opportunities for public access to a site during investigation is more and more frequently requested as part of the planning conditions of developments set by local council authorities. Large construction projects with challenging health and safety constraints, along with a lack of funding from developers for anything but the essential excavation and recording of archaeological remains, can restrict how much access to an archaeological site the public can have. The case study of the Westgate Pop Up Museum was proposed as a solution to these issues.

A pop-up museum is a short-term exhibition that can tell the story of a site long before objects are deposited in a conventional museum and a publication is produced. It takes advantage of the immediacy of an excavation. The temporary nature allows for unconventional object displays, and different locations, such as shops, can be utilized. A short-term exhibition can change displays and narratives rapidly and can respond to new discoveries. A pop-up museum can provide access to the site without the public needing to step onto the site itself.

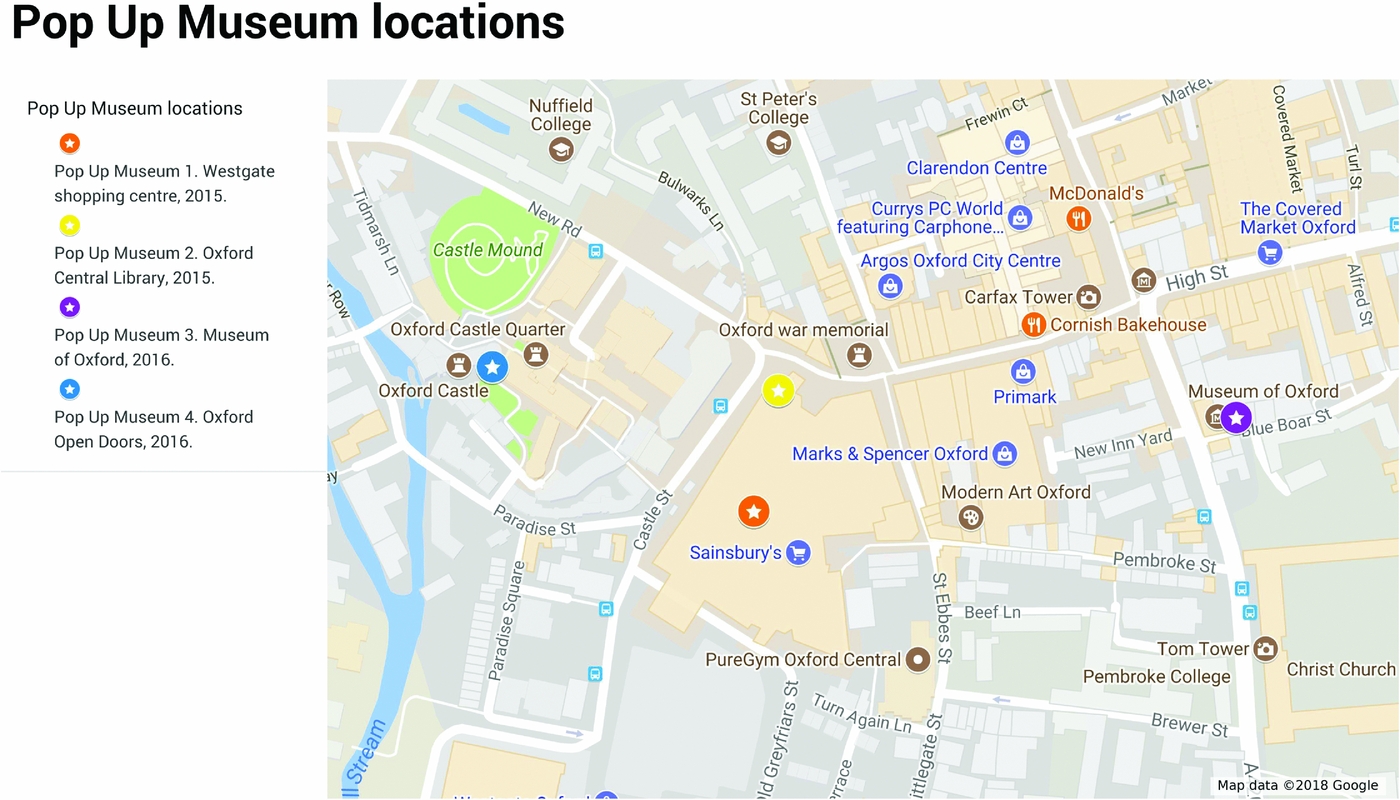

This article provides a step-by-step approach to setting up and running a temporary exhibition for an archaeological project using the Westgate Pop Up Museum as a case study. The Westgate Pop Up Museum was part of an extensive outreach program designed to run alongside the archaeological excavations. It was a temporary exhibition based consecutively in four different locations across the city of Oxford, UK (Figure 1). Pop Up Museum 1 was in the Westgate Shopping Centre, before it was redeveloped, for six weeks in July and August 2015. It then immediately moved to the Oxford Central Library for a further seven weeks as Pop Up Museum 2. There was a six-month break before Pop Up Museum 3 was held at the Gallery in the Museum of Oxford for seven weeks, starting in March 2016. The last time it was set up was in September 2016 for two days as part of the Open Doors festival in Oxford. It attracted more than 7,500 visitors, and 5,000 of those attended Pop Up Museum 3.

FIGURE 1. Westgate Pop Up Museum locations, Oxford (using Google Maps).

Westgate Oxford is a commercial redevelopment of a large shopping complex in the center of Oxford, with clients Westgate Oxford Alliance and principal contractor Laing O'Rourke. The excavations, carried out by Oxford Archaeology, between 2014 and 2016, were required as part of UK Planning Guidelines. They were the largest ever undertaken in the city and principally focused on a large medieval suburban friary. The project won Best Archaeological Project 2016 at the prestigious national British Archaeological Awards. The outreach program, including the Pop Up Museum, a series of “open site” days, a school engagement program, and a lecture series, along with other community collaborations, was a significant contributing factor in gaining this prize.

