The overthrow and murder of Ngo Dinh Diem and assassination of President John F. Kennedy in November 1963 set in motion a sequence of events that by early 1965 resulted in the beginning what is generally called the Americanization of the Vietnam War. Between late 1963 and early 1965, chaos reigned in the South under Diem’s various inept successors; as a result, the war effort against the Communist insurgency became increasingly ineffectual. The North Vietnamese regime meanwhile qualitatively upgraded its involvement in the Southern insurgency by increasing the infiltration of People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) troops and weapons into the South. Its objective was to destroy South Vietnam’s government and conquer the country before the United States could react. In the United States, the new Johnson administration, which included McNamara and most of Kennedy’s top civilian advisors, remained committed to containing Communism in Vietnam. At the same time, Washington sought to avoid deepening American military involvement in the war against the insurgency.

Faced with a seriously deteriorating situation, the Johnson administration nonetheless at first remained committed to working within the limits established under President Kennedy: that is, to provide aid, including American military advisors, that would enable the South Vietnamese government to resist the Communist insurgency but not to commit American forces to combat. This approach was dictated by Johnson’s determination to prioritize domestic US affairs, beginning with winning the November 1964 presidential election and then by implementing his so-called Great Society program of social reform. After his election, and with the situation in South Vietnam more precarious than ever, Johnson turned to the McNamara strategy of graduated pressure against Hanoi. McNamara intended to convince Ho Chi Minh, Le Duan, and their colleagues in North Vietnam’s ruling Politburo that they could not possibly achieve their goal of taking over South Vietnam and thereby bring them to the negotiating table. Along with the assumption that graduated pressure would enable the United States to deal with Vietnam without interfering with Johnson’s domestic agenda, there was a second reason the president adopted McNamara’s approach to war: to avoid an American military escalation in Vietnam that might draw Communist China and possibly even the Soviet Union into the conflict, an eventuality that carried with it the dreaded risk of nuclear war. As political scientist John Dumbrell has observed, Johnson wanted “to do enough to contain communism in Indochina without risking a confrontation with the big communist powers.”Footnote 1

This chapter covers the deteriorating political and military situation in South Vietnam between late 1963 and early 1965 and how the Johnson administration came to rely on graduated pressure. It reviews the implementation of graduated pressure against North Vietnam along with its complement, the gradual escalation of the US combat effort in South Vietnam, as well as the failure of the overall US policy to produce the desired results. Specifically, between 1965 and 1968 that effort involved the Rolling Thunder bombing campaign over North Vietnam; search and destroy on the ground, backed by air power, in South Vietnam; and assorted American military efforts in Laos and Cambodia. Finally, this chapter covers the 1968 Communist Tet Offensive and its impact on the war in Vietnam and on public opinion in the United States.

South Vietnam, Late 1963 to Early 1965

The government that succeeded the Diem regime, a junta of generals, lasted only three months. Quickly undermined by its incompetence, this junta was in its turn overthrown in a nonviolent coup by yet another general. As one historian has aptly observed, the “coup season” had arrived in South Vietnam.Footnote 2 The year 1964 would see several more coups and a total of seven governments in South Vietnam. These transient governments removed many of Diem’s best military officers and civilian officials, people who had played a key role in successfully prosecuting the war against the Vietcong, and replaced them with less able personnel. Not until the middle of 1965 would one of South Vietnam’s feuding military factions, a group led by Air Vice-Marshall Nguyen Cao Key and General Nguyen Van Thieu, succeed in establishing a semblance of a stable South Vietnamese government, the ninth the country had seen in less than two years.

Given the political turmoil in Saigon, it is not surprising that during the year and a half after Diem’s overthrow, the war effort against the Communist insurgency practically collapsed. In March 1964 Secretary of Defense McNamara reported to President Johnson that the Vietcong had significantly expanded its control in many rural regions of South Vietnam. Contrary to orthodox accounts that trace these developments to Diem, the fault clearly lay with Diem’s successors. Thus a deeply worried McNamara reported that because of the replacement of Diem’s officials (including thirty-five of forty-one province chiefs), the “political control structure extending from Saigon down to hamlets disappeared following the November coup.”Footnote 3 The key fact McNamara was referring to, that the war effort in general and the strategic hamlet program in particular deteriorated only after the coup, has been made convincingly by Mark Moyar in Triumph Forsaken and subsequent writings. Moyar marshals compelling evidence, not only from US sources but also from Communist sources, that the strategic hamlet program, so maligned by orthodox historians, played a crucial role in enabling the South Vietnamese government to extend its control over rural territory and its population, including during the summer and fall of 1963, just prior to the November coup against Diem. The decline of the strategic hamlets, as reported by the CIA, began after that date. Citing official Communist histories of two coastal regions in South Vietnam, Moyar adds that because of Diem’s successes against the Vietcong, in some regions Diem’s strategic hamlets remained strong until mid-1964.Footnote 4

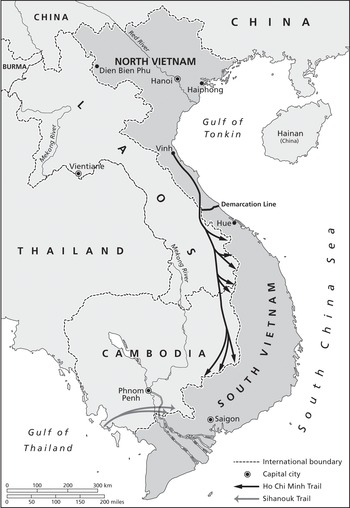

The trouble in Saigon, however, only partly explains the increasing success of the insurgency. The rest of the explanation is provided by actions taken in Hanoi. As early as 1963, when Diem was still in power, infiltrators from North Vietnam already constituted the base of the Vietcong armed forces and technical personnel in South Vietnam.Footnote 5 During 1964 the insurgency was dramatically strengthened by increased infiltration of PAVN units into South Vietnam via the expanded and improved Ho Chi Minh Trail, most of which ran through Laos. Modern arms for Vietcong forces also arrived via that route. These newly arrived PAVN units, notes military historian Dale Andrade, “formed the core of the burgeoning North Vietnamese main force presence in the South, in particular the PAVN 325th Division, which moved south in March 1964.”Footnote 6 By January 1965 the situation had deteriorated to the point where General Taylor, now US Ambassador to South Vietnam, warned of the imminent collapse of the South Vietnamese government. Having opposed the November coup, Taylor now lamented that Washington had failed to appreciate Diem’s success in keeping “centrifugal political forces under control” and added that there was “no adequate replacement for Diem in sight.”Footnote 7 Meanwhile, the pressure on Washington to do something of consequence spiked in February 1965 when the Vietcong attacked the US Marine base at Pleiku in the central part of the country, killing 9 Americans, wounding more than 100, and damaging more than 20 aircraft of various types.

Johnson and McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Graduated Pressure

The Johnson administration’s reaction to the events between November 1963 and the crisis in early 1965 that led to the policy of graduated pressure has been best chronicled by General H. R. McMaster. McMaster documents how Johnson’s domestic political agenda, beginning with securing his election in November 1964, dictated US military policy in Vietnam. Prior to the election, President Johnson wanted to be seen as the moderate candidate with regard to Vietnam, in contrast to his Republican opponent Senator Barry Goldwater, and therefore he was only willing to approve measures that would enhance that image. Once elected, Johnson’s first and overriding commitment was to his Great Society program of social reform. This in turn meant that he was only prepared to commit forces to Vietnam sufficient to keep the Saigon regime from losing the war. These priorities were reinforced by the low opinion of America’s military leaders Johnson, a man with no military experience, shared with Kennedy and McNamara. McMaster chronicles McNamara’s contempt for the professional military officers and his confidence, completely unjustified as events would show, that he and his civilian advisors understood how to wage war better than military professionals. McMaster criticizes Johnson and his civilian advisors for ignoring the military advice they received from the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS). He documents how McNamara, aided by General Maxwell Taylor, chairman of the JCS from 1962 until 1964, prevented the views of the other Joint Chiefs from reaching the president. McMaster points out that as early as January 1964, the Joint Chiefs, writing to McNamara, made it clear that the US military strategy based on graduated pressure could not succeed. The JCS urged that “victory” be the goal in South Vietnam and wanted to develop a military campaign, including bombing North Vietnam and mining its ports through which military supplies arrived from the Soviet Union and China, to secure that goal. That recommendation was not acted upon because even by early 1964 the JCS on the one hand and Johnson and his civilian advisors on the other, in McMaster’s words, “had started down different paths.”Footnote 8

