INTRODUCTION

“The ‘Second Slavery’: Bonded Labor and the Transformation of the Nineteenth-Century World Economy” was first published in 1988.Footnote 1 It was a period in which scholars were turning their energies in a different direction and the text drew little attention. Post-structuralism and post-modernism changed the focus of historical inquiry and swept the academic landscape. Approaches to long-term and large-scale historical change were characterized as “grand narratives” and effectively dismissed. Scholars reduced the scale of inquiry and focused on questions of the agency of individual actors, identity, and cultural meaning. On the other side of the coin, virtually as a counterpoint to cultural approaches, studies of slave economy, particularly those that focus on the question of the abolition of slavery, became a privileged province of the New Economic History. Here, historians combined quantification of large masses of data with economic theory to yield new insights into the productivity and profitability of slave economies. However, like those of cultural history, their accounts also decontextualized historical processes. The New Economic History reintroduced an old distinction between economic and ideological, political and/or moral forces. Their interpretations are firmly embedded in the framework of national histories and operate within a conception of homogeneous linear historical time. They generally regard Anglo-American slavery as normative and presume that the institution of slavery everywhere was subject to the same processes that played themselves out in Anglo-Saxon world. Twenty years later, perhaps motivated by problems created by globalization, growing social inequality, and economic crisis, a growing number of historians and social scientists turned once again to studying processes of long-term and large-scale historical change. World history, the history of capitalism, and capitalism and slavery, among other problems, have assumed an ever more prominent place on the current intellectual agenda. In this atmosphere, the concept of the second slavery has attracted attention from many scholars who have seen it as a productive way of rethinking old problems and posing new ones. It has generated extensive discussion in Latin America, the Caribbean, Europe, and the United States.Footnote 2

However, despite growing interest in the concept of the second slavery, the term is frequently used without considering its theoretical background. For this reason, this article emphasizes the methodological and theoretical approach that underlies the concept of the second slavery in order to draw out its implications not only as a way of addressing the question of capitalism and slavery, but for studying world-economic change more broadly. I would like to make clear at the outset that the second slavery is not simply about the peculiar local histories of the cotton south, the Cuban sugar belt and the Brazilian coffee belt. Rather, the concept of second slavery is formulated within the framework of the capitalist world-economy and offers an approach to the study of world capitalism. It calls attention to the ways that these particular zones of slave production are integral parts of the historical reformation of the capitalist world-economy during the nineteenth century. The development of each zone at once structures and is structured by the world division of labor. Thus, their emergence and development cannot be understood outside of that of the capitalist world-economy as a whole. By interpreting these particular slave formations as parts of the world-economy, the second slavery concept simultaneously reinterprets the history of Atlantic slavery and of the world-economy. It calls attention to the spatial and temporal specificity of particular slave formations and challenges linear narratives constructed around the antithesis of slavery and progress. At same time, it critically reworks the world-systems perspective to more adequately account for the complexity of global–local relations.

THE CONCEPT OF THE SECOND SLAVERY

The concept of the second slavery represents an attempt to account for the extraordinary expansion of new frontiers of slave commodity production – cotton in the US South, sugar in Cuba, and coffee in Brazil – during the nineteenth century and their role in the economic and political transformations of the nineteenth-century world-economy.Footnote 3 These zones of the second slavery are of special interest because their development runs counter to prevailing interpretations of slavery in the Americas, which regard slavery as incompatible with a modern industrial capitalist economy and liberal political ideas and values. Such assumptions about the archaic or anachronistic character of slavery in the modern world have long been mobilized in the context of national narratives constructed around notions of linear time and progress. Within such accounts, slavery is seen as destined to disappear with the emergence of liberal capitalist modernity, with the result that the persistence or absence of slavery becomes a marker of national backwardness or national progress.

More recently, there has been a shift in scholarly approaches to these problems. Even if many scholars continue to regard slavery as a non-capitalist, social-economic form that is incompatible with free markets and industrial capitalism, the consensus now favors the thesis that modern slavery is a form of capitalism. Despite this shift, the consequences of treating slavery as capitalist remain relatively unexplored even now. Some key conceptual problems are seldom articulated, let alone examined. What is meant by capitalism? In what ways is slavery capitalist? What are the consequences of such understandings? Too often, slavery is simply absorbed into a generalized conception of capitalism as the pursuit of profit through production for the market. The profitability of slavery then serves to simply disqualify any economic motives for its destruction in favor of ideological and political ones – which again play out in a national arena.Footnote 4 Even in its capitalist garb, slavery continues to be treated as a national phenomenon whose anomalous character is measured against an idealized liberal political and economic modernity that is regarded as normative.

