A Note from the Series Editors

Sadly, Rob Hume passed away, after a short and shockingly sudden illness, as this volume was going into production. Typically of his altruism and generosity of spirit, he had been working on a book about those he considered the leading critics of the twentieth and early twenty-first century. He surely belonged in such a book himself. No one has done more to reshape our understanding and appreciation of Restoration and Eighteenth-century theater, and more recently, of opera, than Rob. A committed historicist who believed that information and data are more useful to others than ideology and will certainly outlast it, he charmed librarians into finding all-but forgotten archives hidden in unopened cardboard boxes in library basements. He will be remembered for his brilliant and prolific scholarship – but also through the many lives he touched. Rob mentored, professionalized and supported generations of women students and women faculty. Many will mourn the loss with him of a true friend – a man of integrity and principle, of ruthless honesty and unbending loyalty, who cared, and could be relied upon for good advice and practical help in any emergency. It is an honor to have his work in our series, and we hope that he would have approved of the editing, copy-editing and formatting decisions we have had to make without him.

Eve Tavor Bannet, November 2023

Introduction

So far as I am aware, no one has ever systematically surveyed and analyzed paratext in the new plays that were professionally performed and then published in London between 1660 and 1700.Footnote 1 My subject is almost entirely first editions of plays newly written and performed after 1660, including the many plays that are substantive adaptations of pre-1642 drama. (George Buckingham’s The Chances performed by 1664 and published in 1682, adapting John Fletcher’s play of that title, performed 1615–25? and published in 1647 is a good example.) By my reckoning, such plays total some 377. The number cannot be exactly determined because in a few cases we do not know definitively that a published play was performed, and how much alteration is required to make a play “new” cannot readily be quantified. The title page is a given. It may or may not supply a subtitle and a generic descriptor. Usually, but not invariably, the title page names the playwright and states where or by whom the play was performed. After 1670, the Dramatis Personae often (though not always) records the name of the actor of each part. Beyond that, dedications, prefaces, imprimatur (government permission to publish, when mandated by law), identification of genre, prologue and epilogue, and specified “location” of the action (e.g., “London”) are possibilities. “Agency” is often impossible to assign, and might be owing to playwright, bookseller, or printer – a problem I have not attempted to address.Footnote 2 And I have treated publishers’ advertisements as outside the remit of this Element.

Paratext is a rich but not fully exploited resource for scholarship, and it will repay investigation. I need to make explicit up front that I am addressing two radically distinct audiences and must beg the indulgence of the reader when I seem to be bogged in bibliographic trivia (e.g., licensing dates), or alternatively soaring aloft to supply a 40,000-foot overview of generic evolution largely unconnected to evidence grounded in the physical book (which has disconcerted some bibliographers). The quantitative description and analysis of twelve kinds of paratext in 377 plays dated 1660–1700 ought, I believe, to be of assistance to bibliographers and editors dealing with those plays, but also to scholars and critics whose concern is with the evolution of English drama across two centuries circa 1600 to circa 1800. Paratext has a surprising amount to tell us about what playwrights attempted to do and how audiences responded. Letter and diary responses to plays are thin on the ground and mostly rather subjective and slapdash. Newspaper and magazine reviews are largely nonexistent until the last third of the eighteenth century.

This Element had its origin in notes about norms and departures from those norms 1670–89 made for the benefit of the editors of plays in The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Aphra Behn (now starting to come into print). My original draft dealt exclusively with the last four decades of the seventeenth century, but readers kept asking how the plays of those decades “fit” with pre-1642 drama and led into eighteenth-century developments. The answers I have come up with seem to me usefully provocative of thought. I grant the unconventional nature of the enterprise. But beyond providing the late seventeenth-century particulars, I wish to demonstrate how paratext helps us (1) to understand the multifarious variety of English drama at any point in time, and (2) to trace the larger patterns of generic evolution across two centuries.

The Twelve Paratextual Elements

The twelve principal paratextual elements that I have identified and systematically surveyed across the 377 plays dated 1660–1700 are:

1. Authorial credit, usually on the title page (which is almost always dated by year), but occasionally only in a signed dedication. Anonymous publication dwindled fast.

2. Generic designation on the title page, usually following title (and frequently subtitle).Footnote 3

3. Designation of auspices in a statement reporting performance by a particular company and/or at a specific theatre.

4. A government license authorizing publication, usually printed on the title page, when such licensing was mandated by law (1662–79 and 1685–95), but often omitted, the law notwithstanding.

5. A dedication (often with an extensive and sometimes gushy tribute).

6. Prefaces of various sorts, usually but not always by the playwright.

7. a.-b.-c. A list of the characters in the play. These come in three distinct forms, discussed in what follows.

8. The names of the performers in the first production. Exceedingly rare before 1642, and after the Restoration almost unknown until 1668, but after that identification of at least the principal actors and actresses rapidly became a standard though not invariable feature of play quartos.

9. A statement about the location of the action (abbreviated “Loc” in the data table), often placed at the end of the Dramatis Personae list, which, for example, in Congreve’s The Old Batchelour, ends simply “The Scene, LONDON.”

10. A prologue and epilogue written for the first production.

The evidentiary basis of this Element is the massive table that constitutes Appendix B (“Twelve Varieties of Paratext in 377 New English Printed Plays, 1660–1700”), in which I have attempted to record analytically the varieties of paratext to be found in every new play known to have been professionally performed and subsequently published in London between the reopening of the theatres in 1660 and 1700. The terminal date is somewhat arbitrary. Licensing of publication came to an end in May 1695, and the rest of the decade demonstrates considerable stability in publication practices. I will devote the remainder of this Element to analysis of the facts, figures, changes, and variety of what the data table can tell us. Much of this material is often ignored and omitted even in modern critical editions and almost always by editors of student texts and anthologies. By way of conclusion, I will briefly suggest that much of the generic evolution that paratext helps us trace in the seventeenth century is in fact largely undone in the course of the eighteenth century – a reversal that can be pretty decisively attributed to the Licensing Act of 1737.

The frequency of appearance of the twelve common types of paratext is summarized for each of the last four decades of the seventeenth century in Appendix A: “Cumulative Statistics by Decade and in Toto.” Here I must issue a caution about the seeming exactitude of the figures. The features to be found in any particular copy of a seventeenth-century edition can easily be tallied. The playwright’s name is on the title page, or it is not. The quarto contains a prologue and an epilogue, or it does not. Unfortunately, not all copies are identical. For example, three states of the first edition of Aphra Behn’s The Rover (1677) exist, all three printed for John Amery, with the author’s name on only one of them (Folger copy B1763b). A second example is the two states of the title page of George Digby’s Elvira, both illustrated on Early English Books Online (EEBO). One state, ESTC R232462 (Wing 4764), has no license and an imprint with the unusual spelling for the publisher as “Henry Broom” (illustrated by the Newberry copy on EEBO). The other, ESTC R9341 (Wing B4764A), wrongly calling it “Anr Edn,” has the license by Estrange dated 15 May 1667 and the correct spelling “Henry Brome” (reproduced on EEBO from a Huntington copy with frontispiece portrait of Digby). Allardyce Nicoll and The London Stage report only that with a licensing date.Footnote 4 Such minor but sometimes significant variances are a fact of life and must be allowed for. A third example is Henry Cary’s (?) The Mariage Night (pub. 1664), where the license appears at the end of the prelims. I could easily have failed to spot a license that appeared in an unusual location – or the EEBO copy may lack a license present in other copies.

The examination of the primary evidence has been carefully done and checked, but the evidence is not totally uniform, and judgment sometimes comes into play. Consider the issue of “characters described” in a Dramatis Personae list. This important component of paratext varies greatly from playwright to playwright, and it changes over time. I have tried to indicate variation by employing delimiters (e.g., “Some” and “A bit”). I have counted these instances as “Yes” if the first edition “describes” at least some of the characters for the reader – but another scholar might exclude a very incomplete case. I have dithered over some generic categorizations. And I have agonized over some attributions, frequently resorting to “(?)” when reporting long-standing attributions for which I consider the evidence inadequate. I report what the first edition says or fails to say, but where a later attribution seems definitive, I record that [in brackets] for the reader’s convenience, while noting that it is lacking in the first edition. I have also had to report some half a dozen cases in which standard and long-unquestioned attributions appear to me to have no satisfactory basis.