McMaster, to be sure, does not give the Joint Chiefs a pass. Despite their firm conviction that the Johnson/McNamara military policy in Vietnam could not succeed, he writes, the Joint Chiefs could not overcome their interservice differences and personal bickering and become effective advocates for a military strategy they believed was necessary to defeat the Communist insurgency in Vietnam. Perhaps their most egregious failure occurred in July 1965 when the Joint Chiefs, minus their chairman, General Earle Wheeler, who was in South Vietnam at the time, met with members of the House Armed Services Committee and avoided answering questions about the level of force that would be required to win the war.Footnote 9 McMaster points out that the Joint Chiefs hoped that graduated pressure would evolve into a different strategy “more in keeping with their belief in the necessity of greater force and its more resolute application.” But by failing to confront the president with their objections and attempting to work within the McNamara strategy, they gave “tacit approval” to graduated pressure during the critical time when it was first implemented.Footnote 10

McMaster’s chronicle of events raises the question of what the Joint Chiefs could have effectively done while Johnson was in the White House, given the realities of the American political system under which civilian authorities control the military, to end the reliance on graduated pressure. That is one reason revisionist commentators vary in their evaluations of the JCS. Some offer generally negative assessments. General Bruce Palmer Jr., who served in Vietnam as overall commander of Field Force II (one of the four US military regions in South Vietnam) and later as deputy to General Westmoreland, criticizes the JCS but not as harshly as McMaster. In The 25-Year War, a volume published thirteen years before McMaster’s, Palmer chastises the JCS for its inability to “articulate an effective military strategy that they could persuade the commander-in-chief to adopt.” But he also suggests that the JCS were limited in their objections to the Johnson/McNamara strategy by the military’s “can do” spirit and because they did not want to seem disloyal. Robert E. Morris criticizes the Joint Chiefs because they “acquiesced as strategy was formulated by the whiz kids and implemented in haphazard fashion.”Footnote 11

Other revisionists are more charitable to the Joint Chiefs. Christopher Gacek, in reviewing the decision making in Washington during late 1964, finds it “hard to imagine how a government could contemplate going to war and have such disregard for the opinions of its military leaders.” Jacob Van Staaveren served for more than twenty years as a historian for the US Air Force history program. Among his many studies is Gradual Failure: The Air War Over North Vietnam, 1965–1966, a classified work written in the 1970s that was not published until 2003; it remains the most comprehensive and authoritative history of the Rolling Thunder campaign during those years. In Gradual Failure Staaveren chronicles how as early as 1964 the Joint Chiefs stressed the necessity of strong measures against North Vietnam and how by the fall of that year they were “exasperated and dismayed” by Johnson’s and McNamara’s failure to heed their advice. He notes how on November 1, 1964, General Wheeler told McNamara that most of the Joint Chiefs believed that failing additional military action the United States should withdraw from Vietnam. Mark Moyar stresses the difficulties the Joint Chiefs faced in dealing with McNamara and Johnson and the limited options available to them. He concludes, specifically mentioning McMaster in a footnote, that by working with Johnson while trying to influence him, the Joint Chiefs “chose the best of the inferior options available.”Footnote 12

Graduated Pressure and Gradual Escalation in Practice

The first airstrikes against North Vietnam, in August 1964 and again in February 1965, were intended as strictly retaliatory measures in response to North Vietnamese attacks against US forces, in the former case an American destroyer on patrol in the Gulf of Tonkin (the Gulf of Tonkin Incident) and in the latter American bases in South Vietnam. However, by early 1965 President Johnson and his top advisors, aware that without a strong demonstration of US support the government of South Vietnam could collapse, understood they had to go beyond mere reprisals. The campaign to apply graduated pressure against Hanoi via systematic and sustained bombing, known as Rolling Thunder, therefore began in March 1965. Rolling Thunder had two complementary goals: first, to raise the cost of North Vietnam’s sponsorship of the insurgency in South Vietnam to the point where Hanoi would be convinced it could not succeed and therefore would agree to negotiations; and, second, to inhibit the infiltration of troops and supplies into South Vietnam to the point where the insurgency there could be defeated. Johnson’s civilian advisors who formulated the Rolling Thunder bombing campaign against North Vietnam did not address what should be done at that time in South Vietnam.Footnote 13 However, because the situation on the ground in South Vietnam was so urgent, Johnson decided to send the first US combat troops to South Vietnam (Marines tasked with defending the important Da Nang airfield), with the first units arriving within days of the start of Rolling Thunder. The president and some of his advisors seem to have believed that sending a small number of combat troops to South Vietnam would be another way, albeit indirect, to apply graduated pressure on North Vietnam and force Hanoi into negotiations. Instead, when Hanoi did not respond as hoped, the United States was forced to begin a policy of gradual escalation in South Vietnam. As McMaster aptly puts it, Johnson’s decisions of early 1965 “transformed the conflict in Vietnam into an American war.”Footnote 14

Rolling Thunder

Rolling Thunder was one of several US bombing campaigns during the Vietnam War. It lasted from March 1965 to November 1968 and was carried out by US Air Force and Navy aircraft. Among the other campaigns, Barrel Roll (December 1964–March 1973) supported the Royal Laotian government against Communist forces in northern Laos and also attacked the Ho Chi Minh Trail to stop North Vietnamese infiltration of troops and supplies into South Vietnam. Steel Tiger (April 1965–November 1968) attempted to interdict North Vietnamese infiltration via the Ho Chi Minh Trail in the northern part of the Laotian panhandle. Tiger Hound (December 1965–November 1968) did the same in the southern part of the Laotian panhandle. Commando Hunt (November 1968–April 1972) was the successor to Tiger Hound. Menu (March 1969–May 1970) attacked PAVN and Vietcong base camps inside Cambodia; it was followed by Freedom Deal (May 1970–August 1973), which supported the Cambodian government’s struggle against local Communist guerrillas. Linebacker I was directed against North Vietnam during Hanoi’s 1972 Easter Offensive against South Vietnam. It was closely followed by Linebacker II, the so-called Christmas Bombing launched in December 1972 to force Hanoi to make concessions in negotiations going on in Paris. American, South Vietnamese, and other allied warplanes dropped about eight million tons of bombs in Indochina during the Vietnam War, with US aircraft accounting for about 82 percent of that total. About half the total tonnage, approximately four million tons, was dropped in South Vietnam in support of military operations there. Much of the rest were dropped in Laos and Cambodia as part of US efforts to interdict North Vietnamese troops and supplies en route to South Vietnam. Only slightly more than a tenth, about 880,000 tons, actually were dropped on North Vietnam.Footnote 15 However, Rolling Thunder was the main means by which the United States attempted to systematically apply graduated pressure on North Vietnam and therefore merits extensive discussion.

Orthodox and revisionist commentators agree on one salient point: Rolling Thunder failed. It did not force North Vietnam to the negotiating table, and it did not sufficiently interdict the North Vietnamese infiltration effort into South Vietnam. However, the respective commentators do not agree on why Rolling Thunder failed. Orthodox historians generally argue that North Vietnam, with its largely agricultural economy, was not a suitable target for strategic bombing, which was based on US doctrine developed during World War II in campaigns against Germany and Japan, both heavily industrialized nations. North Vietnam’s military supplies came from outside patrons (the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China [PRC]), so its ability to wage war would not be damaged by bombing as was Germany’s and Japan’s. Orthodox commentators also argue that interdiction of North Vietnamese infiltration into South Vietnam was futile since Communist forces fighting a guerrilla war there needed so few outside supplies that their needs could be satisfied even if only a small percentage of what Hanoi sent actually reached its destination. This point, however, as some of these same commentators acknowledge, only applies to the situation as it existed up to the early 1960s, that is, before large PAVN forces equipped with heavy weapons and requiring a wide range of supplies were in the South. Finally, orthodox commentators stress that North Vietnam was too determined to attain its objective of conquering South Vietnam to be intimidated by American bombs. These factors, orthodox commentators conclude, made North Vietnam immune to US conventional strategic bombing.Footnote 16

The revisionist response has two essential parts. First, revisionists argue that North Vietnam was vulnerable to a properly carried out bombing campaign. Rolling Thunder therefore could have been effective and achieved its goals. Second, they explain the reasons why the United States did not successfully exploit North Vietnam’s vulnerability.