Contrary to such assumptions, the work that has been developed from the perspective of the second slavery proposes that the new zones of slave production were formed as parts of a distinct historical cycle of economic and geographic expansion of the capitalist world-economy that transformed the Atlantic world during the first part of the nineteenth century. The condition for these developments were world-economic processes of industrialization and urbanization, the restructuring of world markets, decolonization, and the formation of nation states in the Americas, together with the development of liberal conceptions of politics and economy. On the one hand, these zones met, through the massive redeployment and restructuring of slave labor, growing world demand for cotton as an industrial raw material, and sugar and coffee for consumption by the working and middle classes concentrated in the urban centers of the North Atlantic. On the other hand, they were shaped by the political forces of the Age of Revolution and confronted the forces of anti-slavery and decolonization. US independence, the Haitian Revolution, and Latin American independence destroyed the colonial system in the Atlantic (which had provided the structural support of the preceding slave systems) and led to the formation of independent nation states in the Americas. As part of this political movement, the ideological terrain of the Atlantic world was transformed. Vigorous liberal and anti-slavery movements and ideologies appeared throughout the Atlantic world together with multiple episodes of slave resistance, with new and diverse ideological contents. Britain, which had abolished the slave trade and slavery within its own empire, spearheaded efforts to abolish the international slave trade, the lifeblood of the second slavery and to reshape the Atlantic political and economic order in accordance with liberal principles. However, liberal ideas were not the monopoly of anti-slavery forces. The pro-slavery politics of the second slavery were defined in relation to this politics of abolitionism and anti-slavery; beyond that, they were themselves frequently grounded in liberal conceptions of economy and state.Footnote 5

The territories in which the second slavery most fully developed were new commodity frontiers. Each was a relatively extensive unexploited zone at the margin of settlement with favorable environmental and geographical conditions for the cultivation of a particular crop. With the material and economic expansion of the world-economy during the first half of the nineteenth century, each zone was quickly subordinated to the production of its particular crop and incorporated into the changing world division of labor. Because these zones were relatively unpopulated and plantation production expanded rapidly there was a chronic shortage of labor that was met by the slave trade.Footnote 6 Slavery in these new agricultural frontiers was reconfigured within an unprecedented constellation of political and economic forces. Its systemic character and meaning were profoundly altered compared with previous forms of slavery. At the core of this expansive second slavery was the redeployment of slave labor as a mass productive force, that is the mass concentration of slave laborers devoted to monocultural staple production and the creation of new productive spaces to meet growing world market demand. Staple production in the new zones of the second slavery had to adapt to competitive and expanding post-colonial markets. Each zone was characterized by the increased geographical and economic scale of production, the expansion, and intensification of slave labor, and the incorporation of new production and transportation technologies. Each led the world in the production of its particular commodity and expanded production at an unprecedented rate over the first half of the nineteenth century. The emergence of the new zones of the second slavery restructured the overall pattern of Atlantic trade. While the US South became the leading exporter of raw cotton to Britain, the US became the prime market for Cuban sugar and Brazilian coffee. These zones generated a demand for labor that, between 1814 and the mid-1850s, when the international slave trade finally came to an end, brought the Atlantic slave trade, both legal and illegal, to perhaps the highest level in its history. In addition, the US and Brazil had substantial internal slave trades. The destinations for these involuntary laborers were almost exclusively the new commodity frontiers. The zones of the second slavery were part and parcel of the formation of the liberal industrial capitalist order of the first half of the nineteenth century. They exposed the inner antagonisms and contradictions of this order.

THE SECOND SLAVERY AND THE WORLD-SYSTEM

The concept of the second slavery attempts to come to terms with the spatial and temporal specificity of these new frontiers of slave commodity production. It challenges conventional paradigms for interpreting the slave formations of the Americas by viewing them not as anachronisms or survivals, but as integral aspects of the formation of the nineteenth century world political and economic order. It is, I think, what Pierre Bourdieu calls an “open concept”.Footnote 7 It allows us to bring together and reinterpret, within a new explanatory framework, disparate phenomena that are already known but are ignored, taken for granted, or treated as anomalies or anachronisms. At the same time, it allows us to ask new questions for research. Many of the substantive changes entailed in the development of the second slavery have been examined by scholars. However, they have been treated as purely national phenomena and inscribed in a continuous linear history of slavery that reproduces the archaic/modern binomial. The concept of second slavery offers a new way of looking at these processes and interpreting them. Instead of proceeding by means of national narratives or conventional formal comparison of distinct slave societies, it seeks to trace the sequences of world historical change that transformed slave relations in each of these new zones during this period and draw out their implications for our understanding of slavery and the development of the capitalist world-economy.Footnote 8

The concept of the second slavery is constructed within theoretical assumptions and methodological procedures that derive from the world-systems perspective. At the same time, it reworks that perspective in order to more adequately account for the specificity of particular social formations and the complexity of the historical processes forming and reforming the capitalist world-system. It does not emphasize only the distinctive character of slavery in nineteenth-century Brazil, Cuba, and the US South. It also calls attention to the changing character of slavery within the expansion and reformation of the world-economy and the coexistence and interdependence of slavery, wage labor (and by implication other forms of commodity producing labor, including combinations of coerced labor and wage labor and/or subsistence labor), and industrial production within a unified world division of labor. In this way, it seeks to contribute to our understanding of the changing character of the world-system itself. As opposed to linear narratives of slavery and the binomial opposition of slavery and freedom, whether posited globally (“universally”) or repeated in each national context, this approach formulates the problem of slave production in terms of global–local relations. It seeks to understand how particular slave formations are the specific local or regional products of world-systemic processes and how such formations contribute to the structuring and restructuring of the capitalist world-system.