Background

Most paratext was published in the prelims of late seventeenth-century play quartos, which appeared as singletons.Footnote 5 Reprints were almost always in quarto, in most cases verbatim, and comparatively infrequent.Footnote 6 In the late seventeenth century, play quartos were a standard product at a standard price (usually 1s). Following 1660, remuneration arrangements for playwrights underwent a drastic change that scholars did not fully recognize and confront until 2015.Footnote 7 Prior to 1642, playwrights generally sold their scripts outright to acting companies, ceding both performance and publication rights in perpetuity for a flat fee agreed upon by the contracting parties (though a benefit performance was sometimes part of the agreement). After 1660, remuneration for perpetual acting rights became the profit (if any) of the third night if the play lasted that long in its first run.Footnote 8 But in compensation for loss of the traditional cash-on-the-barrelhead fee for performance rights, playwrights were allowed to sell publication rights (in perpetuity) for whatever a bookseller might be willing to venture on a particular play.Footnote 9

I bring up the sale of publication rights here because it raises issues concerning the origin and content of the script to be published. In the absence of typewriters, computers, and electronic transmission, much paratext depended on the precise source, nature, and content of the handwritten manuscript delivered to the printer. Timing also needs to be taken into consideration. The gap between premiere and publication changed radically over the last four decades of the seventeenth century.Footnote 10 For many years, twentieth-century scholars followed Allardyce Nicoll in believing that the gap was a month or two. Item-by-item analysis shows, however, that in the 1660s, the gap varied but was usually something like six months to a year (and sometimes substantially longer). In the 1670s, the time lapse shrinks, falling to a norm of about three months. In the troubled time of the Popish Plot and the Exclusion Crisis, the gap becomes wildly variable. Three months remains normal, but six- and eight-month gaps are not uncommon. Around the beginning of the 1690s, the standard gap abruptly becomes about a month, or even less. A probable reason for this is regime change. The licensing law did not officially expire until 3 May 1695, but for most practical purposes, it was not really enforced after William III’s arrival on the throne in 1688. Thereafter, whether for reasons involving protection of the right to copy or the growing realization that spectators in the theatre might well prove the likeliest purchasers of the printed text, publication almost always followed closely on first performance.

After 1660, the source of the manuscript set by the printer must usually have been the playwright. If the “gap” was three months or more and the play had enjoyed whatever run it achieved, perhaps the MS prompt copy could be borrowed for use by the printer.Footnote 11 Or the author might have retained an advanced draft, personally have copied a quasi-final draft, or paid a prompter’s clerk to make another copy. At some point, someone had to assemble dedication, preface, or other prefatory matter (if such items were to be included), prologue and epilogue, and names of the actors (if added to the Dramatis Personae). Printing of text proper almost invariably begins with the B gathering.Footnote 12 Evidently, the printer often started there and could wait a while for the arrival of the paratextual material that would populate the A gathering.Footnote 13 The order in which such elements, when present, appear in the prelims varies, but I will survey them in the most common order.

Ten Varieties of Paratext and Two Subsets

Comparative statistics for each of the twelve categories, decade by decade and in toto, may be found in tabular form in Appendix A.

(1) Authorial Credit (column 1 of Appendix B). The norm was to identify the author by name, which overall occurred fully 85% of the time, usually with genre specified if not obvious from the title. The exception is the mid- and later 1680s, when identification of the playwright rises to 95%. The reason seems clear. After the union of 1682, the managers of the United Company decided that with no competition, they need bother to mount no more than three or four new plays a year.Footnote 14 Quite naturally they accepted almost nothing not written by established professional playwrights (whose names on title pages possessed value) or company insiders. In the six years 1677–82, the two companies had staged eighty-five new plays, or about fourteen per annum. In the six years 1683–8, the United Company staged just twenty-three, or about four per annum.

At the other extreme, no playwright might be named. The reasons for anonymity evidently varied. A grandee like the Duke of Buckingham probably felt that publishing was for lesser beings; there is no evidence that he had any hand in the publication of The Chances (eighteen years after its premiere) or The Rehearsal. Both appeared in print with no hint of authorial origin and little paratext beyond auspices, prologue, and epilogue.Footnote 15 Aphra Behn signed most of her plays (though not all of those extensively based on old plays), but even in the late 1690s, other women playwrights tended to be coy (e.g., She Ventures, and He Wins, “Writen by a Young Lady,” pub. 1696). Some of the plays “seen to the stage” (and thence into print) by such actors as William Mountfort and George Powell in the eighties and nineties were probably written by amateurs happy to oblige their actor friends without seeming to stoop to ungentlemanly pursuits. After the 1660s, knights and lords mostly refrained from playwriting, which had rapidly become an enterprise dominated by professionals.

Interestingly, though playbills appear to have exercised significant influence on the content of title pages, the reverse seems much less true. (Too few playbills survive from before 1700 to permit a conclusive generalization.) Main title, subtitle if any, and very often genre are duly picked up by publishers. In the 1660s, 82% of the published plays identify the author, usually on the title page. (That number fluctuates, but the overall figure for the whole forty-year period is, coincidentally, 82%.) But if Dryden is to be believed, and I think he is, never until 1699 did a playwright’s name appear on a playbill. Writing to Mrs. Steward on 4 March 1698[/9], he says: “This Day was playd a reviv’d Comedy of Mr Congreve’s calld the Double Dealer, which was never very takeing; in the play bill was printed, – Written by Mr Congreve; … the printing an Authours name, in a Play bill, is a new manner of proceeding, at least in England.”Footnote 16 One might suppose that the playwright’s name would help attract an audience, at least in the case of proven professionals, but repertory theatres tended to be pretty conservative, and the managers were extremely slow to adopt this innovation. Of course, new plays in the theatre were anonymous prior to publication except by rumor among cognoscenti, so audience members might have good associations with a successful play without knowing who wrote it. Publishers soon learned to take advantage of such knowledge. The title page of the first edition of Aphra Behn’s Sir Patient Fancy (1678), for example, declares that the play was “Written by Mrs. A. Behn, the Authour of the ROVER.” A lot of people must have seen and enjoyed that very popular play without encountering Behn’s name in connection with it. Latter-day scholars need to understand that for seventeenth-century readers of books, authorship of plays had become paramount by mid-century, but for theatregoers, that became true much more gradually over the next several decades.

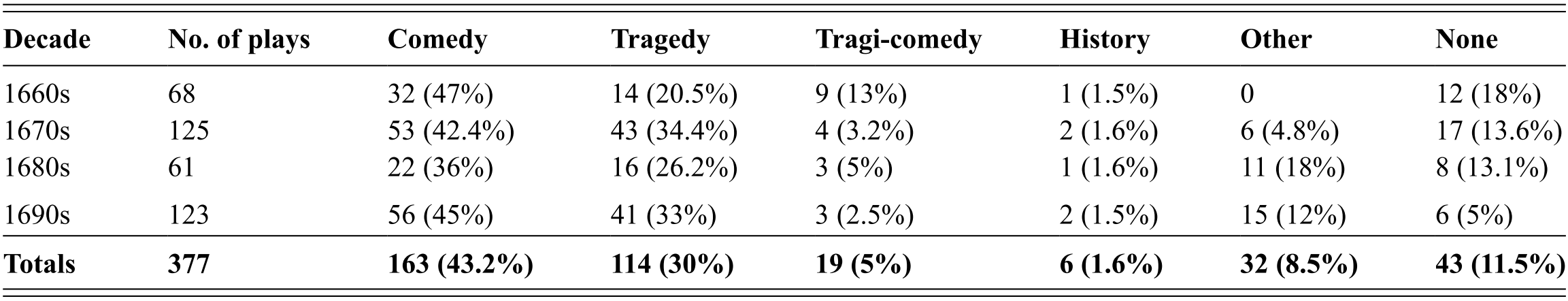

(2) Generic Designation on the Title Page, with or without attribution (reported in column 2 of Appendix B; absence indicated by *). (For an example, see Behn’s Rover, Folger copy B1763a.) This convention seems designed to assist potential readers browsing in bookshops. In this respect seventeenth-century title pages anticipate the practice found in eighteenth-century playbills and newspaper bills, which usually contain genre descriptors.Footnote 17 A genre designation would of course have been a convenience to a manager or script reader, especially in years when a theatre was doing ten or more new plays and was presumably offered substantially more than that number. Generic designations are sometimes worked into titles (which I have counted as generic identification) – for example, Nathaniel Lee’s The Tragedy of Nero (1674) or Thomas Durfey’s The Comical History of Don Quixote (1694). The proportion of genre designations is 81% in the sixties, 87% in the seventies, 89% in the eighties, and 94% in the nineties. The reasons for not specifying genre evidently vary. Sometimes the title or subtitle makes the designation supererogatory (e.g., Joseph Harris’s Love’s a Lottery, 1699, or Lee’s The Rival Queens, or the Death of Alexander the Great, 1677). In other cases, I deduce that the playwright was deliberately signaling a departure from generic norms. As instances I offer Dryden’s The Conquest of Granada (two parts, 1670–1) and Thomas Southerne’s The Disappointment: A Play (1684). For decade by decade and cumulative figures on genre descriptors, see Table 1. We can only guess who or what caused a change from state to state or edition to edition. The first state of Behn’s The Rover (1677) says merely: “The Rover. Or, The Banish’t Cavaliers.” The second state adds “A Comedy” before proceeding to “Acted at His Royal Highness the Duke’s Theatre.” The third adds: “Written by Mrs. A Behn.”

