Introduction

The World Health Organization (2021) defines “palliative care” as an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing problems associated with life-threatening illness through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial, or spiritual. Notably, addressing the spiritual needs of patients is a basic factor of high quality palliative care. “Spirituality” refers to a fundamental element of the human experience involving the individual’s relationship with the meaning of life, purpose, connections with others, and a sense of peace (Cai et al. Reference Cai, Guo and Luo2020). Accordingly, spiritual care involves attentiveness to a patient’s values and beliefs (Hvidt et al. Reference Hvidt, Nielsen and Kørup2020). Today, there is an urgent need to ensure that spiritual care is part of palliative care: approximately 1 in 5 palliative care patients are considered “spirituality distressed” (Gielen et al. Reference Gielen, Bhatnagar and Chaturvedi2017). Moreover, the relatively high prevalence of cancer among the general population – 19.3 million new cancer cases were estimated to have occurred worldwide in 2020 (Sung et al. Reference Sung, Ferlay and Siegel2021) – and among palliative care patients also underscores the need to ensure that spiritual care is part of palliative care: a spiritual needs assessment study with cancer patients in a Northern European metropolitan region showed that almost all patients (94%) reported at least one spiritual need (Höcker et al. Reference Höcker, Krüll and Koch2014). In light of the need for spiritual care, palliative care must involve not only symptom control but also holistic treatment.

Today, the high frequency of aging populations across the globe is increasing demand for palliative care, presenting a tough challenge for many countries faced with complex and diverse health-care needs (Chen Reference Chen2021). It has been estimated that approximately 7.5 million people need palliative care in China (Ding et al. Reference Ding, Huang and Wang2021); however, only 3% of this population receives palliative care services (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Xu and Yue2020). With aging populations’ increasing demand for palliative care, a substantial gap in the availability of palliative care has emerged. A palliative care model based solely on specialist providers cannot meet the demand (Pesut et al. Reference Pesut, Hooper and Lehbauer2014); it is necessary to recognize that volunteers are an integral resource in palliative care. As a social cause, voluntary service embodies the spirit of mutual assistance, cooperation, dedication, and great love, which promotes social civilization. Palliative care volunteers freely give their time with no expectation of financial gain, serving within an organized structure beyond preexisting social relations or familial ties to improve the physical, psychological, and spiritual quality of life of adults and children with life-limiting conditions and those close to them (i.e., family members and others) (Goossensen et al. Reference Goossensen, Somsen and Scott2016). They can provide various services, including social, emotional, informational, practical, spiritual, respite, physical, and bereavement support (Claxton-Oldfield et al. Reference Claxton-Oldfield, Hastings and Claxton-Oldfield2008) and often work as liaisons to fill gaps between professionals and family members (Vanderstichelen et al. Reference Vanderstichelen, Cohen and Van Wesemael2020). Along these lines, volunteers take on an informal educative role in their communities, both in terms of destigmatizing palliative care and promoting and reinforcing the reputations of local palliative (Morris et al. Reference Morris, Payne and Ockenden2017). Notably, palliative care interventions that involve volunteers can positively impact family satisfaction with care and even lengthen patient survival (Candy et al. Reference Candy, France and Low2015). Moreover, the contributions of palliative care volunteers have reduced palliative care costs by an estimated 23% (Burbeck et al. Reference Burbeck, Low and Sampson2014). Given China’s limited health-care resources and the tough challenge of aging the nation currently faces, volunteers are expected to play a more important role in palliative care in the future (Fast et al. Reference Fast, Keating and Otfinowski2004). Although scholars have emphasized the importance of spiritual care in the palliative context (Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Pang and Shiu2010; van de Geer et al. Reference van de Geer, Groot and Andela2017), existing literature on spiritual care rarely considers the role of volunteers.

In the process of providing services, volunteers have to deal with the heavy theme of death and have to take care of patients approaching death (Yeun Reference Yeun2020). This working environment makes them prone to stress, which may increase negative attitudes toward palliative care and thereby reduce service quality (Brown Reference Brown2011; Claxton-Oldfield Reference Claxton-Oldfield2016). In order to effectively improve volunteers’ spiritual care competence, it is necessary to shed light on their attitudes toward palliative care. While some work has been done on volunteers’ attitudes toward palliative care (Addington-Hall and Karlsen Reference Addington-Hall and Karlsen2005), no studies have yet investigated volunteers’ spiritual care competence alongside their attitudes toward palliative care or their relationship. Thus, this study examined spiritual care competence and the attitudes toward palliative care among palliative care volunteers.