STEP 1. SETTING UP THE POP UP MUSEUM: SET OUT A BRIEF

A pop-up museum must be mentioned in the initial brief set out by the local planning authority. This sets out all the requirements the developer must meet to achieve planning permission for the development.

The United Kingdom has a long history of providing access to archaeology that stretches back to antiquarians putting on displays to their friends of all the artifacts they had collected. The rise of rescue archaeology and some high-profile cases to save national heritage led to the introduction of planning policies that guide developments in the United Kingdom today. The National Planning Policy Framework states that “local planning authorities should make information about the significance of the historic environment gathered as part of plan-making or development management publicly accessible” (Department for Communities and Local Government 2012). These national guidelines underpin the briefs set out by the local authority.

A brief for the Westgate Oxford development was set by the local planning authority, Oxford City Council. The Oxford city archaeologist, David Radford, played a crucial role in persuading the developer, and whoever tendered for the archaeological element of the work at Westgate, that a temporary exhibition should be an integral part of the project. Once Oxford Archaeology was appointed, a Written Scheme of Investigation (WSI) was written in response to this brief. The WSI for the Westgate project stated:

It is intended to have a temporary exhibition space (probably within one of the vacant shop units within the Westgate Mall). It is proposed that this will be in place for 4 months (July–Oct 2015). This will exhibit finds from the 1960–70’s excavations at Westgate with finds from the Main Works excavations, the finds will be supported by informative poster displays. Once a week there will be show and tell events where the public can see and handle finds from the excavations [Oxford Archaeology 2015].

The Pop Up Museum would not have happened were it not for the brief set by the local authority and the response by Oxford Archaeology explaining how it would ensure that this condition was met.

STEP 2. SETTING UP THE POP UP MUSEUM: WORK WITH YOUR PARTNERS

A commercial archaeological company needs partners to set up and run the outreach element of a commercial project. Such partners will have contacts and networks that can be used to ensure that the right skills are available. These can range from experts to monitor the environmental conditions within the space to city councilors who can help with promoting the pop-up museum.