Table 1 Genre descriptors

| Decade | No. of plays | Comedy | Tragedy | Tragi-comedy | History | Other | None |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1660s | 68 | 32 (47%) | 14 (20.5%) | 9 (13%) | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | 12 (18%) |

| 1670s | 125 | 53 (42.4%) | 43 (34.4%) | 4 (3.2%) | 2 (1.6%) | 6 (4.8%) | 17 (13.6%) |

| 1680s | 61 | 22 (36%) | 16 (26.2%) | 3 (5%) | 1 (1.6%) | 11 (18%) | 8 (13.1%) |

| 1690s | 123 | 56 (45%) | 41 (33%) | 3 (2.5%) | 2 (1.5%) | 15 (12%) | 6 (5%) |

| Totals | 377 | 163 (43.2%) | 114 (30%) | 19 (5%) | 6 (1.6%) | 32 (8.5%) | 43 (11.5%) |

The 32 “Other” cases break down as follows. Farce: 8.Footnote 18 Opera: 11 (though sometimes also labeled “Tragedy”). Masque: 1. Pastoral: 3. “Play”: 6. “Novelty”: 1. Musical: 2.

(3) Designation of Auspices – a statement along the lines of “As it is Acted at the Theatre-Royal, By His Majesty’s Servants” (title page of Southerne’s Oroonoko, 1696). Presence of such a statement is indicated by †, absence by ⸸, in Appendix B, column 2. Professional performance in London was regarded as enhancing a book’s appeal, and the company/venue statement is to be found on the title page of almost every play entitled to make the claim. Of the 377 plays in the Appendix Table, 357 make such a claim on the title page (see Plates 1, 2, and 3), 17 do not, and in 3 cases, the EEBO copy is defective and fails to supply a title page. But of the 17 “No” cases, 14 precede 1670 and 11 precede the closure of the theatres on account of plague in June 1665. The scattered later cases strike me as flukes. Ravenscroft’s adaptation of Titus Andronicus was not published until more than five years after its premiere. The cast was not named, and the original prologue and epilogue were lost. The omission of the venues for Durfey’s The Campaigners and III Don Quixote was probably just due to someone’s inattention.

Clearly, by the end of the 1670s, the “auspices” statement was utterly standard. It comes, however, in a bewildering number of variants. Either company (King’s, Duke’s, Their Majesties Servants) or theatre (Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Drury Lane, Dorset Garden) might be named, or a combination thereof. Examples are “As it is Acted at The Duke’s Theatre” (Ravenscroft’s London Cuckolds), “As it is Acted by His Majesties Servants” (Crowne’s City Politiques), and “As it is Acted by Their Majesties Servants at the Queens Theatre in Dorset Garden” (Jevon’s The Devil of a Wife). Ambiguity sometimes arises in the era of the United Company (1682–94), which used both Drury Lane and Dorset Garden (though so far as we know never on the same day), but surviving evidence suggests that what was staged at Dorset Garden tended to be opera and plays requiring fancy stage machinery.

(4) Government License Authorizing Publication (“Lic” in column 8 of Appendix B). In principle and under law, licensing for publication was required for all sorts of books and pamphlets, plays included, between 10 June 1662 and March 1679, and again after the accession of James II in 1685 (in a law taking effect on 24 June 1685) until its final collapse effective with the prorogation of Parliament on 3 May 1695.Footnote 19 The license usually takes the form of a statement on the title page (occasionally elsewhere in the book) such as: “Licensed, 3 June 1676. Roger L’Estrange” (title page of the 1676 first edition of Etherege’s The Man of Mode). But by my reckoning, of the circa 230 plays in this table that ought to have borne such a license, only 80 (35%) actually do so.Footnote 20 I can offer no satisfactory explanation.

Plays were also licensed for performance, an entirely separate matter. We know quite a lot about the process (though less than we would like to in some respects). Sir Henry Herbert was the licenser for performance until his death in 1673.Footnote 21 He was followed by Thomas Killigrew, who gave place to his son Charles in 1677. Little direct evidence or testimony has survived, but so far as we know, every new play performed by the patent companies in London between 1661 and 1715 was duly vetted by the Master of the Revels.Footnote 22 Very few manuscripts survive bearing the censor’s objections and deletions. The fee was two pounds per script, which does not sound like much until one remembers that this amounted to one-twentieth of the average annual household income in England at the time.Footnote 23

Much less is known about the fees, modus operandi, and results of Sir Roger L’Estrange and other licensers for print. A pair of striking examples will illustrate this point. In 1682, Shadwell published The Lancashire Witches with extensive passages printed in italics to identify matter not permitted by the Master of the Revels in performance. Eighteen years later, Colley Cibber published the complete text of The Tragical History of King Richard III, including the entirety of Act I, which had been deleted from the performance text by the Master of the Revels, who claimed it might call for sympathy for James II, exiled since the Revolution of 1688.Footnote 24 I am aware of no contemporary remarks on the oddity of this discrepancy concerning these or other instances. What could not be said on stage could be put in print absolutely legally for all to ponder, accompanied by the aggrieved playwright’s bitter complaints.

(5) A Dedication (indicated by “Ded” in column 8 of Appendix B). This was in no sense obligatory, but quickly became a feature of a large number of plays. They are least common in the 1660s (only 29% versus 61% for the four decades as a whole). The reason seems obvious: a fulsome dedication was a de facto appeal for a pecuniary reward, but in the 1660s, many of the new plays were written by lords, knights, and fine gentlemen aspiring for reputation, not income. Of the sixty-eight new plays staged in that decade, eleven were written or coauthored by Dryden and Shadwell (not counting Dryden’s contribution to the Tempest adaptation of 1667), but they were the only playwrights we regard as professional dramatists, and they were just starting to learn their trade. Dedications are immensely varied. Many merely express sycophancy or personal friendship, but some are serious critical or aesthetic justifications for the work that follows. Boasting of success is common, but so is lamentation of failure in the theatre. Reasoned explanations of the playwrights’ choices are fairly rare, but sometimes helpful. Dryden’s dedications and prefatory matter are exceptionally rich in substantive commentary.Footnote 25

(6) Critical Apparatus. The line between “dedications” and “prefaces” or related notes “To the Reader” and the like is often blurry or even nonexistent. Their presence in a play quarto is recorded under various descriptors in column 8 of Appendix B.Footnote 26 Looking at some of Dryden’s efforts in these realms, I might point to “A Defence of an Essay of Dramatique Poesie, Being an Answer to the Preface of [Sir Robert Howard’s] The Great Favourite, or the Duke of Lerma,” which prefaced The Indian Emperour (1667); “Of Heroique Playes,” preface to The Conquest of Granada (1672); the preface to Troilus and Cressida (1679), which contains an extensive essay on “The Grounds of Criticism in Tragedy,” running together to some 10,000 words of fairly technical critical argumentation; and the preface to An Evening’s Love (1671), which offers some 4,000 words of very detailed analysis of what “comedy” can be and should try to do. Twentieth- and twenty-first-century scholars have made little (and often condescending) use of late seventeenth-century criticism, which exists largely as prefatorial paratext. Some of it is superficial or self-serving, but there is a lot of meaty, substantive information about what the playwrights were attempting to achieve.Footnote 27

(7.a.b.c.) Three Varieties of Lists of the Characters’ Names. A “Dramatis Personae” list had long been a standard feature of pre-1642 plays and remained the norm for new plays in the 1660s. Throughout the four decades at issue, 98% of new plays carried a list of the Dramatis Personae, often under that designation.Footnote 28 Unsurprisingly, the lowest percentage was in the 1660s – still a very substantial 96% (sixty-five out of sixty-eight plays). The key question was what information would be conveyed beyond a simple list of names. The three basic variants are:

a. A list of names of the characters (e.g., Bayes in Buckingham’s Rehearsal), with presence (Yes) or absence (No) noted in column 4 of Appendix B.

b. A list of the characters’ names, plus explanation of their “connections” (son of, wife of, daughter of, his friend, the Queen’s Eunuch, etc.), with presence (Yes) or absence (No) of such explanation noted in column 5 of Appendix B, often with the names of the performers specified.

c. A list of names, plus connections, plus “characterization” with presence (Yes) or absence (No) noted in column 4 of Appendix B – for example, Heartwell in Congeve’s The Old Batchelour, “a surly old Batchelour, pretending to slight Women; secretly in Love with Silvia.” These sometimes extend to considerable detail, often, but by no means always, with the names of the performers added.Footnote 29

Explanation of the connections amongst the characters was very much the norm: overall 85%. “Characterization” in the Dramatis Personae list was far less common. By my reckoning it was a mere 26% (eighteen of sixty-eight cases) in the 1660s, and never topped 50% in the seventeenth century. I offer the speculation that the increase in characterization reflects growing concern with readers, especially readers outside of London who might never see the play. Characterizations are almost certainly not aimed at the actors. Playwrights usually helped cast the play, they read the script aloud at the start of rehearsals, and they often assisted in direction.Footnote 30 An actor who wanted explanation of his or her character could usually ask the playwright.