Methods

Aims

The study aimed to (1) measure volunteers’ spiritual care competence; (2) identify factors associated with volunteers’ spiritual care competence; and (3) explore the relationship between volunteers’ spiritual care competence and attitudes toward palliative care.

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional descriptive study using general characteristics and 2 scales for spiritual care competence and palliative care attitude among volunteers. We developed the general characteristics part based on a literature review. Meanwhile, for spiritual care competence, we adopted the scale developed by Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Qiu and Fan2016, Reference Chen, Qiu and Zhang2017). For attitude toward palliative care, we adopted the Attitudes Toward Care of the Dying Scale developed by Frommelt (Reference Frommelt2003) and the attitude questionnaire developed by Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Hu and Chiu2005). Before the formal investigation, we recruited 41 volunteers for a pre-investigation to examine the reliability of the scales. The Cronbach’s α for the Spiritual Care Competence Scale was 0.916, and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) was 0.931. The Cronbach’s α for the palliative care attitude scale was 0.768, and the KMO was 0.624. The design of the study was approved by the ethical review committee of Ninth People’s Hospital, which is affiliated with the medical school of Shanghai Jiaotong University (no. SH9H-2021-T11-1).

Sample and setting

A rule of thumb for multivariable analyses is that the sample size should be 5, 10, or 20 times the number of variables (Norman et al. Reference Norman, Monteiro and Salama2012). Because there were 9 variables in this study, the sample size was determined to be 180. Convenience sampling was used to recruit participants from typical voluntary organizations providing palliative care services, including volunteer organizations open to the general public and volunteer organizations made up of college students in Shanghai, China, in January 2019. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) volunteers involved in palliative care or having the will to participate in palliative care and (2) volunteers able to understand the study purpose and provide informed consent. Ultimately, 385 volunteers participated in the study. Because over half the volunteers were college students, we divided the participants into 2 groups – a “college student volunteers” group and a “social volunteers” group (social volunteers have work experience and are not college students but members of the general population) – and compared their results.

General characteristics

We collected participants’ general characteristics, namely sex, age, educational background, marital status, religious beliefs, occupational status, past participation in palliative care, previous exposure to knowledge about palliative care, and palliative care training.

Spiritual care competence

The measurement scales for spiritual care competence are limited. van Leeuwen et al. (Reference van Leeuwen, Tiesinga and Middel2009) developed the Spiritual Care Competence Scale based on the spiritual care competence framework. The questionnaire consists of 6 core domains: assessment and implementation of spiritual care, professionalization and improving the quality of spiritual care, personal support and patient counseling, referral to professionals, attitude toward the patient’s spirituality, and communication. The questionnaire has been translated, revised, and applied by researchers in China (Qi et al. Reference Qi, Yan and Mao2019; Wei et al. Reference Wei, Liu and Chen2017; Yan et al. Reference Yan, Bian and Zhang2016). However, it is only applicable to nurses – not the volunteers investigated in this study. Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Qiu and Fan2016; Reference Chen, Qiu and Zhang2017) developed the Spiritual Care Competence Scale based on the scale mentioned above. This scale is applicable to volunteers and consists of 3 core domains: basic knowledge, attitude, and professional skills. To better adapt it to the Chinese population, the scale was revised based on the language environment in mainland China. This scale consists of 18 items and employs a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Total scores range from 18 to 90, with higher scores indicating higher competence levels.