This approach provides a means by which we may comprehend the variety and complexity of historically formed global–local relations. Local research is constructed in a way that reveals the global. Particular local historical-geographical complexes of slavery are conceived as parts of a larger, historically changing whole. They are formed within and as parts of broader fields of relations and meaning. The theoretical reconstruction of historical particulars with this framework discloses time-space differences between apparently similar phenomena – slavery, plantation, colonialism, frontiers, etc. Role, function, and meaning are specific within the historical formation and reformation of the broader whole. Each individual historical-geographical complex – i.e. the US cotton frontier, the Cuban sugar frontier, and the Brazilian coffee frontier – is a specific point of concentration of relations and processes operating on diverse spatial and temporal levels. At the same time, the global whole is made and remade through the historical particulars that comprise it. The concepts employed in this perspective are relational and entail a logic of “double specification”: by historically specifying these slave formations within the processes reforming the world-system during the nineteenth century, this approach simultaneously contributes to specifying and concretizing our knowledge of the world-system as a whole. The global discloses the local as the local discloses the global.

From this perspective, each particular local history is regarded as the product of the confluence of relations and processes operating across multiple spatial-temporal planes ranging from place-specific environmental conditions to the world market and interstate system. It forms a distinct historical-geographical complex that is understood not as an empirically discrete, independent, and internally integrated unit with its own history, but rather as what I have elsewhere characterized as “the local face of world process”.Footnote 9 Here “global” and “local” are treated not as ontologically separate entities or independent “levels” of analysis, but as opposite poles of a unified but spatially and temporally complex set of relations. Considered as analytical units, such particular formations are not taken as given and integrated entities, each with its own economy, polity, and society, and thus its own history that is “internal” to its boundaries. Instead, they are treated as outcomes that are continually made and remade through the variety of historical relations and processes of which they form a part. Each particular element or formation is formed through its relations with all other elements as parts of a unified and structured world-system from which they derive their meaning and function. From this perspective, particular social formations are conceived as specific configurations of conditions, relations, and processes of diverse spatial and temporal extension, which are not necessarily coterminous with the boundaries of the local unit, but rather converge to determine its individual character. Each forms a distinct historical-geographical complex that has its own history and is the product of that individual but situated history.Footnote 10 At the same time, it is constitutive of the historical formation of the world-economic whole. In general terms, we may construe these processes as the histories that precede incorporation into the capitalist world-system, the specific historical conditions of incorporation into the system, and the histories of their production and reproduction within, and contribution to, the system. With incorporation into world-economic relations, each particular local history is reoriented and restructured. It is formed within the history of the unified world-economy of which it is a part.

This conception of particular formations as parts of the world-systemic whole compels us to reconsider the concept of the capitalist world-system and its methodological implications. The world-systems perspective provides a powerful analytical tool. However, its methodological implications have been relatively neglected, and it is often taken, even by its proponents, as a theory to be applied to historical reality rather than as a framework for organizing inquiry.Footnote 11 In its effort to grasp the historical development of capitalism as a whole, the world-systems perspective dramatically reorients the framework of analysis, in contrast to those of conventional Marxism and comparative sociology or history. Instead of presuming a multiplicity of independent national or local units of analysis, this perspective is grounded on the assumption of a comprehensive and singular historical system.

However, the conception of the world-economic whole that is posited here needs to be critically examined if we are fully to grasp the methodological and theoretical implications of such an assumption. On the one hand, the whole is not identified with the totality of facts, that is, the sum of all possible knowledge of the historical world. The sum of all facts is, of course, unknowable; more to the point, such a conception removes from consideration the substantive historical relations that structure the totality. From such a methodological perspective, the various parts comprising the world-economic whole can be added, subtracted, or rearranged at will. On the other hand, neither is the world-economic whole regarded as an already-given superordinate structure, a distinct reality that exists over and above its parts. This latter conception is exemplified by Charles Tilly’s proposal for “encompassing comparison”. Tilly’s approach seeks to provide more adequate causal accounts of variation between cases locating them within an overarching structure or process. Explanations of similarities or differences between cases are consequences of their relationships to this governing whole. In this way, Tilly seeks to historically ground comparison and causal explanation in the specific temporal and spatial context provided by the governing unit.Footnote 12 Comparison is conditioned by the location of the units being compared in an encompassing structure, which is external to them. In this formulation, the whole is treated as an abstract and independent entity that takes precedence over the parts, while the subordinate parts are conceptually independent of one another and of the whole. The challenge here is to keep from treating the whole and its parts as if they refer to discrete empirical entities that are opposed to one another as independent things. Such an already-given governing whole would remain an abstraction that is unable to account for the richness and complexity of the parts and their relations with one another. The formation and interrelation of the units would again be removed from consideration.Footnote 13

In contrast to these conceptions of the whole, the capitalist world-system is regarded here as an historically evolving, self-forming totality of unified relations and process. However, it is not taken as an empirical whole, but rather as a methodological construct that guides the theoretical appropriation and reconstruction of historical reality. Its specific structure is conceived as formed through the historically changing relation and interaction among its parts. At the same time, the whole unifies and orders the relations among those parts and thus gives them coherence as a system. This world-economic whole provides the abstract and provisional point of departure and guide for selecting, ordering, analyzing, and interpreting relevant facts. Our concern is not to account for all possible facts, but for those facts that are structurally parts of the whole. By differentiating, specifying, analyzing, and integrating particular relations and processes within this totality, this procedure allows us to reconstruct the capitalist world-economy as a concrete historical totality, that is to say, to move cognitively from the whole to the parts and from the parts to the whole.Footnote 14 Such an approach avoids what Derek Sayer calls “violent abstractions”.Footnote 15 Local or national units are not taken as independent, externally bounded, internally integrated entities. Rather, global and local are treated as inherently connected and mutually formative; but neither is reduced to the other. The local retains its particular character even as it is reproduced within the totality of world-economic relations. It defines the whole as it defines itself. At the same time, the significance of each local part derives from its position within relations of varying spatial and temporal extension comprising the global whole. Conversely, the global whole cannot be outside of or superior to its local parts because it is formed through its interaction with them. Thus, the world-economy is conceived as a relation that is at once structured and structuring, the changing relation between the whole and its parts.Footnote 16 From this perspective, the task is to comprehend the local through the global and the global through the local.