C. Dale Walton has effectively summarized the first part of the revisionist argument. He points out that North Vietnam’s lack of industry made it dependent on military imports to carry on the war, and that dependence actually increased its vulnerability to airpower. These vital military supplies came from the Soviet Union and China, with the former supplying heavy and sophisticated weaponry such as fighter planes, tanks, antiaircraft artillery, antiaircraft missiles, radar systems, trucks, and field artillery (which together eventually comprised 80 percent of all imported North Vietnamese supplies) and the latter supplying the bulk of North Vietnam’s small arms and ammunition. Closing down North Vietnam’s ports, in particular mining the port of Haiphong, Walton argues, “alone would have virtually eliminated the Soviet Union’s freedom to supply its client.” Attacks on key railroads and highways, along with mining inland waterways, “would have severely constrained the PRC’s ability to assist the DRV.” Airpower simultaneously could have been used to shatter vital North Vietnamese infrastructure, including storage facilities, supply depots, factories engaged in war production, military bases, airports, and government buildings. Air power therefore could have crippled North Vietnam’s ability to wage war against South Vietnam had it been properly used.Footnote 17

The second part of the revisionist response, the reason North Vietnam’s vulnerability to air power was not exploited, has several components. Revisionists place most of the blame for the failure of Rolling Thunder on the Johnson administration for imposing restrictions on the bombing of North Vietnam that made it impossible for the campaign to succeed. These restrictions included, but were not confined to, limits on the targets US warplanes could attack, rules of engagement (ROEs) that made it more difficult for American pilots to hit their targets while exposing them to greater risk, and the timing under which targets were attacked. At the same time, some commentators who offer these and related arguments, including serving US Air Force officers, also echo the orthodox case by criticizing senior US Air Force commanders for failing to assess the situation they faced and remaining wedded to World War II doctrine that had been designed for attacking industrialized countries and therefore was unsuited for the task at hand. However, those offering this particular critique do not always provide suggestions for how the US Air Force – and presumably the US Navy – should have modified its doctrine.Footnote 18

Robert E. Morris has characterized America’s overall military effort in Vietnam as a policy of “escalation and de-escalation, an ‘on again off again’ knee-jerk reaction that varied with the intuitive whims of President Johnson and his advisors.”Footnote 19 That observation is particularly apt with regard to the Rolling Thunder. Rolling Thunder was the key pillar of graduated pressure because it was the main way in which the war was taken directly to North Vietnam itself, as opposed to the military effort being conducted against Hanoi’s proxy forces and PAVN troops in South Vietnam. Presumably a campaign that would start slowly and deliver its message to Hanoi by increasing pressure in carefully calibrated increments, Rolling Thunder’s “on again, off again” implementation included seven major bombing halts (plus smaller ones that brought the total to sixteen) instituted with the hope of serving as the carrot that along with the stick of bombing would bring North Vietnam to the negotiating table. The effect of this erratic approach was the opposite. North Vietnam made it clear from the start that it was not interested in any negotiations that would interfere with the goal of taking control of South Vietnam. Meanwhile, the pauses, the “graduated” increase in the intensity of the bombing, and Washington’s restrictions on the bombing of many significant military targets bolstered Hanoi’s resolve. In A Soldier Reports, his memoir on the war, General Westmoreland ruefully wonders how anyone could have expected the North Vietnamese to negotiate “when the only thing that might hurt them – the bombing – was pursued in a manner that communicated not determination and resolution but weakness and trepidation?” He adds, “The signals we were sending were signals of our own distress.” Graduated American bombing also enabled the North Vietnamese to disperse their most important resources, including their oil supplies, and otherwise prepare for future attacks while also exploiting the bombing for propaganda purposes by focusing attention on civilian casualties and damage. Perhaps worst of all, bombing pauses and targeting restrictions enabled the North Vietnamese to build a sophisticated air defense system.Footnote 20

The ROEs the Johnson administration imposed on US aircraft attacking North Vietnam compounded the problems caused by Rolling Thunder’s gradualist strategy. These ROEs have been widely and often bitterly criticized by revisionist commentators.Footnote 21 They were of two kinds, geographical and operational. Geographical limits placed key areas out of bounds, initially all of North Vietnam above the 20th parallel, which left Hanoi, Haiphong, and the rest of the country’s heartland immune from US attacks. Even when the 20th parallel limit was lifted, important geographic restrictions remained, most importantly restricted and prohibited zones around Hanoi and Haiphong. Operating restrictions included totally or partially prohibiting attacks against targets the military wanted to hit. Usually these were considered civilian targets, although at times that designation was questionable. Also, attacks on military targets near protected civilian targets also were strictly limited. Making matters worse, the ROEs were complicated and frequently changed, to the point where at times it was difficult for pilots to know on a day-to-day basis what they actually were. The ROEs made inherently difficult missions even more dangerous. They made it impossible to wage the air war according to US Air Force doctrine, which called for inflicting maximum damage on enemy forces and the infrastructure that supported them by attacking vital targets in the enemy’s heartland essential to its ability and will to fight. On a more fundamental level, the ROEs made it extremely difficult to adhere to two key principles of waging war: security, never allowing the enemy to acquire an unexpected advantage; and surprise, striking the enemy at a time and place or in a manner for which it is unprepared.Footnote 22

All of this was done against the advice of the administration’s military advisors, most notably the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who from the start of Rolling Thunder were urging a much more intensive campaign than that approved by the president. The original JCS plan, to be directed at ninety-four targets during a four-phase operation over thirteen weeks, was rejected, notwithstanding the support it received from both General Westmoreland and Admiral Ulysses S. Sharpe, commander-in-chief of the US Pacific Command. General Taylor, by then ambassador to South Vietnam, took the middle ground, favoring stronger attacks than those authorized by President Johnson but not at the level recommended by the JCS. Air Force Chief of Staff John P. McConnell favored an even more intense twenty-eight-day campaign. As early as February 1965, just before the onset of Rolling Thunder, Admiral Sharpe wrote to the JCS that the administration’s proposed “graduated reprisal” campaign was inadequate. In April 1965, a month into Rolling Thunder, JCS Chairman General Earle G. Wheeler warned Secretary of Defense McNamara that US strikes had “not curtailed DRV military capabilities in any major way.”Footnote 23 CIA Director John McCone voiced the same concern. In a memo that same April to the president’s top advisors, McCone warned that United States had to “change the ground rules of the strikes against North Vietnam. We must hit them hard, more frequently, and inflict greater damage.”Footnote 24

This advice was repeated frequently in 1965 and in the years that followed. The failure to heed professional military advice became, and has remained, a sore point among senior military officers who served during the war as well as with revisionist commentators who believe the air campaign against North Vietnam could have made a substantial contribution to the war effort. General McConnell, upon retiring in 1969, told the National Security Council that Rolling Thunder’s lack of success stemmed from “restrictions placed upon the Air Force.”Footnote 25 In his history of the war, General Phillip B. Davidson writes that “gradualism forced the United States into a lengthy, indecisive air war of attrition – the very kind which best suited Ho and Giap.”Footnote 26 Colonel Joseph R. Cerami has noted, “the progressive, slow squeeze option succeeded only in preventing the attainment of U.S. strategic objectives.”Footnote 27 US Air Force Reserve Colonel John K. Ellsworth makes a more fundamental point: the Johnson administration, following McNamara’s theories, “did not understand airpower or military doctrines. Consequently, it did not utilize air power the way it was intended to be used.” Specifically:

[President] Johnson showed that he did not understand the inherent nature of airpower as an offensive weapon. Aerial combat is much different from ground warfare: the vastness of airspace promotes offensive actions rather than defensive or protective measures. Defensive tactics are counter-productive. Since you can be attacked from any direction by airpower, it is therefore imperative that air leaders be allowed to force the fight and take the offensive to the enemy. Bombing halts and cease-fires hindered a continuous and concentrated strategic bombing campaign; they allowed the North Vietnamese to reconstitute their forces, reestablish their lines of supply, and generally outlast the American effort.Footnote 28

Finally, Dale Walton makes an equally fundamental point when he notes that US policy makers made a “critical strategic error” when they used the air campaign against North Vietnam as a tool of diplomacy rather than as an instrument to weaken the DRV’s ability to continue the war. This forced the Americans into the absurd position of leaving the most important targets untouched so they could be used as leverage to force Hanoi to the bargaining table. And this in turn “undermined the effectiveness of the entire air war” because it enabled the North Vietnamese to adjust to the bombing, disperse their most valuable resources, and build their formidable air defense system.Footnote 29

The matter of what should have been done about North Vietnam’s air defenses is a particularly sore point because of the enormous toll they ultimately took on American airmen. As of late 1964, North Vietnam had a relatively unsophisticated air defense system based on 1,400 antiaircraft artillery pieces. Its air force had only thirty-four fighter aircraft, old MiG-15s and MiG-17s. It was after the first Rolling Thunder bombing pause, which began in May 1965, that North Vietnam began integrating Soviet-built SA-2 surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) into its air defense system. By 1966, Hanoi and other strategic centers in North Vietnam were protected by a sophisticated, world-class air defense system that included SAM missiles, antiaircraft artillery, and Soviet-built MiG fighters. By November 1968, when Rolling Thunder ended, that air defense system included 200 SAM sites, more than 8,000 antiaircraft artillery pieces, more than 400 radars of various types, and an air force of 75 fighters that included advanced MiG-21s as well as MiG-19s and MiG-17s.Footnote 30

The antiaircraft artillery pieces alone were dangerous enough. The North Vietnamese, taking advantage of the delay in US reprisals, had almost 1,000 antiaircraft artillery pieces deployed at likely bombing targets by February 1965; by December 1965 there were more than 2,200, and, as noted earlier, by 1968 more than 8,000. These weapons took a heavy toll on US aircraft during the reprisal raids of February 1965 and the early Rolling Thunder attacks that followed. Ultimately they would account for 68 percent of all the US aircraft lost in Vietnam during the war. Meanwhile, although the United States learned early in April 1965 that SAM sites were being built, Washington did not permit attacks against them until July, and then only against sites outside the Hanoi/Haiphong region. In A Soldier Reports, General Westmoreland reported an incident, widely cited in the secondary literature on the war, which took place in Saigon shortly after the United States discovered SAM construction. Westmoreland and his air commander, General Joseph H. Moore, wanted to bomb the SAM sites before they were completed. They raised the matter with John McNaughton, an assistant secretary of defense. He responded: “You don’t think the North Vietnamese are going to use them! Putting them in is just a political ploy by the Russians to appease Hanoi.” That response echoed a memo McNaughton had written to McNamara, which opined, “We won’t bomb the sites, and that will be a signal to North Vietnam not to use them,” an assessment McNamara shared. Westmoreland, not surprisingly, was furious, and in A Soldier Reports denounced what he called this sending of signals by the “clever civilian theorists in Washington.”Footnote 31

As Leslie H. Gelb and Richard K. Betts, two orthodox commentators, noted in The Irony of Vietnam: The System Worked, “McNaughton turned out to be wrong. The DRV was soon using SAMs to knock down large numbers of U.S. warplanes.”Footnote 32 US pilots had various techniques to avoid or defeat the SAMS, from jamming and destroying the radars that guided them to dropping down to lower altitudes, and relatively few aircraft were lost to North Vietnamese SAMs. But the SAMs still affected missions over North Vietnam. Even when these missiles missed their targets, combat aircraft that dropped to a lower altitude to avoid them were forced into what long-time AIR FORCE Magazine editor John T. Correll has called the “lethal shooting gallery of the [antiaircraft] guns.”Footnote 33

Even when attacks against SAMs were permitted, rules of engagement imposed by Washington severely limited their effectiveness. Airmen often could only attack SAMs actually firing on them. Therefore, in one incident when US Navy pilots found 111 SAMs being transported on railcars, they could not attack them. “We had to fight all 111 one at a time,” one pilot recalled. The North Vietnamese, well aware of US rules of engagement, took advantage of them. To protect their SAM bases, they located as many as they could within ten miles of Hanoi since that city normally was safe from attack. SAMs could attack aircraft as far as twenty-seven miles from Hanoi, and that put many American aircraft attacking targets along the transportation system moving troops and supplies southward within their range. In fact, most of the targets along that transportation network in North Vietnam were within thirty miles of Hanoi. Thus, notes General William W. Momyer, who commanded the US Seventh Air Force in Vietnam from 1966 to 1968, “the SAMs could hit us whenever we came after one of their more significant targets near Hanoi, but our rules of engagement prevented us, in most cases, from hitting back.”Footnote 34

In addition, by April 1965 US aircraft on bombing raids were being engaged by North Vietnamese MiGs, but Johnson and McNamara did not permit attacks against the airfields those MiGs flew from in North Vietnam.Footnote 35 They thereby ignored US airpower doctrine, which sensibly called for striking enemy airfields at the beginning of a campaign. This enabled North Vietnamese MiGs, first MiG-17s and within a year advanced MiG-21s, to challenge US aircraft, which then had to engage them in aerial battles. The most important North Vietnamese MiG base was Phuc Yen airfield, about twenty miles northwest of Hanoi. The pleas of the military commanders in Vietnam and Joint Chiefs notwithstanding, US aircraft were forbidden to attack Phuc Yen or any other North Vietnamese airbase for two years. Until 1967 US pilots attempting to destroy enemy aircraft literally had to watch enemy airfields and wait until the MiGs stationed there took off and attacked them before taking action. Thomson notes that the lesson of this failure was learned, albeit too late for many pilots who flew in Vietnam: “In Rolling Thunder the Air Force had been forbidden to attack enemy airfields for two years. In Desert Storm [the 1991 campaign against Iraq], enemy airfields were attacked the first night.”Footnote 36

General Momyer has pointed out that in early 1965 the overall North Vietnamese system of radars, antiaircraft guns, SAMs, and MiGs was in an embryonic state and could have been destroyed with no significant American aircraft losses. That was not done because US civilian officials feared such action would be an escalation of the war that might trigger Chinese and possibly even Soviet intervention. Momyer adds that as a result the system was allowed to expand without significant US interference until the spring of 1966, when methodical attacks were permitted against parts it. “We were never allowed to attack the entire system,” he concludes with understandable frustration.Footnote 37

The issue of possible great power military intervention – the real concern was China, Soviet intervention was considered far less likely – was legitimate, especially given China’s intervention in the Korean War less than fifteen years earlier. Revisionist commentators acknowledge this. Walton, for example, notes it would have been “irresponsible for decision makers not to consider the possibility that China would intervene on North Vietnam’s behalf.” However, Walton makes a strong case that the risk of this happening was low; he maintains that there was sufficient evidence that the United States “with considerable confidence” could have escalated the war against North Vietnam. Mark Moyar has seconded this conclusion with additional evidence, including comments by Mao Zedong to journalist Edgar Snow published in February 1965 in The New Republic. Snow summarized Mao’s viewpoint as follows: “China’s armies would not go beyond her borders to fight. That was clear enough. Only if the United States attacked China would China fight. Wasn’t that clear?”Footnote 38 This assumption about Chinese intentions is especially true if one considers only Rolling Thunder, as opposed to the suggestion that the United States should have invaded the southern part of North Vietnam. For example, Chen Jian has noted that in June 1965 the Chinese made it clear to their comrades in Hanoi that as long as the war remained in its “current status” – meaning US military actions in South Vietnam while using only air power to bomb North Vietnam – the Vietnamese would have to fight by themselves, albeit with Chinese military and other aid. Xioming Zhang, covering the same period, citing Zhou Enlai, notes that Beijing “under the current circumstances” was not going to provoke a direct Sino-American confrontation.Footnote 39 As Walton puts it, “China did not trap US policy makers – because of their extreme risk aversion, those leaders trapped themselves.”Footnote 40