Attitude toward palliative care

The measurement scale for attitude toward palliative care was developed based on the Attitudes Toward Care of the Dying Scale developed by Frommelt (Reference Frommelt2003) and the attitude questionnaire developed by Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Hu and Chiu2005). The scale contains 20 items, consisting of 4 core domains (facing advanced patients, improving quality of life, preparing for death, and obstacles to palliative care). The scale employs a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Total scores range from 20 to 100, with higher scores indicating a more positive attitude.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with IBM SPSS 23.0. Continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. A multiple linear regression analysis, an ANOVA, and a t-test were used to identify the factors affecting volunteers’ spiritual care competence. Meanwhile, spearman’s correlation was used to determine the relationship between spiritual care competence and attitude toward palliative care. p-Values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

Participants characteristics are shown in Table 1. Among our 385 participants, 77.7% (n = 299) were women. The mean age was 29.04 ± 12.82. Meanwhile, 58.2% (224) were non-religious, 70.4% (271) were unmarried, 211 (54.8%) were college students, 265 (68.8%) did not have experience in caring for terminally ill patients or relatives, 243 (63.1%) had not been exposed to knowledge about palliative care, and 327 (84.9%) had not received any training related to palliative care.

Table 1. Participant characteristics (N = 385)

Spiritual care competence

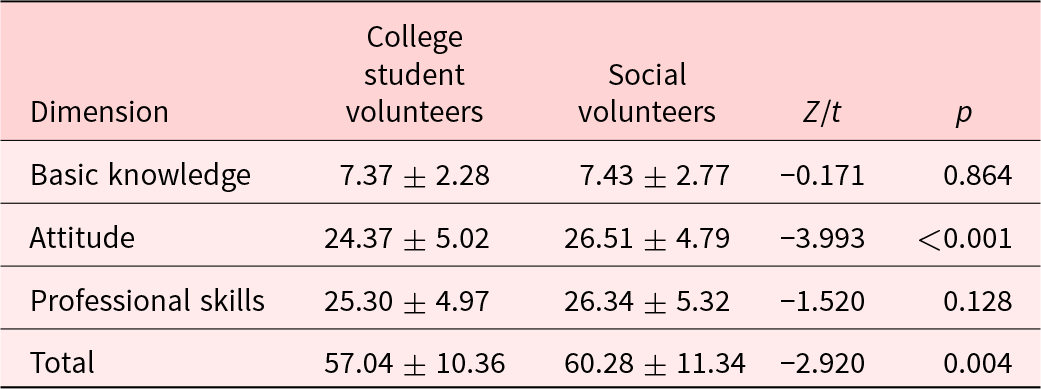

Table 2 shows participants’ levels of spiritual care. The total score was 58.50 ± 10.92. Spiritual care competence was significantly higher among social volunteers (60.28 ± 11.34) than among college student volunteers (57.04 ± 10.36). A significant difference was observed from the dimension of attitude but not basic knowledge and professional skills.