(8) Listing the Names of the Performers against Their Roles, with presence (Yes) or absence (No) noted in column 7 of Appendix B. A fourth variant on the Dramatis Personae page was to start with any of the first three, adding the name of the performer of each role (or at least the major roles).Footnote 31 The first post-1660 plays published with the actors’ names were Sir Robert Stapylton’s The Slighted Maid and The Step-Mother, both performed in 1663 and published in 1663 and 1664, respectively. The innovation evidently attracted no notice. But in 1668, three plays were published with cast specified. They were Orrery’s History of Henry the Fifth (performed in 1664), Orrery’s Mustapha (performed in 1665), and Dryden’s Secret-Love (performed in 1667). For the 1660s, the figures as a whole are 20 of 68 plays published with the names of the actors (29%), but by 1670, naming the performers had become more common than not. The figures for the seventies soared to 79 of 125 (63%), and they reached 81% (100 of 123) in the nineties.

I cannot recall any scholarly commentary on lack of printed casts in play quartos for most of the 1660s. I confess that until now I had never thought much about this rather significant gap, or the rapid arrival at a new norm at the end of that decade. The reason for this obliviousness, I conjecture, is that we possess fairly full casts for about forty plays in the 1660s because John Downes printed them in his Roscius Anglicanus (1708).Footnote 32 Fifteen of those casts were for King’s Company plays (old and new), the rest mostly post-1660 new plays staged by the Duke’s Company, in which Downes served as prompter. Adding Pepys’s copious commentary on performers between 1660 and the cessation of his diary in 1669, we can legitimately feel that we have a decent grip on the “lines” and fortes of many early Restoration performers. Pepys’s massive diary (nine volumes of text plus a volume of commentary and a volume comprising an index) is much quoted but in fact remains seriously underutilized as a primary source to be mined by theatre historians.Footnote 33

Exactly what precipitated the sudden alteration in the norms of play publication we can only guess, but how the change came about is easy to explain. Stapylton’s The Slighted Maid was “Printed for Thomas Dring” in 1663, and his The Step-Mother was “Printed by J. Streater; And are to be sold by Timothy Twyford” in 1664. I deduce that the innovation was brought about by Stapylton (perhaps wishing to curry favor with the actors?), even if it had no immediate impact. But if we look at the three plays that appeared in 1668 with printed casts, we find a common factor, or perhaps two. In all three cases, the book was “Printed for H. Herringman,” who dominated play publication in the first fifteen years after the Restoration. Herringman was a trend setter and other publishers followed his lead. The fact that two of the plays were by Orrery may well be significant. Whether the earl was being gracious or politic we can only guess, but he seems likelier to have suggested adopting Stapylton’s innovation than the still relatively junior Dryden.

I cannot overstress the importance of naming the performers for the modern interpreter of these plays. Playwrights very often wrote with particular performers in mind. To cast the manly and heroic Charles Hart as Horner in Wycherley’s The Country-Wife does not suggest that fornicator was being harshly satirized (as many modern critics have believed). To cast the large, fierce, intimidating John Verbruggen as Mr. Sullen in Farquhar’s The Beaux Stratagem makes his physical threats to his wife upsetting, not comic (Verbruggen played Iago to Betterton’s Othello). Casting one of the company’s clowns in that part would have produced a radically different effect. The failure of almost all major modern editions to annotate cast lists when present and to analyze their implications for interpretation is shocking.Footnote 34 I see the rapid growth in identification of performers that started in 1668 as clear evidence that the relatively small, increasingly knowledgeable Restoration audience was able to imagine the named performers in a play, even if they had not yet attended a performance (and perhaps never would).

(9) Location for the Action Specified (e.g., “London,” or “Bohemia,” or “Dover”). If present, this labeling is usually found at the end of the Dramatis Personae, though specific changes of setting within the play are customarily signaled act by act or scene by scene as appropriate. A general setting (“Location” as I am terming it) is specified in roughly three-quarters of late seventeenth-century plays, a practice consistent throughout the period. If made explicit, “Loc” appears in column 8 of Appendix B.

(10) Prologue and Epilogue. Performances of new plays were invariably accompanied during the initial run by a purpose-written prologue and epilogue, delivered by a popular actor or actress. They were sometimes separately printed for sale at the time of premiere and were almost always included in the first and subsequent editions.Footnote 35 If present in the first edition, “P/Ep” appears in column 8 of Appendix B. They contain often valuable information about the dates of the plays, their content and aims, current events, and audience attitudes, though topicality can make them difficult to decipher or annotate. Fortunately, the monumental seven-volume Danchin edition collects them all, offers dating information when necessary, and supplies annotation that greatly assists the reader in navigating his or her way through what is often a blizzard of topicalities and local references.Footnote 36 Anyone using material from prologues or epilogues needs to consult his edition.

Lack of prologue and epilogue in a play quarto is highly unusual for a professionally performed play. Behn’s (?) The Revenge (1680), an adaptation of Marston’s The Dutch Courtesan (1605?), is a rare instance. Behn apologizes for the lack of a prologue in her The Dutch Lover (1673), saying in her address to the “Reader” that it is “by misfortune lost.” Publishers who found themselves short of this bit of paratext sometimes resorted to the expedient of repurposing text filched from an old and probably mostly forgotten play. Diana Solomon has kindly pointed out some examples to me. The second, unspoken prologue to [Duffett’s?] The Amorous Old Woman (1674) was reprinted as the prologue to Durfey’s The Fool Turn’d Critick (1676) and then again as the prologue for Orrery’s Mr. Anthony (1669 but not published until 1690). And the epilogue to Durfey’s The Fool Turn’d Critick (1676) reappears as the prologue to his own Injur’d Princess in 1682. The epilogue to Lee’s Lucius Junius Brutus (1680) turns up as the epilogue to Mrs Pix’s The Czar of Muscovy (1701). Elaine Hobby suggests that I note the slightly dizzying case of Aphra Behn’s posthumous The Widdow Ranter (perf. 1689; pub. 1690). Dryden wrote the prologue and epilogue used in performance, which were published separately by Tonson at the time of performance. But when Knapton published the play in quarto in 1690, the prologue supplied was what Dryden wrote for Shadwell’s A True Widow (1678), of which Knapton had published the second edition in 1689, and the epilogue was one lifted from the Covent Garden Drollery (1672). “Gallants you have so long been absent hence” was apparently written for a revival circa 1671–2 of Fletcher and Massinger’s The Double Marriage, very possibly by Behn, and used by Behn as the prologue for her adaptation Abdelazer in 1676 (pub. 1677).Footnote 37 Danchin makes the plausible suggestion that the substitution of old work for what Dryden had supplied for performance was the result of disagreement over copyright and fee between Tonson and Knapton.

One occasionally encounters oddities with some interest and significance. A good example is the “Postscript” added to Part 1 of Aphra Behn’s The Rover in which some copies have the added phrase “especially of our sex” although the Prologue refers to the author as “him.”

Observations, Reflections, and Questions

Pondering the implications of the figures tabulated in Appendix A (drawn from the raw data in Appendix B), I want to offer some comments and questions in several realms.

I. Continuity and Change. Most drama scholars (especially “Renaissance” drama scholars) long assumed that the closure of the London theatres in 1642 created a radical break, and that when theatres were reopened in late 1660, a brave new world (or perhaps merely a degraded one) had begun. This view was seriously challenged as long ago as 1936 in an important but mostly disregarded book by Alfred Harbage.Footnote 38 He maintained that between 1626 and 1669, English drama evolved in an essentially unbroken continuum that included the Interregnum. Studies of post-1660 drama tended to jump quickly past the 1660s in order to concentrate on major plays by Wycherley, Etherege, Dryden, and Shadwell in the 1670s. Allardyce Nicoll’s rather superficial and mechanical six-volume A History of English Drama 1660–1900 aside, accounts of “Restoration” drama (mostly comedy) published in the 1950s and 1960s dealt with no more than about fifteen plays in toto.Footnote 39 When scholars finally got around to systematic analysis of genre evolution that took account of all of the plays performed in the London patent theatres, they found that the plays of the 1670s are very different in many respects from those of the 1660s.Footnote 40 The number of new plays professionally performed in London between 1660 and 1710 is circa 500 (counting both published and lost), and there is quite a lot of variety and change if one looks beyond the tiny canon celebrated by mid-twentieth-century critics.