Limits imposed by Washington also severely hindered interdiction. Johnson’s refusal to bomb key railways, highway bridges, and storage facilities in the northern part of North Vietnam, and, above all, mine North Vietnam’s ports, especially Haiphong, its most important port, made it impossible to sufficiently interdict the flow of military supplies destined for Communist forces in South Vietnam. Thompson has summed up the situation the US Air Force and Navy faced in attempting to interdict the flow of weapons and supplies into South Vietnam. Approximately a third of North Vietnam’s imports came by railroad running northeast into China while most of the rest arrived via the port of Haiphong. Since North Vietnam imported most of its military supplies, General Momyer deemed it essential to close the Haiphong port and sever the northeast railroad link with China. However, President Johnson refused to permit the US Navy to bomb and mine the port of Haiphong because, with Soviet ships there, he feared an incident that might lead to a wider war. The US Air Force was permitted to bomb the northeast railroad but not the largest bridges across the Red River at Hanoi because Johnson wanted to avoid civilian casualties. Effective bombing of the railroad yards was precluded because Johnson refused to permit the use of B-52 bombers, the aircraft that could carry the heavy bomb loads required for the job. There were other restrictions as well.Footnote 41

The result was that US airpower was used in a manner for which it was not suited. In discussing the general problem of using air power for interdiction, Momyer later wrote that reducing an enemy’s supply line to zero is “virtually impossible so long as he is willing to pay an extravagant price in lost men and supplies.” The object therefore should be to reduce the supply flow as much as possible and raise the cost as high as possible. This means focusing an air campaign on the most vital supply targets such as factories, power plants, refineries, marshalling yards, and transportation lines that carry supplies in bulk. Waiting until the enemy “has disseminated his supplies among thousands of trucks, sampans, rafts, bicycles, and then to send our multimillion-dollar aircraft after these individual vehicles – this is how to maximize our cost, not his.”Footnote 42 Yet, to Momyer’s great frustration, this is exactly what the United States did in Vietnam during Rolling Thunder. The Johnson administration forced its airmen to interdict North Vietnamese supplies retail rather than wholesale.

It has repeatedly been pointed out that ultimately the United States attacked almost every target on its Air Force’s original target list. The overall destruction was massive: 65 percent of North Vietnam’s POL (petroleum, oil, lubricants) storage capacity, 60 percent of its power-generating capacity, half of its major bridges (at one point or another), 10,000 trucks, 2,000 railroad cars, and 20 locomotives.Footnote 43 It also is constantly repeated that the United States dropped more tonnage on Vietnam, North and South, than was dropped by all combatants during the entirety of World War II. However, these statistics, in Walton’s words, “prove nothing.” The reason is that the “most lucrative targets in North Vietnam … were intentionally left undisturbed by the Johnson administration.” These included North Vietnam’s industrial infrastructure, the port of Haiphong, key railroads and bridges, and the seat of government in Hanoi. Going beyond North Vietnam, Walton adds that the United States restricted “the wrong part of the air war.” It is precisely bombing in South Vietnam that should have been “carefully circumscribed,” while the campaign against North Vietnam should have been “nearly unrestricted.”Footnote 44 Thompson makes essentially the same points. He notes that in North Vietnam “the bombs kept falling on less important targets” and that much of the bombing in Southeast Asia as a whole “did nothing but tear up jungle.”Footnote 45 To which Staaveren adds, with reference to 1965 but applicable to the entire Rolling Thunder campaign, “combat pilots took many risks and often suffered high losses by striking and restriking a large number of relatively unimportant targets.”Footnote 46

Two additional perspectives, one American and one North Vietnamese, merit serious consideration in evaluating graduated response and the failure of Rolling Thunder. Douglas Pike served for many years as a US Foreign Service officer and, after his retirement, as director of the Indochinese Studies Project at the University of California, Berkeley. He was one of America’s leading experts on Vietnam and probably its leading civilian expert on the Vietnamese armed forces. At a symposium in 1983, Pike compared the results of Rolling Thunder under President Johnson to those of the massive US air assault against Hanoi and Haiphong under Richard Nixon in December 1972, when most of the restrictions of the earlier campaign were removed. In his view, “while conditions had changed vastly in seven years, the dismaying conclusion to suggest itself from the 1972 Christmas bombing is that had this kind of air assault been launched in 1965, the Vietnam war as we know it might have been over within a matter of months, even weeks.”Footnote 47 Bui Tin served as a colonel on the general staff of the North Vietnamese army and as a war correspondent; as the highest-ranking officer on the scene in Saigon on April 30, 1975, he received the South Vietnamese government’s surrender. (He later became disillusioned with the Vietnamese Communist movement and moved to France.) Bui Tin’s view from the other side lends considerable support to Pike’s assessment. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal in August 1995, Bui Tin was asked about the US bombing of North Vietnam. He answered as follows: “If all the bombing had been concentrated at one time, it would have hurt our efforts. But the bombing was expanded in slow stages under Johnson and didn’t worry us. We had plenty of time to prepare alternate routes and facilities.”Footnote 48

John T. Correll has provided an appropriate epitaph for Rolling Thunder. He acknowledges that it is impossible to know what an all-out bombing campaign in 1965, as the US Air Force commanders wanted, would have achieved. That said, he insists, “when Rolling Thunder ended, our best chance of knocking North Vietnam out of the war was gone.” Finally, he cogently and ruefully observes, “Rolling Thunder had not been built to succeed, and it didn’t.”Footnote 49

Search and Destroy

If it is reasonable to say that there is something of a revisionist consensus about the shortcomings of graduated pressure as applied to the air war against North Vietnam and how they could have been corrected, the same cannot be said regarding the ground war against Communist military forces in South Vietnam. At issue is General Westmoreland’s campaign of “search and destroy,” according to which American combat troops focused primarily on seeking out large Communist units, usually in difficult jungle terrain, to engage them in large-scale battles. Search and destroy, it should be noted, was not graduated pressure in the same sense as Rolling Thunder. First, it was confined to South Vietnam and therefore did not directly affect North Vietnam. Second, although the US troop buildup in South Vietnam took place gradually over three years (1965–1968), it was undertaken in response to the requirements of the military situation on the ground, not as part of a strategy of systematically increasing pressure on the enemy. Third, inside South Vietnam – as opposed to the Washington’s stricture that US and South Vietnamese forces not enter Laos, Cambodia, or North Vietnam – search and destroy was not subject to strict limitations and micromanagement from Washington as was Rolling Thunder. However, as with Rolling Thunder, search and destroy was pursued as part of the overall military policy of gradual escalation, an approach that rejected the option of seeking a decisive military victory as quickly as possible in favor of creating a situation that would force North Vietnam into negotiations in which it would have to accept the independence of South Vietnam.

Search and destroy was the primary American approach to the ground war from the arrival of US combat troops in South Vietnam in March 1965 until after the Communist Tet Offensive of early 1968. It relied heavily on American technology, which among other advantages provided unprecedented mobility via the use of helicopters to quickly transport large American infantry units into combat areas, and on superior US firepower, both ground based and airborne, to overwhelm Communist forces. Search and destroy was essentially a strategy of attrition, the goal being to wear down the enemy and ultimately reach the so-called cross-over point, where Communist casualties would exceed the ability to replace them, and thereby force Hanoi to give up its effort to conquer South Vietnam. That goal was not achieved. The only cross-over point that was reached during the search and destroy era was that American casualties, although far lower than those suffered by North Vietnam, eventually reached the point where they were no longer acceptable to the American public.