Table 2. Levels of spiritual care competence

Factors affecting volunteers’ spiritual care competence

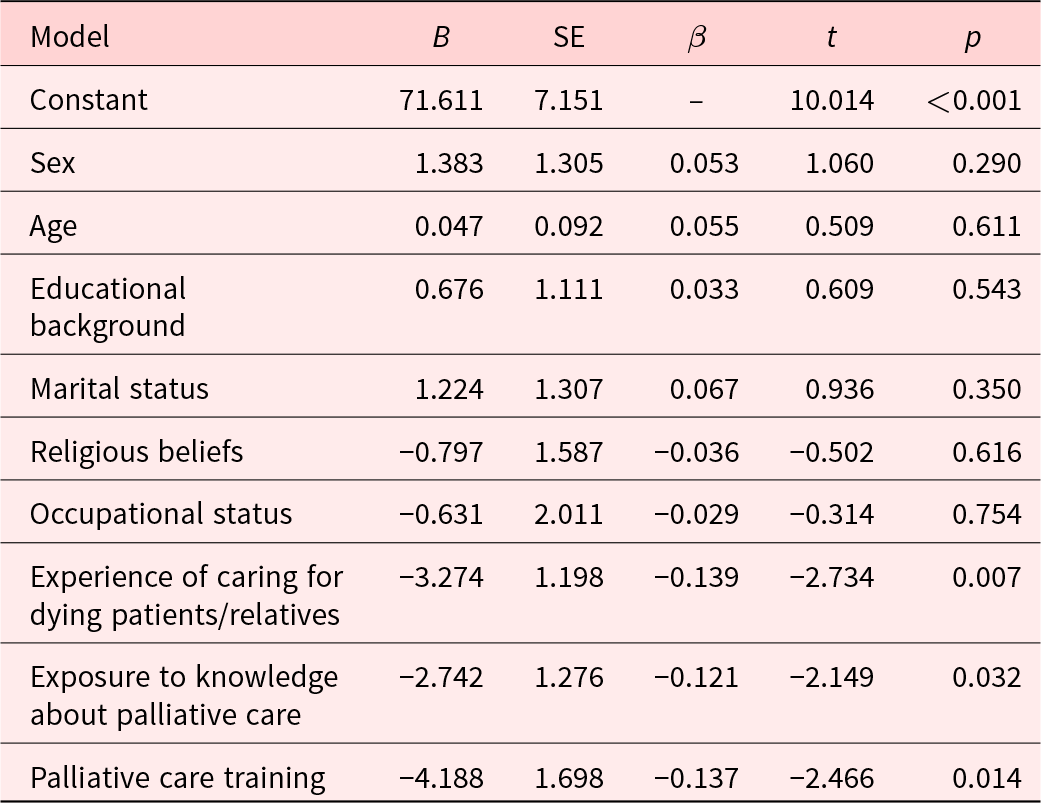

Table 3 shows the results of the univariate analysis, and Table 4 shows the results of the multiple linear regression analysis. According to the results of univariate analysis, age, educational background, marital status, religious beliefs, occupational status, and relevant training and practical experience were significantly associated with volunteers’ spiritual care competence. The multiple linear regression model fit the data well (F = 5.427, p < 0.001). Notably, relevant training and practical experience and exposure to knowledge about palliative care were associated with volunteers’ spiritual care competence; this finding is consistent with the result of the univariate analysis.

Table 3. Results of the univariate analysis of associated factors of volunteers’ spiritual care competence

Table 4. Results of the multiple linear regression analysis of associated factors of volunteers’ spiritual care competence

Attitude toward palliative care

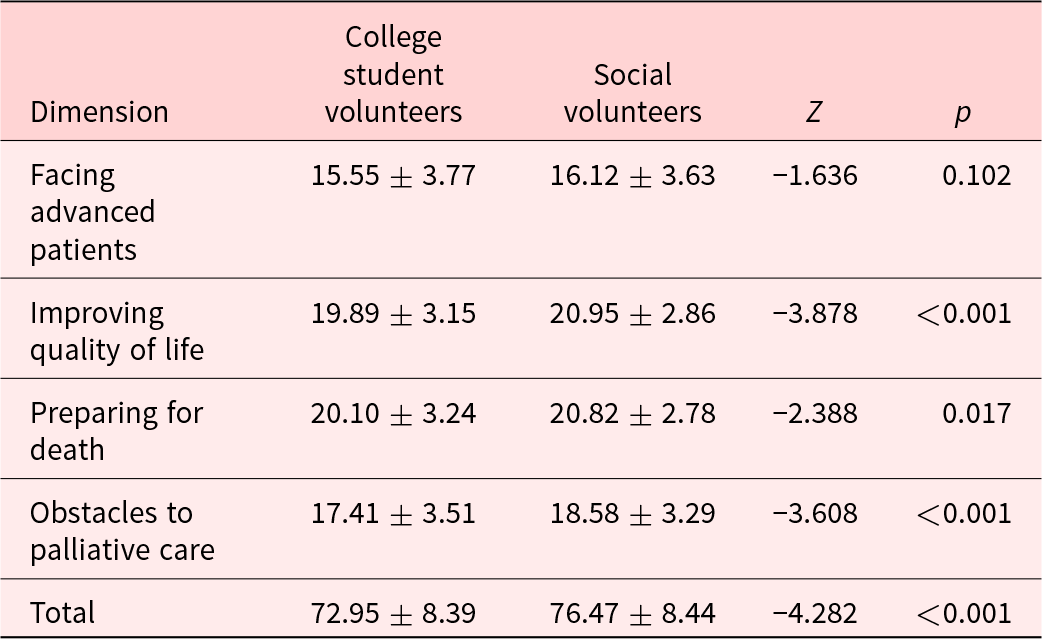

Table 5 shows the volunteers’ attitudes toward palliative care. The total attitude score was 74.54 ± 8.58 (range: 56–100). Attitudes toward palliative care were significantly higher among social volunteers (76.47 ± 8.44) than among college student volunteers (72.95 ± 8.39). This significant difference was found in the domains of improving quality of life, preparing for death, and obstacles to palliative care but not in facing advance patients.