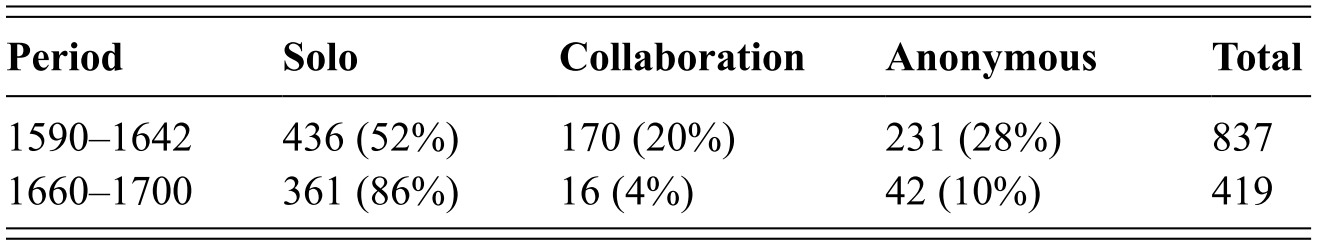

Let me ask a blunt question: what does paratextual evidence have to tell us, if anything, about continuity or disjunction between 1642 and the 1660s? We may usefully inquire into the degree of solo authorship, collaboration, and anonymityin the early and later seventeenth century. Granting that what appears to be “solo” authorship may conceal collaboration (for example, the Duke of Newcastle did not thank his collaborators in print, but anecdotal evidence suggests that he received substantial professional help with his plays and compensated his helpers generously), and that anonymity may conceal collaboration, the figures available to us seem interesting.Footnote 41 I take the figures from Paulina Kewes’s admirable account of the changing nature of playwriting in the course of the late seventeenth century.Footnote 42 Let us first consider two periods in their entirety, 1590–1642 versus 1660–1700.

Table 2 Solo-authored, collaborative, and anonymous plays, 1590–1642 versus 1660–1700

| Period | Solo | Collaboration | Anonymous | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1590–1642 | 436 (52%) | 170 (20%) | 231 (28%) | 837 |

| 1660–1700 | 361 (86%) | 16 (4%) | 42 (10%) | 419 |

Table 3 Solo-authored, collaborative, and anonymous plays, 1631–42 versus 1660–70

| Period | Solo | Collaboration | Anonymous | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1631–42 | 127 (83.5%) | 9 (6%) | 16 (10.5%) | 152 |

| 1660–70 | 79 (82%) | 8 (8.5%) | 9 (9.5%) | 96Footnote 43 |

The much smaller number of plays post 1660 is attributable to the Killigrew and Davenant patent grants of 1662 and 1663, which limited the number of theatre companies to just two. In the earlier period, the norm was multiple companies simultaneously. Across the whole of the 110 years at issue, there was obviously a huge swing toward single-author playwriting and a pronounced move away from collaboration and anonymity. The categories are inevitably a bit smudgy. Many of the anonymous plays were probably solo-authored, but we have potent evidence that some of the anonymous plays were in fact joint or group enterprises. “Buckingham’s” The Rehearsal (1671) is an excellent example of the latter. But as far as paratext from title pages goes, evidence for collaboration exists for just two cases over the whole forty years. Late seventeenth-century title pages are an extremely incomplete and unsatisfactory source of statistics on collaboration.

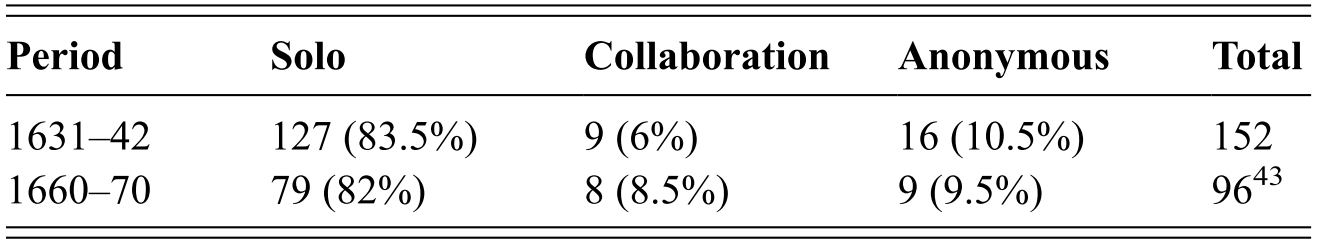

If, however, we look not at the whole span of more than a century, but instead at the periods of roughly a decade immediately before and after the Interregnum, we get a different picture. Kewes’s figures for those two subperiods run as follows:

In terms of the proportions of solo composition, collaboration, and anonymous publication, the percentages seem decidedly congruent, both between the 1630s and 1660s, and all plays versus published plays.

II. New Developments in the 1670s. Why should major generic developments have started to occur rather swiftly in the 1670s?Footnote 44 And how does paratext help us recognize and trace those changes? I see two reasons. First, a new generation of professional playwrights flourished with innovative confidence after getting their work staged at the end of the previous decade. Dryden’s first play reached the stage in 1663, and he had seen seven more to the stage by the end of 1670 (including a collaboration with the Duke of Newcastle, but not counting his collaboration with Davenant in revising The Tempest). Shadwell’s first play was staged in 1668 (The Sullen Lovers), and he had added three more by the end of 1670. Aphra Behn saw her first play to the stage in 1670; John Crowne, Elkanah Settle, and William Wycherley in 1671 (Wycherley admittedly more a gentleman than a professional); Edward Ravenscroft in 1672; Nathaniel Lee and Thomas Otway in 1675; Thomas Durfey in 1676; John Banks in 1677; and Nahum Tate in 1678. Several of them contributed significantly to the boom in titillating sex comedy that moved English comedy into new territory in the 1670s. These professionals were a new generation, writing for theatres that employed sexy women as performers. And scattered among their dedications, prefaces, and addresses (whether triumphant or grumpy) to readers, and prologues and epilogues are all sorts of explanations that collectively help us understand the playwrights’ aspirations for innovation (and some frustrations). A century before newspaper reviews started to become common and, in a world where “reception” was largely undocumented, authorial paratext is our best source of information about playwrights’ aims and audience response.

A second factor that surely contributed substantially to generic change was a growing audience that needed to be accommodated with enlarged auditoriums.Footnote 45 The reader of paratext gets useful glimpses of the changing, growing audience, especially in the prologues and epilogues addressed to that audience. The 1661 “first” Lincoln’s Inn Fields probably held circa 400 spectators; its successor Dorset Garden (opened in 1671) with vastly greater scenic capacity probably held circa 800 jam-packed.Footnote 46 I offer the hypothesis that when the King’s Company built Drury Lane in 1674, they would have aimed at a similar capacity. We have no evidence that the number of courtiers doubled during the 1660s. Consequently, I deduce that the need for expanded auditoriums must have been created by a growing number of “cits” and bourgeois types – persons whose taste in plays was not necessarily identical to those of their social betters.Footnote 47 The post-1660 theatres were, of course, vastly more expensive to attend than their Shakespeare-era predecessors. The Restoration audiences were smaller and wealthier, but they were by no means socially or morally uniform.Footnote 48 We need to refrain from making easy assumptions about what particular segments of the audience would enjoy – or would not tolerate. No Carolean comedy ridicules the “cits” more vigorously or indecently than Ravenscroft’s The London Cuckolds (1681). It remained frequently performed into the 1750s (mostly at Covent Garden), despite utter disdain on the part of the more genteel parts of the audience.Footnote 49

III. Licensing Puzzles. Government licensing for both public performance of plays and printed matter of all sorts has been extensively studied, particularly the latter. Because most twentieth-century scholars regarded “censorship” with hostility, much of the scholarship about the processes of licensing has been decidedly negative. Milton’s Areopagitica (1644) has been hailed and the licencers regarded with scorn and contempt. But major puzzles need to be confronted in this realm.

This is not the place for a survey of the extensive scholarship that has been devoted to regulation of printed materials. For a recent, judicious, and helpful short overview, I strongly recommend the subsections on “Laws Regulating Publication, Speech, and Performance” in five chapters of Margaret J. M. Ezell’s The Later Seventeenth Century.Footnote 50 What the laws said should happen and what actually occurred were two very different matters. The censors reportedly took bribes – not so much to issue a license as to overlook the lack of any license. The final collapse of the licensing process in 1695 has often been treated as a triumph for liberty of the press, but as Ezell points out, this is a simplistic and misguided interpretation. Inducing self-censorship can be a more efficient and effective means of achieving the desired results than paying a bevy of officials to scan a lot of texts before they are set in type. To cut a long story short, prepublication censorship yielded place to threat of post-publication prosecution for seditious libel.Footnote 51

Preperformance censorship of plays carried out by the Master of the Revels worked erratically at best. In 1663, John Wilson’s The Cheats received a license for performance, but was objected to after being performed and a pair of courtiers was directed to tidy it up.Footnote 52 Shadwell’s The Sullen Lovers (1668) was, Pepys quickly learned, a blatant personal satire on Sir Robert Howard (as Sir Positive At-all) and his brother Edward Howard (as Poet Ninny), but any protests they may have made failed to halt either performance or publication. Plays banned because of allusion to the Popish Plot and the Exclusion Crisis circa 1682 were promptly allowed on stage in 1683 when the political situation had cooled off a bit – notably Dryden and Lee’s The Duke of Guise and Crowne’s City Politiques. In some respects, the most spectacular failure of theatrical regulation occurred after the publication of Jeremy Collier’s A Short View of the Immorality, and Profaneness of the English Stage (1698). A flock of the plays that most outraged Collier continued to be a significant part of both companies’ repertories (with the texts apparently unchanged), and the average purity of new comedies was little improved. Collier himself certainly did not believe that his diatribe and its follow-ups had succeeded in bringing about any improvement in the moral standards of new plays. Jonas Barish has argued that Collier’s success made passage of Walpole’s Licensing Act in 1737 “easy,” but a rigorous examination of the old plays that remained in the repertory and the new ones mounted in the years after 1698 suggests, quite to the contrary, that Collier’s near-total failure made eventual passage of Walpole’s act “inevitable.”Footnote 53