The debate among revisionists over search and destroy is a continuation of a clash of viewpoints that began during the war; it is now more than half a century old. A key point of contention is what kind of war North Vietnam was waging to conquer South Vietnam – was it primarily a guerrilla insurgency or a conventional war? – and, therefore, how the United States should have responded militarily. The opposing poles in this disagreement among revisionists as it evolved after the war are provided by two US Army officers who served in Vietnam, Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Krepinevich, author of The Army in Vietnam (1986), and Colonel Harry Summers, author of On Strategy (1982), the former making the case for guerrilla insurgency and the latter for conventional war. There are, as there were during the war, all sorts of gradations, combinations, and variations in between, only some of which can be discussed in the limited space available here. The viewpoints of Krepinevich and Summers are covered first because they in effect frame the scope of the debate and because each makes, respectively, the best-known statement of the guerrilla insurgency and conventional war case.

The case for a counterinsurgency strategy goes back to the early days of US involvement in Vietnam. A variety of civilian and military officials argued that key to winning the war was to defeat the guerrilla insurgency in South Vietnam and that this required a counterinsurgency strategy. They included three prominent and charismatic military figures: Lieutenant Colonel Edward Lansdale, who first served in South Vietnam as a close advisor to Ngo Dinh Diem and then, between 1965 and 1968, as a civilian pacification specialist; Lieutenant Colonel John Paul Vann, who served for about eight years in Vietnam, first as an US Army officer and then as a civilian advisor, before being killed in a helicopter crash in 1972; and Colonel David Hackworth, whose public criticism of the US Army’s approach to the war led to his retirement in 1971. The Marine Corps entered the fray in 1965 by implementing its own version of counterinsurgency in a number of areas in South Vietnam, albeit in the face of criticism from Westmoreland and other top Army commanders on the scene. After the war, the Marine case was made forcefully by General Victor H. Krulak, the overall commander of Marine forces in the Pacific from March 1964 to May 1968.Footnote 50

Picking up this line of thinking, Krepinevich argues that the US Army failed in Vietnam because it overemphasized conventional warfare when in fact it faced a guerrilla war in South Vietnam that required a multi-faceted counterinsurgency strategy to ensure victory. He puts the bulk of the blame for this on what he calls the “Army Concept,” which called for waging conventional war and using massive firepower to minimize US casualties. This approach grew out of the US Army’s successes in its previous twentieth-century wars, the threat posed by the Soviet Union during the Cold War, and numerous contingencies the US Army faced during the Vietnam years with limited resources.Footnote 51 The trouble, says Krepinevich, is that the US Army’s conventional tactics were highly destructive and unsuited to defeating the main threat to the government of South Vietnam: a guerrilla insurgency that drew its strength from the discontent of the peasants. Emphasis therefore had to be placed “first and foremost, on the internal [italics added] threat to the stability and legitimacy of the government of South Vietnam.” Defeating this guerrilla insurgency required more than destroying main-force guerrilla units through attrition, as conventional US tactics were intended to do; it also required eliminating smaller units and the guerrilla political infrastructure, and thereby separating the guerrillas from the rural population. By focusing on attrition rather than counterinsurgency, the US Army “missed whatever opportunity it had to deal the insurgent forces a crippling blow at low enough cost to permit a continued U.S. presence in Vietnam in the event of external, overt aggression.” Making matters worse, the massive use of firepower “alienated the most important element in any counterinsurgency strategy – the people.” The result, Krepinevich concludes, was that the US Army not only failed to defeat the most dangerous threat to South Vietnam – the internal one – but in the process undermined public support for the war in the United States.Footnote 52

The argument for counterinsurgency has been made in a variety of ways by a number of revisionists. Three of the most notable commentators are historian Guenter Lewy (America in Vietnam, 1978), Lieutenant Colonel John A. Nagl (Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam, 2002), and General Lewis Sorley (Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam, 2011). Lewy argues that search and destroy “badly underestimated” North Vietnam’s ability to escalate in response to US measures and that this in turn forced Washington to continue its buildup “with no end in sight.” Search and destroy tactics alienated the population in the countryside; in particular, America’s “lavish use of firepower” inhibited the efforts of the South Vietnamese government to win the allegiance of the people. Lewy further criticizes the strategy of attrition for neglecting the “crucial importance” of pacification and ignoring that “the enemy whom it was essential to defeat was in the hamlets and not in the jungles.” Finally, he stresses that the war had to be won in South Vietnam by the South Vietnamese themselves.Footnote 53

Nagl stresses the failure of Westmoreland and other US Army commanders in Vietnam to get beyond the lessons they learned on the battlefields of World War II – using terms such as “institutional culture” and “organizational culture” rather than Krepinevich’s “Army Concept” to sum up doctrine that embodied those lessons – despite the fact that they faced a very different war in Vietnam. Nagl notes that there were younger people, both civilian and military, who understood the need to fight a counterinsurgency in South Vietnam but that they were unable to influence the US Army’s approach to the war. Unfortunately, the US Army continued to use the “hammer” of “firepower and maneuver, battalions and divisions” it had previously used with such success instead of the necessary “political-military-economic screwdriver” suggested by innovative thinkers.Footnote 54

Lewis Sorley, like Krepinevich, served in Vietnam. As the title of his biography of Westmoreland makes clear, Sorely places the primary blame for search and destroy and its shortcomings on Westmoreland. He cites General Bruce Palmer, who served as Westmoreland’s deputy in Vietnam, to make the point that search and destroy was Westmoreland’s strategic concept, not an approach imposed on him by Washington. Sorley maintains that in focusing on search and destroy, and therefore on attrition, Westmoreland neglected “two other crucial aspects of the war, improvement of South Vietnam’s armed forces and pacification.” A crucial and controversial twist in Sorely’s account, which is discussed Chapter 6, is that he credits Westmoreland’s successor, General Creighton Abrams, with remedying Westmoreland’s failures and, in effect, winning the war by 1972.Footnote 55

Colonel Summers, the author of On Strategy, disagrees fundamentally with the case that counterinsurgency was the key to victory in Vietnam. He argues that what the United States faced in South Vietnam, notwithstanding the local Vietcong guerrilla insurgency, was a North Vietnamese invasion of that country that in fact was a conventional war. In other words, contra Krepinevich, Summers sees the real threat to the government of South Vietnam as external, not internal. Although the overall North Vietnamese campaign opened with a guerrilla attack, he argues, the nature of the war changed during 1963 and 1964 when Hanoi began sending regular army troops south. The guerrilla insurgency thus was a “tactical screen masking North Vietnam’s real objectives (the conquest of South Vietnam).”Footnote 56

The problem was that the United States responded as if it were dealing with an insurgency: “Instead of orientating on North Vietnam – the source of the war – we turned our attention to the symptom – the guerrilla war in the south.” As for search and destroy, limited as it was to South Vietnam itself, to Summers it was an “intense” version of counterinsurgency. Rather than searching for Communist forces scattered about South Vietnam, the United States should have committed its forces to “isolating the battlefield”: that is, cutting off the routes by which North Vietnam sent soldiers and supplies into South Vietnam. Such an effort would have included cutting the Ho Chi Minh Trail by deploying US, South Korean, and ARVN troops along the 17th parallel from the coast across South Vietnam and extending across Laos to its border with Thailand along with using air and sea forces to cut sea-based infiltration routes. The United States also could and should have maintained a credible threat of an amphibious assault against North Vietnam, thereby tying down significant North Vietnamese troops in coastal defense. By adopting the “negative aim of counterinsurgency” instead of the “positive aim of isolation of the battle field,” Summers argues, the United States left North Vietnam in control of the war while, in the words of Clausewitz, it found itself “simply waiting on events.” In broader military terms, Summers notes that the United States adopted what military experts call the “strategic defensive” in opposing Communist forces in Vietnam. The problem is that adopting “strategic defensive in pursuit of a negative aim” requires that “time is on your side.” In Vietnam, this was not the case. This “fatal flaw” of allowing North Vietnam to control the war crippled the American effort to defend South Vietnam.Footnote 57

A complicating factor in the revisionist debate over search and destroy is that the relatively clear waters regarding counterinsurgency versus conventional warfare have been muddied by input from expert commentators who find both positions flawed. That assessment generally is based on the argument that the Communist effort in South Vietnam was not simply an invasion or an insurgency but both, that is, both a guerrilla insurgency in the South based on the Vietcong and a conventional invasion from the North by the PAVN. These interlocked campaigns were initiated and controlled by the Communist regime in Hanoi. In addition, Hanoi varied its strategy, depending on the circumstances, between emphasizing guerrilla warfare and conventional warfare.Footnote 58 Also at issue is whether or not Westmoreland responded properly to the challenges he faced.