Table 5. Levels of attitude toward palliative care

Relationship between spiritual care competence and attitude toward palliative care

A significant correlation was found between spiritual care competence and attitude toward palliative care among volunteers (r = 0.494, p = < 0.001), indicating that spiritual care competence is positively correlated with attitude toward palliative care.

Discussion

Volunteers’ spiritual care competence

This study found that volunteers’ mean scores for spiritual care competence were not high and that their overall competence needs to be improved. Currently, there are approximately 1,029 palliative care volunteers in China (National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China 2021) and the development of palliative care volunteers remains in its infancy (Ding et al. Reference Ding, Huang and Wang2021). This study surveyed prospective and potential volunteers in organizations geared to provide palliative care services. We found that volunteers from such specialized organizations – let alone those in other voluntary organizations – did not have significant knowledge and experience in the field. In fact, volunteers’ engagement in practical work was significantly constrained by their lack of knowledge and training at this stage of their development. At the same time, palliative care institutions do not effectively coordinate their volunteer education, training, and usage with voluntary organizations. The current level of volunteers’ spiritual care is not high, which may be related to their lack of knowledge and resources. Knowledge of death and palliative care and spiritual care resources had the lowest scores of all items. It is notable that spiritual care was introduced relatively late in China and that, although the importance of spirituality has been raised at the national level, relevant policies are still lacking; indeed, China does not yet have a unified concept of spirituality (Li et al. Reference Li, Lv and Zhang2021). Additionally, studies on end-of-life spiritual care in China have not been widely undertaken Nevertheless, hospitals and nursing institutions still sometimes offer spiritual palliative care. According to a research by Kichenadasse et al. (Reference Kichenadasse, Sweet and Harrington2017), most medical staff have been exposed to patients’ spiritual needs, but only 45% felt they were able to satisfy these needs. It is also notable that there is a lack of unified educational content on palliative care – let alone spiritual care – in China and that the nation does not have any planning and supervisory standards for spiritual care. Although volunteers may be passionate about palliative care, they do not have significant professional knowledge or strong understandings of the concept of spiritual care. Thus, there is an urgent need to delineate “spirituality” and develop systematic training programs geared to improve palliative care volunteers’ spiritual care competence.

This study found that the level of spiritual care competence was significantly higher among social volunteers than among college students volunteers; this result is consistent with this study’s other finding that age, marital status, and religious beliefs influence spiritual care competence. Social volunteers are relatively older and have richer experiences in caring and communication. Along these lines, they are inclined to have deeper understandings of life. Moreover, 80% of the social volunteers in this study were religious, which may partly explain these results. More specifically, Fu (Reference Fu2016) found that religion can be regarded as a spiritual resource; accordingly, the religious context can be introduced into palliative care by variable spiritual care strategies to provide a spiritual fulcrum for people who are dying and ease any feelings of vulnerability. Religious people usually hold a known belief about death, which helps eliminate a fear of the “unknown” associated with death (Sun et al. Reference Sun, Deng and Jiang2019). Therefore, it is important to recognize and emphasize the value of social volunteers and increase public awareness of palliative care in diverse ways to attract and recruit more volunteers.