It is key in setting up an outreach element that the organizations you will require assistance from are all involved in the decision making. The Westgate Oxford project had an Advisory Panel with representatives from the developer, Julian Mabbitt (Land Securities); the contractor, Ian Jolliff (Laing O'Rourke); the consultant firm, Myk Flitcroft (CgMs Consulting); the city archaeologist, David Radford (Oxford City Council); the archaeological contractor, Project Manager Ben Ford and Outreach Officer Becky Peacock (Oxford Archaeology); a national organization, Chris Welch (Historic England); local organizations/societies, Jane Baldwin (Oxford Preservation Trust) and Jane Harrison (Archaeology of East Oxford project); and academia, Dierdre O'Sullivan (Leicester University), George Lambrick (Oxford University), and Tom Hassall (archaeological director of previous work at the Westgate).

The role of the panel was to coordinate the academic output of the project as well as provide support and contacts for the outreach elements. This was a key forum to discuss the pop-up museum, and it kept everyone up to date on progress. The local authorities, as well as initiating the project, were the ones who could then liaise with different council departments and ensure that as many people as possible, both within the council and across the city, knew about the Pop Up Museum.

STEP 3. SETTING UP THE POP UP MUSEUM: CHOOSE A LOCATION AND OPENING TIMES

The location for the temporary exhibition must be relevant to the project that is being displayed. This will provide the public visiting the exhibition a feeling of being as close as possible to the work being carried out and ensures that the contents on display are timely and relevant. Once a location is decided, who will be stewarding the displays and when can be established. This allows for the opening times to be advertised, and the public can then arrange to visit your pop-up museum.

Working together, the various partners in the project confirmed a location for the Pop Up Museum in the main Westgate mall, prior to its demolition and remodeling. The developers, and therefore the ones funding the Pop Up Museum, were key in providing the retail unit for Pop Up Museum 1 without rent for the duration, and they made sure that the space was equipped and ready to use. The development company owned the shopping center and so were able to offer the services of security personnel and were a main point of contact for access to the retail unit. Two vacant shops were available, and a corner position was chosen. It was the smaller unit of the two, but the location was much more visible and had windows on two sides, providing more opportunities to display to passersby and entice them in (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. View of the windows of Pop Up Museum 1 from the outside, main mall, Westgate Shopping Centre, Oxford (photograph by Oxford Archaeology).

Running the museum involved volunteers. Oxford Archaeology did not use volunteers at the time, and so we contacted one of the Advisory Panel members, Jane Harrison. She had led some voluntary fieldwork research during the Archaeology of East Oxford project. She put us in touch with the volunteers from that project, and having this connection made recruiting volunteers much easier, as they were all familiar with archaeology. Stewarding the exhibition and advertising the opening times for the Pop Up Museum were entirely reliant upon when the volunteers were available.

STEP 4. SETTING UP THE POP UP MUSEUM: MAKE DISPLAYS FLEXIBLE

A pop-up museum needs to reflect the changing story of an archaeological site. The displays need to have a degree of flexibility designed into them. The purpose of the Pop Up Museum was to tell the story of the discoveries we were making on-site while the exhibition was running. There was no physical material from the current excavations when the layout was being planned. A modular approach was taken so that the displays and cabinets could be added to and moved around if necessary, with some of the cases filled with the finds from the previous excavations as an initial display. Some cases were left empty, ready for new finds to be displayed as soon as they were excavated, and these were later filled with objects such as pottery that had not been reconstructed yet. It allowed for a “just found” feeling to be conveyed to the public (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Display cases with “just found” objects, Pop Up Museum 1 (photograph by Oxford Archaeology).