An excellent example of this line of thinking comes from military historian Dale Andrade. In his article “Westmoreland Was Right: Learning the Wrong Lessons from the Vietnam War” (2008), Andrade takes issue with both Summers and Krepinevich. According to Andrade, what the United States faced in South Vietnam was not simply a conventional war or a guerrilla war: it was a “simultaneous guerrilla and main force war.” Andrade characterizes this “ideal melding of guerrilla and main force capabilities” as a “perfect insurgency” and argues that any strategy that ignored one or the other – Andrade sees Summers neglecting the former and Krepinevich the latter – was “doomed to failure.”Footnote 59

As Andrade sees it, when Westmoreland took command in June 1964, he faced a situation in which, contra Krepinevich, enemy main-force units, not small guerrilla groups, constituted the main threat to the government of South Vietnam. Andrade approvingly quotes Westmoreland himself on the point that the “enemy had committed big units and I ignored them to my peril.” In concert with other revisionist commentators, Andrade argues that this “perfect insurgency” existed entirely because of North Vietnam: “Hanoi controlled the insurgency’s leadership, Hanoi mustered the bulk of the main force units, and Hanoi sent the supplies south to keep the war going.” This is also the view of counterinsurgency expert Andrew Birtle, who notes that the war in Vietnam, far from being a classic guerrilla insurgency, was a “kaleidoscopic conflict” in which the enemy consisted not only of traditional guerrillas but “of large, professional military forces directed and reinforced by an external power” determined to destroy South Vietnam.Footnote 60

To that end, as Andrade documents using North Vietnamese sources, PAVN units began infiltrating into the South as early as 1963. The first battalion crossed the 17th parallel and entered combat in the spring of 1963; it was joined by a second battalion in 1964, and by December 1965, just nine months after the first US combat troops arrived in South Vietnam, North Vietnamese units accounted for 55 of the 160 main-force Communist military units – the Vietcong fielded both guerrilla and main-force units – in South Vietnam and just across the border in Laos and Cambodia. Contra Krepinevich, from the very beginning US forces faced an opponent that was using both guerrilla and main-force units. Furthermore, and again contra Krepinevich, it was the PAVN and Vietcong main-force units that were the major threat to the South Vietnamese regime and, in fact, the threat that caused the Johnson administration to send American combat troops to South Vietnam in the first place. That said – and this time contra Summers, who criticizes Westmorland for scattering troops throughout South Vietnam in support of counterinsurgency – General Westmoreland understood the situation and properly used his troops and resources to meet it. Quoting an official US Army history of the war, Andrade argues that Westmoreland’s approach to the situation he faced when he arrived in Vietnam was “sound within the strategic limitations under which he had to work.”Footnote 61

Andrade’ s reference to “strategic limitations” in effect makes the point that search and destroy, which was a strategy of attrition, could not bring the United States victory in Vietnam. He does not fault Westmoreland for this, at least not entirely, although he does criticize Westmoreland for failing to adjust to changes in Communist tactics – which increasingly emphasized attacks by small units rather than large ones – beginning in 1967. The reason Andrade mutes his criticism of Westmoreland is that the “roots of the attrition strategy lay in Washington,” as it was the White House that placed Communist base areas in North Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos off-limits to attack.Footnote 62 Or, as political scientist Christopher Gacek puts it, search and destroy was the “residual strategy” the US Army was left with once Washington denied it the option of going into Laos and Cambodia to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and thereby stop infiltration from North Vietnam, and also deny Communist forces already in the South their sanctuaries.Footnote 63

The result, Andrade maintains, echoing Summers, was that the “allies were always on the strategic defensive in South Vietnam, awaiting attacks from the North Vietnamese, who could limp across the border to recover whenever they were bloodied.” To support this strategic limits argument, Andrade turns to Westmoreland and Admiral Sharp, who in 1968 in their joint “Report on the War in Vietnam” argued that US policy of forbidding attacks against Communist base areas in North Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia “made it impossible to destroy the enemy’s main forces in a classic or traditional sense.” Driving this point home, Andrade also cites the North Vietnamese army, whose official history affirms that these base areas were of “decisive importance to our army to mature and win victory.” Little wonder then that Andrade himself asserts that in making Communist base areas immune to attack, “the United States gave North Vietnam an unbeatable advantage.”Footnote 64 As if that were not enough, the North Vietnamese had the vital support of “two powerful sponsors,” the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. He concludes: these factors, when supplemented with the ability to attack South Vietnam over and over again with no threat of serious retaliation, gave North Vietnam an “unprecedented advantage.”Footnote 65

Finally, the guerrilla insurgency/conventional war waters are muddied further by differing assessments of how successful the strategy of search and destroy actually was. A case in point is the assessment that search and destroy actually was succeeding during 1966 and 1967. However frustrating search and destroy was to many American observers and the US troops who had to carry it out, many commentators have noted that by the middle of 1966 North Vietnam’s leaders were discouraged and concerned about the situation on the South Vietnamese battlefield and, equally important, seriously divided about how to respond. For example, historian James Wirtz writes in his history of the Tet Offensive that by 1967 both Vietcong and North Vietnamese units in the south “were suffering from a gradual erosion of combat capability” because of falling morale and the loss of their supplies to US search and destroy operations. Former US Army major and intelligence analyst Thomas Cubbage II adds that by 1967 “the United States and the Government of Vietnam forces were winning – winning slowly to be sure, but steadily.” Colonel Gregory Daddis – whose overall viewpoint in Westmoreland’s War (2014) actually places him much closer to the orthodox than to the revisionist camp – has observed, “By mid-1966, Hanoi arguably had lost, though not irretrievably, the military initiative to American and allied forces, forcing the Politburo leaders to reassess their strategy.” Lt. Colonel James H. Willbanks holds views that overlap both camps but can be considered revisionist because in the end he suggests that South Vietnam could have been saved had the United States done things differently. He writes in The Tet Offensive (2006) that search and destroy operations during the first half of 1967 badly disrupted the Communist logistic system and forced the PAVN and Vietcong to move bases and supplies into Cambodia. James S. Robbins, a former special assistant in the Office of the Secretary of Defense and author of This Time We Win: Revisiting the Tet Offensive (2010), adds that by the spring 1967 US ground strength and air mobility were taking their toll on both guerrilla and PAVN units, with the result that “Hanoi knew it had serious problems.”Footnote 66

Bui Tin, the former PAVN colonel, provides a North Vietnamese perspective on search and destroy. He reports that between 1965 and 1967 US forces and ARVN forced “our troops into a defensive mode” and that by 1967 the party leaders in Hanoi believed “something spectacular was needed to regain the initiative and reverse the situation if possible.”Footnote 67