Most scholars, myself included, now agree that the low percentage of entries for plays in the Stationers’ Register (about 21%) reflects the rapidly declining authority of the guild toward the end of the century. Publishers’ failure routinely to obtain a publication license for plays in the roughly twenty-six years when the licensing requirement was in force is much harder to understand. By my reckoning, only about a third of the plays that should have been licensed actually received one. Exactly what fees were due and collected by licensers for print is not altogether clear, and if publishers had a rationale for selecting those plays for which they actually bothered to obtain a license, I have failed to spot it.Footnote 54 Licensing for performance did have some demonstrable impact on what got performed and what the Master of the Revels excised, though we have no evidence of post-premiere regulatory oversight. Whether licensing for print had much impact on plays I am inclined to doubt.

IV. The Importance of Performer Identification and Prefatory Criticism. I want to underline both points. Twentieth-century editors and critics made dismally minimal use of this paratextual information. Casting often tells us a great deal about how a playwright conceived various roles. And comments in dedications and prefaces and addresses “To the Reader” often have a lot to say about degree of success (or lack of same) and what the audiences liked or disliked or failed to understand. Such paratextual material is often partisan, may be gloating or recriminatory, and is usually impossible to verify – but a century before reviews begin to become commonplace, it offers us some line on intention and reception.

V. A Note on Post-1660 Reprints of Pre-1642 Plays.Footnote 55 Surveying the changes in paratext norms in new plays between 1660 and 1700 invites a question: what impact (if any) did those norms have on reprints of pre-1642 plays that remained in or rejoined the active repertory? A rigorous investigation of those reprints is still needed. Many of them were in multi-play, usually single-author collections (generally not updated in any way), not singletons. But examination of some of the singletons reveals interesting variations. Six representative cases (taken in chronological order) will suggest some of the possibilities.

First, Jonson’s Catiline, As it is now Acted by His Majestie’s Servants; at the Theatre Royal. The title page states “The Author B.J.” The 1669 edition has a newly written prologue and epilogue spoken by Nell Gwyn, includes a list of more than thirty-five “Persons of the Play,” and specifies “The Scene, Rome.” Actors are not associated with their parts, but a separate list is supplied of “The Principal Tragœdians” (Hart, Mohun, Beeston, Kynaston, and other current members of the King’s Company). This was very much in the fashion of pre-1642 play publication, naming eminent members of the company but not specifying their parts in a particular play.Footnote 56

Second, Beaumont and Fletcher’s A King and No King, As it is now Acted at the Theatre Royal, by His Majesties Servants (1676).Footnote 57 Authorship is duly credited on the title page: “Written by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher.” Twenty-three characters are listed, together with the names of thirteen principal actors – current senior members of the King’s Company, male and female. One part, very unusually, is given as “Bessus – Mr. Lacy, or Mr. Shottrell.” When the play was reissued by Richard Bentley in 1693, it was pretty much verbatim, the cast included. The title page did replace “By His Majesties Servants” with “By Their Majesties Servants,” but “As it is now Acted at the Theatre-Royal” was retained.

Third, The Tragedy of Hamlet Prince of Denmark, As it is now Acted at his Highness the Duke of York’s Theatre (1676). “The Persons Represented” lists seventeen parts against the names of the performers – major and not so major members of the Duke’s Company.Footnote 58 There was no prologue or epilogue, but one would not expect them. Prologue and epilogue were written for first runs and special occasions of various sorts, and this was simply a routine reprint of a repertory staple. But clearly the publishers (J. Martyn and H. Herringman) believed that currency and the names of the Duke’s Company’s players added sales appeal. They also tucked in a note “To the Reader. This Play being too long to be conveniently Acted, such places as might be least prejudicial to the Plot or Sense, are left out upon the Stage: but that we may no way wrong the incomparable Author, are here inserted according to the Original Copy with this Mark “.”Footnote 59

Fourth, The Dutchess of Malfey: A Tragedy. “As it is now Acteed [sic] at the Dukes Theater” (1678). Neither title page nor prelims names the author, which is unusual for a reprint of a well-known professional playwright. One might have thought that John Webster’s name would have some sales value, and the editions of 1623 and 1640 had duly announced “Written by John Webster” on the title page. “The ACTORS Names” are set against fifteen parts. There is no other paratext. Only four performances are recorded with dates in the late seventeenth century: 30 September 1662, 25 November 1668, 31 January 1672, and 13 January 1686. Of fifteen named members of the cast, at least four cannot be confirmed as members of the Duke’s Company in 1678. Extant records suggest that this cast could not have been assembled at any time after autumn 1672, yet the list was not updated for publication in 1678. Perhaps the play remained unperformed in that span, but the unrevised list is not conclusive evidence.

Fifth, Beaumont and Fletcher’s The Scornful Lady. “As it was acted with great Applause by the late Kings Majesties Servants, at the Black-Fryers … The Seventh Edition Corrected and Amended … 1677.” This play had long been popular, and it remained exceptionally so: we have record of ten performances in the 1660s. It was premiered circa 1613–16 and published as a singleton in 1616. The seventh edition lists “The Names of the ACTORS,” but this is misleading: what is given are the characters’ names, not those of the performers. The eighth edition (1691 – not in the English Short Title Catalogue [ESTC] as of February 2022, but available in EEBO) changes the venue formula to “As it is now Acted at the Theatre Royal, by Their Majesties Servants,” but makes no other alterations or additions. It even preserves the spelling of “a Sutur” (suitor) in the identification of two characters. No copy of the putative ninth edition is known to ESTC, but “The Tenth Edition” proves highly problematic. Some copies carry no date, but others do. Both states have a prologue, and an epilogue spoken by Will Pinkethman “mounted on an Ass; a long Whig on the Ass’s Head,” plus a cast dotted with such names as Wilks, Doggett, Mrs Oldfield, and Cibber. As of May 2022, ESTC R28894 dates the edition “[1695?],” but this is preposterous. The title page reads, “As it is now Acted at the Theatre Royal, by Her Majesty’s Company of Comedians,” which means that it cannot possibly date from earlier than March 1702, when King William died and Queen Anne succeeded to the throne. Robert Wilks was in and out of London and is not known to have taken any leading roles until 1699. Barton Booth did not perform in London before 1700. The Biographical Dictionary reports that Pinkethman was performing “ass epilogues” from circa August 1702.Footnote 60 W. W. Greg uncharacteristically fails to realize the significance of “Her Majesty’s Company of Comedians,” and says merely that “The BM catalogue queries 1695 as the date.”Footnote 61 In fact, the cast as printed in the undated tenth edition correlates almost perfectly with the cast as advertised at the Queen’s Theatre on 11 February 1710. I note that under citation number T32940, the ESTC dates what appears to be exactly the same edition “[1710?].”

Obviously, that “tenth” edition has been dated correctly by some modern scholars but misdated by some fifteen years by others. How much paratext information should the bibliographer report? It is mostly mechanical, obvious, and boring – until one little bit turns out to be crucial. The ESTC reportage understandably tends to be bare-bones, and subsequent editions often repeat outmoded information for decades. This is all the more reason for scholars to examine the original paratext now available in EEBO and Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO) with full texts, rather than assume that ESTC will suffice. In recent years, ESTC cataloguing has become more rigorously detailed, though many scholars do not seem to have used the “error” button to point out needed corrections, easy though that now is to do.

Sixth, Shakespeare’s Othello, the Moor of Venice: A Tragedy was duly attributed to William Shakespeare and printed for Bentley and Magnes in 1681. The title page reports, “As it hath been divers times acted at the Globe, and at the Black-Friers: And now at the Theater Royal, by His Majesties Servants.” The paratext consists of a page devoted to listing thirty-seven singleton plays printed for Bentley and Magnes (plus a fifty-play collection of Beaumont and Fletcher, and six novels), and a Dramatis Personae listing thirteen named roles and the actor or actress playing each of them. The scene is specified as “Cyprus.” The cast is definitely for a post-1660 King’s Company production of Othello, but when? The phrase “And now at the Theater Royal” seems to imply performance in 1681. We have no record of any performance of Othello between February 1676 and January 1683, but of course our performance calendar is radically incomplete.Footnote 62 Given publication in 1681 and present tense (“And now”) in the venue statement, we might hypothesize that Othello was in the King’s Company’s current repertory in 1681. It very likely was, but that would be a risky conclusion.