The Pop Up Museum also needed to tell the story of the Westgate development and the archaeological discoveries made there over the last 50 years. Extensive excavations were carried out under the direction of Tom Hassall when the original shopping center was developed in the 1960s and 1970s. These excavations produced a wealth of information about the medieval friary that once stood on the site. The artifacts were with the local museum service, and the site had been published in the local journal, Oxoniensia. There was plenty of material that could be loaned for display by the County Museum Service. In addition, it also provided environmental monitoring of the space to ensure the conservation of the finds while they were on loan to the Pop Up Museum. It also provided collapsible and podium-style cases, which were critical in allowing the exhibition to move locations and for the display to be flexible and modular.

A weekly show-and-tell session, as outlined in the WSI, provided an opportunity to show finds before they were cleaned and dried. These sessions were also themed to showcase the different techniques that were being used on the project.

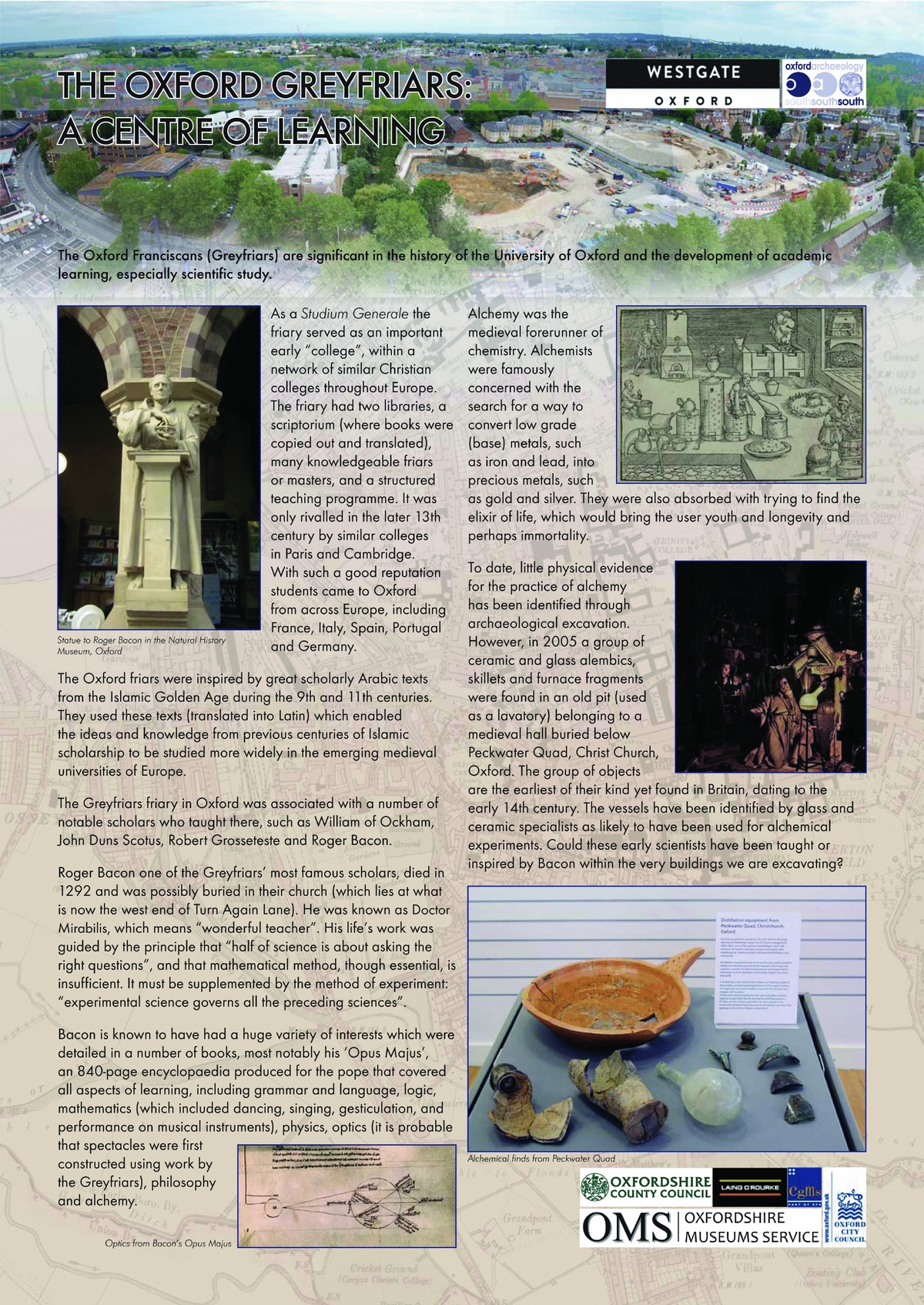

Information panels in the style of posters were designed around different topics and were on A1-size sheets (594 × 841 mm) to make them easier to redisplay if necessary. They provided the background information to the finds on display. They had themes, and these could be expanded as required. For example, one of the first information panels produced was about the Greyfriars, the Franciscan order of monks at the site (Figure 4), and a second panel focused on the eminent monk and early scientist Roger Bacon (Figure 5). We later designed a panel that went into more detail about the buildings that had been uncovered in 2015, and these all fit together well, so none of the previous panels needed to be redesigned.

FIGURE 4. Information panel about the Greyfriars (produced by Oxford Archaeology).

FIGURE 5. Information panel about Roger Bacon (produced by Oxford Archaeology).

In Pop Up Museum 3 at the Town Hall Gallery, the waterlogged leather and wooden finds could be displayed. We had them in a case in individual trays of water. The long-term conservation of these finds means that they were unlikely to be displayed for many years, if at all. The short-term exhibition lent itself to displaying these finds, as the conservation impacts were minimal. This again added to the “just found” element in the temporary exhibition. We were displaying the objects in the same way that we have to look after the finds once they are lifted from the ground. It is as close to seeing the excavation methods of a site as possible while not being on the site itself.

STEP 5. RUNNING THE MUSEUM: COORDINATE EVENTS FOR MAXIMUM IMPACT