Thus, the analysis underlying the second slavery is an attempt to critically rework the world-systems approach so that it more adequately incorporates specific local relations and processes. The historical development of each of the three commodity frontiers of the second slavery is simultaneously global and local. Instead of construing the US South, Cuba, and Brazil as separate but commensurate slave plantation societies with comparable constellations of land, slave labor, and technology, this approach regards them as spatially and temporally specific “bundles of relations”.Footnote 17 These “bundles” are treated as provisionally isolated instances that are formed within broader unitary world-systemic processes. In each instance, land, slave labor, and capital were mobilized and technologies appropriate to each crop were deployed in specific environmental-geographical and historical conditions and formed distinct zones of production. These distinct configurations of material, social, and economic relations established new commodity circuits that were firmly anchored in the emergent industrial division of labor. Thus, each such space is a particular historical outcome formed through its relation to other such spaces and to the world-economy as a whole. Such formations may share characteristics with one another to varying degrees but each is necessarily spatially and temporally singular. At the same time, they are formative of the world-economic whole. The structural similarities between these historical-geographical complexes provide the point of departure for a deeper inquiry into their specificity.Footnote 18

THE PROBLEM OF METHOD

The approach presented here is not a theory. Rather, it is a perspective, a method of inquiry into a range of problems. But this method is not arbitrary: rather, it must be appropriate for the problem under consideration. The world-system perspective inverts the logic of conventional social science or comparative history. Here, the logic of inquiry does not attempt to construct the whole by adding up the parts, nor does it look for “lawful variations” among commensurate cases. Instead of presuming a multiplicity of independent and comparable units (societies), it presupposes a single unified world-economy in which each local part is constituted differently from the others and occupies a distinctive temporal-spatial location. The theoretical assumptions of the world-system perspective require distinct methodological procedures. Because global–local relations are conceived as part-whole relations, relations between the units under consideration are regarded as hierarchical and asymmetrical. Whole and part cannot be reduced to one another. The whole is formed through the relation of its parts but is superior to any particular part and regulates the relation among them: the parts are the product of their relation to one another and to the whole, but they cannot be directly assimilated to the whole. Therefore, causal and comparative strategies must account for this asymmetric and relational structure. The units under examination are neither independent of, nor commensurate with one another. Rather, particular phenomena are interrelated and derive their meaning from their position in the whole.

Within this framework, the relations forming and reforming the units are more the focus of attention than the properties of the units themselves. Social historical causality is necessarily tied to the complex interdependence and interaction of diverse relations. The units themselves are not taken as given. Instead, each particular unit is regarded as “a partial outcome of complex causes and a partial cause of complex outcomes”.Footnote 19 Viewed in this way, the attributes or features of particular units are markers or points of reference for comprehending systemic processes. By analyzing them within this perspective it is possible to establish how they are formed within broader fields of relations and processes, and how they disclose world-systemic processes. Consequently, the task of analysis is to differentiate and specify particular relations and processes within the unifying world-economic whole and to reconstruct their relation to one another and to the whole. In this way, it is possible to also specify the abstract whole and arrive at a more concrete understanding of its structure and the historical processes forming it.

This conception of a structured and unified world-systemic whole with subordinate parts allows us to distinguish between the unit of analysis and particular units of observation. The former refers to the concept of world-systemic whole as the analytical framework (the assumptions and presuppositions guiding inquiry). The latter refers to the particular units that are selected as the objects of inquiry. These are theoretically and historically reconstructed by critically selecting, evaluating, and interpreting appropriate factual material; analyzing in detail the forms of their development; and tracing the relations through which they are connected to the world-system. Thus, we may study particular time-space constellations, or geographical-historical complexes, of relations within the world-system, for example Barbados, Jamaica, or Cuba, but they are to be analyzed and interpreted as parts of the larger world historical whole. They are understood as particular configurations of world-systemic processes even as they are constitutive elements of the world-system.

The distinction between the unit of analysis and the units of observation has been the source of a great deal of misunderstanding by both proponents of the world-systems approach and its critics. The alleged inability of the world-systems approach to account for the particularity and complexity of local or national change has been one of the reasons many scholars have been critical of this perspective. However, in my view, such responses result from a failure to recognize the distinctive methodological assumptions and procedures posited by the world-systems perspective. These derive from the singular character of the world-system. It is at once the conceptual framework for organizing knowledge (unit of analysis) and a substantive historical relation (unit of observation). As unit of analysis the concept of the world-system is the methodological presupposition of inquiry. This formulation of the world-economic whole is necessarily abstract and notional. It is the point of departure for investigation of a social historical reality that is not yet known. The relations and processes historically forming it have yet to be specified. Specification can only take place through the theoretical appropriation, analysis, and interpretation of historical particulars. The differentiation and specification of historical particulars discloses the concrete historical structure of the world-economy as a unified, but hierarchically structured spatial-temporal whole by establishing the specific historical relations and processes forming the object under investigation. Thus, world-system as conceptual framework and point of departure is distinct from the world-system as product of analysis and interpretation, as point of arrival and outcome of analysis.Footnote 20