The London Stage editors constructed company rosters for each season and, given the large number of new plays acted and published with cast names in the 1670s, those rosters usually seem relatively complete. Verifying availability of the performers listed in the cast for Othello published in 1681, I find potent evidence that the group specified probably could not have been assembled after the 1674–5 season. Of the performance on 25 January 1675, the London Stage editors correctly observe that “The cast in the edition of 1681 may not, of course, be the one for this performance; but all the performers named in it could have performed at this time.”Footnote 63 Why a cast for a performance closer to publication in 1681 was not printed we can only guess (presuming that there probably was one or more). I note also that when Bentley reprinted Othello in 1687 and again in 1695, he retained the title page “Acted … now” and “His Majesties Servants” (presumably referring in the original instance to Charles II, in the second to James II, and in the third to William) – and the hopelessly dated cast remained unchanged. Not updating casts seems to have been standard operating procedure until well into the second half of the eighteenth century. The rhetoric of title pages can be treacherous, and updating may or may not be carried out in subsequent editions – but in the late seventeenth century, mostly not.Footnote 64

Retrospective

Before turning to a broader overview in which paratext is only one part, I want to summarize briefly what I regard as the crucial takeaway from the technical and bibliographical parts of this Element. First, I should stress the degree to which paratext allows us to recover authorial and audience viewpoints and judgments about a century before the efflorescence of extensive newspaper and magazine reviews and commentary. Prefaces and dedications remain seriously understudied by present-day scholars. Issues such as anonymity, collaboration, use of sources, and the importance of casting to the recreation of seventeenth-century authorial design and performance impact depend, faute de mieux, largely on paratext, but it remains erratically and insufficiently utilized. I have not tried to extend my paratext survey through the eighteenth century, but especially in the world of Bell’s various reprint series (with illustrations), quite a lot changes – a surprising amount, considering how much of the eighteenth-century repertory consists of “old” plays.Footnote 65 Much remains to be done in these realms. Neither have I attempted systematically to confront the knotty problems posed by falsification of title page data and outright piracy in the late seventeenth century beyond pointing out some instances. But I have encountered a dismaying number of them, and until English plays of the period 1660–1800 find their W. W. Greg, skepticism and caution must be considered the better part of valor. The ESTC is a major blessing, but to trust in it unthinkingly is folly. The flood of footnotes accompanying Appendix B is merely a first step toward cleaning up this part of a bibliographic Augean stable.

Overview: The Big Picture, 1590–1800

By way of conclusion, I would like to offer some comments on how paratext of various sorts helps us understand the ways and directions in which English drama was evolving toward the end of the seventeenth century and beyond. Obviously, I am going enormously outside the chronological boundaries announced in my title (“1660–1700”), but a number of readers of my first draft asked how the mass of detail I have catalogued and analyzed for plays published in the late seventeenth century contributes to our grasp of the larger history of which these four decades are merely one part. This is my response.

In many respects, this “evolution” resists tidy conceptualization or quantification, but I believe that my survey underscores, reinforces, and extends the conclusions offered in Paulina Kewes’s important book on “authorship” and “appropriation” in the half century following the Restoration. There was no abrupt change of direction. The quantitative parallels between the 1630s and 1660s outlined earlier in this Element are striking. The long-standing idea of a radical break between 1642 and 1660 is largely false. There are, however, major differences between the larger, cheaper theatres catering to a broader public in the first half of the seventeenth century, and the small, expensive, changeable-scenery theatres constructed after 1660, designed to appeal to what was in the last decades of the century a more elite and wealthier audience.Footnote 66 The cheapest admission price after 1660 was 1s (= 12d) in the second gallery; the most expensive was in the boxes at 4s per spectator. A penny bought entry for standing room in some of the pre-1642 theatres, and so far as we know, 2d could purchase space on a bench. A seat in a well-covered section of the auditorium likely could usually be had for 6d.Footnote 67 Even after inflation is taken into account, theatregoing was enormously more expensive after 1660. Inevitably, the audience became more elite, wealthier, and a lot smaller – though it did not stay that way.

The transition from early seventeenth-century norms to post-1660 norms was unquestionably fostered by changes in the rules governing property rights in plays, already discussed. Before 1642, resistance to publication appears to have been considerable.Footnote 68 After 1660, the playwright had an unquestioned right to sell his or her script to a publisher for whatever it would bring. When it went into print, the author’s name was usually emblazoned on the title page (82%), a drastic contrast with the 48% of plays before 1642 that were announcedly collaborative (20%) or simply anonymous (28%).

A key to understanding the change in how plays were conceived, viewed, and judged (and probably a significant contributor to it) is Gerard Langbaine’s An Account of the English Dramatick Poets. Or, Some Observations And Remarks On the Lives and Writings, of all those that have Publish’d either Comedies, Tragedies, Tragi-Comedies, Pastorals, Masques, Interludes, Farces, or Opera’s in the English Tongue (1691).Footnote 69 For its day, Langbaine’s Account is a bibliographic marvel. In a world without the academic libraries of the nineteenth-century variety that we take for granted, he managed to buy or consult almost all of the plays ever published in English – nearly a thousand of them. He had read them, and he had managed to familiarize himself with an enormous number of sources, both plays and nondramatic, many of them existing only in French, Spanish, or Italian. Langbaine searches out and excoriates “plagiaries” with savage fervor. He is usually less fierce when the source is acknowledged. The forty-eight pages he devotes to Dryden acknowledge his virtues and successes but condemn his appropriations pretty harshly. The seven pages on Aphra Behn admit the success of many of her plays (and grant that Behn often improved on her sources) while roundly denouncing her for inadequately acknowledged borrowings.

Langbaine did not just pop up out of nowhere near the end of the century. Others had objected before him, although less systematically. Twenty years earlier, in 1671, in his “Preface” to An Evening’s Love, Dryden defended his use of his sources. “I am tax’d with stealing all my Playes … ’Tis true, that where ever I have lik’d any story in a Romance, Novel, or forreign Play, I have made no difficulty, nor ever shall, to take the foundation of it, to build it up, and to make it proper for the English Stage.”Footnote 70 What we see in bits and pieces and fragments in paratexts and elsewhere between circa 1670 and 1700 is a growing discomfort with unacknowledged appropriation, particularly where earlier English plays are concerned. The difference at its extremes is profound. If plays are merely popular entertainment, concocted by committee for the masses, and perhaps published or perhaps not – then we are in one world. But if a new play is a literary exercise, solo composed by a named playwright who wants his originality and genius admired, then we are in a different world altogether. There is by no means a tidy transition from the one to the other, but there is a decided shift in balance.

What we see in the course of the forty years following the Restoration can be succinctly described in four points. First, there was more professionalization as a new generation of playwrights earning their living emerged in the 1660s and 1670s. Second, a strong trend developed toward solo authorship, with acknowledged collaboration almost vanishing. Third, concern with “literary” merit increased as opposed to merely pulling in paying customers. Restoration drama aimed at a relatively elite and wealthy audience, and many of the playwrights hoped their work would be judged and valued for aesthetic and moral qualities. Concomitantly, fourth, “originality” was increasingly valued, and disclosure of the use of source materials became expected, even demanded. Curiously enough, the evolution that paratext helps us trace through the seventeenth century was halted and in fact actually reversed in the course of the eighteenth.

If Gerard Langbaine had lived another ten years into the start of the eighteenth century, what would he have predicted the future of English drama to be in the coming 100 years? He might quite reasonably have imagined that the trends of the past seventy-odd years would evolve along the lines so clear between 1630 and 1700 of more solo authorship and less collaborative and anonymous work, along with ever-increased demand for “literary” quality and originality – or at least full disclosure of sources, English and foreign, dramatic and nondramatic. This is very far from what happened. For a sweeping and authoritative overview, extending essentially through the whole century, I refer the reader to Paulina Kewes’s tour-de-force article, “‘[A] Play, Which I Presume to Call Original’: Appropriation, Creative Genius, and Eighteenth-Century Playwriting.”Footnote 71 I see no need for an extensive review of her findings (with which I am in strong agreement). Playwriting became radically more commercial and less literary. Increasing stress in the second half of the century on the star system led to scripts designed to show off the principal actors. At the beginning of the century, Thomas Betterton earned “not quite three times as much as his treasurer and over six times as much as his doorkeepers,” but in the 1790s, J. P. Kemble earned “four times what his treasurer got and about seventy-five times as much as his doorkeepers.”Footnote 72

What a moderately prescient Langbaine might have anticipated in 1700 on the evidence of the previous century might well have included declining regulation of performance (as had already happened for print); expansion in the number of competing theatres, with different managements appealing to different segments of the audience; and some support for an elitist enterprise (in rough parallel to late seventeenth-century developments in Paris).Footnote 73 But this was not to be.