Factors affecting volunteers’ spiritual care competence

The results of the univariate analysis showed that age, educational background, marital status, and religious beliefs influenced volunteers’ spiritual care competence. Specifically, an older age, a higher level of education, being divorced or widowed, and being religious correlated with a higher level of spiritual care competence. The result of the multiple linear regression analysis showed that relative practical experience, education, and training were significantly associated with spiritual care competence. Caring for patients at the end of life is also a process of self-learning and growth; for example, Jiao et al. (Reference Jiao, Hu and Zhang2020) investigated 80 nurses and found that their spiritual health and spiritual care awareness significantly improved after they completed systematic spiritual care training. Therefore, exposing clinical nurses to spiritual care courses or training may greatly improve their understandings of spiritual care, their sense of how to deliver it, and their ability to evaluate its effects. Volunteers who have been exposed to palliative care knowledge and received education and training have better understandings of the concept and of the significance of palliative care. Such experience can help them develop a correct view of life and death, eliminate the fear of death, more calmly treat dying patients, and deliver better palliative spiritual care services. Spiritual care education and training also strengthen the caregiver’s sense of responsibility to provide spiritual care, which enhances their spiritual care competence. Zhang (Reference Zhang2020) found that systematic spiritual care training significantly improved cognition, competence, and attitude toward palliative care among nurses in an oncology department in China. Spiritual care cognition is positively correlated with spiritual care competence (Shi et al. Reference Shi, Zhao and Hu2020). Volunteers urgently need to be trained in the content and methods of spiritual care (Jing et al. Reference Jing, Li and Shu2020) – it is necessary to focus on education for spiritual care cognition and develop a training and evaluation system designed to improve volunteers’ spiritual care competence.

There are abundant spiritual resources in Chinese native culture, such as the harmonious thought of the unity of man and nature, the Confucian philosophy of life, Zhuangzi’s realm of inner sanctity, and meditation. By combining Chinese and western philosophical concepts, theoretical knowledge of spiritual care suitable for Chinese people can be developed to guide the creation of a spiritual care training system. In 2007, Hunan Cancer Hospital launched the first clinical spiritual care program in mainland China. Twenty-six volunteers, mainly clinical nurses, became the first group of registered members based on expert recommendations and interviews. In 2009, 24 clinical spiritual care teachers graduated from Hunan Cancer Hospital (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Chen and Tang2012). During this period, international regions and Taiwan introduced spiritual care training. For example, Chang Gung Hospital arranged spiritual nurses who provide death education and spiritual care to dying patients to improve their quality of life (Yu Reference Yu2012). Shanghai has also started to explore spiritual care training for palliative care staff by bringing in teachers from Taiwan. In the context of the extensive implementation of pilot reforms to palliative care in China, a variety of pedagogies, such as classroom education and continued training, should be designed and implemented to strengthen awareness of palliative and spiritual care. Meanwhile, medical college faculty members should provide a range of life education and palliative care courses. Additionally, spiritual care training teachers and curricular systems should be developed to carry out the continuing education program for palliative care services and improve spiritual care competence to systematically improve the quality of palliative care, which will enhance the value and meaning of survival among dying patients and help them realize physical, spiritual, and social peace.

The relationship between spiritual care competence and attitude toward palliative care among volunteers

This study showed that the attitude toward palliative care was positively correlated with spiritual care competence (p < 0.001), indicating that volunteers who held a positive attitude toward palliative care had a higher level of spiritual care competence. The reason for this relationship may be that volunteers with positive attitudes toward palliative care are more passionate about caring for people who are dying and thus may be more likely to take the initiative to learn about their patients’ spiritual needs so that they can more easily address them. In addition, volunteers holding positive attitudes toward palliative care may also have positive attitudes toward death, which may help them understand the spiritual needs of their patients and demonstrate a positive view of life and death while carrying out palliative care (Li et al. Reference Li, Lv and Zhang2021). Consequently, it is necessary to attach importance to volunteers’ attitudes toward palliative care and to create standards and training systems to improve volunteers’ spiritual care competence.

Conclusion

This study revealed that palliative care volunteers in Shanghai did not have a high level of spiritual care competence. Statistically significant correlations were found between spiritual care competence and the following variables: age, educational background, marital status, religious beliefs, occupational status, and relevant training and practical experience. Meanwhile, we found that spiritual care competence positively correlated with attitude toward palliative care. Education and training programs should be developed to improve spiritual care competence and attitude toward palliative care among volunteers. Additionally, further studies are needed to assess volunteers’ spiritual care competence in other regions and at the national level.

Limitations

We obtained our sample of volunteers from Shanghai using a convenience sampling method; therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to volunteers across China. In addition, due to the uneven distribution of participant characteristics across the sample, the results of the multiple linear regression are not sufficient to detect all influencing factors.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the volunteers who participated in our study. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Author contributions

Limei Jing and Hui Wang contributed equally and should be considered co-senior authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.