Collapsing the distinction between world-system as the conceptual presupposition of inquiry and the concrete conception of the world-system as the outcome of analysis results in an abstract, static, and suprahistorical conception of the world-systemic whole that is taken to stand outside of isolated and equally abstract facts. Such a conception is unable to theoretically appropriate empirical reality in its historical richness and complexity. It can only treat the whole as greater than its parts. As a result, historical analysis is reduced to merely classifying abstract facts into already given categories. Explanation, then, derives not from the relations among the facts but from the relations among abstract categories. Functional descriptive categories dominate. Events and processes are narrated within unchanging categories, and the system appears as an ever-present “external cause”. We are presented with a historical structure without a history.Footnote 21

In the approach presented here, the purpose of inquiry is to understand processes of change and societal transformation, not to catalogue static characteristics of a given phenomenon. Beginning from the world-system as unit of analysis, investigation proceeds through examination of the unit of observation which forms the object of inquiry. This may be a particular process, relation, social formation, or even the world-system itself, depending upon the problem that is selected. The task of analysis is to specify the relations and process through which the particular unit is formed in order to establish it as a part of the whole. Theoretically reconstructing the particular unit of observation within the world-economic whole establishes the complex interrelation and interaction of the elements through which it is formed. The part being theoretically reconstructed plays a twofold role in this approach: it is at once a product and a producer. On the one hand, investigation seeks to determine the specific relations and processes that form the unit being observed; on the other hand, it also seeks to determine the ways that the part contributes to the formation of the world-systemic whole by historically reconstructing the relations that structure and restructure that whole. Through this procedure, theoretical appropriation and reconstruction of particular historical developments contributes at the same time to comprehension of the world-system as a specific historical structure of relations and meanings. Specification of the part is simultaneously specification of the whole. The process of cognition returns to its starting point, to the world-system as a whole, but now as the outcome of research and analysis, an empirically rich reconstruction of the world-system as a concrete, structured totality of historically specific relations.Footnote 22 This approach implies that the relation of capitalism and slavery cannot be resolved through definitions, but rather needs to be approached through theoretically informed empirical investigation of continually changing combinations of diverse social relations. At the same time, it provides a perspective that allows us to understand broader sets of changes throughout the capitalist world-economy.

The approach presented here has much in common with what Philip McMichael has termed “incorporating comparison”.Footnote 23 McMichael proposes the strategy of incorporating comparison as a means of avoiding the limitations of abstract and formal comparisons that presume fixed units of analysis, generally national societies, conceived independently of historical time. At the same time, he seeks to provide an alternative to Immanuel Wallerstein’s conception of the modern world-system as an already-given, comprehensive social historical whole. McMichael’s approach does not presume an a priori all-encompassing world-system. Rather, it is based on comparisons of historically specific relations and processes conceived as parts of a self-forming whole. Here, comparison progressively constructs the whole by contextualizing the parts. In McMichael’s view, “totality is a conceptual procedure rather than an empirical or conceptual premise”. He contends that such an approach gives specific substance to the historical processes forming the whole and overcomes prioritizing a conception of the capitalist world-economy as an already given whole.Footnote 24 In contrast, I wish to argue that in order to specify such relations and processes, the comparison must be grounded in at least a provisional notion of the capitalist world-economy as a totality. Without such a premise there is no field within which to order the relations and processes identified by the comparison. The conception of the world-economic whole cannot be established simply by comparison of specific instances as McMichael seems to imply. We cannot compare all possible parts. Rather, parts are selected in the light of the problem under consideration. The task of comparison is not to construct the whole, but rather to specify and concretize the relations and processes comprising it. Nonetheless, the reformulation presented here is sufficiently aligned with McMichael’s approach that the term “incorporating comparison” remains a valid designation for both. Its continued use is preferable to the creation of a new term in order to try to differentiate the two approaches.

INCORPORATING COMPARISON: JAMAICA, GUIANA, CUBA

I would like to briefly sketch a comparison between Jamaica, Guiana, and Cuba during the nineteenth century in order to practically demonstrate this approach and to indicate how the analysis of the second slavery was elaborated.Footnote 25 This comparative strategy presented here is not universally valid. Rather, it grounds comparison in world-systemic processes. Here, comparison is not the abstract framework of inquiry, but its substance. Its purpose is to give historical content to global–local relations by specifying the relations and processes forming the system through comparison of the parts.Footnote 26 The apparent structural similarities and differences between these zones is the point of departure for a deeper investigation to establish the specificity of each within world-economic processes. By comparing how local geographical historical complexes and the relations among them are restructured, this approach establishes spatial-temporal differences between apparently similar processes and contributes to a more concrete understanding of the historical forces transforming the structure of the world-economy as a whole.

A provisional notion of the capitalist world-economy during the cycle of material and economic expansion between 1815 and 1860 provides the unit of analysis and grounds the comparison. In contrast to conventional comparative strategies, Jamaica, Guiana, and Cuba are treated not as independent and commensurate cases of slave plantation societies, but rather as parts of this larger whole. They represent differentiated historical outcomes of world-systemic processes.Footnote 27 Each historical-geographical complex is a distinct instance of slave sugar production within a unified world-economic division of labor. Each has its own particular history where land, slave labor, and technology combined in different ways with different consequences. Thus, land, labor, and technology appear not as autonomous and equivalent “factors” or “variables”, but as historically formed social relations that are constituted differently in each instance. As parts of the world-economic whole, they form units of observation of world-economic processes.