The temporary exhibition will only have a short time to attract visitors. Partners in the project and the developers will want to know that the extra funding required for the pop-up museum has been well spent. This will be best demonstrated in showing the number of people who have visited the museum. Coordinated promotion of the museum around different events will increase the number of visitors and the overall impact of the pop-up museum.

Our Pop Up Museum became very popular and a focal point for other elements of the outreach program. The opening was timed to coincide with a national event, the Festival of Archaeology, and the first of the two “open site” days, so there was plenty of publicity for the Pop Up Museum. It opened at the end of June 2015 and so was also well timed for the school term. There was a schools program as part of the outreach work. School activities were scheduled to include the Pop Up Museum. Cheney School had a Field Day that included learning geophysical survey techniques in the Oxford Preservation Trust Gardens, a walking tour of Oxford, and a guided site tour. The Pop Up Museum provided a base meeting place as the class was split up for the different activities. It was a good location to provide background information about the archaeology of the site.

The Pop Up Museum was also a focal point for other organizations in the city. The Museum of Oxford had a temporary exhibition that was due to open in its gallery space celebrating its fortieth anniversary. It used the Pop Up Museum for a day to advertise the exhibition and hosted themed activities relating to it.

Through the growing popularity of the Pop Up Museum it became evident that the initial six-week duration was too short. The WSI also stated that it would be open for four months. We asked the Advisory Panel for help. The Oxfordshire County councilor for Property, Cultural and Community Services got in touch and said that there was a strong possibility that the Pop Up Museum could move into the Central Library. It shares a building with the Westgate Shopping Centre and so was ideally located close to the site and to Pop Up Museum 1. The timing also worked well because it was now going to be open for the second “open site” day. This was timed for the Oxford Open Doors festival, part of the national Heritage Open Days, to maximize publicity. The move to the library allowed the Pop Up Museum to be open at the same time as the library and so did not require further volunteer rotas to be drawn up, and this helped to reduce the administration time. We had a fixed budget for the six-week duration, so it was imperative to find cost-effective ways to keep it running. Reusing display material and not making changes to the finds on display reduced the setup costs when the museum moved locations, as specialists were not required to analyze any of the finds.