How did that situation come to exist? General Davidson explains in some detail what occurred in Vietnam at War, in this writer’s opinion the best military history of the Vietnam War. Davidson acknowledges that search and destroy operations – the first major one took place in January 1966 – had serious shortcomings and usually did not achieve the desired results. Nonetheless, these operations disrupted Communist operations, drove their main forces away from population centers, and inflicted heavy casualties on both main and guerrilla Communist forces. As early as spring 1966, Davidson writes, search and destroy operations had “seized and held the tactical initiative in South Vietnam.” Operations conducted during 1966 and early 1967 maintained and extended that initiative. Especially important in this regard were two division-sized, and often criticized, operations: Cedar Falls (January 1967) and Junction City (February–May 1967). Together they represented a change in US strategy because their tasks included attacking and destroying Communist base areas inside South Vietnam. (The crucial base areas in Laos and Cambodia, however, were out of bounds to US and South Vietnamese forces.) Davidson acknowledges that by refusing to defend their base areas and retreating, Communist forces prevented Westmoreland from achieving his main objective, which was to engage and destroy enemy main-force units. This saved most of these units – Junction City did destroy three Vietcong regiments – but at the price of driving them away from populated areas and into sanctuaries in remote border areas. It also separated the main-force units from guerrilla units, depriving the latter of vital support. Guerrilla forces near the populated areas also lost key sources of arms and ammunition, and their morale suffered. Meanwhile, intensified Rolling Thunder bombing operations, including attacking sixteen critical targets around Hanoi, raised the price of the war in North Vietnam, which now began to suffer from economic dislocation and hardship that included shortages of food, clothing, and medicine.Footnote 68

This situation convinced North Vietnam’s leaders that the ground war in South Vietnam was turning against them and that a new strategy was required. It precipitated a major debate in Hanoi during the spring and summer of 1967 about how to respond. One side called for a major new military campaign, which would be an all-out assault, to break the stalemate and achieve a “decisive victory”; this faction was led by Le Duan, the party general secretary, who by then had supplanted the aging and ailing Ho Chi Minh as the most powerful Communist Party leader. He was supported by General Nguyen Chi Thanh, the field commander of all Communist forces in South Vietnam (who died while the debate was going on, to be replaced as Le Duan’s most important military ally by General Van Tien Dung). The opposition to this risky idea was led by General Giap, North Vietnam’s most respected military leader and a longtime political opponent of both Le Duan and General Thanh, and by the increasingly fragile Ho. Giap argued such an offensive was premature and would be defeated by American firepower and mobility. The issue essentially was decided in Le Duan’s favor by July. Le Duan then carried out a purge in which hundreds of party officials (although not the iconic Giap, who was charged with putting together the plan for the offensive) were arrested. The ultimate result was the Tet Offensive of early 1968.Footnote 69

Strategic Limits and the Ground War

The matter of how much damage the strategic limits imposed by Washington did to the war effort provides a meeting place for several of the divergent revisionist streams, at least with regard to the problem of infiltration of North Vietnamese troops and supplies into South Vietnam. Prominent military officers who fought in the war, whatever their other differences, often agree on this point. As already noted, Summers stresses the need to “isolate the battlefield” by blocking the Ho Chi Minh Trail with ground troops deployed along the 17th parallel across Laos to the border of Thailand. He points out that the Joint Chiefs of Staff advocated doing precisely that in 1965 and that General Westmoreland had his staff draw up a similar plan in 1967. Westmoreland himself reports in his memoirs that he suggested such a plan as early as 1964; his first “Commander’s Estimate of the Situation,” issued in March 1965, also advocated operations in the Laotian panhandle. Westmoreland also had plans to block the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos drawn up in 1966 and again in 1968, shortly after the Tet Offensive. General Davidson, who criticizes Westmoreland for neglecting pacification, approvingly notes that Westmoreland had several “detailed plans” to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos but was prevented from doing so “for political reasons.” Davidson quotes the ancient Chinese strategist Sun Tsu to illustrate Westmoreland’s “plight”: “To put a rein on an able general while at the same time asking him to suppress a cunning enemy is like tying up the Black Hound of Han and then ordering him to catch elusive hares.”Footnote 70

Marine General Victor Krulak, a critic of search and destroy and staunch advocate of counterinsurgency, also stresses the need to stop the flow of weapons “pouring down” the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Krulak wanted to do this before those weapons reached Laos; his recommendation, as he told the assistant secretary of state for Far Eastern affairs in 1966, was to use air power to “destroy the port areas, mine the ports, destroy the rail lines, destroy power, fuel, and heavy industry” in North Vietnam. Advocates of counterinsurgency often cite a US Army study commissioned by Army Chief of Staff Harold K. Johnson and issued in March 1966 known as PROVN (Program for the Pacification and Long-Term Development of South Vietnam) to support their arguments, and PROVN did recommend an increased counterinsurgency effort with pacification as a priority. At the same time, as Birtle points out, the PROVN study also stressed that the “bulk” of US forces “must be directed against the base areas and lines of communication in South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.” Among PROVN’s “possible escalatory policies” was the “long term ground occupation of a strip across the Laotian Panhandle and the DMZ.”Footnote 71

This consensus extends to some revisionist commentators writing long after the fact. Walton, who calls the Ho Chi Minh Trail the “logistic enabler” for North Vietnam’s war in South Vietnam, argues that cutting it (and the less-important “Sihanouk Trail,” which began at the Cambodian port of Sihanoukville and ran through Cambodia into South Vietnam) should have been “the primary combat mission” of US forces in Vietnam. Robert E. Morris points out that during the “decisive phases of the war, 1965 to 1968,” the United States allowed supplies from the Soviet Union and China to “sail with impunity into Haiphong harbor” and then be shipped to Hanoi over vulnerable railway bridges the US “refused to bomb” before they arrived at the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Mark Moyar argues that cutting that trail was a “promising strategic option that did not carry large risks in 1964 or in succeeding years.”Footnote 72

Moyar turns to Bui Tin to back up his argument, and that former North Vietnamese colonel has provided some of the most convincing evidence that the Ho Chi Minh Trail was a vulnerable lifeline that could have been cut. At least, Bui Tin reports, this was how the North Vietnamese themselves saw it. In From Enemy to Friend, he reports that the “greatest fear” in Hanoi was that the United States would use troops to occupy part of the Ho Chi Minh Trail or a key part of the Laotian panhandle. Bui Tin quotes the general in charge of the route as saying, “The Americans could bomb us as much as they wanted. That hardly bothered us at all.” What made him “scared to death” was that the United States would use troops to occupy “even a small part” of the trail. That general, Dong Sy Nguyen, who later rose to the post of prime minister of a united Vietnam, noted that the North Vietnamese soldiers stationed along the trail were skilled at logistics but not experienced combat troops. “Under attack,” he said, “they would have scattered like bees from a hive.” When Bui Tin traveled the trail in 1975, he heard ordinary soldiers expressing their relief that the American ground troops had not come. Bui Tin’s contacts on the North Vietnamese general staff agreed. They told him that all the United States had to do was send two or three divisions – American and South Vietnamese – to occupy a part of the trail, at which point the North Vietnamese would be “in trouble.” That the North Vietnamese were worried is not surprising since, as Bui Tin estimates, by mid-1967 about 98 percent of all equipment reaching the South did so via the Ho Chi Minh Trail.Footnote 73

Several versions of a more drastic and riskier strategic option have been suggested by a number of revisionists including Bruce Palmer, Summers, Walton, and Moyar, among others: threatening to invade (Palmer) or to invade and occupy (Walton and Moyar) the southernmost part of North Vietnam. While rejecting an invasion as too risky, Palmer suggests that “a clear amphibious threat of the coast of North Vietnam … could have kept the North Vietnamese off balance and forced them to keep strong troop reserves at home.” Summers hedges his bets on the issue. While discussing isolating the battlefield, he approvingly mentions both landing troops in the southernmost part of North Vietnam according to a plan suggested in 1965 by General Cao Van Vien, South Vietnam’s highest-ranking military officer, as well as threatening to do so according to Palmer’s proposal, noting that the latter proposal did not involve invading North Vietnam and therefore the risk of PRC intervention. Walton and Moyar maintain that occupying the region known as the Dong Hoi panhandle just north of the 17th parallel would have tied down a significant part of the North Vietnamese army, making it impossible for Hanoi to continue its aggression against South Vietnam. As for how China would have reacted to a US invasion of southern North Vietnam, Walton and Moyar argue that in the 1960s China feared the United States and that Washington should have realized that Beijing was in no position to send combat troops to North Vietnam in response to such a US action.Footnote 74