By emphasizing the unity of world-economic processes, this approach opens the way for comprehending the relational character of the instances under comparison. Instead of external contextualization, incorporated comparison seeks to relate apparently separate moments in order to grasp them as interconnected components of a broader, world-historical process or conjuncture. Such interrelated instances are “both integral to, and define, the general historical process”.Footnote 28 The aim of comparison here is to analyze the way that each instance under examination is historically constituted within and constitutive of the relations forming the world-economy, and the ways in which the differences between them are consequential for historical development. By comparing the relations between such instances, we will be able to specify the processes and relations through which the various historical-geographic complexes are formed, but also to determine, at the same time, the structure and organization of the world-system as a historically formed whole.

A comparison the slave-sugar complexes of Jamaica, Guiana, and Cuba within the cycle of expansion of the world-economy between 1815 and 1860 calls attention to distinct local histories as parts of the complex structure of world-economy and reinterprets the history of slavery. For the purposes of this comparison, the salient features of this world-economic cycle include industrialization, urbanization, and population growth, the American and Haitian Revolutions, Latin American independence, the rise of anti-slavery in its various forms, British abolition of the slave trade, and British economic and political hegemony over the world-system. The expansion and restructuring of the world sugar market was a central aspect of this world-economic cycle, and Jamaica, Guiana, and Cuba were major centers of production. The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 initiated the dramatic expansion of world sugar production and the reorganization of world markets. This cycle of expansion accentuated the difference between old sugar colonies and new commodity frontiers. Jamaica, Guiana, and Cuba each had a distinct historical trajectory that determined how it was reformed as part of the emergent world division of labor during this cycle of expansion.

Jamaica was an old plantation colony. By the mid-eighteenth century, it was already Britain’s leading sugar producer. The prime lands for sugar cultivation, located on the coastal lowlands and inland valleys, were already occupied by the 1790s. The Haitian Revolution initiated a wave of expansion onto less favorable lands. Production nearly doubled between 1792 and 1799 and reached its peak in 1804. Geographical and physical conditions combined with the demand for sugar and availability of capital and slave labor to determine the scale of production. The size, number, and location of plantations and the size and composition of their slave labor forces were organized according to the material and technical conditions that prevailed during the eighteenth century. Jamaica’s response to the new cycle of expansion after 1815 was contraction and consolidation. The sugar industry had reached its environmental and socioeconomic limits. Plantations in marginal areas were abandoned and production contracted to the original zone of prime lands. Estates in the old zone were marginally expanded onto unoccupied or uncultivated lands or they were consolidated. Slaves were shifted to sugar production from other activities, and planters adopted new grinding and milling technologies. However, the scale of plantation organization had been determined in the eighteenth century, so that increases in output and efficiency were marginal. In the absence of extensive new territory for expansion, technological innovation did not have a transformative effect. Rather it reinforced the existing agrarian structure. Because of the topography of the island and the already existing built environment it was difficult to achieve the optimal combination of land, labor, and technology. Although Jamaica remained the world’s leading producer until the mid-1820s, production remained relatively stable and even declined slightly until slave emancipation in 1834.

Britain acquired Guiana at the end of the Napoleonic Wars. This territory was a new frontier of sugar production. Its 1,750-square-mile coastal plain contained large tracts of virgin land and offered excellent conditions for sugar production. However, most of this land was at or below sea level and cultivation required the construction of a massive system of dikes and canals. Because much of this land was unoccupied, it was possible to construct larger plantations that were adequate to the requirements of the new industrial sugar manufacturing technologies that became available during the first half of the nineteenth century. However, Guiana was incorporated into the Empire after Britain abolished its slave trade. Even though it became the most important British sugar colony, it was faced with a chronic shortage of labor. With the abolition of slavery, Asian indentured laborers were imported to meet the growing demand for labor. Guianese plantations were larger, more capital intensive, and more technologically advanced than elsewhere in the British West Indies. The size of capital investment required for their operation encouraged technological innovation and the consolidation of very large estates in order to take maximum advantage of the new machinery and the favorable conditions for agriculture. Guianese planters were able to increase output and productivity through amalgamation of properties, economies of scale, technological innovation, and control over the labor force and wage rates. But sugar production could not expand beyond the geographical and environmental constraints of the coastal sugar zone. Guianese production and, with it, the demand for labor, remained relatively stable.

Like Guiana, the Spanish colony of Cuba was a new sugar frontier. It contained 30,000 square miles of virgin prairie that offered ideal conditions for sugar cultivation. The Cuban sugar industry grew slowly after the 1760s, but the decisive turning point was the slave revolution in Haiti. The destruction of the world’s leading sugar producer created the opportunity for Cuba to become a major sugar producer if it could free itself from the restrictions placed upon it by Spanish colonialism. Havana planters elaborated a strategy of free trade in slaves, free trade in sugar, and the application of science and technology to sugar production that guided the development of the sugar industry during the first part of the nineteenth century. Cuban agriculture in general, and sugar in particular, were retarded because the Royal Navy had control of the forest and forbid the cutting of trees. In 1815, the Spanish navy lost control over the forest and the island’s vast interior was opened up to sugar production. Sugar cultivation spread across Cuba’s extensive interior at the expense of the forest. However, the size of the Cuban sugar zone was actually an obstacle to its development. Only with the construction of a railroad network beginning in 1837 was the interior opened to the sugar industry. The railroad allowed the dramatic technological transformation of the Cuban sugar industry. The first half of the nineteenth century saw a sequence of technological innovations in grinding and refining that greatly increased to quantity and quality of sugar produced. Each innovation required greater acreage and more slaves to realize optimal efficiency and profitability. With each innovation, the railroad allowed the sugar producers to expand onto new lands and construct larger plantations. Further, the demand for labor generated by the sugar plantations drove the slave trade to Cuba to unprecedented levels despite British pressure to abolish the international slave trade. By the end of the 1820s, Cuba became the world’s leading sugar producer and doubled its production every ten years into the 1870s. By 1860, it had over 900 semi-mechanized and fully mechanized sugar mills and accounted for a quarter of world supply.