A new location could not be found immediately following the display in the library. However, the Museum of Oxford was able to return the favor we had offered it, and we organized an expanded exhibition in its gallery space for the following spring.

STEP 6. RUNNING THE POP UP MUSEUM: KEEP THE STORY EVOLVING

As a pop-up museum develops, a new story or focus will generate continued interest and repeat visits. The Museum of Oxford Gallery was a much larger display space. This was not a problem in terms of content, as excavations on the site had continued for a further six months, and many new discoveries had been made. There had been regular press updates, and this had created an appetite for a larger exhibition. Also, the site over this period had become even more challenging and restrictive, and so it was not possible to have any further “open site” days.

The exhibition mostly consisted of finds from the current excavations, including a civil war halberd and Saxon pendant as well as many more finds belonging to the Greyfriars, giving a varied insight into their lives. More display panels were designed, and a large photogrammetry picture of a site area was on display (Figure 6). As much of the display material was current, more internal finds specialists, such as medieval pottery and brick and tile specialists, were required. But costs were reduced by reusing some material from the previous Pop Up Museums. Volunteers from both the Museum of Oxford and the previous Pop Up Museums were used as stewards. All the volunteers were coordinated by the Museum of Oxford. This reduced our administration costs.

FIGURE 6. Photogrammetry image on display, Pop Up Museum 3 (photograph by Oxford Archaeology).

The final location for the Pop Up Museum was at the request of another of our partners on the Advisory Panel, the Oxford Preservation Trust. Oxford Archaeology was given the education center at the Oxford Castle Unlocked attraction for Open Doors 2016 (Figure 7). The event was for two days over the heritage festival weekend and was used to provide site updates to the public and show 3-D models of the site, which had taken time to process. It acted as a focal point for other projects in the city and showcased the varied work of Oxford Archaeology and commercial archaeology in the United Kingdom.

FIGURE 7. Public viewing the finds in display cabinets and the table of old photographs of St. Ebbe's, Pop Up Museum 4 (photograph by Oxford Archaeology).

STEP 7. RUNNING THE POP UP MUSEUM: CREATE A HUB

A pop-up museum can act as a focal point for the whole project, and in this role it can start to act as a hub. It can be used by the client to showcase what is happening on the site and explain the construction processes of the project to other partners. Other heritage organizations can use the pop-up museum to promote events and activities for their own outcomes.

As the exhibition grew in popularity it also attracted more organizations that wanted to work with the archaeology revealed at the site. The Museum of Oxford has a reminiscences group called Memory Lane, and a session was themed around the area of Westgate and the inhabitants of St. Ebbe's. It was suggested at an Advisory Panel meeting that this could be extended to include the local St. Ebbe's primary school, and a multigenerational session was set up. The schoolchildren asked the older generation what it was like living there in the 1950s, and artifacts from the Pop Up Museum displays, such as a chamber pot, lemonade bottles with a marble in them, and so on, were brought along to aid the reminiscences (Figure 8). Archivists from the local Deaf and Hard of Hearing Centre, located very close to the site, also shared some of their material at the sessions. They invited users of the center along, and a British Sign Language interpreter attended the session as well.

FIGURE 8. Doll object used in the reminiscences sessions, Pop Up Museum 3 (photograph by Oxford Archaeology).

The wealth of material and valuable information from people's memories that was collected during these sessions inspired one of the artists commissioned by Westgate Oxford, Rachel Barberesi, to theme her project UrbanSuburban on the people of St. Ebbe's. An artist's book was produced, along with a blog, and it went on to be part of an exhibition at Modern Art Oxford in July 2017. The Westgate Pop Up Museum contributed materials for reminiscence for this project and was the initial starting point.