I would like to conclude with an adjuration: scholars should neither ignore paratext nor treat it as pro forma mechanical apparatus. I have been grappling with these plays for the past half century, and I have found this granular scrutiny of paratext decidedly illuminating. It brings us closer to the viewpoint of the playwrights and helps us understand what they were pitching to their audience. And the changing patterns in paratext unquestionably assist us in understanding the broader evolution of the drama whose complex history we are trying to comprehend.Footnote 74

Appendix A: Cumulative Statistics by Decade and in Toto

The figures reported here, decade by decade and for the period as a whole, are calculated from the data recorded in each category as reported in Appendix B.Footnote 1 The first figure in each column records the number of plays premiered in the decade at issue and published (usually the same year or the next) that do contain the specified item of paratext. The figure after the slash (/) records the number of plays in that decade that do not contain that item of paratext. So for “Author named” (usually on the title page) for the 68 plays in the 1660s, 56 (82%) name the author and 12 (18%) do not. If the author is named elsewhere (most commonly in signing a dedication), I have included the case as “author named.”Footnote 2 Percentages are usually rounded to the nearest whole number.

| Category of paratext | 1661–70 | 1671–80 | 1681–90 | 1691–1700 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 68 plays | 125 playsFootnote 3 | 61 plays | 123 plays | |

| Yes/No percentages | Yes/No percentages | Yes/No percentages | Yes/No percentages | |

| Author named | 56/12 82%/18% | 101/24 81%/19% | 57/4 93%/7% | 94/29 76%/24% |

| Subtitle added to title | 23/45 34%/66% | 59/66 47%/53% | 38/23 62%/38% | 57/66 46%/54% |

| Genre designated | 55/13 81%/19% | 109/16 87%/13% | 54/7 89%/11% | 116/7 94%/6% |

| Company/venue | 55/13 81%/19% | 124/1 99%/1% | 61/0 100%/0% | 119/4 97%/3% |

| Licensed for publication | 19/49 28%/72% | 50/61Footnote 4 40%/48% | 11/21 18%/34% | 0/ca.35? 0%/100%Footnote 5 |

| Dedication | 20/48 29%/71% | 74/51 59%/41% | 40/21 66%/34% | 95/28 77%/23% |

| Preface or essay | 21/47 31%/69% | 22/103 18%/82% | 16/45 26%/74% | 46/77 37%/63% |

| Characters listed | 65/3 96%/4% | 123/2 98.4%/1.6% | 60/1 98.3%/1.7% | 122/1 99%/1% |

| Connections explained | 62/6 91%/9% | 100/25 80%/20% | 51/10 82%/18% | 106/17 86%/14% |

| described | 18/50 26%/74% | 49/76 39%/61% | 33/28 56%/44% | 61/62 49%/51% |

| Actors’ names specified | 19/49 28%/72% | 79/46 63%/37% | 46/15 72%/28% | 100/23 81%/19% |

| Location specified | 49/19 72%/28% | 103/22 82%/18% | 44/17 64%/36% | 82/41 67%/33% |

| Prologue/epilogue | 50/18 74%/26% | 120/5 96%/4%% | 59/2 95%/5% | 120/3 97.5%/2.5% |

| Category | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Author named | 308 (82%) | 69 (18%) |

| Subtitle added to title | 177 (47%) | 200 (53%) |

| Genre designated | 334 (88%) | 43 (12%) |

| Company/venue | 359 (95%) | 18 (5%) |

| Licensed for publicationFootnote 6 | 80 (35% est.) | 165 (65% est.) |

| Dedication | 229 (61%) | 148 (39%) |

| Preface or essay | 105 (28%) | 272 (72%) |

| Characters listed | 370 (98%) | 7 (2%) |

| Connections between characters explained | 319 (85%) | 58 (15%) |

| Characters described | 161 (43%) | 216 (57%) |

| Actors’ names specified | 244 (65%) | 133 (35%) |

| Location specified | 278 (74%) | 99 (26%) |

| Prologue/epilogue | 349 (93%) | 28 (7%) |

Cumulative figures for the 377 plays across the whole forty-year period follow.

Appendix B: Twelve Varieties of Paratext in New English Printed Plays, 1660–1700

Plays published more than one calendar year after premiere have the publication year bolded. Plays not published in the seventeenth century are (for obvious reasons) omitted – for example, Orrery’s The General, which was performed in 1664 and survived in manuscript, but was not published until 1937. Playwrights’ names have usually been normalized (e.g., “Southerne” rather than “Southern”). The second column reports the principal title. If it is followed by the symbol ⁑, then there is also a subtitle (usually omitted here). If substantial indebtedness to an earlier play is clearly indicated in the first quarto, that source is identified in the first column, either in parentheses or a footnote (e.g., “adapt. Shakespeare”). If the indebtedness now known is not made clear in the prelims, then it is explained in [brackets] or a footnote. If genre is specified on the title page it is reported; if not, an asterisk (*) follows the title. A dagger (†) indicates the presence on the title page of the company and/or theatre as the venue; conversely, an inverted dagger (⸸) indicates absence of such information (which is rare).Footnote 1 Abbreviations employed in the last column are: Lic = Licence to publish (normally on the title page); Ded = Dedication; Pref = Preface; Loc = location of action specified; P/Ep = prologue and epilogue (P by itself means “prologue only”). [SR] (in brackets) means that the work was entered in the Stationers’ Register by the publisher (obviously not a part of the paratext).

Plays published between 1661 and 1669

| Playwright | Title (and genre if stated) | Publication year | List of characters | Connections explained | Characters described | Names of actors given | Other paratext |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plays premiered in 1661 | |||||||

| Abraham Cowley | Cutter of Coleman-Street. A Comedy† | 1663 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Pref; Loc; P/EpFootnote 2 |

| Sir William Davenant | The Siege of Rhodes [two parts published together]*†Footnote 3 | 1663 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Ded; Loc; P/EpFootnote 4 |

| Plays premiered in 1662 | |||||||

| Sir William Davenant [adapt. Shakespeare] | The Law against Lovers*†Footnote 5 | 1673 Works | Yes | Yes | No | No | Loc |

| Sir Robert Howard | The Committee. A Comedy† | 1665 (coll.)Footnote 6 | Yes | A few | No | No | Lic; Loc; P/Ep; [SR] |

| Sir Robert Howard | The Surprisal. A Comedy† | 1665 (coll.) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Lic; Loc; P/Ep; [SR] |

| Sir William Killigrew | Selindra. A Tragi-comedy⸸ | 1665 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Lic; LocFootnote 7 [SR] |

| Thomas Porter | The Villain. A Tragedy⸸ | 1663 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Loc; P;Footnote 8 [SR] |

| Plays premiered in 1663 | |||||||

| Anon. [Sir William Killigrew]Footnote 9 | Pandora. A Comedy⁑⸸ | 1664 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Lic; Loc; P/Ep;Footnote 10 [SR] |

| Anon. [Sir Robert Stapylton]Footnote 11 | The Step-Mother. A Tragi-Comedy† | 1664 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Lic; Stationer to Reader; Loc; P/EpFootnote 12 |

| Anon. [John Wilson]Footnote 13 | The Cheats. A Comedy⸸ | 1664 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Lic; Author to Reader; Loc; P/Ep;Footnote 14 [SR] |

| “Written by the Lord Viscount Favvlkland”Footnote 15 | The Mariage Night*⸸ | 1664 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Lic;Footnote 16 Loc |

| Sir William Davenant | The Play-house to be Let*⸸ | 1673 (Coll.) | No | No | No | No | [Loc];Footnote 17 P/Ep |

| John Dryden | The Wild Gallant. A Comedy† | 1669 | Yes | Yes | A bit | No | Pref; Loc; P/Ep;Footnote 18 [SR] |

| Richard Flecknoe | Love’s Kingdom. A Pastoral Trage-Comedy†Footnote 19 | 1664 | Yes | Yes | A bit | No | Lic; Ded; “To the noble Readers”; Loc; PFootnote 20 |

| James Howard | The English Mounsieur. A Comedy† | 1674 | Yes | Yes | Some | No | Loc |

| Thomas Porter | The Carnival. A Comedy† | 1664 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Loc |

| Robert StapyltonFootnote 21 | The Slighted Maid. A Comedy† | 1663 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Ded; Loc; P/EpFootnote 22 |

| Sir Samuel TukeFootnote 23 | The Adventures of Five Hours. A Tragi-Comedy⸸ | 1663 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Lic; Ded; Loc; P/Ep;Footnote 24 |

| Plays premiered in 1664Footnote 25 | |||||||

| Anon. [George Villiers Second Duke of Buckingham]Footnote 26 | The Chances [adapted from Fletcher]. A Comedy† | 1682 | No | No | No | No | P/Ep |

| Anon. [Davenant] [adapting Shakespeare]Footnote 27 | Macbeth. A Tragedy† | 1674 | Yes | Yes | No | Some | Argument |

| Anon. [Sir William Davenant] [adaptation]Footnote 28 | The Rivals. A Comedy† | 1668 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Lic; Loc [implicit]; [SR] |