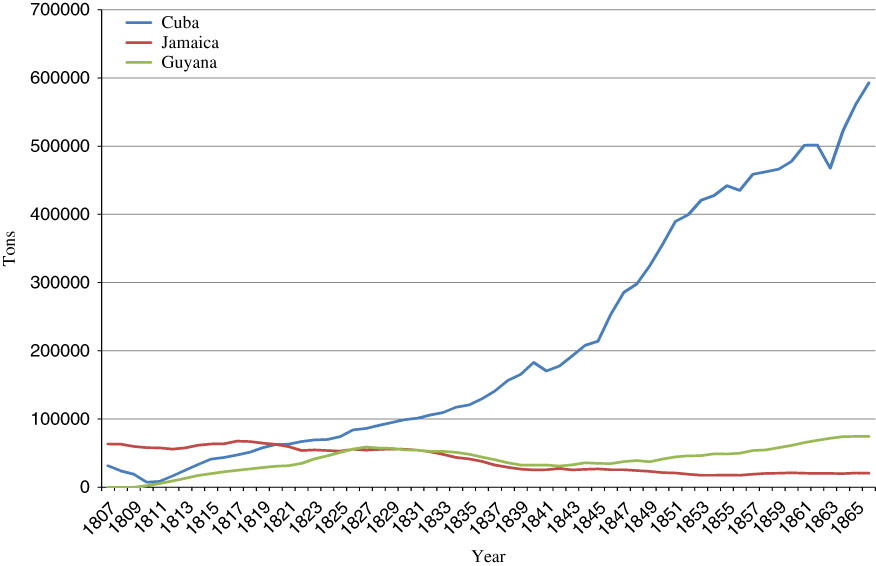

Figure 1 Comparative Sugar Production in Jamaica, Guyana, and Cuba, 1807–1866 (5 Year Weighted Average). Source: Noel Deerr, The History of Sugar. 2 vols (London, 1949), vol. I, pp. 126, 131, 193–204.

Treating Jamaica, Guiana, and Cuba as distinct historical-geographical complexes that are constituted within the nineteenth-century world-economy, rather than as uniform and comparable “cases” of plantations slavery, enables us to account for the diversity and complexity of processes forming each sugar producing zone. Contrary to interpretations that regard slavery as backward, pre-modern, and pre-capitalist, the perspective outlined here calls attention to the specific ways planters in each location expanded and restructured production in accordance with new market conditions prevailing after 1815. At the same time, it reveals the particular geographical, material, and social-economic constraints that each faced. The contrasting outcomes are not simply the result of properties internal to Jamaica, Guiana, and Cuba. Rather, they derive from the interrelation of the three zones and their reciprocal interaction within the expanding nineteenth-century world-economy. They may be seen to represent divergent local outcomes of the expansion and restructuring of the world-economy, and more particularly the world sugar market, during the nineteenth century. The efforts of Jamaican planters to increase the productivity and efficiency of their estates progressively reinforced the pre-existing spatial and social organization of production. Despite their efforts to adopt new technologies and reorganize slave labor Jamaican planters were increasingly marginalized. In contrast, both Guianese and Cuban planters had to invest in the efficient and profitable use of the resources available to them in order to overcome Jamaica’s initial productive advantage. With more cultivable land at their disposal, and access to a labor supply that could be productively employed on their more extensive territories, whether through slavery or indenture, they established larger and more efficient plantations, incorporated the most advanced technologies, and produced more and better sugar with which Jamaica could not compete. Both Jamaica and Guiana enjoyed a favored position in the British market, even though British demand outstripped West Indian production by the 1830s, at least until the repeal of the Corn Laws and the beginning of a policy of free trade in 1846. Cuba, on the other hand, had to place its sugar in competitive markets and was under constant pressure to increase efficiency and productivity. While Guiana was constrained by definite spatial, technological and socio-economic limits, Cuba’s superior endowment of land, and access to slave labor enabled planters to continually restructure production around new technologies. The dramatic increase of Cuban sugar production enabled it to dominate world production and restructure the world market.

Slave labor, land, and technology in Jamaica, Guiana, and Cuba derive their role and meaning from their position within specific historically interrelated and changing configurations within the relations and processes forming the world-economy. Comparison of these three related instances reveals the radical reconfiguration of slave sugar production in distinct historical geographical conditions. The changes in each productive zone were at once structured and structuring. These complexes were not equally susceptible to economic and technological rationalization. The more thoroughly and effectively each region exploited the possibilities given within its particular spatial and temporal configuration, the more the gap between them widened. At the same time, the differentiation and changing interrelation of these three zones transformed the global hierarchy of production and restructured of the world division of labor.