STEP 8. TAKING DOWN THE EXHIBITION: KEEP THE STORY ALIVE

Once the temporary exhibition finishes in a location, it is essential to make sure that it is easily accessible should further display be required. The storage and location of the finds need to be taken into consideration. The public's continued interest is required to keep a temporary exhibition relevant, and new ways of displaying the information can be explored.

Each time the Pop Up Museum moved and awaited a new location, the finds and display materials were packed away in museum and archive boxes for safe removal and storage. The reconstructed pottery and window glass on loan from the Museum Service from the original excavations went back to the main museum. But it was kept out of deep storage for ease of retrieval, as there may be a request for a display on short notice. The finds from the current excavations are part of the archive being processed and analyzed for publication with the in-house specialists at Oxford Archaeology. They are distributed within our organization but are easily recalled for display when required. All the artifact labels and display panels were collected by the finds team and stored together.

The wealth and variety of material that was collected by Rachel Barberesi and by the reminiscences officer and the stories that visitors to the Pop Up Museum shared with volunteers were very difficult to record and share for others to learn from. There were photographs, newspaper cuttings, objects, and verbal accounts that we could not collect for the main site archive, as they were not part of the archaeological remains of the site, though still a very valuable resource for learning about the history of the area. It was this that led to developing a Heritage Lottery Fund project that would create a digital archive and interactive map for people to share their stories about living in St. Ebbe's. Just as the Pop Up Museum was such a crucial tool for engaging with the public, both for collecting the information and for telling the story of the area and bringing partner organizations together, a pop-up museum would be an integral part of the Heritage Lottery Fund bid. Support was gathered from many of the partners and members of the Advisory Panel. However, even though this particular bid was not successful (decision October 2017), the level of interest in the project is still strong, and elements of the project will likely be taken forward by Oxford Archaeology and its partners.

CONCLUSION: LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE WESTGATE POP UP MUSEUM

It must be stressed how much in-kind support contributed to the success of the Westgate Pop Up Museum. The commercial rental costs of venues and paying staff rather than using volunteers’ time to run it would have made the project too expensive, and it would not have continued. Public demand was key in ensuring that new display locations for the Pop Up Museum were found. Making each location a new experience, with a different layout or new objects on display, made sure that people wanted to know where and when the next Pop Up Museum would be. Other heritage organizations used the temporary and timely nature of the Pop Up Museum for their own targets and outcomes, ensuring different visitor experiences over the life of the museum. A temporary exhibition is both quick to assemble and quick to put into storage. The very nature of it being temporary allows it to remain current and to respond to key site discoveries and changes to interpretation. A temporary exhibition provides a space that allows for more creativity in the display of objects. The pottery found on-site could be processed and displayed within days of being found, giving an immediacy to the display that a conventional museum cannot replicate, due to the time taken for analysis and deposition of the artifacts.

If Oxford Archaeology had used more formal feedback methods, such as questionnaires about the experience, we would have been able to use these as evidence in the Heritage Lottery Fund bid and may have been able to secure further funding from the developers or other partners involved in the project. The visitors book we used only recorded general comments. A voluntary questionnaire would have been able to record experiences and also learning outcomes and the wish for further site updates to be disseminated through pop-up museums.

A pop-up museum is an excellent tool for presenting an archaeological project by showing through regularly changing displays how the project and the understanding of the site narrative is evolving. It can be changed very quickly by keeping a flexible format with multiple display cabinets. A modular approach with broad themes can emphasize new focal points depending on the audience, location, budget, and duration of the exhibition. A location where the archaeology can be presented away from a construction site, with the access and health and safety restrictions that these bring, provides both the client and the archaeological contractor a means to communicate the story of the project in an accessible and easy-to-reach place. Using the pop-up museum format as a hub for other groups and organizations can lead to presenting the archaeology in new and engaging ways through art and reminiscence sessions, as well as being an excellent tool for engaging new partners, all leading to new and interesting projects.

Data Availability Statement

Original data were not used in the preparation of the essay. Further information about the project and Oxford Archaeology can be found at http://www.oxfordarchaeology.com.