Through the theoretical appropriation and analysis of these three slave sugar complexes we are able to move beyond our initial provisional concept of world-system and contribute to its reconstruction as a specific concrete complex, structured historical whole. By treating each of these instances as a historically specific historical geographical complex of slave sugar production, we can trace the formation of new productive spaces through time. Taken together, Jamaica, Guiana, and Cuba allow us to reconstruct the transnational expansion of sugar production through the creation of new differentiated commodity frontiers as the mode of expansion of the capitalist world-economy. Each historical-geographical complex is an outcome of processes that are dependent upon its temporal and spatial relations within the historical processes forming the capitalist world-system, which are, in part, disclosed by the trajectory of each complex. Each zone established production on a distinct historical scale and possessed a distinct temporal rhythm. The cycle of world-economic expansion, driven by industrial capital, unified and ordered these particular local cycles. It created the conditions for the local complexes, shaped the articulation of their temporal sequences, trajectories, and rhythms, and hierarchized the relation between them. Jamaica represents not merely the persistence of an old pattern of plantation production, but its reproduction, and reinforcement under new conditions of capital accumulation. The very attempts to modernize and rationalize production in Jamaica reinforced the existing structures of production and progressively marginalized the Jamaican sugar economy. Jamaica’s “backwardness” was as much a product of the world-economic cycle as the spatial and industrial reconfiguration of the Guianese and Cuban slave sugar complexes.

This approach contrasts to that of economic historians, who analyze individual societies in isolation and are concerned only with profitability and productivity. These scholars argue that the British West Indies “were capable of vigorous growth and expansion” after 1814 and disqualify any economic cause for slave emancipation in the British West Indies. On similar grounds, they emphasize, “the continuing vitality of the British West Indies well into the nineteenth century”.Footnote 29 In this approach, the declining position of both Jamaica and Guiana, Britain’s leading producers, despite, technological innovation, increasing efficiency and productivity, is eliminated from consideration. For the second slavery approach, on the other hand, the question of slave labor is not taken in isolation as a factor of production. It focuses, rather, on the interrelation of environment, labor, and technology in a specific political economic conjuncture. Guiana and Cuba were not merely repetitions of Jamaica, but new sugar frontiers that dramatically restructured slavery and plantation agriculture, shaped the emergent economic and political conditions of the world-economic cycle of accumulation. Sugar production was constituted on a new scale in Guiana. Larger plantations incorporated new industrial technologies and indenture provided a substitute for slave labor. However, environmental-geographical limits and the chronic shortage of labor restricted the development of the Guianese sugar industry and made it into a second-rank producer. In contrast, the extent of the Cuban sugar frontier enabled producers to mobilize land and slave labor and to incorporate industrial techniques in ways not possible elsewhere. Slavery and sugar production in Cuba were radically reconstituted. More land was brought under cultivation and larger, and more technologically advanced sugar plantations were established on a scale unknown elsewhere. Cuban sugar production accelerated at an ever-increasing rate and reached levels never before attained.

CONCLUSION

By grounding our analysis in the spatial-temporal relations of the capitalist world-economy it is possible to comprehend the radical rupture and historical discontinuity that defines the second slavery. The expansion of the transnational sugar frontier was not merely the quantitative increase of the area under cultivation. Rather, the new cycle of material and economic expansion, premised upon industrial capital and competitive markets, was characterized by spatial restructuring and temporal acceleration. Both Guiana and Cuba were formative of the new configuration of the world division of labor. Guiana was restricted by its limited geographical area and its chronic labor shortage. Cuba, on the other hand, expanded production on an unprecedented scale. There, the radical reconstitution of slave labor and sugar production through increases in scale, new technologies, and new strategies to increase slave productivity kept pace with the volume and pace of expanding world demand and contributed to the restructuring of the world division of labor driven by industrial capital. The cycle of Cuban sugar production thus marks the spatial-temporal rupture that defines the second slavery.

The concept of the second slavery provides a vantage point from which to reappraise the history of slavery in the Americas and, indeed, the history of capitalism as a world-economy. This approach enables us to specify apparently similar phenomena in terms of spatial-temporal difference by establishing the specificity and variety of particular complexes coexisting within the total structure of the larger, unified world-systemic network of political power, social domination, and economic activity. The distinctive limits and/or possibilities of sugar production in Jamaica, Guiana, and Cuba were only clarified through the processes reordering world capitalism in the economic-political conjuncture during the first part of the nineteenth century. Cuba and the other zones of the second slavery anchored the new world division of labor and enabled the domination of industrial capital. Further, by reshaping world commodity markets, they were fundamental factors in the crisis of the older zones of colonial slavery and the abolition of slavery in them. At the same time, the regimes of the second slavery call attention to the centrality and continuity of diverse forms of coerced labor and the importance of spatial-temporal difference in the remaking of capitalist world-economy during the nineteenth century. They thereby provide a vantage point from which to analyze and interpret the continuity of coerced labor and the diversity of its forms after the destruction of Atlantic slavery – including transnational labor migration and contract labor, tenancy and sharecropping, compulsory labor services, rural proletarianization, and peasantization – in the economic and material expansion and transformation of the world-economy. Thus, by emphasizing the coexistence, interrelation, and interdependence of diverse forms of social production, the perspective of the second slavery offers a fruitful approach not only to Atlantic slavery, but also to subsequent regimes of unfree labor and racial-ethnic stratification in the expanding world-economy.